Abstract

Background

Renal ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury is a major cause of acute kidney injury (AKI), which is associated with high morbidity and mortality. AKI is a serious and costly medical condition. Effective therapy for AKI is an unmet clinical need, and molecular mechanisms underlying the interactions between an injured kidney and distant organs remain unclear. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies should be developed.

Methods

We directed the differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells into endothelial progenitor cells (iEPCs), which were then applied for treating mouse AKI. The mouse model of AKI was induced by I/R injury.

Results

We discovered that intravenously infused iEPCs were recruited to the injured kidney, expressed the mature endothelial cell marker CD31, and replaced injured endothelial cells. Moreover, infused iEPCs produced abundant proangiogenic proteins, which entered into circulation. In AKI mice, blood urea nitrogen and plasma creatinine levels increased 2 days after I/R injury and reduced after the infusion of iEPCs. Tubular injury, cell apoptosis, and peritubular capillary rarefaction in injured kidneys were attenuated accordingly. In the AKI mice, iEPC therapy also ameliorated apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and cardiac dysfunction, as indicated by echocardiography. The therapy also ameliorated an increase in serum brain natriuretic peptide. Regarding the relevant mechanisms, indoxyl sulfate and interleukin-1β synergistically induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. Systemic iEPC therapy downregulated the proapoptotic protein caspase-3 and upregulated the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in the hearts of the AKI mice, possibly through the reduction of indoxyl sulfate and interleukin-1β.

Conclusions

Therapy using human iPS cell-derived iEPCs provided a protective effect against ischemic AKI and remote cardiac dysfunction through the repair of endothelial cells and the attenuation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13287-018-1092-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Indoxyl sulfate, Cardiac dysfunction, Endothelial progenitor cells, Induced pluripotent stem cells

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a potentially devastating clinical problem [1]. Despite the availability of renal replacement therapy, AKI is associated with high mortality and morbidity [2–5]. When kidneys fail, dangerous levels of metabolites and waste products, including uremic toxins, accumulate in the body. Clinical evidence suggests that AKI is not only an indicator of illness severity but that it also leads to distant-organ injury and considerably affects mortality [6–10]. Grams et al. observed that AKI is not an isolated event and that it results in heart dysfunction through a proinflammatory mechanism involving inflammatory cytokine expression and increased oxidative stress [7]. A recent study further demonstrated that AKI may activate the production of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and may induce mitochondrial fragmentation in cardiomyocytes, thereby leading to cell apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction. Drp1 has thus become a new therapeutic target to alleviate AKI-induced cardiac dysfunction [10].

An increasing number of studies have provided evidence that cell therapy can lead to the repair of damaged kidney tissue; therapy with pluripotent stem cells has been demonstrated to lead to functional recovery in preclinical kidney models [11–13]. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can be obtained by reprogramming a broad range of adult somatic cell types to develop into embryonic stem cell-like pluripotent cells [14]. iPS cell technology represents a promising, novel strategy for the derivation of clinically applicable lineage-specific cells, such as endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) [14–16]. Furthermore, iPS cells can be generated from cells from any part of an adult and exhibit potential for facilitating genetically matched “patient-specific” cell therapy, which would solve both ethical problems and immune system rejection [17, 18].

The enormous therapeutic potential of isolated human EPCs has been demonstrated for a wide range of ischemic tissues [19]. Many researchers believe that the therapeutic effect of these cells is mediated by their production of cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and antifibrogenic factors as well as by their differentiation into specific cell types [20, 21]. Despite advances in adult stem cell technology, limited accessibility, limited numbers of functional cells, and cellular heterogeneity remain obstacles for drug discovery and successful application of regenerative medicine [13, 22, 23]. iPS cell therapy has led to functional recovery in animal models [24, 25]. However, therapy using iPS cells has also induced undesirable effects, including teratoma formation [13, 26]. Directing the differentiation of iPS cells into specific cell types for transplantation may be a more favorable option.

Yoo et al. induced the differentiation of human iPS cells into EPCs (iPS cell-derived EPCs, iEPCs) and confirmed the therapeutic effect of iEPC infusion in mouse models of hind limb ischemia and myocardial infarction [27]. Inspired by the aforementioned previous study, we considered whether therapy using iEPCs would result in protective effects in a mouse model of AKI induced by ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury. Our data revealed that iEPC therapy is a promising treatment strategy for AKI and remote cardiac dysfunction and that its protective effects are exerted through attenuation of apoptosis and inflammation.

Methods

An expanded version of the “Methods” section is available in Additional file 1 and includes details on the following: approval for human studies, patients, generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells, characterization of iPS cell-derived EPCs, culture of HL-1 cardiomyocytes, tissue preparation for pathological examinations, scoring of tubular injury, evaluation of microvessels, identification of apoptosis by TUNEL staining, cell lysate preparation and Western blot analysis, evaluation of renal function, measurement of plasma interleukin-1β, measurement of plasma brain natriuretic peptide, measurement of plasma indoxyl sulfate, measurement of circulating human cytokines, and echocardiographic analysis.

AKI model and iEPC therapy

Male (8–10 weeks) adult nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice were anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine (100/10 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and were then subjected to right nephrectomy. Two weeks later, the left kidney was clamped for 24 min by using a nontraumatic micro-aneurysm clip (Karl Klappenecker, Tuttlingen-Nendingen, Germany) to induce an I/R injury under the homeothermic blanket system (Stoelting Co. Wood Dale, IL). In the blanket system, a rectal thermal probe and a heating pad were used to maintain the core body temperature at 37 °C. After removal of the clamp, blood flow reperfusion was confirmed visually. The mice were divided into two groups: AKI-iEPC mice and AKI-vehicle mice. In AKI-iEPC mice, 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) cell suspension containing 5 × 105 iEPCs was infused via the tail vein 15 min after reperfusion. AKI-vehicle mice were infused with 200 μL of PBS. Sham controls underwent the same surgical procedure but without vascular occlusion. All of the animal experiments were performed in accordance with the details of the relevant guidelines and regulations and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). One-way analysis of variance with post hoc analysis using Tukey’s method was conducted for multiple group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

