ABSTRACT

Tumor-infiltrating neutrophils (TINs) show diverse predictive effects in the context of different cancer types and therapeutic regimens. In this study we investigated their relevance with therapeutic effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Two independent datasets including 271 mRCC patients treated by TKIs or IL-2/IFN-α based immunotherapy were retrospective included, and TINs were detected by immunohistochemistry. The presence of TINs was observed in 50 (45.0%) samples of the TKI cohort and in 73 (45.6%) samples of the immunotherapy cohort. TINs were associated with shorter overall survival (HR, 1.776; 95%CI, 1.191–2.650; p = 0.004) in the TKI cohort, but not in the immunotherapy cohort (HR, 1.074; 95%CI, 0.767–1.505; p = 0.672). Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed the independent prognostic value of TINs for TKI-treated patients (HR, 2.078, 95%CI, 1.352–3.195; p = 0.001), apart from other parameters. Moreover, survival benefit of TKI therapy was superior to IL-2/IFN-α immunotherapy only among TINs-absent patients (HR, 1.561; 95%CI, 0.927–2.629; p = 0.094). Data mining in the TCGA cohort of renal cell carcinoma revealed the predominant immunosuppressive function of TINs in renal cell carcinoma. The negative correlation between TINs and intratumoral CD8+ T cells was further confirmed in the TKI cohort (p = 0.019), the immunotherapy cohort (p = 0.001) and the TCGA cohort (p < 0.001). In conclusion, the presence of TINs was an independent, unfavorable prognostic factor in TKI-treated mRCC patients. TINs could also predict therapeutic benefit of TKIs over IL-2/IFN-α immunotherapy. These findings should be further confirmed within datasets of clinical trials or prospective observational studies.

KEYWORDS: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, tumor-infiltrating neutrophils, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, survival

Introduction

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) is an extremely lethal disease. In the past decade, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have become first-line recommendation for mRCC.1–3 However, most mRCC patients receiving TKIs will finally develop therapeutic resistance, after an average duration of approximately 8–9 months.4 Generally speaking, alternative pro-angiogenic signaling pathways and alternative modes of tumor vascularization are usually used to explain TKI resistance5,6. Recently, recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells into the tumor has also been identified as an independent mechanism of TKI resistance.7–10 These bone marrow-derived cells included macrophages, neutrophils and immature monocytes. However, these studies were performed on tumor-bearing animals. The interaction between bone marrow-derived cells and TKI resistance has not been discovered in mRCC patients.

Neutrophils are essential in the tissue damage and wound healing processes. Recent studies revealed that tumor-infiltrating neutrophils (TINs) were a highly heterogeneous population of cells with some cells demonstrating pro-tumorigenic and some anti-tumorigenic activity.11,12 The terms anti-tumorigenic N1 and pro-tumorigenic N2 neutrophils were introduced to describe TINs11. In accordance with this classification, TINs showed diverse prognostic effects in the context of different cancer types and therapeutic regimens. For instance, TINs correlated with longer survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma13 and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.14 On the contrary, TINs were also associated with dismal survival in hepatocellular carcinoma,15–17 cervical cancer,18 gastric cancer,19 colorectal carcinoma20 and melanoma.21 In a previous study, we also identified TINs as a predictive indicator for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in bladder cancer and gastric cancer patients.22,23 In the context of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), both tumor-infiltrating and peripheral blood neutrophils were regarded as “bad guys” in previous studies.24–26 Moreover, peripheral blood neutrophil count was found predictive for target therapy in mRCC patients.27,28 However, the involvement of TINs in mRCC TKI therapy, as well as their relationship with peripheral blood neutrophils, has not been clarified yet.

Comprehensive immune atlas identified an immunosuppressive microenvironment in RCC,29 with prognostic implications.30 The therapeutic effects of TKI agents may also rely on the adaptive immunity against tumor, since the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment mediate TKI resistance. Moreover, TKI agents showed immune-enhancing effects by suppressing regulatory T (Treg) cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs).31–34 TINs also contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, but their contribution to TKI response and resistance has not been explored yet.

In the present study, we evaluated the presence of TINs in mRCC samples and explored its correlation with patients’ survival in 111 patients treated with TKIs and 160 patients treated with IL-2 or IFN-α based immunotherapy. The predictive value of TINs for TKI therapeutic benefit over immunotherapy was also assessed. The functional implications of TINs in RCC was studied in TCGA datasets and validated in the study cohort. These results illuminate the potential relevance between TINs and TKI therapy, especially for mRCC patients.

Patients and methods

Patients and tissue samples

Two independent cohorts of mRCC patients were retrospective included from Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University. The TKI cohort was consisted of 111 patients treated with first-line TKIs from Mar 2005 to Jun 2014. No patient in the TKI cohort ever received any kind of immunotherapy. The immunotherapy cohort included 160 patients who were treated only with first-line IL-2 or IFN-α based immunotherapy from Jan 2005 to Dec 2011. No patient in the immunotherapy cohort ever received targeted agents or immune checkpoint blockers (ICBs). All patients enrolled had archived tissue samples and no history of other malignancies. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Registration No. B2015-030). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The REMARK criteria was followed during the report.35

The medical history of all patients enrolled was collected from medical records and was reviewed by a urologist. Tumor metastasis was diagnosed and reviewed according to computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, bone scanning, positron emission tomography-computed tomography, or biopsy. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of systemic therapy to death, and progression free survival (PFS) was from the start of therapy to RECIST progressive disease or death.36 The last collection of follow-up data was performed in Jan 2017. The median follow-up was 64.1 [95% confidence interval (CI) 34.5–93.8] months in the TKI cohort and 30.4 [95% confidence interval (CI) 12.4–131.6] months in the immunotherapy cohort by reverse Kaplan-Meier estimator.37 Patients’ risk stratification was performed by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk score.38 Archived tissue samples and surgical specimens of all patients were collected for the study. All pathologic features, including histology type,39 tumor grade40 and TNM stage,41 underwent pathological re-review by a genitourinary pathologist. Archived tissue samples of all patients were collected.

