Abstract

Objectives:

Outcomes associated with a sedative regimen com prised ketamine + propofol for pediatric procedural sedation outside of both the pediatric emergency department and operating room are underreported. We used the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium database to describe a multicenter experience with ketamine + propofol by pediatric sedation providers.

Design:

Prospective observational study of children receiving IV ketamine + propofol for procedural sedation outside of the operating room and emergency department using data abstracted from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium during 2007–2015.

Setting:

Procedural sedation services from academic, community, free-standing children’s hospitals, and pediatric wards within general hospitals.

Patients:

Children from birth to less than or equal to 21 years old.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

A total of 7,313 pediatric procedural sedations were performed using IV ketamine + propofol as the primary sedative regimen. Median age was 84 months (range, < 1 mo to < 21 yr; interquartile range, 36–144); 80.6% were American Society of Anesthesiologists-Physical Status less than III. The majority of sedation was performed in dedicated sedation or radiology units (76.1%). Procedures were successfully completed in 99.8% of patients. Anticholinergics (glycopyrrolate and atropine) or benzodiazepines (midazolam and lorazepam) were used in 14.2% and 41.3%, respectively. The overall adverse event and serious adverse event rates were 9.79% (95% Cl, 9.12–10.49%) and 3.47% (95% Cl, 3.07–3.92%), respectively. No deaths occurred. Risk factors associated with an increase in odds of adverse event included ASA status greater than or equal to III, dental suite, cardiac catheterization laboratory or radiology/sedation suite location, a primary diagnosis of having a gastrointestinal illness, and the coadministration of an anticholinergic.

Conclusions:

Using Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium data, we describe the diverse use of IV ketamine + propofol for procedural sedation in the largest reported cohort of children to date. Data from this study may be used to design sufficiently powered prospective randomized, double-blind studies comparing outcomes of sedation between commonly administered sedative and analgesic medication regimens.

Keywords: adverse events, ketamine, pediatric procedural sedation, propofol, risk factors

The frequency of procedural sedation (PS) for children outside the operating room has dramatically increased, and provision of safe and effective PS for children has become a standard of care (1). Large cohort studies have described outcomes of PS using propofol or ketamine for children undergoing radiologic imaging studies and painful procedures such as a fracture or joint reduction, laceration repair, and incision and drainage of an abscess (1–5). The combination of ketamine and propofol, sometimes referred to as “ketofol,” has been used widely in the emergency department (ED) (5–9).

Although we have reported the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium (PSRC) experience with the use of propofol and ketamine (independently and separately), currently available reports describing the combined use of ketamine + propofol in children for PS outside of the ED and operating room are limited both by the paucity of pediatric-specific studies and by modest patient enrollment numbers (10–14). Previously, the PSRC database has been used to report on the demographics, success, and adverse sedation-related events associated with a variety of PS medication regimens (3,5,15–17). We used the PSRC database to describe the patient, procedure, and sedation regimen characteristics, adverse event (AE) profile, and risk factors associated with increased odds of AEs or serious AEs (SAEs) in a subcohort of patients receiving the combination of ketamine + propofol for PS.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Collection

This study is an observational cohort review of prospectively collected data from the multicenter PSRC in children and young adults from 21 years old and younger who received IV ketamine + propofol as a sedative regimen for PS during the period September 2007 through November 2015. The dataset presented is a subanalysis of a larger patient cohort who received ketamine for pediatric PS in the PSRC dataset (5). PSRC data collection methodology has been reported in several publications (3, 5, 16,18). The PSRC currently comprised 44 self-selected institutions that include both free-standing children’s hospitals and pediatric wards within general hospitals that are also academic and community-based hospitals (eTable 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A473). Each member institution has obtained institutional review board approval to collect data on a standardized, secure, web-based dynamic data-entry form. Patients who received ketamine by a non-IV route (intramuscular: n = 478; intranasal: n = 99; oral: n = 32; multiple routes: n = 34; other route: n = 3; no route specified: n = 2) likely represent patients with a different set of risk factors, such as difficult IV access or behavioral characteristics, distinct from those patients who received ketamine by the IV route; therefore, the 648 patients (8.08%) who received ketamine via a non-IV route were excluded. Additionally, 51 sedation encounters performed in the ED (0.64%) were excluded from analysis.

Outcomes and AE Measures

Primary outcome measures were successful completion of a procedure or study and occurrence of AE and SAE. The PSRC a priori defined AE (eTable 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A473) and SAE (5, 19). Although multiple AE or SAE could occur within a single course of sedation, the AE and SAE rates were reported as the number of sedations in which at least one AE or SAE occurred out of the total number of sedations. Patients could have been sedated more than once and appear multiple times in the dataset; however, for analysis, multiple sedations on the same patient were considered as independent events because the PSRC database contains deidentified information precluding removal of a patient with multiple sedation encounters. Counting multiple sedation encounters for the same patient should not affect the validity of our analysis because each sedation encounter has unique associated risks and outcomes, and successive sedation encounters should not pose cumulative risks. Information was only available for pre-, intra-, and immediate postprocedure events, and long-term follow-up or any subsequent care related to an SAE is not available. Procedures defined as painful are listed in eTable 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A473).