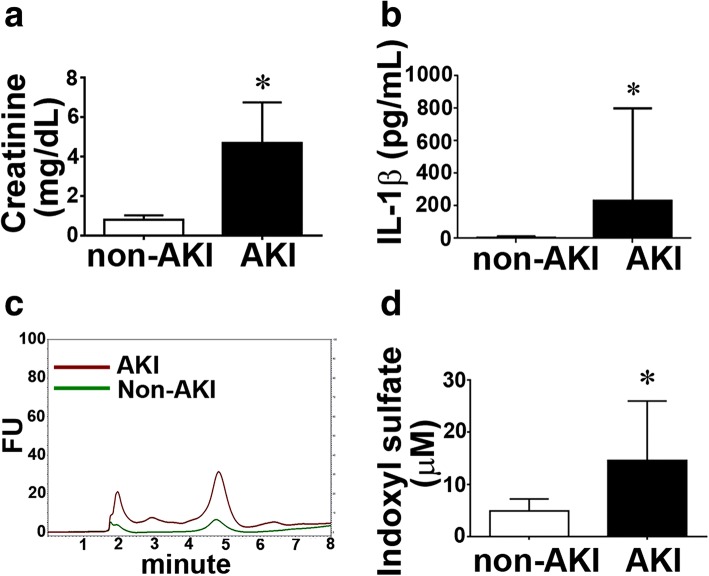

Increased plasma levels of creatinine, indoxyl sulfate, and interleukin-1β in patients with AKI

In the present study, 25 consecutive patients were enrolled upon receiving diagnosis of AKI. Day 2 serum level of creatinine was significantly higher in patients with AKI than in non-AKI controls (Fig. 1a). Serum levels of indoxyl sulfate (IS) and interleukin 1β (IL-1β) in each group were studied. Patients with AKI exhibited increased serum levels of IS (AKI, 18.1 ± 4.5 vs. non-AKI, 3.9 ± 0.6 μM; Fig. 1a, b) and IL-1β (AKI, 467 ± 50 vs. non-AKI, 97 ± 12 pg/mL; Additional file 1: Figure S2, Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Increased plasma levels of creatinine and indoxyl sulfate in patients with AKI. a Bar chart denoting plasma creatinine levels in AKI and non-AKI patients. N = 25 per group. b Increased plasma levels of interleukin-1β in patients with AKI. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 10 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. non-AKI group. c Representative chromatogram for measurement of plasma indoxyl sulfate (IS). FU indicates fluorescence unit. d Bar chart representing plasma IS in AKI and non-AKI patients. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. non-AKI group

Characterization of human iEPCs

A colony-forming unit of iEPCs was defined as a central core of round cells with elongated sprouting cells at the periphery (Additional file 1: Figure S1a and b). In contrast to iPS cells, iEPCs were spindle shaped in morphology when they reached confluence, similar to the morphology of mature endothelial cells (Additional file 1: Figure S1c and d). We also confirmed that acetylated low-density lipoprotein (acLDL) was taken up by iEPCs but not by iPS cells (Additional file 1: Figure S1e and f). In addition, primitive vascular tube-like structures developed in iEPCs when they were grown in Matrigel (Additional file 1: Figure S1 g and h). According to the results of immunostaining and flow cytometric analyses, both iPS cells and iEPCs expressed the stem cell marker CD133 (Additional file 1: Figure S2). However, only iEPCs expressed EPC marker kinase insert domain receptor (KDR; Additional file 1: Figure S2). CD31 and VE-cadherin, which are markers of mature endothelial cells, were also expressed in 57.6% and 53.3% of iEPCs, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

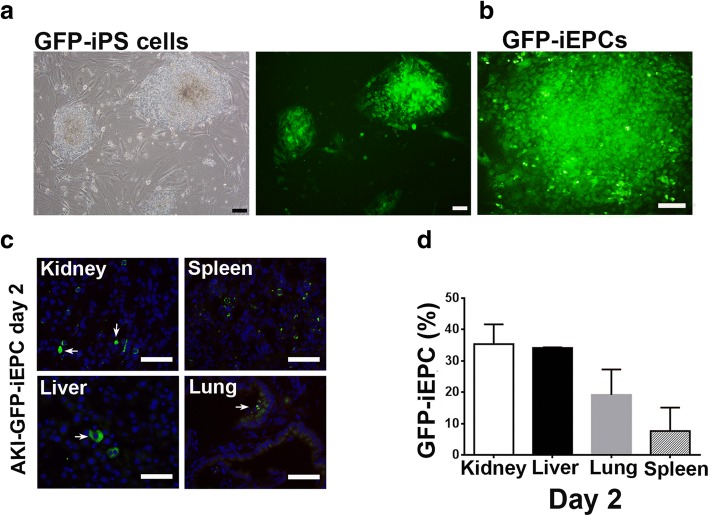

Recruitment of iEPCs to the interstitium of AKI kidney

To assess the therapeutic effect of iEPCs on I/R-induced AKI, we first determined whether iEPCs could be recruited to the injured kidney. Lentivirus-green florescent protein (GFP)-transduced iPS cells were differentiated into GFP-iEPCs (Fig. 2a, b, Additional file 1: Fig. 3a, b). Fifteen minutes after reperfusion of ischemic kidneys, 5 × 105 GFP-iEPCs were injected via the tail vein, and the kidneys were analyzed 2 days later (Fig. 2c, d). Many GFP-iEPCs were detected in the interstitium of the kidneys (Fig. 2c). As expected, GFP-iEPCs were also identified in the lung, liver, and spleen (Fig. 2c). However, among the organs examined, the proportion of GFP-iEPCs was highest in the kidneys (Fig. 2d). No GFP-iEPCs were observed in the heart.

Fig. 2.

Intravenously infused human iPS cell-derived endothelial progenitor cells (iEPCs) were recruited to the post ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injuries of the kidney, spleen, liver, and lung, but not the heart of nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice. a Bright-field and fluorescence images depicting undifferentiated colonies of lentivirus-GFP-transduced iPS cells on mitotically inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Fluorescence images depicting a differentiated colony of GFP-iEPCs. Scale bar = 200 μm. c Fluorescence images depicting GFP-iEPCs recruited to the kidney, spleen, liver, and lung 48 h after intravenous infusion in mice with AKI induced by renal I/R injury. Arrows indicate GFP-iEPCs. Scale bar = 50 μm. d Bar chart denoting the percentage of recruited GFP-iEPCs per field captured at the original magnification × 400. The denominator is the sum of GFP-iEPCs in the kidney, spleen, liver, and lung. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 4 per group

Fig. 3.