Clinical and genomic data of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were downloaded from the UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/). The proportion of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, downloaded from The Cancer Immunome Atlas (TCIA) website (https://tcia.at/home), was calculated by using the CIBERSORT method according to the tumoral transcriptomes.42

Tissue microarrays and immunohistochemistry

All archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sliced and stained with haematoxylin-eosin for pathologic review, diagnostic confirmation and representative area selection before the construction of tissue microarrays (TMAs). After that, TMAs were constructed following previously described procedures.43 In brief, two 4-mm-diameter tumor cores were taken from each tumor sample to build TMA blocks. TMA blocks were sliced into 5-μm-thick sections for further experiments. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed following standard procedures described previously.44 Anti-CD66b antibody (clone G10F5, BD Biosciences, diluted 1/100) and anti-CD8 antibody (clone C8/144B, DAKO, ready-to-use) were used as primary antibodies. Immunoreactivity of both antibodies was determined on 20 full-face tissue sections of RCC. Anti-mouse IgG1 antibody (ab91353, Abcam, diluted 1/100) was used as negative control.

Evaluation of CD66b+ TINs and CD8+ T cells

An investigator (J.W) previously unaware of the patients’ clinical data quantified CD66b+ TINs of each tumor core under 5 independent intratumoral fields of × 100 magnification (Figure 1), each field away from necrotic regions. The total number of TINs was added up, and the density of TINs was calculated (cells/mm2). If no TINs were observed in both tumor cores from the same tumor sample, then the sample was defined as TINs-absent. Otherwise the sample was defined as TINs-present. The results were re-examined by the same investigator (J.W) after some time to ensure reproducibility, and was checked by another observer (L.L) for randomly-chosen samples. Intra-observer and inter-observer agreement was acceptable (κ > 0.85). The quantification of CD8+ T cells was performed following the same procedures, and the exact density of CD8+ T cells in each tumor core was counted (cells/mm2).

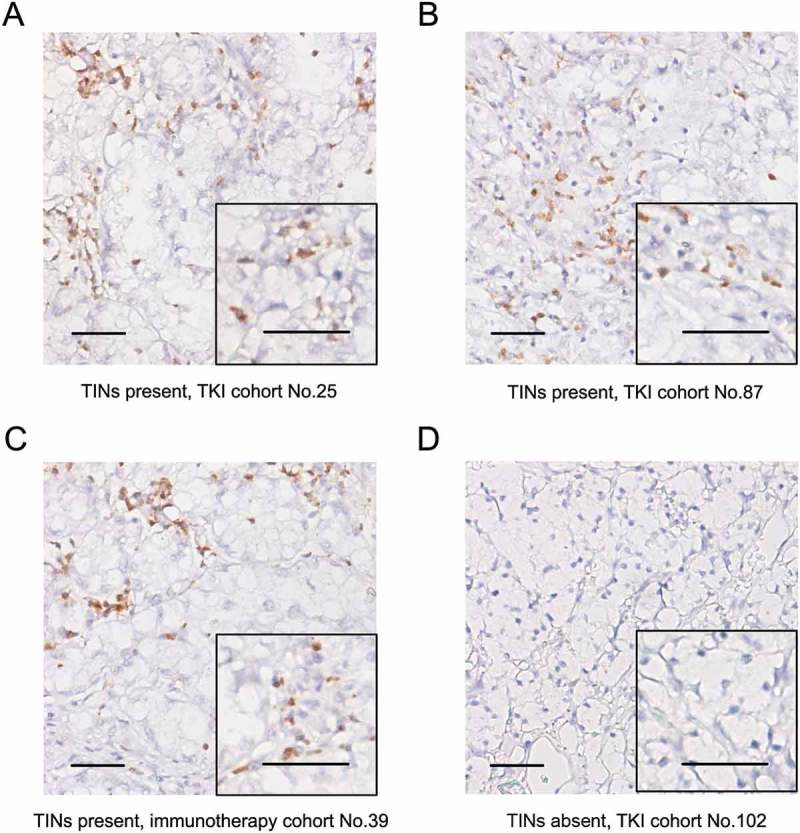

Figure 1.

