Abstract

A natural fat-soluble thiamine derivative, namely N-[(4-amino-2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl)methyl]-N-[(2E)-5-hydroxy-3-(prop-2-en-1-yldisulfanyl)pent-2-en-2-yl]formamide (allithiamine) has been identified only in garlic (Allium sativum) until now. Hungarian red sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum) was found as a new source of allithiamine. Extraction procedure and analytical method were developed for the isolation of allithiamine and a chemical synthesis of the compound was also developed. First solid-liquid extraction was performed with 96 % ethanol to isolate allithiamine from pepper seeds. Thereafter, solid phase extraction was applied from ethanolic extract using C18 cartridge to concentrate and purify samples for further analysis. The structure of the synthesized and the isolated compounds was verified by reverse phase HPLC, HPLC-MS, MALD-TOF MS and NMR. Furthermore, effect of allithiamine was investigated on streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice with neuropathy. The results show that neuropathic pain sensation is improved by allithiamine treatment similarly to benfothiamine.

Keywords: Analytical chemistry, Food science

1. Introduction

Thiamine, known as vitamin B1, has key role in energy metabolism (Lonsdale, 2006). It is the starting compound of thiamine pyrophosphate which is a cofactor of enzymes in catabolism of glucose in glycolysis (piruvate dehydrogenase, EC 1.2.1.5, transketolase, EC 2.2.1.1) and in citrate cycle (α-ketoglutarate-dehydrogenase, EC 1.2.4.2) (Kern et al., 1997). Modern western diet is loaded with simple carbohydrates results in high calorie malnutrition. Breakdown of glucose, processed in the body from carbohydrates, automatically increases the need for this vitamin (Elmadfa et al., 2001).

In case of thiamine deficiency serious symptoms occur. The name of syndrome is beriberi, which was relatively common in Asia. Consequently extensive research has been conducted primarily in Japan (Vitamin B Research Committee) in the middle of 20th century (Shimazono et al., 1965) resulting expansion of knowledge. Scientist observed a compound which shows thiamine effect in vivo. This property was kept in presence of known thiamine inactivating agents. This compound has been named as allithiamine because it was isolated from the genus Allium (Fujiwara et al., 1954). Allithiamine was the first and only natural fat-soluble thiamine derivative, which has been identified only in the Allium genus so far. This step was the basis for further research (Matsukawa et al., 1954). Lipid-soluble thiamine analogues were developed after the discovery of allithiamine. These lipophilic compounds are often referred to as “allithiamines”. This denomination is improper because these synthetic molecules are not present in Allium species and do not possess any allyl group (Volvert et al., 2008).

The absorption of apolar thiamine derivatives is significantly faster compared to thiamine hydrochloride (Balakumar et al., 2010). Fursulthiamine (Lonsdale, 2004), sulbuthiamine (Van Reeth, 1999) and benfothiamine (Balakumar et al., 2010) are synthetic derivatives of thiamine and have been used as therapeutic agents in human medicine. Several studies showed that unphosphorylated thiamine and primarily benfothiamine can be used effectively in preventive therapy of diabetic complications (Berrone et al., 2006; Hammes et al., 2003; Marchetti et al., 2006; Wu and Ren, 2006).

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic, endocrine disorder with serious complications (Golbidi et al., 2012), which are causing different economic, social and consequently mental damages in societies of 21st century (Zimmet et al., 2001). Moreover latest prognosis of World Health Organization (WHO) predicted an increasing prevalence of DM. DM is accompanied by hyperglycaemia that has a central role of degeneration of microvasculature. Harmful intermediates and consequential oxidative stress can be responsible for abnormality of microvasculature and consecutive tissue damages (Brownlee, 2005). Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is one of the most common consequences of the diabetes if hyperglycaemia persists. The pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy has remained the subject of research. Nevertheless there seems to be a close relationship between the degree and duration of hyperglycaemia and the consequential alternative pathological pathways (Singh et al., 2014). Symptoms of serious diabetic neuropathy are painful and result in such a physical and mental condition in which patient's quality of life is significantly and continuously deteriorated (Padua et al., 2005). Many studies suggest that fat-soluble thiamine derivatives are able to prevent progression of neuropathy (Haupt et al., 2005). One of the possible reason is the predominantly apolar environment in the neuronal tissue.

