Abstract

EUS is most commonly used to evaluate and sample lesions of the abdomen but has only been used on rare occasions to evaluate and sample lung lesions. Prior reported cases of EUS sampling of lung lesions were performed by fine-needle aspiration. We present what is believed to be the first reported cases of EUS-guided core biopsy of intraparenchymal lung lesions through two separate case reports. Both patients had the upper lobe lesions not amenable to bronchoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound, and both patients underwent core biopsy without adverse event. This report of two cases shows that EUS-guided core biopsy of intraparenchymal lung lesions is technically possible and may not necessarily result in adverse events such as hemorrhage, pneumothorax, or infection.

Keywords: Core biopsy, EUS, FNA, FNB, lung cancer, lung mass, tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

EUS is most commonly used to diagnose and stage solid and cystic lesions of the abdomen but has been used on rare occasions to evaluate and sample lung lesions. Prior reported cases of EUS sampling of lung lesions were performed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA). We present what is believed to be the first reported description of EUS-guided core biopsies of intraparenchymal lung lesions in two separate patients.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1

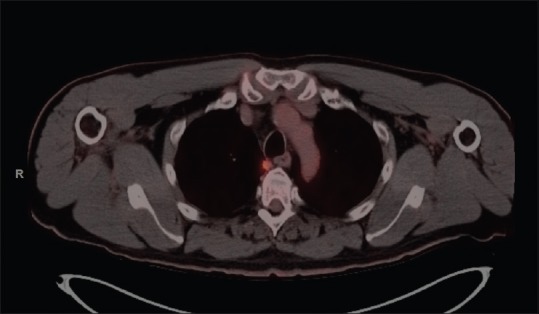

A 66-year-old male patient with a 60 pack-year smoking history and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease underwent a screening computed tomography (CT) for lung cancer. This revealed a 0.9 cm × 1.1 cm subpleural nodule in the medial right upper lobe (RUL) near the esophagus. A follow-up positron emission tomography scan performed 1 month later revealed a spiculated nodule in the medial RUL lung at the location of the prior lesion. On the follow-up imaging, the mass was felt to have increased in size and now measured 14 mm × 10 mm [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography image of the right-sided lung lesion in patient 1. Note that the lesion is not in contact with the esophagus but is within the lung itself

Interventional pulmonology was consulted but did not felt that they could reach the lesion through either routine bronchoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS). The interventional gastrointestinal (GI) team was consulted regarding possible transesophageal biopsy through EUS.

Radial and linear EUS was performed at 7.5MHz with Doppler. An irregular mass was identified endosonographically involving the right lung abutting the pleura with the ultrasound probe positioned 25 cm from the incisors. With gentle compression, the esophagus could be moved into close apposition of the lesion. The mass was hypoechoic. The mass measured 10 mm × 15 mm in maximal cross-sectional diameter. The endosonographic borders were well defined [Figure 2]. Fine-needle biopsy was performed. Color Doppler imaging was utilized before needle puncture to confirm a lack of significant vascular structures within the needle path. Two passes were made with the 25G ultrasound biopsy needle (FNB) (Acquire Needle, Boston Scientific, Natick MA) using a transesophageal approach [Figure 3]. A visible core of tissue was obtained. Final pathology report was consistent with non-small cell lung carcinoma [Figure 4]. The patient was referred to oncology for evaluation and treatment.

Figure 2.

Linear EUS image of the right lung lesion in patient 1

Figure 3.

Twenty-five-gauge core biopsy needle in the right lung lesion through transesophageal approach in patient 1

