Abstract

Digital storytelling (DST) is an emerging participatory visual method which combines storytelling traditions with computer and video production technology. In this project, at the heart of the HIV epidemic in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, we used DST to create a culturally grounded community engagement intervention. Our aim was to use narratives of people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART) to stimulate dialogue among the wider community and to encourage reflection on the contextual factors that influence ART adherence in this setting. We also wanted to explore whether exposure to the personal narratives might influence health literacy around HIV and ART. We ran two DST workshops, where 20 community participants were supported to create short digital stories about personal experiences of adherence. We then hosted 151 screenings of the digital stories at seven local health facilities and evaluated the impact of the intervention using a three-tiered mixed methods approach. We conducted two independent quantitative surveys of healthcare users (852 respondents during the preintervention round and 860 people during the postintervention round), five focus group discussions and observation of practice. Exposure to the digital stories did stimulate rich dialogue among community members, which broadened from the focus on ART adherence to other aspects around the impact of HIV and its treatment on individuals and the community. In the independently conducted surveys, we found no clear difference in knowledge or understanding of HIV and ART between the people exposed to the digital stories and those who were not exposed. Our findings provide support for the use of DST as an engagement intervention, but highlight some of the challenges in delivering this type of intervention and in evaluating the impact of this approach.

Keywords: health care education, film, Hiv/aids, aarrative medicine, patient narratives

Background

Community engagement has become a focus of attention in public health research. Collaborative partnerships between researchers and researched communities are increasingly perceived as essential ingredients in effective health interventions and are reported to foster community ownership and understanding of research findings and to cultivate culturally relevant solutions to the health challenges concerned.1 2 Yet, while community engagement has acquired greater recognition as a vital aspect of health research and many funding agencies now encourage scholars to seek ways to engage communities in their studies,3 there remains little clarity about how the ‘effectiveness of community engagement should be conceptualised and measured’.1 Consequently, there is a great need for further research that reflects on the evaluation of community engagement, research that is grounded in praxis and can help to guide scholars and public health practitioners in their work.

As researchers become more involved in community engagement and the non-biomedical aspects of human health, studies become increasingly cross-cultural and transdisciplinary in nature.4 For example, in recent years, researchers have shown a great interest in human stories and are using storytelling to collect data and to develop culturally grounded community engagement interventions.5 In contrast to traditional didactic approaches where reasons are used to support a particular course of action, with narratives, stories are used to depict events and consequences for characters and can influence knowledge and behaviour indirectly through changes in feelings, attitudes, norms, self-efficacy and intentions.6 7 Moreover, such story telling contributes to what sociologist Ann Oakley in her work with children (1994), refers to as studying the world from the perspective of the participants.8

Digital storytelling

This narrative tool is an emerging participatory visual method (PVM), which combines storytelling traditions with computer and video production technology. PVM comprises a variety of arts-based, visual methods, such as collage, photovoice, digital storytelling (DST) and participatory video. This approach can help health researchers to be more inclusive by involving individuals from marginalised communities since it is known to help subvert the power dynamics in community based research between researchers, who are typically well-educated and comparatively privileged, and participants who tend to be less-educated and much less wealthy.8 PVM can also help to make the health topic at hand more accessible by offering participants an opportunity to articulate information that may otherwise have been difficult to communicate verbally due to illiteracy, language obstacles or topic sensitivity, such as HIV drug adherence.8 9 Thus, by involving individuals from marginalised communities in health research, PVM can help promote inclusivity and understanding from the perspectives of those most impacted by the issues.

A digital story is a short video narrative created in a structured workshop where participants learn creative and technical skills to tell an important life story.10 Based on Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s theoretical framework of empowerment, DST is known to increase community members’ participation in research on local issues.11 Digital stories are also known to help people to make sense of their worlds and are said to encourage creative self-expression and to promote a sense of independence, agency and ownership.12 Consequently, DST is fast becoming popular and is used in education, health research, community engagement, violence prevention and social advocacy.11 13 14

Our interest in DST was stimulated by thinking of ways to engage people living with HIV and communities in discussion about adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in rural South Africa. The project arose from our experience with our clinical research in the same area focused on HIV drug resistance.15 16 During that research, clinicians assessing patients with ART failure were alerted to the complex challenges people face in maintaining adherence to ART. They were also conscious of the difficulty in fully exploring these challenges within the framework of the doctor-patient relationship. Although there is a large body of research around ART adherence, and specifically about the development of interventions to promote adherence, much of this focuses on a biomedical model.17–20 i However, ethnographic work around ART adherence highlights the much more complex social and behavioural influences on adherence.19 We therefore developed this project to get deeper insight into the challenges to adherence through this narrative-based approach, while also exploring whether this could also be used to engage the community more broadly in thinking about the importance of ART adherence and the community-level factors that might influence adherence (eg, stigma, discrimination, gender power dynamics).

