Abstract

ProP is a member of the major facilitator superfamily, a proton-osmolyte symporter, and an osmosensing transporter. ProP proteins share extended cytoplasmic carboxyl terminal domains (CTDs) implicated in osmosensing. The CTDs of the best characterized, group A ProP orthologs, terminate in sequences that form intermolecular, antiparallel α-helical coiled coils (e.g., ProPEc, from Escherichia coli). Group B orthologs lack that feature (e.g., ProPXc, from Xanthomonas campestris). ProPXc was expressed and characterized in E. coli to further elucidate the role of the coiled coil in osmosensing. The activity of ProPXc was a sigmoid function of the osmolality in cells and proteoliposomes. ProPEc and ProPXc attained similar activities at the same expression level in E. coli. ProPEc transports proline and glycine betaine with comparable high affinities at low osmolality. In contrast, proline weakly inhibited high-affinity glycine-betaine uptake via ProPXc. The KM for proline uptake via ProPEc increases dramatically with the osmolality. The KM for glycine-betaine uptake via ProPXc did not. Thus, ProPXc is an osmosensing transporter, and the C-terminal coiled coil is not essential for osmosensing. The role of CTD-membrane interaction in osmosensing was examined further. As for ProPEc, the ProPXc CTD co-sedimented with liposomes comprising E. coli phospholipid. Molecular dynamics simulations illustrated association of the monomeric ProPEc CTD with the membrane surface. Comparison with the available NMR structure for the homodimeric coiled coil formed by the ProPEc-CTD suggested that membrane association and homodimeric coiled-coil formation by that peptide are mutually exclusive. The membrane fluidity in liposomes comprising E. coli phospholipid decreased with increasing osmolality in the range relevant for ProP activation. These data support the proposal that ProP activates as cellular dehydration increases cytoplasmic cation concentration, releasing the CTD from the membrane surface. For group A orthologs, this also favors α-helical coiled-coil formation that stabilizes the transporter in an active form.

Introduction

Osmoregulatory systems control transmembrane water fluxes to mitigate the impacts of environmental osmotic pressure variations on prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (1). Osmotic downshocks trigger solute release via mechanosensitive channels to avoid cell lysis; conversely, increasing osmotic pressure triggers osmolyte uptake via osmosensing transporters to avoid dehydration. Studies of bacterial channel MscL established the “force from lipid principle” that mechanosensitive channels open as membrane tension increases in response to mechanical stress transmitted via phospholipid, not via the cytoskeleton or other proteins (2). We aim to understand how osmotically induced cell dehydration activates osmolyte uptake via osmosensing transporters (3, 4).

ProPEc is an osmosensing transporter, an H+ symporter, and a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) member that imports diverse osmolytes into Escherichia coli (4). The substrates of ProPEc include proline, glycine betaine, ectoine, choline, and dimethylsulfoniopropionate (5). Like ProPEc, glycine-betaine-specific transporters BetP from Corynebacterium glutamicum (an Na+ symporter and betaine carnitine choline transporter family member) and OpuA from Lactococcus lactis (an adenosine triphosphate binding cassette transporter) serve as experimental models for the study of osmosensing (4, 6).

Osmotically induced dehydration alters many cellular properties simultaneously: turgor pressure decreases; cell wall and cytoplasmic membrane strain change; and the concentration of each cytoplasmic solute, the collective concentration of cytoplasmic ions, and the crowding of cytoplasmic molecules all increase (7). The activity of each osmosensing transporter is a sigmoid function of the osmolality in cells and, after purification and reconstitution, in proteoliposomes (PRLs) that reproduce the proteins’ cellular orientations (8, 9, 10). Thus, PRLs were exploited to identify the cellular properties to which the transporters respond (4, 6, 11). Whole-cell and PRL data indicate that the activities of ProPEc, BetP, and OpuA are not determined by turgor pressure or membrane tension (12). Incorporation of large polymers (e.g., poly(ethylene)glycols, bovine serum albumin) in the PRL lumen facilitates the osmotic activation of ProPEc (13, 14) and OpuA (15), suggesting that macromolecular crowding plays a role in osmosensing. However, inorganic ions were identified as the primary determinants of osmosensing transporter activity (3, 16).

ProPEc, BetP, and OpuA attain the same activity when the same osmolality is imposed externally with diverse, membrane-impermeant electrolytes and nonelectrolytes (3). In contrast, all three transporters activate with increasing concentration of inorganic ions, but not of neutral solutes, in the PRL lumen (3). In each case, a high luminal salt concentration (0.2–0.4 M) is required to elicit transporter activity, and that concentration requirement increases further with the proportion of anionic lipids in both cells and PRLs (10, 17, 18). Activation of ProPEc is not ion-specific; the apparent ion specificities of BetP (particularly K+) and OpuA may arise from secondary ion effects on energy coupling.

The activation of ProPEc was described by a thermodynamic, two-state model (Eq. 1) (16):

| (1) |

Accordingly, the relative transporter activity (A/Amax) would be a measure of the fraction (f) of transporters in the active conformation (ProPA). Here, A is the initial rate of proline uptake at each osmolality, Amax is the maximal initial rate at high osmolality, and f is A/Amax. Then Kobs is equal to f/(1 − f). In turn, salt effects on biomolecular processes can be approximated by Eq. 2 (19):

| (2) |

where Kobs is the equilibrium constant for the process when the salt concentration is C, R is the gas constant, and T is the Kelvin temperature. SKobs quantifies the Coulombic effect of luminal salt on lnKobs, mG/RT quantifies the Hofmeister effect of luminal salt on lnKobs (mG is the derivative of the observed standard free-energy change for the process with respect to salt concentration at high salt concentration, at which Coulombic effects are negligible), and K0 is equal to the extrapolated value of Kobs at C = 1 M salt for a salt exhibiting no net Hofmeister effect (mG = 0) (20). For most processes, Coulombic effects of salts are dominant at low (submolar) concentrations, and Hofmeister effects are dominant at high concentrations (20). Analyses of proline uptake via ProPEc in PRLs loaded with various salts suggested that the contribution of the Hofmeister effect to the osmotic activation of ProPEc is negligible. Rather, the osmotic activation of ProP is a Coulombic effect of increasing luminal cation concentration and not site-specific cation binding (3, 16). ProPEc activity followed the (combined) relationship (Eq. 3):

| (3) |

where [M+] is the luminal cation concentration at each osmolality, K0 is the equilibrium constant for the transition between inactive ProPI and active ProPA at the osmolality where [M+] is 1, and SKobs quantifies the Coulombic effect of luminal cations on lnKobs. The osmotic activation of ProPEc was not cation-specific, but K+ is the predominant cation physiologically. This analysis further suggested that anionic functional groups cluster as ProPI transitions to ProPA with increasing cation concentration. This clustering may be associated with the folding of anionic, cytoplasmic ProPEc domains; with an increase in the local membrane surface charge density; and with the juxtaposition of anionic protein and membrane surfaces.

Extended, cytoplasmic carboxyl terminal domains (CTDs) have been implicated in osmosensing for ProPEc, BetP, and OpuA (21, 22, 23). These CTDs are not structurally related, but models for osmosensing by each transporter incorporate osmotically induced changes to CTD-membrane interaction. Two groups of ProP orthologs, differentiated by their CTD structures, are osmosensing transporters (12). Paired CTDs of group A transporters such as ProPEc form intermolecular, antiparallel, α-helical coiled coils in vivo and in vitro (21, 24), whereas the shorter CTDs of group B transporters lack coiled-coil heptads (Fig. 1). In addition, a peptide corresponding to the ProPEc CTD binds liposomes comprising a polar lipid extract from E. coli, and amino acid replacements that affect osmosensing also perturb that membrane interaction (25).

Figure 1.

Aligned sequences of the CTDs of ProP orthologs and paralogues. The sequences of the cytoplasmic CTDs of the ProP orthologs from E. coli (ProPEc), D. didantii (ProPDd, Q_47421), A. tumefaciens (ProPAt, NP_356328), X. campestris (ProPXc, NP_635478), and C. glutamicum (ProPCg, CAA_73136) are aligned with those of the closest ProP paralogues that are known not to be osmoregulatory transporters (shikimate transporter ShiA (12) (NP_416488) and α-ketoglutarate transporter KgtP (AAC_75640), both from E. coli). Residue 438 of ProPEc is intramembrane (64). Structural predictions: a–g, coiled-coil heptads (81); bold, known coiled coil (44); H, α-helix; S, β-strand (82). Acidic residues are in red, and basic residues are in blue. To view this figure in color, go online.

