Abstract

Supported nanoparticles are broadly employed in industrial catalytic processes, where the active sites can be tuned by metal-support interactions (MSIs). Although it is well accepted that supports can modify the chemistry of metal nanoparticles, systematic utilization of MSIs for achieving desired catalytic performance is still challenging. The developments of supports with appropriate chemical properties and identification of the resulting active sites are the main barriers. Here, we develop two-dimensional transition metal carbides (MXenes) supported platinum as efficient catalysts for light alkane dehydrogenations. Ordered Pt3Ti and surface Pt3Nb intermetallic compound nanoparticles are formed via reactive metal-support interactions on Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx catalysts, respectively. MXene supports modulate the nature of the active sites, making them highly selective toward C–H activation. Such exploitation of the MSIs makes MXenes promising platforms with versatile chemical reactivity and tunability for facile design of supported intermetallic nanoparticles over a wide range of compositions and structures.

The performance of supported metal nanoparticle catalysts can be tailored by metal-support interactions, but their use in catalyst design is still challenging. Here, the authors develop two-dimensional transition metal carbides as platforms for designing intermetallic compound catalysts that are efficient for light alkane dehydrogenations.

Introduction

Metal nanoparticles (NPs) are widely used as heterogeneous catalysts and in electrochemical applications1–3. The performance of the supported metal NPs, including the rate, selectivity and stability, can be tailored by controlling their interactions with the supports4–7. These metal-support interactions (MSIs) have been found to modify the geometric and electronic structures of active sites8,9, and, not surprisingly, the chemical properties of the supports are crucial to the modifications10. Nonetheless, rational design of supported catalysts through MSIs is often arduous, especially when the supports undergo structural changes under reaction conditions11. A classic example is the encapsulation of metal active sites by reducible oxide-support overlayers, which was designated by Tauster et al.12 as the strong-metal support interaction (SMSI) in 1978. In the SMSI state the active metal sites on the NPs are covered due to the migration of suboxide species, which renders the loss of adsorption capability of the NPs12,13. Supports with ideal chemical tunability and reactivity are clearly a key to harnessing the potential promotional effects of MSIs on supported metal NP catalysts, but their development remains a grand challenge.

Two-dimensional (2D) early transition metal carbides, i.e., MXenes, is a burgeoning class of materials with well-defined structures and widely tunable compositions14. They have a formula of Mn+1XnTx, where M is an early transition metal, X refers to carbon and/or nitrogen, and T stands for surface functional groups15. We have recently shown that MXenes are promising supports for nanoparticle (NPs) catalysts and that the presence of noble metal NPs promotes both the removal of surface functional groups and reduction of the M component of the MXene16. Reduction of these catalyst supports can lead to targeted delivery of the metal components in the supports to the NPs that contact the support surface. As a result, formation of ordered intermetallic compounds (IMCs) through reactive metal-support interactions (RMSIs) is possible17. RMSI refers to a chemical reaction between a metal and the support that induces the formation of bimetallic structures, which is differentiated from the more general SMSI because it is driven by the high thermodynamic stability of the resulting IMCs. MXenes can facilitate this process by having 2D structures with metal carbon bonds (M–C) that are weaker compared to the metal oxygen bonds (M–O) in typical oxide supports. This enhanced chemical reactivity can allow RMSIs to occur at lower temperature and, thus, favor the control of particle size, in contrast to the high temperature reduction required for early transition metal oxides or bulk carbides18–20. On MXenes IMCs may be formed that are not possible on traditional oxide and carbide supports and their properties controlled through in situ reduction at moderate temperature.

Here, we report two examples of thermally stable intermetallic NP catalysts prepared via RMSI between platinum and MXenes. A complete, full Pt3Ti IMC with Cu3Au type structure is formed in Pt/Ti3C2Tx catalysts. For Pt/Nb2CTx catalysts, NPs with a surface Pt3Nb IMC in the same structure are formed, presumably via a process kinetically controlled by the diffusion of Nb species. These intermetallic structures have not been previously reported for Pt NPs catalysts supported by oxides and bulk carbides of Ti and Nb. The strong intermetallic bonds in these structures offer compositional and electronic modification of the actives sites. The result, in this case is that the catalysts become highly selective for light alkane dehydrogenation (LADH), a reaction in renewed interest due to shale gas boom21. Such reactive interaction is generally applicable between platinum NPs and MXene families. The Pt-M (M refers to early transition metals) IMCs are famous for their thermal stability with high enthalpy of formation, but their preparation through co-reduction is challenging as early transition metals are oxyphilic22,23. Thus, MXenes pave an avenue for facile design of Pt-M NPs with a broad range of compositions and structures that are intractable to synthesize by traditional methods.

