ABSTRACT

Nanomaterials have gained a rapid increase in use in a variety of applications that pertain to many aspects of human life. The majority of these innovations are centered on medical applications and a range of industrial and environmental uses ranging from electronics to environmental remediation. Despite the advantages of NPs, the knowledge of their toxicological behavior and their interactions with the cellular machinery that determines cell fate is extremely limited. This review is an attempt to summarize and increase our understanding of the mechanistic basis of nanomaterial interactions with the cellular machinery that governs cell fate and activity. We review the mechanisms of NP-induced necrosis, apoptosis and autophagy and potential implications of these pathways in nanomaterial-induced outcomes.

Abbreviations: Ag, silver; CdTe, cadmium telluride; CNTs, carbon nanotubes; EC, endothelial cell; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GO, graphene oxide; GSH, glutathione; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; NP, nanoparticle; PEI, polyethylenimine; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; QD, quantum dot; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SiO2, silicon dioxide; SPIONs, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles; SWCNT, single-walled carbon nanotubes; TiO2, titanium dioxide; USPION, ultra-small super paramagnetic iron oxide; ZnO, zinc oxide.

KEYWORDS: Apoptosis, autophagy, cell death, lysosome, nanoparticles; nanotoxicity, necrosis, stress

Introduction

The prefix ‘nano’ means dwarf in Greek, and the term ‘nanotechnology’ refers to advanced technologies on the nanometer scale that present potentials to revolutionize many aspects of human biology. Nanotechnology encompasses topics ranging from nanodevices, nanosensors and nanorobots to nanomedicines. Nanoparticles (NPs) are defined as particles with at least one dimension less than 100 nm. Nanomaterials demonstrate high surface-to-volume ratios, which renders unlimited surface modification and optical abilities [1–3]. Due to their unique physico-chemical characteristics, NPs have attracted huge attention in the field of nanomedicine. Advantages of NPs in this context include their ability to easily penetrate across cell barriers, preferential accumulation in specific organelles and cells, and theranostic (both therapy and diagnostic) properties, as well as their capacity for fine tuning [4,5]. Given these astonishing properties, NPs are under extensive investigation in order to utilize them as a carrier for genes or drugs, in imaging, for tissue engineering and even as single therapeutic agents to treat human diseases [6].

Despite these advantages, the interactions of NPs with living cells are complex and still far from fully understood [3]. NPs not only enter the cells at the site of deposition but can also reach distant organs through a variety of mechanisms [7]. NPs from many different compositions, such as metals, metal oxides, carbons, silica, and quantum dots show cytotoxic effects in different biological systems [3,8–11]. NP-induced cytotoxic effects correlate with NP composition, concentration, size, surface charge, surface area, functionalization, dispersion states and protein corona [11,12].

In this review, we discuss the interaction of NPs with cell fate pathways (necrosis/necroptosis, apoptosis, and autophagy) in order to provide a comprehensive state-of-the-art review on their eventual adverse and/or positive effects in human cells and on their therapeutic potentials in human diseases.

Cell death: why and how?

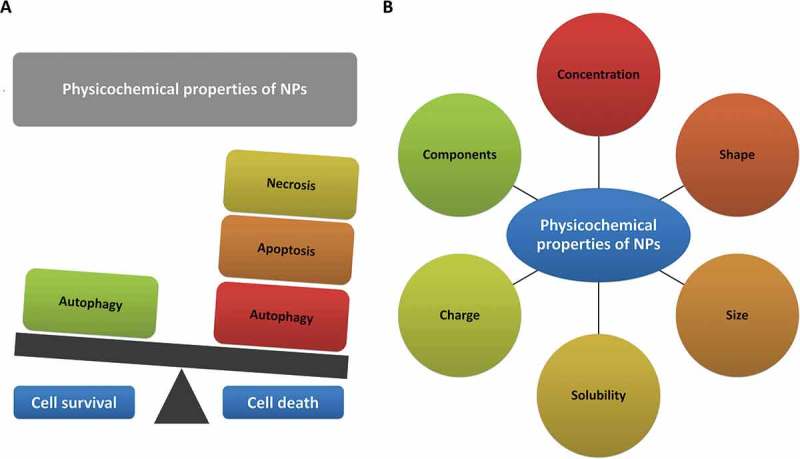

Since the advent of nanotechnology, the pathophysiological and possible cytotoxic effects of NPs are major concerns that have resulted in uncertainties about their benefits [13]. On the one hand, based on their doses and physico-chemical characteristics, NPs have the capability of producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) or otherwise initiating signaling pathways that in addition to regulating autophagy, can eventually modulate different cell fates, including necrosis, necroptosis, apoptosis, and mitotic catastrophe (Figure 1 and Tables 1–3) [4,6]. Thus, understanding nanotoxicity mechanisms is very important for the safe design of NP-based systems.

Figure 1.

NPs, based on their doses and physico-chemical characteristics, can modulate different cell fates including necrosis, apoptosis, and autophagy. (a) Nanoparticles can induce cell death or foster cell survival. (b) Physicochemical properties of nanoparticles affect cell fate.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characteristics of nanoparticles affect necrosis.

| Nanoparticles | Particle size | Shape | Charge | Dose | Exposure time | Cell lines/in vivo models | Major outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | 10–200 nm | 1–50 µg/ml | 4 h, 24 h | L-929 fibroblast cells | Necrosis and apoptosis. | [110] | ||

| Ag NPs | 15 nm | EC50: 8.75 µg/ml | 48 h | Mouse spermatogonial stem C18–4 cells | Reduction in mitochondrial function and finally necrosis. | [111] | ||

| Ag NPs | 7–20 nm | 6.25–60 µg/ml | 24 h | Human fibrosarcoma HT-1080 and skin/carcinoma A431 cells | Reduced cell viability, oxidative stress, necrosis. | [77] | ||

| Ag NPs | 7–20 nm | 25–100 µg/ml | 24 h | Primary mouse fibroblasts and liver cells | Oxidative stress and necrosis at high doses (100 μg/mL in primary fibroblasts and 500 μg/mL in primary liver cells). | [112] | ||

| Ag NPs | 30–50 nm | Spherical, multi-facetted or slightly elongated shapes. | 2.5–15 µg/ml | 24 h | A549 human lung carcinoma epithelial-like cell line | Increase in necrosis/late apoptosis | [113] | |

| PVP-coated Ag NPs | 69 ± 3 nm | Approximately spherical, multi-facetted, or slightly elongated shapes. | 0 to 7.5 µg/ml | 0–24 h | Human leukemia THP-1 cells | ROS-induced apoptosis. | [76] | |

| Au NPs | 1.4 and 15 nm | 100 mM | 24 h, 48 h | Human cervical cancer HeLa cells | Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and triggered cell death by necrosis. | [82] | ||

| Au NPs | 10–50 nm | 10- and 20-nm GNPs show spherical shape whereas the 50-nm GNPs show a hexagonal shape. | 50 or 100 µl | 3 or 7 days | Male Wistar-Kyoto rats | Glutathione depletion, ROS generation, and necrosis. | [114] | |

| Au NPs | 0.8–15 nm | 30 to 56 µM | 24 h, 48 h | Connective tissue fibroblasts, epithelial cells, macrophages, and melanoma cells | Rapid cell death by necrosis. | [83] | ||

| Au NPs | 1.5 nm | Positively charged, neutral, and negatively charged. | 10 µg/ml and the neutral at 25 µg/ml. | - | Human epidermal keratinocyte HaCaT cells | Charged NPs induce cell death through apoptosis whereas neutral NPs lead to necrosis. | [84] | |

| Fullerene/C60 | 100 nm | Spindle-like shape. | 0.25 and 1 μg/ml | 24 h | Rat glioma cell line C6 and the human glioma cell line U251 | Reactive oxygen species-mediated necrotic cell damage. | [74] | |

| Fullerene/C60 | 96.3 nm | Nano-C60 (0.25 μg/ml) or C60(OH)n (250 μg/ml) | 24 h | L929 mouse fibroblast cells | Oxidative stress followed by rapid necrotic cell death. | [115] | ||

| Fullerene/C60 | 291 and 282 nm | Net zero charge on the fullerol in all solvents. | 0–50 μM | 24 h | Human lens epithelial cells (HLE B-3) | Necrosis. | [116] | |

| 1 nm | >25 μM | 72 h | Human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELFs) | Necrosis is the dominant mechanism of death. | [117] | |||

| ZnO | 20 nm | 1, 5, 10, 40 or 80 m g/cm2 | 4 h, 24 h | Murine macrophage RAW 264.7. cells, Primary macrophages obtained from bone marrow of NCF1/p47 phox NADPH oxidase- and NFE2L2-deficient mice | Oxidative DNA damage followed with necrosis. | [107] | ||

| ZnS NPs | 80–120 nm | Symmetric, spherical. | Negative surface charge. | 25 and 50 μg/ml | 24 h | Human acute myeloid leukemia KG1a cells | Disruption of the mitochondrial membrane and ATP depletion followed by necrosis. | [118] |

| ZnO NPs | 40–100 nm | 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 μg/mL | 12 h, 24 h | SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma | Necrosis by LOX-mediated ROS production elevation. | [119] | ||

| ZnO NPs | <150 nm | 15, 30, 100 μg/mL | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | Human epidermal keratinocyte HaCaT cells and human cervical cancer HeLa cells | Acute cytoskeletal collapse that triggers necrosis. | [109] | ||

| Realgar quantum dots (RQDs) | 5.48 nm | 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 µg/ml | 48 h | Human endometrial cancer JEC cells | ER stress- or mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis and necrosis. | [120] | ||

| Ag(2)S QDs | 5.4 nm | Negative charge. | 6.25,12.5, 25, 50 and 100 µg/ml | 72 h | L929 mouse fibroblast cells | ROS-dependent apoptosis/necrosis. | [121] | |

| Cationic quantum dots | 16 and 9 nm | Cationic. | Up to 1.2 μM | 24 h | Human cervical cancer HeLa cells | Physical cell membrane rupture/necrosis that can lead to inflammation and subsequent cell death. | [122] | |

| Realgar quantum dots | 5.48 ± 1.09 nm | 20, 40 and 80 μg/ml | 6 h | Human hepatocellular HepG2 cells and human normal liver (L02) cells | Apoptosis and necrosis. | [123] | ||

| Si/SiO2 quantum dots | 6 and 8 nm | Spherical. | 25 and 200 μg/mL | 24–72 h | Lung fibroblast cells MRC-5 cell line | Apoptosis rate was much higher than the necrosis rate. | [124] | |

| CdTe quantum dots | 2–10 nm | Negative. | 0, 25, 50, 100, 200 nmol/L | 24 h | Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) and human cervical cancer HeLa cells | Mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) and necrosis. | [108] |

Table 3.

