Abstract

Oncogene-induced cellular senescence (OIS) is a complex program that is triggered in response to aberrant activation of oncogenic signaling. Initially, OIS was thought to be a barrier to malignant transformation because of its suppression on cell proliferation. Later studies showed that senescence induced by oncogenes can also promote the initiation and development of cancer. The opposing effects of OIS occur through different combinations of downstream effectors as well as the interplay of senescent cells and the microenvironment, such as senescence-associated inflammation. Here, we review the common features and molecular mechanisms underlying OIS and the interaction between senescent cells and the microenvironment. We propose that targeting senescent cells may have a beneficial therapeutic effect during the treatment of cancer.

Keywords: cellular senescence, oncogene, SASP, tumor microenvironment, cancer therapy

Introduction

Cellular senescence was discovered by Leonard HAYFLICK and Paul MOORHEAD more than five decades ago and was identified as a stable exit from the cell cycle resulting from the limited proliferative capacity of normal human fibroblasts in culture. This particular type of cellular senescence is referred as “replicative senescence” and was demonstrated to be a consequence of shortened telomere length1,2,3. Cellular senescence can be induced by other types of stimuli, such as oncogenic stress. Oncogenic activation is well known as a critical mechanism for the initiation and development of cancer. Although the activation of oncogenes can stimulate cell proliferation, which is recognized as a tumor-promoting event and a necessary step in tumorigenesis in many cancer types, it may act as a genetic stress and cause irreversible growth arrest in cultured cells and tumor tissues1. For example, oncogenic mutations in Ras have been found to induce cellular senescence in cultured human primary lung fibroblasts IMR903; the hyper-expression of Ras in mammary epithelial cells triggered the activation of tumor suppression pathways and irreversible senescent growth arrest in vivo 4. This type of cellular senescence is termed premature senescence, and senescence induced by oncogenes is defined as oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). OIS can also be induced by the activation of other oncogenes, such as BRAF, AKT, E2F1 and cyclin E, and by the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, including PTEN and NF1 5. The expression level of oncogenes seemed to be important for the induction of OIS, as studies revealed that senescence induced by oncogenic Ras only occurred when Ras was overexpressed6.

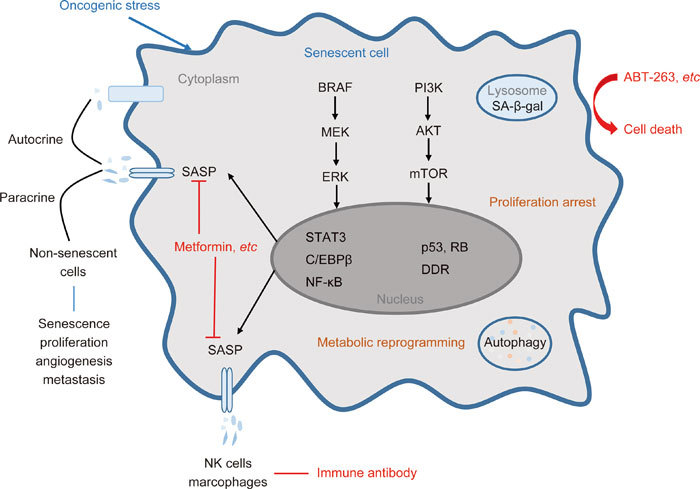

To date, a number of characteristics displayed by senescent cells have been identified both in vitro and in vivo, which are summarized in Figure 1. In addition to cell-cycle arrest, senescent cells exhibit increased activity of beta-galactosidase at pH 6.0, the activation of signaling pathways and the secretion of a mixture of growth factors, chemokines and cytokines7. These processes reflect the mechanisms that contribute to the induction and maintenance of OIS or accompany the execution of the OIS program. It has been demonstrated that the tumor suppressors p53 and RB are two major intrinsic cellular regulators of OIS, and studies have shown that both proteins actively induce OIS in vitro and in vivo, but their roles in OIS in human cancer cells have not been fully elucidated8,9. Kinases such as p38 and its downstream substrate PRAK as well as PI3K/AKT/mTOR have been reported to mediate OIS responses10,11. Recently, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been widely found to regulate OIS. For example, miR-34a has been reported to mediate B-RAF-induced cellular senescence by down-regulating the expression of MYC12. In addition, a number of secreted factors have been found to be associated with senescence induced by oncogenes, and these factors exhibit defined but heterogeneous profiles. These mixtures of growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases and proteases play critical roles in the crosstalk between senescent cells and immune cells or neighboring non-senescent cells13,14.