Results

Two-dimensionality of the MXene supports

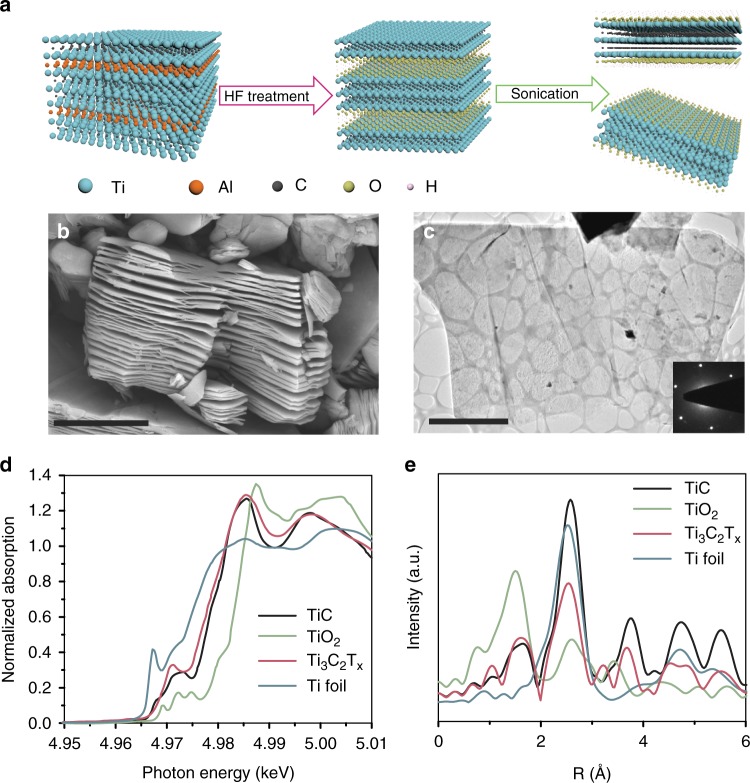

The two MXene supports, Ti3C2Tx and Nb2CTx, were prepared by a chemical exfoliation process reported by the literature14,24. Briefly, Ti3AlC2 and Nb2AlC compounds (MAX) were treated with HF to extract the aluminum layers and exfoliate the 2D early transition metal carbides (Fig. 1a). In the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Supplementary Figs. 1a, b), the shift of (002) peaks and the disappearance of the most intense nonbasal plane diffraction peaks of the MAX phases at 2θ ≈ 39° indicate that the MAX phases are converted to MXenes with increased c lattice parameters after the HF exfoliation. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1c) display the typical accordion-like morphology of MXenes that suggests the exfoliation of individual grains along the basal planes. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH) were employed as intercalants to delaminate Ti3AlC2 and Nb2CTx MXenes, respectively25,26. With the help of sonication, thin layers of MXenes nanosheets that are electron transparent can be obtained (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of Ti3C2Tx MXene support. a Schematic of Ti3C2Tx MXene preparation. b SEM image of Ti3C2Tx MXene, the scale bar corresponds to 3 µm. c TEM image of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets. Inset represents the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern showing hexagonal basal plane symmetry of Ti3C2Tx MXene. The scale bar corresponds to 2 µm. d XANES spectra of the Ti3C2Tx compared to references including Ti metal foil, TiO2 and TiC. e Magnitude of the Fourier transform of the k2 weighted EXAFS of the Ti3C2Tx compared to bulk TiC

The chemical nature of the MXenes was investigated by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Figure 1d shows that the Ti K edge X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) spectrum of Ti3C2Tx has similar shape compared to that of bulk TiC rather than that of Ti foil or TiO2. The edge energy of Ti3C2Tx (4967.2 eV) is close to that of TiC (4967.1 eV), which is between the energies of Ti foil (4966.4 eV) and TiO2 (4968.6 eV), indicating its carbide nature. The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra (Fig. 1e) compare the local coordination of the Ti atoms in the Ti3C2Tx MXene to its bulk counterpart (TiC). Ti3C2Tx shows first-shell scattering (Ti-C/O/F) similar to that of TiC but with second-shell scattering (Ti-C-Ti) lower than that of TiC, consistent with the reduced dimensionality of the Ti3C2Tx MXene and corresponding high portion of surface Ti atoms. Similar results were obtained for Nb2CTx by Nb K edge XAS in our previous work16.

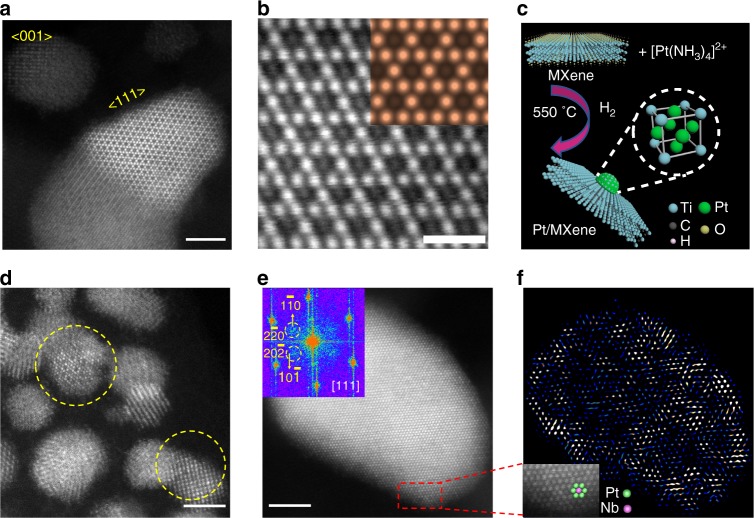

Characterizations of MXenes supported nanoparticles

Pt was loaded on the two MXene supports via incipient-wetness impregnation (IWI) as reported previously16. The Pt/MXene catalysts were further reduced with 5% H2/N2 at 550 °C, which is within the typical temperature range of LADH reactions27. High angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) shows that small NPs form on both catalysts. The average particle diameters are about 6 ± 3.2 nm and 2.6 ± 0.7 nm for Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx catalysts, respectively. The MXene supports enable dispersion of NPs without apparent agglomeration (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3).