The core objectives of the project were to:

Support people to share their experiences of ART through a series of DST workshops.

Create a DVD anthology of digital stories along with a short introduction.

Engage the public using the film to provide information and stimulate dialogue about what is involved in taking ART, the challenges that people face and the role of the community in supporting people living with HIV.

We have previously presented our thematic analysis of the digital stories.20 i In this paper, we now focus on the third objective—we discuss the use of DST as a community engagement tool and reflect on the methodological, practical and ethical challenges of using the stories as a way of engaging the wider community.

Project details

Our project was based at an international health research institute, which operates in the rural uMkhanyakude district of the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. This is a resource-poor community with a total unemployment rate of around 53% estimated by the National Census of 2011. The HIV prevalence rate is also high, being 29% in the population aged 15–49 years in 2011.21 Since 2004, HIV treatment and care have been provided through a decentralised primary healthcare (PHC) programme.22 By 2010, 40% of the population resided in a home in which at least one member was in HIV care and 25% in a household with at least one member on ART.23 The scaleup of ART has had a major impact on population level mortality and there has been a remarkable increase in adult life expectancy of 11 years between 2003 and 2011.24

Overall design

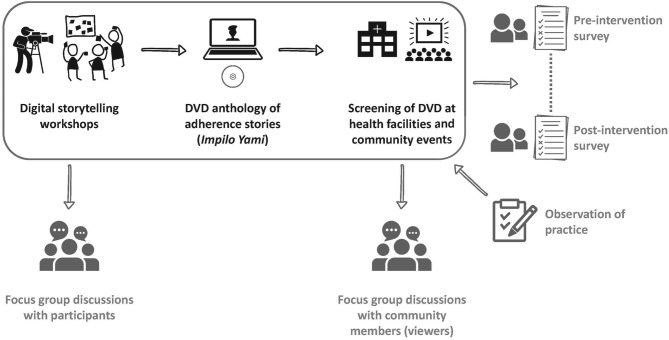

We selected 20 people to attend a 5-day DST workshop, during which they would create their own digital story. We then collated the stories into a DVD, which was shown to community members at healthcare facilities and other community settings. We evaluated the use of the digital stories for community engagement through a mixed methods approach: quantitative surveys of community members’ knowledge and understanding of HIV and ART, focus group discussions (FGDS) with people who viewed the DVD and observation of practice during the DVD screenings (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Digital image of project design.

Creating and sharing digital stories

Participant recruitment for DST workshops: We recruited participants for the DST workshops at seven of the local PHC clinics during the first 2 weeks of October 2013. These clinics were the ones most closely associated to the research Centre at this time. The community responded well to the project and we received a total of 96 applicants. Of these individuals, we selected 10 to attend each of two workshops. The project team conducted the selection independently. Although all eight men who applied were invited to attend, only one participated in the project. The participants consisted of 19 women and one man, between the ages of 20 and 53 years, with a mean age of 30 years.

Workshop details: We held two 5-day DST workshops in November 2013. In total, 10 people attended each workshop and 20 short films of 2–3 min in length were produced. A team of seven women produced the workshops, comprising the first author (project principal investigator), a story facilitator), a trained HIV counsellor, a health educator and three local research assistants. On the first workshop day, we introduced the participants to the project process and expected outcomes, including the creation of a DVD, which we aimed to use to boost community engagement with ART adherence in the clinics settings. We read through the consent form in isiZulu, the participants’ home language, and asked them to confirm their participation. We then invited consenting participants to join the story circle, where they each shared an important story from their lives prompted by the ‘Adherence Stories’ theme of the workshop. We offered a short photographic and art tutorial which was designed to build the participants’ ability and confidence to use their own photographs and stories in their storytelling and to use anonymising visual techniques such as silhouettes or extreme close-ups. In line with ethical practices in DST, however, we did not attempt to place any further control on the story content, since it is considered ethically important to conduct the process in such a way that individuals are respected as authorities on the content of their own lives.25