Plant origin active agents play critical roles in modern drug development and in treatment or prevention of human diseases (Rauf and Jehan, 2017). Related disciplines such as nutritional science and functional food science have significant influences in human medicine, food production and eating habits. Their importance will probably increase in the future. Furthermore more and more studies focus on investigating of plants which can be a new source of well-known and characterized compounds (Homoki et al., 2016; Regueiro et al., 2014).

These were kept in mind during our experiments when we searched a new source of allithiamine. Recently, there is a growing interest in the use of by-products of food processing, because several agricultural products are under-utilized (Sharma et al., 2016; Schieber et al., 2001). In case of pepper only a small part of the plant material is used directly for human consumption (El-Adawy and Taha, 2001). Pepper seeds are also defined as food waste, although the chemical composition and biological properties of C. annuum seeds are excellent (Silva et al., 2013). Several studies have reported that the sterol content (Matthäus and Özcan, 2009), fatty acid composition (Marion and Dempsey, 1964), and antioxidant activity (Sim and Sil, 2008) of pepper seeds is outstanding and its further processing should be considered.

In our experiments Hungarian red sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum) seeds were tested whether allithiamine is present in other plants outside of the Allium genus. We examined the effect of pure allithiamine in a diabetic mice model with particular regard of neuropathy.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis and verification of allithimine

During our experiments we used the synthetic route described by Matsukawa (Matsukawa et al., 1954) with minor modifications. During the synthesis of allithiamine a wide variety of thiamine derivatives and other by-products were also observed. Based on the chromatographic peaks, only 39 % of the end product was allithiamine. To separate the products a semi-preparative method was used applying reversed phase column and gradient elution described in 2.2.2 section. Allithiamine was eluted at 30.5 min (shown in Fig. 1), as we identified with MALDI-TOF and 13C-NMR spectra, which can be seen in the Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of a synthetic mixture.

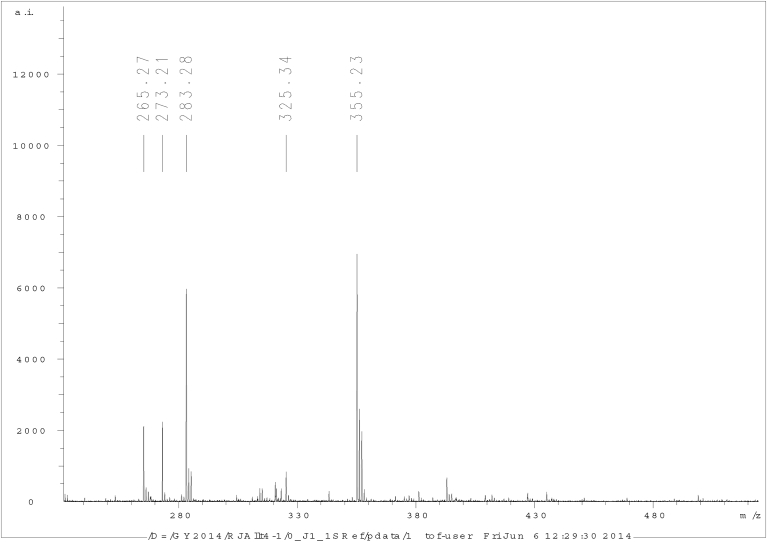

Fig. 2.

MALDI-TOF spectrum of purified allithiamine.

