Abstract

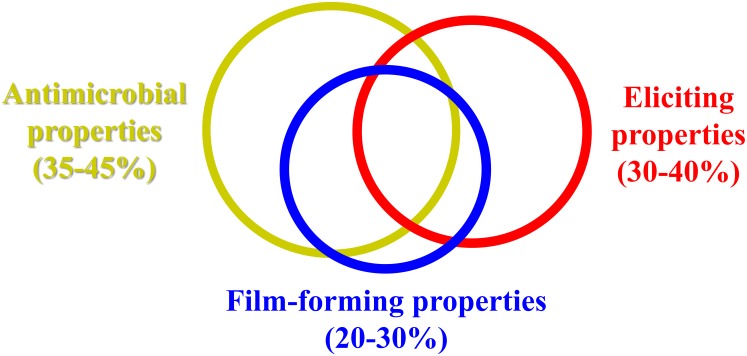

Chitosan is a natural biopolymer from crab shells that is known for its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioactivity. In human medicine, chitosan is used as a stabilizer for active ingredients in tablets, and is popular in slimming diets. Due to its low toxicity, it was the first basic substance approved by the European Union for plant protection (Reg. EU 2014/563), for both organic agriculture and integrated pest management. When applied to plants, chitosan shows triple activity: (i) elicitation of host defenses; (ii) antimicrobial activity; and (iii) film formation on the treated surface. The eliciting activity of chitosan has been studied since the 1990’s, which started with monitoring of enzyme activities linked to defense mechanisms (e.g., chitinase, β-1,3 glucanase, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase) in different fruit (e.g., strawberry, other berries, citrus fruit, table grapes). This continued with investigations with qRT-PCR (Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction), and more recently, with RNA-Seq. The antimicrobial activity of chitosan against a wide range of plant pathogens has been confirmed through many in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Once applied to a plant surface (e.g., dipping, spraying), chitosan forms an edible coating, the properties of which (e.g., thickness, viscosity, gas and water permeability) depend on the acid in which it is dissolved. Based on data in literature, we propose that overall, the eliciting represents 30 to 40% of the chitosan activity, its antimicrobial activity 35 to 45%, and its film-forming activity 20 to 30%, in terms of its effectiveness in the control of postharvest decay of fresh fruit. As well as being used alone, chitosan can be applied together with many other alternatives to synthetic fungicides, to boost its eliciting, antimicrobial and film-forming properties, with additive, and at times synergistic, interactions. Several commercial chitosan formulations are available as biopesticides, with their effectiveness due to the integrated combination of these three mechanisms of action of chitosan.

Keywords: antimicrobial activity, biopolymer, coating, induced resistance, natural fungicide

Introduction

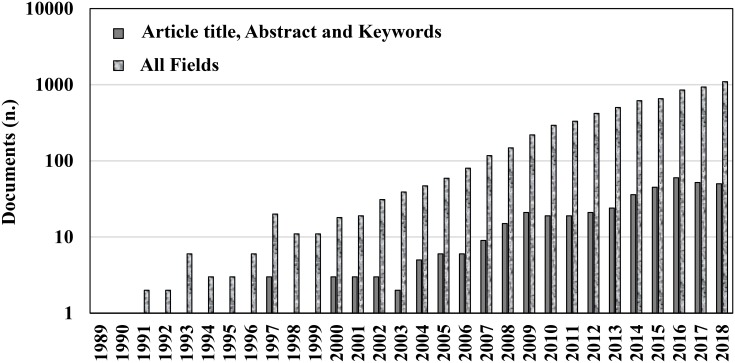

Chitosan is the linear polysaccharide of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine units joined by β-1,4-glycosidic links and it is obtained by deacetilation of chitin through exposure to NaOH solutions or to the enzyme chitinase. Chitosan and chitin are naturally occurring polymers. For their biocompatibility and biosafety, their applications are widespread in many industries, such as cosmetology, food, biotechnology, pharmacology, medicine, and agriculture (Ding et al., 2013; Lei et al., 2014). In particular, chitosan has increasing interest in plant protection as a natural fungicide and plant defense booster, and meets the interest of many researchers, that used it to prolong the storage of an array of fruit and vegetables worldwide. Chitosan was the first compound in the list of basic substances approved in the European Union for plant protection purposes (Reg. EU 66 2014/563), for both organic agriculture and integrated pest management. A comprehensive review on the available data on the effectiveness of chitosan was published recently, for its preservation of fruit and vegetables, both alone and in combination with other treatments, and its mechanisms of action (Romanazzi et al., 2017). However, the increasing knowledge of this biopolymer (Figure 1) and the fast advances in basic and applied research in this field require a more focused and schematic update based on the last 5 years of investigations (2013–2018). The reader can then focus on specific aspects from the long list of other reviews that have appeared on the subject, among which some have focused on the applications of chitosan to fruit and vegetables (Bautista-Baňos et al., 2006; Bautista-Baòos et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2011). When applied to plants, chitosan shows triple activity: (i) elicitation of host defenses; (ii) antimicrobial activity; and (iii) film formation on the treated surface. We will cover the recent information on these issues in the following sections, which is also listed comprehensively in the Tables, with examples of these applications.

FIGURE 1.

Number of documents available on Scopus through searches with keywords ‘chitosan’ and ‘postharvest’ in ‘Article title, Abstract, and Keywords’ or in ‘All fields’ published over the last 30 years (accessed on 6 November 2018).

