Abstract

Background:

Perceived to be distinct, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can co-exist and potentially have a worse prognosis than the separate diseases. Yet, little is known about the exact prevalence and the characteristics of the Asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in the U.S. population.

Aims:

To determine ACO prevalence in the U.S., identify ACO predictors, examine ACO association with asthma and COPD severity, and describe distinctive spirometry and laboratory features of ACO.

Methods:

Data on adult participants to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys conducted from 2007 to 2012 was analyzed. ACO was defined as current asthma and post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) <0.7.

Results:

Overall, 7,570 participants representing 98.58 million Americans were included in our study. From 2007 to 2012, the crude and age-standardized ACO prevalence were respectively 0.96% (95% CI: 0.65%−1.26%) and 1.05% (0.74%−1.37%). In asthma, ACO predictors included older age, male gender, and smoking. In COPD, ACO predictors were non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity and obesity. ACO was associated with increased ER visits for asthma (OR=3.46, 95% CI: 1.48–8.06]) and oxygen therapy in COPD (OR=11.17, 95% CI: 5.17–24.12]). In spirometry, FEV1 and peak expiratory flow were lower in ACO than in asthma or COPD alone.

Conclusion:

Age-adjusted prevalence of ACO in the U.S. was 1.05% in 2007–2012, representing 0.94 (95% CI: 0.62–1.26) million Americans. It is much lower than previously reported. The overlap was associated with higher asthma and COPD severity as well as decreased lung function compared to COPD or asthma alone.

Keywords: Asthma, COPD, Asthma-COPD overlap, ACO, ACOS, Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive lung diseases characterized by airflow limitation include asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These two conditions have been traditionally perceived to be different in their pathogenesis, clinical features, and therapeutic approaches (1). Asthma is characterized by airway inflammation, smooth muscle contraction and mucus overproduction leading to reversible airway obstruction and airway wall remodeling (2). Airway inflammation in asthma is classically described to be eosinophilic, with T-helper-2 (Th2) lymphocytes leading to mast cell degranulation, histamine release, and bronchoconstriction after allergen exposure (3). Asthma typically develops at an early age, usually responds to anti-inflammatory and beta2-agonist medications, and thus has a good prognosis (4, 5). COPD on the other hand is mainly tobacco-related, although air pollution and occupational exposures might play a role in its development (3, 6). It is characterized by progressive, non-reversible airflow limitation associated with neutrophilic airway inflammation and/or emphysematous parenchyma marked by loss of alveolar elastic recoil, lung hyperinflation, and gas diffusion abnormalities (3). COPD might not respond well to corticosteroid treatment depending on the levels of blood eosinophils; hence prognosis tends to be poor, often leading to chronic respiratory insufficiency or failure (4, 5).

Despite the apparent contrast, both can co-exist in the same patient, posing diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. This entity has been recognized by a joint committee of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) as the “asthma-COPD overlap” (ACO) syndrome, but whether to call the overlap a syndrome is still controversial (7, 8). Current literature suggests that affected patients are inclined to faster disease progression, poorer quality of life, and more co-morbidities than those with either asthma or COPD alone (9, 10). Yet, to date the exact prevalence of ACO in the U.S. is unknown. Previous studies have tried to examine ACO prevalence in the U.S. using self-reported COPD, although this definition is inaccurate. According to international guidelines, COPD is diagnosed only when airflow obstruction is documented by spirometry (11, 12, 13). The only U.S. study that used spirometry defined COPD as Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1) / Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) < 70% pre-bronchodilator administration, instead of the post-bronchodilator as suggested by the GOLD (14). Furthermore, ACO features are yet to be fully described and there is a need to identify biomarkers that differentiate ACO from asthma and COPD (15). Therefore, in the present study, we used a sample representative of the US adult population to 1) determine ACO prevalence in the US using a more adequate definition of COPD, 2) identify ACO predictors, 3) examine ACO association with asthma and COPD severity, and 4) describe distinctive spirometry and laboratory features of ACO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and study design

We used data from the NHANES conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NHANES is a continuous cross-sectional survey of the US non-institutionalized civilian population, selected using a complex multistage sampling design to derive a representative sample of the US population. We combined two-year data cycles from 2007 to 2012, following National Center for Health Statistics recommendations. Of 13,387 NHANES participants of aged 40 years and older who underwent spirometry, 7,570 (93.1 %) had data on asthma and were included in our study.

