Abstract

Autosomal-dominant spinocerebellar ataxias, autosomal-recessive spinocerebellar ataxias, and hereditary spastic paraplegias have traditionally been designated in separate clinicogenetic disease classifications. This classification system still largely frames clinical thinking and genetic workup in clinical practice. Yet, with the advent of next-generation sequencing, phenotypically unbiased studies have revealed the limitations of this classification system. Various genes (eg, SPG7, SYNE1, PNPLA6) traditionally rooted in either the ataxia or hereditary spastic paraplegia classification system have now been shown to cause ataxia on the one end of the disease continuum and hereditary spastic paraplegia on the other. Other genes such as GBA2 and KIF1C were almost simultaneously published as both a hereditary spastic paraplegia and an ataxia gene. The variability and fluidity of observed phenotypes along the ataxia-spasticity spectrum warrants a rethinking of the traditional classification system. We propose to replace this divisive diagnosis-driven ataxia and hereditary spastic paraplegia classification system by a descriptive, unbiased approach of modular phenotyping. This approach is also open to expansion of the phenotype beyond ataxia and spasticity, which often occur as part of broader multisystem neuronal dysfunction. The concept of a continuous ataxia-spasticity disease spectrum is further supported by ataxias and hereditary spastic paraplegias sharing not only overlapping phenotypes and underlying genes, but also common cellular pathways and disease mechanisms. This suggests a shared vulnerability of cerebellar and corticospinal neurons for common pathophysiological processes. It might be this mechanistic overlap that drives their clinical overlap. A mechanistically inspired classification system will help to pave the way for mechanism-based strategies for drug development.

Keywords: spinocerebellar ataxia, recessive ataxia, hereditary spastic paraplegia, genetics, classification, pathway, molecular

Hereditary spinocerebellar ataxias and hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) each define a genetically heterogeneous group of rare degenerative disorders characterized by progressive degeneration of the cerebellar Purkinje cells and spinocerebellar tracts (ataxias) and corticospinal tracts (HSPs), respectively. They were traditionally designated in separate clinicogenetic disease classifications, according to the predominant disease phenotype on first gene locus description and to the mode of inheritance:

Neurodegenerative diseases first conceptualized as autosomal-dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) were classified in the SCA classification, which entails 43 SCA subtypes to date.1

Neurodegenerative diseases first described as autosomal-recessive spinocerebellar ataxias (SCARs) were classified in the SCAR classification, comprising 24 subtypes.1 This SCAR classification is partly paralleled and duplicated, yet with different numbers, by another autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia (ARCA) classification, the ARCA classification.1

Neurodegenerative diseases first reported with spastic paraplegia were classified in the spastic paraplegia gene (SPG) classification irrespective of mode of inheritance. Seventy-eight distinct SPG loci are currently reported by OMIM.1

A small number of genes presenting with combined ataxia and spasticity were somewhat arbitrarily also categorized as spastic ataxia genes (SPAX/SAX). The 7 loci listed in these classifications are mostly duplicate entries also contained in either the HSP or ataxia classification systems.

Each of these classification systems bears in itself the same problems known from similar classification systems of other movement disorders (for a broader discussion, see the analysis by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Task Force2). These include (1) erroneously assigned loci, (2) duplicated loci, (3) missing symbols or loci, and (4) unconfirmed loci and genes.2 For example, some recessive ataxias are not contained in the SCAR or the ARCA list (eg, Friedreich’s ataxia or AOA1), and some recessive ataxias are listed only in one of them (eg, AOA2 only in SCAR classification). Moreover, some dominant ataxias can also be inherited in a recessive manner and vice versa (GRID2,3 AFG3L2,4 SPTBN25), making it difficult to designate them as either on the SCA or the SCAR/ARCA list (or both). Most important, the systematic value of each of these classification systems is also very limited. Numbers in the SCA/ARCA/SCAR/SPG lists are assigned in the order in which the disease was identified (initially by linkage analysis and more recently by gene discovery). Yet these numbers do not carry any systematic information in themselves that might help to facilitate clinical diagnostics, to understand the disease etiology, or to devise treatment strategies.

In addition to these shortcomings, each of these classification systems carries in itself the classification systems for ataxias and HSPs that also bear a particular limitation when seen together. They suggest a conceptual and classificatory divide between ataxias and HSPs, when in fact there exists a large phenotypic, genetic, and pathophysiological overlap. This intersection between ataxias and HSPs has been increasingly acknowledged throughout the last decade,6 but its appreciation was notably facilitated by recent next-generation sequencing (NGS) studies. Classic clinical and genetic strategies were largely constrained by preexisting clinical conceptions, classifications, and diagnostic workflows, leading to confirmation bias in genotype-phenotype correlation studies. In contrast, NGS has facilitated gene discoveries and phenotypic classifications unbiased from prior clinical and diagnostic preconceptions. This development has led to further weakening and even partial removal of the defined boundaries between ataxias and HSPs. As we show here, recent NGS and related genomic studies have demonstrated

a rapidly increasing number of both novel genes and long-established “ataxia genes” and “HSP genes,” causing a phenotypic spectrum ranging from ataxia to HSP as 2 extremes on a continuous spectrum;

shared pathways and mechanisms between ataxias and HSPs.

We thus argue to move on from the linkage-inspired divisive classifications system of largely distinct ataxias and HSP categories toward a more modular understanding of phenotypes that reflects the increasingly complex relationship between genotype, neuronal system damage, and phenotypic expression. The frequent co-occurrence of ataxia and spasticity might thereby be driven by shared vulnerability of corticospinal tract axons and cerebellar circuits toward disturbances of the same molecular pathways (for graphical overview of the main hypothesis and concept proposed here, see Fig. 1). A mechanistically inspired classification system will prioritize research on shared pathways and pave the way for mechanism-based strategies for drug development.

FIG. 1.

From clinical diagnosis to modular phenotyping and underlying shared genes and pathways in ataxia-spasticity spectrum diseases. Ataxias and HSPs have traditionally been designated in separate clinicogenetic disease classifications, depending on the first phenotypic descriptions and pattern of inheritance, namely, either in autosomal-dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) and autosomal-recessive spinocerebellar ataxias (SCARs) or hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs/SPGs). However, the molecular etiologies of these 2 disease groups overlap greatly, based on manifold shared disease genes (top). Moreover, proteins encoded by HSP and ataxia genes closely interact physically as well as functionally. The heterogeneous genetic etiology of HSPs and ataxias thus converges into a small number of cellular pathways that are dysregulated in both diseases (right). Selective vulnerability of specific neuronal cell types that can be modified by additional genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors ultimately determines which neuronal systems and circuits will be affected by the pathway dysfunction (bottom). In ataxia-spasticity spectrum diseases, cerebellar and corticospinal tract neurons share selective vulnerabilities. The individual phenotypic expression (left) is a result of the pattern of neuronal system affection. It is essential to appreciate these 4 aspects, not only to understand an individual’s disease, but also to use all therapeutic routes, whether they be symptomatic or causal/disease modifying. Pathway-based treatment approaches are hereby particularly promising, as (1) they offer the potential to cure, not only to modify the disease condition, with the (2) pathway-based etiologies partly converging from the vastly heterogeneous genetic etiology. Targeting dysfunctional pathways rather than single genes or disease conditions thus has the potential to address whole groups of genetically defined ASS diseases. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discovering the Phenotypic and Genetic Spectrum From the Extremes

Discovery of an increasing number of genes causing both prominent cerebellar and predominantly pyramidal phenotypes over the past few years has raised awareness of the substantial overlap between these 2 disease classifications. Thereby, the “divide” was closed from both sides: classical “HSP genes” were discovered to cause ataxia as well as classical “ataxia genes” were recognized to result in HSP phenotypes.