Physico-chemical characteristics of nanoparticles affect autophagy.

| Physiochemical properties |

Dose and time of exposure |

Signaling pathways/mechanism |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Size | Hydro-dynamic size | Shape | Charge/zeta potential | Functional groups | Dose | Time (h) |

Cell models | Upregulated | Downregulated | Autophagy flux or blockage | Ref |

| Ag NPs | 8–14 nm | Sphere | - | PVP | 8 µg/ml; dose dependent | 24 | Murine IL3-dependent pro-B cell line (Ba/F3 cells) | LC3-II, ROS | SQSTM1, p-MTOR | Flux | [314] | |

| 18 nm | 4–20 nm | - | - | - | 24 | Ovarian cancer cells | ROS, ATG5, ATG7 | ATG10, Vps30/Atg6, Atg3 | ? | [315] | ||

| 26.5 | 58.8 | Sphere | −12.9 ± 1.1 | PVP | 10 µg/ml | 24 | Cervical cancer cell line HeLa | LC3-II, PtdIns3K dependent | SQSTM1 | Flux | [316] | |

| 15 nm | 65.47 ± 1.0 | Sphere | −17.4 ± 0.92 | - | 100 µM | 24 | U-251 human glioblastoma cell line | LC3-II | SQSTM1 | Flux | [317] | |

| Au NPs | - | 43 ± 15 | Sphere | - | mPEG | 64.7 µg/ml | 24 | MCF-7 breast cancer cell line | ROS, LC3-II SQSTM1, alkalinization of lysosomes | - | Blockage | [318] |

| - | 31.57 | Sphere | −9.28 ± 1.32 | PEG/SV40 | 7.5 nM | 24 | Cervical cancer cell line HeLa | LC3-II | - | Eventually flux | [319] | |

| 5 | - | Sphere | −47.7 ± 10.6 | Citrate | 50 nM | 24 | Renal epithelial cell line HK-2 | LC3-II, BECN1, ROS | - | Eventually flux | [320] | |

| 20 | 22.1 | Sphere | −40.6 ± 2.1 | Citrate | 1 nM | 72 | Human fetal lung fibroblast (MRC-5) cells | LC3-II, ATG7, lipid hydroperoxides, ROS | - | Eventually flux | [283] | |

| Silica NPs | 5–15 nm | sphere | −32.6 to −35.1 mV | - | 50 and 100 µg/mL | 24 and 48 h | Human glioma LBC3 cell line | LC3-II, ATG5 | Eventually flux | [321] | ||

| 62 nm | 105 | sphere | 43 mV | - | 25, 50, 75 and 100 µg/mL | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | LC3-II, ROS | Eventually flux | [322] | ||

| 62.1 | Sphere | - | 50 and 100 µg/ml | 24 | HUVECs | LC3-II, iNOS, CRP, IL1B, and IL6 | eNOS, NO, p-AKT, p-MTOR | Eventually flux | [323] | |||

| 57.66 | 107.94 | Sphere | −30.33 | - | 50 µg/ml | 24 | HUVECs | LC3-II, SQSTM1, NFE2L2, ROS, p-MAPK/JNK and MAPK/p38. | p-MAPK/ERK, p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-MTOR | Blockage | [324] | |

| ZnO NPs | 20 | - | Sphere | - | - | 30 µg/ml | 12 | Human ovarian carcinoma cell line SKOV3 | LC3-II, ROS | - | Eventually flux | [242] |

| 50 | 278.8 | Sphere | −11.5 | - | 30 µg/ml | 24 | Lung carcinoma A549 cell line | LC3-II, SQSTM1 | - | Blockage | [325] | |

| 50 | 278.8 | Sphere | −11.5 | - | 2.5 μg/ml | 24 | Mouse macrophage | LC3-II, BECN1, ROS | NFE2L2, p-AKT, p-PI3K and p-MTOR | Flux | [270] | |

| 15.38 ± 1.47 nm (width) and 82.34 ± 14.23 | - | Rod shaped | - | - | 10 μg/ml | 24–72 | JB6 Cl 41-5a | BECN1, ATG5 and LC3-II, ROS | - | Eventually flux | [326] | |

| Graphene | Diameter: 56.6 ± 8.7 Height: 1.9 ± 0.8 |

- | Oval shaped | - | GQD | 200 μg/ml | 20 | Malignant glioblastoma cell line U251 | LC3-II, ROS | SQSTM1 | Flux | [280] |

| 1.0–1.2 | 350 | Sheet | - | GO | 100 μg/ml | 24 | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | LC3-II, BECN1, IL2, IL10, IFNG and TNF | - | Eventually flux | [269] | |

| 1.5–5.5 | - | Multi-layer sheets | - | GQD | 100–200 μg/ml | 24 | Human monocytic cell line THP-1 | BECN1, LC3-II, BAX, BAD, CASP3, CASP9, p-MAPK and p-RELA, ROS | BCL2 | Eventually flux | [327] | |

| 65.5 ± 16.3 | - | Sheet | - | GO | 25 μg/mL | 12 | HUVECs | BECN1, LC3-II, | SQSTM1 | Flux | [328] | |

| Fullerene/C60 | - | - | Sphere | - | PEG, | 10 μM | 24 | Neuro-2A | LC3-II, p-AMPK | ROS, BCL2 | Eventually flux | [284] |

| - | - | Sphere | - | PTX | 10 μM | 24 | Neuro-2A | LC3-II | ROS, BCL2 | Eventually flux | [284] | |

| 7.1 | - | Sphere | C60(OH) | 100 μg/ml | 24 | HUVECs | LC3-II, LDH | cleavage of CASP3, PARP | Eventually flux | [330] | ||

| 20–100 | - | Sphere | - | - | 0.5 μg/ml | 24 | Cervical cancer cell line HeLa, primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts | LC3-II, acidic vesicles, ATG5 | - | Eventually flux | [274] | |

| Carbon nanotubes | 1–2 | - | Tube | - | carboxyl | 0.05 μg/ml | 24 | Primary glial cells | LC3-II | p-MTOR, p-ULK1, SQSTM1 | Flux | [331] |

| 1–2 | - | Tube | - | COOH | 1 mg/ml | 24 | Lung carcinoma A549 cell line | LC3-II | p-MTOR, p-AKT | Eventually flux | [227] | |

| Diameter: 10–20 nm Length: 2 μm |

- | Multi-wall | - | - | 20 mg/kg/day | 14 days | Rat hippocampal | LC3-II, BECN1 | GRIN2B/NR2B | Flux | ||

On the other hand, there is emerging evidence that cytotoxic potentials of NPs might be exploited in the treatment of multiple diseases and disorders, because dysregulation of cell death pathways is a common feature of cancer, neurodegenerative and neurological diseases [14,15] and thus cell death modulatory effects of NPs may have therapeutic value [6,16]. Apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis and autophagy, are the focus of current research for new therapeutic pathway discovery in human diseases.

Regulated cell death pathways

Necrosis

Necrosis has long been considered to be the result of nonspecific cell injury resulting from trauma. Accordingly, it was viewed as being primarily accidental and an uncontrolled type of cell death that was not driven by specific signaling events. Various pathological conditions, such as trauma, exposure to toxins, ischemia, viral or bacterial infection and neurodegenerative disorders can induce necrotic cell death.

There is initially a sublethal phase in the pathogenesis of cell injury from which a cell can recover or, alternatively, cells may pass a ‘point of no return’ (permeabilization of the mitochondrial membranes) [17]. Morphologically, the cell displays a series of changes in the early (reversible) stage that includes ‘change of hydropic’, ‘degeneration of feathery’, ‘cloudy swelling’ or ‘vacuolar degeneration’ [9,14]. The point of no return is associated with a crucial separation between the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes followed by the irreversible loss of oxidative phosphorylation capacity [17]. Finally, in the late stages of necrosis, the cytoplasm loses contents and takes on a homogeneous eosinophilic appearance (as with ground glass), irregularities in the membrane of cytoplasmic organelles, mitochondrial swelling, increased matrix density, the formation of vacuoles, and the deposit of calcium phosphates. At the nuclear level, chromatin patterns are seen with pyknosis (chromatic condensation), karyorrhexis (nuclear fragmentation) and karyolysis (complete chromatin disruption) [18,19].