Figure 1.

Targeting cellular senescence in cancer. Senescent cells induced by oncogenic stress exhibit proliferation arrest with metabolic reprogramming. Oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) is often accompanied by the activation of signaling pathways such as BRAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR. OIS is usually featured with increased SA-β-gal activation; the accumulation of p53 and/or RB; the activation of DDR and autophagy; and SASP. The senescent phenotype could be different and is dependent on temporal, spatial and genetic contexts. Senescent cells could be eradicated by the induction of apoptosis by pan-BCL inhibitors such as ABT-263 or by the immune surveillance system. In addition, compounds such as metformin that are able to block SASP can eliminate the deleterious effect of cellular senescence.

Due to the complex features of senescent cells, senescence can be anti- or pro-tumorigenic under different conditions. OIS is initially thought to be a failsafe program against oncogenic stress because of its ability to restrict the proliferation of abnormal cells15. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) may also provoke tumor-suppressive responses, which could be beneficial in clearing senescent cells and restraining tumor growth16. Subsequent investigations found that senescence may be deleterious and compromise the efficacy of cancer therapy17. SASP provokes not only tumor-suppressive but also tumor-promoting responses, which are dependent on the profile of secreted factors. Secreted factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEFG), interleukin-8 (IL-8), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) have been shown to promote tumor progression by stimulating the proliferation of endothelial cells18, contributing to angiogenesis19, promoting the invasion of tumor cells20 or inducing the formation of cancer stem cells13. Moreover, factors including CXCL121 and ECM-degrading enzymes22 have been reported to recruit immune cells such as macrophages and NK cells to create an immunosuppressive microenvironment around senescent cells and promote the escape of tumor cells from immune surveillance23.

RB and p53 are two major regulators in OIS

Despite the complexity of factors involved in OIS, RB and p53 are two main and widely acknowledged regulators, which are responsible for cell-cycle arrest in senescent cells24,25,26. The accumulation of p53 was found in cells undergoing OIS, which could be bypassed when p53 was inactivated. For instance, mice harboring oncogenic Ras G12D developed lung cancer, in which premalignant adenomas expressing p53 were positive for markers of cellular senescence, whereas malignant adenocarcinomas that arose in the absence of p53 were negative for senescence27,28. Senescent cells are often accompanied by the induction of p16, which affects the maintenance of cellular senescence. Cells expressing low levels of p16 would circumvent senescence and resume proliferation9. RB exists downstream of p16 and plays a crucial role in cellular senescence. The accumulation of RB was found in senescent cells, and cells would bypass senescence if RB was absent29. During cellular senescence, RB preferentially associates with E2F-targeted genes involved in DNA replication and is uniquely required to repress these genes. Loss of RB leads to inappropriate DNA synthesis upon the triggering of senescence and the disruption of a p21-mediated cell-cycle checkpoint, thereby enabling extensive proliferation and rampant genomic instability29.

The DNA damage response is an omnipresent mechanism underlying OIS

OIS is associated with the DNA damage checkpoint response (DDR) after a hyper-replicative phase occurred immediately upon activation of oncogenes, which would lead to augmented numbers of active replicons and alterations in DNA replication fork progression. The experimental inactivation of DDR could abrogate OIS and promote cell transformation30. OIS was suppressed when ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), a kinase that senses DNA double-strand breaks, was inhibited, which led to increased tumor growth and invasion in mice31. A recent study has shown that the degradation of ATM by E3 ubiquitin ligase WD repeat and SOCS box-containing protein 1 (WSB1) contributed to the abrogation of OIS and led to abnormal proliferation and transformation31. An analysis of human precancerous lesions revealed that DNA damage and senescence occurred concurrently32. ATM and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related) are able to activate GATA4, which is stabilized in cells undergoing senescence. GATA4 was reported to activate NF-κB to initiate SASP and facilitate senescence, indicating its role downstream of DNA damage33.

