Abstract

To accelerate conformation sampling of slow dynamics from receptor or ligand, we introduced flattening potentials on selected bonded and nonbonded intramolec-ular interactions to the binding energy distribution analysis method (BEDAM) for calculating absolute binding free energies of protein-ligand complexes using an implicit solvent model, and implemented flattening BEDAM using the asynchronous replica exchange (AsyncRE) framework for performing large scale replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulations. The advantage of using the flattening feature to reduce high energy barriers was exhibited first by the p-xylene-T4 Lysozyme complex, where the intramolecular interactions of a protein sidechain on the binding site were flattened to accelerate the conformational transition of the sidechain from the trans to the gauche state when the p-xylene ligand is present in the binding site. Much more extensive flattening BEDAM simulations were performed for 53 experimental binders and 248 nonbinders of HIV-1 integrase which formed the SAMPL4 challenge, with the total simulation time of 24.3 microseconds. We demonstrated that the flattening BEDAM simulations not only substantially increase the number of true positives (and reduce false negatives) but also improve the prediction accuracy of binding poses of experimental binders. Furthermore, the values of area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and the enrichment factors at 20% cutoff calculated from the flattening BEDAM simulations were improved significantly in comparison with that of simulations without flattening as we previously reported for the whole SAMPL4 database. Detailed analysis found that the improved ability to discriminate the binding free energies between the binders and nonbinders is due to the fact that the flattening simulations reduce the reorganization free energy penalties of binders and decrease the overlap of binding free energy distributions of binders relative to that of nonbinders. This happens because the conformational ensemble distributions for both the ligand and protein in solution match those at the fully coupled (complex) state more closely when the systems are more fully sampled after the flattening potentials are applied to the intermediate states.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Predicting the binding free energy for a protein-ligand complex is a fundamental problem in biophysical chemistry and also important for structure based drug design1–7. Docking methods estimate the physical binding free energy in a very simplified way in order to perform high throughput virtual screening of a large-scale database of small molecules (on the order of millions) and find the hits at the early stage of computer aided drug design for later lead optimization8–12. Free energy perturbation (FEP) methods in explicit solvent are able to predict binding free energies more accurately through atomistic simulations of protein-ligand complexes with more detailed physical potentials and solvation environments, but because of limitation related to computing resource requirements and the fact that FEP transformations must be made between chemically similar compounds, this limits the number of calculated ligands to tens or hundreds. FEP methods are better suited for optimizing leads from the available good candidates when the environments are known more accurately (such as crystal poses)1–7. The binding energy distribution analysis method (BEDAM)13 developed in our group targets a niche between low resolution docking methods and high resolution FEP methods in explicit solvent by computing absolute binding free energies for receptor-ligand systems in implicit solvent using a single decoupling method. One of the major goals of BEDAM is refining the predicted results from docking methods and significantly reducing the number of candidates to perform further lead optimizations using FEP methods.

Absolute binding free energies can be calculated using different implementations of a statistical mechanics theory of molecular association equilibria based on atomistic molecular dynamics simulations1,6,14. Simulations are used to calculate the free energy differences between neighboring thermodynamic states along predefined paths connecting the fully decoupled (apo-protein + free ligand) state to the fully coupled (binding complex) state. These paths can be designed in a physical way such as the potential of mean force (PMF) method15 constructing the free energy profile along the distance between the ligand and the receptor, or in an alchemical way such as single decoupling (decouple the ligand directly from the receptor site to the solution environment in implicit solvent13) or double decoupling methods (decouple the ligand respectively from the receptor site and the solution environments to vacuum16from explicit solvent).The theoretical foundation of BEDAM is based on the statistical mechanics theory of molecular association6 and the Widom potential distribution theorem.17. In the BEDAM method the ligand is decoupled from the complex with full intermolecular interactions (bound state) to an uncoupled (unbound) state in the implicit solvent environment by designing a single alchemical path. This path can be realized by introducing intermediate states represented by a parameter (λb) rescaling (or weakening) the binding energy (including the intermolecular interactions and implicit solvation energies) between the ligand and the receptor.

The accuracy of binding free energy predictions, however, is limited by the difficulty of performing sufficient conformational sampling in the high-dimensional space of the coordinates and also by the approximations inherent in the force field functions describing the interactions for protein-ligand complexes and their environments. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations employing many intermediate thermodynamic states are typically limited to aggregate times of the order of milliseconds18–21 even using the latest high performance computing resources or specialized computing units22–24. Developing more advanced conformational sampling methods25–40 is one way to overcome the timescale challenge. In the BEDAM method conformational diffusion along the alchemical path (starting from an initial complex predicted by docking methods or an experimental (crystallographic) pose if it exits) connects the bound (λb = 1) to unbound states (λb = 0) and accelerates the sampling of the intermolecular (external) degrees of freedom between the ligand and receptor by employing parallel Hamiltonian replica exchange molecular dynamics (HREMD) sampling (λ hopping)35,41. Due to the rescaling of the intermolecular interaction using λb, the ability to carry out extensive intermolecular conformational sampling of the relative position and orientation of the ligand with respect to the receptor is an advantage of BEDAM13,42–45 over existing free energy perturbation (FEP) and absolute binding free energies protocols in explicit solvent.

Some evidence43,44,46, however, also clearly points out that high energy barriers from internal conformational reorganization of the ligand and/or the receptor could be the cause of slow convergence of binding free energy estimation and failure of predicting the correct binding pose (mode). Those internal degrees of freedom generally include the internal torsional coordinates of the ligand or backbone/sidechain coordinates of the protein receptor degrees of freedom which present in a binding site. In our preliminary attempt to address this issue,47 we have introduced an additional scaling parameter to reduce the torsional (including corresponding 1–4 interactions) energy barriers for the selected back-bone rotatable bonds of the ligand. But we also found that in many cases high barriers are contributed from non-native hydrogen bonds and/or aromatic ring stacking interactions due to non-bonded interactions. In this work, we introduce a more complete method which rescales all bonded and nonbonded interactions for selected intramolecular degrees of freedom (except bond stretching and angle bending terms). This is critical to accurately predict reorganization free energies (and corresponding poses) for systems involving characteristics such as (a) ligands with very different conformational distributions in the binding sites in comparison to that of the unbound state in solution; (b) ligands with incorrect initial binding poses or internal conformational predictions by docking methods; (c) large ligands with many rotatable bonds or complicated poses that can not be systematically explored by docking methods.

The flattening feature in the BEDAM method shares some similarity to the recent replica exchange with solute tempering (REST2) approach36,48 and other HREMD methods modifying interaction potentials37 or applying bias potentials.33,34,49–51 The REST2 method lowers the energy barriers (equivalent to increasing the temperature) of hotspot regions (side-chains of receptors and/or mutated functional groups of ligands in a protein-ligand binding site) by rescaling the inter or intra-molecular interactions using preselected parameters, and enhances the conformational sampling in free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations for relative binding free energies. In these HREMD methods the rescaling parameters or the functions of biasing potentials need to be preselected carefully by estimating the heights of energy barriers varied for different systems. Instead our flattening method is able to fully decouple the inter-molecular interactions and totally cancel out the related intra-molecular interactions at some thermodynamic states using the biasing potentials constructed from the corresponding force field parameters (hence no need to estimate the parameters for the biasing potentials which are difficult to specify in advance for different systems). This allows more extensive conformational sampling for larger ligands and can be applied to much larger hot-spot regions with more degrees of freedom than FEP methods.

In addition to the design of alchemical paths involving single decoupling in implicit solvent, the early BEDAM method adopted efficient computational strategies built upon parallel Hamiltonian replica exchange sampling (λ hopping)35,41 and it was implemented in the IMPACT52 molecular simulation package using the synchronous nearest-neighbor replica exchange scheme (SyncRE). However, conventional RE implemented in the synchronous way27–31,53,54 has several limitations: a) all dedicated computing resources must be secured for all replicas before the simulation and also maintained to be accessible until the RE simulation is completed; b) The simulation has zero-torrance about the failure of any replica simulation; c) the synchronizing requirement of all computing units prefers homogeneous computing environments to heterogeneous systems where the slowest computing unit determines the efficiency of whole RE simulation.

To overcome those limitations preventing the SyncRE approach from being a feasible solution for new applications that demand multi-dimensional RE algorithms employing hundreds to thousands of replicas,51,55,56 our recent work has developed an asynchronous replica exchange (AsyncRE) methodology57 and corresponding python software package58 to remove the synchronizing concept and optimize the usage of heterogeneous HPC clusters and dynamically distributed computing networks. The central idea of AsyncRE is to use a master process to assign all replicas to one of two states, “running” or “swapping”, in which “running” replicas are submitted for execution of a predetermined amount of simulation time (an MD cycle) on a remote client and “swapping” replicas periodically exchange thermodynamic parameters independently of the “running” replicas on the local server. A “running” replica becomes a “swapping” once its remote MD cycle is completed. Hence the lists of replicas which are in “running” and “swapping” are dynamically maintained. This algorithm does not require a direct network link between compute nodes as all exchanges are managed and conducted by the master process, nor does it require a static homogeneous set of compute nodes making it robust against loss of compute nodes or replica simulation failures. The AsyncRE framework is able to scale to very large numbers of replicas and take advantage of dynamically distributed and heterogeneous computational resources, including XSEDE high performance clusters, university grid networks consisting of spare computers on campus, and world-wide networks contributed by volunteer computing units. In this work, we also report implementation of BEDAM with flattening potentials in the recent AsyncRE python package using the asynchronous pair-wise exchange scheme extended to all available states57,58 which makes the large-scale flattening simulations possible using local distributed computing grids.

