In recent T-cell AIDS vaccine trials, the vaccines did not prevent HIV-1 infection, although HIV-1-specific T cells were induced in the vaccinated individuals, suggesting that the T cells have a weak ability to suppress HIV-1 replication and fail to recognize circulating HIV-1. We previously demonstrated that the T-cell responses to 10 epitopes were significantly associated with good clinical outcome. However, there is no direct evidence that these T cells have strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication and recognize circulating HIV-1. Here, we demonstrated that the T cells specific for the 10 epitopes had strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. Moreover, the T cells cross-recognized most of the circulating HIV-1 in HIV-1-infected individuals. This study suggests the use of T cells specific for these 10 epitopes in clinical trials of T-cell vaccines as a cure treatment.

KEYWORDS: CTL, HIV-1, HLA, cure, epitope, vaccines

ABSTRACT

HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) with strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication and recognize most circulating HIV-1 strains are candidates for effector T cells for cure treatment and prophylactic AIDS vaccine. Previous studies demonstrated that the existence of CTLs specific for 11 epitopes was significantly associated with good clinical outcomes in Japan, although CTLs specific for one of these epitopes select for escape mutations. However, it remains unknown whether the CTLs specific for the remaining 10 epitopes suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro and recognize circulating HIV-1. Here, we investigated the abilities of these CTLs to suppress HIV-1 replication and to recognize variants in circulating HIV-1. CTL clones specific for 10 epitopes had strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. The ex vivo and in vitro analyses of T-cell responses to variant epitope peptides showed that the T cells specific for 10 epitopes recognized mutant peptides which are detected in 84.1% to 98.8% of the circulating HIV-1 strains found in HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals. In addition, the T cells specific for 5 epitopes well recognized target cells infected with 7 mutant viruses that had been detected in >5% of tested individuals. Taken together, these results suggest that CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes effectively suppress HIV-1 replication and broadly recognize the circulating HIV-1 strains in the HIV-1-infected individuals. This study suggests the use of these T cells in clinical trials.

IMPORTANCE In recent T-cell AIDS vaccine trials, the vaccines did not prevent HIV-1 infection, although HIV-1-specific T cells were induced in the vaccinated individuals, suggesting that the T cells have a weak ability to suppress HIV-1 replication and fail to recognize circulating HIV-1. We previously demonstrated that the T-cell responses to 10 epitopes were significantly associated with good clinical outcome. However, there is no direct evidence that these T cells have strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication and recognize circulating HIV-1. Here, we demonstrated that the T cells specific for the 10 epitopes had strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. Moreover, the T cells cross-recognized most of the circulating HIV-1 in HIV-1-infected individuals. This study suggests the use of T cells specific for these 10 epitopes in clinical trials of T-cell vaccines as a cure treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Previous efforts in HIV-1 vaccine trials to induce effective HIV-1-specific cellular immunity have failed in humans (1, 2), indicating that the HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) induced by these vaccines did not have the ability to prevent HIV-1 infection in the vaccinated individuals. Several studies have emphasized the importance of functional or qualitative properties of HIV-1-specific CTLs for HIV-1 control (3–7). In particular, strong expression of T-bet and effector molecules, such as perforin and granzyme B, was shown to correlate with antiviral efficacy (8–11). A recent study further demonstrated that the induction of CD8+ T cells displaying high levels of T-bet and perforin during the early days following an HIV infection showed a direct benefit on HIV reservoir seeding in vivo (12), suggesting that HIV-1-specific CTLs with high function can be expected to prevent HIV-1 infection and to eradicate the HIV-1 reservoir.

The so-called kick-and-kill treatment, which combines latency-reversing agents with CTLs, is proposed to eradicate latent HIV-1 reservoirs from antiretroviral therapy (ART)-treated individuals (13–20), but it meets several barriers impeding viral eradication, such as the presence of CTL escape mutations in reservoir viruses (21, 22), functional deficits in HIV-specific CTLs (5, 8, 9), and compartmentalization of infected cells in anatomical sites that are poorly accessed by CD8+ T cells (23, 24). The existence of CTL escape mutations in reservoir viruses is a critical barrier for the eradication of latent HIV-1 reservoirs (21). A previous study using a humanized mouse model showed that latent HIV-1 reservoirs were eradicated by CTLs targeting nonmutated epitopes but not by those for mutated ones (21), suggesting that CTLs targeting the conserved regions are candidates for effector T cells in the kick-and-kill treatment.

HLA-B*27- or HLA-B*57-restricted CTLs play a critical role in HIV-1 control in Caucasians and Africans (25, 26). T cells specific for HLA-B*27-restricted Gag KK10 (KRWIILGLNK) and HLA-B*57-restricted Gag TW10 (TSTLQEQIGW) epitopes especially are known to be involved in HIV-1 control. The T-cell response to KK10 was associated with slow progression in individuals with acute and early HIV-1 infection (27). The T-cell response to the 18-mer overlapping peptide containing TW10 was associated with low plasma viral load (pVL) in treatment-naive HLA-B*57+ individuals chronically infected with HIV-1 (28). These studies suggest that T cells specific for these epitopes have strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication in vivo. However, the appearance of the R264K escape mutation selected by CTLs within the KK10 epitope results in an increase in pVL and progression to AIDS in HLA-B*27+ HIV-1-infected individuals (29). On the other hand, HLA-B*57-positive individuals maintain low pVL even after the emergence of the T242N escape mutation selected by CTLs in the TW10 epitope due to low viral fitness of the mutant (30). However, pVL increases in HLA-B*57+ individuals upon the appearance of compensatory mutations, which recover viral fitness caused by the T242 mutation (31). These findings indicate that escape mutations selected by CTLs caused the loss of HIV-1 control in vivo. Thus, T cells restricted by these two protective alleles may not be suitable as effector T cells for T-cell-mediated AIDS vaccines for the prevention of HIV-1 infection and cure.

A previous study demonstrated that the frequency of HIV-1 controllers carrying HLA-B*52 was significantly higher than that of progressors carrying the same allele in Europe, and the association of HLA-B*52 with HIV-1 control was stronger than that of HLA-B*27 (26). In addition, our analyses of HLA alleles and clinical parameters in the Japanese cohort, in which HLA-B*57 and HLA-B*27 are absent, showed that the HLA-B*52:01-C*12:02 haplotype was strongly associated with good clinical outcome (32). These findings together indicate that HLA-B*52:01 is also a protective allele in HIV-1-infected individuals. Our previous study demonstrated that the existence of CTLs specific for 13 Gag and Pol epitopes, including 5 HLA-B*52:01-restricted ones, is strongly associated with good clinical outcomes (plasma viral load and CD4 T-cell counts) in HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals (33, 34), suggesting that these CTLs have a strong ability to suppress HIV-1 replication in vivo. Subsequent studies showed that out of these 13 epitopes, two 11-mer Gag peptides overlapping 8-mer (34) and 9-mer (unpublished data) are not real epitopes or are very weak ones. On the other hand, GagRI8 (HLA-B*52:01 restricted) and PolSV9 (HLA-A*02:06 restricted) had mutations associated with HLA-B*52:01 and -A*02:06, respectively, within these epitopes (35). GagRI8-specific T cells failed to recognize the mutant peptides, whereas PolSV9-specific T cells did effectively recognize them (33). These studies indicated that Gag RI8-specific T cells selected for and caused the accumulation of escape mutants but that PolSV9-specific T cells did not. Thus, CTLs specific for the remaining 10 epitopes may be considered candidates for effector T cells having the ability to suppress most of the circulating HIV-1 strains. However, it remains unknown whether these CTLs broadly recognize circulating HIV-1 and have a strong ability to suppress HIV-1 replication.

In the present study, we first investigated whether CTL clones specific for these 10 epitopes could suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. We next analyzed the ability of these T cells to recognize the epitope variants in circulating HIV-1 strains. The present study clarified the possibility of these T cells as effector T cells for functional cure treatment and development of a prophylactic AIDS vaccine.

RESULTS

Strong ability of CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes to suppress HIV-1 replication.

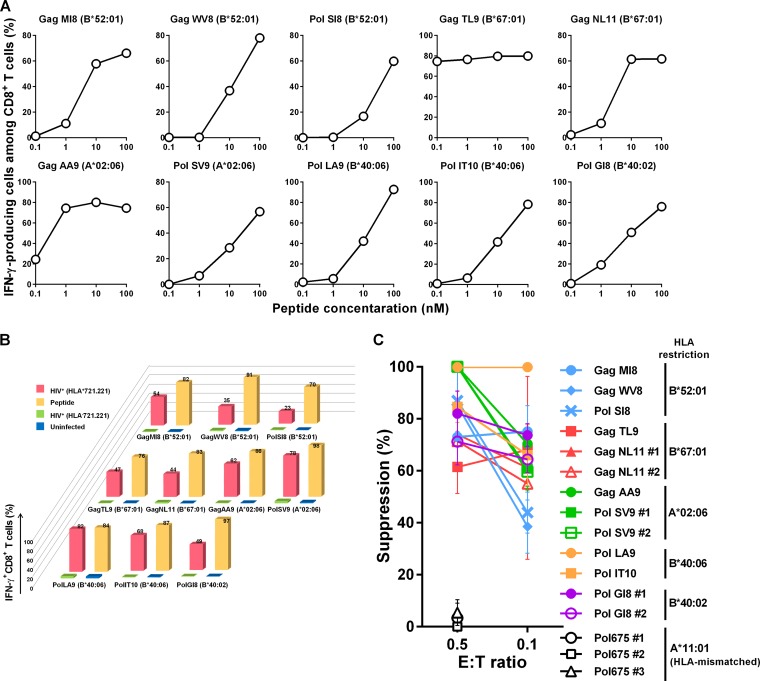

To examine the ability of T cells specific for the 10 epitopes (GagTL9, GagMI8, GagWV8, GagNL11, GagAA9, PolSV9, PolSI8, PolLA9, PolIT10, and PolGI8) to suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro, we investigated whether CTL clones specific for these 10 epitopes could recognize HIV-1-infected cells and suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. We first generated CTL clones specific for these epitopes from HIV-1-infected individuals having these T cells. We selected 1 to 3 T-cell clones for each epitope and analyzed their recognition of peptide-pulsed target cells expressing the corresponding HLA alleles that restrict T-cell responses. All of these CTL clones effectively recognized these target cells. The representative results of T-cell clones for each epitope are presented in Fig. 1A. We investigated whether HIV-1-infected target cells would be recognized by these CTL clones. All of these CTL clones effectively recognized HIV-1-infected CD4+.221 cells expressing the corresponding restriction HLA molecules but not HIV-1-uninfected or HIV-1-infected CD4+.221 cells not expressing HLA (Fig. 1B). We next investigated the ability of these CTL clones to suppress HIV-1 replication by performing a viral suppression assay. All of these CTL clones exhibited a strong ability to suppress HIV-1 replication at low effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (Fig. 1C). These results indicated that the CTL clones effectively recognized HIV-1-infected cells and suppressed HIV-1 replication. Although the data using CTL clones may not always reflect the in vivo situation, these results support the previous finding that CTLs specific for these 10 epitopes can effectively suppress HIV-1 replication in vivo (33).