Autophagy is activated in senescent cells

Although proliferation arrest is the main feature of OIS, senescent cells are metabolically active, which is in line with its enlarged morphology. Recently, autophagy was found to be activated during senescence. Autophagy encompasses different routes that cells use to deliver cytoplasmic substrates to lysosomes for degradation, which creates a way for cells to meet the bioenergetic demand when cells have dwindling external or internal resources. Accordingly, autophagy is a protective process against stress and plays key roles in energy homeostasis and quality control of cellular components34. A subset of autophagy-related genes is up-regulated during senescence. The overexpression of ULK3 induced autophagy and senescence, while the inhibition of autophagy delayed the OIS-related phenotype, including senescence-associated secretion, suggesting that autophagy and its effectors mediated the acquisition of the senescence phenotype35. However, the functional relevance of autophagy and OIS remains unclear. As mentioned previously, the induction of autophagy could reinforce the onset of senescence. Meanwhile, the suppression of autophagy may trigger a stress response, which may facilitate the induction of senescence if cells are sensitive enough to such stress36. Thus, autophagy imposes a context-dependent impact on OIS.

SASP enables the communication of senescent cells with the microenvironment

Cells undergoing senescence are metabolically active and secrete multiple factors, including pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8), chemokines (monocyte chemoattractant proteins, MCPs and macrophage inflammatory proteins, MIPs), growth factors (transforming growth factor-β, TGF-β and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, GM-CSF) and proteases, and the process is referred to as SASP37. The profiles of factors secreted by senescent cells vary depending on circumstances. For example, BRAF V600E-induced senescence in different cell lines was associated with diverse secreted factors. The expression of BRAF V600E in human primary foreskin fibroblasts led to the synthesis and secretion of IGFBP738, while BRAF V600E-induced senescence in human diploid fibroblasts IMR90 was linked specifically to the activation of an inflammatory transcriptome, including IL-6 and IL-839. Factors induced by senescence may paradoxically regulate senescence. IL-6, IGFBP7 and CXCR2 have been demonstrated to be required for OIS, which induced senescence or apoptosis and modulate cell proliferation and migration via autocrine and paracrine38,39,40.

SASP is tightly regulated at epigenetic, transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, contributing to diverse outputs of senescence. A recent study found that OIS triggered a global remodeling of the enhancer landscape with the recruitment of BRD4 to newly activated super-enhancers adjacent to key SASP genes41. Transcriptional profiling and functional studies indicated that BRD4 was required for SASP and downstream paracrine signaling. At the transcriptional level, IL-6 or IL-8 is largely regulated by NF-κB and C/EBPβ, while CCL2 or GM-CSF is typically mediated by STAT316,23. Moreover, SASP factors seem to form a hierarchical network, in which SASP factors including interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and IL-6 appeare to be capable of regulating other secreted factors to transduce and amplify the signal42. The transcriptional activity of NF-κB has been demonstrated to be regulated by IL-1α, where the reduction of membrane-bound IL-1α diminished NF-κB activity, resulting in the decreased secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-842. C/EBPβ was reported to act as a transcription factor and cooperate with IL-6 to amplify the activation of the inflammatory network39.

These factors secreted by senescent cells mainly function by affecting neighboring non-senescent cells and immune cells through paracrine signaling, while senescent cells can also act on themselves in an autocrine manner. TGF-β has been shown to trigger senescence in neighboring proliferating cells in a paracrine manner through a mechanism that generates ROS and DNA damage43. Therefore, senescence can be propagated to neighboring cells mediated by SASP and be further reinforced. SASP factors are able to recruit immune cells to clear senescent cells and terminate inflammation. For example, ECM-degrading enzymes secreted by senescent cells have been reported to recruit NK cells to remove senescent cells and thus serve to limit ECM deposition and prevent fibrosis22.

OIS counteracts cancer progression

Although there are few markers omnipresent in all types of OIS, the stable state of proliferation arrest is a core aspect of the senescent phenotype. Unlike quiescence, senescent growth arrest is essentially permanent because senescent cells cannot be stimulated to proliferate in most cases. In many tissues, small and inconspicuous neoplastic lesions, where oncogenic mutations and senescence markers have been identified, rarely become overt cancers27, indicating that senescence caused by aberrant oncogenic activation tends to prevent uncontrolled proliferation through irreversible growth arrest.

Senescence affects tumor development by not only cell-autonomous but also non-cell-autonomous activities, which create spatiotemporally dynamic and context-dependent tissue reactions. Factors such as TGF-β and CCL2 could propagate senescent phenotype to neighboring non-senescent cells, passing oncogenic stress to the microenvironment7. Immune cells recruited by senescent cells have been increasingly recognized to play a pivotal role in regulating tumor development. The overexpression of oncogenic RAS in mice failed to promote the development of hepatocarcinoma because of senescence-induced immune surveillance, in which CD4+ T cells and macrophages played vital roles in overriding senescent hepatocytes44. NK cells could be recruited by CCL2 secreted by senescent cells to assist in clearance of tumor cells, while M1 macrophages could be recruited by CXCL1 to suppress tumor development21,45. However, failure to senescence is usually insufficient for malignant transformation. It appears that senescence poses a formidable but not insurmountable barrier to cancer progression. It has been shown that the activity of wild-type p53 was detrimental to the chemotherapy response in breast cancer patients even if p53 induced senescence in tumors, where the secreted cytokines of senescent cells were able to stimulate cell proliferation and tumor relapse46.