This work further explored the role of ProP CTD-membrane interactions in osmosensing. First, ProPEc was compared with ProPXc (from Gram-negative plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris). ProPEc (group A) and ProPXc (group B) are similar in sequence (51% identity) and have similar native phospholipid environments. The membranes of E. coli and X. campestris include significant proportions of zwitterionic lipids (phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), lysophosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylserine (PS) (lysophosphatidylethanolamine and PS in X. campestris only)) and anionic lipids phosphatidylglycerol (PG), cardiolipin, and phosphatidylinositol (present in X. campestris only) (26). ProPXc was shown to be an osmosensing transporter: its activity was a sigmoid function of the osmolality in cells and, after purification and reconstitution, in PRLs.

Second, the CTD-membrane interaction was further characterized. As for ProPEc (25), a peptide replica of the ProPXc CTD bound liposomes composed of E. coli phospholipids. Thus, the C-terminal coiled coil is not essential for osmosensing or membrane interaction of the ProPXc CTD. Comparison of the available NMR structure for the homodimeric coiled coil formed by the ProPEc-CTD with molecular dynamics simulations of the monomeric peptide-membrane interaction predicted that coiled-coil formation and membrane association of the monomeric ProPEc CTD are mutually exclusive. Further, transporter activation was correlated with a decrease in membrane fluidity. Taken together, these data support a new structural model in which the CTDs of group A orthologs play a dual role in osmosensing and the osmotic activation of ProP.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). Restriction endonucleases and alkaline phosphatase were from New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). X. campestris pathovar campestris ATCC 33913 genomic DNA was from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Bovine pancreatic DNase I (type II) was from Boehringer-Mannheim (Laval, Quebec, Canada) and Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Egg white lysozyme (UltraPure grade) was from Caledon Laboratories (Georgetown, Ontario, Canada) and Sigma-Aldrich. Choline oxidase from Alcaligenes sp. was from Sigma. Ampicillin, imidazole, and β-mercaptoethanol were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated anti-PentaHis antibody and nickel nitrilotriacetate resin were from Qiagen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Solution osmolalities were measured with a Wescor (Logan, UT) vapor pressure osmometer. L-[3H]-glycine betaine (glycine-2-3H, catalog number ART 1896, specific activity 1480 GBq/mmol) and L-[14C]-glycine betaine (glycine-1-14C, catalog number ARC 0748, specific activity 2.04 GBq/mmol) were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Alternatively, radiolabeled glycine betaine was synthesized as described (27) by the enzymatic oxidation of [Methyl-3H]-choline chloride (catalog number NET109001MC, specific activity 2897 GBq/mmol; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). L-[14C(U)]-Proline (catalog number NEC285E250UC, specific activity 9.25 GBq/mmol) was from Perkin Elmer.

Culture media and growth conditions

Bacteria were cultivated at 37°C in Luria Bertani LB medium (28) or in NaCl-free 3-morpholinpropane-1-sulfonic acid (MOPS) medium, a variant of the MOPS medium described by Neidhardt et al. (29) from which all NaCl had been omitted. This base medium was supplemented with NH4Cl (9.5 mM) as a nitrogen source and glycerol (0.4% (v/v)) as a carbon source. L-tryptophan (245 μM) and thiamine hydrocholoride (1 μg/mL) were added to meet auxotrophic requirements, creating a complete growth medium with an osmolality of 0.14–0.15 mol/kg. NaCl was added as required to further modulate the medium osmolality. Ampicillin (100 μg/mL) was added as required to maintain plasmids. Arabinose was added as specified to modulate proP gene expression from the araBAD promoter of plasmids based on vector pBAD24.

Bacteria, plasmids, and molecular biological manipulations

E. coli K-12 derivatives DH5α (30) (F− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk−) supE44λ− thi-1 gyrA relA1), WG350 (31) (F− trp lacZ rspL thi Δ(put PA)101Δ(proU)600 Δ(proP-melAB)212), and E. coli B strain BL21 Gold (F− ompT hsdS (rB− mB−) dcm+ Tetr gal endA The) were used for this study. Plasmids and oligonucleotides are listed in Tables S1 and S2. Molecular biological procedures were performed as described (32). Recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α (30) and subsequently transferred to E. coli WG350 as described (30). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed essentially according to the Stratagene Quik Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis procedure with Pwo DNA polymerase from Roche Applied Science (Laval, Quebec, Canada) and DpnI restriction endonuclease from New England Biolabs (33). Plasmid sequences were verified by the Advanced Analysis Centre at the University of Guelph (Guelph, Ontario, Canada).

In E. coli, both proP expression and ProP activity are osmoregulated (34). To focus on the osmoregulation of transporter activity in vivo, genes encoding the ProP orthologs were expressed in an osmolality-independent manner from the AraC-controlled araBAD promoter of plasmids derived from vector pBAD24 (35). To create pDM4, the gene encoding ProPXc was synthesized with optimal codon usage for E. coli and inserted into vector pBAD24 via flanking NheI and HindIII restriction sites (Genscript (Piscataway, NJ)). The sequences of the native and codon-optimized proPXc open reading frames are aligned in Fig. S1. Plasmids pDM4 (encoding ProPXc), pDC79 (21) (encoding ProPEc), pYT13 (36) (encoding ProPAt (from Agrobacterium tumefaciens)), and pYT12 (36) (encoding ProPCg (from C. glutamicum)) were introduced to E. coli WG350, which lacks proline transporters PutP, ProP, and ProU (31). Site-directed mutagenesis, employing primers listed in Table S2, was used to create plasmids encoding His10-ProPEc (pDC340 from pYT1 (36)), His10-ProPEcΔ11 (pDC342 from pMD3 (36)), His10-ProPEcΔ18 (pDC341 from pMD2 (36)), and His10-ProPXc (pDC326 from pDM4).

Plasmids encoding MalE∗ and MalE∗ProPXcCTD were constructed from expression vector pMalp2 (37, 38) as follows. Plasmid pDC369, encoding MalE∗, was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using pMALp2 as template for primers pMALStop and pMalStop-r. pDC369 is identical to pMALp2 except that a STOP codon replaces the isoleucine codon after the sequence encoding the Factor Xa recognition site (IEGR). Plasmid pDC361, encoding MalE∗ProPXcCTD, was constructed by amplifying the oligonucleotide encoding the ProPXc CTD (R446–A496) using pDM4 as the template with primers ProPXcR446 and ProPXcHindIII. The 174 nucleotide PCR product was digested with NruI and HindIII and ligated with pMALp2 that had been digested with XmnI and HindIII.

Transport assays: Intact cells

Published procedures were used to cultivate bacteria in NaCl-free MOPS medium and measure initial rates of proline or glycine-betaine uptake (14). Radiolabeled proline and glycine betaine were provided at concentrations of 0.2 and 0.1 mM, respectively, unless otherwise indicated. To detect the inhibition of radiolabeled substrate uptake by unlabeled substrate analogs, a 30 μL aliquot of the E. coli cell suspension was added to 546 μL of substrate-free transport assay medium and incubated for 3 min in a 25°C shaking water bath. Substrate uptake was then initiated by adding a 480 μL aliquot of that mixture to an assay tube containing 20 μL of the radiolabeled substrate plus a 10 μL aliquot of the unlabeled analog. For assays with L-[3H]-glycine betaine as substrate, the filters were not dried, and Filtron-X solution (Diamed (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada)) replaced 2,5-diphenyloxazole-supplemented xylenes as the scintillation fluid. Transport assay media were adjusted to the indicated osmolalities with NaCl. The protein concentration of cell suspensions was determined with the bicinchoninic acid assay (39, 40) with bovine serum albumin as standard. All transport measurements were performed in triplicate on at least two separate days. Unless otherwise stated, figures show representative means and standard errors of the mean for triplicate assays performed on 1 day. Where indicated, the initial rate of proline uptake (A) attained by cells at a particular medium osmolality (Π/RT) was fit to Eq. 4

| (4) |

by nonlinear regression performed with SigmaPlot 12.5. Amax is the uptake rate that would be observed at high osmolality, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, Π1/2/RT is the medium osmolality yielding half-maximal activity, and B is a constant inversely proportional to the slope of the response curve.

The expression levels of ProP variants were determined by conducting Western blots on whole-cell extracts using peroxidase-conjugated anti-PentaHis antibodies (Qiagen) or rabbit anti-ProPEc primary antibodies (21) with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG as secondary antibody (catalog number A6154; Sigma), as previously described (21). Densitometric analysis of Western blots was performed with ImageJ (41).

PRL preparations and transport assays

Liposomes were prepared as described (8) from a polar lipid extract from E. coli (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) with 0.5 mM K EDTA and 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Strains WG1507 (encoding His10-ProPXc) and WG710 (encoding ProPEc-His6) were cultivated in MOPS medium (for His10-ProPXc) or LB medium (for ProPEc-His6), the proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni(nitrilotriacetate) resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and PRLs were prepared in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) with 0.5 mM K EDTA and 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Initial rates of proline or glycine-betaine uptake at room temperature were measured in duplicate as previously described (8, 14, 42) using 3H-labeled L-proline (ProPEc) or glycine betaine (ProPXc) as substrate (0.2 mM, 2.35 GBq/mmol) and sorbitol to adjust the osmolality of the assay medium. The osmotic activation parameters were obtained by fitting the resulting data to Eq. 3 (16) (see Introduction) by nonlinear regression performed with SigmaPlot 12.5.

