Abstract

Policy Points.

A consensus regarding the need to orient health systems to address inequities is emerging, with much of this discussion targeting population health interventions and indicators. We know less about applying these approaches to primary health care.

This study empirically demonstrates that providing more equity‐oriented health care (EOHC) in primary health care, including trauma‐ and violence‐informed, culturally safe, and contextually tailored care, predicts improved health outcomes across time for people living in marginalizing conditions. This is achieved by enhancing patients’ comfort and confidence in their care and their own confidence in preventing and managing health problems.

This promising new evidence suggests that equity‐oriented interventions at the point of care can begin to shift inequities in health outcomes for those with the greatest need.

Context

Significant attention has been directed toward addressing health inequities at the population health and systems levels, yet little progress has been made in identifying approaches to reduce health inequities through clinical care, particularly in a primary health care context. Although the provision of equity‐oriented health care (EOHC) is widely assumed to lead to improvements in patients’ health outcomes, little empirical evidence supports this claim. To remedy this, we tested whether more EOHC predicts more positive patient health outcomes and identified selected mediators of this relationship.

Methods

Our analysis uses longitudinal data from 395 patients recruited from 4 primary health care clinics serving people living in marginalizing conditions. The participants completed 4 structured interviews composed of self‐report measures and survey questions over a 2‐year period. Using path analysis techniques, we tested a hypothesized model of the process through which patients’ perceptions of EOHC led to improvements in self‐reported health outcomes (quality of life, chronic pain disability, and posttraumatic stress [PTSD] and depressive symptoms), including particular covariates of health outcomes (age, gender, financial strain, experiences of discrimination).

Findings

Over a 24‐month period, higher levels of EOHC predicted greater patient comfort and confidence in the health care patients received, leading to increased confidence to prevent and manage their health problems, which, in turn, improved health outcomes (depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, chronic pain, and quality of life). In addition, financial strain and experiences of discrimination had significant negative effects on all health outcomes.

Conclusions

This study is among the first to demonstrate empirically that providing more EOHC predicts better patient health outcomes over time. At a policy level, this research supports investments in equity‐focused organizational and provider‐level processes in primary health care as a means of improving patients’ health, particularly for those living in marginalizing conditions. Whether these results are robust in different patient groups and across a broader range of health care contexts requires further study.

Keywords: health equity, cohort studies, models (theoretical), social determinants of health, primary health care, quality of care, primary care

Health inequities are unjust and avoidable differences in health and well‐being between and within groups of people.1, 2 (p266) These inequities are evident in mortality and morbidity outcomes at individual and population levels,3, 4 including chronic illnesses and disability, with important implications for individual quality of life and health system costs.5, 6 Promoting health equity is both a social justice and a practical issue that requires not only addressing the immediate health needs of individuals, communities, and populations but also tackling current and historical injustices manifested in underlying social structures, systems, and policies—the root causes of inequities.7, 8, 9, 10

Health inequities are increasing worldwide,10, 11, 12, 13 including in Canada, despite a strong social safety net and a publicly funded health system that provides access to some core medical and nursing care.14, 15 While some attention has been given to addressing health inequities at systems levels, particularly within population and/or public health contexts,7, 9, 10 efforts to define and measure the characteristics and assess the implications of equity‐oriented health care (EOHC) for health care providers, organizations, and patients are limited. Importantly, although the provision of EOHC is widely assumed to lead to improvements in patient outcomes, research supporting this claim is lacking.9, 16

In the absence of evidence about the impacts of EOHC on health outcomes, decision makers may be less inclined to take up health equity–promoting interventions, particularly those that may be costly and/or disruptive to implement.17 In this article, we examine the relationship between patients’ perceptions of EOHC and selected patient‐reported health outcomes by testing a theoretical model informed by current theory and evidence. Using longitudinal data from 395 patients drawn from a cohort of 567 patients recruited from 4 primary health care clinics in Canada, our analysis is a first step in identifying the direct and indirect relationships between EOHC and patient health outcomes over time and, specifically, identifying selected mediators of this process.

Primary Health Care and Health Inequities

Primary health care has been identified as a key site for population health interventions that address the social determinants of health with the intention of decreasing inequities.18, 19 There have been recent calls for revitalizing primary health care globally using various strategies such as restructuring systems to emphasize prevention; implementing needs‐based allocation of resources for care that is accessible and publicly funded; encouraging multisectoral collaboration and action to influence the social determinants of health; and routine monitoring of health inequities.7, 20 These recommendations address systems‐level changes that could provide a critical foundation for reducing the impacts of structural conditions and barriers linked to inequities. These recommendations, however, offer only limited guidance or support for primary health care organizations and for health care providers who interact with patients to address inequities at the point of care. As reiterated in the recent Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Report,10 although health care organizations alone do not have the power to affect the multiple determinants of health, they do have a responsibility to address health inequities directly during clinical interactions in order to improve patients’ health and quality of life. Newman and colleagues21 argue that approaches that integrate attention to individual‐level change to reduce health inequities concurrently with those that address the impacts of higher‐order structural conditions show considerable promise in reducing health inequities.

We now have abundant evidence that compared with the general population, people who live in marginalizing conditions are at increased risk of a wide range of acute and chronic health problems.22, 23 We use the term “marginalizing conditions” here to draw attention to the social, political, and economic conditions contributing to health and health care inequities and to resist the tendency to define marginalization as a characteristic of individuals or groups rather than the conditions in which they live. For example, mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and substance use, along with experiences of trauma (including interpersonal, community, and past violence), are more prevalent in populations experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage24 and these differences arise through multiple mechanisms, including chronic stress, environmental risks, and discrimination.25 Chronic pain, for example, is often experienced as concurrent for those with histories of violence and mental health issues.26, 27, 28, 29 In primary health care settings, these health issues often intersect to shape people's overall health and quality of life.30, 31 At the same time, even in high‐income countries, people living with both social inequities and poor health have the least access to care, and are more likely to experience underresourced and fragmented services.32

There is also consistent evidence that people who experience health and social inequities are more likely to report both negative experiences of health care, including stigma and various types of discrimination, and a poor fit between services that are offered and their needs.10 Furthermore, negative health care experiences have been linked to delays in seeking care in varied populations, including people experiencing homelessness or poverty;33 people living with mental illness34 or chronic illness;35 those with histories of violence or trauma;36 and those identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender,37, 38 or Indigenous.39, 40 There is an urgent need to develop and test the impacts of primary health care approaches that explicitly attend to issues of equity and to identify the mechanisms by which such care may improve health and quality of life and potentially reduce health inequities. Understanding the pathways leading from more EOHC to better patient health outcomes may yield important insights about equity‐oriented process indicators that could be used to monitor quality of care.

