Abstract

Ultrasound and hyperpolarized magnetic resonance imaging enable the visualization of biological processes in deep tissues. However, few molecular contrast agents are available to connect these modalities to specific aspects of biological function. We recently discovered that a unique class of gas-filled protein nanostructures known as gas vesicles could serve as nanoscale molecular reporters for these modalities. However, the need to produce these nanostructures via expression in specialized cultures of cyanobacteria or haloarchaea limits their broader adoption by other laboratories and hinders genetic engineering of their properties. Here, we describe recombinant expression and purification of Bacillus megaterium gas vesicles using a common laboratory strain of Escherichia coli, and characterize the physical, acoustic and magnetic resonance properties of these nanostructures. Recombinantly expressed gas vesicles produce ultrasound and hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI contrast at sub-nanomolar concentrations, thus validating a simple platform for their production and engineering.

Introduction

Optical reporters such as organic dyes and fluorescent and luminescent proteins have enabled many biological discoveries. However, the poor penetration of light into tissue limits the use of these reporters in intact animal models and human patients1. In contrast, non-invasive imaging techniques such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are capable of visualizing deep tissues, but have fewer molecular reporters to connect them to specific biological phenomena2. Ultrasound is among the most widely used biomedical imaging modalities, offering high spatial and temporal resolution (~100 μm and sub-millisecond) while penetrating deep into the organism3. Ultrasound contrast is produced by sound wave scattering at interfaces between materials with different density or stiffness. Likewise, MRI is capable of whole-body imaging with spatial resolution on the order of 100 μm, and uses a variety of contrast mechanisms arising from nuclear spin behavior4. Among these mechanisms, hyperpolarized MRI provides particularly high molecular sensitivity by using nuclei, such as 129Xe, prepared with non-equilibrium polarization several orders of magnitude higher than that available under equilibrium conditions5. Hyperpolarized 129Xe can be administered through inhalation or injection for in vivo imaging.

Hyperpolarized MRI and ultrasound have few molecular reporters for biological imaging. Conventional ultrasound contrast agents comprise microbubbles, which are limited by their micron scale and physical instability to imaging primarily intravascular targets6,7. Nanoscale synthetic reporters for this modality are in development8–10, but have not reached widespread use. Meanwhile, common contrast agents for hyperpolarized 129Xe-MRI comprise organic cage compounds which reversibly bind xenon and produce contrast through hyperpolarized chemical exchange saturation transfer (HyperCEST)11–14. Most such molecules, while detectible, have relatively low solubility in water and can be difficult to deliver to tissues.

To address these limitations, we recently introduced a unique class of air-filled protein nanostructures called gas vesicles (GVs) as genetically encodable reporters for ultrasound and hyperpolarized MRI15–20. GVs are naturally expressed in aqueous photosynthetic bacteria and archaea as a means to achieve buoyancy21,22. GVs have dimensions on the order of 100 nm, comprising a 2-nm-thick protein shell that allows gas to freely diffuse in and out of their hollow interior while preventing water from condensing into a liquid in their core (Figure 1a). The contents of GVs reflect the gases dissolved in surrounding liquid media. The GV shell is primarily formed from gas vesicle protein A or B (gvpA/B), and in some species is supported by an external scaffolding protein known as gas vesicle protein C (gvpC). In addition, 7-11 assembly factor genes are required for GV formation.

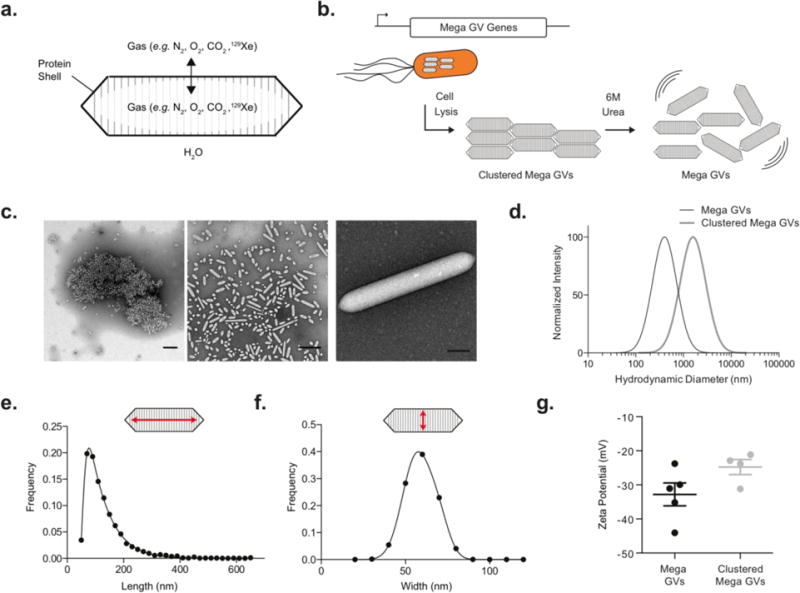

Figure 1. Recombinantly expressed Mega GVs.

