Abstract

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology is driven by community interests and rooted in community involvement throughout the research process. This paper describes the use of CBPR methodology in the HEAAL project (Health and Mental Health Education and Awareness for Africans in Lowell), a research collaboration between Christ Jubilee International Ministries – a nondenominational Christian church in Lowell, Massachusetts that serves an African immigrant and refugee congregation – and the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry. The objective of the HEAAL project was to better understand the nature, characteristics, scope and magnitude of health and mental health issues in this faith community. The experience of using CBPR in the HEAAL project has implications for research practice and policy as it ensured that research questions were relevant and meaningful to the community; facilitated successful recruitment and navigation through challenges; and can expedite the translation of data to practice and improved care.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, mental health, immigrant and refugee health

INTRODUCTION

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology is defined by the active involvement of community members at every stage of the research process. This article describes the use of CBPR methodology in the HEAAL project (Health and Mental Health Education and Awareness for Africans in Lowell), a research collaboration between the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Department of Psychiatry and Christ Jubilee International Ministries – a nondenominational Christian church in Lowell, Massachusetts that serves a predominantly African immigrant and refugee congregation. The first step in this research collaboration was to conduct a needs assessment, using CBPR methodology, to better understand the nature, characteristics, scope and magnitude of health and mental health issues of immigrants and refugees of African descent in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a research methodology driven by community interests and rooted in maintaining active community involvement throughout the research process.1 CBPR has also been described as an epidemiologic framework that can guide researchers’ understanding of the socioecological context of communities.2 Horowitz and colleagues (2009) advise that CBPR initiatives must be designed and implemented in a way that achieves balance between research methods that are both scientifically rigorous and not overly burdensome to the community.3 CBPR’s emphasis on relationship building between academic, medical and community partners holds significant promise for bridging the gap between scientific research and community implementation.4,5

While CBPR methodology does not have a singular set of prescribed steps, Minkler & Wallerstein (2011) outline a number of central tenets of CBPR. These include building upon existing community strengths and resources; facilitating collaborative and equitable partnerships; emphasizing health problems of local relevance; promoting co-learning and capacity building for all partners; and commitment to long-term and sustainable collaboration.1

Application of CBPR in Diverse Communities

CBPR’s emphasis on community participation and bidirectionality helps build trust between researchers and the community.6,7 This is especially necessary in working with African American communities who have experienced historical abuses, often at the hands of health researchers.8 The inclusiveness of CBPR helps prevent discriminatory and abusive research practices, facilitates community empowerment and begins to address social inequalities.9

CBPR has been used in mental health research initiatives in African American and Hispanic communities where trust is essential to the collection of accurate, comprehensive data on this highly stigmatized topic.7,10,11,12,13 As natural community epicenters, churches are well-suited community partners for health research and African American churches in particular have a strong history of community engagement and health promotion.14 A review of church-based general health interventions found that collaborative principles of CBPR in which the church was an active part of program design and implementation were most effective in building sustainable health resources.14,15

The HEAAL Project

Lowell, Massachusetts is home to a large population of Liberian immigrants and refugees, many of whom are congregants of Christ Jubilee International Ministries. In 2009, MGH researchers hired several Liberian congregants to transcribe interviews from a series of qualitative studies conducted by the MGH team with children and adults in Monrovia, Liberia.16 As the congregants transcribed the stories of their countrymen, they recognized many of these mental health issues, stigmas and beliefs were pervasive in their own community, yet very few were accessing mental health services. The HEAAL project was born as a result of this community-identified need to understand and characterize their own mental health, in order to inform the development of mental health resources tailored to the community’s needs. The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee (PHRC) Institutional Review Board (IRB) in May 2014.