OIS promotes cancer development

It has been reported that it is very likely for cancer to develop even when OIS occurs. Specifically, in aged organisms, the cell replacement system that involves the clearance of senescent cells and the mobilization of progenitors to re-establish cell numbers may become inefficient or may exhaust the regenerative capacity of progenitor cells, eventually resulting in the accumulation of senescent cells that may aggravate damage and contribute to tumor development47.

Given the high varieties in SASP and different profiles of SASP in diverse cell types, SASP may provoke either tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting responses. SASP factors have been shown to promote tumorigenesis by inducing proliferation, survival, angiogenesis and metastasis16. For example, primary mouse keratinocytes transiently exposed to SASP exhibited increased expression of markers for stem cell and regenerative capacity in vivo 13. The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) secreted by senescent cells would mediate migration and enhance their tumorigenic properties48. Factors such as IL-6 and IL-8, which are regulated by mTOR in senescent fibroblasts, were found to promote prostate tumors in mice42. SASP may also promote tumorigenesis by its influence on the immune system. For example, CCL2 could recruit M2 macrophages, which creates an immunosuppressive microenvironment and acts as a promoter in tumor progression49. CCL2 secreted by senescent hepatocytes has also been reported to recruit immature myeloid cells to promote the development of hepatocellular carcinoma through the inhibition of NK cells. Consistently, SASP was reported to be associated with poor survival and early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma50.

Targeting cellular senescence in cancer

Though senescence induced by oncogenes may block cell proliferation, long-term senescence may result in a favorable microenvironment for tumorigenesis, mainly through SASP, which may promote the proliferation of neighboring non-senescent cells and/or provoke immune escape. Therefore, targeting senescent cells and eliminating the deleterious aspect of senescence may be a potential strategy for cancer therapy. Though the understanding of senescence has been greatly advanced in recent years, the specific targets essential for the induction of senescence remain undefined. As shown in Table 1, the current strategy is to target senescence indirectly via clearing senescent cells or blocking SASP.

Table 1.

Strategies of targeting cellular senescence.

| Strategy | Approach | Example | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elimination of senescent cells | Apoptosis inducer | ABT-263, dasatinib | 51, 52, 53, 54 | |

| Immune system-mediated | Specific antibody | CD44 antibody | 55 | |

| clearance | Specific antibody with cytotoxic agent | DPP4 antibody coupled to cytotoxicity | 56 | |

| SASP attenuation | Targeting SASP induction | NF-κB inhibitors | Glucocorticoids, metformin | 57 |

| mTOR inhibitors | Rapamycin | 42 | ||

| Blocking activity of SASP | Inhibitors of secretory factors | Anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, IL-6 inhibitor | 58 | |

It has been reported that clearing senescent cells may be beneficial in alleviating tissue inflammation and organ dysfunction and may reduce cancer risk. For example, pan-BCL inhibitors such as ABT-263/ABT-737 were found to induce apoptosis in senescent cells both in vitro and in vivo and could selectively eliminate senescent cells. These inhibitors have already been tested with success against small cell lung cancer51,52. Other compounds, including dasatinib, have been shown to override senescence, and dasatinib has been used against acute myeloid and lymphoid leukemia53,54. This strategy could be controversial because the compounds were not specific to induce senescent cells to undergo cell death, and they may function in other ways to restrain tumor growth. The immune surveillance system could be utilized to eradicate senescent cells as well. For example, antibodies against senescence-specific antigens, such as CD44 in endothelial cells, could induce a direct immune response to eliminate senescent cells and enhance the antitumor effects of cytotoxic drugs55. Antibodies that recognize epitopes that are more highly expressed in senescent cells compared to non-senescent cells, coupled to a cytolytic agent, would be helpful to eliminate senescent cells56.

