Abstract

Background

Despite the considerable experience gained thus far using endoscopic technologies, the role of total endoscopic thyroidectomy (ET) for papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) remains controversial. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the safety and effectiveness of total ET compared with conventional open thyroidectomy (OT) in PTC.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted using the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library electronic databases up to March 2018. The quality of included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. Review Manager software version 5.3 was used for the meta-analysis.

Results

Twelve studies including 2,672 patients were ultimately included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. ET was associated with longer operative time (P<0.00001), drainage time (P<0.00001) and hospital stay (P=0.03), higher transient recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy rate (P=0.004) and a greater amount of drainage fluid (P<0.0001) compared with OT. Furthermore, no significant differences were detected between ET and OT in terms of retrieved lymph nodes (P=0.17), blood loss (P=0.22), transient hypocalcemia (P=0.84), permanent hypocalcemia (P=0.58), permanent RLN palsy (P=0.14), hematoma or bleeding (P=0.15) and seroma (P=0.54). In addition, the rates of tumor recurrence were comparable (P=0.18), whereas the proportions of stimulated thyroglobulin levels <1 ng/mL measured after completion of thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine therapy were less (P=0.02) in the ET than in the OT group.

Conclusion

ET is not superior to OT in terms of operation and drainage time, amount of drainage fluid, hospital stay or transient RLN palsy, but is comparable to OT in terms of retrieved lymph nodes and permanent complications. Despite the similar tumor recurrence rates between the two approaches, the level of surgical completeness in ET may not be as good as that for OT.

Keywords: endoscopic thyroidectomy, conventional open thyroidectomy, papillary thyroid carcinoma, meta-analysis

Background

Thyroid cancer is considered the most prevalent endocrine cancer, especially in women.1,2 Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), the major histological subtype, constitutes approximately 85% of all thyroid malignancies.3 Although conventional open thyroidectomy (OT) is a standard surgery with low morbidity and minimal mortality for PTC,4 it requires a cervical incision in the neck. Nevertheless, the cosmetic outcome may be a particular concern, especially in young women.

The popularity of endoscopic technologies has allowed surgeons to complete resection and simultaneously deliver cosmetic results. In 1997, Hüscher et al first performed endoscopic thyroidectomy (ET).5 Since then, various ET approaches have evolved, such as breast,6 axillary,7 axillobreast,8 submental9 and oral cavity approaches.10 However, endoscopic techniques present some difficulties in obtaining adequate surgical views because of the small working space and two-dimensional operative views.11 In addition, surgical indications for ET remain ambiguous, and the benefits of ET are considered marginal for PTC.12,13 Some studies have even questioned the safety of ET for PTC and proposed that this method should be critically evaluated.14,15 Thus, it remains unsettled whether ET is effective and safe compared with OT.

To our knowledge, only one meta-analysis comparing outcomes between ET and OT has been published.16 However, the previous meta-analysis was conducted on five studies and focused on patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC). Given the growing number of publications on this debatable subject and the extended indications for ET,7 it is necessary to perform a systematic meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness and safety of ET with OT in PTC patients.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement.17

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted using the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library electronic databases on 15 March 2018. We used the following keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: “laparoscopy” or “endoscopy” or “minimally invasive surgery” or “video-assisted surgery” and “thyroidectomy” and “thyroid cancer”. We also reviewed the reference lists from the retrieved articles.

Study selection

Two independent authors (CC and SMH) reviewed study titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant articles, and studies meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for full-text assessment. Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) English language; 2) comparative studies between ET and OT for patients with PTC; 3) studies comparing at least one outcome of surgery; and 4) multiple studies from the same institution were assessed and the highest quality and most up-to-date of these was retained. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) studies that were reviews, case reports, letters, conferences, editorials, or expert opinions; 2) studies that focused on patients with thyroid cancer other than PTC; and 3) studies reporting on the pediatric population.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted into prepared standardized forms by two independent reviewers.

The primary data extracted from each study included the first author, year of publication, geographical region, study type, number of patients, patient demographics, pathological characteristics of PTC, operative details (extent of thyroidectomy, surgical approach), intraoperative outcomes, postoperative outcomes and oncological outcomes (stimulated thyroglobulin [sTg], tumor recurrences). Intraopera-tive outcomes included operative time, blood loss and the number of retrieved lymph nodes. Postoperative outcomes included hospitalization period after the operation, volume and duration of drainage, postoperative complications (transient hypocalcemia, permanent hypocalcemia, transient recurrent laryngeal nerve [RLN] palsy, permanent RLN palsy, hematoma or bleeding, and seroma). Total thyroidectomy (TT) included near-TT and TT, whereas less than total thyroidectomy (LTT) included hemithyroidectomy and subtotal thyroidectomy. The sTg level was measured after total completion of thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine therapy and defined as <1.0 ng/mL as an indicator of surgical completeness. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus.

The quality assessment of nonrandomized studies was also performed by two independent reviewers using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, with some modifications to match the requirements of this study.18,19 The quality was assessed based on three aspects: patient selection, comparability of groups and outcome assessment. Only studies awarded six or more stars were considered as high-quality studies.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager software version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, 2014) was used for data analysis. For continuous outcomes, the weighted mean differences (WMDs) with corresponding 95% CIs were calculated. For dichotomous outcomes, the ORs with corresponding 95% CIs were examined. The results were analyzed using fixed- or random-effects models, depending on the heterogeneity involved. The statistical heterogeneity was accessed by the Cochran Q test and evaluated the extent of inconsistency by the I2 statistic, which was divided into three degrees including low (25%–49%), moderate (50%–74%) and high (≥75%) levels.20 When P>0.1 and I2<50%, a fixed-effects model was used; otherwise, a random-effects model was applied. We used the following methods to explore sources of heterogeneity: 1) subgroup analysis (TT and LTT) and 2) sensitivity analysis conducted by excluding each of the included studies to identify which studies influenced the degree of heterogeneity. The possible presence of publication bias was estimated by Egger’s test and Begg’s test, investigated using STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection

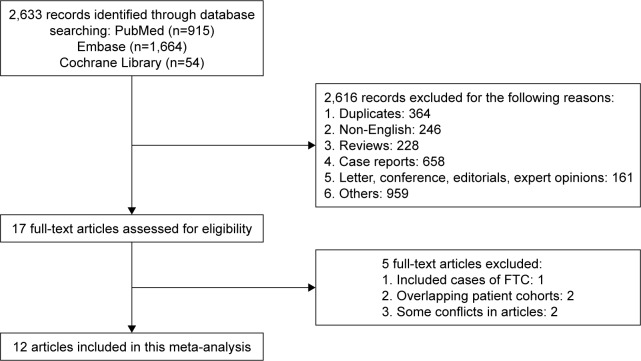

The initial search yielded 2,633 potentially relevant articles. Seventeen potential articles were identified after screening titles and abstracts. After full-text review, an additional five articles were excluded for the following reasons: including cases of follicular thyroid cancer (n=1),21 cohorts may have overlapped (n=2)22,23 and some conflicts in articles (n=2).24,25 Finally, 12 observational articles were obtained for final analysis (Figure 1).7,26–36

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

Abbreviation: FTC, follicular thyroid cancer.