During the life cycle of the HIV virus, there are several important processes involving viral enzymes59. HIV integrase (HIV-IN) is responsible for the integration of the viral genome into the host genome and the human LEDGF protein is a transcription factor that links HIV integrase to the human chromosome60. Development of small molecule inhibitors targeting the LEDGF site of HIV-IN helps to prevent the LEDGF protein from binding and stops the insertion of the HIV genome into the human genome. Using the developed BEDAM method with flattening potentials we performed large scale absolute binding free energy calculations for the ligand database from the SAMPL4 blind challenge61 for binding free energy predictions in an effort to improve the prediction accuracy of binding free energies and poses. The SAMPL4 database is a focused library developed for lead optimization and consists of similar ligands grown from several common molecular scaffolds such as benzoic acid, benzodioxole acid, and benzodioxine acid45,61. Due to the relative lack of ligand chemical diversity this poses a challenge on virtual screening using docking methods that are widely used for hit discovery from diverse databases. The LEDGF binding site of HIV-IN is large and capable of accommodating a wide range of ligand sizes. Due to the ligand flexibility and large R groups including many rotatable bonds, FEP methods are not that well suited for predicting binding free energies for this library.

Methods

Binding energy distribution analysis method(BEDAM)

The BEDAM method13 calculates the absolute binding free energy between a receptor A and a ligand B by employing a λb-dependent effective potential energy function as follows:

| (1) |

where V0(r) = V (rA)+V (rB) is the potential energy of the complex (including both the receptor A and the ligand B) at the unbound state, and u(r) = u(rA, rB) = V (rA, rB)− V (rA) − V (rB) is defined as the binding energy for each complex conformation (r = (rB,rA)), corresponding to the difference between the effective potential energies V (r) with implicit solvation62,63 of the bound and unbound states of the complex with the same fixed internal conformations.

The standard free energy of binding for this system can be calculated as6,13

| (2) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature, C0 (=1M) is the the standard concentration of ligand molecules, and Vsite is the volume of the binding site13. In Eq. 2, the first term on the right , can be explained as the entropic change when moving the free ligand in the volume ( V0 ) of standard concentration into the volume of the binding site ( Vsite ) as we will discuss in more detail below. The p0(u) in the second term on the right is the probability distribution of binding energy (u(r)) collected in an appropriate decoupled ensemble of conformations in which the ligand is present in the binding site while there are no interactions between the receptor and the ligand except both with the solvent continuum. To obtain a well-sampled distribution of p0(u), a series of discretized λb values between 0 and 1 are introduced to represent intermediate thermodynamic states and define an alchemical path to decouple the ligand from the complex environment with full interactions in the receptor site (λb = 1) to a pure solvent state without protein interactions (λb = 0). Through this alchemical path, in practice the ΔGb can be calculated by summing all free energy differences between neighboring intermediate states (m states in total) as from reweighting analysis of all stored binding energies of all thermodynamic states using the unbinned WHAM method64 or other similar methods65–67.

Technically, a modified “soft-core” binding energy function is used to improve convergence of free energy differences near λb = 0 such as in the form of

| (3) |

where umax is a large positive value such as 1,000 kcal/mol in this report. This modification to the binding energy caps the maximum unfavorable value of the binding energy while leaving unchanged the value of favorable binding energies.64

One of the advantages of the BEDAM method is the ability to capture the entropic changes for binding processes13,42,43. Figure 1 illustrates the thermodynamic cycle for calculating the BEDAM binding free energies when the receptor flexibility is ignorable. In the BEDAM method, the binding process can be decomposed into two separate steps as shown in the left bottom triangle. First, the ligand reorganizes its conformational (internal and external) ensembles in the unbound state to match the distributions in the bound complex. Then receptor-ligand interactions are created in the binding site. During the second stage, there is no change in the configurational ensemble of the binding partners and hence there is no entropic change involved. The free energy change for this stage can be represented by , the average binding energy at the fully coupled state (λb = 1). We should point out that the average binding energy not only includes the interaction energies between the ligand and the receptor but also takes account of the solvation contribution (the difference of implicit solvation energy between the decoupled and fully coupled state) which cannot be obtained easily from other methods such as the double decoupling method. In contrast, in the first stage there are involved both entropic and enthalpic changes due to the reorganization of conformational ensembles which can be denoted as the reorganization free energy . From the top right triangle in Fig. 1, the reorganization free energy also includes two components: represents the free energy cost to reorganize the ligand conformational ensemble in the unbound state to be consistent with that of fully bound state; estimates the entropy loss from the external degrees of freedom of the ligand, the changes of translational and rotational motions after moving the ligand from the volume of standard state concentration V0 = 1/C0 to the volume of binding site Vsite. Note that will include the rotational part if we perform the angle and dihedral restraints for the ligand pose6,13,68. In this report, we only apply the flattened bottom harmonic potential to the distance between the center of mass of the receptor binding site and that of ligand heavy atoms. This type of restraint allows a simulation to sample the external motions of a ligand and adjust the pose predicted from the docking program which is critical to improve the docking result if the docking prediction is significantly different from the true bound state. Vsite is an ideal term which can be estimated from the accessible volume of the ligand with this restraint potential (see more details in Supporting Information) and results in a constant free energy change for all ligands6,13,68. We should emphasize that Eq. 2 is the fundamental equation for the binding free energy using the BEDAM single decoupling thermodynamic path including two contributions: an ideal term and a non-ideal term (−kBT ∫ dup0(u)e−βu), both affected by the volume of binding site (Vsite). As explained in previous references6,13, a requirement for the binding problem to be well defined is that the sum of the ideal and non ideal terms must be approximately independent of the value chosen for the binding site volume Vsite, over some range of volumes. There is a minimum value of Vsite that must be chosen that includes all binding competent poses. As the value of Vsite increases beyond this minimum value, the ideal contribution to the binding free energy becomes more favorable, and this increase in the binding strength due to the ideal term is canceled by the decreasing contribution from the nonideal term due to the contribution of binding poses with repulsive interactions which appear in the integral of the non-ideal term. The value of Vsite ≈ 900 ˚A3 was chosen for simulations of ligands binding to the LEDGF allosteric site on Integrase because in previous studies we verified that this volume is sufficiently large to include all binding competent poses, but not too large so that non-specific weakly bound poses were also included. Namely, the binding free energies do not depend on the precise value we chose for Vsite for these simulations. Further details about how to choose Vsite can be found in references6,13,68. We also note that the thermodynamic cycles of the BEDAM method described above (Fig.1) mostly neglect the conformational reorganization from the protein receptor which is positionally restrained (through heavy atoms of the CCD domain of HIV-IN) due to the little flexibility around the HIV-IN LEDGF binding site, which is apparent from an analysis of available crystallographic data from the SAMPL4 challenge45,69. When the conformational reorganization from the receptor is important the reorganization free energy should include both contributions from the receptor and the ligand. Namely more generally the reorganization free energy represents the free energy cost to reorganize the receptor and/or the ligand conformational ensemble in the unbound state to be consistent with that of fully bound state.

Figure 1:

Cartoon representation of the thermodynamic cycles of the BEDAM method.

