Abstract

Background

It has been hypothesized that the supply of chemical energy may be insufficient to fuel normal mechanical pump function in heart failure (HF). The creatine kinase (CK) reaction serves as the heart’s primary energy reserve, and the supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP flux) it provides is reduced in human HF. However, the relationship between the CK energy supply and the mechanical energy expended has never been quantified in the human heart. This study tests whether reduced CK energy supply is associated with reduced mechanical work in HF patients.

Methods

Cardiac mechanical work and CK flux in W/kg, and mechanical efficiency were measured noninvasively at rest using cardiac pressure-volume loops, magnetic resonance imaging and phosphorus spectroscopy in 14 healthy subjects and 27 patients with mild-to-moderate HF.

Results

In HF, the resting CK flux (126 ± 46 vs. 179 ± 50 W/kg, p < 0.002), the average (6.8 ± 3.1 vs. 10.1 ± 1.5 W/kg, p <0.001) and the peak (32 ± 14 vs. 48 ± 8 W/kg, p < 0.001) cardiac mechanical work-rates, as well as the cardiac mechanical efficiency (53% ± 16 vs. 79% ± 3, p < 0.001), were all reduced by a third compared to healthy subjects. In addition, cardiac CK flux correlated with the resting peak and average mechanical power (p < 0.01), and with mechanical efficiency (p = 0.002).

Conclusion

These first noninvasive findings showing that cardiac mechanical work and efficiency in mild-to-moderate human HF decrease proportionately with CK ATP energy supply, are consistent with the energy deprivation hypothesis of HF. CK energy supply exceeds mechanical work at rest but lies within a range that may be limiting with moderate activity, and thus presents a promising target for HF treatment.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00181259.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12968-018-0491-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Translational studies, Cardiac metabolism, Cardiac work, Heart failure, Magnetic resonance

Background

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent condition with a high mortality rate that often presents with symptoms of exercise intolerance, breathlessness, fatigue, and fluid retention due to cardiac pump dysfunction [1, 2]. Energy metabolism fuels contractile function in the normal heart and impaired energy metabolism has long been hypothesized as playing a central role in HF [3, 4]. The chemical energy supporting cellular processes derives from cleavage of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and progression to HF is associated with a declining capacity for myocellular ATP production [5] with the implication that the failing heart may be energy starved [3–9].

The primary myocardial energy reserve reaction for generating ATP is the creatine kinase (CK) reaction that reversibly transfers high-energy phosphate between phosphocreatine (PCr) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP). The pseudo-first-order forward reaction-rate constant for the CK reaction (kf) and the product of kf and the PCr concentration (kf.[PCr]), hereinafter called the ‘CK flux’, measure the forward rate of ATP production via CK. During periods of ischemia, PCr is consumed to maintain ATP levels, reducing the myocardial PCr/ATP ratio [10, 11]. Moreover, the CK reaction has long been hypothesized to serve as a spatial and temporal buffer of the energy transfer between mitochondria, where ATP is created via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and the myofibrils, where ATP fuels contraction [9, 12–15].

Phosphorus (31P) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) performed in clinical cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) scanners, is uniquely able to noninvasively measure the ratios and concentrations of endogenous cardiac high-energy phosphate metabolites, as well as CK flux in human hearts [8–11, 16–22]. In patients with HF and non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy or left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH), mean CK flux at rest can be reduced by up to 65% [8, 17], even when ATP levels are not significantly decreased. Importantly, these reductions in CK ATP supply are of a magnitude that could diminish energy availability during periods of peak cardiac demand, when peak ATP utilization is anticipated to be many-fold higher than the temporal-average ATP utilization [8, 17]. This would be consistent with the energy starvation hypothesis for HF [3–9], and could explain the observation that reduced cardiac CK flux is an independent predictor of adverse cardiac events and death [18]. However, the relationships between CK energy supply and the peak and average cardiac mechanical work in the healthy and failing human heart are unknown.

Here we combine noninvasive cine CMR volumetry with quantitative 31P MRS to measure both temporal cardiac mechanical work and CK energy supply in healthy subjects and patients with nonischemic HF who had reduced LV ejection fractions (EF). The data provide insight into whether the reduction in CK energy supplied to the failing heart could be sufficient to limit mechanical function, and hence provide a mechanistic rationale for targeting CK metabolism as a potential HF treatment [19]. The study tests the hypothesis that reduced temporal average and peak mechanical work is associated with reduced CK flux in HF patients.

Methods

Study subjects

We studied 27 patients over the age of 21 (age = 45 ± 14, mean ± SD yrs) with a history of HF (New York Heart Association, NYHA, class I-III) and reduced LVEF (≤45%) measured at a prior clinical imaging study using echocardiography, nuclear ventriculography, x-ray computed tomography or CMR. Subjects who had conventional contraindications to CMR, signficant valvular disease, or evidence of critical coronary disease (luminal stenosis > 50% as assessed by cardiac catheterization, computed tomography angiography, or positive stress nuclear or echocardiography) were excluded. Of the 27 patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy, the cause was familial in 3 patients (11%) and idiopathic in 24 (89%). Fourteen age-matched healthy subjects (age = 42 ± 18 yrs) with no history of heart disease, diabetes, or hypertension served as controls. The study was performed at the Johns Hopkins University and approved by its Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. All CMR and MRS studies were performed on a 3 Tesla scanner (Achieva, Philips Healthcare Best, the Netherlands) scanner equipped with 6- and 32-channel cardiac array coils and a 17-cm/8-cm 31P transmit/receive surface coil set [20]. The protocol for measuring CK energy supply and cardiac work is summarized in Fig. 1.