Conceptualizing Equity‐Oriented Health Care (EOHC)

Building on and extending the notion of patient‐centered care, we define EOHC as “an approach that aims to reduce the effects of structural inequities (such as poverty), including the inequitable distribution of the determinants of health (e.g., income and housing) that sustain health inequities; the impact of multiple and intersecting forms of racism, discrimination, and stigma (e.g., related to mental illness, chronic illnesses, non‐conforming gender and sexual identities, etc.) on people's access to services and their experiences of care; and the frequent mismatches between dominant approaches to care (e.g., an emphasis on scheduled appointments versus same day or drop in appointments to accommodate patients’ needs) and the needs of people who are most affected by health and social inequities.”41 This conceptualization of EOHC is consistent with current understandings of health equity9, 10, 16 and draws explicitly on our team's previous research describing the key dimensions of equity‐oriented primary health care services that are particularly relevant when providing care to populations affected by health and social inequities. These overlapping key dimensions have been described elsewhere.40, 41, 42 We summarize them here with some examples to illustrate how they extend more conventional concepts:

Trauma‐ and Violence‐Informed Care (TVIC) extends beyond trauma‐informed practice to explicitly acknowledge and address the intersection and cumulative effects of interpersonal (eg, child maltreatment, intimate partner violence) and structural (eg, poverty, racism) forms of violence on people's lives and health.43

Culturally Safe Care (CSC) moves beyond culturally sensitive approaches to explicitly address inequitable power relations, racism, discrimination, and ongoing effects of historical and current inequities within health care encounters.40

Contextually Tailored Care (CTC) expands the individually focused concept of patient‐centered care to include offering services tailored to the specific health care organization, the populations served, and the local and wider social contexts.

Fundamentally, EOHC is about creating safe and respectful environments while tailoring health care to fit the needs, priorities, history, and contexts of individual patients and populations served. Both individual health care providers and the organizations in which they work are responsible for delivering EOHC. Health care providers must adopt ways of providing care that are consistent with the key dimensions just described and health care organizations also are responsible for developing structures, systems, and policies to enable this care.42, 44 At the point of care, health care providers can use a variety of strategies to implement these key dimensions (see Table 1) and enact these strategies in many different ways.

Table 1.

Examples of Strategies for Enacting Equity‐Oriented Health Care

| Key Dimension | Examples of Strategies for Enactment in Practice |

|---|---|

| Trauma‐ and Violence‐Informed Care | Develop awareness of the high prevalence of trauma and violence in patient populations and the impacts on physical and mental health. |

| Create care spaces and interactions that are physically, emotionally, and culturally safe. | |

| Create opportunities for patient choice and control such as asking permission before touching and making requests, not commands. | |

| Convey openness to talking about sensitive issues such as mental health problems, substance use, and experiences of violence. | |

| Acknowledge all patient concerns as legitimate, even in the absence of observable clinical findings. | |

| Culturally Safe Care | Build staff awareness of the impact of discrimination, stereotyping, and stigma on patients’ health and access to health care. |

| Develop strategies for actively counteracting such processes such as ensuring that the clinical environment is welcoming, inviting, and comfortable for patients; display welcoming signs in as many local languages as possible. | |

| Recognize that patients who are at the greatest risk of experiencing health and social inequities may be affected the most by power inequities. Therefore, develop ways of ensuring that all patients are treated with courtesy and respect. | |

| Seek and integrate feedback from patients about their experiences of care in continuous quality‐improvement processes. | |

| Contextually Tailored Care | Within policy and funding constraints, prioritize services that specifically address the local population's demographics and needs. |

| Routinely inquire about access to the determinants of health such as food, shelter, clothing, and the impact of financial strain. | |

| Offer practical assistance to reduce barriers to accessing health and social services or other resources. | |

| Offer health‐promoting recommendations and strategies that are appropriate to the social contexts of patients’ lives such as those that are affordable and feasible. |

There is some overlap among EOHC and more mainstream concepts, including recovery‐oriented practice45 and patient‐centered care (PCC), although EOHC and PCC have different theoretical roots and aims. A narrative review and synthesis of the empirical, descriptive, and discursive literature regarding PCC show that despite having no single definition, 3 common themes are (1) patient participation and involvement, (2) the relationship between the patient and the health care professional, and (3) the context in which the care is delivered.46 PCC aims to heighten providers’ attention to the importance of understanding the perceived needs and priorities of individual patients in order to guide clinical decisions.47, 48 However, PCC also can be narrowly conceptualized as moving from generalized care to person‐specific care of an individual with a disease or condition. PCC generally uses a consumer approach to health care aimed at improving patient satisfaction, although the patient's and provider's perceptions of quality care may differ widely, leading to calls to evaluate the effects of interventions targeting patient experience on patient outcomes.49

In contrast, EOHC begins with an explicit focus on mitigating the power imbalances, systemic barriers, and dismissive attitudes that people living in marginalizing conditions often encounter when interacting with the health care sector, and it offers health care providers and leaders concrete strategies to enhance an organization's capacity to provide EOHC.42 Ultimately, EOHC is founded on the assumption that compared with the general population, those who face the greatest inequities need more and different types of support to reduce the impacts of the systematic barriers and inequities they experience. Thus, EOHC advocates tailoring to inequities in the specific populations served so that patient care is centered in the context of the individual's life circumstances, the provider‐patient relationship, the specific organization, and the wider society.

Effects of Equity‐Oriented Health Care on Patient Health

As an emerging concept, there is limited evidence that providing EOHC (or any of its key dimensions) leads to improvements in patient health, although there is some support for positive relationships between concepts that are similar to EOHC and patient outcomes. Specifically, the results of a systematic review of studies examining PCC and health outcomes47 were mixed, with some studies supporting significant relationships between specific elements of PCC and some outcomes (ie, patient satisfaction and self‐management) but other studies finding no relationships. There is little evidence that PCC is related to clinical outcomes.47, 50, 51 A number of researchers have suggested that PCC does not directly affect patient health outcomes but works indirectly through other factors, particularly positive perceptions or satisfaction with care.48, 52 However, the processes linking PCC with health outcomes are poorly understood. Research is needed to identify mediators and moderators of this relationship.47 These gaps also exist with respect to understanding how EOHC shapes health outcomes. Similarly, despite the growing number of calls for and enactment of cultural safety and trauma‐ and violence‐informed care, there is limited evidence of their impacts on health outcomes.40, 53, 54, 55

Equity‐Oriented Health Care and Patients’ Perceptions of Care

Given that EOHC emphasizes creating a safe and respectful environment, with care tailored to be optimally relevant to the context of people's lives, we would expect patients to experience that care as supportive and appropriate to their needs, leading to greater comfort in seeking care and confidence that the care they receive will be helpful to them. In a primary care study, Stewart and colleagues found that patients’ perceptions that their physicians “found common ground” with them was strongly associated with key outcomes such as mental health and recovery from illness.52 There is substantial evidence that trust in the provider, a related concept, is an important predictor of patients’ engagement in health care over time.56, 57 However, no studies have empirically examined whether patients’ experiences of EOHC are characterized by a sense of comfort, trust, or confidence in their providers. As we stated earlier, there is extensive evidence that people at the greatest risk of experiencing health and social inequities often experience dismissal, stigma, and discrimination in health care encounters and that care that actively aims to counteract these processes can have a positive impact. Receiving care from providers who attempt to tailor care to patients’ social circumstances or to counteract the potential harms of interacting with the health care system may help create a sense of mutual respect and trust that can be a foundation for engaging with health care over time. However, these kinds of mechanisms and processes have not been adequately studied.10, 58

