Abstract

Background and purpose

Intrasaccular aneurysm flow disruption represents an emerging endovascular approach to treat intracranial aneurysms. The purpose of this study was to determine the clinical and angiographic outcomes of using the LUNA aneurysm embolization system (AES) for treatment of intracranial aneurysms.

Materials and methods

The LUNA AES Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up study is a prospective, multicenter, single-arm study that was designed to evaluate device safety and efficacy. Bifurcation and sidewall aneurysms were included. Aneurysm occlusion was assessed using the Raymond-Roy classification scale. Disability was assessed using the Modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Morbidity was defined as mRS >2 if baseline mRS ≤2, increase in mRS of 1 or more if baseline mRS >2, or mRS >2 if aneurysm was ruptured at baseline. Clinical and angiographic follow-up was conducted at 6, 12 and 36 months.

Results

Sixty-three subjects with 64 aneurysms were enrolled. Most aneurysms were unruptured (60/63 (95.2%)); 49 were bifurcation or terminal (49/64 (76.6%)). Mean aneurysm size was 5.6±1.8 mm (range, 3.6–14.9 mm), and mean neck size was 3.8±1.0 mm (range, 1.9–8.7 mm). Though immediate postoperative adequate occlusion was low (11/63, 18%), adequate occlusion was achieved in 78.0% (46/59) and 79.2% (42/53) of the aneurysms at 12 months and 36 months, respectively. Four patients were retreated by the 12-month follow-up (4/63 (6.3%)) and three patients were retreated by the 36-month follow-up (3/63 (4.8%)). There were two major strokes (2/63 (3.2%)), one minor stroke (1/63 (1.6%)) and three incidents of intracranial hemorrhage in two subjects (2/63 (3.2%)) prior to the 12-month follow-up. There was one instance of mortality (1/63, 1.6%). Morbidity was 0% (0/63) and 1.8% (1/63) at the 12-month and 36-month follow-ups, respectively.

Conclusions

LUNA AES is safe and effective for the treatment of bifurcation and sidewall aneurysms.

Clinical trial registration

ISRCTN72343080; Results.

Keywords: aneurysm, endovascular procedures, flow disruption, LUNA device

Introduction

Endovascular aneurysm coiling is now a valid therapeutic option for treating cerebral aneurysms. In many countries, endovascular treatment is considered first for the treatment of ruptured and unruptured aneurysms. However, coiling, either as a standalone procedure or with the use of the balloon-enhanced (or balloon-remodeling) coiling technique, can be limited by the filling of only a limited percentage of the aneurysm volume, introducing the possibility of coil compaction and recanalization over time.1 Difficulty of coiling wide-necked aneurysms can be addressed with the use of adjunctive microstents.2 Stent-assisted coiling is also a valid alternative for treating wide-necked aneurysms. This treatment method is associated with significantly lower aneurysm recurrence rates compared with coiling alone.3 4 However, this method has an increased periprocedural rate of hemorrhagic complications related to antiplatelet treatment.5 Moreover, complex aneurysms, such as bifurcation and sidewall aneurysms, are challenging to treat using current therapies,6–8 leaving an unmet clinical need.

Recently, the concept of intra-aneurysmal flow disruption has emerged as a new paradigm for the treatment of primarily bifurcation aneurysms9–11 In contrast to other intra-aneurysmal flow diverters, the LUNA aneurysm embolization system (LUNA AES, Medtronic, Irvine, California, USA) is a flow disruption device intended to treat a broader array of aneurysms. The LUNA AES is a self-expanding intrasaccular flow disruption device that is placed inside the aneurysm cavity, providing a mesh of metal across the neck of the aneurysm that isolates it from the parent-artery blood flow. Its ovoid shape allows the device to treat either bifurcation or sidewall aneurysms. The purpose of our study was to evaluate the procedural, short-term, and long-term safety and effectiveness of the LUNA AES when used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions for use.

Materials and methods

Study purpose, device indications and participants

The LUNA AES Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up (PMCF) study is a registered, prospective, multicenter, single-arm, long-term (36-month) follow-up study of the first patients treated with the LUNA AES device. This PMCF study was specifically designed to collect safety and efficacy data on the LUNA AES for the treatment of saccular intracranial aneurysms in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFU). The LUNA AES is indicated for endovascular embolization of saccular intracranial bifurcation and sidewall aneurysms with a height of 4.7–12.6 mm, a width of 3.0–8.5 mm, and is not limited based on aneurysm dome-to-neck ratio.

Sixty-three subjects at nine European sites, including five sites in France and one each in Belgium, Italy, Sweden and Poland, were treated with the LUNA AES. Sixty-three subjects were screened and selected on an ‘intention-to-treat’ basis. Written informed consent was obtained for all subjects. Subject enrollment was initiated in June 2011 and completed in November 2013.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Each subject was required to meet all of the following inclusion criteria: must have been a candidate for aneurysm coiling between 18 and 75 years old; must have been diagnosed with an intracranial aneurysm matching the manufacturer’s IFU for the LUNA AES; and never have been previously treated. Exclusion criteria included any of the following conditions: the subject had a fusiform aneurysm; the target aneurysm had been previously treated by surgical or endovascular means; the presence of congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia, unstable coronary artery disease, respiratory disease, cancer or symptomatic infection; the subject had a history of drug use, alcoholism, or neurovascular or neurological disease; the use of contrast media or angiography was contraindicated for use in the subject; the subject had participated in a clinical drug trial within the previous 28 days; the subject was simultaneously using steroid or immunosuppressive therapy; and the subject had a comorbid disease or condition that was expected to compromise his or her ability to complete follow-up assessments at 6 months.

