The translocon at the outer envelope membrane of chloroplast Toc132 plays an important role in alleviating arsenic toxicity in chloroplasts.

Abstract

Arsenic (As) is highly toxic to plants and detoxified primarily through complexation with phytochelatins (PCs) and other thiol compounds. To understand the mechanisms of As toxicity and detoxification beyond PCs, we isolated an arsenate-sensitive mutant of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), arsenate induced chlorosis1 (aic1), in the background of the PC synthase-defective mutant cadmium-sensitive1-3 (cad1-3). Under arsenate stress, aic1 cad1-3 showed larger decreases in chlorophyll content and the number and size of chloroplasts than cad1-3 and a severely distorted chloroplast structure. The aic1 single mutant also was more sensitive to arsenate than the wild type (Columbia-0). As concentrations in the roots, shoots, and chloroplasts were similar between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3. Using genome resequencing and complementation, TRANSLOCON AT THE OUTER ENVOLOPE MEMBRANE OF CHLOROPLAST132 (TOC132) was identified as the mutant gene, which encodes a translocon protein involved in the import of preproteins from the cytoplasm into the chloroplasts. Proteomic analysis showed that the proteome of aic1 cad1-3 chloroplasts was more affected by arsenate stress than that of cad1-3. A number of proteins related to chloroplast ribosomes, photosynthesis, compound synthesis, and thioredoxin systems were less abundant in aic1 cad1-3 than in cad1-3 under arsenate stress. Our results indicate that chloroplasts are a sensitive target of As toxicity and that AIC1/Toc132 plays an important role in protecting chloroplasts from As toxicity.

Arsenic (As), a class 1 carcinogen (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004), is widely distributed in the environment. In some areas of south and southeast Asia, agricultural soils are contaminated with As due to mining, irrigation with As-laden groundwater, and industrial activities, resulting in increased risk of As accumulation in crop plants (Meharg and Rahman, 2003; Williams et al., 2009). High As concentrations in crop plants can present a significant risk to human health through dietary exposure (Meharg et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010). In more heavily contaminated soils, crop plants may suffer from phytotoxicity of As, resulting in substantial yield losses (Panaullah et al., 2009; Huhmann et al., 2017). Therefore, it is important to understand how plants cope with As toxicity.

Arsenate [As(V)] and arsenite [As(III)] are the main As species present in soil. The two inorganic As species are interconvertible depending on the environmental conditions. As(V) is the predominant form of As in soil under aerobic conditions. As(V) is a chemical analog of phosphate (Pi) and is taken up by Pi transporters. In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), there are nine genes in the PHOSPHATE TRANSPORT1 (PHT1) family (PHT1–PHT9) encoding Pi transporters. PHT1;1 and PHT1;4 contribute to As(V) uptake in Arabidopsis (Shin et al., 2004). After absorption, As(V) is reduced rapidly to As(III) by HIGH ARSENIC CONTENT1 (HAC1)/ARSENATE TOLERANT QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCUS1 in Arabidopsis roots (Chao et al., 2014; Sánchez-Bermejo et al., 2014). Plants lacking HAC1 show decreased As(III) efflux, increased sensitivity to As(V), and greatly increased As accumulation in aboveground tissues (Chao et al., 2014; Sánchez-Bermejo et al., 2014). Similarly, several OsHAC proteins in rice (Oryza sativa) play important roles in As(V) reduction, tolerance, and accumulation (Shi et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017). In contrast to As(V), As(III) is present predominantly as an undissociated neutral molecule under normal environmental conditions and is taken up by plant roots via aquaporin channels (Bienert et al., 2008; Isayenkov and Maathuis, 2008; Ma et al., 2008; Kamiya et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2015).

As(V) and As(III) are both toxic to plants, but the modes of action are different. As(V) competes with Pi for phosphorylation reactions and can replace Pi from biomolecules (Finnegan and Chen, 2012). As(V) esters are much less stable than Pi esters and hydrolyze quickly under physiological conditions, causing uncoupling of phosphorylation (Baer et al., 1981; Finnegan and Chen, 2012). By contrast, As(III) binds to dithiol reactive compounds and enzymes containing closely spaced Cys residues, disrupting their structures and catalytic functions (Chen et al., 2010; Finnegan and Chen, 2012; Shen et al., 2013). In plant cells, As(III) is detoxified primarily through complexation with phytochelatins (PCs) and other thiol compounds (Clemens et al., 1999; Ha et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2010a). Several As(III)-PC complexes have been detected in plant tissues (Raab et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2010a). Mutations in the genes encoding phytochelatin synthase (PCS) and γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase in Arabidopsis cause hypersensitivity to As (Ha et al., 1999; Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2010a). As(III)-PC complexes are transported into the vacuoles for sequestration via the tonoplast transporters ABCC1 and ABCC2 (Song et al., 2010). The abcc1/2 double mutant also is hypersensitive to As (Song et al., 2010).

In As nonhyperaccumulators, translocation of As from the roots to the shoots is generally limited (Zhao et al., 2009). Despite limited translocation, As reaching the shoot tissues can disrupt a range of physiological and biochemical processes, resulting in decreased chlorophyll content, suppression of the photochemistry in PSII, and increased oxidative stress (Mishra et al., 2014, 2016; Iriel et al., 2015; Srivastava et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2018). A common symptom of As toxicity is leaf chlorosis (Jain and Gadre, 1997; Srivastava et al., 2017), suggesting that chloroplasts are a possible target of As toxicity. However, little is known about how chloroplasts cope with As toxicity.

In this study, we isolated an As(V)-sensitive mutant of Arabidopsis, arsenate induced chlorosis1 (aic1), in the background of the PCS-defective cadmium sensitive1-3 (cad1-3) mutant. We showed that the AIC1 gene is TRANSLOCON AT THE OUTER ENVOLOPE MEMBRANE OF CHLOROPLASTS132 (TOC132), encoding a translocon protein involved in the import of preproteins from the cytoplasm to the chloroplast (Kubis et al., 2004). Furthermore, we showed that the chloroplast proteome in the mutant was more affected by As(V) than that in the wild type. Our results demonstrate that AIC1/Toc132 plays an important role in protecting chloroplasts from As toxicity.

RESULTS

Isolation of an As(V)-Induced Chlorosis Mutant

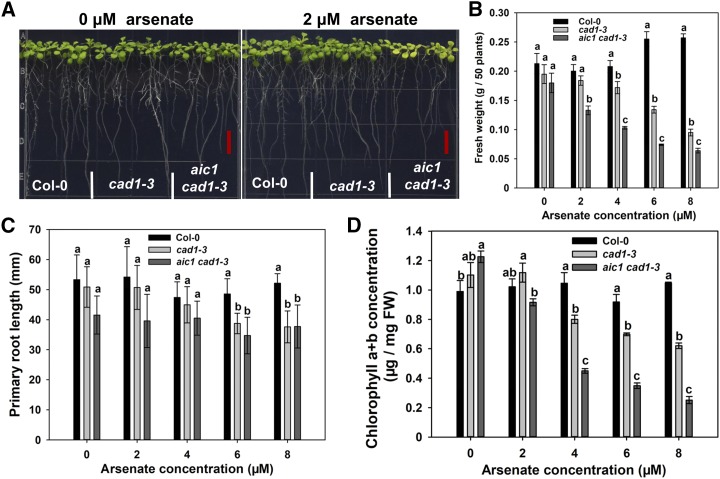

To explore the target of As toxicity and the mechanism of As detoxification beyond PC complexation, we isolated an As(V) hypersensitive mutant from an ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized library of cad1-3, which lacks the functional PCS (At5G44070; Ha et al., 1999). We named this mutant aic1 cad1-3 to indicate its double mutant status. The aic1 cad1-3 plants showed chlorotic leaves in the presence of 2 μm As(V), whereas cad1-3 was normal (Fig. 1A). The aic1 cad1-3 mutant had significantly lower chlorophyll content and lower shoot fresh weight than cad1-3 at As(V) concentrations of 2 μm or above, whereas chlorophyll content and shoot biomass of cad1-3 also were significantly lower than those in the wild type (Col-0) at As(V) concentrations of 4 μm or above (Fig. 1, B and D). In contrast, no significant difference was found in root length between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 across the range of As(V) concentrations tested (0–8 μm), although both showed a significantly smaller root length than Col-0 at 6 and 8 μm As(V) (Fig. 1C). The aic1 cad1-3 mutant also was more sensitive to As(III) than cad1-3, but the two showed similar sensitivity to Cd or Cu (Supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that the phenotype was caused specifically by As toxicity.

Figure 1.

Phenotype of aic1 cad1-3. A, Phenotypic comparison of Columbia-0 (Col-0), cad1-3, and aic1 cad1-3 grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium containing 0 or 2 μm As(V) for 10 d. Bars (red) = 1 cm. B to D, Fresh weight (B), primary root length (C), and chlorophyll content (D) of seedlings germinated and grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 μm As(V) for 10 d. Data are means ± se (n = 3) for fresh weight and chlorophyll content analysis and (n = 8) for primary root length. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences within treatments (P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight.

