Abstract

Introduction:

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is widespread with 20% prevalence worldwide and a significant economic burden due to health care cost and constraints on daily activities of patients. Despite extensive investigation, the underlying causes of dyspepsia in a majority of patients remain unknown. Common complaints include abdominal discomfort, pain, burning, nausea, early satiety, and bloating. Motor dysfunction of the gut was long considered a major cause, but recent investigations suggest immune-based pathophysiological and molecular events in the duodenum are more probable contributing factors.

Areas Covered:

Inflammatory mediators and immune cells including duodenal eosinophils, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and T-cells have been implicated in the underlying cause of disease process, as have genetic factors. In this article, we critically reviewed findings, identified gaps in knowledge and suggested future directions for further investigation to identify targets and develop better therapeutic approaches.

Expert Commentary:

Impaired gastric accommodation, slow gastric emptying, and increased visceral sensitivity have long been thought of as main causal factors of FD. However, more recent identification of eosinophilic degranulation and recruitment of T cells that induce mild duodenal inflammation are giving rise to new insights into immune-mediated pathophysiology. These insights offer promising avenues to explore for immune-mediated therapy in the future.

Keywords: Functional dyspepsia, dyspepsia, endoscopy, duodenal inflammation, eosinophil degranulation, H. pylori

1. Introduction

The word dyspepsia is derived from the Greek words ‘dys’ (bad or faulty) and ‘pepsis’ (digestion). Patients present with clinical symptoms of epigastric pain, burning, early satiety, and post-prandial fullness, among other complaints. Dyspepsia is of two basic etiological types: (i) Organic, systemic or metabolic cause, or (ii) Functional Dyspepsia (FD). Organic causes include peptic ulcer disease, medication effects, endocrine disorders, hepatocellular carcinoma, gallstones, parasitic infestation, and pancreatico-biliary disorder. In these conditions, diagnosis is via an array of investigative tests where structural and biochemical abnormalities can explain the symptoms and accordingly direct the treatment [1]. Functional dyspepsia are those syndromes in which a complete set of investigations in patients fail to reveal any causative factor.

Current diagnostic criteria for FD are the Rome IV criteria. These were developed in 2016 by the Rome Foundation based on clinical reports from investigators and clinicians around the world, and are elaborations from the earlier Rome III criteria of 2006 [2]. The Rome IV criteria provided more specific definitions and diagnostic criteria based on the presence of symptom onset at-least 6 months prior to diagnosis and with one or more present for the last 3 months, These include: (a) bothersome postprandial fullness 3 or more days per week, (b) bothersome early satiety 3 or more days per week, (c) bothersome epigastric pain 1 or more days per week, (d) bothersome epigastric burning 1 or more days per week, and (e) no evidence of structural disease (including upper endoscopy) [3]. Functional dyspepsia is sub-classified into postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) based on the predominant symptoms.

Global prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia is estimated to be 21%, although it varies with geographical location, diagnostic criteria, and symptom duration. The highest prevalence of 57% is from a Japanese study, whereas as the lowest incidence of 1.8% is in a Canadian and Chinese report [4]. Female gender, smoking, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and positivity to Helicobacter pylori are the major risk factors of FD. A variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms have been proposed for FD such as altered gut motility like slow gastric emptying and impaired gastric accommodation [5]. Duodenal hypersensitivity to acid and abnormal response to lipids, as well as psychosocial conditions including depression or anxiety have also been associated with FD [6]. GERD (gastro-esophageal reflux disease) and gastroparesis can be confused with FD due to the overlap of symptoms. Research trends reflect a shift from gastric to duodenal bases for pathology.

This review article focuses on recent advances in molecular and immunological basis of FD as a residual diagnosis based on symptoms for which all other causes of dyspepsia have been ruled out. Treatment of FD is primarily aimed at symptom management. If H. pylori is suspected, treatment is to eradicate the bacterial infection. Few patients respond to proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists or prokinetics. Anti-depressants and anxiolytics are used as second line of therapy [7]. Improvement of symptoms is seen in only a small proportion of patient populations [8]. The quality of life of patients with FD is reduced on par with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [9].

New research posits immune dysregulation as the molecular basis for the pathogenesis of FD. Thus, normal immune mechanisms along with the role of innate and acquired immunity in the pathophysiology of FD are critically reviewed in this section. Role of genetics and environmental factors (including infections and gut microbiome) are the other pathophysiological aspects of FD which are reviewed in this section.

2. Innate and Acquired Immunopathology and Molecular Mechanisms

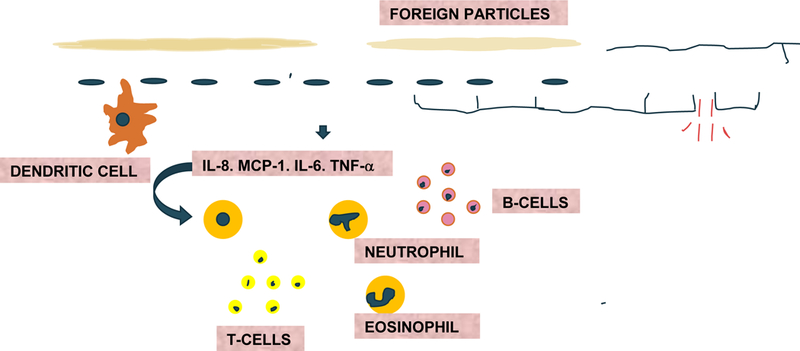

Consideration of basic forms of complex normal immunology of the gut is a useful prelude to further examination of immune dysregulation theories germane to FD. Immunity in humans can be broadly classified into innate and acquired (adaptive) immunity. The components of innate immunity include physical barriers, chemical barriers, natural killer cells, plasma proteins, dendritic cells, and others. Acquired immunity can further be classified into humoral immunity (mediated by B-lymphocytes and plasma cells which produce antibodies) and cell-mediated immunity (mediated by T cells such as T helper cells and cytotoxic cells). Mucosa of the epithelium host major immunological responses. Gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and draining lymph nodes foster adaptive immune responses. Intestinal epithelium contains many T cells, whereas lamina propria contains B cells, T cells, macrophages, eosinophils, mast cells, etc. Any alteration in the mucosal normality –whether due to bacteria, food antigens, allergens, and other factors – can trigger release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-8, MCP1, TNF-α, RANTES, IL-6. These stimulate neutrophils, B-cells, T cells, eosinophils, and macrophages that further mediate the inflammatory process (Figure 1). Dendritic cells help present antigens during this process. Findings from several pertinent studies indicate robust immune mechanisms underneath pathophysiology in FD associated with close intricate nature of both types of immune responses which makes it difficult to accurately delineate between innate and acquired pathophysiological basis of the disease.