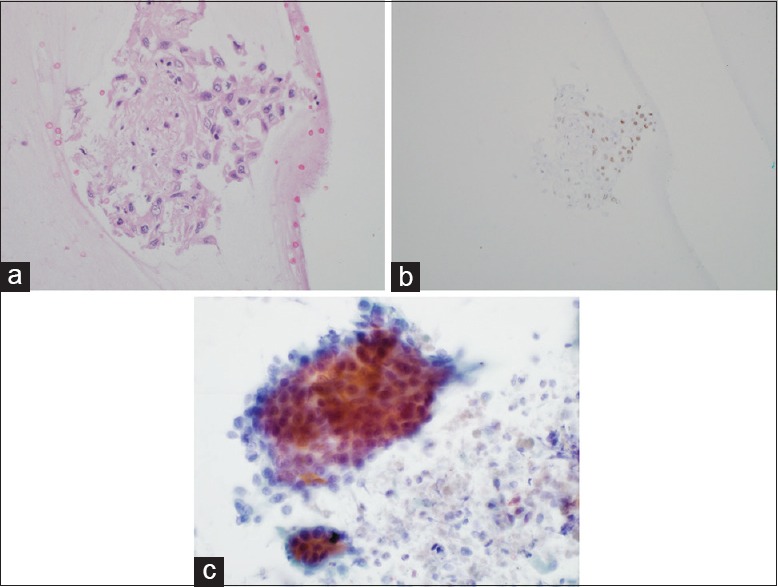

Figure 4.

(a) High-power image of an H + E stain performed on the cell block showing a cluster of malignant-appearing epithelial cells. These cells have moderate cytoplasm, morphologically consistent with non-small cell lung carcinoma. ×40 (b) Medium power image of a p63 immunostain (marker of squamous differentiation) showing the same cluster on the cell block. The patchy nuclear staining is equivocal. ×20. (c) High-power image from the Papanicolaou-stained squash, cytology preparation. The cohesive, malignant epithelial cells with moderate, dense cytoplasm are consistent with non-small cell lung carcinoma. ×40

Patient 2

A 60-year-old male patient with a history of prostate cancer and prior prostatectomy, a 20 pack-year smoking history, a positive purified protein derivative test in 1994 without treatment and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine presented with 2 months of productive cough, weight loss, and night sweats. A CT chest revealed a 4 cm × 4 cm RUL cavitary lung lesion with enlarged right-sided paratracheal and the right hilar lymph nodes. A 4 cm × 6 cm spiculated mass was noted in the left upper lobe (LUL) directly abutting the aortic arch [Figure 5]. Sputum cultures were positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Figure 5.

Computed tomography scan of the left-sided lesion in patient 2

The patient was started on rifampin isoniazid pyrazinamide ethambutol therapy. Interval CT chest showed a decrease in size of the RUL cavitary lesion, the right-sided paratracheal, and the right hilar lymph nodes. The LUL periaortic spiculated lung mass remained grossly unchanged measuring 6.5 cm × 4.0 cm and was felt to be concerning for malignancy.

Interventional pulmonology team was consulted for biopsy of the LUL mass, but they felt this was not technically feasible. Interventional GI was asked to perform EUS-guided transesophageal biopsy. The lesion was adjacent to the esophagus and closely related to the aortic arch.

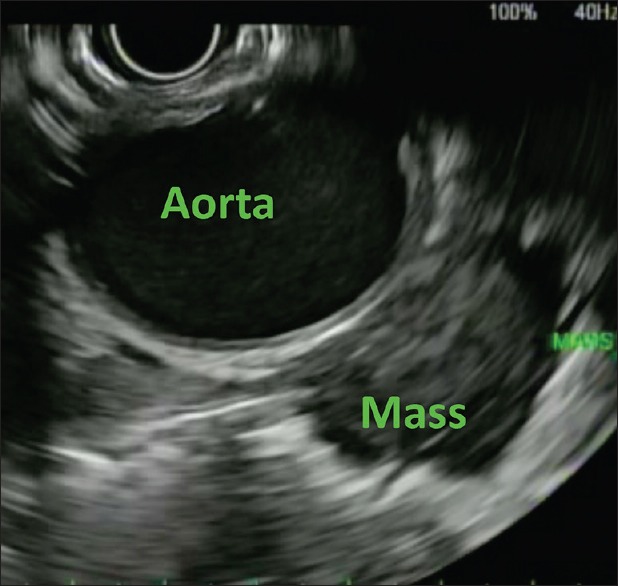

Transesophageal EUS-guided biopsy was performed using a linear echoendoscope that showed a well-defined mass in the left lung apex at some distance from the esophagus [Figure 6]. The mass was hypoechoic and heterogeneous in echotexture with well-defined borders. The mass was closely related to the aortic arch but with a discrete tissue plane in-between. Fine-needle core biopsy was performed using both a 22G and 25G Acquire EUS biopsy needles. Four core samples were obtained [Figure 7]. Postprocedure chest X-ray was normal with no evidence of pneumothorax. There were no adverse events. Biopsy results showed fragments of hyalinized dense fibrous tissue with entrapped atypical cells, there was no evidence of malignancy in the sample. The patient was offered repeat EUS-FNB, but he preferred outpatient follow-up with interval imaging and has done well thereafter.

Figure 6.

EUS image of lesion in patient 2

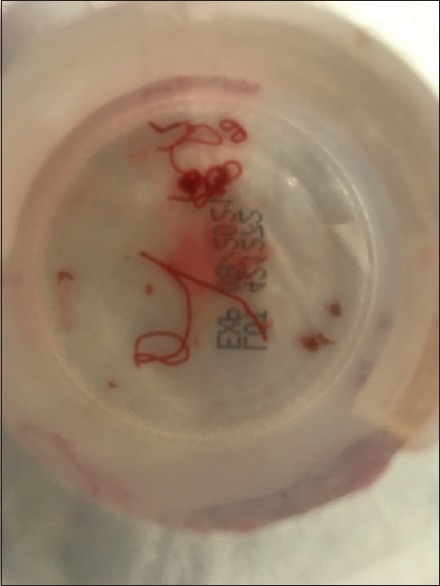

Figure 7.

Core biopsy sample obtained from patient 2

DISCUSSION

EUS has been and remains a powerful platform for the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of a plethora of GI conditions. While still most commonly used to evaluate biopsy, and treat diseases of the luminal GI tract and pancreas, it has been recognized for many years that the reach of EUS extends to extraintestinal targets. Historically, in patients with primary pulmonary disease EUS with FNA was most commonly used to biopsy mediastinal lymph nodes or other locations, where metastases were felt to be present such as the adrenal glands or pancreas.[1,2,3,4]

Biopsies of lesions within the lung have generally been performed by interventional pulmonologists, interventional radiologists, and thoracic surgeons. Endobronchial lesions are routinely biopsied by bronchoscopy.[5] Parenchymal lesions can be biopsied through EBUS, either using FNA needles or biopsies through sheath.[6,7] The literature in this regard is also somewhat sparse but shows encouraging efficacy and safety.[8,9]

Some lesions, such as in our patients, are difficult to reach by either bronchoscopy or EBUS. CT-guided biopsy and surgical biopsy are valid approaches in some patients in this situation. If the lesion is in close to the lumen of the GI tract EUS-guided biopsy can be considered, although in practice this procedure is performed rarely. Concerns about infection, pneumothorax, and intrapulmonary hemorrhage may be factors limited the spread of this technique. Many endosonographers likely receive no training in performing EUS-FNA of intraparenchymal lung lesions.

The literature regarding EUS-guided sampling of true intraparenchymal lung lesions is sparse and is confined to the use of FNA, rather than FNB needles. Representative papers include small number of patients. Dincer et al. reported five patients who underwent EUS-FNA of pulmonary nodules or masses.[10] Bugalho reported on 123 patients underwent evaluation of pulmonary lesions and included eight patients who underwent EUS-guided FNA.[11] Annema reported on 31 patients with periesophageal lung lesions who underwent EUS-FNA with a high diagnostic yield and no adverse events.[12] Larghi et al. reported on a single patient with a pleural metastasis of endometrial cancer who was diagnosed through transesophageal EUS-FNA.

Both of our patients underwent EUS-guided FNB in an attempt to obtain tissue cores and a greater overall amount of tissue for diagnostic pathologic evaluation, and to retain enough extra tissue should special stains or molecular testing be needed at a later time. In both of our cases, there was some degree of physical separation between the lung lesion and the esophagus, but this could be bridged by an FNB needle.