As(V) Affects Chloroplast Number and Morphology in aic1 cad1-3

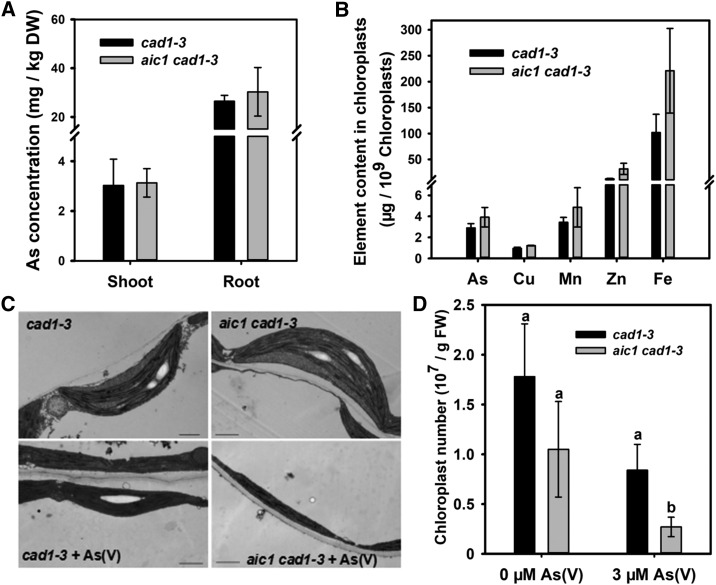

We next tested aic1 cad1-3 As(V) uptake ability in a hydroponic experiment. After exposure to 5 μm As(V) for 3 d, there was no significant difference between cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3 in total As concentrations in the roots or shoots (Fig. 2A), suggesting that aic1 cad1-3 had a similar As(V) uptake ability to cad1-3. We also determined the concentrations of As and other elements in the chloroplasts isolated from cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3. As was detectable in the chloroplasts, but there was no significant difference between cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3 (Fig. 2B). The concentrations of Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn also were not significantly different between the two lines (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

As uptake, elemental concentrations in chloroplasts, and number and structure of chloroplasts in aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3. A, As concentrations in the roots and shoots of plants grown in one-fifth-strength Hoagland hydroponic medium containing 5 μm As(V) for 3 d. DW, Dry weight. B, Chloroplast elemental concentrations in cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3. Intact chloroplasts were isolated from plants grown on 1/2 MS medium with 2 μm As(V) for 15 d. C, Transmission electron micrographs of chloroplasts from cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3. Plants were grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 or 8 μm As(V) for 10 d. Bars = 1 μm. D, Number of chloroplasts. Plants were grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 or 3 μm As(V) for 15 d. Data are means ± se (n = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences within treatments (P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight.

We observed the morphology of chloroplasts with a transmission electron microscope. In the absence of As(V), the chloroplasts of cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3 showed normal structure, with grana of thylakoids and starch granules both visible (Fig. 2C). In the 8 μm As(V) treatment, chloroplasts were smaller in cad1-3 and especially in aic1 cad1-3. The granae structure also disappeared (Fig. 2C). Moreover, no starch granules were observed in the chloroplast of aic1 cad1-3. As(V) treatment decreased the number of chloroplasts in both lines. In the presence of As(V), the number of chloroplasts in aic1 cad1-3 was significantly smaller than that in cad1-3 (Fig. 2D). These results indicate that As(V) inhibited chloroplast biogenesis, and the effect was more severe on aic1 cad1-3 than on cad1-3.

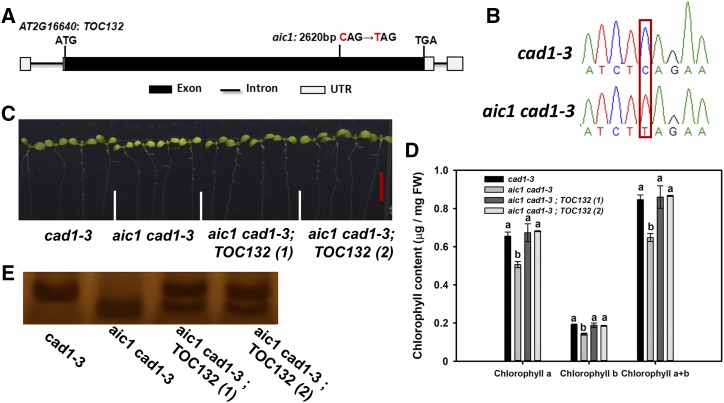

TOC132 Is the Mutant Gene of aic1

To identify the mutant gene responsible for the As(V) hypersensitive phenotype, we conducted a backcross between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3. The F1 offspring showed the phenotype of cad1-3. Among the 285 F2 plants, 221 and 64 plants showed normal and chlorotic phenotypes under As(V) treatment, respectively. The segregation pattern was consistent with the 3:1 ratio (χ2 = 0.98, P > 0.05), indicating that the As(V) hypersensitive phenotype was controlled by a recessive gene. To clone the mutant gene, genomic resequencing mapping was performed on the backcrossed F2 progeny with the aic1 cad1-3 phenotype using cad1-3 as the control. Using MutMap analysis (Abe et al., 2012), a region containing nonsynonymous mutations in two genes on chromosome 2 was identified as the mutant region. Using derived cleaved amplified polymorphism (dCAPS) markers, the most tightly linked mutation was with At2G16640 (Supplemental Table S1). The mutation in At2G16640 occurred at 2,620 bp (CAG to TAG) in the exon, resulting in the change of Gln to a stop codon (Fig. 3, A and B). At2G16640 is annotated as TOC132, encoding a translocon at the outer envelope membrane of the chloroplast (Ivanova et al., 2004; Kubis et al., 2004). To verify that the As(V) hypersensitivity of aic1 cad1-3 was caused by the point mutation of TOC132, mutant plants were transformed with the full genomic sequence of TOC132 driven by its own promoter. Two independent transgenic lines were selected (Fig. 3E). In the presence of 4 μm As(V), leaf chlorophyll content was rescued to the level of cad1-3 plants in the two complementary lines (Fig. 3, C and D). These results indicate that the As(V) hypersensitivity of aic1 cad1-3 was caused by the point mutation of TOC132. In cad1-3 plants, the expression of TOC132 was not affected by As(V) treatment (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 3.

Cloning and complementation analysis of the mutant gene. A, Genomic structure of TOC132 and the mutation site. B, DNA sequence of the point mutation in toc132. The red box indicates the mutation position. C and D, Photographs (C) and chlorophyll content (D) of cad1-3, aic1 cad1-3, and two independent complementation lines. Seedlings were grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 4 μm As(V) for 10 d. Bar (red) = 1 cm. Data are means ± se (n = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between genotypes (P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight. E, Genotype analysis to confirm the complementation lines. dCAPS primer was used to amplify the PCR products of TOC132 from cad1-3, aic1 cad1-3, and the complementation lines. The PCR products were digested with HindIII.

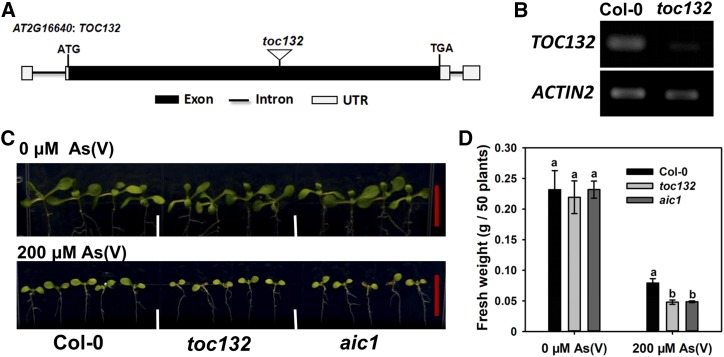

toc132 Is More Sensitive to As(V) than Col-0

The As(V) hypersensitivity phenotype was observed in the aic1 cad1-3 double mutant. To investigate if the toc132 single mutant also is more sensitive to As(V) than its wild type (Col-0), a mutant line with T-DNA insertion in the exon of TOC132 was obtained (Fig. 4A). The expression level of TOC132 in the toc132 T-DNA mutant was much lower than in Col-0, as revealed by semiquantitative PCR analysis, indicating that the gene expression was disturbed (Fig. 4B). An aic1 single mutant also was obtained from the F2 plants of the cross between aic1 cad1-3 and Col-0. The toc132 T-DNA line, aic1 single mutant, and Col-0 were grown on 1/2 MS agar medium containing 0 or 200 μm As(V) for 10 d. We used a higher As(V) concentration because these lines had functional PCS. In the absence of As(V), toc132 and aic1 showed no phenotypic difference from Col-0. In the presence of 200 μm As(V), both toc132 and aic1 were more chlorotic than Col-0, and their biomass was 39% lower than that of Col-0 (P < 0.05; Fig. 4, C and D). These results indicate that toc132 is more sensitive to As(V) than the wild type.

Figure 4.

Characterization of toc132 single mutants. A, Diagram of the T-DNA insertion mutant of the TOC132 gene. UTR, Untranslated Region. B, Semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of TOC132 expression in the T-DNA insertion mutant with ACTIN2 as a reference gene. C, Phenotypic comparison of Col-0, toc132, and aic1 grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 or 200 μm As(V) for 10 d. Bars (red) = 1 cm. D, Fresh weight of plants shown in C. Data are means ± se (n = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences within treatments (P < 0.05).

Analysis of the Chloroplast Proteome of aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3

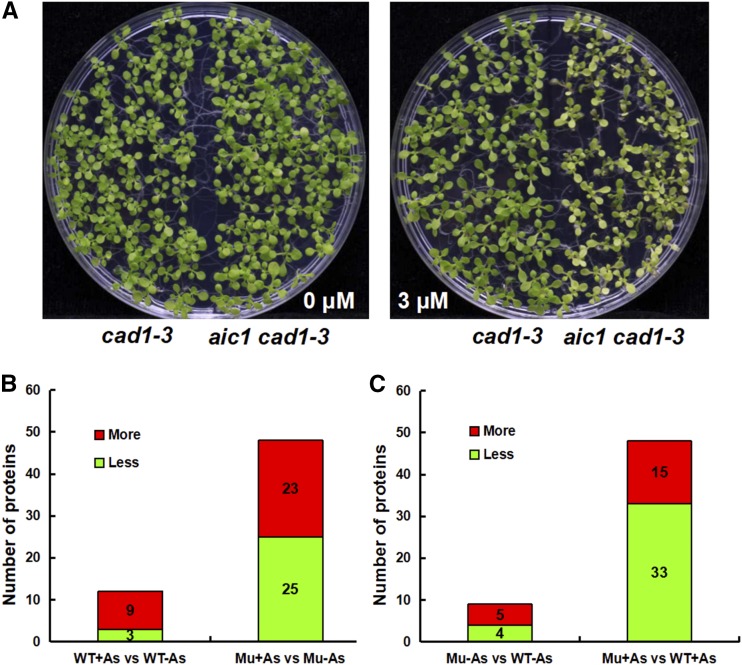

Because Toc132 functions in transporting preproteins synthesized in the cytosol to the chloroplast (Ivanova et al., 2004; Kubis et al., 2004), we analyzed the chloroplast proteome of aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 grown with or without As(V). No phenotypic difference between the two lines was observed in the control treatment without As(V). At 3 μm As(V), aic1 cad1-3 plants were more chlorotic than cad1-3 (Fig. 5A). Chloroplasts were isolated and the chloroplast proteome was determined by isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based analysis. A total of 657 proteins were identified with less than 1% false discovery rate, among which perturbations in the abundance of 322 proteins could be assessed confidently. By examining the subcellular localization of the identified proteins on the proteomic database (ThaleMine; https://apps.araport.org/thalemine), these proteins were located in the chloroplast, indicating no contamination by proteins from other organelles. We compared the abundances of the identified proteins between the two mutant lines or between As(V) treatments. Differences in both biological replicates of either greater than 1.3-fold (up-regulated) or less than 0.76-fold (down-regulated) were considered to represent differentially changed proteins.

