Abstract

Autoantibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IgG) have been detected in inflammatory demyelinating central nervous system diseases. A 30-year-old woman had blurred vision, marked optic nerve disc swelling, serous retinal detachment at the macular on optic coherence tomography, and MOG-IgG seropositivity. The patient was thought to have optic papillitis associated with MOG-IgG. Her symptoms rapidly improved after high-dose methylprednisolone therapy. We hypothesize that serous retinal detachment was secondary, arising from optic papillitis. This is the first report of the concurrence of optic papillitis with MOG-IgG and serous retinal detachment. MOG-IgG should be tested in patients with marked optic disc swelling.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, optic neuritis, optic papillitis, serous retinal detachment

Introduction

Autoantibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IgG) have been detected in patients with central nervous system demyelinating diseases, including acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, recurrent optic neuritis, and longitudinally transverse myelitis (1, 2). The pathogenic effects of human MOG-IgG have not yet been proven, but MOG is thought to be an important antigen in inflammatory demyelinating diseases (1).

Optic papillitis is a form of optic neuritis localized at the optic nerve head (3). Serous retinal detachment develops when fluid collects in the subretinal space (4). The subretinal space is minimal in the developed eye, but there is no tissue junction across it, so it can reopen under pathological conditions to disrupt the integrity of the blood-retinal barrier (4, 5). Infectious, neoplastic, vascular, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases, such as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, sarcoidosis, and Behçet’s disease, disrupt the blood-retinal barrier, resulting in the development of serous retinal detachment (4, 5). However, to our knowledge, serous retinal detachment in a patient with MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis has not been reported to date.

We herein report a case of optic papillitis associated with MOG-IgG and serous retinal detachment. This case indicates that MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis involves the anterior part of the optic nerve.

