Abstract

Sepsis is a syndrome with physiologic, pathologic, and biochemical abnormalities induced by infection. Sepsis can induce the dysregulation of systemic coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, resulting in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which is associated with a high mortality rate. Although there is no international consensus on available treatments for sepsis-induced DIC, DIC diagnosis and treatment are commonly performed in Japanese clinical settings. Therefore, clinical data related to sepsis-induced DIC diagnosis and treatment can be obtained from Japanese clinical settings. We performed a retrospective nationwide observational study (Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation [J-SEPTIC DIC] study) to collect data regarding characteristics of sepsis patients in Japan, with a focus on coagulofibrinolytic dysregulation and DIC treatment received by each patient. The J-SEPTIC DIC study collected information for a total of 3,195 patients with severe sepsis and septic shock and is the largest data set in Japan on DIC diagnosis and treatment in clinical settings.

Subject terms: Therapeutics, Haematological diseases, Infection

Background & Summary

Sepsis is a syndrome with physiologic, pathologic, and biochemical abnormalities induced by infection and resulting in life-threatening organ dysfunction1,2. A global epidemiological report estimated that 31.5 million people are affected by sepsis and 19.4 million people are affected by severe sepsis each year, with a potential 5.3 million deaths worldwide from sepsis each year3.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is induced by the dysregulation of systemic coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in sepsis and septic shock2,4,5. Sepsis-induced DIC causes the development of microthrombi, which cause tissue hypoperfusion and result in multiple organ failure; sepsis-induced DIC is thus associated with a high mortality rate2,4,5. However, because appropriate treatments for sepsis-induced DIC have not been widely studied, there is no international consensus on available treatments for sepsis-induced DIC6,7, and in many countries specific treatment for sepsis-induced DIC in clinical settings is not provided8. On the other hand, in Japanese clinical settings, DIC diagnosis using scoring systems are generalized in sepsis management9. Furthermore, recombinant thrombomodulin, antithrombin and other anticoagulants are approved as DIC treatment drugs and are frequently used in patients with sepsis-induced DIC10,11. Therefore, clinical data related to the treatment of sepsis-induced DIC can be collected from clinical settings in Japan.

We performed a retrospective nationwide observational study (Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation [J-SEPTIC DIC] study), which collected data on the characteristics of sepsis patients with a focus on coagulation dysregulation and DIC treatments. Previous studies on DIC treatment have been conducted using the J-SEPTIC DIC data set12–20.

Methods

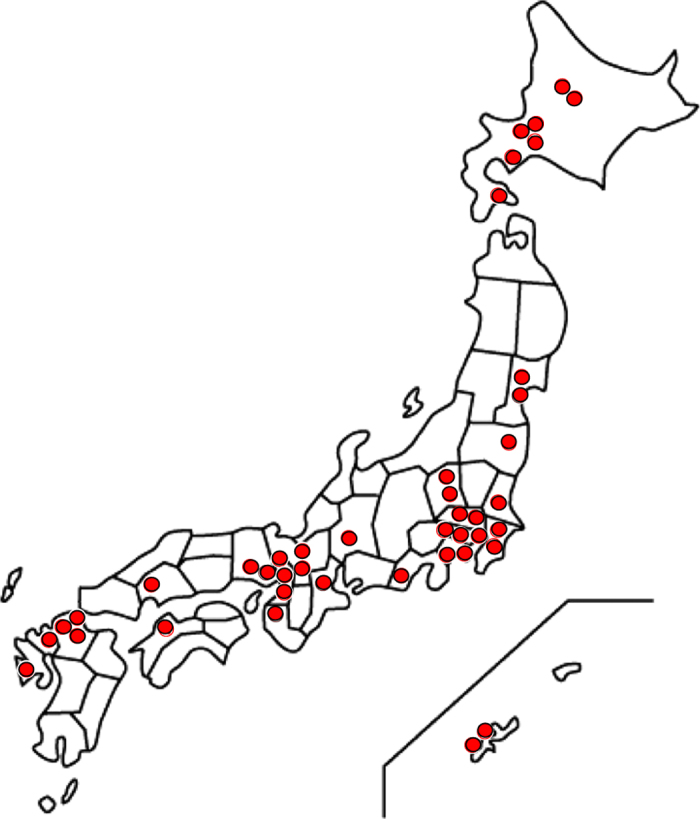

The J-SEPTIC DIC study was conducted in 42 intensive care units (ICUs) of 40 institutions throughout Japan (Table 1 and Fig. 1) and was approved by the institutional review boards of each hospital. The boards waived the requirement for informed consent, due to the retrospective design.

