Abstract

Background

Stability, enhanced drug-loading efficiency (DLE), and specific accumulation of therapeutics at tumor sites remain major challenges for successful cancer therapy.

Purpose

This study describes a newly developed intelligent nanosystem that integrates stealthy, active targeting, stimulus-responsiveness, and π–π interaction properties in a single carrier, based on the multifunctional star-shaped biodegradable polyester.

Patients and methods

This highly stable, smart nanocarrier with spherical structures and a low critical micelle concentration (CMC) can provide spacious harbor and strong π–π interaction and hydrophobic interactions for hydrophobic doxorubicin (DOX). Its structure and morphology were characterized by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra, Gel permeation chromatography (GPC), dynamic light scattering (DLS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Antitumor effciency of polymeric micelles using CCK-8 assay, and the intracellular-activated delivery system was tracked by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and flow cytometry.

Results

The synthesized copolymer can be self-assembled into nanoparticles with size of 50 nm and critical micellar concentration of 2.10 µg/mL. The drug-loading content of nanoparticles can be enhanced to 17.35%. Additionally, the stimulus-responsive evaluation and drug release study showed that the nanocarrier can rapidly respond to the intracellular reductive environment and dissociate for drug release. An in vitro study demonstrated that the nanocarrier can ferry doxorubicin selectively into tumor tissue, rapidly enter cancer cells, and controllably release its payload in response to an intracellular reductive environment, resulting in excellent antitumor activity in vitro.

Conclusion

This study provides a facile and versatile approach for the design of multifunctional star-shaped biodegradable polyester nanovehicles for effective cancer treatment.

Keywords: intelligent, star-shaped, biodegradable multifunctional polyester, stimuli- responsiveness, intracellular drug delivery, active targeting, cancer therapy

Introduction

Biodegradable polymers, such as poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly(β-caprolactone) (PCL), and polycarbonate (PC), have received significant attention as anticancer drug delivery systems because of their biocompatible and biodegradable properties.1–3 To date, although there are several biodegradable nanocarriers clinically approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for cancer treatment, including paclitaxel-loaded poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)–poly(l-lactide) micelles and albumin-based nanoparticles (NPs),4 further clinical translation of biodegradable nanoformulation faces some inevitable problems. The major objective in cancer therapy is to achieve good stability in blood circulation, considerable drug-loading efficiency (DLE), and specific drug accumulation at the tumor site.5,6 Most chemotherapeutic agents are liable to leak from nanocarriers in blood circulation and are unable to meet the therapy window, owing to unsatisfactory DLE and uncontrollable drug release. As well, they are unable to differentiate between normal and diseased cells,7 thus resulting in undesired side effects and unsuccessful therapeutic effects. Aiming to prolong blood circulation time and improve the DLE, different types of biodegradable polyesters were utilized to construct nanocarriers, including linear-, graft-, dendritic-, and star-shaped biodegradable polymers.8–13 Among them, micelles self-assembled from biodegradable star-shaped polymers enabling a unique three-dimensional shape and highly branched structure can provide spacious harbor for encapsulating therapeutic agents. They also have a low critical micelle concentration (CMC), which results in longer blood circulation time after intravenous injection.14 Unfortunately, most polyesters exhibit high crystallinity and hydrophobicity, thus leading to lower drug-loading capacity.15–17

Considerable attention has been focused on copolymerization of two different lactones, which could alter the physicochemical properties of polyesters, including crystallinity and hydrophobicity. Unfortunately, those co-polyesters require a rather complicated synthesis and purification process. Alternatively, the emergence of β-benzyl ester malic acid lactone (β-MLABz) offers a new opportunity to remedy the drawbacks. β-MLABz is a side-protected malic acid lactone monomer, which can be used as a monomer to prepare biodegradable poly(β-benzyl ester malate) with many benzene rings in the side chains of polyesters via ring-opening polymerization, which can contribute to a greater thermodynamic driving force for drug loading via strong π–π stacking interaction as anticancer drugs with a complex aromatic π–π-conjugated structure.18–24 In particular, the introduction of poly(β-benzyl ester malate) into biodegradable polyester can alter the physical/chemical properties. A series of poly(β-malic acid)-based polyesters were synthesized by ring-opening polymerization of β-MLABz, lactide, and ε-caprolactone. Results showed that the introduction of poly(β-malic acid) (PMA) can greatly decrease the crystallinity of PLLA and PCL.25,26 Therefore, the introduction of β-MLABz monomer to construct biodegradable polyesters can decrease the crystallinity of polyester and provide strong π–π stacking interaction between drugs and hydrophobic polyester, thus resulting in greatly improved DLE.

Obstacles to successful cancer therapy are evident when nanocarriers cannot specifically anchor to tumor sites and the amount of drugs at the tumor site cannot achieve the therapy window, leading to an inconspicuous antitumor effect. An effective way to resolve these abovementioned problems is the design of active-target and tumor microenvironment-responsive nanocarriers. More importantly, cyclic RGD (cRGD) has better tumor-targeting efficacy than the linear RGD peptide, due to high resistance to proteolysis and conformational restriction.27 Therefore, when polymeric NPs are decorated with RGD, the tissue-penetrating and targeting abilities of drug-loaded NPs can be improved. The design of microenvironment-responsive drug delivery systems is becoming increasingly popular as an option to achieve stimulus-responsive drug release at tumor sites.28–33 Utilization of higher glutathione (GSH) levels in intracellular environments (~2–10 mM) to design reductive-sensitive nanocarriers can accelerate the disassembly of polymeric micelles and drug release, exerting further therapeutic effects.34 There is an urgent need for the design of a new biodegradable polyester, which satisfies all the required attributes in a simple nanocarrier platform that can overcome the obstacles of cancer therapy and achieve effective therapy.