Study and patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the total number of 2,672 PTC patients included, of whom 799 underwent ET and 1,873 underwent OT. Eight studies26–30,32–34 were performed in the Republic of Korea and four studies7,31,35,36 in China. All 12 studies were retrospective. In terms of surgical approach, in six studies the axillobreast approach (ABA) was performed,26–28,32–34 in three studies the bilateral breast approach (BBA) was performed,31,35,36 in two studies the transaxillary approach (TAA) was performed,7,30 and in the remaining study either ABA or TAA was performed for thyroidectomy.29 The pathological details of each study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study (first author, year) | Region | Study type | No of patients

|

Age (years), mean ± SD ET OT

|

Gender, M/F

|

Extent of thyroidectomy, TT/LTT

|

Surgical approach | Matchinga | Quality score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | OT | ET | OT | ET | OT | ET | OT | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Chung 200726 | Korea | RS | 103 | 198 | 38.2±8.2 | 47.2±10.2 | 1/102 | 25/173 | 88/15 | 172/26 | BABA | 4, 9 | 6 |

| Hong 201127 | Korea | RS | 57 | 60 | 39.60±7.88 | 41.77±9.61 | 6/51 | 11/49 | 0/57 | 0/60 | BABA/UABA | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9 | 7 |

| Kim 201128 | Korea | RS | 95 | 138 | 39.9±9.1 | 51.8±8.9 | 2/93 | 34/104 | 95/0 | 138/0 | BABA | 9 | 6 |

| Tae 201129 | Korea | RS | 31 | 36 | 36.2±9.9 | 44.6±11.8 | 1/30 | 11/25 | 3/28 | 0/36 | UABA/TAA | 4–9 | 7 |

| Lee 201230 | Korea | RS | 37 | 41 | 42.3±7.6 | 49.0±10.8 | 0/37 | 3/38 | 0/37 | 0/41 | TAA | 2, 4, 5, 7–9 | 7 |

| Tan 201531 | China | RS | 34 | 30 | 30 (16–44)b | 43 (25–76)b | 2/32 | 4/26 | 0/34 | 0/30 | BBA | 2, 4, 9 | 7 |

| Huang 20167 | China | RS | 75 | 123 | 37.8±10.6 | 39.2±11.3 | 16/59 | 31/92 | 75/0 | 123/0 | TAA | 1–5, 7–9 | 7 |

| Kim 201632 | Korea | RS | 173 | 830 | 38.90 (17–57)b | 49.53 (17–84)b | 13/160 | 96/734 | 56/117 | 684/146 | BABA | 2 | 5 |

| Lee 201633 | Korea | RS | 75 | 233 | 42.2±8.6 | 52.1±9.3 | 3/72 | 15/218 | 0/75 | 0/233 | BABA/UABA | 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 | 6 |

| Park 201634 | Korea | RS | 50 | 102 | 38.0±9.4 | 50.8±11.5 | 4/46 | 14/88 | 50/0 | 102/0 | UABA | 2, 4–7, 9 | 5 |

| Xiang 201635 | China | RS | 49 | 47 | 34.2±7.0 | 46.9±13.3 | 0/49 | 6/41 | 49/0 | 47/0 | BBA | 7, 9 | 6 |

| Ren 201736 | China | RS | 20 | 35 | 36.05±7.536 | 36.06±5.646 | 0/20 | 0/35 | 0/20 | 0/35 | BBA | 1–3, 9 | 6 |

Notes:

Features matching ET and OT: 1 = age; 2 = gender; 3 = body mass index; 4 = tumor size; 5 = multiplicity; 6 = bilaterality; 7 = extrathyroidal extension; 8 = tumor stage; 9 = extent of thyroidectomy.

Median (range).

Abbreviations: BABA, bilateral axillobreast approach; BBA, bilateral breast approach; ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; F, female; LTT, less than total thyroidectomy; M, male; OT, open thyroidectomy; RS, retrospective study; TAA, transaxillary approach; TT, total thyroidectomy; UABA, unilateral axillobreast approach.

Table 2.

Pathological characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study (first author, year) | Tumor size (mm)

|

Multiplicity (n/N)

|

Bilaterality (n/N)

|

Extrathyroidal extension (n/N)

|

Positive LNs (n/N)

|

No of metastatic LNs

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | OT | ET | OT | ET | OT | ET | OT | ET | OT | ET | OT | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Chung 200726 | <10 | <10 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hong 201127 | 7.25±2.30 | 7.10±2.65 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 10/57 | 19/60 | 21/57 | 26/60 | 1.30±1.83 | 1.43±1.87 |

| Kim 201128 | 6.0±2.0 | 7.0±2.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.9±2.0 | 0.5±0.9 |

| Tae 201129 | 7.6±4.9 | 6.4±2.3 | 2/31 | 2/36 | 0/31 | 0/36 | 2/31 | 1/36 | 4/16 | 2/12 | NR | NR |

| Lee 201230 | 5.0±2.31 | 4.1±2.64 | 3/37 | 5/41 | NR | NR | 1/37 | 2/41 | 5/37 | 1/41 | NR | NR |

| Tan 201531 | 7.0±3.0 | 8.0±4.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 8/34 | 4/30 | 0.8±2.0 | 0.2±0.7 |

| Huang 20167 | 4.8±1.9 | 4.9±2.3 | 5/75 | 9/123 | NR | NR | 2/75 | 4/123 | 9/75 | 11/123 | NR | NR |