Case Report

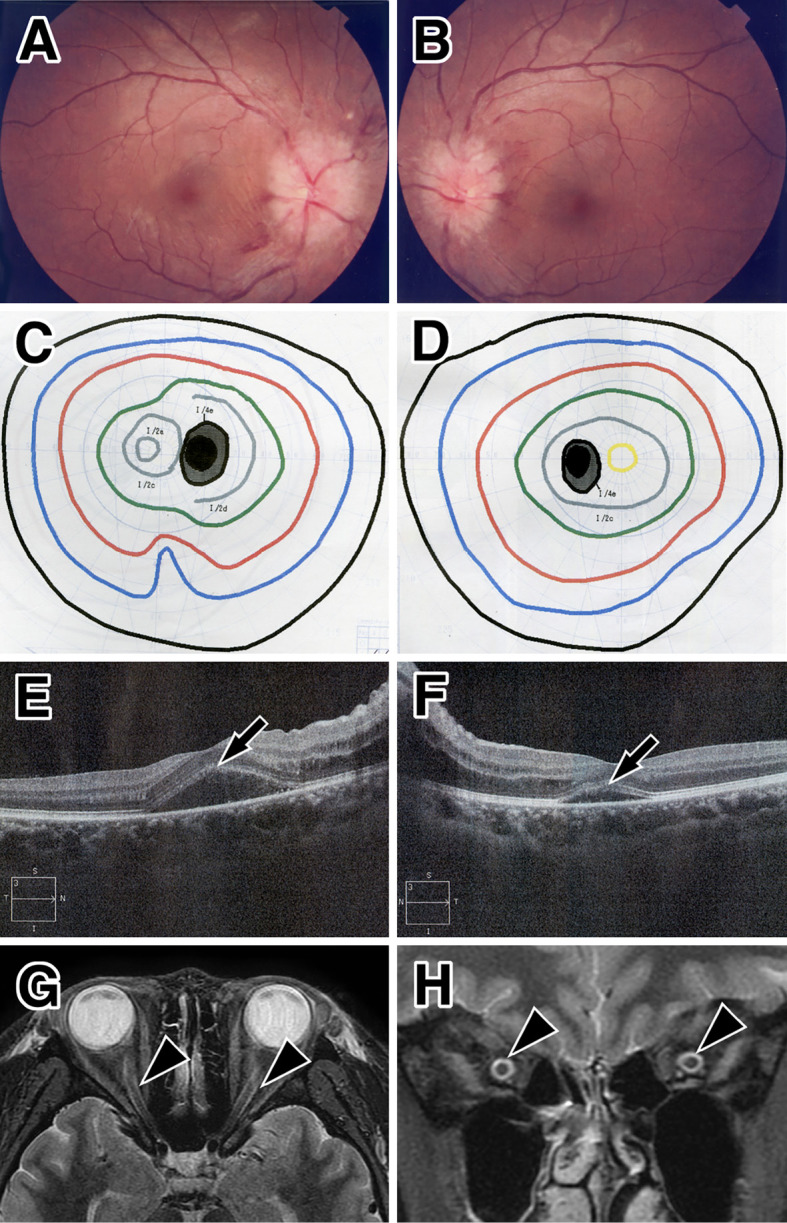

A 30-year-old woman presented with a 1-week history of blurred vision. Her medical history revealed that she had suffered from renal failure due to IgA nephropathy since 22 years of age, when tonsillectomy and high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy were performed. She was not taking any immunotherapy, including steroids, at the presentation, and her IgA nephropathy was in remission. Her visual acuity (VA) was 20/50 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye. Marked optic disc swelling detected by optic fundoscopy (Fig. 1A, B) and mild enlargement of physiological blind spots were observed in both eyes (Fig. 1C, D). The anterior segment and vitreous were normal with no cell infiltration, and her color vision was intact in both eyes. The light reflex was slightly decreased in both eyes.

Figure 1.

Ocular and MRI findings at the initial presentation. Optic fundoscopy shows marked optic disc swelling in both eyes (A: right, B: left). Mild enlargement of the physiological blind spot of the left eye in the visual field test (C: right, D: left). Optical coherence tomography reveals subretinal fluid and serous retinal detachment at the macula of both eyes (arrows, E: right, F: left). Orbital MRI shows high signal (arrowheads) with a short tau inversion recovery sequence in the bilateral optic nerve sheath in the axial (G) and coronal sections (H).

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed mild subretinal fluid in the macula of both eyes, but it was predominant in the right eye (Fig. 1E, F). Fluorescent fundus angiography, flicker test, and visual evoked potentials were not tested. A separate neurological examination, including other cerebral and spinal findings, was normal. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed distortion of the right optic nerve and circumferential high signal intensity at the bilateral optic nerve in short-TI inversion recovery (STIR) sequences (Fig. 1G, H). High signal intensity in the orbital fat was not seen. Gadolinium enhancement was not performed because of her renal failure. No other lesions, including demyelination plaques, tumors, cerebrovascular diseases, or hydrocephalus, were detected by brain or spinal MRI. Screening for infectious diseases (herpes viruses, human immunodeficiency virus, mycoplasma, syphilis, and tuberculosis) and autoimmune diseases (Behçet’s disease, giant cell arteritis, sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, and Crohn disease) was negative. Aquaporin-4-IgG (AQP4-IgG) was also negative according to a cell-based assay.