NHANES protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the NCHS and CDC and informed consent was obtained from all participants (IRB approval available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm). Details on NHANES procedures and methods are available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/survey_methods.htm.

Spirometry and ACOS Definition

Eligible survey participants aged 40–79 years underwent baseline spirometry, including FVC; FEV1; Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF); and Forced Expiratory Flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25–75). Examinees with baseline FEV1/FVC <70% or <Lower Limit of Normal (LLN) for his/her age, sex, weight, height, and race/ethnicity were considered for bronchodilator (albuterol) administration and repeat spirometry. COPD was defined as post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7 (15). Because participants receiving oxygen therapy during the day were excluded from spirometry testing for safety reasons, we classified those who reported COPD diagnosis (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) and were currently taking supplemental oxygen during the day as having COPD.

Current asthma was defined as a positive response to the questions: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told {you/SP} that {you have/s/he/SP has} asthma?” and “{Do you/Does SP} still have asthma?” ACO was defined by the co-existence of both asthma and COPD.

Eosinophil counts and Exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

Complete blood count was assessed with the Beckman Coulter method and white blood cell differential used VCS technology. Exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was measured using a portable FDA-approved analyzer (Aerocrine NIOX MINO®, Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden).

Asthma severity and daytime oxygen therapy

NHANES participants with asthma were additionally asked about asthma exacerbations and emergency room (ER) visits for asthma in the past year. COPD participants were also asked about the use supplemental oxygen during the day.

Demographics and comorbidities

The NHANES also collected data on age, gender, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio (PIR), education level, cigarette smoking, body mass index (BMI), and medical conditions or comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke, and congestive heart failure [CHF]).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed by asthma, COPD, as well as ACO status and the chi-square test was used to calculate P-values for differences in group proportions. Crude and age-adjusted ACO prevalence were calculated for the general population and in the different subgroups. The age-standardization was done to allow comparisons independent of age using the following age groups and weights calculated from the 2010 census data (40–59 years, weight, 0.59085; and ≥60 years, weight, 0.40915). Logistic regression analysis was used to identify ACO predictors and examine ACO association with asthma severity and oxygen therapy in COPD. We compared the mean log10-transformed estimates of spirometry and laboratory parameters in ACO versus asthma or COPD alone using an independent t-test and the geometric means were reported after back transformation (exponentiation) of the arithmetic mean of log-transformed estimates. The analyses were performed in SAS (Version 9.4) and STATA (Version 14). The sampling design complexity was accounted for using sampling weights (WTINT2YR) and survey commands. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

RESULTS

Description of the study population

Study sample consisted of 7,570 participants. Table 1 provides a description of our study population. Briefly, compared to participant with no asthma/COPD, participants with ACO were more likely to be older, non-Hispanic White or Black, to have smoked cigarettes, or to have comorbidities (diabetes, history of MI or stroke, or CHF). Compared with participants with asthma alone, those with ACO tended to be older, to be of male gender, to have smoked cigarettes, and to have a history of MI, stoke or CHF. Compared to COPD alone, ACO participants were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic, to be obese, or have comorbidities (diabetes, history of MI or stroke, or CHF) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of study participants by asthma COPD and overlap status, NHANES 2007–2012 (N = 7,570)

| Characteristics | ACO | No asthma or COPD | PACO vs. No asthma or COPD | Asthma alone | PACO vs. Asthma | COPD alone | PACO vs. COPD | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (SE), years | 58.38 (2.03) | 52.00 (0.26) | < 0.0001 | 53.58 (1.16) | < 0.0001 | 58.11 (0.85) | 0.49 | 52.58 (0.28) |

| Gender, % | 0.093 | < 0.0001 | 0.26 | |||||

| Men | 60.1 | 46.9 | 31.1 | 68.4 | 47.6 | |||

| Women | 39.9 | 53.1 | 68.9 | 31.6 | 52.4 | |||

| Race/ethnicity, % | 0.040 | 0.58 | 0.0031 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 74.0 | 70.7 | 74.8 | 85.7 | 72.0 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 16.0 | 10.9 | 12.6 | 6.5 | 10.8 | |||

