Abstract

AIM

To investigate the main current etiologies of cirrhosis in Mexico.

METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional retrospective multicenter study that included eight hospitals in different areas of Mexico. These hospitals provide health care to people of diverse social classes. The inclusion criteria were a histological, clinical, biochemical, endoscopic, or imaging diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. Data were obtained during a 5-year period (January 2012-December 2017).

RESULTS

A total of 1210 patients were included. The mean age was 62.5 years (SD = 12.1), and the percentages of men and women were similar (52.0% vs 48.0%). The most frequent causes of liver cirrhosis were hepatitis C virus (HCV) (36.2%), alcoholic liver disease (ALD) (31.2%), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (23.2%), and the least frequent were hepatitis B virus (1.1%), autoimmune disorders (7.3%), and other conditions (1.0%).

CONCLUSION

HCV and ALD are the most frequent causes of cirrhosis in Mexico. However, we note that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as an etiology of cirrhosis increased by 100% compared with the rate noted previously. We conclude that NAFLD will soon become one of the most frequent etiologies of liver cirrhosis in Mexico.

Keywords: Alcoholic liver disease, Hepatitis C virus, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Liver cirrhosis

Core tip: In 2004, a Mexican study reported the most common causes of liver cirrhosis were alcoholic liver disease (39.5%), hepatitis C virus (36.6%), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (10.4%). We believe that the epidemiology of cirrhosis has changed because of the increasing prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and autoimmune diseases. Therefore, we performed a cross-sectional multicenter study that included eight hospitals of different areas of Mexico in order to know the current epidemiology of liver cirrhosis in this country.

INTRODUCTION

Liver fibrosis develops as a result of chronic injury to the liver in conjunction with the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins, which occurs in most chronic liver diseases (CLDs)[1]. The accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins distorts the hepatic architecture by forming fibrous scar tissue, and the subsequent development of regenerative nodules within hepatocytes defines cirrhosis[2]. Cirrhosis is the end stage of CLD and leads eventually to portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and liver failure[3].

Liver cirrhosis is a major and underestimated global public health problem as well as an important cause of morbidity and mortality. In 2010, cirrhosis was responsible for an estimated 2% of all deaths worldwide[4]. Current global estimates show that 844 million people have a CLD, and 2 million people die per year because of CLD[5]. The worldwide prevalence rate for CLD is 4.5% to 9%, causing approximately 633000 cases of liver cirrhosis per year[6]. In the United States, CLDs and liver cirrhosis are the 12th leading cause of mortality and account for about 60000 deaths per year[7]. In European countries, liver cirrhosis affects about 0.1% of the populations and causes about 170000 deaths per year[8].

The most common etiologies of liver cirrhosis in developed countries include chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcoholism, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), whereas viral hepatitis, especially that caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, are the main causes in developing countries[7]. However, in many countries, the proportion of liver cirrhosis caused by viral hepatitis is decreasing markedly and the proportion caused by NASH is increasing[9]. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the predecessor condition of NASH, has a current prevalence of 25%-30% worldwide and the highest prevalence rates are in Western countries[10]. Some studies have reported that over 64 million people have NAFLD in the United States and 53 million have NAFLD in Europe[11]. Therefore, it is expected that NAFLD will become the leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality in the next 20 years as well as the main indication for liver transplantation[12]. Unfortunately, NASH is now the second most frequent indication for liver transplantation in the United States[13,14].

In Mexico, alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and HCV infection have been the most frequent causes of liver cirrhosis in the past decade[15]. Nevertheless, the rising prevalence of obesity[16], metabolic syndrome[17], and autoimmune diseases[18] has probably modified the epidemiology of cirrhosis in our country. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the main etiologies of liver cirrhosis in Mexicans. We believe that understanding the epidemiology of liver cirrhosis in the general population is the first step toward developing interventions to decrease this disease burden.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A multicenter cross-sectional retrospective observational study was performed in eight tertiary referral hospitals from different cities of Mexico: Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation (Mexico City), Hospital “Juárez” of Mexico (Mexico City), Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde” (Jalisco), Christus Muguerza “Super Specialty” Hospital (Nuevo León), General Hospital of Mexico “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” (Mexico City), Central Military Hospital (Mexico City), General Hospital of the Mexican Social Security Institute (Durango), and the General Regional Hospital, IMSS 1 (Cuernavaca). The hospitals in our sample come from three geographic regions of Mexico: North, Center, and Mexico City. These hospitals provide medical care to the Mexican population of all ages. The study was conducted from January 2012 to December 2017.