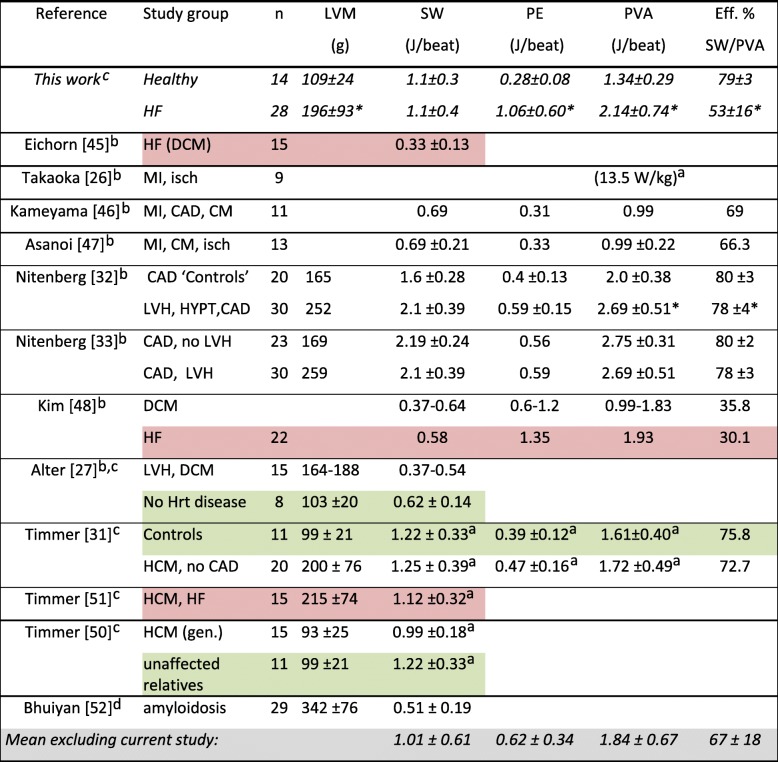

Fig. 1.

Noninvasive MRS/CMR protocol for studying cardiac energetics. a (bottom) 31P-MRS measurements of [PCr] and [ATP] concentrations in mmol/kg wet-weight using CMR volumetry and a concentration reference, is followed by triple repetition-time saturation-transfer (TRiST) measurements of the CK reaction rate, kf in s-1, to obtain the rate of ATP production, or CK flux. The CK flux in mmol/kg/s is converted to Système International (SI) units of W/kg to compare with the cardiac workload based on the free energy of ATP hydrolysis (ΔGATP) and the specific gravity (SG). b (top) CMR measurements of left ventricular volume, LV V(t), are combined with blood pressure (BP) cuff measures to determine the instantaneous p(t), average (pav) and peak (pp) mechanical power, and the stroke work (SW), potential energy (PE) and total mechanical energy (PVA) in Joules, Watts and W/kg (see Additional file 1). The energetics protocol takes about 50–75 min in total

CK metabolites and energy supply

Absolute anterior LV concentrations of [PCr] and [ATP] in mmol/kg wet weight, were determined in the anterior LV by 31P MRS from metabolite peak areas and an external concentration reference measured using the ‘Circle Fit’ method [23]. Concentrations were corrected for coil loading, relaxation, heart motion, tissue volume, [ATP] in ventricular blood, and coil sensitivity variations within voxels (Fig. 1a) [20]. The pseudo-first order rate-constant of the CK reaction, kf in s− 1, was measured using the triple repetition-time saturation-transfer (TRiST) method [21] with corrections for spillover irradiation [24, 25]. The CK flux was obtained from the product, kf [PCr] in mmol/kg/s, and converted to Système International (SI) units of Watts/kg wet-tissue weight (W/kg) by multiplying by the free-energy of ATP hydrolysis, ΔGATP. The latter was taken as 60 kJ/mol, being the mean of 59–61 kJ/mol determined previously from healthy and HF patients using the same methodology [8, 19]. The MRS protocols are detailed in the Additional file 1.

Cardiac work

Most of the energy consumed by the heart is expended in ejecting blood during systole with the kinetic energy of the departing blood representing less than 1% of the pump energy (see Additional file 1). The LV whose systolic pressure and mass (LVM) are many times those of the right ventricle, performs the bulk of the cardiac work, and is in any case, the target of our MRS CK flux measurements [8, 17–22]. Cardiac work was determined noninvasively in HF patients and healthy subjects from cardiac LV pressure-volume (PV) loops (Fig. 2).

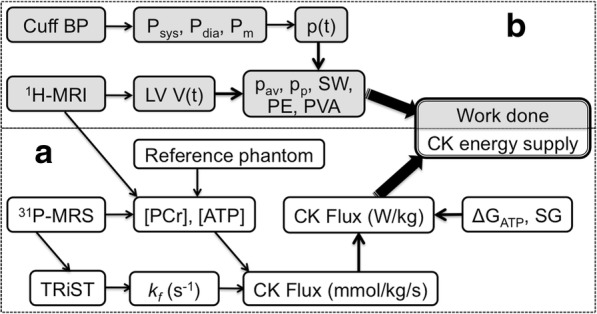

Fig. 2.

Pressure-volume schematic. The hemodynamic phases are traversed counterclockwise in one complete heart cycle (black-line). The area inside the right-hand loop defines the stroke work (SW), approximated by a rectangle (grey border); the potential energy (PE) is estimated by the end-systolic area under the grey triangle (left); and the pressure-volume area (PVA) is their sum, SW + PE. Ps and Pd are the systolic and diastolic pressures; ESV, EDV, V0, denote the end-systolic, end-diastolic and unstressed volumes, respectively

The time-dependent LV volume, V(t), was measured from cardiac cine CMR (Fig. 1b), using protocols also detailed in the Additional file 1. Pressure monitoring in the LV chamber requires an invasive LV catheter [26, 27] which was not feasible for these subjects. Instead, LV chamber pressure, P(t), was approximated by a step function scaled to the mean brachial arterial blood pressure (BP) during ejection. The PV work, w(t), was calculated from the pressure and temporal variation in LV volume, ∆V, as:

| 1 |

The mechanical stroke work (SW) performed by the left ventricle in one cardiac cycle was measured from the area within the PV-loop which represents the integral of Eq. (1) over one cardiac cycle [28]. The instantaneous mechanical power (or rate of energy consumption) was taken as the derivative of Eq. (1), [29]:

| 2 |

The internal cardiac ‘potential energy’ (PE) expended to stiffen the left ventricle prior to ejection, was estimated from the shaded region under the line connecting the end-systolic PV-point in the PV-loop (Fig. 2), to the totally unstressed volume, V0 at P = 0 [30]. As elsewhere [31], we set V0 = 0, a value supported by invasive studies perfomed with patients undergoing catheterization [32, 33]. The total mechanical energy (and work) was estimated by the sum, PVA = SW + PE, and the mechanical efficiency by SW/PVA [30, 34].

In addition to SW and PE, the LVM, EF and the end-diastolic (EDV), end-systolic (ESV), and stroke (SV) volumes were calculated from the MRI and BP measurements. The instantaneous mechanical power was calculated from the time-derivative of w(t) in SI units of Watts (Eq. 2). The average (pav) and peak (pp) cardiac power, their ratio, and the average and peak power normalized by LVM in W/kg, were then determined and compared to the CK energy supply in W/kg.

