Highlights

-

•

Identification of One Health Core Competencies for Africa

-

•

Development of One Health training modules for a multidisciplinary workforce

-

•

Integration of One Health competencies into courses and curricula

-

•

A framework for the design and implementation of One Health curricula for professionals who impact disease detection prevention and response

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, Africa and the world have faced severe public health threats, ranging from infectious disease outbreaks such as the Ebola outbreak in West Africa to environmental disruptions like the devastating effects of hurricane Matthew in Haiti. Recent outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases have captured global attention with their significant impact on health systems and economies. Boundaries between humans, animals and our environment are undergoing rapid changes [1]. Novel diseases are emerging and not just in humans. It is estimated that three out of four new infectious diseases occurring in humans are of animal origin [2]. The complexity of the issues: global movement of people, animals and disease-causing pathogens, cross border exchanges, increased human population, shrinking wildlife habitats, illegal wildlife trade, rapid globalization, pollution, loss of biodiversity, antimicrobial resistance and changes in environment and land use demand that we apply a systems thinking interdisciplinary approach to solve complex health challenges at the human animal and environmental interface.

Experiences from the fight against Ebola and the highly pathogenic avian influenza demonstrated the effectiveness of multi-sectoral, multi-agency approaches that are not limited by national or regional borders in dealing with public health threats [3]. One of the key approaches to achieve global health security is by building a multidisciplinary public health workforce that is well trained and fully equipped to counter infectious disease threats and that eliminate the current global barriers that exist because of disciplinary silos.

In response to this challenge, the One Health approach is advocated as the global framework for strengthening collaboration and capacities of the sectors and actors involved in health service delivery [4]. The One Health paradigm emerged from the recognition that the wellbeing of humans, animals and ecosystems are interrelated and interdependent, and there is need for more systematic and cross-sectoral approaches to identifying and responding to global public health emergencies and other health threats arising at the human-animal ecosystem interface [3]. The One Health concept is a growing global strategy for expanding interdisciplinary collaborations and communications in all aspects of health care for humans, animals and the environment that calls for a paradigm shift in developing, implementing and sustaining health policies [5].

Key to the implementation of One Health strategies is the redesign of a more integrative and dynamic educational system to better match the public health needs and produce a workforce that can effectively and efficiently respond to complex health challenges. Mismatch between present siloed professional competencies and the requirements of an increasingly multidisciplinary complex world means that overhauling public health education is imperative. In 2010, the commission on education for health professionals for the 21st century was launched. This independent initiative with a global outlook sought to advance health by recommending instructional and institutional innovations to develop a new generation of health professionals who would be better equipped to handle present and future complex health challenges in an era of rapid globalization [6]. Yet many professional training programs are still very traditional, producing graduates who are ill equipped to handle current challenges. One Health is a conceptual challenge to conventional public health training and practice because it addresses public health threats from a multidisciplinary collaborative perspective.

One Health Central and Eastern Africa (OHCEA) is a network of universities in Central, West and Eastern Africa which are collaborating to build One Health capacity and academic partnerships in the region. OHCEA membership includes twenty-four Central, West and Eastern Africa Schools of Public Health, Veterinary Medicine and Environmental Science; and US partner institutions: University of Minnesota (UMN) and Tufts University. The current OHCEA membership spans eight countries: Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, and Senegal [7], working together to strengthen public health education, systems, emergency preparedness and response.

OHCEA seeks to expand the human resource base needed to detect and respond to potential pandemic disease outbreaks, and increase integration of animal, wildlife and human disease surveillance and outbreak response systems using a One Health approach [7]. To do this effectively requires engagement of multidisciplinary groups of professionals with the right intellectual competencies and knowledge, capable of collaborating with each other. What type of training and preparation will provide public health professionals with the skills and competencies needed to combat such emerging public health threats?

The OHCEA network and its partner institutions, have developed One Health Core Competencies and modules that are key to delivering knowledge and skills to a multidisciplinary workforce and building a framework on which One Health curricula can be designed and implemented. A total of sixteen modules have been developed including One Health soft skills such communication, collaboration and partnership, culture, leadership, gender, policy and advocacy, systems thinking as well as core technical skills including ecosystem health, risk analysis, infectious disease epidemiology, One Health concepts and outbreak investigation and response. These modules are being used at both preservice and in-service levels. by faculty and students across OHCEA's eight countries and institutions in East and Central Africa, and by various government and private industry in these countries-deliberately focusing on building cross sectoral collaborative skills and technical competencies that prepare them to efficiently respond to any emerging public health threats. They are designed to fill the cross sectoral and technical skill gap caused by the changes in public health practice. The skills provided combine human and animal health sciences with the principles of ecology and environmental health while at the same time considering the social, economic, cultural and environmental impacts and effects on global health security. In this manuscript, we provide a detailed description of the module development process.

