Abstract

Before 1990, Germany was divided for more than 40 years. While divided, significant mortality disparities between the populations of East and West Germany emerged. In the years following reunification, East German mortality improved considerably, eventually converging with West German levels. In this study, we explore changes in the gender differences in health at ages 20–59 across the eastern and western regions of Germany using data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) for the 1990–2013 period. We apply random-effects linear regressions to the SOEP data to identify trends in health, measured as self-assessed health satisfaction, after German reunification.

The findings indicate that women were substantially less satisfied with their health than men in both West and East Germany, but that the gender gap was larger in East Germany than in West Germany. Furthermore, the results show that respondents’ satisfaction with their health decreased over time, and that the decline was steeper among men – and particularly among East German men – than among women. Thus, the initial male advantage in health in East and West Germany in the years immediately after reunification diminished over time, and even reversed to become a female advantage in East Germany. One interpretation of this finding is that stress-inducing post-reunification changes in the political and social landscape of East Germany had lasting damaging consequences for men’s health.

Ongoing risky health behaviors and high levels of economic insecurity due to unemployment could have had long-lasting effects on the health of the working-aged population. A partial explanation for our finding that health declined more sharply among East German men than among their female counterparts could be that women have better compensatory mechanisms than men for dealing with psychosocial stress.

Keywords: Gender Health Gap, German reunification, Health satisfaction, German Socio-Economic Panel

1. Introduction

Gender differences in health and mortality have long been of interest to researchers. Women live longer than men, but suffer from worse health. In the 1970s, Nathanson pointed out that despite the consistent female advantage in survival, women tend to be in worse health than their same-aged male counterparts (Nathanson, 1975). These seemingly contradictory trends are often referred to as the male-female health-survival paradox (Case and Paxson, 2005, Oksuzyan et al., 2008, Wingard, 1984). The research literature on this issue has reported that men do better on physical performance tests than women (Bohannon et al., 2006, Cooper et al., 2011), and that males have more functional limitations at all ages than females of the same age (Murtagh and Hubert, 2004, Newman and Brach, 1999, Palacios-Ceña et al., 2012). It has also been shown that women tend to report being in worse general health than men of the same age (Crimmins et al., 2010, Dahlin and Härkönen, 2013, Oksuzyan et al., 2014).

The female disadvantage in self-reported health has been found to be larger at younger ages, and to diminish with increasing age (Gorman & Read, 2006) and when other health measures are controlled for in the model (Crimmins et al., 2010). In countries where men and women have more similar lives and health behaviors, health outcomes tend also to be more similar. The magnitude of the gender gap in self-reported health varies substantially across European (EU) countries; it is more pronounced in the eastern and the southern EU countries, and it is small or negligible in Denmark and Norway (Crimmins et al., 2010, Dahlin and Härkönen, 2013, Oksuzyan et al., 2010). However, few studies have focused on the drivers of cross-national differences in gender gaps in health.

In the present study, we analyze gender differences in health among the working-aged populations of East and West Germany. The German reunification provides us with a unique setting for examining the effects of different socioeconomic and ideological conditions, including value structures and attitudes or beliefs (e.g. about gender equality), on women’s and men’s health. We focus on the working age populations as these groups have been most affected by the changes in the German labor market following reunification. In doing so we consider individual-level explanations and discuss macro-level implications of gender differences in health. Specifically, we investigate whether changes in health since reunification follow similar patterns among East and West German women and men.

It is particularly interesting to analyze the health patterns of Germany because the country was divided between 1949 and 1990 into two countries: the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). The populations of East and West Germany have a shared culture and history, but they experienced different political and economic settings for more than 40 years. The societal differences that arose during the division have had lasting effects also on the mortality levels in both parts of the country. Starting at the end of the 1970s, the mortality levels of older East Germans in particular began to fall behind those of their West German counterparts. Improvements in cardiovascular mortality in West Germany led to lower age-specific risks of death among West German men and women. Since German reunified in 1990, the once-large mortality disadvantage of East Germans has disappeared among women and has narrowed considerably among men (HMD, 2016). In particular, East Germans aged 60 and older have seen a marked reduction in their risk of death (Vogt, 2013). However, large East-West mortality disparities remain among men of working ages, as mortality improvements among these age groups have stagnated. Several studies have attributed the convergence of mortality levels in East and West Germany to the equalization of living conditions, the adaptation of health behaviors, and improvements in health care (Kibele, 2012; Nolte, Scholz, Shkolnikov, & McKee, 2002; Nolte, Shkolnikov, & McKee, 2000; Vogt & Vaupel, 2015). These trends may have simultaneously led to a decline in health inequalities between West and East Germany.

The existing literature on the differences in health among West and East Germans has shown that economic factors play an important role (e.g., Razum, Altenhöner, Breckenkamp, & Voigtländer, 2008; Roeding, Beck, & Elkeles, 2013). Frijters, Haisken-DeNew, and Shields (2005) found a positive effect of increasing income on health satisfaction in East Germany. In a study analyzing the relationship between income and poor self-rated health across different welfare state regimes (Sweden, West and East Germany), Miething, Lundberg, and Geyer (2013) found no clear pattern of poor self-rated health among East Germans in the lower household income quintiles, and suggested that East Germany has specific social stratification characteristics that continue to differentiate it from West Germany. In an examination of the effects on health of regional economic factors, such as community income and the labor market, Eibich and Ziebarth (2014) found that these factors have strong and significant associations with individual health. These findings have been explained by evidence showing that following reunification, older East Germans benefited from enormous pension increases and improvements in health care availability, whereas East Germans of working ages suffered from the changes in labor market conditions. Such changes led to destandardization and discontinuity in the life courses of many East Germans, as they experienced repeated phases of unemployment, temporary work, or marginal employment (Easterlin and Plagnol, 2008, Simonson et al., 2015).

2. Background

2.1. Explanations for gender differences in health

Other than differences in biological endowments – including hormonal and genetic factors – the prevailing explanations in the literature for gender differences in health and survival refer to gender gaps in lifestyle behaviors and to the social profiles of men and women (see Oksuzyan, Gumà, and Doblhammer (2018) for a review). Of the factors associated with lifestyle behaviors, tobacco and alcohol consumption are most frequently cited in explanations of gender differences in health and mortality. There is evidence across all western countries that men are more likely than women to consume both tobacco and alcohol (Costanza, Salamun, Lopez, & Morabia, 2006), and that the effects of the consumption of these substances on health and survival are more severe among men than among women (Mucha et al., 2006, Stahre et al., 2014).

