Abstract

Sodium disilicate (SD), an inorganic and environmentally friendly ligand, is introduced into the conventional iron electrolysis system to achieve an oxidizing Fenton process to degrade organic pollutants. Electrolytic ferrous ions, which are complexed by the disilicate ions, can chemically reduce dioxygen molecules via consecutive reduction steps, producing H2O2 for the Fenton-oxidation of organics. At the near-neutral pH (from 6 to 8), the disilicate-Fe(II) complexes possess strong reducing capabilities; therefore, a near-neutral pH rather than an acid condition is preferable for the disilicate-assisted iron electrolysis (DAIE) process. Following the DAIE process, the different complexing capacities of disilicate for ferrous/ferric ions and calcium ions can be used to break the disilicate-iron complexes. The addition of CaO or CaCl2 can precipitate ferrous/ferric ions, disilicates and possibly heavy metals in the wastewater. Compared to previously reported organic and phosphorus ligands, SD is a low-cost inorganic agent that does not lead to secondary pollution, and would not compete with the target organic pollutants for •OH; therefore, it would greatly expand the application fields of the O2 activation process. The combination of DAIE and CaO treatments is envisioned to be a versatile and affordable method for treating wastewater with complicated pollutants (e.g., mixtures of biorefractory organics and heavy metals).

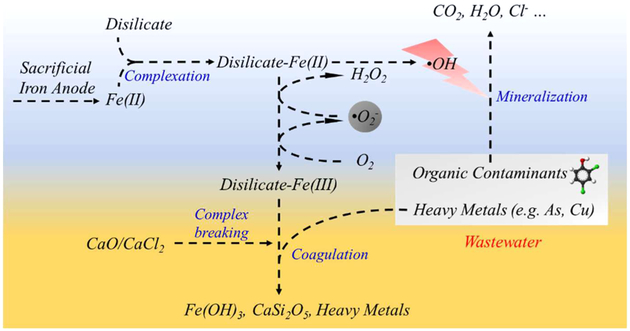

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

To treat wastewater from industrial sources, various technologies that use electrochemical principles have been developed and applied. The application of these electrochemical technologies in the fight against water pollution has several important advantages, such as high efficiency, mild operating conditions, ease of automation, and versatility.1,2 Electro-Fenton technology based on Fenton’s reaction is an eco-friendly and efficient approach that has received a great deal of attention in the context of wastewater treatment.3 In its original form, catalytic ferrous salt was added and H2O2 was generated via the two-electron electrochemical reduction of O2 (O2 + 2H+ + 2e− → H2O2) at an O2—diffusion carbon—PTFE electrode.4 To maintain the dissolved state of the ferrous ions, the reaction solution needed to be acidic, and a pH value of approximately 3 was found to maximize the performance of the electro-Fenton method. In addition to the O2—diffusion carbon—PTFE electrode, various carbonaceous electrodes, such as graphite,5 vitreous carbon foam,6 carbon felt,7 porous carbon8 and carbon aerogel9 were then tested for the electrogeneration of H2O2 in electro-Fenton systems. Simultaneously, the electro-Fenton method was improved by the generation of ferrous ions from an iron anode, leading to the so-called peroxicoagulation process.10 As such, the ferrous ions derived from the iron anode were finally transformed to ferric hydroxides and polymeric hydroxyl complexes,11 allowing the coexistence of advanced oxidation and coagulation processes for the removal of contaminants in an undivided electrolytic cell. However, an acidic condition was still necessary for the peroxi-coagulation method to achieve its oxidizing capability.10 To avoid adjusting the pH of the reaction solution, Lemley proposed an anodic Fenton treatment (AFT),12 in which an ion-exchange membrane was used to separate the electrolytes to prevent the electrodissolved ferrous ions from precipitating. With the externally added H2O2, the AFT reportedly treated the herbicide compounds effectively,12 however, the use of an ion-exchange membrane is undesirable in a practical water treatment system.

In the presence of chelators/ligands, ferrous ions can be effectively complexed and their dissolving state can be maintained under a neutral or weakly alkaline pH. A variety of compounds have been reported to possess the ability to coordinate ferrous/ferric ions in an aqueous solution, such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethylenediamine-N,N’-disuccinic acid, nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), and tetrapolyphosphate. With the assistance of these chelators/ligands, Fenton-oxidation can be accomplished with ferrous salts and H2O2 under a wider pH range, and therefore contribute to the degradation of organic pollutants.13–15 Moreover, researchers have reported that the complexation of ferrous ions with appropriate ligands could efficiently decrease the redox potential of the Fe(III)/Fe(II) couple, making the reduction of O2 more thermodynamically favorable. The reduction reactions include two consecutive steps shown as below (eq 1 and 2)16–19

| (1) |

| (2) |

The chemical reduction of O2 can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion radicals and H2O2; therefore, it is also recognized as the activation process of O2.20 The addition of oxalate, NTA, and EDTA to a solution containing zerovalent iron can significantly increase the yield of oxidants due to oxygen activation in association with complexed ferrous ions.21 Likewise, the presence of polyphosphatic chelators can enhance the generation of reactive radicals derived from the activation of O2.22 Naturally, the in situ generated H2O2, via reactions eqs 1 and 2, can be used to trigger the Fenton’s reaction to degrade contaminants.18,23 However, organic ligands such as NTA and EDTA have some disadvantages when they were used for advanced oxidation. They can consume ROS leading to a lower oxidation efficiency of the target contaminants,24 and their presence in an aqueous solution can also cause serious secondary pollution. Polyphosphate is an alternative inorganic ligand that is not oxidizable.25 However, the use of polyphosphate may cause problems for subsequent phosphorus removal. Therefore, currently available chelators/ligands for O2 activation are not applicable in practical wastewater treatments.

