Abstract

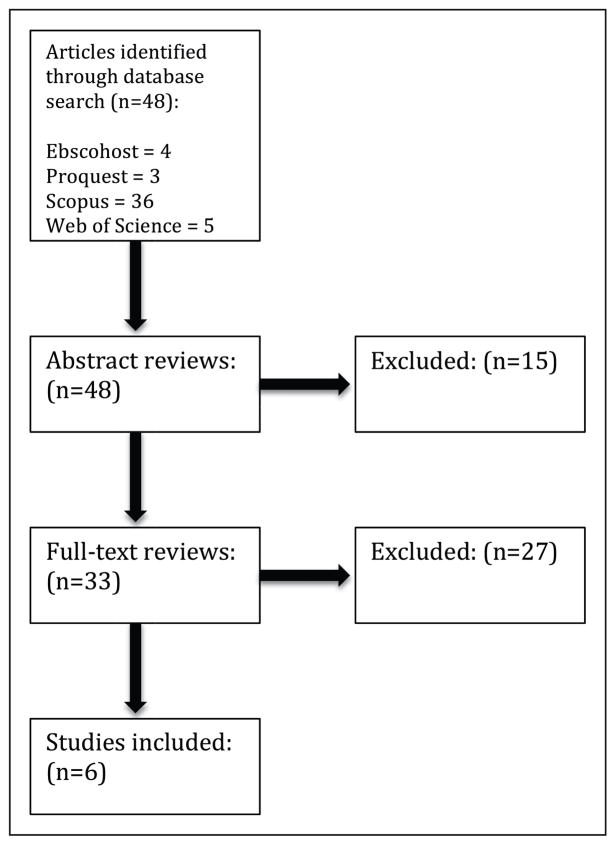

We reviewed the controlled studies that report outcome findings for Black adolescent males 24 years of age and younger at risk of suicide. Our review identified 48 articles published from 2000 to 2015, 33 that met our initial criteria for full-text articles review, resulting in 6 that met all inclusion criteria. We sought to understand what works for Black males experiencing suicide ideation or engaging in suicidal behaviors (e.g., attempts). We identified crossover effects for multisystemic therapy for reducing the risk for suicide ideation and attempts. Attachment-based family therapy was salient for use as a component of clinical practice for Black males being treated for suicide ideation. While remaining randomized control trials did involve Black youth, dis-aggregated data based on ethnicity and gender were not reported. Overall, the located studies are too few to provide unequivocal guidance for practice.

Keywords: suicide, treatment, Black males, adolescents

Although suicide has been viewed as a problem that affects more Whites, the prevalence of suicide among Black Americans has risen significantly since the mid-1980s (Griffith & Bell, 1989), with increases in both the rate of suicide completion (Garlow, Purselle, & Heninger, 2005) and that of nonfatal suicidal behavior, especially among younger Black males (Joe & Marcus, 2003). The epidemiological data are unequivocal that Black American males across all age groups die by suicide at rates ranging from 4 to 6 times higher than Black females (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1998, 2016; Joe, Baser, Neighbors, Caldwell, & Jackson, 2009). In 2014, males accounted for 80% of all Black Americans who died by suicide (CDC, 2016). Black Americans suicide risk across the life span is higher for persons under the age of 35 (Garlow et al., 2005). Today, suicide remains the third leading cause of death for young Black males. Current research on the suicide rates for children under age 12 reveals a markedly higher and statistically significant 86% increase in suicide among Black children, principally males, in contrast to Whites and Latinos (Bridge et al., 2015). Suicide among Black Americans is predominantly a young male phenomenon.

Suicide occurs in the context of a wide range of complex and interrelated underlying etiological factors. The growing body of research on Black suicidal behavior has confirmed that many of the known suicide risk factors for whites are also important risk factors for Blacks, including mental disorders such as depression (Horwath, Johnson, & Hornig, 1993; Kaslow & Kingree, 2002; Willis, Coombs, Drentea, & Cockerham, 2003) and substance abuse (Castle, Duberstein, Meldrum, Conner, & Conwell, 2004; Garlow, 2002). The most recent information on suicidal behavior among Black Americans and current research on gender differences in both risk and protective factors refute the conventional belief that suicide is rare in this population. To save the lives of more young Black men, we must invest in key protective factors including social and emotional supports and the reduction of stigma related to mental illness and help seeking (Greening & Stoppelbein, 2002; Marion & Range, 2003). Although there have been considerable advances in empirical research on suicidal behavior among Black males, particularly among youth, it is not clear whether there have been coinciding developments in the treatment or prevention literature for suicidal behavior for this population.