(a) Schematic of Mega gas vesicles, hollow protein nanostructures that allow gas to diffuse through the protein shell but keep water from condensing in the core. (b) Mega GVs are heterologously expressed in E. coli, purified and declustered for characterization as ultrasound and hyperpolarized MRI contrast agents. (c) Transmission electron micrograph of purified recombinant GVs, (left) Mega GVs form micron sized clusters upon cell lysis, which can be declustered using 6 M urea (center). (Representative image of mature Mega GV recombinantly expressed in E. coli (right). Scale bars are 500 nm for left and center images, and 100 nm for right image.) (d) Hydrodynamic diameter of clustered Mega GVs are 1.7 μm and upon declustering, Mega GVs are 164 nm. (N=4 independent preparations for clustered Mega GVs and N=5 independent preparations for Mega GVs.) (e-f) Histogram of length and width of Mega GVs using TEM analysis. (Measurements represent 3487 particles from N=4 independent biological preparations.) (g) Zeta potential measurements of Mega GVs and clustered Mega GVs. (N = 4, error bars are ± SEM).

We recently demonstrated that GVs purified from native host cells such as Anabaena flos-aquae (Ana) and Halobacterium NRC-1 (Halo) can be used as biomolecular reporters for both ultrasound and hyperpolarized 129Xe-MRI15,16,19. The former capability arises from the ability of GVs to scatter sound waves via non-linear interactions with the acoustic field18,20. The latter contrast arises from the ability of GVs to act as hosts for hyperpolarized 129Xe, allowing their detection using HyperCEST pulse sequences. Building on these initial discoveries, we have developed methods to engineer the scaffolding protein of Ana GVs to modify their acoustic and targeting properties17, and devised optimized pulse sequences for improved ultrasound contrast20. GVs produce ultrasound contrast when injected in circulation or in the gastrointestinal tract of the mammalian host15,17,20,23. However, this work has utilized GVs expressed in their native hosts, which require special culture conditions not available in all laboratories, and are more cumbersome to engineer genetically than conventional laboratory bacterial species. To overcome these limitations, we set out to establish a system for producing GVs in a common laboratory strain of E. coli and characterize their essential properties as nanoscale reporters for ultrasound and hyperpolarized 129Xe-MRI.

Materials and Methods

Mega Gas Vesicle Expression and Purification

The pST39 plasmid containing the pNL29 GV gene cluster from Bacillus megaterium (Addgene ID 91696) was transformed into Rosetta 2(DE3)pLysS chemically competent E. coli (EMD Millipore, Temecula, CA) using a heat shock protocol. In this construct, expression of the GV operon is driven via a T7 promoter, acted on by a T7 RNA polymerase integrated into this E. coli strain and controlled by isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Freshly transformed cells were cultured in Luria Broth (LB) supplemented with 1% glucose, 100 μg/mL ampicillin, and 25 μg/mL chloramphenicol at 37°C and 250 rpm shaking overnight. At confluency, 0.5 or 2.5 mL of starter culture was inoculated into 50 or 250 mL LB (respectively) supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 100 μg/mL ampicillin, and 25 μg/mL chloramphenicol at 37°C and 250 rpm shaking until OD600 reached 0.4 to 0.6. Gas vesicle expression was then induced with 20 μM IPTG and the culture continued to grow at 30°C and 250 rpm shaking for 22 hours. The cultures were then centrifugated at 600 g for 1 hour and the mid-natant between the buoyant cell fraction and pellet was removed. The whole cell population was then lysed by the addition of 10% SoluLyse-Tris reagent (Genlantis, San Diego, CA), 250 μg/ml lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 10 μg/ml DNAseI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and rotated gently for 20 minutes at room temperature. GVs then underwent four rounds of buoyancy purification, which consisted of isolating the buoyant layer via centrifugation, followed by resuspension in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Some of the purified GVs were then declustered with the addition of urea to a final concentration of 6 M and purified again in PBS via 3 rounds of buoyancy isolation. Protein concentration was measured using the Pierce 660 nm protein assay (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA) using GVs that were pre-collapsed using a bath sonicator.