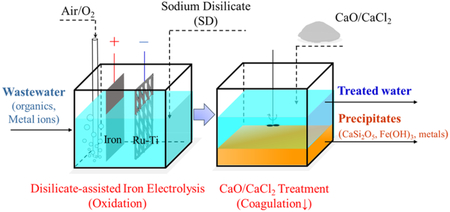

In this study, a combination of disilicate-assisted iron electrolysis (DAIE) and CaO coagulation is proposed to treat wastewater containing both organics and heavy metals. Our hypothesis is that, in the DAIE process, the electrolytic ferrous ions will coordinate with disilicate to activate the dioxygen, producing H2O2 that will contribute to the oxidative degradation of the organics. Afterward, the addition of low-cost CaO or CaCl2 can remove the remaining disilicate—iron complexes and heavy metals via the coagulation/coprecipitation process. Specifically, the sodium disilicate (SD) used in this study is an environmentally friendly reagent that will not cause secondary pollution; however, its complexing capacity to ferrous/ferric ions has not yet been reported. The combination of DAIE and CaO/CaCl2 salt treatment avoids the safety risk associated with the storage and transport of large quantities of H2O2, providing a versatile and affordable treating method for complicated industrial effluents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and materials.

Crystalline layered sodium disilicate (Na2Si2O5, 95% purity) was obtained from Yousuo Chemical Technology Co., Qingdao, China, and used as received. 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP) and other analytical grade chemicals were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, China. A cast iron rod (10 cm2 working area) and a Ru0.3Ti0.7O2 (Ru—Ti) mesh (3.2 cm wide and 9 cm long) electrode were used as the anode and cathode, respectively, for the electrolysis. Additional information regarding the preparation of the stock solutions can be found in Text S1 in the Supporting Information (SI).

Experimental Procedures.

Electrolysis experiments were performed in a 200-ml jacketed beaker connected to a flowing liquid temperature controller set to 25 °C (see Figure S1a in the SI). The standard experimental procedure for the DAIE was as follows. A predetermined volume of SD stock solution (0.1 mol/L) was added to the reactor prefilled with the 2,4-DCP aqueous solution, and deionized water was then added to reach a final volume of 175 mL. One M H2SO4 and NaOH were used to adjust the pH of the solution if necessary. Prior to the electrolysis experiment, the iron anode was washed with 0.1 M H2SO4 and deionized water in sequence. Solution agitation was achieved via a magnetic stirrer with a constant speed of 300 rpm. A constant current of 10 mA was applied and O2 was fed to the reactor (at approximately 30 mL/min) during the electrolysis unless elsewhere noted. Approximately 1.5 mL of the solution was extracted to determine the 2,4-DCP concentration at predetermined time intervals. For the experiments with coagulation operation, CaO powder was added to the solution after electrolysis. After the addition of the CaO, the solution was stirred for 10 min, and then settled for clarification. The supernatant and precipitates after the CaO treatment were collected and analyzed. In addition to the single chamber reactor shown in SI Figure S1a, an electrochemical reactor with divided anode and cathode chambers was employed to evaluate the individual contributions of the anode and cathode (see Figure S1b, SI). To probe the mechanism of the oxidation reactions, degradation experiments other than DAIE were also performed, including one with SD, FeSO4 and dissolved oxygen (SD/Fe(II)/O2), and one with SD, FeSO4 and H2O2 (SD/Fe(II)/H2O2). More information concerning the experimental details can be found in Text S1 in the SI.

Analytical Methods and Characterization.

The turbidity of the solution during testing was measured by using a turbidity meter (HACH 2100PA). The total organic carbon (TOC) of the solution was measured via a Jena TOC analyzer (Elementar, Germany). The concentrations of the total dissolved As, Cu, and Si species in the solution were analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES, PerkinElmer). The concentrations of H2O2, Cl− and the dissolved iron species were analyzed via titanometry, silver nitrate titration and the phenanthroline method, respectively. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis was performed via a Bruker X-band A200 spectrometer using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin-trapping agent. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed with an AutoLab electrochemical workstation (PGSTAT302N, Metrohm, Switzerland), and glassy carbon, a platinum plate and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) were used as the working electrode, auxiliary electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The concentration of 2,4-DCP was measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography (SPD-15C, Shimadzu) equipped with a C18 analytical reversed-phase column. The mobile phase was a mixture of a methanol—water solution (70:30, v/v) with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. A GC—MS analysis was performed to determine the degradation intermediates of 2,4-DCP. The biotoxicity of the water sample after DAIE treatment was evaluated using an assay of soil dehydrogenase activity. Additional information concerning EPR, GC—MS, dehydrogenase activity assay, the characterization using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and the X-ray diffractometry (XRD) can be found in Text S1 in the SI.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Enhanced Degradation of 2,4-DCP in the Presence of Silicates and O2.