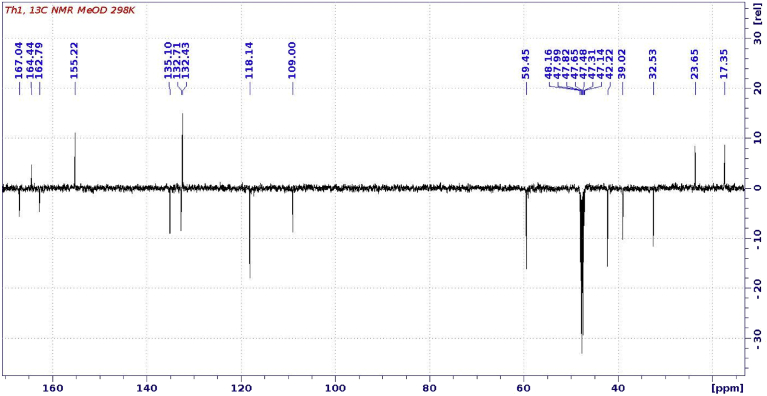

Fig. 3.

13C-NMR spectrum of purified allithiamine.

1H-NMR spectral assignment was based on COSY 1H-1H connectivities. 13C- shifts of protonated carbons were assigned from the HSQC spectrum, while long-range carbon-proton couplings observed in HMBC spectrum aided the assignments of quaternaries. Assigned chemical shifts were in acceptable agreement obtained by the ACD spectrum prediction algorithm.

Both methods clearly demonstrated that isolated HPLC fraction contained N-[(4-amino-2-methylpyrimidin-5-yl)methyl]-N-[(2E)-5-hydroxy-3-(prop-2-en-1-yldisulfanyl)pent-2-en-2-yl]formamide, also known as allithiamine.

2.2. Extraction of allithiamine from pepper seeds and its fragmentation by HPLC-MS

The main purpose of our work was to examine whether allithiamine is accumulated in other plant outside of the Allium genus. Seeds of plant were selected for our investigations because it is well-known that plant seeds store large amount of thiamine which is essential for seed germination. In carbohydrate and protein storage plants it has been described that thiamine is bound to proteins (TBP-thiamine binding protein). The level of protein-bound thiamine is much higher than the amount of free thiamine (Gołda et al., 2004). The question then arises: how the thiamine is stored in oil storage seeds, in which protein content is low and the apolar environment is typical.

We first examined seeds of Hungarian red sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum). An isolation protocol was developed which is capable for extraction of accumulated allithiamine. Liquid-liquid and solid phase extractions were performed. As a result of these extraction procedures several components have been obtained. These compounds were separated with reversed phase HPLC method described in 2.2.6 section. Allithiamine was eluted at 20.8 min see, as we identified with HPLC-MS method, the chromatogram is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

HPLC chromatogram of purified pepper seed oil.

Four characteristic fragment ions were detected in the course of the fragmentation experiments. MS2 spectrum of allithiamine can be seen in the Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

MS2 spectrum of allithiamine.

Fragment ion at m/z 281.1061 was formed by the cleavage of S-S bond of the protonated allithiamine. Same fragmentation route followed by the loss of the carbonyl group led to the fragment ion at m/z 253.1112. Next fragment ion at m/z 167.0924 resulted from cleavage of the N-C bond on the side chain of the protonated allithiamine. The fourth fragment ion at m/z 122.0712 was observed after the loss of the whole side chain of the protonated molecule by inductive cleavage of the bond between the nitrogen atom of the side chain and the carbon atom coupled to the pyrimidine ring. Illustration of most probable fragmentation pathways is included in Supplement as “Fragmentaton pathways of allithiamine”.

2.3. Results of the animal experiment

In the last years several studies suggested that sulphur-containing compounds of Allium species could have a beneficial effect in human health (Bayan et al., 2014) (Banerjee and Maulik, 2002). Effect of the synthetic allithiamine analogues are well known and are used against degeneration of neural tissue, including diabetic neuropathy (Haupt et al., 2005). An experimental diabetic study has recently been published results of the effects of benfothiamine on neuropathic pain sensation (Nacitarhan et al., 2014). We examined the effect of allithiamine in animal experiments on neuropathic pain sensation using tail flick test.

