Abstract

Background

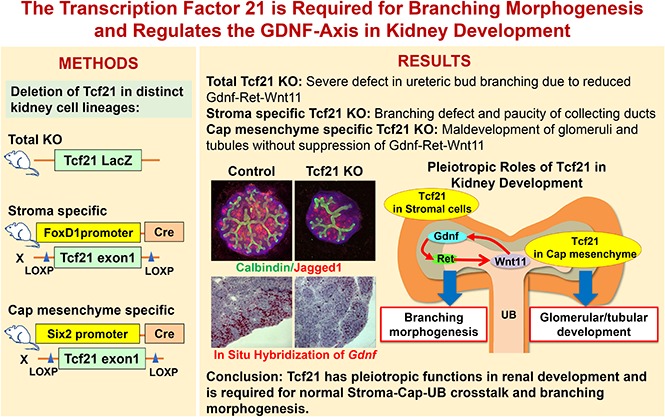

The mammalian kidney develops through reciprocal inductive signals between the metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric bud. Transcription factor 21 (Tcf21) is highly expressed in the metanephric mesenchyme, including Six2-expressing cap mesenchyme and Foxd1-expressing stromal mesenchyme. Tcf21 knockout mice die in the perinatal period from severe renal hypodysplasia. In humans, Tcf21 mRNA levels are reduced in renal tissue from human fetuses with renal dysplasia. The molecular mechanisms underlying these renal defects are not yet known.

Methods

Using a variety of techniques to assess kidney development and gene expression, we compared the phenotypes of wild-type mice, mice with germline deletion of the Tcf21 gene, mice with stromal mesenchyme–specific Tcf21 deletion, and mice with cap mesenchyme–specific Tcf21 deletion.

Results

Germline deletion of Tcf21 leads to impaired ureteric bud branching and is accompanied by downregulated expression of Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11, a key pathway required for branching morphogenesis. Selective removal of Tcf21 from the renal stroma is also associated with attenuation of the Gdnf signaling axis and leads to a defect in ureteric bud branching, a paucity of collecting ducts, and a defect in urine concentration capacity. In contrast, deletion of Tcf21 from the cap mesenchyme leads to abnormal glomerulogenesis and massive proteinuria, but no downregulation of Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 or obvious defect in branching.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that Tcf21 has distinct roles in the cap mesenchyme and stromal mesenchyme compartments during kidney development and suggest that Tcf21 regulates key molecular pathways required for branching morphogenesis.

Keywords: Ureteric bud branching, Transcription Factor 21, Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract, Renal stroma, Metanephric mesenchyme

Visual Abstract

Development of the mouse metanephros begins at approximately embryonic day (E) 10.5 with induction of the ureteric bud (UB) at the posterior end of the nephric duct (also known as the Wolffian duct) by signals from the adjacent metanephric mesenchyme (MM).1,2 The UB invades the MM, elongates, and branches to form the renal collecting system. As each branch forms, a subset of mesenchymal cells aggregate and condense around the UB tips to form the Six2-expressing cap mesenchyme (CM). This structure further differentiates into pretubular aggregates, comma- and S-shaped bodies, and subsequently into the Bowman’s capsule of the glomerulus, podocytes, and the nephron down to the distal tubule.3–5 The Six2-positive CM is surrounded by Foxd1-expressing stromal cells that are also derived from the MM and give rise to interstitial cells, mesangial cells, and pericytes.6 Disruption of any of these events results in congenital anomalies of the kidney and the lower urinary tract (CAKUT); these represent 20%–30% of all anomalies identified in the prenatal period in humans.7–10

Cell type–specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors are key regulators of organ morphogenesis.11–14 Transcription factor 21 (Tcf21) (Pod1/Capsulin/Epicardin) is a class 2 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that shows robust expression in mesenchymal cells of the urogenital, respiratory, digestive, and cardiovascular systems throughout embryogenesis and is involved in epithelial–mesenchymal interactions in the kidney, lung, and other organs.15–18 In disease, Tcf21 is reported to function as a tumor suppressor and loss of Tcf21 expression and/or methylation of its promoter have been identified in a variety of lung and urogenital tumors.19,20 In other studies, Tcf21 has been linked to coronary artery disease,21,22 podocyte differentiation, diabetic kidney disease,23 and changes in adipose phenotype.24

In the kidney, previous work has shown that Tcf21 null mutant mice are born with severely hypoplastic kidneys, and that although Tcf21 is exclusively expressed in the mesenchyme, in its absence, major defects in UB epithelial differentiation and branching are observed.15,25 Currently, it remains unclear what signaling pathways are controlled by Tcf21. In this study, we report that Tcf21 regulates branching morphogenesis by modifying the Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 axis and provide data to support its pleiotropic functional roles that affect UB-MM-stromal crosstalk. Using the Cre-LoxP system we show that Tcf21 has distinct roles in Foxd1-positive stromal cells and Six2-positive CM cells; where selective deletion of Tcf21 from the stromal cells results in branching defects, a paucity of collecting ducts, and urine concentrating defects. On the other hand, Tcf21 deletion in the CM leads to defects in glomerulogenesis and massive proteinuria.

Methods

Ethics Statement/Study Approval

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal studies. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the Center for Comparative Medicine of Northwestern University (Evanston, IL) or by the Chiba University Ethics Committee (Chiba, Japan).

Mice and Genotyping

Tcf21 lox/lox and Tcf21-LacZ mice were created as previously described.23,25 The Six2-eGFPCre and FoxD1-eGFPCre mice were kind gifts from Dr. Andy McMahon (University of Southern California), and are described elsewhere.5,26 Rosa26-mT/mG reporter mice (JAX stock no. 007676) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory.

Immunostaining

For immunohistochemistry and lectin stainings, kidneys were dissected and fixed by 10% formalin or 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Tissues were then embedded in paraffin and sliced into 5-μm-thick sections. Before immunostainings, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and ethanol and boiled in citrate buffer for antigen retrieval. For immunofluorescence, after fixing by 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, tissues were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight and embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T 4583 compound (Sakura Finetek Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at −80°C and sliced into 10-μm-thick sections.

These sections were blocked (0.3% Triton X-100, 3% albumin, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS) for 1 hour, incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. After washing several times by PBS, they were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Fluorescence-labeled Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) or Lotus tetragonolobus lectin (LTL) was mixed with secondary antibodies. For detailed methods and a full list of antibodies, see Supplemental Material and Supplemental Table 1.