Social explanations for gender differences in health and survival highlight the importance of social profiles and the differential access of certain groups to protective resources (such as education and employment) (Bird & Rieker, 2008a). Positive associations between education and health and mortality have been found in many studies. The main explanations for the positive effects of education on health and mortality are either direct – i.e., that more educated people have better access to knowledge about healthy lifestyles; or are indirect – i.e., that more educated people have higher levels of employment and income, as well as better access to health protective resources, such to the health care system and healthy food (Ross, Masters, & Hummer, 2012). Gender differences in education have narrowed or even reversed in favor of women. The closing of this gap has led not only to improved female survival rates, but to lower child mortality rates due to improved knowledge about healthy lifestyles for both mothers and children (Gakidou, Cowling, Lozano, & Murray, 2010). The findings in the literature on the question of whether education has different effects on women’s health and mortality than on men’s have been inconsistent. A study conducted with US data found a pattern that suggested that education might reduce the male-female health-survival paradox. The results for the US male population indicated that having a higher education is associated with improvements in survival, but not in health. The opposite pattern – i.e., improvements in health, but not in mortality – was observed for the US female population (Ross et al., 2012).

Employment, used as a proxy for socioeconomic status, is positively associated with health. This association may be causal, in that employment improves health, or it could result from the selection of healthy individuals into the labor market (Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003). A number of studies have found that unemployment increases the risk of morbidity and mortality (Bartley, Ferrie, & Montgomery, 2006; Cohen et al., 2007; Leist, Glymour, Mackenbach, van Lenthe, & Avendano, 2013; Martikainen & Valkonen, 1996; McKee-Ryan, Song, Wanberg, & Kinicki, 2005; Roelfs, Shor, Davidson, & Schwartz, 2011). The role of gender has also been discussed in the literature on employment and health. However, findings suggesting that unemployment has different effects on health in men and women have been inconsistent. A considerable number of studies show that unemployment has a greater effect on men’s mental health than on women’s (Artazcoz et al., 2004, Paul and Moser, 2009), while McKee-Ryan et al. (2005) found that unemployed women have poorer mental health than men. A comparison between Ireland and Sweden shows that unemployed women in Ireland have lower levels of psychological distress than men, while in Sweden unemployed women have higher levels of psychological distress than men (Strandh, Hammarström, Nilsson, Nordenmark, & Russel, 2013). The authors explain these findings by pointing to differences in national context; the countries represent different gender relations and regimes, and female labor market participation is high in Sweden but low in Ireland. It may be that in contexts where men and women hold similar work and family roles, gender differences in the relationship between unemployment and mental health do not exist.

Adding to these individual-level explanations, Rieker, Bird, and Lang (2010) have argued that social policies also have a direct or indirect impact on gender differences in health. The authors observed that policy regimes can establish, reinforce, and transform social roles and gender relations. They pointed out that policy decisions affect people’s daily lives, especially their employment patterns, career options, and child care responsibilities. They further noted that policies can affect health both directly by providing universal access to health care; and indirectly by altering or reinforcing men’s and women’s opportunities to engage in health-related behaviors. Moreover, the authors argued that policies can reduce or buffer the health impact of social and economic strains by, for example, providing access to day care so women can enter or reenter the workplace (Bird & Rieker, 2008b).

2.2. German division and reunification

In light of these potential explanations for gender differences in health, the German division and reunification provides an interesting setting to analyze both, individual-level and macro-level explanations for gender differences in health. East Germany had a state-socialist system with a centrally planned economy and socialist employment and family policies. In contrast, West Germany had a multiparty parliament, a market economy, and a conservative-corporatist welfare state. These two contrasting systems had different effects on gender equality. While East Germany both expected and needed men and women to be employed, West Germany’s socially conservative welfare state supported the breadwinner model in which women were expected to leave or limit their employment after having children (Trappe & Rosenfeld, 1998). Thus, East German women, including mothers, had high levels of employment and tended to work full-time. To resolve mothers’ work-family conflicts, public child care was provided. In West Germany, policies such as income tax splitting and the provision of part-day kindergarten only encouraged women to leave the workforce or to work part-time (Rosenfeld, Trappe, & Gornick, 2004). After reunification, the institutions and employment structures in East Germany changed rapidly, while those in West Germany remained basically unchanged. The legal and political system of East Germany was replaced by the West German system. While these transformations were achieved quickly, the transformation of the East German economy was much slower (Goldstein & Kreyenfeld, 2011). Furthermore, it was predicted that the social unification, which includes any number of behavioral patterns, will take even longer (Witte & Wagner, 1995). The reunification had particularly influence on East German behavior, which was shown in many studies, e.g. for fertility (Conrad et al., 1996, Kreyenfeld, 2004). Studies have yet to assess whether the societal transformation affected the health of men and women differently.

2.3. Gender differences in mortality in East and West Germany

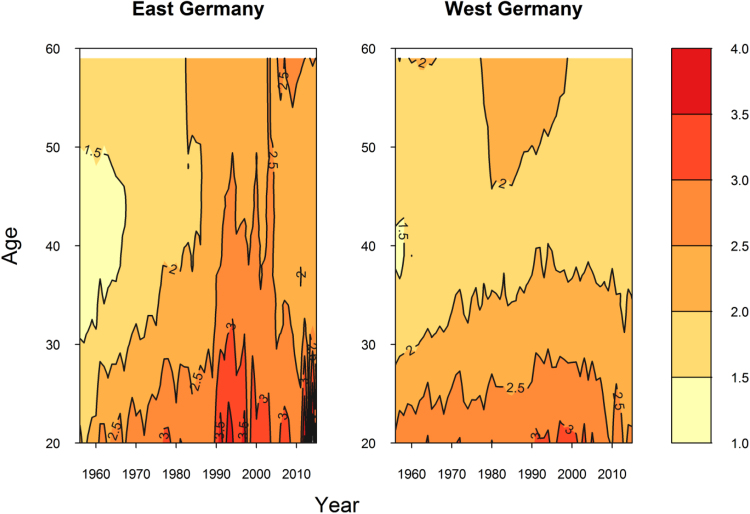

Based on the Human Mortality Database (HMD)1 (HMD, 2016), Fig. 1 shows the mortality rate ratios by sex at ages 20 to 59 in the 1980–2013 period by single years of age for East and West Germany. The left figure depicts the risk of death among East German men at different ages relative to the risk of death among East German women. In East Germany, men had a higher risk of death than women at all ages, especially at young adult ages. In their twenties, men were 2.5–3.0 more likely to die than women in the same age group. The mortality disadvantage for men was slightly lower among men aged 30–59, but it has increased over time. In the 1950s and early 1960s, men’s risk of death was 1.5–2 times higher than women’s in the 30–59 age group. The mortality disadvantage rose steadily until 1990, and increased markedly after reunification. During the 1990s, the relative mortality risk among men aged 30 and older reached levels that had previously been seen at young adult ages only. Since the end of the 2000s, the gender differences in mortality seem to have narrowed, but men continue to have a much higher risk of death than women. In 2015, East German men were still twice as likely to die as East German women.

Fig. 1.

: Male/female mortality risk ratios by age for East and West Germany, 1956–2011.