2.3.1. Effect of allithiamine and benfotiamine on tail-flick latency

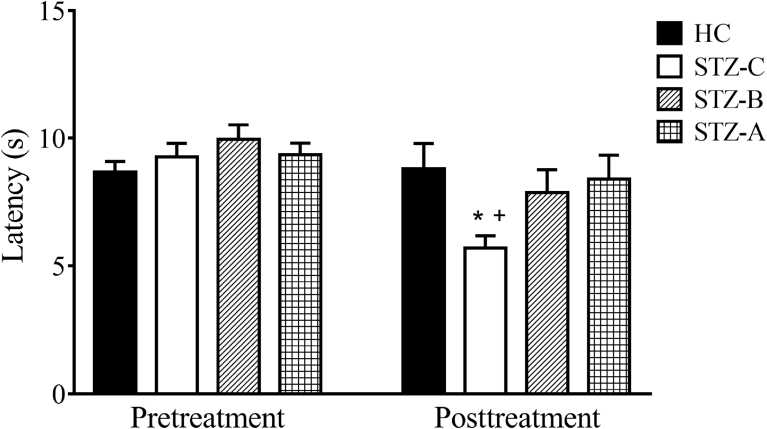

Results of the tail-flick test are shown in Fig. 6. Before the initiation of drug treatment, there were no significant difference in the tail flick latencies among the HC, STZ-C, STZ-A and STZ-B groups. After a 5 week of drug treatment, both benfotiamine and allithiamine were able to effectively increase the tail flick time latency, indicating improvement in neuropathic pain sensation in STZ-treated diabetic mice.

Fig. 6.

Effect of allithiamine and benfothiamine on latency time of experimental. * indicates significant difference in tail flick latency between pre-treatment and post treatment STZ-C group. + indicates significant difference in tail flick latency between posttreatment STZ-C and HC, STZ-B, STZ-A groups.

3. Conclusion

First, in our experiments allithiamine was synthesized using the route described by Matsukawa et al. with minor changes. We wanted to produce pure allithiamine in order to investigate a compound which has not been examined for a long time. We developed instrumental analytical system to identify allithiamine with high accuracy. Analytically pure allithiamine was obtained. This reference compound was used in further investigations. We supposed that the occurrence of allithiamine in flora is more common than the previous knowledge suggested. To prove this assumption Hungarian red sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum) seeds were investigated. Novel extraction technique was developed which facilitated the separation of allithiamine present in the extract of the pepper seed. HPLC-MS method was applied for identification of allithiamine. We found that allithiamine is accumulated in the seeds of Hungarian red sweet (Capsicum annuum) pepper. This result also expands the knowledge of the chemical composition of pepper. It should consider investigating other plant, with special regard to oilseeds.

Second, allithiamine was examined – to our knowledge, for the first time – and compared to benfothiamine within the framework of pilot experiments using STZ-induced diabetic mice with neuropathy. After a 5 week of drug treatment, both benfotiamine and allithiamine were able to effectively increase the tail flick time latency, indicating improvement in neuropathic pain sensation in STZ-treated diabetic mice. Since these data are results of pilot study therefore it is not suitable for drawing far-reaching conclusions. Nevertheless, the results seem to be very interesting and can be the basis of further experiments.

4. Experimental

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Plant samples

Kapia, a red sweet pepper was selected for investigations. We received pepper samples from Agricultural Research and Educational Farm of the University of Debrecen. Samples after picking were immediately frozen, and carried to the laboratory where they were kept in dark at −20 °C.

4.1.2. Chemicals

Allyl chloride, Sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3), tetrabutyl ammonium chloride (TBAC), thiamine hydrochloride, sodium chloride, ammonium phosphate ((NH4)PO4), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4), potassium hydrogen phosphate (KHPO4) potassium citrate (Na3C6H5O7) sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH), streptozotocin (STZ) benfothiamine was obtained from Sigma Aldrich.

Toluene, ethanol, methanol was obtained from VWR.

StrataTM-X-C 200 mg/3 ml, a polymeric strong cation exchange functionalised polymer SPE tube, was bought from Phenomenex Torrance (USA).

Ultra-pure water was obtained from a Millipore (Bedfore, MA, USA) Milli-Q plus system.