METHODS

Establishing the Community Advisory Board (CAB)

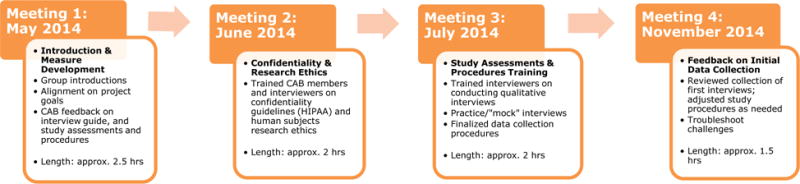

A successful research partnership requires strong relationships with community leadership.17 Most CBPR initiatives establish a steering committee or advisory board, which serves as the central mechanism for continuous community involvement by providing input at each step of the research process.18 The HEAAL project Community Advisory Board (CAB) included eleven members of Christ Jubilee, eight females and three males, who were identified by the pastor and the church’s health coordinator. The majority (7) of the CAB members were Liberian, while the other members were from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Haiti. The nationalities represented on the CAB reflected the composition of the congregation, which is also predominantly Liberian but with individuals from diverse African and Caribbean nations. The HEAAL project needs assessment study was developed and implemented through a series of four CAB meetings held between May and November 2014 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Four Community Advisory Board (CAB) meetings for the HEAAL project between May and November 2014.

The inaugural meeting included all eleven CAB members and members of the MGH research team. After group introductions and a discussion of common goals for the collaboration, the remainder of the 2.5-hour meeting focused on obtaining the CAB’s input on the study procedures and the proposed study assessments – one qualitative interview and four quantitative surveys – to ensure that all were culturally appropriate, feasible and minimally burdensome on the community. This meeting was digitally recorded so the community’s feedback could be incorporated quickly and accurately.

In the second CAB meeting, MGH team members trained six of the CAB members, who would also be interviewers in the study, on confidentiality and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) regulations and mandated reporting. They were given 24/7 contact information of the MGH study physicians should they encounter an incident that required mandated reporting.

In the third meeting, MGH team members trained the six interviewers to conduct qualitative interviews, including effective probing techniques, and to administer the two quantitative assessments: the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation (BACE) and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSC-25). The interviewers practiced mock interviews with guidance from the MGH research team. They were trained to obtain informed consent, with particular emphasis on confidentiality protections. Finally, interviewers were trained on the logistical aspects of the protocol, including completion of the enrollment log, participant remuneration and using the audio recorders.

The fourth CAB meeting was held after the first twelve interviews were completed in order to address challenges and share successes. The group set a recruitment completion goal of approximately 50 interviews by Dec. 31, 2014.

RESULTS

Meeting 1: Developing Study Measures and Processes

The introductory discussion allowed the HEAAL team to launch the project from a place of common understanding, set a precedent for open communication and begin building trust. This first meeting was also critical in obtaining extensive feedback on the study assessments and procedures to ensure cultural-appropriateness and feasibility. The primary study assessment was the qualitative, semi-structured interview guide, which asked participants about perceptions of physical and mental health, cultural expressions of distress and barriers to care. Select CAB feedback on the qualitative interview guide is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Select feedback from first CAB meeting, May 2014

| Topic | CAB Feedback | Revision |

|---|---|---|

| Questions asking for firsthand perspective (E.g. How much alcohol do you drink?) | Phrase question such that it is depersonalized. Participant can share observations while still protecting their status or reputation. | From your observations, how much alcohol do people drink in your community? |

| Clinical interview style. Reading questions verbatim. | Too stiff and formal. Participants may feel afraid, distrustful or nervous. | Use a more conversational interview style. Establish rapport and give assurance of confidentiality during consent. |

| Who should conduct interviews? | Trained church community/CAB members. Existing trust and level of comfort. | Six members of CAB volunteered to be interviewers and conducted a total of 53 interviews. |

| Terminology | CAB Feedback | Revision |

| “Mental” | Term associated with severe mental illness; psychosis, very abnormal, stigmatized. Use term “emotional.” | “What are the most common emotional problems in your community?” |

| “Anxiety” | Too clinical and stigmatized. Use “worry” or “stress.” | “Have you felt worried or stressed? Has this affected your sleep, eating, daily activities?” |

| “Depression” | Too clinical and stigmatized. Use “down” or “sad.” | “Have you felt down or sad? Has this feeling affected your sleep, eating, daily activities?” |

| “Psychiatrist” | Too clinical and stigmatized. Use “mental health provider” or just “doctor.” | “Have you ever talked to a mental health provider? Have you ever asked your doctor about emotional problems?” |

| “Traditional medicine” | “Traditional medicine” is discouraged in some Christian denominations so participants may not endorse usage, especially within a church. Ask about “natural” or “herbal” remedies instead. | “How do you or others in your community use natural or herbal remedies?” |

Much of the CAB’s feedback on the interview guide discussed strategies to increase participants’ comfort with the sensitive interview topics. They emphasized the importance of beginning the interview in a “conversational” tone, as a “formal” or “clinical” tone would be associated with discomfort and distrust. The CAB also emphasized the importance of describing the confidential nature of the research, ensuring that participants were aware of their right to refuse to answer questions and to end their participation at any time for any reason. The CAB also provided input on specific terminologies to avoid due to their negative cultural connotations, which might prevent participants from openly sharing their experiences (See Table 1). The qualitative interview guide was revised to incorporate this feedback and was sent to each CAB member for final review and approval.

