Abstract

Optic nerve haemangioblastomas remain exceedingly rare extrinsic tumours of the optic nerve, often associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease. The authors report a 25-year-old female with a slowly progressive unilateral optic nerve lesion, causing reduced vision and bilateral optic tract oedema. A diagnosis of optic nerve haemangioblastoma with piloid gliosis was made histologically after surgical resection. This is the first reported case of such dual pathology occurring in the optic nerve. The patient has been monitored without further adjuvant treatment, and has not had a recurrence to date, at 6 years of follow-up.

Keywords: Optic nerve, Haemangioblastoma, von Hippel-Lindau, Piloid gliosis

Established Facts

Optic nerve haemangioblastoma can occur sporadically, or in association with von Hippel-Lindau disease.

This is a rare location for this tumour type, and it must be differentiated from meningioma and glioma.

Novel Insights

Optic nerve haemangioblastoma can occur with piloid gliosis of the surrounding tissue.

Peritumoural oedema can be associated with central nervous system tumours, and should be considered when bilateral symptoms and/or signs are present.

Introduction

Primary tumours of the optic nerve and its sheath are frequently benign, but cause vision loss with clinical neuropathy and variable proptosis as they progress [1]. Intrinsic tumours, such as gliomas, cause visual loss through destruction of the optic nerve fibres. In contrast, meningiomas and other extrinsic tumours produce visual decline via compression of the nerve [2]. Optic nerve haemangioblastoma is an uncommonly encountered example of an extrinsic optic nerve tumour, which can occur in the presence or absence of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease.

VHL disease is a multisystem disorder characterised by formation of haemangioblastomas, with a particular predilection for the central nervous system and retina. This autosomal dominant disease also predisposes patients to visceral neoplasms involving the kidneys, pancreas, adrenals, and epididymis [3]. Approximately half of patients with VHL only show one feature of the disease [4]. This condition is particularly relevant to ophthalmologists as retinal capillary haemangioblastomas are the most frequent and often earliest manifestation of the disease [4]. Cerebellar haemangioblastoma are commonly seen in up to 72% of VHL patients [5]. Supratentorial haemangioblastomas are rare (> 90% occur in posterior fossa), and optic nerve haemangioblastomas are exceedingly rare [6].

We report a case of an optic nerve mass with radiological and histological evidence of both haemangioblastoma and piloid gliosis. This is the first reported case of these two pathologies occurring concurrently in the optic nerve.

Case Report

A 25-year-old female with a family history of VHL disease was referred to the Oculoplastic and Oncology service from a district hospital. She was initially evaluated at the age of 21, at which time she had visual acuity of 6/6 in both eyes and right optic nerve swelling with a mild relative afferent pupillary defect. She later underwent bilateral retinal argon photocoagulation for treatment of retinal haemangioblastomas. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at that time revealed a right intraorbital optic nerve haemangioblastoma (Fig. 1a, b), with further lesions adjacent to the 4th ventricle and in the spinal cord at C2. These lesions were treated conservatively and observed with serial imaging. The patient had a 3-year period of clinical stability before developing progressive visual field loss and deteriorating acuity. An opinion was sought regarding stereotactic radiosurgery to the optic nerve haemangioblastoma, but the patient deferred intervention, accepting the vision in the right eye would continue to decline. She continued to have neurosurgical follow-up for the posterior fossa and spinal haemangioblastomas.

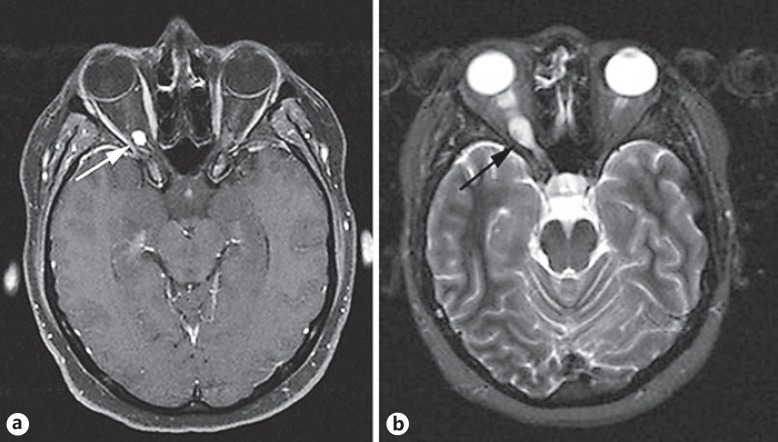

Fig. 1.