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were reported as counts and frequencies, medians and interquartile ranges, or means and CIs for patient demographics and sedation procedure characteristics. The percentage of AE and SAE was calculated, and 95% CIs for these events are reported. Subgroup analyses of AE and SAE were performed by the location of sedation, procedure type, and medications coadministered with ketamine + propofol and were compared using chi-square tests. Multiple variable logistic regression was used to identify characteristics associated with higher odds of experiencing an AE. Resulting risk factors are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Because of the potential for confounding due to case mix, ASA status, and referral patterns across institutions, adjustment for individual center effect was not performed. Potential risk factors were identified because of their historically demonstrated association with the occurrence of AE and included age, sex, weight, ASA physical status greater than or equal to III, primary diagnosis, location of sedation, type of procedure, nil per os (NPO) status for clear liquids and solids, and identity of adjunctive medications administered. Since age and weight are highly correlated, age was used in the model. Also, procedure type and location are highly correlated, and location of sedation was used in the final model. All variables were initially included in the model, and a modified backward elimination procedure was used to systematically remove nonsignificant variables provided that the model fit did not significantly change. Statistical significance was assessed using a significance level of p value of less than 0.05 unless otherwise noted, and two-sided statistical tests are reported. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographics and Sedation Characteristics

Between September 2007 and November 2015, there were 8,012 sedations using ketamine + propofol reported in the PSRC database. Demographic and sedation characteristics are reported in Tables 1 and 2. After exclusion of the 51 patients sedated with ketamine + propofol in the ED and the 646 patients who received non-IV dosing of ketamine, there were 7,313 patients who received ketamine + propofol included in the final analysis.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Children Sedated With Ketamine + Propofol (n = 7,313)

| Characteristic | n (%) or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Age (mo) | 84 (36–144) |

| Range (min, max) | 0,264 |

| 0–3 mo | 110 (1.5%) |

| 4–12 mo | 499 (6.8%) |

| 1–13 yr | 5,249 (71.8%) |

| > 13 yr | 1,455 (19.9%) |

| Weight (kg) | 24.5 (14.7–49.0) |

| Range (min, max) | 1.8, 175 |

| < 5 kg | 72 (1.0%) |

| Sex (n = 7,312) | 3,934 (52.6%) |

| Male | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists-Physical Status (n = 7,222) | |

| < III | 5,817 (80.6%) |

| ≥ III | 1,405 (19.5%) |

| NPO clear liquid (n = 7,160) | |

| < 2 hr | 35 (0.5%) |

| ≥ 2 hr | 7,125 (99.5%) |

| NPO solids (n = 7,263) | |

| < 6 hr | 120 (1.6%) |

| ≥ 6 hr | 7,143 (98.4%) |

| Primary diagnosis (%) | |

| Hematology/oncology | 1,629 (22.3) |

| Infection | 1,335 (18.3) |

| Neurologic | 1,008 (13.8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 948 (13.0) |

| Other | 442 (6.0) |

| Surgical/wound management | 365 (5.0) |

| Renal | 324 (4.4) |

| Orthopedics | 251 (3.4) |

| Burn | 243 (3.3) |

| Dermatologic | 186 (2.5) |

| Metabolic/genetic (includes obesity) | 143 (2.0) |

| Rheumatology | 154 (2.1) |

| Respiratory—lower airway | 117 (1.6) |

| Status posttrauma | 96 (1.3) |

| Cardiovascular | 77 (1.1) |

| Dental | 80 (1.1) |

| Liver disease | 64 (0.9) |

| Status posttransplant | 38 (0.5) |

| Congenital conditions | 30 (0.4) |

| Respiratory—upper airway | 25 (0.3) |

| Craniofacial abnormalities | 8 (0.1) |

| Immune compromise | 10 (0.1) |

| Prematurity related | 7 (0.1) |

NPO = nil per os, IQR = interquartile range.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Pediatric Procedural Sedation Characteristics Performed Using IV Ketamine + Propofol (n = 7,313)

| Characteristic | n (%) or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Location (%) | |