Herein, we combined the advantages of star-shaped polymer structure, strong π–π stacking interaction between hydrophobic segment and hydrophobic drug, and utilization of tumor microenvironment to design an intelligent all-in-one nanosystem via a facile star-shaped strategy (Scheme 1). Among them, the hydrophobic drug (doxorubicin [DOX]) can be efficiently encapsulated into the core of particles, which was self-assembled by hydrophobic segments composed of biodegradable star-shaped poly(l-lactide)-co-poly(RS-β-benzyl malolactonate). The hydrophilic segments were constructed from PEG modified by RGD and disulfide bond, to achieve the stealth-like character of nanocarriers, enhancing the cell internalization and triggered release of drugs in response to an intracellular reduction environment. Hydrophilic PEG with a reduction-cleavable disulfide linkage (SPEG) can be detached under a reduction tumor environment to prompt drug release and achieve successful tumor therapy, after being internalized into tumor cells. The physicochemical properties of nanocarriers and antitumor efficiency in vitro were studied.

Scheme 1.

The reduction-sensitive RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles (A) and the concept for a proposed behavior of polymeric nanoparticles for anticancer drug doxorubicin delivery (B).

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; GSH, glutathione; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Materials and methods

Materials

Methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) (mPEG, Mw =2,000 g/mol), PEG (OH-PEG-OH, Mw =2,000 g/mol), benzyl malolactonate, l-lactide (l-LA) (99%; Purac, Gorinchem, Zuid-Holland, the Netherlands), Tin(II) 2-ethylhexanote (Sn(Oct)2), N,N-dicyclohexyl carbodiimide (DCC), and 4-dimethyl aminopyridine (DMAP) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA) and used as received. Citraconic anhydride (CA, 97%), 6-maleimidocaproic acid (98%), and 2,2′-dithiodipropionic acid (98%) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI, Shanghai, China). DOX hydrochloride (DOX⋅HCl; Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceutical, Zhejiang, China) was deprotonated according to the previously reported method.35 β-Benzyl malolactonate (β-MLABz) was synthesized according to our previous studies,36 and the detailed synthetic routes and procedures are illustrated in Scheme S1. The proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra of β-MLABz and Mal-PEG-ss-COOH are shown in Figures S1 and S2. Dialysis membranes (molecular weight cutoff [MWCO] =1,000, 2,000, and 3,500 Da) were commercially available from Spectrum/Por (Houston, TX, USA). Cell lines, NIH/3T3, 4T1, and MCF-7, were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Science Cell Bank for Type Culture Collection (Shanghai, China). DMEM, Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI 1640), FBS, and penicillin–streptomycin were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) and were directly used for cell incubation. All other chemicals and solvents were purchased from Kelong Chemical Co. (Chengdu, China) and were used without purification.

Characterizations

The 1H-NMR spectra were carried out on a Bruker Avance-400 MHz NMR spectrometer using CDCl3 and CD3COCD3 as solvents, and 0.5% tetramethylsilane was used as the internal standard. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet 8700; Thermo Fisher Scientific) within the range of 4,000–500 cm−1.

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) measurement was carried out on a Waters instrument equipped with a model 1515 pump, a 2414 refractive index detector, and a Waters model 717 autosampler; the eluent was CHCl3, and the flow rate was 1 mL min−1 at 25°C.

The size and size distribution of the micelles were determined by a dynamic light scattering (DLS) spectrometer (Zetasizer Nano ZS; Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) at 25°C. Each sample was measured three times to attain the average size. The morphology of NPs was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Synthesis of star-shaped biodegradable 4sPLMBz random polymer

In brief, prescribed amounts of pentaerythritol benzyl (0.03 g, 0.27 mmol), l-LA (2.14 g, 14.82 mmol), and RS-β-benzyl malolactonate (1.15 g, 5.58 mmol) with 0.1 wt% (respect to the total weight of monomers) stannous octoate as a catalyst were added into polymerization tubes under nitrogen atmosphere. The tubes were then sealed under vacuum and placed into an oil bath at 120°C for 24 hours. The viscous liquid (4sPLMBz) was dissolved in chloroform and precipitated into ethyl ether. The white precipitates were obtained after removing the solvents. The product was confirmed using 1H-NMR.

Synthesis of biodegradable star-shaped mPEG-4sPLMBz copolymers

mPEG2000 (1 g, 0.5 mmol), 4sPLMBz (1.5 g, 2.5 mmol), and DMAP (0.015 g, 0.123 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) (20 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere, and DCC (5 g, 0.0243 mol) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and added dropwise into the mixture in an ice bath and stirred for 1 hour. After being stirred for 48 hours, the reaction solution was filtered, saturated, and precipitated in cold anhydrous diethyl ether. To remove the excess mPEG, the solution was packaged into a dialysis bag (Mw =3,500 g/mol) and was dialyzed exhaustively against DCM. Finally, the powder was dried under vacuum.

Synthesis of cRGD and disulfide-bearing PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymers

Synthesis was done in two steps. First, the disulfide-functionalized PEG2000 (Mal-PEG2000-ss-COOH) was synthesized according to our previously reported method.36,37 For the synthesis of cRGD and disulfide-bearing PEG2000-ss-4sPLMBz, the Mal-PEG2000-ss-COOH (0.6 g, 0.3 mmol) was conjugated to the 4sPLMBz via coupling reaction. In detail, the molar ratio of the −COOH group of PEG to −OH groups of 4sPLMBz was 2:1, and both chemicals were dissolved in anhydrous DCM (30 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere. Then, DMAP (0.014 g, 0.1146 mmol) and DCC (1.375 g, 6.66 mmol) dissolved in DCM were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 hours and was further precipitated in cold anhydrous diethyl ether. Subsequently, the product and cRGD were dissolved into DMSO (10 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere, and the reaction mixture was stirred for another 24 hours at 25°C. The final product (RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz) was purified using the dialysis method. The obtained product was confirmed using 1H-NMR and FTIR.

Evaluation of CMC

The self-assembly of star-shaped amphiphilic mPEG-4-sPLMBz and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz was investigated in aqueous solution using pyrene as a probe. The CMC of the two copolymers was determined by fluorescence spectra (F-7000; Hitachi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The pyrene solutions in acetone were added to 5 mL volumetric flasks, and the acetone was allowed to evaporate. Then, 1 mL of micellar solution with different concentrations in the range of 1.53×10−6 to 1 mg/mL was added to the vials, and the final pyrene concentration was 6×10−7 M. The solutions were equilibrated at room temperature overnight. The fluorescence emission wavelength was fixed at 390 nm, and the excitation spectrum from 300 to 360 nm was tested. The emission fluorescence intensities at 335 and 337 nm were monitored, and the intensity ratios of I337/I335 were plotted as a function of logarithm of two copolymer concentrations.