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Procedure of chemical synthesis of allithiamine

Synthesis of allithiamine was carried out based on the experiments by Matsukawa et al. with minor changes. Chemical synthesis scheme can be seen in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of chemical synthesis of allithiamine.

Allyl chloride was dissolved in toluene and sodium thiosulfate was dissolved in water. Organic and aqueous phase was mixed and stirred at 25 °C for 24 hours. Tetrabutyl ammonium chloride (TBAC) was added to the mixture to ensure maximal miscibility of the solutions. After the 24-hour stirring the reaction mixture was evaporated at 40 °C in 72–77 mbar with BÜCHI ROTAVAPOR R-210 (Switzerland). Residual fraction was stored at −20 °C and used in the further steps of synthesis.

Thiamine hydrochloride was dissolved in water at 60 °C, at pH 9. During the reaction sodium chloride was added to the mixture. Reaction of thiamine hydrochloride with opening thiazole ring and allyl thiosulfate resulted in different thiamine derivatives.

4.2.2. Purification of the allithiamine with HPLC-system

Measurements were carried out using Merck-Hitachi LaChrom liquid chromatograph, equipped with diode array detector L-7455, automatic sampler L-7250 interface L-7000, pump L7100 and HPLC System Manager Software.

Allithiamine was analysed on a LiChroCART® 250-10 RP-18 column (12 μm) using gradient elution. Eluent A was 0,011 M potassium-dihydrogen-phosphate in water pH = 4,5; eluent B was methanol. After the optimization of the HPLC conditions the following gradient steps were applied:

0–5 min solvent A 100%,

5–10 min solvent B to 10%,

10–30 min solvent B to 35%,

30–35 min solvent B to 62%.

30–50 min solvent A to 90%

Flow rate was 3 ml min−1 and oven temperature was kept at 25 °C. UV detection was used at 250 nm wavelength.

4.2.3. Verification of allithiamine with MALDI-TOF MS

MALDI spectra of allithiamine samples were obtained in positive-ion mode using a Bruker Biflex MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with delayed-ion extraction. Desorption/ionisation of the sample molecules was effected with a 337 nm nitrogen laser. Spectra from multiple (at least 100) laser shots were summarised using 19 kV accelerating and 20 kV reflectron voltage. External calibration was applied using the [M+Na]+ peaks of cyclodextrins DP 6–8, m/z: 995.31, 1157.36, 1319.41 Da, respectively. All the spectra was obtained in 2,5-dihydroxy benzoic acid (DHB) matrix. The samples were dissolved in EtOH. 10 μL sample and 10 μL matrix solution were mixed, then 0.5 μL was applied to the sample target and allowed to dry at room temperature. The calculated values used for comparison were derived from IUPAC exact isotopic weights using XMASS 5.0 software from Bruker.

4.2.4. Verification of allithiamine with nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR)

Bruker Avance -II, NMR spectrometer of 500.13 MHz 1H resonance frequency was applied, and txi-gradient probe was used at 298 K. Methanol-d4 was used as solvent, and chemical shifts were referenced to residual solvent signals (3.33 and 47.65 ppm for 1H and 13C, respectively). For signal assignment 2D COSY, HSQC and HMBC spectra were recorded with pulse programs of the manufacturer.

4.2.5. Sample preparation

Illustration of sample preparation can be seen in Fig. 8. Ovary of pepper was separated from meat of pepper by hand. Thereafter the seeds were lyophilized (ALPHA 1-4 LSC) for 24 hours and stored at −20 °C until use. The pepper seeds were homogenized by seed grinder. The samples were extracted with ethanol for 1 hour using Magnetic stirrer MSH 300 (BIOSAN). Solvent was evaporated at 40 °C in 175 mbar with BÜCHI ROTAVAPOR R-210 (Switzerland) until oil drops appeared. Thereafter, the samples were centrifuged (SIGMA 2-16 SARTORIUS) for 5 min 10 000 min−1. Supernatant was added to phosphate buffer forming 1:1 mixture, which was centrifuged (SIGMA 2-16 SARTORIUS) for 5 min 10 000 min−1. Lower phase was further purified. Fractionation of pepper seed extract was performed using preconditioned Strata-X-C cartridges in cation exchange mode. Conditioning of cartridges was performed with 6 ml methanol then with 6 ml of phosphate buffer, pH = 3. 1.5 ml sample was eluted with 2 % formic acid then methanol and finally methanol containing 5 % NH4OH. The latter fraction was collected and evaporated. Samples were dissolved in 100 μl ethanol prior to HPLC analysis.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of sample preparation.

