Abstract

Background

Older adults with advanced CKD have significant pain, other symptoms, and disability. To help ensure that care is consistent with patients’ values, nephrology providers should understand their patients’ priorities when they make clinical recommendations.

Methods

Patients aged ≥60 years with advanced (stage 4 or 5) non–dialysis-dependent CKD receiving care at a CKD clinic completed a validated health outcome prioritization tool to ascertain their health outcome priorities. For each patient, the nephrology provider completed the same health outcome prioritization tool. Patients also answered questions to self-rate their health and completed an end-of-life scenarios instrument. We examined the associations between priorities and self-reported health status and between priorities and acceptance of common end-of-life scenarios, and also measured concordance between patients’ priorities and providers’ perceptions of priorities.

Results

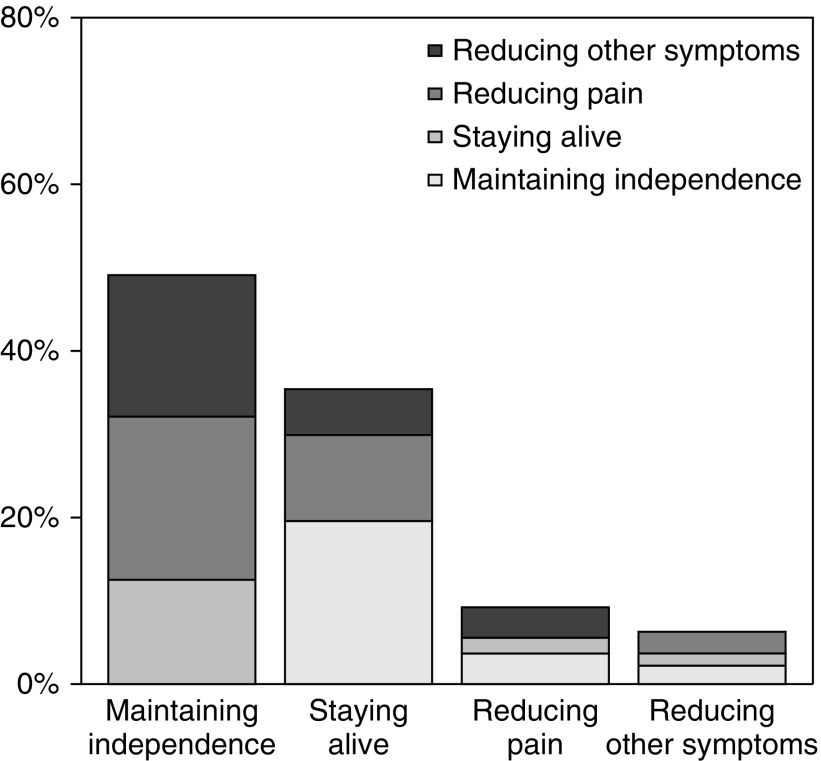

Among 271 patients (median age 71 years), the top health outcome priority was maintaining independence (49%), followed by staying alive (35%), reducing pain (9%), and reducing other symptoms (6%). Nearly half of patients ranked staying alive as their third or fourth priority. There was no relationship between patients’ self-rated health status and top priority, but acceptance of some end-of-life scenarios differed significantly between groups with different top priorities. Providers’ perceptions about patients’ top health outcome priorities were correct only 35% of the time. Patient-provider concordance for any individual health outcome ranking was similarly poor.

Conclusions

Nearly half of older adults with advanced CKD ranked maintaining independence as their top heath outcome priority. Almost as many ranked being alive as their last or second-to-last priority. Nephrology providers demonstrated limited knowledge of their patients’ priorities.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, geriatric nephrology, quality of life

CKD, common in older adults,1 is associated with multimorbidity,1 decreased quality of life,2,3 and increased mortality.4 For older adults with CKD, death is more likely than progression to ESRD until very late in the disease course.5 In those whose CKD progresses to ESRD, maintenance dialysis initiation may contribute to disability6,7 and lower satisfaction with life8 and may not confer a substantial survival benefit.9–12 Moreover, patients with ESRD appear to receive high-quality end-of-life care less often than their counterparts with cancer, dementia, or other chronic illnesses.13,14 Given these findings, national nephrology organizations have advocated for a patient-centered approach to treatment decisions in advanced CKD.15,16 It remains unclear, however, whether nephrologists devote enough time to understanding their patients’ values before making treatment recommendations to older adults with advanced CKD.17–19

