YidC proteins are membrane-localized chaperone insertases that are universally conserved in all bacteria and are traditionally studied in the context of membrane protein insertion and assembly. Both YidC paralogs of the cariogenic pathogen Streptococcus mutans are required for proper envelope biogenesis and full virulence, indicating that these proteins may also contribute to optimal biofilm formation in streptococci. Here, we show that the deletion of either yidC results in changes to the structure and physical properties of the EPS matrix produced by S. mutans, ultimately impairing optimal biofilm development, diminishing its mechanical stability, and facilitating its removal. Importantly, the universal conservation of bacterial yidC orthologs, combined with our findings, provide a rationale for YidC as a possible drug target for antibiofilm therapies.

KEYWORDS: biofilm, dental caries, EPS, Gtf, Streptococcus mutans, YidC

ABSTRACT

Proper envelope biogenesis of Streptococcus mutans, a biofilm-forming and dental caries-causing oral pathogen, requires two paralogs (yidC1 and yidC2) of the universally conserved YidC/Oxa1/Alb3 family of membrane integral chaperones and insertases. The deletion of either paralog attenuates virulence in vivo, but the mechanisms of disruption remain unclear. Here, we determined whether the deletion of yidC affects cell surface properties, extracellular glucan production, and/or the structural organization of the exopolysaccharide (EPS) matrix and biophysical properties of S. mutans biofilm. Compared to the wild type, the ΔyidC2 mutant lacked staining with fluorescent vancomycin at the division septum, while the ΔyidC1 mutant resembled the wild type. Additionally, the deletion of either yidC1 or yidC2 resulted in less insoluble glucan synthesis but produced more soluble glucans, especially at early and mid-exponential-growth phases. Alteration of glucan synthesis by both mutants yielded biofilms with less dry weight and insoluble EPS. In particular, the deletion of yidC2 resulted in a significant reduction in biofilm biomass and pronounced defects in the spatial organization of the EPS matrix, thus modifying the three-dimensional (3D) biofilm architecture. The defective biofilm harbored smaller bacterial clusters with high cell density and less surrounding EPS than those of the wild type, which was stiffer in compression yet more susceptible to removal by shear. Together, our results indicate that the elimination of either yidC paralog results in changes to the cell envelope and glucan production that ultimately disrupts biofilm development and EPS matrix structure/composition, thereby altering the physical properties of the biofilms and facilitating their removal. YidC proteins, therefore, represent potential therapeutic targets for cariogenic biofilm control.

IMPORTANCE YidC proteins are membrane-localized chaperone insertases that are universally conserved in all bacteria and are traditionally studied in the context of membrane protein insertion and assembly. Both YidC paralogs of the cariogenic pathogen Streptococcus mutans are required for proper envelope biogenesis and full virulence, indicating that these proteins may also contribute to optimal biofilm formation in streptococci. Here, we show that the deletion of either yidC results in changes to the structure and physical properties of the EPS matrix produced by S. mutans, ultimately impairing optimal biofilm development, diminishing its mechanical stability, and facilitating its removal. Importantly, the universal conservation of bacterial yidC orthologs, combined with our findings, provide a rationale for YidC as a possible drug target for antibiofilm therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus mutans resides primarily in biofilms formed on tooth surfaces (termed dental plaque), often leading to dental caries, a prevalent and costly oral disease that causes damage (cavitation) to the mineralized tissue (1–3). While S. mutans is a minor component of the total bacterial community under healthy conditions (4), this opportunistic pathogen can rapidly assemble virulent biofilms via the production of exopolysaccharides (EPS) when conditions are conducive to dental caries, i.e., high exposure to dietary sugars (5, 6). S. mutans secretes glucosyltransferase exoenzymes (Gtfs), which can bind to both tooth and microbial surfaces, as well as promote bacterial accumulation and EPS-rich matrix assembly (5). When sucrose becomes increasingly available, insoluble glucans produced by the Gtf enzymes of S. mutans embed the bacterial cells in a polymeric matrix that enhances adhesion/cohesion and creates diffusion-limiting milieus, thereby fundamentally changing the architecture and physical properties of the dental plaque biofilm (6). The metabolic activity of the microorganisms within the matrix can result in the formation of acidic and anaerobic microenvironments (6, 7), which progressively shift the bacterial community to one enriched in acidogenic and acid-tolerant species (8). If biofilm persists, the acidification of the microenvironment at the tooth-biofilm interface ultimately results in acid dissolution of the adjacent enamel, causing the onset of cavitation (3). Thus, the composition of the EPS matrix can both impact biofilm formation and accumulation and create a pathogenic niche in close proximity to the tooth surface.

As with many Gram-positive bacterial pathogens, the majority of S. mutans virulence factors are either secreted, attached to the cell wall, or located in the cytoplasmic membrane (9); this includes the membrane-associated glucan binding proteins (Gbps) and the secreted glucosyltransferases (Gtfs) required for cariogenic biofilm formation (10). During bacterial protein translocation, best characterized in Escherichia coli, proteins with N-terminal signal sequences destined for either insertion into or secretion across the cytoplasmic membrane are targeted to the SecYEG translocon (reviewed in references 11 and 12). While many components of protein translocation pathways are universally conserved, there are differences in the accessory components and essentiality among bacterial species (12–15). The signal recognition particle (SRP), SecYEG, and YidC are found in all bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotic organelles; however, streptococci do not have SecB, SecD, or SecF and harbor two YidC paralogues of the universally conserved YidC/Oxa1/Alb3 protein family found in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts (16–19). E. coli and other Gram-negative organisms possess one yidC gene, whereas almost all Gram-positive organisms possess two or more (20).

Bacterial YidC proteins function as membrane integral chaperone/insertases which insert membrane proteins into the lipid bilayer in conjunction with the SecYEG translocon (sec-dependent pathway) (21) and/or the signal recognition particle (SRP) cotranslational protein translocation pathway (22). In the case of a few small single-transmembrane domain hydrophobic proteins, a Sec-independent YidC-only pathway is sufficient for membrane insertion (23). There is growing evidence that YidC proteins may also impact cell surface biogenesis and maturation of secreted proteins (24–26). Staphylococcus aureus YidC was recently identified as a target of a compound capable of inhibiting biofilm formation and reducing virulence (27).

The two YidC paralogs of S. mutans are 27% identical and 48% similar based on protein sequence (EMBOSS Needle, EBlosum62). Each is predicted to contain five transmembrane domains after processing and removal of their signal peptides by SPaseII (28). While there are a number of conserved residues within the transmembrane domains of bacterial YidC proteins (29), the cytoplasmically located C-terminal tails of S. mutans YidC1 and YidC2 differ in both length and charge. Similarly, the length and charge distribution of residues within the two cytoplasmic loops, which in Bacillus halodurans interact to form what is known as the C1 domain (30), differ between S. mutans YidC1 and YidC2. It has been reported that the C-terminal tail of either S. mutans YidC protein can facilitate interactions with translating ribosomes in a heterologous E. coli system, possibly allowing for cotranslational translocation (31) and explaining why elimination of the universally conserved cotranslational SRP pathway is dispensable in S. mutans (16). Both YidC proteins appear to be constitutively expressed in S. mutans; however, yidC2 expression also appears to be influenced by the LiaFSR three-component system (A. Combs, A. C. Malaney, H. Chang, and S. R. Palmer, unpublished data) that senses and responds to cell envelope stress (32).

The deletion of E. coli yidC is lethal (33), as is simultaneous deletion of yidC1 and yidC2 in S. mutans (25). A single deletion of yidC1 has little apparent effect on growth or stress tolerance, whereas the disruption of yidC2 results in a pronounced stress-sensitive phenotype (acid, osmotic, and oxidative) similar to that with disruption of the SRP pathway (16, 25). In experiments in which DNA encoding the C-terminal tails of yidC1 and yidC2 were exchanged to generate chimeric proteins, the yidC1-C2 chimeric construct partially restored stress tolerance to the ΔyidC2 mutant. In contrast, when DNA encoding the C-terminal tail of YidC1 replaced that of yidC2 (yidC2-C1), a dominant negative effect on growth and protein secretion was observed (25). These results highlight the functional differences between S. mutans YidC1 and YidC2 and demonstrate that differences in their C-terminal tails are at least partially responsible for their respective functions.

Despite substantial phenotypic differences between yidC1 and yidC2 deletion strains observed in in vitro studies, both mutants are attenuated for virulence in a rat model of dental caries (25). Thus, under in vivo conditions conducive to disease (high-sucrose diet), both S. mutans yidC paralogs are required for full virulence.