4.2.6. Analysis of purified fraction with HPLC-system

Measurements were carried out using the instrumental system described in Section 2.2.2. The fraction obtained after solid phase extraction was analysed on a Supelcosil LC-8 DB column (5 μm, 150 mm × 4.1 mm) using gradient elution. Eluents A was 0,011 M potassium-dihydrogen-phosphate in water pH = 4,5; eluent B was methanol. HPLC running conditions consisted of the following linear gradient steps:

5 min solvent A 100%,

5–10 min solvent B to 10%,

10–30 min solvent B to 35%,

Flow rate was 2 ml min−1 and oven temperature was kept at 25 °C. UV detection was used at 250 nm wavelength.

4.2.7. HPLC-MS/MS fragmentation experiments

Prior to MS a reversed-phase chromatographic separation was used. 10 μl of standard solution of allithiamine was injected to a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 RS system equipped with a Thermo Accucore C18 column (100/2.1, 2.6 μm). Eluent A (500 ml of water containing 10 ml of methanol, 0.5 ml of formic acid and 2.5 mM of ammonium formate (pH 2.7) and eluent B (500 ml of methanol containing 10 ml of water, 0.5 ml of formic acid and 2.5 mM of ammonium formate) were mixed in 50–50%. Flow rate was 0.2 ml/min. The chromatography system was coupled to a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization source (ESI). The mass spectrometer was operated with the following parameters: capillary temperature 320 °C, spray voltage 4.0 kV, the resolution was set to 70000. The mass range scanned was 100–1000 m/z. The maximum injection time was 100 ms. Sheath gas flow rate was 32 arb, aux gas flow rate was 7 arb.

Fragmentation of allithiamine was studied in positive ionisation mode at 40 Normalized Collision Energy (NCE).

4.2.8. Animal experiments

4.2.8.1. Ethical aspects

Study protocol was formally approved by the University of Debrecen Animal Ethics Committee. The experiments presented conform to European Community guiding principles for the care and use of laboratory animals. The experimental protocols applied had been approved by the local ethical boards of the University of Debrecen, Hungary (26/2012 DE MÁB).

4.2.8.2. Animals and diabetes induction

Sixty male C57BL/6J mice (29-35 g) were used throughout the study. After arrival the animals were placed in quarantine for a week. This period also served for acclimatization. Mice were housed in an animal room within the temperature range of 22–25 °C and the relative humidity range of 50–70%. Light/dark cycle was set to lights on at 7:00 am and off at 7:00 pm. After the acclimatization period animals were randomized into 4 treatment groups 15 mice per group as follows. One week after a preliminary tail flick test to determine initial pain sensation insulin dependent diabetes was induced by means of streptozotocin (STZ), 200 mg/kg intraperitoneally in three groups. Mice assigned to the fourth group were injected intraperitoneally with the vehicle of STZ (100 mM citrate buffer with pH set at 4.5). These mice served as the healthy control (HC) group. A week after STZ treatment, fasting blood glucose was measured from a drop of blood obtained from the tail by cutting its tip. All mice became diabetic one week after STZ treatment, so none of the mice had to be excluded from the experiment due to insufficient diabetes induction.

4.2.8.3. Allithiamine, benfotiamine treatment

Drug treatment was commenced after a week of STZ treatment. Animals were treated once a day with oral dose of 100 mg/kg allithiamine (STZ-A group) or benfotiamine (STZ-B group) over 5 weeks in a solution concentration of 30 mg/ml that ensured that the daily given volume does not exceed 0.15 ml. Both HC and diabetic control (STZ-C group) mice received drug vehicle (ethyl alcohol:water 1:9). The dose selection was based on the literature that proved to be effective to significantly elevate the thiamine level in the blood as well as in the liver (Volvert et al., 2008).