We included patients who were older than 20 years, of both genders, who had been diagnosed with liver cirrhosis of the compensated or decompensated stage. The medical records of all participants were reviewed to obtain information about liver disease categorization and biochemical and imaging data. All eligible patients had received a biochemical, clinical, imaging, or histological diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. The diagnosis of liver disease was categorized as HBV, HCV, autoimmune liver disease, ALD, NASH, or other conditions. Hereditary liver disease or liver cirrhosis resulting from hepatotoxic drugs or toxins was classified into the group of other causes.

We made the histological diagnosis of cirrhosis according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines. The criteria for the categorization of viral hepatitis were positive serological enzyme-linked immunoassay test results for HCV antibody, immunoglobulin G to hepatitis core antigen, and positive surface antigen of HBV. ALD was diagnosed for patients with a history of ethanol consumption ≥ 30 g/d in men or ≥ 20 g/d in women and negativity to viral and autoimmune markers. Consumption of alcohol was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test[19], a widely used screening instrument for unsafe and noxious alcohol consumption.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are expressed as the mean ± SD. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The chi-squared test was used to identify differences between the underlying cause of liver cirrhosis and age groups, gender, and the hospital where patients were treated. Data were analyzed using the statistical program Stata version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The sample comprised 1210 patients (male: female ratio 1:1, mean age 62.5 ± 12.1 years). HCV infection was the most frequent etiology (36.2%), followed by ALD (31.2%), and NASH (23.2%). Other causes of liver cirrhosis included autoimmune liver diseases (7.3%), HBV infection (1.1%), and other conditions (1%) (Table 1). Women accounted for most of the cirrhotic patients with HCV infection (64.8%) and NASH-related cirrhosis (60.5%), and men accounted for 86.7% of patients with liver cirrhosis caused by ALD (P < 0.001). The underlying causes of liver cirrhosis and the gender distribution according to etiology are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Main causes of liver cirrhosis by hospital

|

Virus |

|||||||

| Hospital | n | B | C | Alcohol | NASH | Autoimmune | Others |

| MSC&F | 413 | 8 | 169 | 123 | 71 | 42 | 0 |

| CHG | 156 | 0 | 91 | 45 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| CMH | 100 | 0 | 23 | 25 | 41 | 11 | 0 |

| CMSSH | 113 | 3 | 20 | 26 | 47 | 8 | 9 |

| GHD | 73 | 1 | 6 | 40 | 25 | 1 | 0 |

| GHM | 99 | 0 | 35 | 26 | 24 | 14 | 0 |

| GRH IMSS No.1 | 82 | 0 | 72 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| HJM | 174 | 1 | 22 | 88 | 53 | 7 | 3 |

| Total | 1210 | 13 | 438 | 377 | 281 | 89 | 12 |

| Percentage | 1.1 | 36.2 | 31.2 | 23.2 | 7.3 | 1 | |

| 95%CI | 0.62-1.8 | 33.5-38.9 | 28.6-33.8 | 20.9-25.7 | 6.0-8.9 | 0.56-1.7 | |

| P < 0.001 | |||||||

The distribution of the etiology of liver cirrhosis was higher for hepatitis C virus 36.2%, alcoholic liver disease 31.2% and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 23.2% and lower for hepatitis C virus 1.1%, autoimmune hepatitis 7.3% and other causes 1.0% (P < 0.001). MSC&F: Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation; HJM: Hospital “Juárez” of México; CHG: Civil Hospital of Guadalajara "Fray Antonio Alcalde”; CMSSH: Christus Muguerza “Super Specialty” Hospital; GHM: General Hospital of Mexico "Dr. Eduardo Liceaga"; CMH: Central Military Hospital; GHD: General Hospital of Durango; GRH IMSS No.1: Regional General Hospital IMSS 1; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Table 2.