Real-Time PCR

Whole kidneys were dissected and preserved at −80°C after freezing in liquid nitrogen. They were treated by the homogenizer and QIA shredder (79656; Qiagen) and total RNA was extracted by using Pure link RNA minikit (12183025; Life Technologies). Reverse transcription was performed using Super Script III Reverse transcription (18080044; Invitrogen) according to the manuals. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were analyzed as the ratio to GAPDH.

Explant Culture of Mouse Embryonic Kidneys

Embryos were dissected from pregnant mice on day 12.5 postcoitum. Kidneys from embryos were cultured on Nucleopore Track-Etched Membranes (Whatman) floated on culture medium. After 48 hours, kidneys were fixed in 4% PFA and stained for Calbindin and Jagged1. The number of branching and Jagged1-positive spots were counted in a double-blind manner.

mRNA In Situ Hybridization

mRNA in Situ hybridization was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections using the RNAscope 2.5 assay system (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) with RNAscope FFPE Reagent Kit, 2.5 HD-Reagent Kit-RED, 2.5 HD-Reagent Kit-BROWN. Recommended probes were used for this assay.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Comparison of two groups was done by two-tailed t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant. Error bars showed ±SEM.

Results

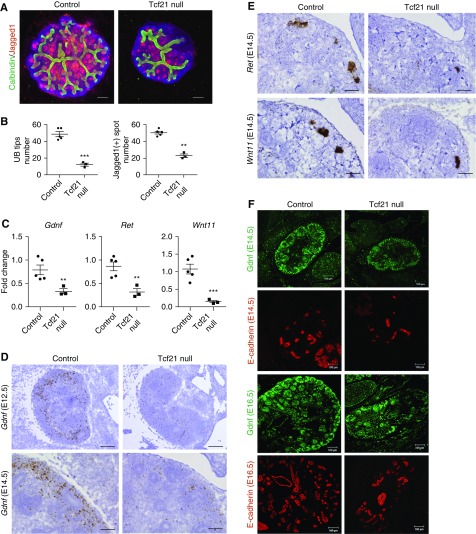

Tcf21 Regulates Branching Morphogenesis via Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 Signaling