2. The framework for the design and implementation of One Health curricula

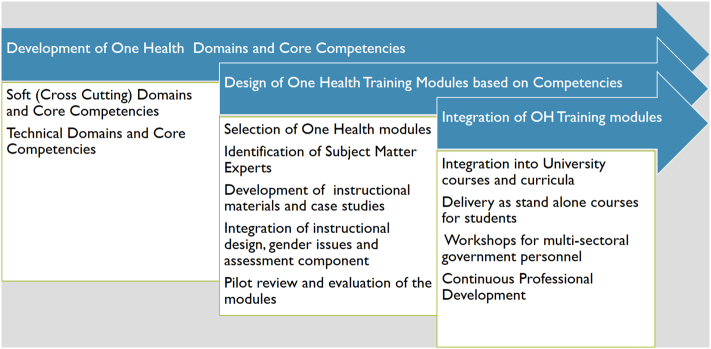

Redesign of professional public health education is essential. Bearing this in mind OHCEA sought to design and implement a One Health curriculum that could be adopted for use across most public health institutions of higher learning in Eastern and Central Africa. To anchor health science training around One Health principles, a team from OHCEA's institutions worked together to design curricula that included core competencies, course materials, case studies, and experiential learning activities. One Health was set as foundational for this educational experience. As part of the conceptual structure and process, OHCEA focused on identifying core competencies that were relevant for One Health, developing training modules aligned with these competencies, and ensuring the materials were relevant for integration into OHCEA partner university courses and curricula, and in-service government and private sector training including professional development programs. Fig. 1 shows the three main components of the framework and process used.

Fig. 1.

OHCEA OH module development conceptual structure and process.

3. Identification of OHCEA's One Health soft (cross cutting) domains and core competencies

A 2007 Salzburg Global Seminar, “New Century, New Challenges, New Dilemma: The Global Nexus of Animal and Public Health,” concluded that due to a siloed public health workforce, communication and collaboration across sectors was hampered, slowing down preparedness and response mechanisms and procedures [8]. Attention was drawn to the need for multidisciplinary cross sectoral training approaches that crossed the human animal and environmental divide. It was decided that a set of competencies needed to be identified for One Health professionals. These would include the knowledge skills and behaviors that an individual needed to acquire to effectively work across disciplines and to respond to complex health challenges. The multidisciplinary nature of One Health demanded that One Health professionals have competencies beyond their technical discipline specific knowledge gained through traditional programs. Although core competencies were originally developed for the business corporations they quickly became relevant for developing professional training programs that better equip individuals to work collaboratively [9 & 10]. This had already been done in public health by the Association of Schools of Public Health which in 2006, adopted a competency-based educational model that recognizes 12 domains and 119 core competencies for the Master of Public Health degree [11].

Between 2008 and 2011, the Bellagio Working Group supported by the Rockefeller Foundation and University of Minnesota; the Stone Mountain Meeting (SMM) Training Workgroup; and the RESPOND Initiative funded by the United States Agency for International Development's Emerging Pandemic Threats Program (USAID/RESPOND) separately began the process to identify core competencies for One Health professionals [12]. To draft the One Health core competencies, a wide range of existing core competency frameworks were reviewed, including the Guide to Senior Executive Service Qualifications of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, the Leadership Core Competencies of the Farm Service Agency of U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Association of Schools of Public Health Global Health Competency Model, and the Core Learning Activities for the Nigerian Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program [13].

Through USAID/RESPOND project, a multiagency Global One Health Core Competency Workgroup formed under Tufts University leadership to develop a One Health core competency framework that could be used to assess and strengthen curricula and training programs. Working globally, through a literature review of existing core competency frameworks in the public health, veterinary medicine, and infectious disease fields; telephone interviews with subject matter experts; and iterative feedback from interactive workshops with institutional partners in veterinary medicine, public health, nursing, and human medicine, the Workgroup came up with a set of One Health core competency domains and subdomains. A follow up workshop in 2012 in Rome, incorporated the findings of these three groups into a single set of One Health competencies. With the development of the Global One Health core competencies after the Rome meeting, in 2012, the Southeast Asian One Health University network identified SEAOHUN specific One Health core competencies [12 &14].