Necroptosis

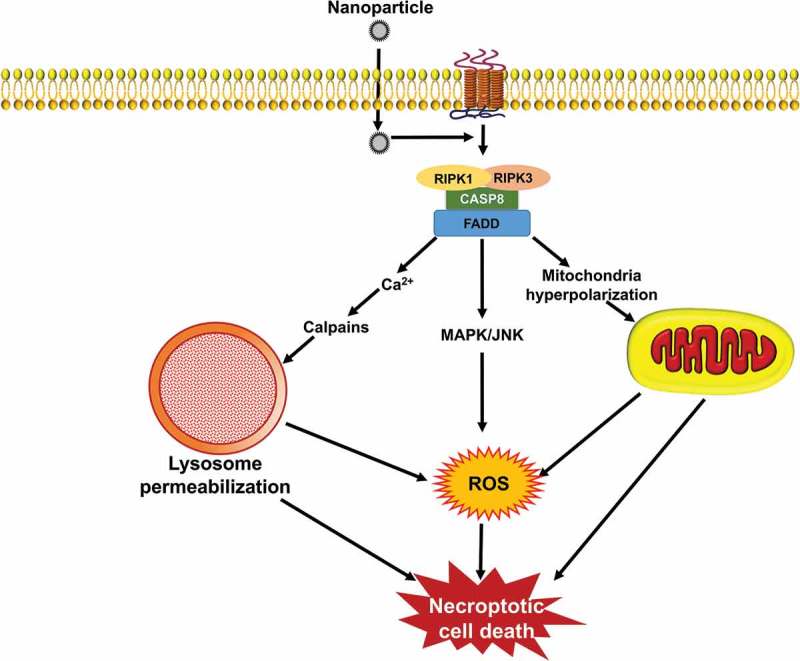

Recent research has revealed the existence of caspase-independent cell death pathways that occur in response to a wide range of stimuli, and are initiated as a result of specific signaling events [20]. In this context, regulated necrosis (necroptosis) is a complex process that is not triggered by one signaling cascade but rather is caused by the interactions resulting from the activation of several signaling pathways; in turn, these various pathways may be provoked by a wide range of stimuli (Figure 2). The term necroptosis is one form of necrosis that involves death receptor activation and that can be inhibited by blocking the kinase activity of RIPK1 (receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 1) [21,22]. In other words, necroptosis is a regulated process of cell death that involves ligand binding to TNF (tumor necrosis factor) death domain receptors (Figure 2). A common element of these receptor systems are proteins containing a RIPK homology interaction motif that recruits and activates RIPK3, leading to the activation of MLKL (mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase). With regard to the TNF family members, the initiator is RIPK1; TICAM1/TRFI plays this role for TLR3 (toll like receptor 3)-TLR4, whereas for ZBP1/DAI (Z-DNA binding protein 1), there is a RIPK homology interaction motif domain within the cytosolic sensor [23]. Entry into necroptosis can occur as part of many human pathologies ranging from viral infections to neuronal excitotoxicity, which lead to neurological disorders such as Huntington, Parkinson, and Alzheimer diseases [24]. The same ligands that can activate apoptosis including TNF/TNFα, FASLG/FasL, and TNFSF10/TRAIL (TNF superfamily member 10), can induce necroptosis [25], typically through the action of RIPK1 and RIPK3 [26]. RIPK3 interacts with and modulates RIPK1 kinase activity; RIPK1 in the context of a RIPK1-RIPK3 complex (necrosome) activates RIPK3, which in turn activates MLKL to trigger necroptosis. A wide range of necrotic mediators are activated through RIP1 kinase activity. In other cases, the same mediators can be activated by the triggering of TLR3, TLR4 and NLRP33 or by DNA damage [27].

Figure 2.

Signaling pathways that induce necroptosis. During necroptosis, different stimuli are sensed by the cell receptor apoptotic signaling pathway including, TNF/TNFα, FASLG/FasL, and TNFSF10/TRAIL that subsequently lead to the activation of RIPK1 and RIPK3 kinases. The process is followed through different signaling pathways, such as ROS generation, mitochondrial hyperpolarization, lysosomal impairment, and finally ends up with signs of necrotic cell death. NPs can induce necroptosis by stimulation of DNA damage and organelle dysfunctions as well as ROS production.

Apoptosis

The concept of apoptosis was first introduced to describe a morphologically distinct type of cell death that occurs in hepatocytes under physiological conditions [28,29]. Morphological signs of this type of cell death are described as membrane blebbing, cell shrinking, chromatin condensation and inter-nucleosomal DNA fragmentation, and formation of small vesicles named apoptotic bodies (Figure 3) [30,31]. In particular, a plasma membrane phosphatidylserine flip-flop from the inner layer to the outer side represents the signal that is detected by macrophages for engulfing apoptotic cells [29,32].

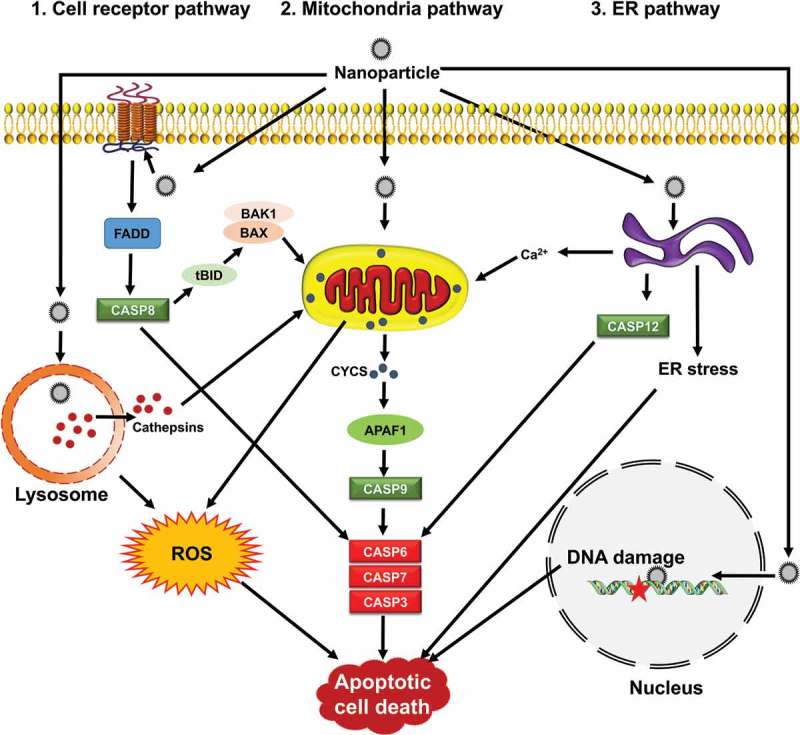

Figure 3.

Signaling pathways by which NPs induce apoptosis. Apoptosis is mediated through 3 main apoptotic pathways including cell receptor, mitochondria and ER, that converge upon activating caspases. Mitochondria are central during apoptosis and can act as amplifiers of the cell receptor pathway through CASP8-mediated BID clevage (truncated BID, tBID) and BAX or BAK1 activation. NPs can induce apoptosis via organelle dysfunction, ROS generation, ER stress and DNA damage.

Mechanism(s) of apoptosis in mammalian cells

Apoptosis occurs by 3 distinct pathways, involving death receptors, mitochondria, or the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 3) [29–34]. The activation of effector cysteinyl aspartate proteases (caspases), including CASP8 (caspase 8), CASP9, and CASP12 lead in turn to executor enzymes CASP3, CASP6 and CASP7 [35]. All morphological and biochemical changes related to apoptosis are mediated by these caspases.

In the death receptor or extrinsic apoptotic pathway, the superfamily of death receptor transmembrane proteins, including TNFRSF1A/TNFR1 (TNF receptor superfamily member 1A), FAS/CD95 (Fas cell surface death receptor), TNFRSF10A/TRAILR-1 (TNF receptor superfamily member 10a) and TNFRSF10B/TRAIL-R2 mediate the death signaling. Upon ligand binding, trimerization and clustering of receptors occurs to recruit adapter proteins such as FADD (Fas associated via death domain) and facilitates their binding to proCASP8 to form the death-inducing signaling complex/DISC [30–32,34]. Autocatalytic activation of CASP8 leads to cleavage and activation of CASP3, resulting in initiating the execution phase of apoptosis (Figure 3).

The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis is initiated by mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, various types of oxidative stress including hypoxia, DNA damage, and growth-factor deprivation [36]. Various members of the BCL2 superfamily of proteins can control mitochondrial integrity. These proteins are classified as pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic. BAX, BID, BAK1, BAD, PMAIP1/Noxa, and BBC3/Puma are members of the pro-apoptotic family, and BCL2, BCL2L1/Bcl-xl, MCL1, and BCL2A1 are members of the anti-apoptotic family proteins [37]. Pro-apoptotic BAX and BAK1 dimerize, and insert into the outer mitochondrial membrane, triggering the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Following mitochondrial permeabilization, CYCS (cytochrome c, somatic), is released into the cytosol, where it binds to APAF1 (apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1) that starts the formation of the apoptosome [38]. The apoptosome aids in the recruitment and activation of CASP9, which subsequently activates the downstream caspases CASP3, CASP6, and CASP7, and ultimately leads to apoptosis [30,31,34,39].

The third pathway of apoptosis is activated by various injuries from ER stressors. To cope with the ER stress, an adaptive response—the unfolded protein response (UPR)—is activated, and if the stress cannot be resolved the UPR leads to apoptosis [33,34,40]. It is thought that ER-induced apoptosis is mediated through activation of CASP12 in rodents (Figure 3). The human homolog of CASP12 was silenced during evolution and CASP4 may fulfill its function. ER-resident BCL2-family proteins regulate apoptosis through either direct or indirect (ER Ca2+ signaling) pathways [33,34].

Induction of apoptosis

It has become evident that there is complex and close crosstalk between different apoptotic pathways. For example, the extrinsic pathway can activate the mitochondrial pathway, and alternatively the cell death receptor pathway may active the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. This amplification loop occurs by the CASP8-mediated cleavage of BID, a pro-apoptotic BCL2 family protein [41]. Also, recent evidence suggest that BBC3/Puma and PMAIP1/Noxa both contribute to ER-mediated apoptosis via crosstalk with the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway [32,40].

A wide variety of stimuli can induce apoptosis [42,43]. These include different physico-chemical stresses such as chemicals, DNA damaging agents, removal of nutrients, free radical-generating compounds (e.g., H2O2), oxygen, certain growth factors, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, in addition to normal physiological processes such as development and aging [43–49]. Some chemicals play a role in activating pro-apoptotic BCL2 members such as BAX or BAK1 [41,50–52]. ROS—including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), free hydroxyl radicals (OH•), superoxide anions (O2•-), and nitric oxide (NO•), as well as new species produced by combinations of ROS (i.e., NO• and O2•-)—also have a major role in this process [53–57]. The particular response depends on the specific stimuli, which will in turn result in the production of different ROS species [58].