Two-sided unpaired t-tests were used to test for statistical differences between the mechanical and metabolic measurements in healthy subjects and HF patients in accordance with the primary hypothesis, with probability p < 0.05 considered significant. Pearson regression analysis was used to test for correlations between CK flux and cardiac work metrics.

Results

There were no significant differences in age, body mass index (BMI), heart-rate (HR) or systolic BP (Psys) between healthy and HF study subjects (Table 1), or with gender or race within groups. Among HF patients, diastolic pressure (Pdia) was higher in African Americans than in Caucasians (82 ± 13, n = 14 vs. 69 ± 14 mmHg, n = 13; p = 0.05). Cardiac LVM, EDV and ESV measured by CMR were respectively 1.8, 1.7 and 3.3 times higher in HF patients than in healthy subjects (p ≤ 0.002).

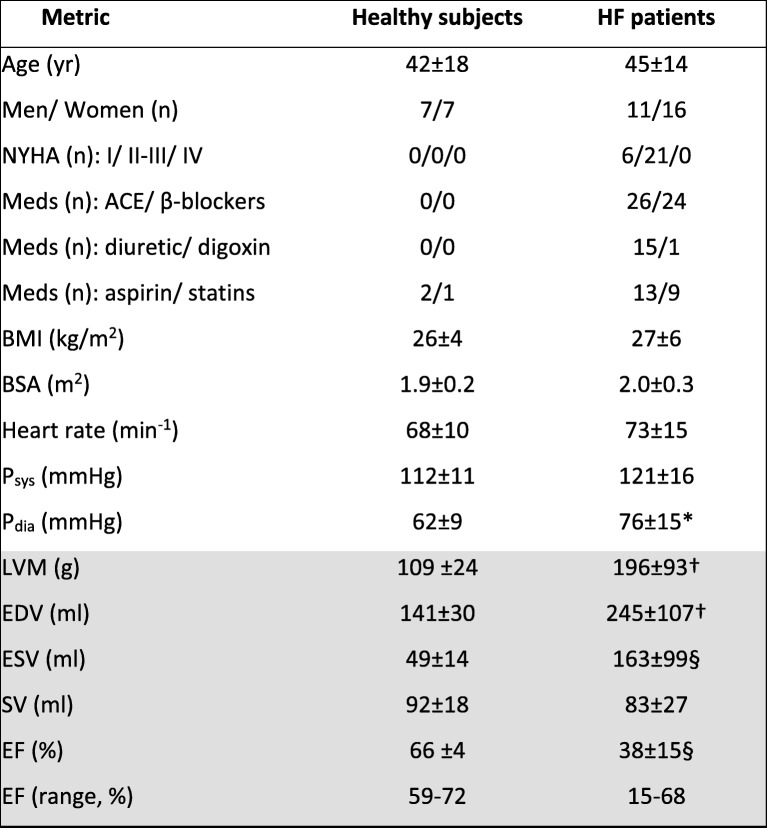

Table 1.

Characteristics of healthy and HF patients studied

Values are means ±standard deviation at the time of the MRI/MRS exam or numbers of subjects in each group (n). Psys and Pdia are the resting systolic and diastolic blood pressures; NYHA New York Heart Association HF class, Meds medications, BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area. LVM left ventricular mass, EDV, ESV and SV are the end-diastolic, end-systolic and stroke volumes respectively; and EF = ejection fraction, measured by CMR (shaded). *p < 0.01, †p < 0.002 and § p ≤ 0.0001 vs. healthy subjects (independent 2-tailed t-test)

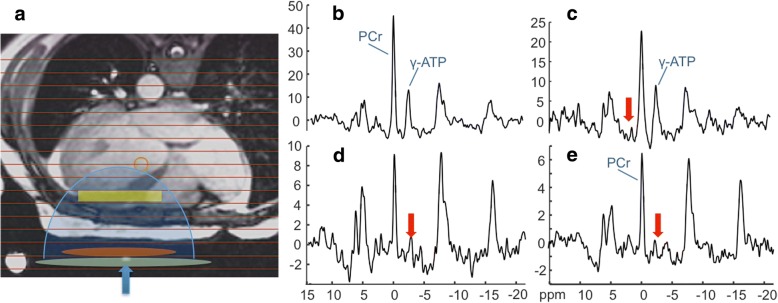

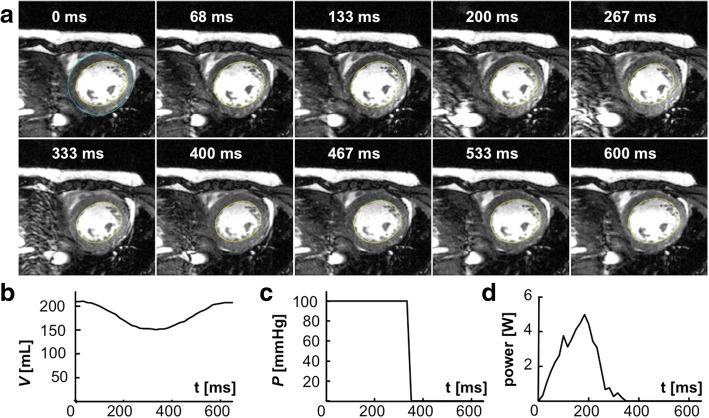

Figure 3 shows typical anterior LV 31P TRiST spectra from an LV section in a patient with NYHA class II HF. With the exchanging (γ-)ATP phosphate saturated (Fig. 3d,e) the PCr is reduced compared to the control spectrum (Fig. 2c) in proportion to kf [21], which was 0.25 s− 1. This patient’s cine CMR, modeled pressure, LV volume and power curves are depicted in Fig. 4: the peak and average power were 4.7 W and 1.2 W, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Typical 31P spectra from a patient with HF (age 45 yrs.; NYHA Class II). a Transaxial scout CMR delineating the MRS voxels (horizontal lines), and approximate locations for the transmit and receive coils (green and orange ellipses). The receiver coil’s region of sensitivity (blue shading) and an embedded coil marker (blue arrow) are also indicated. b Fully-relaxed spectrum from the yellow cardiac voxel in a, showing the PCr and ATP γ-phosphate peaks used for concentration measurements. c-e The TRiST experiment with MRS saturation (red arrows) at + 2.5 ppm as a control (c), and (d, e) at − 2.5 ppm to saturate the exchanging γ-ATP. The MRS repetition periods are 15.7 s, 9.7 s and 1.6 s in (c-e) respectively (see Additional file 1). The decrease in PCr in (d) vs. (c) is proportional to the CK reaction rate, kf (note change in vertical intensity). The total scan time for these acquisitions was about 45 min

Fig. 4.