BEDAM with flattening potentials

In the potential energy function of BEDAM (see Eq.1), binding energies (u(r)) can be treated as biasing potentials applied to protein-ligand complexes without inter-molecular interactions and λb is used to rescale the magnitude of inter-molecular interactions, equivalent to adjusting the strength of biasing potentials and accelerate the sampling of inter-molecular conformations (the relative position and orientation of the ligand with respect to the receptor).13,42–44

In addition to the rotation and translation coordinates of the ligand with respect to the receptor, however, high energy barriers42,43,46 from internal reorganization of the ligand and/or the receptor are another bottleneck for slow convergence of binding free energy estimation and for predicting the corresponding binding pose. To accelerate the sampling of those internal degrees of freedom (such as the internal torsional coordinates of the ligand or the backbone/sidechain coordinates of the protein receptor degrees of freedom which are present in a binding site), particularly, we are interested in flattening those related intra-molecular interactions (including both the bonded and the non-bonded energy terms of certain atoms). This can be achieved by applying negative potential energies to lower or totally cancel out the original high barriers as below,

| (4) |

where Vbonded(r) and Vnonbonded(r) represent the relevant bonded and non-bonded interactions to be flattened in the binding site and are applied to the system as the negative biasing energies. Note that no bond stretching and angle bending terms included in the bonded interactions are flattened, only torsional terms and corresponding 1–4 interactions from the preselected dihedral angles are included in Vbonded(r) and flattened. In contrast, Vnonbonded(r) only includes the nonbonded (L-J and Coulomb) interactions within the cutoff distance of the selected atoms. Moreover once we select the rotatable bonds and related atoms for flattening, the functions of Vbonded(r) and Vnonbonded(r) are fixed using the corresponding force field parameters and we do not need to decide what values are suitable unlike other accelerated methods using rescaling interactions36,37,48 or adding biasing potentials33,34,49–51. The magnitude (λf) of the biasing potentials can be expressed as a parametric function of λb simply as follows,

| (5) |

Using this simple function, the biasing potentials are automatically turned off (λf = 0 ) at both the fully coupled ( λb = 1) and decoupled ( λb = 0) physical states. In contrast, biasing potentials will totally cancel out (λf = 1 ) corresponding bonded and nonbonded interactions when λb = 0.5. We can also use a series of predefined values of λf independent of λb and increase the number of dimensions of λ to two which requires performing HREMD in a two dimensional space of biasing functions.

SyncRE and AsyncRE implementations of flattening BEDAM

In our preliminary implementation of BEDAM with the flattening feature for bonded interactions47, we used the SyncRE scheme through the MPI implementation in the IMPACT52 simulation package. The flattening of nonbonded interactions was also implemented as the SyncRE scheme in IMPACT. Furthermore we also implemented the flattening BEDAM code using the AsyncRE framework57,58 in order to perform largescale simulations using heterogeneous HPC clusters and distributed computing resources. More implementation details can be found in the Supporting Information.

Metrics to evaluate the performance

ROC curve and AUC value

For retrospective predictions with experimental crystallographic data available, the prediction results from the simulations can be classified as four types: 1) true positive (an experimental binder is predicted as binder.); 2) false positive (an experimental nonbinder is predicted as as binder); 3) false negative (an experimental binder is predicted as nonbinder); 4) true negative (an experimental nonbinder is predicted as nonbinder). A simple counting for different prediction types only yields basic information about the simulation results. More appropriate methods to evaluate the overall performance of prediction are accumulation curves such as the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve. To generate a ROC curve, the prediction results are ranked first according to the calculated binding free energies from the lowest to the highest value. Then the cumulative density functions (CDF) of true positives and false positives are calculated before each rank x. Namely a ROC curve is the CDF of false positive (in the x axis) .vs. CDF of true positives (in the y axis) (false positive rate vs true positive rate)70. The integrated area under a ROC curve is call the area under the curve (AUC). The AUC values from different types of predictions can be used to rank the overall performance, the higher the better prediction for the whole database.

Enrichment factor

Enrichment factor (EF) is a metric to evaluate the prediction power of early recognition from a database.71 It is a measure of how many more actives (binders in our analysis) we find within an “early recognition” fraction ( α) of the ordered database relative to a random distribution.

| (6) |

where δi is an indicator function for whether the ith active is ranked before the cutoff of m = αN (N is total number of ligands in the database). Namely, the EF at 20% measures the number of actives found at 20% of the database scanned versus the expected number you would find by random chance (20% of the total number of actives, Nactive ). This analysis does not rank all actives equally (heaviside function favoring the first fraction of the database given by α ), meaning some actives do not contribute to the score at all. Hence its value depends on the choice of the fractional cutoff parameter α.

System preparation and computational details

L99A mutant of T4 Lysozyme

The preparation of the L99A mutant of T4 Lysozyme is similar to our previous work.47 The initial structure of p-xylene (Green stick) bound to T4 Lysozyme is shown in Fig. 2. The Val111 side-chain rotameric states shown in blue (gauche state) and red (trans state). Initial structures for the complex of p-xylene with the L99A mutant of T4 Lysozyme were prepared based on the corresponding crystal structure (PDB access code 187L). The side-chain N-CA-CB-CG1 dihedral angle of the Val111 key residue of T4 Lysozyme is in trans conformation (shown as in red in Fig.2) in the protein structure with no bound p-xylene ligand; however, in the binding complex of p-xylene, the Val111 changes its rotameric state from the trans macrostate conformation (χ≈180) to the gauche (χ≈±60) conformation (χ =−60 shown as blue color in Fig.2) Note that due to the symmetry of the side chain of Val111, the N-CA-CB-CG1 dihedral angle is equivalent to that of N-CA-CB-CG2 and the conformation of χ=+60 have the same structure as that of χ=−60. 16 replicas (at λb = 0, 0.002, 0.005, 0.008, 0.01, 0.04, 0.1, 0.2, 0.35, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 0.95 and 1.0) are used for the REMD simulations to calculate the binding free energies. According to the center mass of restraints described in the Supporting Information, Vsite, is calculated as 904.7 °A3 corresponding to the value of −kBT lnC0Vsite = 0.36 kcal/mol. Other simulation parameters are also the same as the previous work47 and are summarized in the Supporting Information.

Figure 2:

Cartoon representations of T4 Lysozyme complexes with p-xylene. Green: p-xylene ligand; Red: trans conformation (χ≈ 180° for the side-chain N-CA-CB-CG1 dihedral angle) of Val111; Blue: gauche conformation (χ≈−60°).

HIV-1 integrase

The 53 experimental binders and 248 nonbinders of HIV IN complexes were built pre-viously45 as part of the HIV-1 integrase virtual screening SAMPL4 challenge61,69 for predicting likely binders to the LEDGF site of integrase72 using the BEDAM method for binding free energy calculations13,42–44. Docked structures for all ligands were obtained by using AutoDock Vina for the SAMPL4 challenge69. To make the comparison consistent with each other, 20 replicas (at λb = 0, 0.001, 0.002, 0.0033, 0.0048, 0.006, 0.008, 0.01, 0.04, 0.07, 0.1, 0.25, 0.35, 0.45, 0.55, 0.65, 0.71, 0.78, 0.85, and 1.0) are employed for all REMD simulations of all HIV-IN complexes. The volume of the binding site, Vsite, has the same value as that of T4 Lysozyme (also previous simulations45) corresponding to an entropic change of 0.36 kcal/mol. Furthermore all simulation parameters, force field parameters, and restraint methods were kept the same as the previous work45 as described in more details in the Supporting Information. We performed different types of AsyncRE BEDAM simulations for the SAMPL4 ligands as listed in Table 1. Please note that the flattening simulations with 1.2ns per replica were truncated from corresponding longer simulations of 3.0ns for the purpose of convergence analysis.

Table 1:

Summary table for different types of BEDAM simulations performed for all SAMPL4 HIV-IN complexes.

| abbreviation | SAMPL4 | CRYS | FLat-Tors(1.2) | Flat-All(1.2) | FLat-Tors(3.0) | FLat-All(3.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| starting pose | docking | crystal | docking | docking | docking | docking |

| simulation time | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 3.0ns | 3.0ns |

| flattening type | no | no | torsional | torsional+ nonbonded | torsional | torsional+ nonbonded |

| ♯ of binders | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| ♯ of nonbindes | 248 | NA | NA | 248 | NA | 248 |