Autophagy

Autophagy definition and classification

Autophagy is primarily an adaptive process in cells, serving a cytoprotective function with the goal of survival under conditions of nutrient starvation and ATP deficiency. There are 2 fundamental types of autophagy, selective and nonselective; the selective process can be further categorized based on the cargo and mechanism of sequestration. Briefly, macroautophagy is the best characterized and perhaps the primary autophagic pathway (Figure 4). In this process, cytoplasmic cargos are sequestered through the action of a phagophore, which expands and matures to form a double-membrane vesicle (autophagosome). The autophagosome may fuse with an endosome and ultimately with a lysosome (or the vacuole in yeast or plants) to form an autolysosome. In microautophagy the cargo is directly engulfed by protrusion and/or septation of the lysosome/vacuole membrane. Macroautophagy in particular can be nonselective, but it can also be highly selective, whereas microautophagy has been characterized primarily as a selective process. The selectivity of macroautophagy depends on receptor proteins that typically bind ligands on the target, or are integral within the target membrane. A scaffold or adaptor then links the receptor with the autophagic machinery, usually via interaction with an Atg8-family protein, providing a physical connection with the phagophore. The type of sequestered cargo is used as the basis for naming the different types of selective autophagy, such as mitophagy and pexophagy for the selective autophagic degradation of mitochondria and peroxisomes, respectively. There are several models for mitophagy in mammalian cells involving different receptor proteins including BNIP3, BNIP3L/NIX, FUNDC1 and PRKN/PARK2/Parkin, depending on the stress condition and cell type [59]. There are also distinct types of selective autophagy that use protein machinery that does not overlap with that used for macroautophagy or microautophagy. One example of such a process is chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). During CMA, which is induced as a secondary starvation response after macroautophagy, cytosolic proteins with a particular recognition motif bind the HSPA8/HSC70 chaperone leading to unfolding (which is one significant distinction relative to macroautophagy). The unfolded substrates are translocated directly across the lysosome surface through a channel formed by LAMP2A (lysosomal associated membrane protein 2A) in a process that involves lumenal HSPA8; the substrate protein is subsequently degraded [60]. The remainder of this review focuses on macroautophagy, which we refer to as autophagy.

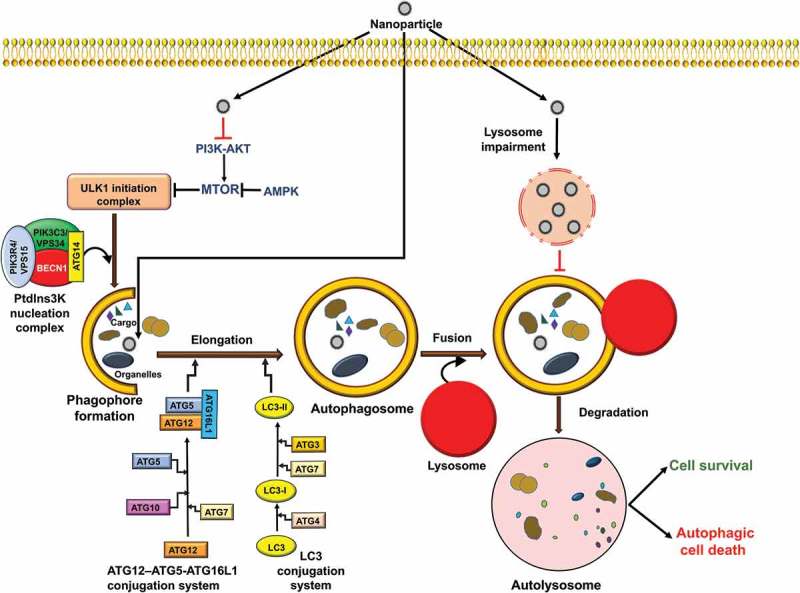

Figure 4.

Autophagy signaling pathways induced by NPs. During autophagy, specific intracellular cargo is sequestered by phagophores. Autophagy is initiated by the activation of ULK1 and subsequent induction of a nucleation complex, including the class III PtdIns3K. Maturation and elongation require conjugation of ATG12 to ATG5, and of Atg8-family proteins including LC3 to phosphatidylethanolamine. The completed phagophore forms an autophagosome; subsequent fusion with the lysosome, releases its contents into the lumen where the cargo is degraded and the resulting macromolecules are released back into the cytoplasm. Autophagy induction may lead to cell survival or cell death, depending on the cell content or type of stimuli. NPs can induce autophagic cell death through modulation of the MTOR pathway or may trigger autophagy blockage via lysosomal impairment.

Molecular signaling pathways towards autophagy

There are various molecular signaling pathways that regulate the induction and magnitude of autophagy. Some of the principle players include MTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase), which is the primary negative regulator of autophagy, and 2 autophagy-promoting kinases, 5ʹ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and the class III phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PtdIns3K) (Figure 4). Based in large part on the data from yeast, a general model for autophagy involves a cascade starting with one or more phagophore assembly sites (i.e., nucleation sites for the phagophore membrane) that involve the recruitment of an initiation complex consisting of ULK1, ATG13, ATG101 and RB1CC1/FIP200 and the PtdIns3K complex (BECN1, PIK3C3/VPS34, PIK3R4/VPS15/p150, ATG14 and NRBF2) [61]. Following the nucleation stage, which is still not well understood, the cascade leads to phagophore expansion and autophagosome formation; the expansion process is relatively unique and provides tremendous flexibility with regard to cargo capacity. The expansion and maturation stage are traditionally thought to involve 2 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems comprised of ATG12–ATG5-ATG16L1, an Atg8 family protein (an LC3 or GABARAP isoform) and the processing, activating or conjugating enzymes ATG4, ATG7, ATG3 and ATG10 (Figure 4). Recent work suggests that in mammalian cells these components may be involved in a late stage of autophagy [62]. The completed autophagosome may fuse with an endosome to form an amphisome, and either compartment then fuses with a lysosome. The amphisome is a single-membrane compartment, whereas if a double-membrane autophagosome fuses directly with the lysosome the inner membrane is subsequently degraded [63–65]. The cargo is broken down by hydrolases and the products are released into the cytosol through permeases [66]. In mammalian cells transport of an autophagosome towards a lysosome occurs via microtubules and the motor protein dynein [67,68].

In other words, during starvation and other conditions that induce autophagy such as stress, infection, development and differentiation, the autophagy cascade will start in part by the activation of AMPK, which will phosphorylate components of the ULK1 kinase and PtdIns3K complexes, and the inhibition of MTOR (which otherwise phosphorylates these components at inhibitory sites); however, other mechanisms in addition to those involving AMPK and MTOR can play a role. One important link between autophagy and apoptosis is BCL2, an anti-apoptotic protein that inhibits the function of BECN1 in autophagy. Under short-term stress conditions MAPK8/JNK1 phosphorylation of BCL2 causes its dissociation from BECN1, allowing activation of the PtdIns3K and progression of autophagy; long-term phosphorylation may cause additional inactivation of BCL2 leading to apoptosis [69].

Cell fates triggered by NPs

Overall, structural and physicochemical properties of NPs (Tables 1, 2 and 3) can influence the modalities of cell death that are induced by them. Although the mechanisms of toxicity of NPs based on surface charge, crystallinity, ligand specificity, and surface chemistry, are complex, much research is underway to determine properties and functional groups that can have an influence on cellular outcomes and biological responses of NPs. In most cases, the cytotoxic potential of NPs can be dictated by their crystal structure [70], but also by shape, size, surface reactivity, composition of chemical, surface charge, presence of transition metals [71], nano-topography and surface roughness [72]. Therefore, in order to more safely design and manufacture NPs, it is necessary to ensure extensive characterization of their physico-chemical properties [73,74].

Table 2.

Physico-chemical characteristics of nanoparticles affect apoptosis.

| NPs | Size | Shape | Functional groups | Dose | Time of exposure | Cell model | Major outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | 5.56 nm | 100, 200, and 400 ppm | 10 days | Rat Hippocampus | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [173] | ||

| 18 nm | 11.0 μg/ml | 24 h | Baby hamster kidney BHK-21 cell line and human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cell line | Upregulation of BAX, BAD, BAK1, TP53, and MYC. Downregulation of BCL2 and BCL2L1. | [136] | |||

| 5 to 10 nm | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 μg/ml | 1.0, 7.0, 9.5, 12.8 and 24.5 at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h | Human Chang liver cells | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [174] | |||

| 59 nm | 0.9–7.4 μg/mL | 24 h | Human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cell line | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [175] | |||

| 20 to 100 nm | 50 to 200 μM | 24, 48 and 72 h | Human colon cancer HCT116 cell line | Upregulation of TP53 and CDKN1A/p21. | [176] | |||

| Ag-CS NCs (chitosan) | 24 μg/ml | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cell line | Downregulation of BCL2 | [177] | ||||

| 1–100 nm | 100 μg/ml | Up to 72 h | NIH3T3 fibroblast cells | ROS production and MAPK/JNK activation. | [178] | |||

| 1–100 nm | 50 μg/ml | Up to 72 h | Mouse embryonic fibroblast NIH3T3 cell line | Induced release of CYCS into the cytosol, translocation of BAX to mitochondria and decreased BCL2 expression. | [137] | |||

| Au NPs | 200 µg/ml | 24 h | Human breast epithelial MCF-7 cells | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [179] | |||

| 20.52 nm | Plant extracts of Zataria multiflora | 0–400 μg/ml) | 48 h | Human cervical cancer HeLa cells and normal BMSC cells | [180] | |||

| AuNP20 was 18.6 nm and AuNP70 was 67.5 nm | 0 to 100 μg/ml | 24 h | Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) | [181] | ||||

| 13 nm | GNPs (10 μM), BSO (0.5 mM) or GNPs (10 μM) +BSO (0.5 mM) | 48 h | Lung carcinoma A549 cell line | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [92] | |||

| 8 nm and 37 nm | 50 nM | 24, 48 or 72 h | Human liver HL7702 cells | Upregulation of BAX, CYCS. | [182] | |||

| 1–20 nm | Abutilon indicum leaf powder | 180, 360, 540 and 720 μg/ml | 24, 48 h | Human colon carcinoma HT-29 and HaCaT keratinocytes | Expression of LMNA and PARP. | [183] | ||

| size <20 nm | 100 ng–1 μg/ml | 24 h | C2C12 myoblasts | [184] | ||||

| Carbon Nanotubes | 400–1000 m2/g Length: 0.1–1 µm Width: 0.8–1.2 nm |

SWCNT | 0–8.34 µg/cm2 | 48 h | Non-tumorigenic human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B | [185] | ||

| 450 nm | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) MWCNT-PEG |

5, 10, 50 µg/ml | 1 h followed by laser irradiation (3 min, 808 nm, 2W/cm2 | Human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells (PANC-1) |

[186] | |||

| MWCNT: L: 24 ± 12 µm D: 20 ± 7 nm AT-MWCNT: L: 10 ± 6 µm D: 20 ± 9 nm |

MWCNT Acid-treated MWCNTs (AT-MWCNT) |

25–100 µg/ml | 48 h | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | ROS production. | [187] | ||

| Acid-MWCNT L: 0.3–0.6 µm D: 10–20 nm Taurine- L: 0.3–0.6 µm D: 10–20 nm |

Acid-MWCNTs Taurine MWCNTs (tau-MWCNTs) |

0, 5, 20, 40, and 80 µg/ml for 12 or 24 h | 12, 48 h | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | ROS production. | [188] | ||

| SWCNTs | 0.125–10 µg/ml | 24, 48 h | Normal rat kidney epithelial cells (NRK-52E) | Elevated protein levels for TP53 and CDKN1A. Arrest at G0/G1 phase, CDK2, CDK6, p-RB1. |