| Hispanics | 4.3 | 12.1 | 7.0 | 2.6 | 11.1 | |||

| Other | 5.7 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 6.1 | |||

| PIR, % | 0.088 | 0.26 | 0.072 | |||||

| ≤ 1 | 17.7 | 9.2 | 14.7 | 6.9 | 9.5 | |||

| > 1 | 71.2 | 83.7 | 80.1 | 83.8 | 83.4 | |||

| Missing | 11.1 | 7.6 | 5.2 | 9.2 | 7.1 | |||

| Education level, % | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.78 | |||||

| High School | 16.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.8 | 17.1 | |||

| High school diploma/some college | 51.8 | 51.0 | 52.4 | 55.1 | 51.4 | |||

| College graduate or above | 32.2 | 32.0 | 30.6 | 27.1 | 31.5 | |||

| BMI, % | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.006 | |||||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 22.2 | 25.0 | 16.1 | 33.4 | 25.0 | |||

| Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) | 28.6 | 36.3 | 31.6 | 39.4 | 36.2 | |||

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 49.1 | 38.7 | 52.3 | 27.2 | 38.8 | |||

| Cigarettes smoking, % | 0.001 | 0.0013 | 0.67 | |||||

| Non smoker | 26.0 | 57.0 | 55.8 | 22.2 | 54.4 | |||

| Current and Past Smoker | 74.0 | 43.0 | 44.2 | 77.8 | 45.6 | |||

| Diabetes, % | 25.6 | 13.6 | 0.0037 | 23.2 | 0.60 | 11.2 | 0.0005 | 14.1 |

| Hypertension, % | 48.4 | 42.1 | 0.40 | 52.2 | 0.68 | 53.5 | 0.85 | 43.0 |

| Had MI or stroke, % | 24.6 | 4.4 | < 0.0001 | 7.9 | 0.0006 | 8.6 | 0.0001 | 5.1 |

| Had congestive heart failure, % | 15.5 | 1.6 | < 0.0001 | 4.0 | 0.0036 | 3.9 | 0.0006 | 2.0 |

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ACO, asthma COPD overlap; PIR, Poverty Income Ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index; MI, Myocardial Infarction; CHF, Congestive Heart Failure; SE, Standard Error. P values for overall differences in prevalences by strata calculated using F-test.

ACO Prevalence

The crude overall ACO prevalence (95% CI) after applying survey design and sampling weights was 0.96% (0.65%−1.26%). Higher crude ACO prevalence estimates were seen in participants 60 years and older (1.60% [1.06%−2.14%]), in non-Hispanic Blacks (1.42% [0.85%−1.98%]), in participants with a low socioeconomic status (PIR ≤1) (1.78% [0.95%−2.62%]), in past and current cigarette smokers (1.55% [0.95%−2.15%]), in participants with comorbidities (1.74% [1.01%−2.45%] in participants with diabetes, 4.62% [1.86%−7.39%] in participants with a history of MI or stroke, and 7.44% [1.72%−13.16%] in participants with CHF) (Table 2). Among participants with COPD, crude ACO prevalence was 12.59% [8.87%−16.31%] and among those with asthma, it was 14.60% [10.8%−18.36%].

Table 2:

Crude and age-adjusted ACO prevalence, NHANES 2007–2012 (N = 7,570)

| Characteristics | Crude ACO Prevalence | Age-adjusted ACO Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | P | Prevalence (%) | P | |

| Overall Prevalence | 0.96 (0.65, 1.26) | 1.05 (0.74, 1.37) | ||

| Age | 0.0021 | |||

| 40 – 59 years | 0.68 (0.36, 0.99) | - | ||

| 60+ years | 1.60 (1.06, 2.14) | - | ||

| Gender | 0.13 | 0.11 | ||

| Men | 1.21 (0.67, 1.74) | 1.35 (0.77,1.93) | ||

| Women | 0.73 (0.41, 1.04) | 0.80 (0.46, 1.13) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.0044 | 0.14 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 0.98 (0.59, 1.37) | 1.05 (0.65, 1.46) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 1.42 (0.85, 1.98) | 1.52 (0.97, 2.08) | ||

| Hispanics | 0.37 (0.01, 0.66) | 0.60 (0.14, 1.06) | ||

| Other | 0.88 (0.23, 1.52) | 1.11 (0.27, 1.96) | ||

| PIR | 0.029 | 0.017 | ||

| ≤ 1 | 1.78 (0.95, 2.62) | 2.18 (1.21, 3.13) | ||

| > 1 | 0.82 (0.52, 1.11) | 0.97 (0.52, 1.43) | ||

| Education level | 0.97 | 0.98 | ||

| High School | 0.90 (0.40, 1.39) | 1.00 (0.48, 1.52) | ||

| High School diploma/some college | 0.96 (0.63, 1.30) | 1.05 (0.70, 1.40) | ||

| College graduate or above | 0.98 (0.24, 1.71) | 1.08 (0.29, 1.86) | ||

| BMI | 0.36 | 0.36 | ||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 0.85 (0.36, 1.34) | 1.03 (0.42, 1.64) | ||

| Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) | 0.76 (0.40, 1.12) | 0.83 (0.43, 1.22) | ||