Results

Applying flattening potentials on the T4 Lysozyme receptor

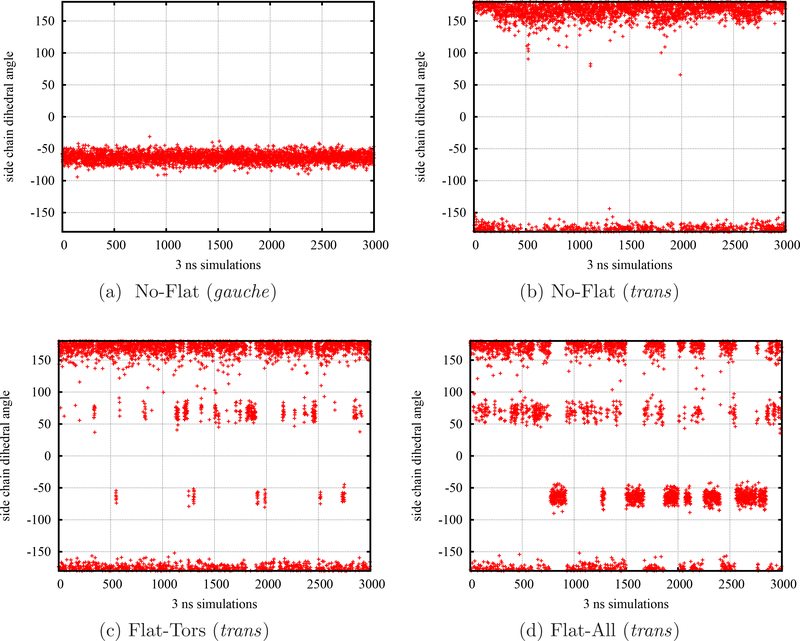

Experimental results73,74 and early simulations47,48,56,75 have confirmed that for the small and medium-sized ligands the N-CA-CB-CG1 dihedral angle of Val111 of the complex (holo) structure of L99A T4 Lysozyme receptor is identical to the ligand-free (apo) conformation (trans, χ1 ≈ 180°). However, in the case of larger ligands such as p-xylene, this sidechain dihedral angle prefers to be in a different state (gauche, χ1 ≈−60° or +60° due to the symmetry) when p-xylene ligand is bound to the binding site in comparison with the isolated conformation state (trans, χ1 ≈ 180°) without the presence of ligand. The intrinsic energy barrier around this χ1 torsional angle could be more than 5 kcal/mol from the studies of potentials of mean force,56,75 which is sufficient to prevent the side chain reorienting for a simulation on the time scale of nanoseconds as displayed in Figs. 3a and 3b from our BEDAM simulations of the p-xylene complex without flattening and started from the gauche and trans states respectively. This inadequate sampling could generate a difference in several kcal/mol in calculated binding free energy when the starting configuration is in the wrong conformation47,48,56,75. To illustrate the efficiency of our flattening simulations, we have performed the BEDAM simulations using different advanced sampling strategies. Figure 3 also shows the time series of sidechain dihedral angle (N-CA-CB-CG1) of Val111 residue in T4 Lysozyme obtained from the SyncRE BEDAM simulations of p-xylene-T4 Lysozyme complex started from the same trans conformation but using two different flattening strategies: 1) REMD with the flattening of all torsional interactions (including 1–4 terms) related to the rotatable bond (*-CA-CB-*) on the sidechain of Val111 (denoted by Flat-Tors); 2) In addition to the selected interactions in 1), the nonbonded interactions such as L-J and Coulomb interactions of all involved atoms in 1) are also flattened (represented by Flat-All). It is obvious that flattening the torsional interactions of the Val111 sidechain (see Fig. 3c) significantly accelerates the transition from the trans to the gauche state. Moreover, the transition can be accelerated further and larger population of gauche state ( χ1 ≈±60° ) appears after flattening all nonbonded interactions from all atoms involved in the flattened dihedral angles (see Fig. 3d). The increased chances to sample the gauche state also shift the resulting binding free energies (as listed in Table 2) to more negative and reasonable values compared to the experiment value and other simulation results using different advanced sampling methods56,75.

Figure 3:

The time series of sidechain dihedral angle (N-CA-CB-CG1) of Val111 of T4 Lysozyme in the complex with p-xylene (at λb = 1). a) normal BEDAM simulation without flattening started from a gauche state (χ1 ≈ −60°); b) normal BEDAM simulation without flattening started from the trans state (χ1 ≈ 180°); c) BEDAM with the flattening of all torsional (including 1–4) interactions on the sidechain related to the CA-CB bond of the Val111 sidechain (started from the trans state); d) In addition to the flattened interactions in c), nonbonded interactions such as L-J and Coulomb interactions from all atoms involved in c) are also flattened (started from the trans state). Note both conformations of χ1 ≈ −60° and +60° belong to the gauche state due to the symmetry of Val111 sidechain. The binding free energies calculated from these four different BEDAM simulations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2:

Binding free energies of p-xylene-T4 Lysozyme calculated from different types of BEDAM simulations.

| Experimental value | No-Flat ( gauche) | No-Flat (trans) | Flat-Tors (trans) | Flat-All (trans) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −4.67a | −5.27±0.08 | −2.55 ±0.020 | −3.02±0.17 | −4.09±0.15 |

Applying flattening potentials on two HIV-IN binders

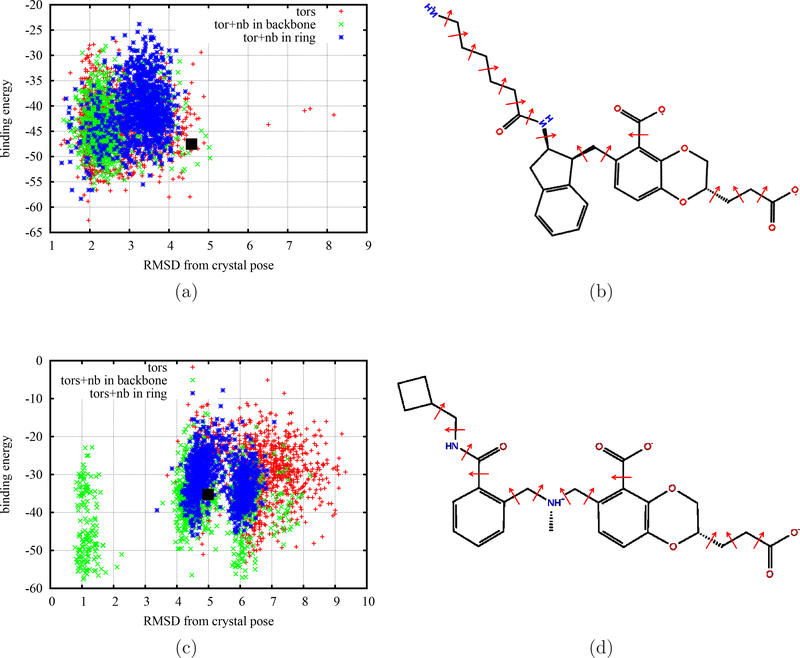

The T4 Lysozyme example above shows the importance of sufficient sampling around the receptor binding site. Another important factor to improve the binding free energy calculation is considering sufficient sampling from the ligand flexibility. Generally when the crystallographic pose of a complex is not available the binding free energy calculation relies on docking programs to generate an initial receptor-ligand complex for starting the simulation. For example, our BEDAM binding free energy calculations for the SAMPL4 Challenge started the simulations from all initial poses prepared by the AutoDock program69. However, many pose predictions of experimental binders have large deviations from their corresponding experimental crystal poses45,47. When the computing time is limited, simulations have no chance to sample sufficiently the ligand internal and external degrees of freedom and adjust to the right poses. To accelerate the sampling of internal degrees of freedom of ligands, we applied the flattening potentials on the ligands. Figure 4 shows the binding energies as a function of ligand RMSDs from the corresponding crystal poses at λb = 1 calculated from the SyncRE BEDAM simulations using different flattening strategies for two HIV-IN binders from the SAMPL4 challenge (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information for the corresponding time series of RMSD). Note that all simulations for both complexes in Fig. 4 have starting poses predicted by the AutoDock program with large RMSD values (> 4.0˚A) from their corresponding crystal poses, inferring that the AutoDock predicted the wrong poses not consistent with the crystal complexes. Similar to T4 Lysozyme, for the first flattening case, the flattened interactions on the ligand only include the torsional interactions from the rotatable backbone bonds (between any two chemical rings or belonging to their large sidechains). For the other two cases, in addition to those torsional interactions from back-bone atoms, we also flattened all nonbonded interactions (L-J and Coulomb) involved in the flattening dihedral angles or from all atoms on the aromatic rings respectively. For the case of avx38747 ligand in Fig. 4a we can see that all three flattening BEDAM simulations converge to correct conformations with low binding energies and small RMSDs (< 2.0 ˚A.) from the initial starting poses with large RMSD values (> 4.0˚A). For the case of avx38788 (Fig. 4c), we find that different flattening strategies have distinct effects. Flattening the torsional interactions as well as all other nonbonded interactions involved for those atoms lead to smaller RMSDs (< 2.0 ˚A.) within the same length of 3.0 ns simulations implying that it is more efficient than the other two flattening strategies.

Figure 4:

The binding energies at λb = 1 (fully coupled state) calculated from the BEDAM simulations with three different flattening strategies as a function of ligand RMSD from the crystal pose for two HIV-IN complexes (a) avx38747 and (c) avx38788 from SAMPL4. (b) and (d) show the corresponding 2D schematic graphs of ligands with the rotatable bonds shown as in red arrows for applying flattening potentials. The black squares show the starting conformations from the AutoDock program.

To exhibit the improvements of sampling of flattening methods Fig. 5 shows the binding energies at λb = 1 as a function of ligand RMSD obtained from the flattening BEDAM simulations of two ligand-HIV-IN complexes as shown in Fig. 4 in comparison with two normal BEDAM simulations without flattening but started from the crystal pose and the docking pose respectively. For the flattening BEDAM simulations, the most efficient case in Fig. 4 is selected, namely, the flattened interactions not only include the torsional interactions from the rotatable back-bone bonds but also include all other nonbonded interactions (LJ and Coulomb) from the corresponding atoms. From Figs. 5a and 5c it is pronounced that both BEDAM simulations without flattening (starting from initial docking poses) keep sampling around the docking conformations with large RMSDs (shown as green points) from the corresponding crystal poses without transition to the small RMSD area (shown as red points) explored by the similar BEDAM simulations started from the crystal poses. In contrast both flattening BEDAM simulations (shown as blue points) start the sampling around the docking conformations and transit to the small RMSD areas around the crystal poses, namely both flattening simulations started from the incorrect docking poses are able to sample distinct conformational regions explored by the individual BEDAM simulations without flattening but started from the crystal poses and the docking poses respectively within the similar simulation length of 3ns for each replica. Due to improvements of sampling on crystal pose regions from the flattening BEDAM simulations, the binding free energies become more negative and closer to that from the simulations started from the crystal poses as shown in Table 3. We should point out that not all simulations can reach the crystal pose as shown in Fig. S2 for the case of avx38787. We will discuss this in more detail below.