Electron Microscopy

GV samples were diluted to OD500 ∼ 0.2 in 10 mM HEPES buffer and spotted on Formvar/Carbon 200 mesh grids (Ted Pella, Redding, CA), which were rendered hydrophilic by glow discharging (Emitek K100X). Unclustered Mega GVs were negatively stained using 2% uranyl acetate. Images were acquired using the Tecnai T12 LaB6 120 kV transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with a Gatan Ultrascan 2k × 2k CCD camera.

Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Potential Measurement

Hydrodynamic diameter and Zeta potential of GVs were measured with a Zeta-PALS analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, Hotsville, NY). GVs were diluted to OD500 of 0.2 in 50 μL for DLS measurements. The reported hydrodynamic diameter for each sample was taken using 5 measurements of well-mixed samples. Zeta potential measurements were taken of GVs mixed in 1.5 mL of double-distilled water at a conductance of 100 μS.

Pressurized Absorbance Spectroscopy

GV samples were diluted to OD500 of 0.5 and loaded into a flow-through, 1 cm path-length quartz cuvette (Hellma Analytics, Plainview, NY) that was connected to a N2 cylinder through a pressure controller (Alicat Scientific, Tucson, AZ). The pressure was increased stepwise in 50 kPa increments up to 1 MPa, followed by 100 kPa increments up to 1.2 MPa, and the OD500 at each step was measured using a spectrophotometer (EcoVis, OceanOptics, Winter Park, FL). The absorbance reading at 0 MPa and the lowest OD500 were used as the maximum and minimum, respectively, for normalization.

Ultrasound Imaging

Imaging phantoms were made from 1% agarose in PBS casted using a custom 3D printed inverted 96 well mold. GVs were prepared at twice the imaging concentration in PBS and mixed at 1:1 volume with 1% agarose at 65°C, then loaded in the wells of the agarose phantom. The phantom was positioned to allow imaging of the axial plane. Ultrasound images were acquired using a L22-14V 128-element linear array transducer and programmable scanner (Vantage, Verasonics, Kirkland, WA). The transducer was mounted on a computer-controlled 3D translation stage (Velmex, Bloomfield, NY). For imaging, the transducer and phantoms were submerged in PBS for acoustic coupling, and the center of the wells was placed at a 7.5 mm depth relative to the transducer face. B-mode ultrasound images for the concentration series were acquired using 0.91 MPa peak positive acoustic pressure, at 18 MHz frequency, with a f-number of 2.0. Maximal collapse was achieved with exposure to 4.2 MPa peak positive acoustic pressure. Acoustic collapse measurements were acquired at 0.46 MPa after the GVs were insonated with the indicated ultrasound pressures. Ultrasound images are displayed with square-root compression and decompressed for data analysis. Ultrasound data was analyzed using a custom MATLAB script to select the region of interest (ROI) of each image and calculate the average pixel intensity. Data represent four biological replicates for each sample (N=4), with representative images shown in the figures.

Hyperpolarized Xe Spectroscopy and Imaging

A gas mixture of 5% 129Xe (26.4% of natural abundance), 10% N2 and 85% He was hyperpolarized by spin-exchange optical pumping under continuous flow using a custom-designed polarizer (150 W line-narrowed infrared laser; full-width-at-half-maximum of 0.5 nm)24. GVs were diluted in PBS to concentrations ranging from 650 pM to 20.32 pM. Hyperpolarized Xe was bubbled through the solution at an overpressure of 50 kPa (total pressure of 150 kPa) with a flow rate of 20 mL/min. All experiments were conducted at 20°C at 9.4 Tesla. Hyperpolarized 129Xe MR images were acquired using a rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) pulse sequence modified for saturation transfer using the magnetization transfer module in ParaVision 6 (Bruker, Billerica, MA). Each GV sample was measured with hyperpolarized Xe-MRI separately, starting with the sample containing the highest GV concentration (to adjust RF cw-saturation pulse parameters to transfer saturation to 100% accordingly). All HyperCEST experiments used RF cw-saturation of 35 μT for 10 seconds. The HyperCEST effect was quantified as the fractional change in signal following on-resonance saturation compared to off-resonance saturation.