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 1.21 (0.63, 1.80) | 1.29 (0.70, 1.88) | ||

| Cigarettes smoking | 0.0014 | 0.018 | ||

| Never smoked | 0.46 (0.21, 0.70) | 0.53 (0.24, 0.81) | ||

| Past and current smokers | 1.55 (0.95, 2.15) | 2.04 (0.53, 3.55) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.019 | 0.045 | ||

| No | 0.83 (0.51, 1.14) | 0.92 (0.58, 1.26) | ||

| Yes | 1.74 (1.01, 2.45) | 1.65 (0.96, 2.34) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.53 | 0.77 | ||

| No | 0.87 (0.45, 1.28) | 1.17 (0.57, 1.77) | ||

| Yes | 1.08 (0.58, 1.57) | 1.05 (0.55, 1.56) | ||

| Had MI or stroke | 0.0065 | 0.019 | ||

| No | 0.76 (0.51, 1.01) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.08) | ||

| Yes | 4.62 (1.86, 7.39) | 4.13 (1.37, 6.89) | ||

| Had congestive heart failure | 0.024 | 0.045 | ||

| No | 0.82 (0.38, 0.74) | 0.89 (060, 1.19) | ||

| Yes | 7.44 (1.72, 13.16) | 6.39 (1.05, 11.73) | ||

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ACO, asthma COPD overlap; PIR, Poverty Income Ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index; MI, Myocardial Infarction; CHF, Congestive Heart Failure. P values for overall differences in prevalences by strata calculated using F-test.

After age-standardization, overall ACO prevalence was 1.05% [0.74%−1.37%]. It was higher in participants with PIR ≤1 (2.18% [1.21%−3.13%], past cigarette and current cigarette smokers (2.04% [0.53%−3.55%]), those with diabetes (1.65% [0.96%−2.34%]), history of MI or stroke (4.13% [1.37%−6.89%]) or with CHF (6.39% [1.05%−11.73%] (Table 2). Among participants with COPD, age-standardized ACO prevalence was 12.49% [8.67%−16.31%] and among those with asthma, it was 15.34% [11.75%−18.93%].

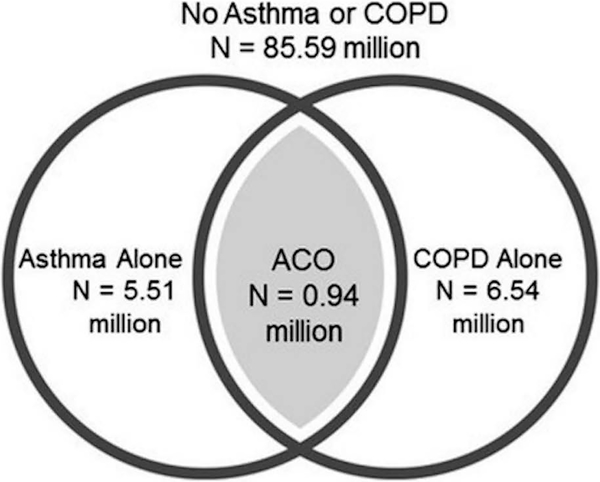

Generalized to the U.S. population, our sample represented about 98.58 million Americans and our results suggest that among them, 0.94 (0.62–1.26) million have ACO (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Venn diagram for the overlap between asthma and COPD

Factors associated with ACO

Among subjects with asthma, age (odds ratio [OR] 1.09 [95% CI 1.05–1.13]) and cigarette smoking (OR: 3.18 [1.48–6.85]) were predictors of higher ACO prevalence, while female gender (OR: 0.26 [0.13–0.53]) was a predictor of lower ACO prevalence.