The compositions of the NPs were first investigated by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping. The signals of Pt and Ti or Nb overlap over all the NPs (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5), suggesting migrations of M to the Pt NPs. Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM was utilized to further characterize the structures of Pt-Ti and Pt-Nb NPs. Figure 2a shows an image representative of the NPs supported by Ti3C2Tx MXene. The NP in the center of the figure is viewed along the [111] zone axis, whereas another NP in the upper left corner is viewed along the [001] zone axis. Two different types of atoms can be clearly differentiated due to the Z-contrast in high angle annular dark field (HAADF) imaging. The bright dots are characteristic of heavier Pt atoms, while the dimmer ones correspond to Ti. Along the [111] axis of a NP, the projected unit cells are composed of periodic hexagonal arrays of Pt atoms that surround Ti atoms at the center of the hexagons (Fig. 2b), which indicates a specific L12 type symmetry and is consistent with formation of the Cu3Au type Pt3Ti IMC (Fig. 2c)22. The experimental HAADF-STEM image shows good agreement with the simulated (111) surface of L12 ordered Pt3Ti nanostructures (inset of Fig. 2b). The Pt/Ti ratio is estimated by EDS elemental mapping on a NP hanging over the vacuum to avoid the Ti signals from the Ti3C2Tx MXene support and give a value of the molar ratio of Pt to Ti equal to 3.55 (Supplementary Fig. 6), which is close to the theoretical ratio of Pt3Ti alloy within error.

Fig. 2.

Microscopy characterizations of 1% Pt/MXene catalysts. a Representative HAADF-STEM image of 1% Pt/Ti3C2Tx catalyst. b (111) surface of Pt3Ti NP. Inset is a simulated STEM image of Pt3Ti (111) surface. The simulated image is in good agreement with the experimental result. c Schematic illustration of RMSI in Pt/MXene catalysts and the structure of L12-ordered intermetallic Pt3Ti. d Representative HAADF-STEM image of 1% Pt/Nb2CTx catalyst. e A Pt-Nb NP viewed along [111], inset is the FFT pattern of the NP. f IFFT pattern of the NP in Fig. 2e, inset is an enlarged image showing the super lattice of the NP. Scale bars: a, d, e 2 nm, and b 500 pm

The ordered intermetallic structure of Pt-Nb NPs can also be directly observed (circled with dash lines) despite the small particle sizes (2.6 ± 0.7 nm) (Fig. 2d). The fcc structure is identified by two NPs viewed along [111] and [001] axis, respectively (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 7). The inset of Fig. 2e shows the fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern of the NP viewed along [111] zone, where the signals of () and () supper-lattice are present. Since the unique super periods are present only in the structurally ordered intermetallic phase and are absent in the disordered alloy phase, ordering in the NP is confirmed. Moreover, the enlarged image of the NP (inset of Fig. 2f) shows a dimmer Nb atom surrounded by six Pt atoms in a hexagonal pattern, again implying a local L12 ordering. The intermetallic phase, however, does not form over the whole NP. The distribution of the Pt-Nb intermetallic order in the NP is demonstrated by the contrast variation of the inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) image in Fig. 2f. The IFFT pattern shows that the ordered Pt-Nb phase preferentially populates the edge of the NP versus the inner core. This is consistent with previous studies reporting that the diffusion of the second metallic species into the noble metal lattice (from the NP surface) played a pivotal role in the formations of intermetallic NPs28–30.