In September 2012, armed with the Global and the Southeast Asia core competencies, a team of people from OHCEA supported by Tufts University and the University of Minnesota convened a meeting in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania to identify, develop, map out and adapt relevant One Health Core Competencies based on the needs of the African region. A total of 32 participants drawn from multiple sectors across six OHCEA countries mainly Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Democratic Republic of Congo assembled. The sectors included universities, public health, human medicine, veterinary medicine, agriculture, livestock, environment, social sciences and biotechnology. They developed a consensus framework for One Health core competency domains that could be adapted and utilized by the OHCEA African region. Table 1 shows the soft (cross cutting) domains and competencies recognized by OHCEA and adapted for use in Africa. The nine core domains and supporting core competencies identified by OHCEA were management, communication, Gender culture and belief, leadership, collaboration and partnership, values and ethics, systems thinking, policy and advocacy and research.

Table 1.

Global, Seaohun and OHCEA One Health soft core competencies.

| Global | Searohun | OHCEA |

|---|---|---|

| Management | Management | Management |

| Communication and Informatics | Communication and Informatics | Communication |

| Culture and Beliefs | Culture and Beliefs | Gender,culture and belief |

| Leadership | Leadership | Leadership |

| Collaboration and Partnership | Collaboration and Partnership | Collaboration and Partnership |

| Values and Ethics | Values and Ethics | Values and Ethics |

| Systems Thinking | Systems Thinking | Systems Thinking |

| Policy and Advocacy | ||

| Research |

In addition to adapting the same competencies as the global and SEAOHUN teams, OHCEA recognized that gender, policy and advocacy and research were important elements in One Health training and needed to be included as core competencies. They therefore had these incorporated as One Health Core competencies for Africa. OHCEA went ahead to further synthesize the One Health domains, identifying subdomains where possible, definitions and sample core competencies under each domain (Table 2).

Table 2.

OHCEA OHCC Domains, Definitions, Subdomains, and Example Competencies.

| Domains | Subdomains | Definitions | Example core competencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Management | Planning Management Monitoring and evaluation Sustainability |

The process of planning, designing, implementing, organizing, monitoring, and evaluating One Health programs to maximize the effectiveness of OH action and desired health outcomes | Resource management and mobilization across sectors Create a OH action plan Ability to develop and apply M&E tools across disciplines Ability to plan for management of diseases (prevention, eradication and control) Ability to mobilize and manage resources (e.g. human, material and financial) Identify and prioritize OH related problems |

| Communication | Informatics | Acquisition, synthesis, and exchange of information across sectors, disciplines, and stakeholders to enhance and promote a common understanding of OH action | Develop a common understanding of the concept OH (knowledge of the concept, understanding the concept) Stakeholder/audience analysis Demonstrate capacity for connectivity within and across professions Demonstrate effective communication skills across OH activities and develop communication strategies (to effectively communicate with communities, scientist, policy makers (leaders) |

| Values and Ethics | The demonstration of integrity, honesty, trust, fairness, adaptability, and respect in OH action in diverse contexts | Promote transparency and accountability Be aware of own responsibility for the protection of the public Discipline and respect Demonstrate courage and perseverance in OH relevant situations To be able to demonstrate accountability responsibility honesty and respect |

|

| Leadership | Teamwork Professionalism Emotional intelligence |

Initiate a shared vision; create, inspire, and motivate teams across sectors; execute a role; and manage OH actions | Promote mutual respect between different [professional] corporations Develop an integrative vision, and strategic thinking Ability to motivate, delegate, Resource mobilization Demonstrate decisiveness and effective teamwork in OH relevant situations Leadership skills (negotiation skills, lobbying) To be able to mobilize, coach, and mentor others Motivate diverse disciplines towards OH goals Influence OH stakeholder |

| Collaboration and Partnership | Community participation and engagement Stakeholder analysis |

Identify, foster, and sustain equitable relationships with stakeholders while advancing OH actions | Recognize own limitations and develop the spirit of complementarity (for each discipline), Networking Diplomacy and international relations Ability to identify potential partners and to identify interdependence within and among institutions, establish networking, collaborate within and outside Demonstrate a commitment to building a trusting partnership Identification of stakeholders Creation and maintenance of strong links among stakeholders Organize diversity into common vision |

| Systems Thinking | One Health knowledge | Comprehensive approach that recognizes and appreciates how the dynamic interactions and interdependencies among entities within an ecosystem affect the functioning of the system | Develop a strategic vision based on opportunities and threats Apply systemic approach to understanding disease outbreaks Model and apply an effective systemic approach to addressing relevant OH issues Identify and explain core OH principles Apply OH principles in one's practice To have a knowledge on ecosystem health |

| Gender, Culture and Beliefs |

The diverse social norms, values, roles, and practices among individuals and within communities and agencies | Understanding and appreciating cultural/ethnic diversity Demonstrate cultural and situational sensitivity in interactions with the local communities Ability to recognize cultural diversity and respect of cultural differences among different stakeholders Ability to reshape cultures, beliefs and practices for proper management of diseases Identify gender roles access and control over resources and impacts on One Health Ensure gender equity |