Senescent cells are thought to contribute to tissue dysfunction largely through chronic inflammation, and several anti-inflammatory drugs have been explored as effective modulators of SASP. Targeting SASP in senescent cells may be a strategy for cancer treatment as well. For example, glucocorticoids, a group of steroid hormones, down-regulated the secretion inflammatory components of SASP through inhibiting the transcriptional activity of NF-κB57. Metformin, a commercially anti-diabetic drug, has been reported to prevent the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and effectively suppress the induction of SASP57. Due to the complicated role of senescence in tumors and its microenvironment, not only the genetic and cellular contexts of senescent cells but also the communication between senescent cells and their microenvironments should be taken into consideration when exploiting senescence in cancer therapy.

Concluding remarks

OIS is a complex process that may play opposite roles in tumor initiation and development depending on temporal, spatial and genetic contexts. Targeting senescent cells may be beneficial for cancer therapy in certain circumstances. Though the understanding of senescence has been greatly advanced in recent years, various senescent responses make it difficult to establish uniform diagnostic criteria for cellular senescence. Currently, a combination of several features of cellular senescence is utilized to detect senescent cells. Further studies are warranted to reveal the essential mechanisms underlying OIS. Given the complexity of OIS, the diversity in the pathological function of senescent cells as well as the dynamic interplay between senescent cells and the microenvironment should be further explored when targeting senescence as a therapeutic option for cancer. In addition, the senescent phenotype of cancer cells may offer potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Taken together, great efforts must be made to elucidate the more detailed mechanisms underlying OIS, the interplay between senescent cells and the microenvironment and the roles of OIS in cancer development and therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773760).

Contributor Information

Jian Ding, Email: jding@simm.ac.cn.