FIG 1.

Ability of CTL clones specific for 10 HIV-1 epitopes to recognize HIV-1-infected cells and to suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. (A) Recognition of epitope peptides by CTLs specific for the 10 HIV-1 epitopes. The responses of CTL clones specific for the 10 HIV-1 epitopes to 721.221 cells prepulsed with epitope peptides at 0.1 to 100 nM peptide concentrations were analyzed by using the ICS assay. One T-cell clone specific for GagNL11, GagAA9, PolLA9, or PolIT10, 2 clones specific for GagMI8, PolSV9, PolSI8, or PolGI8, and 3 clones specific for GagTL9 or GagWV8 were analyzed. Representative results for the T-cell clones specific for each epitope are shown. (B) Recognition of HIV-1-infected cells by CTL clones specific for 10 HIV-1 epitopes. The 10 HIV-1 epitope-specific CTL clones were stimulated with HIV-1 (NL4-3)-infected 721.221 cells expressing the corresponding HLA or HLA-negative 721.221 cells, and IFN-γ production from the CTL clones was measured by use of the ICS assay. HIV-1-infected cells were measured by flow cytometry using anti-p24 MAb. The proportions of 721.221-B5201, -B6701, -A0206, -B4006, and -B4002 cells infected with NL4-3 were 86.3%, 72.9%, 67.6%, 71.9%, and 51.5%, respectively. One clone specific for GagNL11, GagAA9, PolLA9, or PolIT10, 2 clones specific for GagMI8, PolSV9, PolSI8, or PolGI8, and 3 clones specific for GagTL9 or GagWV8 were analyzed. Representative data for each epitope are shown. (C) Suppression of HIV-1 replication by CTL clones specific for 10 HIV-1 epitopes. Primary CD4+ T cells from donors carrying the corresponding HLA alleles were infected with NL4-3 and then cocultured with epitope-specific CTL clones at E:T ratios of 0.5:1 and 0.1:1. We analyzed the abilities of the 10 clones shown in panels A and B along with those of 3 additional clones specific for GagNL11, PolSV9, or PolGI8 to suppress HIV-1 replication. HLA-A*11:01-restricted Pol675-specific CTL clones were used as negative controls at an E:T ratio of 0.5:1 (open symbols). The percentage of suppression was calculated as (concentration of p24 without CTLs – concentration of p24 with CTLs)/concentration of p24 without CTLs × 100. The data are presented as the means and SD (n = 3).

Variations of the 10 epitopes among circulating HIV-1.

From the previously analyzed HIV-1 sequence data of Japanese individuals chronically infected with HIV-1 (35), we identified the sequences corresponding to these epitopes (294 to 367 individuals for the 10 epitopes) (Table 1). More than 90% of the individuals had the wild-type (WT) sequences for 3 HLA-B*52:01-restricted and 2 HLA-B*67:01-restricted epitopes, whereas 85 to 90% of them had the wild-type sequence for the GagAA9 epitope and PolIT10 epitope. For the PolLA9 epitope, 73.8% of the individuals had the wild-type sequence. On the other hand, PolSV9 and PolGI8 epitopes varied among the individuals. We also analyzed the frequency of individuals having the wild-type sequences among those having the corresponding restriction HLA allele for each epitope. For 2 HLA-B*67:01-restricted and 3 HLA-B*52:01-restricted epitopes, 100% of the HLA-B*67:01+ and >90% of the HLA-B*52:01+ individuals had the wild-type sequences. In HLA-B*40:06+ individuals, 90% and 72.4% had the wild-type sequences for PolLA9 and PolIT10, respectively, whereas 84.9% of HLA-A*02:06+ individuals had the wild-type sequence for GagAA9. PolSV9 and PolGI8 were variable among HLA-A*02:06+ and HLA-B*40:02+ individuals, respectively.

TABLE 1.

HIV-1 sequences corresponding to the 10 epitopes in Japanese individuals chronically infected with HIV-1

| HLA restriction and epitopea | Sequence | Frequency [no. positive/total no. (%)] in: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals | HLA+ individuals | ||

| B*52:01 | |||

| Gag MI8 | MQMLKETI | 328/346 (94.8) | 80/84 (95.2) |

| Gag MI8-6D | -----D-- | 15/346 (4.3) | 3/84 (3.6) |

| Gag MI8-3I | --I----- | 2/346 (0.6) | 1/84 (1.2) |

| Gag WV8 | WMTETLLV | 356/367 (97.0) | 90/93 (96.8) |

| Gag WV8-4D | ---D---- | 8/367 (2.2) | 2/93 (2.2) |

| Pol SI8 | SQYALGII | 306/330 (92.7) | 73/80 (91.3) |

| Pol SI8-8L | -------L | 18/330 (5.5) | 6/80 (7.5) |

| Pol SI8-5I | ----I--- | 3/330 (0.9) | 0/80 (0) |

| B*67:01 | |||

| Gag TL9 | TPQDLNTML | 337/351 (96.0) | 15/15 (100) |

| Gag TL9-3S7L | --S---L-- | 8/351 (2.3) | 0/15 (0) |

| Gag TL9-3A7L | --A---L-- | 2/351 (0.6) | 0/15 (0) |

| Gag NL11 | NPDCKTILKAL | 334/341 (97.9) | 14/14 (100) |

| Gag NL11-6I10S | -----I---S- | 3/341 (0.9) | 0/14 (0) |

| Gag NL11-6L10S | -----L---S- | 2/341 (0.6) | 0/14 (0) |

| A*02:06 | |||

| Gag AA9 | ATLEEMMTA | 317/354 (89.5) | 62/73 (84.9) |

| Gag AA9-2S | -S------- | 13/354 (3.7) | 3/73 (4.1) |

| Gag AA9-8A | -------A- | 12/354 (3.4) | 2/73 (2.7) |

| Gag AA9-8S | -------S- | 6/354 (1.7) | 3/73 (4.1) |

| Gag AA9-1P | P-------- | 2/354 (0.6) | 1/73 (1.4) |

| Pol SV9-5P | ----P---- | 148/308 (48.1) | 8/57 (14.0) |

| Pol SV9 | SQIYAGIKV | 64/308 (20.8) | 5/57 (8.8) |

| Pol SV9-5P9I | ----P---I | 46/308 (14.9) | 25/57 (43.9) |

| Pol SV9-5S | ----S---- | 29/308 (9.4) | 12/57 (21.1) |

| Pol SV9-5P7V | ----P-V-- | 7/308 (2.3) | 3/57 (5.3) |

| Pol SV9-5P8R | ----P--R- | 4/308 (1.3) | 3/57 (5.3) |

| Pol SV9-5P8R9I | ----P--RI | 3/308 (1.0) | 1/57 (1.8) |

| Pol SV9-5T | ----T---- | 2/308 (0.6) | 0/57 (0) |

| B*40:06 | |||

| Pol LA9 | LEGKIILVA | 217/294 (73.8) | 18/20 (90.0) |

| Pol LA9-5V | ----V---- | 45/294 (15.3) | 2/20 (10.0) |

| Pol LA9-7I | ------I-- | 18/294 (6.1) | 0/20 (0) |

| Pol LA9-4Q | ---Q----- | 3/294 (1.0) | 0/20 (0) |

| Pol LA9-5V7M | ----V-M-- | 2/294 (0.7) | 0/20 (0) |

| Pol IT10 | IEAEVIPAET | 261/306 (85.3) | 21/29 (72.4) |

| Pol IT10-1M | M--------- | 32/306 (10.5) | 3/29 (10.3) |

| Pol IT10-1L | L--------- | 6/306 (2.0) | 3/29 (10.3) |

| Pol IT10-7S | ------S--- | 2/306 (0.7) | 1/29 (3.4) |

| B*40:02 | |||

| Pol GI8-5I | ----I--- | 143/320 (44.7) | 20/47 (42.6) |

| Pol GI8 | GERIVDII | 126/320 (39.4) | 19/47 (40.4) |

| Pol GI8-7M | ------M- | 27/320 (8.4) | 4/47 (8.5) |

| Pol GI8-5I7M | ----I-M- | 13/320 (4.1) | 2/47 (4.3) |

| Pol GI8-5I7L | ----I-L- | 4/320 (1.3) | 0/47 (0) |

| Pol GI8-4L5I | ---LI--- | 3/320 (0.9) | 1/47 (2.1) |

Boldface indicates the wild-type epitope.

T-cell recognition of mutant epitopes among HIV-1-infected individuals.