| Kim 201632 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4/173 | 128/830 | 34/173 | 312/830 | NR | NR |

| Lee 201633 | 5.8±3.5 | 6.2±3.7 | 12/75 | 30/233 | NR | NR | 21/75 | 93/233 | 12/75 | 35/233 | NR | NR |

| Park 201634 | 8.0±3.7 | 7.6±1.9 | 7/50 | 19/102 | 10/50 | 18/102 | 28/50 | 70/102 | NR | NR | 0.7±1.4 | 0.6±1.2 |

| Xiang 201635 | 7.7±4.2 | 12.4±7.9 | 26/49 | 37/47 | NR | NR | 3/49 | 8/47 | 20/49 | 40/47 | NR | NR |

| Ren 201736 | <10 | <10 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Overall | 6.4±3.2 | 6.7±3.7 | 55/317 | 102/582 | 10/81 | 18/138 | 71/547 | 325/1,472 | 113/516 | 431/1,376 | 0.9±1.8 | 0.7±1.3 |

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; LN, lymph node; NR, not reported; OT, open thyroidectomy.

Meta-analysis of intraoperative outcomes

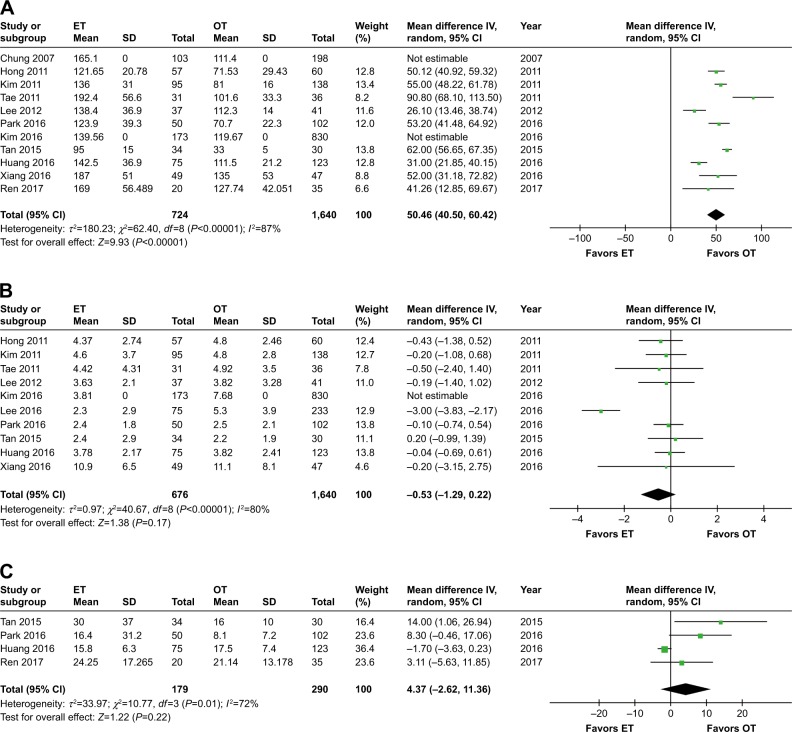

Eleven studies calculated operative times for ET vs OT,7,26–32,34–36 and the operation time in the ET group was significantly longer than that in the OT group (WMD 50.46, 95% CI 40.50 to 60.42, P<0.00001). However, there was a high level of heterogeneity among the studies (I2=87%, P<0.00001). The meta-analysis results remained unaffected when each individual study was removed from the data set.

Ten studies presented the number of retrieved lymph nodes,7,27–35 and the pooled data showed no significant differences between groups (WMD −0.53, 95% CI −1.29 to 0.22, P=0.17). Furthermore, there was a high level of heterogeneity among the studies (I2=80%, P<0.00001). After excluding the study by Lee et al,33 there were still no significant differences between groups (WMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.47 to 0.20, P=0.42), but no heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2=0%).

Four studies7,31,34,36 compared intraoperative blood loss and the pooled data showed no significant differences between groups (WMD 4.37, 95% CI −2.62 to 11.36, P=0.22). In addition, there was a moderate level of heterogeneity among the studies (I2=72%, P=0.01). After removing the study by Huang et al,7 the results became significant (WMD 7.24, 95% CI 1.66 to 12.82, P=0.01) and the heterogeneity among the studies no longer existed (I2=0%) (Table 3 and Figure 2A–C).

Table 3.

Outcomes of meta-analysis comparing ET vs OT

| Outcomes | No of studies | No of patients

|

OR/WMD | 95% CI | P-value | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | OT | ||||||

| Intraoperative outcomes | |||||||

| Operative time | 11 | 724 | 1,640 | 50.46 | 40.50, 60.42 | <0.00001 | 87 |

| No of retrieved LNs | 10 | 676 | 1,640 | −0.53 | −1.29, 0.22 | 0.17 | 80 |

| Blood loss | 4 | 179 | 290 | 4.37 | −2.62, 11.36 | 0.22 | 72 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||||||

| Duration of drainage | 3 | 104 | 167 | 1.88 | 1.22, 2.54 | <0.00001 | 76 |

| Volume of drainage | 5 | 230 | 341 | 111.96 | 61.66, 162.26 | <0.0001 | 95 |

| Hospitalization period | 8 | 566 | 1,440 | 0.65 | 0.06, 1.24 | 0.03 | 90 |

| Transient RLN palsy | 11 | 762 | 1,832 | 2.64 | 1.36, 5.11 | 0.004 | 48 |

| Permanent RLN palsy | 9 | 653 | 1,679 | 2.04 | 0.80, 5.23 | 0.14 | 0 |

| Transient hypocalcemia | 8 | 555 | 1,416 | 0.93 | 0.46, 1.87 | 0.84 | 81 |

| Permanent hypocalcemia | 7 | 521 | 1,386 | 0.82 | 0.39, 1.69 | 0.58 | 0 |

| Hematoma or bleeding | 10 | 674 | 1,538 | 1.76 | 0.81, 3.81 | 0.15 | 0 |

| Seroma | 4 | 258 | 357 | 1.33 | 0.53, 3.34 | 0.54 | 0 |

| Oncological outcomes | |||||||

| sTg <1.0 ng/mL | 2 | 29 | 343 | 0.33 | 0.13, 0.81 | 0.02 | 0 |

| Tumor recurrences | 6 | 398 | 1,170 | 0.54 | 0.22, 1.32 | 0.18 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; LN, lymph node; OT, open thyroidectomy; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; sTg, stimulated thyroglobulin; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Figure 2.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of (A) operative time; (B) number of retrieved lymph nodes; (C) blood loss.