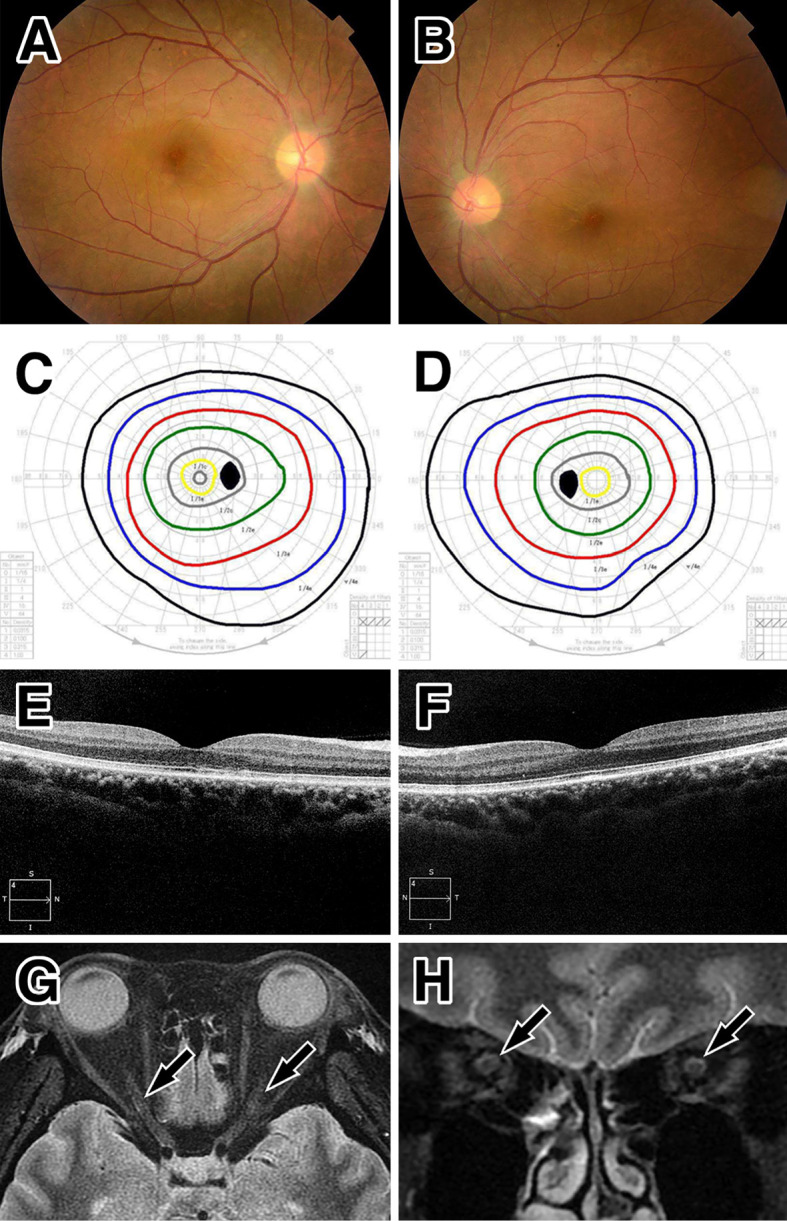

Oral prednisolone was initiated at 60 mg/day and tapered. The patient’s symptoms improved rapidly. Her VA was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/14 in the left eye within 3 weeks, and her bilateral optic disc swelling (Fig. 2A, B), abnormal visual fields (Fig. 2C, D), serous retinal detachment (Fig. 2E, F), and circumferential high signal intensity at the optic nerve on MRI STIR (Fig. 2G, H) were diminished 2 months after treatment.

Figure 2.

Ocular and MRI findings at the first remission. Improvement in the findings of optic disc swelling by optic fundoscopy (A: right, B: left), normal visual field test (C: right, D: left), no subretinal fluid on optical coherence tomography at the macula (E: right, F: left), a reduced high signal intensity (arrows) around the optic nerve on orbital MRI with short tau inversion recovery sequences in the axial (G) and coronal sections (H).