Therefore, defects in cell membrane and cell surface biogenesis stemming from the elimination of yidC1 or yidC2 might also impact the ability of S. mutans to produce insoluble glucans that are critical for extracellular matrix assembly and biofilm formation under cariogenic conditions. The present study combines microscopy and biophysical-biochemical techniques to evaluate the consequences of yidC1 and yidC2 deletion on cell morphology and glucan synthesis in S. mutans and evaluates the respective contributions of YidC1 and YidC2 to biofilm formation, structural integrity, and EPS matrix production.

RESULTS

yidC mutants have aberrant cell morphology, display defects in division septa, and affect cell wall characteristics.

While the growth rate of the ΔyidC1 mutant in planktonic culture is very similar to that of wild type, the ΔyidC2 mutant has a reduced growth rate and self-aggregates. In the present study, the cell morphology of planktonically grown cells was compared by Gram staining. Representative images of Gram-stained cells are shown in Fig. 1A. We observed typical cell morphology for S. mutans in the wild type and ΔyidC1 mutant, with cells forming either pairs or longer chains. However, the ΔyidC2 mutant cells formed large clumps and made fewer and shorter chains. In addition, the ΔyidC2 mutant cells were surrounded by a material that stained light pink, which could be cytoplasmic content (i.e., genomic DNA) that bound the safranin counterstain, potentially indicating that the ΔyidC2 mutant may lyse easier due to cell wall or membrane defects.

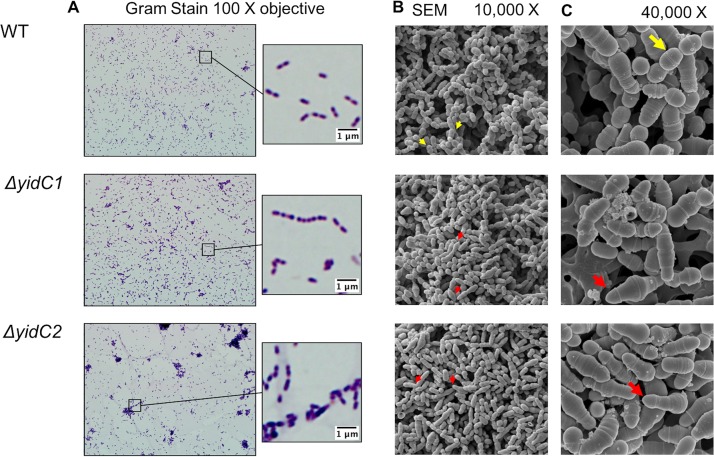

FIG 1.

Gram-stained and SEM images of S. mutans wild type and yidC1 and yidC2 mutants. (A) Gram stain results of WT S. mutans UA159 and yidC1 and yidC2 mutants visualized with a 100× objective. Boxes indicate location of zoomed-in image in right images. (B and C) SEM images of indicated strains taken at ×10,000 (B) and ×40,000 (C) magnification. Red arrows indicate aberrantly shaped cells with multiple division septa, and yellow arrows indicate ovococci typical of S. mutans.

In order to compare the details of the cell surface and cell wall structures of the wild-type and mutant strains, scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM and TEM, respectively) were performed. By SEM, there were clear visual differences between the wild-type and yidC mutants, where both yidC mutant samples contained more cells with multiple division septa than did the wild type (Fig. 1B). In addition, there was asymmetry in the dividing cells in both yidC mutant samples, with multiple bowling pin-shaped elongated cells evident (red arrows, Fig. 1B and C). In addition, there was an absence of normally shaped ovococci which were apparent in the wild type (yellow arrows, Fig. 1B and C). To compare the internal cell structures, such as cell wall thickness and division septa, TEM was performed on ultrathin (70-nm) sections from the wild-type and yidC mutant samples. Even at the lowest magnification (×4,000), differences could be seen between wild-type and the yidC mutants, with multiple cross-sections of elongated dividing cells present in the mutant samples (arrows, Fig. 2A). At ×25,000 and ×60,000 magnifications, normally dividing ovococci were apparent in the wild-type samples, while many asymmetrically dividing cells were present in the ΔyidC1 and ΔyidC2 mutant samples (arrows, Fig. 2B and C). Figure 2D shows a representative image at ×100,000 with visible cell walls from each strain. At this high magnification, differences in the quality of staining and presence of cell walls were noticeable between the mutants and wild type; the ΔyidC2 mutant sample had fewer cells with intact cell walls, while the ΔyidC1 mutant sample had more cells with intact cell walls than did the wild-type sample.

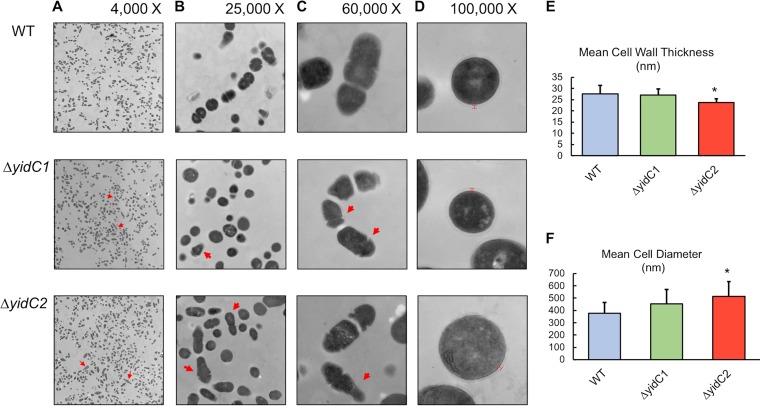

FIG 2.

Transmission electron micrographs of S. mutans wild type and yidC1 and yidC2 mutants. (A to C) Representative micrographs of each strain taken at ×4,000 (A), ×25,000 (B), and ×60,000 (C) magnification. (D) Micrographs of cells with intact cell walls taken at ×100,000 magnification. (E) Mean cell wall thickness of the wild type (WT) and yidC mutants. (F) Mean cell diameter of wild-type and yidC mutant cells. Statistical differences compared to WT are indicated by an asterisk (P < 0.05). In the micrographs, arrows indicate abnormally shaped dividing cells and red bars indicate where measurements were taken for cell wall thickness.

Using calibrated micrograph images, cell wall thickness and cell diameter were measured using ImageJ (Fig. 2E and F). The ΔyidC2 mutant cells had significantly thinner cell walls (P < 0.013) (Fig. 2E), and the diameter of the ΔyidC2 mutant cells was significantly larger than that of the wild type (Fig. 2F). The ΔyidC1 mutant had a cell wall thickness similar to that of the wild type, but staining of the cell walls with uranyl acetate was consistently more pronounced in the ΔyidC1 mutant samples, which may suggest a higher protein content in the cell wall.

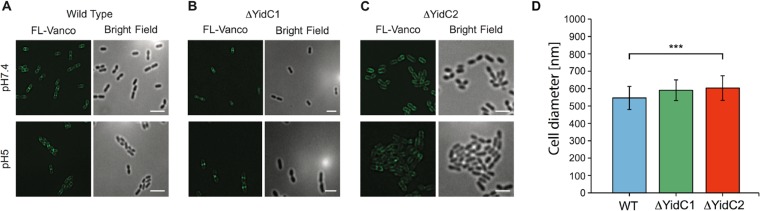

Given the differences in cell surface and cell wall characteristics observed for the yidC mutants, we also compared the de novo cell wall synthesis of each strain using fluorescently labeled vancomycin and superresolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM). As shown in Fig. 3, staining of the division septa of the ΔyidC2 mutant was notably less pronounced than that observed for either the wild type or ΔyidC1 mutant strain, suggesting a potential defect in cell wall synthesis in the absence of yidC2. Consistent with TEM data, the ΔyidC2 mutant cells were also significantly larger than those of the wild type when evaluated by SIM (Fig. 3D).

FIG 3.

Comparison of de novo cell wall synthesis measured by midcell localization of fluorescent vancomycin. (A to C) SIM images of cells grown either in pH 7.4 or pH 5.0 medium, as follows: wild-type S. mutans (A), ΔyidC1 mutant (B), and ΔyidC2 mutant (C). Scale bars indicate 2 µm. (D) Cell diameter measured in Fiji (imageJ) using calibrated images.

Glucan production by planktonic cultures of yidC1 and/or yidC2 mutants differs from wild type and alters biofilm development.