Figure 1: Gut immune mediated activation to a foreign particle.

IL-8 (interleukin −8), MCP1(monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), TNF-alpha (tumor necrosis factor alpha), RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), IL-6 (interleukin −6) are first released then, in turn, neutrophils, B-cells, T cells, eosinophils, macrophages. Dendritic cells also present antigens which further activate inflammation.

3. Enteric Glial Pathology: Neuro-Immune Mechanism

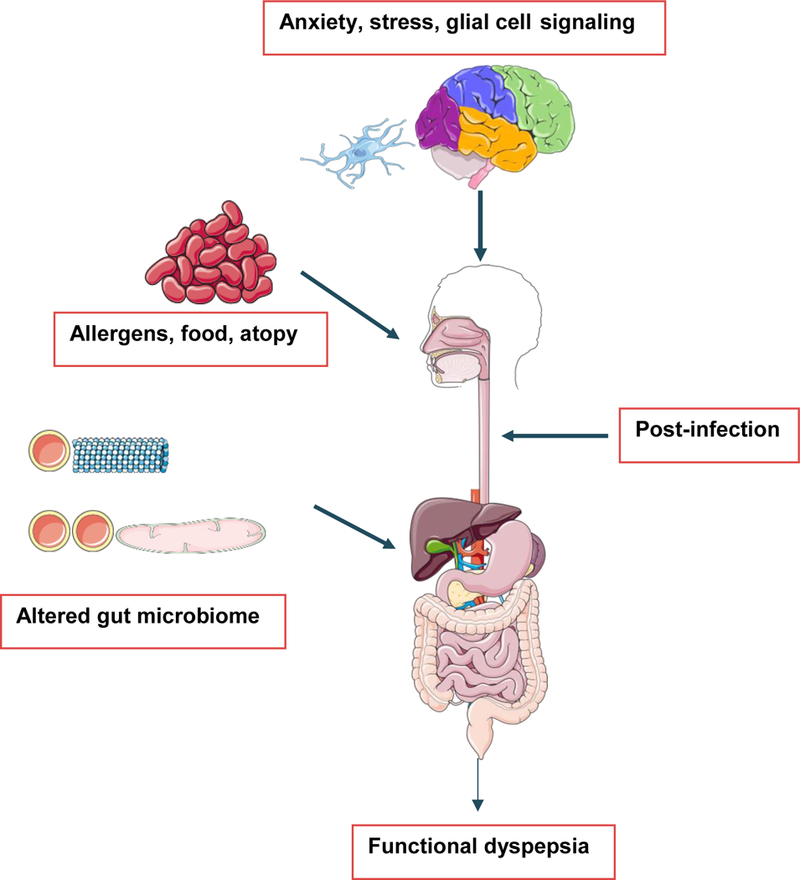

Enteric glial cells (EGC) connect the immune system with the nervous system via the capacity to secrete, upon alteration, inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, neural growth factor (NGF), and nitrous oxide. EGC not only maintain the mucosal epithelial barrier serving as a component of innate immune system, they also function as antigen presenting cells. Further, they control aspects of intestinal smooth muscle function [10, 11]. In a study conducted by Tominaga et al. [12] wherein Wistar rats were subjected to stress, they noted EGC exhibited structural changes. Stress is known to stimulate the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis to release various stress related mediators such as corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF), glucocorticoids, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), serotonin, glutamate, and gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), which can alter the glial structure [12]. Glial cells are known to release IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), all of which mediate calcium signaling and influences the enteric nervous system. CRF is known to reduce CD4 count and expression of duodenal mucosal tight junction proteins of rats subjected to acute stress [13]. A study conducted by Cirillo et al. showed the first direct evidence of neuronal impairment and gliosis in 18 FD patients, and also documented infiltration of submucosal layer by mast cells and eosinophils [14]. In another study conducted by Tanaka et al. [15] on patients with FD, GDNF expression was increased and further correlated with symptoms. These investigators postulated that in response to mild duodenal inflammation, EGC, eosinophils and epithelial cells release GDNF as a modulator of inflammation and are thereby protective of EGC [15]. This supports theoretic connections and, indeed, close intertwining between the gastro-intestinal immune and neuronal systems [16] (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Immunologic basis of functional dyspepsia. Multiple pathophysiological processes are known to cause Functional dyspepsia which act in several different ways as shown in the figure. Anxiety and stress can alter normal gut physiology by secreting mediators like glutamate, serotonin, corticosteroids, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), and GABA, which can alter glial cell structure. Glial cells release IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and glial cell line derived neurotropic factor (GDNF) which can influence the enteric nervous system. Post-infection in the duodenum retained mild inflammation can also cause functional dyspepsia. Allergens, atopy and altered gut microbiome have also been studied to be associated with functional dyspepsia. (Original Image created from smart.servier.com).