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; OT, open thyroidectomy.

Meta-analysis of postoperative outcomes

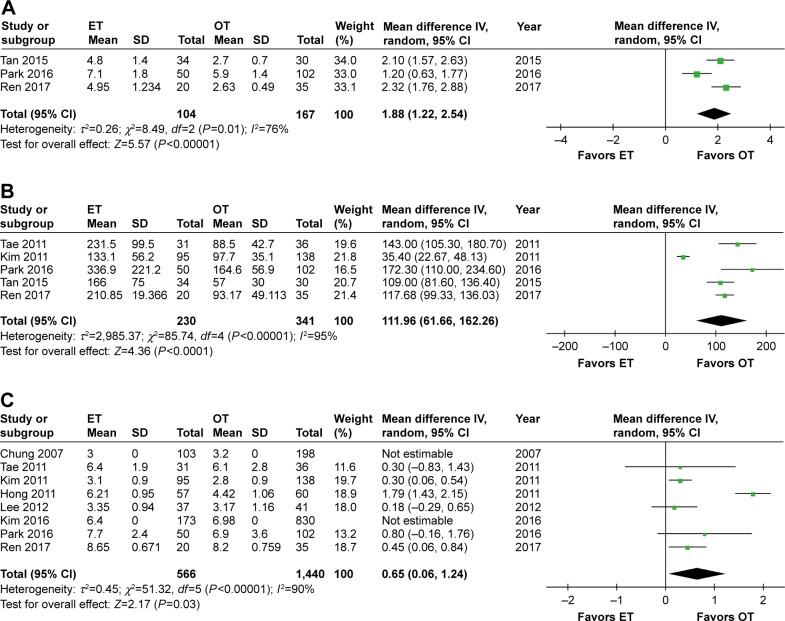

Three studies31,34,36 reported the duration of drainage and suggested a longer drainage period in ET than in OT (WMD 1.88, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.54, P<0.00001). Furthermore, this result showed a high level of heterogeneity as well (I2=76%, P=0.01). After removing the study by Park et al,34 the significance of the result was unchanged (WMD 2.20, 95% CI 1.82 to 2.59, P<0.00001), but no heterogeneity existed across the studies (I2=0%).

Five studies28,29,31,34,36 assessed the volume of drainage and described a larger amount of drainage in the ET group (WMD 111.96, 95% CI 61.66 to 162.26, P<0.0001). In addition, there was a high level of heterogeneity among the studies (I2=95%, P<0.00001). After removing the study by Kim et al,28 the previously high heterogeneity dramatically declined (I2=37%, P=0.19), but the significance of the result was unaffected (WMD 121.54, 95% CI 107.76 to 135.33, P<0.00001).

Eight studies described a hospitalization period after the operation.26–30,32,34,36 The combined results of these studies showed that ET had a longer hospitalization period than OT (WMD 0.65, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.24, P=0.03), and this result was associated with significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2=90%, P<0.00001). After removing the study by Hong et al,27 no heterogeneity existed (I2=0%), but the significance of the result was unchanged (WMD 0.33, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.51, P=0.0003) (Table 3 and Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of (A) duration of drainage; (B) volume of drainage; (C) hospitalization period.

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; OT, open thyroidectomy.