Protein purification and liposome binding assays

Proteins MalE∗ and MalE∗ProPXcCTD were purified from transformants of E. coli strain DH5α (30) containing plasmid pDC369 and pDC361, respectively. LB medium (1 L in a 4 L Fernbach flask, supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and D-glucose (11 mM)) was inoculated with 50 mL of a culture of the relevant E. coli strain in ampicillin-supplemented LB. The culture was incubated at 37°C with shaking (200 rotations per minute) for 1–1.5 h. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (1 mM) was added, and the incubation was continued at 25°C for 4 h. The proteins were purified from periplasmic extracts by affinity chromatography using Amylose resin (catalog number E80215; New England Biolabs) according to the vendor’s instructions for the purification of periplasmic proteins. The molecular weights of the intact, purified proteins were determined using an Agilent UHD 6530 Q-ToF electrospray mass spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) at the Mass Spectrometry Facility of the Advanced Analysis Centre, University of Guelph. The instrument was configured with the standard electrospray ionization source and operated in positive-ion mode. Data analysis was performed using the MassHunter Qualitative Analysis version B.08.00 (Agilent) software. Deconvolution of the m/z spectrum was achieved using the pMod algorithm within BioConfirm software (Agilent).

Liposomes were prepared as described above (PRL Preparations and Transport Assays), and peptide binding to the liposomes was determined with a previously described sedimentation assay (25), except that protein samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting, as described above (Transport Assays: Intact Cells).

Simulation of the structure and membrane interaction of the ProPEc CTD

The structure of the CTD of ProPEc (residues K439–E500) and its interaction with a membrane that comprised palmitoyl (16:0)/palmitoleoyl (16:1) phosphatidylethanolamine (80 mol%) and palmitoyl (16:0)/palmitoleoyl (16:1) phosphatidylglycerol (20 mol%) were simulated as follows. A homology model for the monomeric peptide ProPEc439–500 was prepared with Modeler (43). The NMR structure of the coiled-coil dimer of ProPEc residues 468–497 (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 1R48) (44) was used as a template. Specifically, helix A and helix B of the NMR structure were used as templates to model residues 468–497 and residues 454–483, respectively. No template was available and no secondary structure was predicted for the loop extending from K439 to A453. The all-atom peptide system was generated using CHARMM-GUI (45, 46, 47) and simulated with NAMD (48) using the CHARMM36 force field (49). The peptide structure was simulated in 0.5 M KH2PO4 or KCl, and snapshots were taken after 25, 50, 75, and 100 ns. The resulting peptide structures were extracted from solution and aligned with the membrane surface using the Positioning of Proteins in Membrane 2.0 web server (50). The structure that gave the most negative solvent-membrane transfer free energy was selected (−8.3 kcal/mol; derived from a snapshot taken after 75 ns of simulation in 0.5 M KCl). The all-atom peptide-membrane system was generated using CHARMM-GUI with Membrane Builder (51, 52, 53) and simulated for 100 ns in 0.25 M KCl at 298.15 K with NAMD using the CHARMM36 force field (49, 54). The simulated system included two copies of the peptide (one on each side of the membrane), 128 palmitoyl (16:0)/palmitoleoyl (16:1) phosphatidylethanolamine and 32 palmitoyl (16:0)/palmitoleoyl (16:1) phosphatidylglycerol in each membrane leaflet, 22,094 water molecules, 153 K+ ions, and 77 Cl− ions. Images were generated using VMD (55).

Estimation of membrane fluidity: DPH fluorescence anisotropy

Liposomes were fabricated from 100 mg of an E. coli polar lipid extract (Avanti Polar Lipids) by detergent dialysis in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM EDTA as described by Racher et al. (8). Diphenylhexatriene (DPH) fluorescence anisotropy was measured as described by Lentz (56). DPH (in dimethylformamide) was added to the 2 mL liposome suspension after dialysis to attain a final concentration of 26.1 mM, and the samples were equilibrated at 4°C overnight in the dark. Liposomes were stored as aliquots in liquid nitrogen and prepared for use by extrusion 21 times through a polycarbonate membrane (Nucleopore, 0.2 μm pore size).

Liposomes (10 μL) were added to 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM EDTA (1 mL) supplemented with NaCl or sorbitol to attain the desired osmolality, and the resulting luminal K+ concentration was calculated with the assumption that liposomes behave as ideal osmometers (42). The fluorescence intensity was measured with a PTI QuantaMaster QM-8 steady state fluorimeter (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) at a temperature of 25°C unless otherwise indicated. Data were collected as time-based measurements with excitation wavelength 360 nm, emission wavelength 428 nm, and slit widths 6 nm over a period of 10 s, and the fluorescence at zero time was determined by linear extrapolation. Duplicate samples were analyzed, and each experiment was performed twice. Fluorescence was analyzed according to Eq. 5:

| (5) |

where I is the background-corrected emission intensity, the first subscript is the orientation of the excitation polarizer and the second subscript is the orientation of the emission polarizer. G is an instrument-specific correction factor (G = Ihv/Ihh). This equation represents the fraction of emitted light that is linearly polarized so that an increase in membrane fluidity would correspond to a decrease in R.

Estimation of membrane lateral pressure: Excimer fluorescence of dipyrenyl lipids

Liposomes were fabricated, stored, and prepared for experiments, and experiments were performed as described above, except that 1 mg of 1,2-bis-(1-pyrenehexanoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (10-DipyPC) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was dissolved with 10 mg of the E. coli polar lipid extract to yield a final fluorophore concentration of 0.8 mol%. Fluorescence was measured as described above with an excitation wavelength of 347 nm and slit widths of 2 nm. Monomer and excimer emission intensities were monitored at 377 and 477 nm, respectively. The excimer/monomer fluorescence emission intensity ratio (η) was calculated after buffer background subtraction, as described by Templer et al. (57). The relative fluorescence intensities at both wavelengths were linear functions of the quantity of liposomes added to the assay mixture, and the same value of η was obtained with the fluorophore present at 0.8 or 0.1 mol% lipid. Thus, the assays detected intramolecular (not intermolecular) excimer formation, and they were not affected by inner-filter effects. Duplicate samples were analyzed, and each experiment was performed twice.

Results

ProPXc is a glycine-betaine transporter

A codon-optimized proPXc gene (Fig. S1) was inserted in vector pBAD24 (35) under control of the L-arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter, and the resulting plasmid (pDM4) was introduced to E. coli WG350 as described in Materials and Methods. Glycine-betaine uptake activity was readily detected when plasmid pDM4 was introduced to E. coli WG350, which is otherwise devoid of proline or glycine-betaine uptake activity (58) (Fig. 2 A). The initial rate of glycine-betaine uptake increased linearly with L-arabinose at concentrations up to ∼0.4 mM (Fig. 2 A).

Figure 2.

ProPXc is a glycine-betaine transporter. E. coli strain WG350 pDM4 was cultivated in NaCl-free MOPS medium supplemented with L-arabinose at the indicated concentrations, and the initial rate of glycine-betaine uptake was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent standard errors of the means for three replicate measurements. (A) Initial rates of glycine-betaine uptake were measured in unsupplemented MOPS medium with an osmolality of 0.15 mol/kg and at a glycine-betaine concentration of 100 μM. (B) MOPS medium was supplemented with L-arabinose (45 μM) and with NaCl to attain an osmolality of 0.24 mol/kg (open circles) or 0.45 mol/kg (closed circles). The regression lines were obtained by fitting the data to the Michaelis Menten equation by non-linear regression using Sigma-Plot 12.5. The resulting parameters are listed in Table 1.

The kinetics and substrate specificity of ProPXc and other ProP orthologs

Osmolyte uptake activity can be quantified by measuring the uptake of radiolabeled osmolytes or inferred from the stimulation of bacterial growth at high, but not low, osmolality by osmolytes that are not metabolized (osmoprotection). Inhibition of the uptake of radiolabeled osmolytes by structural analogs can imply but does not demonstrate their uptake.

To define the substrate specificity of ProPXc, the abilities of known ProPEc substrates (5, 59) to inhibit the uptake of radiolabeled osmolytes into E. coli via ProPXc or ProPEc were compared (Fig. 3, A and B). Glycine betaine (100 μM) and proline (200 μM) were employed as radiolabeled osmolytes for ProPXc and ProPEc, respectively. Osmoprotection and radiolabeled osmolyte uptake assays had shown proline, glycine betaine, and ectoine to be ProPEc substrates (5, 59, 60), whereas uptake of choline and trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) had been inferred from osmoprotection assays (5, 59).