Preparation of nanocarriers and drug-encapsulating nanocarriers

The nanocarriers were prepared by the solvent evaporation method. Briefly, 5 mg of amphiphilic copolymer was dissolved in 0.2 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF). After it was thoroughly dissolved, the solution was added dropwise into distilled water (10 mL). When the solvent was completely evaporated, the blank polymeric micelles were obtained.

The drug-loaded micelles were prepared using the dialysis method. Five milligrams of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz or mPEG-4sPLMBz and 1.25 mg of hydrophobic drug (DOX) dissolved in 0.5 mL of DMSO were dispersed slowly into 10 mL of water under ultrasound and stirred for another 4 hours. Subsequently, the mixture was transferred into dialysis tubing (MWCO =1,000) and dialyzed against distilled water for 12 hours to remove the organic solvent. The outer phase was replaced by fresh distilled water every 4 hours. After centrifugation, the resulting solution was lyophilized to obtain the solid powder of DOX-loaded micelles. The entire procedure was performed in a dark environment.

The amount of encapsulated DOX was confirmed by UV-vis measurement (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at a wavelength of 483 nm. The calibration curve was obtained from DOX–DMSO solutions with various DOX concentrations (y=0.0201x−0.005, R2=0.9999, x represented DOX concentration, µg/mL). Drug-loading content (DLC) and DLE were calculated according to the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Reduction triggered destabilization of polymeric micelles

To investigate stimuli sensitivities, two polymeric micelles were individually incubated in different biomimetic environments of 0.5 and 10 mM GSH at 37°C. The micellar solution without GSH was used as the control. At predetermined intervals, size of the polymeric micelles was determined by DLS. The morphology of cRGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles in 10 mM GSH solution was detected by TEM after 24 hours. Three parallel samples were used to obtain the average size, and the results were recorded as mean±SD. In order to further confirm responsiveness of mPEG-4sPLMBz and cRGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles under a reduction condition, the stability of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles was also determined by fluorescence spectra (F-7000; Hitachi Co. Ltd.) using Nile red (NR) as a probe. The concentration of NR was 6.3×10−4 M after being dissolved in THF, and then 10 µL of NR/THF solution was added dropwise to the micellar solution (1.5 mL). After the THF was completely volatilized, fluorescence detection was then performed. The fluorescence excitation wavelength was fixed at 550 nm, and the emission fluorescence at 560–700 nm was monitored.

In vitro drug release

The release profile of DOX-encapsulating micelles at different concentrations of GSH (0 mM and 10 mM) was carried out using the dialysis method. DOX-loaded micellar solution (DOX =50 µg) was put into dialysis tubing (MWCO =1,000). The tubings were immersed in vials containing 25 mL of different released media and put on a shaking bed at 37°C. At the prescribed intervals, a sample of released medium (1 mL) was taken out and replaced with an equal quantity of fresh corresponding PBS medium. The released DOX was determined by a fluorescence detector with excitation and emission wavelengths of 483 and 550 nm, respectively. The release experiments were all carried out under sink conditions to make sure that the DOX thoroughly dissolved.

In vitro evaluation of cytotoxicity and antitumor efficacy

The cytotoxicity of blank mPEG-4sPLMBz and cRGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles was tested by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) assay against NIH/3T3 fibroblast cells and 4T1 breast cancer cells. In brief, NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and 4T1 cells were separately inoculated into 96-well plates at 4×104 cells/mL. After being incubated for 12 hours, the medium was removed and was replaced with 100 µL of a medium containing different concentrations of blank micelles. After incubation for another 48 hours, the culture medium was removed again, and the wells were washed with cold PBS (pH =7.4) three times. Afterward, 100 µL of CCK-8 dilution in serum-free DMEM (10%) was added to each well. The absorbance was measured by Thermo Scientific MK3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 450 nm using a microplate reader after incubation for an additional 2 hours in the dark.

To study the in vitro anticancer efficacy of DOX-loaded micelles, DOX⋅HCl, DOX-loaded mPEG-4sPLMBz, and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles were dissolved in the culture medium with the final DOX concentration ranging from 0.01 to 100 µg/mL. After 4T1 cells with the cell density of 4×104 cells/mL were planted into a 96-well plate for incubating over 12 hours, DOX⋅HCl and DOX-loaded micellar solutions in DMEM with various DOX concentrations were added to the plates and incubated for 48 hours. The cell viability was also measured by CCK-8 assay.

In vitro cellular uptake

To quantify the internalization, 4T1 cells were cultured on glass dishes (d=35 mm) at a cell density of 2×104 cells/mL and incubated for 24 hours. The medium was then replaced with fresh culture media containing DOX⋅HCl and DOX-loaded micelles (DOX =10 µg/mL). After being incubated for 1 and 4 hours, respectively, the medium in the well was removed; the dishes were washed with cold PBS three times; and then 1 mL of fresh PBS was added into each dish used for CLSM observation (TCP SP5; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). DOX was excited at 480 nm with emission at 590 nm. To quantitatively analyze the uptake of polymeric micelles, the cells were digested with trypsinization and rinsed with cold PBS twice; they were then resuspended in 0.3 mL of PBS after centrifugation (1,000 rpm/min, 5 minutes). The fluorescence intensity of DOX was tested, and the excitation wavelength of DOX was designed at 483 nm with an emission wavelength of 590 nm by a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The mean fluorescence intensities were calculated from three parallel samples.