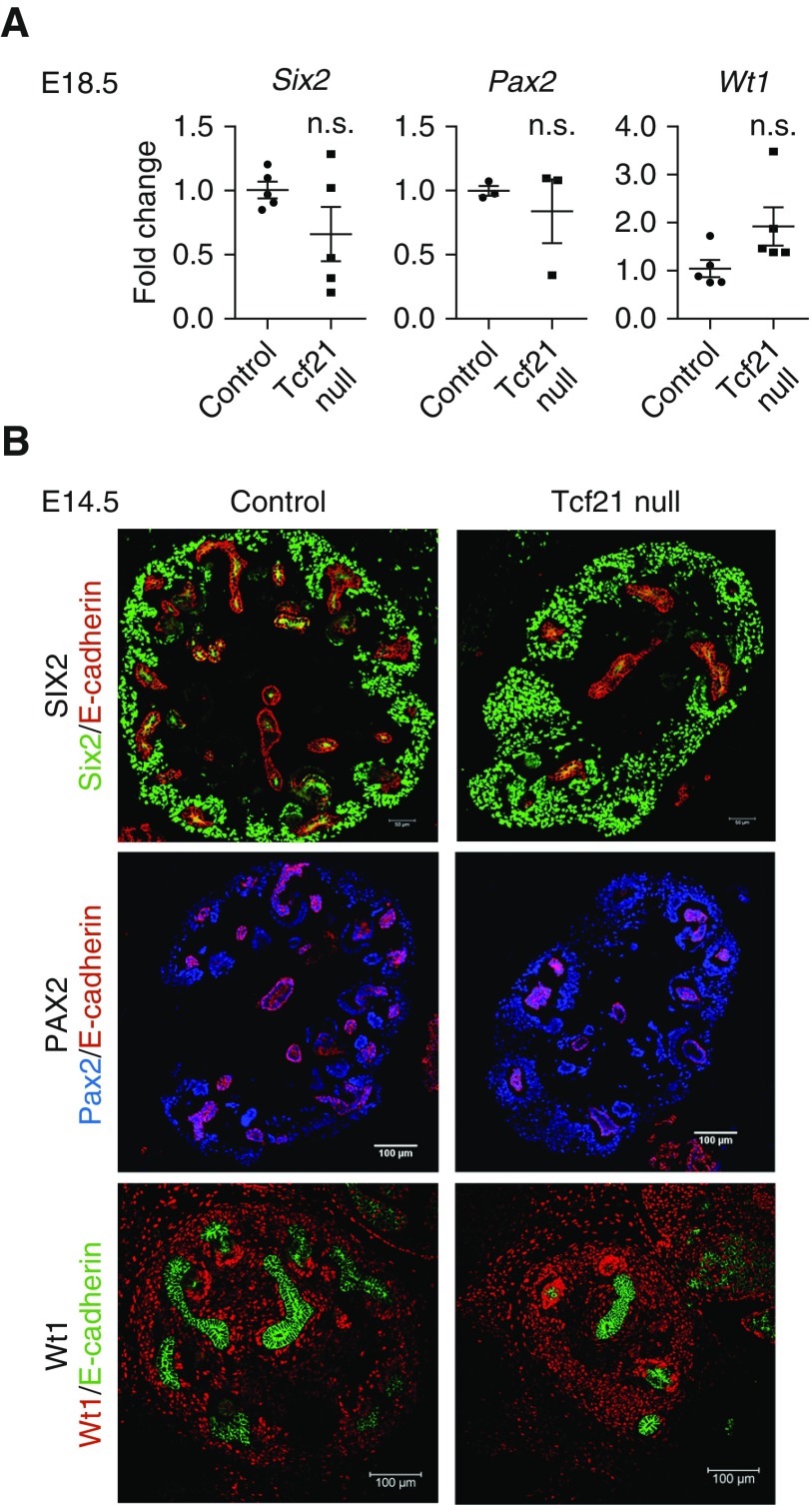

Germline deletion of Tcf21 leads to hypodysplastic kidneys reminiscent of CAKUT in humans (Supplemental Figure 1). At E12.5 +48 hours, Tcf21 null explant cultures show a very abnormal UB tree (Figure 1, A and B). To determine how Tcf21 regulates UB branching and collecting duct development, we first examined the expression of Gdnf, which is critical for branching morphogenesis. Gdnf transcript level was markedly downregulated to <40% in Tcf21 null kidneys at E14.5 compared with wild-type by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 1C). By in situ hybridization at E12.5 and E14.5 and by immunohistochemistry at E14.5 and E16.5, Tcf21 null kidneys also exhibit reduction of Gdnf (Figure 1, D and F). Next, we examined the expression of Ret, the cognate tyrosine kinase receptor for Gdnf, and that of Wnt11, a growth factor that is necessary to maintain Gdnf expression. Similar to Gdnf, both Ret and Wnt11 transcript levels were decreased in Tcf21 null kidneys at E14.5, consistent with paucity of UB branch tips (Figure 1, C and E). The quantitative RT-PCR results were normalized to Gapdh to account for size difference of the kidneys. These results suggest that Tcf21 is required for normal expression of Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 and therefore is critical for UB branching. On the other hand, the expression pattern of markers for CM (Six2, Pax2, and Wt1) was not decreased by quantitative RT-PCR and immunostaining in Tcf21 null kidneys (Figure 2, A and B). This suggests that the decrease of Gdnf in Tcf21 null kidneys is not the result of loss of nephron progenitor population, consistent with previous experiments.27 Further, the transcription factors that regulate Gdnf (Osr1, Eya1, Pax2, Six2, Hoxa11, Hoxd11, Wt1, Sall1, and Gata3) were not decreased in Tcf21 null kidneys (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 2). We next examined the potential role of Tcf21 in non-Gdnf–dependent pathways that regulate UB branching: fibroblast growth factor (Fgf), canonical Wnt, and retinoic acid signaling. At E14.5 and E18.5, none of the transcripts of Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1, subfamily a2 (Aldh1a2), Retinoic acid receptorα (Rara), Fgf7, Fgf10, Retinoic acid receptor β (Rarb), and Wnt4 were significantly downregulated (Supplemental Figure 3). Taken together, these results support a selective role for Tcf21 in regulating the Gdnf axis.

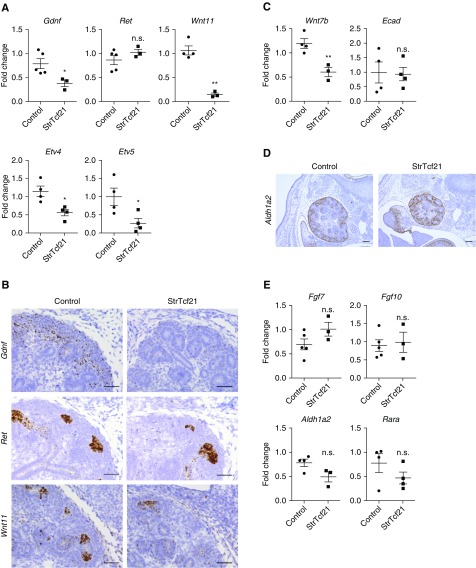

Figure 1.

UB branching is impaired and Gdnf, Ret, and Wnt11 are downregulated in Tcf21 null kidneys. (A and B) Reduced number of UB tips (green, calbindin) and renal vesicles (red, Jagged1) in Tcf21 null kidney explants. Kidneys were dissected at E12.5, incubated for 48 hours and subjected to immunostainings. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Downregulation of Gdnf, Ret, and Wnt11 mRNA expression in Tcf21 null kidneys at E14.5 by quantitative RT-PCR. (D) Low expression of Gdnf mRNA in the mesenchyme of Tcf21 null kidneys at E12.5 and E14.5 by in situ hybridization. Scale bar E12.5, 100 μm; E14.5, 50 μm. (E) Paucity of Ret and Wnt11 mRNA at the UB tips by in situ hybridization in Tcf21 null kidneys at E14.5. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Immunostaining of Gdnf and the pan-epithelial marker E-cadherin of Tcf21 null kidneys and controls at E14.5 and E16.5 showing low expression of Gdnf and abnormal UB branching. Scale bar, 100 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Figure 2.

Absence of Tcf21 does not affect quantitative expression of Six2, Pax2, and Wt1 in Tcf21 null kidneys at E14.5 and E18.5. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR on whole kidney at E18.5 showing no significant change in mRNA expression levels of Six2, Pax2, and Wt1 in Tcf21 null and control kidneys. (B) Immunostaining of Six2, Pax2, and Wt1 at E14.5 shows largely intact CM in Tcf21 null kidneys and controls. Scale bars, 200 or 100 μm as indicated.

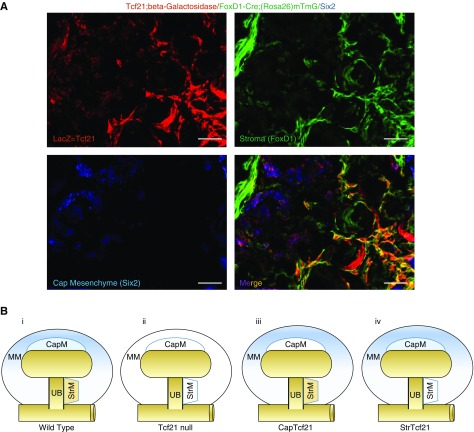

Tcf21 Has Distinct Roles in the Stromal and CM during Kidney Development

When MM cells begin to aggregate around the UB tips, the mesenchyme segregates to CM (expressing Cited1 and Six2) and to stromal mesenchyme (expressing high levels of Foxd1).28 We evaluated Tcf21 gene expression in each cell compartment using Tcf21 LacZ/Wild, Foxd1-eGFPCre; ROSA26-mTmG reporter mice. Immunostaining demonstrated that Tcf21 is distributed both in a subset of the Six2-positive CM and in the derivatives of Foxd1-positive stromal mesenchyme (Figure 3A). We hypothesized that the defect observed in UB branching and Mesenchymal to epithelial transformation in Tcf21 null kidneys represented convergence of signals from these distinct cell lineages that arise from the MM. To dissociate these effects, we generated two Cre/LoxP mouse models, StrTcf21 and CapTcf21, where Tcf21 is selectively deleted from the kidney stromal cells under FoxD1-eGFPCre driver, and from the CM under Six2-eGFPCre driver, respectively (Figure 3B, schematic illustration).

Figure 3.