Advance care planning involves discussions between patients, the important people in their lives, and their clinicians about possible clinical trajectories and personal values in order to inform treatment decisions.20 Older patients with advanced CKD and multimorbidity are likely to have lived experiences that have shaped their health outcome priorities, which might include control of pain and other symptoms, maximizing life expectancy or independence, or minimizing treatment burden for both themselves and their caregivers. In pursuit of these priorities, trade-offs are inevitable.21 Ideally, advance care planning conversations increase concordance between patients’ health priorities and providers’ perceptions of these priorities, because lack of concordance may drive care that is inconsistent with patients’ values. Yet few studies have characterized patient health outcome priorities and concordance with their providers’ perceptions of these priorities in CKD.

To that end, in this study we elicited the health outcome priorities of older adults with advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD. We then examined the association between patients’ priorities and self-reported health, as well as the association between priorities and acceptance of common end-of-life scenarios. Finally, we measured concordance between patients’ priorities and providers’ perceptions of these priorities and assessed patient-level predictors of concordance.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

We approached older adults (age ≥60 years) with non–dialysis-dependent CKD stages 4–5 who were seen in follow-up by a nephrology provider at an academic clinic in the southern United States from November of 2016 to January of 2018 to participate in research examining their health values and communication with their nephrology providers. As described in previous related studies,19,22 we excluded patients with dialysis dependence, prior kidney transplant, and possible AKI, as well as patients on their initial visit with a particular nephrology provider. In this clinic, it is the standard of care to refer patients for education in CKD and renal replacement options when they reach CKD stage 4.

Of 293 patients approached, 16 (5.5%) declined to participate and 6 (2.0%) found the health outcome prioritization measure distressing, asked to skip the assessment, and were therefore excluded from this analysis. We report results for the remaining 271 participants. We also enrolled nephrology providers who deliver outpatient CKD care at this clinic. All 13 attending physicians and one advanced practitioner at the clinic chose to participate. We obtained written informed consent from patients and providers. Patients were permitted to skip any measure. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Health Outcome Prioritization

Before patients prioritized their health outcomes, the trained research staff (all physicians) asked several related questions to determine whether the patients had discussed their health values and priorities with a doctor in the past, how well they thought their caregivers knew their goals of care, and whether they had advance care planning documents. Patients then completed a previously validated health outcome prioritization tool.21 The four outcomes were (1) “maintaining independence”; (2) “keeping you alive”; (3) “reducing or eliminating pain”; and (4) “reducing or eliminating dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath” (see Supplemental Material). We adapted the instrument script to a sixth-grade reading level but otherwise maintained its content and general format.

On the instrument, patients ranked the four health outcomes from highest to lowest priority using an enlarged visual analog scale (VAS), with 100 representing the highest priority and 0 the lowest priority. Patients could not rank two priorities equally. When patients were ranking pain and symptom relief, the staff asked them to imagine they were experiencing pain or symptoms at that moment. The staff then confirmed the patients’ rankings by reporting back the order of priorities on the VAS and allowing the patients to make adjustments if necessary. Because the health outcome priorities demonstrated excellent reliability on prior testing but the VAS scores demonstrated substantial variation, we a priori chose to capture rank orderings only.21

Using the same VAS, the nephrology providers ranked a patient’s health outcome priorities according to their perception of them immediately after the same visit in which the patient completed the study instruments. Providers could opt to respond that they had no insight on the patient’s priorities. To minimize biases, patients’ priorities and providers’ perceptions of those priorities were gathered after the completion of the clinic visit, so as not to prompt a discussion regarding priorities if it was not already planned, and providers were not allowed to view patient responses at any point during this study.

End-Of-Life Scenarios

We used a publicly available advance care planning workbook to capture patient preferences in common end-of-life scenarios.23 Research staff introduced the material, spoke about the importance of understanding the patients’ responses should their illness worsen, and asked patients to carefully consider their values and preferences when answering the items. Each item prompted the patients to judge whether they would find life in a described condition “difficult but acceptable,” “worth living, but just barely,” or “not worth living.” The research staff reminded the patients to consider each of the described scenarios as permanent. Patients were permitted to respond “Can’t answer now” if they were unable to provide a response or found the questions distressing. Patients could also skip items they found distressing, in which case the research staff would provide emotional support if the patients appeared upset. For data analysis, we chose to collapse the responses “difficult but acceptable” and “worth living, but just barely” into a single category, because both convey that the patient would find life worth living in that state.