a T1-weighted axial MRI scan with gadolinium demonstrates an enhancing nodule at the distal right optic nerve, with peritumoural oedema extending toward the optic chiasm (arrow). b T2-weighted axial MRI scan showing heterogenous, hyperintense enlargement of the intraorbital portion of the right optic nerve (arrow).

The patient returned with rapid reduction in vision from 6/18 to hand movements over a 6-month period, with a right superotemporal field defect. Concerns were raised when screening MRI revealed progressive hyperintense signal change along the optic pathway involving the right prechiasmatic optic nerve, optic chiasm, and optic tracts bilaterally. This was thought to be oedema secondary to a mass effect from the right optic nerve haemangioblastoma. With an apparent threat to the vision in the left eye, a trial of oral dexamethasone was initiated by the referring team to try and reduce this oedema. However, the appearance worsened on repeat neuroimaging and the patient developed acute pancreatitis requiring a prolonged hospital admission. Our opinion was sought regarding surgical or gamma knife treatment of the optic nerve haemangioblastoma.

Although the radiological findings were suggestive of glioma, the bilateral optic tract oedema was consistent with that seen in previous reports of orbital haemangioblastoma. Therefore, we offered orbital surgery to biopsy and resecting the lesion if possible. The patient proceeded to right lateral orbitotomy and excision of the mass from the orbital portion of the optic nerve. Multiple dilated vessels were noted intraoperatively overlying the nerve. The resected tumour measured 3 × 8 mm, and biopsies were taken from adjacent dura.