Tcf21 is expressed in a subset of the CM and stromal mesenchyme. (A) Immunostaining of the kidney from Tcf21LacZ/+; FoxD1Cre; (ROSA26)mT/mG triple transgenic mice. Tcf21 LacZ expression by β-galactosidase staining (red) delineating normal expression of Tcf21 at E18.5. Derivatives of FoxD1-positive stromal mesenchyme was visualized by GFP using FoxD1-Cre;(ROSA26)mT/mG reporter mice (green). CM is represented by Six2 immunostaining (blue). Bar, 100 μm. (B) Schematic depiction of Tcf21 deletion in the mouse models utilized. White areas represent Tcf21-deleted cell lineages. (i) Wild-type; (ii) Tcf21 null kidney, Tcf21 is deleted in germline cells and hence from the entire MM and its derivatives; (iii) CapTcf21 kidney, Tcf21 is selectively deleted from the CM under Six2-eGFPCre driver; (iv) StrTcf21 kidney, Tcf21 is selectively deleted from the stromal mesenchyme under Foxd1-eGFPCre driver.

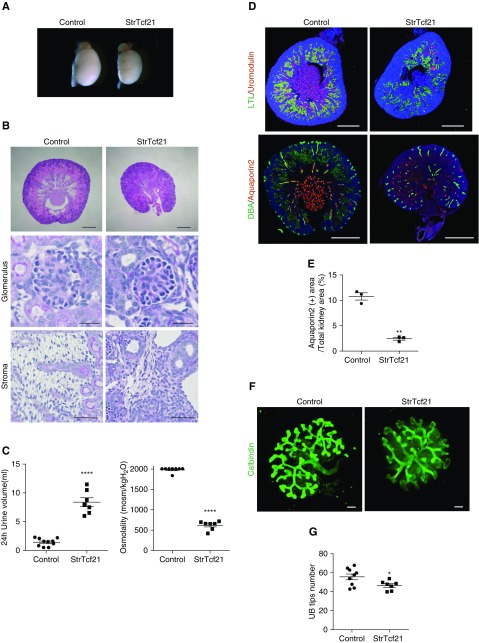

Deletion of Tcf21 in Stromal Progenitors Results in Abnormal UB Branching, Paucity of Collecting Ducts, and Disorganized Stroma

Several lines of evidence support a role for Tcf21 in the development of the interstitial stroma.27 To study Tcf21’s function in the stroma, Tcf21 lox/lox mice were bred to Foxd1-eGFPCre mice to generate a stromal-specific Tcf21 knockout mice (StrTcf21). In this model, Tcf21 mRNA expression in the stroma is markedly decreased starting at E14.5 onwards, although it is still expressed at E12.5 (Supplemental Figure 4). When the StrTcf21 mice were evaluated, they appeared healthy and survived for at least 10 weeks. On gross dissection, the StrTcf21 kidneys are reduced in size at birth and their histology reveals normal glomeruli but disorganized stroma (Figure 4, A and B, Supplemental Figure 5A). Notably, at 4 weeks of age the StrTcf21 animals showed increased urine volume and a severe defect in urine concentration capacity (Figure 4C). Corresponding with this finding is the severe reduction of collecting ducts in StrTcf21 kidneys that markedly outnumber the mild reduction in proximal tubules (Figure 4, D and E, Supplemental Figure 5, B and C). The paucity of collecting ducts is also evident by reduction of Aquaporin 2, Calbindin, DBA, Epithelial sodium channel, and Na-H-ATPase (Figure 4D, Supplemental Figure 5, C and D). To investigate whether the loss of collecting ducts stemmed from abnormal UB development, we examined the UB tree in kidney explants and noticed fewer UB tips in the StrTcf21 kidneys at E12.5 +48 hours, suggesting abnormal branching although we cannot rule out the possibility that artifacts from culturing for 48 hours may be different in mutants versus controls. Additionally, Wnt7b was decreased at E14.5 (Figures 4, F and G and 5C). Wnt7b is a UB stalk maker important to cortico-medullary organization and function.29 Further supportive of a primary branching defect is the finding of low expression of Gdnf and Wnt11 mRNA in the StrTcf21 kidney at E14.5 and P0 (Figure 5, A and B, Supplemental Figure 5, E and F). Of note, although Ret mRNA level is not reduced here, its downstream effectors Etv4 and Etv5 are significantly downregulated at E14.5 and E18.5 in StrTcf21 kidneys (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figure 5E). Taken together, these results suggest that Tcf21 expression in stromal cells is required for normal expression of the Gdnf axis, development of the collecting ducts, and normal organization of the stroma, whereas expression of members of the retinoic acid and Fgf pathways do not appear to be Tcf21-dependent (Figure 5, D and E). Although the stroma of StrTcf21 mice appears disorganized, mRNA levels of stromal markers were not depressed in whole-kidney lysate from mutants at E14.5 and P0 supporting normal stromal cell mass (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Absence of Tcf21 from the renal stroma does not affect glomerulogenesis but results in urine concentration defect, abnormal collecting ducts, and branching morphogenesis. (A and B) StrTcf21 kidneys are reduced in size, have normal glomeruli, and disorganized stroma ([B] Scale bars: top, 500 μm; middle, 25 μm; bottom, 50 μm). (C) StrTc21 mice develop polyuria and urine concentration defect at 4 weeks. (D and E) StrTc21 kidneys show severe decrease of inner medulla. Thick ascending limbs that express Uromodulin and collecting ducts that express Aquaporin 2 are largely reduced. Scale bar, 500 μm. (F and G) Abnormal UB branching in kidney explants of StrTc21 dissected at E12.5. Scale bar, 50 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.001.

Figure 5.