Results and discussion

Characterization of RGD/disulfide-bearing star-shaped amphiphilic copolymers

To obtain a versatile polyester nanocarrier, a new star-shaped polyester containing RGD and disulfide bridge was designed and synthesized using ring-opening polymerization and coupling reaction. The synthetic routes are illustrated in Schemes 2 and S1. The synthetic routes of mPEG-4sPLMBz are also illustrated in Scheme S3. The modified PEG with double bond and disulfide linkage (Mal-PEG-ss-COOH) is shown in Scheme S2 and Figure S2, and the corresponding structure was confirmed by 1H-NMR, as shown in Figure 1. The structure of β-benzyl malolactonate moiety was characterized by 1H-NMR (Figure S1). As shown in Figure 1C, proton signals of star-shaped 4sPLMBz emerged at δ=1.45–1.65 and δ=5.06–5.22 ppm, which was attributed to the −CH3 (6) and −CH (5) protons of LLA repeated unit, respectively. The chemical shift of CH2 in pentaerythritol was at δ=4.08–4.20. The signals at δ=5.45–5.65 and δ=2.75–3.10 ppm were the −CH (2) and −CH2 (4) protons of MA repeated unit in the copolymer main chain. The protons of pendant groups −CH2 (3) and benzene ring (−C6H5) (1) appeared at δ=5.09 and 7.2–7.4 ppm, respectively. As shown in Figure 1B, after PEG conjugated to the star-shaped copolymer, a characteristic peak assigned to the ester linkage in the polymer (in −CH2CO−) was observed, indicating a successful coupling reaction. Additionally, the proton signals attributed to RGD in the RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymer were also detected (Figure 1B), whereas no typical proton peaks were found in the mPEG-4sPLMBz copolymer (Figure 1A). Meanwhile, the typical peaks assigned to the protons of −OCH2CH2O− in the PEG segment were observed at δ=3.6–3.8. The abovementioned results indicate a successful synthesis of the RGD/disulfide-bearing star-shaped copolymer. Additionally, FTIR spectra and GPC traces of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz and mPEG-4sPLMBz copolymers are also shown in Figure 2 and Table S1. The polymer molecular weights of GPC agreed well with 1H-NMR and the theoretical values, respectively. This versatile star-shaped copolymer design can be extended to develop more multifunctional star-shaped nanocarriers involving other dynamic bonds and active molecules.

Scheme 2.

The synthetic routes of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymer.

Abbreviations: cRGD, cyclic RGD; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Figure 1.

1H-NMR spectra of (A) mPEG-4sPLMBz, (B) RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz, and (C) 4sPLMBz⋅(CDCl3).

Abbreviations: 1H-NMR, proton nuclear magnetic resonance; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra (A and B) of mPEG-4sPLMBz and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymers, and GPC traces of (C) mPEG, 4sPLMBz, mPEG-4sPLMBz, and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymers.

Abbreviations: FTIR, Fourier transform infrared; GPC, gel permeation chromatography; min, minutes; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

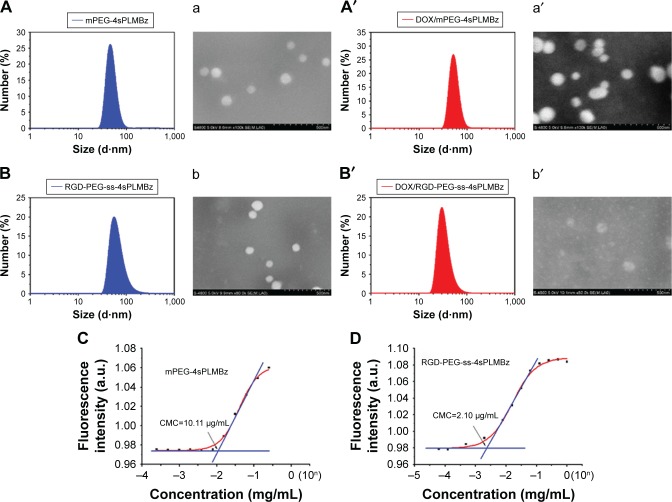

Physicochemical and stimulus-responsive properties of star-shaped copolymer micelles

The star-shaped amphiphilic polyester can self-assemble into micelles in aqueous solution. The CMC is one of the key thermodynamic constants determining the stability of self-assemblies.38 The CMC values of mPEG-4sPLMBz and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz were 10.11 and 2.10 µg/mL, respectively (Figure 3C and D). The ultralow CMC of the star-shaped copolymer could be reasonably attributed to the architecture of the copolymer, which can lead to good thermodynamic stability in circulation.

Figure 3.

The size and morphology of (A, a, A′, and a′) mPEG-4sPLMBz, (B, b, B′, and b′) RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz blank and DOX-loaded polymeric micelles, respectively. CMC of (C) mPEG-4sPLMBz and (D) RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz.

Abbreviations: CMC, critical micelle concentration; DOX, doxorubicin; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The mean diameters of blank and DOX-loaded micelles were measured by DLS. As shown in Figure 3A, B, A′, and B′, all the micellar sizes were lower than 100 nm and monodisperse. After being DOX loaded, the mean diameters of polymeric micelles were smaller than those of the corresponding blank micelles, due to DOX encapsulation and hydrophobic interaction with the copolymer, resulting in the formation of compact cores. After 48 hours, the size of micelles had no significant change (Figure S3). The morphology and size of polymeric micelles characterized using SEM presented spherical nanostructures and narrow size distribution, with a diameter of ~100 nm (Figure 3a, b, a′, and b′). Additionally, as shown in Table 1, the DLCs of mPEG-4sPLMBz/DOX and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz/DOX were up to 17.1% and 17.35%, respectively, which was higher than that of linear polyester.39 This is because many benzene groups distributed in the hydrophobic segment of copolymer enabled the polymeric micelles to provide strong π–π stacking interaction for the hydrophobic drug. The architecture of star-shaped copolymer further endowed polymeric micelles to offer a spacious harbor for hydrophobic drugs. Considering the excellent stability, nanosize (100 nm) scale and high DLC behaviors of the polymeric micelles, we can conclude that the designed polymeric micelles can efficiently aggregate and play a role in tumor sites.

Table 1.