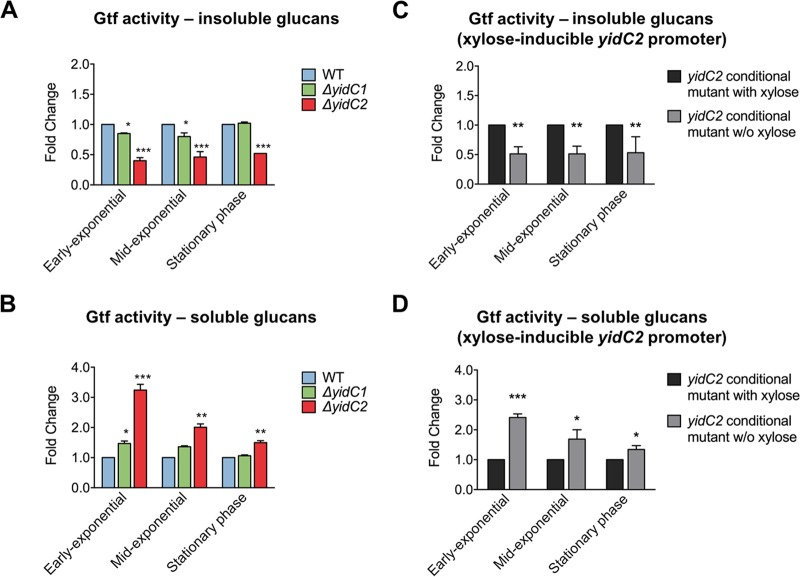

To examine whether the elimination of S. mutans yidC1 and/or yidC2 mutants might also affect extracellular proteins, we examined glucosyltransferase (Gtf) activity levels since these are secreted enzymes in S. mutans. Using planktonic cultures, we compared the Gtf activities of culture supernatants collected from early exponential-, mid-exponential-, and stationary-phase cultures. Compared to the wild-type parent, the ΔyidC2 mutant produced significantly less insoluble and significantly more soluble glucan during all growth phases (Fig. 4A and B). The effect of elimination of yidC2 on soluble glucan production was most pronounced during early exponential phase (Fig. 4B). To verify that the change in insoluble/soluble glucans produced was due to the deletion of yidC2 alone, a construct was generated in which a xylose-inducible promoter controlled the expression of yidC2 (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Therefore, yidC2 was expressed only when xylose was present in the growth medium (Fig. S1B). As shown in Fig. 4C and D, the behavior of the conditional expression strain grown with xylose resembled that of the wild-type strain, whereas when grown without xylose, the results paralleled those of the ΔyidC2 mutant strain. In contrast to the elimination of yidC2, the elimination of yidC1 had a more modest impact. Significantly less insoluble glucan was only observed for the ΔyidC1 mutant than for the wild type during early and mid-exponential phases (Fig. 4A). Significantly more soluble glucan production was only observed during the early exponential phase for the ΔyidC1 mutant than for the wild type (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Growth-phase-dependent extracellular Gtf activity associated with S. mutans wild type and yidC1 and yidC2 mutants. (A and B) Insoluble glucans (A) and soluble glucans (B) produced by Gtf exoenzymes in culture supernatant derived from planktonically grown S. mutans strains. (C and D) Insoluble glucans (C) and soluble glucans (D) produced by a complemented yidC2 mutant strain grown with or without (w/o) 1% xylose, where yidC2 is expressed only in the presence of xylose. Statistical differences compared to the wild type or in the presence of xylose are indicated as follows: *, P ≤ 0.01; **, P ≤ 0.001; and ***, P ≤ 0.0001.

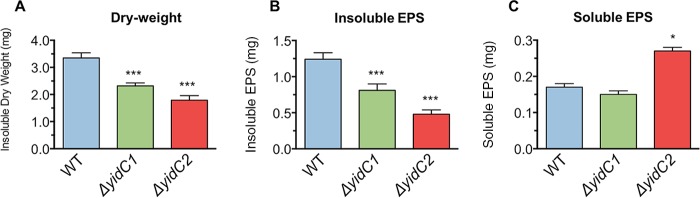

To evaluate how the observed changes in secreted Gtf enzyme activity in the yidC mutants affect biofilm development, we compared the biomass (dry weight) and the amount of extracellular polysaccharides between the biofilms formed by each yidC mutant and wild-type strain. The total biomass of a biofilm is a combination of bacterial cells, proteins, and the constituents of the extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) matrix, especially water-soluble and water-insoluble glucans (34). Both the ΔyidC1 and ΔyidC2 mutants formed biofilms with significantly less (33% and 48%, respectively) biomass (milligrams of total dry weight) than the wild type (Fig. 5A). In addition, there were significant differences in the amounts and proportions of soluble and insoluble EPS. The ΔyidC1 and ΔyidC2 mutants both contained significantly less insoluble EPS in their biofilms than the wild type (Fig. 5B). In particular, the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm showed a substantial reduction in insoluble EPS (>2.5-fold less than the wild type). In contrast, the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm harbored significantly more soluble EPS (Fig. 5C). These results are consistent with the alterations in secreted Gtf activity observed for each glucan type (Fig. 4).

FIG 5.

Composition of biofilms formed by S. mutans wild type and yidC1 and yidC2 mutants in the presence of 1% sucrose. (A) Total dry weight of the resulting biofilms produced by the respective strains. (B and C) Amounts of insoluble (B) and soluble (C) polysaccharides in the biofilms. Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *, P ≤ 0.01; **, P ≤ 0.001; and ***, P ≤ 0.0001.

The yidC2 mutant biofilms contain smaller microcolonies and demonstrate a defective matrix.

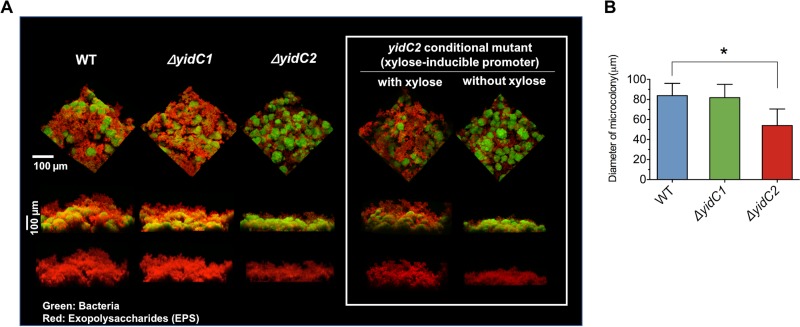

Next, we wanted to determine how the changes in EPS composition by yidC mutants alter the biofilm structure and the extracellular matrix development. We compared the 3D architecture of biofilms formed by wild-type S. mutans to those of the ΔyidC1 or ΔyidC2 mutants using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and quantitative computational analysis, as detailed previously (35). Figure 6A shows reconstructed renderings of biofilms of each of the S. mutans strains. Although only one representative image is presented for practicality, these analyses were performed in triplicate, and at least 10 images were recorded under confocal microscopy. Consistent with biochemical data, we observed clear structural changes in the biofilm formed by the ΔyidC2 mutant, which contained fewer and sparsely distributed EPS (red) than the wild-type biofilm. Furthermore, orthogonal views (Fig. 6A, bottom) showed reduced accumulation and thinner EPS, particularly at the upper layers of the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm compared to the other two strains, indicating defective EPS matrix assembly. Interestingly, the biofilms formed between the ΔyidC1 mutant and wild type appeared to be similar, despite the measured differences in their glucan contents. The biovolume of the EPS matrix from each biofilm quantified by COMSTAT revealed that ΔyidC2 mutant biofilms contained ∼35% less EPS (versus intact S. mutans biofilm), while ΔyidC1 mutant biofilms harbored a similar amount. Additionally, the size of microcolonies formed in the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm was significantly smaller than that in wild-type biofilms (Fig. 6B) (P < 0.05), whereas no significant differences were observed for the ΔyidC1 mutant (P > 0.05). Similar results were observed when this experiment was repeated using the complemented yidC2 mutant strain in which yidC2 expression was controlled by a xylose-inducible promoter, such that biofilms resembled the wild-type parent strain when xylose was included in growth medium and resembled the ΔyidC2 mutant when xylose was not included (Fig. 6A, inset).

FIG 6.

CLSM of S. mutans wild type and yidC1 and yidC2 mutant biofilms. (A) Representative 3D images of biofilms formed by S. mutans UA159 (WT), yidC1 and yidC2 mutant strains, or the yidC2 complemented mutant strain with or without xylose (inset), grown in the presence of 1% sucrose. All biofilms were heterogeneous and consisted of distinct microcolonies of cells separated by interstitial channels. Bacteria were stained with SYTO 9 (in green), and EPS was labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 (in red). (B) Diameter of microcolonies. Statistical differences compared to the WT are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05.