Subjective Health

We assessed patients’ self-rated health by asking, “In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” The answer to this question has previously been shown to identify patients with CKD at high risk of disease progression and death.24

Patient Characteristics and Other Measures

Upon enrollment, patients completed a brief questionnaire to collect information on sociodemographics and medical conditions. We also performed manual chart reviews and structured data abstraction to supplement this information with documented comorbidities and common clinical measurements (e.g., vital signs, lab values, etc.) from the prior 12 months. With information on comorbidities, we calculated a Charlson comorbidity index for each patient.25

We measured independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs with the Katz26 and Lawton27 indices, respectively. Scores on the Katz index range from 0 to 5, whereas Lawton index scores range from 0 to 8. On both scales, higher scores indicate greater independence. We used the Palliative care Outcome Scale Symptoms Renal to assess patient symptoms.28 This self-administered questionnaire captures the presence and severity of 17 symptoms experienced over the prior week using a five-point scale ranging from “absent” (0) to “overwhelming” (4). The individual symptom scores are summed to generate a total score, ranging from 0 to 68.

Statistical Analyses

We present patients’ characteristics as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categoric variables. We report all agreements as absolute agreement and weighted κ statistics with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Absolute agreement occurred when the patient and provider assigned the same ranking to a specific priority. The degree of overall agreement between patients and providers for all priorities simultaneously was summarized with the weighted κ statistic using rank-difference weights. A weighted κ score of 1 indicates perfect agreement; 0 indicates the level of agreement expected by chance alone; a negative score indicates agreement worse than chance. We also calculated a weighted κ statistic for each specific priority by treating patients as a single rater and providers as a second rater. We analyzed summary measures of patient-provider concordance with a cumulative probability proportional odds model including patient age, sex, race, marital status, education, income, insurance, body mass index, and comorbidities. We tested the association between categoric variables with chi-squared statistics. P values of <0.05 are considered statistically significant. We performed all analyses using R (version 3.4.4).

Results

A total of 271 patients, 45.4% women, with median age 71 years (IQR, 66–77), enrolled in the study (Table 1). The median eGFR at enrollment was 22.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (IQR, 17.0–28.2) by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.29 Almost half of patients had diabetes mellitus, whereas 43.2% had a history of cardiovascular disease, 24.4% had a history of heart failure, and 24.7% had a history of cancer.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | n=271 |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 71 (66, 77) |

| Women | 123 (45.4) |

| Race | |

| Black | 50 (18.5) |

| Nonblack | 221 (81.5)a |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 175 (64.6) |

| Divorced | 31 (11.4) |

| Widowed | 48 (17.7) |

| Single/other | 17 (6.3) |

| Highest education level | |

| Less than high school diploma | 29 (10.7) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 68 (25.1) |

| Some college | 59 (21.8) |

| College degree or higher | 115 (42.4) |

| Yearly household incomeb | |

| <$20,000 | 42 (15.5) |

| $20,000–39,999 | 67 (24.7) |

| $40,000–59,999 | 54 (19.9) |

| $60,000–79,999 | 43 (15.9) |

| $80,000–99,999 | 16 (5.9) |

| ≥$100,000 | 46 (17.0) |

| Insurance type | |

| Private | 75 (27.7) |

| Medicaid/medical assistance | 11 (4.1) |

| Medicare | 185 (68.3) |

| ADL score | 5 (5, 5) |

| iADL score | 8 (7, 8) |

| POS-S Renal score | 9 (5, 15) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2c | 22.6 (17.0, 28.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.2 (25.9, 35.2) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 5 (3, 6) |

| Specific comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 265 (97.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 134 (49.4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 86 (31.7) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 50 (18.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 31 (11.4) |

| All cardiovascular disease | 117 (43.2) |

| Heart failure | 66 (24.4) |

| Cancer | 67 (24.7) |

| Chronic lung disease | 38 (14.0) |

Continuous variables expressed as median (IQR); categoric variables expressed as n (%). iADL, instrumental ADLs; POS-S Renal, Palliative care Outcome Scale–Symptoms Renal; BMI, body mass index.

218 white, three other.