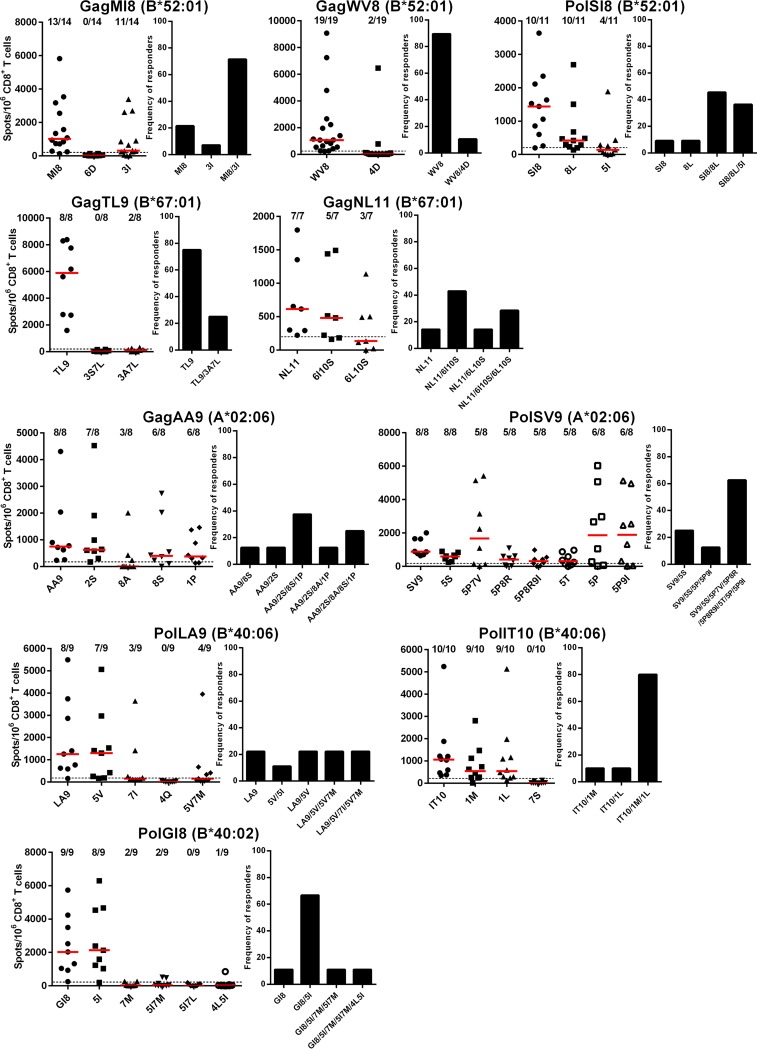

We analyzed T-cell responses to epitope peptides for the 32 circulating mutant viruses by using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay. We selected individuals who had T cells specific for the wild-type peptides. T-cell responses to 10 mutant epitope peptides (GagMI8-6D, GagTL9-3S7L, PolLA9-4Q, PolIT10-7S, PolGI8-5I7L, GagWV8-4D, GagTL9-3A7L, PolGI8-7M, PolGI8-5I7M, and PolGI8-4L5I) were detected in 0 to 25.0% of the individuals tested (Fig. 2), indicating that these 10 mutant epitopes were hardly recognized by T cells in these HIV-1-infected individuals. Of the remaining 22 peptides, 5 mutant epitope peptides elicited T-cell responses in 33.3 to 44.4% of the individuals, and the other 17 peptides did so in 62.5 to 100% of the individuals (Fig. 2), suggesting that these mutant epitopes were frequently cross-recognized by wild-type epitope-specific T cells or recognized by mutant epitope-specific T cells in these individuals.

FIG 2.

T-cell responses to wild-type and mutant epitope peptides in HIV-1-infected individuals. T-cell responses to wild-type and mutant epitope peptides in HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals who had T-cell responses to wild-type epitope peptides were analyzed by use of the IFN-γ ELISpot assay. The values in each figure indicate the number of responders to each epitope/number of individuals tested (graphs on the left). The dotted line at 200 spots/106 CD8+ T cells represents the threshold for a positive response (graphs on the left). To evaluate the overall cross-reactive responses of T cells to wild-type and/or mutant peptides in the individuals tested, we calculated the frequencies of responders to at least 1 peptide out of the wild-type and mutant ones for each epitope (graphs on the right).

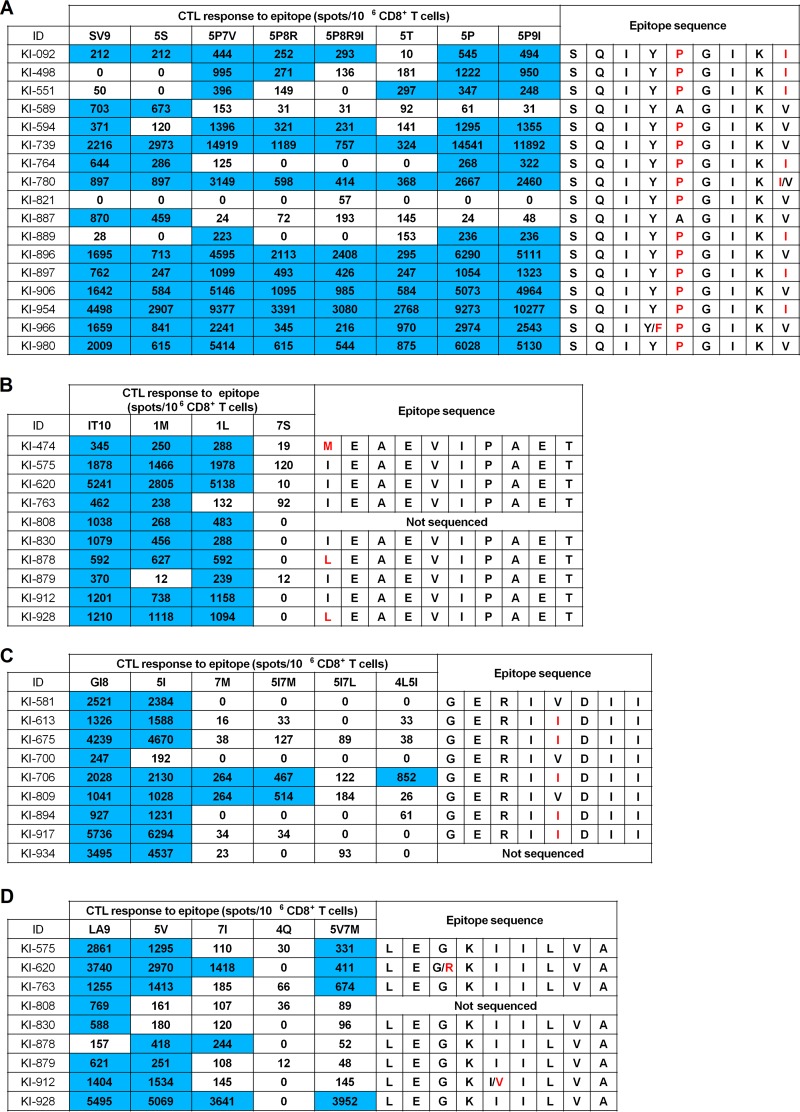

PolSV9 had several variations, especially at positions 5 and 9. SV9-5P and SV9-5P9I were frequently detected in our cohort, although other minor mutations (SV9-5S, -5T, -5P7V, -5P8R, and -5P8R9I) were also found. Although most of the individuals showed T-cell responses to these mutant peptides, 2 individuals (KI-589 and KI-887) had T-cell responses to SV9 but not to SV9-5P/5P9I. In contrast, in 3 individuals (KI-498, KI-551, and KI-889), T cells responded to SV9-5P/5P9I but not to SV9 (Fig. 3A). The former and the latter groups of individuals had been infected with wild-type and 5P mutant HIV-1, respectively. These results suggest that both SV9 and SV9-5P could be recognized as independent epitopes and elicit CTLs specific for these epitopes. In addition, individuals who had been infected with 5P mutant HIV-1 showed diverse responses to the mutant peptides (Fig. 3A). PolIT10 and PolGI8 also had variations, especially at positions 1 and 5, respectively. PolIT10 had 2 variations at position 1 in our cohort. IT10-1M and -1L were detected in >10% of all individuals and those with HLA-B*40:06. We analyzed T-cell responses to these 2 mutant peptides in the HLA-B*40:06+ individuals who had T-cell responses to IT10 peptide. Most of these individuals showed T-cell responses to IT10-1M and -1L peptides (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the mutant epitopes were cross-recognized by PolIT10-specific T cells. Since KI-474 or KI-878 and KI-928 were infected with IT10-1M or -1L mutants, (Fig. 3B), it remains possible that T cells specific for each mutant are also elicited in these 3 individuals. At position 5 of PolGI8, I and V were detected in approximately 40% of the individuals. We analyzed T-cell responses to GI8-5I peptide in HLA-B*40:02+ individuals who had been infected with PolGI8 or PolGI8-5I virus and showed T-cell responses to GI8 peptide. All of these individuals showed T-cell responses to GI8-5I peptides (Fig. 3C), suggesting that both the wild-type and mutant epitopes were cross-recognized by PolGI8-spepcific or PolGI8-5I-specific T cells. This epitope has an HLA-B*40:06-associated mutation, 7M (35). Out of 8 individuals having T-cell responses to GI8-5I, 6 of them failed to recognize GI8-5I7M (Fig. 3C), suggesting that this mutation affected the recognition by GI8 or GI8-5I-specific T cells. PolLA9 had variations at positions 5 and 7. LA9-5V and LA9-7I were detected at approximately 15% and 6%, respectively, in these individuals. We analyzed T-cell responses to the 2 mutant peptides in HLA-B*40:06+ individuals who had T-cell responses to LA9 peptide. Most of these individuals showed responses to LA9-5V peptide, whereas 3 of the 9 individuals exhibited responses to LA9-7I (Fig. 3D), suggesting that these mutant epitopes were cross-recognized by PolLA9-specific T cells in some of the individuals. Both wild-type and 5V mutant viruses were detected in KI-912 (Fig. 3D). These findings suggest that T cells specific for the 5V mutant can be elicited in this individual.

FIG 3.

T-cell responses to wild-type or mutant epitopes and HIV-1 sequences within the epitopes in HIV-1-infected individuals. T-cell responses to wild-type and mutant epitope peptides (A, PolSV9; B, PolIT10; C, PolGI8; D, PolLA9) were analyzed in HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals by performing the IFN-γ ELISpot assay. HIV-1 sequences corresponding to the epitopes were also analyzed. The red letters and the blue shading indicate mutations and positive responses in ELISpot assay (>200 spots/106 CD8+ T cells), respectively. HLA-A*02:06-binding peptides have 2 anchor residues, V/Q at position 2 and V at the C terminus (59). HLA-B*40:02- and HLA-B*40:06-binding peptides have 2 anchor residues, E at position 2 and V at the C terminus (60).