Results and Discussion

Recombinant Expression and Physical Characterization

As a starting point for recombinant GV production, we chose a GV gene cluster from Bacillus megaterium (Mega) that was previously shown to be compatible with E. coli expression in a study where the GVs were not purified to examine their properties25. We cloned this gene cluster into a high copy E. coli expression plasmid, downstream of a T7-LacO inducible promoter. A bacterial strain used for protein overexpression, Rosetta 2(DE3)pLysS, was transformed with the plasmid and induced to express Mega GVs for 22 hours. After gentle lysis, GVs could be separated from cellular debris through buoyancy purification (Figure 1b).

Immediately after purification, Mega GVs were clustered, as observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 1c). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed a mean hydrodynamic diameter of 1733 ± 113 nm (Figure 1d). Hypothesizing that the clustering is mediated by a denaturable non-covalent interaction involving proteins, we attempted to de-cluster the Mega GVs by treating them with 6 M urea, based on previous findings that urea treatment can remove surface proteins from Ana GVs without compromising their shells17,26. Urea treatment resulted in declustered GVs with an average hydrodynamic diameter of 164 ± 19 nm (Figure 1d). Quantitative analysis of TEM data revealed that Mega GVs have diameters of 59 ± 9 nm and lengths of 129 ± 70 nm (Figure 1e–f). Assuming a tapered cylindrical shape, this corresponds to a single-GV volume of 0.2 attoliter (0.054-0.48 attoliter), which is approximately 32 times smaller than for Ana and Halo GVs19. Individual Mega GVs had an average zeta potential of −32.8 ± 10 mV (Figure 1g). A zeta potential of −24.8 ± 4 mV in clustered Mega GVs indicated that positively charged molecules were associated with negatively charged GVs in the cluster. Purified Mega GVs remained declustered under all conditions examined in this study for a period of several weeks.

Based on the average dimensions and geometry of GVs observed by TEM (cylindrical with conical tips), an assumed shell thickness of 18 Å based on GvpA homology to Ana22, and a protein density of 1.4 g/ml, we calculated the average molecular weight of Mega GVs to be 71.7 MDa. This compares to average molecular weight of 320 and 282 MDa for GVs purified from native hosts Anabaena flos-aquae and Halobacterium NRC-1, respectively19. Because GVs scatter light, it is practically convenient to measure their molar concentration using their optical density at 500 nm (OD500). To establish the relationship between OD500 and concentration, the protein concentration of Mega GVs was measured using a Pierce 660-nm assay to be 145 μg/mL per OD500 after the GVs were collapsed using sonication. Using the average molecular weight, this corresponds to a molar concentration of 2.03 nM/OD500. When Mega GVs are clustered, they scatter light more strongly, with declustering leading to an average 6-fold reduction in light scattering. Thus, the concentration of clustered Mega GVs can be estimated as 338 pM/OD500. Using this relationship, from a 50 mL E. coli culture the average yield of clustered Mega GVs is 1 mL of 10 ± 2 nM solution and that of Mega GVs is 1 mL of 5.6 ± 2 nM solution.