Among participants with COPD, non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (OR: 2.65 [1.22–5.72]), obesity (OR: 2.99 [1.14–7.80]) and a history of MI or stroke (OR: 2.65 [1.10–6.36]) were positive predictor of ACO. Higher socio-economic status (PIR >1) was negatively associated with ACO (OR 0.37 [0.20–0.69]) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with ACO in participants with Asthma or COPD

| ACO in asthma participants | ACO in COPD participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age in years | 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.53 |

| Gender (women vs. men) | 0.26 (0.13, 0.53) | 0.0001 | 1.12 (0.56, 2.24) | 0.74 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | 2.40 (1.19, 4.86) | 0.015 | 2.65 (1.22, 5.72) | 0.013 |

| Hispanics | 1.06 (0.29, 3.89) | 0.93 | 1.62 (0.57, 4.59) | 0.36 |

| Other | 1.43 (0.52, 3.90) | 0.49 | 1.27 (0.40, 4.06) | 0.69 |

| PIR | ||||

| ≤ 1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| > 1 | 0.59 (0.29, 1.22) | 0.16 | 0.37 (0.20, 0.69) | 0.0016 |

| Education level | ||||

| High School | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| High School diploma/some college | 2.00 (0.81, 4.92) | 0.13 | 1.32 (0.57, 3.07) | 0.52 |

| College graduate or above | 1.78 (0.46, 6.87) | 0.40 | 2.01 (0.54, 7.47) | 0.30 |

| BMI | ||||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 0.48 (0.20, 1.17) | 0.11 | 1.17 (0.45, 3.04) | 0.74 |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 0.61 (0.26, 1.40) | 0.24 | 2.99 (1.14, 7.80) | 0.025 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Never smoked | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Past & current smoker | 3.18 (1.48, 6.85) | 0.0030 | 0.68 (0.26, 1.78) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes | 0.69 (0.33, 1.45) | 0.33 | 1.64 (0.71, 3.80) | 0.25 |

| Hypertension | 0.73 (0.28, 1.86) | 0.50 | 0.75 (0.30, 1.89) | 0.55 |

| MI and/or stroke | 2.78 (0.92, 8.36) | 0.069 | 2.65 (1.10, 6.36) | 0.029 |

| CHF | 1.25 (0.35, 4.50) | 0.73 | 1.98 (0.55, 7.18) | 0.30 |

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ACO, asthma COPD overlap; HS, High School; PIR, Poverty Income Ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index; MI, Myocardial Infarction; CHF, Congestive Heart Failure; OR, odds ratio; CI, Confidence Interval. OR calculated using logistic regression analysis and estimates mutually adjusted for all the other variables in the table

ACO association with asthma severity and oxygen therapy in COPD.

After adjusting for covariates, ACO was very significantly associated with ER visits for asthma (OR 3.46 [1.48–8.06]) and oxygen therapy in COPD (OR: 11.17 [5.17–24.12]).

ACO, spirometry, and eosinophils

As shown in Table 3, the geometric means for FEV1 and PEF values were significantly lower in ACO than in asthma or COPD alone. FVC and FeNo in past smokers were significantly lower in ACO than in COPD alone, while pre- and post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC and FEF 25–75 were significantly lower in ACO than in asthma alone (Table 4).

Table 4:

Geometric means and corresponding 95% CI spirometry measures, and blood eosinophils

| Asthma alone | COPD alone | ACO | PACO vs. Asthma | PACO vs. COPD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVC, liters | 3.41 (3.29, 3.52) | 4.17 (3.99, 4.31) | 3.44 (3.03, 3.91) | 0.87 | 0.0065 |

| FEV1, liters | 2.62 (2.53, 2.71) | 2.56 (2.44, 2.69) | 2.13 (1.86, 2.42) | .0037 | .011 |

| PEF, liters | 7.24 (6.91, 7.57) | 6.81 (6.50, 7.13) | 5.73 (4.98, 6.60) | .0028 | 0.022 |

| FEF 25-75, liters | 2.57 (2.48, 2.67) | 1.15 (1.08, 1.22) | 0.97 (0.83, 1.14) | <.0001 | 0.058 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 76.93 (76.33, 77.54) | 61.72 (60.72, 62.73) | 61.71 (59.51, 63.99) | <.0001 | 0.99 |

| Eosinophils, % | 2.73 (2.54, 2.95) | 2.75 (2.60, 2,91) | 3.18 (2.51, 4.03) | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| FeNO, ppb | |||||