268 responses, because 3 (1.1%) declined to answer.

As calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation.29

Approximately half of patients (n=133; 49.1%) selected maintaining independence as their top health outcome priority (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1), significantly more than the next most common choice, staying alive (n=96; 35.4%; P=0.002). Comparatively fewer patients chose reducing pain or reducing other symptoms as their top health outcome priority (9.2% and 6.3%, respectively). Notably, almost three-quarters of the patients (n=202; 74.5%) ranked maintaining independence as their first or second priority, and nearly half of the patients (n=132; 48.7%) ranked staying alive as their last or next to last priority (Supplemental Table 2). There was no significant relationship between patients’ self-rated health and top priority ranking (P=0.33) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Patients’ first and second choices for health outcome priorities. The proportion of patients who designated a particular outcome as first priority is displayed as a main bar; the proportion of those patients who designated a particular outcome as second priority is displayed as a sub-bar.

Table 2.

First-choice health outcome priority, according to self-rated health status

| Self-Rated Health Status | Maintaining Independence (n=133) | Staying Alive (n=91) | Reducing Pain (n=25) | Reducing Other Symptoms (n=17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent (n=3) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Very good (n=39) | 20 (51.3) | 16 (41.0) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.6) |

| Good (n=100) | 56 (56.0) | 27 (27.0) | 11 (11.0) | 6 (6.0) |

| Fair (n=102) | 46 (45.1) | 34 (33.3) | 12 (11.8) | 10 (9.8) |

| Poor (n=22) | 9 (40.9) | 13 (59.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

n=266 (five patients missing because they did not answer self-rated health question). Numbers expressed as n (%). Percentages are from row totals. Chi-squared test of overall association: P=0.18.

Patients’ top health outcome priorities according to their acceptance of common end-of-life scenarios are shown in Table 3. In general, patients who prioritized maintaining independence were more likely to say life is not worth living (i.e., not acceptable) in the hypothetic scenarios. Specifically, top priority and scenario acceptance were associated for “No longer can think or talk clearly” (P<0.01), “No longer can respond to commands or requests” (P<0.01), “Are in severe discomfort most of the time” (P=0.04), “No longer can control your bladder or bowels” (P=0.01), “Live in a nursing home permanently” (P=0.004), and “Are an emotional or financial burden to family” (P=0.001). Although more patients whose top priority was maintaining independence reported that life would not be worth living if dependent on dialysis, overall there was no significant relationship between top priority and acceptance of this scenario (P=0.22).

Table 3.

First-choice health outcome priority and acceptance of common end-of-life scenarios

| Common End-of-Life Scenario | Maintaining Independence (n=130) | Staying Alive (n=82) | Reducing Pain and Other Symptoms (n=42) | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No longer can recognize or interact with family or friends | 0.19 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 55 (42.3) | 48 (58.5) | 20 (47.6) | |

| Not worth living | 55 (42.3) | 24 (29.3) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Can’t answer now | 20 (15.4) | 10 (12.2) | 8 (19.0) | |

| No longer can think or talk clearly | 0.01 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 59 (45.4) | 52 (63.4) | 22 (52.4) | |

| Not worth living | 60 (46.2) | 22 (26.8) | 11 (26.2) | |

| Can’t answer now | 11 (8.5) | 8 (9.8) | 9 (21.4) | |

| No longer can respond to commands or requests | 0.01 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 46 (35.4) | 46 (56.1) | 18 (42.9) | |

| Not worth living | 68 (52.3) | 26 (31.7) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Can’t answer now | 16 (12.3) | 10 (12.2) | 10 (23.8) | |

| No longer can walk but get around in a wheelchairb | 0.28 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 109 (84.5) | 74 (90.2) | 35 (83.3) | |

| Not worth living | 10 (7.8) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Can’t answer now | 10 (7.8) | 7 (8.5) | 5 (11.9) | |

| No longer can get outside and must spend all day at home | 0.22 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 108 (83.1) | 75 (91.5) | 34 (81.0) | |

| Not worth living | 8 (6.2) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Can’t answer now | 14 (10.8) | 5 (6.1) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Are in severe untreatable pain most of the time | 0.14 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 52 (40.0) | 43 (52.4) | 18 (42.9) | |