The CAB also reviewed the four quantitative assessments initially proposed for the study and advised that two should be removed due to their length. The two quantitative assessments selected for inclusion were the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation (BACE)19 and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25).20,21,22

The CAB provided significant feedback into the study procedures and logistics. Some members felt strongly that interviewers should be members of Christ Jubilee because participants would feel more comfortable sharing sensitive health information with fellow community members. Others argued that participants would be less likely to share personal details with fellow community members for fear that their information might be disclosed. Ultimately, the group decided that community members would be trained as interviewers and would emphasize confidentiality protections in their communication with participants. It was further determined that the interviewers would be compensated for their time. Six of the eleven CAB members, five females and one male, volunteered to be interviewers for this study. Finally, the CAB identified that the most effective and least burdensome recruitment methods to be posting fliers at the church with the contact information of an MGH research team member and making announcements at church services.

Meetings 2 and 3: Trainings in Confidentiality and Research Ethics and Study Assessments and Procedures

The outcomes of meetings 2 and 3 were primarily achieved during the trainings themselves, as described in the methods section. However, after meeting 2, each interviewer completed human subjects research ethics certifications and was added to the IRB protocol as study staff. After meeting 3, the data collection packets, including step-by-step procedural instructions, were revised based on CAB feedback and distributed to interviewers. There were no mandated reports made during the study.

Meeting 4: Interviewer Feedback on Initial Data Collection

The interviewers endorsed a number of successes, including strong community interest in study participation and accelerated recruitment. The qualitative interviews lasted between 35 and 50 minutes, which felt comfortable for both participants and interviewers. Interviews were conducted on Mondays through Sundays and all interviews took place at the church. As the CAB had anticipated, a key challenge was participants’ frequent concerns about confidentiality. However, the interviewers felt that the consent process and their training on confidentiality successfully allayed participants’ apprehension. Many participants enjoyed the interview process because they felt they were making a contribution to their community.

DISCUSSION

The use of CBPR methodology was critical to the successful development and implementation of the HEAAL project needs assessment: the study team completed 53 interviews in two months. The CAB’s input into the interview design, questions and language ensured that their fellow community members would feel safe and comfortable while discussing sensitive topics. The project also exposed this community to a health research methodology in which their voice is heard, respected and valued. Such methodologies can help rebuild trust between historically marginalized communities and the field of health research.3,6

While CBPR methodology can be applied in many settings, a limitation is that research findings may not be generalizable beyond the community context, as the research goals, measures, study design and implementation are intentionally tailored to the unique community under study. However, the HEAAL project’s experience of using CBPR to identify health needs, while building the community’s capacity to understand and work towards addressing these needs, demonstrates how CBPR could be used to build capacity, address disparities and strengthen community advocacy in diverse health initiatives, particularly those in minority communities.4,5,9

Another challenge was the time commitment required by the CAB and especially the CAB interviewers, most who held full-time employment. CBPR requires flexibility and respect for community partners’ time such that their participation does not impact other priorities and commitments and they are fairly compensated for their contributions to the project.3,23,24 The MGH team attempted to accommodate CAB members’ schedules by holding meetings on the weekends, often directly after Sunday church services. While CAB members generously donated their time for the project, the interviewers were each compensated with a $200 Visa gift card.

Next Steps

Since the completion of data collection, the research team has continued to analyze the data, while simultaneously pursuing additional funding to support the design and implementation of community-based health resources and programs informed by these data. Such health programs will be developed in collaboration between Christ Jubilee and the academic research team, which recently expanded to include Boston Medical Center and the Boston University School of Medicine. Preliminary health program ideas include a health fair and mental health education programs. Other health promotion activities will emerge as the academic and community members collaborate to analyze the data and identify areas of priority.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Involving the community in study development can ensure that research efforts are focused on topic areas that are meaningful to the community.