Figure 3.

Substrate specificities of the ProP orthologs. E. coli strains containing ProPXc (WG350 pDM4, A), ProPEc (WG350 pDC79, B), ProPCg (WG350 pYT12, C), and ProPAt (WG350 pYT13, D) were grown in NaCl-free MOPS medium. Expression of ProPAt was induced with 0.3 mM arabinose (36), and expression of ProPXc was induced with 0.4 mM arabinose. To optimize the activity of each transporter, the assay media were adjusted with NaCl to attain osmolalities of 0.15 mol/kg (A), 0.44 mol/kg (B and D), and 0.59 mol/kg (C). Assay media contained radiolabeled proline or glycine betaine at concentrations of 200 and 100 μM, respectively. Representative initial rates attained in assays without inhibitors were (nmoles/min/mg protein): 38 ± 3 (ProPXc, A); 63 ± 1 (ProPEc, B); 47 ± 3 (ProPCg, C); and 59 ± 1 (ProPAt, D). Error bars represent standard errors of the means for three replicate measurements.

Glycine betaine and ectoine strongly inhibited proline uptake via ProPEc, choline inhibited weakly, and TMAO did not inhibit in this range (Fig. 3 B). ProPEc has similar high affinities for proline and glycine betaine (59), but proline acted as only a moderate inhibitor of glycine-betaine uptake via ProPXc (Fig. 3 A). Ectoine was a strong inhibitor, whereas choline and TMAO inhibited glycine-betaine uptake weakly.

This work prompted us to assess the substrate specificities of the previously characterized ProP orthologs from A. tumefaciens (ProPAt, group A) and C. glutamicum (ProPCg, group B) (36). Competition assays implied that the substrate specificity of ProPAt (group A, Fig. 3 D) is very similar to that of ProPEc (Fig. 3 B), as is that of ProPDd, the group A ortholog from Dickeya didantii (formerly Erwinia chrysanthemi) (61). In contrast to the group A transporters and ProPXc, ectoine, but not glycine betaine, inhibited proline uptake via ProPCg (Fig. 3 C). Ectoine was the common substrate or strong inhibitor among all tested transporters. Clearly, significant variation has been introduced to the substrate binding sites of ProP transporters in the course of evolution.

For ProPEc, both KM and Vmax for proline uptake increase dramatically with the assay medium osmolality (Table 1) (14). Most remarkably, KM for proline uptake via ProPEc increased 20-fold as the osmolality varied from 0.21 to 0.47 mol/kg (14). ProPXc behaved very differently. The KM of ProPXc for glycine betaine (∼9.7 μM (Fig. 2 B)) was comparable to that of ProPEc for proline or glycine betaine at low osmolality (14, 59). However, the KM for glycine-betaine uptake increased only 1.4-fold as the assay medium osmolality varied from 0.25 to 0.45 mol/kg (Fig. 2 B; Table 1). This distinction has important implications for the mechanism of osmosensing (see Discussion).

Table 1.

The Kinetic Parameters for Osmolyte Uptake via ProPXc and ProPEc

| Glycine-Betaine Uptake via ProPXc | Proline Uptake via ProPEc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osmolality | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.47 |

| KM | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 13.9 ± 0.9 | 6 ± 2 | 85 ± 6 | 125 ± 8 |

| Vmax | 12.1 ± 0.3 | 8.6 ± 0.2 | 14.0 ± 0.5 | 76 ± 2 | 79 ± 2 |

The kinetic parameters for glycine-betaine uptake via ProPXc and proline uptake via ProPEc, determined as described in Materials and Methods, are KM (μM) and Vmax (nmoles/min/mg protein). These parameters were measured as a function of the assay medium osmolality (mol/kg). The data for ProPXc are further illustrated in Fig. 2, and those for ProPEc were reported previously by Culham et al. (14).

The osmolality dependence of ProPXc activity in vivo

The activities of ProPXc and ProPEc in E. coli were measured at an array of assay medium osmolalities (Fig. 4). In preliminary experiments, ProPXc activity had been adjusted by arabinose induction to match that of ProPEc (without arabinose induction) at high osmolality (0.45 mol/kg) (Fig. 2 A). The activities of ProPXc and ProPEc were similar functions of the assay medium osmolality (Fig. 4). However, unlike ProPEc activity, ProPXc activity did not approach zero at the lowest osmolality tested.

Figure 4.

Osmolality dependence of osmolyte uptake via ProPXc and ProPEc in E. coli. E. coli strains WG350 pDC79 (open circles, ProPEc) and WG350 pDM4 (closed circles, ProPXc) were cultivated in NaCl-free MOPS medium that was unsupplemented (ProPEc) or supplemented with 0.4 mM arabinose (ProPXc). Initial rates of osmolyte uptake were measured as described in Materials and Methods using assay media adjusted to the indicated osmolalities with NaCl. Radiolabeled proline (for ProPEc) and glycine betaine (for ProPXc) were provided at concentrations of 200 and 100 μM, respectively. The arrow indicates the growth medium osmolality. Error bars represent standard errors of the means for three replicate measurements.

Comparison of the absolute activities of ProPXc and ProPEc in vivo required estimation of their expression levels. Anti-ProPEc antibodies are available, but anti-ProPXc antibodies are not. N-terminal His10-tags were therefore added to ProPEc and ProPXc so that their levels could be compared by Western blotting with anti-PentaHis antibodies (see Materials and Methods; Table S3). The activity of wild-type ProPEc, encoded by pBAD24-based plasmid pDC79 and without L-arabinose induction (21), is comparable to the activity of chromosomally encoded ProPEc, with osmotic induction of proP expression (62). ProPEc encoded by pDC79 was therefore used as a standard for ProP expression at a physiologically relevant level. The levels of the His-tagged transporters were adjusted by supplementing the bacterial growth media with D-glucose or L-arabinose, which repress and induce transcription from the araBAD promoter, respectively. Western blots employing anti-ProPEc antibodies revealed that D-glucose (2.2 mM) adjusted the expression level of His10-ProPEc to match that of ProPEc when both were encoded by pBAD24 (Fig. 5, A and C). Western blots employing anti-PentaHis antibodies revealed similar expression levels for His10-ProPEc (repressed with 2.2 mM D-glucose) and His10-ProPXc (induced with 4 μM L-arabinose) (Fig. 5, B and C).

Figure 5.

The absolute activities of His10-ProPXc, His10-ProPEc, and truncated His10-ProPEc variants in E. coli. E. coli WG350 derivatives harboring plasmids that encoded the indicated ProP variants were cultivated as for transport assays (see Materials and Methods). The media for the strains containing His10-ProPEc and His10-ProPXc were supplemented with D-glucose (2.2 mM) and L-arabinose (4 μM), respectively. (A–C) The transporter contents of cell extracts were compared by Western blotting with anti-ProPEc antibodies (21) (A) and anti-PentaHis antibodies (Qiagen, B). The loading of cell protein was determined by GelCode Blue (ThermoFisher Scientific) staining of a replicate sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel (C). ProPEc and His10-ProPEc were expressed at similar levels after no induction and D-glucose repression of the encoding genes, respectively (A). Further, densitometric analysis indicated that the expression levels of the other variants relative to His10-ProPEc (and hence ProPEc) were 0.42 for His10-ProPXc, 3.1 for His10-ProPEcΔ11, and 1.9 for His10-ProPEcΔ18 (B). (D) Initial rates of osmolyte uptake were measured as described in Materials and Methods using assay media adjusted to the indicated osmolalities with NaCl. Radiolabeled proline (for ProPEc and its variants) and glycine betaine (for ProPXc) were provided at concentrations of 200 and 100 μM, respectively. The activities of the His10-tagged transporters were corrected for their expression levels relative to ProPEc by applying the factors listed above. The symbols are ProPEc (closed circles), His10-ProPXc (open circles), His10-ProPEcΔ11 (closed inverted triangles), and His10-ProPEcΔ18 (closed triangles). Error bars represent standard errors of the means for three replicate measurements.

Next, the osmolality dependencies of the initial rates of osmolyte uptake via His10-ProPXc and ProPEc were compared at the same expression level (Fig. 5 D). ProPEc attained a maximal activity ∼2.5-fold higher than that of His10-ProPXc. The KM for glycine-betaine uptake via ProPXc is ∼10 μM at high osmolality (Table 1), and for these measurements, glycine betaine was provided at the saturating concentration of 100 μM. Thus, the data in Fig. 5 D approximate Vmax as a function of the osmolality for this transporter. The KM for proline uptake via ProPEc is ∼100 μM at high osmolality (Table 1), and for these measurements, proline was provided at the subsaturating concentration of 200 μM. Thus, the highest rates shown in Fig. 5 D represent ∼2/3 of Vmax for ProPEc. Correcting for this effect, ProPEc would attain a maximal activity ∼4-fold higher than that of His10-ProPXc at the same expression level and degree of substrate saturation. Given the approximate nature of these comparisons, we conclude that ProPEc and ProPXc have similar activities at high osmolality.