Main etiologies of liver cirrhosis by gender, n (%)

|

Male (n = 629) |

Female (n = 581) |

|||||||||||||

|

Virus |

Virus |

|||||||||||||

| Hospital | n | B | C | Alcohol | NASH | Auto-inmune | Other | n | B | C | Alcohol | NASH | Autoinmune | Other |

| MSC&F | 217 | 5 | 56 | 110 | 29 | 17 | 0 | 196 | 3 | 113 | 13 | 42 | 25 | 0 |

| (62.5) | (36.4) | (33.6) | (26.1) | (77.3) | 0 | (60.0) | (39.8) | (26.0) | (24.7) | (37.3) | 0 | |||

| CHG | 96 | 0 | 44 | 42 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 47 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | (28.6) | (12.8) | (9.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (16.6) | (6.0) | (5.9) | 0 | 0 | |||

| CMH | 35 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 65 | 0 | 15 | 12 | 29 | 9 | 0 |

| 0 | (5.2) | (4.0) | (10.8) | (9.1) | 0 | 0 | (5.3) | (24.0) | (17.1) | (13.4) | 0 | |||

| CMSSH | 70 | 2 | 11 | 23 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 43 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 20 | 6 | 4 |

| (25.0) | (7.1) | (7.0) | (7.1) | (9.1) | (71.4) | (20.0) | (3.2) | (6.0) | (11.8) | (9.0) | (80.0) | |||

| GHD | 45 | 0 | 2 | 35 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | (1.3) | (10.7) | (7.2) | 0 | 0 | (20.0) | (1.4) | (10.0) | (10.0) | (1.5) | 0 | |||

| GHM | 45 | 0 | 11 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 15 | 14 | 0 |

| 0 | (7.1) | (7.7) | (8.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8.5) | (2.0) | (8.8) | (20.9) | 0 | |||

| GRH IMSS No.1 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 68 | 0 | 60 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 0 | (7.8) | (0.3) | 0 | (4.5) | 0 | 0 | (21.1) | (6.0) | 0 | (7.5) | 0 | |||

| HJM | 107 | 1 | 10 | 78 | 16 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 37 | 7 | 1 |

| (12.5) | (6.5) | (23.8) | (14.4) | 0 | (28.6) | 0 | (4.2) | (20.0) | (21.8) | (10.4) | (20.0) | |||

| Total | 629 | 8 (100.0) | 154 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) | 111 (100.0) | 22 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 581 | 5 (100.0) | 284 (100.0) | 50 (100.0) | 170 (100.0) | 67 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

MSC&F: Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation; HJM: Hospital “Juárez” of México; CHG: Civil Hospital of Guadalajara "Fray Antonio Alcalde”; CMSSH: Christus Muguerza “Super Specialty” Hospital; GHM: General Hospital of Mexico "Dr. Eduardo Liceaga"; CMH: Central Military Hospital; GHD: General Hospital of Durango; GRH IMSS No.1: Regional General Hospital IMSS 1; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

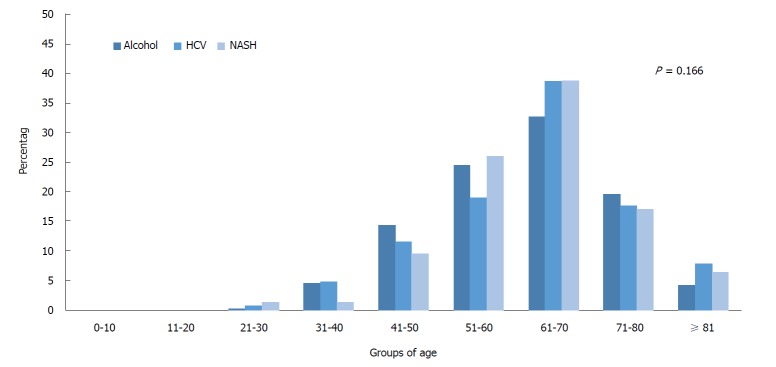

The prevalence of HCV infection, ALD, and NASH (38.6%, 32.6%, and 38.8%, respectively) was highest in the 61-70-year-old group. No significant differences in the etiology were found between age groups (P = 0.166) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main etiologies by age group were alcoholic liver disease (n = 377), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (n = 281), and hepatitis C virus (n = 438). The percentage of these etiologies was higher for patients aged 61-70 years (32.6%, 38.8%, and 38.6%, respectively). However, no significant differences in etiology were found between age groups (P = 0.166). HCV: Hepatitis C virus; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