As comfort and confidence in the care received increase, patients may gain confidence in their capacity to manage their own health issues and priorities. This is closely linked to self‐efficacy,59 a consistent predictor of engaging in health behavior that is shaped by opportunities for performance, modeling, and encouragement from others and is ameliorated by emotional arousal such as anxiety or discomfort.60, 61, 62 EOHC may help shape patients’ self‐efficacy and, consequently, their actions to improve their health. “Agency,” defined as individuals’ capacity to exercise their power, may be constrained by social structures, yet individual actors may also shape their social contexts through acts of resistance.63, 64, 65 Thus, all people exercise agency, even in the face of significant social inequities. While health care alone cannot erase the harm of inequities on people's health and the quality of their lives, Metzl and Hansen argue that “structural competency”—an awareness of how social, political, and economic structures may affect clinical interactions and an ability to envision and implement structural interventions—should be integrated into health professional education and practice as foundational to reducing health inequities.66 EOHC is an approach that fits within these recommendations, whose effects need to be systematically tested.

Theoretical Model

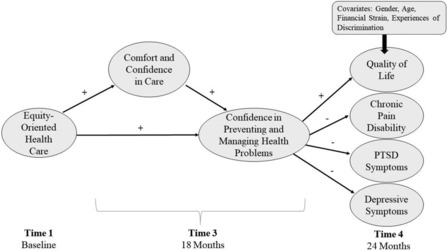

Based on a review of the literature and our theoretical understanding of EOHC, we developed a path model to examine whether experiencing more EOHC improves patients’ self‐reported mental and physical health, as well as the process that explains such effects (Figure 1). The hypothesized relationships among the variables included in the model are represented by arrows. Equity‐oriented health care is proposed to improve patients’ health outcomes (quality of life, chronic pain disability, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] symptoms, and depressive symptoms) by enhancing patients’ perceptions of comfort and confidence in care, leading to greater confidence in preventing and managing health problems. The health outcomes included in this model are among the most common and disabling for people who have experienced trauma, violence, and social inequities.27, 30, 31 Selected variables were also included as covariates of health outcomes: age and gender as demographic characteristics related to health outcomes, and financial strain and experiences of discrimination, particularly powerful structural factors that negatively affect the health of people living with social inequities.3, 15, 22

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Path Model

Given that health outcomes are shaped by a complex set of factors, we did not hypothesize that EOHC would affect health outcomes directly. Rather, we sought to explain the pathways between the level of EOHC and patients’ health in ways that accounted for patients’ experiences of care, how these experiences shaped their capacity for dealing with often substantial health problems, and the role of selected factors outside the clinical encounter in determining health. If they could be identified as mediators, these intermediate steps in the pathway from EOHC to health outcomes could provide important markers for monitoring short‐term gains made within health care settings through the provision of EOHC.

Method

Design

We conducted a longitudinal study to examine perceptions of health care experiences and self‐rated mental and physical health among patients accessing primary health care in 2 Canadian provinces over a 2‐year period. We asked patients to complete structured interviews composed of self‐report measures and survey questions at 4 points in time (baseline, 12, 18, and 24 months later) to measure their perceptions of the care they received in the clinic settings, their comfort with and confidence in providers and services, and specific self‐reported health outcomes. These data from patients were collected as part of a larger multiple‐case study exploring the process and impacts of an organizational health equity intervention (EQUIP Healthcare) on staff as well as the organizational capacity to implement equity‐oriented care.42 The EQUIP intervention included a combination of staff education and a facilitated organizational change project but did not include any direct intervention with patients. The EQUIP intervention and its effects on staff and organizations are described elsewhere.41, 42 Although this article does not evaluate that intervention, it uses the patients’ data to test a theoretical model regarding the relationships between the patients’ perceptions of the extent to which the care they received was equity‐oriented and selected health outcomes.

Sample and Setting

In the larger study, a cohort of 567 patients was recruited from 4 primary health care clinics, each of which had a mandate to serve people living in marginalizing conditions. For the analysis presented here, we used data from a subsample of 395 patients who provided data at the final data‐collection time point. The clinic sites were located in rural, remote, and urban settings in 2 Canadian provinces (British Columbia and Ontario) and served a combined population of 12,000 patients. Consistent with Canada's publicly funded health care delivery model, these clinics provide a range of health services free of cost to patients, both in the clinics and on an outreach basis. At each site, health services are offered by an interdisciplinary team of health care providers that include various combinations of physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, counselors, pharmacists, and, in one clinic, access to Indigenous Elders.42

Patients were eligible to participate in this study if they were adults (18 years of age or older), were able to understand and speak English, had made at least 3 visits to one of the clinics in the previous 12 months, and intended to continue accessing services at the clinic for the 2 years following their recruitment. Our goal was to recruit a sample of patients who had some connection with the clinic, both so that they would have formed an opinion about their health care experiences and as a strategy, given the high mobility of many patients served by these clinics, to minimize attrition over time.

All patients who met the inclusion criteria and came to the clinic to access services on purposively selected days were invited to participate. To enhance representativeness, both those patients who had appointments and those who dropped into the clinic for other reasons were invited to take part. Information about the study was posted in the reception and health care areas in each clinic approximately one month before recruitment began. Administrative staff at each clinic provided information to patients who presented for care and directed those who were interested in learning more about the study to speak to a research assistant (RA) located in the clinic's reception area. The RA provided a verbal description of the study to those who were interested, screened them for eligibility, invited eligible patients to take part, and obtained their informed written consent. Those who were ineligible were thanked for their interest in the study.

Measurement

We used 7 self‐report scales to measure the variables included in the model. In each case, higher scores reflect higher levels of the concepts being measured. Single items were used to capture selected covariates included in the model.

Equity‐oriented health care was measured using the Equity‐Oriented Health Care Scale (E‐HoCS), a 12‐item self‐report index developed from item response theory using data from the full EQUIP patient cohort (M. Ford‐Gilboe, unpublished data, 2018). Initially, we developed items to tap aspects of EOHC amenable to patients’ self‐reports and then refined them using cognitive interviews with a sample of patients. We asked the patients to rate how often in the previous 12 months their health care providers had engaged in each of 12 actions on a 5‐point scale ranging from “never” to “always.” Sample items include “try to make you feel as comfortable as possible”; “seem open to talking about sensitive issues such as grief, mental health problems, substance use, or abuse experiences”; “ask you about basic resources that affect your health, such as food, clothing, or shelter”; “help you work on any barriers you have to accessing health care”; “give you advice that is suitable for your everyday life”; “have a negative attitude toward you because of mental health concerns.” The E‐HoCS total score is a count of the number of items rated by patients as “always” occurring (for 10 positively worded items) and “never” occurring (for 2 negatively worded items), with a range of 0 to 12. Scores on the E‐HoCS reflect the degree or level of equity‐oriented health care, from lower to higher.