No specific guidelines exist regarding procedures for performing EUS-guided FNB of intraparenchymal lung lesions. In both of our cases, postprocedure chest X-rays were obtained to rule out pneumothorax. Both patients in our experience did not have symptoms of pneumothorax, and it is unknown if post-FNB chest X-rays should be performed in the absence of symptoms, although if negative they can provide additional reassurance before discharging patients. Risks of pneumothorax and intraparenchymal bleeding exist for both bronchoscopic and EUS-guided needle biopsies, but this was not seen in our patients who underwent FNB with 22- and 25-gauge needles.

EUS-guided FNB has recently emerged as an alternative tissue acquisition technique to FNA. FNB potentially allows for more tissue to be obtained, histologic analysis (as opposed to cytologic analysis) and the prospect of more tissue being available for special stains personalized medicine testing.[13,14,15] Disadvantages of FNB vs. FNA at this time include higher cost and a theoretical increase in the risk of bleeding or local tissue injury from different types of needle tips; although no firm evidence till date exists for this latter concern. It is also possible that core needle tips could increase the risk of pneumothorax or other adverse events when performing biopsies of lung lesions; although, we did not see this in our patients.

Overall, this report of two cases shows that EUS-guided core biopsy of intraparenchymal lung lesions is technically possible and may not necessarily result in adverse events such as hemorrhage, pneumothorax, or infection. Of note, in both cases, the lesion was not in direct contact with the esophageal wall, showing that this is not mandatory for tissue sampling. Additional study of core biopsies in this setting is worth undertaking as not all lung lesions can be reached by standard bronchoscopy or EBUS and EUS offers a minimally invasive platform for tissue acquisition.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ardengh JC, Lopes CV, Kemp R, et al. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the suspicion of pancreatic metastases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Layfield LJ, Hirschowitz SL, Adler DG. Metastatic disease to the pancreas documented by endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration: A seven-year experience. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:228–33. doi: 10.1002/dc.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crombag LM, Szlubowski A, Stigt JA, et al. EUS-B-FNA vs. conventional EUS-FNA for left adrenal gland analysis in lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2017;108:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eloubeidi MA, Beydoun M, Jurdi N, et al. Transduodenal EUS-guided FNA of the right adrenal gland to diagnose lung cancer where percutaneous approach was not possible. J Med Liban. 2011;59:173–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ost DE, Ernst A, Lei X, et al. Diagnostic yield and complications of bronchoscopy for peripheral lung lesions. Results of the AQuIRE registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:68–77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1332OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahidi MM, Herth F, Yasufuku K, et al. Technical aspects of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:816–35. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurimoto N, Miyazawa T, Okimasa S, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography using a guide sheath increases the ability to diagnose peripheral pulmonary lesions endoscopically. Chest. 2004;126:959–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinfort DP, Farmer MW, Irving LB, et al. Pulmonologist-performed per-esophageal needle aspiration of parenchymal lung lesions using an EBUS bronchoscope: Diagnostic utility and safety. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2017;24:117–24. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco J, Monclou E. Transesophageal endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:418–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dincer HE, Gliksberg EP, Andrade RS. Endoscopic ultrasound and/or endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of central intraparenchymal lung lesions not adjacent to airways or esophagus. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:40–3. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.151332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugalho A, Ferreira D, Eberhardt R, et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for accessible lung cancer lesions after non-diagnostic conventional techniques: A prospective study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annema JT, Veseliç M, Rabe KF. EUS-guided FNA of centrally located lung tumours following a non-diagnostic bronchoscopy. Lung Cancer. 2005;48:357–61. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMaio CJ, Kolb JM, Benias PC, et al. Initial experience with a novel EUS-guided core biopsy needle (SharkCore): Results of a large North American multicenter study. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E974–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-112581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adler DG, Witt B, Chadwick B, et al. Pathologic evaluation of a new endoscopic ultrasound needle designed to obtain core tissue samples: A pilot study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:178–83. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.183976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witt BL, Adler DG, Hilden K, et al. A comparative needle study: EUS-FNA procedures using the HD ProCore(™) and EchoTip(®) 22-gauge needle types. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:1069–74. doi: 10.1002/dc.22971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]