DISCUSSION

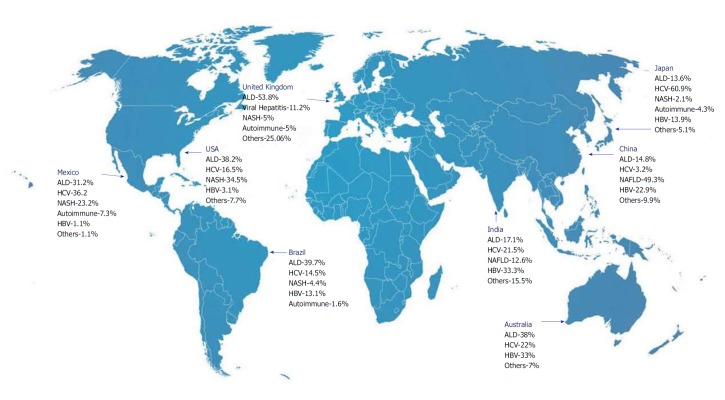

Liver cirrhosis is the fourth leading cause of death in Mexico[20]. However, cirrhosis is the second leading cause of death in people aged 35-55 years[15]. In other countries, both developed and developing, CLD is also a major health problem[21-28] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in the epidemiology of liver cirrhosis in different countries reflect differences in etiologies, such as alcohol abuse and hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. However, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its progressive form nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are becoming the most frequent etiologies of liver cirrhosis in Western countries. ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

As expected, we found that the epidemiology of cirrhosis in Mexico has changed with time. Previous epidemiological studies in Mexico have reported that ALD was the main cause of liver cirrhosis[21,29]. However, our recent results show that HCV infection and ALD are currently the most common causes of liver cirrhosis in Mexico. A recent study of 578 Mexicans with CLD by Torres-Valadez et al[30]. reported similar findings in patients assessed for liver damage. These authors reported that the leading etiologies in patients with liver cirrhosis were ALD (45%), HCV (43%), and NASH (10%). Similar to our findings, this study found that ALD was more prevalent in men, and NASH and HCV infection were more prevalent in women.

We found that NASH was the third leading cause of cirrhosis: 281 patients or 23.2%. This finding shows an increase in the prevalence of NASH of 100% compared with our report in 2004[21]. This increase in NASH prevalence corresponds to the current trends for liver cirrhosis worldwide. The recent obesity epidemic has contributed to the increase in the prevalence of NAFLD and its progressive form, NASH, which are becoming the leading causes of chronic liver disease in many countries[31]. Currently, the prevalence of NAFLD is very high in all regions, and the highest rates have been reported in South America (31%), the Middle East (32%), Asia (27%), the United States (24%), and Europe (23%). The current worldwide prevalence of NASH is 59.1%[32].

Although NAFLD has been considered a problem only in Western countries, several Asian studies have reported a growing prevalence of NAFLD in Asian countries[33,34]. The increasing prevalence of NAFLD in Asia is due to the growing trend of obesity in this country which is why it has been reported that the currently prevalence of NAFLD in Asia is around 25% to 30%[32,33,35]. Shanghai, Hong Kong and Central China are the cities with the highest prevalence rates of NAFLD; 38.17%[36], 28.8%[37] and 24.5%[38], respectively. These data are very alarming due to it is evident that obesity and its related diseases are becoming a serious problem worldwide.

In other Latin American countries such as Brazil, liver diseases are the eighth leading cause of death[39]. Cirrhosis related to alcohol consumption and to HBV and HCV infection represents 2.17% of disability-adjusted life years in Brazil[25,40]. In Brazil, the burden of liver disease is higher in young or middle-aged people[40]. By contrast, the age groups 61-70 and 51-60 years are the most affected in Mexico. This difference may reflect cultural differences because Mexicans normally do not seek medical attendance for cirrhosis until the disease has reached advanced stages. Brazilian studies have estimated that the prevalence of HCV infection in Brazilians is low (1.38%)[39,41]. However, in 2012, Gonçalves et al[27] reported that the main etiologies of liver cirrhosis were ALD (39.7%), HCV (14.5%), HBV (13.1%), and NASH (4.4%). Interestingly, ALD is currently one of the leading causes of mortality and hospital admissions in Brazil[39].