In West Germany, the pattern of gender mortality differences diverged considerably from that in East Germany over the same period of time (right figure). While there was a widening of the gap in the 20–40 age group, no dramatic increases were observed around the time of reunification. Between 1956 and 1995, the male mortality disadvantage increased from 1.5–2.0 to 2.0–2.5, mainly for the 30–40 and 45–59 age groups; but it did not reach the values observed in East Germany during the 1980s and 1990s. The male-female mortality ratios for the same age groups declined after 1995 to pre-1980 values.

Given these findings showing that after reunification, the mortality levels of East German women caught up to those of their West German counterparts more quickly than the mortality levels of East German men (Klenk et al., 2007, Myrskylä and Scholz, 2013), we also expect to find a narrowing of gender differences in health in East Germany. We aim to analyze the male-female differences in health in East and West Germany, and to investigate how this gender gap in health changed over time in the decades following reunification.

3. Data

To examine health trends after reunification and to explore gender differences in health in West and East Germany, we use panel data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). The SOEP is a nationally representative longitudinal dataset that covers the population of Germany (Wagner, Frick, & Schupp, 2007). The SOEP was initiated in West Germany in 1984. Since then, it has been conducted annually, and includes detailed social and economic information on all individuals aged 16 and older in the respondent households. Our analyses use only SOEP data from 1990 onward, because a sample of East German households was first added to the panel in 1990. We define East and West Germans based on responses to a retrospective question about the place of residence in 1989.

We use the self-assessed level of health satisfaction as the measure of health. The respondents were asked: “How satisfied are you at present with your health situation?” The answers were recorded on a scale of zero (“very unsatisfied”) to 10 (“very satisfied”). Previous research has shown that health satisfaction is strongly associated with general health and physical health measures (Butterworth & Crosier, 2004), and corresponds closely to self-assessed health (Frijters et al., 2005); an indicator that is commonly used as a proxy for assessing a respondent’s health status, and is considered to be a reliable measure of general health (Martikainen et al., 1999) and a good predictor of future morbidity and mortality (DeSalvo et al., 2006, Idler and Benyamini, 1997).

To assess the relationship between health satisfaction and self-rated health in our dataset, we calculated Pearson’s product-moment correlation and Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Both the Pearson’s product-moment correlation (-0.77; p < .0005) and the Spearman’s correlation (-0.76, p < .0005) showed a strong and significant negative correlation between the two health measures. The negative sign is caused by the reverse direction of the measures.

The advantage of using the SOEP health satisfaction measure is that it is available for all years from 1990 to 2013. While the SOEP includes other health measures, these indicators were introduced into the data collection instrument later, and are not available for the whole period of interest. Additional analyses with other health measures were conducted to assess whether they show trends similar to those of the health satisfaction measure (see details in the Supplementary materials).

3.1. Study population

Migration between West and East Germany after reunification can be assessed by using the retrospective question about the place of residence in 1989, and by drawing on annual information about the current place of residence. Between 1991 and 2014, 3.4 million East Germans migrated to the West and 2.2 million West Germans migrated to the East (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015). Most of the individuals who migrated from East to West were young and skilled, and a large proportion of them were women. Meanwhile, the people who stayed in the East tended to be older, in need of care, or low-skilled (Razum et al., 2008). We assume that the adaptation process occurred more quickly among the individuals who migrated from East to West Germany than among those who stayed in East Germany. To avoid selective out-migration effects, we focus on the individuals who had never migrated2.

Moreover, to avoid selection effects related to panel attrition caused by serious illness and multi-morbidity, we restrict our data to the working-aged population (aged 20–59). Among people aged 60 and older, panel attrition is mainly due to disease or death; whereas among younger people, panel attrition is mainly due to moving (Lipps, 2009).

3.2. Analytical strategy

Random-effects linear regressions were applied to examine the trajectories of health satisfaction from 1990 to 2013, and to account for the longitudinal nature of the data. Random effects are at the level of individuals, and each individual can contribute several observations. Although health satisfaction is measured on an ordinal scale, linear models are usually found to give results that are similar to those of discrete choice models, and that are easier to interpret (Dudel et al., 2016, Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters, 2004). Alternative models are used as robustness checks (see details in the supplementary materials).

3.3. Control variables

In addition to region (East and West Germany), gender is the main explanatory variable of interest, and is included in the multivariate analyses as a dummy (women as reference). To assess trends in health satisfaction in the years after reunification, we control for time as a continuous variable (time = year − 1989). Furthermore, all models include time squared to allow for non-linear trajectories. To investigate sex differences over time, we add the two-way interaction between sex and time (model 1 and model 2) and the group-specific slopes of sex with time and region (model 3). Age is divided into four categories and is included using dummy variables: (i) 20 to 24 (reference category), (ii) 25 to 29, (iii) 30 to 34, (iv) 35 to 39, (v) 40 to 44, (vi) 45–49, (vii) 50–54, and (viii) 55–59.

To adjust for socioeconomic status, the logarithmic net equivalent income (as a continuous variable), employment status, and education are included in the models. Net equivalent income is calculated using the modified OECD scale (Hagenaars, De Vos, & Asghar Zaidi, 1994). Employment status is broken down into five categories: (i) full-time, (ii) part-time, (iii) marginal employment3, (iv) in education, and (v) not employed4 (reference category). For education we use the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to distinguish three categories: (i) low (ISCED 0−2), (ii) middle (ISCED 3−4) (reference category), and (iii) high (ISCED 5−6).

4. Main findings

4.1. Descriptive analysis of health satisfaction

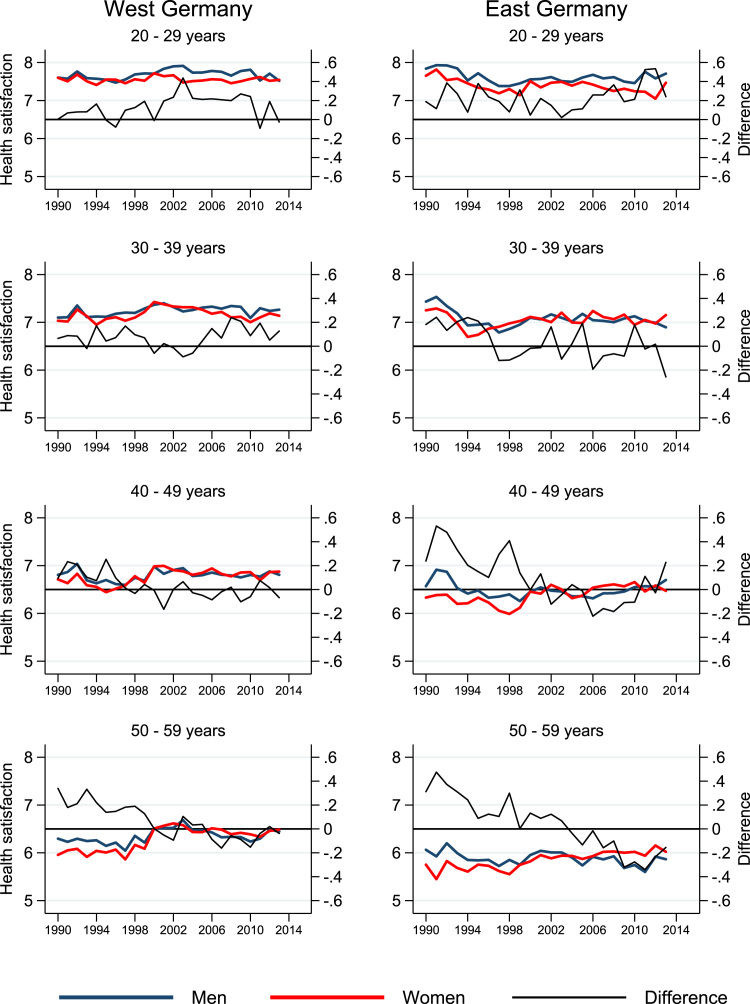

Fig. 2 shows the sex-specific unadjusted trajectories of health satisfaction among West and East Germans, and the absolute male-female differences in health satisfaction in four age groups.