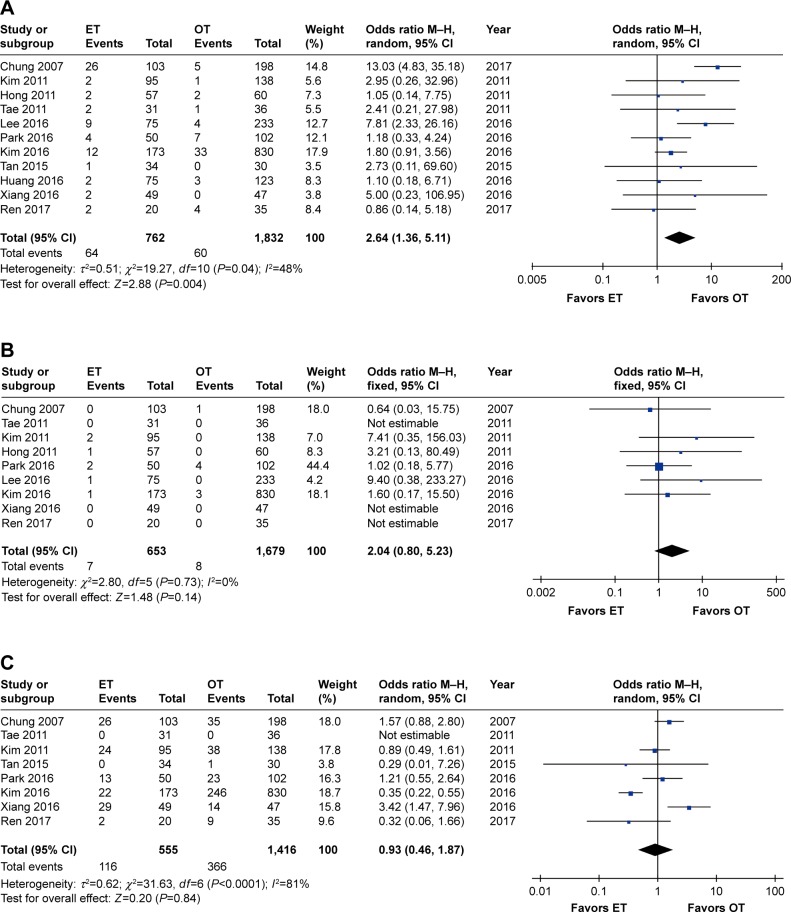

Meta-analysis of postoperative complications

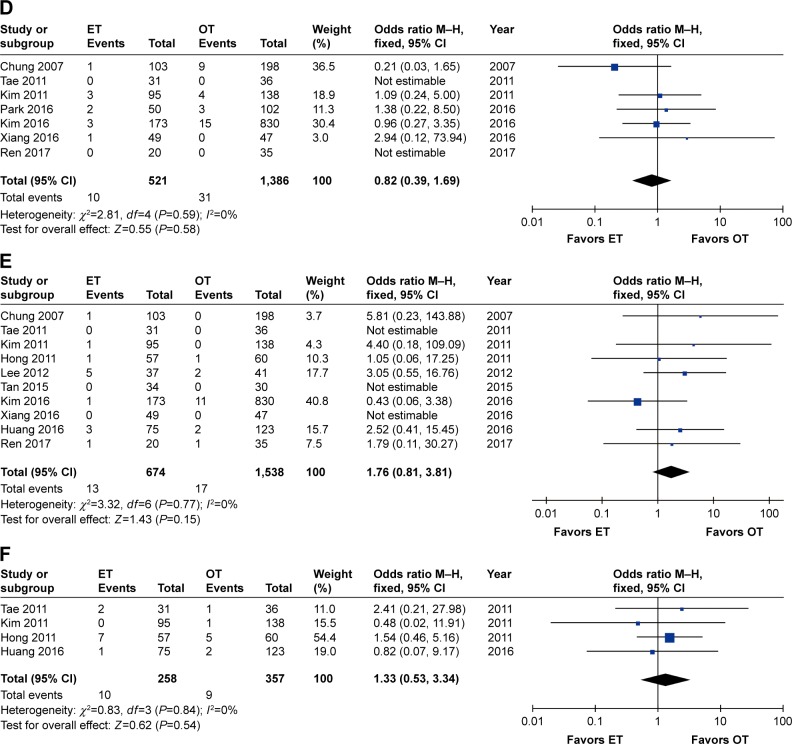

Eleven studies reported the transient postoperative RLN palsy rate,7,26–29,31–36 whereas nine reported permanent postoperative RLN palsy rates.26–29,32–36 The cumulative transient RLN palsy rate was significantly higher in ET (OR 2.64, 95% CI 1.36 to 5.11, P=0.004), and low heterogeneity (I2=48%, P=0.04) was observed among the studies. The significance of the result was unchanged when removing the study by Chung et al26 (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.13, P=0.002), but the heterogeneity among studies no longer existed (I2=0%). In terms of permanent RLN palsy, no significant differences were observed between the two groups (OR 2.04, 95% CI 0.80 to 5.23, P=0.14), and no heterogeneity existed (I2=0%).

Eight studies reported the transient postoperative hypocalcemia rate,26,28,29,31,32,34–36 whereas seven reported permanent postoperative hypocalcemia rates.26,28,29,32,34–36 No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of transient hypocalcemia (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.87, P=0.84), but high heterogeneity existed (I2=81%, P<0.0001). The meta-analysis results remained unchanged (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.16, P=0.40) but a moderate decline in the heterogeneity (I2=53%, P=0.06) was observed when the study by Kim et al was removed.32 In the case of permanent postoperative hypocalcemia, neither significant differences (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.69, P=0.58) nor heterogeneity (I2=0%) were detected.

Regarding other complications, such as postoperative hematoma or bleeding (OR 1.76, 95% CI 0.81 to 3.81, P=0.15) and postoperative seroma (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.53 to 3.34, P=0.54), no heterogeneity existed across studies (I2=0%), and no significant differences between the ET and OT groups were observed (Table 3 and Figure 4A–F).

Figure 4.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of (A) transient RLN palsy; (B) permanent RLN palsy; (C) transient hypocalcemia; (D) permanent hypocalcemia; (E) hematoma or bleeding; (F) seroma.

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; OT, open thyroidectomy; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve.

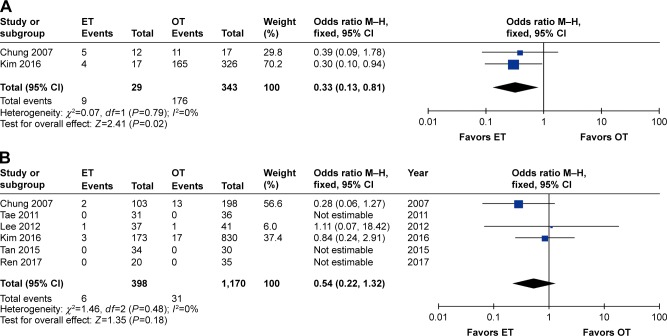

Meta-analysis of oncological results

The sTg levels were available in two studies.26,32 The ET group had lower proportions of having sTg <1.0 ng/mL (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.81, P=0.02). No heterogeneity among studies existed (I2=0%).

Six studies recorded tumor recurrences,26,29–32,36 and three studies reported no tumor recurrences during the follow-up period. Analysis of the pooled data showed that the two groups did not differ significantly (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.32, P=0.18). No heterogeneity among studies was observed (I2=0%) (Table 3 and Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of (A) number of sTg <1 ng/mL; (B) number of tumor recurrences.

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; OT, open thyroidectomy; sTg, stimulated thyroglobulin.

Subgroup analysis

We conducted a subgroup analysis according to the extent of thyroidectomy. The results of the subgroup analysis were roughly consistent with the previous outcomes. However, the volume of drainage (WMD 100.31, 95% CI −33.67 to 234.29, P=0.14) and transient RLN palsy (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.66 to 3.79, P=0.31) were comparable between the ET and OT groups in TT. In addition, the hospitalization period was comparable between the two groups in LTT (OR 0.81, 95% CI −0.19 to 1.82, P=0.11). The concrete results of the subgroup analysis are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of the subgroups according to the extent of thyroidectomy

| Outcomes | No of studies | No of patients

|

OR/WMD | 95% CI | P-value | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | OT | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| TT | |||||||