Figure 5.

Phenotypes and profiling of chloroplast protein expression of cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3. A, Phenotypes of plants grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 or 3 μm As(V) for 15 d. B, Numbers of differentially expressed proteins within cad1-3 (WT) or aic1 cad1-3 (Mu) under 3 μm As(V) (+As) compared with the normal condition (−As). C, Numbers of differentially expressed proteins between cad1-3 (WT) and aic1 cad1-3 (Mu) under 0 (−As) or 3 μm As(V) (+As) condition.

Compared with the control [no As(V)], nine and three proteins were more and less abundant, respectively, in cad1-3 plants treated with As(V). By contrast, 23 and 25 proteins in aic1 cad1-3 were more and less abundant, respectively (Fig. 5B), indicating that the chloroplast proteome was more perturbed by As(V) in aic1 cad1-3 than in cad1-3. Comparisons between the two lines showed that five and 15 proteins had a higher abundance in aic1 cad1-3 than in cad1-3 under no As(V) and 3 μm As(V), respectively, whereas four and 33 proteins had a lower abundance under no As(V) and 3 μm As(V), respectively (Fig. 5C). The differentially changed proteins are divided into the following functional groups: chloroplast organization, photosynthesis, compound metabolisms, antioxidant related, and thioredoxin related, and are described in more detail below.

Effect of As(V) on the Chloroplast Proteome

When cad1-3 was exposed to As(V), five of the nine more abundant proteins were involved in photosynthesis, while the other four were involved in compound metabolism (Table 1). Among the four more abundant proteins involved in compound metabolism, AT1G10760 is an α-glucan water dikinase required for starch degradation (Mahlow et al., 2014); AT4G22240 encodes PLASTID-LIPID-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN2, which is induced under chloroplast stress conditions (Youssef et al., 2010); ATCG00670 is a proteolytic subunit of ATP-dependent caseinolytic protease (Clp) for removing short-lived proteins and damaged or misfolded polypeptides (Adam et al., 2001); while AT2G37690, an uncharacterized protein, is annotated as a phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase. Three proteins were less abundant in cad1-3 in response to As(V) treatment, among which two were photosynthesis-related proteins (Table 1). AT1G32060 catalyzes the final step in the regeneration of ribulose-l,5-bisphosphate and is regulated by the thioredoxin system (Horsnell and Raines, 1991). AT1G20020 is a chloroplast-targeted ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR2), which is involved in the redistribution of electrons (Lintala et al., 2009). The third down-regulated protein, Toc75-3, is classified into the chloroplast organization group. This protein forms the channel of the Toc complex and binds transit peptides directly (Hinnah et al., 1997, 2002).

Table 1. More and less abundant chloroplast proteins in cad1-3 in response to As(V) stress.

| Accession No. | Protein Name | Scorea | Percentage Coverageb | Unique Peptidesc | Mean of FCd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More abundant | |||||

| Photosynthesis | |||||

| ATCG00350 | Photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A1 | 7.75 | 2.67 | 2 | 3.14 |

| ATCG00020 | Photosystem II CP47 reaction center protein | 14.54 | 11.61 | 3 | 2.36 |

| ATCG00280 | Photosystem II CP43 reaction center protein | 21.98 | 9.51 | 4 | 1.66 |

| ATCG00540 | Cytochrome f | 19.80 | 25.00 | 6 | 1.40 |

| AT4G10340 | Chlorophyll a/b binding protein CP26 | 54.74 | 21.79 | 6 | 1.41 |

| Compound metabolisms | |||||

| AT1G10760 | α-Glucan water dikinase1 | 27.31 | 3.50 | 4 | 1.44 |

| AT2G37690 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase-like protein | 6.03 | 4.98 | 3 | 1.43 |

| AT4G22240 | Probable plastid-lipid-associated protein2 | 21.93 | 17.10 | 3 | 1.33 |

| ATCG00670 | ATP-dependent Clp proteolytic subunit 1 | 2.93 | 18.37 | 2 | 1.32 |

| Less abundant | |||||

| Chloroplast organization | |||||

| AT3G46740 | Protein Toc75-3 | 9.21 | 2.32 | 2 | 0.62 |

| Photosynthesis | |||||

| AT1G32060 | Phosphoribulokinase | 23.02 | 11.90 | 4 | 0.70 |

| AT1G20020 | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase, leaf isozyme2 | 5.84 | 15.45 | 3 | 0.59 |

The score of the protein calculated by the Proteome Discoverer Software.

The percentage of the protein sequence covered by identified peptides.

The number of unique peptides identified in each protein.

Mean value of the fold change (FC) between +As(V) and −As(V) treatments.

More proteins were altered in aic1 cad1-3 in response to As(V) treatment than in cad1-3 (Table 2). Among the 23 more abundant proteins, three proteins were involved in chloroplast organization, including Toc75-3, Tic110 (a chloroplast inner envelope translocon for preprotein import; Tsai et al., 2013), and SVR7, encoding a pentatricopeptide repeat protein for chloroplast biogenesis (Liu et al., 2010b; Zoschke et al., 2013). Two proteins (AT1G66430 and AT3G54090) were involved in photosynthesis (Keurentjes et al., 2008; Gilkerson et al., 2012). Two proteins (AT2G43090 and AT1G17745) were involved in the biosynthesis of Leu and Ser (Toujani et al., 2013; Imhof et al., 2014). Three proteins (AT1G32900, AT5G03650, and AT1G69830) were reported to have functions in the starch metabolic pathway (Dumez et al., 2006; Glaring et al., 2011; Szydlowski et al., 2011). In the group of antioxidant proteins up-regulated by As(V), AT4G23100 encodes the rate-limiting Glu-Cys ligase for catalyzing glutathione biosynthesis and AT3G45140 encodes lipoxygenase2, both of which are induced under stress conditions (Ball et al., 2004; Vanhoudt et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2014). AT5G20720 encodes the cochaperonin CHAPERONIN20, which enhances the activation of iron superoxide dismutase, an antioxidant enzyme, by direct interaction (Kuo et al., 2013). Among the 25 less abundant proteins in aic1 cad1-3 under As(V), four proteins were involved in chloroplast organization: AT4G30690 for chloroplast translation initiation factor 3 (Zheng et al., 2016), two subunits of 30S ribosomal protein (Tiller and Bock, 2014), and AT2G20890 for the formation of thylakoid membranes (Wang et al., 2004). Sixteen less abundant proteins were involved in photosynthesis, including light reactions and carbon assimilation (Table 2). Among these photosynthesis proteins, some play important functions for plant growth and development. For example, AT4G35250 is required for the translational initiation of psbA, which is a part of the PSII reaction center. The mutant of AT4G35250 is pale green and has retarded growth compared with the wild type (Link et al., 2012). AT5G47840, encoding AMP kinase, catalyzes the reversible formation of ADP by transferring one Pi group from ATP to AMP. Mutation of AT5G47840 causes seedling bleaching and strongly retarded growth (Lange et al., 2008). AT3G54050 encodes chloroplast fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), a key enzyme of the Calvin-Benson pathway. Mutation in this gene has a marked effect on plant development (Rojas-González et al., 2015). AT1G32200 participates in lipid metabolism (Xu et al., 2006), while AT3G19480 and AT5G35630 are involved in Ser and Gln biosynthesis (Guiboileau et al., 2013; Toujani et al., 2013). Furthermore, two thioredoxin-related proteins, thioredoxin M1 and peroxiredoxin Q (Pulido et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013), also were down-regulated in aic1 cad1-3 under As(V) (Table 2).

Table 2. More and less abundant chloroplast proteins in aic1 cad1-3 in response to As(V) stress.

| Accession No. | Protein Name | Scorea | Percentage Coverageb | Unique Peptidesc | Mean of FCd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More abundant | |||||

| Chloroplast organization | |||||

| AT4G16390 | Pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein | 5.89 | 2.85 | 2 | 1.79 |

| AT3G46740 | Protein Toc75-3 | 9.21 | 2.32 | 2 | 1.45 |

| AT1G06950 | Protein Tic110 | 38.63 | 12.70 | 10 | 1.40 |

| Photosynthesis | |||||

| AT1G66430 | Fructokinase6 | 6.50 | 5.99 | 2 | 1.63 |

| AT3G54090 | Fructokinase-like1 | 2.70 | 4.67 | 2 | 1.55 |

| Compound metabolisms | |||||

| AT1G69830 | α-Amylase3 | 9.59 | 5.41 | 3 | 2.01 |

| AT1G22410 | Class II DAHP synthetase family protein | 10.97 | 6.26 | 2 | 1.87 |

| AT2G37690 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase-like protein | 6.03 | 4.98 | 3 | 1.76 |

| AT5G51110 | Rubisco assembly factor 2 | 12.29 | 17.10 | 2 | 1.75 |

| AT2G43090 | 3-Isopropylmalate dehydratase small subunit 3 | 11.80 | 24.30 | 4 | 1.63 |

| AT1G17745 | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase2 | 10.34 | 3.37 | 2 | 1.61 |

| AT4G33030 | UDP-sulfoquinovose synthase | 9.00 | 10.48 | 3 | 1.52 |

| AT3G48870 | Clp ATPase | 59.72 | 16.07 | 2 | 1.51 |

| AT3G22960 | Plastidial pyruvate kinase1 | 10.29 | 5.20 | 2 | 1.50 |

| AT5G46390 | Carboxyl-terminal-processing peptidase1 | 8.66 | 3.89 | 2 | 1.46 |

| AT5G03650 | 1,4-α-Glucan-branching enzyme2-2 | 6.45 | 2.73 | 2 | 1.44 |

| AT1G32900 | Granule-bound starch synthase1 | 2.11 | 5.41 | 2 | 1.42 |

| AT5G41670 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating2 | 6.43 | 5.54 | 2 | 1.38 |

| AT5G54770 | Thiamine thiazole synthase | 1.30 | 9.46 | 2 | 1.35 |

| AT3G58610 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 28.88 | 8.97 | 4 | 1.35 |