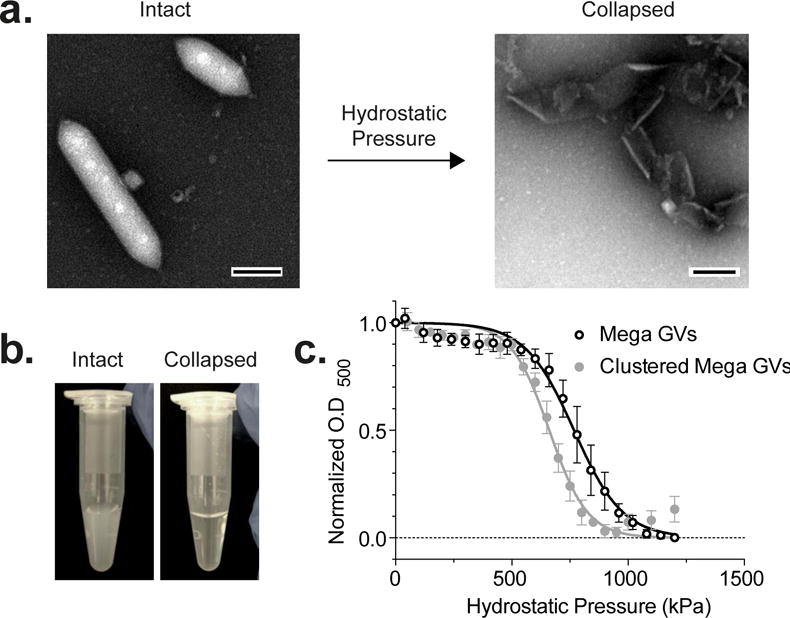

A key property of GVs useful in both ultrasound and MR imaging applications is their ability to irreversibly collapse under specific amounts of pressure (Figure 2a). This enables background-subtracted and multiplexed imaging, and provides convenient experimental controls, since collapsed GVs cease to produce contrast in ultrasound and MRI15,16. Upon collapse, GVs also lose their ability to scatter light, causing opaque GV solutions to become clear (Figure 2b). To characterize the critical collapse pressure of Mega GVs, we measured the optical scattering of GV suspensions as a function of applied hydrostatic pressure. Clustered and unclustered Mega GVs had hydrostatic collapse midpoints of 660 kPa and 767 kPa, respectively (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Hydrostatic collapse of recombinant Mega GVs.

(a) Representative TEM image of Mega GVs (left) under hydrostatic pressure beyond critical collapse causes the gas vesicle wall to unravel (right). (Scale bars are 100 nm.) (b) Intact Mega GVs scatter light when in suspension (left) and become clear upon collapse as their gaseous core dissolves in solution (right). (c) Optical density measurement of clustered Mega and Mega GVs as a function of hydrostatic pressure. Data is fit to a Boltzmann sigmoid function of the form with pc representing average midpoint of collapse and Δp representing the slope (N=4, error bars are ± SEM).

Ultrasound Contrast

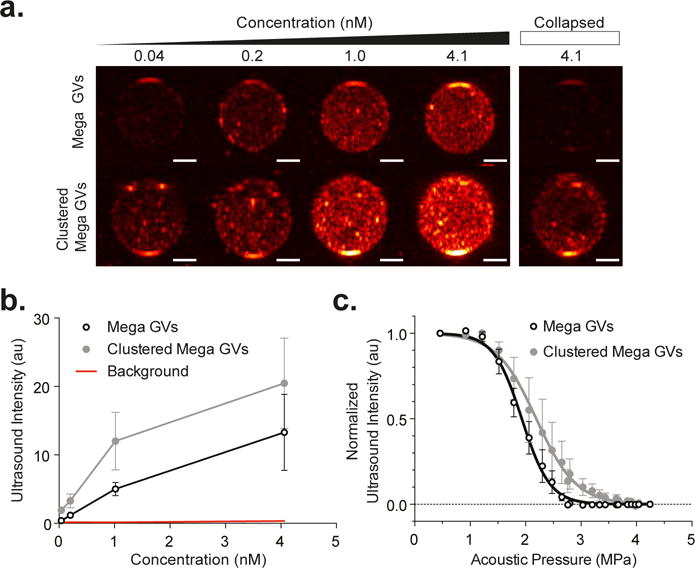

The gaseous core of GVs allows these structures to function as ultrasound contrast agents15,17,18,20. To evaluate the ability of Mega GVs to serve this function, these nanostructures were embedded in acoustically transparent agarose phantoms and imaged with ultrasound at 18 MHz, a frequency within the range commonly used for preclinical imaging. Mega GVs produced B-mode ultrasound contrast at concentrations as low as 40 pM, with stronger contrast at increasing concentrations (Figure 3a–b). Given their larger size, we expected micron-sized clusters of GVs to produce stronger ultrasound contrast than the nano-sized Mega GVs, since both of them are small enough relative to the wavelength to be in the Rayleigh scattering regime18. At equal concentrations, clustered Mega GV contrast was 54% stronger.

Figure 3. Recombinant Mega GVs as ultrasound contrast agents.