Treatment

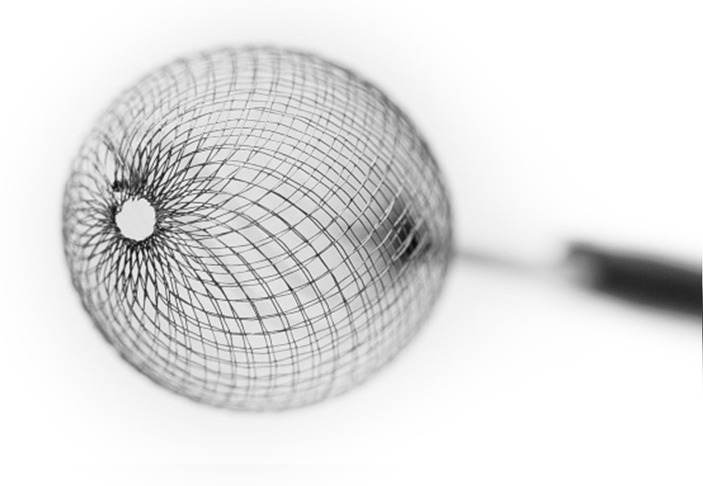

The LUNA AES is a self-expandable, round-to-ovoid implant made from a double layer of 72 nitinol 25 µm wires. The mesh (with a total of 144 wires) is secured at proximal and distal ends and marked with radiopaque markers (figure 1). Available sizes for the device are 4.5–8.5 mm. The delivery system allows distal navigation through all 0.027-inch compatible commercially available microcatheters. Detachment of the LUNA AES is mechanical and controlled by operator activation of a delivery handle. All procedures were conducted with 6-French guiding catheters or long-introducer sheaths. Microcatheters (with an internal lumen of 0.027 inches) for device delivery included Marksman or Rebar 27 (Covidien, Irvine, California, USA) and Excelsior 27 (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, California, USA).

Figure 1.

The LUNA aneurysm embolization system (AES) is a self-expandable, round-ovoid implant made from a double layer of 72 nitinol 25 µm wires. The mesh (made of a total of 144 wires) is secured at proximal and distal ends, and clearly marked with radiopaque markers. Available sizes for the device are 4.5–8.5 mm. The delivery system provides for distal navigation through all 0.027-inch compatible commercially available microcatheters. The detachment of the LUNA AES is mechanical and controlled by the operator activation of a delivery handle.

Data collection, postoperative follow-up schedule, and antiplatelet therapy

Each center completed a subject file with the following data: demographic information; aneurysm information, including rupture status, location, size and neck size; and procedure information, including date, size of device, access catheters used, perioperative medications, occurrence of complications, and use of additional devices during the procedure. A Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was collected for each subject before treatment and at discharge, and at 6-month, 12-month and 36-month follow-ups. Patients received antiplatelet therapy based on the discretion of the investigator or as per the standard of care at the institutions where the patient was treated. Angiographic assessment was completed by a blinded core laboratory for each follow-up.

Safety analysis

Adverse events (AEs) were categorized using previously specified definitions of neurological events of interest: stroke (major and minor), transient ischemic attack (TIA), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and retreatments. All AEs were reviewed and adjudicated by an independent clinical events committee (CEC). The CEC consisted of three independent neurovascular physicians and surgeons who reviewed and adjudicated each of the reported AEs.

Efficacy analysis

The efficacy variables were related to the ability of the device to embolize the intracranial aneurysm at various time points. Efficacy variables were blinded, analyzed and evaluated by one expert reader from an independent core laboratory. Specific variables evaluated in this study included the angiographic assessment of aneurysm occlusion grade according to the Raymond-Roy classification scale,12 parent-vessel compromise, and occlusion durability. Occlusion grade and parent-vessel compromise were assessed by angiography on the procedural baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-up angiograms. Angiographic data were available for 61, 60, 59 and 55 patients immediately post procedure, and at 6-month, 12-month and 36-month follow-up, respectively.

Follow-up schedule

The patients were followed up at 6, 12 and 36 months.

Statistical methods

Sixty-three eligible subjects were enrolled after informed consent was obtained, with the intent of having at least 50 evaluable subjects after accounting for a 20% dropout rate. With 50 evaluable subjects, the margin of error for a 95% CI based on any proportion should be under 14%. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics such as number of observations (n), mean, SD, median, minimum and maximum. Categorical variables were tabulated using frequency (n) and percentage (%). Because this was a post-market study focused exclusively on safety and efficacy, no control group was enrolled. All data manipulations and descriptive summaries were performed using SAS version 9.3 or later.