Sharing digital stories: Twenty anonymised digital stories were produced and with storyteller consent these were compiled into a DVD anthology called Impilo Yami (which translates from isiZulu as ‘My life’ or ‘My health’. The anthology has English subtitles and a short introduction. To avoid unintended disclosure, these stories were kept anonymous, with storytellers using visual techniques, such as drawing and symbolic photography, to mask identities. A hundred copies of the anthology were distributed to community and project stakeholders, storytellers and to nurses working in the seven local public health clinics. Each of these facilities has, on average, 4000 patient visits per month. Between December 2013 and July 2014, we hosted 151 interactive screenings with scientists, community stakeholders, storytellers and at clinics. At clinics, we made use of audiovisual equipment that had been donated through the PEPFAR-funded ART programme. The aim was for patients to watch informative audiovisual media during the many hours of waiting to see a healthcare practitioner. Although this equipment was just a few years old, technical maintenance was required at all of the facilities before the film could be played, and in one clinic, the television was stolen and we had to replace it before our screenings could commence.

Measuring impact

We ran a three-tiered impact evaluation using mixed methods to gain insight into the effectiveness of our intervention. Each tier had specific aims, which we describe below together with our specific procedures.

Tier one

Quantitative survey: We ran a two-round quantitative evaluation at the seven local clinics. The survey instrument consisted of 15 closed-ended questions designed to assess knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of ART. It is important to note that we did not attempt to measure impact on the individual. This would require us to interview each person before and after watching the DVD and would be too time consuming and impractical because Impilo Yami is over 40 min in length and the questionnaire itself takes about 10 min to administer. Therefore, we focused on comparing knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of ART adherence between community members who had seen the digital stories and those who had not.

The baseline survey was conducted at seven participating clinics, before the anthology was made, by three female staff (852 respondents) over 4 weeks. Respondent age ranged from 13 to 90 with a mean age of 34.5 years and 157 (18%) of respondents were male. After public screenings of the Impilo Yami anthology at the same seven clinics, we ran a second-round survey administered by one male and two female staff members hosted four screenings per day in each of the seven clinics. All three staff members were from the local community and one had formal training and experience as an HIV counsellor. At the HIV clinics, where there are no televisions, we screened the DVD on laptops to small groups. Over the 12 weeks of the evaluation period, we hosted 144 screenings altogether (12 per week over 12 weeks). At the end of each screening, the fieldworkers approached viewers and asked them to take part in a survey. With permission granted, they administered the same set of 15 questions that was used in the baseline survey. In this second round, there were 860 respondents, with ages from 13 to 80 with a mean age of 33 years; 120 (14%) were male.

Tier two

We ran five FGDs in September and October 2014. Altogether 65 individuals attended these events. Three FGDs were held with the general public, one with local healthcare workers and one with the Centre’s Community Advisory Board (CAB). ii Recruitment took place during the month of August 2014. Two research staff returned to the same seven clinics from the evaluation and played Impilo Yami. After it had been shown, they invited viewers and healthcare workers to put their name down to attend a FGD about the film the following month. Altogether, 102 members of the general public and 37 healthcare workers were interested in participating. Of these individuals, 47 were randomly selected to attend. In the end, approximately 8 individuals were present at each of the public FGDs (24 altogether) and 11 at the healthcare worker discussion. For the final FGD with the CAB, we had approximately 30 CAB representatives. We started each FGD by playing Impilo Yami and then guided an interactive discussion using the following five broad questions and then probed further where necessary:

FGD questions:

What do you think about the film Impilo Yami?

Can you relate to these stories?

What do you think of the music that was used?

What do you think about the pictures that were used?

Did the stories influence you in anyway?

Tier three

Observation of practice: During the month of August, while FGD recruitment was taking place, the research assistants conducted participant observation at the seven local clinics over 7 days. This simply consisted of checking whether the film was on when they arrived in the clinic, how many people were in attendance, whether the audio-visual equipment was working and whether or not people paid attention to the film while it was on. These insights were recorded to gain an understanding of the feasibility of the intervention design.