4. Relationship between Eosinophils and FD

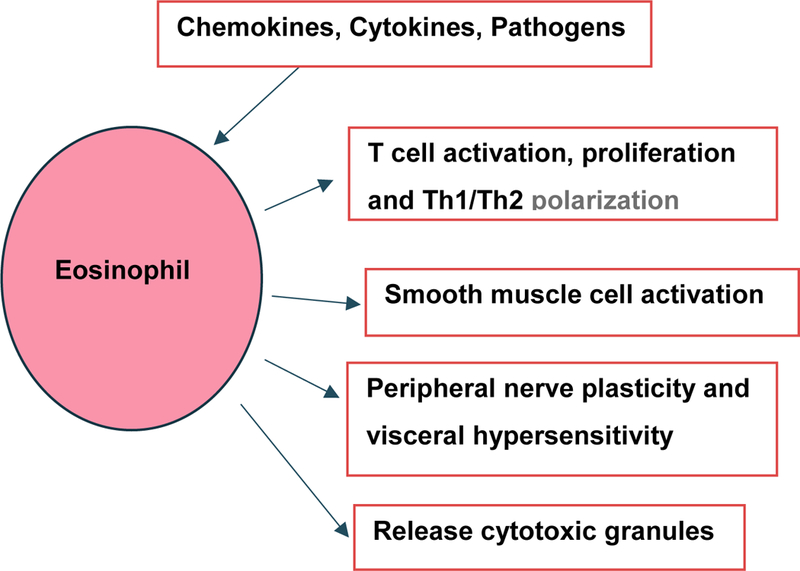

Eosinophils and mast cells are hypothesized to link innate and adaptive immunity to maintain homeostasis of intestinal epithelium [17]. This hypothesis suggests eosinophils are linked to other gastrointestinal diseases, e.g., eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic enteritis, parasitic infestations, malignancy, eosinophilic colitis, etc. [18]. Eosinophils can be triggered by parasitic infestation, allergy, and mild inflammation, and other conditions. Their granules are composed of major basic protein (MBP), eosinophil derived neurotoxin (EDN), eosinophil peroxidase (EPO), and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP). When triggered, eosinophils can generate interleukins, inflammatory cytokines, eotaxin, leukotrienes C4, and transforming growth factors, which can activate to promote Th1-Th2 polarization. These can affect nerve cell signaling to then mediate a variety of immune and neurological responses, as well as increased vascular permeability and altered smooth muscle contraction [19]. MBP is also known to be associated with regulation of peripheral nerve plasticity and thus can cause visceral hypersensitivity [20] (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Functional capacities of eosinophil. Eosinophils are activated by chemokines, pathogens and cytokines. After activation, it releases cytotoxic granules and interleukins such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 which help in activation and proliferation of T-cells. They also help in differentiation of T helper cells. It alters vascular permeability and causes smooth muscle contraction. It releases major basic protein (MBP) which increases peripheral nerve plasticity and visceral hypersensitivity. Th1, T-helper 1 CD4+ lymphocytes; Th2, T-helper 2 CD4+ lymphocytes

Several studies have shown increase in eosinophilic and mast cell count in FD patients, but the information has been partly inconclusive because of several other studies reporting otherwise. A recent well-designed systemic review and meta-analysis conducted on prospective case-controlled and observational studies to evaluate the role of micro-inflammation in cases of FD, post-infectious FD (PIFD) and EPS showed that majority of the patients with these diseases demonstrated duodenal eosinophilia (with increasing evidence of eosinophilia in 2nd part of duodenum) and increase in duodenal mast cells. In addition to duodenal infiltration, it was also noted that eosinophils and mast cells were increased in gastric mucosa. The authors reported heterogeneity and non-standardized study designs among the studies analyzed as the limitations of this meta-analysis [21]. A case control study conducted by Talley et al. in a Swedish population showed significant association of eosinophilic infiltrate and non-ulcer dyspepsia in patients after all other conditions that can cause eosinophilia like allergy, parasitic infestation, etc., were excluded. Eosinophilic degranulation was observed by immunostaining MBP in duodenal biopsy specimens, even though increased eosinophil count was also seen in patients with prior H. pylori infection with non-ulcer dyspepsia [22]. In another study conducted by Lijun et al. in Chinese population in a hospital, duodenum was observed to have more eosinophilic degranulation compared to controls, but failed to demonstrate mast cell degranulation [23]. In another cohort study conducted by Walker et al., increased eosinophil count per mm2 was seen in duodenal biopsy in patients with symptoms of early satiety and post prandial fullness [24]. A study conducted by Futagami et al. in 136 patients diagnosed with FD using 20 controls noted increased eosinophils in post infectious FD [25]. A range of studies done in other aspects of FD also note increased eosinophils [26]. The findings from these studies support the role of eosinophils and potentially of mast cells as well in the pathophysiology of FD. However, additional studies are warranted to establish the causal role of eosinophils and accordingly develop better therapeutic strategies.

5. Relationship Between Allergy and FD

Allergic conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, or food allergies are known to stimulate immune mechanisms. Duodenal biopsy specimens from asthma and allergic rhinitis patients have increased eosinophils along with IL4+, IL5+ cells, helper T cells, and macrophages. This may be a systemic response to allergens, though no local inflammation was evident [27, 28] and patients noted no symptoms of dyspepsia. A retrospective case control study of 7,235 adult patients (865 asthmatics, 647 allergic rhinitis, and rest controls), found dyspepsia more common in an allergic population. Studies of IgG and IgE antibodies to specific foods in patients with FD and inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS) found no significant relation between symptoms and other details, though titers for some foods were increased in FD [29]. Further research in this area is necessary to clarify our understanding.

6. Environmental factors in FD (Infections and Microbiota)

6.1. Post-Infectious Immune Mechanism of FD

Although FD is excluded in the presence of current infection, it may begin as a sequela of gastric infection or from an episode of gastroenteritis with no evidence of ongoing infection. Futagami et al. [25] studied duodena of patients presenting with post-infectious FD (PIFD) and noted both eosinophilia and CCR2 positive macrophage infiltration. They proposed that prostaglandins released from macrophages may increase nerve sensitivity and induce symptoms such as epigastric burning [25]. Kindt et al. studied 12 patients with PIFD and unspecified FD. They noted histological changes in the duodenum of patients with PIFD, i.e., persistent focal CD8+ T cell aggregates, decreased CD4+ cells, and increased macrophage counts. The immune response was incomplete as CD4+ cells were decreased, even though an inflammatory response was evident with increased CD8+ cell count [30]. In these patients with PIFD, activated mast cells and enterochromaffin cells had greater density in gastric mucosa. Symptoms of FD could be explained by the release of histamine, 5-hydroxy tryptamine (5HT), and tryptase from the activated mast cells and enterochromaffin cells [31]. The mast cell tryptase is also known to activate eosinophils [32]. Though several studies link mast cells to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [33, 34] [35], the relationship of mast cells with FD is not fully clarified. A Nigerian study with presumed endemic gastrointestinal infections positively correlated duration of symptoms to the inflammatory score [36]. A limitation of the study is the failure to exclude active H. pylori infection. An investigation based on the hypothesis that inflammation can affect myenteric nitrergic neurons of the gut found a subset of patients with PIFD showing no response to administration of sumatriptan, whereas stomach tissue of patients with unspecified FD relaxed upon administration of sumatriptan [37]. A one year follow up study of a population that suffered an outbreak of acute salmonella gastroenteritis noted symptoms of dyspepsia including prolonged abdominal pain and vomiting. The relative risk of developing dyspepsia and inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS) in this population with gastroenteritis was 5.2 and 7.8, respectively [38].