Comfort and confidence in care was measured using a 7‐item scale developed for this study made up of items drawn from existing surveys67 and those developed for this study. We asked the participants to rate their experience of care at the clinic in the previous 6 months on a 5‐point scale, and then we averaged their responses to create a mean score (range 1 to 5), in which higher scores indicate more positive perceptions of care. The 7 items tapped into different aspects of comfort and confidence in care: comfort talking with providers about personal problems or concerns (2 items); having enough time with the health care provider (1 item); confidence in the health care provider (2 items); fit of care provided with patient needs (1 item); and overall rating of care received (1 item). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .88.

Confidence in preventing and managing health problems was measured using 2 items developed for this study based on recommendations for the development of self‐efficacy scales.68 We asked the patients to respond to 2 questions (“How certain are you that you can manage your health problems?” “How certain are you that you can take steps to prevent problems with your health?”) on a scale that ranged from 0 (cannot do) to 10 (highly certain can do). The mean score of these responses (range 0 to 10) was used in this analysis. Cronbach's alpha in this sample was .79.

Quality of life was measured using the European Health Interview Survey‐Quality of Life (EUROHIS‐QOL) 8‐item index.69, 70 The scale includes items measuring past 2‐week overall quality of life, general health, energy, daily life activities, esteem, relationships, finances, and home, drawn from the original World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL‐BREF) assessment.71 The EUROHIS has demonstrated reliability and validity across a variety of countries, has acceptable convergence with physical and mental health measures, and discriminates well between healthy individuals and those with chronic conditions.69 Each item uses a 5‐point response scale, with the total summed score for all items divided by 8 to reach a final score ranging from 1 to 5. Sample items are “How satisfied are you with the conditions of your living place?” and “Do you have enough energy for everyday life?” Cronbach's alpha in this sample was .83.

We measured chronic pain disability using 3 items that tapped pain disability in the past 6 months drawn from von Korff's 7‐item chronic pain scale (CPS).72 We asked the patients to rate, on scales ranging from 0 to 10, the extent to which pain interfered with their daily activities (0 = no interference, 10 = completely interfered), changes in ability to take part in activities due to pain (0 = no change, 10 = extreme change), and changes in ability to work due to pain (0 = no change, 10 = extreme change). Using standard scoring, we computed the score for pain disability (range 0 to 100) by multiplying the mean of the 3 disability items by 10. The chronic pain grade (CPG) scale has demonstrated strong reliability and validity among primary care patients72 in the general population73 and among women who have experienced intimate partner violence.74, 75 Cronbach's alpha for the pain disability score in this study was .91.

We measured PTSD symptoms using the PTSD checklist, Civilian Version (PCL‐C).76, 77 The PCL‐C is a 17‐item self‐report measure designed for use in community samples to assess the probability of meeting DSM‐IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The PCL‐C asks patients to rate how bothered they have been by each symptom of stress over the past month using a 5‐point Likert‐type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The total summed scores ranged from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicative of greater symptomatology. The PCL‐C has demonstrated validity and excellent internal consistency reliability in many different populations.78 Cronbach's alpha in this study was .94.

We measured depressive symptoms according to the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Revised (CESD‐R).79 The CESD‐R is a 20‐item self‐report measure of symptoms reflective of the DSM‐IV criteria for depression. We asked the patients to rate how often they had experienced each symptom in the past 2 weeks using 5 options ranging from “not at all or less than 1 day” (0) to “nearly every day for 2 weeks” (4). The total scores were computed by summing the responses to applicable items (range 0 to 60). The CESD‐R correlates highly with the original scale and demonstrates good to excellent face and construct validity, as well as excellent internal consistency (α = .90‐.96).79, 80 Cronbach's alpha in this study was .94.

For model covariates we measured age by a single self‐report item, and we also measured gender by self‐report where “female” was coded as 1 and “male” or “transgender” was coded as 0. To measure experiences of discrimination, we used a question adapted from the Recent Everyday Racial/Ethnic Discrimination Module Field Test.81 Patients were asked, “In the past 6 months, have you ever felt discriminated against in your daily life (outside of this clinic)?” with response options of “never,” “sometimes,” and “often,” which were recoded to a dichotomous variable (never = 0, sometimes or often = 1) for analysis. Finally, we measured financial strain using the Financial Strain Index,82 a 14‐item summated rating scale that has demonstrated reliability and validity across varied populations. Participants were asked to rate the difficulty they had in meeting their financial commitments in 14 areas (eg, housing, transportation, debt repayment) on a 5‐point scale ranging from 0 (very difficult) to 4 (not at all difficult). The total score was computed by reverse scoring and summing responses to all items (range 0 to 56), with higher scores reflecting greater financial strain.

Data Collection, Honoraria, and Ethics Approval

Each participant was invited to complete 4 structured interviews, lasting from 30 to 75 minutes, at baseline and approximately 12, 18, and 24 months later. The investigators and trained research assistants conducted the interviews in a private room at the clinic, using standard protocols developed to promote safe participation, comfort, and retention. For example, interviews were conducted at a pace directed by the patient, and the staff routinely checked in to ensure that the patient was comfortable and offered breaks, snacks, and drinks. Honoraria ($20, $25, $30, and $35 for interviews 1 through 4, respectively) were provided at the beginning of each interview to minimize coercion to “complete” the interview in order to receive the “payment” and to acknowledge the time and effort required to complete the interviews. In view of the high prevalence of violence and trauma experienced by patients in these settings, we held a structured debriefing83, 84 at the end of all interviews to review signs of a stress response and actions that could be taken if the patient felt they needed support or assistance following the interview's completion. The Research Ethics Boards of the University of British Columbia (Protocol # H12‐02994), the University of Western Ontario (Protocol # 103357), and the University of Victoria (Protocol # J2012‐92) gave their ethical approval of the project, and each clinic's leaders oversaw the approval processes at their site.

Data Analysis

We summarized all the variables using descriptive statistics appropriate to the level of measurement. The sample of 395 people used in this analysis includes those from the full sample (n = 567) who provided data at Time 4. Baseline differences in demographic and outcome variables between those included in (n = 395) and excluded from (n = 172) the analysis were tested with chi‐square and t‐tests. No differences were found.

A minimal amount of data were missing, with 9.6% of the sample missing 1 variable and 8.9% missing 2 or more variables. The missing data on age (n = 9) were replaced with the sample mean age. The missing data on the Time 3 variables of experiences of discrimination (n = 31), financial strain (n = 36), comfort and confidence in care (n = 61), and confidence in preventing and managing health problems (n = 34) were replaced with either the mean of the person's scores at Times 2 and 4 or the value at Time 2 or 4 if only one was available.

We used path analysis to test the theoretical model using STATA v.14. Path analysis tests all hypothesized relationships simultaneously. This is preferred to a regression approach, which estimates each path in the model separately and can lead to an inflated error rate. Equity‐oriented health care (EOHC) was measured at baseline and is a proxy for “usual care” in these clinics, as it reflects patients’ perceptions of the health care received in the 6 months before starting this study. Comfort and confidence in care and confidence in preventing and managing health problems were measured at Time 3 (18 months after baseline), and the health outcomes (quality of life, chronic pain disability, PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms) at Time 4 (24 months after baseline). The model allowed the outcomes at Time 4 to be correlated. Gender and age (measured at Time 1) and financial strain and experiences of discrimination (measured at Time 3) were also included as covariates for each health outcome.