| Not worth living | 62 (47.7) | 25 (30.5) | 16 (38.1) | |

| Can’t answer now | 16 (12.3) | 14 (17.1) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Are in severe discomfort most of the time (such as nausea, diarrhea)b | 0.04 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 73 (56.6) | 59 (72.0) | 23 (54.8) | |

| Not worth living | 43 (33.3) | 13 (15.9) | 11 (26.2) | |

| Can’t answer now | 13 (10.1) | 10 (12.2) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Are on a kidney dialysis machine to keep you aliveb | 0.22 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 77 (59.7) | 61 (74.4) | 28 (66.7) | |

| Not worth living | 32 (24.8) | 11 (13.4) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Can’t answer now | 20 (15.5) | 10 (12.2) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Are on a breathing machine to keep you alive | 0.18 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 37 (28.5) | 34 (41.5) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Not worth living | 76 (58.5) | 37 (45.1) | 24 (57.1) | |

| Can’t answer now | 17 (13.1) | 11 (13.4) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Need someone to take care of you 24 h a day | 0.15 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 59 (45.4) | 52 (63.4) | 23 (54.8) | |

| Not worth living | 52 (40.0) | 23 (28.0) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Can’t answer now | 19 (14.6) | 7 (8.5) | 5 (11.9) | |

| No longer can control your bladder or bowels | 0.01 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 60 (46.2) | 56 (68.3) | 25 (59.5) | |

| Not worth living | 51 (39.2) | 15 (18.3) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Can’t answer now | 19 (14.6) | 11 (13.4) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Live in a nursing home permanently | 0.004 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 60 (46.2) | 59 (72.0) | 20 (47.6) | |

| Not worth living | 52 (40.0) | 15 (18.3) | 15 (35.7) | |

| Can’t answer now | 18 (13.8) | 8 (9.8) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Are an emotional or financial burden to family | 0.001 | |||

| Difficult, but acceptable/Worth living, but just barely | 42 (32.3) | 46 (56.1) | 16 (38.1) | |

| Not worth living | 69 (53.1) | 21 (25.6) | 16 (38.1) | |

| Can’t answer now | 19 (14.6) | 15 (18.3) | 10 (23.8) |

Numbers expressed as n (%). Total n=254 (17 of the 271 participants with health outcome priorities were enrolled before inclusion of the end-of-life scenarios tool), except where indicated.

Test of association between first priority and scenario responses. P value calculated using chi-squared test.

n=253.

Nephrology providers’ perceptions of their patients’ top health outcome priorities were only correct in a minority of cases (35.2%; 95% CI, 29.7% to 41.2%) (Table 4), with an expected chance agreement of 25%. Notably, in 18.0% (95% CI, 11.9% to 24.7%) and 20.3% (95% CI, 14.2% to 27.0%) of cases, providers ranked the patient’s top priority as the perceived third or fourth priority, respectively. For top-ranked health outcome priority, the weighted Cohen’s κ for patient-provider concordance was 0.10 (95% CI, −0.21 to 0.40). The overall measure of patient-provider concordance considering each priority simultaneously yielded a weighted Cohen’s κ of 0.10 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.15). Patient-provider concordance for any individual health outcome priority was similarly poor (weighted κ<0.1 for all four health priorities at any rank; Table 5).

Table 4.

Patients’ (columns) and their providers’ (rows) first choices for health outcome priorities

| Provider Choice | Patient Choice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maintaining Independence | Staying Alive | Reducing Pain | Reducing Other Symptoms | Total | |

| Maintaining independence | 50 (18.5) | 31 (11.4) | 9 (3.3) | 4 (1.5) | 94 (34.7) |

| Staying alive | 50 (18.5) | 38 (14.0) | 9 (3.3) | 10 (3.7) | 107 (39.5) |

| Reducing pain | 15 (5.5) | 9 (3.3) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) | 29 (10.7) |

| Reducing other symptoms | 12 (4.4) | 15 (5.5) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 31 (11.4) |

| Provider unsure | 6 (2.2) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.7) |

| Total | 133 (49.1) | 96 (35.4) | 25 (9.2) | 17 (6.3) | 271 (100) |

Numbers expressed as n (%).

Table 5.