Effectiveness of Chitosan in the Control of Postharvest Decay of Fruit

The potential effectiveness of chitosan as a coating for fresh fruit was first proposed by Muzzarelli (1986). The first in-vivo application of chitosan on fruit was in the Josep Arul Laboratory, by Ahmed El Ghaouth, who produced a list of papers through the last decade of the last century. These included El Ghaouth et al. (1992), where they applied chitosan to strawberries and other fruit, both alone and in combinations with other potential biocontrol agents, which then contributed to the develop of some commercial formulations. Following these promising investigations, and with the growing need for alternatives to the use of synthetic fungicides, chitosan use became popular, and it was proposed to be part of a new class of plant protectants (Bautista-Baňos et al., 2006). Chitosan coatings have now been applied to numerous temperate and subtropical fruit, both alone and in combination with other treatments (Tables 1–3), with generally additive, and in some cases synergistic, effectiveness (Romanazzi et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Postharvest chitosan treatments with other applications for storage decay of temperate fruit.

| Fruit | Decay agent | Combination with chitosan | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Table grapes | Botrytis cinerea | Salicylic acid | Shen and Yang, 2017 |

| General decay | Glucose complex | Gao et al., 2013 | |

| Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus stolonifer | – | de Oliveira et al., 2014 | |

| Fusarium oxysporum | – | Irkin and Guldas, 2014 | |

| General decay | – | Feliziani et al., 2013a | |

| General decay | Ultraviolet-C | Freitas et al., 2015 | |

| General decay | – | Al-Qurashi and Mohamed, 2015 | |

| Aspergillus niger, Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, Rhizopus stolonifer | Menta essential oil | Guerra et al., 2016 | |

| Botrytis cinerea | Salvia officinalis essential oil | Kanetis et al., 2017 | |

| Strawberry | Botrytis cinerea | Lavander and thyme essential oil | Sangsuwan et al., 2016 |

| General decay | Poeny extract | Pagliarulo et al., 2016 | |

| Penicillium expansum, Rhizopus stolonifer | Olive oil processing waste | Khalifa et al., 2016 | |

| Total microbial load | Natamycin, nisin, pomegranate, grape seed extract | Duran et al., 2016 | |

| Total microbial load | Quinoa protein-chitosan and quinoa protein-chitosan-sunflower oil | Valenzuela et al., 2015 | |

| Total microbial load | Sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate | Treviño-Garza et al., 2015 | |

| Botrytis cinerea | Zataria multiflora essential oil | Mohammadi et al., 2015 | |

| Rhizopus stolonifer | Cinnamon leaf essential oil containing oleic acid | Perdones et al., 2014 | |

| General decay | – | Benhabiles et al., 2013 | |

| General decay | Geraniol and thymol | Badawy et al., 2017 | |

| General decay | Carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose | Gol et al., 2013 | |

| Botrytis cinerea | Nanosized silver-chitosan composite | Moussa et al., 2013 | |

| General decay | Beeswax | Velickova et al., 2013 | |

| Botryosphaeria sp. | – | Wang et al., 2017 | |

| Pear | General decay | Cellulose nanocrystals | Deng et al., 2017 |

| General decay | Acylated soy protein isolate and stearic acid | Wu et al., 2017 | |

| Apple | General decay | Olive waste extracts | Khalifa et al., 2017, 2016 |

| Penicillium expansum | – | Darolt et al., 2016 | |

| Venturia inaequalis | – | Felipini et al., 2016 | |

| Penicillium expansum | – | Li et al., 2015 | |

| Calyx senescence | V | Deng et al., 2016 | |

| Citrus | Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium italicum | Silver nanoparticles | Al-Sheikh and Yehia, 2016 |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Pichia membranaefaciens | Zhou et al., 2016 | |

| Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium italicum | Cress and/or pomegranate extracts | Tayel et al., 2016 | |

| Penicillium digitatum | Clove oil | Shao et al., 2015 | |

| Penicillium digitatum | Cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics from Bacillus subtilis | Waewthongrak et al., 2015 | |

| General decay | Carboxymethyl cellulose | Arnon et al., 2014 | |

| Total microbial load | Silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles | Kaur et al., 2017 | |

| Peach | Monilinia laxa | Polyethylene terephthalate punnets containing thyme oil and sealed with chitosan/boehmite nanocomposite lidding films | Cindi et al., 2015 |

| General decay | γ-ray | Elbarbary and Mostafa, 2014 | |

| Monilinia fructicola | Ma et al., 2013 | ||

| Monilinia laxa, Botrytis cinerea, Rhizopus stolonifer | – | Feliziani et al., 2013b | |

| Sweet cherry | General decay | – | Pasquariello et al., 2015 |

| – | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose | Shanmuga Priya et al., 2014 | |

| Plum | General decay | Ascorbic acid | Liu et al., 2014 |

Table 3.

Preharvest chitosan treatments with other applications for storage decay of temperate fruit.

| Fruit | Decay | Combination with chitosan | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus | Penicillium digitatum | Rhodosporidium paludigenum | Lu et al., 2014 |

| Peach | General decay | Calcium chloride | Gayed et al., 2017 |

| Jujube fruit | Alternaria alternata | – | |

| Table grapes | Botrytis cinerea | Salicylic acid | Shen and Yang, 2017 |

| Botrytis cinerea | – | Feliziani et al., 2013a | |

| Strawberry | Botrytis cinerea and Rhizopus stolonifer | – | Romanazzi et al., 2013; Feliziani et al., 2015 |

| Botrytis cinerea | – | Lopes et al., 2014 | |

| General decay | – | Saavedra et al., 2016 | |

| Sweet cherry | Monilinia laxa, Botrytis cinerea, and Rhizopus stolonifer | – | Feliziani et al., 2013a |

Table 2.