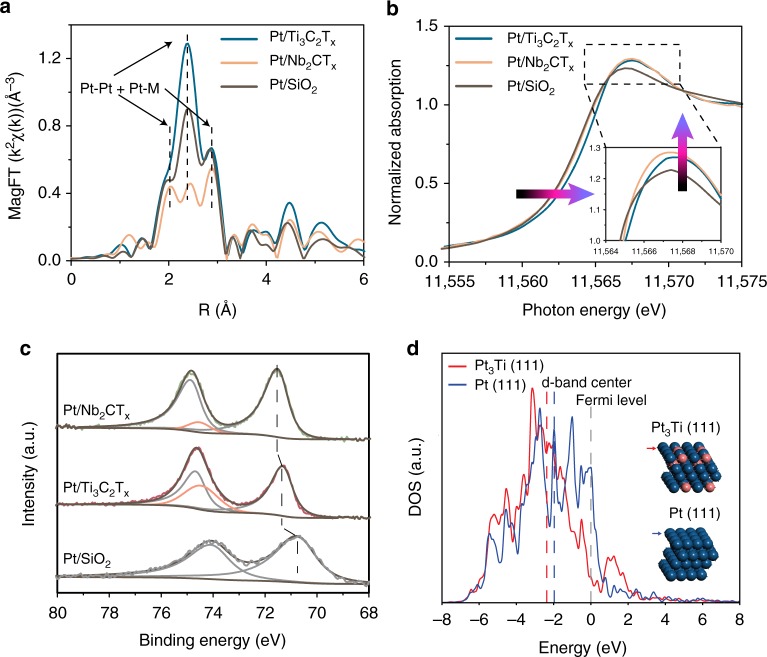

To investigate the altered Pt chemical environment resulting from the RMSI between Pt and MXenes, the Pt/MXene catalysts were studied by in situ XAS. A Pt/SiO2 catalyst with an average particle size of 1.8 ± 0.6 nm was also prepared as a reference (Supplementary Fig. 8). The EXAFS spectra of both in situ reduced catalysts (Fig. 3a) show metal-metal scattering significantly different from the typical three-peak pattern characteristic of monometallic Pt NPs on SiO2. For Pt/Ti3C2Tx, the central peak of the magnitude of Fourier transform EXAFS has a higher intensity due to the in-phase constructive interference between Pt-Ti and Pt-Pt scattering, while the opposite is observed on Pt/Nb2CTx because Pt-Nb and Pt-Pt are out-of-phase. Quantitative fitting (Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Table 1) of the EXAFS gives the following average coordination numbers (CNs) and bond distances: 6.6 Pt-Pt bond and 3.4 Pt-Ti bond both at 2.75 Å for the Pt/Ti3C2Tx catalyst and 6.7 Pt-Pt bond at 2.77 Å and 1.8 Pt-Nb bond at 2.75 Å for the Pt/Nb2CTx catalyst. The EXAFS of both catalysts confirms the presence of bimetallic NPs. For an ideal bulk L12 type Pt3M intermetallic structure, the bond distances are the same for the Pt-Pt and Pt-M paths and the ratio of Pt-Pt CN over Pt-M CN is 2. Thus, the XAS results for Pt/Ti3C2Tx indicate the formation of L12 type Pt3M structures, which is concordant with those of STEM. For the Pt/Nb2CTx, the Pt-Pt/Pt-Nb CN ratio is much greater than 2 and their bond distances are slightly different, consistent with formation of partial/surface L12 ordering in the Pt-Nb NPs as observed by STEM. Together the HAADF-STEM and EXAFS indicate that RMSI occurs in these two MXene supported catalysts, leading to formations of IMCs with tunable compositions and structures. We note for comparison that Pt added similarly to bulk titanium carbide or niobium carbide surfaces did not produce IMCs (Supplementary Figs. 10, 11).

Fig. 3.

In situ Spectroscopy characterization of Pt/MXenes catalysts. a Magnitude of the Fourier Transform of the k2 weighted Pt LIII edge in situ EXAFS of the Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx catalyst after reduction at 550 °C in H2 compared to Pt/SiO2. b The Pt LIII edge in situ XANES spectra of the Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx catalyst after reduction at 550 °C in H2 compared to Pt/SiO2. c XPS spectra of Pt/Ti3C2Tx, Pt/Nb2CTx and Pt/SiO2 reduced at 550 °C by H2 in a spectrometer side chamber and not exposed to air. d DFT calculated projected density of states (DOS) for the 5d orbitals of Pt in the top-layer Pt3Ti (111) and Pt (111)

Electronic structures of Pt/MXene catalysts

In situ XANES at Pt LIII edge was conducted on the reduced catalysts to examine the energy of the unoccupied d states (Fig. 3b). The XANES energies of the Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx catalysts are 11564.6 eV and 11564.3 eV, respectively, both higher compared to that of monometallic Pt (11564.0 eV). The whitelines are slightly taller and narrower compared to that of Pt/SiO2, corresponding to a change in the energy distribution of the 5d unoccupied states. Shifts in electronic band energy level were also detected by XPS (in situ reduced samples). In Fig. 3c, the Pt 4f7/2 binding energies of Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx are 71.3 eV and 71.6 eV respectively, which shift to higher values with respect to that of monometallic Pt (70.8 eV). These spectroscopic studies of fully reduced samples indicate that the formation of Pt3M intermetallic NPs leads to altered electronic structure of the Pt atoms and that the 5d states are shifted to higher energy in Pt/MXenes compared to Pt/SiO2.

To better understand the modulated electronic structures of the Pt/MXene catalysts owing to the formations of IMCs, we carried out density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the projected density of states (DOS). Out of the two Pt/MXene catalysts, the Pt/Ti3C2Tx catalyst contains full (instead of partial) IMC NPs with the exposure of representative (111) surface planes resolved by aberration-corrected STEM. Therefore, we employed slab models of Pt3Ti(111) and Pt(111) surfaces for comparison. As shown in Fig. 3d, the d band center of Pt(111) is located at −1.97 eV relative to the Fermi level, whereas that of Pt3Ti(111) downshifts to −2.37 eV due to a strong Pt-Ti d-d orbital coupling. Similar shifts of d band center to a lower level were also reported in other Pt-M systems, where M is Co, Fe, Ni, Ce31. Additionally, ~1 eV above the Fermi level, the DOS calculation also shows an increased intensity for Pt3Ti(111) (Fig. 3d) compared to Pt(111), which is consistent with the in situ XANES results showing higher energy and intensity of the whiteline of the Pt/Ti3C2Tx catalyst compared to Pt/SiO2. A recent study combining DFT calculations and an emerging technique, in situ resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS), reported that formation of IMCs leads to a downward shift of the d band center as well as an upward shift of the energy of the unoccupied 5d states32, which agrees with our results.