Figure 5:

The binding energies at λb = 1 (fully coupled state) obtained from three different types of BEDAM simulations as a function of ligand RMSD from the crystal pose for two HIV-IN complexes avx38747 (a and b) and avx38788 (c and d) from SAMPL4. For (a) and (c), the red points show the 1000 snapshots from the BEDAM simulations without flattening and started from the crystal poses; the green points denote the 1000 snapshots from the similar BEDAM simulations as the red points but started from the docked poses; the blue points display the 1000 snapshots from the flattening BEDAM simulations started from the same docked poses as that of the green points. In (b) and (d), the ligands in red show the crystal poses, those in green exhibit the docking poses predicted by AutoDock, and those in blue display the best poses from the flattening BEDAM simulations that consistent with the corresponding crystal poses.

Table 3:

Binding free energies of two HIV-IN complexes calculated from different types of BEDAM simulations.

| No-Flat | No-Flat | Flat-Tors | Flat-All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| starting pose | crystal pose | docking pose | docking pose | docking pose |

| avx38747 | −6.15±0.20 | −4.27 ±0.14 | −5.86±0.23 | −6.19±0.27 |

| avx38788 | −3.59±0.18 | 3.33±0.13 | 1.35±0.20 | −1.46±0.15 |

Binding free energy and pose predictions for 53 HIV-IN binders from SAMPL4

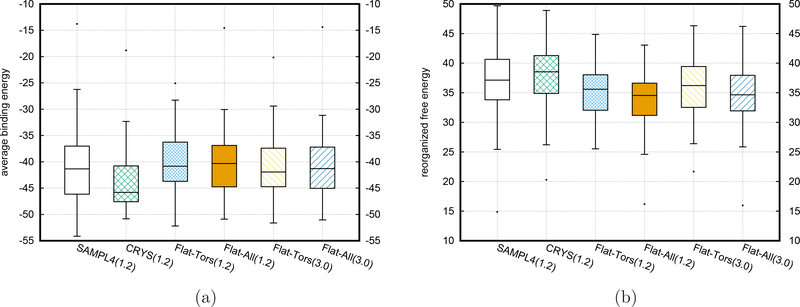

To perform more extensive comparisons, we launched the BEDAM simulations with the flattening features implemented with the AsyncRE scheme for all experimentally confirmed 53 HIV-IN binders from the SAMPL4 challenge using our Temple Grid consisting of around 4000CPUs from the teaching labs and university libraries. Due to the availability of crystal data, we are able to compare the predicted poses from BEDAM simulations with the corresponding crystal poses. However, the experiments can not provide reliable binding affinity data and we only count the number of binders based on crystal structure data for the basic evaluation. Figure 6 shows the statistical boxplots of the BEDAM simulation results for all 53 binders from 4 different kinds of runs: 1) short SyncRE BEDAM simulations (∼1.2ns for each replica, shown in the label of SAMPL4(1.2)) from the original submission to the SAMPL4 challenge and started from the AutoDock predicted poses; 2) short AsyncRE BEDAM simulations (∼1.2ns for each replica, shown in the label of CRYS(1.2)) started from crystal structures; 3) AsyncRE BEDAM simulations (∼3ns for each replica, shown in the label of Flat-Tors(3.0)) with flattening the torsional interactions (including 1–4 terms) of rotatable bonds from backbone atoms and started from the same AutoDock predicted poses in the original SAMPL4 submission; 4) AsyncRE BEDAM simulations (∼3ns for each replica, shown in the label of Flat-All(3.0)) with the additional flattening of all nonbonded interactions on the atoms included in the flattening list in 3). Three different quantities for all 53 experimental binders are displayed in Fig. 6, including the binding free energy as well as the minimum binding energy and the minimum ligand RMSD from the corresponding crystal pose calculated from the trajectory snapshots at λb = 1(full coupled state but without the flattening effects). For a direct comparison at the same simulation length, Fig. 6 also includes the analysis results of flattening simulations ( the 3rd and 4th runs) at the same simulation length of 1.2ns (shown in the labels of Flat-Tors(1.2) and Flat-All(1.2)) as the simulations without flattening (the 1st and 2nd runs).

Figure 6:

The boxplots of the BEDAM simulation results for the SAMPL4 53 experimental binders from different types of runs. a) binding free energies; b) minimum values of binding energies from the trajectory snapshots at λb = 1; c) minimum values of ligand RMSDs from the corresponding crystal poses calculated from the trajectory snapshots at λb = 1. The exact median and mean values are listed in Table 4.

From the binding free energy boxplots as shown in Fig. 6a and the mean and median values as listed in Table 4, we can see that the mean values of the binding free energies from the short AsyncRE BEDAM simulations with flattening (1.2ns per replica) from Temple Grid are decreased by more than 1.5kcal/mol (Flat-Tors(1.2)) and 2.5kcal/mol (Flat-All(1.2)) respectively in comparison with that of the original submission of SAMPL4 with the same simulation length (SAMPL4(1.2)). Due to this drop, The corresponding numbers of predicted true positives are increased to 37 (69.8%) and 41(77.4%) respectively from 28 (52.8%) using the same value of −4.0 kcal/mol as the cutoff for judging binders or nonbinders (namely the free energies of binders have to be lower than −4.0 kcal/mol). These two numbers of predicted true positives are also close to that (44, 83.0%) from the short AsyncRE BEDAM simulations without flattening (CRYS(1.2)) started from the crystal poses. The flattening simulations improve the accuracy of predictions by increasing the number of true positives. From Fig. 6a and Table 4, we also can find two additional interesting results: firstly there is an additional ∼10% increase for the true positives due to the additional drop of ∼ 1.0 kcal/mol in the mean values of binding free energies if we switch on the flattening of all other nonbonded interactions besides the torsional ones; secondly longer flattening simulations (extended to 3.0ns per replica) do not significantly change the numbers of true positives and false negatives, implying a good convergence for most of the flattening BEDAM simulations of 53 binders.

Table 4:

Median, mean values, and number of predicted true positives and false negatives from different BEDAM simulations for 53 experimental binders in the SAMPL4 database

| SAMPL4 | CRYS | FLat-Tors | Flat-All | FLat-Tors | FLat-All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| simulation time | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 3.0ns | 3.0ns |

| BFE median | −4.15 | −6.58 | −5.64 | −6.98 | −4.95 | −5.99 |

| BFE mean | −3.58 | −6.00 | −5.23 | −6.76 | −4.70 | −6.06 |

| Min BE median | −55.52 | −59.50 | −57.32 | −57.45 | −59.34 | −59.54 |

| Min BE mean | −54.66 | −58.05 | −56.88 | −57.19 | −59.13 | −59.02 |

| Min RMSD median | 4.28 | 1.01 | 4.03 | 3.89 | 3.53 | 3.53 |

| Min RMSD mean | 4.24 | 1.06 | 3.81 | 3.62 | 3.31 | 2.97 |

| median | −41.35 | −45.81 | −40.84 | −40.32 | −41.93 | −41.29 |

| mean | −40.77 | −43.49 | −40.35 | −40.48 | −40.82 | −40.96 |

| median | 37.14 | 38.54 | 35.59 | 34.55 | 36.21 | 34.66 |

| mean | 37.19 | 37.49 | 35.11 | 33.72 | 36.12 | 34.90 |

| True Positives | 28(52.8%) | 44(83.0%) | 37(69.8%) | 41(77.4%) | 35(66.1%) | 40(75.5%) |

| False Negatives | 25(47.2%) | 9(17.0%) | 16(30.2%) | 12(22.6%) | 18(33.9%) | 13(24.5%) |

There are similar trends for the minimum binding energies found in the trajectory snapshots at λb = 1 obtained from different kinds of BEDAM simulations as shown in boxplots of Fig. 6b and the mean and median values as listed in Table 4. It is obvious that both flattening simulations (with or without including additional nonbonded flattening) are able to find lower binding energies than the short SyncRE BEDAM simulations without flattening (from the SAMPL4 submission) but started from the same docking poses. This is due to the fact that BEDAM simulations with flattening features are more efficient in exploring the energy landscape, equivalent to more extensive/longer AsyncRE BEDAM simulations. We also note that both the flattening simulations for some ligands can find lower binding energies than the short BEDAM simulations started from the crystal poses. This implies that for some ligands the crystal poses might be not necessary corresponding to the conformations with the minimum binding energies in solution due to the entropy effects.