Data analysis

We used Stata software to organise and analyse the quantitative survey data. To gauge insight into the impact of the product on people’s knowledge, we compared answers between those who had been exposed to the product and those with no exposure. For the qualitative FGD data, we used the NVivo software programme to organise and systematically code the FGD transcripts. Inductively, we composed a list of categories derived from the participants’ statements during interviews. The questions were also used to guide the coding of the data and to structure our discussion.

What we found

Observation of practice results

The observation that we conducted revealed that clinic staff seldom played the Impilo Yami DVD and when they did, people at the clinics did not always pay attention to it. The research assistants thought that the lack of attention may have been due to the high noise levels in clinics since people were not able to hear the stories. When the clinic was quieter and the DVD was played, patients tended to pay greater attention to the content. These screenings effectively sparked informal discussions among viewers about HIV and ART.

Survey demographics

We conducted the prescreening survey with 852 people (82% female, mean age 34 years) and the postscreening survey with 860 people (86% female, mean age 33 years). In the postscreening survey, 821 participants (96%) reported having viewed the digital stories.

Survey results

Overall, there were relatively high levels of literacy around ART, with most of the participants in both surveys reporting awareness that ART prolongs a person’s life (95% in prescreening survey vs 95% in postscreening survey), that ART does not cure HIV (86% vs 84%) and that treatment should be continued even after returning to health (89% vs 93%). With more specific questions about the benefits of ART, there were some differences between the two surveys, although the direction and extent of the difference was not consistent. A greater proportion of respondents in the postscreening survey reported that ART gives one ‘hope to live again’ (50% vs 72%) whereas a similar proportion felt that ART helps one to regain health (53% vs 51%). A minority in both surveys thought that ART allows one to return to work, but there was some evidence of increased awareness in the postscreening survey (11% vs 28%). Conversely, in the postscreening group, fewer people thought that one could raise a family while on ART (88% vs 71%).

Most participants reported that they had learnt about ART from a PHC clinic (72% vs 76%). There was an increase in the proportion that reported learning from television (7% vs 27%), but only 4% in the postscreening survey reported learning about ART from a movie called Impilo Yami screened at the clinic.

Focus group discussion findings

In addition to sparking health dialogue in the clinic setting, the intervention succeeded in stimulating audience discussions about a wide variety of health topics among participants at the FGDs. These included HIV infection, safe sex, the relationship between HIV and other chronic illnesses, adherence and alcohol, adherence and poverty, adherence and gender power dynamics and the complex interactions between HIV disclosure, stigma and adherence. These rich health dialogues provided important insight into local experiences of significant health problems and could inform the development of culturally grounded health interventions. Our inductive analysis of the transcribed dialogues resulted in six overlapping themes, which were loosely organised around our five guiding questions. These themes include: (1) Questions of authority and ownership; (2) Narrative relevance; (3) Stirring emotions; (4) Faceless storytelling; (5) Influencing ideas and behaviour and (6)Medical plurality.

Questions of authority and ownership

Sixteen participants indicated that they thought the stories were not didactic enough on their own and they should also feature local healthcare workers to make them more informative and authoritative. For example, one female healthcare worker stated that ‘there should be some sort of solution to the problem and how it can be prevented in future, to have a lesson that is available and how it can be avoided in the future’. While a number of people spoke about the great potential of the stories to share information with the community, five others, in particular healthcare workers, were concerned that issues may be left unresolved and that there were no concrete solutions offered to guide behaviour. For example, a female CAB member commented that

It must be clarified to the community that that it is not only sex that you get HIV from, to help your relative perhaps who is sick, you have nothing on your hands, you can contract it.

Further, with regard to authority and content control, four participants found that there was too much repetition in the story content. They suggested that in future projects, we guide story creation to ensure a greater variety of topics are covered.

With regard to ownership, a number of respondents asked for copies of the DVD to take home and share with their families. However, since HIV is a taboo topic in most of this community and stigma may be a risk for storytellers, our ethics board advised to limit story sharing to the clinics, the research centre and CAB representatives only. Yet, many participants were disappointed that there was no DVD for them to take home:

The film is beautiful. But, can one get the film to take to our homes and show to others? Like me, all my family is on HIV treatment. Everyone at home takes pills. Here you see that it is only me who is present. It would have been better if I could take this video, so they can watch it at home because now I’m the only one who is informed.

Moreover, many of the CAB representatives said that they were planning to share the film at their meetings with traditional leaders and the youth. However, three members alluded to the challenge of electricity, which is often lacking in rural community halls and also the lack of audiovisual equipment, which they do not have themselves. This points to the challenges of sustainability and the logistics of using this audiovisual medium to support community engagement in this setting.