Absence of Tcf21 from the renal stroma leads to downregulation of the Gdnf axis at E14.5. (A and B) StrTcf21 kidneys have low mRNA of Gdnf and Wnt11 on quantitative real-time PCR and in situ hybridization. Ret transcript is not reduced but Etv4 and Etv5, downstream effectors of Ret, are downregulated in this model. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Reduced expression of the UB stalk marker Wnt7b, shown by quantitative real-time PCR. Expression of the pan-epithelial marker E-cadherin is not decreased. (D and E) mRNA expression of retinoic acid and Fgf signaling components that are critical for UB branching are not significantly changed by in situ hybridization and quantitative real-time PCR. Scale bar, 100 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Tcf21 in the CM Is Necessary for Proper Development of the Glomerulus and Tubules but Not for the Collecting Ducts

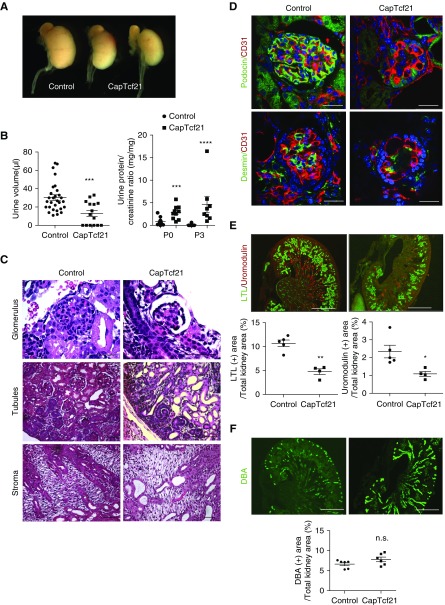

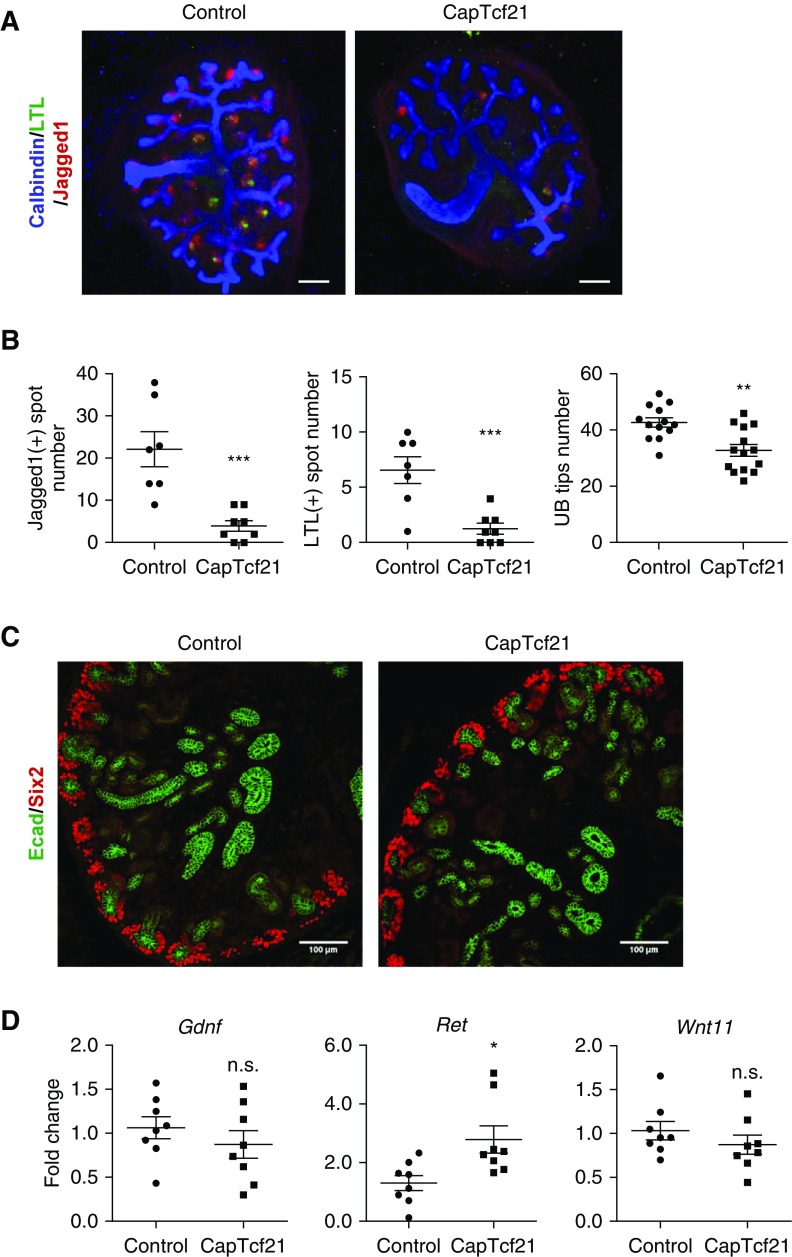

Deletion of Tcf21 from the CM (CapTcf21) results in smaller kidneys (Figure 6A, Supplemental Figure 7A) and decreased urine volume at P0 and proteinuria at 3 days of age (Figure 6B). Histologically at P0, the glomeruli of CapTcf21 show primitive and simplified structures. The tubules are cystic and atrophic, but the stromal structure does not show obvious changes (Figure 6C). The simplified glomeruli show decreased Podocin and Desmin, suggestive of a defect in mesangial ingrowth and/or mesangiolysis (Figure 6D), and ultrastructurally, the podocytes have effaced foot processes (Supplemental Figure 7B). The loss of tubular mass is also shown by reduced area of LTL-expressing proximal tubules and Uromodulin-positive thick ascending limb (Figure 6E). These results indicate that loss of Tcf21 in Six2-positive progenitors leads to defects in glomerulogenesis, podocyte differentiation, and tubular development. In contrast, absence of Tcf21 does not obviously affect the distribution of the collecting ducts as shown by similar DBA-positive area between CapTcf21 and controls (Figure 6F). In line with these findings are the results from kidney explants that show reduction in both renal vesicles (Jagged1) and proximal tubules (LTL), but only a mild decrease in UB tip number in CapTcf21 explants (Figure 7, A and B). The minimal effect of Tcf21 on branching in CapTcf21 kidneys is also noted by E-cadherin staining at E14.5 and similar mRNA levels of UB markers Wnt7b and Sox9 (Figure 7C, Supplemental Figure 7C). Importantly, loss of Tcf21 in the CM did not attenuate expression of Gdnf, Ret, or Wnt11 transcripts at E14.5 (Figure 7D). Taken together, these results suggest that although Tcf21 in the CM is required for the normal development of the glomeruli and tubules, it is not necessary for normal Gdnf axis and development of the collecting ducts.

Figure 6.