The properties of mPEG-4sPLMBz and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymer micelles

| Copolymer micelles | Blank | DOX-loaded | CMC (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) PDI | Size (nm) PDI | ||||

| mPEG-4sPLMBz | 57.86 0.26 | 55.10 0.25 | 10.11 | 17.10 | 47.80 |

| RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz | 55.31 0.38 | 47.91 0.30 | 2.10 | 17.35 | 47.90 |

Abbreviations: CMC, critical micelle concentration; DLC, drug-loading content; DLE, drug-loading efficiency; DOX, doxorubicin; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PDI, polydispersity index; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

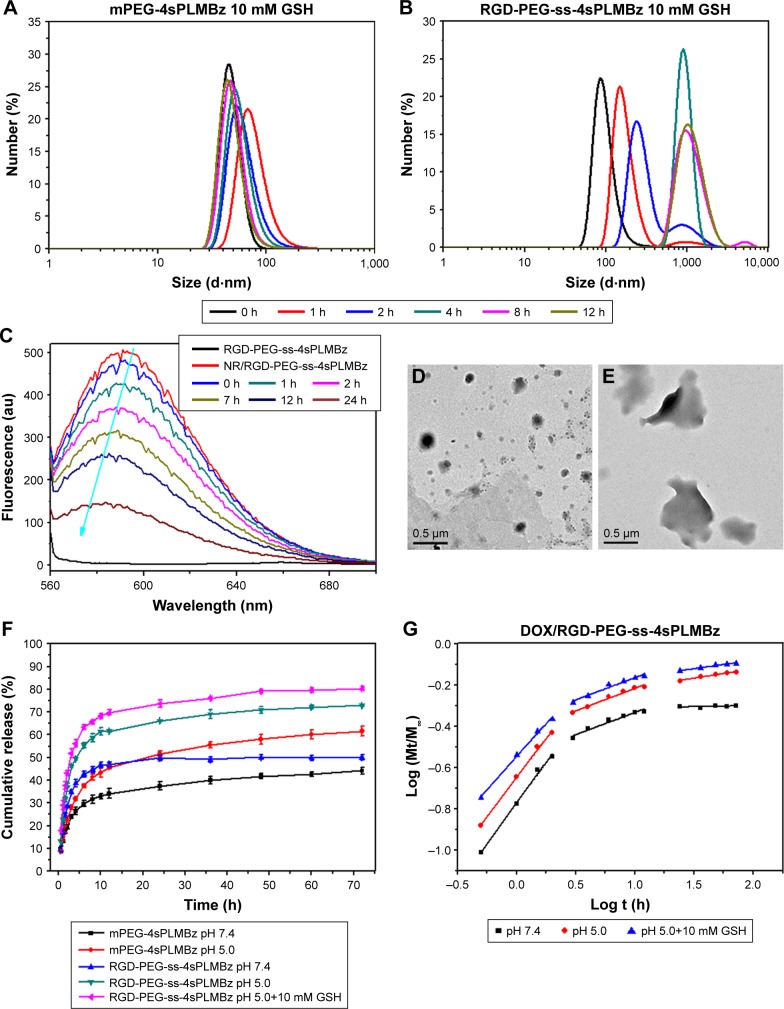

Stability and drug release profiles of polymeric micelles

To verify the on-demand intracellular dissociation ability of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz, the stimuli-responsive size and structure transition of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz polymeric micelles under different biomimetic environments were investigated. As shown in Figures 4A, B and S4, there is little influence on the diameter of insensitive polymeric micelles (mPEG-4sPLMBz). By contrast, as shown in the DLS result (Figure 4B) and TEM image (Figure 4D and E), although incubation of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz with GSH (0 and 0.5 mM) caused no obvious change in diameter, there was a dramatic increase in diameter to several micrometers as storage time increased, when the polymeric micelles were incubated with 10 mM GSH, due to GSH-triggered dissociation of the polymeric micelles that cause PEG deshielding, in which the core of the particles can aggregate together and exhibit larger particle size. This process may be beneficial to drug release, thus helping to accumulate the drug in cells and overcome drug resistance. This phenomenon agreed well with redox-responsive behaviors of linear polymeric assemblies.40,41

Figure 4.

The size changes of (A) mPEG-4sPLMBz and (B) RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles in different concentrations of GSH solutions. Fluorescence spectra (C) of the NR/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles in 10 mM GSH solution. The TEM (D and E) of RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles in 10 mM GSH solution after 0 and 24 hours. (F) The release profiles of DOX from DOX-loaded micelles in different conditions at 37°C in vitro. The results are expressed as mean±SD (n=3) (G) plots of log (Mt/M∞) against log t for DOX release from RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz polymeric micelles.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; GSH, glutathione; h, hours; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); NR, Nile red; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Meanwhile, after exposure to 10 mM GSH at different incubation times, fluorescence spectra in Figure 4C show that the blank micelles (RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz) had no obvious fluorescence intensity, but the fluorescence intensity of NR/polymeric micelles decreased significantly as the storage time increased, indicating the disassembly of micelles due to redox cleavage of disulfide linkages and further accelerated release of NR. This was consistent with the results of micellar size and stability.

In vitro DOX release profiles of polymeric micelles by dialysis tubes (MWCO of 1,000 Da) in different pH media (pH =7.4, 5.0, and 5.0+10 mM GSH) were determined. The results in Figure 4F revealed that the drug release behavior was closely related to pH value and GSH concentration. As expected, the release rate of DOX-loaded micelles in pH =5.0 was faster than that in pH =7.4, possibly due to protonation of DOX and the likelihood of acid-catalyzed ester hydrolysis.42 Compared to insensitive polymeric micelles, 10 mM GSH would trigger the release of native DOX from redox-sensitive polymeric micelles with 80% DOX released because of the redox-sensitive bonds and sudden polymeric micelle disassembly, which was confirmed by TEM and DLS results.

The mechanism of drug release was also evaluated by the classical equation: Mt/M∞ =ktn.43 The fitting curves and corresponding data (k, n) are exhibited in Table 2 and Figures S5 and 4G. Three different stages and different drug release processes were observed in DOX/mPEG-4sPLMBz and DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz polymeric micelle systems at different pH values and GSH concentrations. During the first 2 hours, all release processes were controlled by the superposition of diffusion and swelling release (0.43<n<0.85) and by Fickian diffusion-controlled release in the following two stages. As for DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz in pH =5.0+10 mM GSH, the drug release was consistent with the abovementioned release patterns. The relatively fast DOX release rate at pH 5.0 with 10 mM GSH suggests that the reduction-sensitive RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles can realize the desired release behavior in the intracellular environment of tumor cells, consistent with previous stability studies (Figures 4B; S4 B and C).

Table 2.