Absolute agreement and weighted κ values for patient-provider concordance for health outcome priorities

| Health Outcome Priority | Absolute Agreement, % (95% CI) | Weighted κa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Maintaining independence | 31 (26 to 37) | −0.02 (−0.23 to 0.19) |

| Staying alive | 26 (21 to 31) | 0.01 (−0.20 to 0.21) |

| Reducing pain | 30 (24 to 35) | 0.01 (−0.18 to 0.20) |

| Reducing other symptoms | 27 (22 to 33) | −0.07 (−0.47 to 0.32) |

Calculated by treating patients as one rater and providers as another rater.

Although the 14 providers ranked health outcome priorities for variable numbers of patients, from as few as one patient to as many as 51 patients, nine providers assessed at least ten patients, and five providers assessed at least 25 patients. Even for the providers who saw the most patients, the highest weighted κ for any priority at any rank was 0.18, and all other weighted κs were ≤0.1 (data not shown). No patient characteristic (including sociodemographics and comorbidities) was significantly associated with concordance in health outcome priority rankings (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we found that nearly half of our cohort of older patients with non–dialysis-dependent advanced CKD ranked maintaining independence as their top heath outcome priority, and almost as many ranked staying alive as their last or second-to-last priority. Yet their nephrology providers’ knowledge of their priorities was poor, and patients’ impression of their own health did not predict their top health outcome priority. These priorities appear to have important implications for advance care planning, because patients’ stated acceptance of many common end-of-life scenarios was significantly associated with their top health outcome priority.

Our study population’s ordering of top priorities (maintaining independence, staying alive, reducing pain, reducing other symptoms) mirrors that seen in the sample of older adults with multiple chronic diseases in whom the health outcome priorities tool was validated.21 Also identical in the two samples is the most common lowest priority of staying alive among those who ranked maintaining independence as their top priority. Approximately 70% of people in the health outcome priorities tool study, drawn from senior centers and a senior living facility, had four or more chronic conditions. Despite sample recruitment in different settings, the basic similarity in health outcome priorities in the two studies suggests that older age and multimorbidity likely drive health priorities more than any particular medical problem does.

That many patients prioritized maintaining independence above all else is of particular interest in light of prior research suggesting that, among the elderly, initiation of maintenance dialysis is associated with worsening functional dependence,6,7 decline in executive function,30 and prolonged periods spent in hospitals or skilled nursing facilities.31 Given the growing body of evidence showing that maintenance dialysis might not repair or even preserve the aspects of patients’ lives most important to some of them, nephrologists must be aware of their patients’ health outcome priorities to adequately counsel their older advanced CKD patients regarding the benefits and burdens of initiating maintenance dialysis. The lack of a significant relationship between top priority and acceptance of maintenance dialysis in our study perhaps speaks to patients’ lack of education on likely trajectories after dialysis initiation and our somewhat limited sample size. Further data regarding symptom burden, quality of life, and survival with maintenance dialysis versus conservative management would aid United States nephrologists as they try to tailor treatment recommendations to their patients’ health outcome priorities.32

Although some studies in patients with ESRD suggest that avoiding death is a lower priority than maximizing daily well-being,33 the choice to forego maintenance dialysis in favor of conservative management of advanced CKD is uncommon in the United States. This apparent contradiction likely results from multiple factors, with low patient-provider concordance in health outcome priorities being one of them. Our findings reinforce previous research that has shown that patient-provider communication in the period leading up to maintenance dialysis initiation is suboptimal.34–37 In at least one study, many patients suspected that their nephrology providers might not have time for in-depth discussions,37 and nephrologists have confirmed that they do not feel incentivized to engage in such discussions.38 Moreover, effective communication about topics such as health outcome priorities requires training and, despite growing recognition of the need for such training, nephrology fellows in the United States report they are still not receiving enough of it.39,40 Communication skills training designed for nephrologists has demonstrated the potential to improve capabilities in this area41; whether it could increase patient-provider concordance in health outcome priorities remains to be seen. Although this study dealt with CKD patients not yet on dialysis, provider awareness of patient health outcome priorities remains pertinent even for patients who start maintenance dialysis. After a patient becomes acquainted with the lived experience of dialysis, perhaps in a time-limited trial, the conversation on whether to continue can center upon whether dialysis is helping to achieve a particular prioritized health outcome, and whether the patient’s priorities are in fact evolving.42