4.2.8.4. Tail flick test

The effect of benfotiamine and allithiamine on pain sensation in diabetic mice was assessed by means of the tail flick test. One week prior to the commencement of treatment (vehicle, benfotiamine or allithiamine) mice were habituated to the testing procedures and handling by the investigator. The test is based on the measurement of the tail-flick latency after immersion of the tail in a hot water bath of 49 ± 0.5 °C. Latency time was determined by a vigorous tail flick. In order to prevent tissue damage, a cut-off time of 15 s was applied. If an animal reached this cut-off time, then the tail was removed from the water, and the animal was assigned the maximum score. The pretreatment values were determined a week before the diabetes induction, while the post treatment value was determined on the 33nd day of the treatment.

4.2.9. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard error of means. Data were statistically analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a modified t-test for repeated measures according to Tukey's method. The level of significance was set at p < 0,05.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Attila Biro: Performed the experiments.

Ferenc Gál, Csaba Hegedűs, Barna Peitl: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Gyula Batta, Zoltán Cziáky, László Stündl, Gyöngyi Gyémánt: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Judit Remenyik: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the EU and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund under the project GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00042. Higher Education Institutional Excellence Programme (20428-3/2018/FEKUTSTRAT) of the Ministry of Human Capacities in Hungary.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sándor Biró for the helpful advices and corrections. This study is dedicated to Professor Sándor Biró on the occasion of his 70th birthday, and we honor his undisputed merits in the field of the microbial genetics.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Fragmentaton pathways of allithiamine.

References

- Balakumar P., Rohilla A., Krishan P., Solairaj P., Thangathirupathi A. The multifaceted therapeutic potential of benfotiamine. Pharmacol. Res. 2010;61:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S.K., Maulik S.K. Effect of garlic on cardiovascular disorders: a review. Nutr. J. 2002;1 doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-1-4. 4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayan L., Koulivand P.H., Gorji A. Garlic: a review of potential therapeutic effects. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2014;4:1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrone E., Beltramo E., Solimine C., Ape A.U., Porta M. Regulation of intracellular glucose and polyol pathway by thiamine and benfotiamine in vascular cells cultured in high glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9307–9313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Adawy T.A., Taha K.M. Characteristics and composition of watermelon, pumpkin, and paprika seed oils and flours. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:1253–1259. doi: 10.1021/jf001117+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmadfa I., Majchrzak D., Rust P., Genser D. The thiamine status of adult humans depends on carbohydrate intake. Int. J. Vitamin Nutr. Res. 2001;71:217–221. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.71.4.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M., Watanabe H., Matsui K. “Allithiamine” a newly found derivative of vitamin B1I. Discovery of allithiamine. J. Biochem. 1954;41:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Golbidi S., Badran M., Laher I. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of exercise in diabetic patients. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:941868. doi: 10.1155/2012/941868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gołda A., Szyniarowski P., Ostrowska K., Kozik A., Rąpała-Kozik M. Thiamine binding and metabolism in germinating seeds of selected cereals and legumes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2004;42:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes H.P., Du X., Edelstein D., Taguchi T., Matsumura T., Ju Q., Lin J., Bierhaus A., Nawroth P., Hannak D., Neumaier M., Bergfeld R., Giardino I., Brownlee M. Benfotiamine blocks three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage and prevents experimental diabetic retinopathy. Nat. Med. 2003;9:294–299. doi: 10.1038/nm834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt E., Ledermann H., Kopcke W. Benfotiamine in the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy–a three-week randomized, controlled pilot study (BEDIP study) Int. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2005;43:71–77. doi: 10.5414/cpp43071. PMID: 15726875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homoki J.R., Nemes A., Fazekas E., Gyémánt G., Balogh P., Gál F., Al-Asri J., Mortier J., Wolber G., Babinszky L., Remenyik J. Anthocyanin composition, antioxidant efficiency, and α-amylase inhibitor activity of different Hungarian sour cherry varieties (Prunus cerasus L.) Food Chem. 2016;194:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern D., Kern G., Neef H., Tittmann K., Killenberg-Jabs M., Wikner C., Schneider G., Hubner G. How thiamine diphosphate is activated in enzymes. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1997;275:67–70. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdale D. Thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide: a little known therapeutic agent. Med. Sci. Monit. 2004;10:RA199–RA203. PMID:15328496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdale D. A review of the biochemistry, metabolism and clinical benefits of thiamin(e) and its derivatives. Evid Based Compl. Alternat. Med. 2006;3:49–59. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nek009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti V., Menghini R., Rizza S., Vivanti A., Feccia T., Lauro D., Fukamizu A., Lauro R., Federici M. Benfotiamine counteracts glucose toxicity effects on endothelial progenitor cell differentiation via Akt/FoxO signaling. Diabetes. 2006;55:2231–2237. doi: 10.2337/db06-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion J.E., Dempsey A.H. Fatty acids of pimiento pepper seed oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1964;41:548–549. [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa T., Kawasaki H., Iwatsu T., Yurugi S. Syntheses of allithiamine and its homologues. J. Vitaminol. 1954;1:13–26. doi: 10.5925/jnsv1954.1.13. PMID:13243522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus B., Özcan M.M. Chemical evaluation of some paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) seed oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2009;111:1249–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Nacitarhan C., Minareci E., Sadan G. The effect of benfotiamine on mu-opioid receptor mediated antinociception in experimental diabetes. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2014;122:173–178. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padua L., Schenone A., Aprile I., Benedetti L., Caliandro P., Tonali P., Orazio E.N. Quality of life and disability assessment in neuropathy: a multicentre study. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2005;10:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.10103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauf A., Jehan N. Natural products as a potential enzyme inhibitors from medicinal plants. In: Senturk M., editor. Enzyme Inhibitors and Activators. InTech; Rijeka: 2017. Ch. 07. [Google Scholar]