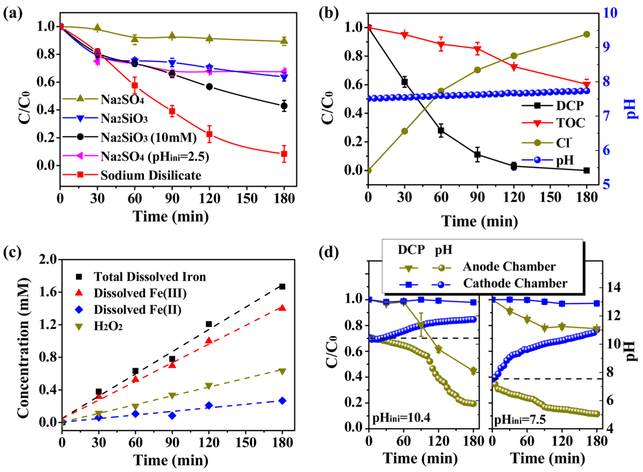

Figure 1a shows the degradation of 2,4-DCP via the iron electrolysis processes in different electrolytes. For the Na2SO4 electrolyte, only 10% of 2,4-DCP was removed after 180 min of electrolysis. The limited removal of 2,4-DCP was most likely due to the adsorption of hydroxy iron flocs at pH 7.5. When the Na2SO4 electrolyte was acidified to pHini 2.5, a “peroxi-coagulation” electro-Fenton reaction system is developed because electrolytic ferrous ions and electrogenerated H2O2 (derived from the reduction of O2 on the Ru—Ti cathode) were both available in the reaction solution. Unfortunately, compared to the carbon materials, which had high surface areas (e.g., vitreous carbon foam) and favorable electrocatalytic performances for the two-electron reduction of dioxygen,8,26,27 the Ru—Ti mesh electrode cannot provide sufficient H2O2 to contribute to the degradation of 2,4-DCP; therefore, only 33% of the 2,4-DCP was removed even in the acidified solution. By contrast, when silicates were used as electrolytes, the enhanced removal of 2,4-DCP was observed. In the presence of 5 mM and 10 mM Na2SiO3, the removal efficiencies of 2,4-DCP improved to 36% and 57%, respectively. Moreover, in the case of the DAIE system with 5 mM SD, 92% of the 2,4-DCP degraded within 180 min. Note that, iron precipitates did not form in the solutions with Na2SiO3 or SD, even at an initial pH of 7.5. Figure S2 in the SI shows that, the solution from the DAIE system was transparent and brown yellow, whereas the solution with the Na2SO4 electrolytes appeared to be turbid due to the presence of flocs. This observation indicates that disilicate ions can complex with Fe(II) and Fe(III) at pH ~ 7.5 to avoid the precipitation of iron species. Figure S3 in the SI further confirms the complexing capacity of disilicate ions on ferric ions, in which a quite low turbidity was always maintained in the SD solution compared to the increased turbidity with increasing pH in the Na2SO4 solution. In SI Figure S4, the disilicate ions also showed an ability to complex the ferrous/ferric ions derived from the corrosion of zerovalent iron in aqueous solutions. According to the above results, the improved removal of 2,4-DCP in the solution containing silicates is associated with the complexing effect from silicates, especially for the disilicate.

Figure 1b presents the degradation and mineralization of 2,4-DCP when a 20 mA current was applied to the DAIE system. As shown in the figure, 2,4-DCP was degraded completely within 180 min, and the mineralization efficiency, indicated by the decreased TOC values, reached up to 40%. Coupled with the gradual degradation of 2,4-DCP, the chlorine ions exhibited an increasing trend in the solution. The pH of the system was relatively stable in the electrolysis process, which can be ascribed to the buffering effect of disilicate.28 Furthermore, degradation intermediates of 2,4-DCP during the DAIE process were analyzed via GC—MS. The detected intermediates and degradation pathways are shown in Figure S5 in the SI. The biotoxicity analysis based on the inhibition of soil dehydrogenase activity showed that the water samples treated by the DAIE process demonstrated less biotoxicity with increasing treatment time (Figure S6 in the SI),29 indicating that 2,4-DCP was decomposed to less toxic compounds (e.g., tetrahydroxybenzene and 4-hydroxy 2-butenoic acid in SI Figure S5) during the DAIE treatment.

Figure 1.

(a) Degradation of 2,4-DCP via iron electrolysis processes in different electrolytes. (b) The degradation and mineralization of 2,4-DCP in a disilicate-assisted iron electrolysis (DAIE) system with a 20 mA current, and the changes in the pH and Cl− concentration over the electrolysis. (c) Dissolved H2O2, Fe(II) and Fe(III) species in the DAIE system. (d) Degradation of 2,4-DCP in a divided cell with disilicate electrolyte. Unless elsewise noted, the conditions of the electrolysis were [2,4-DCP]ini = 20 mg/L, I = 10 mA, pHini 7.5, [Na2SO4] = 5 mM, [Na2SiO3] = 5 mM and [SD] = 5 mM. The experiments shown in panels (a)–(c) were carried out in the electrolytic cell with a single chamber (SI Figure S1a), while the one shown in panel (d) was conducted with a divided electrolytic cell (SI Figure S1b).