6.2. Post H. pylori Immune Mechanism of FD, now H. pylori Dyspepsia

Rome IV classification completely changed this category, separating it from FD within a separate entity, H. pylori dyspepsia. This is warranted by considerable advancements in this area of research. Patients who continue to be symptomatic after treatment for H. pylori eradication were included under FD. Remarkably, almost half of the world population is known to be infected with H. pylori but only few are symptomatic. It is known to be a major causative factor in peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Futagami et al. found no relation between duodenal macrophage accumulation and prior H. pylori infection in FD treated patients who still had H. pylori infection, but who presented with no evidence of any inflammation [25]. Various other studies show correlation. A systematic review of 17 randomized controlled trials concluded small but important effects of treating H. pylori to prevent dyspepsia [39]. Another meta-analysis of 14 randomized control studies shows strong improvement in dyspeptic symptoms when patients are treated for H. pylori infection [40]. A Nigerian study noted gastric metaplasia in few patients with FD with assumed links to H. pylori infection that increases gastrin and gastric acid that induce metaplasia [36, 41]. A study was done with 126 patients over 60 years of age diagnosed with H. pylori FD [42]. Patients were treated with dual and triple therapy to eradicate H. pylori. Two months after treatment, patients showed symptomatic improvement [42]. Other studies demonstrate a relationship between H. pylori and FD [43–45]. For example, patients with H. pylori infection showing microscopic duodenitis showed aggravated symptoms of FD [46]. Microscopic duodenitis leads to the development of ulcerations, and thus may herald ulcer-like dyspepsia. Collectively, studies documenting success of eradication therapy in a subset of H pylori-positive patients with FD were the basis of the Kyoto global consensus report that recommends H. pylori treatment of FD patients with an organic cause [47].

6.3. Role of Intestinal Microbiota in FD

Trillions of gut microbiomes are known to inhabit the human body. Vast ranges are present in every individual depending on a wide variety of demographic elements, e.g., sex, race, age, geography, antibiotic exposure, and diet starting with neonatal breast feeding. Gut microbiota is known to regulate the intestinal epithelial barrier and mucosal T cells [48, 49] and when altered, it is known to induce visceral hypersensitivity [50]. A study in mice found the influence of gut microbiota in the development of B cells and T cells in both peyers patches and mesenteric lymph nodes, while also increasing immuno-protective IL-10 and IFN-γ [51]. Alteration of the microbiome is known to elicit functional gastrointestinal disorders, including IBS. Onset of IBS is common after gastroenteritis-induced alterations of the microbiome [52], as is the onset of FD [38]. The overall bacterial structure and composition of gastric fluid in patients with FD was found to be different compared to healthy controls in one of the studies performed by Nakae et al. [53, 54]. The bacterial difference was restored to the composition of normal healthy controls after using Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 (LG21) strain of probiotics [53–55]. A similar study performed by Igarashi et al. in patients with FD associated with H. pylori infection had significant improvement in postprandial symptoms without change in H. pylori number or activity. They suggested that the reflux of small intestinal contents including bile acids and intestinal bacteria to the stomach might be inducing a bacterial composition change which may be the pathophysiological process involved in the causation of FD [54]. Although the above hypothesis appears to explain the symptoms of FD, it fails in identifying the causating factor of reflux of small intestinal contents into the stomach which could be the underlying etiology. It has been postulated that the gut microbiota, enteroendocrine cells, immune cells and enteric nervous system are interactive and function in a complex circuit system and by unclear mechanisms, the disruption or alterations in gut microbiota has a significant role in the development of functional gastrointestinal disorders including FD [56]. Difficulties in studying and comprehending the vast range and interactions of microbiota presently preclude any comprehensive understanding.

Genetics in FD

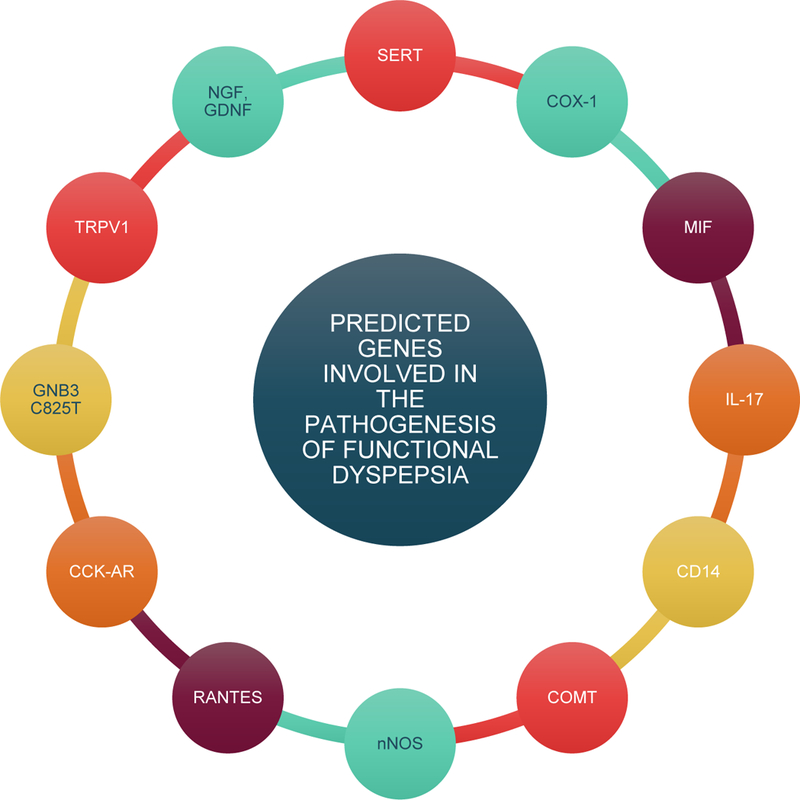

Genetics is another area under research in FD. Recent studies show the association of hereditary factors with FD with a variety of gene polymorphisms already investigated. Many researchers have studied associations between the GNB3 C825T (guanine nucleotide binding protein β3 sub unit C825T) polymorphism and FD [57, 58], notably those associated with signal transduction. The C825T is a single nucleotide polymorphism with 3 variants CC, TT, TC, located on chromosome 12 with exchange of cytosine to thymidine. The 825T (TT TC) allele is associated with alternate splicing and enhanced activation of G-protein. The CC variant is associated with diminished transduction. The C825T allele is a genetic marker for immune activation [59]. Allelic varieties have differential relations within a symptomatic Japanese population whereas the CC variant was, likewise, in a Caucasian population [60, 61]. A study of FD by Vanheel et al. [26] related impaired mucosal integrity to mild inflammation. Abnormal expression of cell-cell adhesion proteins was noted, i.e., abnormal expression of OCLN (occludin) and ZO1(zona occludin) were involved in the leak pathway. This may induce leakage of antigens or bacteria into duodenal layers causing mild inflammatory characteristics of FD. Decreased transepithelial electrical resistance and increased paracellular permeability were also documented [26]. A study conducted by Choi et al. found a relation between nociceptor related genes, H. pylori, and FD, as H. pylori infection increased expression of genes involved in pain signal transmission – NGF (nerve growth factor), GDNF (glial-derived neurotropic factor), and TRPV1(transient receptor potential cation subfamily V1) [62] (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Genes presumed to be involved in the pathophysiology of FD.