The Purpose of the Present Study

This article examines the current state of the science on treatment or prevention interventions for Black adolescent males at risk for suicide. Specifically, we conducted a review of the randomized control trial (RCT) and general treatment literature for Black males at risk of or engaged in suicidal behavior. The review pays significant attention to the social work profession’s contribution to science in this area, particularly since social workers are the largest occupational group of mental health professionals in the United States (Manderscheid et al., 2004) and have a significant role to play in the national strategy to reduce or prevent suicide.

Method

We searched EbscoHost, ProQuest, SCOPUS, and Web of Science for the following terms searching under the filters of abstract OR subject OR title within EbscoHost, ProQuest, and SCOPUS. These four databases were searched because they include additional primary databases. MEDLINE including PubMed, PsycINFO, and Social Work Abstracts are included within the EbscoHost database. Sociological Abstracts is included within ProQuest. The filter “Topic” encompasses abstract OR subject OR title for the Web of Science database. An additional filter was the time frame of 2000–2015. We segmented the search into four larger search topics: Black, Male, RCT, Mental Health, and Suicide. Each search topic was compiled to be as comprehensive as possible with the aforementioned terms.

Under each of these larger research topics, the following were searched using these specific search terms as our inclusion criteria:

The Black terms were searched as: “Black” OR “Blacks” OR “African American*” OR “African-American*.”

In searching for male terms, we extended the terms to include an array of males that could be involved in the life of an adolescent male or names that an adolescent themselves could be called to ensure a more expansive search. The comprehensiveness of this male search required five separate searches that were combined via OR, due to the large numbers of results that the male terms would yield. Therefore, the searches were: (1) “boy” OR “boys” OR “brother” OR “brothers” OR “dad” OR “dads” OR, (2) “father” OR “fathers” OR grandfather* OR “husband” OR “husbands” OR “male” OR “males” OR, (3) “man” OR “men” OR “son” OR “sons” OR “stepdad*” OR “step-dad” OR “step-dads” OR, (4) “stepfather*” OR “step-father” OR “stepfathers” OR “uncle” OR “uncles” OR, and (5) “stepbrother” OR “stepbrother*” OR “step-brothers” OR “step-son” OR “step-sons” OR “stepson*.” After each of these five searches, each were connected via the OR option creating a single male search term.

Additionally, “suicid*” was the search term used within the suicide search.

Similar to the male search terms, the RCT terms were searched 3 times as to not overload the system and were separated to encompass the varied terms used for RCT and later connected via an OR search. The first and second RCT term searches were separately searched as: (1) “randomi* control* trial*” OR “randomi* clinical trial*” OR “randomi* trial*” and (2) “rct.” The third RCT searches had to be individualized to the respective databases. Within EbscoHost, the RCT term was “randomi* W10 trial*.” Within Proquest, the RCT term was “ randomi* PRE/10 trial*.” Within Scopus, the RCT term was “randomi* PRE/10 trial*.” Within Web of Science, the RCT term was “randomi* NEAR/10 trial*.” Accordingly, these three separate terms for RCT were combined via the OR option creating a single RCT search term.

The mental illness terms were searched as: “mental*” OR “psycholog*” OR “psychiatr*” OR “mood*” OR “behavior*” OR “distress”

Upon creating these four larger search terms, the results were combined using the AND option: Black terms AND RCT terms AND male terms AND mental health terms AND suicide term. Only English-language publications and articles from scientific journals were included in our search results.

The search results were also limited to those studies with sample populations between the ages of 12 and 29 years old. Within the ProQuest database, there were not specific age limiters available for this inclusion criterion. Therefore, all abstracts were examined for age information in order to limit the results that were used in the final analysis. Articles with abstracts that definitively indicated the desired age ranges were designated for full review as well as articles with abstracts that did not indicate specific age information. Articles with abstracts indicated age ranges outside of 12–29 were discarded. Two independent reviewed the remaining articles to ensure inclusion criteria were met.