Absence of Tcf21 from the CM leads to abnormal glomeruli and tubules but does not affect the collecting ducts. (A) Absence of Tcf21 from the CM results in smaller kidneys at P0. (B) Urine volume is reduced and proteinuria is evident at P0 and P3 in CapTcf21 mice (volume measured by aspirating bladder content at the time of dissection). (C) Periodic acid–Schiff staining shows small and simplified glomeruli and cystic tubules in CapTcf21 mice. The histology of the renal stroma is not different from controls. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) CapTcf21 kidneys demonstrate glomerular injury by reduced Podocin and Desmin. Scale bars, 25 μm. (E) Reduced area of proximal tubules (LTL) and thick ascending limb (Uromodulin) in CapTcf21 kidneys. Scale bar, 500 μm. (F) The collecting ducts (DBA) are thick but the area is similar in CapTcf21 compared with controls. Scale bar, 500 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.001.

Figure 7.

Absence of Tcf21 from the CM leads to abnormal development of the glomeruli and tubules but does not affect the development of the collecting ducts or Gdnf axis expression. (A and B) Kidney explant assay at E12.5 for 48 hours of CapTcf21 and controls shows severely reduced Jagged1 (renal vesicle)- and LTL (proximal tubule)-positive spots, but counting of ureteric bud tips showed only mild decrease. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) E-cadherin (green) immunostaining of CapTcf21 and control kidneys at E14.5 showing similar patterns of UB development. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR results of Gdnf, Wnt11, or Ret transcripts at E14.5 showing no reduction in the Gdnf axis in the absence of Tcf21 from the CM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

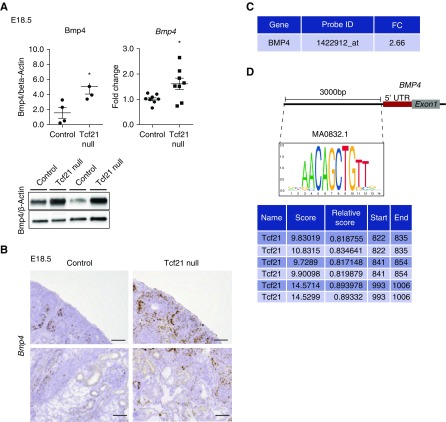

Bmp4 Is Upregulated in Tcf21 Null Kidneys

As described above, decreased Gdnf levels were noted only in Tcf21 null and StrTcf21 kidneys, whereas Gdnf had normal expression in the CapTcf21 model, suggesting that branching is dependent on Tcf21 expression in the stroma. Bmp4 is a member of the TGF-β superfamily that is expressed throughout embryonic development, initially in stromal cells enveloping the nephric duct.30–35 BMP4 is one of the key regulators of UB branching, inhibiting ectopic UB outgrowth by decreasing expression of Gdnf.34,36–38 Previous work showed that Tcf21-lacZ–expressing cells are present around the stalk of the UB and express Bmp4.27 Here, Bmp4 protein and mRNA levels were increased in Tcf21 null kidneys at E18.5 (Figure 8, A and B). Upregulation of Bmp4 was also seen in our previously conducted gene-expression microarray analysis on total RNA extract from glomeruli of Tcf21 lacZ/lacZ null mice at E18.5 (Mouse Affymetrix GeneChips 430–2.0)39 (Figure 8C). In silico analysis showed that the 3000 bp promoter and 5′ UTR regions of the Bmp4 gene contain the canonical binding sequences of Tcf2140 (Figure 8D). Thus, Bmp4 expression increase in Tcf21 null kidneys may suggest its involvement in Tcf21-mediated effects.

Figure 8.

Bmp4, a stromal factor and inhibitor of Gdnf, is upregulated in Tcf21 null mutants. (A and B) In Tcf21 null kidneys at E18.5, Bmp4 protein and mRNA are increased by Western blot, quantitative RT-PCR, and in situ hybridization, respectively. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Upregulation of Bmp4 by gene-expression microarray analysis on total RNA extract from glomeruli of Tcf21 null mice at E18.5. (D) Graphic depiction of Tcf21 binding site consensus sequences and their location relative to the Bmp4 gene promotor and 5′ UTR exon (JASPAR database). *P<0.05.

Discussion

In the mammalian kidney, interactions between the UB and the MM promote growth and differentiation to generate a functional organ of appropriate size, shape, and cellular diversity.41 Perturbations to these processes lead to CAKUT that, in many cases, stem from disruption of genes involved in renal organogenesis.42,43 The “budding theory” proposes that hypodysplastic kidneys in CAKUT are the result of defects in UB branching.44,45 UB epithelium branching is principally controlled by the Gdnf-Ret pathway and by the Wnt, Fgf, and retinoic acid signaling pathways, but many other genes are involved.2,46–48 Importantly, mutations in RET and GDNF, as well as in other genes that regulate branching of the UB, have been associated with CAKUT.10,42 Although a functional role of Tcf21 in human CAKUT has not yet been reported, Tcf21 has been shown to be downregulated in dysplastic fetal kidneys.49

Here, we report a spectrum of renal developmental phenotypes that resemble human CAKUT that result from loss of Tcf21 from the germline, or from specific MM compartments. Kidneys from conventional Tcf21 knockout mice show arrested Mesenchymal to epithelial transformation, with malformed and very small kidneys. We also identified a reduction in expression of the Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 signaling loop critically required for branching morphogenesis in null Tcf21 embryos.

The expression of Tcf21 in the developing kidney is complex.27 Although Tcf21 is not expressed in metanephrogenic blast cells found at the periphery of the metanephros before induction and condensation, it is expressed in both the Six2-expressing CM and in FoxD1-expressing stromal cells. Somewhat unexpectedly, the branching defects observed in conventional Tcf21 knockout mice were only observed in mice lacking Tcf21 from the stromal compartment, whereas glomerular defects were observed in CapTcf21 mutants. In addition, Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 downregulation was only observed in StrTcf21 and total knockout mice.

What can be learned from these distinct phenotypes? The most likely explanation is that Tcf21 has distinct functions in the stromal versus cap mesenchymal lineages. Interestingly, the phenotype of the Tcf21 null mice was much more severe than that observed in either StrTcf21 or CapTcf21 kidneys, suggesting that the Tcf21 null phenotype is not a simple sum of each compartmentalized phenotype. Although this may reflect timing or completeness of gene inactivation, other explanations are possible, including crosstalk between Tcf21-expressing cell types or existence of additional subset(s) of mesenchymal cell types not represented by Six2 or Foxd1 expression.