Evaluation of tumor-infiltrating neutrophils (TINs) by immunohistochemistry in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. (A-D) Representative microphotographs of TINs-present (A-C) and TINs-absent (D) samples. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square test, Fisher’s exact analysis or Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, and the continuous variables were analyzed by t-test or Wilcoxon signed ranks test, if appropriate. Spearman’s correlation test was applied for correlational analyses. Cohen’s kappa coefficient test was applied for assessing inter-observer and intra-observer agreement. Survival analyses were performed by Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank test and Cox hazards regression model. Multivariate Cox regression was applied to identify independent prognostic factors. Differential expression analysis of genomic data was performed by Limma moderated t-test, and genes with FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.001 and fold change > 1.4 were regarded as differentially expressed. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY), R software version 3.1.2 with the “bioconductor” package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org/), and FunRich version 3.0.45 For all statistical analyses, two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The flow chart of the study is presented in Supplementary Figure S1. The presence of TINs was detected in 271 patients with mRCC. Supplementary Table S1 presents the baseline characteristics of all patients. Of all the 271 patients included, 189 (69.7%) were men, and the median age of all patients was 57.8 years. Two hundred and twenty (81.2%) patients had metastatic clear cell RCC. The median follow-up time was 67.2 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 44.1–90.3] by reverse Kaplan-Meier estimator.37 The study cohort was divided into 2 independent cohorts according to therapeutic regimens – a TKI cohort of 111 patients receiving sunitinib or sorafenib as systemic therapy, and an immunotherapy cohort of 160 patients historically receiving IL-2/IFN-α based immunotherapy.

Tumor-infiltrating neutrophils in mRCC tissues

TINs exhibited membranous IHC staining of CD66b (Figure 1). The presence of TINs varied in mRCC samples from different patients. A total of 50 (45.0%) patients in the TKI cohort and 73 (45.6%) patients in the immunotherapy cohort were identified as TINs-present (Figure 1(a–1c)), while the others were TINs-absent (Figure 1(d)). We assessed the association between TINs and clinicopathologic features (Supplementary Table S2), and no significant association was observed. No association was found between TINs and peripheral neutrophil count, either in the TKI cohort (p = 0.654) or in the immunotherapy cohort (p = 0.295) (Supplementary Figure S2).

Tins associated with disease outcome in TkI-treated patients

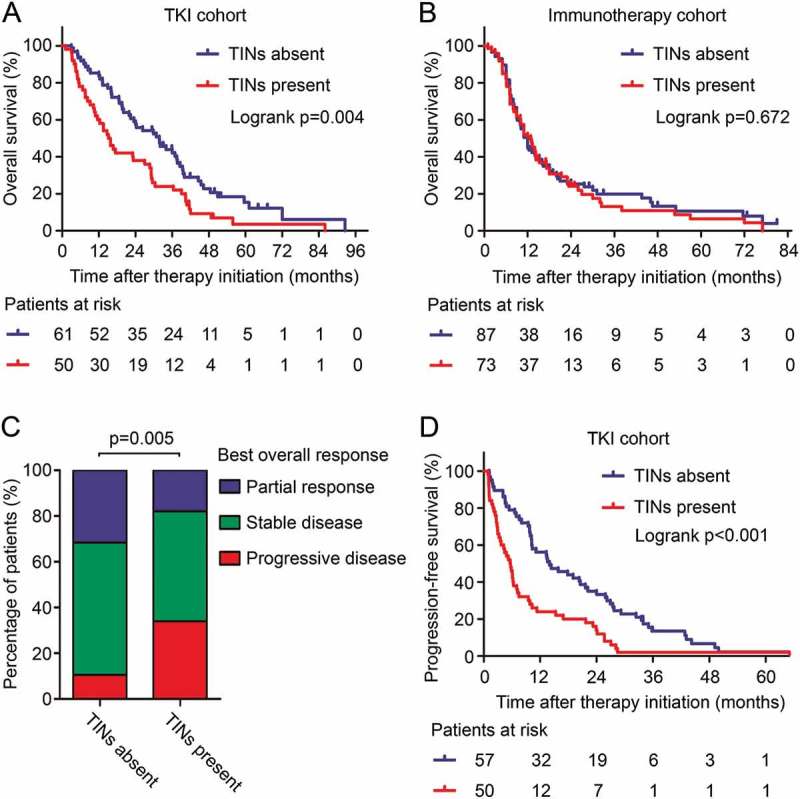

For all patients, the median OS was 15.1 months (95% CI 12.8–17.4 months) and the median PFS was 9.8 months (95% CI 7.3–12.3 months). To discover the prognostic value of TINs in mRCC patients under different therapeutic regimens, we applied survival analysis in the TKI cohort and the immunotherapy cohort. The presence of TINs was associated with short OS in the TKI cohort (Log-rank p = 0.004, Figure 2(a)), but not in the immunotherapy cohort (Log-rank p = 0.672, Figure 2(b)). Univariate Cox regression analysis also identified the presence of TINs as a prognostic factor in the TKI cohort (HR, 1.776; 95% CI, 1.191–2.650; p = 0.005), but not in the immunotherapy cohort (HR, 1.074; 95% CI, 0.767–1.505; p = 0.667) (Supplementary Table S3). The independent prognostic value of TINs was further identified (HR, 2.078; 95% CI, 1.352–3.195; p = 0.001, Table 1) by a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model including other prognostic factors as histologic type, TNM stage at diagnosis, number of organs involved by metastases, MSKCC risk group and systemic therapy regimen. Moreover, TINs acted as a robust prognostic factor in both clear cell RCC (p = 0.025, Supplementary Figure S3A) and non-clear cell RCC (p = 0.004, Supplementary Figure S3B). In subgroups divided by initial tumor stage at first diagnosis, TINs were associated with poor survival in both the stage I-III subgroup and the stage IV subgroup (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 2.