Result

Information Retrieval

Our search located 48 articles published from 2000 to 2015 that met our initial criteria (see Figure 1). Two independent reviewers selected the inclusion of 30 of these articles for full review, while 8 were mediated by the lead author when there was disagreement between the original reviewers. The lead author determined that three of the eight articles should be included in the full review. Altogether, we agreed upon 23 of 33 articles for full review after specifying for suicidality outcomes. From these 23 articles, we ended up with six that met all inclusion criteria (see Table 1). We read the six articles again to note specific treatment, effect length of treatment, and outcome measures. All of the studies included were RCTs. Our content analysis was organized by suicidality outcomes including (1) suicide prevention, (2) suicidal behavior reduction, (3) suicidal ideation reduction, and (4) none.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of suicidality studies: Exclusion and inclusion.

Table 1.

Suicide Systematic Review Article Overview.

| Author | Intervention | Demographics | Outcomes | Did It Work? | Did It Work for Black Males? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diamond et al. (2010) | Attachment-based family therapy (ABFT) | 12- to 17-year-old adolescents M: 16.7% (11/66) B: 89.1% (55/66) BM: Unknown |

Suicidal ideation reduction | Yes; 24-week effect of 70% ABFT participants versus 34.6% enhanced usual care participants with reported ideation in normative range. Ideation reduces for up to 6 months | Unknown; results are not reported for Black males, specifically |

| Diamond et al. (2002) | ABFT | 13- to 17-year-old adolescents M: 22% (7/32) B: 69% (22/32) BM: Unknown |

Suicidal ideation reduction | Yes; 13.2% suicidal ideation reduction from ABFT-treated participants versus 1.7% suicidal ideation reduction for enhanced usual care treated participants | Unknown; results are not reported for Black Males, specifically |

| Gibbons et al. (2006) | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) | 5- to 14-year-old children and adolescents M: 74.9% (699/933) B: 11.5% (107/933) BM: 8.5% (79/933) |

Suicidal behavioral reduction | Yes; 81% of the children and adolescents that committed suicide did not have SSRI in their systems | Yes; SSRI is correlated with reduced suicide behavior in Black Males |

| Huey et al. (2004) | Multisystemic therapy (MST) | 10- to 15-year-old M: 65% (101/156) B: 65% (101/156) BM: Unknown |

Suicidal behavioral reduction | Yes; MST participants reported a 27% reduction in attempted suicide on Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) from pretreatment to 1-year follow-up; a 37% reduction in Child Behavior Checklist. Suicidal Ideation reduction from MST participants reduced by 41% from pretreatment to 1-year follow-up on Brief Symptom Inventory scale; a 18% reduction in suicidal ideation on the YRBS | Unknown; results are not reported for Black males, specifically |

| Kellam et al. (2014) | Good behavior game | 19- to 21-year-olds M: (Unknown/1,196) B: (Unknown/1,196) BM: (Unknown/1,196) |

Suicidal behavioral reduction and suicidal ideation reduction | Unknown; suicidal ideation noted as impacted both males and females | Unknown; results are not reported for Black males, specifically |

| Perry et al. (2014) | HeadStrong program | 13- to 16-year-old adolescents M: (Unknown/380) B: 5% (16/380) Aboriginal BM: (Unknown/380) |

Suicidal ideation reduction | No. HeadStrong did not significantly impact suicidal ideation | Unknown; results are not reported for Black/Aboriginal males, specifically. No differences were found between groups on suicidal ideation |

Note. Totals from the grid include interventions and control groups. M = total males; B = total Black; BM = total Black males.

Risk of Bias

There were two primary reviewers and a third reviewer who helped make study decisions when there was disagreement among the primary reviewers. The interrater reliability of the two primary reviewers from this initial round of review was .79.

Effects on Suicide

Over the last 15 years, despite having few studies of the prevention of suicidal behavior that included some representation of Black males in RCTs, there are few studies showing effects for suicidal ideation and behavior. Our review did not find any studies that examined the effect of a treatment on suicide, except for a county-level correlation study of the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as citalopram, paroxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and sertraline on children and adolescents suicide rates (Gibbons, Hur, Bhaumik, & Mann, 2006). County-level rates of SSRI use were shown to be associated with lower rates of adolescent suicides. This effect was found consistently among populations aged 5–14 years old, across gender and ethnicity (Gibbons et al., 2006). Without these SSRI prescriptions, the suicide rates would have increased by 81% with over 250 additional suicides per year. Blacks had a suicide rate marginally lower than all other ethnic groups in this sample. Black males have a lower suicide rate than other males and are 3 times more likely to higher suicide rates than Black females (Gibbons et al., 2006).