In a previous study, ProPEc variants with C-terminal truncations showed low, osmolality-sensitive activity (36). These variants lacked 11 or 18 C-terminal amino acid residues and removed ∼1.5 and 2.5 of the five heptads that comprise the intermolecular, antiparallel coiled coil linking ProPEc monomers, respectively. Hence, these ProPEc variants would be incapable of forming that structure. The ProPEc variant lacking 11 C-terminal residues matches ProPXc in CTD length (Fig. 1). N-terminally His-tagged versions of these variants were created so that they could be included in this comparison. Expression at higher levels than the full-length proteins (Fig. 5, B and C) was required to detect their activities. His10-ProPEcΔ11 and His10-ProPΔ18 attained maximal activities that were 41- and 18-fold lower than that of full-length ProPEc, respectively (Fig. 5 D). In addition, a much higher osmolality was required to attain activity for the truncated variants than for either full-length transporter (Fig. 5 D). Thus, simple truncation of the CTD did not render ProPEc analogous in function to ProPXc.

ProPXc is an osmosensing transporter

ProPEc was designated an osmosensing transporter because the initial rate of proline uptake via ProPEc-His6 is a sigmoid function of the assay medium osmolality in cells and, after purification and reconstitution with E. coli lipid, in PRLs (8, 14, 63). Thus, osmosensing requires only the transporter protein in its lipid environment. ProPXc met the same criteria. As noted above, ProPXc remained active at a lower osmolality than ProPEc in E. coli cells (Figs. 4 and 5). The sigmoid relationship between osmolyte uptake rate and osmolality was fully defined for both transporters upon purification and reconstitution in PRLs (Fig. 6 A). This work showed that coiled-coil formation by the CTD is not essential for osmosensing by ProP.

Figure 6.

ProPXc is an osmosensing transporter. His10-ProPXc and ProPEc-His6 were purified and reconstituted in PRLs and initial rates of proline (ProPEc) or glycine-betaine (ProPXc) uptake were measured as a function of the assay medium osmolality as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Initial rates of osmolyte uptake are plotted as a function of the luminal K+ concentration, the latter calculated on the basis of the assay medium osmolality, the osmolality of the PRL preparation, and the assumption that PRLs behave as ideal osmometers (see inset) (16). The regression lines were obtained by fitting the data to Eq. 3 (16) and the regression parameters are summarized in (B) as means ± the asymptotic standard errors of the means.

PRLs behave as ideal osmometers, and transmembrane water flux in response to osmotic shifts is essentially instantaneous on the timescale of transport assays (18). K+ is the sole luminal cation in the PRLs employed for these studies, and the K+ concentration at each osmolality can be calculated (inset, Fig. 6 A). The dependence of ProPEc activity on the luminal K+ concentration has been interpreted in terms of a thermodynamic, two-state model for transporter activation (see Introduction; Eq. 1, 2, and 3). The initial rates of osmolyte uptake into PRLs reconstituted with His10-ProPXc or ProPEc-His6, measured as a function of assay medium osmolality and hence the (calculated) luminal K+ concentration, were therefore fitted to Eq. 3, yielding the osmotic activation parameters Amax, −lnK0, and SKobs (Fig. 6 B). The fact that ProPXc became active at a lower osmolality than ProPEc in cells (Figs. 4 and 5) and PRLs (Fig. 6) was reflected in the lower absolute values for both −lnK0 and SKobs. The significance of these parameters is discussed further below.

Membrane interaction of the ProPXc CTD

A co-sedimentation assay revealed that a peptide replica of the ProPEc CTD (residues 439–500) bound liposomes comprising polar lipids from E. coli (25). That protein segment was selected because chemical modification of cysteine residues introduced to transmembrane helix XII of ProPEc had revealed that cysteine at position 439 was fully solvent exposed whereas cysteine at position 438 was not (64).

The peptide-liposome co-sedimentation assay was also used to assess the propensity of the ProPXc CTD for membrane association. CTD residues 446–496 were selected on the basis of sequence similarity to ProPEc (Fig. 1). The His-tagged ProPXc peptide was not recovered from cell lysates. That peptide was therefore fused to the C-terminus of protein MalE, which is soluble and secreted to the periplasm via a cleavable, N-terminal signal sequence (Fig. S2, protein MalE∗ProPXcCTD). A corresponding MalE derivative, lacking the ProPXc sequence, was also prepared as a control (Fig. S2, protein MalE∗). Each protein was purified from a periplasmic extract by amylose affinity chromatography and analyzed with mass spectrometry (see Materials and Methods). Purification of MalE∗ProPXcCTD yielded a mixture of the full-length protein and a derivative truncated after A449 of ProPXc, retaining only four ProPXc residues (Fig. S2; Table S4). The expected mass of purified MalE∗ was confirmed (Table S4).

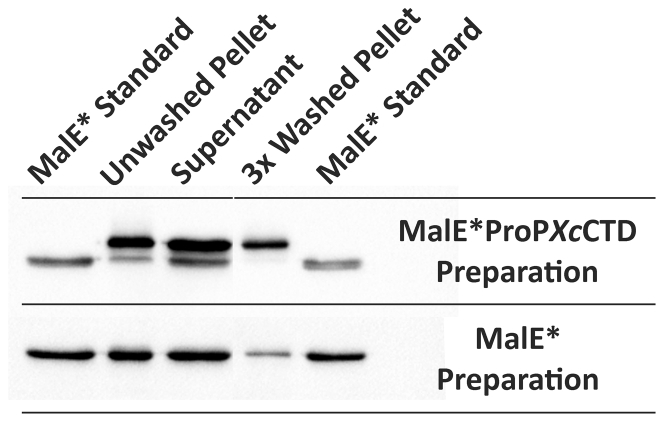

The interactions of MalE∗ProPXcCTD and MalE∗ with liposomes were assessed using the co-sedimentation assay (see Materials and Methods). The proteins co-sedimenting with liposomes and remaining in the supernatant were visualized by Western blotting with anti-MalE antibodies (Fig. 7). Only full-length MalE∗ProPXcCTD was retained after extensive (three times) washing of liposomes that had been mixed with the preparation containing both that protein and its truncated derivative (compare supernatant and pellet fractions). In contrast, a small amount of MalE∗ co-sedimented with liposomes, and its quantity was diminished by washing. Thus, the fused ProPXc CTD mediated association of MalE∗ with liposomes, as previously predicted (25).

Figure 7.

The ProPXc CTD mediates the association of MalE∗ with liposomes. Proteins MalE∗ProPXcCTD and MalE∗ were purified, and their association with liposomes was assessed with a sedimentation assay and Western blotting, employing anti-MalE as primary antibody, as described in Materials and Methods. The MalE∗ProPXcCTD preparation included the full-length protein and a fragment that terminates at A449, whereas the MalE∗ preparation included only the full-length protein (see the text, Fig. S2; Table S4). The gel lanes were loaded with purified MalE∗ protein (as a marker), the pellet and supernatant obtained upon centrifugation of the initial peptide-liposome mixture, and the pellet obtained after washing the initial pellet three times.