| Radiology/sedation unit | 5,568 (76.1) |

| PICU | 813 (11.1) |

| Othera | 569 (7.8) |

| Spec clinic/floor | 329 (4.5) |

| Cath laboratory | 28 (0.4) |

| Dental | 6 (0.1) |

| Provider (%) | |

| Intensivist | 5,543 (75.8) |

| Emergency medicine | 1,452 (19.9) |

| Anesthesiology | 158 (2.2) |

| Hospitalist | 77 (1.1) |

| Otherb | 83 (1.1) |

| Procedure (%) | |

| Surgical/invasivec | 2,049 (28.0) |

| Radiology | 1,437 (19.6) |

| Hematology/oncology | 1,434 (19.6) |

| Gastrointestinal | 887 (12.1) |

| Bone | 400 (5.5) |

| Neurologic | 301 (4.1) |

| Dental | 83 (1.1) |

| Cardiac | 57 (0.8) |

| Airway | 53 (0.7) |

| Otherd | 975 (13.3) |

| Painful proceduree | 5,251 (71.8) |

| Medications (%) | |

| Ketamine + propofol only | 3,660 (50.1) |

| Benzodiazepine (midazolam or lorazepam) | 3,017 (41.3) |

| Anticholinergics (atropine or glycopyrrolate) | 1,036 (14.2) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 42 (0.6) |

| Barbiturate (pentobarbital, methohexital, or thiopental) | 7 (0.1) |

| Procedure not completed (n = 6,692)f | 13 (0.2) |

IQR = interquartile range.

Other location includes operating room, endoscopy suite, and radiation oncology unit.

Other provider includes nonphysician anesthetists and nurse anesthetists.

Surgical/invasive procedures include peripherally inserted central catheter, incision and drainage of an abscess, and renal biopsy.

Not defined.

Painful procedures are defined in eTable 3.

Data are missing for some entries.

Data-Contributing PSRC Sites

During the September 2007 to November 2011 study period, there were 29 of 40 participating sites (72.5%) that contributed 3,108 unique sedation records using ketamine + propofol of 139,971 total sedations (2.22%). During the December 2011 to November 2015 study period, there were 48 of 54 participating sites (88.9%) that contributed 6,877 unique sedation records using ketamine + propofol of 222,738 total sedations (3.09%). In the earlier cohort, 80% of the total number of ketamine + propofol sedations was contributed by seven sites (24.1%). In the latter group, 11 sites (22.9%) contributed 80% of the total number of ketamine + propofol sedation records. These data are summarized in eFigure 1.

AE and SAE

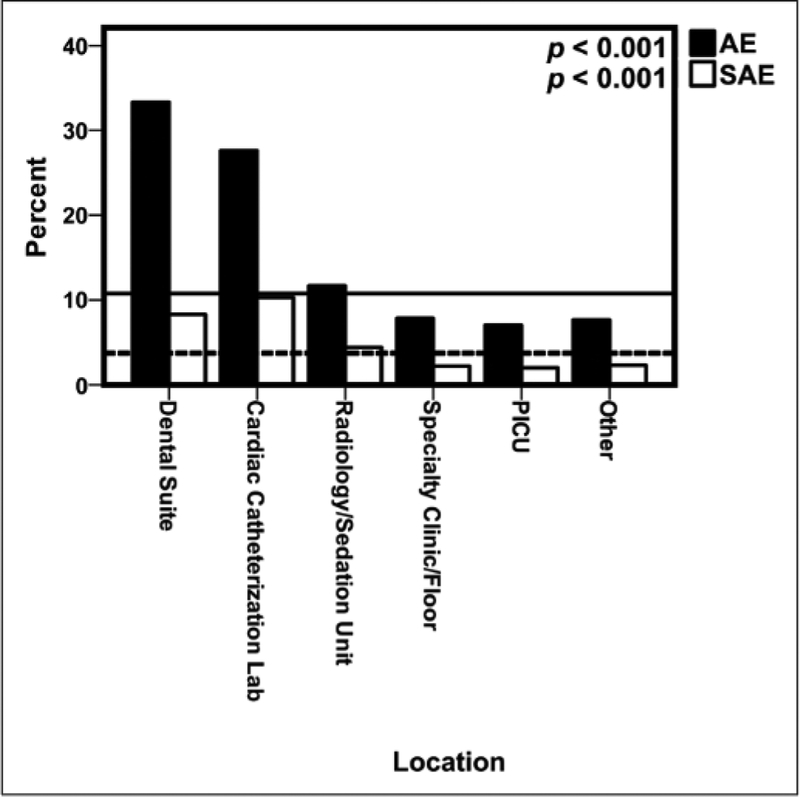

Of the 7,313 ketamine + propofol sedations, there were 716 sedation encounters where the patient experienced at least one AE (9.79%; 95% Cl, 9.12–10.49%), with 804 total AE reported. There were 254 sedations with at least one SAE (3.47%; 95% Cl, 3.07–3.92%), with 334 total SAE reported. Table 3 lists the overall rate of AE and SAE as well as event characterization. Demographic and sedation information regarding the three patients who aspirated and the two patients with cardiac arrest has been reported (5). No deaths occurred. Figure 1 shows that AE and SAE varied considerably by location (p < 0.001 for both AE and SAE rates).