Suicide Attempts

When it comes to suicidal behavior, one potentially effective treatment was identified in our review. Multisystemic therapy (MST) was compared to hospitalization (Huey et al., 2004). This study examined youth ages 10–17 (n = 156), hospitalized in the emergency psychiatric unit of a medical center due to, in part, suicide attempts as measured by the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The study sample was 65% male and 65% African American. MST reduced the number of youth suicide attempts after treatment by 17% and after follow-up at 1 year by 27% from pretreatment compared to the control group. Using the CBCL to measure outcomes, MST reduced the number of youth suicide attempts after treatment by 24% and after follow-up at 1 year by 37% from pretreatment compared to the control group.

Suicide Ideation

Regarding suicidal ideation, three potentially effective treatments were identified in our review: The HeadStrong program, MST, and attachment-based family therapy (ABFT). MST reduced suicidal ideation after treatment by 25% and after follow-up at 1 year by 41% from pretreatment compared to the control group (Huey et al., 2004). Using the YRBS measure, MST reduced suicidal ideation after treatment by 12% and after follow-up at 1 year by 22% from pretreatment compared to the control group. As noted above, the study sample was 65% male and 65% African American.

Two studies on ABFT were compared to enhanced usual care (EUC) that was defined as facilitated referral to other providers (Diamond et al., 2010; Diamond, Reis, Diamond, Siqueland, & Isaacs, 2002). The samples, ranging in size from n = 32 to n = 341, was composed of youth aged 12–17, 22% male, and about 69% Black. ABFT was found to reduce suicidal ideation more effectively than EUC measured by a score of 31 on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire and more than a score of 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory. ABFT-treated adolescents achieved a reduction in suicidal ideation after treatment that was 34.3% better than EUC and at follow-up that was 35.4% better than EUC. Although ABFT was 4 times more effective in suicidal ideation reduction, there was no evidence to suggest that it can prevent suicidal behavior.

The HeadStrong program is a school-based education program administered to 9th and 10th-grade students, aged 13–16, from five Catholic and five independent schools in Australia to examine the effect on mental health literacy, psychological distress, and suicide ideation. This program had no significant effect on suicidal ideation measured by six adapted items from a 3-point scale assessment found in the Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (Perry, Petrie, Buckley, & Christensen, 2014). Five percent of the sample of 13- to 16-year-old males and females identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, two groups included in the ethnic diaspora for those of African descent.

The review identified the good behavior game (GBG), a universal classroom based preventative intervention that was administered to low- to middle-income children (Kellam et al., 2014). However, the crossover effects for suicide ideation, specifically we found no ethnic description for whom and when this reduction occurs within this specific article. Although 75% of the sample participants were Black and 50% were males, the effect of the GBG on suicide ideation reduction and suicide attempts was only clearly described for non-Hispanic Whites.

Discussion

Suicide is a growing problem among Black Americans and young Black males account for most of those death. Despite suicide being the third leading cause of death among young Black adolescents, this review covered research produced since 2000 revealed a dearth of research in this area, a general lack of scientific investment of RCT intervention for this population, and a failure of documentation of the effect of any interventions over time. Social work-led science on the treatment or prevention of suicidal behavior could not be found. Social workers were not among the researchers in these articles and only two of the articles noted that social workers helped implement the study. Given that social workers deliver the majority of mental health services in the United States (Manderscheid et al., 2004), this is a major opportunity in the field for us to advance science on the treatment and prevention of suicidal behavior. With limited research on this topic, the lack of social work-led research is problematic.

Overall, the empirical treatment literature on suicidal behavior is woefully underdeveloped, thus not sufficient for guiding comprehensive practice protocols regarding what works when treating young Black males at risk for suicide. However, our review identified crossover effects for MT for reducing the risk for suicide ideation and attempts, which are well-known risk factor eventually dying by suicide (Beautrais, 2003). ABFT is salient for use as a component of clinical practice for Black males being treated for suicide ideation. It is not clear if there will be long-term treatment benefits, because this information was not given in these articles. So, even with some effective treatments for suicidality, the duration of the treatment benefit is estimated to last at best 1 year according to the studies we found for MST and ABFT. Advancing research about the lengths of time for which a treatment or interventions is effective can help practitioners maintain a positive impact on suicidality and would ensure beneficial evidence-based practice treating suicidal Black males.