Membrane Interaction of the ProPEc CTD

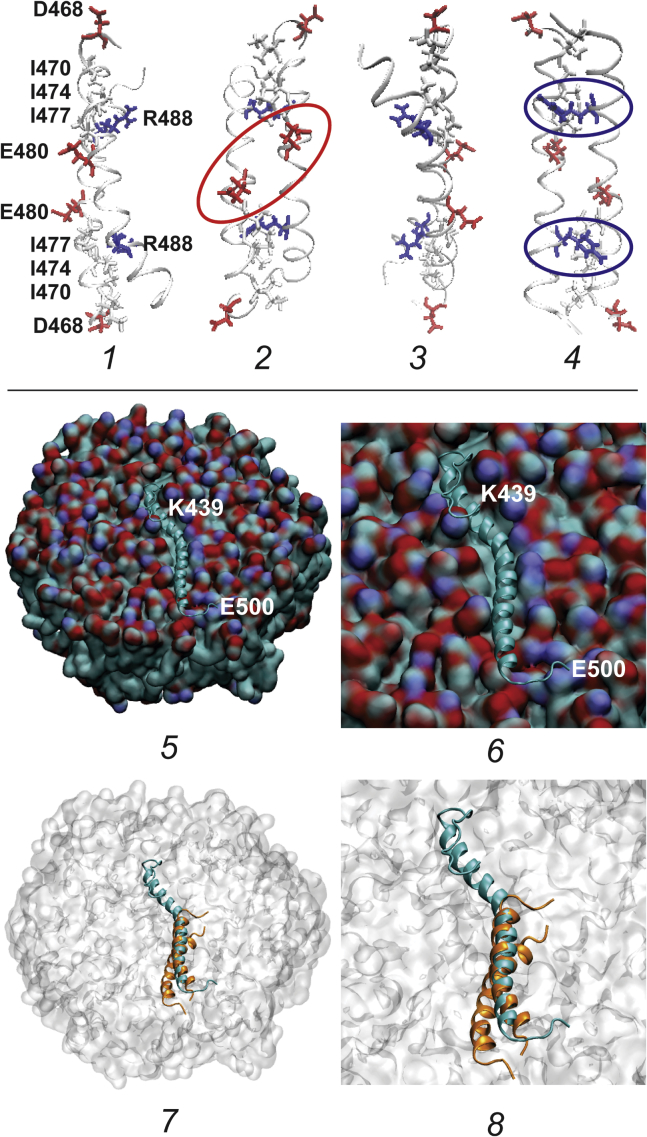

Homology modeling and molecular dynamics simulation were used to further explore the ProPEc CTD-membrane interaction, as described in detail in Materials and Methods. In previous work, a peptide corresponding to ProPEc residues 468–497 was synthesized, and the NMR structure of the antiparallel, homodimeric α-helical coiled coil formed by that peptide was reported (PDB: 1R48) (44) (Fig. 8, images 1–4). One α-helical strand of the coiled-coil structure was used as a template for the corresponding residues of the monomeric, full-length CTD and for upstream residues 454–467, which were also predicted to be α-helical. No template was used for residues 439–453 or 498–500. The extended α-helix persisted during simulation for 100 ns. Representative peptide structures were extracted from solution and aligned with the surface of a membrane comprising PE (80 mol%) and PG (20 mol%). The structure that gave the most negative solvent-membrane transfer free energy was selected for molecular dynamics simulation. The long α-helical segment of the peptide persisted and was embedded in the membrane surface, parallel to the membrane plane, during 100 ns of simulation (Fig. 8, images 5 and 6). The peptide surface formed by the residues at “a” and “d” positions of the coiled-coil heptads extending from isoleucine 456 through histidine 495 faced the membrane. The structures of the termini were more variable. The N-terminal residues of the peptide formed a hairpin stabilized by salt bridges linking arginine 444 with glutamate 465 and lysine 447 with glutamate 461 (Fig. 8, images 5 and 6). However, this structure would be unlikely to form in full-length ProPEc, in which lysine 439 would be tethered at the membrane surface. This work suggests that peptide monomer-membrane association would be mutually exclusive with homodimeric coiled-coil formation for the ProPEc CTD (Fig. 8, images 7 and 8). There is precedent for this phenomenon: a model peptide, employed for studies of membrane fusion, was capable of either α-helical coiled-coil dimer formation or membrane association as a monomer (65).

Figure 8.

Structure and membrane interaction of the ProPEc CTD. Representations of the structure of the ProPEc CTD as a homodimeric antiparallel coiled coil (1–4) and as a membrane-associated monomer (5 and 6) are shown. (1–4) Four representations of the NMR structure (PDB: 1R48) of the antiparallel, homodimeric α-helical coiled coil formed by peptides representing residues 468–497 of ProPEc (44) are shown. Each structure is rotated 90° around the vertical axis relative to the structure to the left. The backbones of the two peptides in each structure are colored gray, with the bonds of each N-terminal aspartate (residue 468) colored red. The bonds of isoleucine residues 470, 474, and 477 are colored gray; those of glutamate 480 are colored red; and those of arginine 488 are colored blue. In structure 2 (showing the “c/g” surface of the coiled coil), the glutamates 480 are circled in red. In structure 4 (showing the “b/e” surface of the coiled coil), the arginines 488 are circled in blue. (The c, g, b, and e refer to positions in the coiled-coil heptad repeat.) 5–8: The interaction of the entire, monomeric CTD of ProPEc (residues 439–500) with the surface of a membrane comprising PE (80%) and PG (20%) is shown. This structure was simulated as described in Materials and Methods. (5 and 6) The α-helical portion of the peptide (turquoise, residues 456–495) is embedded in the membrane, displacing the phospholipid headgroups. The figures represent a snapshot taken after 100 ns of simulation. (7 and 8) The NMR structure of the coiled-coil dimer (orange, residues 468–497) is superimposed on the simulated structure of the membrane-associated peptide monomer (turquoise) to show that coiled-coil formation and membrane association are mutually exclusive (see text).

Impacts of the osmolality on membrane physical properties

The osmolality at which ProPEc activates in cells or PRLs varies directly with the proportion of anionic phospholipids (17, 36). Thus, luminal cations may modulate ProP structure and function by altering phospholipid headgroup-composition-dependent membrane properties. Increasing cation condensation at an anionic membrane surface would be expected to favor increased anionic membrane surface-charge density, decreased membrane fluidity, and increased lateral pressure. Liposomes comprising an E. coli polar lipid extract were used to simulate the membrane environment of ProPEc in PRLs and hence to determine whether the osmotic activation of ProP would correlate with changes in membrane fluidity or lateral pressure.

The lipid-soluble fluorescent dye DPH intercalates into the membrane core, where its mobility reflects that of the phospholipid acyl chains. The anisotropy of DPH fluorescence is an indicator of its mobility and hence of membrane fluidity (56). As expected, the fluorescence anisotropy of DPH in E. coli lipid liposomes decreased as a function of temperature (Fig. 9 A), indicating an increase in membrane fluidity. Next, DPH-labeled liposomes were diluted into NaCl- or sorbitol-supplemented buffer to increase the luminal K+ concentration, mimicking the procedure for osmotic activation of proline uptake via ProP in PRLs. The DPH fluorescence anisotropy (R) increased as the osmolality, and hence the luminal K+ concentration, increased (Fig. 9 B). The increase in R over the tested osmolality range indicated a decrease in membrane fluidity comparable to that occurring upon a temperature change of ∼5°C (compare (A) and (B) of Fig. 9). Thus, there was a clear correlation between the luminal potassium phosphate concentration and this physical property of the membrane.

Figure 9.

Impact of the osmolality on membrane fluidity. The membrane fluidity was estimated by determining the fluorescence anisotropy (R) of DPH in liposomes prepared with a polar lipid extract from E. coli, as described in the text and Materials and Methods. Fluorescence anisotropies are reported as means ± the standard error of the mean for four replicate measurements. (A) DPH fluorescence anisotropy was measured as a function of temperature in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer with no added NaCl. (B) DPH fluorescence anisotropy was measured at 25°C as a function of the osmolality attained by adding NaCl (closed circles) or sorbitol (open circles) to the phosphate buffer. The sorbitol concentration was limited to avoid introducing viscosity effects. The luminal K+ concentration of the liposomes (see inset) was calculated on the basis that the phosphate buffer contained 0.178 M K+ and the liposomes behaved as ideal osmometers (42).

Lateral pressure exists parallel to a membrane surface when phospholipids with a negative intrinsic curvature (e.g., PE and cardiolipin) form a flat bilayer, compressing the acyl chains (66, 67). The impacts of salts on the lateral pressure were investigated by incorporating 10-DipyPC into liposomes and monitoring intramolecular pyrene excimer formation, as described by Templer et al. (57). The ratio of excimer/monomer fluorescence emission intensity (η) increased as a function of temperature, as previously reported (57) (Fig. S3 A). This indicated an increase in lateral pressure with temperature. In contrast, a very small decrease in η was observed when the liposomes were diluted into NaCl-supplemented buffer to increase the luminal K+ concentration (Fig. S3 B). The decrease in η that occurred as the osmolality (and hence the luminal K+ concentration) increased in the range known to activate ProP corresponded to that occurring with a temperature change of only 1°C. This decrease may have occurred because rotation of the pyrenyl moieties on 10-DipyPC was hindered at low membrane fluidity, not because the lateral pressure decreased (68).

Discussion

We propose that group A ProP orthologs may exist in three forms that differ in transport activity (Fig. 10):

| (6) |

where I designates the inactive ProP species in which the CTD associates with the membrane surface and A designates the active ProP species in which the CTD is free in the cytoplasm. Membrane association of the CTD would lock the protein in an inactive, inward-facing conformation to prevent proton-osmolyte symport. AC designates active ProP species in which the CTDs form antiparallel, homodimeric coiled coils. Coiled-coil formation would prevent the CTD from returning to the membrane surface because the arrangements of the CTDs in ProPI and ProPAC are mutually exclusive. A flexible linker (residues 439–467) connects the cytoplasmic end of each transmembrane (TM) helix XII to the coiled coil. Thus, coiled-coil formation would stabilize ProPEc in a second, active form. The distribution of ProPEc among these forms would be modulated by the osmolality so that ProPI would be favored at low osmolality, whereas ProPA and ProPAC would be favored at increasingly high osmolality.