(a) B-mode ultrasound images of Mega GVs (top row) and clustered Mega GVs (bottom row) showing increased intensity as a function of concentration (40, 203, 1015, and 4060 pM GV particles) in 1% agarose phantom using a 18 MHz imaging transducer under 0.91 MPa acoustic pressure. Ultrasound images of 4060 pM Mega GVs (top right) and clustered Mega GVs (bottom right) after 4.2 MPa ultrasound insonation. (Representative images from N=4 independent preparations. Scale bars are 1 mm.) (b) Graph of average ultrasound intensities for Mega GVs and clustered Mega GVs as a function of concentration (N=4 independent preparations, error bars are ± SEM.) (c) Acoustic collapse measurements of Mega GVs and clustered Mega GVS as a function of acoustic pressure. Data is fit to a Boltzmann sigmoid function of the form with pc representing average midpoint of collapse and Δp representing the slope (N=4, error bars are SEM).

Acoustic pressures above critical collapse points allow GVs to be collapsed in situ, enabling background subtraction and multiplexing in imaging experiments15,17. These acoustic collapse mid-points can be significantly higher than their hydrostatic counterparts due to the microsecond kinetics of gas exchange through the GVs shell27: while under hydrostatic conditions, gas molecules have time to escape through the GV wall during compression, the microsecond cycles of ultrasound are too rapid, resulting in gas staying in the shell and contributing to deformation resistance under pressure18,20. To establish the critical mid-points for Mega GVs, we imaged them with ultrasound while applying increasing acoustic pressures at 18 MHz. The resulting collapse mid-points were 2.2 and 1.9 MPa for Clustered Mega and Mega GVs, respectively (Figure 3c). These pressures provide ample range for the GVs to be imaged with relatively strong acoustic excitation, while being low enough for most ultrasound transducers to be able to collapse them.

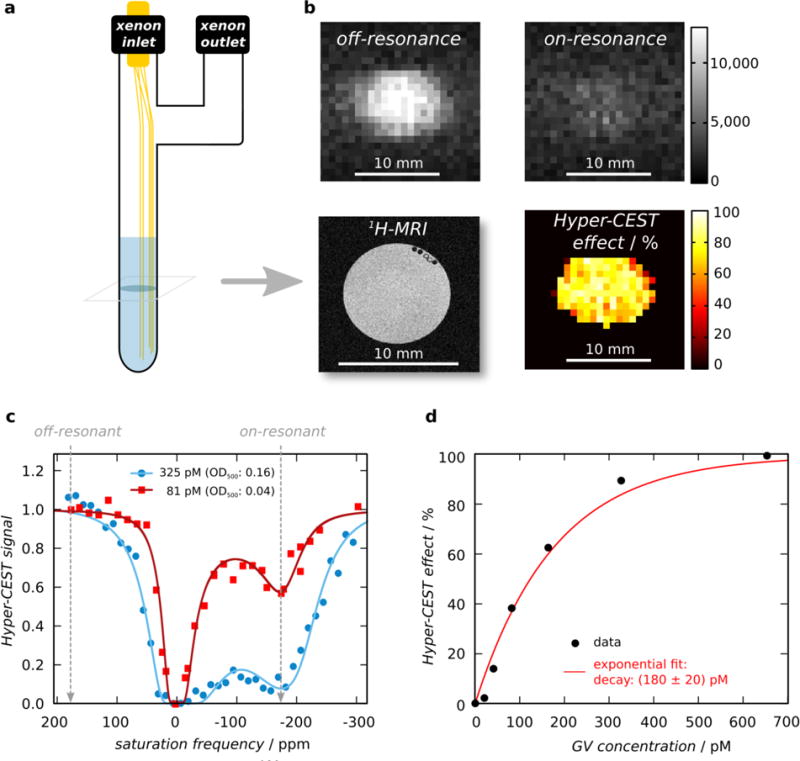

Hyperpolarized 129Xe-MRI Contrast

Dissolved xenon can partition in and out of the gaseous GV interior (Figure 1a). The distinct chemical environment of this compartment results in a specific chemical shift of the 129Xe magnetic resonance frequency, enabling sensitive imaging of GVs using 129Xe HyperCEST MRI5,16. To evaluate the MRI performance of Mega GVs, we imaged them at 9.4 Tesla in a phantom bubbled with 129Xe gas that was hyperpolarized using spin-exchange optical pumping19,24 (Figure 4a). Using the distinct chemical shift of 129Xe in the GV interior, the gas atoms can be selectively saturated with on-resonance radio frequency (RF) pulses, while exchanging with 129Xe in solution, resulting in a decrease in the overall 129Xe signal (Figure 4b). A stepwise sweep of the saturation frequency while monitoring the remaining total polarization allowed us to identify a saturation peak for the xenon in Mega GVs at −174 ppm relative to free dissolved xenon. The relatively rapid exchange rate of xenon molecules in and out of Mega GVs may be leading to a broadening of the peak saturation. 10-second saturation pulses at this frequency produced significant HyperCEST effects for Mega GVs at concentrations as low as 40.6 pM (Figure 4c). The intensity of the HyperCEST effect with respect to the GV concentration followed an exponential relationship (Figure 4d). This can be understood as the increasing GV concentration causing a linear increase in the Lorentzian-shaped depolarization rate of xenon, with the set saturation time causing an added exponential weighting28–30.