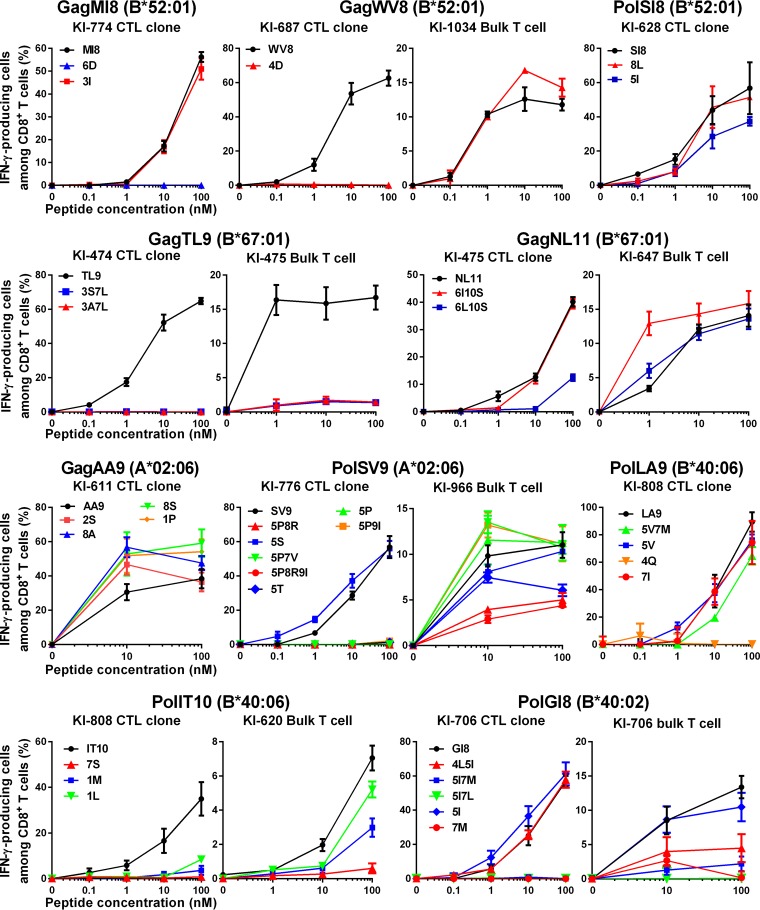

Quantitative analysis of recognition of mutant epitope peptides by CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes.

We next quantified the T-cell recognition of the mutant epitopes by performing the intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay, using T-cell clones or bulk T cells specific for the 10 epitopes (Fig. 4). In addition to the T-cell clones specific for these 10 epitopes, we also used bulk T cells specific for 6 epitopes from individuals who showed T-cell responses to the mutant peptides in the ELISpot assay. All of the T-cell clones recognized target cells pulsed with the corresponding epitope peptides at a concentration of >10 nM (Fig. 1A). Therefore, we defined a positive response to mutant peptides as T-cell responses greater than 30% of that to the wild-type peptides at 10 nM. We first analyzed the 10 mutant peptides that elicited responses in 0 to 25.0% of the individuals according to the results of the ELISpot assay. Positive T-cell recognition for 5 mutant epitope peptides (MI8-6D, TL9-3S7L, LA9-4Q, IT10-7S, and GI8-5I7L) was not observed (Fig. 4), supporting the results that the responses to these mutant peptides had not been detected in any individuals tested by the ELISpot assay. Among the other 5 mutant epitope peptides (WV8-4D, TL9-3A7L, GI8-4L5I, GI8-7M, and GI8-5I7M) to which T-cell responses were detected in only 10.5 to 25.0% of the individuals by the ELISpot assay, positive responses of bulk T cells and/or CTL clones to WV8-4D and GI8-4L5I peptides were observed, whereas the responses of T-cell clones and bulk T cells to 3 peptides (TL9-3A7L, GI8-7M, and GI8-5I7M) were not detected (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Recognition of mutant epitope peptides by CTL clones and/or CD8+ T cells specific for the 10 epitopes. The responses of CTL clones or bulk T cells specific for the 10 epitopes to wild-type or mutant peptide-prepulsed C1R cells expressing the corresponding HLA allele were analyzed by use of the ICS assay. The CTL clones shown in Fig. 1A and B, except for WV8, were used in this analysis. T-cell clones newly established from KI-687 were used for the analysis of the WV8 epitope. The results are shown as means and SD from triplicate assays.

We next analyzed the remaining 22 mutant peptides to which the responses were detected in 33.3 to 100% of the individuals tested by the ELISpot assay. Positive responses of T-cell clones and/or bulk T cells to all of these 22 mutant peptides were observed (Fig. 4). These results indicate that T cells specific for the 10 epitopes broadly cross-recognize circulating HIV-1, and these T cells are predominantly elicited in HIV-1-infected individuals carrying the corresponding HLA alleles.

Effective recognition of cells infected with HIV-1 mutant viruses by epitope-specific CTLs.

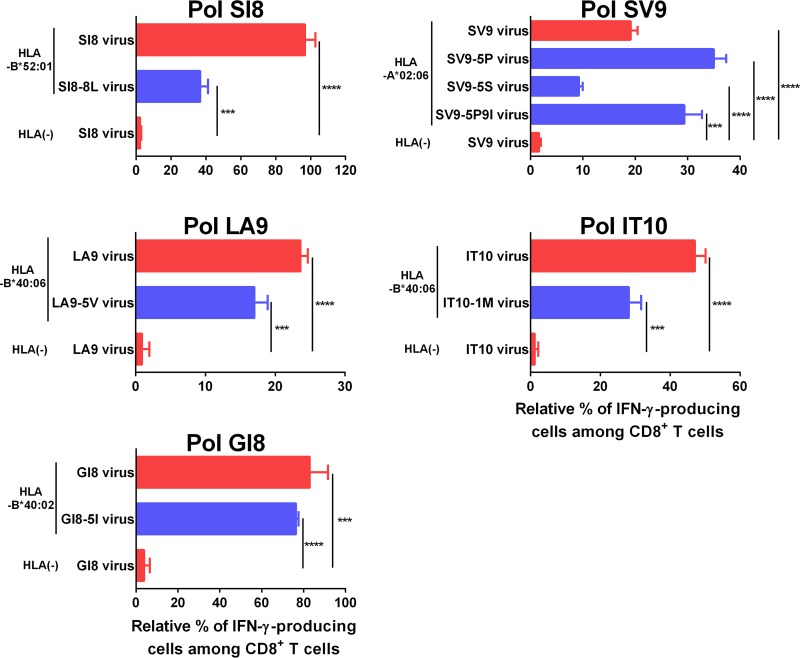

It is well known that some mutations affect epitope presentation on HIV-1-infected cells even when they do not affect the binding of peptides to HLA molecules or the affinity for the T-cell receptor. We therefore investigated whether T cells could recognize target cells infected with HIV-1 bearing mutations. We selected 7 mutations (SV9-5S, SV9-5P, SV9-5P9I, SI8-8L, LA9-5V, IT10-1M, and GI8-5I) that had been detected in >5% of the individuals tested, with the corresponding peptides recognized by T cells (Fig. 2 and 4). The T cells specific for 5 epitopes well recognized target cells infected with the corresponding mutant viruses (Fig. 5), although some of these T cells recognized significantly fewer target cells infected with the mutant viruses than those infected with wild-type virus (Fig. 5). These results suggest that these specific T cells could recognize the target cells infected with these mutant viruses.

FIG 5.

Recognition of mutant virus-infected cells by CD8+ T cells specific for 5 epitopes. The responses of CTL clones or bulk T cells specific for 5 epitopes (SI8, SV9, LA9, IT10, and GI8) to HLA-positive 721.221 cells infected with wild-type or mutant viruses were analyzed by performing the ICS assay. The CTL clones specific for SI8, LA9, and GI8 were established from KI-628, KI-808, and KI-706, respectively. The CTL clones shown in Fig. 1A and B were used for this analysis. The bulk T cells specific for SV9 and IT10 were established from KI-966 and KI-620, respectively. The bulk T cells shown in Fig. 4 were used for this analysis. The frequencies of p24 antigen-positive cells among stimulator cells were the following: 721.221-B5201 infected with NL4-3, NL4-3PolSI8-8L, and 721.221 infected with NL4-3, 35%, 32%, and 33%, respectively; 721.221-A0206 cells infected with NL4-3, NL4-3PolSV9-5P, NL4-3PolSV9-5S, NL4-3PolSV9-5P9I, and 721.221 infected with NL4-3, 44%, 43%, 46%, 42%, and 33%, respectively; 721.221-B4006 infected with NL4-3LA9-5I (wild-type), NL4-3(LA9-5V), and 721.221 infected with NL4-3LA9-5I, 60%, 57%, and 60%, respectively; 721.221-B4006 infected with NL4-3, NL4-3IT10-1M, and 721.221 infected with NL4-3, 60%, 56%, and 56%, respectively; 721.221-B4002 infected with NL4-3, NL4-3GI8-5I, and 721.221 infected with NL4-3, 32%, 30%, and 39%, respectively. To normalize the CD8+ T-cell responses to infected cells, the relative percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells among CD8+ T cells was calculated as (% of IFN-γ-producing cells among CD8+ T cells in response to infected cells − % of IFN-γ-producing cells among CD8+ T cells in response to uninfected cells)/(% of p24 antigen-positive cells among infected cells) × 100. The results are shown as means and SD from triplicate assays. Statistical analysis was performed by using the unpaired t test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

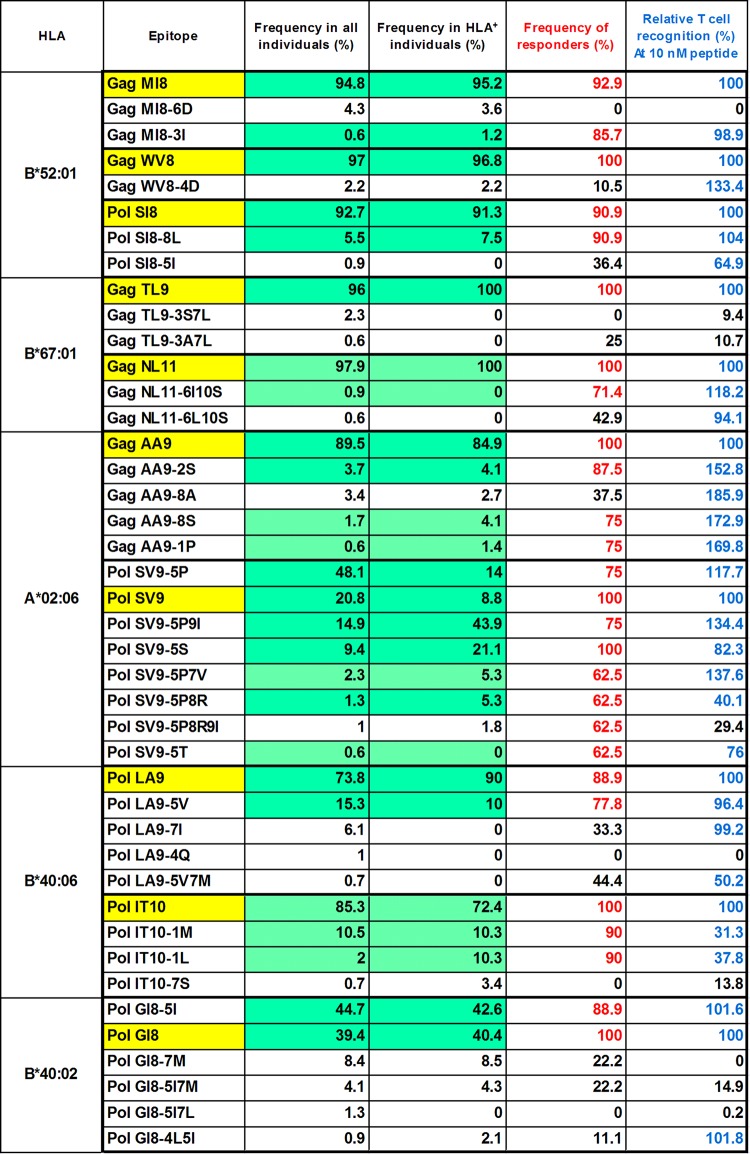

Frequency of circulating HIV-1 strains recognized by CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes.