TINs associated with patients’ survival in TKI-treated mRCC. (A and B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in the TKI cohort (A) and the immunotherapy cohort (B). p values, log-rank test. (C) Response rate to TKI therapy in mRCC patients grouped by the presence of TINs. p value, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. (D) Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival in the TKI cohort. p values, log-rank test.

Table 1.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis for overall survival in the TKI cohort of metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients.

| Variables | TKI cohort (n = 111) |

|

|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) † | p value † | |

| Histologic type | 0.002 | |

| Non-clear cell vs clear cell type | 2.368 (1.377–4.072) | |

| TNM stage at diagnosis | 0.296 | |

| IV vs I-III | 0.773 (0.477–1.252) | |

| Number of organs with metastases* | 0.067 | |

| ≥ 2 vs 1 | 1.533 (0.970–2.423) | |

| MSKCC risk group | < 0.001 | |

| Favorable | 1 [Reference] | |

| Intermediate | 2.144 (1.270–3.619) | |

| Poor | 6.163 (2.957–12.844) | |

| Systemic therapy | 0.292 | |

| Sorafenib vs sunitinib | 1.283 (0.807–2.039) | |

| Tumor infiltrating neutrophils | 0.001 | |

| Present vs absent | 2.078 (1.352–3.195) | |

Abbreviations: HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

*Number of organs involved by metastases at the initiation of systemic therapy.

†Data obtained from Cox proportional hazards models. p Values< 0.05 were marked in bold font.

Neutrophil infiltration also indicated undesirable TKI therapy response (p = 0.005, Figure 2(c)) in mRCC. More patients in the TINs-present group developed progressive disease just after TKI treatment (17 patients, 34.0%), compared with the TINs-absent group (6 patients, 10.5%). Moreover, PFS in the TINs-present group was also shorter than the TINs-absent group (Log-rank p < 0.001, Figure 2(d)). The above results indicated close relationship between TINs and TKI resistance.

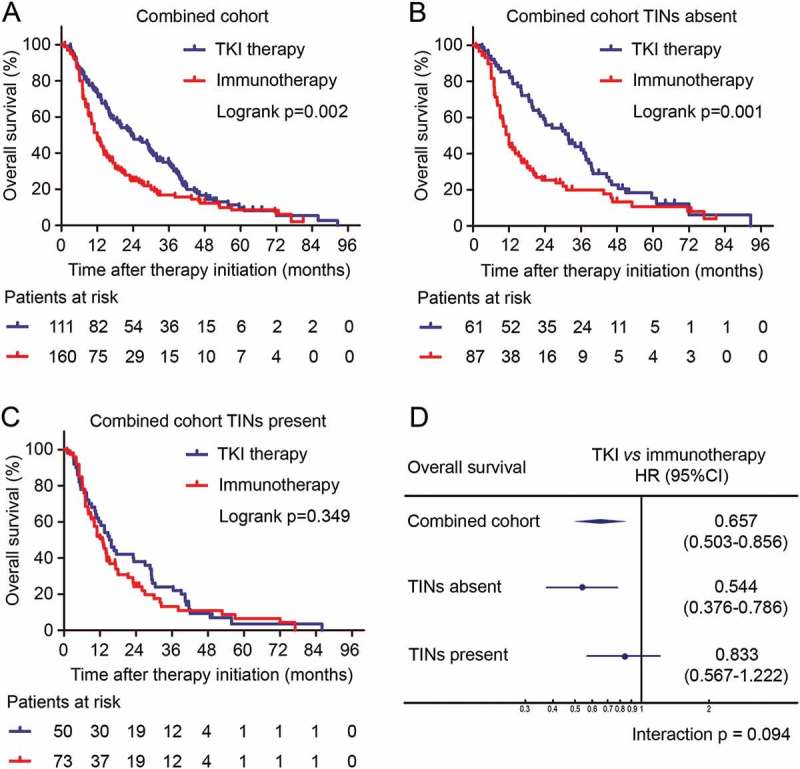

TINS and TKI therapy benefit

TKI therapy has shown superior survival benefit compared with IL-2 or IFN-α immunotherapy in stage III clinical trials,46 as well as in our study cohort (Log-rank p = 0.002, Figure 3(a)). However, there is still no clinically available biomarker to guide the usage of TKIs. We further investigated whether TKI therapy could show different survival benefit in patients with TINs-present or TINs-absent tumors. We found that in TINs-absent patients, TKI therapy showed superior survival benefit compared with immunotherapy (Log-rank p = 0.001, Figure 3B). On the other hand, in TINs-present patients, no statistically significant difference was found between different therapeutic regimens (Log-rank p = 0.349, Figure 3(c)). A test for interaction between TKI and immunotherapy also indicated that the benefit of TKIs was superior among patients with TINs-absent tumors (HR, 0.544; 95% CI, 0.376–0.786; p value for interaction, 0.094) than patients with TINs-present tumors, although statistical significance has not been reached. These results provided an indication that TKI therapy could lead to better survival benefit than IL-2/IFN-a immunotherapy, especially in TINs-absent mRCC patients.

Figure 3.

Predictive value of TINs for TKI benefit. (A-C) Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival according to therapeutic regimens in all patients (A), TINs-absent patients (B) and TINs-present patients (C). p values, log-rank test. (D) Hazard ratios for overall survival according to therapeutic regimens in patient subgroups. HR, 95% CI and interaction p value, Cox regression model.