The role of the stromal cells as a key regulator of nephrogenesis and branching morphogenesis has previously been shown in Foxd1 null mice.50–52 Levinson et al.51 showed that Foxd1 null mice are born with hypodysplastic and fused midline kidneys, a similar but not identical renal phenotype observed in Tcf21 null mice. The importance of stromal Tcf21 for UB branching has been previously suggested in Tcf21LacZ/GFP chimeras, alluding to a noncell-autonomous role of Tcf21 in the stroma.27 We now have shown that removal of Tcf21 in Foxd1-positive cells leads to downregulation of Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11, providing a potential mechanism to explain the phenotypes of both Tcf21 and Foxd1 knockout mice. Whether Tcf21 expression in the stroma is required for normal stromal development is not completely clear. Here, we show that removal of Tcf21 from stromal progenitors results in disorganized interstitium that has normal expression of stromal cell markers, suggesting that Tcf21 is not required for the development of normal total stromal cell mass but that it may have a role in stromal cell alignment. Lastly, identifying direct gene targets for Tcf21 in the kidney is crucial for understanding its mechanistic action. In that regard, the observed increased levels of Bmp4, a stromal factor and a potent inhibitor of UB branching and Gdnf,33,34,53–56 is intriguing; however, further study is required to verify direct regulatory effect.

In summary, the results support a model whereby Tcf21 has distinct roles in cap versus stromal MM that are critical for normal nephrogenesis. In addition, stromal expression of Tcf21 is needed to allow normal UB branching morphogenesis via the Gdnf-Ret-Wnt11 autoregulatory loop (Supplemental Figure 8), underscoring the importance of stromal-cap-MM-UB crosstalk in kidney development.

Disclosures

S.E.Q. owns stock in and is a director of Mannin Research, and is on the external advisory board of Astra Zeneca.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mrs. Aki Watanabe and Naoko Koizumi for technical support, and Dr. Akira Suto and Dr. Hiroshi Nakajima for technical supports and fruitful discussion.