Results

Subject demographics and medical history

Sixty-three subjects with 64 aneurysms were enrolled for treatment in this study (one subject was re-enrolled for a second procedure to treat an additional aneurysm with a LUNA AES). Subject enrollment occurred between 13 June 2011 and 19 November 2013. The mean age was 52.4 (52 women, 82.5%; table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline subject characteristics

| Characteristics | n/N (%) |

| Age: mean±SD (N) (median) | 52.4±10.9 (63) (53) |

| Gender (female) | 52/63 (82.5%) |

| Modified Rankin Scale | |

| 0 | 52/63 (82.5%) |

| 1 | 6/63 (9.5%) |

| 2 | 5/63 (7.9%) |

| 3 | 1/63 (1.6%) |

| Arrhythmia/atrial fibrillation | 2/61 (3.3%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 5/63 (7.9%) |

| Connective tissue disorder | 1/62 (1.6%) |

| Diabetes – All | 4/63 (6.3%) |

| Insulin dependent | 1/4 (25%) |

| Controlled w/oral medication | 3/4 (75%) |

| Controlled w/diet | 1/4 (25%) |

| Hyperlipidemia requiring medication | 12/63 (19.0%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1/63 (1.6%) |

| Hypertension requiring medication | 22/63 (34.9%) |

| History of smoking | 35/63 (55.6%) |

| Stroke – all | 7/63 (11.1%) |

| Ischemic stroke | 6/63 (9.5%) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0/63 (0%) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 1/63 (1.6%) |

| Head trauma | 3/62 (4.8%) |

| Hydrocephalus | 2/63 (3.2%) |

| Seizure | 1/63 (1.6%) |

Aneurysm characteristics

At baseline, most aneurysms (60/63, 95.2%) were unruptured (table 2). Forty-nine of the 64 aneurysms (49/64, 76.6%) were either bifurcation or terminal aneurysms. Fifteen had a sidewall origin (15/64, 23.4%). Aneurysm sizes were considered small if <5 mm, medium if 5–10 mm and large if >10 mm. There were two large aneurysms (2/64, 3.1%), 37 medium (37/64, 57.8%) and 25 small (25/64, 39.1%). The dome-to-neck ratio was 1.46:1 for bifurcation/terminal aneurysms and 1.49:1 for sidewall aneurysms (table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline aneurysm characteristics

| Characteristics | |

| Aneurysm rupture status, n/N (%) | |

| Unruptured | 60/63 (95.2%) |

| Ruptured | 3/63 (4.8%) |

| Aneurysm location, n/N (%) | |

| Anterior communicating artery | 15/64 (23.4%) |

| Basilar artery apex | 4/64 (6.3%) |

| Middle cerebral arteries Internal carotid artery (ICA) terminus |

19/64 (29.7%) 8/64 (12.5%) |

| ICA, cavernous segment | 3/64 (4.7%) |

| ICA, ophthalmic segment | 3/64 (4.7%) |

| ICA, posterior communicating segment | 3/64 (4.7%) |

| ICA, hypophyseal segment | 3/64 (4.7%) |

| Posterior communicating artery | 3/64 (4.7%) |

| Anterior cerebral artery | 2/64 (3.1%) |

| Posterior inferior cerebellar artery | 1/64 (1.6%) |

| Aneurysm type, n/N (%) | |

| Sidewall | 15/64 (23.4%) |

| Bifurcation or terminal | 49/64 (76.6%) |

| Aneurysm size, n/N (%) | |

| Large: > 10 mm | 2/64 (3.1%) |

| Medium: 5–10 mm | 37/64 (57.8%) |

| Small: < 5 mm | 25/64 (39.1%) |

| Mean aneurysm width, mean±SD (range) | 5.6±1.8 mm (3.6–14.9 mm) |

| Bifurcation or terminal aneurysms | 5.7±2.0 mm (3.6–14.9 mm) |

| Sidewall aneurysms | 5.2±1.0 mm (3.9–7.1 mm) |

| Mean aneurysm neck size, mean±SD (range) | 3.8±1.0 mm (1.9–8.7 mm) |

| Bifurcation or terminal aneurysms | 3.9±1.1 mm (1.9–8.7 mm) |

| Sidewall aneurysms | 3.5±0.7 mm (2.4–5.3 mm) |

| Dome-to-neck ratio | |

| Bifurcation or terminal aneurysms | 1.46:1 |

| Sidewall aneurysms | 1.49:1 |

Procedural data

Sixty-one LUNA AES devices were implanted in 61 aneurysms in 60 subjects (one subject received two LUNA AES devices for the treatment of two aneurysms in two separate procedures). Three subjects did not receive a LUNA AES implant because deployment of the device failed. These subjects were treated with stent-assisted coiling (n=1), coils (n=1), and coils and balloon (n=1) because of aneurysm perforation with the microcatheter, inappropriate fit of the LUNA AES device for the aneurysm, and impossibility of device detachment due to vessel tortuosity. Of the 61 aneurysms treated with the LUNA AES device, three were treated with additional devices. One was treated with an additional stent and coils because of aneurysm recanalization due to LUNA AES device migration into the thrombus; another was treated with additional coils because of LUNA AES device failure due to bean-shaped opening of the device; and a third was treated with a flow diverter device due to incomplete occlusion of the aneurysm.