Figure 1c demonstrates the concentrations of dissolved H2O2, Fe(II), Fe(III) and total dissolved iron over the course of the DAIE process. As can be seen, all the measured species show linearly increasing trends with electrolysis time. Importantly, the accumulative concentration of H2O2 was up to 0.6 mM, which means that the Fenton-oxidation process between the complexed ferrous ions and the in situ generated H2O2 may enhance the degradation of 2,4-DCP. By contrast, in the solution with 5 mM Na2SO4, no accumulative H2O2 or dissolved iron species were detected, as shown in Figure S7 in the SI. To further evaluate the roles of the iron anode and the Ru—Ti cathode, electrolysis was conducted in a divided electrochemical cell (SI Figure S1b). Figure 1d shows that the electro-reduction on the cathode is inoperative for the dechlorination of 2,4-DCP under the indicated pH values; however, the 2,4-DCP was effectively degraded in the anode chamber aerated with O2. Moreover, it can be seen that the removal of 2,4-DCP is dependent on the pH of the aqueous solution: an initial pH of 10.4 appeared to work better than an initial pH of 7.5. During the electrolysis process, the pH in the anode chamber gradually decreased, and an initial pH of 10.4 seems to provide a more reasonable average pH range for the oxidizing degradation of 2,4-DCP.

Electrolytic Fe(II) for H2O2 Production and the Fenton-Oxidation Process.

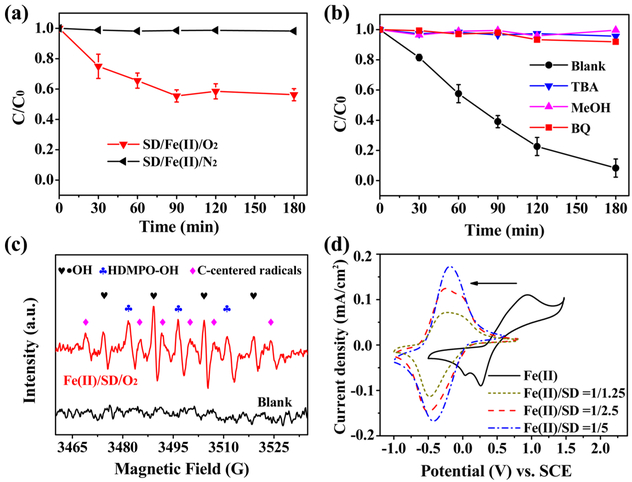

Complexed ferrous ions have been reported to activate dioxygen via two consecutive electron transfer steps to produce hydrogen peroxide,18,30,31 generating hydroxyl radicals to oxidize organic pollutants. The same mechanism may occur in the DAIE system. Experiments were performed to determine the role of O2 and to probe the reaction processes. As shown in Figure 2a, with SD and externally added ferrous iron (in the form of ferrous sulfate), the degradation of 2,4-DCP was absent under an anaerobic condition (N2), while a 40% removal efficiency could be achieved in an O2-bubbled solution. This observation confirms the participation of dioxygen in the degradation of 2,4-DCP. In Figure 2b, the ROS involved in the degradation process are further investigated by adding different types of radical inhibitors, that is, tert-butyl alcohol (TBA), methanol (MeOH) and benzoquinone (BQ), into the DAIE system. The complete inhibition by 0.1 M TBA and 0.5 M MeOH suggests that the hydroxyl radical was the dominating reactive species. Figure S5 in the SI reveals that the intermediates of the degraded 2,4-DCP in the DAIE system indeed included a series of compounds associated with the attack of hydroxyl radicals. Meanwhile, the removal efficiency sharply decreased to ~10% with 0.01 M BQ, indicating that the superoxide anion radical was also an important reactive species involved in the degradation. Figure 2c depicts the EPR signals obtained from the SD/Fe(II) aqueous solution aerated with O2. Characteristic signals of DMPO—OH adducts (with hyperfine splitting constants (hfsc) of αN = αH = 14.9 G), thus provide evidence of the presence of hydroxyl radicals in the process. In addition, HDMPO—OH (with hfsc of αN = 14.6 G and αH = 1.1 G)32–34 was observed, which reflects the further oxidation of DMPO—OH adducts by the oxidizing species (e.g., Fe(III) and •OH) in the Fenton system.33 Another DMPO-adduct (a carbon-centered radical, with hfsc of αN = 15.4 G and αH = 22.3 G) was also trapped. This adduct formed when DMPO further reacted with its decomposed intermediates, which were generated due to the attack of hydroxyl radicals.35–38

Figure 2.

(a) Degradation of 2,4-DCP with disilicate—Fe(II) complexes bubbled with O2 or N2. [2,4-DCP]ini = 20 mg/L, pHini 7.5, [SD] = 10 mM, and [Fe(II)]ini = 5 mM. (b) Effects of scavengers on the degradation of 2,4-DCP; pHini 7.5, I =10 mA, [2,4-DCP]ini = 20 mg/L, [SD] = 5 mM, [BQ] = 0.01M, [TBA] = 0.1 M, and [MeOH] = 0.5M. (c) EPR signals in the Fe(II)/SD aqueous solution. (d) CV of the ferrous ions in the presence of different amounts of SD (50 mV/s scan rate, 2 mM ferrous iron).