Table 1. List of participating institutions.

| Institutions |

|---|

| Akashi City Hospital |

| Asahikawa Medical University |

| Asahikawa Red Cross Hospital |

| Ehime University Hospital |

| Fukuoka University Hospital |

| Gifu University Hospital |

| Graduate School of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus |

| Gunma University |

| Hakodate Municipal Hospital |

| Hokkaido University Hospital |

| Hyogo College of Medicine |

| Ibaraki Prefectural Central Hospital |

| JA Hiroshima General Hospital |

| Japan Red Cross Maebashi Hospital |

| Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center |

| Jikei University School of Medicine |

| Kameda Medical Center |

| KKR Sapporo Medical Center |

| Kyoto First Red-Cross Hospital |

| Kyushu University Hospital |

| Mie University Hospital |

| Nagasaki University Hospital |

| Nihon University School of Medicine |

| Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital |

| Ohta General Hospital Foundation Ohta Nishinouchi Hospital |

| Osaka General Medical Center |

| Osaka University Hospital |

| Saga University Hospital |

| Saiseikai Yokohamasi Tobu Hospital |

| Saitama Red Cross Hospital |

| Sapporo City General Hospital |

| Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital |

| Sendai City Hospital |

| Shonan Kamakura General Hospital |

| Steel Memorial Muroran Hospital |

| Tohoku University Hospital |

| Tokyo Medical University, Hachioji Medical Center |

| Tomishiro Central Hospital |

| University of Occupational and Environmental Health Hospital |

| Wakayama Medical University Hospital |

Figure 1. Locations of the participating institutions.

Participating institutions for this data set were 42 intensive care units from 40 institutions across Japan.

We retrospectively reviewed data of consecutive patients who were admitted to the ICUs of participating institutions to be treated for severe sepsis or septic shock between January 2011 and December 2013. Severe sepsis and septic shock were defined based on the International Sepsis Definitions Conference criteria21. We excluded patients who were < 16 years old, or patients who developed severe sepsis or septic shock after their ICU admission.

The following data were collected: age; sex; body weight; admission route to the ICU; pre-existing organ dysfunction; pre-existing hemostatic disorder; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score;22 Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score23 (days 1, 3, and 7); systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) score24 (days 1, 3, and 7); primary infection site; blood culture results; microorganisms responsible for the sepsis; daily results from laboratory tests during the first week after ICU admission; lactate levels (days 1, 3, and 7); administration of drugs, including immunoglobulins, and low-dose steroids, during the first week after ICU admission; therapeutic interventions, including surgical interventions at the infection site, renal replacement therapy, renal replacement therapy for non-renal indications, polymyxin B direct hemoperfusion, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and intra-aortic balloon pumping, during the first week after ICU admission; and outcomes in the hospital.

The following data related to DIC diagnosis and treatment were also collected: systemic inflammatory response syndrome score; daily results from laboratory tests, which included platelets counts, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, fibrinogen level, and antithrombin activity; D-dimer levels; fibrin/fibrinogen degradation product levels during the first week after ICU admission; administration of anti-DIC drugs, which included antithrombin, recombinant thrombomodulin, protease inhibitors and heparinoids, and other anticoagulants during the first week after ICU admission; and transfusion amounts and bleeding complications during the first week after ICU admission.

Finally, the following data related to the institutions and ICUs were collected: characteristics of institutions and ICUs (general ICU or emergency ICU); management policy of the ICU (closed or open); number of beds in the ICU; reagents of fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products and D-dimer measurements.