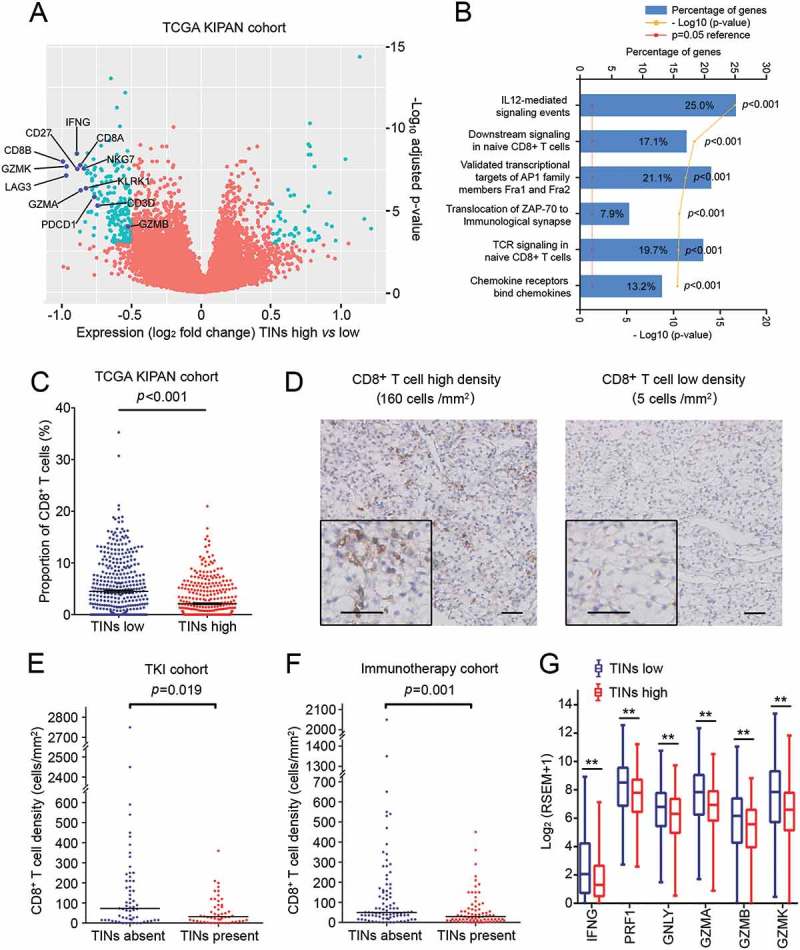

Tins related with an immunosuppressive microenvironment

The mechanism of the relationship between TINs and TKI resistance was far from clear. As VEGFR-TKI therapy mainly targets angiogenesis in RCC, we first applied correlation test between TINs and angiogenic factors in TCGA KIPAN cohort. However, no significant positive correlation was found between neutrophil infiltration and expression level of angiogenic genes including VEGFA, VEGFB, ANGPT1, ANGPT2, TEK, ANG, FGF1, FGF2 and PGF in TCGA KIPAN cohort (Supplementary Figure S5). The results indicated that angiogenesis may not be the dominant function of TINs in the RCC microenvironment.

To uncover the influence of TINs on RCC and TKI therapy, we further applied differential expression analysis between TINs-high and TINs-low tumors of TCGA KIPAN cohort. Several immune-related genes were significantly down-regulated in TINs-high tumors, including CD8+ T cell associated genes (CD3D, CD8A, CD8D, LAG3, PDCD1), NK cell associated genes (KLRK1, NKG7) and cytotoxic genes (GZMA, GZMB, GZMH, GZMK) (Figure 4(a)). Pathway enrichment analysis was also performed according to the significantly down-regulated genes. A considerable percentage of down-regulated genes were involved in CD8+ T cell associated signaling pathways, including IL12-mediated signaling events (19.3%, p < 0.001), downstream signaling in naive CD8+ T cells (14.7%, p < 0.001), and TCR signaling in naive CD8+ T cells (18.3%, p < 0.001) (Figure 4(b), Supplementary Figure S6). Moreover, the proportion of infiltrated CD8+ T cells was significantly lower in TINs-high tumors than TINs-low ones (p < 0.001, Figure 4(c)). Spearman’s correlation also showed negative correlation between TINs and CD8+ T cells by CIBERSORT deconvolution (r = -0.218, p < 0.001; Supplementary Figure S7). We also used neutrophil signature gene expression as another approach to calculate and define neutrophil infiltration high/low groups, and we also found down-regulation of CD8+ T cell signature genes in the neutrophil-high group (Supplementary Figure S8). The bioinformatic analyses implied the potential immunosuppressive role of TINs in RCC. To confirm the findings, we evaluated the number of CD8+ T cells in our study cohort by IHC staining (Figure 4(d)). The number of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells was significantly lower in TINs-present tumors compared with TINs-absent tumors, both in the TKI cohort (p = 0.019, Figure 4(e)) and the immunotherapy cohort (p = 0.001, Figure 4(f)). Apart from the number of CD8+ T cells, the functional genes of CD8+ T cells (IFNG, TNF, GZMA, GZMB, PRF1 and GNLY) was also down-regulated in TINs-high tumors of the TCGA cohort (Figure 4(g)). All the analyses indicated that TINs contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, which might be a potential mechanism for TKI resistance in RCC.

Figure 4.