For genes discovered in the pre-NGS era, it commonly took years (and, in some cases, the phenotypically unbiased screening approaches enabled by NGS application) to overcome the preconception of the predominant phenotype associated with a gene. SPG7, identified as a cause of HSP in 1998,7 was not systematically considered a cause of predominant (and even pure) cerebellar ataxia until 15 years later.8 Yet, within the past 2 years, it has been appreciated as one of the most common causes of autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia,9,10 and the cerebellar features may be even more pronounced than spasticity in some cohorts.10 Mutations in PNPLA6 were identified as a cause of autosomal-recessive HSP complicated by motor axonal neuropathy in 2008, leading to the designation SPG39.11 However, it was not before 2014 that mutations in PNPLA6 were also appreciated as a cause of predominant cerebellar ataxia,12,13 and it has now been shown that PNPLA6 mutations can even cause pure cerebellar ataxia.14 In light of these observations of patients with predominant or pure cerebellar disease, the terms “SPG7” and “SPG39” reflect the historical meaning at best — and appear to be misnomers for these patients and phenotypes. The fatty acid 2-hydroxylase gene (FA2H) is even part of multiple classification systems. After initially being discovered as the causative gene for leukodystrophy associated with spastic paraparesis and dystonia,15 it was published 2 years later as a novel HSP gene (SPG35),16 only to be recognized to cause a novel form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) termed FAHN — FA2H-associated neurodegeneration — a few months later.17 Not until recently, the substantial cerebellar ataxia present in many patients with FA2H mutations was systematically recognized.18,19

Likewise, HSP phenotypes were often recognized belatedly for “traditional” ataxia genes. Recessive mutations in SYNE1 were identified as a cause of cerebellar ataxia in 200720 and consequently designated ARCA1 and SCAR8. For almost a decade mutations in SYNE1 were thought to cause a slowly progressive, largely pure cerebellar ataxia,21,22 before it was realized in 2016 that they are in fact causative for a broad pleiotropic phenotypic spectrum, with corticospinal tract damage and even predominant complicated HSP presentations among the most frequent features.23,24 Recessive mutations in PLA2G6 were found in 2006 to cause, among others, a childhood-onset ataxia cluster (termed infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy).25 Although concomitant corticospinal tract features have already been described in several reports in recent years, it was not until recently that complicated HSP has been acknowledged as one of the main phenotypic presentations of PLA2G6 (Ozes et al, submitted). Biallelic STUB1 mutations were first published as a cause of recessive ataxia (eg, as part of a Gordon Holmes syndrome).26,27 Later studies then revealed that corticospinal tract damage is a frequent concomitant feature28 and sometimes even is predominate in the clinical presentation.29 Examples can also be found for recently identified autosomal-dominant disease genes. Dominant mutations in KCNA2 were first reported as a cause of (early-onset) cerebellar ataxia in 2015,30,31 before it was shown in 2016 that dominant KCNA2 mutations can also cause HSP phenotypes,32 with both phenotypes occurring on a phenotypic continuum.

NGS has sped up not only disease gene discovery but also the time span from disease gene discovery until a broadened phenotypic spectrum can be appreciated. In some cases, this has led to the almost simultaneous “discovery” of one and the same gene as a novel ataxia gene and an HSP gene. Autosomal-recessive mutations in the nonlysosomal glucosylceramidase gene GBA2, for example, were designated SPG46 because of the predominant lower-limb spasticity noted by the European team of researchers.33 In the same journal issue, however, GBA2 was published as a novel gene for “cerebellar ataxia with spasticity” because of the initial disease manifestation as cerebellar ataxia in this independent patient cohort.34 Similarly, KIF1C mutations were discovered to cause autosomal-recessive HSP complicated by ataxia features, termed SPG58.35 At the same time, however, it was discovered that KIF1C mutations can also cause predominant cerebellar ataxia (with variable spasticity of the lower limbs).36

These recent examples underscore the value of unbiased screening approaches enabled by NGS technology that — when combined with a modular phenotyping approach — enable rapid and comprehensive delineation of phenotypic spectra associated with Mendelian disease genes. Moreover, they illustrate that cerebellar and pyramidal disease manifestations commonly cooccur and can vary considerably in predominance and phenotypic expression along a continuous spectrum. This variable phenotypic presentation therefore does not justify the classification of these ataxia-spasticity spectrum genes as SPG versus SCA/SCAR/ARCA genes. The distinct SPG-versus-SCA/SCAR/ARCA classification system fails to capture this inherent phenotypic fluidity, rendering it in part arbitrary, and is therefore of limited systematic value for clinic and research.

Large Common Genetic Basis of Ataxias and HSPs

The aforementioned examples of ataxia-spasticity spectrum (ASS) genes are part of a larger, rapidly growing list of genes causing ataxia and HSP on a phenotypic continuum. Based on review of the literature and our own experience with whole-exome sequencing (WES) and whole-genome sequencing of large cohorts of cases with ataxia and/or HSP, we have compiled an extendable list of 69 genes that we consider relevant in the differential diagnosis of ASS disease (Table 1). We included only genes the phenotypic descriptions of which included both ataxia and spasticity (rather than merely pyramidal signs) in subjects from at least 2 different families (rather than merely single cases). The majority of these ASS genes cause autosomal-recessive disease (n = 49), but autosomal-dominant (n = 16) and X-linked recessive (n = 3) modes of inheritance also occur. For mutations in AFG3L2, autosomal-recessive (SCAR5) and autosomal-dominant (SCA28) modes of inheritance have been established. Notably, only 29 genes (42%) are part of either of the HSP or ataxia classification systems mentioned above (SCA/SCAR/ARCA/SPG). Consequently, even combining disease genes contained in either of the HSP or ataxia classifications is insufficient to capture the relevant disease genes for the ASS. The implications for clinical and genetic diagnostic practice are apparent: NGS-based approaches to test for mutations in ataxia genes (“ataxia panels”) need to also comprise HSP genes and vice versa to do the overlapping disease spectra justice; in addition, both ataxia and HSP gene panels should be expanded to cover not only the relevant genes “by classification,” but need to go beyond classification systems to cover also genes not included in any of the classification systems.

TABLE 1.

Genes causing ataxia and HSP (ataxia-HSP spectrum disease genes)

| Gene | Locus | Protein name (UniProt) | Inheritance | OMIM | Remarks | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCD1 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily D member 1 | XR | #300100 | Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN); increased very long-chain fatty acids in plasma | 67 | |

| ABHD12 | Monoacylglycerol lipase ABHD12 | AR | #612674 | Peripheral neuropathy, hearing loss, retinitis pigmentosa, cataract (PHARC) | 43 | |

| AFG3L2 | SPAX5 (AR), SCA28 (AD) | AFG3-like protein 2 | AR/AD | #614487 | Catalytic subunit of the m-AAA protease (like paraplegin/SPG7); ophthalmoparesis, slow saccades, ptosis | 4 |

| ARSA | Arylsulfatase A | AR | #250100 | Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD): reduced arylsulfatase A activity in leukocytes | 68 | |

| ATN1 | Atrophin-1 | AD | #125370 | Dentatorubral-pallidolysian atrophy (DRPLA); CAG trinucleotide expansion; myoclonic epilepsy, dementia, ataxia, and choreoathetosis; rare outside Japan | 69 | |

| ATP13A2 | SPG78 | Probable cation-transporting ATPase 13A2 | AR | #606693 | Juvenile parkinsonism, vertical gaze palsy, cognitive deficits | 70 |

| ATXN1 | SCA1 | Ataxin-1 | AD | #164400 | CAG trinucleotide expansion | 71 |

| ATXN2 | SCA2 | Ataxin-2 | AD | #183090 | CAG trinucleotide expansion; slow horizontal saccades | 72 |

| ATXN3 | SCA3 | Ataxin-3 | AD | #109150 | CAG trinucleotide expansion; Machado-Joseph disease; frequent SCA in central Europe | 73 |