Release exponent (n), rate constant (k), and correlation coefficient (R2) for the two drug-loaded micelles

| Samples | Time interval (hours) | pH=7.4 | pH=5.0 | pH=5.0+10 mM GSH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | k | R2 | n | k | R2 | n | k | R2 | ||

| mPEG-4sPLMBz | 0–2 | 0.526 | 0.135 | 0.991 | 0.693 | 0.140 | 0.999 | – | – | – |

| 3–12 | 0.251 | 0.186 | 0.987 | 0.347 | 0.196 | 0.985 | – | – | – | |

| 24–72 | 0.148 | 0.235 | 0.990 | 0.160 | 0.311 | 0.996 | – | – | – | |

| RGD-PEG-ss- 4sPLMBz | 0–2 | 0.789 | 0.169 | 0.993 | 0.756 | 0.225 | 0.995 | 0.639 | 0.285 | 0.993 |

| 3–12 | 0.215 | 0.282 | 0.953 | 0.219 | 0.367 | 0.973 | 0.215 | 0.417 | 0.966 | |

| 24–72 | 0.009 | 0.480 | 0.999 | 0.088 | 0.500 | 0.988 | 0.082 | 0.568 | 0.953 | |

Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Antitumor efficiency of polymeric micelles

Encouraged by the on-demand drug release behavior of redox-activated polymeric micelles and the tumor-homing ability of cRGD, cytotoxicity of blank nanocarriers was evaluated against NIH/3T3 fibroblasts and 4T1 breast cancer cells using CCK-8 assay. As displayed in Figure 5A and B, the blank nanocarriers including insensitive and redox-activated polymeric micelles showed high cell viability (>90%) against 4T1 and 3T3 cells, demonstrating negligible cytotoxicity of the two formulations. Once good cytocompatibility of the nanocarriers was confirmed, the in vitro anticancer activity of the two DOX-loaded micelles was tested in 4T1 cells, and MCF-7 cells expressed different αvβ3 integrins to explore tumor targeting capability.44 As shown in Figure 5, the antitumor efficiency of both DOX-loaded micelles depended on drug concentration. For 4T1 cells, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of the DOX⋅HCl, DOX/mPEG-4sPLMBz, and DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz were 0.16, 1.15, and 0.73 µg/mL, respectively. For MCF-7 cells, the IC50s were 0.320, 1.22, and 0.98 µg/mL (Table 3). Among them, DOX⋅HCl exhibited the best anticancer efficiency due to its water solubility, allowing quick diffusion into cells and induction of cell apoptosis. Specifically, the IC50 values of DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz against 4T1 and MCF-7 cells were lower than those of DOX/mPEG-4sPLMBz. These results can be attributed to the synergistic effect of the cRGD having tumor-homing ability and the disulfide bond being responsive to the intracellular reducing environment, which could facilitate efficiency of the drug delivery system.

Figure 5.

In vitro antitumor activity of blank mPEG-4sPLMBz and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz polymeric micelles incubated with NIH/3T3 (A) cells and 4T1 (B) cells for 48 hours. The anticancer activity of DOX⋅HCl, DOX-loaded micelles against (C) MCF-7 cells and (D) 4T1 cells in vitro. The results are expressed as mean±SD (n=5).

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; DOX⋅HCl, DOX hydrochloride; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Table 3.

IC50s of DOX-loaded polymeric NPs for MCF-7 cells and 4T1cells

| Polymeric NPs | DOX⋅HCl (μg/mL) | DOX/mPEG-4sPLMBz (μg/mL) | DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 cells | 0.32 | 1.22 | 0.98 |

| 4T1 cells | 0.16 | 1.15 | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; DOX⋅HCl, DOX hydrochloride; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); NPs, nanoparticles; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

In vitro cellular uptake

To explore the mechanism underlying the improved anticancer efficacy of DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz, the intracellular-activated delivery system was tracked by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and flow cytometry, and DOX was used as a fluorescence probe. The two cancer cell lines, 4T1 and MCF-7 cells, presenting different expressions of αvβ3 integrin were chosen. As shown in Figure 6a1–a3, b1–b3, and c1–c3, DOX⋅HCl exhibited the highest fluorescence intensity in the nucleus among the three groups for 1 and 4 hours. As expected, the red fluorescence signal from the DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelle group was much stronger than that from the DOX/RGD-PEG-4sPLMBz micelle group. Flow cytometry also showed that the DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelle group drastically enhanced the internalization of DOX into both 4T1 and MCF-7 cancer cells within 1 and 4 hours (Figure 6A–F) of 4T1 cells (Figure 6E) and MCF-7 cells (Figure 6F). The fluorescence intensity from the three groups increased with an increase of incubation time from 1 to 4 hours. It is interesting to note that, compared to MCF-7-expressed lower αvβ3 integrins, the fluorescence intensity from RGD-decorated micelles was stronger than that of mPEG-4sPLMBz micelles in 4T1 cells, which indicates that surface decoration with RGD can enhance internalization efficiency of micelles due to the tumor-homing ability of RGD. Those results clearly reflect the role of cRGD-αvβ3 integrin interaction in terms of enhancing cellular uptake. The increase in GSH concentration in tumor cells caused disulfide bond breakage and resulted in the micelles disintegrating and releasing DOX, which was in good agreement with IC50 results.

Figure 6.

The confocal laser scanning microscopy images of 4T1 cells and MCF-7 cells treated with DOX⋅HCl (a1–a3), DOX/RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz (b1–b3), DOX/mPEG-4sPLMBz (c1–c3) for 1 and 4 hours. The 1 and 2 represent the images of DOX fluorescence channel and and bright field and merged; the scale bar was 25 µm. The flow cytometry results of 4T1 cells (A, B, and E) and MCF-7 cells (C, D, and F) treated with DOX-loaded nanoparticles for 1 (A and C) and 4 hours (B and D). Statistical analysis of 4T1 cells (E) and MCF-7 cells (F) (mean±SD, n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.001). The DOX concentration was 10 µg/mL.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; DOX⋅HCl, DOX hydrochloride; h, hours; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Conclusion

We have developed a novel star-shaped redox-activated biodegradable nanocarrier (RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz) with π–π interaction and tumor-homing peptide RGD to overcome the low drug-encapsulating efficiency dilemma and to enhance tumor internalization in breast cancer, as well as enabling high stability and stimulus-responsive release. RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz copolymer was based on the star-shaped biodegradable polyester functionalized by benzene ring and intracellular cleavable linkage. The resulting nanocarriers can not only provide strong interaction between the hydrophobic core and hydrophobic drug for enhancing DLE but also benefit drug aggregation in tumor cells due to dissociation of micelles in the intracellular environment. Additionally, the RGD/redox-activated nanocarrier possessed good biocompatibility, exhibited high internalization efficiency, and resulted in good anticancer effects in both 4T1 and MCF-7 cancer cells. This study provides a clear and useful strategy for designing a multifunctional star-shaped drug delivery system with good stability, high DLE, active-targeting, and stimulus-sensitive drug release for combating cancer.