Results

Table 2 shows the sample's demographic characteristics, along with selected Canadian national and/or provincial population estimates to enable comparisons. The mean age of patients was 45.8 years (range 18 to 94, SD = 14.6). Nearly 60% were female and about half (n = 197, 49.2%) reported being in a relationship with a partner. Almost 42% identified as Indigenous, a rate about 10 times that of the population. The extent of social inequities evident in this sample was marked compared with population estimates. For example, more than 60% were unemployed (compared with 7.8% in the general population), and 42.5% had not completed secondary school (compared with 12.7% in the general population). Rates of receiving social assistance or disability benefits exceeded population estimates by 8‐ to 24‐fold (29.4% and 38.7% of the sample, respectively).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample (N = 395)

| Sample Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | Population Comparison % | |

| Gender: | 395 | |||

| Male | 160 | 40.5 | 49%85 | |

| Female | 233 | 59.0 | 51%85 | |

| Transgender | 2 | 0.5 | ||

| Aboriginal Identity: | 391 | |||

| Yes | 163 | 41.7 | 4.4%86 | |

| No | 228 | 58.3 | ||

| Employment Status: | 379 | |||

| Employeda | 74 | 19.5 | 60.9%87 | |

| Unemployed | 234 | 61.7 | 7.8%87 | |

| Otherb | 71 | 18.7 | ||

| Highest Educational Level Completed: | 386 | |||

| Less than high school | 164 | 42.5 | 12.7%88 | |

| Completed high school | 60 | 15.8 | 23.2% | |

| College certificate or diploma | 127 | 32.9 | 38.3% | |

| University degree | 35 | 9.1 | 25.9% | |

| Receiving Social Assistance: | 116 | 29.4 | Ontarioc | BCd |

| 3.6%89 | 1.2%89 | |||

| Receiving Disability Assistance: | 153 | 38.7 | Ontario | BC |

| 2.2%89 | 2.0%89 | |||

| Difficulty Living on Total Household Incomee: | 388 | Prevalence of low income in adults 18 to 64: 14.4%92 | ||

| Very difficult | 136 | 35.1 | ||

| Somewhat difficult | 132 | 34.0 | ||

| Not very difficult | 72 | 18.6 | ||

| Not at all difficult | 48 | 12.4 | ||

| Shelter Use (past 12 months)f: | 384 | |||

| Yes | 67 | 17.4 | 0.08%f ,90 | |

| No | 317 | 82.6 | ||

Employed status refers to individuals working full or part time, as well as those doing seasonal work.

The majority of responses in this category are retired, receiving assistance, stay‐at‐home mom, student, and occasional cash work.

Calculation based on Ontario's population in 2011: 12,851,821 (https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=PR&GC=35).

Calculation based on BC's population in 2011: 4,400,057 (https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=PR&GC=59).

Participants were asked, “Overall, how difficult is it for you to live on your total household income right now?”

Calculation of number of persons age 15+ living in a shelter in 2011 (Statistics Canada, 2011 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98‐313‐XCB2011024, Table: Selected Collective Dwelling and Population Characteristics (52) and Type of Collective Dwelling (17) for the Population in Collective Dwellings of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2011 Census.90

Table 3 gives descriptive statistics for all variables included in the model. On average, mean levels of EOHC and confidence in preventing and managing health problems were in the moderate range, while comfort and confidence in care was fairly high (mean = 4.3 on a scale ranging from 1 to 5). The average scores for quality of life, chronic pain disability, depressive symptoms, and PTSD symptoms were all in the midrange, but the use of standard cut scores available for 3 of the 4 measures shows high levels of health problems in this sample. Specifically, 49.3% of the sample were living with levels of disabling chronic pain significant enough to affect their everyday lives (Pain Grade 3 or 4). With regard to mental health, 42.0% of the sample had levels of PTSD symptoms, and 50.3% had depressive symptoms consistent with a clinical diagnosis. In addition, 38.6% reported sometimes or often experiencing discrimination from others outside health care.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables Included in the Model (N = 395)

| Range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Time Point | Possible | Actual | Mean (SD) or % (N) |

| Equity‐Oriented Health Care | 1 | 0‐12 | 0‐12 | 7.54 (3.02) |

| Comfort and Confidence in Care | 3 | 1‐5 | 1.66‐5.00 | 4.28 (0.71) |

| Confidence in Preventing and Managing Health Problems | 3 | 0‐10 | 1‐10 | 7.57 (1.96) |

| Quality of Life | 4 | 1‐5 | 1.13‐5.00 | 3.46 (0.82) |

| Chronic Pain Disability | 4 | 0‐100 | 0‐90 | 31.14 (28.85) |

| PTSD Symptoms | 4 | 17‐85 | 17‐85 | 36.79 (16.57) |

| Depressive Symptoms | 4 | 0‐60 | 0‐60 | 16.47 (14.26) |

| Covariates: | ||||

| Age | 1 | 18+ | 18‐94 | 45.8 (14.6) |

| Gender (female) | 1 | 59.0% (233) | ||

| Financial strain | 3 | 0‐56 | 14‐56 | 32.88 (12.26) |

| Experiences of discrimination | 3 | 38.6% (152) | ||

Table 4 presents the correlation matrix showing the associations among the variables included in the model. As expected, moderate to strong associations were observed among the 4 health outcomes (r = .41 to .83). The degree of association between covariates and health outcomes varied. Age and gender showed no to weak associations with the 4 health outcomes. In contrast, financial strain (r = .320 to −.461) and experiences of discrimination (r = .115 to −.268) were moderately correlated with all 4 outcomes.

Table 4.

Correlations Among Variables Included in the Model (N = 395)

| EOHC | Comfort/ Confidence in Care | Confidence Preventing/Managing Health Problems | Quality of Life | Chronic Pain Disability | PTSD Symptoms | Depressive Symptoms | Age | Gender | Financial Strain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOHC | 1 | |||||||||

| Comfort/ Confidence in Care | .524** | 1 | ||||||||

| Confidence Preventing/ Managing Health Problems | .198** | .409** | 1 | |||||||

| Quality of Life | .063 | .250** | .437** | 1 | ||||||

| Chronic Pain Disability | .010 | −.062 | −.261** | −.502** | 1 | |||||

| PTSD Symptoms | −.074 | −.231** | −.418** | −.634** | .433** | 1 | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | −.098 | −.259** | −.401** | −.671** | .405** | .830** | 1 | |||

| Age | −.005 | .075 | .114* | .100* | .054 | −.130** | −.120* | 1 | ||

| Gender | .048 | −.011 | −.045 | .040 | −.040 | .004 | .061 | −.195** | 1 | |

| Financial Strain | −.045 | −.205** | −.304** | −.461** | .320** | .439** | .374** | −.114* | .126* | 1 |

| Discrimination Experiences | −.104* | −.180** | −.215** | −.268** | .115* | .266** | .250** | .084 | .048 | .281** |

* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01

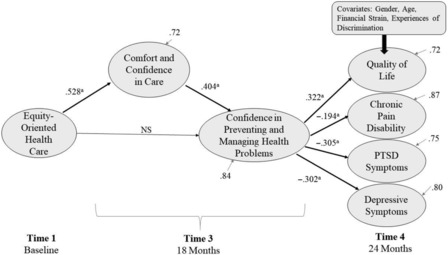

Figure 2 shows the results of testing the final model. The model fit significantly better than a fully saturated model (χ2 = 63.73, p < .001) and explained 47.7% of the variance in the data. All of the hypothesized paths in the model were significant, with the exception of the path from EOHC to confidence in preventing and managing health problems. However, the indirect effect of EOHC on confidence in preventing and managing health problems was significant. Overall, the model explained 27.8% of the variance in quality of life, 24.8% in PTSD symptoms, 19.6% in depressive symptoms, and 12.6% of the variance in chronic pain disability.