| ATXN8/ATXN8OS | SCA8 | Ataxin-8; putative protein ATXN8OS | AD | #608768 | Expanded CTG trinucleotide repeat in ATXN8OS gene and complementary CAG repeat in ATXN8 gene | 74 |

| AUH | Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase, mitochondrial | AR | #250950 | 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type 1 (MCGA1): elevated levels of 3-methylglutaconic acid (3-MGA), 3-methylglutaric acid (3-MG) and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid (3-HIVA) in urine; cognitive deficits | 75 | |

| CAPN1 | SPG76 | Calpain-1 catalytic subunit | AR | #616907 | Upper limb involvement, foot deformities, dysarthria | 76 |

| CYP27A1 | Sterol 26-hydroxylase, mitochondrial | AR | #213700 | Cerebrotendinous xynthomatosis (CTX): juvenile cataract, lipid deposits i.a. in brain, lungs, and Achilles tendons, chronic diarrhea, early atherosclerosis, elevated levels of cholestanol in plasma | 77,78 | |

| CYP7B1 | SPG5 | 25-Hydroxycholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase | AR | #270800 | Afferent ataxia due to dorsal column dysfunction, elevated levels of 27-hydroxycholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol, and cholestanoic acid in plasma and CSF | 79,80 |

| DARS2 | Aspartate-tRNA ligase, mitochondrial | AR | #611105 | Leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation (LBSL) | 81 | |

| EXOSC3 | PCH1B | Exosome complex component RRP40 | AR | #614678 | Pontocerebellar hypoplasia, type 1B | 82 |

| FA2H | SPG35 | Fatty acid 2-hydroxylase | AR | #612319 | Spastic paraplegia, leukodystrophy, and/or brain iron deposition | 18,19 |

| FXN | Frataxin | AR | #229300 | Friedreich ataxia (FRDA); predominant afferent ataxia with pyramidal tract signs | 83 | |

| GALC | Galactocerebrosidase | AR | #245200 | Krabbe disease: infantile forms with extreme irritability, spasticity, and developmental delay; late-adult forms: spasticity, ataxia; reduced GALC enzyme activity | 84 | |

| GAN | Gigaxonin | AR | #256850 | Giant axonal neuropathy (GAN1); infantile form: kinky hair and unique posture of legs | 85 | |

| GBA2 | SPG46 | Nonlysosomal glucosylceramidase | AR | #614409 | Mental impairment, cataracts, cerebral, cerebellar, and corpus callosum atrophy | 33 |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein | AD | #203450 | Alexander disease; infantile form: leukoencephalopathy with macrocephaly, seizures, and psychomotor retardation; adult form: bulbar signs and spasticity, more slowly progressive | 86 | |

| GJC2 | SPG44, HLD2 | Gap junction gamma-2 protein | AR | #613206, #608804 | Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy; Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease (PMLD) | 87 |

| GLB1 | Beta-galactosidase | AR | #230500, #230600, #230650 | GM1-gangliosidosis, type I-III (GLB1); mucopolysaccharidosis type IVB (Morquio syndrome B); reduced beta-galactosidase-1 enzyme activity | 88 | |

| GLRX5 | Glutaredoxin-related protein 5, mitochondrial | AR | #616859 | Increased serum glycine; leukodystrophy and/or lesions in the upper spinal cord | 89 | |

| GRID2 | SCAR18 | Glutamate receptor ionotropic, delta-2 | AR | #616204 | Early-onset cerebellar ataxia, intellectual disability; occasional or persistent tonic upgaze | 90 |

| HEXA | Beta-hexosaminidase subunit alpha | AR | #272800 | Tay-Sachs disease/GM2-gangliosidosis; infantile: developmental retardation, followed by paresis, cognitive decline, and blindness; adult: lower motor neuron damage, psychosis, dementia; reduced hexosamindase A enzyme activity | 91 | |

| KCNA2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 2 | AD | #616366 | Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy; ataxia, spasticity; often de novo | 30,32 | |

| KCND3 | SCA19 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily D member 3 | AD | #607346 | Allelic with Brugada syndrome 9 | 92 |

| KIF1A | SPG30, HSN2C | Kinesin-like protein KIF1A | AR | #610357, #614213 | Allelic with autosomal-dominant mental retardation 9 (MRD9) | 93 |

| KIF1C | SPG58, SPAX2 | Kinesin-like protein KIF1C | AR | #611302 | Cerebellar ataxia and variable spasticity of the lower limbs in first 2 decades of life | 36,94 |

| MARS2 | SPAX3 | Methionine-tRNA ligase, mitochondrial | AR | #611390 | Often deletions or duplications; decreased activity of mitochondrial complexes I and IV | 95 |

| MECP2 | Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 | XR | #312750 | Atypical Rett syndrome | 96 | |

| MMADHC | Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria type D protein, mitochondrial | AR | #277410 | Homocystinuria and/or methylmalonic aciduria; usually additional complicating features like developmental delay | 97 | |

| MTPAP | SPAX4 | Poly(A) RNA polymerase, mitochondrial | AR | #613672 | Childhood-onset cerebellar ataxia, spastic paraparesis, dysarthria, and optic atrophy | 98 |

| NPC1 | Niemann-Pick C1 protein | AR | #257220 | Niemann-Pick disease, type C1/D; infantile: often accompanying neurovisceral phenotype; juvenile and adult: often vertical supranuclear gaze palsy or cognitive decline | 55,99 | |

| NPC2 | Epididymal secretory protein E1 | AR | #607625 | Niemann-Pick disease, type C2; infantile: often accompanying neurovisceral phenotype; juvenile and adult: often vertical supranuclear gaze palsy or cognitive decline | 55,99 | |

| OPA1 | Dynamin-like 120-kDa protein, mitochondrial | AD | #125250 | Optic atrophy plus syndrome, in particular, in cases of biallelic OPA1 mutations | 100,101 | |

| OPA3 | Optic atrophy 3 protein | AR | #258501 | Optic atrophy plus syndrome, 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, type III | 102 | |

| PDHX | Pyruvate dehydrogenase protein X component, mitochondrial | AR | #245349 | Lacticacidemia from PDX1 deficiency; often additional mental retardation, delayed psychomotor development and/or seizures | 103 | |

| PEX16 | Peroxisomal membrane protein PEX16 | AR | #614877 | Peroxisome biogenesis disorder 8B; white matter abnormalities; increased VLCFA | 104 | |

| PLA2G6 | NBIA2A | 85/88-kDa calcium-independent phospholipase A2 | AR | #256600, #610217 | Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy 1 (INAD); neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation 2B (NBIA2B), autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease 14 (PARK14) | 105,106 |

| PLP1 | SCA2 | Myelin proteolipid protein | XR | #312920, #312080 | Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD); X-linked recessive hypomyelinative leukodystrophy (HLD1) | 107 |

| PNPLA6 | SPG39 | Neuropathy target esterase | AR | #612020, #215470, #275400, #245800 | Boucher-Neuhauser syndrome, Gordon Holmes syndrome; Oliver-McFarlane syndrome, Laurence-Moon syndrome | 12 |

| POLR3A | HLD7 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase III subunit RPC1 | AR | #607694 | Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 7 (HLD7) with or without oligodontia and/or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism | 108,109 |

| POLR3B | HLD8 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase III subunit RPC2 | AR | #614381 | Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 8 (HLD8) with or without oligodontia and/or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, but leukodystrophy might also be missing | 110 |

| PRNP | Major prion protein | AD | #137440 | Familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), Gerstmann-Straussler disease (GSD), fatal familial insomnia (FFI), but also complicated HSP | 111,112 | |

| PSAP | Prosaposin | AR | #249900 | Metachromatic leukodystrophy from SAP-b deficiency; atypical Krabbe disease; atypical Gaucher disease | 113 | |