Figure 2d depicts the CV curves of ferrous ions in the presence and absence of SD. In the SD-free solution (pH 3.98), the anodic peak centered at 0.94 V vs SCE is ascribed to the transformation from Fe(II) to Fe(III), and the cathodic peaks at 0.26 and 0.04 V are associated with the Fe(III)-hydroxy complexes. Fe3(OH)45+ and Fe2(OH)24+ both form at pH 4 (see the simulation in SI Figure S8), therefore two cathodic peaks are observed. For the disilicate—Fe(II) complexes, the oxidative peak of Fe(II) and the reductive peak of Fe(III) were negatively shifted to −0.25 V and −0.5 V, respectively, vs SCE. Moreover, the intensities of the peaks increased with the concentration of SD (2–10 mM in Figure 2d) and did not significantly decay within the pH range from 5 to 7.5 (see SI Figure S9). These observations suggest that the disilicate ions coordinated with the ferrous/ferric ions and decrease the redox potential of Fe(II)/Fe(III) couple. The disilicate ions provide negative oxygen donor groups that can complex the positively charged ferrous ions, as illustrated by Figure S10 in the SI, therefore, providing an enhanced reducing capability for the ferrous ions to activate the dioxygen. According to the above results, the reactions in the DAIE system are shown as follows.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Ferrous ions are generated from the sacrificial iron anode (eq 3) and are immediately complexed with disilicate ions (eq 4). Due to its much lower oxidation potential than the aquacomplexed potential, the disilicate—Fe(II) complex can activate O2 via the single electron transfer process, producing superoxide anion radicals (eq 5) and H2O2 (eq 6). The resulting H2O2 further reacts with the disilicate—Fe(II) complex (eq 7), producing powerful hydroxyl radicals to degrade 2,4-DCP. In the degradation experiment using externally added H2O2 (see SI Figure S11), the quick degradation of 2,4-DCP confirms that H2O2 is capable of activating the disilicate—Fe(II) complexes to trigger the Fenton reaction. Note that, in the DAIE system, the reduction of disilicate—Fe(III) on the cathode may contribute to the regeneration of disilicate—Fe(II); therefore, employing a cathode with high surface area may further improve the oxidation efficiency of the DAIE process.

Effects of pH, Current, and Coexisting Anions.

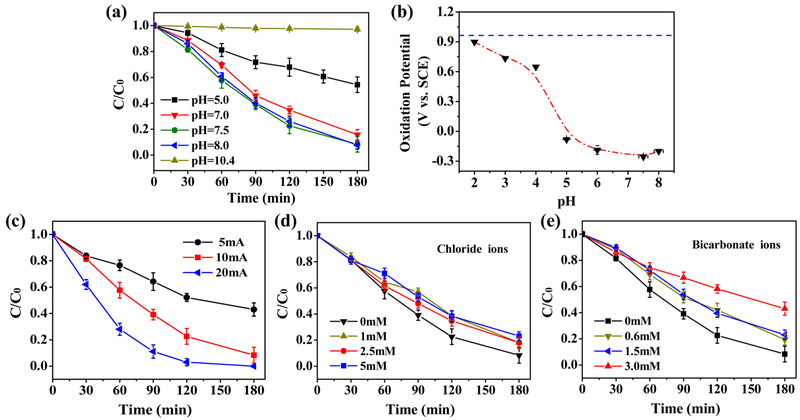

The removal of 2,4-DCP in the DAIE system at different pH is shown in Figure 3a. It can be seen that a more efficient degradation of 2,4-DCP was achieved when the initial pH was nearly neutral (pH 7—8). When the reaction solution was strongly acidic or alkaline, the degradation of 2,4-DCP was significantly retarded (see the rate constants shown in SI Figure S12). The optimal pH obtained from the DAIE process is very different from that of the traditional Fenton process, in which pH 3 is preferable.39,40 This observation can be explained by the effect of pH on the complexation of ferrous ions by disilicate. Efficient complexation is obtained within a near neutral pH range, and a strong acidic or alkaline environment will cause the disilicate complexation to fail. Figure S13 in the SI depicts the CVs of the ferrous iron-containing SD solutions at different pH values. Both the oxidative peaks of the ferrous species and the reductive peaks of the ferric species can be observed from the CV plots; however, the potentials where the peak values appeared are very different. For the oxidation peak, which can be thought of as the indicator of the reducing capacity of the ferrous species, pH values lower than 4 allow for the existence of free ferrous ions (see the simulation in SI Figure S8); therefore, the current peaks occurred at relatively positive potentials (see Figure 3b). When the ferrous ions were effectively complexed with disilicate ions within the pH range from 5 to 8, the oxidation peaks were seen at potentials lower than 0 V vs SCE, and the most negative oxidation potential was achieved at pH 7.5. Our results suggest that the disilicate-complexed ferrous species in the DAIE system indeed produced much more H2O2 at pH 7.5 relative to its production at pH 5 (see SI Figure S14), therefore explaining the higher removal efficiency at pH 7.5. Note that, when the solution was too alkaline, precipitates formed on the anode or in the aqueous solution, and no 2,4-DCP was degraded.

Figure 3.

(a) Degradation of 2,4-DCP at different initial pH values for [2,4-DCP] = 20 mg/L, I = 10 mA and [SD] = 5 mM. (b) The oxidation potentials of ferrous iron in the presence of disilicate at different pH for [SD] = 5 mM and [Fe(II)] = 2 mM; the blue dash line indicates the oxidation potential of free ferrous ions at pH 4. Effects of (c) the electrical current, (d) chloride anions and (e) bicarbonate anions on the degradation of 2,4-DCP for [2,4-DCP]ini = 20 mg/L, pHini 7.5, and [SD] = 5 mM. The current was 10 mA if not otherwise specified.