|

| Policy and Advocacy | Lobbying Regulation Legislation |

Legal frameworks and other legitimate factors supporting and promoting implementation of OH approaches | Policy awareness, policy brief writing skills Skills to lobby, stakeholder engagement Identify relevant existing policies for OH concerns, design a policy to address a gap, advocate effectively for policy implementation in response to gaps identified in assessment exercises, establishment of OH data bases Share existing data across disciplines, compile new data |

| Research | Systematic investigation through multidisciplinary and intersectoral approaches to generate, validate, disseminate, and use OH knowledge | Develop an evidence-based practice Develop multidisciplinary and collaborative research Synthesize new and existing knowledge by examining ways to undertake academic research One Health. Critique research publications and reports regarding One health and identify ways to incorporate One health into them Design and conduct [create] academic qualitative and/or quantitative One health research. |

4. Identification of One Health technical core competencies

Keeping the public healthy requires not only a well-educated public health workforce but also a public health citizenry [15]. To build a skilled One Health workforce, it is evident that multiple disciplines must be engaged and collaborate across the human, animal and environmental interface especially in infectious disease detection prevention and response, antimicrobial resistance and ecosystem health changes. The 2013 Ebola outbreak in West Africa called for a workforce that had the technical skills and competencies to work well within their own discipline and sector but also possessed the skills to work across sectors to promote coordination and communication among all the stakeholders within the response sphere of an infectious disease of such global scale.

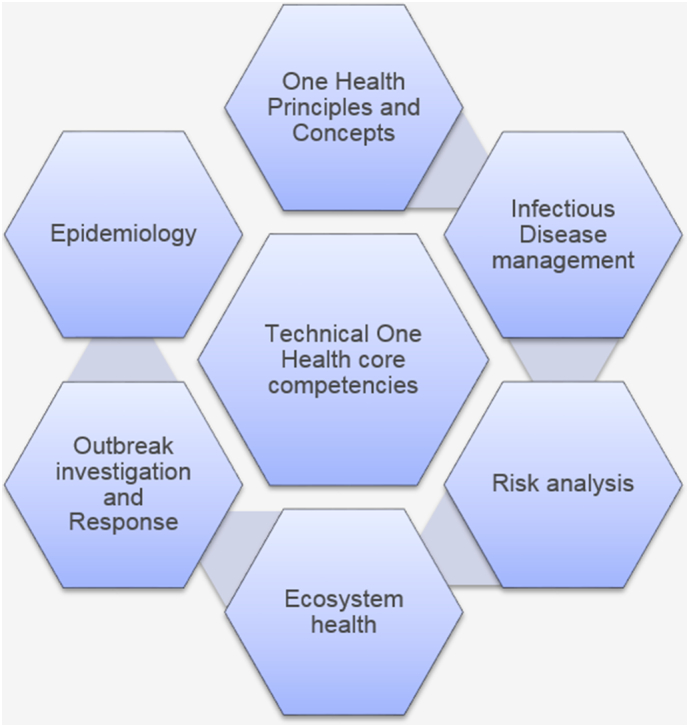

The different disciplines involved surpass the traditional public health workforce of medical doctors, nurses, and veterinarians. Other professions such as social scientists, anthropologists, engineers, agriculturalist, environmental scientist, policy makers play a major role in ensuring global health security. At the same time, certain professions such as medical doctors have traditional curricula that do not address areas like outbreak investigation and response, risk analysis or ecosystem health. These intrinsically important subjects need to be undertaken by health providers, so they can effectively synthesize, integrate and apply their skills to respond to public health threats. Based on this premise, OHCEA embarked on a process to identify discipline specific One Health core competencies that it felt were essential for all public health professionals. These views were consistent with the understanding that an effective public health workforce needed to grasp these concepts as central to an evidence based public health approach. A workshop was held in which a team of 22 people from the universities, public health, veterinary medicine, infectious disease, nursing and environmental health fields worked together over a period of five days, to identify what they considered were essential discipline specific One Health core competencies. Consultations and interviews were then held with people from different government sectors in the six OHCEA countries: health, nursing, and human medicine, veterinary medicine, agriculture and environmental sciences. Six technical or discipline specific core competencies were identified. These were One Health principles and concepts, ecosystem health, epidemiology, infectious disease management, risk analysis and outbreak Investigation and response. Fig. 2 These were added to the soft-core competencies already identified.

Fig. 2.

Technical/discipline specific one health core competencies.