Intermediate catheters were used in 45 (45/61, 73.8%) procedures. Forty LUNA AES devices were delivered in the first attempt (40/64, 62.5%), 16 devices were deployed on the second attempt (16/64, 25.0%), and eight required more than two deployments (8/64, 12.5%). Each deployment attempt used a separate LUNA AES device. The mean number of attempts was 1.6 per procedure. The mean procedure time for LUNA AES implantation, which included LUNA AES inserted for the first time in the introducer sheath to final removal of the LUNA AES from the introducer sheath, was 13.6 min (range, 2–70 min). The mean total procedure time (skin to skin) was 119.9 min (range, 25–240 min).

Of 63 subjects, 55 (87.3%) received heparin, 18 (28.6%) received nimodipin, 4 (6.3%) received glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and 26 (41.3%) received aspirin. A combination of heparin and aspirin was administered in 22 (34.9%) subjects. Either heparin or aspirin was given to 59 (93.7%) subjects. Two subjects (3.2%) did not receive either heparin or antiplatelet medications. Of the four patients who received glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, the treatment was administered due to a blood clot in the distal artery at the end of the intervention in two subjects (2/63, 3.2%) (there was no clinical consequence in either case), stent placement in one subject (1.6%), and an intra-arterial protrusion of the LUNA AES device at the end of the implant procedure without thrombotic formation or clinical consequence in the other subject (1.6%).

Device effectiveness

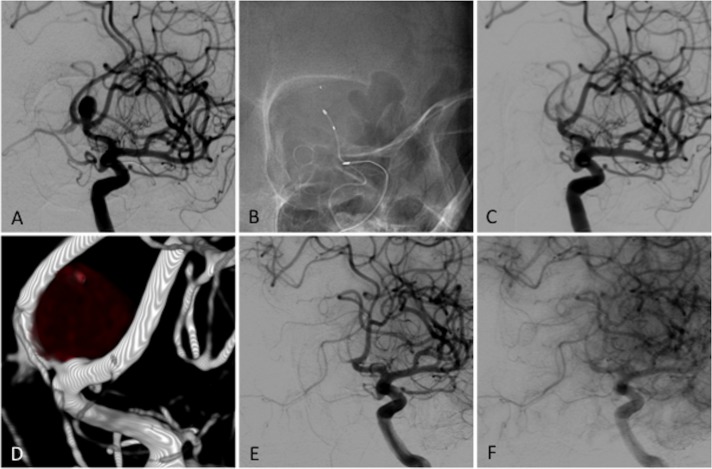

Post-procedure angiographic evaluation was performed for all 61 LUNA AES-treated aneurysms; 6-month follow-up data were evaluated in 60 aneurysms, 12-month follow-up data for 59 aneurysms, and 36-month follow-up data for 55 aneurysms (tables 3 and 5). Immediately after LUNA AES implantation, adequate occlusion (complete occlusion plus residual neck) was observed in 11/61 aneurysms (18.0%), and residual aneurysm was observed in 50/61 aneurysms (82.0%). At the 6 -month follow-up, adequate occlusion was reported in 49/60 aneurysms (81.7%); in 46/59 aneurysms (78.0%) at the 12-month follow-up; and in 42/53 aneurysms (79.2%) at the 36-month follow-up (table 3). Table 5 provides an additional breakdown of the occlusion data by the sizes of the treated aneurysms over the course of the study (small, <5 mm; medium, 5–10 mm; and large, >10 mm). We found that, at all timepoints, the complete occlusion rate of small aneurysms was higher than that of medium aneurysms, and though we had only two large aneurysms, this category had the lowest occlusion rates. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) also showed decreased aneurysmal filling with contrast stagnation in the aneurysm sac in a majority of cases. Figure 2 shows an example of occlusion at the 36-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Modified Rankin Scale (mRS), mortality and morbidity

| mRS score | Patients, n (%) | ||||

| Baseline n=64 |

Discharge n=63 |

6 months n=61 |

12 months n=59 |

36 months n=55 |

|

| 0 | 52 (81.2%) | 55 (87.3%) | 56 (91.8%) | 54 (91.5%) | 48 (87.3%) |

| 1 | 6 (9.4%) | 6 (9.5%) | 3 (4.9%) | 4 (6.8%) | 6 (10.9%) |

| 2 | 5 (7.8%) | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (3.3%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| 3 | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 4–6 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Occlusion grade* | Procedure n=61 |

6 months n=60 |

12 months n=59 |

36 months n=53 |

|

| Adequate occlusion (complete occlusion+residual neck) | 11 (18.0%) | 49 (81.7%) | 46 (78.0%) | 42 (79.2%) | |

| Complete occlusion | 4 (6.6%) | 25 (41.7%) | 27 (45.8%) | 24 (45.3%) | |

| Residual neck | 7 (11.5%) | 24 (40.0%) | 19 (32.2%) | 18 (34.0%) | |

| Residual aneurysm | 50 (82.0%) | 11 (18.3%) | 13 (22.0%) | 11 (20.7%) |

| Procedure n=63 |

Discharge n=63 |

6 months n=63 |

12 months n=62 |

36 months n=56 |

|

| Thromboembolic events | 2 (3.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Symptomatic without sequelae | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Symptomatic with sequelae | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Intraprocedural rupture | 2 (3.2%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Morbidity† | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.79%) |

| Mortality | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.79%) |

*Occlusion grade obtained from core laboratory data.