| Operative time | 4 | 269 | 410 | 47.40 | 34.18, 60.61 | <0.00001 | 84 |

| No of retrieved LNs | 4 | 269 | 410 | −0.10 | −0.50, 0.30 | 0.63 | 0 |

| Blood loss | 2 | 125 | 225 | 2.35 | −7.27, 11.97 | 0.63 | 79 |

| Volume of drainage | 2 | 145 | 240 | 100.31 | −33.67, 234.29 | 0.14 | 94 |

| Hospitalization period | 2 | 145 | 240 | 0.33 | 0.10, 0.56 | 0.005 | 0 |

| Transient RLN palsy | 4 | 269 | 410 | 1.58 | 0.66, 3.79 | 0.31 | 0 |

| Permanent RLN palsy | 3 | 194 | 287 | 1.89 | 0.49, 7.33 | 0.36 | 20 |

| Transient hypocalcemia | 3 | 194 | 287 | 1.48 | 0.68, 3.20 | 0.32 | 70 |

| Permanent hypocalcemia | 3 | 194 | 287 | 1.35 | 0.46, 3.99 | 0.58 | 0 |

| Hematoma or bleeding | 3 | 219 | 308 | 2.93 | 0.61, 14.02 | 0.18 | 0 |

| Seroma | 2 | 170 | 261 | 0.67 | 0.10, 4.55 | 0.68 | 0 |

| LTT | |||||||

| Operative time | 4 | 148 | 166 | 45.96 | 29.33, 62.59 | <0.00001 | 90 |

| No of retrieved LNs | 4 | 203 | 364 | −0.89 | −2.48, 0.70 | 0.27 | 90 |

| Blood loss | 2 | 54 | 65 | 6.52 | −0.72, 13.76 | 0.08 | 46 |

| Duration of drainage | 2 | 54 | 65 | 2.20 | 1.82, 2.59 | <0.00001 | 0 |

| Volume of drainage | 2 | 54 | 65 | 114.99 | 99.74, 130.24 | <0.00001 | 0 |

| Hospitalization period | 3 | 114 | 136 | 0.81 | −0.19, 1.82 | 0.11 | 95 |

| Transient RLN palsy | 4 | 186 | 358 | 2.83 | 1.26, 6.36 | 0.01 | 44 |

| Permanent RLN palsy | 3 | 152 | 328 | 5.29 | 0.54, 52.22 | 0.15 | 0 |

| Transient hypocalcemia | 2 | 54 | 65 | 0.31 | 0.07, 1.36 | 0.12 | 0 |

| Hematoma or bleeding | 4 | 148 | 166 | 2.20 | 0.62, 7.84 | 0.22 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; LN, lymph node; LTT, less than total thyroidectomy; OT, open thyroidectomy; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; TT, total thyroidectomy; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Pooled surgical outcomes

Table 5 shows the pooled surgical outcomes of patients between ET and OT groups from all eligible studies.

Table 5.

Pooled surgical outcomes between ET and OT groups from all eligible studies

| Outcomes | ET | OT | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intraoperative outcomes | |||

| Operative time (minutes) | 142.0±45.9 | 92.3±36.6 | 7, 27–31, 34–36 |

| No of retrieved LNs | 4.3±4.1 | 4.7±4.0 | 7, 27–31, 33–35 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 19.6±24.5 | 14.5±9.8 | 7, 31, 34, 36 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Duration of drainage (days) | 5.9±1.9 | 4.6±2.0 | 31, 34, 36 |

| Volume of drainage (mL) | 202.3±142.0 | 112.7±56.9 | 28, 29, 31, 34, 36 |

| Hospitalization period (days) | 5.3±2.5 | 4.8±2.9 | 27–30, 34, 36 |

| Transient RLN palsy, n (%) | 64 (8.3) | 60 (3.3) | 7, 26–29, 31–36 |

| Permanent RLN palsy, n (%) | 7 (1.1) | 8 (0.5) | 26–29, 32–36 |

| Transient hypocalcemia, n (%) | 116 (20.9) | 366 (25.8) | 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34–36 |

| Permanent hypocalcemia, n (%) | 10 (1.9) | 31 (2.2) | 26, 28, 29, 32, 34–36 |

| Hematoma or bleeding, n (%) | 13 (1.9) | 17 (1.1) | 7, 26–32, 35, 36 |

| Seroma, n (%) | 10 (3.9) | 9 (2.5) | 7, 27–29 |

| Oncological outcomes | |||

| sTg <1.0 ng/mL, n (%) | 9 (31.0) | 176 (51.3) | 26, 32 |

| Tumor recurrences, n (%) | 6 (1.5) | 31 (2.6) | 26, 29–32, 36 |

Abbreviations: ET, endoscopic thyroidectomy; LN, lymph node; OT, open thyroidectomy; RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; sTg, stimulated thyroglobulin.

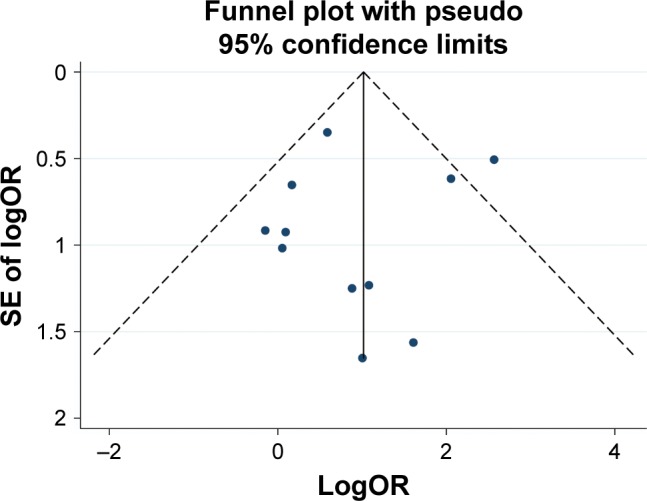

Publication bias

Figure 6 shows a funnel plot of the studies reporting on transient RLN palsy. Begg’s test (P=0.276) and Egger’s test (P=0.753) showed no statistical publication bias in the studies reporting on transient RLN palsy.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of transient recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy in all included studies.

Discussion

PTC is a subtype of differentiated thyroid cancer and surgery remains the primary therapeutic method for thyroid cancer. However, an obvious scar on the neck left after conventional OT causes psychological concerns in patients. With the popularity of endoscopic instruments, ET has been an attractive alternative to open surgery for the treatment of PTC. Owing to the limited number of studies comparing the outcomes between ET and OT, the general application of ET for PTC remains controversial. Unlike the previous meta-analysis, which included patients with PTMC only,16 our study also recruited patients with tumor sizes larger than PTMC. Furthermore, many new studies with a greater number of patients have been published in recent years. Therefore, we aimed to perform a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the clinical value of ET in adult patients with PTC.

The results of our meta-analysis showed that the operative time in the ET group was longer than that in the OT group. This may be attributed to three reasons. First, more time is needed to create the skin flap.31,32 Second, the meticulous bleeding control and careful lymph-node dissection require longer operation times.7,30 Third, surgeon experience and skills affect the operation times.19,29,37 The volume of fluid drainage and the time taken to remove the drainage tube in the ET group were much greater than in the OT group. It has been suggested that more dissection is needed to achieve the necessary working space.28 Furthermore, the longer postoperative hospitalization period in ET suggests a longer recovery period than for OT, especially when performing TT.