| Overall | 16.67 (14.94, 18.71) | 11.89 (10.84, 13.05) | 14.86 (9.37, 23.55) | 0.63 | 0.38 |

| Never smokers | 18.03 (15.94, 20.40) | 16.61 (14.70, 18.78) | 15.01 (8.04, 28.01) | 0.56 | 0.75 |

| Current smokers | 8.46 (6.70, 10.70) | 7.35 (6.50, 8.31) | 6.93 (5.11, 9.39) | 0.32 | 0.72 |

| Former smokers | 19.83 (15.53, 25.30) | 15.87 (13.95, 18.04) | 31.61 (20.33, 49.13) | 0.067 | 0.0021 |

| FEV1/FVC post BD, % | 72.96 (72.04, 73.90) | 63.03 (62.36, 63.70) | 61.82 (59.49, 64.25) | <.0001 | 0.34 |

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ACO, asthma COPD overlap, FVC, Forced Vital Capacity; FEV, Forced expiratory volume; FEF, Forced expiratory flow, FeNO, Exhaled Nitrate Oxide; ppb, parts per billion; CI, confidence interval; BD, bronchodilator. Geometric means calculated by estimating arithmetic mean of log-transformed estimates and subsequent back transformation.

DISCUSSION

In the US, the prevalence of ACO was 0.96% (crude) to 1.05% (age-standardized) in the period 2007–2012. Age-standardized prevalence of ACO was higher people with low socioeconomic status and comorbidities. Among participants with asthma, increasing age and smoking were predictors of higher ACO prevalence. In participants with COPD, non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity, obesity, and history of MI or stroke were correlates of higher ACO prevalence. ACO was associated with more asthma severity and use of oxygen therapy in COPD. In spirometry, participants with ACO had worse FEV1 and PEF than those with asthma or COPD alone.

Prior studies in the US and elsewhere have reported estimates higher than ours, i.e. around 2% (9, 12, 16). A recent analysis of the BRFSS survey defined COPD by self-report and found a much higher prevalence (3.2% in participants ≥35-years old) (13). Diaz-Guzman et al. also examined the prevalence of self-reported asthma and COPD in the U.S. using NHANES-III (1988–1994) and reported an ACO prevalence of 2.7% (12). Self-reported COPD is widely recognized to be inadequate, since airway obstruction should be documented by spirometry (11). In a cohort of 2,790 nurses who self-reported COPD, Barr et al. found that only 78% were confirmed cases (18). This percentage was even lower in participants who had both asthma and COPD (18). In Canada, self-reported COPD was compared to COPD defined using pulmonary function testing (PFT) and the COPD prevalence using PFT was found to be two to six times higher than the prevalence of self-reported COPD (19). The study also reported minimal agreement between self-reported COPD and COPD defined using PFT, with kappa statistics ranging between 0.1 and 0.2 (19).

Among participants with COPD, our reported ACO prevalence of about 12.59% (crude) or 12.49% (age-standardized) was close to estimates from the COPDGene cohort including 21 US centers which reported a prevalence of 13% (20). They defined overlap as COPD diagnosed by spirometry with additional report of asthma diagnosed before the age 40 (20). However, our estimate for ACO prevalence in COPD was lower than the EPI-SCAN and MAJORICA in Spain which reported respectively 17.4% (21) and 18.3% (22) and the PLATINO study from Latin America which reported 22.8% (23). The EPI-SCAN (21) and the PLATINO (23) both defined ACO as post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC<0.70 and a report of previous asthma diagnosis; the MAJORICA defined ACO as diagnosis of both asthma and COPD confirmed by a physician (22). Among people with asthma, other population studies, most of them using self-reported COPD, have reported a prevalence of ACO equal or higher than our estimates: 13.3% and 29% in the U.S. (12, 24), 17% in Finland (25), and 24.9% in an international study conducted in 14 countries of Europe, Asia, Africa, North and Latin America (26), while we found 14.60% (crude) to 15.34% (age-standardized). In the PLATINO study, which included participants ≥40 years old, the proportion of ACO among asthmatics was much higher, reporting an ACO prevalence over 51.4% (17). Yet, none of these studies reported age-standardized prevalence estimates, which allow for more meaningful comparisons between populations with different age distributions (27). Consistent with our findings on groups with higher ACO prevalence and on ACO predictors, the literature has widely reported that people who smoke, have obesity and/or comorbidities, are more likely to have ACO (9, 22, 28, 29). We also found ACO associated with more asthma severity, consistent with previous observations that ACO subjects have more frequent healthcare utilization for pulmonary diseases and more expensive health care costs than those with asthma or COPD alone (17, 20, 21, 30).