| Antioxidant related | |||||

| AT4G23100 | Glu-Cys ligase | 11.85 | 4.41 | 2 | 1.76 |

| AT3G45140 | Lipoxygenase2 | 11.57 | 7.03 | 6 | 1.60 |

| AT5G20720 | 20-kD chaperonin | 16.62 | 14.62 | 3 | 1.43 |

| Less abundant | |||||

| Chloroplast organization | |||||

| AT4G30690 | Chloroplast-localized prokaryotic type translation initiation factor 3 | 6.11 | 7.47 | 2 | 0.66 |

| ATCG00380 | 30S ribosomal protein S4 | 21.46 | 19.40 | 4 | 0.66 |

| AT5G14320 | 30S ribosomal protein S13 | 17.74 | 22.66 | 3 | 0.65 |

| AT2G20890 | Protein THYLAKOID FORMATION1 | 13.17 | 10.00 | 3 | 0.65 |

| Photosynthesis | |||||

| AT4G23890 | NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit S | 9.13 | 10.80 | 2 | 0.73 |

| AT3G54050 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | 31.61 | 16.79 | 5 | 0.72 |

| AT1G42970 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPB | 31.74 | 25.50 | 7 | 0.71 |

| AT5G64040 | Photosystem I reaction center subunit N | 9.07 | 23.98 | 4 | 0.68 |

| ATCG00490 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase large chain | 881.29 | 56.78 | 24 | 0.68 |

| AT5G47840 | Adenylate kinase2 | 9.42 | 12.01 | 3 | 0.67 |

| AT3G26650 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPA1 | 41.26 | 15.66 | 3 | 0.66 |

| AT1G08550 | Violaxanthin deepoxidase | 18.25 | 8.87 | 4 | 0.66 |

| AT4G37925 | NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit M | 5.26 | 11.98 | 2 | 0.64 |

| AT2G39470 | Photosynthetic NDH subunit of lumenal location1 | 10.82 | 7.98 | 2 | 0.62 |

| AT1G20020 | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase, leaf isozyme2 | 5.84 | 15.45 | 3 | 0.62 |

| AT4G35250 | High-chlorophyll fluorescence phenotype 244 | 16.55 | 13.16 | 4 | 0.61 |

| AT5G38420 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain 2B | 183.18 | 54.14 | 2 | 0.54 |

| AT5G45680 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase FKBP13 | 4.39 | 8.65 | 2 | 0.51 |

| AT3G09580 | FAD/NAD(P)-binding oxidoreductase family protein | 4.25 | 3.77 | 2 | 0.45 |

| AT1G70820 | Phosphoglucomutase | 26.19 | 8.78 | 6 | 0.43 |

| Compound metabolisms | |||||

| AT1G32200 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | 1.10 | 5.45 | 2 | 0.75 |

| AT3G19480 | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase3 | 11.78 | 7.65 | 3 | 0.68 |

| AT5G35630 | Gln synthetase | 75.19 | 20.70 | 7 | 0.58 |

| Thioredoxin related | |||||

| AT1G03680 | Thioredoxin m1 | 15.62 | 15.64 | 2 | 0.62 |

| AT3G26060 | Peroxiredoxin Q | 5.91 | 20.37 | 3 | 0.60 |

The score of the protein calculated by the Proteome Discoverer Software.

The percentage of the protein sequence covered by identified peptides.

The number of unique peptides identified in each protein.

Mean value of the fold change (FC) between +As(V) and −As(V) treatments.

Between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3, only two proteins showed the same response to As(V). AT2G37690, which is involved in purine biosynthesis, was more abundant in both lines, whereas AT1G20020 (ferredoxin-NADP reductase, leaf isozyme2) was less abundant in both lines (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, Toc75-3 was less abundant in cad1-3 but more abundant in aic1 cad1-3.

Comparisons between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 in the Chloroplast Proteome

When As(V) was absent, five proteins were more abundant in aic1 acd1-3 than in cad1-3. Among these proteins, three were involved in photosynthesis, one functioning in starch synthesis and degradation (Uematsu et al., 2012) and one as an antioxidant for catalyzing the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen (Mhamdi et al., 2010; Table 3). By contrast, four proteins were less abundant in aic1 acd1-3 than in cad1-3, including one chloroplast organization-related protein, two photosynthesis proteins, and one involved in compound metabolism (Table 3).

Table 3. Chloroplast proteins showing differential abundance between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 in the absence of As(V) stress.

| Accession No. | Protein Name | Scorea | Percentage Coverageb | Unique Peptidesc | Mean of FCd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More abundant | |||||

| Photosynthesis | |||||

| ATCG00350 | Photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A1 | 7.75 | 2.67 | 2 | 2.10 |

| AT4G10340 | Chlorophyll a/b binding protein CP26 | 54.74 | 21.79 | 6 | 1.44 |

| AT4G35250 | High-chlorophyll fluorescence phenotype 244 | 16.55 | 13.16 | 4 | 1.31 |

| Compound metabolisms | |||||

| AT5G51820 | Phosphoglucomutase | 6.95 | 3.53 | 3 | 1.46 |

| Antioxidant related | |||||

| AT1G20620 | Catalase3 | 8.04 | 8.22 | 3 | 1.31 |

| Less abundant | |||||

| Chloroplast organization | |||||

| ATCG00780 | 50S ribosomal protein L14, chloroplastic | 3.56 | 21.31 | 2 | 0.70 |

| Photosynthesis | |||||

| AT1G20020 | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase, leaf isozyme2 | 5.84 | 15.45 | 3 | 0.72 |

| AT1G58290 | Glutamyl-tRNA reductase1 | 7.15 | 4.79 | 2 | 0.66 |

| Compound metabolisms | |||||

| AT1G69830 | α-Amylase3 | 9.59 | 5.41 | 3 | 0.75 |

The score of the protein calculated by the Proteome Discoverer Software.

The percentage of the protein sequence covered by identified peptides.

The number of unique peptides identified in each protein.

Mean value of the fold change (FC) between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3.

In the presence of As(V), more chloroplast proteins were differentially expressed between aic1 acd1-3 and cad1-3 (Table 4). Most of these proteins also were up- or down-regulated in aic1 cad1-3 under As(V), suggesting their possible involvement in the response to As(V) stress. Both Tic110 and Toc75-3 were more abundant in aic1 cad1-3 than in cad1-3. Two proteins involved in carotenoid and chlorophyll biosynthesis (AT4G14210 and AT3G48730), two proteins involved in sulfate metabolism (AT5G04590 and AT4G33030), and two antioxidant-related proteins (catalase3 and lipoxygenase2; Mhamdi et al., 2010; Vanhoudt et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2014) also were more abundant in aic1 cad1-3 than in cad1-3 (Table 4).

Table 4. Chloroplast proteins showing differential abundance between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 in the presence of As(V) stress.

| Accession No. | Protein Name | Scorea | Percentage Coverageb | Unique Peptidesc | Mean of FCd | Overlape |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More abundant | ||||||

| Chloroplast organization | ||||||

| AT3G46740 | Protein Toc75-3 | 9.21 | 2.32 | 2 | 2.48 | (ii) |

| AT4G16390 | Pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein | 5.89 | 2.85 | 2 | 1.57 | (ii) |

| AT1G06950 | Protein Tic110 | 38.63 | 12.70 | 10 | 1.49 | (ii) |

| Photosynthesis | ||||||

| AT1G22410 | Class-II DAHP synthetase family protein | 10.97 | 6.26 | 2 | 1.8 | (ii) |

| AT3G54090 | Fructokinase-like1 | 2.70 | 4.67 | 2 | 1.57 | (ii) |

| AT3G48730 | Glutamate-1-semialdehyde2,1-aminomutase2 | 14.17 | 5.51 | 2 | 1.51 | |

| AT4G14210 | Phytoene desaturase3 | 3.19 | 3.53 | 2 | 1.35 | |

| Compound metabolisms | ||||||

| AT3G48870 | Clp ATPase | 59.72 | 16.07 | 2 | 1.97 | (ii) |

| AT1G17745 | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase2 | 10.34 | 3.37 | 2 | 1.55 | (ii) |

| AT4G33030 | UDP-sulfoquinovose synthase | 9.00 | 10.48 | 3 | 1.48 | (ii) |

| AT2G37690 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase-like protein | 6.03 | 4.98 | 3 | 1.43 | (ii, iii) |

| AT3G23940 | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | 8.87 | 4.44 | 2 | 1.39 | |

| AT5G04590 | Sulfite reductase | 8.08 | 2.96 | 2 | 1.31 | |

| Antioxidant related | ||||||

| AT3G45140 | Lipoxygenase2 | 11.57 | 7.03 | 6 | 1.8 | (ii) |

| AT1G20620 | Catalase3 | 8.04 | 8.22 | 3 | 1.76 | (i) |

| Less abundant | ||||||

| Chloroplast organization | ||||||

| AT1G09340 | Chloroplast stem-loop binding protein of 41 kD b | 20.15 | 17.99 | 6 | 0.74 | |

| AT4G30690 | Chloroplast-localized prokaryotic type translation initiation factor 3 | 6.11 | 7.47 | 2 | 0.72 | (iv) |

| ATCG00380 | 30S ribosomal protein S4 | 21.46 | 19.40 | 4 | 0.6 | (iv) |

| AT5G14320 | 30S ribosomal protein S13 | 17.74 | 22.66 | 3 | 0.64 | (iv) |

| ATCG01120 | 30S ribosomal protein S15 | 5.25 | 12.50 | 2 | 0.65 | |

| AT2G43030 | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | 11.46 | 8.86 | 2 | 0.64 | |

| AT4G01310 | 50S ribosomal protein L5 | 19.59 | 12.60 | 3 | 0.66 | |

| AT3G44890 | 50S ribosomal protein L9 | 13.19 | 8.12 | 2 | 0.61 | |

| AT3G25920 | 50S ribosomal protein L15 | 24.59 | 16.97 | 4 | 0.69 | |

| AT5G47190 | 50S ribosomal protein L19 | 2.51 | 9.61 | 2 | 0.67 | |

| ATCG00810 | 50S ribosomal protein L22 | 1.21 | 9.38 | 2 | 0.63 | |

| AT2G20890f | Protein THYLAKOID FORMATION1 | 13.17 | 10.00 | 3 | 0.69 | (iv) |

| Photosynthesis | ||||||

| AT5G47840f | Adenylate kinase2 | 9.42 | 12.01 | 3 | 0.72 | (iv) |

| AT3G55800 | Sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase | 47.30 | 24.17 | 9 | 0.71 | |