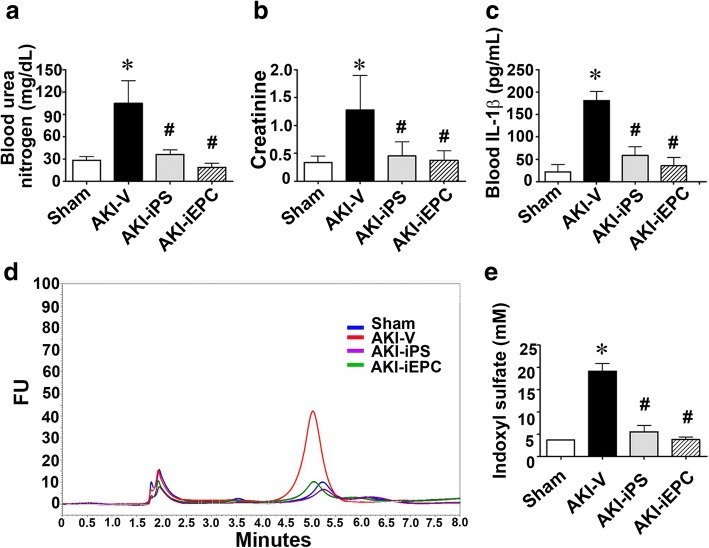

Systemic human iPS cell-derived iEPC therapy reduced azotemia and systemic inflammation after acute kidney injury (AKI). a–c Plasma levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in mice subjected to sham surgery or renal I/R injury treated with vehicle (AKI-V) and systemic iEPC or iPS therapy (AKI-iEPC or AKI-iPS). N = 7–18 per group. d Representative image illustrating the measurement of plasma indoxyl sulfate by liquid chromatography. FU indicates fluorescence unit. e Bar chart denoting plasma levels of indoxyl sulfate in each group. N = 5 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 AKI-V vs. Sham, #P < 0.05 AKI-iEPC or AKI-iPS vs. AKI-V group

Systemic iEPC therapy reduced azotemia and systemic inflammation after AKI

To assess the therapeutic effect of iEPCs on AKI, iEPCs or PBS vehicle was injected via the tail vein 15 min after renal I/R surgery. Systemic iPS and iEPC therapy resulted in a significant decrease in plasma levels of creatinine (0.4 ± 0.1 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN; 19.1 ± 2.7 mg/dL) compared with the levels in vehicle-treated mice (creatinine, 1.3 ± 0.3 mg/dL and BUN, 105 ± 15.1 mg/dL; Fig. 3a). Similar to findings reported for patients with AKI (Fig. 1), plasma levels of IL-1β and IS were higher in AKI-vehicle mice than those in sham mice on day 2 after injury (Fig. 3c–e). iPS or iEPC therapy reduced the increase in plasma IL-1β and IS levels in AKI mice, and this result was comparable to the therapies’ beneficial effect on kidney function (Fig. 3c–e).

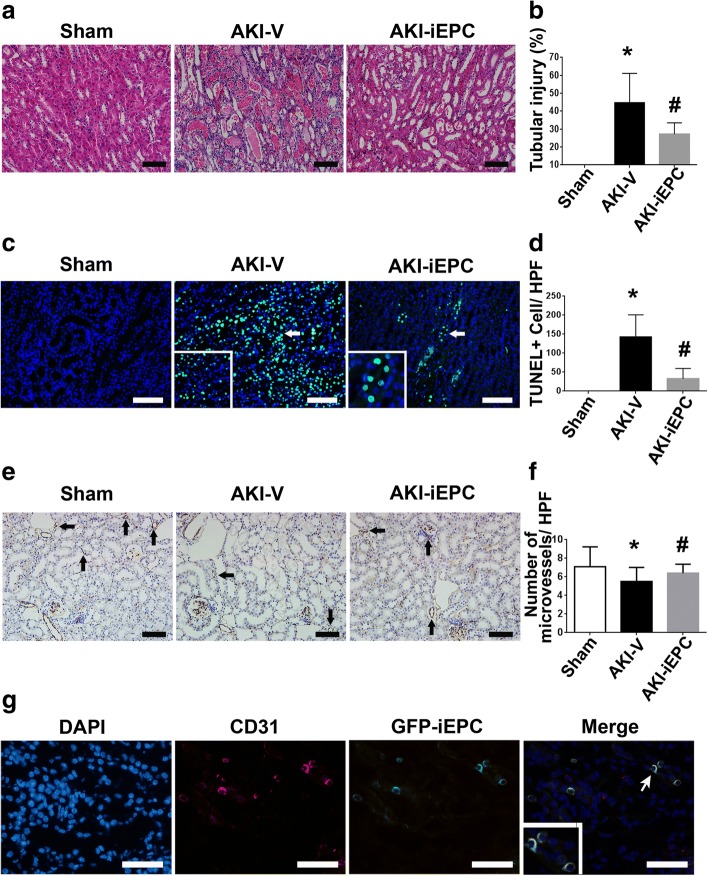

Systemic iEPC therapy attenuated tubular injury and peritubular capillary rarefaction after AKI

Given that iEPCs were recruited to the injured kidney and reduced azotemia, we next studied the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effect. iEPC therapy induced restoration of the corticomedullary junction in the AKI-vehicle kidney on day 2 after I/R injury (Additional file 1: Figure S4). iEPC therapy also attenuated marked tubular injuries, including intratubular cast, absence of nuclei, and tubular dilation, in the AKI-vehicle kidney (Fig. 4a, b). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL+) apoptotic cells in the AKI-vehicle kidney were also attenuated by iEPC therapy (Fig. 4c, d). Decreases in CD31+ staining revealed rarefaction of peritubular capillaries in the AKI-vehicle kidneys, and this was also improved by iEPC therapy (Fig. 4e–f).

Fig. 4.

Systemic human iPS cell-derived iEPC therapy attenuated tubular injury and peritubular capillary rarefaction after acute kidney injury (AKI). a Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained images depicting tubular injuries, including tubular necrosis, absence of nuclei, tubular dilatation, and intratubular cast, on day 2 after sham or AKI. b Bar chart representing semiquantitative analyses of tubular injury on day 2 after sham or AKI. N = 10 per group. c Representative immunofluorescence images of the detection of apoptosis through terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining on day 2 after sham or AKI. Arrows indicate TUNEL+ (green) nuclei (blue). d Bar chart representing quantitative analyses of the numbers of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells per high-power field (× 200 magnification) on day 2 after sham or AKI. N = 8 per group. e Representative immunohistochemical images depicting the staining of CD31+ endothelial cells on day 2 after sham or AKI. Arrows indicate CD31+ staining (brown). f Bar chart representing quantitative analyses of the number of microvessels per HPF on day 2 after sham or AKI. N = 10 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 AKI-V vs. Sham, #P < 0.05 AKI-iEPC vs. AKI-V group. Scale bar = 100 μm. g Representative immunofluorescence images depicting recruited GFP-iEPCs expressing human CD31 on day 2 after AKI. Arrow indicates a GFP-iEPC expressing CD31. Scale bar = 50 μm

Recruited iEPCs repaired endothelial cells in AKI kidneys and expressed proangiogenic factors

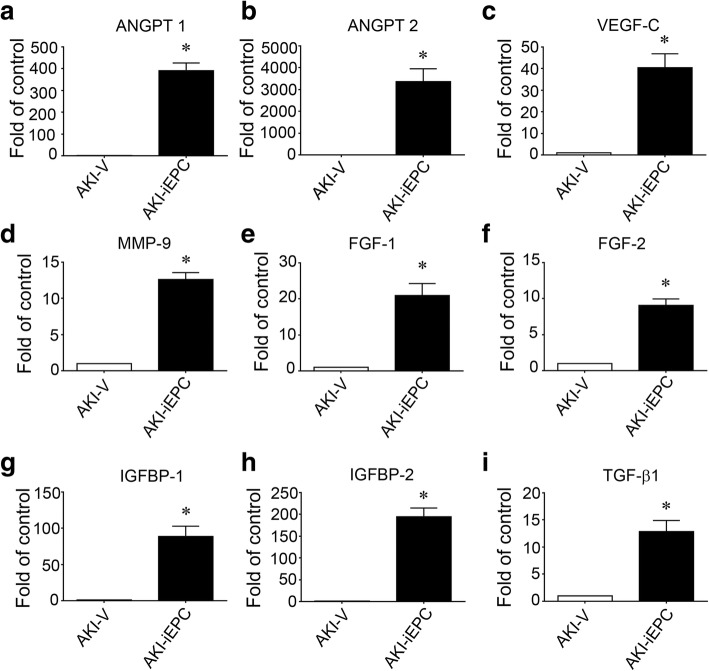

To further analyze the mechanism by which iEPCs maintained microvasculature in AKI kidneys, we determined whether iEPCs differentiated into endothelial cells. We found that all GFP-iEPCs were positive for human CD31 in the kidneys of AKI-iEPC mice, suggesting that iEPCs differentiated into mature endothelial cells (Fig. 4g). However, we discovered that GFP-iEPCs accounted for less than 1% of mouse CD31+ endothelial cells (data not shown). These investigations provided evidence of an extremely rare contribution of iEPCs to direct endothelial replacement, and the marked expression of the mature endothelial cell marker CD31 in all recruited iEPCs was noted; therefore, we measured circulating angiogenesis-related proteins to determine whether paracrine mechanisms underlie systemic-iEPC-therapy-induced maintenance of microvasculature in AKI kidneys. Compared with levels in AKI-vehicle mice, plasma levels of angiopoietin-1 (Angpt1), angiopoietin-2 (Angpt2), vascular endothelial cell growth factor-C (VEGF-C), matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9), fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF1), FGF2, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), IGFBP-2, and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) had considerably increased in AKI-iEPC mice 2 days after injection (Fig. 5, Additional file 1: Figure S5).

Fig. 5.

a–i Systemic human iPS cell-derived iEPC therapy increased the plasma concentrations of angiogenesis-related proteins. Bar charts denoting the relative folds of plasma angiogenesis-related proteins—including Angpt1, Angpt2, VEGF-C, MMP 9, FGF 1, FGF 2, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, and TGF-β1—on day 2 after acute kidney injury (AKI). N = 3 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.001 AKI-iEPC vs. AKI-V group

Systemic iEPC therapy attenuated cardiac dysfunction after AKI

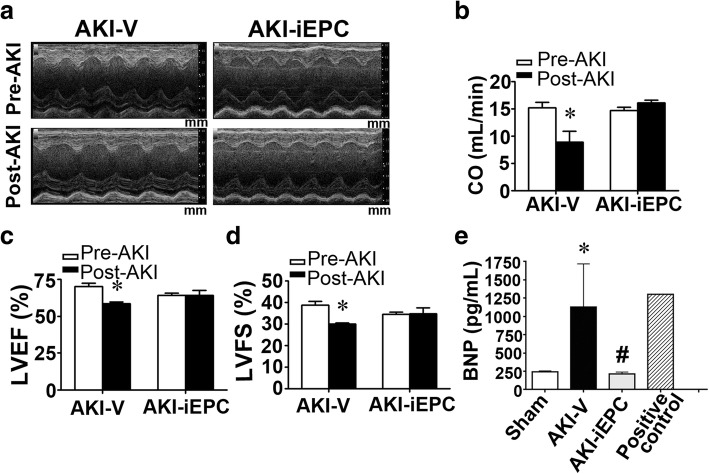

The plasma level of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was significantly higher in patients on day 2 after AKI, suggesting congestion of cardiac atria (Additional file 1: Figure S6). To assess cardiac function in AKI mice, echocardiography was performed on day 2 after I/R surgery. Representative M-mode tracings indicated significant improvement of cardiac function in AKI mice after iEPC therapy (Fig. 6a). Cardiac dysfunction—as evident by decreases in cardiac output (CO), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS)—in AKI mice was attenuated after iEPC therapy (Fig. 6b–d). In AKI mice, elevated plasma levels of BNP, which contributes to cardiac dysfunction, were substantially attenuated by iEPC therapy, and this result agreed with the findings from echocardiography (Fig. 6e).

Fig. 6.

Systemic human iPS cell-derived iEPC therapy attenuated cardiac dysfunction after acute kidney injury (AKI). a Representative M-mode echocardiographic images of the left ventricles in mice before (Pre-AKI) or 2 days after AKI (Post-AKI). Mm (millimeter) indicates the depth of tissues. b–d Cardiac function parameters including cardiac output (CO), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), as assessed using M-mode echocardiography. N = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. Pre-AKI. e Plasma levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). N = 5 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 AKI-V vs. Sham, #P < 0.05 AKI-iEPC vs. AKI-V group

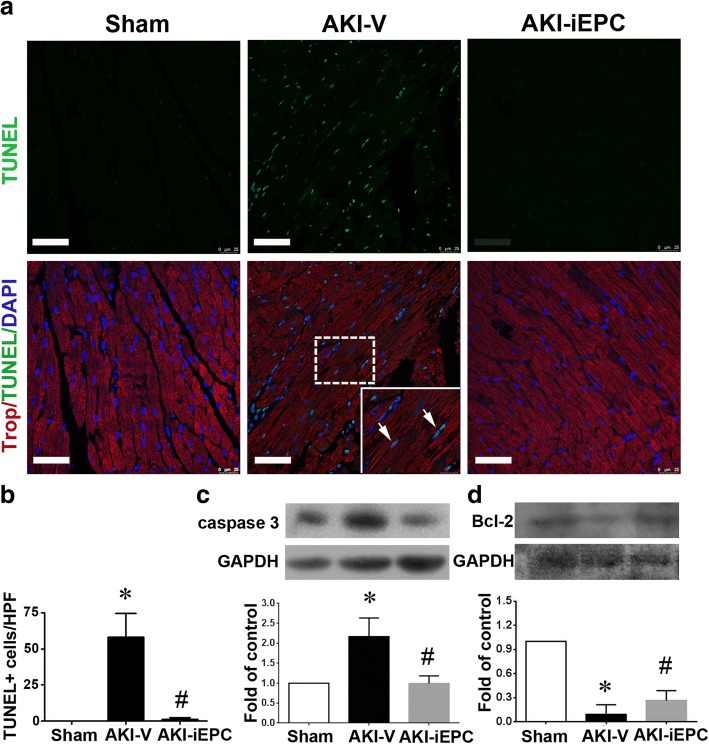

Systemic iEPC therapy attenuated apoptosis of cardiomyocytes in AKI mice

Following the previously described experiments, we investigated the possible mechanisms underlying the protective effect of iEPC therapy on cardiac function in AKI mice. Apoptosis of left ventricular cardiomyocytes, which was assessed using terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining, was elevated in AKI mice (Fig. 7a, b), and iEPC therapy substantially reduced the elevated apoptosis (Fig. 7a, b). Moreover, the expression of the apoptotic protein caspase 3, which was elevated in the left ventricle of AKI mice, was also inhibited by iEPC therapy (Fig. 7c). By contrast, the downregulation of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in the left ventricle of AKI mice was partially attenuated by iEPC therapy (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 7.

Systemic human iPS cell-derived iEPC therapy attenuated apoptosis of cardiomyocytes in acute kidney injury (AKI) mice. a Representative immunofluorescence images depicting TUNEL+ cells in the left ventricles on day 2 after sham or AKI. Arrows indicate TUNEL+ (green) nuclei (blue) and cardiomyocytes staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Bar chart illustrating quantitative analyses of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells per high-power field (× 200 magnification) in the left ventricle on day 2 after sham or AKI. N = 8 per group. c, d Representative images of Western blot analyses of caspase 3 and Bcl-2 in the left ventricles on day 2 after sham or AKI. GAPDH was used as the control of protein loading. Bar charts illustrating quantitative analyses. N = 3 per group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 AKI-V vs. Sham, #P < 0.05 AKI-iEPC vs. AKI-V group

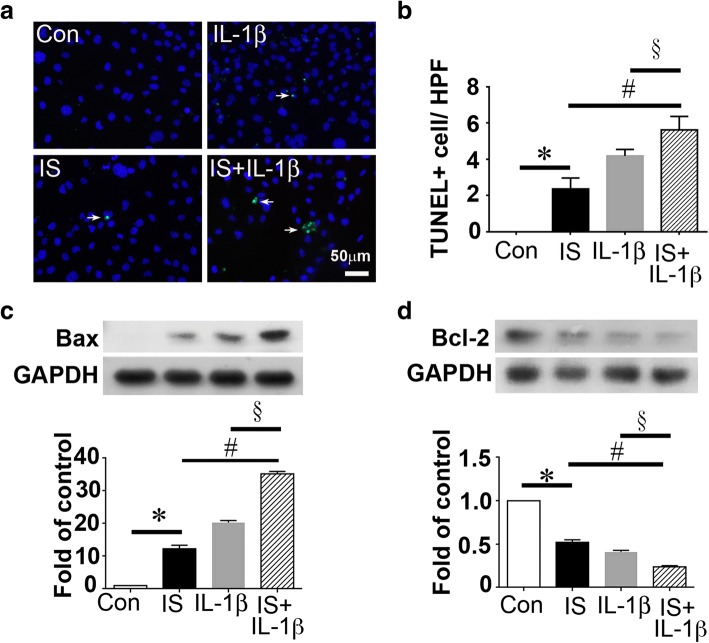

Indoxyl sulfate and interleukin-1β induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis synergistically

Based on the finding that IS and IL-1β increased systemically in AKI patients and mice (Fig. 1, Fig. 3c–e) and systemic iEPC therapy decreased IS and IL-1β in AKI mice, we determined whether IS or IL-1β played a role in the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. At the concentrations (0.2 mM IS and 200 ng/mL) observed in patients with AKI, IS and IL-1β induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes HL-1 (Fig. 8a, b). Moreover, IS and IL-1β synergistically induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Fig. 8a, b). Mechanistically, IS and IL-1β upregulated the proapoptotic protein Bax but downregulated the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 8c, d).

Fig. 8.

Indoxyl sulfate (IS) and interleukin (IL)-1β induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis after treatment with IS or IL-1β. a Representative immunofluorescence images presenting TUNEL+ (green) HL-1 cardiomyocytes cultured in medium with or without IS or IL-1β. Con indicates control. Scale bar = 50 μm. b Bar chart depicting quantitative analyses of TUNEL+ HL-1 cardiomyocytes per high-power field (× 400 magnification). c, d Representative images of Western blot analyses and the statistical analyses for Bax, Bcl-2, and GAPDH in HL-1 cardiomyocytes cultured in medium with or without IS or IL1-β. The protein levels of Bax and Bcl-2 were normalized using GAPDH in bar charts. N = 3 per group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 IS vs. Con, #P < 0.05 IL-1β + ΙS vs. IS, §P < 0.05 IL-1β + ΙS vs. IL-1β

Discussion

Our findings provide the first evidence that human iPS cell-derived iEPC therapy is a promising therapy that may attenuate apoptosis and thereby protect the kidneys from microvascular rarefaction and tubular decomposition induced by I/R injury. The present study also revealed that AKI-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction were attenuated by this therapy.

I/R injury is the most common cause of AKI in patients [1]. Vascular and tubular changes, alongside interstitial inflammation, cause acute decreases in kidney function. AKI-induced IS and IL-1β, the expression of which was examined in this study, damage endothelial cells and cause myocardial injury, respectively [28, 29]. Despite extensive research through preclinical studies, no therapeutic interventions using iPS cell-derived iEPCs have been reported to prevent or accelerate recovery from AKI [30]. This failure in translation has led investigators to speculate that the animal models and study designs used in the relevant research do not predict clinical responses. Our pilot experiments with mice subjected to bilateral renal I/R injury frequently resulted in unequal kidney sizes, with one atrophic kidney and another hypertrophic kidney 2 weeks after injury. These results demonstrated the technical difficulty of inducing equal injuries to both kidneys in a model of bilateral I/R injury. Therefore, in the present study, we performed right nephrectomy in 8–10-week-old mice, followed by left renal I/R injury 2 weeks later. This AKI model was reliable and facilitated the objective evaluation of kidney function and renal pathology. Our data revealed that intravenous infusion of iEPCs 15 min after renal I/R surgery provided protective effects not only for kidney function but also for distant organs such as the heart. Lentiviral transduction enabled reliable fate tracing of infused iEPCs, and the results indicated that GFP-iEPCs were mainly recruited to the interstitium of the injured kidney. Recruited iEPCs preferentially lined up with mouse CD31+ endothelial cells and upregulated their own CD31, indicating the potential of infused iEPCs to replace injured endothelial cells. This finding is in line with those of previous reports that demonstrated the homing of EPCs, isolated from various tissues, into injured blood vessels [31–40]. However, direct endothelial replacement by GFP-iEPCs only accounted for extremely small number of cells in blood vessels. Our data further supported that iEPC therapy might preserve microvasculature by causing the expression of high levels of angiogenesis-related proteins, including Angpt1, Angpt2, VEGF-C, MMP9, FGF1, FGF2, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, and TGF-β1. This finding was in line with evidence that EPCs release potent proangiogenic growth factors [41]. Proangiogenic growth factors appear to be produced not only by EPCs but also by hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells [11, 42]. In this study, we did not gain insight into the role of each angiogenesis-related protein expressed in AKI-iEPC mice. However, the proangiogenic properties of growth factors and effectors, including angiopoietin, CXCL8, and MMP9, have been demonstrated in previous studies involving neutralization of antibodies, specific antagonists, or genetic disruption against specific factors [43–47]. In addition, one independent study demonstrated that EPCs may exhibit cytoprotective effects through the broad synergistic action of many growth factors and effectors, resulting from modulation of intracellular anti-oxidative defensive mechanisms and prosurvival signals [48]. In this study, both direct endothelial replacement with iEPCs and iEPCs’ stimulation of the production of many proangiogenic growth factors and effectors were observed in AKI kidneys, and these effects contributed to the attenuation of microvascular rarefaction and tubular decomposition.

Our echocardiography data indicated that iEPC therapy exhibited a protective effect against AKI-induced cardiac dysfunction. We did not observe any GFP-iEPCs in mouse hearts, suggesting that the possibility of a direct cardiac effect was negligible. Considering that iEPC therapy prevented kidney injury, the protective effect of iEPC therapy on the heart may have resulted from the reduction of uremic toxin IS and proinflammatory IL-1β in circulation. Our study further supported that IS and IL-1β at the concentrations observed in patients with AKI were proapoptotic to cardiomyocytes. The number of apoptotic cardiomyocytes in AKI mice decreased after iEPC therapy, suggesting that iEPC therapy exerted prosurvival and anti-apoptotic effects resulting from the attenuation of AKI and the reduction of circulating IS and IL-1β levels. A recent study demonstrated that AKI may activate Drp1, inducing mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, but the mechanism underlying Drp1 activation and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes following renal I/R injury has not been identified [10]. In the present study, IS and IL-1β did not induce Drp1 activation, but our data supported that IS and IL-1β could induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, and this mechanism may account for cardiac dysfunction induced by AKI.

iPS cell technology enables the reprogramming of a wide variety of somatic cell types into various other types of cells. This technology offers a novel strategy for patient-specific derivation of clinically applicable lineage-specific cells, such as EPCs [15, 16, 49]. Directing the in vitro differentiation of iPS cells into functional EPCs may serve as a paradigm for human disease modeling and EPC-based therapies [15, 39, 40]. In the present study, iPS cells were differentiated into iEPCs, which expressed mature EPC markers such as CD133 and KDR. Thus, iPS cells can be used to derive numerous cells that can be differentiated into EPCs for transplantation purposes, as shown in this study. Moreover, recent evidence has revealed that iPS cells can also be induced to cells expressing markers of proximal tubules or podocytes [50–52]. Similar to the direct endothelial replacement by iEPCs in our study, Sharmin et al. demonstrated that the transplantation of human iPS cell-derived nephron progenitors, using spacers to release the tension of host kidney capsules, allowed the effective formation of glomeruli, in which iPS cell-derived podocytes accumulated around the fenestrated endothelial cells [52].

Tumorigenesis is a challenge in stem cell therapy. In some animal studies, direct implantation of iPS cells led to tumor formation [26, 53]. Therefore, directed differentiation into iEPCs should be conducted before transplantation to avoid the possibility of tumorigenesis. In this short-term study, we did not observe any abnormal cell proliferation after iEPC therapy. The long-term safety of iEPC therapy requires further exploration. Our data indicated that intravenous infusion of iEPCs did not cause abnormal proliferation in the heart or kidney (data not shown).

Conclusions

The present report demonstrated the potential of human iPS cell-derived iEPCs as a novel therapy for ischemic AKI and remote cardiac dysfunction. The protective effects of this therapy most likely result from attenuation of apoptosis and inflammation. Further research is required to verify the long-term safety of this therapy.

Additional file

Figure S1. Characterization of human iPS cell-derived endothelial progenitor cells (iEPCs). Figure S2 Characterization of human iPS cell-derived endothelial progenitor cells (iEPCs). Figure S3 GFP-iEPC sorting. Representative flow cytometric analyses for (A) control iPS cells and (B) lentivirus-GFP-transduced iPS (GFP-iPS) cells. Figure S4 Gross appearance of kidneys with sham or AKI. Figure S5 Measurement of human angiogenesis-related proteins in the plasma of AKI mice. Figure S6 Increased plasma levels of brain natriuretic peptide in AKI patients. (DOC 7402 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Medical Research of National Taiwan University Hospital for equipment support, the Imaging Core Facility of the First Core Laboratory, the Laboratory Animal Center of National Taiwan University College of Medicine, and the National RNAi Core Facility at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica for the provision of EGFP lentivirus (C6-4-2).

Funding

WCS was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), Taiwan (102-2811-B-002-124, 103-2811-B-002-040, 104-2811-B-002-046). YHC was supported by MOST (104-2314-B-002-119-MY3) and the Mrs. Hsiu-Chin Lee Kidney Research Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

For data requests, please contact the author.

Abbreviations

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- Angpt

Angiopoietin

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

- CO

Cardiac output

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- I/R

Ischemia–reperfusion

- IGFBP

Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVFS

Left ventricular fractional shortening

- MMP9

Matrix metallopeptidase 9

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-β1

- VEGF-C

Vascular endothelial cell growth factor-C

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived by WCS, YHC, and HFC. WCS, YHC, HPH, and JFS were all involved in the performance of key experiments. WCS, YHC, and HFC performed data analysis. WCS wrote the first draft of the manuscript and performed experiments for revision with support from SCH. All authors including SCH subsequently provided revisions to develop the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in compliance with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (201111012RIB and 200907056R). All participants or their legal representatives provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for consent for publication, because no individuals’ data were reported (including individual details, images, or videos) in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wen-Ching Shen, Email: wenching8@gmail.com.

Yu-Hsiang Chou, Email: chouyuhsiang@yahoo.com.tw.

Hsiang-Po Huang, Email: hh691290@gmail.com.

Jenn-Feng Sheen, Email: jfsheen@nfu.edu.tw.

Shih-Chieh Hung, Email: hung3340@gmail.comm.

Hsin-Fu Chen, Phone: 886-2-23123456, Email: hfchen@ntu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Lameire NH, Bagga A, Cruz D, De Maeseneer J, Endre Z, Kellum JA, et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet. 2013;3829887:170–179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu C-y, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordo√±ez JD, Go AS: Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;45:891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Chou YH, Huang TM, Wu VC, Wang CY, Shiao CC, Lai CF, et al. Impact of timing of renal replacement therapy initiation on outcome of septic acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2011;153:R134. doi: 10.1186/cc10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiao CC, Ko WJ, Wu VC, Huang TM, Lai CF, Lin YF, et al. U-curve association between timing of renal replacement therapy initiation and in-hospital mortality in postoperative acute kidney injury. PLoS One. 2012;78:e42952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu V-C, Wu P-C, Wu C-H, Huang T-M, Chang C-H, Tsai P-R, et al. The impact of acute kidney injury on the long-term risk of stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Nath KA, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Frank E, Caplice NM, Hebbel RP, et al. Transgenic sickle mice are markedly sensitive to renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;1664:963–972. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62318-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grams ME, Rabb H. The distant organ effects of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;8110:942–948. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahuja N, Andres-Hernando A, Altmann C, Bhargava R, Bacalja J, Webb RG, et al. Circulating IL-6 mediates lung injury via CXCL1 production after acute kidney injury in mice. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2012;3036:F864–FF72. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00025.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andres-Hernando A, Altmann C, Bhargava R, Okamura K, Bacalja J, Hunter B, et al. Prolonged acute kidney injury exacerbates lung inflammation at 7 days post-acute kidney injury. Physiological Rep. 2014;7:e12084. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumida M, Doi K, Ogasawara E, Yamashita T, Hamasaki Y, Kariya T, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics by dynamin-related protein-1 in acute cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;2610:2378–2387. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014080750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B, Cohen A, Hudson TE, Motlagh D, Amrani DL, Duffield JS. Mobilized human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells promote kidney repair after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2010;12120:2211–2220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.928796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xing L, Cui R, Peng L, Ma J, Chen X, Xie R-J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells, not conditioned medium, contribute to kidney repair after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;54:1–12. doi: 10.1186/scrt489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou YH, Pan SY, Yang CH, Lin SL. Stem cells and kidney regeneration. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;1134:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi KD, Yu J, Smuga-Otto K, Salvagiotto G, Rehrauer W, Vodyanik M, et al. Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;273:559–567. doi: 10.1002/stem.20080922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rufaihah AJ, Huang NF, Jame S, Lee JC, Nguyen HN, Byers B, et al. Endothelial cells derived from human iPSCS increase capillary density and improve perfusion in a mouse model of peripheral arterial disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;3111:e72–e79. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.230938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;1315:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuji O, Miura K, Okada Y, Fujiyoshi K, Mukaino M, Nagoshi N, et al. Therapeutic potential of appropriately evaluated safe-induced pluripotent stem cells for spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;10728:12704–12709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910106107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyohara T, Mae S-I, Sueta S-I, Inoue T, Yamagishi Y, Kawamoto T, et al. Cell therapy using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived renal progenitors ameliorates acute kidney injury in mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;49:980–992. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alev C, Ii M, Asahara T. Endothelial progenitor cells: a novel tool for the therapy of ischemic diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;154:949–965. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen WC, Liang CJ, Wu VC, Wang SH, Young GH, Lai IR, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells derived from Wharton’s jelly of the umbilical cord reduces ischemia-induced hind limb injury in diabetic mice by inducing HIF-1alpha/IL-8 expression. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;229:1408–1418. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang CJ, Shen WC, Chang FB, Wu VC, Wang SH, Young GH, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells derived from Wharton’s jelly of human umbilical cord attenuate ischemic acute kidney injury by increasing vascularization and decreasing apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Cell Transplant. 2015;7:1363–1377. doi: 10.3727/096368914X681720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Neill AC, Ricardo SD. Human kidney cell reprogramming: applications for disease modeling and personalized medicine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;249:1347–1356. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen WC, Chou YH, Lin SL. Enthusiasm for induced pluripotent stem cell-based therapies in kidney regeneration. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;8:593–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huangfu D, Osafune K, Maehr R, Guo W, Eijkelenboom A, Chen S, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;2611:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee PY, Chien Y, Chiou GY, Lin CH, Chiou CH, Tarng DC. Induced pluripotent stem cells without c-Myc attenuate acute kidney injury via downregulating the signaling of oxidative stress and inflammation in ischemia-reperfusion rats. Cell Transplant. 2012;2112:2569–2585. doi: 10.3727/096368912X636902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawai H, Yamashita T, Ohta Y, Deguchi K, Nagotani S, Zhang X, et al. Tridermal tumorigenesis of induced pluripotent stem cells transplanted in ischemic brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;308:1487–1493. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo CH, Na HJ, Lee DS, Heo SC, An Y, Cha J, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells from human dental pulp-derived iPS cells as a therapeutic target for ischemic vascular diseases. Biomaterials. 2013;3433:8149–8160. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HY, Yoo TH, Hwang Y, Lee GH, Kim B, Jang J, et al. Indoxyl sulfate (IS)-mediated immune dysfunction provokes endothelial damage in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) Sci Rep. 2017;71:3057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03130-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frangogiannis NG. Interleukin-1 in cardiac injury, repair, and remodeling: pathophysiologic and translational concepts. Discoveries (Craiova). 2015;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.de Caestecker M, Humphreys BD, Liu KD, Fissell WH, Cerda J, Nolin TD, et al. Bridging translation by improving preclinical study design in AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;2612:2905–2916. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015070832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawamoto A, Gwon H-C, Iwaguro H, Yamaguchi J-I, Uchida S, Masuda H, et al. Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2001;1035:634–637. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghaly T, Rabadi MM, Weber M, Rabadi SM, Bank M. Grom JM, et al. Hydrogel-embedded endothelial progenitor cells evade LPS and mitigate endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2011;3014:F802–FF12. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00124.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patschan D, Krupincza K, Patschan S, Zhang Z, Hamby C, Goligorsky MS. Dynamics of mobilization and homing of endothelial progenitor cells after acute renal ischemia: modulation by ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2006;2911:F176–FF85. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00454.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hohenstein B, Kuo M-C, Addabbo F, Yasuda K, Ratliff B, Schwarzenberger C, et al. Enhanced progenitor cell recruitment and endothelial repair after selective endothelial injury of the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2010;2986:F1504–F1F14. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00025.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu V-C, Young G-H, Huang P-H, Lo S-C, Wang K-C, Sun C-Y, et al. In acute kidney injury, indoxyl sulfate impairs human endothelial progenitor cells: modulation by statin. Angiogenesis. 2013;163:609–624. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atluri P, Trubelja A, Fairman AS, Hsiao P, MacArthur JW, Cohen JE, et al. Normalization of postinfarct biomechanics using a novel tissue-engineered angiogenic construct. Circulation. 2013;12811(suppl 1):S95–S104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masuda H, Tanaka R, Fujimura S, Ishikawa M, Akimaru H, Shizuno T, et al. Vasculogenic conditioning of peripheral blood mononuclear cells promotes endothelial progenitor cell expansion and phenotype transition of anti-inflammatory macrophage and T lymphocyte to cells with regenerative potential. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000743. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson J, Wu Y, Jiang X, Berretta R, Houser S, Choi E, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia suppresses bone marrow CD34+/VEGF receptor 2+ cells and inhibits progenitor cell mobilization and homing to injured vasculature—a role of β1-integrin in progenitor cell migration and adhesion. FASEB J. 2015;297:3085–3099. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-267989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hristov M, Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Liehn EA, Shagdarsuren E, Ludwig A, et al. Importance of CXC chemokine receptor 2 in the homing of human peripheral blood endothelial progenitor cells to sites of arterial injury. Circ Res. 2007;100:590-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Giordano S, Zhao X, Xing D, Hage F, Oparil S, Cooke JP, et al. Targeted delivery of human iPS-ECs overexpressing IL-8 receptors inhibits neointimal and inflammatory responses to vascular injury in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;3106:H705–HH15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00587.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rehman J, Li J, Orschell CM, March KL. Peripheral blood “endothelial progenitor cells” are derived from monocyte/macrophages and secrete angiogenic growth factors. Circulation. 2003;1078:1164–1169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000058702.69484.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zarjou A, Kim J, Traylor AM, Sanders PW, Balla J, Agarwal A, et al. Paracrine effects of mesenchymal stem cells in cisplatin-induced renal injury require heme oxygenase-1. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2011;3001:F254–FF62. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00594.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tressel SL, Kim H, Ni CW, Chang K, Velasquez-Castano JC, Taylor WR, Yoon YS, Jo H. Angiopoietin-2 stimulates blood flow recovery after femoral artery occlusion by inducing inflammation and arteriogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1989–1995. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.175463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanayasu-Toyoda TTT, Kikuchi Y, Uchida E, Matsuyama A, Yamaguchi T. Cell-surface MMP-9 protein is a novel functional marker to identify and separate pro-angiogenic cells from early endothelial progenitor cells derived from CD133<sup>+</sup> cells. Stem Cells. 2016;34:1251–1262. doi: 10.1002/stem.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santo SDFA, Periasamy R, Seiler S, Widmer HR. The cytoprotective effects of human endothelial progenitor cells conditioned medium against an ischemic insult are VEGF and IL-8 dispensable. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:735–747. doi: 10.3727/096368916X690458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Q-h T, Zeng H, Stinnett A, Yu H, Aschner JL, Liao D-F, et al. Critical role of angiopoietins/Tie-2 in hyperglycemic exacerbation of myocardial infarction and impaired angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;2946:H2547–H2H57. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01250.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen WCLC, Wu VC, Wang SH, Young GH, Lai IR, Chien CL, Wang SM, Wu KD, Chen YL. Endothelial progenitor cells derived from Wharton’s jelly of the umbilical cord reduces ischemia-induced hind limb injury in diabetic mice by inducing hif-1alpha/il-8 expression. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1408–1418. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Z, von Ballmoos MW, Faessler D, Voelzmann J, Ortmann J, Diehm N, Kalka-Moll W, Baumgartner I, Di Santo S, Kalka C. Paracrine factors secreted by endothelial progenitor cells prevent oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of mature endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park SW, Jun Koh Y, Jeon J, Cho YH, Jang MJ, Kang Y, et al. Efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into functional CD34+ progenitor cells by combined modulation of the MEK/ERK and BMP4 signaling pathways. Blood. 2010;11625:5762–5772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mae S, Shono A, Shiota F, Yasuno T, Kajiwara M, Gotoda-Nishimura N, et al. Monitoring and robust induction of nephrogenic intermediate mesoderm from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1367. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lam AQ, Freedman BS, Morizane R, Lerou PH, Valerius MT, Bonventre JV. Rapid and efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intermediate mesoderm that forms tubules expressing kidney proximal tubular markers. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;256:1211–1225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharmin S, Taguchi A, Kaku Y, Yoshimura Y, Ohmori T, Sakuma T, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived podocytes mature into vascularized glomeruli upon experimental transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;6:1778–1791. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto M, Cui L, Johkura K, Asanuma K, Okouchi Y, Ogiwara N, et al. Branching ducts similar to mesonephric ducts or ureteric buds in teratomas originating from mouse embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2006;2901:F52–F60. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00001.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Characterization of human iPS cell-derived endothelial progenitor cells (iEPCs). Figure S2 Characterization of human iPS cell-derived endothelial progenitor cells (iEPCs). Figure S3 GFP-iEPC sorting. Representative flow cytometric analyses for (A) control iPS cells and (B) lentivirus-GFP-transduced iPS (GFP-iPS) cells. Figure S4 Gross appearance of kidneys with sham or AKI. Figure S5 Measurement of human angiogenesis-related proteins in the plasma of AKI mice. Figure S6 Increased plasma levels of brain natriuretic peptide in AKI patients. (DOC 7402 kb)

Data Availability Statement

For data requests, please contact the author.