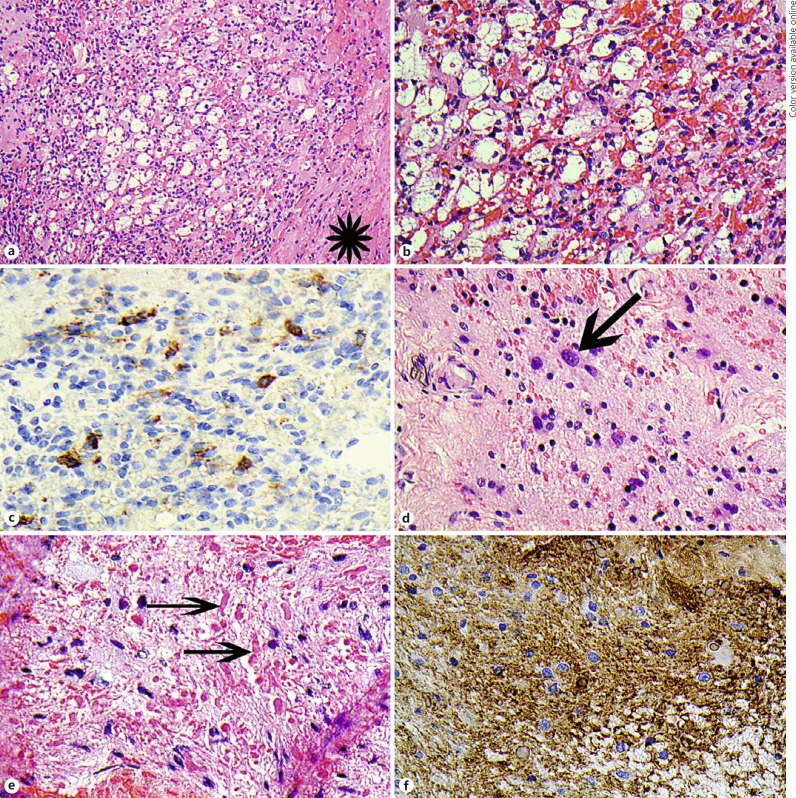

Histopathological examination revealed a vascular lesion composed of bland capillary-sized vessels between which were foamy cells with well-defined lipid-like vacuoles with bland eccentric nuclei (Fig. 2a, b). These latter cells were immunohistochemically positive for inhibin (Fig. 2c). These features confirmed the diagnosis of haemangioblastoma. Adjacent optic nerve tissue showed astroglial cells with focal nuclear atypia (Fig. 2d), associated with numerous eosinophilic Rosenthal fibres (Fig. 2e). No mitotic activity was present amongst the astroglial population. The astroglial cells were positive for GFAP (Fig. 2f) and had a low Ki67 proliferation fraction (not shown). In the context of the imaging findings and presentation, these findings were those of piloid gliosis adjacent to the haemangioblastoma.

Fig. 2.

a Haematoxylin and eosin (H and E)-stained section of the haemangioblastoma. The asterisk shows a length of dura. At this magnification, the foamy clear cells are seen in the centre and are surrounded by the vascular capillary component. b H and E showing a higher power of a. The capillaries are on the right containing erythrocytes and the foamy cells are on the left. c Immunohistochemical staining with antibodies to alpha-inhibin, showing some of the foamy cells are positive (brown = positive). d H and E showing the astroglial proliferation in the optic nerve tissue surrounding the haemangioblastoma. The arrow points to an astroglial cells with an enlarged nucleus. e H and E showing the eosinophilic Rosenthal fibres (arrows). f Immunohistochemistry staining with glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody (GFAP) shows positive staining of the piloid gliosis astrocytes (brown = positive staining).

The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course. Immediately postoperatively, she had no perception of light, and a cherry-red spot at the macula. There has been no recurrence of the tumour, nor retinopathy, at 6 years of follow-up.

Discussion

There have been 34 reported cases of optic nerve haemangioblastomas in the literature since 1930. Most of these (67%) were associated with VHL disease. As the average age of diagnosis was 37 years (median, 35 years), it is possible that some patients went on to have a diagnosis of VHL later in life, given the positive correlation between increasing age and risk of developing tumours, with full gene penetrance achieved by the age of 65 years [7]. Capillary haemangioma prevalence, however, has been shown to be stable after the age of 30 years [8]. There have been two cases with bilateral disease, both of which suffered devastating vision loss despite excision [9, 10]. Four cases were asymptomatic and diagnosed at the time of VHL screening [3, 11, 12].

As with all retrobulbar and posterior orbital pathology, imaging is recommended to help differentiate the cause. The findings in optic nerve haemangioblastoma are usually of an enhancing enlargement of a portion of the optic nerve. This pattern and shape brings to mind the major differential diagnoses of optic nerve haemangioblastoma – meningioma or glioma. Larger haemangioblastomas may have irregular-shaped flow voids adjacent to the main tumour and an absence of dural attachment, which are highly suggestive of the diagnosis [13].

The phenomenon of peritumoural oedema formation and propagation along low-resistance white matter pathways has been demonstrated in the past [13, 14, 15]. As was seen in our case, Baggenstos and colleagues [14] showed resolution of bilateral optic tract oedema after optic nerve haemangioblastoma resection, confirming the lesion as the source. Visual deficits in the contralateral eye were seen to improve after tumour removal, again suggesting that oedema was the cause of compromise, rather than ischaemia or mass effect. Peritumoural oedema can be observed in any tumour in the region of the optic nerve or chiasm, but is uncommon in optic glioma [13].

All patients with optic nerve haemangioblastoma will have vision loss without treatment. Surgery is almost universally indicated at some point in the disease. There are no reports of radiation treatment for these lesions; however, the role of conventional radiation is limited in isolated central nervous disease [2]. There have been several cases of surgical excision of these lesions resulting in stability or even improvement of vision [3, 12]. Surgical excision has an inherently high risk of complete optic nerve vascular compromise resulting in vision loss; therefore, patients who are comfortable, with acceptable proptosis, may elect to defer surgery. Surgery can, however, be useful to confirm the disease process histologically and reduce the effects of peritumoural oedema, and may aid in the diagnosis of VHL disease.