| PSEN1 | Presenilin-1 | AD | #607822 | Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, sometimes complicated by spastic paraparesis and/or ataxia | 114 | |

| SACS | SPAX6 | Sacsin | AR | #270550 | Autosomal-recessive spastic ataxia Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS), early-onset ataxia with spastic paraparesis and axonal-demyelinating sensorimotor neuropathy; hypointense pontine stripes on T2-MRI | 59,115 |

| SCN8A | Sodium channel protein type 8 subunit alpha | AD | #614306 | Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy 13 (EIEE13) | 116 | |

| SDHA | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial | AR | #252011 | Mitochondrial complex II deficiency | 117 | |

| SETX | SCAR1 | Probable helicase senataxin | AR | #606002 | AD mutations in SETX are associated with ALS4 (#602433); AR mutations with early-onset ataxia with elevated alpha-fetoprotein | 118 |

| SLC17A5 | Sialin | AR | #604369, #269920 | Sialic acid storage disorder | 119 | |

| SLC25A15 | Mitochondrial ornithine transporter 1 | AR | #238970 | Hyperornithinemia-hyperammonemiahomocitrullinemia syndrome | 120 | |

| SLC2A1 | DYT9 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 | AD | #612126 | GLUT1 deficiency syndrome 1 (GLUT1); DYT9 | 121 |

| SPG11 | SPG11 | Spatacsin | AR | #604360 | cHSP with thin corpus callosum; juvenile-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-5 | 122 |

| ZFYVE26 | SPG15 | Zinc finger FYVE domain-containing protein 26 | AR | #270700 | cHSP with variable mental retardation, hearing and visual defects, and thin corpus callosum | 123 |

| SPG7 | SPG7 | Paraplegin | AR | #607259 | Variable spasticity and cerebellar ataxia | 7 |

| SPR | Sepiapterin reductase | AR | #612716 | Dopa-responsive dystonia because of sepiapterin reductase deficiency | 124 | |

| STUB1 | SCAR16 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CHIP | AR | #615768 | Spasticity and ataxia can be part of a broader multisystemic neurodegeneration, including hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and cognitive decline | 29,125 |

| SYNE1 | SCAR8 | Nesprin-1 | AR | #610743 | Cerebellar ataxia and variable spasticity and further multisystemic neurologic damage | 23,24 |

| TBP | SCA17 | TATA box-binding protein | AD | #607136 | CAG repeat expansion; Huntington’s disease-like 4; ataxia, pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs, cognitive impairments, psychosis, and seizures | 126 |

| TTC19 | Tetratricopeptide repeat protein 19, mitochondrial | AR | #615157 | Mitochondrial complex III deficiency nuclear type 2 (MC3DN2); sometimes abnormal signals putamen, caudate, and brain stem on T2-MRI | 127 | |

| TTPA | Alpha-tocopherol transfer protein | AR | #277460 | Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency | 128 | |

| TUBB4A | HLD6, DYT4 | Tubulin beta-4A chain | AD | #612438, #128101 | Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (HLD6); autosomal-dominant dystonia-4 (DYT4) | 129 |

| UCHL1 | PARK5 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 | AR | #615491 | Childhood-onset neurodegeneration with optic atrophy | 130 |

| VAMP1 | SPAX1 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 1 | AD | #108600 | Newfoundland families | 131 |

| VWA3B | SCAR22 | von Willebrand factor A domain-containing protein 3B | AR | #616948 | Intellectual disability associated with adult-onset cerebellar ataxia and spasticity | 132 |

List of genes causing ataxia-spasticity spectrum disease; we anticipate this list to grow considerably in the future (ie, dynamic, extendable list). The selection contains only genes whose phenotypic descriptions include both manifest ataxia and spasticity (rather than merely pyramidal signs) in subjects from at least 2 different families (rather than merely single cases).

OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; AD, autosomal-dominant; AR, autosomal-recessive; XR, x-chromosomal recessive.

Common Pathophysiological Pathways and Mechanisms in Ataxias and HSPs

Under the surface of the seemingly disparate clinical syndromic and diagnostic classifications between ataxias and HSPs lurk not only shared allelic genes, but also common mechanisms and pathways. In this respect, the overlap between ataxias and HSPs resembles the well-established gene and pathway overlap between amyotrohic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Like HSP and ataxias, these 2 conditions have long been considered clinically disparate syndromes. Yet, over the past decade, we have increasingly recognized that they co-occur within families and even within individuals and largely share the same genes. Consequently, ALS and FTD are now usually studied jointly as a disease spectrum. Overcoming the diagnostic divide between ALS and FTD and focusing on shared pathways instead have led to identification of major shared mechanism hubs. For example, dysfunctional nuclear-cytoplasmic transport has emerged as a common mechanistic denominator uniting not only the different clinical conditions, but also various ALS/FTD genes like C9orf72, FUS, and TARDPB.37-39

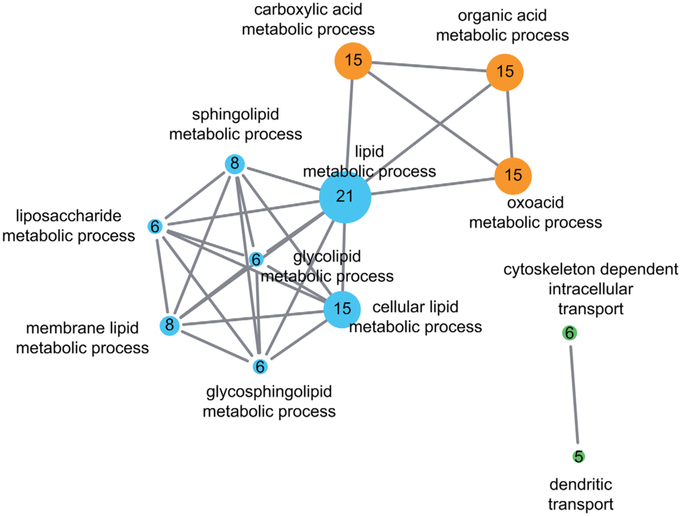

Similarly, HSP and ataxias, which share a substantial number of genes, might also be connected on a functional level via shared cellular pathways and pathomechanisms. A protein-protein interaction network using known ASS genes as seeds (Table 1, n = 63, here excluding the dominant repeat ataxias) reveals that the proteins encoded by these genes share a multitude of physical interactions and form several highly connected “protein communities” that are visualized by different colors shown in Figure 2. Functional annotation of these genes using GO terms and subsequent gene set enrichment analysis highlight functional clusters that are enriched in these proteins (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table). The 3 major functional clusters are: (1) lipid metabolic processes, (2) acid metabolic processes, and (3) cytoskeleton or dendritic intracellular transport processes. These 3 clusters represent only a small subset of molecular pathways known to be involved in HSPs or cerebellar ataxias individually. This supports the hypothesis that pathways affected in ASS reflect shared selective vulnerabilities of corticospinal and cerebellar neurons. The clinical overlap of ASS spectrum diseases might thus be driven by underlying mechanistic overlaps (for an illustration of the relation between genetic, pathway, and clinical overlaps, see Fig. 1).

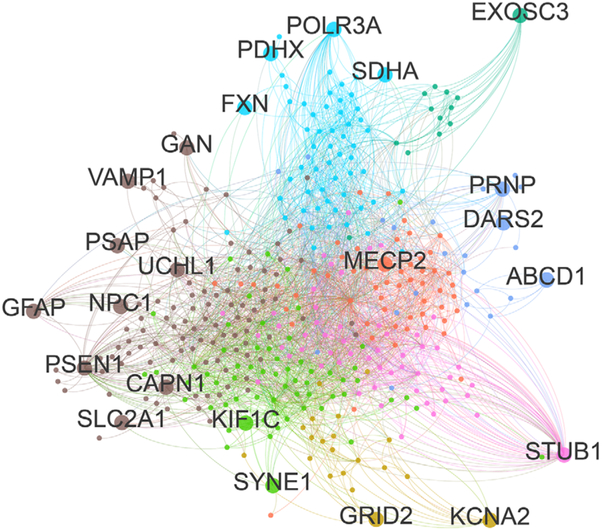

FIG. 2.

