Abstract

Background:

To assess long-term effectiveness of an intensive and comprehensive Ryan White Part A-funded HIV Care Coordination Program (CCP) recruiting people living with HIV (PLWH) with a history of suboptimal HIV care outcomes.

Methods:

We merged programmatic data on CCP clients with surveillance data on all adults diagnosed with HIV. Using propensity score matching, we identified a contemporaneous, non-CCP exposed comparison group. Durable viral suppression (DVS) was defined as regular VL monitoring and all VLs ≤200 copies/mL in months 13–36 of follow-up.

Results:

Ninety percent of the combined cohort (N=12,414) had ≥1 VL≤200 during the follow-up period (December 1, 2009 to March 31, 2016), and nearly all had routine VL monitoring, but only 36.8% had DVS. While DVS did not differ overall (relative risk[RR]: 0.99, 95%CI: 0.95–1.03), CCP clients without any VL suppression in the 12 months pre-enrollment showed higher DVS versus ‘usual care’ recipients (21.3% versus 18.4%; RR: 1.16, 95%CI: 1.04–1.29).

Conclusions:

Enrollment in an intensive intervention modestly improved DVS among those unsuppressed prior to CCP enrollment. This program shows promise for meeting treatment-as-prevention goals and advancing progress along the HIV care continuum, if people without evidence of VLS are prioritized for CCP enrollment over those with recent evidence of VLS. Low overall DVS (<40%) levels underscore a need for focused adherence-maintenance interventions, in a context of high treatment access.

Keywords: Treatment Engagement, Long-term Outcomes, HIV Viral load, Ryan White, Implementation Science, Care Coordination

INTRODUCTION

For the individual and population benefits of treatment to be realized, the time from HIV infection to durable viral suppression (DVS) must be minimized, which requires early diagnosis, linkage to medical care, and consistent access and adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART).1–5 Many persons living with HIV (PLWH), however, may not achieve viral load suppression (VLS) or DVS as a result of difficulties accessing medical care and/or initiating and adhering to treatment. Nationally, one-third of persons receiving HIV medical care in 2011 did not have DVS over a two-year period (2012–2013) and had persistent viremia at levels associated with HIV transmission (>1500 copies/mL).6 These data underscore the need for interventions that support consistent ART adherence.

The New York City (NYC) Ryan White Part A HIV Care Coordination Program (CCP) employs multiple strategies to promote care and treatment engagement among Ryan White clients at risk for poor HIV care outcomes (e.g., non-adherence to ART).7,8 Previous work has demonstrated that the CCP increases short-term VLS when comparing an individual’s year before to year after program enrollment.7,8 However, this prior work did not assess longer-term CCP effectiveness (i.e., more than 12 months after enrollment). Furthermore, VLS among all NYC residents in HIV medical care improved annually from 2009 to 2016 and in tandem with population-based HIV treatment strategies (e.g., the recommendation that all PLWH initiate ART at diagnosis regardless of CD4+ lymphocyte count (CD4)). 9–11 The pre-post effectiveness evaluations do not isolate program effects from these secular changes or address longer-term effectiveness.

We therefore aimed to compare DVS among CCP enrollees with DVS in a contemporaneous, non-CCP exposed comparison of HIV patients, and to describe CCP enrollees who did not experience DVS.

METHODS

Intervention Description

In December 2009, with Ryan White Part A funding, the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) launched the CCP. The intervention has previously been described, and program materials are available on the DOHMH website. 7,8,12–14 CCP protocols permit enrollment of HIV-infected adults or emancipated minors who are eligible for local Ryan White Part A services (based on residence within the New York grant area and household income <435% of federal poverty level) and who are (1) newly diagnosed with HIV; (2) never in care or lost to care for ≥9 months; (3) irregularly in care or often missing appointments; (4) starting a new ART regimen; (5) experiencing ART adherence barriers; or (6) manifesting treatment failure or ART resistance.8 The CCP combines various evidence-based elements, including case management by interdisciplinary care teams, patient navigation, and structured health promotion, and was rolled out as a service program without a designated comparison group.