The advantage of flattening BEDAM in exploring conformational space is also observed from the statistical data of the minimum ligand RMSDs from the corresponding crystal poses calculated from the trajectory snapshots at λb = 1 (see Fig. 6c and Table 4). The mean and median values of the minimum RMSDs from both the flattening simulations are shifted toward that of BEDAM simulations started from the crystal poses, in comparison with the SAMPL4 short BEDAM simulations started from the same docking structures. However, the mean values are still 2 ˚A further from that of short BEDAM simulations started from the crystal poses. These higher RMSD values might have two underlying causes: The first one is the force field effects of 2005 OPLS and AGBNP2 implicit solvent parameters; the other is that all 53 binders in the SAMPL4 database are fairly weak and most of them have affinities more than 200 μM via surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (The SAMPL4 Challenge organizers only provided binding affinities for 8 ligands61). Due to the weakness of the 53 binders, the ligands in solution may exist in multiple poses and the crystal poses are not necessarily the only populated poses in solution. Hence it is not surprising that pose prediction is extremely challenging for weak binders and the best prediction from the 12 submitted results in the 2014 SAMPL4 challenge have the mean value of RMSDs of 4.3 ˚A61. Our flattening simulations have significantly improved the prediction and reduced this value to ∼3 ˚A.

As shown in the Methods Section, the binding free energy calculated from the BEDAM method can be separated into two components: the ligand reorganization free energy mainly representing the free energy cost including both the entropic and enthalpic changes due to adjusting the ligand conformational ensemble in the unbound state to match that of bound state, and denoting the average binding energy in the bound state (λb = 1) without entropic change. Figure 7 shows these decomposed free energies for all 53 experimental binders calculated from different types of BEDAM simulations. From the boxplots of average binding energies at λb = 1 as shown in Fig. 7a and the mean and media values listed in Table 4, it is obvious that for both type of flattening BEDAM simulations started from the docking poses there are only small drops (∼ 1.0 kcal/mol) for the mean values of all 53 cases in comparison with that from the short BEDAM simulations started from the same poses (from the original submission for the SAMPL4 challenge). While the mean values of reorganization free energies from those flattening BEDAM simulations have larger drops (∼2.5 kcal/mol) as displayed in Fig. 7b and Table 4. Namely, the major contribution to the decrease of binding free energies calculated from the flattening BEDAM simulations in Fig. 6a is due to the better estimation of reorganization free energies , which also means that the flattening simulations have smaller representing the free energy cost to reorganize the ligand conformational ensemble in the unbound state to match that of fully bound state. This suggests that the flattening simulations are able to sample the conformational space more extensively and evaluate the entropic and enthalpic changes more accurately, and thereby reduce the artificial conformational strains from the docking predictions.

Figure 7:

The binding free energies in Fig. 6a are decomposed into two parts. a) , average binding energies at λb = 1; b) , reorganization free energies.

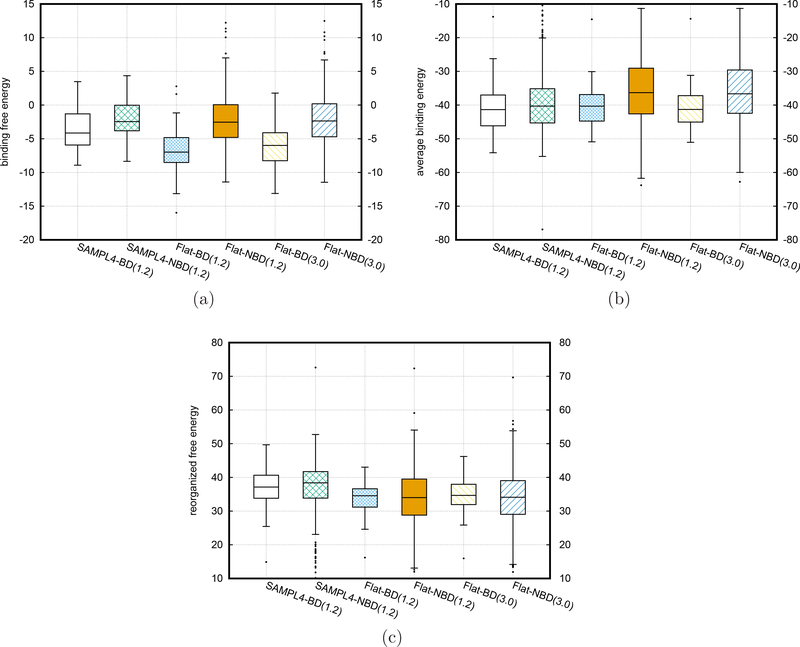

Flattening BEDAM simulations for the whole SAMPL4 database

Encouraged by the improvements from the flattening BEDAM simulations for the 53 binders, we performed the BEDAM simulations with flattening for all the remaining ligands in the SAMPL4 database (248 nonbinders) using the best strategy found from the simulations of the binders (with both the bonded and nonbonded interactions flattened). Figure 8a exhibits the boxplots of the binding free energies calculated from different types of BEDAM simulations for the experimental binders (BD) and the nonbinders (NBD) respectively, and Table 5 lists corresponding median and mean values. We also show the flattening results analyzed from two different trajectory lengths (1.2ns and 3.0ns per replica respectively). There are no significant differences on the boxplots and also the ROC curves below between the results calculated from these two different lengths. This implied convergence of flattening simulations can also be verified further by the high value of Spearman ranking order correlation (∼ 0.98) between the binding free energies calculated at these two different lengths as shown in Fig. S3 of Supporting Information. It is very clear that the boxes including the first quartile and the third quartile from the flattening BEDAM simulations have almost no overlaps between the binders and nonbinders, in contrast to the significant overlap from the simulations for the original SAMPL4 challenge. Furthermore, the differences between the mean (or median) values of binding free energies between the binder and nonbinders become more than doubled when the flattening potentials are turned on. From the boxplots of the binding free energies of nonbinders in Fig. 8a, the mean and median values (listed in Table 5) have no obvious changes after turning on the flattening feature although the distributions became more widely spread. In contrast there are significant drops for the flattening simulations of binders in comparison with that without flattening. Namely the significant reduction of the overlap between the boxplots of the binders and that of nonbinders comes mainly from the decrease of the binding free energies of binders when the flattening feature is included. To further understand the significant improvements from the flattening simulations, we also decomposed the binding free energies into (reorganization free energies) and ( average binding energies at λb = 1) as displayed in Figs. 8c and 8b. Switching on the flattening feature has different effects on the binders and nonbinders. As we discussed in the last Section for binders and also shown in Figs. 8c and 8b and Table 5, the flattening simulations decrease the median (and mean) values of binding free energies by reducing mainly the reorganization free energy penalties with some contribution also from the changes of average binding energies. In contrast flattening simulations have no obvious effects on the median (and mean) values of binding free energies of nonbinders due to two counter effects: The median (and mean ) values of reorganization free energies are reduced, but at the same time the corresponding values of average binding energies are increased by a similar amount∼ 3.5 kcal/mol. The drop of reorganization free energies of nonbinders from flattening simulations occurs for a similar reason as binders, namely the more extensive flattening simulations reduce the artificial conformational strains from the docking predictions and generate more consistent conformational distributions between the unbound and bound state. Moreover, the shifts of the distributions of average binding energies to larger (less attractive) values for the nonbinders as shown in Fig. 8b and Table 5 are also understandable. Since nonbinders tend to escape the binding sites, more extensive sampling methods such as the flattening BEDAM methods will accelerate the escape from the low binding energy poses predicted by the docking program and increase the chances to sampling the correct conformational space corresponding to large binding energies, which is consistent with the shifts of the distributions of average binding energies. The small differences of the mean (and median) values of the reorganization free energies between the binders and nonbinders does not mean that the reorganization free energies do not contribute to the ability to distinguish binders from nonbinders. The binding energies and reorganization free energies for individual ligands are correlated in a way which significantly enhances the discrimination between binders and nonbinders as is clear from comparing Fig. 8a with 8b and 8c and also from the analysis of the AUC values and enrichment statistics which we consider below.