Investigators have studied association between multiple genes and functional dyspepsia. Some of the investigated genes are serotonin transporter (SERT or 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter), cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1), migration inhibitory factor (MIF), interleukin 17 (IL-17), CD14, catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS or NOS1), regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), cholecystokinin A receptor (CCK-AR), guanine nucleotide binding protein β 3 subunit C825T (GNB3-C825T), transient receptor potential cation subfamily V1 (TRPV1), nerve growth factor (NGF), and glial cell-derived neurotropic factor (GDNF).

RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) is a chemotactic agent which promotes infiltration of lymphocytes. A Japanese study of the frequency of RANTES polymorphism in H. pylori-positive patients was not significant but promoter −28G allele was linked to reduced risk of PDS [63]. As this promoter polymorphism plays a major role in inflammatory immune response, the findings suggest the role of RANTES in modifing risk for H. pylori-induced dyspepsia.

Serotonin modulates visceral sensations of the gut. Although the role of serotonin is well known in depression and anxiety, its role in dyspepsia is yet to be confirmed. Alosteron is a 5HT3 antagonist used in a study showed relief in patients with dyspepsia [64]. The HT3A subunit which plays a major role in the formation of 5HT3 receptor was studied in a Caucasian population of 592 patients. A strong link was documented between the 5HT3A c-42T allele and FD [65].

Duodenum is influenced by high fat foods through cholecystokinin (CCK) receptors, which can cause dyspeptic symptoms. Administration of CCK receptor antagonists are known to reduce symptoms [66], whereas CCK signals satiety. A Japanese study in 159 patients showed 779 T carriers of CCK-1 intron 1 have increased risk of PDS [67]. Singh et al. in their study concluded that CCK-AR polymorphism, associated with defective splicing, is protective in FD [68]. Nitric oxide, one of the major neurotransmitters in the gastrointestinal tissue is widely studied for FD. It maintains basal fundic tone and relaxation [69]. Polymorphisms of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) genes were linked to satiety in FD with an odds ratio of five [70].

Other genetic markers studied were cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) gene polymorphism (in women relation to FD), migration inhibitory factor (MIF), IL-17, CD14, catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) gene, and serotonin transporter protein (SERT) polymorphism in patients suspected with FD [71–74] (Figure 4). SERT is encoded by the SLC6A4 gene and methylation levels of the gene were studied at promoter CpG islands (PCGIs), promoter non-CpG islands (PNCGIs), and gene body non-CpG islands (NPNCGIs) using bisulfate pyrosequencing. Lower methylation level in PNCGIs was seen in patients with PDS while higher methylation level in NPNCGIs was seen in patients with EPS [75]. The epigenetics of FD needs further inquiry to validate these observations. Many studies focused on Asian populations, often with small sample sizes; hence, results cannot be readily attributed to populations worldwide. Moreover, several studies did not affirm significant links between these genes and disease [76]. Though recent studies show a link and some studies showing positive correlation to family history [77], further studies are warranted.

7. Current Therapeutic Approaches

A subset of patients with H. Pylori in populations with a prevalence of the bacteria show improvement when tested and treated. Such subsets are now known as H. pylori-induced dyspepsia [39]. In patients negative for H. pylori, proton pump inhibitors are used for 8 weeks. A meta-analysis of randomized placebo controlled trial concluded that the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are more effective than placebo in reducing symptoms of dyspepsia (10% relative risk reduction with 95% confidence interval of 2.7–17.3) [78]. Tricyclic antidepressants are sometimes used in patients with persistent symptoms. Amitriptyline is known to benefit patients with ulcer-like painful functional dyspepsia [79]. In patients where these drugs do not work, prokinetics have been used. Acotiamide is an anticholinesterase drug known to restore delayed gastric emptying and impaired gastric accommodation [80]. More trials are needed to prove the efficacy of acotiamide. For patients who complain of associated stress, psychotherapy along with medical therapy can lead to improvement [81]. In a study using buspirone, a 5HT agonist, there was reduction in the symptoms of postprandial fullness, early satiation, and upper abdominal bloating [82]. Based on the results of a pilot study, there was no difference in the effect of sertraline compared to the placebo [83]. Mirtazapine was studied in 60 patients with depression, weight loss, and dyspepsia symptoms. It was noted to show improvement along with weight gain [84]. A single site study performed on pediatric patients with duodenal eosinophilia with montelukast, an anti-asthma drug and eosinophil stabilizer, showed promising results [85]. The clinical trial showed that montelukast was effective in controlling the symptoms in patients with FD but the density of eosinophils and their activation levels were unchanged after 21 days of treatment [86]. In pediatric dyspepsia patients with duodenal eosinophilia who were unresponsive to H2 blockers, a trial of oral cromolyn which is a mast cell stabilizer has shown improvement in symptoms in 89% of patients [87]. A number of trials to improve symptoms and for an effective cure are ongoing and efforts to include eosinophilic and mast cell stabilizers in the treatment of FD are being considered as these appear to be good therapeutic targets for a fairly resistant disease [88].