Supplementary materials

1H-NMR spectra of β-MLABz.

Abbreviation: 1H-NMR, proton nuclear magnetic resonance.

1H-NMR spectra of Mal-PEG-OH and Mal-PEG-COOH.

Abbreviations: 1H-NMR, proton nuclear magnetic resonance; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The sizes of mPEG-4sPLMBz (A) and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz (B) after 48 hours.

Abbreviations: mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); h, hours; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The size changes of (A) mPEG-4sPLMBz and (B and C) RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles in different concentrations of GSH solutions.

Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; h, hours; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Plots of log(Mt/M∞) against log t for DOX released from mPEG-4sPLMBz polymeric micelles.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol).

The synthetic routes of β-MLABz.

Abbreviations: DCM, dichloromethane; THF, tetrahydrofuran.

The synthetic routes of Mal-PEG-ss-COOH copolymer.

Abbreviations: DCC, dicyclohexyl carbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethyl aminopyridine; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The synthetic routes of mPEG-4sPLMBz copolymer.

Abbreviations: DCC, dicyclohexyl carbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethyl aminopyridine; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol).

Table S1.

The polymer molecular weight and PDI of GPC measurement

| Polymer | Mn | PDI |

|---|---|---|

| RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz | 10,791 | 1.155 |

| mPEG-4sPLMBz | 9,451 | 1.337 |

| 4sPLMBz | 6,196 | 1.556 |

| mPEG | 2,345 | 1.029 |

Abbreviations: GPC, gel permeation chromatography; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PDI, polydispersity index; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (No 51403137) and Science and Technology foundation of Sichuan Province (2018RZ0044).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Feng X-R, Ding JX, Gref R, Chen X-S. Poly(β-cyclodextrin)-mediated polylactide-cholesterol stereocomplex micelles for controlled drug delivery. Chinese Journal of Polymer Science. 2017;35(6):693–699. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutikov AB, Song J. Biodegradable PEG-based amphiphilic block copolymers for tissue engineering Applications. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1(7):463–480. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Maciel D, Rodrigues J, Shi X, Tomás H. Biodegradable polymer nanogels for drug/nucleic acid delivery. Chem Rev. 2015;115(16):8564–8608. doi: 10.1021/cr500131f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang K, Tang X, Zhang J, et al. PEG-PLGA copolymers: their structure and structure-influenced drug delivery applications. J Control Release. 2014;183:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joralemon MJ, Mcrae S, Emrick T. PEGylated polymers for medicine: from conjugation to self-assembled systems. Chem Commun. 2010;46(9):1377–1393. doi: 10.1039/b920570p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunoqrot S, Bugno J, Lantvit D, Burdette JE, Hong S. Prolonged blood circulation and enhanced tumor accumulation of folate-targeted dendrimer-polymer hybrid nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2014;191:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JM, Giaccia AJ. The unique physiology of solid tumors: opportunities (and problems) for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 1998;58(7):1408–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhulina EB, Borisov OV. Theory of block polymer micelles: recent advances and current challenges. Macromolecules. 2012;45(11):4429–4440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur MK, Thakur VK, Gupta RK, Pappu A. Synthesis and applications of biodegradable soy based graft copolymers: a review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raffa P, Wever DA, Picchioni F, Broekhuis AA. Polymeric surfactants: synthesis, properties, and links to applications. Chem Rev. 2015;115(16):8504–8563. doi: 10.1021/cr500129h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanna K, Varshney S, Kakkar A. Miktoarm star polymers: advances in synthesis, self-assembly, and applications. Polym Chem. 2010;1(8):1171–1185. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng Y, Zhang S, Lu G, Huang X. Constructing well-defined star graft copolymers. Polym Chem. 2013;4(5):1289–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakur VK, Thakur MK. Recent advances in graft copolymerization and applications of chitosan: a review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2014;2(12):2637–2652. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duro-Castano A, Movellan J, Vicent MJ. Smart branched polymer drug conjugates as nano-sized drug delivery systems. Biomater Sci. 2015;3(10):1321–1334. doi: 10.1039/c5bm00166h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamboli V, Mishra GP, Mitra AK. Novel pentablock copolymer (PLA-PCL-PEG-PCL-PLA) based nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery: Effect of copolymer compositions on the crystallinity of copolymers and in vitro drug release profile from nanoparticles. Colloid Polym Sci. 2013;291(5):1235–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00396-012-2854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Y, Jiang X, Ding Y, et al. Preparation and drug release behaviors of nimodipine-loaded poly(caprolactone)-poly(ethylene oxide)-polylactide amphiphilic copolymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2003;24(13):2395–2404. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma C, Pan P, Shan G, Bao Y, Fujita M, Maeda M. Core-shell structure, biodegradation, and drug release behavior of poly(lactic acid)/poly(ethylene glycol) block copolymer micelles tuned by macromolecular stereostructure. Langmuir. 2015;31(4):1527–1536. doi: 10.1021/la503869d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Y, Long Y, Lei Y, et al. A novel micelle of coumarin derivative monoend-functionalized PEG for anti-tumor drug delivery: in vitro and in vivo study. J Drug Target. 2012;20(3):246–254. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2011.639023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng H, Li S, Pu Y, Lai Y, He B, Gu Z. Nanoparticles generated by PEG-chrysin conjugates for efficient anticancer drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;87(3):454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Su T, Li S, Lai Y, He B, Gu Z. Polymeric micelles with π–π conjugated moiety on glycerol dendrimer as lipophilic segments for anticancer drug delivery. Biomater Sci. 2014;2(5):775–783. doi: 10.1039/c3bm60267b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai Y, Lei Y, Xu X, Li Y, He B, Gu Z. Polymeric micelles with π–π conjugated cinnamic acid as lipophilic moieties for doxorubicin delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1(34):4289. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20392a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang Y, Lai Y, Li D, He B, Gu Z. Novel polymeric micelles with cinnamic acid as lipophilic moiety for 9-Nitro-20(S)-camptothecin delivery. Mater Lett. 2013;97:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei Y, Lai Y, Li Y, et al. Anticancer drug delivery of PEG based micelles with small lipophilic moieties. Int J Pharm. 