Figure 2.

Final Model With Standardized Path Coefficients

a= p < 0.05.

More EOHC at baseline was directly associated with greater comfort and confidence in care 18 months later (Time 3) (β = .5284, p < .001) and indirectly related to confidence in preventing and managing health problems 18 months later (Time 3) (β = .213, p < .001). In turn, greater confidence in preventing and managing health problems at Time 3 was significantly associated with better quality of life (β = .322, p < .001), less chronic pain disability (β = −.194, p < .001), and fewer PTSD symptoms (β = −.305, p < .001) and depressive symptoms (β = −.302, p < .001) 24 months after baseline (Time 4), controlling for age, gender, experiences of discrimination, and financial strain. The indirect effects of comfort and confidence in care through confidence in preventing and managing health problems were also significant for quality of life (β = .130, p < .001), chronic pain disability (β = −.078, p < .001), PTSD symptoms (β = −.123, p < .001), and depressive symptoms (β = −.1223, p < .001).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that making an explicit effort to provide equity‐oriented health care (EOHC) in primary care contexts may improve patients’ health outcomes over time. Using longitudinal data from a cohort of 395 patients facing significant health and social inequities, our study demonstrates that patients who experienced more EOHC had greater comfort and confidence in the health care services they received, which led to higher levels of confidence in their ability to manage and prevent health problems. Higher levels of confidence, in turn, strongly predicted improvements in depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and quality of life; the relationship with pain disability was less strong, although still statistically significant. To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide evidence of causal linkages between level of EOHC, an emerging concept, and patients’ self‐reported health outcomes through a process that includes both patients’ experiences of health care and their capacities to address health concerns. These results address a significant gap in understanding how attention to equity at the point of care can positively shape patients’ health, extending the evidence supporting the benefits of health equity interventions typically delivered at a population level to also include equity‐oriented clinical encounters with patients in primary health care settings.

These promising results raise a number of issues related to the potential for primary health care organizations and providers to develop a capacity for EOHC and also regarding the structures that could support such an undertaking. Strategies to promote equity in patients’ care encounters can be inexpensive and easy to implement. Even small shifts such as changing signs displayed in a space or adjusting language and tone used with patients to convey acceptance and respect can begin to enhance patients’ comfort and confidence, particularly for those who live with significant adversity, stigma, and discrimination, while also improving staff members’ confidence in their work.41

Despite being inexpensive to implement, these types of changes require both providers’ and organizations’ foundational understanding of and commitment to equity‐oriented health care and its key dimensions (trauma‐ and violence‐informed care, cultural safety, and contextually tailored care). As we have reported elsewhere,40, 41 at a minimum, a process of organizational change, which includes staff education and a review of organizational practices and policies to bring them in line with the key dimensions of EOHC, can be a powerful driver of change but also can disrupt the way that care is conceived and provided, at least in the short term.

The concept of disruption emerged strongly in our implementation of the EQUIP intervention, one approach for promoting the uptake of EOHC, and is fully explored in a companion article.41 Briefly, we learned that organizations engaging in this process should expect, plan for, and respond constructively to short‐term disruptions by focusing on the positive and productive aspects of disruption and linking positive disruption to concepts such as innovation, ingenuity, and interdependence in efforts to reap the collective benefits of EOHC for both clients and staff. Despite short‐term disruptions, the potential to enhance the health care experiences and health of those people at greatest risk of poor health justifies adopting EOHC universally.

Implementing EOHC has potential to increase marginalized patients’ access to primary and preventive care in ways that can improve their health outcomes and substantially reduce their health care costs.5, 6 The ability to achieve long‐term improvements in health for populations experiencing health and social inequities could substantially reduce the social and systems costs of disability while improving quality of life. For example, Padula and colleagues have shown that following patients’ preferences even when they depart from clinical guidelines is cost‐effective.91 Importantly, our results suggest that improving access to care is not enough, that even in the context of publicly funded universal health care, how health care is arranged and delivered matters to patients and influences health outcomes. Nonetheless, changes like these may be difficult to maintain in systems that undervalue issues of equity in favor of efficiency without concomitant attention to effectiveness.7

Metzl and Hansen66 call for those in health care to develop structural competence, involving not only understanding and addressing the effects of structural arrangements on health and health care but also including structural humility in which providers recognize the limits of their ability to influence these arrangements. While the focus of EOHC is not shifting the social determinants of health at a population level, at the individual level, providers can be encouraged to deliver care that explicitly links patients to appropriate social and economic supports and to see this as an important part of their role. We should also note that key individual‐level contextual factors, including financial strain and experiences of discrimination, continued to exert negative effects on health. Financial strain was the strongest predictor of poor health outcomes, with experiences of discrimination also playing a significant role. These results are important for 2 related reasons. First, health care leaders and providers need to be aware of the powerful influences of income and discrimination on health and to integrate poverty reduction and antidiscrimination strategies as a routine part of good care.7 Second, they must manage their own expectations of what can be achieved, so as not to be overwhelmed by the scale of the challenges of achieving equitable health outcomes for all.

The concept of EOHC, including trauma‐ and violence‐informed care, cultural safety, and tailoring to context, has allowed us to operationalize the key social justice principles underpinning the broad concept of health equity into strategies relevant at the point of care.92 Further work is needed to more fully understand the influence of harm reduction approaches in primary health care, a philosophy and a set of services focused on preventing the harms of substance use, which align and overlap with these key dimensions of EOHC.41

Limitations and Further Research

While the current study provides statistical evidence of the associations between concepts in the model in a specific population, the concept of EOHC as we have defined it is still quite new. Future research is needed to test models like these with varied populations and to test whether equity‐oriented health care is effective in shifting patients’ immediate and longer‐term outcomes using comparative designs. Given that experiences of discrimination in everyday life were moderately associated with both the levels of EOHC and comfort and confidence in care in this study, whether EOHC can ameliorate some of the negative effects of experiences of discrimination needs to be more fully examined.

In addition, the Equity‐Oriented Health Care Scale (E‐HoCS) was designed for this study. While it is a promising measure, it requires further testing in varied settings and populations and its potential utility as a tool for continuous quality improvement (CQI) needs to be studied. Furthermore, although responsibility for EOHC rests with both individual health care providers and the organizations in which they work, because the E‐HoCS is based on patients’ self‐reports, it captures their perceptions of clinical encounters with staff and does not necessarily examine the organizational context in which this care is provided. Finally, whether EOHC adds benefit to more privileged patients over and above high‐quality, patient‐centered care (however defined) is not known.