TINs associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment of renal cell carcinoma. (A) Volcano plot comparing gene expression of TINs-high relative to TINs-low RCC. Differentially expressed genes are labeled in green. (B) Enriched Gene Ontology pathways of down-regulated genes in TINs-high RCC compared to TINs-low RCC. (C) CD8+ T cell proportion in TINs-high and TINs-low tumors of TCGA KIPAN cohort. Bars indicate mean value and standard error. p value, Mann–Whitney U test. (D) Representative microphotographs of CD8+ T cell high infiltration density and low infiltration density samples. Scale bars, 50μm. (E and F) CD8+ T cell density in TINs-absent and TINs-present tumors of the TKI cohort (E) and the immunotherapy cohort (F). p values, Mann–Whitney U test. (G) Expression level CD8+ T cell functional genes in TINs-high and TINs-low tumors of TCGA KIPAN cohort. * indicates p<0.05; ** indicates p<0.01; p values calculated by Mann–Whitney U test.

Discussion

Neutrophils are active players in the tumor microenvironment, showing diverse prognostic effects in different cancer types and therapeutic regimens.11,12 In the study we investigated the impact of TINs on TKI therapeutic benefit in mRCC patients. TINs were found associated with TKI resistance and undesirable outcome. The underlying resistance mechanism mediated by TINs was found associated with the immunosuppressive function of TINs via repressing CD8+ T cells.

TINs are a highly heterogeneous population of both anti-tumorigenic N1 and pro-tumorigenic N2 neutrophils.11,12 Consistent with the context-dependent role of TINs, they seemed to have dichotomized impact on systemic therapies of cancer. Illustrated by the example of chemotherapy, TINs were associated with better response in gastric cancer,22 but were associated with poor response in muscle-invasive bladder cancer.23 Regarding targeted therapies, TINs could mediate resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in PDAC47 and resistance to sorafenib in HCC.48 In our study, we identified the association between TINs and poor outcome in mRCC patients treated with TKIs (p = 0.004, Figure 2(a)). However, in those treated with IL-2/IFN-α immunotherapy, no significant prognostic value was found for TINs (p = 0.672, Figure 2(b)), which was inconsistent with a previous report concerning prognostic immune parameters in IL2-treated mRCC.25 The inconformity between the studies could be due to different regimens and different patient selection criteria, or limited sample size.

TKIs have been recommended as first-line therapy in mRCC according to stage III clinical trials,46 but adverse reactions and relatively high prize limited their clinical benefit in the real world. To prevent excessive toxic effects and to maximize therapeutic benefit, we believe it was important to identify patients who might benefit the most from TKI therapy. Consequently, we further compared treatment benefit of TKI therapy and IL-2/IFN-α immunotherapy in different patient subgroups. As a result, patients with TINs-absent RCC gained a significant survival benefit from TKI therapy, whereas those TINs-present RCC did not (Figure (3b-3d)). The results suggested TINs as a potential biomarker for TKI application and responsiveness, which could guide therapy selection in mRCC patients.

The mechanism between TINs and TKI resistance remains obscure. Neutrophils have been reported to induce angiogenesis in multiple neoplasms,49–51 and the mechanism of TKI therapeutic efficacy was frequently described as anti-angiogenesis. It is reasonable to infer that neutrophils mediate TKI resistance through angiogenesis. However, in our study we did not observed positive correlation between TINs and common angiogenic factors (Supplementary Figure S5). Recently, researchers have established the immunoregulatory effect of TKIs. TKIs have been proved to directly or indirectly stimulate anti-tumor immunity, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment may restrict the therapeutic effect of TKIs.32–34,52–54 In our study, we identified the immunosuppressive role of TINs (Figure (4a-4b)). Recent studies showed that neutrophils could mediate cancer immune escape by suppressing cytotoxic T cells. Moreover, the index iNTR (intratumoral neutrophil-to-CD8+ T cell ratio) was also found to have poor prognostic value in HCC17 and cervical cancer.18 In our study, we also found that TINs were associated with exclusion and loss of function of CD8+ T cells (Figure (4c-4g)). These evidences suggested the potential contribution of neutrophil-mediated immunosuppression to TKI resistance.

This study has several limitations. The retrospective design and limited sample size are the major limitations. Further validation in prospective observational studies with larger sample size is expected. In addition, the immunotherapy cohort in the study only included patients treated by IL-2 or IFN-α. As emerging immunotherapies including ICBs have also been clinically applied recently, we would like to investigate the predictive value of TINs for these therapies in the future. Moreover, this observational study is only a preliminary exploration of the mechanism between TINs and TKI resistance. Interventional and functional studies are needed to fully understand the underlying mechanisms.

Conclusions

This study clarified that the presence of TINs was an independent, unfavorable prognostic factor in TKI-treated mRCC patients. The study also identified TINs as an emerging biomarker for TKI therapy, which could predict therapeutic effect and survival benefit. The association between TINs and TKI resistance was potentially due to the TINs-related immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. These findings pave the way for individual therapy selection in mRCC patients, but the results are still needed to be validated in prospective, multi-centered studies with larger sample size.