[189] | |||

| L: 401nm | MWCNT | 0.5–100 µg/ml | 6–72 h | Lung carcinoma A549 cell line | ROS production. Upregulation of TP53, CDKN1A, BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. |

[190] | ||

| MWCNT | 5 µg/ml | 12, 24 h | Rat lung epithelial cells | ATP production. Cytochrome-c oxidase and NFKB activation. |

[191] | |||

| L: 12 µm D: 15 nm |

MWCNTs-COOH | 40, 200, 400 μg/ml | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | Normal human dermal fibroblast cells | DNA damage. | [192] | ||

| MWCNTs | 0.5–10 μg/ml | Rat lung epithelial cells | ROS production. | [193] | ||||

| L: 0.5–2 µm D: 20–50 nm |

MWCNT | 0, 1, 10 or 100 µg | Rat (in vivo) | [194] | ||||

| L: 1–5 µm D: 20–40 nm |

MWCNT | 1 and 10 ng/cell | 24–12 h | T lymphocytes from healthy human | [195] | |||

| CuO | 22 nm | 10 µg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Upregulation of TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [140] | ||

| 20 nm | 2, 5, 10, and 25 µg/ml | 24 h | Chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cell line | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [130] | |||

| 15 nm | Copper ferrite NP | 5, 25 and 100 μg/ml | 24 h | Human breast cancer MCF-7 cells | [197] | |||

| 35 nm | 50–100 μg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 cells and lung carcinoma A549 cell line | [198] | ||||

| 60–80 nm | up to 4.5 μg/ml | 18 h | A375 human melanoma cell line | [199] | ||||

| Fullerene/C60 | 96 nm in PBS, 142 nm in DMEM |

Polyhydroxylated (fullerenols, C 60[OH]n) |

10–200 µM | 48, 72 h | Lung carcinoma A549 cell line | Not cytotoxic. Antioxidant through increase in NFE2L2. |

[200] | |

| C60-bis (N,N-dimethylpyrrolidinium iodide) | HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cell line | [201] | ||||||

| hydrodynamic sizes (radius) were 4.7 and 40.1 nm | Hydroxylated fullerene (fullerol) | 1, 10 and 100 µg/ml | Caenorhabditis elegans | [202] | ||||

| 150 nm | C60 (C[COOH] 2)2 |

Cerebral microvessel endothelial cells | p-MAPK/JNK, activation of AP-1 Decrease in apoptosis. |

[203] | ||||

| Graphene | GO: 10 nm ~ 1 nm thickness |

nanosheets | [204] | |||||

| Thickness: GO: 0.6 nm rGO: 0.9 nm Size: GO: 219 nm rGO: 122.4 nm |

nanosheets | 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml | 6, 12, 24, 48 h | Phaeochromocytoma (PC12) cells | Cell cycle arrest. | [205] | ||

| 3.125–100 µg/ml | 24, 48 h | Osteosarcoma cell lines, HOS and KHOS | [206] | |||||

| GQDs 1.5–5.5 nm (mean: 3.03 nm) |

1–200 µg/ml | 24, 48 h | THP-1 human monocytic cell line | ROS production. Increase in BAX, BAD, BECN1, and LC3-I/II. Downregulation of BCL2. |

[207] | |||

| Quantum Dots | 2.2 ± 0.25 nm 3.5 ± 0.49 nm |

CdTe QDs | 80 μg/ml | 24 h | L929 mouse fibroblasts | ROS production. Upregulation of MAPK/p38, MAPK/JNK, MAPK/ERK. |

[208] | |

| 2.2 nm CdSe QDs 2.2 nm CdTe QDs 3.5 nm CdTe QDs |

5.85–150 μg/ml | 24 h | L929 mouse fibroblasts | Oxidative stress. Genotoxicity. |

[209] | |||

| Realgar QD: 5.48 ± 1.09 nm |

7.5–60 µg/ml | 6 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells, L02 normal liver cell line | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [210] | |||

| 7.3 ± 1.2 nm | CdTe-QDs | 0.001–10 µg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | ROS production. Upregulation of MAPK/p38, MAPK/ERK, MAPK/JNK. |

[211] | ||

| 6.0 ± 0.5-nm | CuO QDs | 5–20 µg/ml | 8, 16, 24 h | C2C12 myoblasts | [212] | |||

| 2.0 nm to 2.5 nm | Spherical core/shell | CdSe QDs | 0.6–9.6 µg/ml | Mouse epidermal cells (JB6 cells) |

Upregulation of AIF. G1/S arrest. |

[213] | ||

| Realgar QDs: 5.48 ± 1.09 nm |

Realgar (As4S4) | 10–160 µg/ml | 48 h | Human endometrial cancer JEC cells | Upregulation of HSPA5/HSPA5 (gene/protein). ER stress. |

[120] | ||

| 3.5 nm | CdSe QD | 150 and 300 nM | IMR-32 human neuroblastoma cell line | Upregulation of BAX and p-MAPK/JNK. Downregulation of BCL2, p-MAPK/ERK, HSP90, RAF1, RAS. |

[215] | |||

| Iron Oxide | 25 nm | for 24 h | 25, 50 and 100 g/ml | A431 human epidermoid carcinoma and lung carcinoma A549 cell line | [216] | |||

| 21.5 nm | DSPE-PEG micelles | 2, 3, 7 and 14 days | 5 mg Fe/kg bw and 15 mg Fe/kg bw | Rat lung tissue | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [217] | ||

| 41.5 nm | Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (M-FeNPs) | 24 h | 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/ml | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | Upregulation of BCL2, SQSTM1, LC3, ERN1, p-ERN1, DDIT3, and SOD2. Downregulation of BECN1 and BAX. |

[218] | ||

| Cold atmospheric plasma and iron nanoparticles | 24 h | 1.48–750 ppm | Human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) | Upregulation of BAX. Downregulation of BCL2. | [219] | |||

| 24, 48 h | 10, 30, 60, and 120 μg/ml | Human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) | [220] | |||||

| Fe3O4 | 24 h | 100 μg/ml | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells and lung carcinoma A549 cell line | Upregulation of TP53. | [221] | |||

| SeNPs | Ch-SeNPs 40–60 nm | Spherical | 0.1–5 mg/l | 72h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Slow migration rate. No apoptosis induction. Cell cycle arrest at S-G2/M phase. Inhibition of CDK1. |

[222] | |

| Tf-SeNPs | 72h | MCF-7 breast cancer cells, Human hepatoma HepG2 cells, A375 human melanoma cell line, HUVECs |

ROS production. | [223] | ||||

| Spherical | 80 µg/ml | HK-2 normal human kidney cells | High mitochondrial activity. No cytotoxicity. |

[224] | ||||

| 10–20 (12.4) nm | 0–100 µM | 24h 48h |

Lung carcinoma A549 cell line, MCF-7 breast cancer cells, androgen-independent prostate cancer cell DU-145, androgen-dependent LNCaP, embryonic kidney HEK-239 |

Suppression of AR (androgen receptor) through phosphorylation of AKT. | [225] | |||

| 50 nm Aggregate: 442 nm |

Spherical | 4–20 µg/ml | 72 h | Human cervical cancer HeLa cells, HK-2 normal human kidney cells | [226] | |||

| Silica | 19, 43, 68 nm | 100 μg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Upregulation of MAPK/JNK and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. |

[227] | ||

| 15, 30 nm | 10 and 15 μg/ml | 24 h | HaCaT keratinocytes | Upregulation of SERPINB5 | [228] | |||

| 21 nm | 200–600 μg/ml | 12 & 24 h | L02 normal liver cell line | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [229] | |||

| 20 nm | 50–200 μg/ml | 24 h | HUVECs | Upregulation of MAPK/JNK and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. |

[230] | |||

| 20 nm | 160 and 320 μg/ml | 24 h | Huma hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Upregulation of TP53. | [231] | |||

| 20 nm | 1 mg/ml | 24 h | Buffalo rat liver cells | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [232] | |||

| 14 nm | 1–200 μg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. |

[132] | |||

| 15 nm | 25–200 μg/ml | 72 h | Epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells | [233] | ||||

| 20 nm | 62.5–250 μg/ml | 48 h | Human hepatic cell line (HL-7702) | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [234] | |||

| 43 nm | 25–100 μg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Release of CYCS into the cytosol. Downregulation of BCL2. |

[235] | |||

| ZnO | 21, 34 nm | 15 μg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 cells, lung carcinoma A549 cell line, human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [236] | ||

| 22.5 nm | 20 and 25 μg/ml | 24 h | BJ human neonatal foreskin | TP53 (after TP53 knockdown, the cells become more resistant to NP-induced cell death, and they increase cell-cycle progression). | [237] | |||

| 23, 47 nm | 2.5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml | 4, 24 h | Human dermal fibroblast | Upregulation of MAPK/p38 and TP53. | [238] | |||

| 30 nm | 20 μg/ml | 12 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 Cells | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [239] | |||

| 17 nm | 5, 10, and 20 μg/ml | 24–48 h | Human skin melanoma (A375) | [240] | ||||

| 52 nm | 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/ml | 24–48 h | Lung carcinoma A549 cell line | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BIRC5/survivin and BCL2. | [134] | |||

| 40 nm at 60 mg/L, and 60 nm at 120 mg/L | 60, 90, or 120 mg/L nano-ZnO | 96 hpf | Zebrafish embryos | [241] | ||||

| 20 nm | 30 μg/ml | 12 h | Human ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3) | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [242] | |||

| 70 nm | 8, 15, 25 and 50 μg/ml | 12 h | Human aortic endothelial cells | Upregulation of BAX and FAS. Downregulation of BCL2. | [243] | |||

| 60 nm | 0, 2.5, 5.0 and 10.0 μg/ml | 2 h | Retinal ganglion RGC-5 cells | [244] | ||||

| 13 nm | 50 μg/ml | 24 h | Human hepatoma HepG2 cells | Upregulation of BAX and TP53. Downregulation of BCL2. | [245] |

The specific cell response to the presence of NPs is complex and determined by many diverse factors. For example low concentrations of silver (Ag) NPs induce necrosis and apoptosis, whereas necrosis alone is triggered at higher concentrations [75]. Also the exposure time of the Ag NPs dictate the mode of cell death (apoptosis or necrosis) in different experimental models, such as human skin, fibrosarcoma, and testicular carcinoma cells [76–78]. It should also be mentioned that the mode of cell death that is induced is cell type-specific [79,80].