CMR and the LV volume, pressure and power waveforms for the HF patient in Fig. 3. a Short-axis images acquired at different times post-diastole (labeled), in a multi-slice 30-phase steady-state free-precession cine CMR (see Additional file 1). The endocardial borders used for quantifying SV are outlined in yellow (the epicardial border is blue in the first frame. b The volume waveform, c the scaled pressure model, and d the resulting mechanical power waveform for this patient

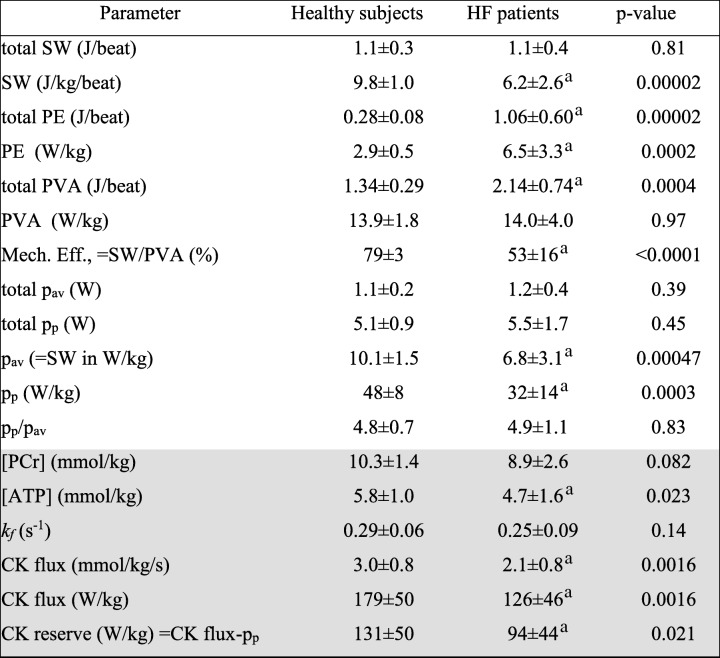

Table 2 summarizes the mechanical and metabolic measurements from healthy subjects and HF patients. While the total SW (in Joules/beat) was preserved in HF, normalization by LVM reduced it by 33% compared to that of the healthy subjects. Potential energy, PE (Joules), was about four times higher in HF and remained double that of healthy subjects after normalization by LVM. Consequently, the total energy, PVA (Joules/beat), was 1.6-fold higher in HF patients, whereas the normalized PVA in W/kg was similar for the two groups. Because of the higher PE, mechanical efficiency (SW/PVA), was reduced by a third in HF patients (53% vs 79% in healthy subjects, p < 0.001). When normalized by LVM, both average and peak power were significantly reduced by 30–40% in failing compared to healthy hearts (pav = 6.8 W/kg vs. 10.1 W/kg; pp = 32 W/kg vs. 48 W/kg, p < 0.0005 for both). However, because the fractional decrease in peak and average power were comparable, the peak-to-average ratio of cardiac stroke power at rest is actually the same in HF and healthy subjects, at ~ 4.8.

Table 2.

Metrics of of mechanical energy utilization and CK energy supply (shaded) measured in healthy and HF patients

Values are mean ± SD. aSignificantly reduced vs. healthy subjects. Abbreviations: SW stroke work, PE potential energy, PVA total mechanical energy; Mech. Eff. =mechanical efficiency; pav and pp are the average and peak stroke power, respectively; kf = pseudo-first-order creatine kinase (CK) reaction-rate rate constant. [PCr] and [ATP] are the respective concentrations of myocardial phosphocreatine and adenosine triphosphate

On the supply side, the concentrations of PCr and ATP and the CK rate-constant kf were all modestly reduced in HF patients by 13–19%. Consequently, the CK flux was significantly reduced by 32%, from 179 W/kg in healthy subjects to 126 W/kg in HF (p < 0.002). This was the same percentage reduction seen in the average and peak power in W/kg, and in mechanical efficiency. The difference between the resting CK energy supply and the normalized peak mechanical power–the CK energy reserve–was thus reduced from 131 W/kg in healthy subjects to 94 W/kg in HF (p = 0.02).

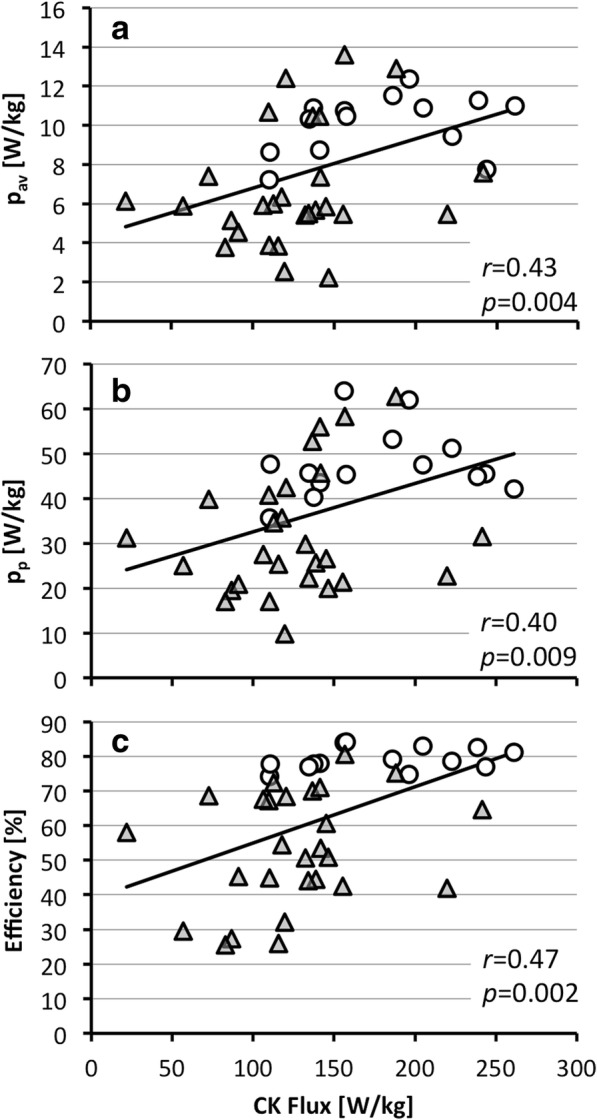

Regression analysis revealed significant correlations between the CK ATP energy supply and metrics of energy utilization (Fig. 5), namely, the average and peak power (pav, r = 0.43, p = 0.004; pp, r = 0.40, p = 0.009), the PE in Joules and W/kg (r = 0.37, p < 0.02; not shown), and the mechanical efficiency (r = 0.47; p = 0.002). Among HF patients, there were no significant differences in pav, PE, PVA, CK flux (all in W/kg) or efficiency when grouped by gender or race (p ≥ 0.09).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between mechanical energy and CK flux. a Average (pav) and b peak (pp) power, and c mechanical efficiency in healthy subjects (circles) and HF patients (triangles). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and their probabilities are indicated (standard errors were 2.79, 13.1 and 16.4 respectively)