Figure 3c shows the removal trends for 2,4-DCP in a DAIE system with different applied currents. It can be seen that the degradation rates and efficiencies were significantly improved under higher current intensities. The observed rate constants for 2,4-DCP degradation were improved from 0.004 min−1 to 0.026 min−1 when the current was increased from 5 mA to 20 mA (see SI Figure S15). The applied current is the driving force for the production of ferrous complexes. Obviously, higher applied currents increase the quantities of ferrous species and H2O2 (see the monitored dissolved iron species and H2O2 in SI Figure S16), therefore increasing the removal efficiencies of 2,4-DCP. This observation suggests that the oxidizing capacity of the DAIE can be manipulated by varying the applied current. Figure 3d and e present the effects of the coexisting anions on the degradation of 2,4-DCP. Both chloride and bicarbonate ions inhibit the degradation of 2,4-DCP, and the inhibitory effect is more evident at higher concentrations. The presence of chloride and bicarbonate can consume hydroxyl radicals and form less reactive inorganic radicals, such as HClO•−,Cl•− and 41 thereby decreasing the oxidation efficiency of 2,4-DCP. In addition, the interaction of chloride ions with ferrous iron (e.g., the formation of FeCl+ and ) may decrease the complexation between disilicate ions and ferrous ions.42

CaO Treatment to Remove Disilicate Complexes and Toxic Metals.

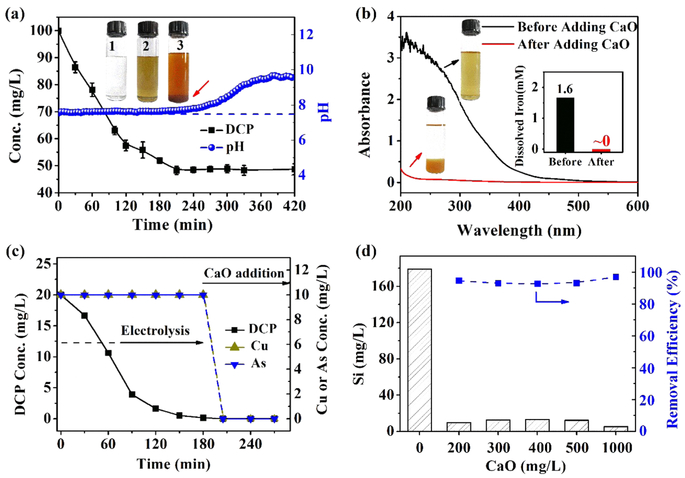

Figure 4a shows the 2,4-DCP degradation and pH variation in a DAIE process lasting for 420 min. Approximately 53% of the 2,4-DCP was degraded within 240 min; subsequently, the removal of 2,4-DCP was inhibited due to the rapid increase in the pH. Over the 420 min of electrolysis, even though the cell voltage was stable (see SI Figure S17), the aqueous solution changed from colorless to light yellow and then to brownish yellow (Figure 4a) due to the accumulation of ferric ions and the increasing pH. Therefore, the disilicate—iron complexes in the reaction system need to be removed. We found that adding CaO or CaCl2 can achieve an effective decoloration of the reaction solution after electrolysis (Figure 4b) and that the dissolved iron species were completely removed from the solution by precipitation (the inset in Figure 4b). The addition of CaO can also be used to precipitate the heavy metals in the solution. For an aqueous solution containing both 2,4-DCP and heavy metal ions (e.g., anionic AsO33− and cationic Cu2+), a combination of the DAIE process and the CaO treatment, as shown in Figure 4c, can completely eliminate the 2,4-DCP and the metal ions including As(III) and Cu(II) (<0.1 mg/L).

Figure 4.

(a) Degradation of 2,4-DCP and the variation of pH over a DAIE process lasting for 420 min for [2,4-DCP]ini = 100 mg/L, I = 20 mA, pHini 7.5 and [SD] = 5 mM. The insets 1, 2, and 3 show the reaction solutions at 0, 180, and 420 min, respectively. (b) UV–vis spectra of the reaction solutions before and after the addition of 200 mg/L CaO. The inset shows the concentrations of dissolved iron in the solution before and after adding CaO. (c) Removal of the wastewater containing 2,4-DCP, AsO33− and Cu2+ with a combination of DAIE and the addition of CaO for [2,4-DCP]ini = 20 mg/L, [Cu]ini = [As]ini = 10 mg/L, I = 20 mA, pHini 7.5, and [SD] = 5 mM. (d) Removal of disilicate via the addition of CaO. The solutions for CaO treatment were obtained after the DAIE treatment ([SD] = 3.2 mM).

In addition to the removal of iron species and heavy metals, disilicate can also be significantly removed via the addition of CaO. Figure 4d demonstrates that a dosage of 200 mg/L CaO was sufficient to remove more than 90% of the dissolved silicon. The XRD and XPS analyses reveal that the sediments are amorphous solids containing both CaSi2O5 and ferric hydroxides (see SI Figure S18). When CaO was added to the reaction solution in the DAIE process, a dissociation of the disilicate—iron complexes occurred: the calcium ions combined with disilicate ions to form undissolved CaSi2O5 and iron hydroxides were simultaneously generated due to the neutral/alkaline pH. Note that SD cannot effectively complex the calcium ions; therefore, the dissolved calcium species, including CaO and CaCl2, can be used to remove the disilicate from the solution via the sedimentation process. As a result, the iron hydroxides and calcium silicate both serve as the coagulant agents, contributing to the removal of contaminants. Figure S19 in the SI shows that the sediment had a sludge volume index of 167.7 mL/g, suggesting a superior settleability.