In the present review a comprehensive literature survey on the cell fate induced by NPs and the molecular mechanisms involved will be reported.

Necrosis triggered by NPs

NPs and necrosis and/or necroptosis

There are conflicting examples in the literature about necrotic effects of NPs because on the one hand most reports only studied losing cell viability without focusing on the exact mode of cell death, and on the other hand in some conditions apoptosis can be followed by secondary necrosis, thus leading to an incorrect interpretation [70].

For instance, it was found that both crystal structure and size affect the mechanism of cell death induced by titanium dioxide (TiO2) NPs in mouse keratinocyte cells [81]. This study demonstrated that TiO2 NPs with 100% anatase crystal structure elicit necrosis in a size-independent manner, whereas TiO2 NPs with rutile crystal structure induce apoptosis. In a systematic study by Pan et al., gold NPs show size-dependent cytotoxicity; smaller-sized NPs (< 1.4 nm) are more cytotoxic and induce necrosis, whereas NPs larger than 1.4-nm particles often induce apoptosis [82,83]. Interestingly, the 15-nm gold NPs do not show any cytotoxic effects in different cell lines and are actually inert with regard to toxicity. Moreover, surface charge can also be a major factor in determination of the cell death modalities induced by NPs. Schaeublin et al. [84] showed that charged gold NPs induce apoptotic cell death, whereas neutral NPs trigger necrosis. Another study demonstrated that cationic carrier-induced cell necrosis is dependent on the nanocarrier surface cationic charge [85]. The toxicity is related to the shape of polyaniline (PANI). NPs with 4 various aspect ratios were assessed with regard to their effect on fibroblast cells of human lung and it was shown that low-aspect ratio PANI NPs induce necrosis more than the others [86].

Moreover, recent evidence shows that cytotoxic effects of germanium NPs (4 nm) are blocked by necrostatin-1, suggesting that NPs may also induce necroptosis [87]. A very recent paper reports that selenium (Se) NPs induce ROS-mediated necroptosis in PC-3 cells following cellular internalization [88].

Other parameters that may affect the triggering of necrosis include exposure time and concentration (Table 1). For example, nano-C60 fullerene at high doses induces ROS-mediated necrosis, whereas an ROS-independent autophagic cell death is observed with low-dose NPs in glioma cells [74].

Pathways of NP-triggered necrosis

From the presented information, it is clear that advances in knowledge concerning the causes that may influence NP-induced necrosis will need more accurate and precise studies [89–91]. Nevertheless, a pro-oxidant pathway is one of the main mechanisms involved in NP-induced necrosis. Indeed, various NPs exhibit toxicity dependent on oxidative stress. ROS produced by NP exposure can lead to lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation and oxidative DNA damage. Excess free radical generation causes the reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential and leads to mitochondrial membrane damage, causing necrotic cell death [71,87]. For example, water-soluble germanium NPs trigger necrosis through an increase of the cellular calcium level, which subsequently leads to an increase at the level of ROS. Also, gold NPs (1.4 nm) induce necrosis through mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress, resulting not only from ROS but also induce a decrease in the intracellular antioxidant defense system as seen in HeLa cells [82]. Similar data have been presented by Liu et al. who reported that necrosis is an essential mechanism of cell death induced by gold NPs in lung cancer cells with a low level of intracellular glutathione (GSH). Therefore, there is evidence that triggering necrosis induced by NPs can be a beneficial approach for treating cancer [92].

High concentrations of Ag NPs induce necrosis in the breast cancer MCF-7 cell line [75] and can have a toxic effect on the respiratory system through reduced GSH levels, and increased ROS generation [93]. Generally, Ag NP cytotoxicity depends on dose, time, temperature, surface coatings, size and cell type [94]. Ag-NP exposure causes reduction in antioxidant enzymes such as GSH, in elevated levels of intracellular ROS and the consequent elevated expression of ROS-responsive genes, and lipid peroxidation, leading to DNA damage, necrosis and apoptosis [95,96]. Both Ag NP degradation into ions, and ROS generation depend on size; and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-coated Ag NP size negatively correlates with ROS level, necrosis and apoptosis and decreased cell viability [97]. ROS generation and silver ion release are 2 crucial factors mediating cytotoxicity that lead to Ag NP-mediated necrosis and apoptosis. Although both Ag NPs and Ag ions result in increased ROS and oxidative stress throughout the cell, Ag NPs cause stronger oxidative damage in cellular membranes and organelles, such as mitochondria, lysosomes and the nucleus, which directly leads to apoptosis or necrosis [94]. In the presence of oxygen, Ag ions catalyze ROS generation and Ag NPs themselves can induce a process to release Ag ions, in addition to generating ROS and causing oxidative stress in vitro [98]. The studies show that Ag NPs (15 and 100 nm) induce a significant depletion of reduced GSH, and cause an increase in ROS levels and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential in BRL 3A rat liver cells and rat alveolar macrophages [99,100]. Furthermore, 25-nm Ag NPs cause a significant increase in ROS both in vitro and in vivo. Recently, ROS generation was detected in the MC3T3-E1 and PC12 cell lines in a manner dependent on particle size and concentration [79,101]. As already stated, NP size can influence the cell response. Citrated coated Ag NPs of 13 nm induce higher cell membrane damage and ROS production while having a stronger bacteriostatic potential than the same particles of 17 nm. Thus, these NPs may be considered in cancer therapy [102].

Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs increase basic ROS levels of macrophages and induced oxidative DNA damage-mediated necrosis. Therefore, clinically, ZnO NPs through this mechanism can help the immune system in the clearance of inhaled particulates during inflammation [87]. A novel mechanism by which cationic nanocarriers such as polyethylenimine (PEI), cationic liposomes, and chitosan, lead to rapid necrosis is related to their positive surface charges. In fact, acute cationic nanocarrier-induced necrosis occurs via an interaction with the Na+/K+-ATPase and is associated with the exposure of molecular patterns dependent on mitochondrial damage that lead to inflammatory responses. Although the toxicity of nanocarriers with positive surface charges hinders their clinical applications, the understanding of cationic carrier-induced acute cell necrosis can assist in the better and safer design of nanocarriers in drug delivery systems and also the development of screening assays and rapid assessment of biomaterials [84].

Another mechanism involved in necrosis induced by NPs is induction of endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction through release of VWF (von Willebrand factor). EC dysfunction induced by NPs, can also be due to the formation of ROS, inflammatory cytokines including IL6 (interleukin 6) and IL8 and/or the activation of the system of coagulation that causes pulmonary and ischemic cardiovascular diseases [87]. Many studies revealed that silica NPs induce pulmonary inflammation through dysfunction of ECs with the clotting cascade activation that leads to increase of blood coagulability in vivo [103]. In addition, silica NPs participate in ROS production and inflammatory responses in vitro [104–107].

Another pathway involved in necrosis triggered by NPs is the rapid degradation of NPs in lysosomes and the subsequent destabilization of this organelle that will allow the toxic substance to enter into the cytosol, and finally lead to cell necrosis. For example, cadmium telluride (CdTe) quantum dots (QDs) induce mitochondrial permeability transition via the increase of ROS, which leads to swelling of mitochondria and collapse of the membrane potential. Because of their large surface:volume ratios, adding QDs into the culture medium causes serum proteins to attach to the QD surface. This absorption alters the properties of surface and size, and leads to the cellular uptake of the QDs through the endocytic pathway mediated by clathrin. After that, QDs translocate in cells via endocytic vesicles and then are rapidly degraded in lysosomes, leading to cell necrosis. Therefore, considering the cytotoxicity mechanism of CdTe QDs can provide valuable data for the safe use of QDs in the future [108].

Tubulin and actin are 2 factors involved in necrosis induced by certain NPs such as different nanostructures of ZnO, including ZnO commercial NPs and custom‐made nanowires of ZnO. Extra levels of cytoplasmic zinc have cytotoxic effects. Moreover, tubulin and actin, important cellular cytoskeleton proteins involved in migration, cell division and maintenance of cellular architecture, control zinc homeostasis in the cells. Following ZnO intracellular dissolution, actin microfilaments and microtubules undergo dramatic structural modifications and an acute cytoskeletal collapse that trigger a rapid necrotic process in most cells. There might be possible health risks for these NPs on skin and mucosa in children that cause significant cell damage and aneuploidies that eventually lead to cell transformation and cancer [109].

Apoptosis triggered by NPs

NPs induce intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways

ROS generation induced by NPs causes damage to DNA, proteins and organelles, including mitochondria. Damaged mitochondria lead to induction of intrinsic and then extrinsic apoptosis pathways [125]. The central role of ROS in various cellular functions, including cell cycle regulation, proliferation, self-renewal, differentiation and apoptosis is well known [126]. TP53/p53 can protect the genome during stressful conditions, such as ROS-mediated DNA damage. The primary function of this bodyguard of the genome is to induce cell cycle arrest in order to allow time for repairing damage. If the DNA damage cannot be repaired the cell responds by shifting to apoptosis [127]. Apoptosis is regulated by the BCL2-family proteins that are comprised of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members as discussed above (see Mechanism(s) of apoptosis in mammalian cells) [128]. The BAX:BCL2 ratio determines the threshold of cell death in response to an apoptotic stimulus. An increase in the BAX:BCL2 ratio decreases the cellular resistance to apoptotic stimuli, leading to caspase-mediated apoptosis [129,130].

NPs can induce oxidative stress in cells through different mechanisms: (i) direct generation of ROS by their physico-chemical properties, (ii) indirect generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) by stimulating inflammatory cells, (iii) indirectly through changes on mitochondrial integrity such as through effects on NADPH oxidase or cellular calcium homeostasis, and (iv) ROS generation by releasing ions or soluble compounds from certain types of NPs (e.g., metal oxides) [131].