Similar to the trends in Mexico, ALD, viral hepatitis B and C, and metabolic syndrome related to overweight and obesity are the main underlying causes of liver cirrhosis in Europe and the United States. Alcohol is the strongest risk factor for chronic liver disease; alongside with NAFLD they represent 66% of liver diseases in the European population. The prevalence of NAFLD in this population is about 13%-44% which cause by itself the 13% of liver diseases and HCV with a prevalence of 0.13%-3.26% is related with 6% of liver disease. There is no percentage mentioned in European statistics about HBV (prevalence of 0.5%-0.7%) as cause of liver disease[8]. NAFLD affects around 51.7% of Americans followed by ALD (20.7%), HCV (8.6%), and HBV (3.1%)[6,42]. It is interesting to mention that United Kingdom (UK) had a high increase of liver cirrhosis in the last 2 decades compared to other European countries[43]. Nowadays, it is estimated that 30000 people live with cirrhosis and at least 70000 new cases are diagnosed each year in UK[44]. Although ALD is the first cause of cirrhosis in UK (Figure 2), a recent study has reported that NAFLD is the most common etiology for asymptomatic altered liver biochemistry, accounting for 26.4% of cases in UK[45].

Despite the expectation that NAFLD will soon become the main cause of end-stage liver disease and need for liver transplantation, we expect that the prevalence of HCV-related cirrhosis will continue to increase in Mexico because of the improved methods for diagnosing HCV infection and the difficulties in receiving care for this disease. Similarly, Davis et al[46] have estimated that the percentage of patients with HCV-related cirrhosis will reach 45% by 2030 in the United States.

In conclusion, in the present study, HCV, ALD, and NASH were the main etiologies of liver cirrhosis. Interestingly, the epidemiology of liver cirrhosis in Mexico is similar to that presented in the United States and Europe. Despite the differences between human populations they share similar cultural factors related to alcohol, hepatitis infection and obesity. CLDs will continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, it is necessary to implement preventive measures, particularly those related to viral hepatitis infection, obesity, and alcohol consumption, to decrease the rates of liver cirrhosis.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Liver cirrhosis is the fourth leading cause of death in Mexico. In our previous study, the main causes of liver cirrhosis were: alcoholic liver disease (ALD), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). However, the rising prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome has probably modified the epidemiology of cirrhosis in Mexico.

Research motivation

It is of great clinical significance to explore the methods for early diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. Moreover, it is necessary to implement preventive measures, particularly those related to viral hepatitis infection, obesity, and alcohol consumption, in order to decrease the mortality of liver cirrhosis.

Research objectives

We aimed to investigate the main etiologies of liver cirrhosis in Mexicans in the last five years.

Research methods

In this retrospective study, the clinical data of 1210 patients with liver cirrhosis were collected. The inclusion criteria were a histological, clinical, biochemical, endoscopic, or imaging diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. Data were obtained during a 5-year period (January 2012–December 2017).

Research results

The most frequent causes of liver cirrhosis were HCV (36.2%), ALD (31.2%), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (23.2%). The least frequent etiologies were hepatitis B virus (1.1%), autoimmune disorders (7.3%), and other conditions (1.0%).

Research conclusions

HCV, ALD, and NASH were the main etiologies of liver cirrhosis in Mexico. However, further studies are needed to define the epidemiology and primary prevention of liver cirrhosis in Mexico.

Research perspectives

The identification of patients with risk factors for liver cirrhosis is an important point to reduce the mortality from this disease in our country.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors cordially thank to Susel Salinas-López for her great help to data collection.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation.

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: September 6, 2018

First decision: October 11, 2018

Article in press: November 15, 2018

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aizawa Y, Arai M S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

Contributor Information

Nahum Méndez-Sánchez, Liver Research Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Mexico City 14050, Mexico. nmendez@medicasur.org.mx.

Felipe Zamarripa-Dorsey, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital “Juárez” of México, Mexico City 07760, Mexico.

Arturo Panduro, Department of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Civil Hospital of Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde”, Guadalajara 44280, Jalisco, Mexico.