Along the same lines, a discussion of priorities should start but then not end the shared decision-making process. If the destination in such a process is the patient living and dying in circumstances that match his or her preferences as much as possible, then health outcome priorities should be viewed as guideposts toward that destination. At times, though, the patient’s chosen path might not clearly follow those guideposts. In this study, even among patients who ranked maintaining independence as their top health outcome priority, when they had to provide specific preferences on a different instrument, 45%, 46%, and 29% responded that life would still be worth living if they required 24-hour care, permanently resided in a nursing home, or were dependent on a breathing machine to stay alive, respectively. Many observers would say that patients in such conditions could not be considered independent. One possibility is that terms such as “maintaining independence” and “24-hour care” mean different things to different people. For example, some individuals are accustomed to extensive assistance with instrumental ADLs not because of poor health but because of family habits; they may see themselves as independent despite the presence of a family caregiver nearly around the clock. It seems more likely, however, that as in other areas of life, people do not always make choices that are consistent with their stated priorities. In such cases, the poor concordance between patients’ health outcome priorities and their nephrology providers’ perceptions of such is hardly surprising. Rather than finding frustration in this inconsistency, we would suggest that providers forge ahead in the shared decision-making process, asking whether the priorities serving as guideposts are really the ones pointing to the patient’s preferred destination, and then selecting new guideposts and paths as needed.

Our study had several strengths. First, patient and provider participation rates were high, limiting selection bias, and the number of patients enrolled was relatively large compared with other published research on this subject. Second, the health outcome prioritization tool we used was specifically developed for older adults with multimorbidity, and the patient-based subjective health assessment measure we used has demonstrated predictive validity in the CKD population.24 Third, we specifically targeted older patients with advanced stages of CKD, for whom the process of health outcome prioritization is most pressing and for whom evidence suggests the likely stability of end-of-life preferences over time and with changes in health status.43

We also acknowledge several limitations. First, this was a single-center study of a clinic population with a relatively high level of educational attainment, perhaps limiting generalizability. Second, the clinical implications of the limited concordance between patients and providers in health outcome priorities require further investigation. Although studies examining end-of-life care in advanced CKD indicate that patients may receive care that is not consistent with their stated values and preferences, it remains to be seen whether improving concordance would improve the quality of end-of-life care. Third, our study dealt with only patients, not their surrogates, even though it is surrogates who are often tasked with making the weightiest decisions toward the end of life. Fourth, older patients with advanced CKD frequently have cognitive impairment, which may have limited patients’ ability to understand and respond to the health outcome prioritization tool. Notably, however, the presence of dementia in our patient sample was quite low (data not shown). Finally, patients’ responses to hypothetic situations may not reflect how they would respond to the same situation in real life. Advance care planning exercises, including the ones described in this cross-sectional study, must be paired with longitudinal studies to assess the durability of preferences over time and through crises. Although many United States nephrology providers express skepticism that patients who initially voice a preference to forego dialysis will maintain that preference as they get sicker, data from other Western countries suggest durability of this preference.10,11 We do acknowledge that ever-changing cultural norms influence these decisions, though.

Taken together, the findings from this study raise the possibility that engaging older adults with advanced CKD in an explicit health outcome prioritization process might enrich their nephrology providers’ understanding of what matters most to them, enhancing the care experience for patients and providers alike.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and providers at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center nephrology clinic for their participation during this study.

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants K24 DK62849 (T.A.I.) and K23DK090304 (K.A.-K.) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards UL1TR000445 and UL1TR002243, all from the National Institutes of Health; the Satellite Health Norman Coplon Extramural Grant Program (K.A.-K.); and the Vanderbilt Center for Kidney Disease. The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to report the findings.

A poster presenting these findings will be presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week, October 23–28, 2018 in San Diego, California.

H.S. and K.A.-K. designed the study; N.N.M., H.S., and K.A.-K. collected the data; A.B. and T.G.S. analyzed the data; all authors participated in data interpretation; S.J.R. and K.A.-K. drafted the manuscript; S.J.R., C.R.-C., E.D.S., A.B., T.G.S., M.H.E.-S., L.L., T.A.I., and K.A.-K. revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018060657/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material

Health outcome prioritization tool script.

Supplemental Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients by first-choice health outcome priority.

Supplemental Table 2. All choices for health outcome priorities.