Discussion

The hypothesis that the failing heart is energy-starved and that the CK reaction–the heart’s primary energy reserve reaction–is implicated, is longstanding [3–9]. The present study is the first to noninvasively document the magnitude of the CK energy supply relative to the energy required for mechanical contraction in the same human hearts. The results have important implications for the energetics of both the healthy and failing human heart.

First, the mean basal rate of ATP production via OXPHOS previously estimated from myocardial oxygen consumption using positron emission tomography or direct sampling of coronary blood flow in non-failing human heart, is about 0.4 μmol/g wet weight/s [8, 29, 35]. This translates to about 0.4 × 60 kJ/mol =24 W/kg, which at equilibrium must equal the average rate of total energy utilization. Thus our pav measurement of about 10 W/kg in healthy subjects at rest would be consistent with a 10/24 ≈ 40% OXPHOS-to-SW energy conversion rate, which falls within the 25–44% range reported previously from invasive studies of animals and humans [30, 36]. In healthy subjects, our mean forward CK flux of 3.0 ± 0.8 μmol/g wet weight/s is consistent with prior 31P MRS measures of fluxes and rates [8, 17–19, 22, 37, 38] and translates to an average normal CK flux of 179 W/kg (Table 2). This is 179/10.1 ≈ 18 times the time-averaged SW. However, when cyclic energy demand peaks at pp = 48 ± 8 W/kg (Table 2), the CK energy supply exceeds pp by just a factor of 179/48 = 3.7 in healthy resting subjects.

While CK flux might also vary cyclically, there is no evidence of cyclic PCr changes in the normal heart at rest [39]. Arguably, physiological changes in kf could not meaningfully register in time-frames much shorter than about 1/kf ≈ 3 s anyway, and analyses of the temporal dynamics of the CK reaction and the 31P MRS experiment predict that cyclic variations in kf would be too small to detect over physiological parameter ranges [40]. Moreover, CK flux does not change in healthy subjects when cardiac work-load is doubled [8]. If CK flux doesn’t increase with work-load, then a CK energy supply that is only 3.7-times that needed for peak cardiac SW at rest may be limiting at high work-loads in healthy subjects. Indeed, significant reductions of 14–21% in myocardial PCr/ATP have been reported at 3–4 times the resting HR × BP product in healthy subjects [41, 42], and even athletes [43].

Second, the present findings provide important support for the hypothesis that the CK reaction plays a vital role in delivering and buffering the ATP energy to fuel myofibrillar contraction in the human heart [9, 12–15], by arguably ruling out two alternative hypotheses. In order for changes in CK metabolism to have a relevant impact on cardiac energy supply in HF, CK flux should be neither much less than nor much more than cardiac utilization over a full-range of physiological conditions. If CK energy supply were much less than peak cardiac work, then it would be ineffectual as an energy buffer [8]. If on the other hand, the CK energy greatly exceeded cardiac work over the entire range of physiological activity, then the reductions in CK flux of 30–60% in human HF seen here and elsewhere [8, 17, 19] would not meaningfully impair energy supply. Instead, our measures of CK energy supply fall just within a range consistent with it representing a substantial source of cardiac energy, but small enough that a 30–60% shortfall could impair cardiac energetics, especially during times of stress or increased cardiac demand.

Third, cardiac CK flux was significantly lower at 2.1 μmol/gww/s or 126 ± 46 W/kg in HF patients compared to healthy subjects (p < 0.002) and correlated with the work rate normalized by LVM (p ≤ 0.009; Fig. 5). This 31% mean reduction in CK flux is consistent with, albeit smaller than, that reported in prior HF studies [8, 17, 19]. Curiously, both average and peak stroke work rates were lower in HF by the same amount (a third) as the CK energy supply (Table 2). Consequently the ratio of the CK energy supply to the peak stroke work expended in pumping blood at rest, is 126/32 = 3.9 in HF patients–essentially the same as in healthy subjects.

While LVM increased by 1.8-fold in HF (196 vs. 109 g, p < 0.002; Table 1), the failing heart in total, produced the same per-beat stroke work as in healthy hearts (SW =1.1 J; Table 2). Because Psys is comparable in HF and healthy subjects (Table 1), the total stroke work is essentially a measure of blood volume moved per beat (or the total change in blood volume, SV per beat). Thus the preservation of total SW (in Joule) is consistent with the preservation of SV in HF (83 vs. 92 ml, p = ns; Table 1) being an important early driver of cardiac remodeling [44]. Although the increase in LVM in HF is larger than the ~ 33% decline in contractile work and per-gram CK ATP energy supply, this extra mass and supply would substantially compensate for the lower mechanical efficiency of the remodeled heart (53% vs. 79% in controls, p < 0.001, with PE =6.5 W/kg in HF vs 2.9 W/kg in controls, p <0.001). Indeed in HF, the increase in the total work, PVA (=SW + PE, in Joules), is comparable to the total increase in LVM (a 2.14/1.3 = 1.6-fold increase in PVA vs. 1.8-fold for LVM; p = ns).

Fourth, the difference between CK flux and the peak mechanical power–the CK energy reserve–nevertheless seems to provide a large surplus of energy to support cardiac function at rest in both healthy subjects (131 W/Kg; Table 2) and in HF patients (94 W/Kg). However, the reduced mechanical efficiency in HF places an additional tax on the energy available for mechanical work, if the heart is to maintain a normal peak-to-average mechanical workload (pp/pav ~ 4.8) during stress. With a mean mechanical efficiency of 53% in HF, the CK flux should be able to support a doubling of peak mechanical power for the average HF patient studied here (2pp /53% =121 W/kg, vs. the 126 W/kg supplied via CK flux; Table 2). But patients with more severe reductions in CK flux (e.g. 1.1–1.6 μmol/ gww/s [8, 17]) or with lower efficiency (Fig. 5c), may experience more significant consequences such as worsening or activity-limiting symptoms.