The T cells specific for the 4 epitopes (PolSI8, PolSV9, PolLA9, and PolIT10) effectively recognized the target cells infected with 4 HIV-1 mutant viruses, although they did so significantly less effectively than those infected with the wild-type virus (Fig. 5). Only IT10-specific CTLs recognized IT10-1M mutant peptide at approximately 30% of the level of IT10 wild-type peptides at 10 nM, whereas the other CTLs evenly recognized both mutant and wild-type peptides (Fig. 4). These results suggest that HIV-1-specific T cells recognize target cells infected with mutant viruses when the responses of HIV-1-specific T cells to these mutant peptides were >30% of the responses to the wild-type peptide at 10 nM. We therefore accepted both of the following criteria to evaluate the frequency of circulating HIV-1 strains recognized by CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes among HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals: (i) >30% responsiveness of the specific T cells to mutant peptides compared to that to the wild-type peptide at 10 nM peptide, and (ii) a frequency of >60% responders among individuals having the specific HLA alleles.

We summarized the frequencies of circulating HIV-1 strains recognized by T cells specific for each epitope based on the criteria described above (Fig. 6). The responses to 16 mutant peptides satisfied these criteria. Our results indicated that these T cells could recognize 84.1% to 98.8% (MI8, 95.4%; WV8, 97.0%; SI8, 98.2%; TL9, 96.0%; NL11, 98.8%; AA9, 95.5%; SV9, 96.8%; LA9, 89.1%; IT10, 97.8%; GI8, 84.1%) of the circulating HIV-1 strains in Japanese individuals and 83.0% to 100% (MI8, 96.4%; WV8, 96.8%; SI8, 98.8%; TL9, 100%; NL11, 100%; AA9, 94.5%; SV9, 98.4%; LA9, 100%; IT10, 93.0%; GI8, 83.0%) of the circulating HIV-1 strains in individuals having specific HLA alleles. Thus, these CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes could recognize most of the circulating HIV-1 strains.

FIG 6.

Summary of T-cell responses to wild-type and mutant epitopes. We summarized the frequencies of the responders to wild-type and mutant epitopes in HIV-1-infected individuals and relative T-cell responsiveness to mutant peptides compared with that of wild-type ones. The wild-type epitopes are highlighted in yellow. The percentages marked in red represent the frequencies of >60% responders to each epitope among HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals. These percentages are calculated from the frequencies of responders to each epitope shown in Fig. 2. Blue indicates >30% of responsiveness of the specific T cells to mutant peptide compared to that of wild-type peptide at the 10 nM peptide concentration. The responsiveness is calculated for Fig. 4 as % IFN-γ-producing cells among CD8+ T cells in the response to each mutant epitope at 10 nM/% IFN-γ-producing cells among CD8+ T cells in the response to WT epitope at 10 nM × 100. The T-cell responses highlighted in green satisfied both criteria described above.

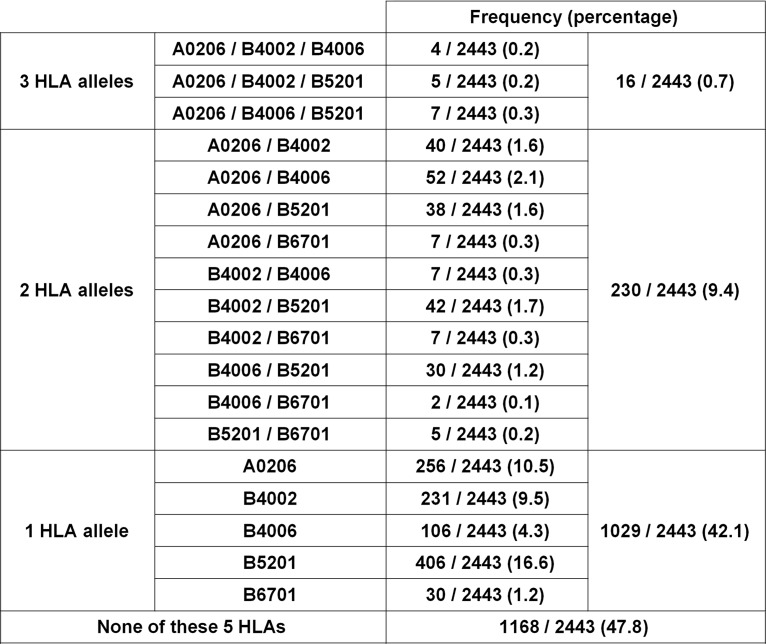

Frequency of HIV-1-infected individuals having HLA alleles restricting the 10 epitopes.

We analyzed the HLA type of 2,443 HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals and identified the frequency of individuals having at least 1 of the 5 HLA alleles that restricted the responses of T cells to the 10 epitopes (Fig. 7). Among these individuals, 52.2% had at least 1 of these 5 HLA alleles. Three, 2, and 1 HLA alleles were found in 0.7, 9.4, and 42.1%, respectively, of these individuals. Two epitopes were restricted by HLA-A*02:06, -B*40:06, or -B*67:01, whereas 3 and 1 epitopes were restricted by HLA-B*52:01 and -B*40:02, respectively. These results indicate that >50% of the Japanese individuals have HLA alleles restricting T cells specific for these epitopes. These T cells might be useful for functional cure treatment and development of a prophylactic AIDS vaccine for the Japanese population.

FIG 7.

Frequencies of HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals having HLA restriction molecules for the epitopes HLA-A*02:06, -B*40:02, -B*40:06, -B*52:01, and -B*67:01. HLA types of 2,443 HIV-infected individuals were determined by standard sequence-based genotyping.

DISCUSSION

Although T cells specific for the Gag KK10 epitope have a strong ability to suppress HIV-1 in HLA-B*27+ individuals (27), the R264K escape mutation selected by the KK10-specific T cells results in progression to AIDS in B*27+ individuals (29). On the other hand, previous studies demonstrated that Gag TW10-specific T cells from HLA-B*57+ elite controllers cross-recognize the escape mutant peptides (36–38). In addition, TW10-specific T cells suppress the replication of wild-type and escape mutant viruses in B*57+ elite controllers (39). These findings suggest that some B*57+ individuals maintain control of HIV-1 by these T cells even after the emergence of the escape mutants. If such TW10-specific T cells are elicited in B*57+ individuals, they would be good effector T cells for cure treatment. A recent study demonstrated that the T-cell clones specific for 3 epitopes cross-recognized some mutant epitope peptides derived from reservoir viruses detected in resting CD4+ T cells from one ART-treated individual (15), but it remains unclear whether these mutants are detected at the population level. The other study showed that variant epitope peptides in 6 reported epitopes were cross-recognized by the T cells in HIV-1-infected individuals, although it has not been demonstrated in this study whether the T cells specific to these 6 epitope have strong abilities to suppress HIV-1 replication (40).

In the present study, we selected T cells specific for 10 epitopes to characterize their ability to suppress HIV-1 in vitro and to cross-recognize the circulating viruses in an HIV-1-infected Japanese cohort. The 10 epitopes analyzed in the present study were previously identified by using overlapping peptides covering the consensus sequence of the HIV-1 subtype B viruses (33). The T cells specific for these epitopes had a strong ability to suppress HIV-1 in HIV-1-infected individuals and did not select for escape mutants (33). The sequences of 7 epitopes were found at a frequency of >85% among circulating HIV-1 strains in Japan, indicating that these epitopes were conserved among circulating HIV-1 subtype B viruses in Japan. On the other hand, variations were found in 3 epitopes, SV9, GI8, and LA9, although most of them were recognized by T cells specific for these epitopes. Thus, these were conserved or cross-recognized T-cell epitopes. In addition, the present study showed that CTLs specific for these epitopes had a strong ability to suppress HIV-1 replication in vitro. A previous study showed that the existence of T cells specific for these 10 epitopes is significantly associated with good clinical outcomes (33). Thus, these T cells had the ability to effectively suppress HIV-1 replication in vivo and in vitro. Overall, they would be expected to be useful as effector T cells for functional curative treatment or for prevention of HIV-1 infection in Japanese individuals. These epitopes were presented by 5 HLA alleles covering approximately 50% of HIV-1-infected Japanese, suggesting that these T cells would be useful in at least half of Japanese individuals. These HLA alleles are more frequently found in Asians than in Caucasians and Africans. HLA-A*02:06 is found in approximately 10% of Chinese and Vietnamese, whereas HLA-B*52:01 and HLA-B*40:06 are present in approximately 13% of Indian and 7 to 8% of Chinese individuals (41–46). Thus, T cells specific for the epitopes restricted by HLA-A*02:06, HLA-B*52:01, and HLA-B*40:06 may also be useful in these Asian countries where the HIV-1 subtype B virus is circulating. Since the subtype A/E and C viruses are circulating in southeast Asian countries and India, respectively, further studies to investigate whether the same T cells can suppress the replication of these subtype viruses and to identify such T cells restricted by other HLAs are necessary for coverage of more individuals in Asian countries.