Fig. 2.

: Trajectories of sex differences in health satisfaction.

Levels of health satisfaction declined with age in both women and men and in both parts of Germany. Among the 40–49 and 50–59 age groups, West Germans had higher levels of health satisfaction than East Germans. Among the younger age groups (20–29 and 30–39), East Germans had higher levels of health satisfaction than West Germans in 1990. However, these satisfaction levels decreased among the 20–29-year-olds through the late 1990s, and among the 30–39-year-olds through the mid-1990s. A sharp drop in health satisfaction shortly after reunification was observed among all of the age groups in the East German sample, and was particularly pronounced among the 30–39 and 40–49 age groups.

Except among the West Germans in the 20–29 and 30–39 age groups, the gender gap in health satisfaction favored men during the years immediately after reunification. The gender differences in health satisfaction were particularly large among the 40–49 and 50–59 age groups, and were larger in East than in West Germany. There was a clear narrowing of the gender gap among most of the age groups with time. Over the observation period, health satisfaction was higher among men than among women in both East and West Germany for the youngest age group only. While the gender gap in health satisfaction disappeared in West Germany among the 40–49 and 50–59 age groups in the early 2000s, there was even a crossover of sex differences in East Germany in the mid-2000s, when a female advantage in health emerged among the 50–59 age group.

4.2. Multivariate analysis of health satisfaction

Table 1 shows the results of the random-effects regression models. To identify regional-specific determinants of health satisfaction, we ran separate models for West and East Germany. For both samples, we show the null model without and models 1 and 2 with socioeconomic characteristics. The results for the null models suggest that women were far less satisfied with their health than men in both West and East Germany. However, the gender gap in health was larger in East than in West Germany. Furthermore, the results show a small but significant negative period effect among East Germans, which indicates that health satisfaction among these respondents declined over time. The interaction between sex and time is positive, which suggests that health satisfaction declined less steeply over time among women than among men. The effect of age is large and negative, which indicates that health satisfaction declined with age.

Table 1.

Random-effects regression models with sex and time interaction for West and East Germany (1990–2013).

| West Sample |

East Sample |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null Model |

Model 1 |

Null Model |

Model 2 |

|||||

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |

| Women | -0.16*** | 0.04 | -0.14** | 0.05 | 0.31*** | 0.06 | -0.25*** | 0.07 |

| Time | -0.00 | (0.00) | -0.00 | (0.00) | -0.06*** | 0.01 | -0.04*** | 0.01 |

| (Time)² | -0.00** | (0.00) | -0.00*** | (0.00) | 0.00*** | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Women x Time | 0.01** | (0.00) | 0.01*** | (0.00) | 0.02*** | (0.00) | 0.02*** | (0.00) |

| Age (reference 20–24) | ||||||||

| 25–29 | -0.15*** | 0.02 | -0.22*** | 0.03 | -0.16*** | 0.03 | -0.20*** | 0.04 |

| 30–34 | -0.35*** | 0.03 | -0.42*** | 0.03 | -0.39*** | 0.04 | -0.49*** | 0.05 |

| 35–39 | -0.52*** | 0.03 | -0.60*** | 0.04 | -0.69*** | 0.04 | -0.72*** | 0.05 |

| 40–44 | -0.74*** | 0.03 | -0.80*** | 0.04 | -1.01*** | 0.04 | -1.03*** | 0.05 |

| 45–49 | -0.95*** | 0.03 | -1.02*** | 0.04 | -1.30*** | 0.04 | -1.32*** | 0.05 |

| 50–54 | -1.20*** | 0.03 | -1.25*** | 0.04 | -1.57*** | 0.05 | -1.57*** | 0.06 |

| 55–59 | -1.45*** | 0.04 | -1.46*** | 0.04 | -1.91*** | 0.05 | -1.86*** | 0.06 |

| Employment status (reference: non-employed) | ||||||||

| Full-time | 0.14*** | 0.02 | 0.20*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Part-time | 0.08** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | ||||

| In education | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.14* | 0.06 | ||||

| Marginally | 0.07* | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | ||||

| (log) net equivalent income | 0.21*** | 0.02 | 0.22*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Education (reference: ISCED 3–4 Middle) | ||||||||

| ISCED 0–2 Low | -0.11*** | 0.03 | -0.13* | 0.06 | ||||

| ISCED 5–6 High | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||||

| Constant | 7.94*** | 0.04 | 5.82*** | 0.19 | 8.12*** | 0.05 | 5.78*** | 0.31 |

| Observations | 147217 | 119144 | 67431 | 50300 | ||||

| Sigma_u | 1.47 | 1.39 | 1.44 | 1.32 | ||||

| Sigma_e | 1.47 | 1.46 | 1.49 | 1.46 | ||||

| Rho | 0.5 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.45 | ||||

| R² | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.11 | ||||

Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Models 1 and 2 include the adjustment for socioeconomic characteristics. The results show that in West and in East Germany, gender gaps in health satisfaction decrease slightly when employment, education, and income are controlled for. The other coefficients are comparable to those of the null model. The socioeconomic coefficients are all in the expected direction. There is a significant positive effect of being employed (full-time or part-time) and of having a higher income and a higher education; although the latter effect is significant in West Germany only.