TABLE 3.

Overall Adverse Event and Serious Adverse Event Percentages for Ketamine + Propofol

| Characteristic | n(%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse eventa | 716 (9.79) | 9.12–10.49 |

| Desaturation | 282 (3.86) | 3.43–4.32 |

| Cough | 107 (1.46) | 1.20–1.77 |

| Apnea > 15 s | 115 (1.57) | 1.30–1.88 |

| Secretions | 91 (1.24) | 1.00–1.53 |

| IV related | 23 (0.31) | 0.20–0.47 |

| Unexpected change in heart rate, blood pressure > 30% | 64 (0.88) | 0.67–1.11 |

| Other | 52 (0.71) | 0.53–0.93 |

| Agitation/delirium | 31 (0.42) | 0.29–0.60 |

| Vomiting | 15 (0.21) | 0.11–0.34 |

| Not completed (n = 6,855) | 13 (0.19) | 0.10–0.33 |

| Wheezing | 11 (0.15) | 0.08–0.27 |

| Any serious adverse eventa,b | 254 (3.47) | 3.07–3.92 |

| Airway obstruction | 144 (1.97) | 1.66–2.31 |

| Emergent airway | 118 (1.61) | 1.34–1.93 |

| Laryngospasm | 51 (0.70) | 0.52–0.92 |

| Unplanned admission | 11 (0.15) | 0.08–0.27 |

| Emergency anesthesia | 6 (0.08) | 0.03–0.18 |

| Aspiration | 3 (0.04) | 0.01–0.12 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.01) | 0.00–0.08 |

Defined as the percentage of sedations where at least one adverse event (AE) or serious AE occurred.

No deaths occurred.

Figure 1.

Percentage of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs)by location of sedation. The lines represent the baseline percentage of AE (solid) and SAE (dashed) of the entire ketamine + propofol cohort Other location includes operating room, endoscopy suite, or radiation oncology unit

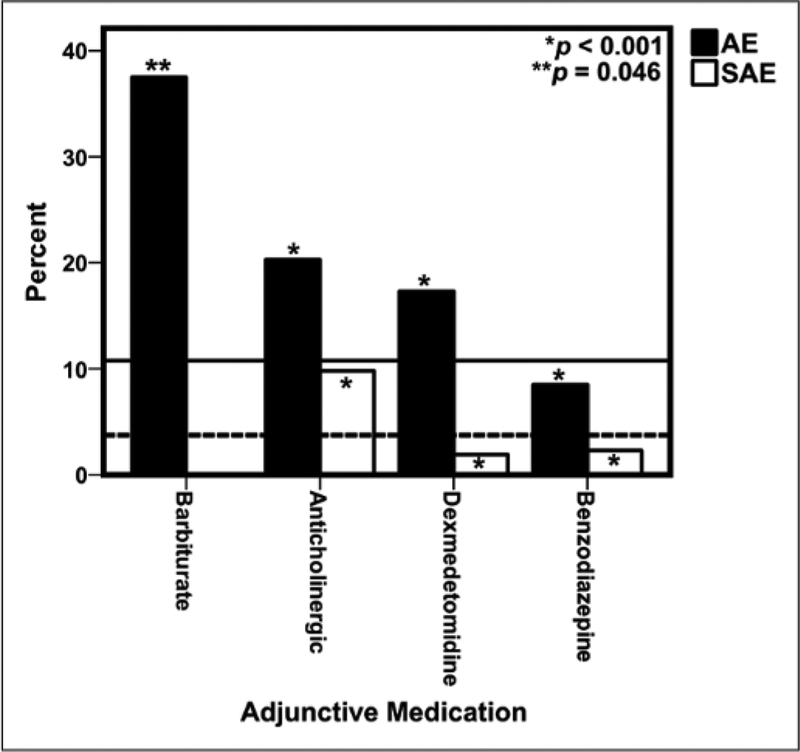

AE and SAE by Coadministration of Adjunctive Medications

The percentage of AE and SAE of ketamine + propofol alone were compared to the coadministration of ketamine + propofol with adjunctive medications such as benzodiazepines (midazolam, lorazepam), anticholinergics (glycopyrrolate, atropine), dexmedetomidine, and barbiturates (Fig. 2). Benzodiazepine coadministration was associated with decreased odds of AE or SAE. Dexmedetomidine was associated with increased odds of an AE but decreased odds of a SAE. Anticholinergics and barbiturates were associated with increased odds of AE and SAE. eTable 4 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A473) compares the AE and SAE for ketamine + propofol with and without the coadministration of an anticholinergic and/or a benzodiazepine. The addition of an anticholinergic medication was associated with a higher percentage of desaturations, airway obstruction, and the need to emergently secure the airway with either an endotracheal tube or a laryngeal mask airway. Similarly, a review of the ketamine ± benzodiazepine data shows that AE and SAE such as desaturation, airway obstruction, cough, apnea, and need for securing the airway emergently were all reported at a lower frequency with the coadministration of a benzodiazepine.