Similar to necrosis, NP-induced apoptosisis is also a function of the NPs physico-chemical structure (Table 2). For example, metal NPs, such as copper oxide/CuO, cadmium oxide/CdO, and TiO2 NPs, exhibit different apoptotic potency [32].

NP-induced apoptosis is size, concentration and time dependent. Ahmad et al. [132], reported that 14-nm silica NPs induce a dose-dependent depletion of GSH and ROS-mediated apoptosis response in human liver HepG2 cells. In addition, the cell cycle regulatory gene TP53 and apoptotic genes (BAX and CASP3) are upregulated, whereas BCL2 is downregulated in cells exposed to silica NPs in a dose-dependent manner [132].

Ye et al. [229] reported that silicon dioxide (SiO2) NPs regulated the expression of the TP53 and BAX genes, in an NP dose-, size- and exposure time-dependent manner. SiO2 NPs show ROS-mediated oxidative stress and consequently apoptosis in L-02 cells [229].

ZnO NPs dose and time dependency was shown by Ahamed et al. who reported ZnO NP upregulation of BAX and downregulation of BIRC5/survivin and BCL2 in lung cancer cells (A549 cells) [134]. Ag NPs induce oxidative stress resulting in genotoxicity in a TP53/p53-dependent manner in a variety of experimental systems such as adult cells, stem cells and cancer cells [135–138].

Liu et al. [139] showed that high doses of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs)-induce mitochondrial apoptosis by increasing the BAX:BCL2 ratio, by the activation of CASP9 and CASP3 and by downregulating HSPA/HSP70 and HSP90 survival factors [139].

NPs induce mitochondrial apoptosis

The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is one of the important mechanisms that contributes to the cytotoxic effects of NPs. Several NPs such as TiO2, CuO, ZnO, SPIONs and silica NPs affect mitochondrial pathways [130,140–143]. Yan et al. [206] showed that graphene and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) are more cytotoxic than graphene-SWCNT hybrids, and the 3D nanostructures induce a ROS-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in osteosarcoma cells. Low-dose exposure to silica NPs causes epigenetic toxicity associated with mitochondrial apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells. Zou et al. [145] showed that the silica NPs over 30 passages significantly hypermethylate the promoters of the CREB3L1 and BCL2 genes.

Ag NPs trigger activation of the TP53 protein, which in turn increases the expression level of BAX, BAD and BAK1, causing mitochondrial membrane leakage and release of CYCS. In parallel, the apoptosis inducer MYC/c-MYC is upregulated, and anti-apoptotic genes, such as BCL2 and BCL2L1, are downregulated. These signaling pathways trigger cell blebbing [136]. In another study, Hsin et al. reported that Ag NPs induce mitochondrial apoptosis in NIH3T3 cells. The NPs generate ROS and trigger a JUN/c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent mechanism [115].

Permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane occurs by exposing cells to graphene, resulting in a change in mitochondrial membrane potential [146]. Graphene, by increasing ROS generation, affects the MAPK and TGFB/TGF-β signaling pathways and activates CASP3. The carbon-based nanomaterial induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [147,148]. Similarly, low doses of reduced graphene oxide induce an early apoptosis via death-receptor and canonical mitochondrial pathways [149]. Graphene can act in different ways: GO leads to an ROS-dependent apoptotic pathway, and GO-COOH activates an ROS-independent apoptotic pathway. T lymphocytes undergo apoptosis after the membranes have been damaged by exposure to GO-PEI [150,151]. Gadolinium oxide induces mitochondrial apoptosis with increasing doses and exposure time in human neuronal (SH-SY5Y) cells. Ahmad et al. [152] demonstrated that the number of apoptotic cells is increased with an increase of the concentrations of nickel NPs in mouse epidermal JB6 cells.

NPs induce ER-mediated apoptosis

The ER has pivotal functions in cells for controlling protein folding and calcium homeostasis. The release of calcium into the cytosol from the ER occurs upon ER stress [153]. Transcription factor CREB phosphorylation, which induces the transcription of PPP2 (protein phosphatase 2), is induced by an increase in the calcium concentration. PPP2 regulates various critical cellular processes [154]; therefore, ER stress-inducible regulation of PPP2 contributes to the cytotoxicity of NPs [155].

High doses of NPs can generate ROS, damage membrane and disrupt calcium homeostasis to cause cell death [156,157]. Ag NPs induce transient changes in intracellular calcium in human lung fibroblasts [158]. Additionally, TiO2 NPs increase intracellular free calcium [159]. Cytotoxic NPs trigger ER stress, and the associated changes in calcium homeostasis may be an important aspect of the response that results in apoptosis [155].

ER stress causes accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates and triggers apoptosis through the blocking of nutrient transport to retinal cells [160], and occurs in response to ZnO NPs in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [161], and also as a result of exposure to poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) [162] and gold [163] NPs in human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells.

As suggested by the references above, ER stress can result in apoptosis. ATF4 induces DDIT3/CHOP (DNA damage inducible transcript 3) expression, and the expression of the apoptotic genes BCL2L11/BIM and BBC3/PUMA is induced by DDIT3 [155]. The ERN1/IRE1 pathway may induce apoptosis through the activation of MAP3K5/ASK1 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5) and through interaction with TRAF2 (TNF receptor associated factor 2). Therefore, SiO2-NPs may exert hepatotoxic activity through ER stress. PMAIP1/Noxa [164], is another factor that can induce apoptosis—in this case through the USP9X-MCL1 pathway—in response to ER stress [165].

Multiple signaling pathways regulate inflammatory and immune responses. Among them are the NFKB and MAPK signaling pathways, involving MAPK1/ERK2-MAPK3/ERK1, which regulate inflammatory and immune responses [166]. The MAPK signaling pathway also plays an important role in cancer development and apoptosis [155].

TiO2 damages DNA and activates TP53 by being deposited in the membrane of the nucleus in HEK-293 cells [167]. TP53 is a key tumor suppressor that blocks the cell cycle in the G1/S phase. Through TP53, DNA damage causes the initiation of apoptosis [168]; SiO2 NPs significantly downregulate TP53 in Huh7 cells. Transcriptional downregulation of TP53 could contribute to the apoptotic or carcinogenic activity of SiO2 NPs [155].

In one study, Simard et al. reported that Ag NPs cause protein misfolding, leading to ER stress in MCF-7 and T47-D cells. The NPs activate several caspases leading to apoptosis through constant activation of the UPR pathway [169]. Chen et al. [161] reported significant cellular ER stress induced by ZnO nanorods at noncytotoxic concentration. ZnO nanorods change both the transcriptome and proteome of HUVECs. The NPs in higher dosage (240 μM) result in an ER stress response before apoptosis induction [161]. Yang et al. [171] showed that hepatotoxicity of orally delivered ZnO NPs is mediated through an ER stress-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway and increased translation of related proteins in mice. In another study Kuang et al. [172] reported that ER stress-mediated apoptosis triggered by ZnO NPs is size dependent, and smaller ZnO NPs are more toxic than 90-nm ZnO NPs in murine liver.

Two-fold role of autophagy and dysregulated autophagy as a cytoprotective mechanism and death signal triggered by NPs

How do you set up an autophagy investigation for nanomaterials and what markers do you use?

The size of NPs, their functionalization and surface charge influence autophagy pathways and must be carefully evaluated before in vitro and in vivo investigations. In some cases (eventually as a biodegradation mechanism) [246,247], cationic NPs more than anionic ones [248] and some functionalizations such as arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) induce autophagosomes at higher levels [249]. However, other stressful factors that trigger autophagy such as cell membrane damage, and ROS production must be evaluated to give more information on the mechanism. After the characterization of NPs and evaluation of some eventual risk factors, to track autophagy, autophagosomes as double-membrane vesicles might be monitored via electron microscopy [250].

To accurately evaluate autophagy activity, the analysis should be categorized into 2 separate elements: static and dynamic measurements. The importance of differentiating between dynamic and static measurements is easily seen when considering the most common types of assays that are used for monitoring autophagy—the presence of autophagosomes based on fluorescence and electron microscopy, and the level of LC3 based on western blot. In particular, the increase or accumulation of these autophagic markers can be an indication of autophagic induction; however, because both autophagosomes and LC3 are degraded in the terminal stages of autophagy, an increase of either component can also be the result of a block in turnover or flux, resulting from a defect in autophagosome or amphisome fusion with the lysosome or in degradation within the lysosome.

Nonetheless, static measurements can be useful if used appropriately. For example, the phosphorylation status of MTOR, BCL2, AMPK, and ULK1 at specific sites as assessed by western blot correlate with autophagy induction. In addition, the evaluation of gene expression via real-time PCR can provide another valid method for assessing induction when used in combination with other assays. Monitoring the complete process of autophagy requires an assessment of flux. This can be achieved by examining the turnover of LC3 and cargo proteins such as SQSTM1/p62 by western blot in the presence and absence of fusion, acidification or lysosomal protease inhibitors, or by following long-lived protein turnover [251]. Fluorescence techniques can be used that rely on tandem mRFP/mCherry-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 or the more recent GFP-LC3-RFP-LC3∆G [252]. Thus, similar approaches can be used to determine the effects of NPs on auto-phagic flux. In particular, cells exposed or not to NPs can also be treated with fusion inhibitors such as bafilomycin A1, alkalinizing agents such as chloroquine, or protease inhibitors including E64-d, leupeptin and pepstatin A. It is also important to note that some NPs are sequestered into the lysosome and may induce lysosomal dysfunction. Thus, when using NPs it may be worthwhile to monitor lysosomal pH and degradative capacity. Neutral red, acridine orange and LysoSensor dyes can be used as pH-dependent lysosomotropic indicators, whereas DQ-BSA and Magic Red™ can be used to follow degradative activity [253].

NPs and autophagy

Autophagy has a close crosstalk with other cell death and signaling pathways; thus, cellular outcomes induced by autophagic NPs are very complex [250]. Although NPs primarily induce macroautophagy, based on the increased formation of and detection of NPs within autophagosomes, it is difficult to classify autophagic effects of NPs as a cell death mechanism at first glance [4,250,254]. In most cases, cells respond to NPs as an endosomal pathogen; the NPs are ubiquitinated leading to sequestration by a phagophore. Interestingly, size and concentrations of the nanomaterials influence the autophagic response [4,254]. This fact may explain why it is typical to observe a particle present in autophagosomes on the nano rather than micro scale [255–257]. The consequence of internalization of NPs and their accumulation within autophagosomes can be the disturbance of autophagy flux via interference with vesicle trafficking and the cytoskeleton, and a decrease or inhibition of lysosomal stability and enzyme activity. All these events suppress fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes and ultimately induce autophagy blockage. The cumulative result of NP-induced autophagy blockage can be an accumulation of damaged DNA, proteins and organelles that in turn can increase the risk of cancer [258] and neurodegenerative diseases [259,260].