In terms of the number of lymph nodes dissected, our meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant difference between the ET and OT groups. This finding may indicate that the clearance of lymph nodes is comparable between the two groups. The previous meta-analysis showed that the number of lymph nodes dissected is less in the ET group, but no significant difference existed in the subgroup analysis,16 which is in concordance with our result.

RLN palsy and hypocalcemia are the major complications of thyroid surgery. Our meta-analysis showed that ET was associated with a significantly greater risk of transient RLN palsy than OT, which was not consistent with the previous meta-analysis.16 In the sensitivity analysis, the significant difference still existed. It is worth noting that endoscopic magnification with high-definition monitors is better for detecting the RLN. However, the similar or even worse risk of transient RLN palsy in ET relative to OT remains disappointing.12,38 Chung et al reported that 25.2% (26/103) of patients experienced transient RLN palsy and proposed that thermal damage caused by the ultrasonic scalpel may injure the RLN.26 Tan et al adopted the same viewpoint.31 Another reason may be that ET represents a different anatomic surgery approach, which is not familiar to traditional thyroid surgeons.39,40 Sun and Dionigi proposed that surgeons must have an excellent understanding of the RLN in terms of identification and suggested that intraoperative neural monitoring may be a good choice to avoid RLN palsy.41 It was an interesting finding that in the subgroup analysis, transient RLN palsy was comparable between the two groups in TT, but not in LTT. We consider that the risk of transient RLN palsy can be greatly reduced as long as the surgeon is experienced in ET, and good exposure and protection of the RLN are achieved during surgery. In addition, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of permanent RLN palsy, transient hypocalcemia, permanent hypocalcemia, hematoma or seroma.

Oncological outcomes, such as tumor recurrences and completeness of thyroid resection, are highly valued by surgeons. According to the American Thyroid Association guidelines, sTg may be helpful in predicting disease status.42 Only two studies recorded the number of patients with sTg <1 ng/mL,26,32 and our results demonstrated that the OT group may be associated with cleaner resection. Similarly, Kim et al found that the ET group showed higher postoperative thyroglobulin levels (2.4±6.3 ng/mL) than the OT group (0.8±2.0 ng/mL).28 This indicates that OT superior to ET in sTg levels presenting completeness of thyroid resection. In contrast, Jeong et al enrolled 275 PTMC patients who underwent ET and reported that all thyroidectomized patients had <1 ng/mL of postoperative serum thyroglobulin.24 With regard to tumor recurrences, the results showed no significant differences between the two groups, and three studies reported no tumor recurrences during the follow-up period.29,31,36 However, the results should be interpreted with caution. This is because, first, there were still insufficient available data on sTg levels. Second, data on postoperative follow-up were lacking and follow-up times were too short, because most PTCs have a slow progression and a good prognosis, with a 10-year survival rate of more than 90%.43 Third, tumor characteristics such as tumor size were not well matched between the two groups. Thus, unlike surgical-related outcomes, oncological outcomes are difficult to compare. Randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up assessment are needed to further evaluate oncological outcomes.

There are several limitations in our meta-analysis. First, all studies included were non-randomized controlled trials, which could lead to a higher risk of potential selection and reporting bias than randomized controlled trials. Second, some heterogeneity was observed for certain results. This may be related to differences among patient and tumor characteristics, the surgeons’ experience and the surgical approaches. Third, transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy (TOET) has received attention in recent years, but no reports have compared OT with TOET in total thyroid cancer. Most patients who undergo TOET have benign lesions,44 and many reports are on initial experiences45,46 or robot-assisted surgery.47,48 In addition, cosmetic results and quality of life are difficult to assess because of the few well-accepted tools available to study such outcomes.40

Conclusion

Compared with OT, ET is disappointing in terms of operation and drainage time, amount of drainage fluid, hospital stay and transient RLN palsy, whereas other complications appear comparable. In addition, despite the similar tumor recurrence rates, the level of surgical completeness in ET may not be as good as that in OT. Therefore, the application of ET for patients with PTC should be conducted carefully, and further prospective studies with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the oncological effectiveness of ET.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (numbers 81602471, 81672729 and 8167284), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (numbers LY19H160281, LY15H160020 and Q16H160010) and a grant from a sub-project of the China National Program on Key Basic Research Project (973 Program) (number 2014CB744505).