Protein-protein-interaction network for ataxia-HSP spectrum disease genes. To generate a protein-protein-interaction (PPI) network, interactors (iteration 1) of 63 spastic ataxia genes listed in Table 1 were extracted using the iRefScape plugin in Cytoscape v2.8.3.60-62 Autosomal-dominant repeat-expansion genes were removed from the seed list, as their binding properties appear to be largely shaped by their polyglutamine tracts rather than the properties of the wild-type protein. The PPI network was then imported into Gephi v0.9.1 and filtered, whereby nonhuman interactions, predicted interactions, interactions based solely on high-throughput experiments, self-loops, and nodes with a degree < 2 were removed, retaining only nodes that were maximum 1 degree removed from the input spastic ataxia seed genes. The resulting network contained 389 nodes and 2582 undirected edges. We then applied the Louvain method to detect communities, neighborhoods of highly connected nodes. A total of 8 communities were detected, represented by differently colored nodes and edges in the figure. Ataxia-spasticity spectrum seed genes are represented by larger dots and labeled with the respective gene name. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

FIG. 3.

Pathway enrichment map of ataxia-HSP spectrum gene sets. Gene-set enrichment analysis reveals several functional clusters associated with ataxia-spasticity spectrum genes. To generate the pathway, enrichment map spastic ataxia genes (Table 1, n = 63 genes; dominant repeat genes excluded) were uploaded to DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.863,64 and annotated with gene ontology terms (GOTERM_BP_FAT, GOTERM_MF_FAT).65 The fully annotated gene list is provided in the Supplementary Table. A gene enrichment map was then generated using the Enrichment Map plugin66 in Cytoscape v3.2 with the following parameters: P cutoff, 0.0001; FDR Q cutoff, 0.05; similarity cutoff overlap, 0.4. Three major enrichment clusters can be appreciated: (1) lipid metabolic processes (blue), (2) acid metabolic processes (orange), and (3) cytoskeleton or dendritic intracellular transport processes (green). Each major network contains several subnetworks highlighting a specific cellular process underlying ataxia-spasticity spectrum disease. The size of the nodes reflects the number of ataxia-spasticity spectrum genes represented in the respective functional cluster; the number of genes is also indicated by the number in each of the nodes. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Some exemplary clusters of shared or interacting pathways underlying ASS diseases are:

Phospholipid metabolism, including the genes PNPLA6,12,40,41 PLA2G6, DDHD1 (SPG 28), DDHD2 (SPG5442), CYP2U1 (SPG49), and ABHD1243 (for further overview, see references 40 and 44).

Sphingolipid metabolism, including the genes FA2H,15 GBA2,33,45 GALC, HEXA, ASA, PSAP, and GLB1.

Autophagy-lysosomal activity, including the genes SPG15, SPG11,46,47 ATP13A2 (SPG78),48,49 NPC1, and NPC2 disease.50-55

Toward a Mechanism-Based Classification of Ataxia-Spasticity Spectrum Diseases

As our concepts of cellular pathways involved in ASS diseases grow, a mechanism-based classification system of the ASS comes into reach. Classification of genetically defined disorders by shared affected pathways rather than the perceived predominant phenotype will allow overcoming the classic SCA/SCAR/ARCA and HSP/SPG divide and appreciation of a more systematic, pathophysiological perspective. Other than the resolution of multiple inconsistencies of the traditional classification system which we have detailed above, a mechanistically inspired classification system of ASS diseases offers key advantages in therapeutic respects. Such a classification system will prioritize research on shared pathways and might pave the way for mechanism-based strategies for drug development. Hypothetically, compounds targeting dysfunctional pathways rather than single genes have the potential to address groups of genetically defined diseases rather than single ataxia or HSP subtypes (for graphical illustration of this idea, see label “causal treatment strategies targeting pathways” in Fig. 1). For example, one class of drugs might target ASS diseases with abnormal cholesterol processing and cholesterol sequestration such as CYP7B1 (SPG5), NPC1, NPC2, or SERAC1 by exploiting cholesterol-depleting agents.56 Another class of drugs might aim at ASS diseases with defective autophagy-lysosomal activity (eg, SPG11, ZFYVE26, ATP13A2), using an autophagy inducer.56 A mechanism-based disease classification might thus facilitate the translation of the giant genetic progress rendered possible by NGS over the past 5 years into first targeted molecular therapies.

Conclusions for Clinical Practice

In conclusion, we suggest to give up the classificatory divide between ataxias and HSPs in favor of a concept of a clinical, genetic, and pathophysiological ASS. From this inclusive rather than discriminatory approach, a number of advantages can be inferred for current clinical practice:

Increased precision of phenotypic description and improved efficiency of diagnostic workup. Early discriminatory classification of patients into fixed diagnostic categories potentially introduces bias into the clinical and diagnostic workup. We suggest taking a modular approach to phenotyping that allows the appreciation of nuanced individual phenotypic expression along the spectrum of ataxia and spasticity. This descriptive, unbiased approach of modular phenotyping would also be open to expansion of the phenotype beyond ataxia and HSP, as ataxia and spasticity often occur not in isolation, but as part of multisystem neuronal dysfunction. It thus allows for a more comprehensive, dynamic and systematic perspective than the traditional SCA/SCAR/ARCA and HSP/SPG classifications. Avoidance of narrow-minded ataxia and HSP clinical engrams will ultimately facilitate diagnosis in so-far unexplained complex neurodegenerative disease.

Individualized treatment. Following the idea of individualized medicine, modular phenotyping allows for individualized clinical treatment and management according to each individual’s particular phenotypic spectrum (rather than by the overall clinical diagnosis or SPG/SCA/ARCA classification) (for a graphic illustration of the role of symptomatic treatment according to individual phenotype, see Figure 1). For example, patients with a major ataxia component due to PNPLA6 or SPG7 mutations will be clinically managed according to their individual ataxia, receiving, for example, physiotherapy exercises specifically targeting ataxia dysfunctions,57,58 even if these genes are traditionally grouped in the HSP/SPG classification (SPG39 and SPG7, respectively). Vice versa, patients with pronounced spasticity because of SYNE1 or STUB1 mutations will be clinically managed according to their spasticity, receiving, for example, antispastic drugs, even if these genes are traditionally grouped in ARCA classifications.

Efficient diagnostic testing. Given the variability of phenotypes across the ASS and the sheer number of ASS genes, genetic testing on a gene-by-gene basis or relying on small gene panels is inefficient and mostly obsolete. Instead, genetic testing needs to resort to large gene panels or WES covering all ASS genes. Single-gene testing in ataxia spasticity spectrum diseases should be largely reserved for a few exceptions, for example, genotyping the FRDA repeat in patients with afferent ataxia and pyramidal tract damage without major cerebellar atrophy, or the SACS gene in patients with the characteristic hypointense pontine stripes on T2-MRI imaging.59

Aggregated ASS gene panels and gene lists. In NGS diagnostics, the design of separate ataxia and HSP NGS gene panels and of separate ataxia and HSP gene lists, respectively, for WES analyses is not productive. NGS gene panels and lists need to aggregate all ASS genes.

Limitations and Future Challenges

The proposed approach of modular phenotyping bears several limitations. Patients might prefer to have a clear-cut clinical label for their disease (eg, HSP or spinocerebellar ataxia) rather than an open and dynamic broad descriptive phenotypic description of the individually affected neurological systems. A clear label might yet be given the name of the underlying gene and/or the pathway cluster. However, sporadic ASS patients without monogenic disease causation or obvious hit in one of the pathway clusters will escape classification by the proposed pathway-driven classification system.