The ΔyidC2 mutant produces stiffer biofilms that are more susceptible to shear.

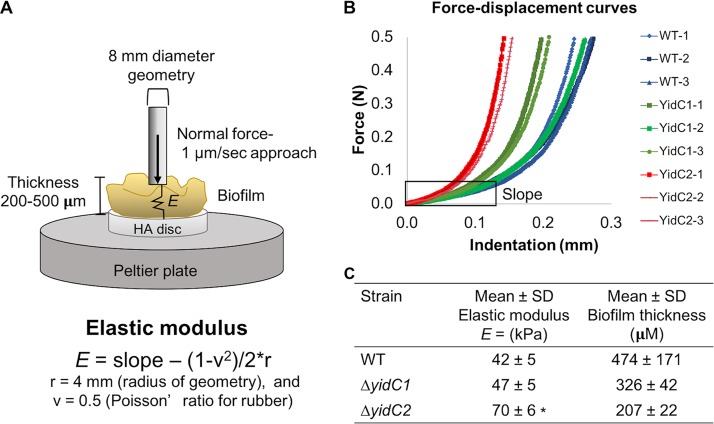

In general, bacterial biofilms behave like viscoelastic fluids, which provide the mechanical properties (adhesive and cohesive forces) (36, 37). Measuring the elastic modulus (E) of a biofilm can reveal important differences about the cohesive forces within the biofilm and can give an overall indication of global structural and physical differences within the matrix. To understand how the changes in the biofilm structures caused by the ΔyidC1 or ΔyidC2 mutation affect the mechanical properties of S. mutans biofilms, the elastic modulus was determined using an indentation/compression test (Fig. 7A). The elastic modulus of each biofilm was calculated from the early linear part of the force-displacement curve, where the geometry first came into contact with the biofilm (Fig. 7A and B). The elastic moduli of the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilms were significantly higher than those in wild-type biofilms (Fig. 7C), indicating that the ΔyidC2 mutant formed more rigid biofilms. In addition, the ΔyidC2 mutant formed thinner biofilms than did the wild type (Fig. 7C). These results are consistent with the other changes observed in the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilms, possibly due to differences in the ratio of soluble to insoluble glucans produced by this strain and in microcolony size. Further, the decrease in EPS matrix observed in the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilms likely results in more tightly packed cells, which could also help explain the distinct viscoelastic characteristic of this strain.

FIG 7.

Biofilm thickness and elastic moduli of S. mutans wild type and yidC1 and yidC2 mutants. The elastic modulus was calculated based an indentation/compression test performed on 96-h biofilms formed in the presence of 1% sucrose on HA discs. (A) Schematic of indentation/compression test performed on S. mutans biofilms. (B) Resulting force-displacement curves from compression analysis. The portion of the curves where the slope was calculated to determine the elastic modulus is indicated by a box. (C) Biofilm thickness and elastic modulus (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3) formed by wild-type S. mutans and the yidC mutants are shown. Statistical differences compared to the WT are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.003.

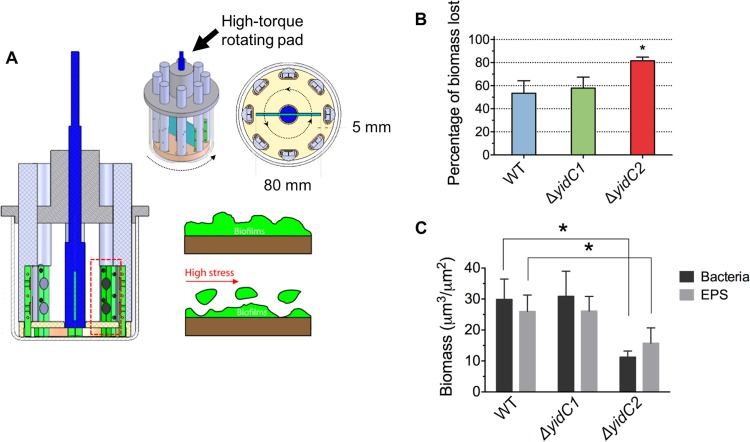

In addition, the mechanical stability of the biofilms was determined by measuring surface detachment of biofilm biomass exposed to shear stress. For these experiments, the biofilms were exposed to 1.78 N/m2 of shear stress for 10 min using a shear-induced biofilm mechanical strength tester (s-BMST) (Fig. 8A) (38). The amount of biomass before and after the shear stress was determined by dry weight and confocal imaging analysis (Fig. 8B and C). The ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm demonstrated the highest percentage of lost biomass (dry weight) after shear stress, indicating weakened mechanical stability (Fig. 8B). Likewise, quantitative imaging analysis using COMSTAT also revealed significantly less EPS and bacteria remaining after exposure to shear stress for the ΔyidC2 but not the ΔyidC1 mutant biofilm than for the wild type (Fig. 8C). These results are consistent with the reduced level of insoluble glucan observed for the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm in that the level of insoluble glucan has been shown to be directly associated with biofilm attachment strength (28). However, mechanical strength was inversely proportional to the stiffness of the biofilm and was reflected in the higher elastic modulus of the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm than that of the wild type. These results imply that the amount and distribution of EPS could impact the biophysical properties of the biofilm and facilitate its removal.

FIG 8.

Mechanical stability of biofilms under shear stress. (A) Schematic diagram of shear-induced biofilm mechanical strength tester. (B) The percentage of biomass lost after a shear stress of 1.78 N/m2 was applied to biofilms. (C) Bacteria and EPS biomass remaining on sHA surfaces after shear stress was determined via COMSTAT. Statistical differences compared to the WT are indicated by *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The phenotypic consequences of elimination of each of the two S. mutans yidC paralogs of the universally conserved YidC/Oxa1/Alb3 family differ (16, 39); however, we have found that proper surface biogenesis and attainment of characteristic virulence attributes of S. mutans depend to various extents on both of these membrane-localized chaperone insertases (25). Here, we show that mutations in either yidC1 or yidC2 impact cell morphology and cell wall properties of S. mutans, including alterations in septation and glucan production. These alterations, particularly those stemming from the deletion of yidC2, have profound consequences for EPS matrix assembly/structure, thus impacting the biophysical properties and mechanical stability of the S. mutans biofilm. This new information furthers our understanding of how YidC1 and YidC2 contribute to cell physiology and to the development of cohesive and adherent biofilms that are associated with dental caries (6).

As determined by SEM, both S. mutans yidC mutants displayed aberrant cell shape and formed elongated cells. The effects were more pronounced in the yidC2 mutant (Fig. 1C). In E. coli, yidC depletion similarly resulted in aberrant cell morphology, with cells forming longer bacilli than those in the wild type (24, 40). Although each of the S. mutans ΔyidC1 and ΔyidC2 mutants displayed differences in division septum frequency and cell shape in SEM experiments, only the ΔyidC2 mutant demonstrated a clearly altered staining pattern when live cells were labeled with fluorescent vancomycin and imaged using superresolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM) (Fig. 3). In this experiment, the ΔyidC1 mutant resembled wild-type cells. Division-specific penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), such as PBP3 of E. coli or PBP2B and PBP1 of Bacillus subtilis, localize at the division septum (41–43); hence, the altered staining of the ΔyidC2 mutant with the fluorescent antibiotic suggests an underlying contribution of YidC2 to the cell wall biosynthesis machinery. In TEM experiments, the ΔyidC2 mutant had measurably and significantly thinner cell walls with larger cell diameter than did the wild-type parent. The lack of a punctate pattern at the division septa with a more peripheral cell wall staining with fluorescent vancomycin observed for the ΔyidC2 mutant was not shared by an ffh mutant (16) of S. mutans, which lacks the integral Ffh component of the SRP pathway (data not shown). This finding is interesting since other phenotypic consequences are shared by the yidC2 and ffh mutants of S. mutans, such as decreased mutacin production and genetic competence, as well as impaired tolerance to environmental stressors (16, 39). Double-deletion mutants lacking both yidC2 and ffh are not viable, suggesting a high degree of functional redundancy and cooperation between these protein translocation machinery components. Our current results indicate a clear-cut instance in which YidC2 functions independently of the SRP pathway. In studies in E. coli, yidC depletion reduced the amount of the active form of PBPs, PBP2 and PBP3, required for cell elongation and cell division, respectively, and the authors of that study concluded that YidC mediates the folding of periplasmic domains of membrane proteins in E. coli (24). A PBP1a-deficient mutant of S. mutans resembles the S. mutans yidC1 and yidC2 mutants described herein (Fig. 1), producing long rod-like cells with multiple division septa that are also defective in biofilm formation (44). Taken together, these results suggest that some of the phenotypic changes observed for the S. mutans yidC mutants could be due to improperly folded PBPs that would consequently affect cell division and morphology. Additional experiments are needed to further investigate potential compositional changes in the cell walls of the yidC1 and yidC2 mutants and to identify the respective substrates responsible for these alterations to identify the specific roles that yidC1 and yidC2 each apparently play in cell wall development.