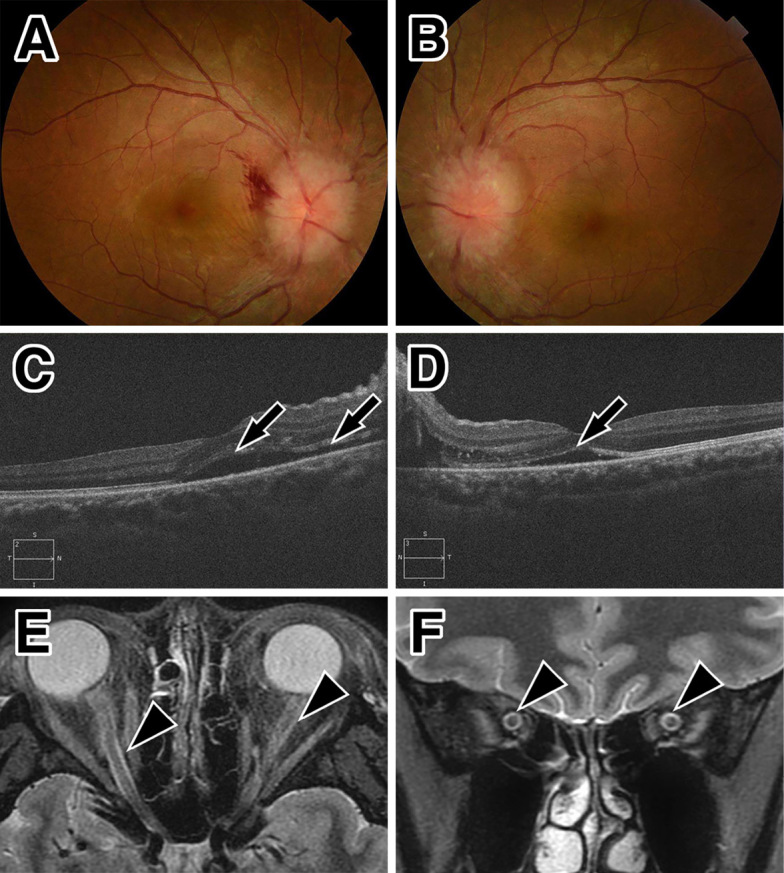

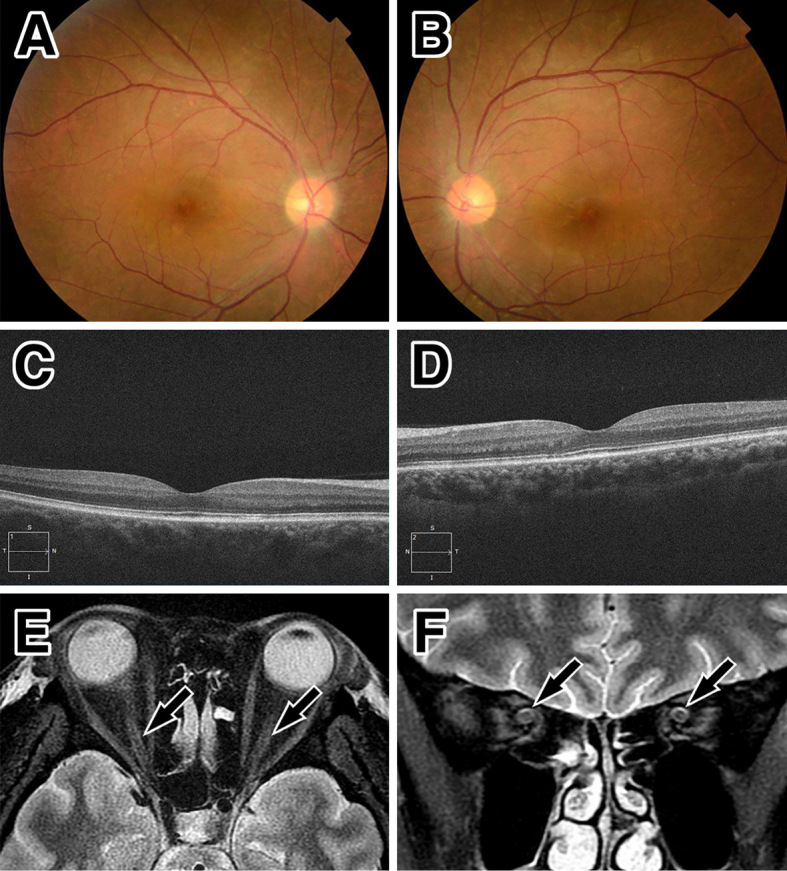

She continued to take minimal doses of prednisolone (3 mg/day), but her symptoms relapsed 16 months after the first symptoms appeared. Her VA became 20/25 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye. Bilateral optic disc swelling (Fig. 3A, B) and retinal bleeding were observed in her right eye (Fig. 3A). OCT revealed mild macular serous retinal detachment in both eyes (Fig. 3C, D). The findings on a reexamination of her cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), including myelin basic protein, were normal, and she was negative for oligoclonal bands. Orbital MRI revealed the reoccurrence of circumferential high intensity on STIR sequences at the bilateral optic nerve (Fig. 3E, F). Serum samples from her first visit and the second attack were positive for MOG-IgG, according to a cell-based assay performed at Tohoku University (antibody titer, 1:512 and 1:256, respectively) (6). She was treated with two courses of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g for 3 days) followed by oral prednisolone (60 mg/day). Her VA improved within 2 weeks, and her disc swelling (Fig. 4A, B), OCT (Fig. 4C, D), and MRI findings (Fig. 4E, F) improved within 10 months. Her MOG-IgG findings returned to negative at one year after the second attack. Prednisolone was tapered gradually but still continued, and no relapse was observed at the 1.5-year follow-up after the second attack.

Figure 3.