8. Expert Commentary

As one of the most frequent cases among patients in medical settings, symptoms of FD patients overlap with GERD and gastroparesis [89]. A study of 24-hour pH monitoring in patients with heart burn negative functional dyspepsia showed abnormal pH monitoring in 23% of patients. These patients presented with higher prevalence of epigastric pain [90]. Gastric emptying studies can rule out gastroparesis in patients at increased risk, such as diabetics. Symptoms can persist for life, with inconsistent relief. Among patients initially evaluated, if H. pylori is found this may be readily eradicated. Endoscopy is preserved for patients with persistent symptoms despite anti-secretory therapy and H. pylori treatment. It is estimated that more than 1 billion euros are spent in the UK alone with respect to diagnosis and treatment of FD. Impaired gastric accommodation, slow gastric emptying, and increased visceral sensitivity have long been thought of as main causal factors of FD. However, more recent identification of eosinophilic degranulation and recruitment of T cells that induce mild duodenal inflammation are giving rise to new insights into immune-mediated pathophysiology. These insights offer promising avenues to explore immune-mediated therapy in the future.

9. Five-Year View

Recent advances have contributed to a better understanding in immuno-pathophysiology of FD. A shift in focus has been to duodenal pathology from gastric pathology. Previously, gut motility was considered the main pathophysiological pathway but now advances in immunologic and genetic studies with open possibilities for other symptomatic mechanisms. There is evidence of close interaction between innate and acquired immune response in the pathophysiology of FD. However, it would be more informative to delineate the role of individual cell and cytokine and the underlying mechanism on the inflammatory pathophysiology and clinical symptoms in FD. Detailed studies on the role of gut-associated lymphoid tissue in infectious and non-infectious mechanisms of FD are warranted. One of the promising areas for future investigation include case-controlled studies in healthy and FD subjects to examine the changes in various pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10, and correlate with the changes in the subtypes of gut-homing T-lymphocytes, including CD4+ α4β7+CCR9+ cells with delayed gastric emptying and pathophysiological features of FD. Furthermore, potential effects of neuro-immune mechanisms and the interaction with gastro-intestinal immune response may provide insights on the enteric glial pathology in FD. In this regard, detailed studies on the role of gut microbiota and their changes under various conditions, including inflammation, stress, anxiety, and allergy, could be promising in providing insight into the pathogenesis of FD.

Further investigations on the role of eosinophils and mast cells in establishing the causal effect of these cells would advance the therapeutic strategies in the management of FD. Additionally, what are the factors involved in the high incidence of FD in allergic subjects?

A number of studies support the effect of hereditary factors in the genesis of FD. Indeed, increased frequency of TT genotype associated with increased signal transduction of GNB3 C825T may cause gastrointestinal motility problems, and decreased polymorphism of CCK-AR might be protective in FD [68]. In addition, polymorphism in other genes have also been noted in various classes of functional dyspepsia, and such gene polymorphisms could regulate, in a positive or negative manner, the inflammatory immune response and clinical symptoms in FD. However, the studies are limited and need further confirmation. Also, novel brain gut serotonin pathways that upregulate serotonin transporters in the midbrain and thalamus and its relation to FD are just beginning to be studied [91]. Finally, the studies on the epigenetic regulation of the pathophysiological features of FD are warranted.

11. Key Issues.

Functional dyspepsia is a very common condition and yet it is poorly understood.

Functional dyspepsia constitutes a serious disease burden worldwide, as patients often require invasive procedures and treatment, many of which are unproductive.

Precise pathophysiological mechanisms of functional dyspepsia are largely unknown even as psychological distress, genetic factors, infections, food intolerance, gut motility dysfunction, and allergy – alone or in combination – may cause FD.

A plausible and promising brain gut link mediated by the immune system has recently been proposed.

Duodenal inflammation and eosinophil degranulation are significant findings in recent studies.

Altered gut microbiome and allergic predisposition to functional dyspepsia are insufficiently studied.

Preliminary genetic studies indicate involvement of GNB3 C825T, CCK AR, RANTES.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The research work of DK Agrawal is supported by research grants R01HL120659, R01 HL128063, and R01HL144125 from the National Institutes of Health, USA. The content of this review article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Reference annotations

*Of interest

**Of considerable interest

- 1.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(6): 1380–1392.**This article mentions the modified classification of functional gastrointestinal disorders which comprises of 4 main categories, functional dyspepsia, belching disorders, nausea and vomiting disorders, rumination disorder.

- 2.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130(5): 1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA and Hasler WL. Rome IV-Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(6):1257–1261.**This article mentions about the new Rome IV Functional GI Disorders classification and updates, changes from previously existing Rome III classification which discusses about the gut-brain interactions in GI disorders.

- 4.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, Moayyedi P. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015; 64(7): 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tack J, Piessevaux H, Couli B, Caenepeel P, Janssens J. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1998; 115(6): 1346–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mak AD,Wu JC, Chan Y, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Lee S. Dyspepsia is strongly associated with major depression and generalised anxiety disorder - a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 36(8): 800–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley NJ, Walker MM, Holtmann G. Functional dyspepsia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016; 32(6): 467–473.**This article discusses the latest advances in functional dyspepsia pathophysiology. It mentions that environment could be a dominant factor along with antibiotic exposure. It also mentions duodenal eosinophils and mast cells altering enteric neuronal function.

- 8.Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Locke GR 3rd et al. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 36(1): 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Serag HB and Talley NJ. Health-related quality of life in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003; 18(4): 387–393.**This article explains about health related quality of life in patients with functional dyspepsia.

- 10.Ochoa-Cortes F, Turco F, Linan-Rico A, et al. , Enteric Glial Cells: A New Frontier in Neurogastroenterology and Clinical Target for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22(2): 433–449.**This article explains the importance of enteric glial cells role in gastrointestinal function and proposes the treatment modalities for treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases.

- 11.Ruhl A Glial cells in the gut. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005; 17(6): 777–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tominaga K, Fujikawa Y, Tanaka F. et al. Structural changes in gastric glial cells and delayed gastric emptying as responses to early life stress and acute adulthood stress in rats. Life Sci. 2016; 148: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HS, Kim DK, Kim YB, Lee KJ. Effect of acute stress on immune cell counts and the expression of tight junction proteins in the duodenal mucosa of rats. Gut Liver. 2013; 7(2):190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirillo C, Bessissow T, Desmet AS, Vanheel H, Tack J, Vanden Berghe P. Evidence for neuronal and structural changes in submucous ganglia of patients with functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110(8): 1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka F, Tominaga K, Fujikawa Y, et al. Concentration of Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Positively Correlates with Symptoms in Functional Dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2016; 61(12): 3478–3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wouters MM and Boeckxstaens GE. Neuroimmune mechanisms in functional bowel disorders. Neth J Med. 2011; 69(2): 55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell N, Walker MM, Talley NJ. Gastrointestinal eosinophils in health, disease and functional disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 7(3):146–156.**This article discusses the role of eosinophils in gastrointestinal diseases. It also reports its associations with functional disorders.