References

- 1.Stevens LA, Li S, Wang C, Huang C, Becker BN, Bomback AS, et al.: Prevalence of CKD and comorbid illness in elderly patients in the United States: Results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis 55[Suppl 2]: S23–S33, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlman RL, Finkelstein FO, Liu L, Roys E, Kiser M, Eisele G, et al.: Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): A cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 658–666, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClellan WM, Abramson J, Newsome B, Temple E, Wadley VG, Audhya P, et al.: Physical and psychological burden of chronic kidney disease among older adults. Am J Nephrol 31: 309–317, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, et al.: Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, Bacchetti P, Garg AX, Kaufman JS, et al.: Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2758–2765, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M: Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 361: 1612–1613, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K: Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2002–2009, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K: Choosing not to dialyse: Evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract 95: c40–c46, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ: Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 633–640, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: Comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1608–1614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, discussion 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renal Physicians Association : Shared Decision-making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, Fink JC, Jaber BL, Linas SL, et al.: American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force : Critical and honest conversations: The evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1664–1672, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luckett T, Sellars M, Tieman J, Pollock CA, Silvester W, Butow PN, et al.: Advance care planning for adults with CKD: A systematic integrative review. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 761–770, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salat H, Javier A, Siew ED, Figueroa R, Lipworth L, Kabagambe E, et al.: Nephrology provider prognostic perceptions and care delivered to older adults with advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1762–1770, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudore RL, Fried TR: Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: Preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 153: 256–261, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, O’Leary JR, Towle V, Van Ness PH: Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med 171: 1854–1856, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javier AD, Figueroa R, Siew ED, Salat H, Morse J, Stewart TG, et al.: Reliability and utility of the surprise question in CKD stages 4 to 5. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 93–101, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearlman R, Starks H, Cain K, Cole W, Rosengren D, Patrick D: Your Life, Your Choices: Planning for Future Medical Decisions, Collingdale, PA, Diane Publishing, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson-Cohen C, Hall YN, Katz R, Rivara MB, de Boer IH, Kestenbaum BR, et al.: Self-rated health and adverse events in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2044–2051, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh B, Singh A, Ahmed A, Wilson GA, Pickering BW, Herasevich V, et al.: Derivation and validation of automated electronic search strategies to extract Charlson comorbidities from electronic medical records. Mayo Clin Proc 87: 817–824, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz S: Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc 31: 721–727, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawton MP, Brody EM: Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9: 179–186, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy EL, Murtagh FE, Carey I, Sheerin NS: Understanding symptoms in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis: Use of a short patient-completed assessment tool. Nephron Clin Pract 111: c74–c80, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group : A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurella Tamura M, Vittinghoff E, Hsu CY, Tam K, Seliger SL, Sozio S, et al.: CRIC Study Investigators : Loss of executive function after dialysis initiation in adults with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 91: 948–953, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montez-Rath ME, Zheng Y, Tamura MK, Grubbs V, Winkelmayer WC, Chang TI: Hospitalizations and nursing facility stays during the transition from CKD to ESRD on dialysis: An observational study. J Gen Intern Med 32: 1220–1227, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, Song MK, Unruh M: Provider knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding conservative management for patients with advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 812–820, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urquhart-Secord R, Craig JC, Hemmelgarn B, Tam-Tham H, Manns B, Howell M, et al.: Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: An international nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 444–454, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE: Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2815–2823, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong SP, Vig EK, Taylor JS, Burrows NR, Liu CF, Williams DE, et al.: Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: A qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of a national cohort of patients from the department of veterans affairs. JAMA Intern Med 176: 228–235, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladin K, Lin N, Hahn E, Zhang G, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE: Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: A qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 1394–1401, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA: System-level barriers and facilitators for foregoing or withdrawing dialysis: A qualitative study of nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 602–610, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, Sullivan AM, Cohen LM, Block SD, et al.: The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: National survey results of nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 813–820, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: A cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 233–239, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schell JO, Cohen RA, Green JA, Rubio D, Childers JW, Claxton R, et al.: Nephrotalk: Evaluation of a palliative care communication curriculum for nephrology fellows [published online ahead of print August 14, 2018]. J Pain Symptom Manage 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schell JO, Arnold RM: What are the ill effects of chronic dialysis? The benefits of a second conversation: How experience influences decision-making. Semin Dial 27: 21–22, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Auriemma CL, Nguyen CA, Bronheim R, Kent S, Nadiger S, Pardo D, et al.: Stability of end-of-life preferences: A systematic review of the evidence. JAMA Intern Med 174: 1085–1092, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.