Ocular and MRI findings at the second attack. Optic fundoscopy shows marked optic disc swelling in both eyes (A: right, B: left). Retinal bleeding is present in the right eye (A). Optical coherence tomography reveals subretinal fluid and serous retinal detachment at the macula of both eyes (arrows, C: right, D: left). Orbital MRI shows a high signal intensity (arrowheads) with a short tau inversion recovery sequence in the bilateral optic nerve sheath in the axial (E) and coronal sections (F).

Figure 4.

Ocular and MRI findings at the second remission. Improvement in the findings of optic disc swelling by optic fundoscopy (A: right, B: left). No subretinal fluid on optical coherence tomography at the macula (C: right, D: left), and a reduced high signal intensity (arrows) around the optic nerve on orbital MRI with short tau inversion recovery sequences in the axial (E) and coronal sections (F).

Discussion

We encountered a case of MOG-IgG-positive optic papillitis associated with serous retinal detachment. Serous retinal detachment develops when fluid collects in the subretinal space between the photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium, which is the remnant of the embryonic optic vesicle (4).

The subretinal space is small in the developed eye, but it can reopen under pathological conditions (4, 5). The exact mechanisms underlying serous retinal detachment are not well understood, but they may include an increase in choroidal vascular permeability and perfusion as well as destabilization of the retinal epithelium (4, 5). These conditions are associated with blood-retinal barrier breakdown and the subsequent development of serous retinal detachment (4, 5).

The causes of serous retinal detachment are multi-factorial and include infectious, neoplastic, vascular, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases, such as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, sarcoidosis, and Behçet’s disease. To our knowledge, the concurrence of serous retinal detachment and optic neuritis has not been reported. Our patient’s findings were not compatible with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, sarcoidosis, or Behçet’s disease. Radiological investigations have revealed the involvement of the anterior part of the optic nerve in patients with optic neuritis and MOG-IgG (1, 7). Perineural enhancement of the optic nerve, i.e. enhancement extending to the soft tissue around the optic nerve, has been reported as a characteristic finding of MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis (8). We hypothesize that inflammation of the optic nerve head extended to the tissues around the optic nerve head and induced secondary serous retinal detachment in the present case. However, the serous retinal detachment appeared to be localized and had not spread into the optic nerve head from the macula. Therefore, the precise mechanism involved in the present case remains unknown. The accumulation of similar cases or experimental findings will help clarify the mechanisms underlying serous retinal detachment and optic papillitis.

Optic papillitis is a type of optic neuritis with inflammation at the optic nerve head characterized by optic disc swelling (3). Recent studies have shown that patients with optic neuritis with MOG-IgG are more likely to develop optic disc swelling than those with AQP4-IgG (1, 9, 10). These findings suggest that patients with optic neuritis with MOG-IgG are more likely to develop inflammation at the head of the optic nerve than patients with optic neuritis with AQP4-IgG. The cause of the impaired visual acuity in the present case appeared to be optic papillitis rather than serous retinal detachment based on the effects of steroid therapy. The present findings suggest that MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis may underlie the inflammation at the anterior part of the optic nerve.

Circumferential optic nerve sheath enhancement on MRI (“tram-track” and “donut” signs) are characteristic of optic perineuritis (11, 12). Unfortunately, tram-track enhancement could not be confirmed in our patient because of her renal failure. However, circumferential high signal intensity on STIR sequences was seen. The STIR technique suppresses the bright signal of orbital fat and detects edematous lesions of acute phase optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis (MS) (13, 14). Our case could not be diagnosed with optic perineuritis because of a lack of the characteristic enhancement data. Abnormal signal intensity around the optic nerve sheath is also seen in conditions with increased intracranial pressure (i.e. brain tumors, hydrocephalus, cerebrovascular diseases, and other space occupying lesions), reflecting the distention of the cerebrospinal fluid in the perioptic subarachnoid space (15). However, the present patient’s symptoms did not correspond to any of these conditions, given her examination and radiological findings. Liugan et al. reported that free communication through the sub-arachnoid space between the intracranial cavity and optic nerve sheath in humans is very limited due to the presence of anatomical barriers in the optic canal. They further suggested that the sub-arachnoid space in the optic nerve sheath might be compartmented (16). A high signal intensity in the optic nerve sheath on STIR sequences was also reported in a case of idiopathic optic neuritis (17). These findings suggest that the local congestion of cerebrospinal fluid in the sub-arachnoid space occurs in the optic nerve during optic neuritis. We hypothesize that the high STIR signal in the surrounding optic nerve in our case indicated cerebrospinal fluid congestion because of optic neuritis associated with MOG-IgG.