Gliosis can commonly accompany neoplastic and non-neoplastic neural disease, with a subset of astrocytic gliosis characterised by elongated, granular, hypereosinophilic, proteinaceous deposits called Rosenthal fibres [16, 17]. In this situation the term “piloid gliosis” is often used, as such features are seen in pilocytic astrocytoma. Cystic non-glial neoplasms may have associated piloid gliosis, and may mimic astrocytoma on neuroimaging [16]. Cerebellar haemangioblastomas typically have Rosenthal fibres with densely gliotic cyst walls, and may have evidence of surrounding piloid gliosis [16, 18]. This change has not, however, been reported in any past cases of optic nerve haemangioblastoma.

Haemangioblastoma of the optic nerve is rare, but should be considered in patients presenting with reduced vision, proptosis, and optic nerve pallor, with or without a personal or family history of VHL. These tumours may further be suspected by enhancement and flow voids on imaging. Surgical excision is indicated where there is rapid vision loss, pain, unacceptable proptosis, or bilateral symptoms due to peritumoural oedema. As well as this swelling, piloid gliosis can be a sign of chronicity, and should be meticulously differentiated from glioma. A multidisciplinary team approach is recommended for diagnosis, management, and follow-up of these patients.

Statement of Ethics

The patient gave full informed consent, and this report was approved by the human research ethics committee at Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield.

Disclosure Statement

No financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Miller NR. Primary tumours of the optic nerve and its sheath. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:1026–1037. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zywicke H, Palmer CA, Vaphiades MS, et al. Optic nerve hemangioblastoma: a case report. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:915408. doi: 10.1155/2012/915408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raila FA, Zimmerman J, Azordegan P, et al. Successful surgical removal of an asymptomatic optic nerve hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neuroimaging. 1997;7:48–50. doi: 10.1111/jon19977148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh AD, Shields CL, Shields JA. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46:117–142. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammerman JM, Lonser RR, Dambrosia J, et al. Long-term natural history of hemangioblastomas in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: implications for treatment. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:248–255. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotta H, Uede T, Morimoto S, et al. Optic nerve hemangioblastoma. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1989;29:948–952. doi: 10.2176/nmc.29.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher ER, Yates JR, Ferguson-Smith MA. Statistical analysis of the two stage mutation model in von Hippel-Lindau disease, and in sporadic cerebellar haemangioblastoma and renal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1990;27:311–314. doi: 10.1136/jmg.27.5.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster ER, Richards FM, MacRonald FE, et al. An analysis of phenotypic variation in the familial cancer syndrome von Hippel-Lindau disease: evidence for modifier effects. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1025–1035. doi: 10.1086/302037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginzburg BM, Montanera WJ, Tyndel FJ, et al. Diagnosis of von Hippel-Lindau disease in a patient with blindness resulting from bilateral optic nerve hemangioblastomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:403–405. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.2.1632366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fons Martinez MR, Espana Gregori E, Avino Martinez JA, et al. An optic nerve tumor in von Hippel-Lindau disease, masquerading as a retinal hemangioma (in Spanish) Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2006;81:293–296. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912006000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyerle CB, Dahr SS, Wetjen NM, et al. Clinical course of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1382–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kouri JG, Chen MY, Watson JC, et al. Resection of suprasellar tumors by using a modified transsphenoidal approach. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:1028–1035. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turel MK, Kucharczyk W, Gentili F. Optic nerve hemangioblastomas – a review of visual outcomes. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;27:827–831. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.16680-15.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggenstos M, Chew E, Butman JA, et al. Progressive peritumoral edema defining the optic fibers and resulting in reversible visual loss. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:313–317. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/8/0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanebo JE, Lonser RR, Glenn GM, et al. The natural history of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:82–94. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera-Zengotita M, Yachnis AT. Gliosis versus glioma?: don't grade until you know. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19:239–249. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31825c6a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grattarola FR. Piloid gliosis; a histological study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1958;17:644–648. doi: 10.1097/00005072-195810000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konig A, Laas R, Muller D. Three cases of intramedullary spinal hemangioblastoma: the role of intraoperative histological diagnosis. Neurosurg Rev. 1987;10:153–155. doi: 10.1007/BF01741455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]