Figure 4. Hyperpolarized 129Xe-MRI of recombinant Mega GVs.

(a) Illustration of HyperCEST MRI phantom used to bubble hyperpolarized 129Xe gas in solution containing Mega GVs during MRI acquisition. (b) Representative axial images of 325 pM Mega GVs acquired with off-resonant saturation at +174 ppm (top left) or on-resonant saturation at −174 ppm (top right), and their normalized difference (bottom right). Proton-MRI depicts axial plane containing GVs in PBS (bottom left). (Scale bars are 5 mm.) (c) Representative HyperCEST z-spectra (RF cw-saturation of 35 μT for 10 s) for Mega GVs at a concentration of 325 pM (blue circles) or 81 pM (red squares) in PBS at room temperature. Each data set was fitted to an exponential-Lorentzian. (d) The percent HyperCEST effect as a function of Mega GV concentration. Data was fitted to an exponential function of the form f(c)=100(1−e−c/τ) with τ representing recovery rate and c representing concentration to facilitate visualization.

Conclusion

Recombinant expression of Mega GVs in E. coli provides a convenient platform for the simple and rapid production of gas-filled protein nanostructures for applications in molecular imaging, within which GVs offer unique advantages alongside other emerging nanoscale and protein-based reporters2,4,8,31. In future studies, this expression system could also facilitate the genetic engineering of GV properties. Compared to the more established Ana and Halo GVs, Mega GVs are 32-times smaller by volume, but nevertheless able to produce significant ultrasound and 129Xe-MRI contrast. Their nanoscale size may facilitate the use of Mega GVs as targeted contrast agents following systemic administration. At the same time, the natively clustered form of Mega GVs has greater ultrasound contrast per GV, which may be also useful in certain applications. Overall, we anticipate that the unique properties of Mega GVs, together with their convenient heterologous expression and purification, will help these proteins rise to the top as a starting point for developing GV-based nanotechnologies.