Ling-hua Meng, Email: lhmeng@simm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Saretzki G. Cellular senescence in the development and treatment of cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:79–100. doi: 10.2174/138161210789941874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:51–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkisian CJ, Keister BA, Stairs DB, Boxer RB, Moody SE, Chodosh LA. Dose-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in vivo and its evasion during mammary tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:493–505. doi: 10.1038/ncb1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtois-Cox S, Jones SL, Cichowski K. Many roads lead to oncogene-induced senescence. Oncogene. 2008;27:2801–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerra C, Mijimolle N, Dhawahir A, Dubus P, Barradas M, Serrano M, et al. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:111–20. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, Georgilis A, Janich P, Morton JP, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:978–90. doi: 10.1038/ncb2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rufini A, Tucci P, Celardo I, Melino G. Senescence and aging: the critical roles of p53. Oncogene. 2013;32:5129–43. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rayess H, Wang MB, Srivatsan ES. Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1715–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu YX, Li N, Xiang R, Sun PQ. Emerging roles of the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in oncogene-induced senescence. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun PQ, Yoshizuka N, New L, Moser BA, Li YL, Liao R, et al. PRAK is essential for ras-induced senescence and tumor suppression. Cell. 2007;128:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christoffersen NR, Shalgi R, Frankel LB, Leucci E, Lees M, Klausen M, et al. p53-independent upregulation of miR-34a during oncogene-induced senescence represses MYC. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:236–45. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritschka B, Storer M, Mas A, Heinzmann F, Ortells MC, Morton JP, et al. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype induces cellular plasticity and tissue regeneration. Genes Dev. 2017;31:172–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.290635.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuilman T, Peeper DS. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terzi MY, Izmirli M, Gogebakan B. The cell fate: senescence or quiescence. Mol Biol Rep. 2016;43:1213–20. doi: 10.1007/s11033-016-4065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao SG, Jackson JG. SASP: Tumor suppressor or promoter? Yes! Trends Cancer. 2016;2:676–87. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz-Espin D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:482–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coppe JP, Kauser K, Campisi J, Beausejour CM. Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29568–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparmann A, Bar-Sagi D. Ras-induced interleukin-8 expression plays a critical role in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:447–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badache A, Hynes NE. Interleukin 6 inhibits proliferation and, in cooperation with an epidermal growth factor receptor autocrine loop, increases migration of T47D breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:383–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesina M, Wormann SM, Morton J, Diakopoulos KN, Korneeva O, Wimmer M, et al. RelA regulates CXCL1/CXCR2-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in murine Kras-driven pancreatic carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2919–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI86477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazolli E, Alspach E, Milczarek A, Prior J, Piwnica-Worms D, Stewart SA. Chromatin remodeling underlies the senescence-associated secretory phenotype of tumor stromal fibroblasts that supports cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2251–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, Campisi J, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:966–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI64098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brookes S, Rowe J, Ruas M, Llanos S, Clark PA, Lomax M, et al. INK4a-deficient human diploid fibroblasts are resistant to RAS-induced senescence. EMBO J. 2002;21:2936–45. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roninson IB. Oncogenic functions of tumour suppressor p21 (Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1): association with cell senescence and tumour-promoting activities of stromal fibroblasts. Cancer Lett. 2002;179:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00847-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin AW, Barradas M, Stone JC, van Aelst L, Serrano M, Lowe SW. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3008–19. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced cell senescence - Halting on the road to cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1037–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bieging KT, Mello SS, Attardi LD. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:359–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chicas A, Wang XW, Zhang CL, McCurrach M, Zhao Z, Mert O, et al. Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:376–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Micco R, Fumagalli M, Cicalese A, Piccinin S, Gasparini P, Luise C, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature. 2006;444:638–42. doi: 10.1038/nature05327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JJ, Lee SB, Yi SY, Han SA, Kim SH, Lee JM, et al. WSB1 overcomes oncogene-induced senescence by targeting ATM for degradation. Cell Res. 2017;27:274–93. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartkova J, Rezaei N, Liontos M, Karakaidos P, Kletsas D, Issaeva N, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444:633–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang C, Xu QK, Martin TD, Li MZ, Demaria M, Aron L, et al. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science. 2015;349:aaa5612. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young ARJ, Narita M, Ferreira M, Kirschner K, Sadaie M, Darot JFJ, et al. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev. 2009;23:798–803. doi: 10.1101/gad.519709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoare M, Young ARJ, Narita M. Autophagy in cancer: Having your cake and eating it. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Mancera PA, Young ARJ, Narita M. Inside and out: the activities of senescence in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:547–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, Mahalingam M, Green MR. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell. 2008;132:363–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LCW, Douma S, van Doom R, Desmet CJ, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acosta JC, O'Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133:1006–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tasdemir N, Banito A, Roe JS, Alonso-Curbelo D, Camiolo M, Tschaharganeh DF, et al. BRD4 connects enhancer remodeling to senescence immune surveillance. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:612–29. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laberge RM, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, Patil CK, Freund A, Zhou L, et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1049–61. doi: 10.1038/ncb3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hubackova S, Krejcikova K, Bartek J, Hodny Z. IL1- and TGFbeta-Nox4 signaling, oxidative stress and DNA damage response are shared features of replicative, oncogene-induced, and drug-induced paracrine 'bystander senescence'. Aging. 2012;4:932–51. doi: 10.18632/aging.100520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang TW, Yevsa T, Woller N, Hoenicke L, Wuestefeld T, Dauch D, et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature. 2011;479:547–51. doi: 10.1038/nature10599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iannello A, Thompson TW, Ardolino M, Lowe SW, Raulet DH. p53-dependent chemokine production by senescent tumor cells supports NKG2D-dependent tumor elimination by natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2057–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tonnessen-Murray CA, Lozano G, Jackson JG. The regulation of cellular functions by the p53 protein: cellular senescence. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017; 7. pii: a026112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malaquin N, Vercamer C, Bouali F, Martien S, Deruy E, Wernert N, et al. Senescent fibroblasts enhance early skin carcinogenic events via a paracrine MMP-PAR-1 axis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allavena P, Sica A, Solinas G, Porta C, Mantovani A. The inflammatory micro-environment in tumor progression: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eggert T, Wolter K, Ji J, Ma C, Yevsa T, Klotz S, et al. Distinct functions of senescence-associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:533–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Garon EB, Ribeiro de Oliveira M, Bonomi PD, Camidge DR, et al. Phase II study of single-agent navitoclax (ABT-263) and biomarker correlates in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3163–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yosef R, Pilpel N, Tokarsky-Amiel R, Biran A, Ovadya Y, Cohen S, et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11190. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, Donato N, Nicoll J, Paquette R, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, et al. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell. 2015;14:644–58. doi: 10.1111/acel.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Junutula JR, Raab H, Clark S, Bhakta S, Leipold DD, Weir S, et al. Site-specific conjugation of a cytotoxic drug to an antibody improves the therapeutic index. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:925–32. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim KM, Noh JH, Bodogai M, Martindale JL, Yang X, Indig FE, et al. Identification of senescent cell surface targetable protein DPP4. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1529–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.302570.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soto-Gamez A, Demaria M. Therapeutic interventions for aging: the case of cellular senescence. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:786–795. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watanabe S, Kawamoto S, Ohtani N, Hara E. Impact of senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its potential as a therapeutic target for senescence-associated diseases. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:563–9. doi: 10.1111/cas.13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]