Engaged community leaders can act as project advocates within their community, facilitating recruitment efforts and navigation through barriers.

CBPR also necessitates the involvement of the community in intervention design, thereby assisting the transition from data collection to implementation.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude for the myriad contributions of our collaborators at Christ Jubilee International Ministries in Lowell, Massachusetts including Pastor Jeremiah Menyongai, MA and the members of the Community Advisory Board, including the six interviewers (indicated by asterisk), without whom this project would not exist: *Bernadette Chukwuezi, MA, *Dorothy Johnson, MA, *Severine Kouagheu, BSN, RN, *Christiana Onyeulo, *Seide Slopadoe, *Peter Wennah, MEd, Gessie Paul, MA, Jennie Morris, MA, Grace Boykai, RN, Barbara Jackson and Nathan Manyika.

Source of Funding: Theodore Edson Parker Foundation in Lowell, Massachusetts, provided funding for this research initiative. Dr. Borba’s effort on this project was supported by an NIMH career development award K01MH100428.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest declared by any of the authors.

Author Justification

Pastor Jeremiah Menyongai is the senior pastor at Christ Jubilee International Ministries in Lowell, Massachusetts and was a key leader and partner in the HEAAL project along with Sister Bernadette Chukwuezi, the health coordinator at Christ Jubilee. Both were members of the Community Advisory Board (CAB) whose widespread contributions to this research are detailed in this manuscript. Authors Oppenheim, Henderson and Borba were members of the research team from MGH subsequently from BU. Authors Tam and Axelrod are research team members from Boston Medical Center who contributed to the development of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the development and preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2. Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung MW, Yen IH, Minkler M. Community based participatory research: a promising approach for increasing epidemiology’s relevance in the 21st century. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(3):499–506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. Community-Based Participatory Research From the Margin to the Mainstream Are Researchers Prepared? Circulation. 2009;119(19):2633–2642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AKHG, Young S. Building and Maintaining Trust in a Community-Based Participatory Research Partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong EC, Chung B, Stover G, et al. Addressing unmet mental health and substance abuse needs: a partnered planning effort between grassroots community agencies, faith-based organizations, service providers, and academic institutions. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3 Suppl 1):S1-S107–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(7):951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-Based Participatory Research: A Capacity-Building Approach for Policy Advocacy Aimed at Eliminating Health Disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankerson SH, Watson KT, Lukachko A, Fullilove MT, Weissman M. Ministers’ perceptions of church-based programs to provide depression care for African Americans. J Urban Health. 2013;90(4):685–698. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9794-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabassa LJ, Gomes AP, Meyreles Q, et al. Using the collaborative intervention planning framework to adapt a health-care manager intervention to a new population and provider group to improve the health of people with serious mental illness. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0178-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray LK, Dorsey S, Bolton P, et al. Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: an apprenticeship model for training local providers. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michael YL, Farquhar SA, Wiggins N, Green MK. Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(3):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankerson SH, Weissman MM. Church-based health programs for mental disorders among African Americans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(3):243–249. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borba CPC, Ng LC, Stevenson A, et al. A mental health needs assessment of children and adolescents in post-conflict Liberia: results from a quantitative key-informant survey. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2016;9(1):56–70. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2015.1106569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams L, Gorman R, Hankerson S. Implementing a mental health ministry committee in faith-based organizations: the promoting emotional wellness and spirituality program. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53(4):414–434. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2014.880391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders PL. Community-Based Participatory Research. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR, editors. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Springer; New York: 2013. pp. 474–475. http://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_736. Accessed May 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clement S, Brohan E, Jeffery D, Henderson C, Hatch SL, Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parloff MB, Kelman HC, Frank JD. Comfort, effectiveness, and self-awareness as criteria of improvement in psychotherapy. AJP. 1954;111(5):343–352. doi: 10.1176/ajp.111.5.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hesbacher PT, Rickels K, J R, Newman H, Rosenfeld H. Psychiatric illness in family practice. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1980;41(1):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Saile R, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Validation of a mental health assessment in an African conflict population. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation. 2011;1(S):19. doi: 10.1037/2157-3883.1.S.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-Based Participatory Research: Implications for Public Health Funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1210–1213. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, et al. Challenges and Facilitating Factors in Sustaining Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships: Lessons Learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]