Figure 10.

Proposed structural mechanism of osmosensing. ProPEc is believed to mediate proton-osmolyte symport via an alternating access mechanism in which its N- and C-terminal helix bundles can reorient, exposing the proton (H+) and osmolyte (gray circles) binding sites sequentially to the periplasm and cytoplasm. As an osmosensor, ProPEc may exist in three forms. In ProPI, the CTD associates with the membrane surface to lock the protein in an inactive, inward-facing conformation. In ProPA, the CTD is free and ProP is active, alternating between outward and inward-facing conformations. In ProPAC, the active species is stabilized as the CTDs form antiparallel, homodimeric coiled coils. Coiled-coil formation prevents the CTD from returning to the membrane surface because the arrangements of the CTDs in ProPI and ProPAC are mutually exclusive (Fig. 8). The distribution of ProPEc among these forms would be modulated by the osmolality: ProPI would be favored at low osmolality, whereas ProPA and ProPAC would be favored at increasingly high osmolality as the membrane fluidity decreases (see Fig. 9). ProP orthologs lacking the C-terminal coiled coil (e.g., ProPXc) would exist only as form ProPI or ProPA.

On this basis, group B orthologs, which lack the coiled coil, would exist only as ProPI or ProPA (Fig. 10). Dissociation of the CTD from the membrane surface (the first step of Eq. 6) would be sufficient to activate such transporters. However, they would lack stabilization of the active form afforded by coiled-coil formation (the second step of Eq. 6). This interpretation is supported by evidence that ProPXc is an osmosensing transporter (Fig. 6) and that the ProPXc CTD associates with liposomes (Fig. 7). The KM for osmolyte uptake via ProPEc is a direct function of the medium osmolality, but that of ProPXc is not (Table 1). The KM change for ProPEc may be associated with coiled-coil formation and stabilization of the active transporter form, processes not accessible to ProPXc.

Many observations support the proposed model for the osmotic activation of ProPEc. The proposal that ProPI assumes a cytoplasm-facing conformation is supported by analyses of the N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) reactivities of cysteine residues introduced to ProPEc (69, 70). NEM alkylates solvent-exposed cysteine thiol groups. The N-terminal six-helix bundle of ProPEc includes a membrane-embedded cluster of ionizable residues that are highly conserved among MFS members and implicated in solute translocation (70). Decreasing osmolality markedly decreased the NEM reactivities of cysteines replacing residues located in the periplasm-proximal half of transmembrane helix I and the first and fifth periplasmic loops of ProPEc (69, 70). Decreasing osmolality did not alter the reactivities of cysteines replacing other periplasmic residues or cytoplasm-proximal residues in transmembrane helix I (70). These results suggested that a pathway extending from the periplasm toward the membrane-embedded cluster of ionizable residues was less solvent-exposed at low than at high osmolality. This would be consistent with the close packing of TMs close to the periplasmic membrane surface that is observed in structures representing MFS members in cytoplasm-facing conformations (71, 72, 73).

The impacts of many structural changes to the 62 amino acid CTD (residues 439–500) on the osmotic activation of ProPEc have been documented (17, 21, 24, 25, 74). These effects can be interpreted in the context of the NMR structure showing that residues 468–497 form an antiparallel, homodimeric α-helical coiled coil (Fig. 8 1). Although only residues 468–497 participate in antiparallel coiled-coil formation, coiled-coil heptad repeats extend from isoleucine 456 through arginine 497 (Fig. 1). That entire portion of the CTD is predicted to be α-helical (Fig. 1) and to associate with the membrane as a monomer in which the surface formed by coiled-coil heptad “a” and “d” residues serves as the protein-membrane interface (residues 456–497, Fig. 8, 4–8). Thus, the same protein surfaces are predicted to be implicated in coiled-coil formation and membrane interaction. The impacts of four structural modifications are particularly informative in the context of these observations.

First, deletion of 11 or 18 residues from the C-terminus of ProPEc rendered it refractory to osmotic activation (36) (Figs. 1 and 5). Those deletions precluded homodimeric coiled-coil formation and hence the proposed transition from ProPA to ProPAC. Our model predicts that the residual, monomeric CTDs would associate with the membrane surface, favoring ProPI (Fig. 8, 5 and 6).

Second, replacement of isoleucines 470, 474, and 477 with alanines created ProPEc variants that were unable to form a homodimeric coiled coil (25). The alanines replaced bulky isoleucine residues that would promote coiled-coil formation by occupying three consecutive positions in the coiled-coil core (Fig. 8 2). These changes increased the affinity of the CTD peptide for liposomes comprising E. coli phospholipid and eliminated transport activity (25). Thus, as proposed, stabilization of the membrane-bound form of the CTD relative to the coiled-coil form inactivated the transporter.

Third, glutamates 480 (E480) of ProPEc are located in proximal heptad “g” positions on the surface of the coiled-coil dimer (Fig. 8 2). Replacement E480C did not disrupt coiled-coil formation (75). However, it decreased the affinity of the CTD for liposomes (25) and allowed transporter dimers to be cross-linked with thiol-reactive, cross-linker dithio-bis-maleimidoethane (74). As predicted, this fixation of ProPEc in the coiled-coil dimer form (ProPAC) was associated with increased transporter activity at low osmolality (17).

Finally, two sets of salt bridges linking arginine 488 (R488) with aspartates 475 and 478 (D475 and D478) on the opposing strand stabilize the antiparallel coiled coil formed by the ProPEc CTD (Fig. 8 4) (24, 44). Replacement of R488 with isoleucine destabilized the antiparallel coiled coil, promoted parallel coiled-coil formation by the ProPEc CTD (24, 74), and impaired interaction of the CTD with the membrane (25). Remarkably, this replacement both elevated the osmolality at which ProPEc became active and rendered that activation transient (21, 24). Apparently, osmotically induced formation of a parallel coiled coil produced an unphysiological, inactive form of ProP not included in our model.

Thermodynamic analysis based on a two-state model (Eq. 2) suggested that anionic functional groups cluster as ProPEc transitions from an inactive to an active form with increasing cation concentration (16). If the proposed structural mechanism for the osmotic activation of ProPEc were correct, such thermodynamic analyses would encompass steps 1 and 2 of Eq. 6, having equilibrium constant . The reported data for ProPEc were equally consistent with a two-state monomer model and an inactive monomer/active dimer model (16). For other systems, parameter SKobs of Eq. 2 is proportional to the numbers of charges clustering or dispersing during a biomolecular process. The current work yielded an SKobs for ProPEc of 7 (Fig. 6). Corresponding analyses of cation effects on a DNA oligonucleotide helix to coil transitions suggested that, for that system, an SKobs of −7 would reflect the dispersion of ∼14–18 negative charges. Thus, the observed SKobs for ProPEc is consistent with an overall process that includes the association of two ProPEc CTDs, each with a net charge of −7 (Fig. 1; step 2 of Eq. 6). The much smaller SKobs for ProPXc (Fig. 6; (3)) is consistent with the fact that its CTD does not have a large, net negative charge or associate to form a coiled coil, though of course other differences may also contribute to this result.

Can this thermodynamic analysis also accommodate the transition from ProPI to ProPA (step 1 of Eq. 6), which is shared by both ProPEc and ProPXc? The membrane-proximal portion of the ProPEc CTD and the entire ProPXc CTD are nonpolar in comparison with the coiled-coil forming portion of the ProPEc CTD (Fig. 1). However, the membrane surface is anionic. The membrane fluidity decreases as the osmolality and luminal K+ concentration increase over the range in which ProP activates (Fig. 9). This may reflect increasing neutralization of the membrane surface charge by osmotically induced counter-cation (K+) condensation. The resulting increase in surface charge density and decrease in membrane fluidity may favor release of the CTD from the membrane surface (Fig. 10). Other studies have shown helical peptide-membrane interaction and membrane physical properties to be interdependent. For example, membrane fluidity influenced both helix induction and membrane association for the intrinsically disordered protein α-synuclein (76, 77), and membrane association of α-helical antimicrobial peptides increased membrane fluidity (78, 79).

Osmosensing transporters ProP, BetP, and OpuA are not structurally related, but the proposed mechanism for osmosensing and the osmotic activation of ProP resembles earlier models for the osmotic activation of transporters BetP (80) and OpuA (12). Each transporter possesses an extended cytoplasmic CTD that may mediate osmosensing via salt-sensitive interactions with other transporter elements (protein-protein interactions) and/or the membrane surface. In each case, solvent sensing is thought to occur as cellular dehydration alters those interactions. Here, we propose that cellular dehydration causes cations to accumulate at the membrane surface, triggering transporter activation by altering lipid behavior. Thus, we propose that solvent-lipid interaction is the primary step in osmosensing.