Narrative relevance

We received four comments about the stories being outdated. Participants cited many examples of ‘depressing stories’, which highlight the pain of illness and loss of life before the large-scale ART rollout, which occurred around 2007 in this community. Nevertheless, others argued that the subject matter was still relevant: ‘The stories are old news. However, there are still people who stigmatise others. There are people who hide their pills. And there are people who don’t want to test …’

In our analysis of the FGD transcripts, we found 25 references to participants describing how they related to the stories on a personal, community or family level. For example, the female participant below spoke about how she related to these stories as an HIV-positive person on treatment:

This story concerns me since I told my children in 2006 that I am infected and they encouraged me to go to the clinic. I went to the clinic. I learned about ARV’s. My children encouraged me to go and start at clinic. They taught me how to take treatment. I decided to take them at 8pm. I would set it with Generations [a local soap opera]. My children support me and when Generations starts, they remind me ‘mother have you taken pills?’ If they get infected they must not be afraid to tell me as well.

The above example was of particular interest to us since it provided one of the many culturally relevant solutions to adherence that participants shared with each other in the FGDs. Below, we cite an example of an FGD excerpt where a participant spoke about how he related to the stories on a family level:

These stories are relevant to me because my father was killed by this. My father was a traditional healer. He used traditional medicine. He usually said it will heal him but eventually it did not heal him. He died and he never went to the clinic to check what was ailing him.

Stirring emotions

When we asked the participants about their impressions of the music, 12 shared positive impressions of the music and argued that the songs boosted the emotional impact and cultural relevance of the stories. For example, one participant commented on the song, Safa saphela, which is a (historical) song from the Resistance Movement, which can serve to remind listeners of the struggle for freedom under Apartheid:

With this music, I am thinking that it will be a warning to black people to continue to unite and try to find ways to solve this issue of this virus. It is very important for people to check all the time, month by month. It is the way it should be done. Each and every person must go to check.

Nevertheless, four other participants found the songs stirred up discomforting emotions and were melancholic. For instance, one male participant said that:

The people in the film are a bit sad, do you see? So, it does not give hope, you see? Even the songs that are sung, they don’t give hope. Like the one that says ‘Safa saphela isizwe esimnyama’ … (The black nation is dying). So, to a person who is listening to it, it means there is no life or help after you receive pills.

This discussion about sadness and emotional discomfort surfaced in other discussions. For example, another participant explained, ‘They sing nicely, but the music has sorrow inside and you remember those things, like funerals, or when a person was sick’. Three participants argued that the stories were too sad and did not give hope, while two others suggested that screenings be facilitated by a trained counsellor, who could dispel misinformation and provide emotional support if the stories triggered deep emotions.

Faceless storytelling

Figures 2 and 3 present drawings made by participants to illustrate their stories.

Figure 2.

Participant felt tip pen artwork of her late mother.

Figure 3.

Participant mixed media artwork of family supporting an HIV-positive child.

Fourteen people responded favourably to the anonymous participant drawings and to the familiar photographs taken around their community. For example, one female participant noted: ‘I like the way the photographs are used. It makes you relax. You see that even if we are photographed, we know that our faces won’t be exposed’. Yet, four other participants were unimpressed with the visual imagery. One noted that adults could never take these child-like drawings or photographs seriously. Another male healthcare worker argued that the anonymity made the stories less believable: ‘The confidentiality thing they will spin it around and say that they are hiding people because this is all false and the whole film will be dismissed’.

Influencing ideas and behaviour

We received 138 comments on ways in which the film could influence ideas or behaviour in various ways. For example, while 30 spoke about how the film could stimulate the community to support those on treatment, 26 others commented on how the film could encourage disclosure within the context of friendships, romantic relationships or families. For example, a female respondent noted that:

This film has a huge impact on me because you know, sometimes I was scared to talk about this to people and explain that I am like this. But, right now, I have seen the film and I won’t be having a problem with speaking to people and telling them about my status and about taking pills.

Others spoke about disclosure in the context of the family. For example, a female participant noted that:

This film helps many people since most people are infected. They stigmatize themselves by taking pills in private. People in my family, elders and youngsters, when they take pills, they hide. They say they are for arthritis.