- 18.Zuo L and Rothenberg ME. Gastrointestinal eosinophilia. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007; 27(3): 443–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothenberg ME and Cohen MB. An eosinophil hypothesis for functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5(10): 1147–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan RK, Costello RW, Durcan N, et al. Diverse effects of eosinophil cationic granule proteins on IMR-32 nerve cell signaling and survival. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005; 33(2):169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du L, Chen B, Kim JJ, Chen X, Dai N. Micro-inflammation in functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018; 30(4): e13304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talley NJ, Walker MM, Aro P, et al. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: an adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5(10):1175–1183.**This article reports the findings of duodenal eosinophilia in adults with non-ulcer dyspepsia and relating it to the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia.

- 23.Du L, Shen J, Kim JJ, Yu Y, Ma L, Dai N. Increased Duodenal Eosinophil Degranulation in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia: A Prospective Study. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 34305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker MM, Aggarwal KR, Shim LS, et al. Duodenal eosinophilia and early satiety in functional dyspepsia: confirmation of a positive association in an Australian cohort. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 29(3): 474–479.*This study reports role of duodenal eosinophilia in a subset of patients with functional dyspepsia with symptoms of satiety, abdominal pain and postprandial fullness.

- 25.Futagami S, Shindo T, Kawagoe T, et al. Migration of eosinophils and CCR2-/CD68-double positive cells into the duodenal mucosa of patients with postinfectious functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105(8): 1835–1842.*This study reports the role of duodenal macrophages in causing functional dyspepsia after an infection. They studied 136 patients who were diagnosed with functional dyspepsia based on ROME III criteria.

- 26.Vanheel H, Vicario M, Vanuytsel T, et al. Impaired duodenal mucosal integrity and low-grade inflammation in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2014; 63(2): 262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pires GV, Souza HS, Elia CC, et al. Small bowel of patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis: absence of inflammation despite the presence of major cellular components of allergic inflammation. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2004; 25(4): 253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallaert B, Desreumaux P, Copin MC, et al. Immunoreactivity for interleukin 3 and 5 and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor of intestinal mucosa in bronchial asthma. J Exp Med. 1995; 182(6): 1897–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell N, Huntley B, Beech T, Knight W. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and asthma: a manifestation of allergy? Gut, 2008; 57(7): 1026–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kindt S, Tertychnyy A, de Hertogh G, Geboes K, Tack J. Intestinal immune activation in presumed post-infectious functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009; 21(8): 832–e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Chen H, Lu H, et al. The study on the role of inflammatory cells and mediators in post-infectious functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010; 45(5): 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matos NA, Silva JF, Matsui TC, et al. Mast cell tryptase induces eosinophil recruitment in the pleural cavity of mice via proteinase-activated receptor 2. Inflammation. 2013; 36(6): 1260–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang LH, Fang XC, Pan GZ. Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Gut. 2004; 53(8): 1096–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spiller R and Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009; 136(6): 1979–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Giorgio R and Barbara G. Is irritable bowel syndrome an inflammatory disorder? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008; 10(4): 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nwokediuko SC, Ijoma UN, Obienu O, Anigbo GE, Okafor O. High degree of duodenal inflammation in Nigerians with functional dyspepsia. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013; 7: 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tack J, Demedts I, Dehondt G, et al. , Clinical and pathophysiological characteristics of acute-onset functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2002; 122(7): 1738–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mearin F, Perez-Oliveras M, Perello A, et al. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: one-year follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129(1): 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (1): CD002096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao B, Zhao J, Cheng WF, et al. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies with 12-month follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014; 48(3): 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyatt JI, Rathbone BJ, Sobala GM, et al. Gastric epithelium in the duodenum: its association with Helicobacter pylori and inflammation. J Clin Pathol. 1990; 43(12): 981–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catalano F, Branciforte G, Brogna A, et al. Helicobacter pylori-positive functional dyspepsia in elderly patients: comparison of two treatments. Dig Dis Sci. 1999; 44(5): 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naz F, Malik S, Afzal S, Anwar SA. Frequency of seropositivity of Helicobacter pylori in patients presenting with dyspepsia. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2013; 25(3–4): 50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taddesse G, Habteselassie A, Desta K, Esayas S, Bane A. Association of dyspepsia symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infections in private higher clinic, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2011; 49(2): 109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayana SM, Swai B, Maro VP, Kibiki GS. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among adult patients with dyspepsia in northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2014; 16(1): 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirbagheri SA, Khajavirad N, Rakhshani N, Ostovaneh MR, Hoseini SM, Hoseini V. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection and microscopic duodenal histopathological changes on clinical symptoms of patients with functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2012; 57(4): 967–972.*This article mentions about the possibility of H. pylori playing an important role in aggravating symptoms in functional dyspepsia.

- 47.Sugano K, Tak J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015; 64(9): 1353–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camilleri M, Lasch K, Zhou W. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. The confluence of increased permeability, inflammation, and pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012; 303(7): G775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams AM, Probert CS, Stepankova R, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Phillips A, Bland PW. Effects of microflora on the neonatal development of gut mucosal T cells and myeloid cells in the mouse. Immunology. 2006; 119(4): 470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verdu EF, Bercik P, Verma-Gandhu M, et al. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut. 2006; 55(2): 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hrncir T, Stepankova R, Kozakova H, Hudcovic T, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H. Gut microbiota and lipopolysaccharide content of the diet influence development of regulatory T cells: studies in germ-free mice. BMC Immunol. 2008; 9: 65.*This article puts emphasis on the microbiota and microbial components of sterile diet in the development of normal functioning immune system.