Emma Purón-González, Department of Internal Medicine, “Christus Muguerza “Super Specialty” Hospital” Monterrey, Monterrey 64060, Nuevo León, Mexico.

Edgar Ulises Coronado-Alejandro, Department of Internal Medicine, “Christus Muguerza “Super Specialty” Hospital” Monterrey, Monterrey 64060, Nuevo León, Mexico.

Carlos Alejandro Cortez-Hernández, Department of Gastroenterology, “University Hospital “Jose Eleuterio González” Monterrey, Monterrey 64060, Nuevo León, Mexico.

Fátima Higuera de la Tijera, Department of Gastroenterology, “General Hospital of Mexico “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, Mexico City 06720, Mexico.

José Luis Pérez-Hernández, Department of Gastroenterology, “General Hospital of Mexico “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, Mexico City 06720, Mexico.

Eira Cerda-Reyes, Department of Gastroenterology, “Central Military Hospital”, Mexico City 11200, Mexico.

Heriberto Rodríguez-Hernández, Faculty of Medicine and Nutrition, Juárez University of the State of Durango, Durango 34100, Mexico.

Vania César Cruz-Ramón, Liver Research Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Mexico City 14050, Mexico.

Oscar Lenin Ramírez-Pérez, Liver Research Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Mexico City 14050, Mexico.

Nancy Edith Aguilar-Olivos, Liver Research Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Mexico City 14050, Mexico.

Olga Fabiola Rodríguez-Martínez, Liver Research Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Mexico City 14050, Mexico.

Samantha Cabrera-Palma, Liver Clinic, Regional General Hospital IMSS 1, Cuernavaca 62450, Morelos, Mexico.

Guillermo Cabrera-Álvarez, Liver Clinic, Regional General Hospital IMSS 1, Cuernavaca 62450, Morelos, Mexico.