†Defined as mRS>2 if baseline ≤2; mRS+1 or more if baseline >2; mRS>2 if ruptured at baseline.

Table 5.

Aneurysm occlusion status by size

| Aneurysm size | Extent of occlusion at 6-month follow-up | Extent of occlusion at 12-month follow-up | Extent of occlusion at 36-month follow-up | |||||||||

| Complete | Near complete | Incomplete | Number measured | Complete | Near complete | Incomplete | Number measured | Complete | Near complete | Incomplete | Number measured | |

| Small (<5 mm) |

5/10 (50.0%) | 3/10 (30.0%) | 2/10 (20.0%) | 10 | 6/10 (60.0%) | 2/10 (20.0%) | 2/10 (20.0%) | 10 | 6/9 (66.7%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 9 |

| Medium (5–10 mm) |

21/51 (41.2%) | 22/51 (43.1%) | 8/51 (15.7%) | 51 | 21/48 (43.8%) | 17/48 (35.4%) | 10/48 (20.8%) | 48 | 18/44 (40.9%) | 18/44 (40.9%) | 8/44 (18.2%) | 44 |

| Large (>10 mm) |

0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/2 (100%) | 2 | 0/2 (0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 2 | 0/2 (0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 2 |

| Totals by occlusion grade | 26/63 (41.3%) | 25/63 (39.7%) | 12/63 (19.0%) | 63 | 27/60 (45.0%) | 20/60 (33.3%) | 13/60 (21.6%) | 60 | 24/55 (43.6%) | 20/55 (36.4%) | 11/55 (20%) | 55 |

Figure 2.

Occlusion example. (A) Baseline angiography for a patient with a 8.0 mm anterior communicating saccular aneurysm. (B) Plain radiograph during the LUNA aneurysm embolization system (AES) implantation. (C) Immediate control angiogram after implantation showing flow reduction within the aneurysm. The same patient at 36-month follow-up with 3D angiography: (D) early arterial phase of angiography; (F) late arterial phase showing complete circulatory exclusion of the aneurysm.

No LUNA AES-treated aneurysm bled or re-bled during the follow-up period. Retreatment was performed in four subjects within 12 months (4/63, 6.3%). In one subject, 6-month follow-up DSA showed complete recanalization of an initially partially thrombosed aneurysm due to migration of the LUNA AES device into the thrombus. In another subject, recanalization of the LUNA AES-treated aneurysm was noted at 6-month follow-up, requiring retreatment. Two additional retreatments were performed in two subjects owing to inadequate aneurysm occlusion (inadequate LUNA AES deployments that were not seen at the time of the procedure).

Safety outcomes

The baseline mRS score was determined in all 64 aneurysms (one subject had two aneurysms treated in separate procedures, and completed mRS evaluations for each aneurysm); mean score was 0.3. At 6-month, 12-month and 36-month follow-up, mean mRS score was 0.1. At the 12-month follow-up, 27 AEs had occurred; by the 36-month follow-up, 44 AEs had occurred in 27 subjects (27/63, 42.9%). The independent CEC adjudicating AEs determined that 10 of those 44 AEs were device related and 6 were procedure related (online supplementary material).

neurintsurg-2018-013767supp001.doc (86.5KB, doc)

Mortality, morbidity and neurological adverse events of interest

Two of the 63 subjects experienced a major stroke (2/63, 3.2%; table 4), including one on day one due to a procedure-related carotid dissection. The event resolved without sequelae within 4 days. The other major stroke occurred within the 12-month follow-up period during treatment of a concomitant aneurysm with coils and stents, causing a left hemiparesis with a mRS of 3 and persistent neurological deficit (≥4-point NIH Stroke Scale score). Within 12 months, another patient experienced a minor stroke due to an embolic migration at a contralateral vessel during follow-up angiography at the 1-year visit resulting in an increase in mRS from 0 to 1. Three subjects experienced a TIA; subjects recovered within 24 hours. Three incidents of ICH occurred in two of the 63 subjects (2/63, 3.2%). One subject had two incidents of ICH on the day of the procedure, an intraventricular hemorrhage and a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), which were due to perforation of an aneurysm caused by a microcatheter. The second ICH, an SAH, occurred on day 71 due to spontaneous rupture of a contralateral untreated, non-index, middle cerebral artery aneurysm that was unrelated to the target aneurysm and not treated with a LUNA AES device. The last ICH resulted from the perforation of an aneurysm caused by a microcatheter mentioned above. This was one of two procedural ruptures (2/63, 3.2%); the other occurred in a cavernous aneurysm due to a guidewire perforation. The event led to a carotid cavernous fistula that spontaneously healed and did not lead to an ICH; therefore, the CEC did not adjudicate that event as an ICH.