Implications for Wastewater Treatment.

This study demonstrates for the first time the activation of O2 via ferrous complexes using inorganic ligand disilicate. A combination of DAIE and CaO treatment is proven to effectively treat wastewater containing organics and heavy metals (e.g., electroplating and surface treating effluents). As illustrated in Scheme 1, the iron electrolysis is successfully modified to an oxidizing DAIE process that can generate H2O2 in situ via electrolytic ferrous ions in the presence of disilicate and O2. The Fenton-oxidation process subsequently degraded the organic pollutants via hydroxyl radicals. In comparison to the classic Fenton process, the DAIE process does not require the laborious addition of H2O2 and acidifying agents: it works effectively at pH values near 7, and the disilicate provides a relatively stable pH via its buffering effect. More importantly, the different complexing capacities of disilicate for ferrous/ferric ions and calcium ions can be used to remove the disilicate if the presence of disilicate is not desirable. The CaO/CaCl2 treatment can effectively eliminate the dissolved iron species, the disilicate and the heavy metal pollutants via the coprecipitation process. Compared to the previously reported organic and phosphoric chelators/ligands, the disilicate ligand is environmentally friendly and does not lead to secondary pollution, therefore paving the way for the practical application of O2 activation in wastewater treatment. Broadly speaking, disilicate salts can be used in conjunction with different iron species such as zerovalent iron, ferrous salts, and electrolytic ferrous ions for different advanced oxidation/coagulation applications.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the Mechanism for Combining Disilicate-Assisted Iron Electrolysis (DAIE) and CaO/CaCl2 Treatment for Sequential Fenton- Oxidation and Coagulation

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51278386, 21406171), the special grant for technological innovation (2016ACA162) from Hubei Province, and the seed grant from the Wuhan university (2042016kf1178).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.7b01184.