Literature Cited

- 1.Ntziachristos V. Going deeper than microscopy: the optical imaging frontier in biology. Nature methods. 2010;7(8):603–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piraner DI, Farhadi A, Davis HC, et al. Going Deeper: Biomolecular Tools for Acoustic and Magnetic Imaging and Control of Cellular function. Biochemistry. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster FS, Pavlin CJ, Harasiewicz KA, Christopher DA, Turnbull DH. Advances in ultrasound biomicroscopy. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2000;26(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee A, Davis HC, Ramesh P, Lu GJ, Shapiro MG. Biomolecular MRI Reporters: evolution of new mechanisms. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barskiy DA, Coffey AM, Nikolaou P, et al. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques of Gases. Chemistry. 2017 Jan 18;23(4):725–751. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrara K, Pollard R, Borden M. Ultrasound microbubble contrast agents: fundamentals and application to gene and drug delivery. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2007:9. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abou-Elkacem L, Bachawal SV, Willmann JK. Ultrasound molecular imaging: Moving toward clinical translation. Eur J Radiol. 2015 Sep;84(9):1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F, Ma M, Wang J, et al. Exosome-like silica nanoparticles: a novel ultrasound contrast agent for stem cell imaging. Nanoscale. 2017;9(1):402–411. doi: 10.1039/c6nr08177k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheeran PS, Luois SH, Mullin LB, Matsunaga TO, Dayton PA. Design of ultrasonically-activatable nanoparticles using low boiling point perfluorocarbons. Biomaterials. 2012 Apr;33(11):3262–3269. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foroutan F, Jokerst JV, Gambhir SS, Vermesh O, Kim HW, Knowles JC. Sol-gel synthesis and electrospraying of biodegradable (P2O5)55-(CaO)30-(Na2O)15 glass nanospheres as a transient contrast agent for ultrasound stem cell imaging. ACS Nano. 2015 Feb 24;9(2):1868–1877. doi: 10.1021/nn506789y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schröder L, Lowery TJ, Hilty C, Wemmer DE, Pines A. Molecular imaging using a targeted magnetic resonance hyperpolarized biosensor. Science. 2006 Oct 20;314(5798):446–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1131847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schröder L. Xenon for NMR biosensing – Inert but alert. Physica Medica. 2013;29(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2011.11.001. 2013/01// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roose BW, Zemerov SD, Dmochowski IJ. Nanomolar small-molecule detection using a genetically encoded Xe-129 NMR contrast agent. Chemical Science. 2017 Nov 1;8(11):7631–7636. doi: 10.1039/c7sc03601a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Dmochowski IJ. An Expanded Palette of Xenon-129 NMR Biosensors. Acc Chem Res. 2016 Oct 18;49(10):2179–2187. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro MG, Goodwill PW, Neogy A, et al. Biogenic gas nanostructures as ultrasonic molecular reporters. Nature Nanotechnology. 2014;9(4):311–316. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro MG, Ramirez RM, Sperling LJ, et al. Genetically encoded reporters for hyperpolarized xenon magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Chem. 2014;6(7):629–634. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakshmanan A, Farhadi A, Nety SP, et al. Molecular Engineering of Acoustic Protein Nanostructures. ACS Nano. 2016;10(8):7314–7322. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03364. 2016/06/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherin E, Melis JM, Bourdeau RW, et al. Acoustic Behavior of Halobacterium salinarum Gas Vesicles in the High-Frequency Range: Experiments and Modeling. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2017;43(5):1016–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakshmanan A, Lu GJ, Farhadi A, et al. Preparation of biogenic gas vesicle nanostructures for use as contrast agents for ultrasound and MRI. Nature protocols. 2017;12(10):2050. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maresca D, Lakshmanan A, Lee-Gosselin A, et al. Nonlinear ultrasound imaging of nanoscale acoustic biomolecules. Appl Phys Lett. 2017 Feb 13;110(7):073704. doi: 10.1063/1.4976105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeifer F. Distribution, formation and regulation of gas vesicles. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012 Oct;10(10):705–715. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsby AE. Gas vesicles. Microbiol Rev. 1994 Mar;58(1):94–144. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.94-144.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourdeau RW, Lee-Gosselin A, Lakshmanan A, et al. Acoustic reporter genes for noninvasive imaging of microorganisms in mammalian hosts. Nature. 2018 Jan 3;553(7686):86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature25021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witte C, Kunth M, Rossella F, Schroder L. Observing and preventing rubidium runaway in a direct-infusion xenon-spin hyperpolarizer optimized for high-resolution hyper-CEST (chemical exchange saturation transfer using hyperpolarized nuclei) NMR. J Chem Phys. 2014 Feb 28;140(8):084203. doi: 10.1063/1.4865944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li N, Cannon MC. Gas vesicle genes identified in Bacillus megaterium and functional expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998 May;180(9):2450–2458. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2450-2458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes P, Buchholz B, Walsby A. Gas vesicles are strengthened by the outer-surface protein, GvpC. Archives of microbiology. 1992;157(3):229–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00245155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsby AE, Revsbech NP, Griffel DH. The Gas-Permeability Coefficient of the Cyanobacterial Gas Vesicle Wall. J Gen Microbiol. 1992 Apr;138:837–845. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and MR Z-spectroscopy in vivo: a review of theoretical approaches and methods. Physics in medicine and biology. 2013 Nov 21;58(22):R221–R269. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/22/R221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaiss M, Schnurr M, Bachert P. Analytical solution for the depolarization of hyperpolarized nuclei by chemical exchange saturation transfer between free and encapsulated xenon (HyperCEST) Journal of Chemical Physics. 2012 Apr 14;136(14) doi: 10.1063/1.3701178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunth M, Witte C, Schröder L. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer with hyperpolarized nuclei (qHyper-CEST): Sensing xenon-host exchange dynamics and binding affinities by NMR. J Chem Phys. 2014;141(19):194202. doi: 10.1063/1.4901429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Roose BW, Palovcak EJ, Carnevale V, Dmochowski IJ. A Genetically Encoded β‐Lactamase Reporter for Ultrasensitive 129Xe NMR in Mammalian Cells. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2016;55(31):8984–8987. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]