Eighteen participants spoke about the potential impact that the film may have on adherence knowledge and behaviour. For example, one participant noted:

This film encourages all people who find themselves infected to not relax but to continue to take pills. Also, the one who is not infected it encourages him or her very much to go and check to know their status… So, he or she can know about how is their life so they can be able to take pills as instructed.

Thirty-one participants discussed how the stories might raise awareness of the importance of going to the clinic when one is ill and of testing for HIV and other illnesses. For example, a female contributor noted that the film:

Encourages all people who find themselves infected to not relax, but to continue to take pills. Also, the one who is not infected it also encourages him or her very much to go and check so they will know how is their status. It not only AIDS because TB was also mentioned which may happen that another person is sick because of it. It encourages him or her to also go and check that they don’t have TB.

Moreover, 18 individuals spoke about how exposure to the film would discourage stigma and boost social support ‘It helps even at home when people are taking ARVs let’s not stigmatized them. Let’s support them so they can take their treatment well, so they can recover.’ and 15 spoke about how the film could give hope since it showed that ARVs work. For example, a female contributor noted that in the past she thought that she would commit suicide if she discovered that she was positive. ‘However, seeing this film, now I see that it is not the end of life. If I discovered that I have HIV, I can take ARVs and my life will continue be longer’.

Medical plurality

Exposure to the stories stimulated over 20 discussions about the relationship between traditional and Western medicines. Many of these conversations were critical of traditional medicine. For example, one female participant explained that if she finds that she is sick with HIV, she will tell her parents and she will take her treatment and not ‘go to the traditional doctors because they won’t help me’. There were a number of traditional healers in the attendance at the FGDS and some expressed concerned that this film might encourage viewers to critique traditional healers and could interfere with the efforts of individuals and organisations, such as Amref Health Africa, who endeavour to forge cooperative relationships between healers and local health authorities.

Discussion

Our goal in this study was to use narratives of people living with HIV on ART to stimulate dialogue among the wider community and to encourage reflection on the contextual factors that influence ART adherence in this setting. We also wanted to explore whether exposure to the personal narratives might influence health literacy around HIV and ART.

We applied mixed methods to measure the effectiveness of the intervention using a three-tiered approach. The results of the quantitative survey showed slight changes with regard to the benefits of ART, although the direction and extent of the difference was not consistent. We decided to use a survey methodology because we wanted a robust method of evaluating the impact and yet it was logistically challenging to conduct the survey in busy PHC clinics. Although we collected some general information about the nature of people’s engagement with the DVD during the observation of practice, we did not link this information to individual survey participants, that is, to know what the level of their engagement was with the DVD. It would have been useful to have a clearer sense of this to help interpret the survey findings. In retrospect, the preintervention and postintervention survey may not have been the most appropriate evaluation method, since the survey was created at the beginning of the project, when we were seeking ethics approval, and before the stories had been created. Therefore, the questionnaire and stories do not always agree and some of the questions were redundant. On reflection, we allowed ourselves to be too constrained by the ethics approval process. The committee required the final survey questionnaires prior to approval (which was appropriate given the sensitive topic) and, as a result, we decided to make the questions quite general. Perhaps, we could have submitted amendments to the questionnaire to the ethics committee after the production of the stories. It might have made more sense to have run the survey in three clinics that had the stories playing and then used a control arm where people were not exposed to the DVD.

These practical lessons are valuable and can help us and others to design more effective quantitative evaluation surveys in future projects. And yet, it would seem that the standard survey evaluation framework with relatively simple markers of knowledge and beliefs may be too simplistic an approach to capture the true impact of these creative methods and we need to think differently about how to measure the value of this research. Our findings are similar to those from another participatory methods project with adolescents in Tanzania, where a drama-based intervention effectively engaged community members in discussions about HIV, but formal survey evaluation revealed no change in the community members’ information or knowledge.26 Based on the richness of the qualitative findings referred to above, we advocate for more nuanced and reflective tools to help capture the effects of creative engagement products on viewers. Indeed, Gubrium and colleagues (2016) have spoken about similar experiences when attempting to measure the effectiveness of the DST process in a health promotion project.27 They suggest that there is a need to develop culturally relevant evaluation tools that prioritise process effects and are sensitive to the local context.27