2013;453(2):579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang Y, Deng X, Zhang L, et al. Terminal modification of polymeric micelles with π-conjugated moieties for efficient anticancer drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2015;71:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He B, Bei J, Wang S. Synthesis and characterization of a functionalized biodegradable copolymer: poly(l-lactide-co-RS-β-malic acid) Polymer. 2003;44(4):989–994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.He B, Chan-Park MB. Synthesis and Characterization of Functionalizable and Photopatternable Poly(ε-caprolactone-co-RS-β-malic acid) Macromolecules. 2005;38(20):8227–8234. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu YP, Wang Q, Liu YC, Xie Y. Molecular basis for the targeted binding of RGD-containing peptide to integrin αVβ3. Biomaterials. 2014;35(5):1667–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai H, Wang X, Zhang H, et al. Enzyme-sensitive biodegradable and multifunctional polymeric conjugate as theranostic nanomedicine. Appl Mater Today. 2018;11:207–218. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo Q, Xiao X, Dai X, et al. Cross-linked and biodegradable polymeric system as a safe magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(2):1575–1588. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b16345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo C, Sun L, Cai H, et al. Gadolinium-labeled biodegradable dendron-hyaluronic acid hybrid and its subsequent application as a safe and efficient magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(28):23508–23519. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b06496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C, Pan D, Li J, et al. Enzyme-responsive peptide dendrimer-gemcitabine conjugate as a controlled-release drug delivery vehicle with enhanced antitumor efficacy. Acta Biomater. 2017;55:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N, Cai H, Jiang L, et al. Enzyme-sensitive and amphiphilic pegylated dendrimer-paclitaxel prodrug-based nanoparticles for enhanced stability and anticancer efficacy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(8):6865–6877. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai Y, Cai H, Duan Z, et al. Effect of polymer side chains on drug delivery properties for cancer therapy. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2017;13(11):1369–1385. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2017.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaur S, Prasad C, Balakrishnan B, Banerjee R. Trigger responsive polymeric nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Biomater Sci. 2015;3(7):955–987. doi: 10.1039/c5bm00002e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shuai X, Ai H, Nasongkla N, Kim S, Gao J. Micellar carriers based on block copolymers of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and poly(ethylene glycol) for doxorubicin delivery. J Control Release. 2004;98(3):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng FR, Su T, Cao J, et al. Environment-stimulated nanocarriers enabling multi-active sites for high drug encapsulation as an “on demand” drug release system. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6(15):2258–2273. doi: 10.1039/c8tb00132d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hao N, Sun C, Wu Z, et al. Fabrication of polymeric micelles with aggregation-induced emission and forster resonance energy transfer for anticancer drug delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2017;28(7):1944–1954. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klymchenko AS, Roger E, Anton N, et al. Highly lipophilic fluorescent dyes in nano-emulsions: towards bright non-leaking nano-droplets. RSC Adv. 2012;2(31):11876–11886. doi: 10.1039/C2RA21544F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng F, Guan X, Cao H, et al. Characteristic of core materials in polymeric micelles effect on their micellar properties studied by experimental and dpd simulation methods. Int J Pharm. 2015;492(1–2):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai X, Dong C, Dong H, et al. Effective gene delivery using stimulus-responsive catiomer designed with redox-sensitive disulfide and acid-labile imine linkers. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13(4):1024–1034. doi: 10.1021/bm2017355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chuan X, Song Q, Lin J, et al. Novel free-paclitaxel-loaded redox-responsive nanoparticles based on a disulfide-linked poly(ethylene glycol)-drug conjugate for intracellular drug delivery: synthesis, characterization, and antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(10):3656–3670. doi: 10.1021/mp500399j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quader S, Cabral H, Mochida Y, et al. Selective intracellular delivery of proteasome inhibitors through pH-sensitive polymeric micelles directed to efficient antitumor therapy. J Control Release. 2014;188:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peppas NA. 1. Commentary on an exponential model for the analysis of drug delivery: Original research article: a simple equation for description of solute release: I II. Fickian and non-Fickian release from non-swellable devices in the form of slabs, spheres, cylinders or discs, 1987. J Control Release. 2014;190:31–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan F, Wu H, Liu H, et al. Molecular imaging-guided photothermal/photodynamic therapy against tumor by iRGD-modified indocyanine green nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2016;224:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1H-NMR spectra of β-MLABz.

Abbreviation: 1H-NMR, proton nuclear magnetic resonance.

1H-NMR spectra of Mal-PEG-OH and Mal-PEG-COOH.

Abbreviations: 1H-NMR, proton nuclear magnetic resonance; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The sizes of mPEG-4sPLMBz (A) and RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz (B) after 48 hours.

Abbreviations: mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); h, hours; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The size changes of (A) mPEG-4sPLMBz and (B and C) RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz micelles in different concentrations of GSH solutions.

Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; h, hours; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

Plots of log(Mt/M∞) against log t for DOX released from mPEG-4sPLMBz polymeric micelles.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol).

The synthetic routes of β-MLABz.

Abbreviations: DCM, dichloromethane; THF, tetrahydrofuran.

The synthetic routes of Mal-PEG-ss-COOH copolymer.

Abbreviations: DCC, dicyclohexyl carbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethyl aminopyridine; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).

The synthetic routes of mPEG-4sPLMBz copolymer.

Abbreviations: DCC, dicyclohexyl carbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethyl aminopyridine; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol).

Table S1.

The polymer molecular weight and PDI of GPC measurement

| Polymer | Mn | PDI |

|---|---|---|

| RGD-PEG-ss-4sPLMBz | 10,791 | 1.155 |

| mPEG-4sPLMBz | 9,451 | 1.337 |

| 4sPLMBz | 6,196 | 1.556 |

| mPEG | 2,345 | 1.029 |

Abbreviations: GPC, gel permeation chromatography; mPEG, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol); PDI, polydispersity index; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol).