Abstract

Background and study aims Acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) due to peptic ulcer disease (PUD) remains a common and challenging emergency managed by gastroenterologists. The proper role of endoscopic suturing on the management of PUD-related UGIB is unknown.

Patients and methods This is an international case series of patients who underwent endoscopic suturing for bleeding PUD. Primary outcome was rate of immediate hemostasis and rate of early rebleeding (within 72 hours). Secondary outcomes included technical success, delayed rebleeding (> 72 hours), and rate of adverse events (AEs).

Results Ten patients (mean age 66.7 years, 30 % female) were included in this study. Nine (90 %) had prior failed endoscopy hemostasis with an average of 1.4 ± 0.7 (range 1 – 3) prior endoscopic sessions. Forrest classification was Ib in 5 (50 %), IIa in 3 (30 %), IIb in 1(10 %), and IIc in 1 (10 %). Mean suturing time was 13.4 ± 5.6 (range 3.5 to 20) minutes. Technical success was 100 %. Rate of immediate hemostasis was 100 % and rate of early rebleeding was 0 %. Mean number of sutures was 1.5 (range, 1 – 4). No AEs were observed. Delayed recurrent bleeding was not observed in any cases after a median of 11 months (range 2 – 56), after endoscopic suturing.

Conclusions Oversewing of a bleeding or high-risk ulcer using endoscopic suturing appears to be a safe and effective method for achieving endoscopic hemostasis. It may be considered as rescue endoscopic therapy when primary endoscopic hemostasis fails to control the bleeding or when hemorrhage recurs after successful control of bleeding.

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal bleed (UGIB) is the most common gastrointestinal-related reason for hospitalization 1 . Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is the most common cause of UGIB, accounting for 30 % to 60 % of cases 2 3 4 . Endoscopic therapy is effective at stopping initial bleeding and reducing rates of rebleeding, referral to surgery, and mortality 5 . A wide variety of conventional options for endoscopic management of bleeding PUD exist, including injection therapy used in combination with a second endoscopic modality, mechanical hemostasis with hemoclips, and thermocoagulation therapy (ie, heater probe or bipolar electrocoagulation 6 7 . These are generally considered relatively effective as first-line therapy for hemostasis, with rates of efficacy ranging from 54 % to 100 %, depending on the study and type of intervention used 6 8 .

However, persistent or recurrent bleeding of PUD remains a challenging clinical problem. Studies have demonstrated that after undergoing endoscopic therapy for peptic ulcer bleeding, the rate of rebleeding is up to 18 %, with mortality from rebleeding ranging from 7 % to 9 % 5 9 10 . Furthermore, patients with difficult-to-manage rebleeding may require emergent referral to interventional radiology or surgery, with all of the attendant risks of emergent proceduralization. Risk factors for rebleeding include severe anemia, shock, ulcer size and Forrest classification, physical status scores, and delayed therapy 5 9 10 . Finally, patients on anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapies pose a very high risk for bleeding complications of PUD 11 12 13 including potentially a higher risk of rebleeding 14 15 . Thus, new endoscopic interventions for hemostasis are needed, especially in patients who fail to respond to initial endoscopic therapy or who are at high risk for bleeding complications.

Endoscopic suturing is a technique that was initially developed to close defects of the wall of the gastrointestinal lumen, such as perforations, leaks, and fistulas. Due to its excellent ability to close large mucosal defects, the endoscopic suturing device has recently been described as a novel endoscopic modality for treatment of UGIB 16 . However, data on the efficacy and safety of endoscopic suturing for management of acute UGIB are lacking. Thus, the current study was undertaken to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of endoscopic suturing for hemostasis of PUD-related UGIB.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient population

We performed an international, retrospective study of prospectively collected data at three centers (2 United States, 1 Hong Kong) of all consecutive patients who underwent endoscopic suturing for non-variceal acute UGIB between January 2015 and November 2017. It should be noted that in these instances, the endoscopic suturing device is being used for an indication not currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained per local protocol at each center. Excluded cases include those in which suturing was performed for bleeding prophylaxis after endoscopic resection of a gastrointestinal tract lesion, or for post-surgical patients with an anastomotic ulcer.

Data collection

All endoscopists who were involved in the study kept a record of all procedures, and all suturing cases that met the above criteria, regardless of the results of the procedure, were included in the current study. The electronic medical record was examined to extract necessary data, including both the hospital record and the endoscopy reporting software. Such data include demographic information; baseline clinical information such as admission and nadir hemoglobin values; information on prior endoscopic procedures, including number of procedures and type of intervention(s); use of any antiplatelet and/or anticoagulation agents; and information on the index ulcer(s) that were sutured, including ulcer size, Forrest classification, ulcer location; and presence of carcinoma on gastric biopsy (if performed). In addition, data on the suturing procedure itself were recorded, including number of sutures used, time of procedure, any early or delayed adverse events (AEs), length of procedure, and technical success or failure of the procedure. Finally, post-procedure information including information on any follow-up endoscopy procedures, length of follow-up, and history of rebleeding after the suture procedure, were included as well. This study also included three patients that were previously published as a case series with updated follow-up outcomes data provided 16 .

Procedure

Endoscopic suturing of the peptic ulcer was performed ( Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 ), as previously described 16 . In brief, the suturing device (OverStitch; Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Texas, United States) was mounted on a therapeutic double-channel upper Olympus GIF-2TH180 endoscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, Pennsylvania, United States). A suture anchor with a detachable needle was passed through one accessory channel and connected to the suturing arm of the suturing device. The handle portion was attached to the endoscope. The scope preloaded with the endoscopic suturing system was inserted into the stomach. Full-thickness bites were taken at the normal mucosa through the gastric wall for each bite. A figure-of-eight suture pattern was used to oversew the ulcer with bites being taken approximately 5 mm away from the ulcer edge. After tightening the suture, a cinch was used to secure the deployed suture Video 1 . One or more 2 – 0 polypropylene suture(s) were used. The number of sutures placed was determined at the discretion of the performing endoscopist.

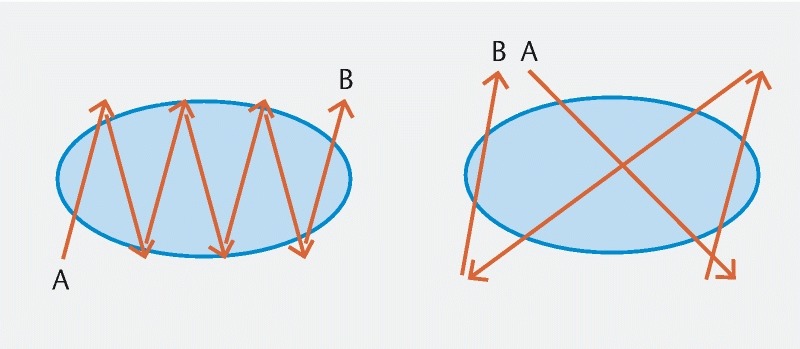

Fig. 1 .

Endoscopic suturing patterns. Running suture (left) and figure-of-eight suture (right).

Fig. 2 .

Endoscopic suturing of peptic ulcer. Endoscopic suturing procedure. a A 2-cm ulcer located in lesser curvature of gastric body prior to suture. b Use of endosuturing device. c After oversewing of the ulcer.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the technical success of the procedure, defined as successful deployment of one or more endoscopic sutures in the desired area. Secondary outcomes included early rebleeding, defined as bleeding within 72 hours after endoscopic suturing; delayed rebleeding, defined as bleeding between 72 hours and up to 30 days after treatment; the need for surgery or angio-embolization; and finally, the rate of AEs associated with the index procedure. AEs were defined based on previously established criteria by the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 17 .

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel (Version 2011, Redmond, Washington, United States). Descriptive statistics for the study population as well as the outcomes of interest were generated. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages (%) are reported. Means with standard deviations (±) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) are reported for continuous variables.

Results

Patient population and pre-procedure information

A total of 10 patients (mean age 66.7 years, 30 % female) were included in the study. The clinical presentation was melena in six, hematemesis in two, and both hematemesis and melena in two. Prior to endoscopic hemostasis, twice-a-day proton pump inhibitor was given to all patients. Average lowest pre-endoscopy hemoglobin was 8.1 mg/dL (range 3.1 – 12.8). Reasons for endosuturing included bleeding refractory to standard endoscopic therapy in nine (90 %) and a very large ulcer with severe bleeding in one (10 %). Nine (90 %) had prior endoscopy therapy for UGIB prior to endoscopic suture, with an average of 1.4 ± 0.7 (range, 1 – 3) endoscopic sessions. Among the therapeutic modalities employed prior to the index suturing procedure, endoscopic clip(s) were used in 4/9 (44.4 %), bipolar probe was used in one of nine (11.1 %), and epinephrine injection in conjunction with either endoscopic clip(s) or bipolar probe was used in four of nine (44.4 %). ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Patient and ulcer characteristics and procedural results.

| Age/sex | Clinical presentation | Location of largest ulcer/size of the ulcer (mm)/ Forrest classification | Number of prior endoscopic therapy sessions before endosuturing | Reason for endoscopic suturing | Technical success/ number of sutures used | Immediate hemostasis | Early rebleeding (≤ 72 h)/Delayed rebleeding (> 72 h)/adverse events |

| 78/male | Melena | Gastric body/30/Ib | None | High-risk rebleeding due to very large ulcer size (3 cm diameter) | Yes/4 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 74/male | Melena | Gastric body/20/IIa | 1 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 57/male | Melena | Gastric body/30/IIa | 2 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/2 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 32/female | Melena | Pylorus/15/Ib | 2 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 76/male | Hematemesis | Proximal lesser curvature of gastric body/20/IIc | 3 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis. High risk rebleeding due to history of rebleeding, and large ulcer size and recent cardiovascular event required uninterrupted dual antiplatelet therapy | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 63/female | Melena | Anterior wall duodenum/20/Ib | 1 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 89/male | Melena | Gastric body/30/IIa | 1 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/2 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 64/male | Hematemesis and melena | Anterior wall duodenum/15/Ib | 1 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 48/male | Hematemesis and melena | Prepyloric antrum/25/IIb | 1 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

| 86/female | Hematemesis | Gastric cardia/15/Ib | 1 | Bleeding refractory to endoscopic hemostasis | Yes/1 | Yes | No/no/no |

Index ulcer

Bleeding sources were located in the gastric body in five, gastric cardia in one, prepyloric antrum in one, pylorus in one, and the anterior wall of the duodenum in two. Average size of the ulcer was 22 ± 6.3 mm (range 15 – 30). Forrest classification of the ulcer was Ib in five (50 %), IIa in three (30 %), IIb in one (10 %), and IIc in one (10 %). Biopsy was performed in seven of 10 cases; and cancer was not identified in any of the seven biopsies.

Endosuture procedure and follow-up data

Immediate hemostasis was achieved in five of five patients (100 %) with Forrest Ib ulcers. Technical success was 100 %. Mean suturing time was 13.4 ± 5.6 (range 3.5 – 20) minutes. Mean number of sutures used was 1.5 (range 1 – 4). The hemoglobin value was stable without additional transfusion in all patients. None of the patients experienced early rebleeding. One patient was then lost to follow up, thus follow-up data were available for nine patients at 30 days. Delayed recurrent bleeding was not observed in any of these cases. Median length of long-term follow-up for these nine patients was 11 months (range 2 – 56), and no additional gastrointestinal bleeding was reported in any of these cases over the full long-term follow-up period.

No AEs were observed both in the early period for 10 of 10 patients or late period for nine of nine patients with follow-up. Information on post-discharge EGD was available in four patients (40 %) after a median of 1 month (IQR, 0.75 – 2.25) after the endosuturing procedure. Of these, two had evidence of a small residual ulcer, two had a healed ulcer, and the original suture(s) were intact in all four.

Discussion

In this pilot study, oversewing of a bleeding peptic ulcer using endoscopic suturing appeared to be an effective method for achieving hemostasis for large, recurrent bleeding peptic ulcers which are usually difficult to manage. No early or delayed bleeding was noted in our series. Endoscopic suturing was technically successful in all cases, including ulcers at the pylorus and duodenum, with no AEs. While our study presents only a small sample size which will require validation in larger cohorts, our data suggest that rescue endoscopic hemostasis using endoscopic suturing can be an alternative option for treating nonvariceal UGIB when primary endoscopic hemostasis fails to control the bleeding or when hemorrhage recurs after successful control of bleeding. We wish to emphasize that for the indication for refractory or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding, this device and associated technique is still investigational and is not FDA approved.

The endoscopic suturing device directs a suture through the lining of the stomach or small intestine to bring two areas of mucosa and deeper wall layers in close apposition. This procedure mimics the hemostatic suturing methods us surgically. In addition, oversewing the ulcer could theoretically prevent exposure of the submucosal vessels in the ulcer bed to gastric contents 18 , thus potentially promoting healing of the ulcer and potentially decreasing risk for recurrent bleeding. However, these are only theoretical mechanisms, and given that two of four suture sites (50 %) seen on repeat endoscopy still had residual ulcer, one can argue that use of sutures in this setting does not in fact have any inherent advantage to promoting ulcer healing. Finally, it should be noted that a stitch that is too tight would in fact promote ischemia and potentially worsen the healing process, thus, extreme care must be taken in these cases.

In patients with clinical evidence of rebleeding, repeat endoscopic therapy is recommended 19 . Conventional through-the-scope (TTS) clips or thermal therapy with either bipolar electrocoagulation or heater probe are generally used. However, these treatment modalities are not always successful at hemostasis. For a fibrotic ulcer base, application of TTS clips is technically difficult, and repeated application of heater probe is associated with risk of thermal injury and perforation. In fact, a meta-analysis suggested that almost half of the perforations associated with thermal therapy occurred in patients who underwent repeat treatment 8 .

There are several new options for advanced endoscopic retreatment of bleeding peptic ulcer disease, and the efficacy of these new endoscopic modalities, such as hemospray and over-the-scope clips (OTSC), is also promising 20 21 . A brief comparison of the parameters to guide selection of these modalities provides useful context about when endoscopic suturing should be considered. Hemospray is generally considered a temporizing measure, rather than definitive treatment, for PUD-related UGIB. Although hemospray is effective with a greater than 90 % rate of immediate hemostasis, high rates of rebleeding up to 29 % to 38 % in benign nonvariceal UGIB have been reported 22 23 . Thus, it is recommended as a bridge to more definitive treatment 22 24 . Use of OTSC is limited by ulcer size, because a large ulcer would not be amenable to such therapy. Further, for deep or fibrotic ulcers, placement of OTSC is technically difficult as the ulcer may not invert adequately into the cap and lead to clip misplacement 25 . Thus, OTSC deployment should be used for small, shallow, and non-fibrotic ulcers. Finally, advantages of endoscopic suturing compared to other endoscopic modalities include its efficacy even for large ulcers in difficult locations such as high lesser curvature and pylorus. Disadvantages include the need for a double channel endoscope and the requirement for extensive expertise and training in performing the suturing procedure. Performing endoscopic suturing in retroflexion can be challenging given difficult scope maneuverability and limited visualization. Use of the tissue helix along with rotation of the scope may aid in accomplishing suturing on the retroflexed position. Another concern is the risk that suturing could close and hide a carcinomatous ulcer. It is advisable to avoid endosuturing if there is a suspicion of malignant ulcer. We biopsy gastric ulcers prior to endosuturing and recommend follow-up endoscopy to assess ulcer healing. In the setting of persistent, non-healing gastric ulcer, biopsy should also be obtained of at the follow-up endoscopy.

Although angioembolization of a targeted bleeding vessel has a high technical success rate, clinical success rates for this procedure are below 80 % 20 and associated AEs, such as small bowel ischemia or stricture, hepatic infarct, access site hematoma and pseudoaneurysms, are reported as high as 26 % 26 . Surgical management of PUD such as ulcer exclusion and vagotomy are associated with surgical morbidities and mortality. In both surgical and angioembolization procedures, recurrent bleeding has been shown to occur in about one-quarter of cases with high rates of subsequent reproceduralization at 20 % 21 . Thus, use of rescue endoscopic methods such as endosuturing may play a role in therapy of UGIB.

To our knowledge, this study represents the largest series of patients who have undergone endoscopic suturing for a bleeding peptic ulcer. Limitations include its small sample size and its retrospective nature. In addition, the endosuturing technique was not standardized and there may be minor variations in technique used. Further, this procedure was performed by highly experienced endoscopists with training in advanced procedures, resulting in a short procedure time and a high success rate, and the results may not be generalizable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, endoscopic suturing for acute UGIB has a high technical success rate as well as desirable clinical results of hemostasis and prevention of recurrent bleeding. This modality represents a useful adjunct to the therapeutic armamentarium as a rescue therapy for refractory bleeding that has failed standard endoscopic hemostasis. Further research is needed to validate our results as well as determine its superiority relative to other endoscopic hemostatic modalities.

Competing interests Dr. Kumbhari is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Apollo Endosurgery, Medtronic, and ReShape Medical. Dr. Kalloo is a founding member, equity holder, and consultant for Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. Khashab is a consultant for Boston Scientific.

These authors contributed equally.

References

- 1.Peery A F, Crockett S D, Barritt A S et al. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1731–1741 e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hearnshaw S A, Logan R F, Lowe D et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327–1335. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gralnek I M, Dumonceau J M, Kuipers E J et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Leerdam M E. Epidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook D J, Guyatt G H, Salena B J et al. Endoscopic therapy for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 1992 Jan. 102:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipolletta L, Cipolletta F, Marmo C et al. Mechanical methods to endoscopically treat non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;18:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahidi N, Enns R. Hemostatic sprays to control active non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;18:198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laine L, McQuaid K R. Endoscopic therapy for bleeding ulcers: an evidence-based approach based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau J Y, Sung J, Hill C et al. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011;84:102–113. doi: 10.1159/000323958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bratanic A, Puljiz Z, Ljubicicz N et al. Predictive factors of rebleeding and mortality following endoscopic hemostasis in bleeding peptic ulcers. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:112–117. doi: 10.5754/hge11838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alli O, Smith C, Hoffman M et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:410–414. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181faec3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin C C, Hu H Y, Luo J C et al. Risk factors of gastrointestinal bleeding in clopidogrel users: a nationwide population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1119–1128. doi: 10.1111/apt.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holster I L, Valkhoff V E, Kuipers E J et al. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(01):105–112 e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasselgren G, Carlsson J, Lind T et al. Risk factors for rebleeding and fatal outcome in elderly patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng F H, Wong S Y, Chang C M et al. High incidence of clopidogrel-associated gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with previous peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:443–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu P W, Chan F K, Lau J Y. Endoscopic suturing for ulcer exclusion in patients with massively bleeding large gastric ulcer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:29–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotton P B, Eisen G M, Aabakken L et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujihara S, Mori H, Kobara H et al. The efficacy and safety of prophylactic closure for a large mucosal defect after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:85–90. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laine L, Jensen D M. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345–360. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aina R, Oliva V L, Therasse E et al. Arterial embolotherapy for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: outcome assessment. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61825-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ripoll C, Banares R, Beceiro I et al. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:447–450. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000126813.89981.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yau A H, Ou G, Galorport C et al. Safety and efficacy of Hemospray(R) in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:72–76. doi: 10.1155/2014/759436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y I, Barkun A, Nolan S. Hemostatic powder TC-325 in the management of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a two-year experience at a single institution. Endoscopy. 2015;47:167–171. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkun A N, Moosavi S, Martel M. Topical hemostatic agents: a systematic review with particular emphasis on endoscopic application in GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asokkumar R, Kaltenbach T, Soetikno R. Use of over-the-scope clip to treat bleeding duodenal ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:459–460. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yap F Y, Omene B O, Patel M N et al. Transcatheter embolotherapy for gastrointestinal bleeding: a single center review of safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1976–1984. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]