In contrast to the quantitative findings, the FGD and the observation of practice results were much more informative. First, these results both suggest that the busy and noisy clinic environment may not be the best place for this intervention. A quieter space, supported by a trained facilitator would be ideal. Certainly, the healthcare workers’ concerns of retraumatisation risks and misinformation are important and we believe that it would be best if screenings were facilitated so that questions can be answered and people could be referred to a counsellor if need be. Second, both of the methods show that the digital stories could spark community health dialogue about a variety of topics, including generally taboo subjects such as HIV and sex. It was truly incredible just how much dialogue the stories inspired. People spoke about a wide range of health topics and took this opportunity to share deeply personal experiences of HIV and ART adherence. Indeed, they used this opportunity to share their own stories with each other and to jointly make sense of their worlds.

We view the participants’ profound and enthusiastic engagement in the health dialogue following the screening as a very important finding. Certainly, this response suggests that opportunities for reflection on these important health topics are rare and that the ‘safe space’ that we provided in these FGDs, through the relatively small groups and the support of the counsellor and research staff, was of value to those involved. Since our participants were mostly indigenous women from a rural, patriarchal community, the opportunities for them to share their health experiences are indeed rare. Therefore, this is an example of how DST can be used to advance social justice by bringing non-dominant and dissident voices to the fore and supporting listening. The information that was shared is most valuable and can be used to inform culturally grounded solutions to the related health problems. Consequently, our results suggest that this model of screening digital stories, followed by facilitated discussion, shows greater promise as a narrative intervention than unfacilitated screenings for masses of people.

People’s willingness to participate in these discussions also points to the strength of using culturally grounded narrative approaches in community engagement.28 29 Certainly, our results suggest that storytelling is a valuable tool that can be harnessed in community engagement to help people to share experiences, to listen to each other and to make sense of their worlds.30 In terms of using DST specifically to explore ART adherence, our experience can be related to the ‘My story’ project in Zimbabwe, where it was successfully used with adolescents on ART. In that study, the sharing of stories showed promise as an adolescent-led advocacy and training tool.31

Houston and colleagues have developed a narrative engagement framework to plan narrative engagement and evaluate narrative effects in health research.32 This framework could be a very helpful way to design and map the effects of future DST interventions. Yet, for us to truly assess the impact of the digital stories on health literacy and behaviour, we would need to have a longer period of engagement with FGD participants. Indeed, a limitation of this project is the fact that we only engaged with the FGD participants on one occasion. This limited contact did not allow enough time for reflection or for us to ask whether they had acted or felt differently after seeing the stories.

Conclusion

In this study, we have shown that digital stories created by people living with HIV can be used as an innovative culturally grounded tool to open up dialogue about HIV and ART in the community. Although there was no evidence that witnessing the stories changed people’s knowledge and literacy around HIV, the lack of effect may have been due to insufficient exposure to the stories due to difficulties around screening the video in busy clinics or to the disparity between the content of the stories and the survey questionnaire. Qualitative evaluation revealed that the digital stories were an effective way to engage people and stimulate dialogue around many aspects of HIV and its treatment. While much of the dialogue diverged from a strict definition of adherence, the discussions highlighted the much broader contextual and psychosocial factors that influence adherence to ART.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories with us and we also acknowledge Farirai Mutenherwa and Alain Vandormael for their assistance with narrative coding and statistical analysis, respectively.

Footnotes

Name of authors removed for blind review.

The CAB functions across the breadth of the institute’s research. It is constituted by election of representatives from the local community.

Contributors: Conception or design of the work: AJT-G, TdO, RM. Data collection: AT-G. Data analysis and interpretation: AT-G, RM, RJL. Drafting the article: AJT-G, RM, RJL, TdO, BG. Critical revision of the article: AJT-G, RM, RJL. Final approval of the version to be published: AJT-G, RM, TdO, BG, RJL.