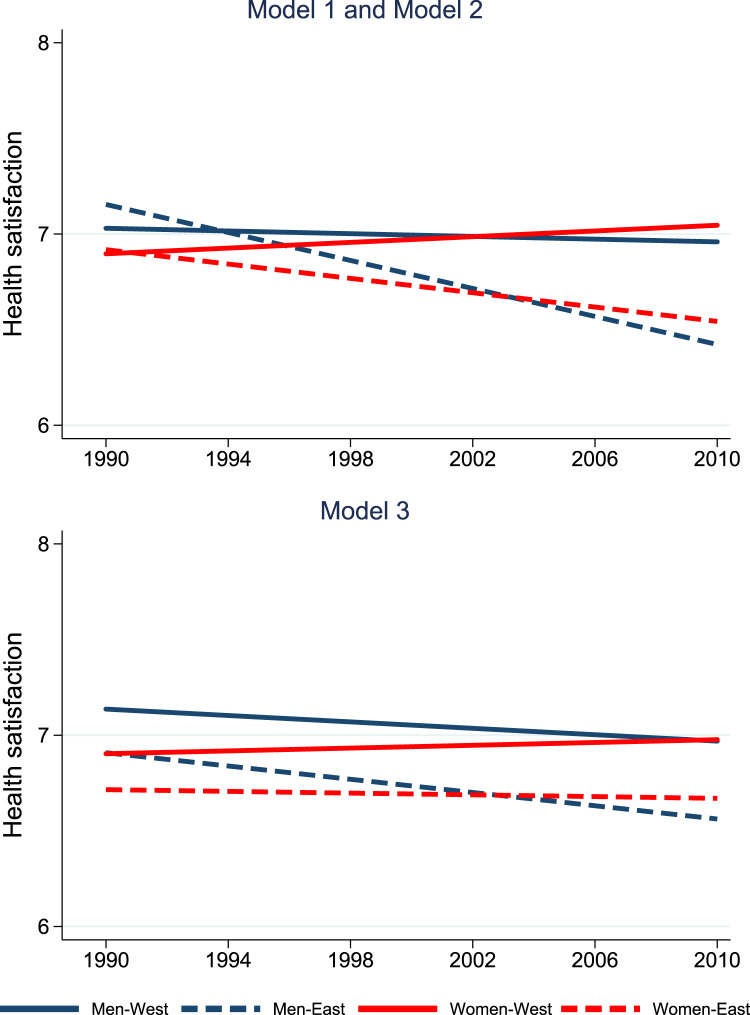

Since the quadratic effect of time in the model is difficult to interpret, we provide Fig. 3 in which the predicted health satisfaction levels based on model 1 and model 2 from Table 1 are shown (upper figure).

Fig. 3.

: Predicted health satisfaction.

Looking at the figure, we can see that over the study period, health satisfaction declined among both women and men in the East German sample, while there was no decline among women and a very small decline among men in the West German sample. We can also observe that in both samples, the male advantage in health satisfaction was large in the years immediately following reunification, but diminished over time. Moreover, it is apparent that after a crossover in the early 2000s, a female advantage in health satisfaction emerged in both samples.

To take regional differences into account as well, we pool the data and include group-specific slopes of sex, region, and time (Supplementary Table S.1). The special feature of this pooled model is that it allows us to estimate the joint effect of these three variables on health satisfaction, and thus to compare the trajectories in health satisfaction of the subgroups.

Fig. 3 (Model 3) shows that among all of the subgroups, East German men had the largest decline in health satisfaction, and that levels of health satisfaction were higher among West Germans than among East Germans. The regional gap in health widened over time, particularly among men.

In this model, we also observe a diminishing gender gap in health satisfaction after reunification. However, there were differences between West and East Germany in the timing of the crossover and in the extent of the female advantage.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main findings

Our examination of health satisfaction levels in Germany indicated that there was a pronounced gender gap favoring men in the years immediately after reunification, but that the male advantage diminished over time, and even reversed to become a female advantage in East Germany.

The trajectories of gender differences in health indicate that there was an overall – albeit diminishing – male advantage in health satisfaction in East and West Germany over the study period. While this pattern of a male advantage in health is generally in line with results from other countries, it is noteworthy a) that the magnitude of the gender differences was greater for East Germans than for West Germans (in the separated models); and b) that East German women had the lowest health satisfaction levels of any of the four groups (in the group-specific models) in the years immediately following reunification. Similar results were found in another study, which showed that in 1992, East German women were worse off than West German women and had significantly lower health status than East German men (Lüschen, Geling, Janßen, Kunz, & Von Dem Knesebeck, 1997). Potential explanations for these results are that health problems among East German women were carried over from the previous system or had not been sufficiently addressed by the new system after reunification. As we noted above, East German women had very high employment rates. However, even under a socialist system these women did not achieve full gender parity in terms of earnings and the division of labor at home. In addition to dealing with the demands of the workplace, East German women were expected to fill the traditional female role in the family. Moreover, a reunified Germany might have created new and potentially adverse conditions for East German women, including the risk of unemployment and the loss of social support services, such as childcare and kindergarten places for their children (Lüschen et al., 1997, Rosenfeld et al., 2004).

The predicted health satisfaction trajectories based on panel regression models indicated that East and West German women would overcome their health disadvantages. The trajectories showed a reversal of the gender gap in health and the emergence of a female advantage in health later in the study period, particularly among East Germans. While mortality improved substantially in East Germany, there were no apparent improvements in health, especially among men. As a result of this decline in health, within-gender regional differences in health increased as well. In contrast to previous research (e.g., Razum et al., 2008; Roeding et al., 2013), we found a widening regional gap in health in favor of West Germans that was smaller for women and larger for men.

Explanations for the decline in health among East German men must remain speculative. This trend might be partially explained by differences in health behavior, which we could not control for due to the unavailability of such data in the SOEP. Comparisons of East and West Germans before reunification indicate that compared to West Germans, East Germans were less active and had fewer opportunities for physical activity. Because the East German state prioritized elite competitive sports, it had limited resources to invest in sports infrastructure for the general public (Ståhl, Rütten, Nutbeam, & Kannas, 2002). This history helps to explain why East Germans are still less active in sport clubs than West Germans. However, there is evidence that East German women aged 55 to 69 have recently reached the same physical activity levels as their West German counterparts, while the activity levels of East German men in this age group still lag behind those of West German men. Similar results have been reported for the younger population (Robert Koch-Institut, 2009).

Sex differences in the consumption of tobacco and alcohol have also been found. In the early 1990s, the prevalence of smoking was higher among men than among women in both East and West Germany. While smoking prevalence was lower among East German than West German women, it was higher among East German than West German men. Recent data from 2012 indicate that the regional and the sex differences in tobacco use have disappeared (Robert Koch-Institut, 2014). Before reunification, alcohol consumption in East Germany was relatively high compared to levels in other countries. The prevalence of hazardous alcohol consumption continued to be high in East Germany after 1990. Findings based on data from 2012 show that East German men still had significantly higher levels of hazardous alcohol use than West German men (GEDA, 2012).

Furthermore, levels of overweight and obesity were higher among East than West Germans before reunification. Since then, the regional gap has narrowed, but the prevalence and incidence of overweight and obesity has been increasing in both parts of Germany (Robert Koch-Institut, 2014). It is well-known that obesity is among the leading causes of elevated cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and morbidity. Thus, the relatively high rates of obesity combined with the abovementioned risky lifestyles of East German men might explain the decreasing trend in their health satisfaction levels. Bird and Rieker (2008a) observed that gender differences in the prevalence of damaging lifestyle behaviors could be seen as a gendered response to constraints, or as a strategy for coping with existing vulnerabilities or with social circumstances that lead men and women to feel insecure and overwhelmed. This association could be an explanation for the risk-taking health behavior of East German men both before and after reunification.