These technical One Health core competencies combined with the soft competencies outline the skills and behaviors necessary for successful performance of the One Health workforce. The technical ones would specifically be appropriate for professionals from fields that were not traditional health professions such as engineering, social sciences and would be used as an opportunity to provide them with a basic background on the health-related issues. Educators at all levels of One Health training would be able to use these competencies as a resource for curriculum development, and to identify skill gaps in the current workforce.

5. Development of One Health course modules

The identification of core competencies was followed by conversion of these competencies into measurable knowledge and skills. The next step for OHCEA was to translate the core competencies into courses or training modules that could be offered at pre-service (before graduation) and in service (continuing education after graduation) as courses, workshops or integrated into the existing curricula at different higher-level institutions. OHCEA focused on developing sixteen One Health course modules aligned with each of the competencies identified. These 16 modules would form the basis for a One Health curriculum (Table 3).

Table 3.

One Health course modules that form basis for a One Health Curriculum.

| Soft (Cross cutting) One Health modules | Technical (Discipline specific) One Health Modules |

|---|---|

|

|

OHCEA identified a team of 47 people from the region to be part of the module development process. Of these, 32 subject matter specialists (SMS) from six OHCEA countries, participated in a week-long One Health core competency and module development workshop. The SMS were selected based on their areas of expertise in relation to their training, the universities they came from, the subjects they taught and how well versed they were with One Health. Twelve of the 32 SMS had already been through a course design workshop and were conversant with developing courses using the backward design principle. Of the initial 32, 24 were assigned as module developers and eight as module reviewers. The module developers were assigned a module based on their subject area of expertise. The reviewers were each required to review two modules each. The first two days of the workshop were focused on reviewing One Health principles and concepts and the One Health core competencies with the unified goal of defining and providing an understanding of One Health concepts, methodologies and applications that would be standardized across all the modules. Part of the third day was spent identifying the target audience of the modules to ensure that instructional methodologies and materials addressed the right stakeholders. The target audience for these modules were identified as any person who was considered a public health professional or who trained public health professionals including: faculty and students both within the OHCEA institutions and other institutions in the region, in service personnel from multiple government agencies and private sectors as well as professional organizations such as medical, veterinary, pharmacy and environmental associations. The central theme to be addressed across the modules was; what kind of training and instructional methodology would produce a multidisciplinary public health workforce with collaborative, cross cutting and technical skills to prepare and respond effectively to changing global health threats. The team aimed to create a frame work for One Health curriculum that encompassed One Health competencies combining human and animal health sciences, infectious disease and outbreak response with principles of ecology and environmental sciences.

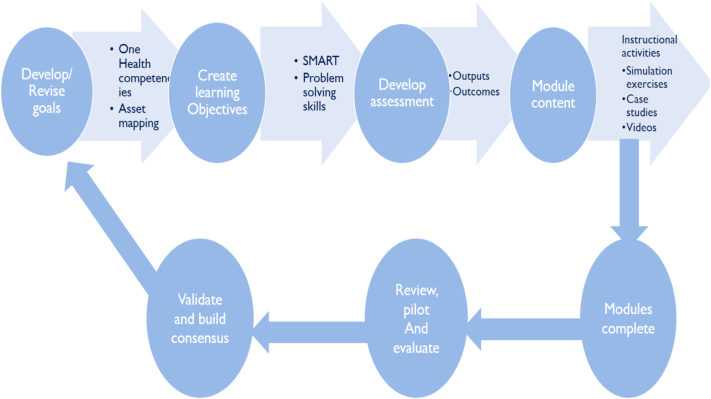

The participants working together as a team were exposed to a module development and course design process that used the backward design principle [16] and gained an understanding of how to design the modules based on a foundation of goals and objectives. Through this process, (Fig. 3) module developers identified goals first followed by learning objectives, assessment and course content for each module, developed sample case studies and began to identify instructional materials and innovative delivery tools and activities that were learner centered. Developers reviewed literature and performed on line searches for relevant resources including the SEAOHUN One Health Modules [17] and created a resource folder that could be used by the module facilitators and students.

Fig. 3.

Using backward design principle as basis to develop One Health course modules.

The modules focused on skill building and higher-level Blooms taxonomy activities [18]. Group activities such as discussions, brainstorming, role plays predominated instead of lectures. Many activities were student-facilitated discussions, case studies, simulations, use of video and audio tools and use of field experiential learning exercises with a focus on immediate complex global health challenges. During this development process, modules were customized based on local/regional examples, disease scenarios situations, environmental priorities, and gender and cultural impacts and roles in the African region. After the initial weeklong workshop, module developers then proceeded to complete them offline over a period of six months, after which they were submitted to a review process, with each module being reviewed by at least 2 people. Table 4 provides sample module overview.