Figure 2.

Percentage of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs) by coadministration of adjunctive medications. The lines are the baseline percentage of AE (solid) and SAE (dashed) of the entire ketamine + propofol cohort Only eight sedation encounters reported coadministration of a barbiturate with ketamine + propofol, and there were no SAE reported for this combination of medications.

Risk Factors for AE and SAE

The final multiple variable logistic model included the variables of procedural location, adjunct medication use, a primary diagnosis of a gastrointestinal, hematology/oncology, or surgical/wound management issue, age, ASA status, and performance of a painful procedure (Table 4). NPO status of clear liquids for less than 2 hours or of solids for less than 6 hours was not associated with an increased risk of AE; however, most patients met the NPO guidelines, and therefore, the study lacks the power to detect a significant association of this variable with outcomes. Of note, a recently published article by Beach et al (20) from the PSRC looked at over 100,000 sedations and found that NPO status for liquids and solids is not an independent predictor of major complications or aspiration in this sedation/anesthesia dataset. After adjusting for ASA status, painful procedure, adjunctive medications, and primary diagnosis, the location of sedation was still a significant predictor of an AE. Patients with an ASA-PS of greater than or equal to III had significantly higher odds of an SAE (OR, 1.73; 95% Cl, 1.29–2.32) compared with an ASA-PS less than III. Patients undergoing a painful procedure had significantly lower odds of an AE than those not having a painful procedure (OR, 0.77; 95% Cl, 0.64–0.92), but not an SAE (OR, 0.83; 95% Cl, 0.61–1.13). The use of a benzodiazepine as an adjunctive medication was associated with a significant decrease in the odds of an SAE (OR, 0.29; 95% Cl, 0.21–0.42); however, the use of an anticholinergic was associated with increased odds of an SAE (OR, 3.15; 95% Cl, 2.38–4.16). A primary diagnosis of a hematology/oncology illness (OR, 0.59; 95% Cl, 0.41–0.85) decreased the odds of an SAE.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable Logistic Regression: Risk Factors for Adverse Events or Serious Adverse Events

| Effect | OR Any AE | 95% CI AE | OR Any SAE | 95% CI SAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 0–3 mo | 1.29 | 0.69–2.39 | 2.01 | 0.76–5.34 |

| 4–12 mo | 1.08 | 0.77–1.53 | 1.61 | 0.92–2.82 |

| 1–13 yr | 1.08 | 0.87–1.33 | 1.44 | 0.98–2.10 |

| >13 yr | Reference | Reference | ||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists-Physical Status | ||||

| ≥ III | 1.41 | 1.16–1.70 | 1.73 | 1.29–2.32 |

| < III | Reference | Reference | ||

| Location | ||||

| Dental | 7.37 | 1.25–43.45 | 12.84 | 1.21–136.06 |

| Cardiac catheterization laboratory | 5.67 | 2.12–15.20 | 5.70 | 1.18–27.53 |

| PICU | 1.76 | 1.01–3.07 | 2.45 | 0.86–6.99 |

| Radiology/sedation unit | 1.73 | 1.07–2.79 | 2.68 | 1.07–6.70 |

| Other | 1.14 | 0.62–2.09 | 1.64 | 0.52–5.21 |

| Specialty clinic/floor | Reference | Reference | ||

| Painful procedure: yes | 0.77 | 0.64–0.92 | 0.83 | 0.61–1.13 |

| Adjunctive medicationa | ||||

| Benzodiazepine | 0.52 | 0.43–0.63 | 0.29 | 0.21–0.42 |

| Anticholinergic | 2.08 | 1.72–2.52 | 3.15 | 2.38–4.16 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||

| Hematology/oncology | 0.73 | 0.58–0.91 | 0.59 | 0.41–0.85 |

| Surgical/wound management | 0.37 | 0.19–0.74 | 0.31 | 0.07–1.26 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.40 | 1.12–1.76 | 0.83 | 0.55–1.27 |

AE = adverse event, OR = odds ratio, SAE = serious adverse event.