References

- 1.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis -- from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, Lozano R, Mokdad AH, Stanaway J, Murray CJ, Naghavi M. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byass P. The global burden of liver disease: a challenge for methods and for public health. BMC Med. 2014;12:159. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, Volk ML. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690–696. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Setiawan VW, Stram DO, Porcel J, Lu SC, Le Marchand L, Noureddin M. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis by underlying cause in understudied ethnic groups: The multiethnic cohort. Hepatology. 2016;64:1969–1977. doi: 10.1002/hep.28677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatami B, Ashtari S, Sharifian A, Rahmani Seraji H, Khalili E, Hatami Y, Zali MR. Changing the cause of liver cirrhosis from hepatitis B virus to fatty liver in Iranian patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2017;10:S20–S26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcellin P, Kutala BK. Liver diseases: A major, neglected global public health problem requiring urgent actions and large-scale screening. Liver Int. 2018;38 Suppl 1:2–6. doi: 10.1111/liv.13682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayiner M, Koenig A, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the United States and the Rest of the World. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, Henry L, Stepanova M, Younossi Y, Racila A, Hunt S, Beckerman R. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64:1577–1586. doi: 10.1002/hep.28785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calzadilla Bertot L, Adams LA. The Natural Course of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E774. doi: 10.3390/ijms17050774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chedid MF. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: The Second Leading Indication for Liver Transplantation in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2621–2622. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4724-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cholankeril G, Wong RJ, Hu M, Perumpail RB, Yoo ER, Puri P, Younossi ZM, Harrison SA, Ahmed A. Liver Transplantation for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the US: Temporal Trends and Outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2915–2922. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rtveladze K, Marsh T, Barquera S, Sanchez Romero LM, Levy D, Melendez G, Webber L, Kilpi F, McPherson K, Brown M. Obesity prevalence in Mexico: impact on health and economic burden. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:233–239. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.López-Velázquez JA, Silva-Vidal KV, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Chávez-Tapia NC, Arrese M, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Americas. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdivia-Correa B, Chablé-Montero F, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. Epidemiology of chronic autoimmune liver disease: a histopathological study in third-level hospital in Mexico City. Rev Invest Med Sur Mex. 2016;1:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruz-Ramón V, Chinchilla-López P, Ramírez-Pérez O, Méndez-Sánchez N. Effects of Portal Vein Thrombosis on the Outcomes of Liver Cirrhosis: A Mexican Perspective. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:189–191. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2017-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Méndez-Sánchez N, Aguilar-Ramírez JR, Reyes A, Dehesa M, Juórez A, Castñeda B, Sánchez-Avila F, Poo JL, Guevara González L, Lizardi J, et al. Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Mexico. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, Srishord M. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:524–530.e1; quiz e60. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratib S, Fleming KM, Crooks CJ, Walker AJ, West J. Causes of death in people with liver cirrhosis in England compared with the general population: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1149–1158. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michitaka K, Nishiguchi S, Aoyagi Y, Hiasa Y, Tokumoto Y, Onji M; Japan Etiology of Liver Cirrhosis Study Group. Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/hep.27406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonçalves PL, Zago-Gomes Mda P, Marques CC, Mendonça AT, Gonçalves CS, Pereira FE. Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Brazil: chronic alcoholism and hepatitis viruses in liver cirrhosis diagnosed in the state of Espírito Santo. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:291–295. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(03)OA02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee PS, Vishnubhatla S, Amarapurkar DN, Das K, Sood A, Chawla YK, Eapen CE, Boddu P, Thomas V, Varshney S, et al. Etiology and mode of presentation of chronic liver diseases in India: A multi centric study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Méndez-Sánchez N, Villa AR, Chávez-Tapia NC, Ponciano-Rodriguez G, Almeda-Valdés P, González D, Uribe M. Trends in liver disease prevalence in Mexico from 2005 to 2050 through mortality data. Ann Hepatol. 2005;4:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres-Valadez R, Roman S, Jose-Abrego A, Sepulveda-Villegas M, Ojeda-Granados C, Rivera-Iñiguez I, Panduro A. Early Detection of Liver Damage in Mexican Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:49–57. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2017-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arrese M, Feldstein AE. Nash-Related Cirrhosis: An Occult Liver Disease Burden. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:84–86. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan JG, Kim SU, Wong VW. New trends on obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J Hepatol. 2017;67:862–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong VW. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia: a story of growth. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:18–23. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kojima S, Watanabe N, Numata M, Ogawa T, Matsuzaki S. Increase in the prevalence of fatty liver in Japan over the past 12 years: analysis of clinical background. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:954–961. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu X, Huang Y, Bao Z, Wang Y, Shi D, Liu F, Gao Z, Yu X. Prevalence and factors associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Shanghai work-units. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei JL, Leung JC, Loong TC, Wong GL, Yeung DK, Chan RS, Chan HL, Chim AM, Woo J, Chu WC, et al. Prevalence and Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Non-Obese Patients: A Population Study Using Proton-Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1306–14; quiz 1315. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Wang YJ, Tan K, Zeng L, Liu L, Liu FJ, Zhou TY, Chen EQ, Tang H. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in Chengdu, Southwest China. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nader LA, de Mattos AA, Bastos GA. Burden of liver disease in Brazil. Liver Int. 2014;34:844–849. doi: 10.1111/liv.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Carvalho JR, Villela-Nogueira CA, Perez RM, Portugal FB, Flor LS, Campos MR, Schramm JMA. Burden of Chronic Viral Hepatitis and Liver Cirrhosis in Brazil - the Brazilian Global Burden of Disease Study. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:893–900. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pereira LM, Martelli CM, Moreira RC, Merchan-Hamman E, Stein AT, Cardoso MR, Figueiredo GM, Montarroyos UR, Braga C, Turchi MD, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Hepatitis C virus infection in Brazil, 2005 through 2009: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singal AK, Anand BS. Recent trends in the epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;2:53–56. doi: 10.1002/cld.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratib S, West J, Fleming KM. Liver cirrhosis in England-an observational study: are we measuring its burden occurrence correctly? BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013752. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleming KM, Aithal GP, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Card TR, West J. Incidence and prevalence of cirrhosis in the United Kingdom, 1992-2001: a general population-based study. J Hepatol. 2008;49:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, Shaw JC, Cramb R, Olliff S, Gill PS, Neuberger JM, Lilford RJ, Newsome PN. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol. 2012;56:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis GL, Albright JE, Cook SF, Rosenberg DM. Projecting future complications of chronic hepatitis C in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:331–338. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]