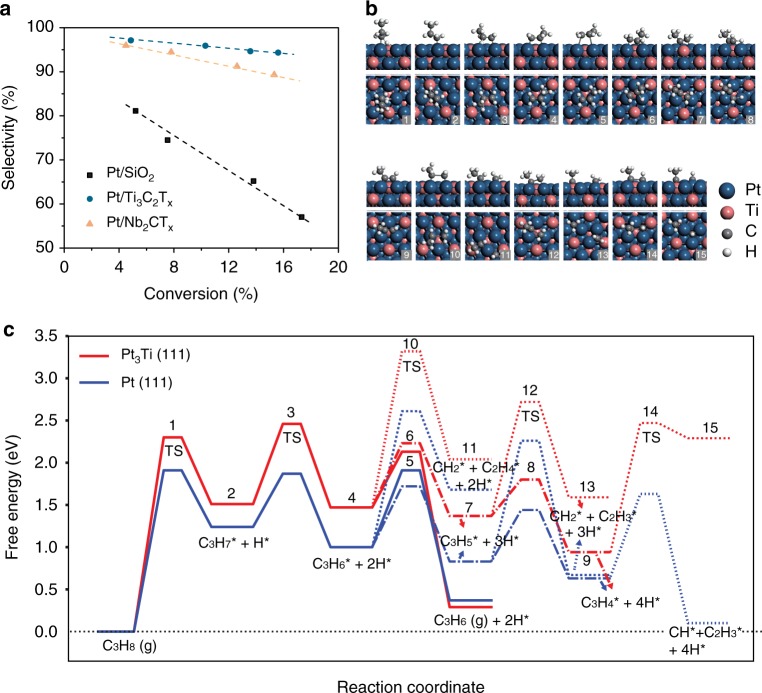

Catalytic performance and free energy calculations

According to d band chemisorption theory, shifts to lower energy of d band center will reduce the surface adsorption reactivity33 and directly affect the chemistry of catalysts34. LADH reactions are sensitive to the energy level of d band electrons of the catalysts surface21, thus were used as probes to evaluate effects of the in situ formation of Pt3M intermetallic NPs on the catalytic performance. All the catalysts were pretreated and tested under the same conditions summarized in Methods. The product selectivity of different catalysts was compared between 0 and 20% light alkane conversions. For both dehydrogenation of propane (Fig. 4a) and isobutane (Supplementary Fig. 12), Pt/MXene catalysts are much more selective than Pt/SiO2 at the same conversion. For example, when the conversion of propane is 15%, Pt/SiO2 is 60% selective to propylene, while those of Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx are ~95% and ~90%, respectively (Fig. 4a). Though intermetallic catalysts have larger particle size compared to the reference monometallic Pt catalyst, the improvement in their catalytic performance can be attributed to the formation of intermetallic structure rather than a size effect since larger particles have been reported to give lower selectivity35,36. For all the catalysts, the selectivity of dehydrogenation is lower at higher conversion due to the hydrogenolysis side reaction that requires hydrogen. The decrease in selectivity under increasing conversion is reduced on the Pt/Ti3C2Tx and Pt/Nb2CTx catalysts, indicating that the effect of side reactions is less prominent on the intermetallic NPs. The TORs were calculated using the reaction rate per gram of Pt measured under differential conditions and catalyst dispersion estimated from the average particles sizes. For propane dehydrogenation (PDH), the TORs were 0.12 s−1, 0.09 s−1 and 0.08 s−1 for Pt/SiO2, Pt/Nb2CTx and Pt/Ti3C2Tx, respectively. The TORs for isobutane dehydrogenation followed a similar trend and were 0.09 s−1, 0.06 s−1 and 0.06 s−1 for Pt/SiO2, Pt/Nb2CTx and Pt/Ti3C2Tx. These values are similar to the TORs reported for typical LADH catalysts21. The evolution of performance with time on-stream for IMC catalysts are also consistent with the monometallic Pt catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 13) as well as previous literature, due to slow deposition of coke21. The used Pt/Nb2CTx and Pt/Ti3C2Tx were further characterized by HAADF-STEM to check the stability of the IMCs. The structures of Pt3Ti and Pt3Nb are preserved in the spent catalysts (Supplementary Figs. 14, 15), indicating that the IMCs NPs were stable under the LADH reaction conditions.

Fig. 4.

Catalytic performance and DFT calculation of Pt/MXene catalysts. a Plots of conversion vs. selectivity for propane dehydrogenation measured in 200 cm3 min−1 of 2.5% C3H8, 2.5% H2 balanced in N2 at 1.5 atm and 550 °C for Pt/Ti3C2Tx, Pt/Nb2CTx, and Pt/SiO2 catalyst. b Snapshots of optimized structures as numbered in c from side and top view angles (H* is not shown). c DFT-calculated free energy diagram of relevant (side-)reaction steps in propane dehydrogenation on Pt3Ti (111) and Pt (111) surfaces. The dotted lines denote the C–C cracking reactions of C3H6*, C3H5*, and C3H4*, generating CH2* + C2H4*, CH2* + C2H3*, and CH* + C2H3*, respectively. The dash-dot lines denote the further dehydrogenation of C3H6* to C3H5*, and C3H5* to C3H4*

To understand the high olefin selectivity of the intermetallic catalysts for PDH reaction, energy profiles of PDH reaction and possible side reactions were studied by DFT calculations. Snapshots of structures of reaction intermediates and transition states were illustrated in Fig. 4b, with the free energies of the relevant reaction pathways on Pt(111) and Pt3Ti(111) surfaces calculated and shown in Fig. 4c. PDH follows a step-wise C–H bond breaking process37, which starts with dissociative adsorption of propane forming surface alkyl species (intermediate 2), followed by the scission of a secondary C–H bond generating adsorbed olefins (intermediate 4). Our DFT results show that the free energy changes and barriers of the first two steps on the Pt3Ti(111) are higher than those on pure Pt(111), indicating weakened surface adsorption activity of the intermetallic phase consistent with the shifts in the 5d DOS indicated by DFT, XANES, and XPS. In the following steps, the adsorbed olefins may undergo desorption, further (deep) dehydrogenation (intermediate 7) or C–C breaking (intermediate 11) processes. The latter two steps are believed to generate the precursors leading to side reactions, i.e., coking and hydrogenolysis38.