The reference group for adjunctive medications is all the sedations for which this adjunct was not administered. Boldface values denote statistical significance with a p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The combination of propofol + ketamine is believed to potentiate the positive aspects and ameliorate the negative aspects of each drug to result in a safer and more effective sedative/analgesic drug regimen for PS. Results from our study demonstrate that over 99.7% of procedures were completed using ketamine + propofol. Although the overall SAE rate was low (3.47%), it was higher compared with the use of propofol alone (2.21%) or with the use of ketamine alone (1.77%) for PS reported in previous PSRC studies (15, 17). Among the SAEs in the ketamine + propofol combination group from this study, we found a higher percentage of airway obstruction, emergent airway intervention, unplanned admission, and emergency anesthesia consultation compared with what is reported in previous PSRC studies on propofol alone (SAE 2.21% and 2.28% for references [15] and [161, respectively) (15, 16, 20). The overall AE for ketamine + propofol (9.79%) was nearly double that for the overall AE rate for propofol alone (5%, reference [16]) and 1.5 times the overall AE rate for ketamine alone (7.3%, reference [5]) as reported in prior studies using the PSRC database (AE 3.55% for reference [15]) (5, 15, 16), with a higher percentage of desaturation, cough, and secretions seen in the ketamine + propofol group compared with propofol used as a single agent (15, 16). Although combining ketamine and propofol could theoretically decrease the propofol dosing requirements and therefore lead to decreased respiratory AE, we are unable to determine the causality of this noted association due to lack of dosing data. Unfortunately, dosing data are only available before 2011, thus limiting the number of sedations with dosing data available for analysis to 2,795 of7,313 sedations of IV administered ketamine + propofol sedations, which correspond to 38% of the total sedations.

Just over two thirds (71.8%) of the sedations in this study for which ketamine + propofol was used were classified as painful procedures when compared with slightly under half of patients (48.3%) receiving propofol alone from the PSRC dataset (16). The performance of painful procedures has been correlated with fewer AE when a single agent such as propofol or ketamine is used (5, 16). The addition of propofol to ketamine may further blunt the response to a painful stimulus, or the use of two medications, rather than a single agent alone, may result in increased AE despite a painful stimulus. Painful procedures tend to be shorter in duration than nonpainful imaging studies, which may impact the incidence of AEs. Additionally, the pain of a procedure may help increase alertness and respiratory activity decreasing the risk for respiratory suppression. Vomiting is a well-known AE of ketamine with an estimated frequency of 8.4–30% (21, 22). Our study has shown a low incidence of vomiting similar to what has been reported in other ketamine + propofol studies (9, 12, 23). This is most likely due to the anti-emetogenic effect of propofol.

We found a small increase in the odds of experiencing a SAE for children from 1 to 13 years old. A meta-analysis of ketamine has shown that for children under 12 months old and greater than 13 years old have higher odds of adverse airway and respiratory events (24). Emesis peaks at 12 years old in a separate meta-analysis of ketamine-associated vomiting and postrecovery agitation (4). The overwhelming majority of children (72.5%) in our ketamine + propofol cohort were between 1 and 13 years old with another 18.9% of children greater than 13 years old. In our published study of ketamine administration alone, there was no association of having higher odds of a SAE for any age (5). We are likely under powered to detect differences in AE and SAE based on age in our ketamine + propofol cohort.

We also found that the percentages of AE and SAE with ketamine + propofol were higher in dental suites and cardiac catheterization laboratories compared with radiology suites. Previous studies have shown a similar trend of AE and SAE in these locations (16, 25–27). Patients presenting for procedures in the cardiac catheterization laboratory are likely more medically fragile and complex than the general patient population, which may contribute to increased rates. The higher incidence of AE with ketamine + propofol in dental suites may be explained by the presence of rubber dams, secretions, blood, and exogenous water in the oropharynx, which may increase respiratory AE. Furthermore, the higher AE with dental procedures, which comprise only 1.2% of PSRC sedations, may be due to underreporting of dental sedation in the PSRC database. A higher odds of AE were also associated with the use of ketamine + propofol for patients with gastrointestinal disease undergoing endoscopy procedures. Endoscopy procedures stimulate the posterior pharynx and have been shown in previous studies with ketamine alone to be associated with higher AE rates (28,29).

We found that use of anticholinergic medications had higher odds of AE and SAE when combined with ketamine + propofol. This is similar to the finding from several previous studies (4,5), and sedation providers should be vigilant of the increase in AE and SAE with the addition of anticholinergic drugs and perhaps mitigate these events by avoiding this practice. It is not possible from the PSRC database to determine whether the anticholinergic medication was used prophylactically to decrease secretions or therapeutically for secretions developed after use of ketamine + propofol. In contrast to the anticholinergic medication data, we found that use of a benzodiazepine with ketamine + propofol was associated with lower odds of AE and SAE similar to studies reporting the use of ketamine alone (4, 5, 30). Using the PSRC database, we are unable to report whether a benzodiazepine was administered prophylactically to prevent ketamine-related agitation or as a treatment for emergence agitation following ketamine sedation. The incidence of agitation/delirium in our study was low as seen in another ketamine + propofol study (10), and the current study is underpowered to detect changes in the frequency of agitation/delirium changes with the coadministration of adjunctive medications. Propofol has hypnotic effects that may blunt recovery agitation associated with ketamine. Ketamine may have been administered early in the procedure, whereas propofol was given for the duration of the procedure. Because the pharmacokinetics profile of ketamine is relatively short, the emergence time window for ketamine may have dissipated before propofol was discontinued or the last dose was administered. The lack of postprocedure recovery data capture of AE and SAE is a limitation of the PSRC database and likely results in the underreporting of these outcomes. Further studies are needed to confirm our finding of the protective effect of a benzodiazepine administered as an adjunctive medication as we are not able to determine why this phenomenon occurred.