Data Sources

We retrospectively created an observational cohort of persons enrolled and not enrolled in the CCP by merging longitudinal population-based surveillance and programmatic data sources. CCP programmatic data were drawn from the DOHMH Electronic System for HIV/AIDS Reporting and Evaluation. The HIV Surveillance Registry (“the Registry”) contains demographic and clinical information on all diagnoses of HIV reported in NYC, as well as comprehensive HIV-related laboratory reporting (including all CD4 and VL results for individuals who have received HIV medical care in NYC).15 Vital status information is updated through regular matches with death data.11

Using programmatic data, we identified all persons who enrolled in the CCP from December 1, 2009 to March 31, 2013 and excluded clients who died within 12 months of program enrollment (N = 279). Using Registry data, we identified all persons who were diagnosed with HIV as of March 31, 2013 and ≥18 years old at diagnosis.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at (redacted for review). For these secondary analyses of de-identified data, we received a waiver of informed consent under 45 CFR 46.116(d)(2).

Constructing a contemporaneous comparison group

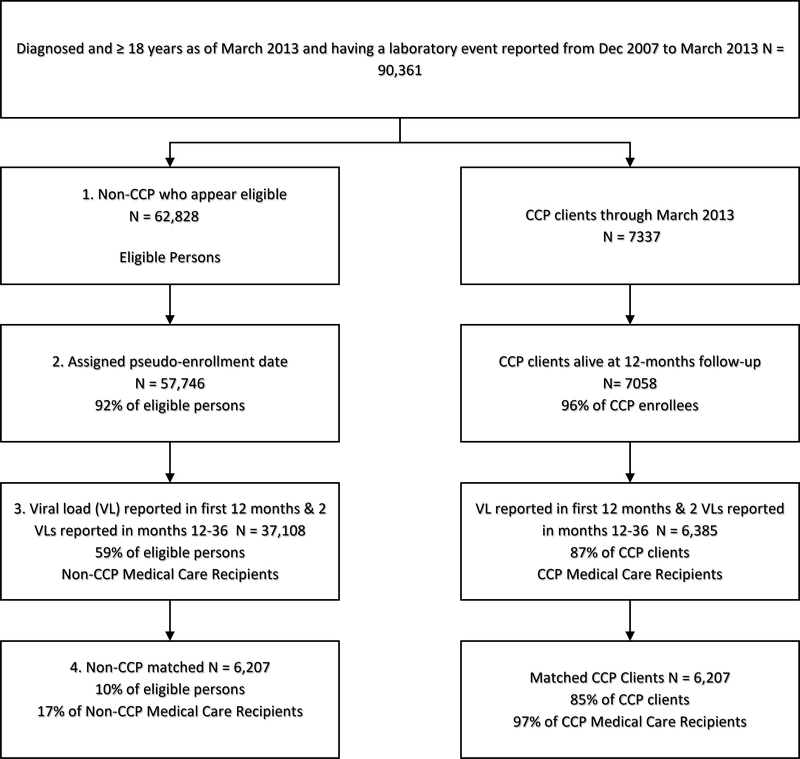

We merged programmatic data with Registry data to identify non-CCP persons who were potentially eligible for inclusion in the comparison group, via a four-step process (Figure 1 – left column). Our approach has been described elsewhere and can be summarized as follows (see Supplemental Appendix 1 for full details on the four-step process).12

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Study Inclusion for Care Coordination Program (CCP) and non-CCP Groups, New York City, 2009–2013

First, to identify non-CCP PLWH who could have been enrolled in the CCP, we created CCP eligibility windows: ranges of time between December 2009 and March 2013 where the person appeared eligible for enrollment in the CCP. For persons who died, we closed their eligibility windows ≥12 months prior to the date of death, to ensure comparability with the CCP group. For a description of the Registry-based eligibility criteria and enrollment eligibility windows, see Supplemental Table 1.

Second, we randomly assigned non-CCP PLWH a pseudo-enrollment date that fell within their eligibility window(s); this was the time-point used to start follow-up and outcome assessment. The temporal distribution of dates among the non-CCP PLWH matched that of the enrollment dates among CCP enrollees.

Third, we restricted to persons who had ≥1 VL in months 0–12 after enrollment/pseudo-enrollment and ≥2 VLs in months 13–36. We required a minimum number of VLs as a proxy for ongoing receipt of NYC HIV medical care to prevent a differential (non-CCP versus CCP) effect of outmigration, which we suspected to have occurred more frequently among non-CCP than CCP persons, as CCP enrollment and services require residence in NYC.

Finally, we matched CCP enrollees to the non-CCP PLWH on enrollment/pseudo-enrollment date, baseline treatment status, and propensity for CCP enrollment. The four baseline treatment status groups were defined in terms of diagnosis or VLS in the 12 months prior to enrollment/pseudo-enrollment: 1) newly diagnosed, 2) consistently suppressed (≥2 VLs ≥90 days apart and all VLs ≤200 copies/mL), 3) no evidence of VLS (all VLs reported >200 copies/mL or lacking any VL report), or 4) inconsistently suppressed (≥1 VL ≤200 copies/mL, but not all VLs ≤200 copies/mL).