On Pt(111), the free energy barrier for dehydrogenation of C3H6* to C3H5* is 0.19 eV lower than that of propylene desorption, indicating that deep dehydrogenation is more favorable on Pt(111) surface. In contrast, on Pt3Ti(111) the C3H6* desorption is more favored by 0.1 eV in barrier than further dehydrogenation. For direct comparison, the barrier of C3H6* desorption on Pt3Ti(111) (0.66 eV) is 0.25 eV lower than that on Pt(111) (0.91 eV). In addition, the free energy change of C3H6* desorption on Pt3Ti(111) (−1.17 eV) is 0.54 eV more favorable than that on Pt(111) (−0.63 eV). Overall, the introduction of Ti lowers the desorption barrier of C3H6* to the gas phase (0.66 eV of Pt3Ti(111) vs. 0.91 eV of Pt(111)) and increases the energy barrier for deep dehydrogenation. On both surfaces, C–C cracking of dehydrogenated reaction intermediates, e.g., C3H6*, C3H5*, and C3H4*, requires much higher activation energies and thus are less competitive. Nevertheless, on Pt3Ti(111) the C–C cracking steps (intermediates 11, 13, and 15) are all endergonic and hence are hindered compared with Pt(111) where C3H5* and C3H4* cracking are exergonic and much more favorable. These results rationalize the observed higher selectivity toward propylene for PDH by Pt3Ti intermetallic NPs compared to pure Pt.

Our experimental results and DFT calculations show that the Pt3Ti intermetallic phase has a lower d band center compared with that of monometallic Pt, which results in weaker adsorption of light hydrocarbon species and changes of the relative free energy and barriers of the reaction steps during dehydrogenation and side reactions. Lowering of the olefin desorption barrier to below that of deep dehydrogenation and C–C breaking contributes to the high catalyst selectivity. The same type of calculations were not conducted for the Pt/Nb2CTx catalyst due to its relatively less well-defined structure. However, similar catalyst electronic structure compared to Pt/Ti3C2Tx can be expected according to the in situ X-ray spectroscopy results. The adsorption properties, and reaction energetics are, therefore, also expected to be similar. The fact that the Pt/Nb2CTx catalyst has a slightly lower selectivity compared to Pt/Ti3C2Tx is likely due to the extent of the IMCs formation, i.e., full verses surface IMCs, and differences in electronic effects. These additional subtle catalytic differences demonstrate that the chemical properties of the catalysts are tunable using different MXene materials as the RMSI-active supports.

In summary, this work demonstrates two IMC catalysts selective for LADH achieved by RMSI between Pt NPs and Ti3C2Tx and Nb2CTx MXenes. The intermetallic surface is imaged by atomic resolution HAADF-STEM and its high catalytic selectivity is rationalized by DFT calculations. With MXenes as catalyst supports and through their active interactions with metal NPs, there is an opportunity to explore many new compositions for heterogeneous catalysis in industrial gas-phase reactions as well as electrochemical conversion, with the possibility that the chemical and electronic properties of the resulting catalysts can be tuned over a wider range than what is currently possible using conventional catalyst supports.

Methods

Synthesis of Ti3AlC2 and Nb2AlC

The Ti3AlC2 powder was synthesized by spark plasma sintering (SPS) of TiH2/Al/TiC. Commercial powders of titanium (II) hydride, aluminum and titanium (IV) carbide were mixed in a molar ratio of TiH2/Al/TiC = 1:1:1.8 in a graphite die coated with boron nitride (BN). Excess Al and less than a full equivalent of TiC were added because a small portion of Al will be lost during high-temperature processing, and carbon deficiencies exist in most Al-containing MAX phases. Then, the material was loaded in a Fuji-211lx SPS system and sintered at 1350 °C under 30 MPa for 1 h. The resulting Ti3AlC2 was then pulverized and sieved through a 325-mesh screen.

The Nb2AlC powder was synthesized by SPS of Nb/Al/graphite mixtures. Commercial powders of niobium, graphite and aluminum were mixed in a molar ratio of Nb:Al:C = 2:1.4:0.9 in a graphite die coated with boron nitride (BN). Then, the material was loaded in a Fuji-211lx SPS system and sintered at 1500 °C under 30 MPa for 1 h. The resulting Nb2AlC was then pulverized and sieved through a 400-mesh screen.

Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx and Nb2CT

Preparation of Ti3C2Tx MXene: Approximately 1 g of the prepared Ti3AlC2 powder was immersed in 10 mL of 50% aqueous hydrofluoric acid solution stirred with a magnetic bar for approximately 1 days at 35 °C. The resulting MXene suspension was repeatedly washed with deionized water (DI) and centrifuged until the pH reached ~5. The final MXene was dried under vacuum at room temperature and stored in a glove box until usage.