Limitations

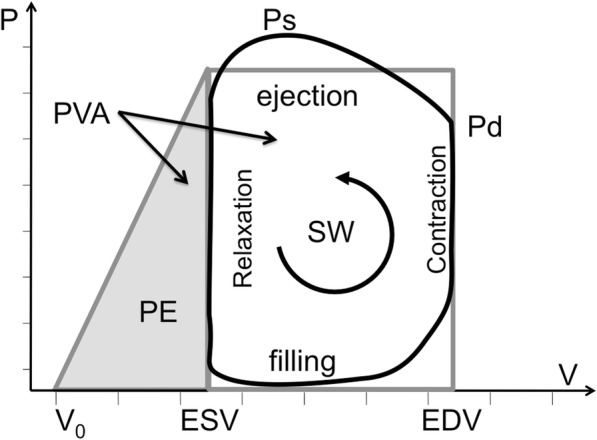

Until the past decade, measuring cardiac mechanical work required invasive catheter-based pressure and/or volume measurements. This limited studies to patients undergoing clinical cardiac catheterization [26, 32, 33, 45–49] that generally excluded truly healthy subjects [27] and confounded comparisons with less severely compromized patients. Nevertheless, our measures of SW =1.1 ± 0.3 J/beat are not inconsistent with values of SW =0.6–1.2 J/beat [27, 31, 50] in healthy subjects and SW =0.3–1.1 J/beat [45, 48, 51] in HF (Table 3) [52]. Moreover they agree with recent noninvasive SW measurements of 1.1 J in HF and 1.2 J in healthy subjects obtained using similar CMR volumetry and arterial BP methods [31, 50, 51] as here.

Table 3.

Comparison of noninvasive measurements of human cardiac mechanical work with prior studies employing catheterization techniques, ultrasound and cardiac MRI

Eff efficiency, HF congestive heart failure (prior studies, pink highlight), DCM dilated cardiomyopathy, MI prior myocardial infarction, CAD coronary artery disease, CM cardiomyopathy; HYPT hypertension, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, HCM hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, gen genetic origin, isch patients with ischemia. Prior studies of patients who did not have heart disease are highlighted in green. *P < 0.05 vs. controls. aConverted to SI units from mmHg.ml using a factor of 1.333 × 10–4. bUsed conductance and/or pressure catheter. cUsed cine CMR for volumetry. dUsed echocardiographic volumetry

While CMR is a gold standard for accurate measurements of myocardial volume, invasive intra-cardiac pressure monitoring throughout the cardiac cycle was impractical for our studies of subjects not undergoing catheterization. Consequently, obtaining the LV pressure from the brachial artery pressure is potentially confounding. A small systolic pressure difference between the brachial artery and the LV blood pool exists and is primarily related to central vascular stiffness. This can be indexed by the pulse-wave velocity, which in patients has been calibrated from catheter measurements to obtain the central aortic pressure [54]. Studies using this method to measure systolic aortic pressure in NYHA Class II-IV HF [53], hypertensives with coronary disease [54], and in another 10,613 subjects who were healthy, hypertensive or had heart disease [55], showed very similar aortic-peripheral artery pressure differences (healthy, 12 ± 6 mmHg, n = 5648; hypertensives, 12 ± 7 mmHg, n = 3420; cardiovascular disease, 12 ± 5 mmHg, n = 610) over a wide age range (18–101 years) [55]. As the aortic-brachial systolic pressure differential is the same or similar in patients and healthy subjects, it is unlikely to affect the significance of our findings other than by slightly decreasing the size of the CK energy reserve.

Computer simulations performed with stepped and half-sinusoid systolic pressure waveforms (see Additional file 1) suggest that pp could underestimate the true peak mechanical power by up to about 10%. This would again reduce the projected gap between CK energy supply and SW (the CK energy reserve), but should not affect the underlying conclusions. During diastole, simulations indicate that increasing end-diastolic pressure from 0 to 20 mmHg, alters pav by only − 5% to + 3%, for Psys ≥ 110 mmHg (per Table 1). Also as noted, the assumption of V0 = 0 has been used elsewhere [31]. It is supported by mean values of V0 = 0 ± 10, − 3 ± 11 ml, etc. measured using micromanometers and LV angiography during catheterization procedures performed on patients who had chest pain, some with hypertrophy [32, 33].

Patients in the present study had less severe HF and their reductions in cardiac CK rates and flux were less severe than those reported earlier [8, 17–19, 22]. Yet CK flux, which may be the most physiologically-relevant measure of CK metabolism for HF outcomes [18], was significantly reduced. There are presently no CK flux measurements available from HF patients during stress, but recent 31P MRS studies in hypertrophy [56] and diabetes [57] which are common precursors to HF, showed 8–12% decreases in cardiac PCr/ATP ratios during moderate exercise. Such reductions could further compromise CK energy supply during peak demand if they persisted in HF. Finally, the findings for this cohort of patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy may not be representative of all forms of HF. Reductions in cardiac CK kinetics are observed in nearly all experimental HF models from rodents to large animals and in common forms of human HF that arise from dilated, hypertrophic and ischemic cardiomyopathies. Whether the relationship between depressed cardiac CK energy supply and mechanical work seen here occurs in other forms of human HF remains to be seen.

Conclusion

Whether the CK energy supply is much higher or lower than cardiac energy utilization bears directly on the CK shuttle hypothesis and the significance of the role played by cardiac CK energetics in the failing human heart. We measured both cardiac CK energy supply and mechanical work in healthy subjects and patients with HF for the first time. Using noninvasive CMR/MRS techniques, we found that reduced CK flux in HF at rest was associated with the same or similar reductions in peak and average stroke work. Although CK flux exceeded peak stroke work by almost 4-fold at rest, the loss in CK energy reserve combined with a reduction in mechanical efficiency in HF patients could limit energy supply during moderate activity or stress and mechanistically contribute to clinical HF events [18].