We found several variants in HLA-A*02:06-restricted SV9, HLA-B*40:02-restricted GI8, HLA-B*40:06-restricted PolLA9, and HLA-B*40:06-restricted PolIT10 epitopes. However, these mutant peptides were cross-recognized by T cells specific for each epitope ex vivo (Fig. 2) and in vitro (Fig. 4). The T cells specific for these 4 epitopes also recognized target cells infected with the mutant virus (Fig. 5). These T cells cross-recognized the mutant peptide at a level similar to that for the wild-type peptides (Fig. 4) but recognized the mutant virus-infected target cells to a lesser degree than wild-type virus-infected ones (Fig. 5). Thus, since the mutant HIV-1 could be cross-recognized by these T cells, they would be expected to eradicate latently infected HIV-1 mutants and to prevent infections by mutant viruses. However, the efficacy of these T cells to cross-recognize mutant virus-infected cells may depend on the nature of the mutations.

T cells specific for these epitopes were detected by ex vivo ELISpot assay in approximately 20 to 50% of HIV-1-infected Japanese individuals having HLA alleles restricting T-cell responses to these epitopes (33). However, this may be an underestimate. The frequency may be higher if HIV-1-specific T cells are measured by tetramers, since the ELISpot assay is less sensitive than the tetramer-binding one (47). The frequency of HIV-1-specific T cells is much lower in ART patients than in treatment-naïve ones (48–51). ART patients still retain HIV-1-specific memory T cells even after their effector T cells have disappeared. Such memory T cells will be useful as the source of effector T cells. Effective induction of effector T cells from memory T cells will be necessary for functional cure treatment.

In the present study, we demonstrated that CTLs specific for the 10 epitopes had strong ability to suppress HIV-1 replication and could recognize most of the circulating HIV-1 in Japan. These T cells would be useful for further studies to evaluate them as effector T cells to eradicate latent HIV-1 in Japanese patients and to prevent HIV-1 infections in Japan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Antiretroviral therapy-naïve Japanese individuals chronically infected with subtype B HIV-1 were recruited from the AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine and Kumamoto University. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated from whole blood. HLA types of HIV-infected individuals were determined by standard sequence-based genotyping. The pVLs of the individuals at their first visit were measured by using a Cobas TaqMan HIV-1 real-time PCR version 2.0 assay (Roche Diagnostics, NJ, USA). Median pVLs of HLA-B*52:01-, HLA-A*02:06-, HLA-B*40:02-, HLA-B*40:06-, HLA-B*67:01-positive samples, and all individuals in this cohort, were 13,500, 22,500, 20,000, 13,000, 9,450, and 25,000 copies/ml, respectively.

Peptides.

Epitope peptides were synthesized by an automated multiple peptide synthesizer and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Their purity was examined by HPLC and mass spectrometry. Peptides with more than 90% purity were used in this study.

Cells.

C1R cells expressing HLA-B*52:01, -B*67:01, -A*02:06, -B*40:06, or -B*40:02 and 721.221 cells expressing each of these alleles and CD4 were previously generated (33, 52–54). These cells were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and 0.15 mg/ml hygromycin B.

IFN-γ ELISpot assays.

Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) ELISpot assays were performed as previously described (33). To standardize the number of spots to spots/106 CD8+ T cells, we measured the frequency of CD8+ T cells among PBMCs using flow cytometry. In the next step, 100,000 PBMCs from each individual were plated in each well in the ELISpot plate with a concentration of 100 nM each of epitope peptide. We calculated the number of CD8+ T cells plated in each well containing 100,000 PBMCs by using the frequency of CD8+ T cells among PBMCs and determined spots/106 CD8+ T cells in each well (33). The number of spots for each peptide-specific T cell response was finally calculated by subtracting the number of spots in wells without peptides. The mean + 3 standard deviations (SD) spot number of samples from 13 HIV-1-naïve individuals for the peptides was 162 spots/106 CD8+ T cells. Therefore, we defined >200 spots/106 CD8+ T cells as positive responses.

Generation of epitope-specific CTL clones.

CTL clones specific for 10 epitopes were generated from the epitope-specific bulk T cells by limiting dilution in 96-well, U-bottomed plates, together with 200 μl of cloning mixture of 2 × 105 irradiated allogeneic PBMCs from healthy donors, 2 × 104 irradiated 721.221 cells expressing each HLA molecule, and epitope peptides at a concentration of 100 nM in RPMI 1640 containing fetal calf serum, 200 U/ml recombinant interleukin-2, and 2.5% phytohemagglutinin (PHA). CTL clones specific for each epitope were established from HIV-1-infected individuals having the specific CTLs (55). HLA-B*52:01/MI8-, HLA-B*52:01/WV8-, and HLA-B*52:01/SI8-specific T cell clones were generated from KI-774, who had been infected with wild-type virus, from KI-108 (WT)/KI-687 (WT), and from KI-628 (WT), respectively; HLA-B*67:01/TL9- and HLA-B*67:01/NL11-specific T cell clones from KI-474 (WT) and KI-475 (WT), respectively; HLA-A*02:06/AA9- and HLA-A*02:06/SV9-specific T cell clones from KI-611 (WT) and KI-776 (WT), respectively; HLA-B*40:06/LA9- and HLA-B*40:06/IT10-specific T cell clones from KI-808 (autologous virus not sequenced); and HLA-B*40:02/GI8-specific T cell clones from KI-706, infected with the mutant virus having GI8-5I.

HIV-1 mutant strains.

Seven HIV-1 mutations, Pol-A427P (GCA to CCA), Pol-A427S (GCA to TCA), Pol-A427P-V431I (GTA to ATA), Pol-I661L (ATT to CTT), Pol-V787I (GTT to ATT), Pol-I799M (ATA to ATG), and Pol-V916I (GTA to ATA), were engineered into NL4-3 plasmids by overlap extension PCR to generate the corresponding mutant strains.

ICS assay.

C1R and 721.221 cells prepulsed with each epitope peptide or 721.221 cells infected with the NL4-3 strain were cocultured with HIV-1-specific bulk-cultured T cells or CTL clones for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) was added and the cells were then incubated further for 4 h. The cells next were stained with allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (MAb; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and then fixed (4% paraformaldehyde), rendered permeable (0.1% saponin), and intracellularly stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-IFN-γ MAb (BD Biosciences, CA). Data were analyzed with a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, CA).

HIV-1 replication suppression assay.

The ability of HIV-1-specific CTLs to suppress HIV-1 replication was examined as previously described (56–58). CD4+ T cells isolated from PBMCs of healthy donors carrying each restriction HLA were infected with NL4-3, and then these cells were cocultured with epitope-specific CTL clones at E:T ratios of 0.5:1 or 0.1:1. On day 5 to 6 postinfection, the concentration of p24 antigen in the culture supernatant was measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; HIV-1-p24-Ag ELISA kit; ZeptoMetrix, USA). Percent suppression was calculated as (concentration of p24 without the CTLs – concentration of p24 with the CTLs)/concentration of p24 without the CTLs × 100.

Bulk sequencing of autologous virus.

Bulk sequencing of autologous plasma viral RNA from HIV-1-infected patients was performed as described previously (35). The bulk sequencing is generally limited to detecting minor populations (<30%) of viruses. The HIV-1 gag, pol, and nef sequences from most of the individuals analyzed in the present study had been determined in our previous study (35).

Statistical analysis.

For the comparison of 2 groups, the unpaired t test was performed.

Accession number(s).