Several analyses have already been conducted and studies have been published using this data set11–16,18–20,25–28.

Data Records

A single data set resulted from the present study. This data set contains information of the 3,195 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in 42 ICUs over 3 years. The information of the institution and the ICU where each patient was admitted is described in the same line as the patient’s information (Data Citation 1). Blanks in the data set indicate missing data. In the present study, all laboratory results were measured according to clinical necessity. Therefore, many missing data were included in the data set. Furthermore, some variables were not available due to death or discharge.

Detailed information on variable specifications is included in a Read_me file (Data Citation 1).

Technical Validation

The present study was a retrospective design. Information of eligible patients was collected in each participating institute and reported to the principal institute (Hokkaido University Hospital) by one investigator per institution. Collected data were assessed by expert emergency and critical care physicians; if outliers in each variable and contradictions within data were detected, data were validated with each investigator in each hospital. The outliers and contradictions were judged by the expert emergency and critical care physicians. Data were finalized and fully anonymized on September 8, 2015.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Hayakawa, M. et al. Nationwide registry of sepsis patients in Japan focused on disseminated intravascular coagulation 2011–2013. Sci. Data. 5:180243 doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.243 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the members of the Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (J-SEPTIC DIC) Study Group: Takeo Azuhata (Division of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Acute Medicine, Nihon University School of Medicine), Fumihito Ito (Department of Emergency & Critical Care Medicine, Ohta General Hospital Foundation Ohta Nishinouchi Hospital), Shodai Yoshihiro (Pharmaceutical Department, JA Hiroshima General Hospital), Hayakawa Katsura (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Saitama Red Cross Hospital), Tsuyoshi Nakashima (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Wakayama Medical University), Takayuki Ogura (Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care Medicine, Advanced Medical Emergency Department and Critical Care Center, Japan Red Cross Maebashi Hospital), Eiichiro Noda (Emergency and Critical Care Center, Kyushu University Hospital), Yoshihiko Nakamura (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Fukuoka University Hospital), Ryosuke Sekine (Emergency Department, Ibaraki Prefectural Central Hospital), Yoshiaki Yoshikawa (Department of Emergency and Critical Care, Osaka General Medical Center), Motohiro Sekino (Division of Intensive Care, Nagasaki University Hospital), Keiko Ueno (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Tokyo Medical University, Hachioji Medical Center), Yuko Okuda (Anesthesiology, Kyoto First Red Cross Hospital), Masayuki Watanabe (Intensive Care Unit, Saiseikai Yokohamasi Tobu Hospital), Akihito Tampo (Department of Emergency Medicine, Asahikawa Medical University), Nobuyuki Saito (Shock and Trauma Center, Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital), Yuya Kitai (Emergency Medicine, Kameda Medical Center), Hiroki Takahashi (Department of Traumatology and Acute Critical Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine), Iwao Kobayashi (Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Asahikawa Red Cross Hospital), Yutaka Kondo (Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus), Wataru Matsunaga (Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care Medicine, Saitama Medical Center Jichi Medical University), Sho Nachi (Advanced Critical Care Center, Gifu University Hospital), Toru Miike (Emergency and Critical Care Center, Saga University Hospital), Hiroshi Takahashi (The Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Steel Memorial Muroran Hospital), Shuhei Takauji (Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care, Sapporo City General Hospital), Kensuke Umakoshi (Division of Emergency Medicine, Ehime University Hospital), Takafumi Todaka (Intensive Care Unit, Tomishiro Central Hospital), Hiroshi Kodaira (Department of Emergency Medicine, Akashi City Hospital), Kohkichi Andoh (Critical Care Department, Sendai City Hospital), Takehiko Kasai (Emergency Department, Hakodate Municipal Hospital), Yoshiaki Iwashita (Emergency and Critical Care Center, Mie University Hospital), Hideaki Arai (Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health Hospital), Masato Murata (Department of Emergency Medicine, Gunma University), Masahiro Yamane (Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, KKR Sapporo Medical Center), Kazuhiro Shiga (Emergency and Critical Care Center, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), Naoto Hori (Intensive Care Unit, Hyogo College of Medicine).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- Hayakawa M., et al. . 2018. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4106036