Preparation of Nb2CTx MXene: Approximately 1 g of the prepared Nb2AlC powder was immersed in 10 mL of 50% aqueous hydrofluoric acid (HF) solution stirred with a magnetic bar for approximately 3 days at 55 °C. The resulting MXene suspension was repeatedly washed with deionized water (DI) and centrifuged until the pH reached ~5. The final MXene was dried under vacuum at room temperature and stored in a glove box until usage.

Catalyst preparation

A monometallic Pt catalyst (2 wt. % Pt supported on Davisil 636 silica gel from Sigma-Aldrich) was synthesized using the incipient wetness impregnation (IWI) method. 0.20 g of tetraammineplatinum nitrate was dissolved in 3 mL of H2O.Approximately 30% ammonium hydroxide solution (NH4OH, 28% NH3 in H2O, ≥99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich) was then added to the solution until the pH reached 11. The obtained Pt precursor solution was added dropwise to 5 g of silica and stirred. After drying overnight under vacuum, the sample was calcined at 225 °C for 3 h and reduced at 550 °C in 5% H2/N2 for 30 min.

Pt supported on Ti3C2Tx and on Nb2CTx were prepared via a similar method. 0.20 g of tetraammineplatinum nitrate Pt(NH3)4(NO3)2 were dissolved in 0.5 mL of H2O to prepare 1 mol L−1 Pt precursor solution. 0.05 mL of such solution was impregnated on fresh Ti3C2Tx and Nb2CTx, respectively, prior to dying overnight under vacuum. The obtained catalysts were reduced at 550 °C in 5% H2/N2 for at least 0.5 h before each catalytic test or characterization.

LADH kinetics

LADH kinetics measurements were carried out in a quartz fixed-bed reactor with 3/8-inch ID. Catalysts around 0.02–0.15 g were diluted using pure SiO2 to achieve a total weight of 1.00 g for testing the performance. Reaction temperature was measured using a thermocouple inserted in a stainless-steel thermocouple well locating at the bottom center of the catalyst bed. Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph system quipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) was employed for analyzing the products. Prior to each measurement, the fresh catalysts were reduced by 5% H2/N2 (50 cm3 min−1) for 30 min at 550 °C with the temperature ramping rate of 15 °C min−1. Propane dehydrogenation was tested under a reaction atmosphere of 2.5% C3H8, 2.5% H2 balanced with N2. The total flow rate of the reactant mixture was 200 cm3 min−1. After 2 min on-stream, the catalyst selectivity was compared below 20% conversion at 550 °C and turnover rates (TORs, per surface Pt site) were measured under differential condition at conversion below 5%. For iso-butane dehydrogenation, a reaction atmosphere of 2.5% C3H8, 2.5% H2 balanced in N2 with a total flow rate of 100 cm3 min−1 was used. Catalyst performance was measured at 450 °C.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Y. W. appreciates the support from the Herbert L. Stiles Professorship and Iowa State University College of Engineering exploratory research projects. Z.W., and J.T.M., were supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Cooperative Agreement No. EEC-1647722, and W.N.D. by the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering at Purdue. The XPS data was obtained at the Surface Analysis Facility of the Birck Nanotechnology Center of Purdue University. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. MRCAT operations, beamline 10-BM, are supported by the Department of Energy and the MRCAT member institutions. L.Y. and H.X. acknowledge financial support from the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (ACS PRF 55581-DNI5) and the NSF CBET Catalysis Program (CBET-1604984). The computational resource used in this work is provided by the advanced research computing at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Author contributions

Z.L. and Z.W. conceived the idea and designed the present work. H.X., L.Y., and J. L. conducted DFT calculations. Z.L., Z.W., Y.C., N.L., and Z.Q. synthesized the catalysts and performed the catalytic evaluation. C.M., Z.W., J.M., carried out the spectroscopic characterizations. L.Z., T.M., Z.L., B.X., and E.Shi performed the detailed microscopic experiments. Y.W., J.M., H.X., and W.N.D. supervised the research.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

Provisional patent applications have been applied through the Iowa State University (US. Provisional Patent Application 62/572,903.).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhenwei Wu, Email: zwwu@stanford.edu.

Hongliang Xin, Email: hxin@vt.edu.

Jeffrey T. Miller, Email: mill1194@purdue.edu

Yue Wu, Email: yuewu@iastate.edu.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-07502-5.