In addition to their roles in cell wall development and cell morphology, the elimination of each S. mutans yidC paralog impacted secreted enzymatic actitivites, causing significant alterations in extraceullular polysaccharide production (Fig. 4). The effects of deletion of yidC1 on soluble and insoluble EPS glucan production were modest and growth-phase dependent, with no observable impact at stationary phase. In contrast, the consequences of elimination of yidC2 were apparent during all growth phases, and the decrease in insoluble glucans and increase in soluble glucans were far more pronounced than those observed in the ΔyidC1 background. Insoluble glucan production is primarily associated with the enzymatic activity of the secreted GtfB exoenzyme, while GtfC produces a mixture of insoluble and soluble glucans (45). Because GtfBC activity is linked with EPS matrix assembly in cariogenic biofilms and manifestation of S. mutans virulence in vivo (5), the current data help explain the reduced levels of dental caries observed in rats infected with these mutants in a prior study (25). Although the entire spectrum of secretome and cell surface changes stemming from yidC mutations in S. mutans remains to be determined, both YidC1 and YidC2 may play important roles for the secretion of Gtf exoenzymes. While YidC proteins are well known to function as membrane integral chaperone/insertases that are involved in the insertion and assembly of multimeric membrane proteins (20), the results presented here lend further support to the growing evidence that bacterial YidC proteins can also impact secreted proteins and cell wall biogenesis (24–26).

Alterations in the physical properties of bacterial cells, such as changes in the cell wall composition or charge distribution that influence surface properties, are known to affect biofilm formation (46). We observed that the deletion of either yidC1 or yidC2 resulted in less overall biomass, with deviations in both the amount and type of EPS, thus altering the 3D biofilm architecture. The ΔyidC2 mutant strain produced less insoluble glucans and formed aberrant biofilms containing smaller cell clusters (or microcolonies) with sparser and thinner EPS matrix than the wild type. These data are consistent with previous observations that insoluble glucans directly mediate the development and size of microcolonies (34, 35, 47). In contrast, the ΔyidC1 mutant biofilms appeared to be similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 6), despite measurable growth-phase-dependent alterations observed in glucan production by culture supernatants derived from the ΔyidC1 mutant strain (Fig. 4). Previous studies have shown that a mutant lacking gtfB (insoluble glucan synthesis) was unable to develop EPS-microcolony complexes, despite some bacterial binding on the apatitic surface, whereas a strain defective in gtfC assembled a rudimentary EPS matrix with smaller microcolonies (35). Therefore, the greater disruption of insoluble glucan synthesis measured for the ΔyidC2 mutant than for the the ΔyidC1 mutant strain is consistent with the differences in biofilm architecture observed between these two mutants. In preliminary RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments comparing global gene expression of the yidC mutants to that of wild type, the ΔyidC2 mutant demonstrated 320 differentially expressed (DE) genes, including >4-fold decreased expression of both gtfB and gtfC (S. R. Palmer, unpublished data). In contrast, and consistent with its less severe phenotype, the ΔyidC1 mutant had very few DE genes compared to the wild type.

Interestingly, alterations in EPS composition stemming from yidC1 and yidC2 deletion influenced fundamental biophysical properties of S. mutans biofilms, but in different ways. Less insoluble EPS in the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm likely resulted in an elevation of stiffness (elastic modulus [E]) (Fig. 7), while the biofilm was more susceptible to shearing than was intact wild-type biofilm. Bacterial and EPS density may determine the mechanical properties of biofilm, as bacteria are stiffer than a polymer matrix (48). Thus, it is possible that a relatively high cell density (bacterial volume fraction) in the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm contributes to the enhanced stiffness of the biofilm observed in our compression experiments. Furthermore, elastic material can absorb stress energy through deformation. Therefore, the decreased insoluble EPS in the ΔyidC2 mutant likely reduced the elasticity of the biofilm. Insufficient EPS in biofilms may diminish cohesion between bacteria within biofilms (36, 38), such that during shear stress the biofilm fails along sliding planes and allows for more sloughing of cells. Indeed, the ΔyidC2 mutant biofilm was more easily detached when subjected to shear force (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with the biochemical test results, in that the structural integrity of S. mutans biofilms is determined by the EPS matrix composition, whereas increased mechanical stability is correlated with increased levels of insoluble α-1,3-glucan produced by GtfB and GtfC (38). It is important to note that in our experiments, biofilms were grown under static conditions, and it is possible that results would differ if the biofilms were grown in the presence of shear force.

Taken together, our current results demonstrate that S. mutans YidC1 and YidC2 contribute to cell wall biosynthesis and cell morphology, as well as to biofilm development and stability. The changes in the proportions of soluble/insoluble glucans produced by the yidC mutants influenced the structural integrity of the biofilm EPS matrix produced by S. mutans, thus impacting optimal biofilm development and attachment, which likely contributed to the various degrees of reduced virulence observed in a rat caries model (25). The biofilm EPS matrix produced by the ΔyidC2 mutant, in particular, was affected in such a way so as to increase susceptibility to shear stress and to facilitate biofilm removal. Thus, targeting S. mutans YidC proteins, especially YidC2, may be an effective adjunctive treatment to disrupt cariogenic biofilms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Streptococcus mutans UA159 (ATCC 700610; serotype C) came from the laboratory stocks of R. A. Burne at the University of Florida. S. mutans UA159 and its derivatives were routinely grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (BD Bacto) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment, unless otherwise indicated below. For biofilms used in CLSM, biochemical, Gtf activity, and mechanical stability assays, S. mutans UA159 and yidC mutant strains were grown in ultrafiltered (10-kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane; Prep/Scale, Millipore, MA) buffered tryptone-yeast extract broth (UFTYE; 2.5% tryptone and 1.5% yeast extract [pH 7.0]) with 1% glucose (37°C, 5% CO2) prior to use. For confocal SIM experiments, cells were grown in Todd-Hewitt yeast extract (THYE; 0.3% yeast extract). Where appropriate, 1 mg ml−1 spectinomycin (Spec) or 10 µg ml−1 erythromycin was added to broth or agar.

Construction of ΔyidC1 or ΔyidC2 mutant.

Allelic replacement was used to replace the yidC1 or yidC2 gene with a promoterless nonpolar antibiotic marker in parent strain S. mutans UA159, without disrupting expression of the surrounding genes, and allowed expression of the antibiotic marker from the endogenous yidC1 or yidC2 promoter. The sequence of primers used to construct the mutants are in Table 1. For the ΔyidC1::Spr (Smu.337) mutant strain, a 450-bp upstream DNA fragment was amplified by PCR with primers SP62F and SP62R-SOE, the aad9 gene for spectinomycin resistance was amplified by PCR from pDL278 (49) using SP63F-SOE and SP63R-SOE, and a 437-bp downstream DNA segment was amplified with primers SP64F-SOE and SP64R. PCR products were gel purified (QIAquick gel extraction kit; Qiagen). Primers with a splice overlap extension (SOE) designation contain 9-bp overlapping sequences with the adjacent primer to facilitate joining of fragments using the 5′- and 3′-terminal primers. SOE PCR was performed with 50 ng of each fragment and primers SP62F and SP64R for ΔyidC1::Spr mutant, as described in reference 25. The final PCR product was used to transform the parent S. mutans strain UA159, with selection on BHI-Spec agar plates. The ΔyidC2::Ermr knockout construct was made using the same approach, with primers SP56F and SP56R-SOE used to amplify a 382-bp upstream region, SP57F-SOE and SP57R-SOE to amplify the erythromycin resistance gene from pJL105, and SP58F-SOE and SP58R to amplify 393 bp downstream of yidC2. The three fragments were joined in an SOE PCR using SP56F and SP58R, followed by natural transformation into the parent S. mutans strain UA159 and selection on BHI-erythromycin (BHI-Erm) plates.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer name | Sequencea | Application |