Additional details are presented about supplementary text, figures, and tables (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Martínez-Huitle CA; Rodrigo MA; Sirés I; Scialdone O Single and coupled electrochemical processes and reactors for the abatement of organic water pollutants: a critical review. Chem. Rev 2015, 115 (24), 13362–13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Martínez-Huitle CA; Brillas E Decontamination of wastewaters containing synthetic organic dyes by electrochemical methods: a general review. Appl. Catal., B 2009, 87 (3), 105–145. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Brillas E; Sirés I; Oturan MA Electro-Fenton process and related electrochemical technologies based on Fenton’s reaction chemistry. Chem. Rev 2009, 109 (12), 6570–6631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Brillas E; Mur E; Sauleda R; Sanchez L; Peral J; Domènech X; Casado J Aniline mineralization by AOP’s: anodic oxidation, photocatalysis, electro-Fenton and photoelectro-Fenton processes. Appl. Catal., B 1998, 16 (1), 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhao B; Li X; Wang P 2, 4-Dichlorophenol Degradation by an Integrated Process: Photoelectrocatalytic Oxidation and E-Fenton Oxidation. Photochem. Photobiol 2007, 83 (3), 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Fan Y; Ai Z; Zhang L Design of an electro-Fenton system with a novel sandwich film cathode for wastewater treatment. J. Hazard. Mater 2010, 176 (1), 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pimentel M; Oturan N; Dezotti M; Oturan MA Phenol degradation by advanced electrochemical oxidation process electro-Fenton using a carbon felt cathode. Appl. Catal., B 2008, 83 (1), 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Liu Y; Chen S; Quan X; Yu H; Zhao H; Zhang Y Efficient mineralization of perfluorooctanoate by electro-fenton with H2O2 electro-generated on hierarchically porous carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49 (22), 13528–13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zhao H; Wang Y; Wang Y; Cao T; Zhao G Electro-Fenton oxidation of pesticides with a novel Fe3O4@ Fe2O3/activated carbon aerogel cathode: High activity, wide pH range and catalytic mechanism. Appl. Catal., B 2012, 125, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Brillas E; Casado J Aniline degradation by Electro-Fenton® and peroxi-coagulation processes using a flow reactor for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2002, 47 (3), 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kobya M; Can OT; Bayramoglu M Treatment of textile wastewaters by electrocoagulation using iron and aluminum electrodes. J. Hazard. Mater 2003, 100 (1), 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wang Q; Scherer EM; Lemley AT Metribuzin degradation by membrane anodic Fenton treatment and its interaction with ferric ion. Environ. Sci. Technol 2004, 38 (4), 1221–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Romero V; Acevedo S; Marco P; Giménez J; Esplugas S Enhancement of Fenton and photo-Fenton processes at initial circumneutral pH for the degradation of the β-blocker metoprolol. Water Res. 2016, 88, 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).ElShafei GM; Yehia F; Dimitry O; Badawi A; Eshaq G Degradation of nitrobenzene at near neutral pH using Fe2+—glutamate complex as a homogeneous Fenton catalyst. Appl. Catal., B 2010, 99 (1), 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lipczynska-Kochany E; Kochany J Effect of humic substances on the Fenton treatment of wastewater at acidic and neutral pH. Chemosphere 2008, 73 (5), 745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Huang W; Brigante M; Wu F; Mousty C; Hanna K; Mailhot G Assessment of the Fe (III)—EDDS complex in Fenton-like processes: from the radical formation to the degradation of bisphenol A. Environ. Sci. Technol 2013, 47 (4), 1952–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wang L; Cao M; Ai Z; Zhang L Dramatically enhanced aerobic atrazine degradation with Fe@Fe2O3 core—shell nanowires by tetrapolyphosphate. Environ. Sci. Technol 2014, 48 (6), 3354–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wang L; Cao M; Ai Z; Zhang L Design of a highly efficient and wide pH electro-Fenton oxidation system with molecular oxygen activated by ferrous—tetrapolyphosphate complex. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49 (5), 3032–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ai Z; Gao Z; Zhang L; He W; Yin JJ Core—shell structure dependent reactivity of Fe@Fe2O3 nanowires on aerobic degradation of 4-chlorophenol. Environ. Sci. Technol 2013, 47 (10), 5344–5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bayr H Reactive oxygen species. Crit. Care Med 2005, 33 (12), S498–S501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Keenan CR; Sedlak DL Ligand-enhanced reactive oxidant generation by nanoparticulate zero-valent iron and oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol 2008, 42 (18), 6936–6941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Biaglow JE; Kachur AV The generation of hydroxyl radicals in the reaction of molecular oxygen with polyphosphate complexes of ferrous ion. Radiat. Res 1997, 148 (2), 181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Li J; Ai Z; Zhang L Design of a neutral electro-Fenton system with Fe@Fe2O3/ACF composite cathode for wastewater treatment. J. Hazard. Mater 2009, 164 (1), 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Noradoun CE; Cheng IF EDTA degradation induced by oxygen activation in a zerovalent iron/air/water system. Environ. Sci. Technol 2005, 39 (18), 7158–7163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Biaglow JE; Kachur AV The generation of hydroxyl radicals in the reaction of molecular oxygen with polyphosphate complexes of ferrous ion. Radiat. Res 1997, 148 (2), 181–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Dirany A; Sirés I; Oturan N; Özcan A; Oturan MA Electrochemical treatment of the antibiotic sulfachloropyridazine: kinetics, reaction pathways, and toxicity evolution. Environ. Sci. Technol 2012, 46 (7), 4074–4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Boye B; Dieng MM; Brillas E Degradation of herbicide 4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid by advanced electrochemical oxidation methods. Environ. Sci. Technol 2002, 36 (13), 3030–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Coker EN; Rees LV Solubility and water-softening properties of a crystalline layered sodium silicate, SKS-6. J. Mater. Chem 1993, 3 (5), 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yang N; Cui J; Zhang L; Xiao W; Alshawabkeh AN; Mao X Iron electrolysis-assisted peroxymonosulfate chemical oxidation for the remediation of chlorophenol-contaminated groundwater. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol 2016, 91 (4), 938–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Jones AM; Griffin PJ; Waite TD Ferrous iron oxidation by molecular oxygen under acidic conditions: The effect of citrate, EDTAand fulvic acid. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 160, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wang L; Wang F; Li P; Zhang L Ferrous—tetrapolyphosphate complex induced dioxygen activation for toxic organic pollutants degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol 2013, 120, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Makino K; Hagi A; Ide H; Murakami A; Nishi M Mechanistic studies on the formation of aminoxyl radicals from 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide in Fenton systems. Characterization of key precursors giving rise to background ESR signals. Can. J. Chem 1992, 70 (11), 2818–2827. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Fontmorin J; Castillo RB; Tang W; Sillanpää M Stability of 5, 5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide as a spin-trap for quantification of hydroxyl radicals in processes based on Fenton reaction. Water Res. 2016, 99, 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Velasco LF; Carmona RJ; Matos J; Ania CO Performance of activated carbons in consecutive phenol photooxidation cycles. Carbon 2014, 73, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Luo M; Lv L; Deng G; Yao W; Ruan Y; Li X; Xu A The mechanism of bound hydroxyl radical formation and degradation pathway of Acid Orange II in Fenton-like Co2+-HCO3− system. Appl. Catal. A 2014, 469, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sinha BK; Leinisch F; Bhattacharjee S; Mason RP DNA cleavage and detection of DNA radicals formed from hydralazine and copper (II) by ESR and immuno-spin trapping. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2014, 27 (4), 674–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Finkelstein E; Rosen GM; Rauckman EJ; Paxton J Spin trapping of superoxide. Chem. Informationsdienst 1979, 16 (2), 676–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Dong G; Ai Z; Zhang L Total aerobic destruction of azo contaminants with nanoscale zero-valent copper at neutral pH: Promotion effect of in-situ generated carbon center radicals. Water Res. 2014, 66, 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ghoneim MM; El-Desoky HS; Zidan NM Electro-Fenton oxidation of Sunset Yellow FCF azo-dye in aqueous solutions. Desalination 2011, 274 (1), 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wang CT; Hu JL; Chou WL; Kuo YM Removal of color from real dyeing wastewater by Electro-Fenton technology using a three-dimensional graphite cathode. J. Hazard. Mater 2008, 152 (2), 601–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kiwi J; Lopez A; Nadtochenko V Mechanism and kinetics of the OH-radical intervention during Fenton oxidation in the presence of a significant amount of radical scavenger (Cl−). Environ. Sci. Technol 2000, 34 (11), 2162–2168. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lu MC; Chang YF; Chen IM; Huang YY Effect of chloride ions on the oxidation of aniline by Fenton’s reagent. J. Environ. Manage 2005, 75 (2), 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.