References

- Singer M. et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315, 801–810 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus D. C. & van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. The New England Journal of Medicine 369, 840–851 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann C. et al. Assessment of Global Incidence and Mortality of Hospital-treated Sepsis. Current Estimates and Limitations. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 193, 259–272 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt B. J. Bleeding and coagulopathies in critical care. The New England Journal of Medicine 370, 847–859 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K., Tamura T. & Sawatsubashi Y. Sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Journal of Intensive Care 4, 23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes A. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Critical Care Medicine 45, 486–552 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H. et al. Guidance for diagnosis and treatment of DIC from harmonization of the recommendations from three guidelines. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis : JTH 11, 716–767 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale R. et al. Promoting Global Research Excellence in Severe Sepsis (PROGRESS): lessons from an international sepsis registry. Infection 37, 222–232 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida O. et al. The Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2016 (J-SSCG 2016). Acute Med Surg 5, 3–89 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata A., Okamoto K., Mayumi T., Muramatsu K. & Matsuda S. Recent Change in Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Japan: An Epidemiological Study Based on a National Administrative Database. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis: Official Journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis 22, 21–27 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M. et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of severe sepsis of 3195 ICU-treated adult patients throughout Japan during 2011-2013. Journal of Intensive Care 4, 44 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M., Yamakawa K., Kudo D. & Ono K. Optimal Antithrombin Activity Threshold for Initiating Antithrombin Supplementation in Patients With Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: A Multicenter Retrospective Observational Study. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis: official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis, 1076029618757346 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yoshihiro S. et al. Recombinant Human Soluble Thrombomodulin Contributes to Reduced Mortality in Sepsis Patients with Severe Respiratory Failure: A Retrospective Observational Study Using a Multicenter Dataset. Shock (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura Y., Yamakawa K., Hayakawa M., Kudo D. & Fujimi S. Concomitant Versus Individual Administration of Antithrombin and Thrombomodulin for Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: A Nationwide Japanese Registry Study. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis: Official Journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis 24, 734–740 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura Y. et al. Screening itself for disseminated intravascular coagulation may reduce mortality in sepsis: A nationwide multicenter registry in Japan. Thrombosis Research 161, 60–66 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo D., Hayakawa M., Ono K. & Yamakawa K. Impact of non-anticoagulant therapy on patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: A multicenter, case-control study. Thrombosis Research 163, 22–29 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura Y., Yamakawa K., Hayakawa M., Hamasaki T. & Fujimi S. Screening itself for disseminated intravascular coagulation may reduce mortality in sepsis: A nationwide multicenter registry in Japan. Thrombosis Research 161, 60–66 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M. et al. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin and mortality in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. A multicentre retrospective study. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 115, 1157–1166 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M. et al. Antithrombin Supplementation and Mortality in Sepsis-Induced Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: A Multicenter Retrospective Observational Study. Shock 46, 623–631 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa K. et al. Benefit profile of anticoagulant therapy in sepsis: a nationwide multicentre registry in Japan. Critical Care 20, 229 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. M. et al. (2001) SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Critical Care Medicine 31, 1250–1256 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus W. A., Draper E. A., Wagner D. P. & Zimmerman J. E. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine 13, 818–829 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent J. L. et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Critical Care Medicine 26, 1793–1800 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone R. C. et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 101, 1644–1655 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M. & Ono K. A summary of the Japan septic disseminated intravascular coagulation study. Acute Med Surg 5, 123–128 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takauji S., Hayakawa M., Ono K. & Makise H. Respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a propensity score analysis in a multicenter retrospective observational study. Acute Med Surg 4, 408–417 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y. et al. Potential survival benefit of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in patients with septic shock: a propensity-matched cohort study. Critical Care 21, 134 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka Y. et al. Low-dose immunoglobulin G is not associated with mortality in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Critical Care 21, 181 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Hayakawa M., et al. . 2018. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4106036