Clinical implications

HF is a global pandemic affecting more than 20 million people worldwide. Despite advances in medical, device, and surgical therapies over the last three decades, the prognosis for patients with HF is still equivalent or worse than that of many cancers. New treatment strategies are needed. This work identifies inadequate energy supply as a potential contributor to the contractile dysfunction observed in patients with systolic HF which accounts for about half of the total HF population. The current findings are consistent with observations that medications which reduce energetic demand (eg, beta-blockers and/or angiotensin-renin blockade) significantly improve HF outcomes and survival. They also point to future ‘metabolic’ therapy strategies that could treat HF by restoring impaired energy supply, for example, by restoring mitochondrial function, augmenting the supply of alternate carbon substrates, or those that limit CK degradation [19] or genetically restore CK activity. Such energetic strategies may not necessarily replace, but could augment the efficacy of current HF treatment options.

Additional file

Supplementary material. (DOCX 79 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Tricia Steinberg for assisting human studies, and Sebastian Kelle and Glenn Hirsch for help with cardiac imaging and analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by AHA grant 13GRNT17050100 and NIH grant R01 HL61912.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, its Additional file and at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier, NCT00181259).

Abbreviations

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BMI

Body mass index

- BP

Blood pressure

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CMR

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- EDV

End-diastolic volume

- EF

Ejection fraction

- ESV

End-systolic volume

- HF

Heart failure

- LV

Left ventricle/left ventricular

- LVH

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- LVM

Left ventricular mass

- MRS

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- ns

Not significant

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- PCr

Phosphocreatine

- PE

Potential energy

- PV

Pressure-volume

- PVA

Total mechanical energy (or work)

- SI

Système International

- SW

Stroke work

Authors’ contributions

PAB conceived of combining CMR with MRS to noninvasively measure CK energy supply and stroke work in HF patients, and is responsible for the conduct of the study, the integrity of the data and findings. REG, AME, MS, RGW and PAB developed the CMR/MRS methods used for the work. REG, AME, MS and RGW performed the human CMR and MRS studies. RGW and PAB secured the funding. GSP, RGW and GG were responsible for subject recruitment and clinical evaluation. REG, PAB, AME and MS processed the MRS and CMR data. PAB and REG wrote the initial manuscript, and PAB and RGW revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Refaat E. Gabr, Email: refaat.e.gabr@uth.tmc.edu

AbdEl-Monem M. El-Sharkawy, Email: abdshark@gmail.com

Michael Schär, Phone: 443-287-7749, Email: michael.schar@gmail.com.

Gurusher S. Panjrath, Email: gpanjrath@mfa.gwu.edu

Gary Gerstenblith, Email: gblith@jhmi.edu.

Robert G. Weiss, Email: rweiss@jhmi.edu

Paul A. Bottomley, Email: bottoml@mri.jhu.edu

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA. Heart failure. Lancet. 2005;365:1877–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann G. The chemical nature of heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1939;12:1233–1244. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-12-8-1233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson RE. Myocardial metabolism in congestive heart failure. J Chronic Dis Elsevier. 1959;9:442–464. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(59)90172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huss JM, Kelly DP. Mitochondrial energy metabolism in heart failure: a question of balance. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:547–555. doi: 10.1172/JCI24405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingwall JS. Is cardiac-failure a consequence of decreased energy reserve. Circulation. 1993;87:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz AM. Is the failing heart energy depleted? Cardiol Clin. 1998;16:633–644. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8651(05)70040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss RG, Gerstenblith G, Bottomley PA. ATP flux through creatine kinase in the normal, stressed, and failing human heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:808–813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408962102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neubauer SS. The failing heart--an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1140–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss RG, Bottomley PA, Hardy CJ, Gerstenblith G. Regional myocardial metabolism of high-energy phosphates during isometric exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1593–1600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yabe T, Mitsunami K, Okada M, Morikawa S, Inubushi T, Kinoshita M. Detection of myocardial ischemia by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy during handgrip exercise. Circulation. 1994;89:1709–1716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.89.4.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bessman SP, Carpenter CL. The creatine-creatine phosphate energy shuttle. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:831–862. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.004151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dzeja PP, Terzic A. Phosphotransfer networks and cellular energetics. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:2039–2047. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingwall JS, Weiss RG. Is the failing heart energy starved? On using chemical energy to support cardiac function. Circ Res. 2004;95:135–145. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137170.41939.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallimann T. Bioenergetics: dissecting the role of creatine kinase. Curr Biol. 1994;4:42–46. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottomley PA. Noninvasive study of high-energy phosphate metabolism in human heart by depth-resolved 31P NMR spectroscopy. Science. 1985;229:769–772. doi: 10.1126/science.4023711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith CS, Bottomley PA, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG. Altered creatine kinase adenosine triphosphate kinetics in failing hypertrophied human myocardium. Circulation. 2006;114:1151–1158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottomley PA, Panjrath GS, Lai S, Hirsch GA, Wu K, Najjar SS, et al. Metabolic rates of ATP transfer through Creatine kinase (CK flux) predict clinical heart failure events and death. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:215re3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch GA, Bottomley PA, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG. Allopurinol acutely increases adenosine Triphospate energy delivery in failing human hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:802–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.El-Sharkawy A-MM, Gabr RE, Schär M, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Quantification of human high-energy phosphate metabolite concentrations at 3 T with partial volume and sensitivity corrections. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1363–1371. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schär M, El-Sharkawy A-MM, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Triple repetition time saturation transfer (TRiST) 31P spectroscopy for measuring human creatine kinase reaction kinetics. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1493–1501. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bottomley PA, Wu KC, Gerstenblith G, Schulman SP, Steinberg A, Weiss RG. Reduced myocardial creatine kinase flux in human myocardial infarction: an in vivo phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation. 2009;119:1918–1924. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabr RE, Ouwerkerk R, Bottomley PA. Quantifying in vivo MR spectra with circles. J Magn Reson. 2006;179:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabr RE, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Correcting reaction rates measured by saturation-transfer magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 2008;191:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schär M, Gabr RE, El-Sharkawy A-MM, Steinberg A, Bottomley PA, Weiss RG. Two repetition time saturation transfer (TwiST) with spill-over correction to measure creatine kinase reaction rates in human hearts. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson Springer. 2015;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takaoka H, Takeuchi M, Odake M, Yokoyama M. Assessment of myocardial oxygen consumption (Vo2) and systolic pressure-volume area (PVA) in human hearts. Eur Heart J. 1992;13(Suppl E):85–90. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/13.suppl_E.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alter P, Rupp H, Rominger MB, Klose KJ, Maisch B. A new methodological approach to assess cardiac work by pressure-volume and stress-length relations in patients with aortic valve stenosis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2008;455:627–636. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westerhof N, Stergiopulos N, Noble MIMM. Snapshots of hemodynamics: an aid for clinical research and graduate education. Springer US.2010.