Table 4.

Neurological adverse events of interest

| Events | Total, n/N (%) | 0–24 hours, n/N (%) | >24 hours–30 days, n/N (%) | 31 days–1 year, n/N (%) | 1–3 years, n/N (%) |

| Stroke | |||||

| Major | 2/63 (3.2%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 1/63 (1.6%) | 1/62 (1.6%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| Minor | 1/63 (1.6%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 1/62 (1.6%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| TIA | 3/63 (4.8%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 2/63 (3.2%) | 0/62 (0.0%) | 1/56 (1.8%) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 2/63 (3.2%)* | 1/63 (1.6%)* | 0/63 (0.0%) | 1/62 (1.6%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| SAH | 2/63 (3.2%) | 1/63 (1.6%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 1/62 (1.6%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| IPH | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/62 (0.0%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| EDH | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/62 (0.0%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| SDH | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/62 (0.0%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

| IVH | 1/63 (1.6%) | 1/63 (1.6%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | 0/62 (0.0%) | 0/56 (0.0%) |

*In these cases, one patient had two intracranial hemorrhage events in the given period and was counted only once.

EDH, epidural hemorrhage; IPH, intraparenchymal hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SDH, subdural hemorrhage; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

There was one instance of mortality that occurred between the 12-month and 36-month follow-ups. At 1.6 years post enrollment, the subject presented with bladder carcinoma with pulmonary metastases. The subject had two operations for the carcinoma while undergoing chemotherapy and died 2.3 years post enrollment. This AE was adjudicated as serious in seriousness, severe in severity, related to concomitant disease and death as outcome.

Parent-vessel compromise after device deployment

Angiographic evaluation immediately after the procedure to detect parent-vessel compromise showed complete occlusion of the parent vessel in 2/61 aneurysms (3.3%), partial occlusion of more than 50% of the parent vessel in 2/61 (3.3%) aneurysms, and partial occlusion of up to 50% of the parent vessel was observed in 4/61 (6.6%) aneurysms. There were two ischemic events reported in cases of less than 50% parent vessel occlusion with LUNA AES protrusion (2/8; 25%). There was one ischemic event reported in a case in which there was no LUNA AES protrusion (1/52; 1.9%). Overall, there was a significant relationship between LUNA AES protrusion and the occurrence of an ischemic event (p=0.0442).

Antiplatelet therapy during follow-up

Four subjects took aspirin and one subject took both aspirin and clopidogrel at up to 1-month follow-up. At up to 3-month follow-up, one subject took aspirin and one took clopidogrel. Through 6-month follow-up, two subjects took aspirin and one took both aspirin and clopidorel. At 9-month follow-up, one subject took aspirin and one took both aspirin and clopidogrel. At 12-month follow-up, one subject took aspirin. At 18-month follow-up, five subjects took aspirin and two subjects took clopidorel. At up to 30-month follow-up, two subjects took aspirin. Through 36-month follow-up, 10 subjects took aspirin, one took clopidogrel, and one took both.

In 60 patients with successful LUNA AES implant, there were three ischemic events: 3 in 33 subjects with postoperative antiplatelet use and 0 in 27 with no postoperative antiplatelet use. There was no significant difference in rates of ischemic event by postoperative antiplatelet use (p=0.2449).

Discussion

Our study’s results support the safety and efficacy of the LUNA AES for the treatment of unruptured bifurcation and sidewall intracranial aneurysms of a wide range of sizes. This series represents the first cohort of subjects ever treated with the LUNA AES device. Analysis of the treated population showed excellent LUNA AES implantation success, with implantation in 61/64 aneurysms (95.3%) and limited use of adjunctive implant devices (7/61, 11.5%). Both sidewall and bifurcation aneurysms were successfully treated. Treatment was most effective for small aneurysms and least effective for large aneurysms, though our sample size of large aneurysms was small (table 5). The LUNA AES might also be effective based on our observations after treatment of three patients with ruptured aneurysms, though the sample size in this series was small and further studies are warranted to determine its safety and efficacy in treating ruptured aneurysms. Symptomatic device-related or procedure-related thromboembolic events in the first 30 days consisted of two TIAs and one major stroke. Parent vessel compromise occurred in 8 of 63 patients, including four instances of >50% parent vessel occlusion, although no ischemic events were reported in these four patients. Adequate aneurysm occlusion at 1-year follow-up was achieved in a significant majority of aneurysms with low morbidity and mortality.

Comparison between LUNA AES and the WEB device

Intra-aneurysmal flow disruption has dramatically altered the landscape of aneurysm treatment, particularly the WEB device.9–11 WEB is a self-expanding nitinol microbraid mesh implant delivered through a catheter and sized to fit and occlude an aneurysm in a single step with a single device, thereby limiting procedural time. However, the WEB device specifically addresses wide-necked aneurysms and is limited to the treatment of bifurcation aneurysms. The LUNA AES can address a wider range of aneurysms; however, in our study, the majority of aneurysms were <10 mm and unruptured, meaning further study is needed of larger and ruptured aneurysms. The rate of thromboembolic events in our study was comparable to that seen in three studies evaluating the WEB device (9.6%, 7.6% and 15.0%)9–11 and in large coiling series (7.1% in ATENA13 and 12.5% in CLARITY).14 Morbidity and mortality were low in our study of LUNA AES and in studies of the WEB device.11 15 Although our series reported four retreatment cases due to incomplete occlusion from failure of proper device deployment or device migration, we did not note any instances of compression at follow-up, unlike the WEB device.16 17 Thus, the LUNA AES device is limited to at least one mechanism of potential device failure. One subject presented with a cerebral abscess 34 days after LUNA AES implantation that necessitated hospital readmission. The occurrence of an infectious complication after aneurysm coiling is unlikely but has been previously reported.18–20

There was no morbidity or mortality at 1-month follow-up, confirming the safety of LUNA AES treatment. In the WEBCAST and French Observatory series of WEB, morbidity and mortality at 1-month follow-up after implantation of the WEB device were 2.7% and 0.0%, respectively.11 In the WEB Intrasaccular Therapy (WEB IT) study, the morbidity and mortality at 1-month follow-up were 0.7% and 0.0%, respectively.15 In our study, at 6-month follow-up, the morbidity was 1.8% because of the rupture of an untreated contralateral aneurysm. At 12-month follow-up, morbidity was 1.8% because of the treatment with coils of a previously untreated aneurysm, and mortality was 1.8%. In comparison, 12-month neurological morbidity and mortality in the WEBCAST and French Observatory study were 0.0% and 1.0%, respectively.11 None of the LUNA AES-treated aneurysms re-bled during the 36-month observational period.

The occlusion rates in our study were similar to results reported in the WEBCAST and French Observatory studies conducted with the WEB device in the treatment of bifurcation aneurysms, showing an adequate occlusion rate of 82.0% at 1-year follow-up11; however, the WEB device is limited to use in wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms. The anatomical results observed in our study are comparable to previous series dealing with small aneurysms treated by coiling because our inclusion criteria allowed inclusion of aneurysms that are otherwise treatable by simple or balloon-assisted coiling. However, LUNA AES can be deployed more quickly than coils, reducing procedure time, and each additional coil loop added to an aneurysm introduces the risk of rupturing the aneurysm, while LUNA AES only needs to be placed once. The 0.027-inch catheter may introduce risks of perforation or difficulty deploying the LUNA AES device. Aneurysm occlusion occurred more rapidly during the first 6 months and was relatively stable by 1 year.

Retreatment, safety and potential advantages of LUNA AES

Retreatment was performed in four subjects because the LUNA AES device behaved similarly to coils in those instances: the implant progressively migrated within the preexisting aneurysmal fundus clot in a manner previously observed with the WEB device.21 The LUNA AES retreatment rates observed in this study are similar to those seen with the WEB device and with bare and hydrogel coils.11 22 Higher retreatment rates have been seen with Cerecyte coils, bare platinum or polyglycolic-lactic acid (PGLA)-coated coils.23–25 A partially thrombosed aneurysm is recognized as a favoring factor for aneurysm rapid recanalization after coiling.26 However, because indications for aneurysm retreatment are not strictly established, future studies specifically comparing the various available coil types and flow disruption devices will be needed to identify any statistically significant differences in outcomes.

Overall, our findings not only indicate that LUNA AES treatment according to the manufacturer’s indications is indeed safe and effective, but they also suggest that LUNA AES may offer some advantages over current standard therapies. Its relatively fast deployment reduces procedure time, and our safety and efficacy data point to an extremely low risk of rupture. In addition, LUNA AES is designed as a single-device treatment for an entire aneurysm, eliminating the increased risk of rupture present each time a coil loop is released into the aneurysm. However, future comparative randomized and controlled studies will be needed to determine whether LUNA AES offers therapeutic advantages compared with standard methods, and, if so, when specifically it may be indicated.

Limitations

This prospective series has the inherent limitations of a single-arm, non-randomized study. The concept of intrasaccular flow disruption was validated for small and medium aneurysms with favorable dome-to-neck ratios, but needs further testing for large aneurysms and wider-necked aneurysms. Our study included only a small number of acutely ruptured aneurysms, making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the use of the LUNA AES with ruptured aneurysms.

Conclusions

The LUNA AES is similar in safety and efficacy to coiling for treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Rates of morbidity and mortality were low, and adequate occlusion was achieved in a majority of cases.

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Contributors: MP, AB, NS, CM, MJ, SM, TA, MSö, PG, RéA, RëB: made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This research received funding from Medtronic.