The evidence for EOHC is just starting to emerge; much more research is needed to continue to examine its efficacy and effectiveness for patients, providers, organizations, and systems. We conducted this study in clinics with an explicit commitment to serving those living in highly marginalizing conditions and a commitment to equity—characteristics that may not be shared to the same extent by more mainstream primary health care services. Although these values may also affect the nature of “usual care” provided in these clinics, as we have described elsewhere,93 these clinics also struggled with challenges, including staff recruitment and retention and support for professional development. As a result, at the beginning of this study, few staff had engaged in education or training related to the key dimensions of EOHC. We do not know with certainty whether or how these clinics’ particular characteristics affect our results. Testing the model in other contexts will be an important step in understanding the processes through which EOHC may affect patients’ reported health outcomes in a range of settings.

Conclusion

Despite calls to integrate attention to equity in health care provision, the lack of systematic and supportive policies, frameworks, and structures for EOHC delivery and monitoring94 makes action difficult.95 Adopting a systems approach is critical to supporting such change. Indeed, as we describe elsewhere,93 funding and policy contexts profoundly shaped the possibilities for EOHC in our participating clinics. But as evidence emerges demonstrating that EOHC leads to improvements in key patient health outcomes, the case for equity will be easier to make. As an approach to care, equity‐oriented health care has a potential “win‐win‐win” payoff: patients receive better care and have better health; staff and organizations provide better care, potentially leading to such things as improved staff retention; and systems and society benefit from possible reductions in costs and inequities and improved social well‐being. Systems approaches that integrate attention to equity at the point of care across sectors, with population‐level action on the determinants of health, may offer a promising way forward.

We are seeing considerable interest—at both practice and policy levels—in the concept of EOHC across primary health care and other sectors as we begin to disseminate the results of the EQUIP study through an online educational platform called the “Equipping for Equity Modules” (https://equiphealthcare.ca/modules/). These modules are available at no cost and provide information about the core features of EOHC, as well as multimedia tools and learning strategies to support individual providers and practices/organizations in adopting EOHC. This interest seems to be a promising indicator of receptivity to these concepts and to key findings from this study on the part of health care providers, organizations, and policymakers alike.

Funding/Support

The EQUIP Research Program is funded through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant: Programmatic Grants to Tackle Health and Health Equity [#ROH‐115210] (www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All the authors completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts were reported.

Acknowledgments: We thank both the participants who contributed so generously to the data reflected in this article and the clinics with which we collaborated. We thank our EQUIP research team of coinvestigators, knowledge users, and clinical leaders, listed alphabetically: Patty Belda, Kathy Bresett, Pat Campbell, Margaret Coyle, Anne Drost, Myrna Fisk, Olive Godwin, Irene Haigh‐Gidora, Colleen Kennelly, Murry Krause, Marjorie MacDonald, Wendy McKay, Tatiana Pyper, David Tu, Leslie Varley, Cheryl Ward, and Elizabeth Whynot. We also thank Phoebe Long, Joanne Parker, Joanne Hammerton, and Janina Krabbe for their outstanding contributions as research managers on the EQUIP Research Program, and Kelsey Timler, Catherine Blake, Mary Beth Davies, and Meghan Fluit for their work as research assistants.

References

- 1. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429‐445. 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farmer P. Reimagining equity In: Weigel J, ed. To Repair the World: Paul Farmer Speaks to the Next Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2013. http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520275973. Accessed August 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krieger N. Discrimination and health. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(4):643‐710. 10.2190/HS.44.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Global Health Action. 2015;8(1):27106 10.3402/gha.v8.27106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Collaborating Center for the Determinants of Health . Economic arguments for shifting health dollars upstream: a discussion paper Antigonish, NS: National Collaborating Center for the Determinants of Health; 2016. http://nccdh.ca/images/uploads/comments/Economic_Arguments_EN_April_28.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743‐800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baum FE. Health systems: how much difference can they make to health inequities? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(7):635‐636. http://jech.bmj.com/content/jech/70/7/635.full.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liburd LC, Giles W, Jack L. Health equity. Natl Civic Rev. 2013;102(4):52‐54. 10.1002/ncr.21156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marmot M, Bell R. Social inequalities in health: a proper concern of epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(4):238‐240. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wyatt R, Laderman M, Botwinick L, Mate K. Achieving health equity: a guide for health care organizations Cambridge, MA: IHI White Paper; 2016. https://scholar.google.ca/scholar?cluster=10865636512668944860&hl=en&as_sdt=2005&sciodt=0,5. Accessed August 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development . Focus on top incomes and taxation in OECD countries: was the crisis a game changer? Paris, France: OECD; 2014. http://www.oecd.org/social/OECD2014-FocusOnTopIncomes.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2017 . [Google Scholar]

- 12. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development . OECD Better Life Index: Canada; 2013. http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/canada/. Accessed August 8, 2017.

- 13. Wong WF, LaVeist TA, Sharfstein JM. Achieving health equity by design. JAMA. 2015;313(14):1417 10.1001/jama.2015.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canadian Institute for Health Information . Trends in income‐related health inequalities in Canada: technical report Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2017. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/trends_in_income_related_inequalities_in_canada_2015_en.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raphael D. Poverty in Canada: Implications for Health and Quality of Life. 2nd ed Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2011. https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GMKrYpb_kMsC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Raphael+D.+Poverty+in+Canada:+Implications+for+health+and+quality+of+life.+2nd+ed.+Toronto,+Canada:+Canadian+Scholars%27+Press%3B+2011.&ots=sEqhNesnLP&sig=ZWElXadK5RNqb8LNfalSOI5LZqc. Accessed August 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social determinants of health equity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl. 4). 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Embrett MG, Randall GE. Social determinants of health and health equity policy research: exploring the use, misuse, and nonuse of policy analysis theory. Soc Sci Med. 2014;108:147‐155. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. White F. Primary health care and public health: foundations of universal health systems. Med Principles Pract. 2015;24(2):103‐116. 10.1159/000370197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin MP, White MB, Hodgson JL, Lamson AL, Irons TG. Integrated primary care: a systematic review of program characteristics. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(1):101‐115. 10.1037/fsh0000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richard L, Furler J, Densley K, et al. Equity of access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations: the IMPACT international online survey of innovations. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15 10.1186/s12939-016-0351-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newman L, Baum F, Javanparast S, O'Rourke K, Carlon L. Addressing social determinants of health inequities through settings: a rapid review. Health Promotion Int. 2015;30(Suppl. 2):ii126‐ii143. 10.1093/heapro/dav054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. 2006. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43943/1/9789241563703_eng.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2017.