Postharvest chitosan treatments with other applications for storage decay of subtropical fruit.

| Fruit | Decay agent | Combination with chitosan | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mango | Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) | Spermidine | Jongsri et al., 2017 |

| Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides), stem-end rot (L. theobromae strains) | Lactoperoxidase system incorporated chitosan films | Kouakou et al., 2013 | |

| Anthracnose | Mentha piperita L. essential oil | de Oliveira et al., 2017 | |

| Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides), stem-end rot (L. theobromae strains) | Lactoperoxidase system incorporated chitosan films | Kouakou et al., 2013 | |

| Anthrcanose | Mentha piperita L. essential oil | de Oliveira et al., 2017 | |

| Citrus | Green mold (Penicillium digitatum) | Bacillus subtilis ABS-S14 | Waewthongrak et al., 2015 |

| Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) | Pichia membranifaciens | Zhou et al., 2016 | |

| Avocado | Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) | Thyme oil | Bill et al., 2014 |

| Tomato | Alternaria alternata | Methyl jasmonate | Chen et al., 2014 |

| Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus stolonifer | Essential oil from Origanum vulgare L | Barreto et al., 2016 | |

| Pomegranate | Penicillium spp., Pilidiella granati | Lemongrass film | Munhuweyi et al., 2017 |

Chitosan Eliciting Activity

Chitosan is known to elicit plant defences against several classes of pathogens, including fungi, viruses, bacteria and phytoplasma (El Hadrami et al., 2010). Moreover, in some studies, its eliciting activity was reported to be effective on pests (Badawy and Rabea, 2016). Based on our experience, the eliciting activity of chitosan accounts for 30 to 40% of its effectiveness in the control of postharvest decay of fresh fruit (Figure 2). The extent of this eliciting activity depends on the reactivity of the fruit tissues, and it is well known that fruit responses to stress decline with ripening (Romanazzi et al., 2016). This eliciting activity of chitosan has been studied since the 1990’s, which started with monitoring of the activities of enzymes linked to the defense mechanisms (e.g., chitinase) in different fruit (e.g., strawberries) (El Ghaouth et al., 1992). This was followed by investigations on other berries, citrus fruit and table grapes, among others. More recently, tools such as qRT-PCR and in recent years RNA-Seq (RNA-Sequencing) have allowed important information to be gained, first at the level of single gene expression, and then later at the level of global gene expression (Xoca-Orozco et al., 2017). This has provided good understanding of the multiple actions of chitosan applications and how they affect a number of physiological changes in fruit. As an example, the application of chitosan to strawberries at different times before harvest can affect the expression of a thousand or more genes (Landi et al., 2017). Some examples that have become available in the literature over the last 5 years are listed in Table 4, which deal with the physiological changes that can occur in chitosan-treated fruit, both when the biopolymer is applied alone, and when it is combined with other treatments. The eliciting activity of chitosan is particularly effective toward latent infections, as a more reactive fruit can stop the infection process, through a balance that resembles quorum sensing, which is well known for bacterial infections (Papenfort and Bassler, 2016).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of antimicrobial, eliciting, and film-forming properties of chitosan.

Table 4.

Physiological changes that can occur in fresh fruit after chitosan treatment, alone or in combination with other applications.

| Fruit | Physiological change | Combination with chitosan | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | 20 genes involved in defence responses, metabolism, signal transduction, transcription factors, protein biosynthesis, cytoskeleton. | – | Li et al., 2015 |

| Total phenolic, flavonoids, antioxidants, pigments, weight loss | Olive waste extract | Khalifa et al., 2017 | |

| Peach | Malondialdehyde content | γ-ray | Elbarbary and Mostafa, 2014 |

| Catalase, peroxidase, β-1,3-glucanase and chitinase | – | Ma et al., 2013 | |

| Total soluble solids, weight loss, ascorbic acid content | Silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles | Kaur et al., 2017 | |

| Color and fruit firmness | Polyethylene terephthalate punnets containing thyme oil and sealed with chitosan/boehmite nanocomposite lidding films | Cindi et al., 2015 | |

| Fruit firmness, weight loss, total soluble solids, total phenolic content, and titratable acidity | Calcium chloride | Gayed et al., 2017 | |

| Plum | Fruit firmness, respiration rate, fruit color, polygalacturonase, superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, catalase, polyphenol oxidase, phenylalanine ammonia lyase and pectin methylesterase activities, superoxide free radicals, malondialdehyde content | Ascorbic acid | Liu et al., 2014 |

| Sweet cherry | Malondialdehyde content and superoxide dismutase, catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, guaiacol peroxidase lipoxygenase activities | – | Pasquariello et al., 2015 |

| Strawberry | Over 5000 differently expressed genes | – | Landi et al., 2017 |

| 18 defence genes | – | Landi et al., 2014 | |

| Fruit color | – | Feliziani et al., 2015 | |

| Fruit firmness, anthocyanin and total phenol content | – | Saavedra et al., 2016 | |

| Weight loss, titratable acidity, pH, total soluble solids, total phenols, anthocyanin and ascorbic acid content, activity of polygalacturonase, pectin methyl esterase, β-galactosidase and cellulose | Carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose | Gol et al., 2013 | |

| Weight loss | Lavander and thyme essential oil | Sangsuwan et al., 2016 | |

| Titratable acidity, soluble solids content | – | Benhabiles et al., 2013 | |

| pH and soluble solids content | Natamycin, nisin, pomegranate, grape seed extract | Duran et al., 2016 | |

| Weight loss, ascorbic acid | Poeny extract | Pagliarulo et al., 2016 | |

| Weight loss, respiration rate, skin and flesh color, firmness, pH, titratable acidity, soluble solids content, reducing sugars content | Beeswax | Velickova et al., 2013 | |

| Weight loss, firmness, color and total soluble solids content | Sodium benzoate, potassium sorbate | Treviño-Garza et al., 2015 | |

| Weight losses, total soluble solids and titratable acidity | Olive waste extract | Khalifa et al., 2016 | |

| Allergen-related gene | – | Petriccione et al., 2017 | |

| Table grapes | Phenylalanine ammonia lyase, chitinase, and β-1, 3-glucanase, phenolic compounds, respiration rate, weight loss, total soluble solids, titratable acidity | Salicylic acid | Shen and Yang, 2017 |

| Total phenols, flavonoids and ascorbic acid content, activities of peroxidase, polyphenoloxidase, polygalacturonase, and xylanase, fruit firmness | – | Al-Qurashi and Mohamed, 2015 | |