How asthma might lead to ACO or COPD is not fully understood. As early as in 1961, Orie et al. formulated the “Dutch Hypothesis”, proposing that asthma and COPD might have some common genetic origins (31). According to this hypothesis, different types of obstructive lung disease have overlapping characteristics and one (asthma) could potentially progress into another (COPD) (31). This change can be influenced by endogenous, genetic, and environmental factors (31). Recent genetic studies indicated however that asthma and COPD share very little to no genetic background (31). Gelb and Nadel suggested that ACO may begin with asthma and that Th2 inflammation from recurrent exacerbations could lead to neutrophil elastase production and lung tissue destruction (32). They previously noted that some asthma patients who never smoked could have persistent expiratory airflow limitation because of loss of lung elastic recoil and develop what seems to be ACO (33).

We observed that subjects with ACO had worse lung function than participants with only one of the two obstructive conditions. This is consistent with results from studies assessing air trapping in inspiratory and expiratory computed tomography scans (20). Interestingly, we found that the mid-flow rate (FEF25–75%) and the FEV1/FVC ratio in ACO and in COPD were not statistically different, but lower in ACO than in asthma. Both spirometry parameters are considered to be indicators of bronchial obstruction, with FEF25–75% being more characteristic of small airways obstruction and suggested to correlate poorly with air trapping (34). We also found that after bronchodilator administration, FEV1/FVC was poorer in ACO than asthma. This finding suggests that worse elastic recoil may be distinctive feature of ACO, consistent with the mechanism described by Geld and Nagel (32). However, in our analysis, FeNO levels were not associated with ACO, although FeNO is not the only marker of Th2-mediated airway inflammation.

Our study has some limitations. Asthma was self-reported and could thus be subject to under or over-diagnosis or be influenced by easy access to healthcare (35). However, self-report of asthma is widely accepted and likely valid in large-scale epidemiological studies. It is also known that a large proportion of patients with asthma have a normal lung function and using spirometry to define asthma might likely selected subjects with severe asthma and thus significantly biased our results (36). Participants with significant comorbidities were excluded from the baseline and second spirometry. Nonetheless, the study has its strengths; especially, it provides crude and age-adjusted prevalence estimates in a very large sample that is generalizable to the U.S. adult population.

In conclusion, ACO was found in 0.96% to 1.05% of the US adult population from 2007 to 2012. This is much lower than previous estimates in other U.S. studies. ACO is associated with more asthma severity and use of oxygen therapy in COPD as well as worse lung function. Future research should include cohort studies to investigate the trend in the risk of ACO over time and factors that could potentially affect ACO trend in the different segment of the population.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Forno’s effort was funded in part by grant HL125666 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors report no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamauchi Y, Yasunaga H, Matsui H, Hasegawa W, Jo T, Takami K, et al. Comparison of in‐hospital mortality in patients with COPD, asthma and asthma–COPD overlap exacerbations. Respirology. 2015;20(6):940–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambrecht B, Hammad H. Asthma and coagulation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(20):1964–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PJ. Mechanisms in COPD: differences from asthma. Chest. 2000;117(2_suppl):10S–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes PJ. Mechanisms and resistance in glucocorticoid control of inflammation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120(2):76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postma DS, Rabe KF. The asthma–COPD overlap syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(13):1241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendy A, Salo PM, Cohn RD, Wilkerson J, Zeldin DC, Thorne PS. House dust endotoxin association with chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Environ Health Perspect 2018. Epub March 23, 2018. 10.1289/EHP2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Initiative for Asthma. Asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). Global Initiative for Asthma. http://ginasthma.org/asthma-copd-and-asthma-copd-overlap-syndrome-acos/ Accessed April 15, 2017