Figure 8:

The boxplots of the BEDAM simulation results for the whole set of SAMPL4 ligand from different types of runs. a) binding free energies ; b) average binding energies at λb = 1; c) reorganization free energies

Table 5:

Median and mean values from different BEDAM simulations for 53 binders (BD) and 248 nonbinders (NBD) in the SAMPL4 database

| SAMPL4-BD | SAMPL4-NBD | Flat-BD | Flat-NBD | Flat-BD | Flat-NBD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| simulation time | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 1.2ns | 3.0ns | 3.0ns |

| BFE median | −4.15 | −2.45 | −6.98 | −2.54 | −5.99 | −2.36 |

| BFE mean | −3.58 | −2.00 | −6.76 | −2.04 | −6.06 | −2.03 |

| median | −41.35 | −40.30 | −40.32 | −36.30 | −41.29 | −36.65 |

| mean | −40.77 | −38.98 | −40.48 | −35.28 | −40.96 | −35.40 |

| median | 37.14 | 38.39 | 34.55 | 33.99 | 34.66 | 34.10 |

| mean | 37.19 | 36.99 | 33.72 | 33.24 | 34.90 | 33.37 |

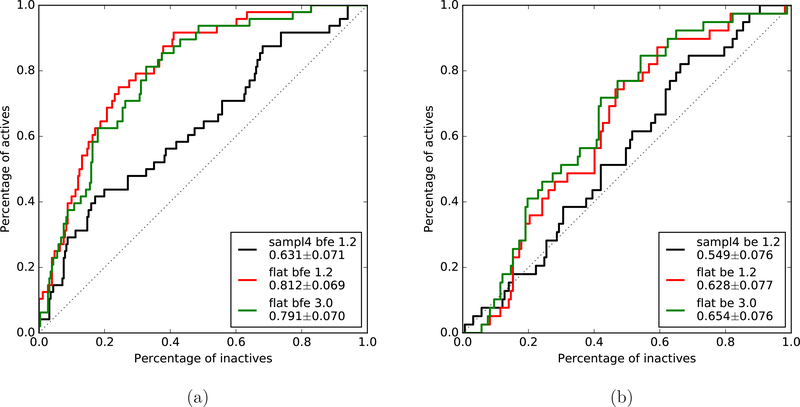

For more quantitative comparisons using the whole database, we also calculated the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for different types of BEDAM simulations as shown in Fig. 9. The area under the curves (AUC) of ROC from the binding free energy predictions (shown in Fig. 9a) are increased to 0.79 and 0.81 for the flattening BEDAM simulations analyzed at 3.0 ns and 1.2 ns respectively from 0.64 of the original SAMPL4 simulations. Note that the AUC values for both flattening BEDAM simulations calculated at different simulation times are almost the same (within the error estimations) but have significant increase (more than 25%) compared with that of simulations without flattening. We also calculated the corresponding ROC curves using the average binding energy predictions as exhibited in Fig. 9b. It is pronounced that all AUC values using average binding energies from all BEDAM simulations are reduced especially for the flattening simulations (at least 18 %) and the distinguishing binders from nonbinders is close to random selection at the top 20% of inactives (nonbinders). Another metric for evaluating the predictions is the enrichment factor as defined in the Methods Section. The calculated enrichment factor at 20% (EF20) cutoff using binding free energy predictions from flattening simulations is 2.61 at 3.0ns with an increase of ∼30% in comparison with 2.01 from the original SAMPL4 submission without flattening. Hence both the AUC values and enrichment factors from the binding free energies calculated from the flattening simulations significantly out-perform the values of the SAMPL4 submissions45,61. The values of EF20 using binding energy predictions for flattening simulations at 3.0ns is 1.42 (deceased almost by half), indicating the importance of reorganization free energies.

Figure 9:

ROC curves of different types of BEDAM simulations for the whole database of SAMPL4 using two different predictions: a) binding free energies and b) average binding energies .

Conclusions

To accelerate the conformational sampling for the intramolecular degrees of freedom of ligands and/or receptors, we have added the flattening feature to our BEDAM method for calculating absolute binding free energies by applying negative potential energies to some selected bonded and nonbonded interactions to reduce high energy barriers. We also implemented this flattening BEDAM method using both the synchronous RE and asynchronous RE schemes.

The advantages of the flattening feature were analyzed using two test systems. For the p-xylene-T4 Lysozyme complex, flattening the intramolecular interactions of a protein sidechain on the binding site accelerated the conformational transition of the sidechain from the the trans to the gauche state when the p-xylene ligand is bound to the binding site. From the extensive flattening BEDAM simulations of 53 experimental binders to HIV integrase from the SAMPL4 database, we demonstrated that turning on the flattening feature not only increases significantly the number of true positives but also improves the prediction accuracy of binding poses. Finally, we also performed flattening BEDAM simulations for the whole SAMPL4 database including both binders and nonbinders. We showed that AUC values of ROC curves and the enrichment factors at 20% cutoff calculated from the flattening BEDAM simulations can be significantly improved in comparison with that of simulations without flattening. We found that this improved ability to distinguish binders from nonbinders is due to the fact that flattening simulations improve the binding free energies of the binders with the major decrease coming from the reorganization free energy penalties to adjust the conformational ensemble distributions of the decoupled states to match that of the full coupled states. In contrast the flattening simulations do not significantly shift the binding free energy distributions of nonbinders due to two counter effects: increasing the average binding energies and decreasing the reorganization free energies. From the ROC curves and enrichment factors, we also notice that including the reorganization free energies significantly improve the predictions for the whole database especially for the top 20% rank of candidates.

It is worth noting that we applied a very general criteria to select the atoms and dihedrals for flattening. However, similar to the REST methods in FEP calculations, there is a tradeoff between the number of degrees freedom selected for flattening and the time to sample all of the relevant space. Including unnecessary internal coordinates for flattening might slow down the convergence in the relevant coordinate space and the large fluctuations of energies can reduce the accuracy36,48. The sampling efficiency and prediction accuracy of flattening BEDAM will need to be further improved by optimizing these selections individually according to the prior knowledge for particular receptors and ligand libraries. To include the degrees of freedom from the receptor flexibility we can perform the cluster analysis of the binding pocket to identify related dihedral angles and atoms using available crystallographic data, results from other MD simulations, or induced- fit studies of docking. In contrast, we can select the degrees of freedom of ligand flexibility using our chemical knowledge and the findings from other studies such as flexible docking which can specify the rotatable dihedral angles to explore the flexibility of ligands. More important the specific interactions created between the receptor and the ligand such as hydrogen bonds and π − π stack interactions will limit the conformational search space and accelerate the sampling convergence.

From our simulations, it appears that the convergence of ligand RMSDs from the 53 binders is slower than the corresponding binding free energies. This might be due the fact that the work described here is focused on the SAMPL4 library of 53 weak binders as suggested by the plasmon resonance experiments and there might exist multiple poses for the same ligand. Additionally and importantly the force field effects also contribute to the errors. For example, we found that the longer simulations (3.0ns) of some binders started from crystal complexes can have larger averaged RMSD s than that of short simulations implying the deviations from crystal poses in long time simulations, which may be related to force field effects.

In this report, we focus on improvements in the ability to distinguish binders from nonbinders using flattening BEDAM simulations. The flattening feature can also improve the rank order predictions of binding affinity crossing several chemical series as we studied for FXR protein-ligand complexes in the D3R 2016 Challenge (to be published). The BEDAM methodology occupies a niche between low resolution docking methods on one hand and high resolution FEP methods in explicit solvent on the other.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF 1665032) and from the National Institutes of Health (GM30580 and U54 GM103368) awarded to R.M.L. REMD simulations were carried out on SuperMIC, Stampede, Comet clusters of XSEDE resources (supported by TG-MCB100145), and BOINC distributed networks at Temple University. This research was also supported in part by the NIH instrumentation grant (S10-OD020095-01) for the cb2rr HPC cluster and the NSF re-search instrumentation grant (1625061) for the owlsnest high performance cluster at Temple University. We thank Emilio Gallicchio for providing the original docking and corresponding BEDAM results for the SAMPL4 Challenge. JX thanks EG for many helpful discussions about the details of the IMPACT and BEDAM codes.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

More information about the system preparations, implementations of SyncRE and Asyn-cRE flattening BEDAM, reweighting analysis, and other related topics are included. This material is available free of charge via the Internet pubs.ac.org.