This patient is the first reported case with a comorbidity of IgA nephropathy with optic neuritis or MOG-IgG-associated diseases. There have been reports of IgA nephropathy associated with inflammatory eye diseases, including episcleritis (18), scleritis (19), and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (20). One mechanism by which IgA nephropathy might develop in these settings involves abnormal immune reactions in the eyes (19). A background abnormal immune condition may trigger the development of IgA nephropathy, optic neuritis, and MOG-IgG-associated diseases.

A limitation of this study is that it only contained a single patient. Therefore, it may be premature to discuss the association between serous retinal detachment and MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis. Further investigations are needed to confirm this association.

In conclusion, we herein report the first case of MOG-IgG-positive optic papillitis with serous retinal detachment. Our findings highlight the involvement of the anterior part of the optic nerve in MOG-IgG-positive optic neuritis.

Author's disclosure of potential Conflicts of Interest (COI).

Ichiro Nakashima: Reseach funding, LSI Medience Corporation and Cosmic Corporation.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Dr. Tomomi Kimura from the Department of Ophthalmology, Aomori Prefectural Central Hospital, for her ophthalmological evaluation.

References

- 1. Ramanathan S, Dale RC, Brilot F. Anti-MOG antibody: the history, clinical phenotype, and pathogenicity of a serum biomarker for demyelination. Autoimmun Rev 15: 307-324, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zamvil SS, Slavin AJ. Does MOG Ig-positive AQP4-seronegative opticospinal inflammatory disease justify a diagnosis of NMO spectrum disorder? Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2: e62, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kanski J. Clinical opthalmology: a systemic approach. 3rd ed. Butterworth-Heinemann, London, 1994: 457-464. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amer R, Nalci H, Yalcindag N. Exudative retinal detachment. Surv Ophthalmol 62: 723-769, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marmor MF. Control of subretinal fluid: experimental and clinical studies. Eye (Lond) 4: 340-344, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato DK, Callegaro D, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 82: 474-481, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biotti D, Bonneville F, Tournaire E, et al. Optic neuritis in patients with anti-MOG antibodies spectrum disorder: MRI and clinical features from a large multicentric cohort in France. J Neurol 264: 2173-2175, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim SM, Woodhall MR, Kim JS, et al. Antibodies to MOG in adults with inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2: e163, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akaishi T, Konno M, Nakashima I, Aoki M. Intractable hiccup in demyelinating disease with anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody. Intern Med 55: 2905-2906, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stiebel-Kalish H, Lotan I, Brody J, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer may be better preserved in MOG-IgG versus AQP4-IgG optic neuritis: a cohort study. PLoS One 12: e0170847, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hickman SJ. Optic perineuritis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 16: 16, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Purvin V, Kawasaki A, Jacobson DM. Optic perineuritis: clinical and radiographic features. Arch Ophthalmol 119: 1299-1306, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson G, Miller DH, MacManus D, et al. STIR sequences in NMR imaging of the optic nerve. Neuroradiology 29: 238-245, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson FP, Miller WG. Fiber optic immunochemical sensor for continuous, reversible measurement of phenytoin. Clin Chem 34: 1417-1421, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gass A, Barker GJ, Riordan-Eva P, et al. MRI of the optic nerve in benign intracranial hypertension. Neuroradiology 38: 769-773, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liugan M, Xu Z, Zhang M. Reduced free communication of the subarachnoid space within the optic canal in the human. Am J Ophthalmol 179: 25-31, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Killer HE, Mironov A, Flammer J. Optic neuritis with marked distension of the optic nerve sheath due to local fluid congestion. Br J Ophthalmol 87: 249, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bene MC, Hurault de Ligny B, Sirbat D, Faure G, Kessler M, Duheille J. IgA nephropathy: dimeric IgA-secreting cells are present in episcleral infiltrate. Am J Clin Pathol 82: 608-611, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nomoto Y, Sakai H, Endoh M, Tomino Y. Scleritis and IgA nephropathy. Arch Intern Med 140: 783-785, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuo T, Masuda I, Ota K, Yamadori I, Sunami R, Nose S. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome in two patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Acta Med Okayama 61: 305-309, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]