|---|---|---|

| SP62F | GAGATTTTTGGCTTTTTCTCATTT | ΔyidC1::Spr |

| SP62R-SOE | CATAGTTGTGTGCTGCAACAGCTAATCCAA | ΔyidC1::Spr |

| SP63F-SOE | TTGCAGCACACAACTATGGATATAAAATAGGTA | ΔyidC1::Spr |

| SP63R-SOE | TTGTTCTCCGTTTCCACCATTTTTTCAATTTTT | ΔyidC1::Spr |

| SP64F-SOE | GGTGGAAACGGAGAACAAATCATGGTATTATT | ΔyidC1::Spr |

| SP64R | GCAGTGGCTGCCGATGTTTT | ΔyidC1::Spr |

| SP56F | CCAGAAGCACAAAGACAGCAAA | ΔyidC2::Ermr |

| SP56R-SOE | CACTCCTTCGACGATTAACAACCATTGACTTTA | ΔyidC2::Ermr |

| SP57F-SOE | GCTCTGTCTGAAGGAGTGATTACATGAACAAA | ΔyidC2::Ermr |

| SP57R-SOE | GAAGAACTCCCCTTTAGTAACGTGTAACTTTCCA | ΔyidC2::Ermr |

| SP58F-SOE | ACTAAAGGGGAGTTCTTCAACAAAACGTATTG | ΔyidC2::Ermr |

| SP58R | GACAGTGATGCTGTTGCTAAA | ΔyidC2::Ermr |

| pZX10F-YidC2F | CTGTTATCAACGGATCCACCTAA CCGCCATAAACTGCCAGGCATC | pXyl-yidC2 |

| pZX10R-YidC2R | GACGCTTGTAAATTTTTTTCACGATTA CCTCCTTTGATTTAAGTGAACAAGT | pXyl-yidC2 |

| YidC2F-pZX10F | ACTTGTTCACTTAAATCAAAGGAGGTA ATCGTGAAAAAAATTTACAAGCGTC | pXyl-yidC2 |

| YidC2R-pZX10R | GATGCCTGGCAGTTTATGGCGG TTAGGTGGATCCGTTGATAACAG | pXyl-yidC2 |

Underlining indicates the location of overlapping segments for splice overlap extension PCR or prolonged overlap extension PCR.

Construction of complemented yidC2 mutant, aconditional expression strain.

To generate a yidC2 conditional expression strain for complementation experiments, yidC2 was inserted into the pZX10 Xyl-S2 plasmid under the control of a xylose-inducible promoter (50). To generate the plasmid construct, the expression vector backbone pZX10 and the yidC2 gene were amplified by PCR with the pZX10F-yidC2F and pZX10R-yidC2R, and yidC2F-pZX10F and yidC2R-pZx10R primer pairs, respectively. Complementary ends between the two amplicons facilitated the generation of concatemers using prolonged overlap extension PCR (POE-PCR), as described in reference 51. The resulting POE-PCR mixture was used to directly transform UA159 by natural transformation, and transformants were selected on BHI containing spectinomycin generating a strain containing the resulting plasmid. The yidC2 gene was then deleted from the chromosome as described above (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Western blotting with anti-YidC2 C-terminal antibody as described in reference 25 was used to verify tunable expression in various media (Fig. S1B). For growth experiments where yidC2 expression was desired, 1% xylose was added to media along with spectinomycin in order to maintain the plasmid.

Microscopic analysis.

Gram stains were performed on overnight cultures grown in BM medium supplemented with 20 mM glucose (52), following the manufacturer’s protocol (Protocol Stabilized Gram stain set; Fisher Scientific). Cells were mounted on glass slides with glass coverslips using Depex Mounting media (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and visualized using a 100× oil emersion objective on an Olympus BX43. Images were taken using an Olympus DP72 camera and scale bars added using CellSense software (Olympus) or calibrated images in ImageJ (version 2.0.0).

Electron microscopy.

For SEM and TEM experiments, cells were grown overnight in 500 ml BM medium supplemented with 20 mM glucose (52). Cells were pelleted (3,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and washed 3 times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then fixed for 30 min in a buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (0.1 M phosphate buffer [pH 7.4] [PB] and 0.1 M sucrose) and washed 3 times in PB. The fixed samples were then processed by the Campus Microscopy & Imaging Facility (CMIF) at The Ohio State University using the following protocol. Cells were briefly suspended in warm 2% agarose, pelleted before the agar set, and chilled on ice for 10 min. Cells were postfixed for 1 h in 1% osmium tetroxide in PB, followed by 3 rinses for 5 min each in PB. Samples were dehydrated in successive 10-min exposures to increasing concentrations of ethanol, as follows: 50% ethanol, 70% ethanol, 80% ethanol, and then 5 min in 95% ethanol, followed by an additional 5 min in fresh 95% ethanol. The final dehydration step was performed in 100% ethanol (new bottle) with 3 changes within 15 min. The dehydrated samples were treated with propylene oxide for 10 min, followed by a 1-h treatment in 1:1 propylene oxide-resin, 1:2 propylene oxide-resin overnight, and 100% Epon resin, with 2 changes over 2 to 6 h. Samples were embedded in fresh Epon resin, polymerized overnight at 60°C, and sectioned into ultrathin sections (70 nm) on a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome using a Diatome diamond knife. Grids were poststained with 1% uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate buffers and then imaged on an FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit TEM, operating at 80 keV; micrographs were collected in the range of ×4,000 to ×100,000 magnification. The results shown are from representative images. The analyze feature in ImageJ (version 2.0.0) was used to measure cell wall thickness and cell diameter. Images were calibrated based on the number of pixels in the scale bar. For cell wall thickness, 3 separate measurements were averaged together for each cell, with a minimum of 9 cells measured per strain. For cell diameter, measurements were taken across the middle of each cell at the narrowest point. A minimum of 6 cells were compared for each strain. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post hoc test was used to determine significant differences between mutant and wild-type strains.

Superresolution SIM.

Cells were grown in THYE (0.3% yeast extract [pH 7.4]) medium overnight (ON) at 37°C. The following morning, the ON cultures were diluted 1:200 in fresh medium at either pH 7.4 or pH 5. Once cells reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.5, fluorescent cancomycin (2 µg ml−1) was added to the cultures, incubated for 10 min, and then washed twice in PBS. An aliquot of cells (∼5 µl) was transferred to an agarose pad (3% [wt/vol]) and covered with a precleaned cover slip (no. 1.5). Imaging was performed within 5 to 10 min after washing. Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) imaging was preformed as previously described (53, 54). In brief, images were acquired on a Zeiss ELYRA PS1 (pco.edge scientific complementary metal-oxide semiconductor [sCMOS] camera) with a final pixel size of 50 nm, equipped with a 100× 1.46-numerical-aperture (NA) Plan Apo oil immersion objective. Individual images were acquired with an acquisition time of 300 ms per image (a total of 15 images were acquired per SIM image reconstruction) and subsequently reconstructed from the raw data in the ZEN2012 software. All imaging was performed at room temperature (∼23 to 24°C). Reconstructed SIM images were transferred to ImageJ (Fiji) for analysis and figure preparation. The cell diameter determination was performed using ImageJ (Fiji), and line scans were manually drawn over the widest width of each measured cell, where 77 to 87 cells were measured for each strain. Statistical analysis was carried out in Origin 9 Pro, with two-tailed Student's t test showing a significant difference between the wild type (WT) and ΔyidC2 mutant (P < 0.0001). Graphs were made using Adobe illustrator.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

CLSM experiments were performed essentially as described in references 35 and 47. Briefly, S. mutans and yidC mutants biofilms were formed on saliva-coated hydroxyapatite (sHA) disc surfaces, as detailed previously. Hydroxyapatite discs (1.25 cm in diameter, surface area of 2.7 ± 0.2 cm2; Clarkson Chromatography Products, Inc., South Williamsport, PA) were coated with filter-sterilized clarified human whole saliva (47). Then, each sHA disc was inoculated with 105 CFU of actively growing S. mutans or yidC1 or yidC2 mutant cells per ml in UFTYE medium containing 1% (wt/vol) sucrose, and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 19 h. EPS was labeled using 1 μM Alexa Fluor 647-dextran conjugate (10 kDa, 647/668 nm; Molecular Probes, Inc.), while the bacterial cells were stained with 2.5 μM SYTO 9 (485/498 nm; Molecular Probes, Inc.). The imaging was performed using a multiphoton Leica SP5 confocal microscope with a 20× (numerical aperture, 1.00) water immersion objective. The excitation wavelength was 780 nm, and the emission wavelength filter for SYTO 9 was a 495/540 OlyMPFEC1 filter, while the filter for Alexa Fluor 647 was a HQ655/40M-2P filter. Confocal image stacks were generated by optical sectioning at each selected position, and the step size of z-series scanning was 2 μm (47). The Amira 5.4.1 software (Visage Imaging, San Diego, CA) was used to create 3D renderings of biofilm architecture. The total biomass of bacterial cells and EPS and the diameters of microcolonies were quantified and analyzed using COMSTAT 2.0 and ImageJ 1.44 (47). Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

Glucosyltransferase activity.