- 8.Barnes PJ. Asthma-COPD overlap. Chest. 2016;149(1):7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Marco R, Pesce G, Marcon A, Accordini S, Antonicelli L, Bugiani M, et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e62985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alshabanat A, Zafari Z, Albanyan O, Dairi M, FitzGerald J. Asthma and COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS): a systematic review and meta analysis. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0136065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celli BR, MacNee W, ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Guzman E, Khosravi M, Mannino DM. Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and mortality in the US population. COPD 2011;8(6):400–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumbhare S, Pleasants R, Ohar JA, Strange C. Characteristics and Prevalence of Asthma/Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overlap in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mannino DM, Gan WO, Wurst K, Davis KJ. Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overlap: The Effect of Definitions on Measures of Burden. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2017;4(2):87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karampitsakos T, Gourgoulianis KI. ACOS syndrome: Single disease entity or not? Could exhaled nitric oxide be a useful biomarker for the differentiation of ACOS, asthma and COPD? Med Hypotheses. 2016;91:20–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lange P, Çolak Y, Ingebrigtsen TS, Vestbo J, Marott JL. Long-term prognosis of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap in the Copenhagen City Heart study: a prospective population-based analysis. The Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(6):454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menezes AMB, de Oca MM, Rogelio P, Nadeau G, Fernando C, Lopez-Varela MV, et al. Increased risk of exacerbation and hospitalization in subjects with an overlap phenotype: COPD-asthma. Chest. 2014;145(2):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr RG, Herbstman J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA Jr. Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(10):965–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans J, Chen Y, Camp PG, Bowie DM, McRae L. Estimating the prevalence of COPD in Canada: Reported diagnosis versus measured airflow obstruction. Health Rep. 2014;25(3):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardin M, Cho M, McDonald ML, Beaty T, Ramsdell J, Bhatt S, et al. The clinical and genetic features of COPD-asthma overlap syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):341–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Ancochea J, Muñoz L, Duran-Tauleria E, Sánchez G, et al. Characterisation of the overlap COPD–asthma phenotype. Focus on physical activity and health status. Respir Med. 2013;107(7):1053–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Boven JF, Román-Rodríguez M, Palmer JF, Pons NT, Cosío BG, Soriano JB. Comorbidome, pattern and impact of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) in real-life. Chest. 2016;149(4):1011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tálamo C, de Oca MM, Halbert R, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JRB, Muino A, et al. Diagnostic labeling of COPD in five Latin American cities. Chest. 2007;131(1):60–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirabelli MC, Beavers SF, Chatterjee AB. Active asthma and the prevalence of physician-diagnosed COPD. Lung. 2014;192(5):693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauppi P, Kupiainen H, Lindqvist A, Tammilehto L, Kilpeläinen M, Kinnula VL, et al. Overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD predicts low quality of life. J Asthma. 2011;48(3):279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamprecht B, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gudmundsson G, Welte T, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, et al. COPD in never smokers: results from the population-based burden of obstructive lung disease study. Chest. 2011;139(4):752–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtin LR, Klein RJ, National Center for Health Statistics (US). Direct standardization (age-adjusted death rates). US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheaton AG, Pleasants RA, Croft JB, Ohar JA, Heidari K, Mannino DM, et al. Gender and Asthma-Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overlap Syndrome. J Asthma. 2016;53(7):720–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung JW, Kong KA, Lee JH, Lee SJ, Ryu YJ, Chang JH. Characteristics and self-rated health of overlap syndrome. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaya FT, Dongyi D, Akazawa MO, Blanchette CM, Wang J, Mapel DW, et al. Burden of concomitant asthma and COPD in a Medicaid population. Chest. 2008;134(1):14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postma DS, Weiss ST, van den Berge M, Kerstjens HA, Koppelman GH. Revisiting the Dutch hypothesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(3):521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelb AF, Nadel JA. Understanding the pathophysiology of the asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(3):553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelb AF, Yamamoto A, Verbeken EK, Nadel JA. Unraveling the pathophysiology of the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome: unsuspected mild centrilobular emphysema is responsible for loss of lung elastic recoil in never smokers with asthma with persistent expiratory airflow limitation. Chest. 2015;148(2):313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marseglia GL, Cirillo I, Vizzaccaro A, Klersy C, Tosca MA, La Rosa M, et al. Role of forced expiratory flow at 25–75% as an early marker of small airways impairment in subjects with allergic rhinitis Allergy and asthma proceedings; OceanSide Publications, Inc; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nascimento O, Camelier A, Rosa F, Menezes A, Pérez-Padilla R, Jardim J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is underdiagnosed and undertreated in São Paulo (Brazil): results of the PLATINO study. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40(7):887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asmussen L, Olson LM, Grant EN, Fagan J, Weiss KB. Reliability and validity of the Children’s Health Survey for Asthma. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]