- 52.Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Biagi E, Heilig HG, et al. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011; 141(5): 1792–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakae H, Tsuda A, Matsuoka T, Mine T, Koga Y. Gastric microbiota in the functional dyspepsia patients treated with probiotic yogurt. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016; 3(1): e000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Igarashi M, Nakae H, Matsuoka T, et al. Alteration in the gastric microbiota and its restoration by probiotics in patients with functional dyspepsia. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017; 4(1): e000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takagi A, Yanagi H, Ozawa H, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 on Helicobacter pylori-Associated Dyspepsia: A Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016; 2016: 7490452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukui H, Xu X, Miwa H. Role of Gut Microbiota-Gut Hormone Axis in the Pathophysiology of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018; 24(3): 367–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park MI. Is There Enough Evidence for the Association of GNbeta3 C825T Polymorphism With Functional Dyspepsia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012; 18(3): 348–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim HG, Lee KJ, Lim SG, Jung JY, Cho SW. G-Protein Beta3 Subunit C825T Polymorphism in Patients With Overlap Syndrome of Functional Dyspepsia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012; 18(2): 205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lindemann M, Virchow S, Ramann F, et al. The G protein beta3 subunit 825T allele is a genetic marker for enhanced T cell response. FEBS Lett. 2001; 495(1–2): 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holtmann G, Siffert W, Haag S, et al. G-protein beta 3 subunit 825 CC genotype is associated with unexplained (functional) dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004; 126(4): 971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tahara T, Arisawa T, Shibata T, et al. , Homozygous 825T allele of the GNB3 protein influences the susceptibility of Japanese to dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008; 53(3): 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi YJ, Kim N, Kim J, Lee DH, Park JH, Jung HC. Upregulation of Vanilloid Receptor-1 in Functional Dyspepsia With or Without Helicobacter pylori Infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(19): e3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tahara T, Shibata T, Yamashita H, Hirata I, Arisawa T. The Role of RANTES Promoter Polymorphism in Functional Dyspepsia. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009; 45(2): 235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Talley NJ, Van Zanten SV, Saez LR, et al. A dose-ranging, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of alosetron in patients with functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001; 15(4): 525–537.*This study mentions that alosetron has benefited in relieving the symptoms of functional dyspepsia. 320 patients were recruited in this multicenter randomized control clinical trial.

- 65.Mujakovic S, ter Linde JJ, de Wit NJ, et al. Serotonin receptor 3A polymorphism c.−42C > T is associated with severe dyspepsia. BMC Med Genet. 2011; 12: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feinle C, Meier O, Otto B, D’Amato M, Fried M. Role of duodenal lipid and cholecystokinin A receptors in the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2001; 48(3): 347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tahara T, Arisawa T, Shibata T, et al. 779 TC of CCK-1 intron 1 is associated with postprandial syndrome (PDS) in Japanese male subjects. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009; 56(93):1245–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh R, Mittal B, Ghoshal UC. Functional dyspepsia is associated with GNbeta3 C825T and CCK-AR T/C polymorphism. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 28(2): 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuiken SD, Vergeer M, Heisterkamp SH, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Role of nitric oxide in gastric motor and sensory functions in healthy subjects. Gut. 2002; 51(2): 212–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park JM, Baeg MK, Lim CH, Cho YK, Choi MG. Nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2014; 59(1): 72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) are associated with functional dyspepsia in Japanese women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008; 17(6): 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of molecules associated with inflammation and immune response in Japanese subjects with functional dyspepsia. Int J Mol Med. 2007; 20(5): 717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tahara T, Arisawa T, Shibata T, Nakamura M, Wang F, Hirata I. COMT gene val158met polymorphism in patients with dyspeptic symptoms. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008; 55(84): 979–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tahara T, Arisawa T, Shibata T, et al. A Genetic Variant of the CD14 C-159T in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia (FD) in Japanese Subjects. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2008; 42(2): 104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tahara T, Shibata T, Okubo M, et al. Change in DNA methylation patterns of SLC6A4 gene in the gastric mucosa in functional dyspepsia. PLoS One. 2014; 9(8): e105565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Lelyveld N, Linde JT, Schipper M, Samsom M. Candidate genotypes associated with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008; 20(7): 767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gathaiya N, Locke GR 3rd, Camilleri M, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Novel associations with dyspepsia: a community-based study of familial aggregation, sleep dysfunction and somatization. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(9): 922–e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, et al. Effects of proton-pump inhibitors on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5(2): 178–185.*This meta-analyses concludes that proton pump inhibitors can reduce the symptoms in functional dyspepsia with ulcer like and reflux like symptoms.

- 79.Abraham NS, Moayyedi P, Daniels B, Veldhuyzen Van Zanten SJ. Systematic review: the methodological quality of trials affects estimates of treatment efficacy in functional (non-ulcer) dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 19(6): 631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kusunoki H, Haruma K, Manabe N, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of acotiamide in patients with functional dyspepsia based on enhanced postprandial gastric accommodation and emptying: randomized controlled study evaluation by real-time ultrasonography. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012; 24(6): 540–545, e250–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Orive M, Barrio I, Orive VM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a 10 week group psychotherapeutic treatment added to standard medical treatment in patients with functional dyspepsia. J Psychosom Res. 2015; 78(6): 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, Farre R, Van Oudenhove L. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 10(11): 1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tan VP, Cheung TK, Wong WM, Pang R, Wong BC. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with sertraline: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012; 18(42): 6127–6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang SM, Jia L, Liu J, Shi MM, Xu MZ. Beneficial effects of antidepressant mirtazapine in functional dyspepsia patients with weight loss. World J Gastroenterol. 2016; 22(22): 5260–5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friesen CA, Kearns GL, Andre L, Neustrom M, Roberts CC, Abdel-Rahman SM. Clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics of montelukast in dyspeptic children with duodenal eosinophilia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004; 38(3): 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Friesen CA, Neilan NA, Schurman JV, Taylor DL, Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM. Montelukast in the treatment of duodenal eosinophilia in children with dyspepsia: effect on eosinophil density and activation in relation to pharmacokinetics. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009; 9: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Friesen CA, Sandridge L, Andre L, Roberts CC, Abdel-Rahman SM. Mucosal eosinophilia and response to H1/H2 antagonist and cromolyn therapy in pediatric dyspepsia. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006; 45(2): 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Friesen CA, Schurman JV, Colombo JM, Abdel-Rahman SM. Eosinophils and mast cells as therapeutic targets in pediatric functional dyspepsia. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 4(4): 86–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Overlap of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux in the general population: one disease or distinct entities? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012; 24(3): 229–234, e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Lee KJ, Sifrim D, Janssens J. Prevalence of acid reflux in functional dyspepsia and its association with symptom profile. Gut. 2005; 54(10): 1370–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tominaga K, Tsumoto C, Ataka S, et al. Regional brain disorders of serotonin neurotransmission are associated with functional dyspepsia. Life Sci. 2015; 137: 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]