Outcome Definitions

The follow-up period extended from December 1, 2009 to March 31, 2016, which allowed for 36 months of follow-up. We defined DVS as regular VL monitoring and all VLs ≤200 copies/mL in months 13–36 of follow-up.6 We excluded months 0–12 from the definition of DVS to allow one year for all members of the cohort to establish medical care. Regular VL monitoring was defined as having ≥1 VL in each 12-month period of follow-up and ≥90 days between the first and the last VL reported during months 13–36. For persons known to have died, regular VL monitoring was defined as having ≥1 VL result in each 12-month period of follow-up for which they were alive. To assess differences in treatment outcomes beyond those that might be explained primarily by low-level viremia, we examined DVS at a higher VL threshold of 1500 copies/mL. We chose thresholds in recognition of clinical guidelines for individual health (≤200 copies/mL) and for minimizing risk of HIV transmission (≤1500 copies/mL).16

Because persons with more VL monitoring have more opportunities to fail the DVS measure, we also examined DVS using the 200 threshold and the first and last VL reported during months 13–36.

For context as to ART access/uptake, we examined the outcome of ever having VLS after enrollment (defined as ≥1 VL ≤200 copies/mL in the 36 months after enrollment/pseudo-enrollment).

Covariates

Among CCP enrollees, we used demographic, clinical and psychosocial characteristics collected at the time of CCP enrollment to examine predictors of not having DVS. Unstable housing was defined as homelessness, reliance on temporary or transitional housing, residence in institutional housing, or residence in someone else’s unit with the expectation of staying fewer than six months. Recent drug use was defined as self-reported use of heroin, cocaine/crack, methamphetamine, or prescription drugs for recreational purposes during the three months prior to enrollment. Mood disorder was defined as a self-reported mental health diagnosis related to depression, bipolar disorder, or other mood disorders. Heart disease was defined as a self-reported diagnosis of heart disease, hypertension, or high blood pressure. We selected these variables because they were either standard demographics or important predictors of improved VLS in our single-group, pre-post estimates of CCP effectiveness.7,8

Length of CCP enrollment was measured as the number of days from the date of enrollment to the earlier of: program drop-out or graduation, death, or March 31, 2016.

Statistical Analysis

Through an intention-to-treat approach, we examined the effectiveness of the CCP on DVS or ever experiencing VLS. We used a log binomial regression model, accounting for the matched design, and modelled within each baseline treatment status group and overall. To describe predictors of not experiencing DVS among CCP enrollees, we used logistic regression and included all variables in Table 4 in the final adjusted model. To assess whether DVS increased with duration in the CCP, we characterized DVS by length of enrollment and used the Cochran-Armitage test for trend.

Table 4.

Odds of Not Experiencing Durable Viral Suppression1 Among Care Coordination Program Clients –New York City, 2009–2013

| Characteristics | Number (%) Without DVS | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3,937 (63.4) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2,504 (63.3) | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1,433 (63.6) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.13) | 0.85 (0.73, 1.00) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 2,252 (67.8) | 1.71 (1.38, 2.12) | 1.48 (1.16, 1.90) |

| Hispanic | 1,426 (60.1) | 1.22 (0.98, 1.52) | 1.10 (0.85, 1.41) |

| White | 207 (55.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Other | 52 (38.2) | 0.50 (0.34, 0.75) | 0.77 (0.49, 1.20) |

| Age at Enrollment | |||

| ≤24 | 299 (64.0) | 2.03 (1.45, 2.85) | 2.43 (1.65, 3.59) |

| 25–44 | 1,689 (65.1) | 2.13 (1.59, 2.84) | 1.95 (1.40, 2.71) |

| 45–64 | 1,857 (63.0) | 1.94 (1.46, 2.60) | 1.38 (1.00, 1.89) |

| 65+ | 92 (46.7) | Ref | Ref |

| Country of Birth | |||

| US/US Dependency | 2,803 (67.7) | 1.93 (1.71, 2.19) | 1.20 (1.03, 1.39) |

| Foreign Born | 720 (52.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Unknown | 414 (60.7) | 1.42 (1.18, 1.72) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.30) |

| Transmission Risk | |||

| Men who have sex with men | 1,056 (59.1) | Ref | Ref |

| Injection drug use history | 942 (70.7) | 1.67 (1.44, 1.94) | 1.37 (1.11, 1.68) |