Extracellular Gtf activity produced by planktonic cultures of yidC mutants and the wild type was measured as described by Koo et al., with some modifications (55). Briefly, S. mutans UA159 and yidC mutants were grown in UFTYE medium containing 1% (wt/vol) glucose. Growth was assessed by measuring the OD600. Bacterial cells were harvested at the early exponential (OD600, 0.2) mid-exponential (OD600, 0.5), and stationary (OD600, 1.0) phases by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and supernatant fluids were collected for the analyses. Phenylmethylsufonyl fluoride (0.1 mM, final concentration) was added to the supernatant as a protease inhibitor, and the pH value was measured and adjusted to 6.8 if necessary. The Gtf activity in supernatants was measured in terms of incorporation of [14C]glucose from radiolabeled sucrose (New England Nuclear Research Products, Boston, MA) into glucans in 4 h at 37°C, as described elsewhere (56). One unit (U) of enzyme was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to incorporate 1 μmol glucose into glucan over a 4-h reaction period. The cell-free supernatant was mixed with ([14C]glucosyl)-sucrose substrate (0.2 µCi/ml; 200 mM sucrose, 40 µM dextran T-10, 0.02% sodium azide in adsorption buffer [50 mM KCl, 0.35 mM K2HPO4, 0.65 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgCl2·6H2O {pH 6.5}]) for 4 h at 37°C to allow glucan synthesis. Insoluble glucans were collected after centrifugation (13,400 × g, 4°C, 10 min) and washed three times with water. Soluble glucans were precipitated with ethanol (final concentration, 70%) for 18 h at −20°C. The amounts of radiolabeled insoluble and soluble glucans were determined by means of scintillation counting. Data were shown as the fold change in Gtf activity in comparison to the wild type. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Biochemical assays.

The biofilm was homogenized via water bath sonication, followed by probe sonication (30-s pulse at an output of 7 W, Branson sonifier 150; Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT). The homogenized biofilm suspension was centrifuged at 5,500 × g and 4°C for 10 min, and the pellet was washed twice with water. The pellet and all of the supernatants were retrieved, and the water-soluble and -insoluble EPS fractions in the biofilm were extracted and quantified via established colorimetric assays as detailed previously (57–59). Briefly, the supernatants were pooled, 3 volumes of cold ethanol were added, and the resulting precipitate was collected. The precipitate, or water-soluble polysaccharide, was collected by centrifugation, washed with ice-cold 75% (vol/vol) ethanol three times, and dried in a SpeedVac concentrator prior to the colorimetric assay. In parallel, the biofilm pellet, after washing, was dried and weighed to determine the dry weight biomass. The insoluble EPS was extracted using 1 N NaOH (1 mg of biofilm dry weight per 0.3 ml of 1 N NaOH), and the extract was precipitated with three volumes of cold ethanol and dried in a SpeedVac concentrator. The soluble and insoluble EPS were resuspended in water and NaOH, respectively, and the amount of polysaccharides was measured using the phenol-sulfuric method with glucose as a standard. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

Rheometry-indentation-displacement assay.

Biofilms were grown for 96 h in 35 by 10-mm Falcon petri dishes on hydroxyapatite discs (1.25 cm in diameter, surface area of 2.7 ± 0.2 cm2; Clarkson Chromatography Products, Inc., South Williamsport, PA) in TYE medium (2.5% tryptone, 1.5% yeast extract, 1% sucrose [pH 7.0]) with daily medium exchanges. Indentation/compression tests were performed using a Discovery hybrid rheometer-2 (HR-2) with a temperature-controlled Peltier plate (25°C) connected to a heat exchanger (TA Instruments). A normal force was applied using 8-mm Smart Swap geometry with an approach of 1 µm/s. The elastic modulus (E) of each biofilm was calculated based on the early linear part of the force-displacement curve, where the geometry first came into contact with the biofilm using the formula E = slope × (1 − v2)/2r (60), where r is 4 mm (radius of geometry) and the Poisson’s ratio (v) was assumed to be 0.5. The assay was repeated two times, and the results represent three biological replicates for each strain.

Mechanical stability of biofilm using a detachment assay.

The mechanical stabilities of biofilms formed by S. mutans and yidC mutants were compared using a custom-built device as described by Hwang et al. (38). Briefly, 43-h biofilms formed on sHA were placed in the disc holders of the device and then exposed to constant shear stress of 1.78 N/m2 for 10 min. The duration of 10 min of shearing was determined to have reached a steady state of biofilm removal based on our previous study (38). The amount of biofilm dry weight (biomass) before and after application of shear stress was determined, and the corresponding confocal images were obtained and analyzed. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Erin Gloag for her assistance with the rheometry experiments. Also, we thank Justin Merritt for sharing the conditional expression system, pZX10 Xyl-S2, used to make a complemented yidC2 mutant.