Conversely, some NPs, such as manganese NPs [261], core-shell of Fe@Au NPs and TiO2 NPs [4,262], induce a functional autophagy response in cells that may terminate in cell death. This autophagy flux response is mostly reported for those NPs that can augment ROS levels in the cells and subsequently may stimulate mitochondria-dependent autophagic cell death, depending on their physico-chemical properties (Table 3) [4,254]. In this scenario, autophagic effects of NPs may have therapeutic value [4,263].

The role of different types of NPs in inducing the autophagy pathway

NPs are taken up into cells and treated almost the same as a bacterium or any other particulate pathogen with a goal of degrading them. These NPs are ubiquitinated allowing them to interact with receptor proteins such as SQSTM1/p62; the latter typically contain an LC3-interacting region, a short motif that allows them to bind LC3 or another Atg8-family protein, resulting in sequestration by a phagophore [264]. Based on the above discussion, the influence of NPs on autophagy may be categorized in 2 distinct parts: An increase of auto-phagosome formation and flux, or autophagic dysfunction. In both categories, the NPs typically increase the LC3-II protein; however, in the case of dysfunction there will also be an increase in SQSTM1/p62, which is no longer degraded via autophagy. For example, SWCNT [265], carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes [266], graphene oxide, PAMAM dendrimer [248], gold [267] and iron oxide [255] NPs induce autophagosome accumulation and block autophagy flux. Other NPs that lead to the accumulation of autophagosomes and autophagy blockage as can be seen with fullerene and its derivatives, Au NPs [260], may even disrupt lysosomal trafficking [268]. Interestingly, autophagosome activation resulting from exposure to graphene oxide NPs involves the TLR pathway [269]. However, fullerene at nanocytotoxic concentration may induce autophagy and increase the killing potential of chemotherapeutics, and even may be influential in treatment of neurodegenrative disorders. In fact, the effects of NPs show two-fold behavior based on concentration—they may either disrupt autophagy or induce auto-phagy [250].

Cationic dendrimers, nano-scale and non-agglomerated quantum dots, alumina NPs, fullerenes, negatively charged zinc oxide NPs [270], Au NPs (22 nm), silica NPs, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), TiO2 NPs, ultra-small super paramagnetic iron oxide (USPION) NPs, palladium NPs and some others induce autophagy in part by inhibition of MTOR or by inducing the expression and/or phosphorylation of autophagy-related and BCL2-family proteins involved in autophagy [259].

Because one of the triggering mechanisms of autophagy activation is via ROS production, metallic NPs such as Ag [271], Au [272] and Cu may be involved. Au NPs induce autophagy but act through different mechanisms such as perturbation of the cytoskeleton, blocking fusion, and alkalinization of the lysosome, causing lysosomal dysfunction and subsequent autophagy blockage [255]. Iron core and gold shell NPs induce a transient loss of mitochondrial membrane-potential in normal cells and irreversible ones in cancer cells as a mechanism that triggers autophagy by ROS production and involvement of the MTOR signaling pathway [262]. Nano alumina results in an increase in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier due to decreased expression of tight-junction proteins that is related to the triggering of autophagy and cytotoxicity [273]. However, this NP is considered as a candidate in anti-tumor therapy due to its being scavenged as an antigen by T cells, so that less antigen is needed overall to provoke adequate T cell production [246]. Similarly, Ag nanowire, manganese NPs, neodymium(III) oxide (Nd2O3), samarium oxide, europium oxide, gadolinium oxide, cerium dioxide, lanthanum oxide and terbium oxide NPs also induce autophagy [250].

Fullerenes induce the production of ROS and damage to mitochondria [274] and the ER, resulting in autophagy induction. Autophagy activation by fullerenes and its derivatives, especially C60(Nd) [275], makes them ideal NPs for cancer therapy in combination with drugs such as doxorubicin; these NPs can induce cell mortality in the breast cancer MCF-7 cell line by the involvement of ATG5 and ROS production [274].

It should be mentioned that the autophagic effects of NPs are highly dependent on their physico-chemical characterization, including size, dispersity and surface charge and as well as their concentrations. One of the best examples is TiO2, a principle component of cosmetics, that induces both auto-phagy flux and blockage in a size-dependent manner [276]. NP functionalization also affects cancer cell viability. For example, Liu et al. showed that COOH-CNT induces autophagy and mortality in human lung adenocarcinoma through a decrease of phosphorylated (i.e., active) MTOR, whereas PABS-CNTs and PEG-CNT do not have this effect [227]. Besides, specific surface characteristics such as nanotopography (vertical aligned nanotubular surface in the range of approximately 100 nm) as compared to flat surface dictates a reversible and temporal MTOR-independent autophagy in osteoblast cells to modulate differentiation via cell membrane stretch [277].

Increase and decrease of autophagic flux by NPs

Increase of autophagic flux by NPs and their functionalization

Increase and decrease of autophagy flux is defined by the increase and decrease in autophagic degradation activity [95]. It seems that increase of acidification in impaired lysosomes leads to restoration and increase of autophagic flux. Based on this finding, polymeric NPs such as PLGA NPs are favorably taken up by lysosomes and their degradation produces an acidic pH [278]. Trudeau et al., prepared a photoactivable NP that in the presence of water and UV irradiation turns to an acidic NP. They demonstrated that an increase of acidic pH in impaired lysosomes leads to an increase of pH and restoration and increase of autophagic flux along with a decrease of SQSTM1 [279]. In addition, graphene QDs increase auto-phagy flux when irradiated by 470-nm blue light as assessed by LC3-II increase and SQSTM1 decrease [280]. Furthermore, QDs increase autophagy flux based on their chemical formulation; CdSe QDs induce a stronger autophagy flux than InGa QDs, while the size of the former was larger than that of the latter [281].

Another important point is that some NPs increase autophagy flux to compete with oxidative stress. As a result, for gold NPs there are different reports on its decrease [282] and increase [283] of autophagy flux. Fe@AuO NPs increase autophagy flux through the MTOR signaling pathway in response to ROS production. Of greater interest, however, is that Fe@AuO NPs behave selectively in normal and tumor cells and lead to tumor cell death [267]. Among ZnO, FeO and TiO2 NPs, only TiO2 NPs increase autophagy flux in response to oxidative stress in a size-dependent manner [276].

Functionalized fullerene (poly ethylene glycol [PEG] or pentoxifylline) may induce autophagy and increase autophagy flux that may lead to elimination of β-amyloid, resulting in inhibition of Alzheimer symptom development [284]. Finally, studies indicate that there are different behaviors of functionalized CNTs. Although, COOH-CNT induces autophagy flux through the AKT-MTOR pathway both PEG and poly-aminobenzene sulfonic acid CNTs do not induce autophagy [227].

Decrease of autophagy flux by NPs

Nanoparticles lead to autophagy dysfunction through disruption of microtubules and actin

The cascade of autophagy may be disrupted via interfering with delivery to the lysosome due to microtubule and or motor protein dynein destruction. It has been disclosed that disturbance in actin polymerization influences autophagosome trafficking. A variety of NPs such as TiO2, polystyrene, silicon, Au NPs [285], CNT [286] and USPION [287] possess binding affinity to actin, resulting in alterations in its polymerization potential. Studies indicate that fullerene [288], TiO2 [289] and Au NPs [290] inhibit microtubule polymerization by the formation of hydrogen bonds with tubulin heterodimers. SWCNT [291], fullerol [260] and silicon dioxide NPs [292], alter autophagy directly via bonding or indirectly via expression of actin modulatory proteins. However, in some studies, it was disclosed that Au NPs cause damage to the cytoskeleton but not via tubulin and actin [285], and Fe2O3 NPs decrease the number of actin filaments [293], whereas Fe3O4 NPs—via bonding to tubulin dimers—change microtubule polymerization [294], also resulting in a decrease of VCL (vinculin) spots and disorganized tubulin and actin structures, along with autophagy dysfunction in blood outgrowth endothelial cells, HUVECs, and neural progenitor cells as a possible reason for toxicity [287,295].

Lysosomal dysfunction by NPs

As indicated above, NPs tend to become trapped within autophagosomes and lysosomes due to their size, ubiquitination and similarity in some aspects to particulate pathogens. Thus, they can directly and indirectly induce dysfunctionality in autophagy that may lead to cell death and many pathological conditions [259].

Lysosomal dysfunction by NPs may be derived from lysosome membrane permeabilization. Oxidative stress by lysosomal-iron mediation and release of lysosomal hydrolases and cathepsins can lead to permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane [253] that in turn, via ROS production, induces apoptosis or necrosis. In addition, lysosomal dysfunction by NPs may be due to a lack of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase activity, increase of pH, bio-persistence and inhibition of functional lysosomal enzymes, which can lead to lysosomal storage disorders, such as sphingolipidoses [296] as reported for fullerenes [297] and dendrimers [298].

Based on the literature, those NPs that cause lysosomal dysfunction include CNT, negative-charge Au NPs (5 nm), negative-charge Ag NPs (25 nm), negative and neutral TiO2 NPs (5–500 nm), fullerenes (150 nm), PEGyated NPs, ZnO NPs, positive-charge dendrimers (5 nm) and positive-charged polystyrene (110 nm) [259]. Cationic NPs, such as cationic dendrimers (G5) [299], act, at least in part, as ‘proton sponges’, resulting in the accumulation of protons in the lysosome and subsequent organelle osmotic swelling followed by lysosomal rupture [80]. Other NPs destabilize the lysosome and induce dysfunctionality in different ways [272,300]. For instance, ZnO NPs (release of Zn2+) [300], TiO2 [301] and polystyrene NPs [302], induce intracellular ROS production, fullerol blocks lysosomal trafficking by affecting actin [260], and Au NPs alkalinize the lysosome (acting as a proton pump inhibitor) and block fusion with autophagosomes [255].