| AT3G26650 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPA1 | 41.26 | 15.66 | 3 | 0.71 | (iv) |

| AT4G23890 | NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit S | 9.13 | 10.80 | 2 | 0.7 | (iv) |

| AT3G09580 | FAD/NAD(P)-binding oxidoreductase family protein | 4.25 | 3.77 | 2 | 0.69 | (iv) |

| AT4G21280 | Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein3-1 | 55.13 | 32.14 | 7 | 0.66 | |

| AT5G64040 | Photosystem I reaction center subunit N | 9.07 | 23.98 | 4 | 0.65 | (iv) |

| AT1G42970 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPB | 31.74 | 25.50 | 7 | 0.55 | (iv) |

| AT5G45680 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase FKBP13 | 4.39 | 8.65 | 2 | 0.54 | (iv) |

| AT1G70820 | Phosphoglucomutase | 26.19 | 8.78 | 6 | 0.46 | (iv) |

| ATCG00490 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase large chain | 881.29 | 56.78 | 24 | 0.56 | (iv) |

| AT1G67090 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain 1A | 189.97 | 46.11 | 4 | 0.6 | |

| AT5G38420 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain 2B | 183.18 | 54.14 | 2 | 0.45 | (iv) |

| Compound metabolism | ||||||

| AT1G80380f | d-Glycerate 3-kinase | 12.73 | 13.46 | 4 | 0.74 | |

| AT1G10760 | α-Glucan water dikinase1 | 27.31 | 3.50 | 4 | 0.73 | |

| AT3G19480 | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase3 | 11.78 | 7.65 | 3 | 0.65 | (iv) |

| AT5G35630 | Glutamine synthetase | 75.19 | 20.70 | 7 | 0.61 | (iv) |

| At1G56190 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 16.56 | 16.05 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Thioredoxin related | ||||||

| AT2G41680f | NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductase C | 9.66 | 5.29 | 3 | 0.76 | |

| AT3G02730 | Thioredoxin f1 | 2.87 | 11.24 | 2 | 0.68 | |

| AT3G26060 | Peroxiredoxin Q | 5.91 | 20.37 | 3 | 0.49 | (iv) |

The score of the protein calculated by the Proteome Discoverer Software.

The percentage of the protein sequence covered by identified peptides.

The number of unique peptides identified in each protein.

Mean value of the fold change (FC) between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3.

Overlap with other comparisons: (i) more abundant in aic1 cad1-3 than in cad1-3 without As(V); (ii) more abundant in aic1 cad1-3 with As(V); (iii) more abundant in cad1-3 with As(V); (iv) less abundant in aic1 cad1-3 with As(V).

Mutants of the genes encoding these proteins reported to exhibit chlorotic phenotypes in previous studies.

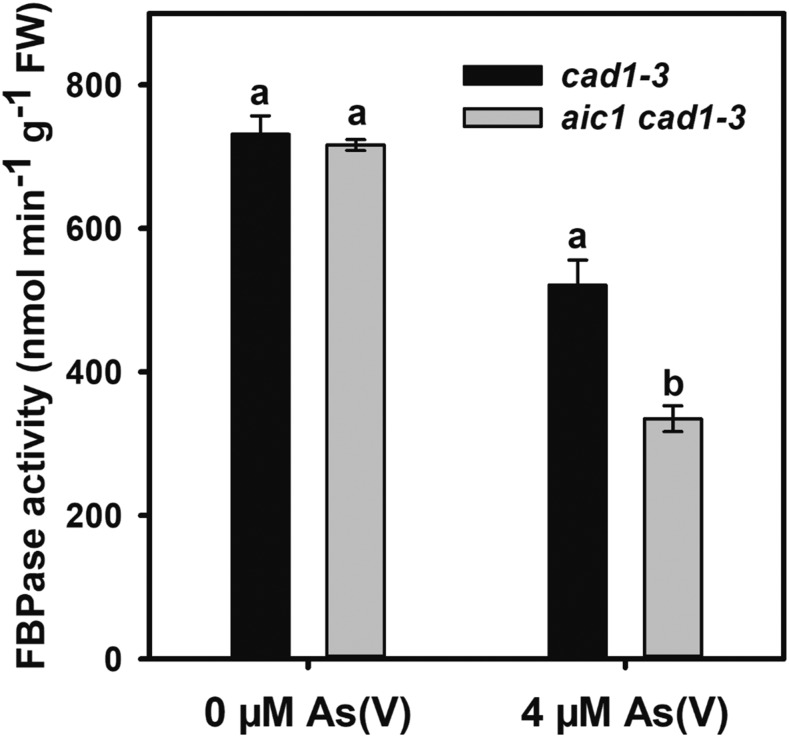

Among the 33 less abundant proteins in aic1 cad1-3 (Table 4), 12 were involved in chloroplast organization, including RNA binding, translation initiation factor proteins, chloroplast ribosome proteins, and thylakoid formation protein (Wang et al., 2004; Bollenbach et al., 2009; Tiller and Bock, 2014; Zheng et al., 2016). Thirteen proteins were involved in photosynthesis, including eight proteins related to light reactions and five related to carbon assimilation. Five proteins in the compound metabolism group were less abundant in aic1 cad1-3, including two involved in the biosynthesis of Gln and l-Ser and three proteins participating in the photorespiration C2 cycle, starch degradation, and glycolytic process. Three thioredoxin-related proteins also had lower abundance, including two thioredoxin proteins (NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductase C [NTRC] and thioredoxin f1 [TRX f1]) and peroxiredoxin Q. TRX f proteins are known to be involved in the light activation of AGPase and starch accumulation, with trx f1f2 double mutants showing growth inhibition under a short-day photoperiod (Naranjo et al., 2016). NTRC affects the tetrapyrrole synthesis pathway, starch synthesis, and the detoxification of peroxides (Nikkanen et al., 2017). ntrc mutants show decreased growth and abnormal chloroplast ultrastructure (Thormählen et al., 2015; Nikkanen et al., 2016). The trxf1 ntrc double mutant shows severe growth inhibition, with strong impairments of Calvin-Benson cycle activity and starch accumulation (Thormählen et al., 2015). Because FBPase is involved in the Calvin-Benson cycle activity and starch accumulation is activated by thioredoxins and NTRC proteins (Ojeda et al., 2017), we determined the activity of FBPase in aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 plants. The activity of FBPase was similar in the two lines without As(V) treatment. However, As(V) treatment decreased the FBPase activity in aic1 cad1-3 more severely than in cad1-3 (Fig. 6). These results suggest that the decreased abundance of thioredoxins and NTRC proteins in aic1 cad1-3 might result in lower FBPase activity and, consequently, decreased Calvin-Benson cycle activity.

Figure 6.

FBPase activity in cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3. Plants were grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 or 4 μm As(V) for 10 d. Data are means ± se (n = 3 biological replicates). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences within treatments (P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight.

DISCUSSION

Chloroplasts Are a Sensitive Target of As Toxicity

The growth of the aboveground tissues (shoots) of Arabidopsis appears to be more sensitive to As(V) toxicity than root growth. Shoot biomass of cad1-3 was decreased 51% by the 8 μm As(V) treatment, compared with only 26% inhibition in root length (Fig. 1, B and D). Similarly, shoot growth of Col-0 was suppressed by As(V) more than root growth (Chao et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015). In the study by Tang et al. (2015), the effective concentrations of As(V) causing 50% inhibition of shoot biomass and root growth of Col-0 were 90 and 200 μm, respectively. A common symptom of As(V) toxicity is leaf chlorosis (Jain and Gadre, 1997; Srivastava et al., 2017). Chlorophyll content and the number and size of chloroplasts were all decreased considerably by As(V) treatment (Figs. 1A and 2, C and D). Similar symptoms also have been reported in the aquatic plant Ceratophyllum demersum and the alga Nostoc muscorum (Mishra et al., 2016; Patel et al., 2018). The chlorophyll concentration of C. demersum was decreased significantly by As(V) (Mishra et al., 2016). In N. muscorum, pigment contents and PSII photochemistry were reduced by As treatments (Patel et al., 2018). These observations indicate that chloroplasts are a sensitive target of As toxicity. In this study, As was detectable in the isolated intact chloroplasts with concentrations similar to those of Mn (Fig. 2B), suggesting that As can enter the chloroplasts relatively easily. As speciation inside chloroplasts was not determined, but As(III) is likely to be the main As species, because As(V) is reduced readily to As(III) inside plant cells and most As in the shoots of As(V)-treated Arabidopsis is in the form of As(III) (Chao et al., 2014). Exposure to As(III) in the growth medium also induced leaf chlorosis (Supplemental Fig. S1). Because As(III) has a high affinity for thiol groups of proteins, it may poison the chloroplast by inactivating proteins inside this organelle.

In our study, we found that the abundances of some chloroplast proteins in cad1-3 were affected by As(V) stress (Table 1). Particularly, the abundance of a ferredoxin-NADP reductase (AT1G20020) was decreased by more than 40%. Mutation of this gene results in lower chlorophyll content and lower biomass (Lintala et al., 2009). In contrast, the abundances of some stress-induced proteins were enhanced by As(V). For example, two proteins involved in the ATP-dependent Clp for removing damaged polypeptides and responsible for chloroplast stress (Adam et al., 2001; Youssef et al., 2010) were up-regulated, suggesting increased stress-induced damages in the chloroplast. Surprisingly, several proteins related to photosynthesis and amino acid biosynthesis also were up-regulated. The reasons for these changes are not clear but may result from the reactions for coping with stress or the imbalance of internal metabolism.