A major limitation of this study is that it is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected observational data from a nonrandomized cohort of children who received ketamine + propofol sedation. Other limitations of publications using data from the PSRC database have been previously delineated in numerous other studies (3, 15, 16) and include the possibility of a higher level of performance at PSRC centers than in nonstudy centers. Specific patient-monitoring devices such as pulse oximetry, end-tidal Co2 cannula, noninvasive blood pressure, and electrocardiographic heart rate monitoring are recommended during sedation but are not mandated by the PSRC. Additionally, there are no data collected on the depth of sedation, and we acknowledge that AEs can increase as the sedation depth increases. There are also no hemodynamic or physiologic variables collected for each sedation encounter, limiting the unbiased reporting of AE and SAE. Although SAEs are clearly defined, and agreed upon, the reporting of AE may not be consistent among all sedation providers. The PSRC dataset does not capture dosing data after November 2011 for the combination of ketamine and propofol; therefore, neither the dosing nor the timing of administration of adjunctive medications is captured in the PSRC database, thus preventing analysis of the prophylactic versus reactionary administration of these adjunctive medications. Furthermore, information on whether ketamine and propofol were premixed in the same syringe, or whether this drug combination was administered sequentially, is not recorded in the PSRC dataset. Furthermore, although recent studies have investigated a range of ketamine + propofol combination ratios (31,32), this information is not available from the PSRC dataset. Finally, although 44 centers currently participate in the PSRC, propofol is not available for use at every site and site-level bias exists in this cohort as 80% of cases were contributed by 20% of the participating centers; therefore, center-based bias is introduced into this study that could affect the extension of these results to other centers.

CONCLUSIONS

This study describes a large patient cohort undergoing pediatric PS outside the ED and operating room setting using a combination of ketamine and propofol. Data from this study may be used to design sufficiently powered, prospective randomized, doubleblinded studies comparing outcomes of sedation between commonly administered sedative and analgesic medication regimens. For example, based on recent studies from the PSRC noting the association of higher odds of AEs with anticholinergic administration with ketamine or ketamine + propofol, we propose that appropriately powered, randomized, controlled, multicentered trials (multicenter RCT) involving children receiving painful procedures, such as bone marrow aspirates and lumbar punctures for malignancy, be conducted to compare the combination of fentanyl + propofol with ketamine + propofol. In addition to AE outcomes, we propose monitoring the duration of sedation and time to recovery for these drug regimens. Our studies have noted a higher incidence of AE with anticholinergic administration. We propose a multicenter RCT of children with secretions or upper respiratory tract infections, a population whom sedation might be deferred due to these symptoms and who may benefit from prophylactic glycopyrrolate administration prior to receiving ketamine or ketamine + propofol sedation. Similarly, we propose that a multicenter RCT be conducted to measure whether prophylactic versus rescue benzodiazepine administration causes decreased risk of adverse airway and postprocedure agitation events following ketamine or ketamine + propofol sedation for painful procedures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Emory + Children’s Biostatistics Core for their help with statistical analysis. We also thank all the participating members of the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium (eTable 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A473).

Drs. Grunwell and Kamat conceived and developed the study and wrote the article. Dr. Travers conducted statistical analyses and edited the article. Drs. Stormorken, Scherrer, Chumpitazi, Stockwell, Roback, and Cravero edited the article. Dr. Cravero designed, initiated, directs and maintains the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium database. All authors read and approved the article.