Footnotes

Author contributions

J Zhou and L Wang designed the study; J Zhou and C Chen wrote the manuscript; C Chen, S Huang, A Huang, Y Jia and J Wang analyzed the data and interpreted the results. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Davies L, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(4):317–322. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore SL. Thyroid Cancer Pathology. In: Vinjamuri S, editor. PET/CT in Thyroid Cancer. Cham: Springer; 2018. pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan CT, Cheah WK, Delbridge L. “Scarless” (in the neck) endoscopic thyroidectomy (SET): an evidence-based review of published techniques. World J Surg. 2008;32(7):1349–1357. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hüscher CS, Chiodini S, Napolitano C, Recher A. Endoscopic right thyroid lobectomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):877. doi: 10.1007/s004649900476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohgami M, Ishii S, Arisawa Y, et al. Scarless endoscopic thyroidectomy: breast approach for better cosmesis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang JK, Ma L, Song WH, Lu BY, Huang YB, Dong HM. Quality of life and cosmetic result of single-port access endoscopic thyroidectomy via axillary approach in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4053–4059. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S99980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimazu K, Shiba E, Tamaki Y, et al. Endoscopic thyroid surgery through the axillo-bilateral-breast approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13(3):196–201. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Z, Deng X, Fan Y, Wu B. Single-port endoscopic thyroidectomy via a submental approach: report of an initial experience. Head Neck. 2014;36(7):E60–E64. doi: 10.1002/hed.23213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J, Wang C, Li J, et al. Complete Endoscopic Thyroidectomy via Oral Vestibular Approach Versus Areola Approach for Treatment of Thyroid Diseases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25(6):470–476. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandil EH, Noureldine SI, Yao L, Slakey DP. Robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy: an examination of the first one hundred cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(4):558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dionigi G, Boni L, Duran-Poveda M. Evolution of endoscopic thyroidectomy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(12):3951–3952. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1763-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang BH, Lo CY. Technological innovations in surgical approach for thyroid cancer. J Oncol. 2010;2010:490719. doi: 10.1155/2010/490719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terris DJ. Surgical Approaches to the Thyroid Gland. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(5):515–517. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JH, Choi YJ, Kim JA, et al. Thyroid cancer that developed around the operative bed and subcutaneous tunnel after endoscopic thyroidectomy via a breast approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18(2):197–201. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318168dda4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Liu K, Xiong J, Zhu J. Total endoscopic versus conventional open thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(2):464–468. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen H, Shan C, Qiu M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy versus open thyroidectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24(3):199–206. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182a47a40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang YC, Liu K, Xiong JJ, Zhu JQ. Robotic thyroidectomy versus conventional open thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer: meta-analysis. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129(6):558–567. doi: 10.1017/S002221511500122X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho MJ, Park KS, Cho MJ, Yoo YB, Yang JH. A comparative analysis of endoscopic thyroidectomy versus conventional thyroidectomy in clinically lymph node negative thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;88(2):69–76. doi: 10.4174/astr.2015.88.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koh YW, Park JH, Kim JW, Lee SW, Choi EC. Endoscopic hemithyroidectomy with prophylactic ipsilateral central neck dissection via an unilateral axillo-breast approach without gas insufflation for unilateral micropapillary thyroid carcinoma: preliminary report. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(1):188–197. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im HJ, Koo Doh, Paeng JC, et al. Evaluation of surgical completeness in endoscopic thyroidectomy compared with open thyroidectomy with regard to remnant ablation. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(2):148–151. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182335fdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong JJ, Kang SW, Yun JS, et al. Comparative study of endoscopic thyroidectomy versus conventional open thyroidectomy in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(6):477–480. doi: 10.1002/jso.21367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim EY, Lee KH, Park YL, et al. Single-incision, gasless, endoscopic trans-axillary total thyroidectomy: A feasible and oncologic safe surgery in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27(11):1158–1164. doi: 10.1089/lap.2016.0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung YS, Choe JH, Kang KH, et al. Endoscopic thyroidectomy for thyroid malignancies: comparison with conventional open thyroidec-tomy. World J Surg. 2007;31(12):2302–2306. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong HJ, Kim WS, Koh YW, et al. Endoscopic thyroidectomy via an axillo-breast approach without gas insufflation for benign thyroid nodules and micropapillary carcinomas: preliminary results. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52(4):643–654. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.4.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim WW, Kim JS, Hur SM, et al. Is robotic surgery superior to endoscopic and open surgeries in thyroid cancer? World J Surg. 2011;35(4):779–784. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tae K, Ji YB, Cho SH, Kim KR, Kim DW, Kim DS. Initial experience with a gasless unilateral axillo-breast or axillary approach endoscopic thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: comparison with conventional open thyroidectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(3):162–169. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318218d1a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee H, Lee J, Sung KY. Comparative study comparing endoscopic thyroidectomy using the axillary approach and open thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:269. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan Z, Gu J, Han Q, et al. Comparison of conventional open thyroidec-tomy and endoscopic thyroidectomy via breast approach for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2015/239610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SK, Kang SY, Youn HJ, Jung SH. Comparison of conventional thyroidectomy and endoscopic thyroidectomy via axillo-bilateral breast approach in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(8):3419–3425. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MC, Park H, Lee BC, Lee GH, Choi IJ. Comparison of quality of life between open and endoscopic thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38:E827–E831. doi: 10.1002/hed.24108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park KN, Jung CH, Mok JO, Kwak JJ, Lee SW. Prospective comparative study of endoscopic via unilateral axillobreast approach versus open conventional total thyroidectomy in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(9):3797–3801. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiang D, Xie L, Li Z, Wang P, Ye M, Zhu M. Endoscopic thyroidectomy along with bilateral central neck dissection (ETBC) increases the risk of transient hypoparathyroidism for patients with thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine. 2016;53(3):747–753. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0884-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren X, Dai Z, Sha H, Wu J, Hong X, Xiu Z. Comparative study of endoscopic thyroidectomy via a breast approach versus conventional open thyroidectomy in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients. Biomedical Research. 2017;28(12):5315–5320. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin S, Chen ZH, Jiang HG, Yu JR. Robotic thyroidectomy versus endoscopic thyroidectomy: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10(1):239. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dionigi G, Duran-Poveda M. New approaches in thyroid surgery: is there an increased risk of nerve injury? Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(3):252–253. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1869-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anuwong A, Ketwong K, Jitpratoom P, Sasanakietkul T, Duh QY. Safety and outcomes of the transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach. JAMA Surg. 2017;153(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang BH, Wong CK, Tsang JS, Wong KP, Wan KY. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing surgically-related complications between robotic-assisted thyroidectomy and conventional open thyroi-dectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(3):850–861. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun H, Dionigi G. Endoscopic thyroid surgery requires surgeons, patient candidacy & neural monitoring. Int J Endocr Oncol. 2018;5(1):IJE02. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan S, Zhao W, Wang B, Zhang L. Standardization of simple auxiliary method beneficial to total endoscopic thyroidectomy on patients with PTC, based on retrospective study of 356 cases. Endocrine. 2018;61(1):51–57. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anuwong A, Ketwong K, Jitpratoom P, Sasanakietkul T, Duh QY. Safety and Outcomes of the Transoral Endoscopic Thyroidectomy Vestibular Approach. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(1):21. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi JW, Yoon SG, Kim HS, et al. Transoral endoscopic surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma: initial experiences of a single surgeon in South Korea. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2018;95(2):73–79. doi: 10.4174/astr.2018.95.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Müller V, Mogl M, Seika P, et al. How I do it: new dissector device allows for effective operative field in transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery using vestibular approach. Surg Innov. 2018;25(5):444–449. doi: 10.1177/1553350618785281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell JO, Noureldine SI, Al Khadem MG, et al. Transoral robotic thyroidectomy: a preclinical feasibility study using the da Vinci Xi platform. J Robot Surg. 2017;11(3):341–346. doi: 10.1007/s11701-016-0661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aidan P, Arora A, Lorincz B, Tolley N, Garas G. Robotic thyroid surgery: current perspectives and future considerations. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2018 May 22; doi: 10.1159/000488354. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]