Toc132 Is Involved in the Alleviation of As Toxicity in the Chloroplasts

It is well established that the synthesis of PCs in plant cells provides a key defense mechanism against As toxicity (Ha et al., 1999; Li et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2010a). To explore the As defense mechanisms beyond PC synthesis, we identified the Arabidopsis aic1 mutant in the cad1-3 background. The aic1 cad1-3 double mutant was more sensitive to both As(V) and As(III) than cad1-3 but not to the other heavy metals tested (Supplemental Fig. S1). The double mutant showed decreased chlorophyll content and reduced number of chloroplasts under As(V) stress than cad1-3 (Figs. 1C and 2D). The structure of chloroplasts was severely distorted in the double mutant (Fig. 2C). The aic1 single mutant also was more sensitive to As(V) than Col-0, albeit at a much higher As(V) concentration due to the presence of the PC defense mechanism (Fig. 4C). These mutant phenotypes further support the notion that chloroplasts are a key target of As toxicity. The increased As(V) sensitivity in the double mutant was not caused by altered uptake of As or translocation, as the total As concentrations in both roots and shoots did not differ significantly between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 (Fig. 2A). There also was no significant difference in the total As content in the chloroplasts based on the same number of chloroplasts (Fig. 2B). However, the concentration of As inside the chloroplasts could be higher in the double mutant due to the smaller size of chloroplasts.

Using genomic resequencing mapping and a complementation test, we identified TOC132 as the causal gene for the aic1 mutant (Fig. 3). Further evidence for TOC132 as the mutant gene was provided by the same phenotype of As(V)-induced chlorosis in a T-DNA insertion toc132 mutant and the aic1 single mutant (Fig. 4). TOC132 encodes a translocon located at the outer envelope membrane of chloroplasts. Toc132 is a minor isoform of the Toc159 family of GTPase-regulated receptors functioning in the recognition of preproteins and translocation motoring (Kubis et al., 2004). Toc132/Toc120 forms a complex with Toc34 (GTPase-regulated receptor) and Toc75 (protein-conducting channel), which is involved in the import of nonphotosynthetic, housekeeping preproteins from the cytosol to the chloroplast (Constan et al., 2004; Kubis et al., 2004; Jarvis, 2008; Ling and Jarvis, 2015), whereas the major isoform Toc159 forms a complex with Toc33 and Toc75 for the import of highly abundant, photosynthetic preproteins (Jarvis et al., 1998; Bauer et al., 2000; Jarvis, 2008; Ling and Jarvis, 2015). These membrane proteins are part of the machinery for the import of more than 90% of the approximately 3,000 chloroplast proteins that are encoded in the nucleus and synthesized in the cytoplasm (Leister, 2003). Previously, toc132 mutants showed a slightly pale phenotype in young plants and a yellow-green, somewhat reticulate phenotype in mature plants when grown in normal soil medium (Kubis et al., 2004). Using a forward genetics approach, we showed that Toc132 is involved in the alleviation of As toxicity to the chloroplasts. The fact that both toc132 and aic1 single mutants were more sensitive to As(V) than Col-0 indicates that its role in protecting chloroplasts from As toxicity is required regardless of whether the PC detoxification mechanism is present or not, the only difference being the level of As(V) exposure.

Proteomic analysis provided evidence that the chloroplast proteome of aic1 cad1-3 was more perturbed by As(V) stress than that of cad1-3 (Fig. 5B; Table 2). Because the chloroplast proteome of Col-0 was not determined, the effect of the cad1-3 mutation remains unknown. The As(V)-induced perturbation appears to be complex, with some proteins showing decreases while others show increases in abundance. A decreased abundance in the double mutant presumably could be explained by the impairment in the import of preproteins into the chloroplast. Chlorotic phenotypes have been observed in mutants of several genes encoding chloroplast proteins that showed a lower abundance in the double mutant in our study (e.g. AT2G20890, AT5G47840, AT1G80380, and AT2G41680 in Table 4). By contrast, an increased abundance in the double mutant could be due to up-regulation of the compensatory import pathway. Up-regulation of Toc75-3, the key channel protein associated with both Toc159 and Toc132/Toc120 import pathways, hints at this compensatory effect. Ling et al. (2012) reported that Toc75-III (Toc75-3) could partially complement the function of Toc33. Therefore, we speculate that some of the more abundant proteins in aic1 cad1-3 might result from the increased abundance of Toc75 and Tic110 proteins. It is possible that the As(V) hypersensitive phenotype of aic1 cad1-3 results from the combined effect of multiple changes in chloroplast proteins, as described below.

Nine chloroplast ribosome proteins showed lower abundances in aic1 cad1-3 than cad1-3 under As(V) stress. Chloroplast 70S-type ribosomes are responsible for the translation of chloroplast-encoded proteins and consist of two multicomponent subunits, the large (50S) and the small (30S) ribosomal subunits. The 50S complex contains 33 ribosomal proteins (L1–L6, L9–L24, L27–L29, L31–L36, PSRP5, and PSRP6) and three rRNAs, the 23S, 5S, and 4.5S rRNAs (Yamaguchi and Subramanian, 2000). The 30S particle comprises a total of 24 proteins (S1–S21, PSPR2, PSRP3, and PSRP4) and a single rRNA molecule, the 16S rRNA (Yamaguchi et al., 2000). Chloroplast ribosomes are responsible for the synthesis of subunits of PSI, PSII, ATPase, and the large subunit of Rubisco (Ridley et al., 1967). In our proteomic results, one 50S ribosome protein (L14) was less abundant in the double mutant than in cad1-3 under normal conditions. Additionally, both 30S (S4, S13, and S15) and 50S (L3, L5, L9, L15, L19, and L22) ribosome proteins were less abundant in the double mutant than cad1-3 under As(V) treatment. These results suggest that TOC132 may be involved in importing ribosome preproteins, especially under As(V) stress conditions. The decreased abundances of some chloroplast coding proteins (e.g. ATCG00380, ATCG01120, ATCG00810, and ATCG00490) also indicate that the function of ribosomes is compromised in aic1 cad1-3, which may be one of the reasons for increased As(V) sensitivity.

Several chloroplast proteins involved in the light and dark reactions of photosynthesis (e.g. Rubisco: ATCG00490, AT1G67090, and AT5G38420) showed decreased abundance in aic1 cad1-3 under As(V) stress compared with cad1-3. These changes are likely to affect photosynthesis more severely in the double mutant, contributing to the As(V) sensitivity phenotype.

Apart from photosynthesis, chloroplasts also have functions in nitrogen and sulfur assimilation and the synthesis of amino acids and other compounds (Joyard et al., 2010; Rolland et al., 2012). Changes in amino acid contents in response to As stress have been reported in rice and spinach (Spinacia oleracea; Dwivedi et al., 2010; Pavlík et al., 2010). In our study, more severe decreases in the abundance of proteins involved in amino acid synthesis (e.g. Gln and Ser) were found in aic1 cad1-3 under As(V) stress than in cad1-3, which may have an effect on plant growth and oxidative stress resistance.

Three thioredoxin-related proteins showed decreased abundance in the double mutant under As(V) stress compared with cad1-3. Thioredoxins are proteins that control the structure and function of cellular proteins by reducing disulfide bridges in redox-regulated enzymes (Gelhaye et al., 2005; Gütle et al., 2017). Thiol-based redox regulation is an important mechanism for controlling chloroplast proteins involved in biogenesis, regulating light energy collection and distribution, photosynthetic carbon fixation and other biosynthetic pathways, and plant stress responses (Nikkanen and Rintamäki, 2014; Nikkanen et al., 2016, 2017; Geigenberger et al., 2017). There are two thioredoxin systems in plant chloroplasts, the ferredoxin-thioredoxin system and the NTRC system. Among these thioredoxin proteins, TRX f1-2, m1-4, x, y1-2, and NTRC are located inside the chloroplast (Gelhaye et al., 2005). Wang et al. (2007) analyzed the interactions between As and thioredoxins from humans and Escherichia coli using mass spectrometry. They found that As(III) could bind thioredoxin proteins from humans but not E. coli, because thioredoxin from E. coli has only two Cys residues while binding of As(III) requires three Cys residues. In contrast, thioredoxin from humans has five Cys residues, which provide enough ligands for binding As(III) (Wang et al., 2007). The Arabidopsis thioredoxin proteins contain three to seven Cys residues, including two nearby Cys residues in the conserved CGPC motif (Supplemental Fig. S3). Therefore, some Arabidopsis thioredoxin proteins are likely targets for As(III) to bind and inactivate. Decreased abundance of thioredoxins in the double mutant would make these proteins more vulnerable to As(III) binding. The decreased FBPase activity under As(V) stress, especially in the double mutant (Fig. 6), was possibly caused by the perturbation of thioredoxin proteins.

In conclusion, this study shows that chloroplasts are sensitive to As toxicity and that Toc132 plays a role in alleviating As toxicity by importing some preproteins into the chloroplasts that are important in defending against As toxicity. Decreased abundances of these proteins inside the chloroplasts coupled with inactivation by the binding of As(III) likely explain the As hypersensitivity in the aic1/toc132 mutants. Thus, our study provides new insights into the defense mechanism against As toxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, and Mutant Screening

An ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized library in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) was established in the cad1-3 background, which is a mutant of the PCS (At5G44070; Ha et al., 1999). Seeds were surface sterilized with 8% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite for 10 min and washed using sterilized deionized water four times. The seeds were stratified for 2 d at 4°C before sowing on the plates. M2 seeds were germinated and grown on 1/2 MS agar (1% w/v) medium amended with 2 μm As(V) for 10 d. Mutants with yellow leaves were selected and transferred to 1/2 MS agar (1% w/v) medium without As(V) for 1 week. Plants that recovered the normal phenotype were selected and grown in soil for the collection of M3 seeds. The phenotypes of mutants were confirmed using M3 seeds. The mutants that grew normally without As(V) but showed leaf chlorosis under 2 μm As(V) were selected. These mutants were named aic. In this study, aic1 was characterized. Plants were grown in a growth chamber at 22°C with a 14-h/10-h light/dark regime.

Cloning and Complementation of AIC1

To clone the mutant gene, F2 progeny were generated from a cross between aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3. Next, 285 F2 plants were grown in 1/2 MS agar medium amended with 2 μm As(V), and 64 plants showing the chlorotic phenotype were selected for DNA extraction. Equal amounts of the extracted DNAs were mixed and sequenced using cad1-3 plants as the control. The sequences of aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 were compared using the MutMap method (Abe et al., 2012) to identify candidate genes. To confirm the candidate genes, dCAPS markers were developed based on the dCAPS Finder 2.0 program Web site (http://helix.wustl.edu/dcaps). The PCR products were amplified and digested with restriction endonucleases. The 64 F2 plants exhibiting chlorosis under As(V) treatment were used for mutation linkage analysis using the dCAPS markers. TOC132 (At2G16640) was confirmed as the causal gene. After the mutant gene was confirmed, the aic1 cad1-3 mutant was backcrossed to Col-0 to generate the single aic1 mutant in the Col-0 background.