| Fruit color | – | Irkin and Guldas, 2014 | |

| Weight loss, titratable acidity, pH and soluble solids content, resveratrol content | Ultraviolet-C | Freitas et al., 2015 | |

| Weight loss, soluble solids content and titratable acidity | Salvia officinalis essential oil | Kanetis et al., 2017 | |

| Firmness, titratable acidity, soluble solids, color, weight loss | Menta essential oil | Guerra et al., 2016 | |

| Total soluble solids, ascorbic acid content, titratable acidity, weight loss, respiration rate, activities of peroxidase and superoxide dismutase | Glucose complex | Gao et al., 2013 | |

| Titratable acidity, soluble solids, color, firmness | de Oliveira et al., 2014 | ||

| Chitinase activity, quercetin, myricetin, and resveratrol content | – | Feliziani et al., 2013b | |

| Citrus | Chitinase and phenylalanine ammonia lyase | – | Lu et al., 2014 |

| 640 differentially expressed genes, many involved in secondary metabolism and hormone metabolism pathways | – | Coqueiro et al., 2015 | |

| Fruit firmness, weight loss, total soluble solids | Carboxymethyl cellulose | Arnon et al., 2014 | |

| Peroxidase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | Cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics from Bacillus subtilis | Waewthongrak et al., 2015 | |

| Contents of chlorophylls and total carotenoids | |||

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, β-1,3-glucanase, chitinase | |||

| Jujube | Fruit firmness, cellulase, pectinase | – | Guo et al., 2017 |

| Pear | Total phenolic and flavonoid contents, superoxide dismutase, peroxidase and catalase activities, total antioxidant activity | Calcium chloride | Kou et al., 2014a |

| Malic acid-metabolising enzymes and related genes expression | Calcium chloride | Kou et al., 2014b | |

| Mango | Peroxidase (POD) and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) gene expression | – | Gutierrez-Martinez et al., 2017 |

| Kiwifruit | Induced gene expression and increased enzymatic activity of catalase, superoxide dismutase and ascorbate peroxidase | – | Zheng et al., 2017 |

Chitosan Antimicrobial Activity

Numerous studies on chitosan inhibitory activities toward numerous microrganisms have been carried out since the first report of almost half a century ago (Allan and Hadwiger, 1979). The antimicrobial activities of chitosan against a wide range of plant pathogens have been confirmed by any of in-vitro and in-vivo studies. The antimicrobial activity of chitosan is one of its main properties, and this depends on the concentration at which it is applied. In the control of postharvest decay of fresh fruit, the antimicrobial activity can account for 35–45% of its effectiveness, as an antifungal barrier on a fruit inhibits the germination of fungal spores and slows down the rate of decay-causing fungi of already infected fruit, both latently and actively (Figure 2). A standard application rate of chitosan to provide a significant control of postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables can be considered 1%, except for the control of Penicillia, where higher concentrations may be needed to provide a good effectiveness. The degree of deacetylation and the molecular weight of chitosan characterize its properties, such as the number of positively charges of amino groups and therefore, its electrostatic interactions with different substrate and organisms at different pH. Chitosan with a higher degree of deacetylation, which has greater numbers of positive charges, would also be expected to have stronger antibacterial activities. On the other hand, numerous studies have generated different results relating to correlations between the chitosan bactericidal activities and its molecular weight (Romanazzi et al., 2017). In addition, there are many differences between the chitosan antifungal and antibacterial activities and several mechanisms relating to these remain still unclear and further researches are needed (Romanazzi et al., 2017).

Chitosan Film-Forming Properties

Once applied to a plant surface by dipping or spraying, chitosan can form an edible coating, the properties of which (e.g., thickness, viscosity, gas, and water permeability) greatly depend on the acid in which the biopolymer is dissolved. The film-forming properties of chitosan account for 20–30% of the chitosan effectiveness in the control of postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables (Figure 2). Coating produces a barrier for gas exchanges and reduced respiration, and slows down fruit ripening. Of note, a less ripe fruit is less sensitive to postharvest decay.

Toward Large-Scale Commercial Applications

When first used in experimental trials, chitosan needed to be dissolved in an acid (e.g., hydrochloric acid, acetic acid, which were among the most effective ones; see Romanazzi et al., 2009), and then taken to the optimal pH (∼5.6) This approach can even take 1–2 days, and it is impractical for use by growers. More recently, several commercial chitosan formulations that can be dissolved in water have become available on the market to be used as a biopesticides (Table 5). Some of these are formulated as powders, and then the cost of shipping is lower (although still higher compared to most of the commercially available synthetic fungicides), although the chitosan needs to be dissolved in water, in some cases a few hours before its application. This makes chitosan more difficult to use, as the grower wants to use an alternative to synthetic fungicides in the same way as a commercial compound, such that it should have the same effectiveness. This objective can be achieved with liquid formulations, which have concentrations of 2–15%. In this case, the cost of shipping is higher, as the volumes are larger due to the amounts of water that travel with the chitosan. In tests of three different commercial products, even when used at the same concentration, differential effectiveness was seen (Feliziani et al., 2013a). The higher cost of chitosan treatment compared to standard applications might also induce companies toward the use of low doses (e.g., even well below 0.1%), Based on data in literature, the optimal dose is around 1%, while decreasing the concentration, the effectiveness declines. Furthermore, when the concentration of chitosan is decreased, its effectiveness also declines. However, applications to the plant canopy also need to take in account possible phytotoxic effects, mainly if repeated applications occur. This has been shown for grapevines (Romanazzi et al., 2016a), such that for these purposes a good concentration might be 0.5%. However, under some particular conditions, even low concentrations of chitosan (e.g., 0.02%) in a commercial formulation can be beneficial, such as for the improved storage of litchi (Jiang et al., 2018).

Table 5.