| Heterosexual | 1,061 (63.2) | 1.19 (1.04, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.03, 1.53) |

| Other/Unknown | 878 (62.4) | 1.15 (1.00, 1.33) | 1.01 (0.84, 1.21) |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||

| Prior to 1995 | 813 (69.3) | 2.50 (2.10, 2.98) | 2.70 (2.15, 3.38) |

| 1995–1999 | 741 (66.1) | 2.16 (1.81, 2.58) | 2.47 (1.98, 3.07) |

| 2000–2004 | 1,155 (68.8) | 2.45 (2.08, 2.88) | 2.78 (2.28, 3.39) |

| 2005–2009 | 763 (60.9) | 1.73 (1.46, 2.05) | 1.89 (1.56, 2.29) |

| 2010–2013 | 465 (47.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Viral Load at Baseline | |||

| ≤200 | 864 (43.4) | Ref | Ref |

| 201–1499 | 458 (71.9) | 3.34 (2.75, 4.05) | 3.51 (2.86, 4.31) |

| >1500 | 2,481 (74.0) | 3.71 (3.30, 4.17) | 3.72 (3.24, 4.27) |

| No Viral Load | 134 (59.6) | 1.92 (1.45, 2.54) | 2.94 (1.99, 4.35) |

| CD4 at Baseline | |||

| <200 | 1,502 (75.3) | 2.69 (2.33, 3.10) | 1.48 (1.25, 1.74) |

| 200–349 | 848 (63.1) | 1.51 (1.30, 1.75) | 1.01 (0.86, 1.20) |

| 350 – 499 | 627 (57.6) | 1.20 (1.03, 1.40) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.16) |

| 500+ | 825 (53.1) | Ref | Ref |

| No CD4 Count | 135 (59.2) | 1.28 (0.97, 1.70) | 1.00 (0.67, 1.47) |

| Year of Enrollment | |||

| 2009/10 | 1,656 (68.0) | 1.65 (1.30, 2.10) | 1.38 (1.06, 1.81) |

| 2011 | 1,299 (62.8) | 1.31 (1.03, 1.67) | 1.11 (0.85, 1.45) |

| 2012 | 808 (57.9) | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) |

| 2013 | 174 (56.3) | Ref | Ref |

| Housing Status | |||

| Homeless/Unstably Housed | 972 (71.7) | 1.64 (1.43, 1.87) | 1.20 (1.04, 1.40) |

| Stably Housed | 2,856 (60.8) | Ref | Ref |

| Unknown | 109 (70.3) | 1.53 (1.08, 2.17) | 1.27 (0.87, 1.85) |

| Education | |||

| <High School | 1,824 (65.7) | 1.54 (1.27, 1.86) | 1.18 (0.94, 1.47) |

| High School Graduate | 1,721 (62.3) | 1.32 (1.10, 1.60) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.30) |

| College Graduate | 291 (55.5) | Ref | Ref |

| Unknown | 101 (69.7) | 1.84 (1.24, 2.72) | 1.36 (0.88, 2.12) |

| Insurance | |||

| Uninsured | 355 (52.1) | Ref | Ref |

| Insured | 3,081 (63.6) | 1.60 (1.36, 1.88) | 1.27 (1.05, 1.53) |

| Missing | 501 (73.7) | 2.57 (2.05, 3.23) | 1.76 (1.36, 2.28) |

| Income Group | |||

| <$9,000 | 1,707 (64.4) | 1.88 (1.55, 2.29) | 1.28 (1.01, 1.62) |

| $9,000-$19999 | 1,177 (65.7) | 1.99 (1.62, 2.44) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.78) |

| ≥$20,000 | 232 (49.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Missing | 821 (63.4) | 1.80 (1.46, 2.23) | 1.27 (0.99, 1.63) |

| Employed | |||

| Full-Time/Part-Time | 558 (54.1) | Ref | Ref |

| Not Employed | 3,277 (65.3) | 1.59 (1.39, 1.83) | 1.11 (0.94, 1.32) |

| Unknown | 102 (65.0) | 1.57 (1.11, 2.23) | 1.35 (0.91, 2.00) |

| Drug Use | |||

| None | 3,031 (60.9) | Ref | Ref |

| Recent Drug Use | 740 (77.5) | 2.21 (1.88, 2.60) | 1.53 (1.27, 1.83) |

| Missing | 166 (61.0) | 1.01 (0.78, 1.29) | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) |