There are notable limitations to the science of treating suicidal Black males such as the inconsistencies in how suicidal behavior was measured across the studies. A more robust review may be possible if there were consistency across studies in the measures used to assess suicidal behavior and ideation. Another point of consideration is the sample of future studies should be large enough to ensure that subgroup analysis of effect size by gender and ethnicity is feasible. Effectiveness in each individual treatment category (adolescent-centered behavior treatment, adolescent-centered pharmacological/behavior treatment, family-centered behavior treatment, quality of depression treatment in primary care, home environment treatment) cannot be drawn upon since all but one trial presented aggregated data without ethnicity and gender specifications.

Future research must test the efficacy of social workers’ skills development for working with potentially suicidal Black adolescents, to intervene in crisis situations and make appropriate referrals, to encourage patients follow-up with referrals or adherence to treatment, and enhance client’s willingness to engage in clinical treatment. Finally, there was not a single research study that focused specifically on Black males. Therefore, it is difficult to speak with confidence on the treatment effects on Black male adolescents. Research designed specifically to examine treatments in clinical and nonclinical setting ameliorate the symptoms or signs of suicidal behaviors among Black male adolescents specifically would enhance social work practice.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

- Mr. Banks’ involvement in this project was supported by Grant Number T32MH019960 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- Beautrais AL. Life course factors associated with suicidal behavior in young people. American Behavioral Scientist. 2003;46:1137–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Asti L, Horowitz LM, Greenhouse JB, Fontanella CA, Sheftall AH, … Campo JV. Suicide trends among elementary school–aged children in the United States: From 1993 to 2012. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics. 2015;169:673–677. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle K, Duberstein PR, Meldrum S, Conner KR, Conwell Y. Risk factors for suicide in blacks and whites: An analysis of data from the 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:452–458. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal Injury Reports, National and Regional, 1999–2014. 2016 Retrieved June 27, 2016, from http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide among black youths—United States, 1980–1995. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Reis BF, Diamond GM, Siqueland L, Isaacs L. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: A treatment development study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1190–1196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:122–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow SJ. Age, gender, and ethnicity differences in patterns of cocaine and ethanol use preceding suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:615–619. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow SJ, Purselle D, Heninger M. Ethnic differences in patterns of suicide across the life cycle. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:319–323. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ. The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1898–1904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening L, Stoppelbein L. Religiosity, attributional style, and social support as psychosocial buffers for African American and white adolescents’ perceived risk for suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2002;32:404–417. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.4.404.22333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith E, Bell CC. Recent trends in suicide and homicide among blacks. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:2265–2269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwath E, Johnson J, Hornig CD. Epidemiology of panic disorder in african americans. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:465–469. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins C, Cunningham PB, Edwards J, … Pickrel SG. Multisystemic therapy effects on attempted suicide by youths presenting psychiatric emergencies. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:183–190. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RS, Neighbors HW, Caldwell CH, Jackson JS. 12-Month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among black adolescents in the National Survey of American Life. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:271–282. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Marcus SC. Trends by race and gender in suicide attempts among U.S. adolescents, 1991–2001. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Kingree JB. Risk factors for suicide attempts among African American women experiencing recent intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:283–295. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.3.283.33658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Wang W, Mackenzie ACL, Brown CH, … Windham A. The impact of the good behavior game, a universal classroom-based preventive intervention in first and second grades, on high-risk sexual behaviors and drug abuse and dependence disorders into young adulthood. Prevention Science. 2014;15:6–18. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manderscheid RW, Atay JE, Male A, Blacklow B, Forest C, Ingram L, … Ndikumwami J. Highlights of organized mental health services in 2000 and major national and state trends. In: Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ, editors. Mental health United States, 2002. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. pp. 243–279. (DHHS Pub No. [SMA] 3938) [Google Scholar]

- Marion MS, Range LM. African American college women’s suicide buffers. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:33–43. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.1.33.22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry Y, Petrie K, Buckley H, Christensen H. Effects of a classroom-based educational resource on adolescent mental health literacy: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence. 2014;37:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis LA, Coombs DW, Drentea P, Cockerham WC. Uncovering the mystery: Factors of African American suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:412–429. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.4.412.25230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]