Some chitosan-based commercial products that are available for control of postharvest diseases of fruit and vegetables.

| Product trade name | Company (Country) | Formulation | Active ingredient (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chito plant | ChiPro GmbH (Bremen, Germany) | Powder | 99.9 |

| Chito plant | ChiPro GmbH (Bremen, Germany) | Liquid | 2.5 |

| OII-YS | Venture Innovations (Lafayette, LA, United States) | Liquid | 5.8 |

| KaitoSol | Advanced Green Nanotechnologies Sdn Bhd (Cambridge, United Kingdom) | Liquid | 12.5 |

| Armour-Zen | Botry-Zen Limited (Dunedin, New Zealand) | Liquid | 14.4 |

| Biorend | Bioagro S.A. (Chile) | Liquid | 1.25 |

| Kiforce | Alba Milagro (Milan, Italy) | Liquid | 6 |

| FreshSeal | BASF Corporation (Mount Olive, NJ, United States) | Liquid | 2.5 |

| ChitoClear | Primex ehf (Siglufjordur, Iceland) | Powder | 100 |

| Bioshield | Seafresh (Bangkok, Thailand) | Powder | 100 |

| Biochikol 020 PC | Gumitex (Lowics, Poland) | Liquid | 2 |

| Kadozan | Lytone Enterprise, Inc. (Shanghai Branch, China) | Liquid | 2 |

| Kendal cops | Valagro (Atessa, Italy) | Liquid | 4 |

| Chitosan 87% | Korea Chengcheng Chemical Company (China) | TC (Technical material) | 87 |

| Chitosan 2% | Korea Chengcheng Chemical Company (China) | SLX (Soluble concentrate) | 2 |

Concluding Remarks

The effectiveness of chitosan application arises from the integrated combination of its three mechanisms of action. There are increasing consumer requests for fruit and vegetables to be free from residues of synthetic pesticides, such that the rules defined by the public administration have become more limiting in terms of the active ingredients allowed and the maximum residue limits. Also, large stores compete with each other to further reduce these limits, compared to the legal thresholds (Romanazzi et al., 2016b). These trends make the concept of the application of alternatives to synthetic fungicides more popular, and among these the main one that is already used in human medicine is chitosan, which is particularly welcomed by public opinion. These aspects have promoted further studies based on the multiple actions of chitosan on fruit and vegetables. Therefore, further increases in our knowledge are expected following the widespread practical application of chitosan due to the regulation of its use in agriculture and the interest of companies to promote chitosan-based products, with potential benefits for the growers, the consumers and the environment.