EM micrographs presented in this report were generated using the instruments and services at the Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility, The Ohio State University. This facility is supported in part by grant P30 CA016058, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. This work was supported by NIH NIDCR award DE023833 (to S.R.P.) and NIH NIDCR award DE008007 (to L.J.B.).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00396-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marsh PD. 2004. Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries Res 38:204–211. doi: 10.1159/000077756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakubovics NS. 2015. Intermicrobial interactions as a driver for community composition and stratification of oral biofilms. J Mol Biol 427:3662–3675. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loesche WJ. 1986. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev 50:353–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi N, Nyvad B. 2011. The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectives. J Dent Res 90:294–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen WH, Koo H. 2011. Biology of Streptococcus mutans-derived glucosyltransferases: role in extracellular matrix formation of cariogenic biofilms. Caries Res 45:69–86. doi: 10.1159/000324598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koo H, Falsetta ML, Klein MI. 2013. The exopolysaccharide matrix: a virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J Dent Res 92:1065–1073. doi: 10.1177/0022034513504218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Ohle C, Gieseke A, Nistico L, Decker EM, deBeer D, Stoodley P. 2010. Real-time microsensor measurement of local metabolic activities in ex vivo dental biofilms exposed to sucrose and treated with chlorhexidine. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:2326–2334. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02090-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh PD. 2003. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology 149:279–294. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneewind O, Missiakas DM. 2012. Protein secretion and surface display in Gram-positive bacteria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:1123–1139. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banas JA, Vickerman MM. 2003. Glucan-binding proteins of the oral streptococci. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 14:89–99. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.du Plessis DJF, Nouwen N, Driessen AJM. 2011. The Sec translocase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:851–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akopian D, Shen K, Zhang X, Shan S-O. 2013. Signal recognition particle: an essential protein-targeting machine. Annu Rev Biochem 82:693–721. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park E, Rapoport TA. 2012. Mechanisms of Sec61/SecY-mediated protein translocation across membranes. Annu Rev Biophys 41:21–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calo D, Eichler J. 2011. Crossing the membrane in Archaea, the third domain of life. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:885–891. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan J, Zweers JC, van Dijl JM, Dalbey RE. 2010. Protein transport across and into cell membranes in bacteria and archaea. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:179–199. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasona A, Crowley PJ, Levesque CM, Mair RW, Cvitkovitch DG, Bleiweis AS, Brady LJ. 2005. Streptococcal viability and diminished stress tolerance in mutants lacking the signal recognition particle pathway or YidC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:17466–17471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508778102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams ML, Crowley PJ, Hasona A, Brady LJ. 2014. YlxM is a newly identified accessory protein that influences the function of signal recognition particle pathway components in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 196:2043–2052. doi: 10.1128/JB.01465-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis NE, Brady LJ. 2015. Breaking the bacterial protein targeting and translocation model: oral organisms as a case in point. Mol Oral Microbiol 30:186–197. doi: 10.1111/omi.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosch JW, Vega LA, Beyer JM, Lin A, Caparon MG. 2008. The signal recognition particle pathway is required for virulence in Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun 76:2612–2619. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennon SW, Soman R, Zhu L, Dalbey RE. 2015. YidC/Alb3/Oxa1 family of insertases. J Biol Chem 290:14866–14874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.638171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalbey RE, Wang P, Kuhn A. 2011. Assembly of bacterial inner membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 80:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg R, Knüpffer L, Origi A, Asti R, Koch H-G. 2018. Co-translational protein targeting in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 365:5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalbey RE, Kuhn A, Zhu L, Kiefer D. 2014. The membrane insertase YidC. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Sousa Borges A, de Keyzer J, Driessen AJM, Scheffers D-J. 2015. The Escherichia coli membrane protein insertase YidC assists in the biogenesis of penicillin binding proteins. J Bacteriol 197:1444–1450. doi: 10.1128/JB.02556-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer SR, Crowley PJ, Oli MW, Ruelf MA, Michalek SM, Brady LJ. 2012. YidC1 and YidC2 are functionally distinct proteins involved in protein secretion, biofilm formation and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 158:1702–1712. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.059139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tjalsma H, Bron S, van Dijl JM. 2003. Complementary impact of paralogous Oxa1-like proteins of Bacillus subtilis on post-translocational stages in protein secretion. J Biol Chem 278:15622–15632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofbauer B, Vomacka J, Stahl M, Korotkov VS, Jennings MC, Wuest WM, Sieber SA. 2018. Dual inhibitor of Staphylococcus aureus virulence and biofilm attenuates expression of major toxins and adhesins. Biochemistry 57:1814–1820. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Y, Palmer SR, Hasona A, Nagamori S, Kaback HR, Dalbey RE, Brady LJ. 2008. Functional overlap but lack of complete cross-complementation of Streptococcus mutans and Escherichia coli YidC orthologs. J Bacteriol 190:2458–2469. doi: 10.1128/JB.01366-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saller MJ, Wu ZC, de Keyzer J, Driessen AJM. 2012. The YidC/Oxa1/Alb3 protein family: common principles and distinct features. Biol Chem 393:1279–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumazaki K, Chiba S, Takemoto M, Furukawa A, Nishiyama K-I, Sugano Y, Mori T, Dohmae N, Hirata K, Nakada-Nakura Y, Maturana AD, Tanaka Y, Mori H, Sugita Y, Arisaka F, Ito K, Ishitani R, Tsukazaki T, Nureki O. 2014. Structural basis of Sec-independent membrane protein insertion by YidC. Nature 509:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu ZC, de Keyzer J, Berrelkamp-Lahpor GA, Driessen AJM. 2013. Interaction of Streptococcus mutans YidC1 and YidC2 with translating and nontranslating ribosomes. J Bacteriol 195:4545–4551. doi: 10.1128/JB.00792-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shankar M, Mohapatra SS, Biswas S, Biswas I. 2015. Gene regulation by the LiaSR two-component system in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 10:e0128083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samuelson JC, Chen M, Jiang F, Moller I, Wiedmann M, Kuhn A, Phillips GJ, Dalbey RE. 2000. YidC mediates membrane protein insertion in bacteria. Nature 406:637–641. doi: 10.1038/35020586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein MI, Hwang G, Santos PHS, Campanella OH, Koo H. 2015. Streptococcus mutans-derived extracellular matrix in cariogenic oral biofilms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koo H, Xiao J, Klein MI, Jeon JG. 2010. Exopolysaccharides produced by Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferases modulate the establishment of microcolonies within multispecies biofilms. J Bacteriol 192:3024–3032. doi: 10.1128/JB.01649-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klapper I, Rupp CJ, Cargo R, Purvedorj B, Stoodley P. 2002. Viscoelastic fluid description of bacterial biofilm material properties. Biotechnol Bioeng 80:289–296. doi: 10.1002/bit.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinogradov AM, Winston M, Rupp CJ, Stoodley P. 2004. Rheology of biofilms formed from the dental plaque pathogen Streptococcus mutans. Biofilms 1:49–56. doi: 10.1017/S1479050503001078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang G, Klein MI, Koo H. 2014. Analysis of the mechanical stability and surface detachment of mature Streptococcus mutans biofilms by applying a range of external shear forces. Biofouling 30:1079–1091. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2014.969249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crowley PJ, Brady LJ. 2016. Evaluation of the effects of Streptococcus mutans chaperones and protein secretion machinery components on cell surface protein biogenesis, competence, and mutacin production. Mol Oral Microbiol 31:59–77. doi: 10.1111/omi.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang P, Kuhn A, Dalbey RE. 2010. Global change of gene expression and cell physiology in YidC-depleted Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 192:2193–2209. doi: 10.1128/JB.00484-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss DS, Chen JC, Ghigo JM, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 1999. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J Bacteriol 181:508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen LB, Angert ER, Setlow P. 1999. Septal localization of penicillin-binding protein 1 in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 181:3201–3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheffers D-J, Errington J. 2004. PBP1 is a component of the Bacillus subtilis cell division machinery. J Bacteriol 186:5153–5156. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.5153-5156.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen ZT, Bitoun JP, Liao S. 2015. PBP1a-deficiency causes major defects in cell division, growth and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 10:e0124319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanada N, Kuramitsu HK. 1989. Isolation and characterization of the Streptococcus mutans gtfD gene, coding for primer-dependent soluble glucan synthesis. Infect Immun 57:2079–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao J, Klein MI, Falsetta ML, Lu B, Delahunty CM, Yates JR, Heydorn A, Koo H. 2012. The exopolysaccharide matrix modulates the interaction between 3D architecture and virulence of a mixed-species oral biofilm. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002623. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon VD, Davis-Fields M, Kovach K, Rodesney CA. 2017. Biofilms and mechanics: a review of experimental techniques and findings. J Phys D Appl Phys 50:223002. doi: 10.1088/1361-6463/aa6b83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.LeBlanc DJ, Lee LN, Abu-Al-Jaibat A. 1992. Molecular, genetic, and functional analysis of the basic replicon of pVA380-1, a plasmid of oral streptococcal origin. Plasmid 28:130–145. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(92)90044-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie Z, Qi F, Merritt J. 2013. Development of a tunable wide-range gene induction system useful for the study of streptococcal toxin-antitoxin systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6375–6384. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02320-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie Z, Okinaga T, Qi F, Zhang Z, Merritt J. 2011. Cloning-independent and counterselectable markerless mutagenesis system in Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:8025–8033. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06362-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loo CY, Corliss DA, Ganeshkumar N. 2000. Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation: identification of genes that code for biofilm phenotypes. J Bacteriol 182:1374–1382. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.5.1374-1382.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Söderström B, Mirzadeh K, Toddo S, Heijne von G, Skoglund U, Daley DO. 2016. Coordinated disassembly of the divisome complex in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 101:425–438. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Söderström B, Chan H, Shilling PJ, Skoglund U, Daley DO. 2018. Spatial separation of FtsZ and FtsN during cell division. Mol Microbiol 107:387–401. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koo H, Schobel B, Scott-Anne K, Watson G, Bowen WH, Cury JA, Rosalen PL, Park YK. 2005. Apigenin and tt-farnesol with fluoride effects on S. mutans biofilms and dental caries. J Dent Res 84:1016–1020. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koo H, Vacca Smith AM, Bowen WH, Rosalen PL, Cury JA, Park YK. 2000. Effects of Apis mellifera propolis on the activities of streptococcal glucosyltransferases in solution and adsorbed onto saliva–coated hydroxyapatite. Caries Res 34:418–426. doi: 10.1159/000016617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koo H, Hayacibara MF, Schobel BD, Cury JA, Rosalen PL, Park YK, Vacca Smith AM, Bowen WH. 2003. Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans biofilm accumulation and polysaccharide production by apigenin and tt-farnesol. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:782–789. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aparecido Cury J, Seils J, Koo H. 2008. Isolation and purification of total RNA from Streptococcus mutans in suspension cultures and biofilms. Braz Oral Res 22:216–222. doi: 10.1590/S1806-83242008000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klein MI, DeBaz L, Agidi S, Lee H, Xie G, Lin AHM, Hamaker BR, Lemos JA, Koo H. 2010. Dynamics of Streptococcus mutans transcriptome in response to starch and sucrose during biofilm development. PLoS One 5:e13478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Timoshenko S, Goodier JN. 1951. Theory of elasticity, 2nd ed McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.