For complementation of the aic1 mutant, the genomic DNA fragment harboring the 2-kb promoter, the genomic sequence, and 1 kb downstream of the stop codon of AIC1 (TOC132) was amplified and constructed into a complementation vector (pZH2B; Gao et al., 2018). The final vector was transformed into aic1 cad1-3 using Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain EHA105)-mediated transformation by floral dip (Clough and Bent, 1998). T3 homozygous plants harboring the transgene were used in phenotype assays. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

To further confirm the causal gene for aic1, we obtained a T-DNA insertional mutant of TOC132 (toc132; CS330404) from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (http://arabidopsis.info/). The primers used to identify homozygous individuals are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Gene Expression Analysis

cad1-3 plants were grown on 1/2 MS agar (1% w/v) medium with or without 10 μm As(V). After 10 d, total RNA was extracted from whole plants using the RNA Extraction Kit (BioTeke) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using the HiScript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme). Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted using the SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Vazyme) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time system. The relative expression of TOC132 was normalized to the expression level at control without treatment. UBIQUITIN10 and ACTIN2 were used as the internal reference genes for RT-qPCR. ACTIN2 was used as the internal control for semiquantitative RT-PCR in TOC132 expression analysis of the TOC132 T-DNA mutant and the wild type. The primers used for RT-qPCR and RT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Determination of Chlorophyll Content

Plants of Col-0, cad1-3, and aic1 cad1-3 were grown in 1/2 MS agar medium containing 0 to 8 μm As(V) for 10 d. The chlorophyll content was determined according to the method described by Petrillo et al. (2014) with modifications. Briefly, about 100 mg of leaf tissue was frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen. Then, 400 µL of 80% acetone buffered with water was added. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and the pellet was extracted four more times. A spectrophotometer (Shimadzu; UV-1800) was zeroed using 80% acetone at 750 nm. The extract was diluted, and the absorbance was measured at 470, 646.6, and 663.6 nm. The concentrations of chlorophyll a and b were calculated according to the equations described by Petrillo et al. (2014).

As Uptake and Elemental Concentrations in the Chloroplasts

Plants were grown hydroponically in one-fifth-strength Hoagland nutrient solution [1 mm KNO3, 1 mm Ca(NO3)2, 0.4 mm MgSO4, 0.2 mm NH4H2PO4, 3 μm H3BO3, 0.5 μm MnCl2, 1 μm (NH4)6Mo7O24, 0.4 μm ZnSO4, 0.2 μm CuSO4, and 20 μm Fe(III)-EDTA, pH 5.6] for 4 weeks and then exposed to 5 μm As(V) (Na3AsO4) for 3 d. Before harvest, plant roots were rinsed with deionized water for 10 min, and then roots and shoots were separated, washed with deionized water three times, and dried at 65°C for 3 d. To determine elemental concentrations in the chloroplasts, plants were grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 2 μm As(V) for 15 d. Chloroplasts were separated from leaves using a modified method as described below. The number of intact chloroplasts was counted using a microscope according to the method described by Ling and Jarvis (2016). The numbers of chloroplasts per unit of fresh weight of aic1 cad1-3 and cad1-3 were calculated. Aliquots of chloroplasts were digested for elemental analysis. Dry plant samples and chloroplasts were digested with HNO3:HClO4 (85:15, v/v; Zhao et al., 1994). The concentrations of total As and other elements were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Perkin-Elmer NexION-300x).

Chloroplast Structure by Transmission Electron Microscopy

Plants of cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3 were grown on 1/2 MS agar medium amended with 8 μm As(V) for 10 d. Leaves were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and vacuum infiltrated at 4°C. The samples were postfixed with 2% (w/v) osmium tetroxide for 2 h (Chen et al., 2007). The fixed samples were dehydrated using a graded series of ethanol and acetone. The specimens then were embedded in resin (Epon 812). Sections were cut and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate in sequence. The samples were observed using a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi; H-7650).

Chloroplast Proteomics

cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3 plants were grown on 1/2 MS agar medium amended with or without 3 μm As(V) for 15 d. Chloroplasts were isolated from leaves according to the method described by Ling and Jarvis (2016). Briefly, seedlings were homogenizd in an ice-cold isolation buffer containing 0.3 m sorbitol, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EGTA, 5 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaHCO3, and 20 mm HEPES with final pH 8 (with KOH). The homogenate was filtered through two layers of filtration cloth and centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended with the remaining residual supernatant. The homogenate was gently transferred onto the top of a continuous density gradient mixture prepared by mixing equal volumes of isolation buffer and Percoll and centrifuging the mixture at 43,000g for 30 min (brake off) at 4°C. Then, the content was centrifuged in a swinging-bucket rotor at 7,800g for 10 min at 4°C. The lower band containing intact chloroplasts was transferred with a Pasteur pipette into a fresh centrifuge tube containing HMS buffer (50 mm HEPES, 3 mm MgSO4, and 0.3 m sorbitol, pH 8, with NaOH). The tube was inverted twice to wash away the Percoll from the chloroplasts. The tube was centrifuged again at 1,000g for 5 min at 4°C. After the supernatant was removed, the chloroplast pellet was resuspended in the residual HMS buffer solution left in the tube by gently agitating the tube on ice. The yield and intactness of the chloroplasts were determined by microscope according to Ling and Jarvis (2016).

Total proteins were extracted from intact chloroplasts with the Plant Total Protein Extraction Kit (Sigma; PE0230) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay. Peptides were generated as described previously (Dai et al., 2017). Briefly, 200 μg of total proteins was reduced with DTT and then alkylated with iodoacetamide. The protein sample was buffer exchanged and digested with a sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega). Digested peptides were collected by centrifugation and quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Desalted peptides from different plants were differentially labeled using an iTRAQ 8-plex reagent kit (Sigma; 4381662-1KT) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two independent biological replicates per As treatment per line were extracted for chloroplast proteins and labeled by iTRAQ. The labeled peptides were combined and fractionated using high-resolution cation-exchange chromatography (PolySulfoethyl A, 5 mm, 200-Å bead).

Nano-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis was performed with an Ultimate 3000 RSLC nano system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer equipped with a nano-electrospray ion source (Dai et al., 2017). Each fraction was dissolved in 0.1% formate and centrifuged. A volume of 5 μL of the supernatant was loaded onto the trap column and then eluted on the analytical column by a gradient of eluent (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formate) from 3% to 42% at a flow rate of 300 nL min−1 over 70 min.

Raw peptide data were analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer Software (version 1.4; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Searches were conducted using the Sequest HT engine against the data in TAIR10 (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). The false discovery rate based on q value was estimated using the Percolator algorithm. Only peptides at the 99% confidence interval were counted as identified proteins. In addition, only proteins with at least two unique peptides were considered to be reliable and used for protein quantitation. Differences (fold changes) in protein quantities of the same line under different As(V) treatments or different lines under the same As(V) treatment were calculated. Proteins with fold change either greater than 1.3 or less than 0.76 in both biological replicates were considered to be significantly differentially expressed proteins.

Assay of FBPase Activity

cad1-3 and aic1 cad1-3 plants were grown on 1/2 MS agar (1%) medium with or without 4 μm As(V) for 10 d. Leaves were harvested for the assay of FBPase activity using the FBP Assay Kit (Solarbio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by comparisons of means using Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 20.0.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/TAIR databases with the following accession numbers: TOC132/AIC1, At2G16640; PCS1, At5G44070; UBIQUITIN10, At4G05320; and ACTIN2, At3G18780.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Tolerance phenotype of aic1 cad1-3 to As(III), Cd, and Cu.

Supplemental Figure S2. Relative expression level of TOC132 in response to As(V) treatment.

Supplemental Figure S3. Amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis thioredoxins.

Supplemental Table S1. Mutation linkage analysis using 64 F2 generation individuals.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Footnotes

The study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (31520103914), the Innovative Research Team Development Plan of the Ministry of Education of China (grant no. IRT_17R56), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. KYT201802).

Senior author.

References

- Abe A, Kosugi S, Yoshida K, Natsume S, Takagi H, Kanzaki H, Matsumura H, Yoshida K, Mitsuoka C, Tamiru M, et al. (2012) Genome sequencing reveals agronomically important loci in rice using MutMap. Nat Biotechnol 30: 174–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam Z, Adamska I, Nakabayashi K, Ostersetzer O, Haussuhl K, Manuell A, Zheng B, Vallon O, Rodermel SR, Shinozaki K, et al. (2001) Chloroplast and mitochondrial proteases in Arabidopsis: a proposed nomenclature. Plant Physiol 125: 1912–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer CD, Edwards JO, Rieger PH (1981) Kinetics of the hydrolysis of arsenate(V) triesters. Inorg Chem 20: 905–907 [Google Scholar]