The accession number for the sequence of autologous virus from KI-887 is LC427217. Numbers in the case of other individuals were given in our previous study (35).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants-in-aid (15fk0410019h0001, 16fk0410202h0002, and 17fk0410302h0003) for AIDS Research from AMED and by grants-in-aid (26293240, 15K19588, and 17K10021) for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. We have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, Karuna ST, Mulligan MJ, Grove D, Koblin BA, Buchbinder SP, Keefer MC, Tomaras GD, Frahm N, Hural J, Anude C, Graham BS, Enama ME, Adams E, DeJesus E, Novak RM, Frank I, Bentley C, Ramirez S, Fu R, Koup RA, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Montefiori DC, Kublin J, McElrath MJ, Corey L, Gilbert PB. 2013. Efficacy trial of a DNA/rAd5 HIV-1 preventive vaccine. N Engl J Med 369:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, Gilbert PB, Lama JR, Marmor M, Del Rio C, McElrath MJ, Casimiro DR, Gottesdiener KM, Chodakewitz JA, Corey L, Robertson MN. 2008. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 372:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almeida JR, Price DA, Papagno L, Arkoub ZA, Sauce D, Bornstein E, Asher TE, Samri A, Schnuriger A, Theodorou I, Costagliola D, Rouzioux C, Agut H, Marcelin AG, Douek D, Autran B, Appay V. 2007. Superior control of HIV-1 replication by CD8+ T cells is reflected by their avidity, polyfunctionality, and clonal turnover. J Exp Med 204:2473–2485. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betts MR, Nason MC, West SM, De Rosa SC, Migueles SA, Abraham J, Lederman MM, Benito JM, Goepfert PA, Connors M, Roederer M, Koup RA. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107:4781–4789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migueles SA, Laborico AC, Shupert WL, Sabbaghian MS, Rabin R, Hallahan CW, Van Baarle D, Kostense S, Miedema F, McLaughlin M, Ehler L, Metcalf J, Liu S, Connors M. 2002. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat Immunol 3:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/ni845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Migueles SA, Osborne CM, Royce C, Compton AA, Joshi RP, Weeks KA, Rood JE, Berkley AM, Sacha JB, Cogliano-Shutta NA, Lloyd M, Roby G, Kwan R, McLaughlin M, Stallings S, Rehm C, O'Shea MA, Mican J, Packard BZ, Komoriya A, Palmer S, Wiegand AP, Maldarelli F, Coffin JM, Mellors JW, Hallahan CW, Follman DA, Connors M. 2008. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity 29:1009–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saez-Cirion A, Lacabaratz C, Lambotte O, Versmisse P, Urrutia A, Boufassa F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Delfraissy JF, Sinet M, Pancino G, Venet A. 2007. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:6776–6781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611244104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hersperger AR, Martin JN, Shin LY, Sheth PM, Kovacs CM, Cosma GL, Makedonas G, Pereyra F, Walker BD, Kaul R, Deeks SG, Betts MR. 2011. Increased HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell cytotoxic potential in HIV elite controllers is associated with T-bet expression. Blood 117:3799–3808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersperger AR, Pereyra F, Nason M, Demers K, Sheth P, Shin LY, Kovacs CM, Rodriguez B, Sieg SF, Teixeira-Johnson L, Gudonis D, Goepfert PA, Lederman MM, Frank I, Makedonas G, Kaul R, Walker BD, Betts MR. 2010. Perforin expression directly ex vivo by HIV-specific CD8 T-cells is a correlate of HIV elite control. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000917. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue FY, Cohen JC, Ho M, Rahman AK, Liu J, Mujib S, Saiyed A, Hundal S, Khozin A, Bonner P, Liu D, Benko E, Kovacs C, Ostrowski M. 2017. HIV-specific granzyme B-secreting but not gamma interferon-secreting T cells are associated with reduced viral reservoirs in early HIV infection. J Virol 91:e02233-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02233-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Ndhlovu ZM, Liu D, Porter LC, Fang JW, Darko S, Brockman MA, Miura T, Brumme ZL, Schneidewind A, Piechocka-Trocha A, Cesa KT, Sela J, Cung TD, Toth I, Pereyra F, Yu XG, Douek DC, Kaufmann DE, Allen TM, Walker BD. 2012. TCR clonotypes modulate the protective effect of HLA class I molecules in HIV-1 infection. Nat Immunol 13:691–700. doi: 10.1038/ni.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takata H, Buranapraditkun S, Kessing C, Fletcher JL, Muir R, Tardif V, Cartwright P, Vandergeeten C, Bakeman W, Nichols CN, Pinyakorn S, Hansasuta P, Kroon E, Chalermchai T, O'Connell R, Kim J, Phanuphak N, Robb ML, Michael NL, Chomont N, Haddad EK, Ananworanich J, Trautmann L. 2017. Delayed differentiation of potent effector CD8(+) T cells reducing viremia and reservoir seeding in acute HIV infection. Sci Transl Med 9:eaag1809. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan L, Deng K, Shroff NS, Durand CM, Rabi SA, Yang HC, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Blankson JN, Siliciano RF. 2012. Stimulation of HIV-1-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes facilitates elimination of latent viral reservoir after virus reactivation. Immunity 36:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barouch DH, Deeks SG. 2014. Immunologic strategies for HIV-1 remission and eradication. Science 345:169–174. doi: 10.1126/science.1255512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang SH, Ren Y, Thomas AS, Chan D, Mueller S, Ward AR, Patel S, Bollard CM, Cruz CR, Karandish S, Truong R, Macedo AB, Bosque A, Kovacs C, Benko E, Piechocka-Trocha A, Wong H, Jeng E, Nixon DF, Ho YC, Siliciano RF, Walker BD, Jones RB. 2017. Latent HIV reservoirs exhibit inherent resistance to elimination by CD8+ T cells. J Clin Investig 128:876–889. doi: 10.1172/JCI97555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RB, Mueller S, O’Connor R, Rimpel K, Sloan DD, Karel D, Wong HC, Jeng EK, Thomas AS, Whitney JB, Lim S-Y, Kovacs C, Benko E, Karandish S, Huang S-H, Buzon MJ, Lichterfeld M, Irrinki A, Murry JP, Tsai A, Yu H, Geleziunas R, Trocha A, Ostrowski MA, Irvine DJ, Walker BD. 2016. A subset of latency-reversing agents expose HIV-infected resting CD4+ T-cells to recognition by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker-Sperling VE, Pohlmeyer CW, Tarwater PM, Blankson JN. 2016. The effect of latency reversal agents on primary CD8+ T cells: implications for shock and kill strategies for human immunodeficiency virus eradication. EBioMedicine 8:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones RB, O'Connor R, Mueller S, Foley M, Szeto GL, Karel D, Lichterfeld M, Kovacs C, Ostrowski MA, Trocha A, Irvine DJ, Walker BD. 2014. Histone deacetylase inhibitors impair the elimination of HIV-infected cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clutton G, Xu Y, Baldoni PL, Mollan KR, Kirchherr J, Newhard W, Cox K, Kuruc JD, Kashuba A, Barnard R, Archin N, Gay CL, Hudgens MG, Margolis DM, Goonetilleke N. 2016. The differential short- and long-term effects of HIV-1 latency-reversing agents on T cell function. Sci Rep 6:30749. doi: 10.1038/srep30749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung JA, Sholtis K, Kirchherr J, Kuruc JD, Gay CL, Nordstrom JL, Bollard CM, Archin NM, Margolis DM. 2017. Vorinostat renders the replication-competent latent reservoir of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vulnerable to clearance by CD8 T cells. EBioMedicine 23:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng K, Pertea M, Rongvaux A, Wang L, Durand CM, Ghiaur G, Lai J, McHugh HL, Hao H, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Gurer C, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Deeks SG, Strowig T, Kumar P, Siliciano JD, Salzberg SL, Flavell RA, Shan L, Siliciano RF. 2015. Broad CTL response is required to clear latent HIV-1 due to dominance of escape mutations. Nature 517:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsden MD, Zack JA. 2015. Double trouble: HIV latency and CTL escape. Cell Host Microbe 17:141–142. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folkvord JM, Armon C, Connick E. 2005. Lymphoid follicles are sites of heightened human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication and reduced antiretroviral effector mechanisms. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 21:363–370. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukazawa Y, Lum R, Okoye AA, Park H, Matsuda K, Bae JY, Hagen SI, Shoemaker R, Deleage C, Lucero C, Morcock D, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Hirsch VM, Edlefsen PT, Piatak M Jr, Estes JD, Lifson JD, Picker LJ. 2015. B cell follicle sanctuary permits persistent productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in elite controllers. Nat Med 21:132–139. doi: 10.1038/nm.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, Rathnavalu P, Moore C, Pfafferott KJ, Hilton L, Zimbwa P, Moore S, Allen T, Brander C, Addo MM, Altfeld M, James I, Mallal S, Bunce M, Barber LD, Szinger J, Day C, Klenerman P, Mullins J, Korber B, Coovadia HM, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2004. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature 432:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereyra F, Jia X, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, de Bakker PIW, Walker BD, Ripke S, Brumme CJ, Pulit SL, Carrington M, Kadie CM, Carlson JM, Heckerman D, Graham RR, Plenge RM, Deeks SG, Gianniny L, Crawford G, Sullivan J, Gonzalez E, Davies L, Camargo A, Moore JM, Beattie N, Gupta S, Crenshaw A, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Gupta N, Gao X, Qi Y, Yuki Y, Piechocka-Trocha A, Cutrell E, Rosenberg R, Moss KL, Lemay P, O'Leary J, Schaefer T, Verma P, Toth I, Block B, Baker B, Rothchild A, Lian J, Proudfoot J, Alvino DML, Vine S, Addo MM, Allen TM, Altfeld M, Henn MR, Le Gall S, Streeck H, Haas DW, Kuritzkes DR, Robbins GK, Shafer RW, Gulick RM, Shikuma CM, Haubrich R, Riddler S, Sax PE, Daar ES, Ribaudo HJ, Agan B, Agarwal S, Ahern RL, Allen BL, Altidor S, Altschuler EL, Ambardar S, Anastos K, Anderson B, Anderson V, Andrady U, Antoniskis D, Bangsberg D, Barbaro D, Barrie W, Bartczak J, Barton S, Basden P, Basgoz N, Bazner S, Bellos NC, Benson AM, Berger J, Bernard NF, Bernard AM, Birch C, Bodner SJ, Bolan RK, Boudreaux ET, Bradley M, Braun JF, Brndjar JE, Brown SJ, Brown K, Brown ST, Burack J, Bush LM, Cafaro V, Campbell O, Campbell J, Carlson RH, Carmichael JK, Casey KK, Cavacuiti C, Celestin G, Chambers ST, Chez N, Chirch LM, Cimoch PJ, Cohen D, Cohn LE, Conway B, Cooper DA, Cornelson B, Cox DT, Cristofano MV, Cuchural G, Czartoski JL, Dahman JM, Daly JS, Davis BT, Davis K, Davod SM, DeJesus E, Dietz CA, Dunham E, Dunn ME, Ellerin TB, Eron JJ, Fangman JJW, Farel CE, Ferlazzo H, Fidler S, Fleenor-Ford A, Frankel R, Freedberg KA, French NK, Fuchs JD, Fuller JD, Gaberman J, Gallant JE, Gandhi RT, Garcia E, Garmon D, Gathe JC, Gaultier CR, Gebre W, Gilman FD, Gilson I, Goepfert PA, Gottlieb MS, Goulston C, Groger RK, Gurley TD, Haber S, Hardwicke R, Hardy WD, Harrigan PR, Hawkins TN, Heath S, Hecht FM, Henry WK, Hladek M, Hoffman RP, Horton JM, Hsu RK, Huhn GD, Hunt P, Hupert MJ, Illeman ML, Jaeger H, Jellinger RM, John M, Johnson JA, Johnson KL, Johnson H, Johnson K, Joly J, Jordan WC, Kauffman CA, Khanlou H, Killian RK, Kim AY, Kim DD, Kinder CA, Kirchner JT, Kogelman L, Kojic EM, Korthuis PT, Kurisu W, Kwon DS, LaMar M, Lampiris H, Lanzafame M, Lederman MM, Lee DM, Lee JML, Lee MJ, Lee ETY, Lemoine J, Levy JA, Llibre JM, Liguori MA, Little SJ, Liu AY, Lopez AJ, Loutfy MR, Loy D, Mohammed DY, Man A, Mansour MK, Marconi VC, Markowitz M, Marques R, Martin JN, Martin HL, Mayer KH, McElrath MJ, McGhee TA, McGovern BH, McGowan K, McIntyre D, Mcleod GX, Menezes P, Mesa G, Metroka CE, Meyer-Olson D, Miller AO, Montgomery K, Mounzer KC, Nagami EH, Nagin I, Nahass RG, Nelson MO, Nielsen C, Norene DL, O'Connor DH, Ojikutu BO, Okulicz J, Oladehin OO, Oldfield EC, Olender SA, Ostrowski M, Owen WF, Pae E, Parsonnet J, Pavlatos AM, Perlmutter AM, Pierce MN, Pincus JM, Pisani L, Price LJ, Proia L, Prokesch RC, Pujet HC, Ramgopal M, Rathod A, Rausch M, Ravishankar J, Rhame FS, Richards CS, Richman DD, Rodes B, Rodriguez M, Rose RC, Rosenberg ES, Rosenthal D, Ross PE, Rubin DS, Rumbaugh E, Saenz L, Salvaggio MR, Sanchez WC, Sanjana VM, Santiago S, Schmidt W, Schuitemaker H, Sestak PM, Shalit P, Shay W, Shirvani VN, Silebi VI, Sizemore JM, Skolnik PR, Sokol-Anderson M, Sosman JM, Stabile P, Stapleton JT, Starrett S, Stein F, Stellbrink H-J, Sterman FL, Stone VE, Stone DR, Tambussi G, Taplitz RA, Tedaldi EM, Telenti A, Theisen W, Torres R, Tosiello L, Tremblay C, Tribble MA, Trinh PD, Tsao A, Ueda P, Vaccaro A, Valadas E, Vanig TJ, Vecino I, Vega VM, Veikley W, Wade BH, Walworth C, Wanidworanun C, Ward DJ, Warner DA, Weber RD, Webster D, Weis S, Wheeler DA, White DJ, Wilkins E, Winston A, Wlodaver CG, van't Wout A, Wright DP, Yang OO, Yurdin DL, Zabukovic BW, Zachary KC, Zeeman B, Zhao M. 2010. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 330:1551–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Streeck H, Lu R, Beckwith N, Milazzo M, Liu M, Routy JP, Little S, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Hecht F, Sekaly RP, Alter G, Heckerman D, Carrington M, Rosenberg ES, Altfeld M. 2014. Emergence of individual HIV-specific CD8 T cell responses during primary HIV-1 infection can determine long-term disease outcome. J Virol 88:12793–12801. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02016-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiepiela P, Ngumbela K, Thobakgale C, Ramduth D, Honeyborne I, Moodley E, Reddy S, de Pierres C, Mncube Z, Mkhwanazi N, Bishop K, van der Stok M, Nair K, Khan N, Crawford H, Payne R, Leslie A, Prado J, Prendergast A, Frater J, McCarthy N, Brander C, Learn GH, Nickle D, Rousseau C, Coovadia H, Mullins JI, Heckerman D, Walker BD, Goulder P. 2007. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat Med 13:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goulder PJ, Phillips RE, Colbert RA, McAdam S, Ogg G, Nowak MA, Giangrande P, Luzzi G, Morgan B, Edwards A, McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones S. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat Med 3:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leslie AJ, Pfafferott KJ, Chetty P, Draenert R, Addo MM, Feeney M, Tang Y, Holmes EC, Allen T, Prado JG, Altfeld M, Brander C, Dixon C, Ramduth D, Jeena P, Thomas SA, St John A, Roach TA, Kupfer B, Luzzi G, Edwards A, Taylor G, Lyall H, Tudor-Williams G, Novelli V, Martinez-Picado J, Kiepiela P, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat Med 10:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brockman MA, Schneidewind A, Lahaie M, Schmidt A, Miura T, Desouza I, Ryvkin F, Derdeyn CA, Allen S, Hunter E, Mulenga J, Goepfert PA, Walker BD, Allen TM. 2007. Escape and compensation from early HLA-B57-mediated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte pressure on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag alter capsid interactions with cyclophilin A. J Virol 81:12608–12618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01369-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naruto T, Gatanaga H, Nelson G, Sakai K, Carrington M, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2012. HLA class I-mediated control of HIV-1 in the Japanese population, in which the protective HLA-B*57 and HLA-B*27 alleles are absent. J Virol 86:10870–10872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00689-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murakoshi H, Akahoshi T, Koyanagi M, Chikata T, Naruto T, Maruyama R, Tamura Y, Ishizuka N, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2015. Clinical control of HIV-1 by cytotoxic T cells specific for multiple conserved epitopes. J Virol 89:5330–5339. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00020-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chikata T, Murakoshi H, Koyanagi M, Honda K, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2017. Control of HIV-1 by an HLA-B*52:01-C*12:02 protective haplotype. J Infect Dis 216:1415–1424. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chikata T, Carlson JM, Tamura Y, Borghan MA, Naruto T, Hashimoto M, Murakoshi H, Le AQ, Mallal S, John M, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Brumme ZL, Takiguchi M. 2014. Host-specific adaptation of HIV-1 subtype B in the Japanese population. J Virol 88:4764–4775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00147-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey JR, Williams TM, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. 2006. Maintenance of viral suppression in HIV-1-infected HLA-B*57+ elite suppressors despite CTL escape mutations. J Exp Med 203:1357–1369. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Connell KA, Brennan TP, Bailey JR, Ray SC, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. 2010. Control of HIV-1 in elite suppressors despite ongoing replication and evolution in plasma virus. J Virol 84:7018–7028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00548-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura T, Brockman MA, Schneidewind A, Lobritz M, Pereyra F, Rathod A, Block BL, Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Baker B, Rothchild AC, Li B, Trocha A, Cutrell E, Frahm N, Brander C, Toth I, Arts EJ, Allen TM, Walker BD. 2009. HLA-B57/B*5801 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite controllers select for rare gag variants associated with reduced viral replication capacity and strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte recognition. J Virol 83:2743–2755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02265-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pohlmeyer CW, Buckheit RW 3rd, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. 2013. CD8+ T cells from HLA-B*57 elite suppressors effectively suppress replication of HIV-1 escape mutants. Retrovirology 10:152. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoof I, Perez CL, Buggert M, Gustafsson RK, Nielsen M, Lund O, Karlsson AC. 2010. Interdisciplinary analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses against variant epitopes reveals restricted TCR promiscuity. J Immunol 184:5383–5391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin Qin P, Su F, Xiao Yan W, Xing Z, Meng P, Chengya W, Jie S. 2011. Distribution of human leucocyte antigen-A, -B and -DR alleles and haplotypes at high resolution in the population from Jiangsu province of China. Int J Immunogenet 38:475–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2011.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajalingam R, Krausa P, Shilling HG, Stein JB, Balamurugan A, McGinnis MD, Cheng NW, Mehra NK, Parham P. 2002. Distinctive KIR and HLA diversity in a panel of north Indian Hindus. Immunogenetics 53:1009–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00251-001-0425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rani R, Marcos C, Lazaro AM, Zhang Y, Stastny P. 2007. Molecular diversity of HLA-A, -B and -C alleles in a North Indian population as determined by PCR-SSOP. Int J Immunogenet 34:201–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2007.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoa BK, Hang NT, Kashiwase K, Ohashi J, Lien LT, Horie T, Shojima J, Hijikata M, Sakurada S, Satake M, Tokunaga K, Sasazuki T, Keicho N. 2008. HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 and -DQB1 alleles and haplotypes in the Kinh population in Vietnam. Tissue Antigens 71:127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romphruk AV, Romphruk A, Kongmaroeng C, Klumkrathok K, Paupairoj C, Leelayuwat C. 2010. HLA class I and II alleles and haplotypes in ethnic northeast Thais. Tissue Antigens 75:701–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puangpetch A, Koomdee N, Chamnanphol M, Jantararoungtong T, Santon S, Prommas S, Hongkaew Y, Sukasem C. 2014. HLA-B allele and haplotype diversity among Thai patients identified by PCR-SSOP: evidence for high risk of drug-induced hypersensitivity. Front Genet 5:478. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashimoto M, Akahoshi T, Murakoshi H, Ishizuka N, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2012. CTL recognition of HIV-1-infected cells via cross-recognition of multiple overlapping peptides from a single 11-mer Pol sequence. Eur J Immunol 42:2621–2631. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stranford SA, Ong JC, Martinez-Marino B, Busch M, Hecht FM, Kahn J, Levy JA. 2001. Reduction in CD8+ cell noncytotoxic anti-HIV activity in individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy during primary infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spiegel HM, DeFalcon E, Ogg GS, Larsson M, Beadle TJ, Tao P, McMichael AJ, Bhardwaj N, O'Callaghan C, Cox WI, Krasinski K, Pollack H, Borkowsky W, Nixon DF. 1999. Changes in frequency of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T cell precursors and circulating effectors after combination antiretroviral therapy in children. J Infect Dis 180:359–368. doi: 10.1086/314867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pitcher CJ, Quittner C, Peterson DM, Connors M, Koup RA, Maino VC, Picker LJ. 1999. HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells are detectable in most individuals with active HIV-1 infection, but decline with prolonged viral suppression. Nat Med 5:518–525. doi: 10.1038/8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Casazza JP, Betts MR, Picker LJ, Koup RA. 2001. Decay kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol 75:6508–6516. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6508-6516.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watanabe K, Murakoshi H, Tamura Y, Koyanagi M, Chikata T, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2013. Identification of cross-clade CTL epitopes in HIV-1 clade A/E-infected individuals by using the clade B overlapping peptides. Microbes Infect 15:874–886. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yagita Y, Kuse N, Kuroki K, Gatanaga H, Carlson JM, Chikata T, Brumme ZL, Murakoshi H, Akahoshi T, Pfeifer N, Mallal S, John M, Ose T, Matsubara H, Kanda R, Fukunaga Y, Honda K, Kawashima Y, Ariumi Y, Oka S, Maenaka K, Takiguchi M. 2013. Distinct HIV-1 escape patterns selected by cytotoxic T cells with identical epitope specificity. J Virol 87:2253–2263. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02572-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watanabe T, Murakoshi H, Gatanaga H, Koyanagi M, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2011. Effective recognition of HIV-1-infected cells by HIV-1 integrase-specific HLA-B *4002-restricted T cells. Microbes Infect 13:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akahoshi T, Chikata T, Tamura Y, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2012. Selection and accumulation of an HIV-1 escape mutant by three types of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognizing wild-type and/or escape mutant epitopes. J Virol 86:1971–1981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06470-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomiyama H, Akari H, Adachi A, Takiguchi M. 2002. Different effects of Nef-mediated HLA class I down-regulation on human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD8(+) T-cell cytolytic activity and cytokine production. J Virol 76:7535–7543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7535-7543.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomiyama H, Fujiwara M, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2005. Cutting Edge: epitope-dependent effect of Nef-mediated HLA class I down-regulation on ability of HIV-1-specific CTLs to suppress HIV-1 replication. J Immunol 174:36–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawashima Y, Kuse N, Gatanaga H, Naruto T, Fujiwara M, Dohki S, Akahoshi T, Maenaka K, Goulder P, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2010. Long-term control of HIV-1 in hemophiliacs carrying slow-progressing allele HLA-B*5101. J Virol 84:7151–7160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00171-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sudo T, Kamikawaji N, Kimura A, Date Y, Savoie CJ, Nakashima H, Furuichi E, Kuhara S, Sasazuki T. 1995. Differences in MHC class I self peptide repertoires among HLA-A2 subtypes. J Immunol 155:4749–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Takiguchi M, Gnau V, Stevanović S, Jung G, Rammensee HG. 1995. Peptide motifs of HLA-B58, B60, B61, and B62 molecules. Immunogenetics 41:165–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00182333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]