Table 4.

Overview of the One Health Principles and Concepts module.

| Goals | Learning Objectives | Instructional Activity (Modes of Delivery) |

Materials | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovering basic Principles and Concepts of One Health | Identify and apply basic principles of One Health and related concepts Relate and assess how one health intersects with other disciplines, describe the global problem of inequitable health and the importance of using a One Health approach Explain OH core competencies Recognize gender gaps in One Health and emerging pandemics threat and identify resources to address those gaps |

Brainstorming, discovery activities, group discussions, videos on disease outbreaks-, power point presentations, One Health relevant articles- Power point presentations Internet searches, case studies, games (Rift Valley Fever case study, lead poisoning case study- case studies created by developers) |

Computer, LCD projector, screen/blank wall. Flipchart or whiteboard with markers 5–10 desks and chairs, scripts, Case studies, Internet videos | 8 h. |

| Using Systems Thinking Approach to One Health |

Utilize systems thinking approach in the One Health scenario that would improve public Health intervention and/or surveillance. Use concepts from wicked’ problem theory to better understand how to formulate and approach complex One Health challenge. |

Use case scenario Video clips and case studies such as Karatu Tanzania case study and mining in Lake Tshangalele to demonstrate the interaction of different disciplines and factors.Use brainstorming Group activity and group discussions to identify a OH scenario and identify multi-discipline and multi- sectoral players' involvement. |

whiteboard and markers Computer, LCD projector, screen/blank wall Module PowerPoint Internet access Video clip Group Discussions Case studies |

6 h. |

| Integrated Infectious Disease Management | Explain human animal environmental interaction in Infectious disease epidemiology and transmission Apply multidisciplinary approach to infectious disease investigation and response |

Power point presentations, role plays, Movies- contagion, case studies- Malaria, Bovine Tuberculosis, Panic in Rwanda case studies group discussions and brainstorming |

Computer, LCD projector, screen/blank wall Flipchart or whiteboard with markers 5–10 desks and chairs Scripts, videos Case studies |

6 h. |

| Understand and appreciate the influence of the interactions of humans, animals and environment in an ecosystem | Explain principles and concepts of ecosystem health Identify the risks of ecosystem disruption to human and animal health Analyze effects of climate change on ecosystem health Describe strategies for climate change mitigation and adaptation |

Brief case study depicting factors influencing human, animal and environmental health documentary/video clip Video- on Ecosystem health Drivers of climate change Group discussion PowerPoint presentation describing with examples effects of climate change |

Computer, LCD, Post Its® (2 colors) Flipcharts Tape, Markers Case studies, videos |

6 h. |

| One Health Leadership and Management | Apply One Health leadership and management principles to combat public health threats Develop Collaboration and partnership skills in Global Health Creating One Health Teams and stakeholder analysis |

Brainstorming, group discussions, power points, videos, role plays, case studies, simulation of emergencies Stakeholder mapping exercise |

Computer, LCD projector, whiteboard with markers 5–10 desks and chairs Scripts Case studies Internet videos |

6 h. |

6. Integration of gender component and review of the assessment section

The second level of revision after the initial development was to ensure that each of the modules had a gender component integrated into them. Gender, was identified by OHCEA as a fundamental One Health core competency since the diverse roles played by men and women create different exposure mechanisms to domestic animals, wildlife and the environment. OHCEA determined that all the One Health training modules should provide the public health specialists with the skills to address gender gaps and apply gender analysis tools to disease surveillance, response, prevention and control. Therefore, a second workshop was held to do a review of the modules with gender champions who had been trained through a training of trainers. 8 people from six OHCEA countries each worked on at least 2 modules together with the SMS at a weeklong workshop, revised the modules based on the recommendations of the gender team and inputted in each module a gender component. This workshop was followed by another one that reviewed the modules to ensure the assessment component was well done. Since the modules were intended to be used as stand-alone modules or integrated into different university courses and were the framework for curricula development it was important to ensure that the assessment processes were clear and aligned with the learning objectives as intended and that the modules could be used effectively for teaching purposes. 7 people trained in instructional design were identified to work with the module developers to ensure that the assessment component was done to the intended standards. At the end of these two workshops the modules were revised accordingly by the original developers and reviewed by a team of external reviewers with field-based expertise in each of the different modules. To date OHCEA has developed 16 One Health course modules that are undergoing a final review by external reviewers and are being used in draft form across the OHCEA countries. These modules consist of a facilitator guide, a student guide, power point slides and a resources folder that has pooled together a repository of relevant materials aligning with the specific One Health module and competency. The modules in their draft forms can be accessed on the OHCEA website under their resources menu [19].