Disclaimers of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Funding/Support and Role of Sponsor

This study was funded by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81472227, 81472376, 31770851, 81702496, 81702497, 81702805, 81772696), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (20174Y0042), and Zhongshan Hospital Science Foundation (2016ZSQN30, 2017ZSQN18, 2017ZSYQ26). All these study sponsors have no roles in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and in the interpretation of data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional ethical review board approved the study (Registration No. B2015-030) and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants prior to inclusion in the project. Experimental methods in this study comply with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

J. Guo and J. Xu conceived and designed the study. J. Wang, L. Liu and Q. Bai contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. J. Wang, L. Liu and Q. Bai performed the statistical analysis. J. Wang wrote the paper. J. Wang, L. Liu, Q. Bai, J. Guo and J. Xu reviewed and edited the manuscript. C. Ou, Y. Xiong, Y. Qu, Z. Wang and Y. Xia provided technical and material support. J. Guo, J. Xu, L. Liu, Q. Bai and Y. Xia contributed to funding obtaining. J. Guo and J. Xu contributed to study supervision. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili R, Bjarnason GA, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584–3590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Negrier S, Oudard S, Gore ME, Tarazi J, Hariharan S, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:552–562. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Atkins MB.. Resistance to targeted therapy in renal-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramjiawan RR, Griffioen AW, Duda DG. Anti-angiogenesis for cancer revisited: is there a role for combinations with immunotherapy? Angiogenesis. 2017;20:185–204. doi: 10.1007/s10456-017-9552-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Beijnum JR, Nowak-Sliwinska P, Huijbers EJ, Thijssen VL, Griffioen AW. The great escape; the hallmarks of resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:441–461. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.010215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojaei F, Wu X, Malik AK, Zhong C, Baldwin ME, Schanz S, Fuh G, Gerber HP, Ferrara N. Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:911–920. doi: 10.1038/nbt1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Petritsch KV Liu C Ganss P Passegue R Song E Vandenberg H Johnson S Werb Z RS, et al. HIF1alpha induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:206–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, Fingleton B, Green-Jarvis B, Shyr Y, Matrisian LM, Carbone DP, Lin PC. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford Y, Ferrara N. Tumor and stromal pathways mediating refractoriness/resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zg F, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, Gs W, Sm A. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eruslanov EB, Bhojnagarwala PS, Quatromoni JG, Stephen TL, Ranganathan A, Deshpande C, Akimova T, Vachani A, Litzky L, Hancock WW, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5466–5480. doi: 10.1172/JCI77053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millrud CR, Kagedal A, Kumlien GS, Winqvist O, Uddman R, Razavi R, Munck-Wikland E, Cardell LO. NET-producing CD16high CD62Ldim neutrophils migrate to tumor sites and predict improved survival in patients with HNSCC. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2557–2567. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen LC, Wang LJ, Tsang NM, Ojcius DM, Chen CC, Ouyang CN, Hsueh C, Liang Y, Chang KP, Chen CC, et al. Tumour inflammasome-derived IL-1beta recruits neutrophils and improves local recurrence-free survival in EBV-induced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:1276–1293. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li XF, Chen DP, Ouyang FZ, Chen MM, Wu Y, Kuang DM, Zheng L. Increased autophagy sustains the survival and pro-tumourigenic effects of neutrophils in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;62:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou SL, Dai Z, Zhou ZJ, Wang XY, Yang GH, Wang Z, Huang XW, Fan J, Zhou J. Overexpression of CXCL5 mediates neutrophil infiltration and indicates poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:2242–2254. doi: 10.1002/hep.25907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li YW, Qiu SJ, Fan J, Zhou J, Gao Q, Xiao YS, Xu YF. Intratumoral neutrophils: a poor prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma following resection. J Hepatol. 2011;54:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carus A, Ladekarl M, Hager H, Nedergaard BS, Donskov F. Tumour-associated CD66b+ neutrophil count is an independent prognostic factor for recurrence in localised cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2116–2122. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao -J-J, Pan K, Wang W, Chen J-G, Wu Y-H, Lv L, Li -J-J, Chen Y-B, Wang -D-D, Pan Q-Z, et al. The prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating neutrophils in gastric adenocarcinoma after resection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao HL, Chen JW, Li M, Xiao YB, Fu J, Zeng YX, Cai MY, Xie D. Increased intratumoral neutrophil in colorectal carcinomas correlates closely with malignant phenotype and predicts patients’ adverse prognosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen TO, Schmidt H, Moller HJ, Donskov F, Hoyer M, Sjoegren P, Christensen IJ, Steiniche T. Intratumoral neutrophils and plasmacytoid dendritic cells indicate poor prognosis and are associated with pSTAT3 expression in AJCC stage I/II melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118:2476–2485. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Liu H, Shen Z, Lin C, Wang X, Qin J, Qin X, Xu J, Sun Y. Tumor-infiltrating neutrophils is prognostic and predictive for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy benefit in patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2018;267:311–318. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou L, Xu L, Chen L, Fu Q, Liu Z, Chang Y, Lin Z, Xu J. Tumor-infiltrating neutrophils predict benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1293211. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1293211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donskov F, Hokland M, Marcussen N, Torp MH von der Maase H.. Monocytes and neutrophils as ‘bad guys’ for the outcome of interleukin-2 with and without histamine in metastatic renal cell carcinoma–results from a randomised phase II trial. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:218–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donskov F. von der Maase H.. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1997–2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen HK, Donskov F, Marcussen N, Nordsmark M, Lundbeck F. von der Maase H. Presence of intratumoral neutrophils is an independent prognostic factor in localized renal cell carcinoma. J Clinical Oncology: Official Journal Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4709–4717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santoni M, De Giorgi U, Iacovelli R, Conti A, Burattini L, Rossi L, Luca BS, Berardi R, Muzzonigro G, Cortesi E, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be associated with the outcome in patients treated with everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1755–1759. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porta C, Paglino C, De Amici M, Quaglini S, Sacchi L, Imarisio I, Canipari C. Predictive value of baseline serum vascular endothelial growth factor and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in advanced kidney cancer patients receiving sunitinib. Kidney Int. 2010;77:809–815. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chevrier S, Levine JH, Zanotelli V, Silina K, Schulz D, Bacac M, Ries CH, Ailles L, Jewett M, Moch H, et al. An Immune Atlas of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:736–49.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senbabaoglu Y, Gejman RS, Winer AG, Liu M, Van Allen EM, De Velasco G, Miao D, Ostrovnaya I, Drill E, Luna A, et al. Tumor immune microenvironment characterization in clear cell renal cell carcinoma identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant messenger RNA signatures. Genome Biol. 2016;17:231. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1092-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terme M, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, Tanchot C, Tartour E, Taieb J. Modulation of immunity by antiangiogenic molecules in cancer. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:492920. doi: 10.1155/2012/492920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desar IM, Jacobs JH, Hulsbergen-vandeKaa CA, Oyen WJ, Mulders PF, Van Der Graaf WT, Adema GJ, Van Herpen CM, De Vries IJ. Sorafenib reduces the percentage of tumour infiltrating regulatory T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:507–512. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan H, Cai P, Li Q, Wang W, Sun Y, Xu Q, Gu Y. Axitinib augments antitumor activity in renal cell carcinoma via STAT3-dependent reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68:751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adotevi O, Pere H, Ravel P, Haicheur N, Badoual C, Merillon N, Medioni J, Peyrard S, Roncelin S, Verkarre V, et al. A decrease of regulatory T cells correlates with overall survival after sunitinib-based antiangiogenic therapy in metastatic renal cancer patients. J Immunother. 2010;33:991–998. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181f4c208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version. 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, Egevad L, Epstein JI, Grignon D, Hes O, Moch H, Montironi R, Tickoo SK, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1469–1489. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delahunt B, Cheville JC, Martignoni G, Humphrey PA, Magi-Galluzzi C, McKenney J, Egevad L, Algaba F, Moch H, Grignon DJ, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading system for renal cell carcinoma and other prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1490–1504. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f0fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Liu L, Qu Y, Xi W, Xia Y, Bai Q, Xiong Y, Long Q, Xu J, Guo J. Prognostic value of SETD2 expression in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Urol. 2016;196:1363–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu H, Xu J, Zhou L, Yun X, Chen L, Wang S, Sun L, Wen Y, Gu J. Hepatitis B virus large surface antigen promotes liver carcinogenesis by activating the Src/PI3K/Akt pathway. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7547–7557. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benito-Martin A, Peinado H. FunRich proteomics software analysis, let the fun begin! Proteomics. 2015;15:2555–2556. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Figlin RA, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Négrier S, Huang X, Kim ST, Chen I, Motzer RJ. Overall survival with sunitinib versus interferon (IFN)-alfa as first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). University of Chicago Law Review. 2008;69:681–704. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phan VT, Wu X, Cheng JH, Sheng RX, Chung AS, Zhuang G, Tran C, Song Q, Kowanetz M, Sambrone A. Oncogenic RAS pathway activation promotes resistance to anti-VEGF therapy through G-CSF-induced neutrophil recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6079–6084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303302110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou SL, Zhou ZJ, Hu ZQ, Huang XW, Wang Z, Chen EB, Fan J, Cao Y, Dai Z, Zhou J. Tumor-associated neutrophils recruit macrophages and t-regulatory cells to promote progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and resistance to sorafenib. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1646. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bekes EM, Schweighofer B, Kupriyanova TA, Zajac E, Ardi VC, Quigley JP, Deryugina EI. Tumor-recruited neutrophils and neutrophil TIMP-free MMP-9 regulate coordinately the levels of tumor angiogenesis and efficiency of malignant cell intravasation. American Journal of Pathology. 2011;179:1455–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon Weeks AN, Lim SY, Yuzhalin AE, Jones K, Markelc B, Buzelli JN, Fokas E, Cao Y, Smart S, Muschel R. Neutrophils Promote Hepatic Metastasis Growth Through fibroblast growth factor (FGF)2‐dependent Angiogenesis. Hepatology. 2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.29088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shojaei F, Wu X, Zhong C, Yu L, Liang XH, Yao J, Blanchard D, Bais C, Peale FV, Van BN. Bv8 regulates myeloid-cell-dependent tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;450:825. doi: 10.1038/nature06348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camus M, Tosolini M, Mlecnik B, Pages F, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Costes A, Bindea G, Charoentong P, Bruneval P, et al. Coordination of intratumoral immune reaction and human colorectal cancer recurrence. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2685–2693. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guislain A, Gadiot J, Kaiser A, Jordanova ES, Broeks A, Sanders J, Van Boven H, De Gruijl TD, Haanen JBAG, Bex A, et al. Sunitinib pretreatment improves tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte expansion by reduction in intratumoral content of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:1241–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1735-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Js K, Ah Z, Bi R, Jl I, Elson P, Cohen P, Golshayan A, Pa R, Wood L, Garcia J, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.