Competing interests: MP, consultancy agreement with Medtronic, Stryker, MicroVention, Penumbra, Balt; AB, none; NS, none; CM, consultancy agreement with Medtronic and MicroVention; MJ, none; SM, consultancy agreement with Codman; TA, none; MS, none; PG, none; RA, none; RB, consultancy agreement with Medtronic, Stryker, MicroVention, Penumbra, Balt.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France XI.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors are making available any additional unpublished data, such as unprocessed data, protocols, or images. The data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Crobeddu E, Lanzino G, Kallmes DF, et al. Review of 2 decades of aneurysm-recurrence literature, part 1: reducing recurrence after endovascular coiling. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:266–70. 10.3174/ajnr.A3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piotin M, Blanc R. Balloons and stents in the endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms: vascular anatomy remodeled. Front Neurol 2014;5:41 10.3389/fneur.2014.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lawson MF, Newman WC, Chi YY, et al. Stent-associated flow remodeling causes further occlusion of incompletely coiled aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2011;69:598–604. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182181c2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piotin M, Blanc R, Spelle L, et al. Stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms: clinical and angiographic results in 216 consecutive aneurysms. Stroke 2010;41:110–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.558114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishido H, Piotin M, Bartolini B, et al. Analysis of complications and recurrences of aneurysm coiling with special emphasis on the stent-assisted technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:339–44. 10.3174/ajnr.A3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Albuquerque FC, Gonzalez LF, Hu YC, Yc H, et al. Transcirculation endovascular treatment of complex cerebral aneurysms: technical considerations and preliminary results. Neurosurgery 2011;68:820–30. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182077f17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sani S, Lopes DK. Treatment of a middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysm using a double neuroform stent “y” configuration and coil embolization: technical case report. Oper Neurosurg 2005;57:E209 10.1227/01.NEU.0000163684.75204.CD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Darflinger RJ, Chao K. Using the Barrel Technique with the LVIS Jr (Low-profile Visualized Intraluminal Support) Stent to Treat a Wide Neck MCA Bifurcation Aneurysm. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2015;8:25–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papagiannaki C, Spelle L, Januel AC, et al. WEB intrasaccular flow disruptor-prospective, multicenter experience in 83 patients with 85 aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:2106–11. 10.3174/ajnr.A4028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liebig T, Kabbasch C, Strasilla C, et al. Intrasaccular flow disruption in acutely ruptured aneurysms: a multicenter retrospective review of the use of the WEB. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:1721–7. 10.3174/ajnr.A4347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pierot L, Spelle L, Molyneux A, et al. Clinical and anatomical follow-up in patients with aneurysms treated with the WEB device: 1-year follow-up report in the cumulated population of 2 prospective, multicenter series (WEBCAST and French Observatory). Neurosurgery 2016;78:133–41. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roy D, Milot G, Raymond J. Endovascular treatment of unruptured aneurysms. Stroke 2001;32:1998–2004. 10.1161/hs0901.095600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pierot L, Spelle L, Vitry F, et al. Immediate clinical outcome of patients harboring unruptured intracranial aneurysms treated by endovascular approach: results of the ATENA study. Stroke 2008;39:2497–504. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.512756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cognard C, Pierot L, Anxionnat R, et al. Results of embolization used as the first treatment choice in a consecutive nonselected population of ruptured aneurysms: clinical results of the Clarity GDC study. Neurosurgery 2011;69:837–42. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182257b30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiorella D, Molyneux A, Coon A, et al. WEB-IT Study Investigators. Demographic, procedural and 30-day safety results from the WEB Intra-saccular Therapy Study (WEB-IT). J Neurointerv Surg 2017;9:1191–6. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cognard C, Januel AC. Remnants and recurrences after the use of the WEB intrasaccular device in large-neck bifurcation aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2015;76:522–30. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sivan-Hoffmann R, Gory B, Riva R, et al. One-year angiographic follow-up after WEB-SL endovascular treatment of wide-neck bifurcation intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:2320–4. 10.3174/ajnr.A4457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. AL-Okaili R, Patel SJ. Brain abscess after endovascular coiling of a saccular aneurysm: case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:697–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen G, Zhan S, Chen W, et al. Brain abscess after endosaccular embolisation of a cerebral aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci 2014;21:163–5. 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Falagas ME, Nikou SA, Siempos II. Infections related to coils used for embolization of arteries: review of the published evidence. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2007;18:697–701. 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anil G, Goddard AJ, Ross SM, et al. WEB in partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms: a word of caution. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37 10.3174/ajnr.A4604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. White PM, Lewis SC, Gholkar A, et al. Hydrogel-coated coils versus bare platinum coils for the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms (HELPS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:1655–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60408-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pierot L, Cognard C, Ricolfi F, et al. Mid-term anatomic results after endovascular treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils and Matrix coils: analysis of the CLARITY series. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:469–73. 10.3174/ajnr.A2771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Molyneux AJ, Clarke A, Sneade M, et al. Cerecyte coil trial: angiographic outcomes of a prospective randomized trial comparing endovascular coiling of cerebral aneurysms with either cerecyte or bare platinum coils. Stroke 2012;43:2544–50. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.657254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McDougall CG, Johnston SC, Gholkar A, et al. Bioactive versus bare platinum coils in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: the MAPS (Matrix and Platinum Science) trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:935–42. 10.3174/ajnr.A3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferns SP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, et al. Partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms presenting with mass effect: long-term clinical and imaging follow-up after endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:1197–205. 10.3174/ajnr.A2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

neurintsurg-2018-013767supp001.doc (86.5KB, doc)