7. Current and future intended use of the modules

As the One Health course modules were reviewed and revised over the last one and a half years, OHCEA used them in draft form across their different institutions and government networks as an opportunity to pilot them, revise them and create awareness of the existence and development of the modules. Through this process, many professionals were exposed to the One Health concept and developers received critical feedback from different stakeholders and used it to improve content and instructional methodology. In the last one year, faculty in six OHCEA countries used these One Health modules to integrate One Health core competencies into one hundred and eighteen (118) courses. Six One Health Modules selected and used for the integration of content into courses and curricula were the One Health Principles and Concept Module, Infectious Disease Management, Outbreak Investigation and Response, Gender and One Health, One Health Leadership and Ecosystem Health modules. Table 5 shows a summary of different disciplines, programs and number of courses that had One Health core competencies and modules integrated into them in the OHCEA institutions.

Table 5.

Courses and programs with One Health content integrated into them across OHCEA institutions.

| Country | No of courses | Disciplines/ programs in which One Health was integrated into courses (both undergraduate and graduate level programs) |

|---|---|---|

| Rwanda (University of Rwanda) |

29 | Public Health, Veterinary Medicine, Environmental Sciences, Nursing |

| Ethiopia (Jimma and Mekelle University) |

30 | Public health, veterinary medicine, Environmental sciences, Agriculture, Epidemiology |

| Kenya (Moi University) |

15 | Medicine, Epidemiology, Environmental Health, Nutrition, Occupational, Safety and health, Food science and Technology |

| Cameroon (Universite des Montagne and University of Buea) |

44 | Agriculture, General science, Environmental science, plant genetics, Environmental science, Chemistry, Engineering, Psychology |

| Senegal (Ecole Inter Etats Des Science Vétérinaires {EISMV}) |

27 | Veterinary Medicine, Public health, Environmental sciences |

Besides specific course integration, other countries are using a different format to include One Health training in programs and curricula using the modules. Tanzania is currently integrating One Health core competencies and content from these modules into the national training curricula for diploma and certificate programs for clinical officers, mid-wifery and nursing, vet technicians and livestock production officers, environmental sciences, wildlife technicians, laboratory and pharmacy across the country. In Uganda, 6 modules are the cornerstone of the One Health Institute, Makerere University's summer training program. The modules used are: One Health Leadership, infectious disease management; Gender and One Health, Outbreak investigation and emergency response. Over the past one year, the Democratic Republic of Congo has used the draft outbreak investigation and response module and the One Health leadership modules to train government territory administrators in 10 districts around the country, in outbreak preparedness, response and leadership targeting frontline workers and first responders.

Aside from the integration into curricula and courses, multiple university institutions in Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo trained a multidisciplinary team of final year students using the infectious disease management module. The students were from medicine, veterinary medicine, nursing, agriculture, environment, biotechnology, etc. A total of 617 students entering the public health workforce were exposed to these multidisciplinary and cross sectoral one health skills and competencies prior to graduating in 2017. OHCEA is building a cadre of people who are competent training using the One Health modules while at the same time ensuring that these modules are mainstreamed and integrated into the curricula across its institutions. OHCEA is also in the process of developing a One Health online course based on these modules that will offer students across its network countries an opportunity to take the course at their own pace. In this coming year, OHCEA will be launching One Health continuous professional development courses for veterinary, medical, pharmacy and environmental organizations across the region, and as the modules are revised, plans are underway to use them as basis for the development of undergraduate, and graduate level One Health inclusive programs in the region.

8. Conclusion

The OHCEA One Health modules have been in development for a period of two years. The development process involved people from eight different countries making it a slow and rigorous process. Considering that One Health training is a relatively new field, data, literature and materials were not easy to come by and faculty had to be innovative to develop relevant case studies and instructional material. The intent was that the material developed should be learner centered and very interactive, which required that developers be trained to use interactive teaching methodologies and to include those in the modules. These modules are dynamic and iterative and will be undergoing continuous review process as they are used.

The One Health modules provide the knowledge skills and behaviors needed for effective performance of a One Health workforce, can be used to identify gaps in existing public health training programs and as frameworks to evaluate current training programs. The modules have been developed in such a way as to be integrated into existing courses and curricula, as standalone modules or for sections of a module to be used in meetings or practicums. They can be used to guide One Health curriculum design at certificate, undergraduate and graduate levels emphasizing One Health approaches and to pinpoint additional opportunities where One Health can be added in traditional and existing curricula. They are designed to fill the cross sectoral skill gap caused by the changes in public health practice and to provide formal training in both the soft and the technical skills. Ultimately, the One Health modules allow the current and future workforce to gain a comprehensive understanding of concepts and principles of One Health including the scope, historical perspectives, and how to apply the One Health principles to create stronger and more efficient integrated health systems with inputs from multiple stakeholders.