Author Contributions

J.M.W. and G.L. designed the research in consultation with the other authors. D.E.C., D.M., R.B., J.G., T.N.O., N.S., and L.T. performed the research. All authors analyzed data. J.M.W. wrote the manuscript with input from the other authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for assistance from Drs. Dyanne Brewer and Armen Charchoglyan (Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Guelph) and for comments from Judith and Jack Kornblatt (Concordia University) on the manuscript. NAMD was developed by the Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group in the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. We thank Compute Canada, Calcul Quebec and Sharcnet for supercomputer access.

This work was supported by grants awarded to J.M.W. and G.L. by The Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (Discovery Grants 508-2008 and RGPIN 355789, respectively).

Editor: D. Peter Tieleman.

Footnotes

Three figures and four tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)31212-8.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Sies M., Haussinger D. Osmosensing and Osmosignaling. Methods Enzymol. 2007;428:1–579. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)28007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anishkin A., Loukin S.H., Kung C. Feeling the hidden mechanical forces in lipid bilayer is an original sense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7898–7905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313364111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood J.M. Bacterial responses to osmotic challenges. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015;145:381–388. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201411296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood J.M. Bacterial osmoregulation: a paradigm for the study of cellular homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;65:215–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murdock L., Burke T., Wood J.M. Analysis of strains lacking known osmolyte accumulation mechanisms reveals contributions of osmolytes and transporters to protection against abiotic stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:5366–5378. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01138-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krämer R. Bacterial stimulus perception and signal transduction: response to osmotic stress. Chem. Rec. 2010;10:217–229. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood J.M. Osmosensing by bacteria: signals and membrane-based sensors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:230–262. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.230-262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racher K.I., Voegele R.T., Hallett F.R. Purification and reconstitution of an osmosensor: transporter ProP of Escherichia coli senses and responds to osmotic shifts. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1676–1684. doi: 10.1021/bi981279n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Heide T., Poolman B. Osmoregulated ABC-transport system of Lactococcus lactis senses water stress via changes in the physical state of the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7102–7106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rübenhagen R., Rönsch H., Morbach S. Osmosensor and osmoregulator properties of the betaine carrier BetP from Corynebacterium glutamicum in proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:735–741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krämer R., Nicklisch S., Ott V. Use of liposomes to study cellular osmosensors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;606:21–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-447-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poolman B., Spitzer J.J., Wood J.M. Bacterial osmosensing: roles of membrane structure and electrostatics in lipid-protein and protein-protein interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:88–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culham D.E., Meinecke M., Wood J.M. Impacts of the osmolality and the lumenal ionic strength on osmosensory transporter ProP in proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:27813–27822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.387936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culham D.E., Henderson J., Wood J.M. Osmosensor ProP of Escherichia coli responds to the concentration, chemistry, and molecular size of osmolytes in the proteoliposome lumen. Biochemistry. 2003;42:410–420. doi: 10.1021/bi0264364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karasawa A., Swier L.J., Poolman B. Physicochemical factors controlling the activity and energy coupling of an ionic strength-gated ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:29862–29871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.499327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culham D.E., Shkel I.A., Wood J.M. Contributions of Coulombic and Hofmeister effects to the osmotic activation of Escherichia coli transporter ProP. Biochemistry. 2016;55:1301–1313. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romantsov T., Stalker L., Wood J.M. Cardiolipin controls the osmotic stress response and the subcellular location of transporter ProP in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:12314–12323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Heide T., Stuart M.C., Poolman B. On the osmotic signal and osmosensing mechanism of an ABC transport system for glycine betaine. EMBO J. 2001;20:7022–7032. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pegram L.M., Wendorff T., Record M.T., Jr. Why Hofmeister effects of many salts favor protein folding but not DNA helix formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7716–7721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913376107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Record M.T., Jr., Guinn E., Capp M. Introductory lecture: interpreting and predicting Hofmeister salt ion and solute effects on biopolymer and model processes using the solute partitioning model. Faraday Discuss. 2013;160:9–44. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20128c. discussion 103–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Culham D.E., Tripet B., Wood J.M. The role of the carboxyl terminal α-helical coiled-coil domain in osmosensing by transporter ProP of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Recognit. 2000;13:309–322. doi: 10.1002/1099-1352(200009/10)13:5<309::AID-JMR505>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peter H., Burkovski A., Krämer R. Osmo-sensing by N- and C-terminal extensions of the glycine betaine uptake system BetP of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2567–2574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biemans-Oldehinkel E., Mahmood N.A., Poolman B. A sensor for intracellular ionic strength. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10624–10629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603871103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsatskis Y., Kwok S.C., Wood J.M. Core residue replacements cause coiled-coil orientation switching in vitro and in vivo: structure−function correlations for osmosensory transporter ProP. Biochem. 2008;47:60–72. doi: 10.1021/bi7018173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romantsov T., Culham D.E., Wood J.M. ProP-ProP and ProP-phospholipid interactions determine the subcellular distribution of osmosensing transporter ProP in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2017;103:469–482. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dianese J.C., Schaad N.W. Isolation and characterization of inner and outer membranes of Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris. Phytopathology. 1982;72:1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landfald B., Strøm A.R. Choline-glycine betaine pathway confers a high level of osmotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1986;165:849–855. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.849-855.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller J.H. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neidhardt F.C., Bloch P.L., Smith D.F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Culham D.E., Lasby B., Wood J.M. Isolation and sequencing of Escherichia coli gene proP reveals unusual structural features of the osmoregulatory proline/betaine transporter, ProP. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;229:268–276. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J., Russell D.W. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Culham D.E., Hillar A., Wood J.M. Creation of a fully functional cysteine-less variant of osmosensor and proton-osmoprotectant symporter ProP from Escherichia coli and its application to assess the transporter’s membrane orientation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11815–11823. doi: 10.1021/bi034939j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kempf B., Bremer E. Uptake and synthesis of compatible solutes as microbial stress responses to high-osmolality environments. Arch. Microbiol. 1998;170:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s002030050649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guzman L.M., Belin D., Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsatskis Y., Khambati J., Wood J.M. The osmotic activation of transporter ProP is tuned by both its C-terminal coiled-coil and osmotically induced changes in phospholipid composition. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41387–41394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.di Guan C., Li P., Inouye H. Vectors that facilitate the expression and purification of foreign peptides in Escherichia coli by fusion to maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1988;67:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maina C.V., Riggs P.D., Guan C.D. An Escherichia coli vector to express and purify foreign proteins by fusion to and separation from maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1988;74:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith P.K., Krohn R.I., Klenk D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redinbaugh M.G., Turley R.B. Adaptation of the bicinchoninic acid protein assay for use with microtiter plates and sucrose gradient fractions. Anal. Biochem. 1986;153:267–271. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasband W.S. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1997–2016. ImageJ. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Racher K.I., Culham D.E., Wood J.M. Requirements for osmosensing and osmotic activation of transporter ProP from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7324–7333. doi: 10.1021/bi002331u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eswar N., Eramian D., Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;426:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zoetewey D.L., Tripet B.P., Hodges R.S. Solution structure of the C-terminal antiparallel coiled-coil domain from Escherichia coli osmosensor ProP. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jo S., Kim T., Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., III, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee J., Cheng X., Im W. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Best R.B., Zhu X., Mackerell A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lomize M.A., Pogozheva I.D., Lomize A.L. OPM database and PPM web server: resources for positioning of proteins in membranes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D370–D376. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jo S., Kim T., Im W. Automated builder and database of protein/membrane complexes for molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One. 2007;2:e880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jo S., Lim J.B., Im W. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for mixed bilayers and its application to yeast membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;97:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu E.L., Cheng X., Im W. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2014;35:1997–2004. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klauda J.B., Venable R.M., Pastor R.W. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J.Mol.Graphics. 1996;14:33–38, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lentz B.R. Membrane “fluidity” as detected by diphenylhexatriene probes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1989;50:171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Templer R.H., Castle S.J., Klug D.R. Sensing isothermal changes in the lateral pressure in model membranes using di-pyrenyl phosphatidylcholine. Faraday Discuss. 1998;111:41–53. doi: 10.1039/a806472e. discussion 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Culham D.E., Emmerson K.S., Wood J.M. Genes encoding osmoregulatory proline/glycine betaine transporters and the proline catabolic system are present and expressed in diverse clinical Escherichia coli isolates. Can. J. Microbiol. 1994;40:397–402. doi: 10.1139/m94-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacMillan S.V., Alexander D.A., Wood J.M. The ion coupling and organic substrate specificities of osmoregulatory transporter ProP in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1420:30–44. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jebbar M., Talibart R., Blanco C. Osmoprotection of Escherichia coli by ectoine: uptake and accumulation characteristics. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:5027–5035. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5027-5035.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]