As we noted above, working-aged East Germans suffered from the effects of soaring unemployment and economic insecurity following reunification. Although Easterlin and Plagnol (2008) did not distinguish between East German men and women, they demonstrated that life satisfaction in post-reunification East Germany declined until the late 1990s because of the deterioration in economic conditions. Our results indicate that after reunification, women had lower health satisfaction for a short period of time, but men suffered lasting damage resulting from the stress-inducing changes that were occurring in the political and social landscape of East Germany. A possible mediating factor between worsening economic conditions and subjective health is how men and women cope with adverse life events. The overall link between stressful life events and physical and mental health is well-established (Theorell & Rahe, 1975). However, individuals may differ in terms of their access to the social and emotional resources needed to cope with these challenges. An important moderator in dealing with stressful life periods is the availability and the capacity to make use of social support (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Social support has been found to lower cortisol levels (Heinrichs, Baumgartner, Kirschbaum, & Ehlert, 2003), and its overall stress-protective effect has been shown to be associated with a variety of health outcomes ranging from cancer to cardiovascular and infectious diseases (see Uchino (2006) for a review). Studies have found that men and women have different coping strategies and perceptions of the severity of stressors. Women seem to suffer more from interpersonal concerns and stress in their social environment, while men appear to suffer more from achievement and performance failures (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002). Additionally, compared to men, women’s coping strategies are more likely to be focused on emotional support and externalization (Taylor et al. 2000). These gender differences in coping strategies and perceptions of stressors may partially explain why East German men in particular experienced a steep decline in their subjective health.

It is also possible that there were gender differences in responses to the mass layoffs that affected most East German families after reunification. Burda and Hunt (2001) estimated that the unemployment rate (including hidden unemployment in the form of early retirement, involuntary part-time work, or enrollment in training programs) in East Germany leaped from almost zero to 33% between 1989 and 1992. Additionally, men and women suffered quite differently from the increase in unemployment. While both witnessed a dramatic loss in jobs, official female unemployment rates rose from 9.5% in 1991 to 22.2% in 1994 (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, 2017). During the same period, male unemployment rates rose from 7.9% to 13.3%. Men’s unemployment rates rose further during the 1990s, but remained on average 7–8 percentage points below female unemployment rates. Several studies have suggested that this rise in female unemployment was related to a “regression towards pre-war gender roles“ suffered by East German women after reunification (Adler, 1997). These widespread experiences with job loss and economic uncertainty led East German women to outflow to the West in search for better prospects (Hunt, 2000), leaving regions with a predominantly male population behind (Leibert, 2016).

The experience of unemployment has severe effects on health and mental well-being (see Paul and Moser (2009) for review). Strandh, Winefield, Nilsson, and Hammarström (2014) suggested that exposure to job loss at younger ages has long-term consequences for physical and mental health. These scaring effects over the life course could help to explain why the subjective health evaluations of East Germans have remained low even though their unemployment rates have been declining since the mid-2000s.

5.2. Methodological considerations

The data source we used for our analyses on health was the German SOEP. While SOEP data have been successfully used to study many different topics, they have some limitations. Most importantly, our findings might be affected by selective panel attrition. Previous literature has shown that attrition is correlated with worsening health (Lugtig, 2014), which could lead to biased estimates. An exploratory analysis of our data suggests that this is unlikely to the case here, as health satisfaction levels tend to be similar among respondents who remain in or drop out of the study (Supplementary Table S.2). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the individuals who dropped out of the panel did worse in the long run than those who remained in the sample. Furthermore, in the present study we could use only the SOEP data from 1990 onward. Thus, we were not able to use the data to examine the exogenous shock caused by reunification.

Another methodological limitation that is inherent in all panel studies is that panel conditioning effects can arise when respondents are influenced by having participated in previous surveys or waves (Das, Toepoel, & van Soest, 2011). Such effects could bias the results (Wooden & Li, 2014). Based on the SOEP data, Schupp, Goebel, Kroh, and Wagner (2013) showed that a correction for panel conditioning slightly affects the level of life satisfaction, but does not affect its trajectory. Even though health satisfaction was not included in their analyses, we can expect that panel conditioning would have no significant impact on health satisfaction trajectories.

A further potential limitation is that while the reliability of other health measures has been tested, only a few studies have tested the reliability of self-assessed health satisfaction. We therefore conducted additional analyses with both self-rated health and the SF-12v2 (Supplementary Table S.3). As the findings show that the patterns of health trajectories by region and gender are similar for the two measures, we concluded that health satisfaction can be used as a proxy measure.

Another potential issue involves the multivariate analyses. While the random-effects models we employed can control for unobserved time-constant heterogeneity, they rely on the assumption that the unobserved heterogeneity is not correlated with any of the observed characteristics. For instance, it is assumed that unobserved heterogeneity is not correlated with gender. We therefore estimated linear fixed-effects regressions that do not rest on this strong assumption as a robustness check (Supplementary Table S.4). The coefficient estimates are generally similar to the random-effects estimates with respect to sign and magnitude.

Overall, while we cannot completely rule out the possibility that our analyses were affected by the issues outlined above, our robustness checks using alternative modeling strategies and alternative health measures generated results consistent with our main findings.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we analyzed gender gaps in health among the German population after reunification. The results suggest that East German men have benefited from reunification less than East German women. Whereas men are generally healthier than women, the male advantage in health in East Germany diminished from 1990 to 2010, and even turned into a health disadvantage starting in the early 2000s. While mortality rates and results for health satisfaction might not be directly comparable, as the latter are adjusted for covariates and the former are not, a direct comparison reveals that while the male-female paradox in health and mortality was apparent in the years immediately after reunification, it was less pronounced at the end of the study period. The findings also suggest that the male-female health-survival paradox may vary over time, even when the same measure of health is considered.

More research into the causes of death is needed to explain the widening of the sex differences in mortality in East Germany and to understand the policy implications of this trend. For example, when objective health measures derived from German health insurance data become available, they can be used to examine whether the trajectories of health follow patterns similar to those of health satisfaction. Furthermore, these data can enable us to examine other mechanisms that could underlie the steeper health decline in men, such as differences between men and women in treatment-seeking behavior and/or in the distribution of acute life-threatening and non-acute disabling conditions.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Financial disclosure statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

The HMD contains national-level information on period and cohort deaths rates, life tables, population sizes, and exposures. The underlying data are drawn from different sources, ranging from vital statistics to censuses (www.mortality.org).

Additional models including migrants were calculated. The results were not sensitive to this inclusion. However, this very specific group needs more detailed analyses and interpretation. These findings are available on request.

The expression does not refer to specific working hours per week/month, but rather to a maximum monthly wage of 450 euros.