One Health training aspires to equip the workforce with the basic technical and non-technical skills and competencies that can complement their own specific areas of expertise necessary for One Health practitioners, regardless of discipline. The One Health modules are pertinent and timely. The use of the one Health competencies and module can be used to transform the training of public health professionals and create a multi-sectoral workforce well prepared for the changing complex global health challenges.

Funding source

This project was financially supported by funding provided to the One Health Central and Eastern Africa Network, OHCEA through a grant received from the United Stated Agency for International Development, USAID-One Health Workforce project, a part of the Emerging Pandemics Threat 2 Program-Grant USAID GH/HIDN-Award no AID-OAA-A-15-00014.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the faculty from across the OHCEA institutions and countries who participated in all the different training and workshops and worked tirelessly to develop the OHCEA One Health modules.

Contributor Information

Hellen Amuguni, Email: Janetrix.amuguni@tufts.edu.

Winnie Bikaako, Email: Wbikaako@ohcea.org.

Irene Naigaga, Email: inaigaga@ohcea.org.

William Bazeyo, Email: wbazeyo@musph.ac.ug.

References

- 1.Daszak P., Zambrana-Torrelio C., Bogich T.L. Proceedings of the National Academy of the United States of America. 2012. Interdisciplinary approaches to understanding disease emergence: The past, present and future drivers of Nipah virus emergence.http://www.pnas.org/content/110/Supplement_1/3681.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html

- 3.Heyman D.L., Chen L., Takemi K. Global health security: the wider lessons from the West African Ebola virus disease epidemic. Lancet Public Policy. 2015;385(9980):1884–1901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60858-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Veterinary Medical Association . One Health: A New Professional Imperative; 2008. One Health Initiative Task Force.https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/Reports/Documents/onehealth_final.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett M.A., Osofsky S.A. “One Health: Interdependence of People, Other Species, and the Planet,” pp. 364–377 (and online supplement pp. 407(e1)–416(e10) at studentconsult.com) In: Katz D.L., Elmore J.G., Wild D.M.G., Lucan S.C., editors. Jekel's Epidemiology, Biostatistics, Preventive Medicine, and Public Health. 4th ed. Elsevier; Saunders, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhutta Zulfiqar A., Chen Lincoln, Cohen Jordan, Crisp Nigel, Evans Tim, Fineberg Harvey, Garcia Patricia, Horton Richard, Ke Yang, Kelley Patrick, Kistnasamy Barry, Meleis Afaf, Naylor David, Pablos-Mendez Ariel, Reddy Srinath, Scrimshaw Susan, Sepulveda Jaime, Serwadda David, Zurayk Huda. Education of health professionals for the 21st century: a global independent Commission. Lancet. 3–9 April 2010;375(9721):1137–1138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.www.ohcea.org

- 8.Salzburg Global Seminar New Century, New Challenges, New Dilemmas: The Global Nexus of Animal and Public Health. 2007. http://archive.salzburgglobal.org/current/sessions-b.cfm?IDSpecial_Event=1266 Available from:

- 9.Prahalad C.K., Hamel G. The core competence of the corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990;68(3):79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenk J., Chen L., Bhutta Z.A., Cohen J., Crisp N., Evans T. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. (PubMed] [Cross Ref) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calhoun J.G., Ramiah K., Weist E.M., Shortell S.M. Development of a core competency model for the master of public health degree. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98:1598–1607. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117978. (PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankson Rebekah, Hueston William, Christian Kira, Olson Debra, Lee Mary, Valeri Linda, Hyatt Raymond, Annelli Joseph, Rubin Carol. One Health Core Competency Domains. Front. Public Health. 2016;4:192. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone Mountain Meeting Workgroups . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2012. Stone Mountain Meeting Newsletter. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global OHCC Working Group . United States Agency for International Development Respond Initiative; Washington, DC: 2013. One Health Core Competency Domains, Subdomains, and Competency Examples. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigielman Richard, Albertine Susan. Association for Prevention Teaching and Research/ Association of American Colleges and Universities. October 2008. Recommendations for Undergraduate Public Health Education. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiggins Grant, McTiighe Jay. 2018. Understanding by Design, Book Published in 2005 by Pearson Education and the Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development. [Google Scholar]

- 17.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloom%27s_taxonomy

- 18.https://seaohunonehealth.wordpress.com/

- 19.http://www.ohcea.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=163&Itemid=232