- 29.Ganz W, Tamura K, Marcus HS, Donoso R, Yoshida S, Swan HJC. Measurement of coronary sinus blood flow by continuous thermodilution in man. Circulation. 1971;44:181–195. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.44.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suga H. Ventricular energetics. Physiol Rev Am Phys Soc. 1990;70:247–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmer SAJ, Germans T, Götte MJW, Rüssel IK, Dijkmans PA, Lubberink M, et al. Determinants of myocardial energetics and efficiency in symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:779–788. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nitenberg A, Antony I, Loiseau A. Left ventricular contractile performance, ventriculoarterial coupling, and left ventricular efficiency in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:1188–1198. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitenberg A, Loiseau A, Antony I. Left ventricular mechanical efficiency in hypertensive patients with and without increased myocardial mass and with normal pump function. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitt B, Steendijk P, Lunze K, Ovroutski S, Falkenberg J, Rahmanzadeh P, et al. Integrated assessment of diastolic and systolic ventricular function using diagnostic cardiac magnetic resonance catheterization: validation in pigs and application in a clinical pilot study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:1271–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun KT, Yeatman LA, Buxton DB, Chen K, Johnson JA, Huang SC, et al. Simultaneous measurement of myocardial oxygen consumption and blood flow using [1-carbon-11]acetate. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:272–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knaapen P, Germans T, Knuuti J, Lammertsma AA, Visser FC, Paulus WJ, et al. Myocardial energetics and efficiency current status of the noninvasive approach. Circulation. Am Heart Assoc. 2007;115:918–927. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashir A, Gropler R. Reproducibility of creatine kinase reaction kinetics in human heart: a 31P time-dependent saturation transfer spectroscopy study. NMR Biomed. 2014;27:663–671. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke WT, Robson MD, Neubauer S, Rodgers CT. Creatine kinase rate constant in the human heart measured with 3D-localization at 7 tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:20–32. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bottomley PA. MRS studies of creatine kinase metabolism in human heart. eMagRes. 2016;5:1183–1202. doi: 10.1002/9780470034590.emrstm1488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss K, Bottomley PA, Weiss RG. On the theoretical limits of detecting cyclic changes in cardiac high-energy phosphates and creatine kinase reaction kinetics using in vivo 31P MRS. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:694–705. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamb HJ, Beyerbacht HP, Ouwerkerk R, Doornbos J, Pluim BM, van der Wall EE, et al. Metabolic response of normal human myocardium to high-dose atropine-dobutamine stress studied by P-31-MRS. Circulation. 1997;96:2969–2977. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.9.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamb HJ, Beyerbacht HP, van der Laarse A, Stoel BC, Doornbos J, van der Wall EE, et al. Diastolic dysfunction in hypertensive heart disease is associated with altered myocardial metabolism. Circulation. 1999;99:2261–2267. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.17.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pluim BM, Lamb HJ, Kayser HWM, Leujes F, Beyerbacht HP, Zwinderman AH, et al. Functional and metabolic evaluation of the athlete’s heart by magnetic resonance imaging and dobutamine stress magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Circulation. 1998;97:666–672. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling—concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–582. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eichhorn EJ, Bedotto JB, Malloy CR, Hatfield BA, Deitchman D, Brown M, et al. Effect of beta-adrenergic blockade on myocardial function and energetics in congestive heart failure. Improvements in hemodynamic, contractile, and diastolic performance with bucindolol. Circulation. 1990;82:473–483. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.82.2.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kameyama T, Asanoi H, Ishizaka S, Yamanishi K, Fujita M, Sasayama S. Energy conversion efficiency in human left ventricle. Circulation. 1992;85:988–996. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.3.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asanoi H, Kameyama T, Ishizaka S, Nozawa T, Inoue H. Energetically optimal left ventricular pressure for the failing human heart. Circulation. 1996;93:67–73. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim IS, Izawa H, Sobue T, Ishihara H, Somura F, Nishizawa T, et al. Prognostic value of mechanical efficiency in ambulatory patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in sinus rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1264–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steendijk P, Tulner SA, Bax JJ, Oemrawsingh PV, Bleeker GB, Van Erven L, et al. Hemodynamic effects of long-term cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis by pressure-volume loops. Circulation. 2006;113:1295–1304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Timmer SAJ, Germans T, Brouwer WP, Lubberink M, van der Velden J, Wilde AAM, et al. Carriers of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy MYBPC3 mutation are characterized by reduced myocardial efficiency in the absence of hypertrophy and microvascular dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1283–1289. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Timmer SAJ, Knaapen P, Germans T, Dijkmans PA, Lubberink M, ten Berg JM, et al. Effects of alcohol septal ablation on coronary microvascular function and myocardial energetics in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H129–H137. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00077.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhuiyan T, Helmke S, Patel AR, Ruberg FL, Packman J, Cheung K, et al. Pressure-volume relationships in patients with transthyretin (ATTR) cardiac amyloidosis secondary to V122i mutations and wild-type transthyretin: transthyretin cardiac amyloid study (TRACS). Circ Hear Fail. 2011;4:121–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Carroll JD, Shroff S, Wirth P, Halsted M, Rajfer SI. Arterial mechanical properties in dilated cardiomyopathy. Aging and the response to nitroprusside. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1002–1009. doi: 10.1172/JCI115058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pauca AL, O’Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38:932–937. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.CM ME, Yasmin MDB, Munnery M, Wallace SM, Rowe CV, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB, on behalf of the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial Investigators Central pressure: variability and impact of cardiovascular risk factors. The Anglo-Cardiff collaborative trial II. Hypertension. 2008;51:1476–1482. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dass S, Cochlin LE, Suttie JJ, Holloway CJ, Rider OJ, Carden L, et al. Exacerbation of cardiac energetic impairment during exercise in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a potential mechanism for diastolic dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1547–1554. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levelt E, Rodgers CT, Clarke WT, Mahmod M, Ariga R, Francis JM, et al. Cardiac energetics, oxygenation, and perfusion during increased workload in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3461–3469. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material. (DOCX 79 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, its Additional file and at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier, NCT00181259).