S.E.Q., G.F., Y.M., and S.I. designed the study; S.I., Y.M., G.F., M.Y., X.Z., Y.B., T.M., R.S., C.L., K.I., T.O., and Y.A. carried out experiments; G.F., S.I., Y.M., T.S., R.S., J.J., S.E.Q., M.T., and K.Y., analyzed the data; G.F., Y.M., and S.I., made the figures; G.F., Y.M., S.I., and S.E.Q. drafted and revised the paper; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Japan Society for Promotion of Science grants 17K09687 (to Y.M.), 17K19643 (to K.Y.), and 17J03714 (to S.I.), by the National Kidney Foundation of Illinois Young Investigator Award (to G.F.), and by National Institutes of Health grants HL124120, EY025799, T32 DK108738, and P30DK114857 (to S.E.Q.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017121278/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Costantini F, Kopan R: Patterning a complex organ: Branching morphogenesis and nephron segmentation in kidney development. Dev Cell 18: 698–712, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little MH, McMahon AP: Mammalian kidney development: Principles, progress, and projections. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a008300, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dressler GR: The cellular basis of kidney development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 509–529, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vainio S, Lin Y: Coordinating early kidney development: Lessons from gene targeting. Nat Rev Genet 3: 533–543, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, Carroll TJ, Self M, Oliver G, et al.: Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell 3: 169–181, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi A, Mugford JW, Krautzberger AM, Naiman N, Liao J, McMahon AP: Identification of a multipotent self-renewing stromal progenitor population during mammalian kidney organogenesis. Stem Cell Reports 3: 650–662, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope JC 4th, Brock JW 3rd, Adams MC, Stephens FD, Ichikawa I: How they begin and how they end: Classic and new theories for the development and deterioration of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, CAKUT. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2018–2028, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schedl A: Renal abnormalities and their developmental origin. Nat Rev Genet 8: 791–802, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Ven AT, Vivante A, Hildebrandt F: Novel insights into the pathogenesis of monogenic congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 36–50, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanna-Cherchi S, Westland R, Ghiggeri GM, Gharavi AG: Genetic basis of human congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Clin Invest 128: 4–15, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weintraub H, Davis R, Tapscott S, Thayer M, Krause M, Benezra R, et al.: The myoD gene family: Nodal point during specification of the muscle cell lineage. Science 251: 761–766, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JE, Hollenberg SM, Snider L, Turner DL, Lipnick N, Weintraub H: Conversion of Xenopus ectoderm into neurons by NeuroD, a basic helix-loop-helix protein. Science 268: 836–844, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porcher C, Swat W, Rockwell K, Fujiwara Y, Alt FW, Orkin SH: The T cell leukemia oncoprotein SCL/tal-1 is essential for development of all hematopoietic lineages. Cell 86: 47–57, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava D, Thomas T, Lin Q, Kirby ML, Brown D, Olson EN: Regulation of cardiac mesodermal and neural crest development by the bHLH transcription factor, dHAND. Nat Genet 16: 154–160, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quaggin SE, Vanden Heuvel GB, Igarashi P: Pod-1, a mesoderm-specific basic-helix-loop-helix protein expressed in mesenchymal and glomerular epithelial cells in the developing kidney. Mech Dev 71: 37–48, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidai H, Bardales R, Goodwin R, Quertermous T, Quertermous EE: Cloning of capsulin, a basic helix-loop-helix factor expressed in progenitor cells of the pericardium and the coronary arteries. Mech Dev 73: 33–43, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu J, Richardson JA, Olson EN: Capsulin: A novel bHLH transcription factor expressed in epicardial progenitors and mesenchyme of visceral organs. Mech Dev 73: 23–32, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robb L, Mifsud L, Hartley L, Biben C, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, et al.: Epicardin: A novel basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene expressed in epicardium, branchial arch myoblasts, and mesenchyme of developing lung, gut, kidney, and gonads. Dev Dyn 213: 105–113, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gooskens SL, Klasson TD, Gremmels H, Logister I, Pieters R, Perlman EJ, et al.: TCF21 hypermethylation regulates renal tumor cell clonogenic proliferation and migration. Mol Oncol 12: 166–179, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards KL, Zhang B, Sun M, Dong W, Churchill J, Bachinski LL, et al.: Methylation of the candidate biomarker TCF21 is very frequent across a spectrum of early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancers. Cancer 117: 606–617, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JB, Pjanic M, Nguyen T, Miller CL, Iyer D, Liu B, et al.: TCF21 and the environmental sensor aryl-hydrocarbon receptor cooperate to activate a pro-inflammatory gene expression program in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. PLoS Genet 13: e1006750, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu X, Wang L, Chen S, He L, Yang X, Shi Y, et al.: Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome-Wide Replication And Meta-Analysis (CARDIoGRAM) Consortium : Genome-wide association study in Han Chinese identifies four new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 44: 890–894, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maezawa Y, Onay T, Scott RP, Keir LS, Dimke H, Li C, et al.: Loss of the podocyte-expressed transcription factor Tcf21/Pod1 results in podocyte differentiation defects and FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2459–2470, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Jong JM, Larsson O, Cannon B, Nedergaard J: A stringent validation of mouse adipose tissue identity markers. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E1085–E1105, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quaggin SE, Schwartz L, Cui S, Igarashi P, Deimling J, Post M, et al.: The basic-helix-loop-helix protein pod1 is critically important for kidney and lung organogenesis. Development 126: 5771–5783, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, et al.: Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol 176: 85–97, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui S, Schwartz L, Quaggin SE: Pod1 is required in stromal cells for glomerulogenesis. Dev Dyn 226: 512–522, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little MH: Kidney Development, Disease, Repair, and Regeneration, Amsterdam, Boston, Elsevier/AP, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J, Carroll TJ, Rajagopal J, Kobayashi A, Ren Q, McMahon AP: A Wnt7b-dependent pathway regulates the orientation of epithelial cell division and establishes the cortico-medullary axis of the mammalian kidney. Development 136: 161–171, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Bubnoff A, Cho KW: Intracellular BMP signaling regulation in vertebrates: Pathway or network? Dev Biol 239: 1–14, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogan BL: Bone morphogenetic proteins in development. Curr Opin Genet Dev 6: 432–438, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang RN, Green J, Wang Z, Deng Y, Qiao M, Peabody M, et al.: Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis 1: 87–105, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudley AT, Robertson EJ: Overlapping expression domains of bone morphogenetic protein family members potentially account for limited tissue defects in BMP7 deficient embryos. Dev Dyn 208: 349–362, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyazaki Y, Oshima K, Fogo A, Hogan BL, Ichikawa I: Bone morphogenetic protein 4 regulates the budding site and elongation of the mouse ureter. J Clin Invest 105: 863–873, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson AJ: Mouse Kidney Development, Cambridge, MA, StemBook, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B, Chen Q, Tian D, Wu L, Dong H, Wang J, et al.: BMP4 reverses multidrug resistance through modulation of BCL-2 and GDNF in glioblastoma. Brain Res 1507: 115–124, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michos O, Gonçalves A, Lopez-Rios J, Tiecke E, Naillat F, Beier K, et al.: Reduction of BMP4 activity by gremlin 1 enables ureteric bud outgrowth and GDNF/WNT11 feedback signalling during kidney branching morphogenesis. Development 134: 2397–2405, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majumdar A, Vainio S, Kispert A, McMahon J, McMahon AP: Wnt11 and Ret/Gdnf pathways cooperate in regulating ureteric branching during metanephric kidney development. Development 130: 3175–3185, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui S, Li C, Ema M, Weinstein J, Quaggin SE: Rapid isolation of glomeruli coupled with gene expression profiling identifies downstream targets in Pod1 knockout mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3247–3255, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sazonova O, Zhao Y, Nürnberg S, Miller C, Pjanic M, Castano VG, et al.: Characterization of TCF21 downstream target regions identifies a transcriptional network linking multiple independent coronary artery disease loci. PLoS Genet 11: e1005202, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutledge EA, Benazet JD, McMahon AP: Cellular heterogeneity in the ureteric progenitor niche and distinct profiles of branching morphogenesis in organ development. Development 144: 3177–3188, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicolaou N, Renkema KY, Bongers EM, Giles RH, Knoers NV: Genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors involved in CAKUT. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 720–731, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vivante A, Hildebrandt F: Exploring the genetic basis of early-onset chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 133–146, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piscione TD, Rosenblum ND: The molecular control of renal branching morphogenesis: Current knowledge and emerging insights. Differentiation 70: 227–246, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichikawa I, Kuwayama F, Pope JC 4th, Stephens FD, Miyazaki Y: Paradigm shift from classic anatomic theories to contemporary cell biological views of CAKUT. Kidney Int 61: 889–898, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michos O, Cebrian C, Hyink D, Grieshammer U, Williams L, D’Agati V, et al.: Kidney development in the absence of Gdnf and Spry1 requires Fgf10. PLoS Genet 6: e1000809, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohuchi H, Hori Y, Yamasaki M, Harada H, Sekine K, Kato S, et al.: FGF10 acts as a major ligand for FGF receptor 2 IIIb in mouse multi-organ development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 277: 643–649, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosselot C, Spraggon L, Chia I, Batourina E, Riccio P, Lu B, et al.: Non-cell-autonomous retinoid signaling is crucial for renal development. Development 137: 283–292, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jain S, Suarez AA, McGuire J, Liapis H: Expression profiles of congenital renal dysplasia reveal new insights into renal development and disease. Pediatr Nephrol 22: 962–974, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hatini V, Huh SO, Herzlinger D, Soares VC, Lai E: Essential role of stromal mesenchyme in kidney morphogenesis revealed by targeted disruption of Winged Helix transcription factor BF-2. Genes Dev 10: 1467–1478, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levinson RS, Batourina E, Choi C, Vorontchikhina M, Kitajewski J, Mendelsohn CL: Foxd1-dependent signals control cellularity in the renal capsule, a structure required for normal renal development. Development 132: 529–539, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bard J: A new role for the stromal cells in kidney development. BioEssays 18: 705–707, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basson MA, Akbulut S, Watson-Johnson J, Simon R, Carroll TJ, Shakya R, et al.: Sprouty1 is a critical regulator of GDNF/RET-mediated kidney induction. Dev Cell 8: 229–239, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grieshammer U, Le Ma, Plump AS, Wang F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Martin GR: SLIT2-mediated ROBO2 signaling restricts kidney induction to a single site. Dev Cell 6: 709–717, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shakya R, Watanabe T, Costantini F: The role of GDNF/Ret signaling in ureteric bud cell fate and branching morphogenesis. Dev Cell 8: 65–74, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Short KM, Smyth IM: The contribution of branching morphogenesis to kidney development and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 754–767, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.