References

- 1.Bell AT. The impact of nanoscience on heterogeneous catalysis. Science. 2003;299:1688–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1083671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shekhar M, et al. Size and support effects for the water–gas shift catalysis over gold nanoparticles supported on model Al2O3 and TiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4700–4708. doi: 10.1021/ja210083d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang X, et al. High-performance transition metal-doped Pt3Ni octahedra for oxygen reduction reaction. Science. 2015;348:1230–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsubu JC, et al. Adsorbate-mediated strong metal-support interactions in oxide-supported Rh catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:120. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kattel S, Liu P, Chen JG. Tuning selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation reactions at the metal/oxide interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9739–9754. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao ZJ, et al. Importance of metal-oxide interfaces in heterogeneous catalysis: a combined DFT, microkinetic, and experimental study of water-gas shift on Au/MgO. J. Catal. 2017;345:157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2016.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta P, Greeley J, Delgass WN, Schneider WF. Adsorption energy correlations at the metal-support boundary. ACS Catal. 2017;7:4707–4715. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b00979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li WZ, et al. Stable platinum nanoparticles on specific MgAl2O4 spinel facets at high temperatures in oxidizing atmospheres. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2481. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao RG, et al. Interfacial charge distributions in carbon-supported palladium catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:340. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00421-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cargnello M, et al. Control of metal nanocrystal size reveals metal-support interface role for ceria catalysts. Science. 2013;341:771–773. doi: 10.1126/science.1240148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willinger MG, et al. A case of strong metal-support interactions: combining advanced microscopy and model systems to elucidate the atomic structure of interfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:5998–6001. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tauster S, Fung S, Garten RL. Strong metal-support interactions. Group 8 noble metals supported on titanium dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:170–175. doi: 10.1021/ja00469a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tauster S, Fung S, Baker R, Horsley J. Strong interactions in supported-metal catalysts. Science. 1981;211:1121–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.211.4487.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naguib M, et al. Two‐dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:4248–4253. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naguib M, Mochalin VN, Barsoum MW, Gogotsi Y. 25th anniversary article: MXenes: a new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:992–1005. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, et al. Reactive metal-support interactions at moderate temperature in two-dimensional niobium-carbide-supported platinum catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:349–355. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0067-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penner S, Armbrüster M. Formation of intermetallic compounds by reactive metal–support interaction: a frequently encountered phenomenon in catalysis. ChemCatChem. 2015;7:374–392. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201402635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernal S, et al. Nanostructural Evolution of a Pt/CeO2 catalyst reduced at Increasing temperatures (473–1223 K): a HREM study. J. Catal. 1997;169:510–515. doi: 10.1006/jcat.1997.1707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beard BC, Ross PN. Platinum-titanium alloy formation from high-temperature reduction of a titania-impregnated platinum catalyst: implications for strong metal-support interaction. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:6811–6817. doi: 10.1021/j100284a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabnis KD, et al. Water-gas shift catalysis over transition metals supported on molybdenum carbide. J. Catal. 2015;331:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2015.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sattler JJ, Ruiz-Martinez J, Santillan-Jimenez E, Weckhuysen BM. Catalytic dehydrogenation of light alkanes on metals and metal oxides. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:10613–10653. doi: 10.1021/cr5002436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui Z, et al. Synthesis of structurally ordered Pt3Ti and Pt3V nanoparticles as methanol oxidation catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10206–10209. doi: 10.1021/ja504573a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saravanan G, et al. Pt3Ti nanoparticles: fine dispersion on SiO2 supports, enhanced catalytic CO oxidation, and chemical stability at elevated temperatures. Langmuir. 2010;26:11446–11451. doi: 10.1021/la100942h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naguib M, et al. New two-dimensional niobium and vanadium carbides as promising materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15966–15969. doi: 10.1021/ja405735d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mashtalir O, et al. Intercalation and delamination of layered carbides and carbonitrides. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1716. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H, Gao S, Dai C, Chen Y, Shi J. A Two-dimensional biodegradable niobium carbide (MXene) for photothermal tumor eradication in NIR-I and NIR-II biowindows. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:16235–16247. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b07818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nawaz Z. Light alkane dehydrogenation to light olefin technologies: a comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2015;31:413–436. doi: 10.1515/revce-2015-0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher JR, et al. Structural evolution of an intermetallic Pd-Zn catalyst selective for propane dehydrogenation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:28144–28153. doi: 10.1039/C5CP00222B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z, et al. Pd-In intermetallic alloy nanoparticles: highly selective ethane dehydrogenation catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016;6:6965–6976. doi: 10.1039/C6CY00491A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wegener EC, et al. Structure and reactivity of Pt-In intermetallic alloy nanoparticles: Highly selective catalysts for ethane dehydrogenation. Catal. Today. 2017;299:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2017.03.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammer B, Morikawa Y, Nørskov JK. CO chemisorption at metal surfaces and overlayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;76:2141. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cybulskis VJ, et al. Zinc Promotion of platinum for catalytic light alkane dehydrogenation: insights into geometric and electronic effects. ACS Catal. 2017;7:4173–4181. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b03603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammer B, Nørskov JK. Theoretical surface science and catalysis-calculations and concepts. Adv. Catal. 2000;45:71–129. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu W, Porosoff MD, Chen JG. Review of Pt-based bimetallic catalysis: from model surfaces to supported catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:5780–5817. doi: 10.1021/cr300096b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cortright R, Dumesic J. Microcalorimetric, spectroscopic, and kinetic studies of silica supported Pt and Pt/Sn catalysts for isobutane dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 1994;148:771–778. doi: 10.1006/jcat.1994.1263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang, C. et al. Promotion of Pd nanoparticles by Fe and formation of a Pd3Fe intermetallic alloy for propane dehydrogenation. Catal. Today, 10.1016/j.cattod.2018.07.043 (2018).

- 37.Yang ML, Zhu YA, Zhou XG, Sui ZJ, Chen D. First-principles calculations of propane dehydrogenation over PtSn catalysts. Acs Catal. 2012;2:1247–1258. doi: 10.1021/cs300031d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang ML, et al. DFT study of propane dehydrogenation on Pt catalyst: effects of step sites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:3257–3267. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00341g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.