Funding: The project is funded through a Wellcome Trust International Engagement Award (Award number WT099669MA).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) in 2013 (2013–2015) (BE203/13). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Tindana PO, Singh JA, Tracy CS, et al. . Grand challenges in global health: community engagement in research in developing countries. PLoS Med 2007;4:e273–55. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haines A, Kuruvilla S, Borchert M. Bridging the implementation gap between knowledge and action for health. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:724–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kolopack PA, Parsons JA, Lavery JV. What makes community engagement effective?: Lessons from the Eliminate Dengue Program in Queensland Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0003713 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nyika A, Chilengi R, Ishengoma D, et al. . Engaging diverse communities participating in clinical trials: case examples from across Africa. Malar J 2010;9:86 10.1186/1475-2875-9-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller-Day M, Hecht ML. Narrative means to preventative ends: a narrative engagement framework for designing prevention interventions. Health Commun 2013;28:657–70. 10.1080/10410236.2012.762861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freimuth VS, Quinn SC. The contributions of health communication to eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health 2004;94:2053–5. 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, et al. . Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med 2007;33:221–35. 10.1007/BF02879904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mitchell CM, Sommer M. Participatory visual methodologies in global public health. Glob Public Health 2016;11(5-6):521–7. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1170184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gubrium AC, Fiddian-Green A, Jernigan K, et al. . Bodies as evidence: mapping new terrain for teen pregnancy and parenting. Glob Public Health 2016;11(5-6):618–35. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1143522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oakley A. Women and children first and last. Parallels and differences between children’s and women’s studies Mayall B, ed Children’s childhoods observed and experienced, 1994:13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lambert J. Digital storytelling: capturing lives creating community. 3rd edn Berkeley, California: Digital Diner Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burgess J. Hearing ordinary voices: cultural studies, vernacular creativity and digital storytelling. Continuum 2006;20:201–14. 10.1080/10304310600641737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gubrium A. Digital storytelling: an emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promot Pract 2009;10:186–91. 10.1177/1524839909332600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manasa J, Lessells RJ, Skingsley A, et al. . High-levels of acquired drug resistance in adult patients failing first-line antiretroviral therapy in a rural HIV treatment programme in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One 2013;8:e72152 10.1371/journal.pone.0072152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lessells RJ, Stott KE, Manasa J, et al. . Implementing antiretroviral resistance testing in a primary health care HIV treatment programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: early experiences, achievements and challenges. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:116 10.1186/1472-6963-14-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Munro S, Lewin S, Swart T, et al. . A review of health behaviour theories: how useful are these for developing interventions to promote long-term medication adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS? BMC Public Health 2007;7:104 10.1186/1471-2458-7-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bärnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, et al. . Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:942–51. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, et al. . Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000011 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Treffry-Goatley A, Lessells R, Sykes P, et al. . Understanding Specific Contexts of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Rural South Africa: A Thematic Analysis of Digital Stories from a Community with High HIV Prevalence. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148801 10.1371/journal.pone.0148801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaidi J, Grapsa J, Tanser F, et al. . Dramatic increased in HIV prevalence after scale-up of antiretroviral treatment: a longitudinal population-based HIV surveillance study in rural KwaZulu-Natal. AIDS 2013;27:2301–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houlihan CF, Bland RM, Mutevedzi PC, et al. . Cohort profile: Hlabisa HIV treatment and care programme. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:318–26. 10.1093/ije/dyp402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bor J, Bärnighausen T, Newell C, et al. . Social exposure to an antiretroviral treatment programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:988–94. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02795.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, et al. . Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science 2013;339:961–5. 10.1126/science.1230413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gubrium AC, Hill AL, Flicker S. A situated practice of ethics for participatory visual and digital methods in public health research and practice: a focus on digital storytelling. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1606–14. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kamo N, Carlson M, Brennan RT, et al. . Young citizens as health agents: use of drama in promoting community efficacy for HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health 2008;98:201–4. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gubrium AC, Fiddian-Green A, Lowe S, et al. . Measuring down: evaluating digital storytelling as a process for narrative health promotion. Qual Health Res 2016;26:1787–801. 10.1177/1049732316649353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hecht ML, Krieger JLR. The principle of cultural grounding in school-based substance abuse prevention. J Lang Soc Psychol 2006;25:301–19. 10.1177/0261927X06289476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larkey LK, Hecht M. A model of effects of narrative as culture-centric health promotion. J Health Commun 2010;15:114–35. 10.1080/10810730903528017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scheub H. The uncoiling python: South African storytellers and resistance. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Willis N, Frewin L, Miller A, et al. . “My story”—HIV positive adolescents tell their story through film. Child Youth Serv Rev 2014;45:129–36. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Houston TK, Cherrington A, Coley HL, et al. . The art and science of patient storytelling-harnessing narrative communication for behavioral interventions: the ACCE project. J Health Commun 2011;16:657–70. 10.1080/10810730.2011.551997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]