In addition to individuals who are unemployed and looking for a job, the latter category includes individuals who are performing military or community service, are on maternity/parental leave, or are in partial retirement and are no longer working.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.100326.

Contributor Information

Mine Kühn, Email: kuehn@demogr.mpg.de.

Christian Dudel, Email: dudel@demogr.mpg.de.

Tobias Vogt, Email: t.c.vogt@rug.nl.

Anna Oksuzyan, Email: oksuzyan@demogr.mpg.de.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- Adler M.A. Social change and declines in marriage and fertility in Eastern Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59(1):37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Artazcoz L., Benach J., Borrell C., Cortès I. Unemployment and mental health: Understanding the interactions among gender, family roles, and social class. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(1):82–88. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M., Ferrie J., Montgomery S.M. Health and labour market disadvantage: Unemployment, non-employment, and job insecurity. In: Marmot M., Wilkinson R.G., editors. Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bird C.E., Rieker P.P. Gender differences in health. In: Bird C.E., Rieker P.P., editors. Gender and health: The effects of constrained choices and social policies. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2008. pp. 16–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bird C.E., Rieker P.P. National social policies and constrained choice. In: Bird C.E., Rieker P.P., editors. Gender and health: The effects of constrained choices and social policies. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2008. pp. 76–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon R.W., Peolsson A., Massy-Westropp N., Desrosiers J., Bear-Lehman J. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a Jamar dynamometer: A descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2006;92(1):11–15. (doi: 10.1016%2Fj.physio.2005.05.003) [Google Scholar]

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2017). Statistik der Bundesagentur für Arbeit, Berichte: Analyse Arbeitsmarkt, Zeitreihen, Juli.

- Burda M.C., Hunt J.A. Vol. 2. Brookings Institution Press; 2001. From reunification to economic integration: Productivity and the labor market in Eastern Germany; pp. 1–92. (Brookings papers on economic activity). (Retrieved July 11, 2018, from Project MUSE database.) [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth P., Crosier T. The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian National Household Survey: Demonstrating the applicability of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A., Paxson C. Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Demography. 2005;42(2):189–214. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen F., Kemeny M.E., Zegans L.S., Johnson P., Kearney K.A., Stites D.P. Immune function declines with unemployment and recovers after stressor termination. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(3):225–234. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31803139a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad C., Lechner M., Werner W. East German fertility after unification: Crisis or adaptation? Population and Development Review. 1996;22(2):331–358. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R., Hardy R., Sayer A.A., Ben-Shlomo Y., Birnie K., Cooper C., Gallacher J. Age and gender differences in physical capability levels from mid-life onwards: The harmonisation and meta-analysis of data from eight UK cohort studies. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza M.C., Salamun J., Lopez A.D., Morabia A. Gender differentials in the evolution of cigarette smoking habits in a general European adult population from 1993–2003. BMC Public Health. 2006:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E.M., Kim J.K., Solé-Auró A. Gender differences in health: Results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. The European Journal of Public Health. 2010;21:81–91. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq022. (doi: 10.1093%2Feurpub%2Fckq022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin J., Härkönen J. Cross-national differences in the gender gap in subjective health in Europe: Does country-level gender equality matter? Social Science Medicine. 2013;98:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M., Toepoel V., van Soest A. Nonparametric tests of panel conditioning and attrition bias in panel surveys. Sociological Methods Research. 2011;40(1):32–56. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo K.B., Bloser N., Reynolds K., He J., Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(3):267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudel C., Ott N., Werding M. Maintaining one’s living standard at old age: What does that mean? Empirical Economics. 2016 (online first (Journal Article)) [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin R.A., Plagnol A.C. Life satisfaction and economic conditions in East and West Germany pre-and post-unification. Journal of Economic Behavior Organization. 2008;68(3):433–444. (doi: 10.1016%2Fj.jebo.2008.06.009) [Google Scholar]

- Eibich P., Ziebarth N. Examining the structure of spatial health effects using Hierarchical Bayes Models. Regional Science and Urban Economics (F07-V1) 2014 (doi: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/79844) [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell A., Frijters P. How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal. 2004;114(497):641–659. [Google Scholar]

- Frijters P., Haisken-DeNew J.P., Shields M.A. The causal effect of income on health: Evidence from German reunification. Journal of Health Economics. 2005;24(5):997. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakidou E., Cowling K., Lozano R., Murray C.J. Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: A systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2010;376(9745):959–974. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEDA (2012). Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012 Robert Koch-Institut, Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes.

- Goldstein J.R., Kreyenfeld M. Has East Germany overtaken West Germany? Recent trends in order-specific fertility. Population and Development Review. 2011;37(3):453–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman B.K., Read J.N.G. Gender disparities in adult health: An examination of three measures of morbidity∗. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(2):95–110. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars, A.J., De Vos, K., & Asghar Zaidi, M. (1994). Poverty statistics in the late 1980s: Research based on micro-data.

- Heinrichs M., Baumgartner T., Kirschbaum C., Ehlert U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HMD (2016). Human Mortality Database (Vol. downloaded: April 19th, 2016). USA) and Max- Planck- Institut for Demographic Research, Rostock (Germany: University of California, Berkeley; University of California, Berkeley (USA) Max- Planck- Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock (Germany).

- Hunt, J. (2000). Why do people still live in East Germany? NBER Working Paper No. 7564 〈www.nber.org/papers/37564〉.

- Idler E.L., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibele E.U. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. Regional mortality differences in Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Klenk J., Rapp K., Büchele G., Keil U., Weiland S.K. Increasing life expectancy in Germany: Quantitative contributions from changes in age- and disease-specific mortality. European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17(6):587–592. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M. Fertility decisions in the FRG and GDR: An analysis with data from the German fertility and family survey. Demographic Research. 2004 (special collection 3, article 11) [Google Scholar]

- Leibert T. She leaves, he stays? Sex-selective migration in rural East Germany. Journal of Rural Studies. 2016;43:267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Leist A.K., Glymour M.M., Mackenbach J.P., van Lenthe F.J., Avendano M. Time away from work predicts later cognitive function: Differences by activity during leave. Annals of Epidemiology. 2013;23(8):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipps O. Attrition of households and individuals in panel surveys. SOEP paper. 2009:164. [Google Scholar]

- Lugtig P. Panel attrition: Separating stayers, fast attriters, gradual attriters, and lurkers. Sociological Methods Research. 2014;43(4):699–723. [Google Scholar]