- Ball L, Accotto GP, Bechtold U, Creissen G, Funck D, Jimenez A, Kular B, Leyland N, Mejia-Carranza J, Reynolds H, et al. (2004) Evidence for a direct link between glutathione biosynthesis and stress defense gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 2448–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J, Chen K, Hiltbunner A, Wehrli E, Eugster M, Schnell D, Kessler F (2000) The major protein import receptor of plastids is essential for chloroplast biogenesis. Nature 403: 203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert GP, Thorsen M, Schüssler MD, Nilsson HR, Wagner A, Tamás MJ, Jahn TP (2008) A subgroup of plant aquaporins facilitate the bi-directional diffusion of As(OH)3 and Sb(OH)3 across membranes. BMC Biol 6: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollenbach TJ, Sharwood RE, Gutierrez R, Lerbs-Mache S, Stern DB (2009) The RNA-binding proteins CSP41a and CSP41b may regulate transcription and translation of chloroplast-encoded RNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 69: 541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao DY, Chen Y, Chen J, Shi S, Chen Z, Wang C, Danku JM, Zhao FJ, Salt DE (2014) Genome-wide association mapping identifies a new arsenate reductase enzyme critical for limiting arsenic accumulation in plants. PLoS Biol 12: e1002009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Chi Y, Taylor NL, Lambers H, Finnegan PM (2010) Disruption of ptLPD1 or ptLPD2, genes that encode isoforms of the plastidial lipoamide dehydrogenase, confers arsenate hypersensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 153: 1385–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhang W, Xie Y, Lu W, Zhang R (2007) Comparative proteomics of thylakoid membrane from a chlorophyll b-less rice mutant and its wild type. Plant Sci 173: 397–407 [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Kim EJ, Neumann D, Schroeder JI (1999) Tolerance to toxic metals by a gene family of phytochelatin synthases from plants and yeast. EMBO J 18: 3325–3333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constan D, Patel R, Keegstra K, Jarvis P (2004) An outer envelope membrane component of the plastid protein import apparatus plays an essential role in Arabidopsis. Plant J 38: 93–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Cui W, Pan J, Xie Y, Wang J, Shen W (2017) Proteomic analysis provides insights into the molecular bases of hydrogen gas-induced cadmium resistance in Medicago sativa. J Proteomics 152: 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumez S, Wattebled F, Dauvillee D, Delvalle D, Planchot V, Ball SG, D’Hulst C (2006) Mutants of Arabidopsis lacking starch branching enzyme II substitute plastidial starch synthesis by cytoplasmic maltose accumulation. Plant Cell 18: 2694–2709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi S, Tripathi RD, Tripathi P, Kumar A, Dave R, Mishra S, Singh R, Sharma D, Rai UN, Chakrabarty D, et al. (2010) Arsenate exposure affects amino acids, mineral nutrient status and antioxidants in rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Environ Sci Technol 44: 9542–9549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan PM, Chen W (2012) Arsenic toxicity: the effects on plant metabolism. Front Physiol 3: 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Xie W, Yang C, Xu J, Li J, Wang H, Chen X, Huang CF (2018) NRAMP2, a trans-Golgi network-localized manganese transporter, is required for Arabidopsis root growth under manganese deficiency. New Phytol 217: 179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Thormählen I, Daloso DM, Fernie AR (2017) The unprecedented versatility of the plant thioredoxin system. Trends Plant Sci 22: 249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhaye E, Rouhier N, Navrot N, Jacquot JP (2005) The plant thioredoxin system. Cell Mol Life Sci 62: 24–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkerson J, Perez-Ruiz JM, Chory J, Callis J (2012) The plastid-localized pfkB-type carbohydrate kinases FRUCTOKINASE-LIKE 1 and 2 are essential for growth and development of Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol 12: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaring MA, Baumann MJ, Abou Hachem M, Nakai H, Nakai N, Santelia D, Sigurskjold BW, Zeeman SC, Blennow A, Svensson B (2011) Starch-binding domains in the CBM45 family: low-affinity domains from glucan, water dikinase and α-amylase involved in plastidial starch metabolism. FEBS J 278: 1175–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiboileau A, Avila-Ospina L, Yoshimoto K, Soulay F, Azzopardi M, Marmagne A, Lothier J, Masclaux-Daubresse C (2013) Physiological and metabolic consequences of autophagy deficiency for the management of nitrogen and protein resources in Arabidopsis leaves depending on nitrate availability. New Phytol 199: 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gütle DD, Roret T, Hecker A, Reski R, Jacquot JP (2017) Dithiol disulphide exchange in redox regulation of chloroplast enzymes in response to evolutionary and structural constraints. Plant Sci 255: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha SB, Smith AP, Howden R, Dietrich WM, Bugg S, O’Connell MJ, Goldsbrough PB, Cobbett CS (1999) Phytochelatin synthase genes from Arabidopsis and the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Plant Cell 11: 1153–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnah SC, Hill K, Wagner R, Schlicher T, Soll J (1997) Reconstitution of a chloroplast protein import channel. EMBO J 16: 7351–7360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnah SC, Wagner R, Sveshnikova N, Harrer R, Soll J (2002) The chloroplast protein import channel Toc75: pore properties and interaction with transit peptides. Biophys J 83: 899–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsnell PR, Raines CA (1991) Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA clone encoding chloroplast phosphoribulokinase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 17: 183–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhmann BL, Harvey CF, Uddin A, Choudhury I, Ahmed KM, Duxbury JM, Bostick BC, van Geen A (2017) Field study of rice yield diminished by soil arsenic in Bangladesh. Environ Sci Technol 51: 11553–11560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhof J, Huber F, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Wiegreffe C, Lächler K, Binder S (2014) The small subunit 1 of the Arabidopsis isopropylmalate isomerase is required for normal growth and development and the early stages of glucosinolate formation. PLoS ONE 9: e91071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (2004) Some Drinking-Water Disinfectants and Contaminants, Including Arsenic. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol 84 IARC, Vienna: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriel A, Dundas G, Fernández Cirelli A, Lagorio MG (2015) Effect of arsenic on reflectance spectra and chlorophyll fluorescence of aquatic plants. Chemosphere 119: 697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isayenkov SV, Maathuis FJM (2008) The Arabidopsis thaliana aquaglyceroporin AtNIP7;1 is a pathway for arsenite uptake. FEBS Lett 582: 1625–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova Y, Smith MD, Chen K, Schnell DJ (2004) Members of the Toc159 import receptor family represent distinct pathways for protein targeting to plastids. Mol Biol Cell 15: 3379–3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Gadre R (1997) Effect of As on chlorophyll and protein contents and enzymic activities in greening maize tissues. Water Air Soil Pollut 93: 109–115 [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis P. (2008) Targeting of nucleus-encoded proteins to chloroplasts in plants. New Phytol 179: 257–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis P, Chen LJ, Li H, Peto CA, Fankhauser C, Chory J (1998) An Arabidopsis mutant defective in the plastid general protein import apparatus. Science 282: 100–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyard J, Ferro M, Masselon C, Seigneurin-Berny D, Salvi D, Garin J, Rolland N (2010) Chloroplast proteomics highlights the subcellular compartmentation of lipid metabolism. Prog Lipid Res 49: 128–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya T, Tanaka M, Mitani N, Ma JF, Maeshima M, Fujiwara T (2009) NIP1;1, an aquaporin homolog, determines the arsenite sensitivity of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 284: 2114–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keurentjes JJ, Sulpice R, Gibon Y, Steinhauser MC, Fu J, Koornneef M, Stitt M, Vreugdenhil D (2008) Integrative analyses of genetic variation in enzyme activities of primary carbohydrate metabolism reveal distinct modes of regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol 9: R129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubis S, Patel R, Combe J, Bédard J, Kovacheva S, Lilley K, Biehl A, Leister D, Ríos G, Koncz C, et al. (2004) Functional specialization amongst the Arabidopsis Toc159 family of chloroplast protein import receptors. Plant Cell 16: 2059–2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WY, Huang CH, Liu AC, Cheng CP, Li SH, Chang WC, Weiss C, Azem A, Jinn TL (2013) CHAPERONIN 20 mediates iron superoxide dismutase (FeSOD) activity independent of its co-chaperonin role in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. New Phytol 197: 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange PR, Geserick C, Tischendorf G, Zrenner R (2008) Functions of chloroplastic adenylate kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 146: 492–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leister D. (2003) Chloroplast research in the genomic age. Trends Genet 19: 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Dankher OP, Carreira L, Smith AP, Meagher RB (2006) The shoot-specific expression of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase directs the long-distance transport of thiol-peptides to roots conferring tolerance to mercury and arsenic. Plant Physiol 141: 288–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Q, Jarvis P (2015) Functions of plastid protein import and the ubiquitin-proteasome system in plastid development. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 939–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Q, Jarvis P (2016) Analysis of protein import into chloroplasts isolated from stressed plants. J Vis Exp e54717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Q, Huang W, Baldwin A, Jarvis P (2012) Chloroplast biogenesis is regulated by direct action of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Science 338: 655–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link S, Engelmann K, Meierhoff K, Westhoff P (2012) The atypical short-chain dehydrogenases HCF173 and HCF244 are jointly involved in translational initiation of the psbA mRNA of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 160: 2202–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintala M, Allahverdiyeva Y, Kangasjärvi S, Lehtimäki N, Keränen M, Rintamäki E, Aro EM, Mulo P (2009) Comparative analysis of leaf-type ferredoxin-NADP oxidoreductase isoforms in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 57: 1103–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WJ, Wood BA, Raab A, McGrath SP, Zhao FJ, Feldmann J (2010a) Complexation of arsenite with phytochelatins reduces arsenite efflux and translocation from roots to shoots in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 152: 2211–2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Yu F, Rodermel S (2010b) An Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat protein, SUPPRESSOR OF VARIEGATION7, is required for FtsH-mediated chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Physiol 154: 1588–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Yamaji N, Mitani N, Xu XY, Su YH, McGrath SP, Zhao FJ (2008) Transporters of arsenite in rice and their role in arsenic accumulation in rice grain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 9931–9935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlow S, Hejazi M, Kuhnert F, Garz A, Brust H, Baumann O, Fettke J (2014) Phosphorylation of transitory starch by α-glucan, water dikinase during starch turnover affects the surface properties and morphology of starch granules. New Phytol 203: 495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meharg AA, Rahman MM (2003) Arsenic contamination of Bangladesh paddy field soils: implications for rice contribution to arsenic consumption. Environ Sci Technol 37: 229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meharg AA, Williams PN, Adomako E, Lawgali YY, Deacon C, Villada A, Cambell RCJ, Sun G, Zhu YG, Feldmann J, et al. (2009) Geographical variation in total and inorganic arsenic content of polished (white) rice. Environ Sci Technol 43: 1612–1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhamdi A, Queval G, Chaouch S, Vanderauwera S, Van Breusegem F, Noctor G (2010) Catalase function in plants: a focus on Arabidopsis mutants as stress-mimic models. J Exp Bot 61: 4197–4220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Stärk HJ, Küpper H (2014) A different sequence of events than previously reported leads to arsenic-induced damage in Ceratophyllum demersum L. Metallomics 6: 444–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Alfeld M, Sobotka R, Andresen E, Falkenberg G, Küpper H (2016) Analysis of sublethal arsenic toxicity to Ceratophyllum demersum: subcellular distribution of arsenic and inhibition of chlorophyll biosynthesis. J Exp Bot 67: 4639–4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo B, Diaz-Espejo A, Lindahl M, Cejudo FJ (2016) Type-f thioredoxins have a role in the short-term activation of carbon metabolism and their loss affects growth under short-day conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 67: 1951–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkanen L, Rintamäki E (2014) Thioredoxin-dependent regulatory networks in chloroplasts under fluctuating light conditions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369: 20130224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]