- 23. Canadian Institute for Health Information . Trends in income‐related health inequalities in Canada: technical report Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/trends_in_income_related_inequalities_in_canada_2015_en.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lebrun‐Harris LA, Baggett TP, Jenkins DM, et al. Health status and health care experiences among homeless patients in federally supported health centers: findings from the 2009 patient survey. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(3):992‐1017. 10.1111/1475-6773.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936‐944. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wuest J, Merritt‐Gray M, Ford‐Gilboe M, Lent B, Varcoe C, Campbell J. Chronic pain in women survivors of intimate partner violence. J Pain. 2008;9(11):1049‐1057. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=c8h&AN=2010118410&site=ehost-live. Accessed September 4, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frenkel L, Swartz L. Chronic pain as a human rights issue: setting an agenda for preventative action. Global Health Action. 2017;10(1):1348691 10.1080/16549716.2017.1348691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eriksen AMA, Schei B, Hansen KL, Sørlie T, Fleten N, Javo C. Childhood violence and adult chronic pain among indigenous Sami and non‐Sami populations in Norway: a SAMINOR 2 questionnaire study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75(1):32798 10.3402/ijch.v75.32798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fuller‐Thomson E, Baird SL, Dhrodia R, Brennenstuhl S. The association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and suicide attempts in a population‐based study. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(5):725‐734. 10.1111/cch.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stockman JK, Hayashi H, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women. J Women's Health. 2015;24(1):62‐79. 10.1089/jwh.2014.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seng JS, Lopez WD, Sperlich M, Hamama L, Reed Meldrum CD. Marginalized identities, discrimination burden, and mental health: empirical exploration of an interpersonal‐level approach to modeling intersectionality. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2437‐2445. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization . The World Health Report 2008—Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people's perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1011‐1017. 10.1007/s11606-007-0183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nelson SE, Wilson K. The mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:93‐112. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):157‐168. 10.1177/1359105311414952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tower M, Rowe J, Wallis M. Reconceptualising health and health care for women affected by domestic violence. Contemp Nurse. 2012;42(2):216‐225. 10.5172/conu.2012.42.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Giblon R, Bauer GR. Health care availability, quality, and unmet need: a comparison of transgender and cisgender residents of Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):283 10.1186/s12913-017-2226-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Institute of Medicine . The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. doi: 10.17226/13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, Second Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well‐Being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Toronto, ON: Wellesley Institute; 2015. http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Summary-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment-Final.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, et al. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: evidence‐based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):544 10.1186/s12913-016-1707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Ford‐Gilboe M, et al. Disruption as opportunity: impacts of an organizational health equity intervention in primary care clinics. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:154 10.1186/s12939-018-0820-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Ford‐Gilboe M, Wathen CN. EQUIP Healthcare: an overview of a multi‐component intervention to enhance equity‐oriented care in primary health care settings. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):152 10.1186/s12939-015-0271-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ponic P, Varcoe C, Smutylo T. Trauma‐ (and violence‐) informed approaches to supporting victims of violence: policy and practice considerations Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 9. Ottawa, ON: Department of Justice; 2016. 10.1080/09515070701685713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, et al. Closing the health equity gap: evidence‐based strategies for primary health care organizations. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):59 10.1186/1475-9276-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mental Health Commission of Canada . Guidelines for Recovery‐Oriented Practice. Ottawa, ON: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2015. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2016-07/MHCC_Recovery_Guidelines_2016_ENG.PDF. Accessed November 20, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient‐centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4‐15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient‐centered care and outcomes. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(4):351‐379. 10.1177/1077558712465774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ratanawongsa N, Federowicz MA, Christmas C, et al. Effects of a focused patient‐centered care curriculum on the experiences of internal medicine residents and their patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(4):473‐477. 10.1007/s11606-011-1881-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mohammed K, Nolan MB, Rajjo T, et al. Creating a patient‐centered health care delivery system. Am J Med Quality. 2016;31(1):12‐21. 10.1177/1062860614545124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee Y‐Y, Lin JL. Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient‐centered care to patient–physician relationships and health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(10):1811‐1818. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fredericks S, Lapum J, Hui G. Examining the effect of patient‐centred care on outcomes. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(7):394‐400. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.7.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient‐centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796‐804. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11032203. Accessed September 7, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356‐373. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lie DA, Lee‐Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):317‐325. 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Varcoe C, Browne AJ, Ford‐Gilboe M, et al. Reclaiming our spirits: a health promotion intervention for Indigenous women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(3):237‐254. 10.1002/nur.21795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hanefeld J, Powell‐Jackson T, Balabanova D. Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:368‐374. 10.2471/BLT.16.179309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Njue SM, Giordano TP. Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor‐patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17 10.1186/s12909-017-0868-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hawe P. Minimal, negligible and negligent interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;138:265‐268. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bandura A. Self‐efficacy: toward a unifying concept of behavioural change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jones F, Riazi A. Self‐efficacy and self‐management after stroke: a systematic review. Disability Rehabil. 2011;33(10):797‐810. 10.3109/09638288.2010.511415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(4):660‐680. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):323‐344. 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Campbell C, Mannell J. Conceptualising the agency of highly marginalised women: intimate partner violence in extreme settings. Global Public Health. 2016;11(1‐2):1‐16. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1109694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Frohlich KL, Corin E, Potvin L. A theoretical proposal for the relationship between context and disease. Sociol Health Illness. 2001;23(6):776‐797. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9566.00275. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Giddens A. Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure and Contradictions in Social Analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126‐133. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wong S, Haggerty J. Measuring patient expereinces in primary health care: a review and classification of items and scales used in publicly‐available questionnaires Vancouver: University of British Columbia Center for Health Services and Policy Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bandura A. Self‐Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Da Rocha NS, Power MJ, Bushnell DM, Fleck MP. The EUROHIS‐QOL 8‐item index: comparative psychometric properties to its parent WHOQOL‐BREF. Value in Health. 2012;15(3):449‐457. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schmidt S, Mühlan H, Power M. The EUROHIS‐QOL 8‐item index: psychometric results of a cross‐cultural field study. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(4):420‐428. 10.1093/eurpub/cki155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. WHOQOL Group . Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL‐BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551‐558. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9626712. Accessed September 15, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mallen C, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Severely disabling chronic pain in young adults: prevalence from a population‐based postal survey in North Staffordshire. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2005;6(1):42 10.1186/1471-2474-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tiwari A, Fong DYT, Chan C‐H, Ho P‐C. Factors mediating the relationship between intimate partner violence and chronic pain in Chinese women. J Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28(5):1067‐1087. 10.1177/0886260512459380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wuest J, Ford‐Gilboe M, Merritt‐Gray M, et al. Abuse‐related injury and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder as mechanisms of chronic pain in survivors of intimate partner violence. Pain Med. 2009;10(4):739‐747. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM. PCL‐C for DSM‐IV. Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD – Behavioral Science Division; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depression Anxiety. 2011;28(7):596‐606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Blanchard EB, Jones‐Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669‐673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Eaton WW. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD‐R) In: Maurish ME, ed. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Revised (CESD‐R): pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(1):128‐132. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shariff‐Marco S, Breen N, Landrine H, et al. Measuring everyday racial/ethnic discrimination in health surveys: how best to ask the questions, in one or two stages, across multiple racial/ethnic groups? Review. 2011;8(1):159‐177. doi:10.10170S1742058X11000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]