- Lüschen G., Geling O., Janßen C., Kunz G., Von Dem Knesebeck O. After unification: Gender and subjective health status in East and West Germany. Social Science Medicine. 1997;44(9):1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüschen G., Niemann S., Apelt P. The integration of two health systems: Social stratification, work and health in East and West Germany. Social Science Medicine. 1997;44(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen P., Aromaa A., Heliövaara M., Klaukka T., Knekt P., Maatela J., Lahelma E. Reliability of perceived health by sex and age. Social Science Medicine. 1999;48(8):1117–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen P.T., Valkonen T. Excess mortality of unemployed men and women during a period of rapidly increasing unemployment. The Lancet. 1996;348(9032):909–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee-Ryan F., Song Z., Wanberg C.R., Kinicki A.J. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;90(1):53–76. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miething A., Lundberg O., Geyer S. Income and health in different welfare contexts: A comparison of Sweden, East and West Germany. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2013;41(3):260–268. doi: 10.1177/1403494812472264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucha L., Stephenson J., Morandi N., Dirani R. Meta-analysis of disease risk associated with smoking, by gender and intensity of smoking. Gender Medicine. 2006;3(4):279–291. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh K.N., Hubert H.B. Gender differences in physical disability among an elderly cohort. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(8):1406–1411. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrskylä M., Scholz R. Reversing East-West mortality difference among German women, and the role of smoking. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42(2):549–558. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson C.A. Illness and the feminine role: A theoretical review. Social Science Medicine (1967) 1975;9(2):57–62. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(75)90094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A.B., Brach J.S. Gender gap in longevity and disability in older persons. Health. 1999;(1) doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte E., Scholz R., Shkolnikov V., McKee M. The contribution of medical care to changing life expectancy in Germany and Poland. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55:1905–1921. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte E., Shkolnikov V., McKee M. Changing mortality patterns in East and West Germany and Poland. II: Short-term trends during transition and in the 1990s. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2000;54(12):899–906. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.12.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksuzyan A., Crimmins E., Saito Y., O’Rand A., Vaupel J.W., Christensen K. Cross-national comparison of sex differences in health and mortality in Denmark, Japan and the US. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;25(7):471–480. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksuzyan A., Gumà J., Doblhammer G. Sex differences in health and survival. In: Doblhammer G., Gumà J., editors. A demographic perspective on gender, family and health in Europe. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2018. pp. 65–100. [Google Scholar]

- Oksuzyan A., Juel K., Vaupel J.W., Christensen K. Men: Good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;20(2):91–102. doi: 10.1007/bf03324754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksuzyan A., Shkolnikova M., Vaupel J.W., Christensen K., Shkolnikov V.M. Sex differences in health and mortality in Moscow and Denmark. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;29(4):243–252. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Ceña D., Jiménez-García R., Hernández-Barrera V., Alonso-Blanco C., Carrasco-Garrido P., Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Has the prevalence of disability increased over the past decade (2000–2007) in elderly people? A Spanish population-based survey. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(2):136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul K.I., Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74(3):264–282. [Google Scholar]

- Razum O., Altenhöner T., Breckenkamp J., Voigtländer S. Social Epidemiology after the German Reunification: East vs. West or Poor vs. Rich? International Journal of Public Health. 2008;53(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-6116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieker P.P., Bird C.E., Lang M.E. Understanding gender and health: Old patterns, new trends, and future directions. In: Bird C.E., Fremont A.M., T. S., editors. Handbook of medical sociology. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2010. pp. 98–113. (C. P) (C. P) [Google Scholar]

- Robert Koch-Institut (2009). 20 Jahre nach dem Fall der Mauer: Wie hat sich die Gesundheit in Deutschland entwickelt. Welche Faktoren beeinflussen die Gesundheit in den neuen und alten Bundesländern, was ist heute anders als vor 20 Jahren? Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. RKI, Berlin.

- Robert Koch-Institut (2014). 25 Jahre nach dem Fall der Mauer: Regionale Unterschiede in der Gesundheit. GBE Kompakt, 3(5. Jahrgang).

- Roeding D., Beck D., Elkeles T. Zusammenhänge zwischen dem sozioökonomischen Status und dem selbstberichteten Gesundheitszustand der Bevölkerung in nordostdeutschen Landgemeinden 1973, 1994 und 2004/2008. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(10):1376–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1794-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs D.J., Shor E., Davidson K.W., Schwartz J.E. Losing life and livelihood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Social Science Medicine. 2011;72(6):840–854. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R.A., Trappe H., Gornick J.C. Gender and work in Germany: Before and after reunification. Annual Review of Sociology. 2004;30(1):103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C.E., Masters R.K., Hummer R.A. Education and the gender gaps in health and mortality. Demography. 2012;49(4):1157–1183. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0130-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp J., Goebel J., Kroh M., Wagner G.G. Zufriedenheit in Deutschland so hoch wie nie nach der Wiedervereinigung: Ostdeutsche signifikant unzufriedener als Westdeutsche. DIW-Wochenbericht. 2013;80(47):34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Simonson J., Gordo L.R., Kelle N. Separate paths, same direction? De-standardization of male employment biographies in East and West Germany. Current Sociology. 2015;63(3):387–410. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhl T., Rütten A., Nutbeam D., Kannas L. The importance of policy orientation and environment on physical activity participation—a comparative analysis between Eastern Germany, Western Germany and Finland. Health Promotion International. 2002;17(3):235–246. doi: 10.1093/heapro/17.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M.R., Roeber J., Kanny D., Brewer R.D., Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11(E109) doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt (2015). Wanderungssaldo 2014 von Ost nach West mit 3300 Personen nahezu ausgeglichen.

- Strandh M., Hammarström A., Nilsson K., Nordenmark M., Russel H. Unemployment, gender and mental health: The role of the gender regime. Sociology of Health Illness. 2013;35(5):649–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandh M., Winefield A., Nilsson K., Hammarström A. Unemployment and mental health scarring during the life course. European Journal of Public Health. 2014;24(3):440–445. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres L.K., Janicki D., Helgeson V.S. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6(1):2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S.E., Klein L.C., Lewis B.P., Gruenewald T.L., Gurung R.A.R., Updegraff J.A. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review. 2000;107(3):411–429. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theorell T., Rahe R.H. Life change events, ballistocardiography and coronary death. Journal of Human Stress. 1975;1(3):18–24. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1975.9939543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trappe H., Rosenfeld R.A. A comparison of job-shifting patterns in the former East Germany and the Former West Germany. European Sociological Review. 1998;14(4):343–368. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B.N. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt T. How many years of life did the fall of the Berlin Wall add? A projection of East German life expectancy. Gerontology. 2013;59:276–282. doi: 10.1159/000346355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt T., Vaupel J. The importance of regional availability of health care for old age survival – Findings from German reunification. Population Health Metrics. 2015;13(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12963-015-0060-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G., Frick, J., & Schupp, J. (2007). The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) - Evolution, Scope and Enhancements. SOEPpaper, 1(Journal Article).

- Wilkinson R.G., Marmot M.G. Social determinants of health: The solid facts. 2 ed. World Health Organization; Copenhagen: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wingard D.L. The sex differential in morbidity, mortality, and lifestyle. Annual Review of Public Health. 1984;5(1):433–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte J.C., Wagner G.G. Declining fertility in east germany after unification: A demographic response to socioeconomic change. Population and Development Review. 1995;21(2):387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Wooden M., Li N. Panel conditioning and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2014;117(1):235–255. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material