Author Contributions

GR proposed the review, collected data on chitosan popularity over time and on commercial products, coordinated the authors, and wrote the article. EF collected papers on effectiveness of chitosan on temperate fruit and on the mechanisms of action in the tables, and helped with the writing. DS collected papers on effectiveness of chitosan on tropical fruit and on the mechanisms of action in the tables, and helped with the writing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Allan C. R., Hadwiger L. A. (1979). The fungicidal effect of chitosan on fungi of varying cell wall composition. Exp. Mycol. 3 285–287. 10.1016/S0147-5975(79)80054-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qurashi A. D., Mohamed S. A. (2015). Postharvest chitosan treatment affects quality, antioxidant capacity, antioxidant compounds and enzymes activities of ‘El-Bayadi’ table grapes after storage. Sci. Hortic. 197 393–398. 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheikh H., Yehia R. S. S. (2016). In vitro antifungal efficacy of Aspergillus niger ATCC 9642 chitosan-AgNPs composite against post-harvest disease of citrus fruits. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 52 413–420. 10.1134/S0003683816040177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon H., Zaitsev Y., Porat R., Poverenov E. (2014). Effects of carboxymethyl cellulose and chitosan bilayer edible coating on postharvest quality of citrus fruit. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 87 21–26. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy M., Rabea I. (2016). “Chitosan and its derivatives as active ingredients against plant pests and diseases,” in Chitosan in the Preservation of Agricultural Commodities, eds Bautista-Baòos S., Romanazzi G., Jiménez-Aparicio A. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 179–219. 10.1016/B978-0-12-802735-6.00007-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy M. E. I., Rabea E. I., El-Nouby M. A. M., Ismail R. I. A., Taktak N. E. M. (2017). Strawberry shelf life, composition, and enzymes activity in response to edible chitosan coatings. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 17 117–136. 10.1080/15538362.2016.1219290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto T., Andrade S. C., Maciel J. F., Arcanjo N. M. O., Madruga M. S., Meireles B., et al. (2016). A Chitosan coating containing essential oil from Origanum vulgare L. to control postharvest mold infections and keep the quality of cherry tomato fruit. Front. Microbiol. 7:1724. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Baòos S., Hernandez-Lauzardo A. N., Velazquez-del Valle M. G., Hernandez-Lopez M., Ait Barka E., Bosquez-Molina E., et al. (2006). Chitosan as a potential natural compound to control pre and postharvest diseases of horticultural commodities. Crop Prot. 25 108–118. 10.1016/j.cropro.2005.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Baòos S., Romanazzi G., Jiménez-Aparicio A. (eds) (2016). Chitosan in the Preservation of Agricultural Commodities. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Benhabiles M. S., Drouiche N., Lounici H., Pauss A., Mameri N. (2013). Effect of shrimp chitosan coatings as affected by chitosan extraction processes on postharvest quality of strawberry. J. Food Meas. Charact. 7 215–221. 10.1007/s11694-013-9159-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bill M., Sivakumar D., Korsten L., Thompson A. K. (2014). The efficacy of combined application of edible coating and thyme oil in inducing resistance components in avocado (Persea americana Mill.) against anthracnose during post-harvest storage. Crop Prot. 64 159–167. 10.1016/j.cropro.2014.06.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Zou X., Liu Q., Wang F., Feng W., Wan N. (2014). Combination effect of chitosan and methyl jasmonate on controlling Alternaria alternata and enhancing activity of cherry tomato fruit defence mechanisms. Crop Prot. 56 31–36. 10.1016/j.cropro.2013.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cindi M. D., Shittu T., Sivakumar D., Bautista-Baños S. (2015). Chitosan boehmite-alumina nanocomposite films and thyme oil vapour control brown rot in peaches (Prunus persica L.) during postharvest storage. Crop Prot. 72 127–131. 10.1016/j.cropro.2015.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coqueiro D. S. O., de Souza A. A., Takita M. A., Rodrigues C. M., Kishi L. T., Machado M. A. (2015). Transcriptional profile of sweet orange in response to chitosan and salicylic acid. BMC Genomics 16:288. 10.1186/s12864-015-1440-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darolt J. C., Rocha Neto A. C., Di Piero R. M. (2016). Effects of the protective, curative, and eradicative applications of chitosan against Penicillium expansum in apples. Braz. J. Microbiol. 47 1014–1019. 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira C. E. V., Magnani M., de Sales C. V., de Souza Pontes A. L., Campos-Takaki G. M., Stamford T. C. M., et al. (2014). Effects of post-harvest treatment using chitosan from Mucor circinelloides on fungal pathogenicity and quality of table grapes during storage. Food Microbiol. 44 211–219. 10.1016/j.fm.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira K. ÁR., Berger L. R. R., de Araújo S. A., Camara M. P. S., de Souza E. L. (2017). Synergistic mixtures of chitosan and Menta piperita L. essential oil to inhibit Colletorichum species and anthracnose development in mango cultivar Tommy Atkins. Food Microbiol. 66 96–103. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Yin B., Yao S., Wang W., Zeng K. (2016). Postharvest application of oligochitosan and chitosan reduces calyx alterations of citrus fruit induced by ethephon degreening treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64 7394–7403. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b02534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z., Jung J., Simonsen J., Wang Y., Zhao Y. (2017). Cellulose nanocrystal reinforced chitosan coatings for improving the storability of postharvest pears under both ambient and cold storages. J. Food Sci. 82 453–462. 10.1111/1750-3841.13601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., Nie Z., Deng H., Xiao L., Du Y., Shi X. (2013). Antibacterial hydrogel coating by electrophoretic co-deposition of chitosan/alkynyl chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 98 1547–1552. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran M., Aday M. S., Zorba N. N. D., Temizkan R., Büyükcan M. B., Caner C. (2016). Potential of antimicrobial active packaging “containing natamycin, nisin, pomegranate and grape seed extract in chitosan coating” to extend shelf life of fresh strawberry. Food Bioprod. Process. 98 354–363. 10.1016/j.fbp.2016.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghaouth A., Arul J., Grenier J., Asselin A. (1992). Antifungal activity of chitosan on two postharvest pathogens of strawberry fruits. Phytopatology 82 398–402. 10.1094/Phyto-82-398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Hadrami A., Adam L. R., El Hadrami I., Daayf F. (2010). Chitosan in plant protection. Mar. Drugs 8 968–987. 10.3390/md8040968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbarbary A. M., Mostafa T. B. (2014). Effect of γ-rays on carboxymethyl chitosan for use as antioxidant and preservative coating for peach fruit. Carbohydr. Polym. 104 109–117. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felipini R. B., Boneti J. I., Katsurayama Y., Neto A. C. R., Veleirinho B., Maraschin M., et al. (2016). Apple scab control and activation of plant defence responses using potassium phosphite and chitosan. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 145 929–939. 10.1007/s10658-016-0881-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feliziani E., Landi L., Romanazzi G. (2015). Preharvest treatments with chitosan and other alternatives to conventional fungicides to control postharvest decay of strawberry. Carbohydr. Polym. 132 111–117. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.05.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliziani E., Romanazzi G., Margosan D. A., Mansour M. F., Smilanick J. L., Gu S., et al. (2013a). Preharvest fungicide, potassium sorbate, or chitosan use on quality and storage decay of table grapes. Plant Dis. 97 307–314. 10.1094/pdis-12-11-1043-re [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliziani E., Santini M., Landi L., Romanazzi G. (2013b). Pre- and postharvest treatment with alternatives to synthetic fungicides to control postharvest decay of sweet cherry. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 78 133–138. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas P. M., López-Gálvez F., Tudela J. A., Gil M. I., Allende A. (2015). Postharvest treatment of table grapes with ultraviolet-C and chitosan coating preserves quality and increases stilbene content. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 105 51–57. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P., Zhu Z., Zhang P. (2013). Effects of chitosan-glucose complex coating on postharvest quality and shelf life of table grapes. Carbohydr. Polym. 95 371–378. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayed A. A. N. A., Shaarawi S. A. M. A., Elkhishen M. A., Elsherbini N. R. M. (2017). Pre-harvest application of calcium chloride and chitosan on fruit quality and storability of “Early Swelling” peach during cold storage. Ciência Agrot. 41 220–231. 10.1590/1413-70542017412005917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gol N. B., Patel P. R., Rao T. V. R. (2013). Improvement of quality and shelf-life of strawberries with edible coatings enriched with chitosan. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 85 185–195. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra I. C. D., De Oliveira P. D. L., Santos M. M. F., Lúcio A. S. S. C., Tavares J. F., Barbosa-Filho J. M., et al. (2016). The effects of composite coatings containing chitosan and Mentha (piperita L. or x villosa Huds) essential oil on postharvest mold occurrence and quality of table grape cv. Isabella. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 34 112–121. 10.1016/j.ifset.2016.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Xing Z., Yu Q., Zhao Y., Zhu E. (2017). Effectiveness of preharvest application of submicron chitosan dispersions for controlling Alternaria rot in postharvest jujube fruit. J. Phytopathol. 165 425–431. 10.1111/jph.12576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Martinez P., Bautista-Baños S., Berúmen-Varela S., Ramos-Guerrero A., Hernández-Ibaéz A. M. (2017). In vitro response of Colletotrichum to chitosan. Effect on incidence and quality on tropical fruit. Enzymatic expression in mango. Acta Agron. 62 282–289. 10.15446/acag.v66n2.53770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irkin R., Guldas M. (2014). Chitosan coating of red table grapes and fresh-cut honey melons to inhibit Fusarium oxysporum growth. J. Food Process. Preserv. 38 1948–1956. 10.1111/jfpp.12170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Lin H., Shi J., Neethirajan S., Lin Y., Chen Y., et al. (2018). Effects of a novel chitosan formulation treatment on quality attributes and storage behavior of harvested litchi fruit. Food Chem. 252 134–141. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongsri P., Rojsitthisak P., Wangsomboondee T., Seraypheap K. (2017). Influence of chitosan coating combined with spermidine on anthracnose disease and qualities of ‘Nam Dok Mai’ mango after harvest. Sci. Hortic. 224 180–187. 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.06.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanetis L., Exarchou V., Charalambous Z., Goulas V. (2017). Edible coating composed of chitosan and Salvia fruticosa Mill. extract for the control of grey mould of table grapes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 97 452–460. 10.1002/jsfa.7745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M., Kalia A., Thakur A. (2017). Effect of biodegradable chitosan–rice-starch nanocomposite films on post-harvest quality of stored peach fruit. Starch 69:1600208 10.1002/star.201600208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa I., Barakat H., El-Mansy H. A., Soliman S. A. (2016). Improving the shelf-life stability of apple and strawberry fruits applying chitosan-incorporated olive oil processing residues coating. Food Packag. Shelf Life 9 10–19. 10.1016/j.fpsl.2016.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa I., Barakat H., El-Mansy H. A., Soliman S. A. (2017). Preserving apple (Malus domestica var. Anna) fruit bioactive substances using olive wastes extract-chitosan film coating. Inform. Process. Agric. 4 90–99. 10.1016/j.inpa.2016.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kou X. H., Guo W. L., Guo R. Z., Li X. Y., Xue Z. H. (2014a). Effects of chitosan, calcium chloride, and pullulan coating treatments on antioxidant activity in Pear cv. “Huang guan” during storage. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 7 671–681. 10.1007/s11947-013-1085-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kou X. H., Wang S., Zhang Y., Guo R. Z., Wu M. S., Chen Q., et al. (2014b). Effects of chitosan and calcium chloride treatments on malic acid-metabolizing enzymes and the related gene expression in post-harvest pear cv. “Huang guan.” Sci. Hortic. 165 252–259. 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.10.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouakou I. M., Clementine M., Didier M., Gérard L., Ducamp-Collin M. N. (2013). Antimicrobial and physical properties of edible chitosan films enhanced by lactoperoxidase system. Food Hydrocoll. 30 576–580. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.07.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landi L., De Miccolis Angelini R. M., Pollastro S., Feliziani E., Faretra F., Romanazzi G. (2017). Global transcriptome analysis and identification of differentially expressed genes in strawberry after preharvest application of benzothiadiazole and chitosan. Front. Plant Sci. 8:235. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi L., Feliziani E., Romanazzi G. (2014). Expression of defense genes in strawberry fruits treated with different resistance inducers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62 3047–3056. 10.1021/jf404423x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J., Yang L., Zhan Y., Wang Y., Ye T., Deng H., et al. (2014). Plasma treated polyethylene terephthalate/polypropylene films assembled with chitosan and various preservatives for antimicrobial food packaging. Coll. Surf. Biointerfaces 114 60–66. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wang Y., Liu F., Yang Y., Wu Z., Cai H., et al. (2015). Effects of chitosan on control of postharvest blue mold decay of apple fruit and the possible mechanisms involved. Sci. Hortic. 186 77–83. 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.02.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Yuan C., Chen Y., Li H., Liu J. (2014). Combined effects of ascorbic acid and chitosan on the quality maintenance and shelf life of plums. Sci. Hortic. 176 45–53. 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.06.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes U. P., Zambolim L., Costa H., Pereira O. L., Finger F. L. (2014). Potassium silicate and chitosan application for gray mold management in strawberry during storage. Crop Prot. 63 103–106. 10.1016/j.cropro.2014.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Liu Y., Yang J., Azat R., Yu T., Zheng X. (2014). Quaternary chitosan oligomers enhance resistance and biocontrol efficacy of Rhodosporidium paludigenum to green mold in satsuma orange. Carbohydr. Polym. 113174–181. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.06.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Yang L., Yan H., Kennedy J. F., Meng X. (2013). Chitosan and oligochitosan enhance the resistance of peach fruit to brown rot. Carbohydr. Polym. 94 272–277. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi A., Hashemi M., Hosseini S. M. (2015). Nanoencapsulation of Zataria multiflora essential oil preparation and characterization with enhanced antifungal activity for controlling Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of gray mould disease. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 28 73–80. 10.1016/j.ifset.2014.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa S. H., Tayel A. A., Alsohim A. S., Abdallah R. R. (2013). Botryticidal activity of nanosized silver-chitosan composite and its application for the control of gray mold in strawberry. J. Food Sci. 78 1589–1594. 10.1111/1750-3841.12247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munhuweyi K., Oluwafemi J. C., Lennox C. L., van Reenen A. J., Opara L. U. (2017). In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of chitosan-essential oils against pomegranate fruit pathogens. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 129 9–22. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzarelli R. A. A. (1986). “Filmogenic properties of chitin/chitosan,” in Chitin in Nature and Technology, eds Muzzarelli R. A. A., Jeuniaux C., Gooday G. W. (New York, NY: Plenum Press; ), 389–396. 10.1007/978-1-4613-2167-5_48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarulo C., Sansone F., Moccia S., Russo G. L., Aquino R. P., Salvatore P., et al. (2016). Preservation of strawberries with an antifungal edible coating using peony extracts in chitosan. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 9 1951–1960. 10.1007/s11947-016-1779-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papenfort K., Bassler B. L. (2016). Quorum sensing signal–response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14 576–588. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquariello M. S., Di Patre D., Mastrobuoni F., Zampella L., Scortichini M., Petriccione M. (2015). Influence of postharvest chitosan treatment on enzymatic browning and antioxidant enzyme activity in sweet cherry fruit. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 109 45–56. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdones Á, Vargas M., Atarés L., Chiralt A. (2014). Physical, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of chitosan-cinnamon leaf oil films as affected by oleic acid. Food Hydrocoll. 36 256–264. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petriccione M., Mastrobuoni F., Zampella L., Nobis E., Capriolo G., Scortichini M. (2017). Effect of chitosan treatment on strawberry allergen-related gene expression during ripening stages. J. Food Sci. Technol. 54 1340–1345. 10.1007/s13197-017-2554-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Feliziani E., Bautista-Baòos S., Sivakumar D. (2017). Shelf life extension of fresh fruit and vegetables by chitosan treatment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57 579–601. 10.1080/10408398.2014.900474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Feliziani E., Santini M., Landi L. (2013). Effectiveness of postharvest treatment with chitosan and other resistance inducers in the control of storage decay of strawberry. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 75 24–27. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.07.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Lichter A., Mlikota Gabler F., Smilanick J. (2012). Recent advances on the use of natural and safe alternatives to conventional methods to control postharvest gray mold of table grapes. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 63 141–147. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Mlikota Gabler F., Margosan D. A., Mackey B. E., Smilanick J. L. (2009). Effect of chitosan dissolved in different acids on its ability to control postharvest gray mold of table grape. Phytopathology 99 1028–1036. 10.1094/PHYTO-99-9-1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Sanzani S. M., Bi Y., Tian S., Gutierrez-Martinez P., Alkan N. (2016). Induced resistance to control postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 122 82–94. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2016.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Mancini V., Feliziani E., Servili A., Endeshaw S., Neri D. (2016a). Impact of alternative fungicides on grape downy mildew control and vine growth and development. Plant Dis. 100 739–748. 10.1094/PDIS-05-15-0564-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi G., Smilanick J. L., Feliziani E., Droby S. (2016b). Integrated management of postharvest gray mold on fruit crops. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 113 69–76. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra G. M., Figueroa N. E., Poblete L. A., Cherian S., Figueroa C. R. (2016). Effects of preharvest applications of methyl jasmonate and chitosan on postharvest decay, quality and chemical attributes of Fragaria chiloensis fruit. Food Chem. 190 448–453. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.05.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangsuwan J., Pongsapakworawat T., Bangmo P., Sutthasupa S. (2016). Effect of chitosan beads incorporated with lavender or red thyme essential oils in inhibiting Botrytis cinerea and their application in strawberry packaging system. Food Sci. Technol. 74 14–20. 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.07.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmuga Priya D., Suriyaprabha R., Yuvakkumar R., Rajendran V. (2014). Chitosan-incorporated different nanocomposite HPMC films for food preservation. J. Nanopart. Res. 16:2248 10.1007/s11051-014-2248-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X., Cao B., Xu F., Xie S., Yu D., Wang H. (2015). Effect of postharvest application of chitosan combined with clove oil against citrus green mold. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 99 37–43. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.07.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Yang H. (2017). Effect of preharvest chitosan-g-salicylic acid treatment on postharvest table grape quality, shelf life, and resistance to Botrytis cinerea-induced spoilage. Sci. Hortic. 224 367–373. 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.06.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tayel A. A., Moussa S. H., Salem M. F., Mazrou K. E., El-Tras W. F. (2016). Control of citrus molds using bioactive coatings incorporated with fungal chitosan/plant extracts composite. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96 1306–1312. 10.1002/jsfa.7223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treviño-Garza M. Z., García S., Flores-González M., del S., Arévalo-Niño K. (2015). Edible active coatings based on pectin, pullulan, and chitosan increase quality and shelf life of strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa). J. Food Sci. 80 M1823–M1830. 10.1111/1750-3841.12938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela C., Tapia C., López L., Bunger A., Escalona V., Abugoch L. (2015). Effect of edible quinoa protein-chitosan based films on refrigerated strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) quality. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 18 406–411. 10.1016/j.ejbt.2015.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velickova E., Winkelhausen E., Kuzmanova S., Alves V. D., Moldão-Martins M. (2013). Impact of chitosan-beeswax edible coatings on the quality of fresh strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa cv Camarosa) under commercial storage conditions. Food Sci. Technol. 52 80–92. 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waewthongrak W., Pisuchpen S., Leelasuphakul W. (2015). Effect of Bacillus subtilis and chitosan applications on green mould (Penicilium digitatum Sacc.) decay in citrus fruit. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 99 44–49. 10.1016/j.postharvestbio.2014.07.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li B., Zhang X., Peng N., Mei Y., Liang Y. (2017). Low molecular weight chitosan is an effective antifungal agent against Botryosphaeria sp. and preservative agent for pear (Pyrus) fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 95 1135–1143. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.10.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Dai S., Cong X., Liu R., Zhang M. (2017). Succinylated soy protein film coating extended the shelf life of apple fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 41 13024–13034. 10.1111/jfpp.13024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xoca-Orozco L. A., Cuellar-Torres E. A., González-Morales S., Gutiérrez-Martinez P., López-Garcia U., Herrera-Estrella L., et al. (2017). Transcriptomic analysis of avocado Hass (Persea americana Mill) in the interaction system fruit-chitosan- Colletotrichum. Front. Plant Sci. 8:956. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li R., Liu W. (2011). Effects of chitin and its derivative chitosan on postharvest decay of fruits: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12 917–934. 10.3390/ijms12020917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W., Li L., Pan S., Liu M., Zhang W., Liu H., et al. (2017). Controls postharvest decay and elicits defense response in kiwifruit. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 11 1937–1945. 10.1007/s11947-017-1957-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Zhang L., Zeng K. (2016). Efficacy of Pichia membranaefaciens combined with chitosan against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in citrus fruits and possible modes of action. Biol. Control 96 39–47. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]