- Regueiro J., Sánchez-González C., Vallverdú-Queralt A., Simal-Gándara J., Lamuela-Raventós R., Izquierdo-Pulido M. Comprehensive identification of walnut polyphenols by liquid chromatography coupled to linear ion trap–Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2014;152:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber A., Stintzing F.C., Carle R. By-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds — recent developments. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001;12:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.K., Bansal S., Mangal M., Dixit A.K., Gupta R.K., Mangal A.K. Utilization of food processing by-products as dietary, functional, and novel fiber: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;56:1647–1661. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.794327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazono N., Katsura E., Bitamin B.K.I. Vitamin B Research Committee of Japan; Kyoto: 1965. Review of Japanese Literature on Beriberi and Thiamine. [Google Scholar]

- Silva L.R., Azevedo J., Pereira M.J., Valentao P., Andrade P.B. Chemical assessment and antioxidant capacity of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seeds. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;53:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim K.H., Sil H.Y. Antioxidant activities of red pepper (Capsicum annuum) pericarp and seed extracts. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008;43:1813–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Kishore L., Kaur N. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: current perspective and future directions. Pharmacol. Res. 2014;80:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeth O. Pharmacologic and therapeutic features of sulbutiamine. Drugs Today (Barc) 1999;35:187–192. doi: 10.1358/dot.1999.35.3.533848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volvert M.L., Seyen S., Piette M., Evrard B., Gangolf M., Plumier J.C., Bettendorff L. Benfotiamine, a synthetic S-acyl thiamine derivative, has different mechanisms of action and a different pharmacological profile than lipid-soluble thiamine disulfide derivatives. BMC Pharmacol. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Ren J. Benfotiamine alleviates diabetes-induced cerebral oxidative damage independent of advanced glycation end-product, tissue factor and TNF-alpha. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;394:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet P., Alberti K.G., Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–787. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]