The suggested pathway-driven classification is also limited by it requiring the affected cellular pathways to be known. For the large majority of ASS diseases, however, the pathway implications of the respective disease genes have yet to be identified. Future basic research now has to move on from NGS genetics to functional pathway explorations, both for each specific ASS gene and for possible shared pathway hubs, identifying in particular those pathway hubs that might be druggable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding agencies: This research was supported by the E-RARE-3 Joint Transnational Call grant “Preparing therapies for autosomal recessive ataxias” (PREPARE; BMBF, 01GM1607 to M.S.), the E-Rare network grant NEUROLIPID (BMBF, 01GM1408B to R.S.), the Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship (grant PIOF-GA-2012-326681 to R.S.), and by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01NS072248 (to R.S.).

Footnotes

Supporting Data

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Man OMIi. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM. Baltimore, MD: McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University; Available at: http://omim.org/ Accessed October 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marras C, Lang A, van de Warrenburg BP, et al. Nomenclature of genetic movement disorders: Recommendations of the international Parkinson and movement disorder society task force. Mov Disord 2016;31(4):436–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutelier M, Burglen L, Mundwiller E, et al. GRID2 mutations span from congenital to mild adult-onset cerebellar ataxia. Neurology 2015;84(17):1751–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierson TM, Adams D, Bonn F, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies homozygous AFG3L2 mutations in a spastic ataxianeuropathy syndrome linked to mitochondrial m-AAA proteases. PLoS Genet 2011;7(10):e1002325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lise S, Clarkson Y, Perkins E, et al. Recessive mutations in SPTBN2 implicate beta-III spectrin in both cognitive and motor development. PLoS Genet 2012;8(12):e1003074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bot ST, Willemsen MA, Vermeer S, Kremer HP, van de Warrenburg BP. Reviewing the genetic causes of spastic-ataxias. Neurology 2012;79(14):1507–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casari G, De Fusco M, Ciarmatori S, et al. Spastic paraplegia and OXPHOS impairment caused by mutations in paraplegin, a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial metalloprotease. Cell 1998;93(6):973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Gassen KL, van der Heijden CD, de Bot ST, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in spastic paraplegia type 7: a study in a large Dutch cohort. Brain 2012;135(Pt 10):2994–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeffer G, Pyle A, Griffin H, et al. SPG7 mutations are a common cause of undiagnosed ataxia. Neurology 2015;84(11):1174–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choquet K, Tetreault M, Yang S, et al. SPG7 mutations explain a significant proportion of French Canadian spastic ataxia cases. Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24(7):1016–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rainier S, Bui M, Mark E, et al. Neuropathy target esterase gene mutations cause motor neuron disease. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 82(3):780–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Synofzik M, Gonzalez MA, Lourenco CM, et al. PNPLA6 mutations cause Boucher-Neuhauser and Gordon Holmes syndromes as part of a broad neurodegenerative spectrum. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 1):69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Synofzik M, Hufnagel R, Zuchner S. PNPLA6-Related Disorders In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993–2014. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK247161/2014. Accessed August 18, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiethoff S, Bettencourt C, Paudel R, et al. Pure cerebellar ataxia with homozygous mutations in the PNPLA6 Gene. Cerebellum 2016;16(1): 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edvardson S, Hama H, Shaag A, et al. Mutations in the fatty acid 2-hydroxylase gene are associated with leukodystrophy with spastic paraparesis and dystonia. Am J Hum Genet 2008;83(5): 643–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dick KJ, Eckhardt M, Paisan-Ruiz C, et al. Mutation of FA2H underlies a complicated form of hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG35). Hum Mutat 2010;31(4):E1251–E1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruer M, Gregory A, Hayflick SJ. Fatty Acid Hydroxylase-Associated Neurodegeneration In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierson TM, Simeonov DR, Sincan M, et al. Exome sequencing and SNP analysis detect novel compound heterozygosity in fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20(4):476–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soehn AS, Rattay TW, Beck-Wodl S, et al. Uniparental disomy of chromosome 16 unmasks recessive mutations of FA2H/SPG35 in 4 families. Neurology 2016;87(2):186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gros-Louis F, Dupre N, Dion P, et al. Mutations in SYNE1 lead to a newly discovered form of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. Nat Genet 2007;39(1):80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noreau A, Bourassa CV, Szuto A, et al. SYNE1 mutations in autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. JAMA Neurol 2013;70(10): 1296–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dupre N, Gros-Louis F, Chrestian N, et al. Clinical and genetic study of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1. Ann Neurol 2007;62(1):93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Synofzik M, Smets K, Mallaret M, et al. SYNE1 ataxia is a common recessive ataxia with major non-cerebellar features: a large multi-centre study. Brain 2016;139(Pt 5):1378–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mademan I, Harmuth F, Giordano I, et al. Multisystemic SYNE1 ataxia: confirming the high frequency and extending the mutational and phenotypic spectrum. Brain 2016;139(Pt 8):e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khateeb S, Flusser H, Ofir R, et al. PLA2G6 mutation underlies infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79(5): 942–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Wang J, Li JD, et al. Identification of CHIP as a novel causative gene for autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e81884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi CH, Schisler JC, Rubel CE, et al. Ataxia and hypogonadism caused by the loss of ubiquitin ligase activity of the U box protein CHIP. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23(4):1013–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Synofzik M, Schule R, Schulze M, et al. Phenotype and frequency of STUB1 mutations: next-generation screenings in Caucasian ataxia and spastic paraplegia cohorts. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014; 9(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayer SN, Deconinck T, Bender B, et al. STUB1/CHIP mutations cause Gordon Holmes syndrome as part of a widespread multisystemic neurodegeneration: evidence from four novel mutations. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases: Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syrbe S, Hedrich UB, Riesch E, et al. De novo loss- or gain-of-function mutations in KCNA2 cause epileptic encephalopathy. Nat Genet 2015;47(4):393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pena SD, Coimbra RL. Ataxia and myoclonic epilepsy due to a heterozygous new mutation in KCNA2: proposal for a new channelopathy. Clin Genet 2015;87(2):e1–e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helbig KL, Hedrich UB, Shinde DN, et al. A recurrent mutation in KCNA2 as a novel cause of hereditary spastic paraplegia and ataxia. Ann Neurol 2016;80(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin E, Schule R, Smets K, et al. Loss of Function of Glucocerebrosidase GBA2 Is Responsible for Motor Neuron Defects in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet 2013;92(2):238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammer MB, Eleuch-Fayache G, Schottlaender LV, et al. Mutations in GBA2 cause autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia with spasticity. Am J Hum Genet 2013;92(2):245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novarino G, Fenstermaker AG, Zaki MS, et al. Exome sequencing links corticospinal motor neuron disease to common neurodegenerative disorders. Science 2014;343(6170):506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dor T, Cinnamon Y, Raymond L, et al. KIF1C mutations in two families with hereditary spastic paraparesis and cerebellar dysfunction. J Med Genet 2014;51(2):137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jovicic A, Paul JW 3rd, Gitler AD. Nuclear transport dysfunction: a common theme in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurochem 2016;138(Suppl 1):134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boeynaems S, Bogaert E, Van Damme P, Van Den Bosch L. Inside out: the role of nucleocytoplasmic transport in ALS and FTLD. Acta Neuropathol 2016;132(2):159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prpar Mihevc S, Darovic S, Kovanda A, Bajc Cesnik A, Zupunski V, Rogelj B. Nuclear trafficking in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 2017;140(Pt 1):13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tesson C, Nawara M, Salih MA, et al. Alteration of fatty-acid-metabolizing enzymes affects mitochondrial form and function in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91(6):1051–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kmoch S, Majewski J, Ramamurthy V, et al. Mutations in PNPLA6 are linked to photoreceptor degeneration and various forms of childhood blindness. Nat Commun 2015;6:5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, Geraghty MT, Kamsteeg EJ, et al. Mutations in DDHD2, encoding an intracellular phospholipase A(1), cause a recessive form of complex hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91(6):1073–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiskerstrand T, H’Mida-Ben Brahim D, Johansson S, et al. Mutations in ABHD12 cause the neurodegenerative disease PHARC: An inborn error of endocannabinoid metabolism. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87(3):410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamari F, Mochel F, Saudubray JM. An overview of inborn errors of complex lipid biosynthesis and remodelling. J Inherit Metab Dis 2015;38(1):3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sultana S, Reichbauer J, Schule R, Mochel F, Synofzik M, van der Spoel AC. Lack of enzyme activity in GBA2 mutants associated with hereditary spastic paraplegia/cerebellar ataxia (SPG46). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;465(1):35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang J, Lee S, Blackstone C. Spastic paraplegia proteins spastizin and spatacsin mediate autophagic lysosome reformation. J Clin Invest 2014;124(12):5249–5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varga RE, Khundadze M, Damme M, et al. In vivo evidence for lysosome depletion and impaired autophagic clearance in hereditary spastic paraplegia type SPG11. PLoS Genet 2015;11(8): e1005454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Estrada-Cuzcano A, Martin S, Chamova T, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the ATP13A2/PARK9 gene cause complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG78). Brain [in press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bento CF, Ashkenazi A, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Rubinsztein DC. The Parkinson’s disease-associated genes ATP13A2 and SYT11 regulate autophagy via a common pathway. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo H, Zhao M, Qiu X, et al. Niemann-Pick type C2 deficiency impairs autophagy-lysosomal activity, mitochondrial function, and TLR signaling in adipocytes. J Lipid Res 2016;57(9):1644–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tamura A, Yui N. Beta-cyclodextrin-threaded biocleavable polyrotaxanes ameliorate impaired autophagic flux in Niemann-Pick type C disease. J Biol Chem 2015;290(15):9442–9454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar S, Carroll B, Buganim Y, et al. Impaired autophagy in the lipid-storage disorder Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Cell Rep 2013;5(5):1302–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schicks J, Muller Vom Hagen J, Bauer P, et al. Niemann-Pick type C is frequent in adult ataxia with cognitive decline and vertical gaze palsy. Neurology 2013;80(12):1169–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Synofzik M, Harmuth F, Stampfer M, Muller Vom Hagen J, Schols L, Bauer P. NPC1 is enriched in unexplained early onset ataxia: a targeted high-throughput screening. J Neurol 2015; 262(11):2557–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Synofzik M, Fleszar Z, Schols L, et al. Identifying Niemann-Pick type C in early-onset ataxia: two quick clinical screening tools. J Neurol 2016;263(10):1911–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarkar S, Maetzel D, Korolchuk VI, Jaenisch R. Restarting stalled autophagy a potential therapeutic approach for the lipid storage disorder, Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Autophagy 2014;10(6): 1137–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ilg W, Synofzik M, Brotz D, Burkard S, Giese MA, Schols L. Intensive coordinative training improves motor performance in degenerative cerebellar disease. Neurology 2009;73(22):1823–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ilg W, Schatton C, Schicks J, Giese MA, Schols L, Synofzik M. Video game-based coordinative training improves ataxia in children with degenerative ataxia. Neurology 2012;79(20):2056–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Synofzik M, Soehn AS, Gburek-Augustat J, et al. Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix Saguenay (ARSACS): expanding the genetic, clinical and imaging spectrum. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003;13(11):2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Razick S, Magklaras G, Donaldson IM. iRefIndex: a consolidated protein interaction database with provenance. BMC Bioinformatics 2008;9:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Razick S, Mora A, Michalickova K, Boddie P, Donaldson IM. iRefScape. A Cytoscape plug-in for visualization and data mining of protein interaction data from iRefIndex. BMC Bioinformatics 2011;12:388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4(1):44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43(Database issue):D1049–D1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merico D, Isserlin R, Bader GD. Visualizing gene-set enrichment results using the Cytoscape plug-in enrichment map. Methods Mol Biol 2011;781:257–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mosser J, Douar AM, Sarde CO, et al. Putative X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy gene shares unexpected homology with ABC transporters. Nature 1993;361(6414):726–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rauschka H, Colsch B, Baumann N, et al. Late-onset metachromatic leukodystrophy: genotype strongly influences phenotype. Neurology 2006;67(5):859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nagafuchi S, Yanagisawa H, Sato K, et al. Dentatorubral and pallidoluysian atrophy expansion of an unstable CAG trinucleotide on chromosome 12p. Nat Genet 1994;6(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Estrada-Cuzcano A, Shaun M, Chamova T, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the ATP13A2/PARK9 gene cause complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG78). Brain 140:287–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Banfi S, Servadio A, Chung MY, et al. Identification and characterization of the gene causing type 1 spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Genet 1994;7(4):513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pulst SM, Nechiporuk A, Nechiporuk T, et al. Moderate expansion of a normally biallelic trinucleotide repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nat Genet 1996;14(3):269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawaguchi Y, Okamoto T, Taniwaki M, et al. CAG expansions in a novel gene for Machado-Joseph disease at chromosome 14q32.1. Nat Genet 1994;8(3):221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koob MD, Moseley ML, Schut LJ, et al. An untranslated CTG expansion causes a novel form of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA8). Nat Genet 1999;21(4):379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.L IJ, Loupatty FJ, Ruiter JP, Duran M, Lehnert W, Wanders RJ. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type I is caused by mutations in AUH. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71(6):1463–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gan-Or Z, Bouslam N, Birouk N, et al. Mutations in CAPN1 cause autosomal-recessive hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet 2016;98(5):1038–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cali JJ, Hsieh CL, Francke U, Russell DW. Mutations in the bile acid biosynthetic enzyme sterol 27-hydroxylase underlie cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Biol Chem 1991;266(12):7779–7783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salen G, Berginer V, Shore V, et al. Increased concentrations of cholestanol and apolipoprotein B in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Effect of chenodeoxycholic acid. N Engl J Med 1987;316(20):1233–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsaousidou MK, Ouahchi K, Warner TT, et al. Sequence alterations within CYP7B1 implicate defective cholesterol homeostasis in motor-neuron degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 2008;82(2):510–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schule R, Siddique T, Deng HX, et al. Marked accumulation of 27-hydroxycholesterol in SPG5 patients with hereditary spastic paresis. J Lipid Res 2010;51(4):819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Scheper GC, van der Klok T, van Andel RJ, et al. Mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency causes leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Nat Genet 2007;39(4):534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wan J, Yourshaw M, Mamsa H, et al. Mutations in the RNA exosome component gene EXOSC3 cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia and spinal motor neuron degeneration. Nat Genet 2012; 44(6):704–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Campuzano V, Montermini L, Molto MD, et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 1996;271(5254):1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tappino B, Biancheri R, Mort M, et al. Identification and characterization of 15 novel GALC gene mutations causing Krabbe disease. Hum Mutat 2010;31(12):E1894–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zemmouri R, Azzedine H, Assami S, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2-like presentation of an Algerian family with giant axonal neuropathy. Neuromuscul Disord 2000;10(8):592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li R, Johnson AB, Salomons G, et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein mutations in infantile, juvenile, and adult forms of Alexander disease. Ann Neurol 2005;57(3):310–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Orthmann-Murphy JL, Salsano E, Abrams CK, et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia is a novel phenotype for GJA12/GJC2 mutations. Brain 2009;132(Pt 2):426–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chakraborty S, Rafi MA, Wenger DA. Mutations in the lysosomal beta-galactosidase gene that cause the adult form of GM1 gangliosidosis. Am J Hum Genet 1994;54(6):1004–1013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baker PR 2nd, Friederich MW, Swanson MA, et al. Variant non ketotic hyperglycinemia is caused by mutations in LIAS, BOLA3 and the novel gene GLRX5. Brain 2014;137(Pt 2):366–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hills LB, Masri A, Konno K, et al. Deletions in GRID2 lead to a recessive syndrome of cerebellar ataxia and tonic upgaze in humans. Neurology 2013;81(16):1378–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Neudorfer O, Pastores GM, Zeng BJ, Gianutsos J, Zaroff CM, Kolodny EH. Late-onset Tay-Sachs disease: phenotypic characterization and genotypic correlations in 21 affected patients. Genet Med 2005;7(2):119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee YC, Durr A, Majczenko K, et al. Mutations in KCND3 cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 22. Ann Neurol 2012;72(6):859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Klebe S, Lossos A, Azzedine H, et al. KIF1A missense mutations in SPG30, an autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia: distinct phenotypes according to the nature of the mutations. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20(6):645–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Caballero Oteyza A, Battaloglu E, Ocek L, et al. Motor protein mutations cause a new form of hereditary spastic paraplegia. Neurology 2014;82(22):2007–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bayat V, Thiffault I, Jaiswal M, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial methionyl-tRNA synthetase cause a neurodegenerative phenotype in flies and a recessive ataxia (ARSAL) in humans. PLoS Biol 2012;10(3):e1001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Christodoulou J, Ho G. MECP2-Related Disorders In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Coelho D, Suormala T, Stucki M, et al. Gene identification for the cblD defect of vitamin B12 metabolism. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(14):1454–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Crosby AH, Patel H, Chioza BA, et al. Defective mitochondrial mRNA maturation is associated with spastic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87(5):655–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patterson M Niemann-Pick Disease Type C In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG, Gorman GS, et al. Multi-system neurological disease is common in patients with OPA1 mutations. Brain 2010;133(Pt 3):771–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bonifert T, Karle KN, Tonagel F, et al. Pure and syndromic optic atrophy explained by deep intronic OPA1 mutations and an intralocus modifier. Brain 2014;137(Pt 8):2164–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gunay-Aygun M, Huizing M, Anikster Y. OPA3-Related 3-Methylglutaconic Aciduria In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schiff M, Mine M, Brivet M, et al. Leigh’s disease due to a new mutation in the PDHX gene. Ann Neurol 2006;59(4):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ebberink MS, Csanyi B, Chong WK, et al. Identification of an unusual variant peroxisome biogenesis disorder caused by mutations in the PEX16 gene. J Med Genet 2010;47(9):608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ozes B, Karagoz N, Schule R, et al. New families with PLA2G6 gene mutations suggest a continuous clinical spectrum from neuroaxonal dystrophy to hereditary spastic paraplegia. [under revision]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Synofzik M, Gasser T. Moving beyond syndromic classifications in neurodegenerative disease: the example of PLA2G6. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2017;4:8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Inoue K PLP1-related inherited dysmyelinating disorders: Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease and spastic paraplegia type 2. Neurogenetics 2005;6(1):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bernard G, Chouery E, Putorti ML, et al. Mutations of POLR3A encoding a catalytic subunit of RNA polymerase Pol III cause a recessive hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2011;89(3):415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Minnerop M, Kurzwelly D, Wagner H, et al. Intronic mutations in POLR3A are a major cause of sporadic and recessive spastic ataxia [under review]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saitsu H, Osaka H, Sasaki M, et al. Mutations in POLR3A and POLR3B encoding RNA Polymerase III subunits cause an autosomal-recessive hypomyelinating leukoencephalopathy. Ame J Hum Genet 2011;89(5):644–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zarranz JJ, Digon A, Atares B, et al. Phenotypic variability in familial prion diseases due to the D178N mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76(11):1491–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Synofzik M, Bauer P, Schols L. Prion mutation D178N with highly variable disease onset and phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80(3):345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kretz KA, Carson GS, Morimoto S, Kishimoto Y, Fluharty AL, O’Brien JS. Characterization of a mutation in a family with saposin B deficiency: a glycosylation site defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990;87(7):2541–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dolzhanskaya N, Gonzalez MA, Sperziani F, et al. A novel p.Leu(381)Phe mutation in presenilin 1 is associated with very early onset and unusually fast progressing dementia as well as lysosomal inclusions typically seen in Kufs disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2014;39(1):23–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Engert JC, Berube P, Mercier J, et al. ARSACS, a spastic ataxia common in northeastern Quebec, is caused by mutations in a new gene encoding an 11.5-kb ORF. Nat Genet 2000;24(2):120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hammer MF, Wagnon JL, Mefford HC, Meisler MH. SCN8A-Related Epilepsy With Encephalopathy In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bourgeron T, Rustin P, Chretien D, et al. Mutation of a nuclear succinate dehydrogenase gene results in mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiency. Nat Genet 1995;11(2):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Anheim M, Monga B, Fleury M, et al. Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2: clinical, biological and genotype/phenotype correlation study of a cohort of 90 patients. Brain 2009;132(Pt 10): 2688–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Verheijen FW, Verbeek E, Aula N, et al. A new gene, encoding an anion transporter, is mutated in sialic acid storage diseases. Nat Genet 1999;23(4):462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Camacho JA, Obie C, Biery B, et al. Hyperornithinaemia-hyper-ammonaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome is caused by mutations in a gene encoding a mitochondrial ornithine transporter. Nat Genet 1999;22(2):151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Weber YG, Kamm C, Suls A, et al. Paroxysmal choreoathetosis/ spasticity (DYT9) is caused by a GLUT1 defect. Neurology 2011; 77(10):959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stevanin G, Santorelli FM, Azzedine H, et al. Mutations in SPG11, encoding spatacsin, are a major cause of spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum. Nat Genet 2007;39(3):366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hanein S, Martin E, Boukhris A, et al. Identification of the SPG15 gene, encoding spastizin, as a frequent cause of complicated autosomal-recessive spastic paraplegia, including Kjellin syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2008;82(4):992–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bonafe L, Thony B, Penzien JM, Czarnecki B, Blau N. Mutations in the sepiapterin reductase gene cause a novel tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent monoamine-neurotransmitter deficiency without hyperphenylalaninemia. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69(2):269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Synofzik M, Schule R, Schulze M, et al. Phenotype and frequency of STUB1 mutations: next-generation screenings in Caucasian ataxia and spastic paraplegia cohorts. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014; 9:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Koide R, Kobayashi S, Shimohata T, et al. A neurological disease caused by an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat in the TATA-binding protein gene: a new polyglutamine disease? Hum Mol Genet 1999;8(11):2047–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ghezzi D, Arzuffi P, Zordan M, et al. Mutations in TTC19 cause mitochondrial complex III deficiency and neurological impairment in humans and flies. Nat Genet 2011;43(3):259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ouahchi K, Arita M, Kayden H, et al. Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency is caused by mutations in the alpha-tocopherol transfer protein. Nat Genet 1995;9(2):141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Miyatake S, Osaka H, Shiina M, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of TUBB4A-associated hypomyelinating leukoencephalopathies. Neurology 2014;82(24):2230–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bilguvar K, Tyagi NK, Ozkara C, et al. Recessive loss of function of the neuronal ubiquitin hydrolase UCHL1 leads to early-onset progressive neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110(9):3489–3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bourassa CV, Meijer IA, Merner ND, et al. VAMP1 mutation causes dominant hereditary spastic ataxia in Newfoundland families. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91(3):548–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kawarai T, Tajima A, Kuroda Y, et al. A homozygous mutation of VWA3B causes cerebellar ataxia with intellectual disability. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87(6):656–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.