References

- (1).Gallicchio E; Levy RM Recent Theoretical and Computational Advances for Modeling Protein-Ligand Binding Affinities. Adv. Prot. Chem. Struct. Biol 2011, 85, 27–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chodera JD; Mobley DL; Shirts MR; Dixon RW; Branson K; Pande VS Alchemical Free Energy Methods for Drug Discovery: Progress and Challenges. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2011, 21, 150–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mobley DL; Dill KA Binding of Small-molecule Ligands to Proteins: “What You See” is not Always “What You Get”. Structure 2009, 17, 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jorgensen WL Efficient Drug Lead Discovery and Optimization. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42, 724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gilson MK; Zhou H-X Calculation of Protein-Ligand Binding Affinities. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 2007, 36, 21–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gilson MK; Given JA; Bush BL; McCammon JA The Statistical-Thermodynamic Basis for Computation of Binding Affinities: A Critical Review. Biophys. J 1997, 72, 1047–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Che J; Dzubiella J; Li B; McCammon JA Electrostatic Free Energy and its Variations in Implicit Solvent Models. J Phys Chem B 2008, 112, 3058–3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cosconati S; Forli S; Perryman AL; Harris R; Goodsell DS; Olson AJ Virtual Screening with AutoDock: Theory and Practice. Expert Opin. Drug Discov 2010, 5, 597–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zhou Z; Felts AK; Friesner RA; Levy RM Comparative Performance of Several Flexible Docking Programs and Scoring Functions: Enrichment Studies for a Diverse Set of Pharmaceutically Relevant Targets. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2007, 47, 1599–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).McInnes C Virtual Screening Strategies in Drug Discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2007, 11, 494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Shoichet BK; McGovern SL; Wei B; Irwin JJ Lead Discovery Using Molecular Docking. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2002, 6, 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Sousa SF; Fernandes PA; Ramos MJ Protein-Ligand Docking: Current Status and Future Challenges. Proteins 2006, 65, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gallicchio E; Lapelosa M; Levy RM The Binding Energy Distribution Analysis Method (BEDAM) for the Estimation of Protein-Ligand Binding Affinities. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2010, 6, 2961–2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhou H-X; Gilson MK Theory of Free Energy and Entropy in Noncovalent Binding. Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 4092–4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Woo H-J; Roux B Calculation of Absolute Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy from Computer Simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 6825–6830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mobley DL; Chodera JD; Dill KA On the Use of Orientational Restraints and Symmetry Corrections in Alchemical Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Phys 2006, 125, 084902–084917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Widom B Potential-Distribution Theory and the Statistical Mechanics of Fluids. J. Phys. Chem 1982, 86, 869–872. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Boehr DD; Nussinov R; Wright PE The Role of Dynamic Conformational Ensembles in Biomolecular Recognition. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zwier MC; Chong LT Reaching Biological Timescales with All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 2010, 10, 745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Shaw DE; Maragakis P; Lindorff-Larsen K; Piana S; Dror RO; Eastwood MP; Bank JA; Jumper JM; Salmon JK; Shan Y; Wriggers W Atomic-Level Characterization of the Structural Dynamics of Proteins. Science 2010, 330, 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lane TJ; Shukla D; Beauchamp KA; Pande VS To Milliseconds and Beyond: Challenges in the Simulation of Protein Folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2013, 23, 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bowers KJ; Dror RO; Shaw DE Zonal Methods for the Parallel Execution of Range-Limited N-body Simulations. J. Comput. Phys 2007, 221, 303–329. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bowers K; Chow E; Xu H; Dror R; Eastwood M; Gregersen B; Klepeis J; Kolossv´ary I; Moraes M; Sacerdoti F; Salmon J; Shan Y; Shaw D. Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing (SC06) Tampa, Florida, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Go¨etz AW; Williamson MJ; Xu D; Poole D; Le Grand S; Walker RC Routine Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 1. Generalized Born. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2012, 8, 1542–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Swendsen R; Wang J-S Replica Monte Carlo Simulation of Spin-Glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett 1986, 57, 2607–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hansmann UH Parallel Tempering Algorithm for Conformational Studies of Biological Molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett 1997, 281, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sugita Y; Okamoto Y Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics Method for Protein Folding. Chem. Phys. Lett 1999, 314, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sugita Y; Kitao A; Okamoto Y Multidimensional replica-exchange method for free-energy calculations. J. Chem. Phys 2000, 113, 6042–6051. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kokubo H; Tanaka T; Okamoto Y Ab initio Prediction of Protein-Ligand Binding Structures by Replica-Exchange Umbrella Sampling Simulations. J. Comput. Chem 2011, 32, 2810–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kokubo H; Tanaka T; Okamoto Y Two-Dimensional Replica-Exchange method for Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding Structures. J. Comput. Chem 2013, 34, 2601–2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Mitsutake A; Okamoto Y Replica-Exchange Extensions of Simulated Tempering method. J. Chem. Phys 2004, 121, 2491–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Laio A; Parrinello M Escaping Free-Energy Minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 12562–12566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Fajer M; Hamelberg D; McCammon JA Replica-Exchange Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (REXAMD) Applied to Thermodynamic Integration. J Chem Theory Comput 2008, 4, 1565–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Arrar M; de Oliveira CAF; Fajer M; Sinko W; McCammon JA wREXAMD: A Hamiltonian Replica Exchange Approach to Improve Free Energy Calculations for Systems with Kinetically Trapped Conformations. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2013, 9, 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Liu P; Kim B; Friesner RA; Berne BJ Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering: A Method for Sampling Biological Systems in Explicit Water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102, 13749–13754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wang L; Friesner RA; Berne BJ Replica Exchange with Solute Scaling: A More Efficient Version of Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (REST2). J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 9431–9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Affentranger R; Tavernelli I; Iorio E A Novel Hamiltonian Replica Exchange MD Protocol to Enhance Protein Conformational Space Sampling. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2006, 2, 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Liu P; Voth GA Smart resolution replica exchange: An Efficient Algorithm for Exploring Complex Energy Landscapes. J. Chem. Phys 2007, 126, 045106–045111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zheng L; Chen M; Yang W Random Walk in Orthogonal Space to Achieve Efficient Free-Energy Simulation of Complex Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20227–20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zheng LQ; Chen MG; Yang W Simultaneous Escaping of Explicit and Hidden Free Energy Barriers: Application of the Orthogonal Space Random Walk Strategy in Generalized Ensemble Based Conformational Sampling. J. Chem. Phys 2009, 130, 234105–23414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Fukunishi H; Watanabe O; Takada S On the Hamiltonian Replica Exchange Method for Efficient Sampling of Biomolecular Systems: Application to Protein Structure Prediction. J. Chem. Phys 2002, 116, 9058–9067. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lapelosa M; Gallicchio E; Levy RM Conformational Transitions and Convergence of Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2012, 8, 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gallicchio E; Levy RM Prediction of SAMPL3 Host-Guest Affinities with the Binding Energy Distribution Analysis Method (BEDAM). J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 2012, 26, 505–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Wickstrom L; He P; Gallicchio E; Levy RM Large Scale Affinity Calculations of Cyclodextrin Host-Guest Complexes: Understanding the Role of Reorganization in the Molecular Recognition Process. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2013, 9, 3136–3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Gallicchio E; Deng N; He P; Perryman AL; Santiago DN; Forli S; Olson AJ; Levy RM Virtual Screening of Integrase Inhibitors by Large Scale Binding Free Energy Calculations: the SAMPL4 Challenge. J. Comp. Aided Mol. Des 2014, 28, 475–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Gallicchio E Role of Ligand Reorganization and Conformational Restraints on the Binding Free Energies of DAPY Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors to HIV Reverse Transcriptase. Mol. Biosc 2012, 2, 7–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Mentes A; Deng NJ; Vijayan RSK; Xia J; Gallicchio E; Levy RM Binding Energy Distribution Analysis Method: Hamiltonian Replica Exchange with Torsional Flattening for Binding Mode Prediction and Binding Free Energy Estimation. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2016, 5, 2459–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Wang L; Berne BJ; Friesner RA On Achieving High Accuracy and Reliability in the Calculation of Relative Protein-Ligand Binding Affinities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 1937–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Bussi G; Gervasio FL; Laio A; Parrinello M Free-Energy Landscape for β Hairpin Folding from Combined Parallel Tempering and Metadynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 13435–13441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kannan S; Zacharias M Enhanced Sampling of Peptide and Protein Conformations using Replica Exchange Simulations with a Peptide Backbone Biasing-Potential. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf 2007, 66, 697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Jiang W; Luo Y; Maragliano L; Roux B Calculation of Free Energy Landscape in Multi-Dimensions with Hamiltonian-Exchange Umbrella Sampling on Petascale Supercomputer. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2012, 8, 4672–4680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Banks J et al. Integrated Modeling Program, Applied Chemical Theory (IM-PACT). J. Comp. Chem 2005, 26, 1752–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Sugita Y; Okamoto Y Replica-Exchange Multicanonical Algorithm and Multicanonical Replica-Exchange Method for Simulating Systems with Rough Energy Landscape. Chem. Phys. Lett 2000, 329, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Mitsutake A; Sugita Y; Okamoto Y Generalized-Ensemble Algorithms for Molecular Simulations of Biopolymers. Biopolymers 2001, 60, 96–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Jiang W; Hodoscek M; Roux B Computation of Absolute Hydration and Binding Free Energy with Free Energy Perturbation Distributed Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2009, 5, 2583–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Jiang W; Roux B Free Energy Perturbation Hamiltonian Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (FEP/H-REMD) for Absolute Ligand Binding Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2010, 6, 2559–2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Xia J; Flynn WF; Gallicchio E; Zhang BW; He P; Tan Z; Levy RM Large-Scale Asynchronous and Distributed Multidimensional Replica Exchange Molecular Simulations and Efficiency Analysis. J. Comput. Chem 2015, 36, 1772–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Gallicchio E; Xia J; Flynn WF; Zhang BW; Samlalsingh S; Mentes A; Levy RM Asynchronous Replica Exchange Software for Grid and Heterogeneous Computing. Comput. Phys. Commun 2015, 196, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Forli S; J., O. A. Computational Challenges of Structure-Based Approaches Applied to HIV. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 2015, 389, 31–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]