Dr. Grunwell is supported by a T32GM095442. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ pccmjournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Coté CJ: American Academy of Pediatrics sedation guidelines: Are we there yet? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012; 166:1067–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cravero JP: Pediatric sedation with propofol-continuing evolution of procedural sedation practice. J Pediatr 2012; 160:714–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cravero JP, Beach ML, Blike GT, et al. ; Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium: The incidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia with propofol for procedures outside the operating room: A report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Anesth Analg 2009; 108:795–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green SM, Roback MG, Krauss B, et al. ; Emergency Department Ketamine Meta-Analysis Study Group: Predictors of emesis and recovery agitation with emergency department ketamine sedation: An individual-patient data meta-analysis of 8,282 children. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 54:171–80.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunwell JR, Travers C, McCracken CE, et al. : Procedural sedation outside of the operating room using ketamine in 22,645 Children: A report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17:1109–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willman EV, Andolfatto G: A prospective evaluation of “ketofol” (ketamine/propofol combination) for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2007; 49:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roback MG, Carlson DW, Babl FE, et al. : Update on pharmacological management of procedural sedation for children. Curt Opin Anaesthesiol 2016; 29(Suppl 1):S21–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andolfatto G, Willman E: A prospective case series of single-syringe ketamine-propofol (Ketofol) for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia in adults. Acad Emerg Med 2011. ; 18:237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aouad MT, Moussa AR, Dagher CM, et al. : Addition of ketamine to propofol for initiation of procedural anesthesia in children reduces propofol consumption and preserves hemodynamic stability. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008; 52:561–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andolfatto G, Abu-Laban RB, Zed PJ, et al. : Ketamine-propofol combination (ketofol) versus propofol alone for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: A randomized double-blind trial. Ann Emerg Med 2012; 59:504–12.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kogan A, Efrat R, Katz J, et al. : Propofol-ketamine mixture for anesthesia in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. J Cardiothorac Vase Anesth 2003; 17:691–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah A, Mosdossy G, McLeod S, et al. : A blinded, randomized controlled trial to evaluate ketamine/propofol versus ketamine alone for procedural sedation in children. Ann Emerg Med 2011. ; 57:425–33.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomatir E, Atalay H, Gurses E, et al. : Effects of low dose ketamine before induction on propofol anesthesia for pediatric magnetic resonance imaging. Paediatr Anaesth 2004; 14:845–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green SM, Mason KP, Krauss BS: Ketamine and propofol sedation by emergency medicine specialists: Mainstream or menace? Br J Anaesth 2016; 116:449–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallory MD, Baxter AL, Yanosky DJ, et al. ; Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium: Emergency physician-administered propofol sedation: A report on 25,433 sedations from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Ann Emerg Med 2011. ; 57:462–468.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamat PP, McCracken CE, Gillespie SE, et al. : Pediatric critical care physician-administered procedural sedation using propofol: A report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium Database. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015; 16:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulton C, McCracken C, Simon HK, et al. : Pediatric procedural sedation using dexmedetomidine: A report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Hosp Pediatr 2016; 6:536–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cravero JP, Blike GT, Beach M, et al. ; Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium: Incidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room: Report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatrics 2006; 118:1087–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamat PP, Hollman GA, Simon HK, et al. : Current state of Institutional Privileging Profiles for pediatric procedural sedation providers. Hosp Pediatr 2015; 5:487—494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beach ML, Cohen DM, Gallagher SM, et al. : Major adverse events and relationship to nil per os status in pediatric sedation/anesthesia outside the operating room: A report of the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Anesthesiology 2016; 124:80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green SM, Andolfatto G, Krauss BS: Ketofol for procedural sedation revisited: Pro and con. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 65:489–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green SM, Kuppermann N, Rothrock SG, et al. : Predictors of adverse events with intramuscular ketamine sedation in children. Ann Emerg Med 2000; 35:35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akin A, Esmaoglu A, Guler G, et al. : Propofol and propofol-ketamine in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Pediatr Cardiol 2005; 26:553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green SM, Roback MG, Krauss B, et al. : Predictors of airway and respiratory adverse events with ketamine sedation in the emergency department: An individual-patient data meta-analysis of 8,282 children. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 54:158–168.e151−168.e154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coté CJ, Karl HW, Notterman DA, et al. : Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: Analysis of medications used for sedation. Pediatrics 2000; 106:633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chicka MC, Dembo JB, Mathu-Muju KR, et al. : Adverse events during pediatric dental anesthesia and sedation: A review of closed malpractice insurance claims. Pediatr Dent 2012; 34:231–238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coté CJ: Discharge criteria for children sedated by nonanesthesioloqists: Is “safe” really safe enouqh? Anesthesioloqy 2004; 100:207–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green SM, Roback MG, Kennedy RM, et al. : Clinical practice guideline for emergency department ketamine dissociative sedation: 2011 update. Ann Emerg Med 2011. ; 57:449–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green SM, Klooster M, Harris T, et al. : Ketamine sedation for pediatric gastroenterology procedures. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001. ; 32:26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wathen JE, Roback MG, Mackenzie T, et al. : Does midazolam alter the clinical effects of intravenous ketamine sedation in children? A double-blind, randomized, controlled, emergency department trial. Ann Emerg Med 2000; 36:579–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coulter FL, Hannam JA, Anderson BJ: Ketofol simulations for dosing in pediatric anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth 2014; 24:806–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jalili M, Bahreini M, Doosti-lrani A, et al. : Ketamine-propofol combination (ketofol) vs propofol for procedural sedation and analgesia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34:558–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.