| Incarceration | |||

| Never Incarcerated | 2,480 (59.1) | Ref | Ref |

| Ever | 1,372 (73.4) | 1.91 (1.69, 2.15) | 1.31 (1.13, 1.51) |

| Missing | 85 (59.4) | 1.01 (0.72, 1.42) | 0.77 (0.52, 1.12) |

| Mood Disorder | |||

| No | 2,145 (60.5) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1,621 (67.9) | 1.38 (1.24, 1.54) | 1.18 (1.04, 1.34) |

| Missing | 171 (62.9) | 1.11 (0.86, 1.43) | 1.08 (0.80, 1.46) |

| Hepatitis C | |||

| No | 3,144 (62.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 586 (68.1) | 1.29 (1.10, 1.50) | 0.94 (0.78, 1.14) |

| Missing | 207 (68.1) | 1.29 (1.01, 1.65) | |

| Heart Disease/High Blood Pressure | |||

| No | 3,125 (64.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 605 (59.5) | 0.83 (0.72, 0.95) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.01) |

| Missing | 207 (68.1) | 1.20 (0.94, 1.54) | |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 3,401 (63.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 329 (61.2) | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) | 1.23 (0.99, 1.51) |

| Missing | 207 (68.1) | 1.23 (0.96, 1.58) | 1.25 (0.93, 1.69) |

Demographic and clinical data reported to the HIV Registry as of September 30, 2014. Death and viral load outcome data reported to the HIV Registry as of October 31, 2016. Psycho-social characteristics and comorbidities reported to eSHARE as of September 18, 2016

All viral loads ≤200 copies/mL and maintain regular VL monitoring throughout the 24 months of follow-up (i.e., having ≥1 VL in each 12-month period of follow-up and at least 90 days between the first and the last VLs reported during months 13–36); otherwise they will be classified as DVS=‘No’

All analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From December 1, 2009 to March 31, 2013, 7,337 persons enrolled in the CCP, of whom 7,058 (96%) were alive 12 months post-enrollment; 87% (6,385) of CCP enrollees had evidence of medical care in NYC. Of the 62,828 persons who appeared eligible but were not enrolled in the CCP, 92% (57,746) were assigned a pseudo-enrollment date; 59% (37,108) had evidence of care in NYC, and 10% were 1:1 propensity-matched to a CCP enrollee (6,207 in non-CCP and 6,207 in CCP). Thus, 85% (6,207/7,337) of all persons enrolling in the CCP were included in this analysis (Figure 1).

The matched CCP and non-CCP PLWH were similar on measured characteristics: 64% were male, 92% were non-Latino black or Latino, 50% were aged 45 years or older, and 29% were reported as men who have sex with men (MSM) (Table 1). Most (68%) of the cohort came from NYC neighborhoods with the highest poverty rates and the highest HIV prevalence rates. At enrollment/pseudo-enrollment, 32% had a VL ≤200 copies/mL and 32% had CD4 <200 cells/uL. In the year prior to enrollment/pseudo-enrollment, 15% were newly diagnosed, 15% were consistently virally suppressed, 41% had no evidence of VLS, and 29% were inconsistently suppressed. Among CCP enrollees, 22% were homeless or unstably housed, 45% had less than a high school education, 81% were unemployed, 15% reported recent drug use, and 39% reported a mood disorder at baseline (data not shown). Similar information was not available for non-CCP PLWH.

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of New York City (NYC) Care Coordination Program (CCP) and Non-CCP Groups - New York City, 2009–2013

| Pre-Match | Post-Match | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total | Non-CCP | CCP | Total | Non-CCP | CCP |

| Total | 43,493 (100.0) | 37,108 (100.0) | 6,385 (100.0) | 12,414 (100.0) | 6,207 (100.0) | 6,207 (100.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 30,657 (70.5) | 26,604 (71.7) | 4,053 (63.5) | 7,906 (63.7) | 3,951 (63.7) | 3,955 (63.7) |

| Female | 12,836 (29.5) | 10,504 (28.3) | 2,332 (36.5) | 4,508 (36.3) | 2,256 (36.3) | 2,252 (36.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Latino black | 20,591 (47.3) | 17,191 (46.3) | 3,400 (53.2) | 6,736 (54.3) | 3,414 (55.0) | 3,322 (53.5) |

| Latino | 14,413 (33.1) | 11,956 (32.2) | 2,457 (38.5) | 4,701 (37.9) | 2,327 (37.5) | 2,374 (38.2) |

| Non-Latino white | 7,529 (17.3) | 7,152 (19.3) | 377 (5.9) | 718 (5.8) | 343 (5.5) | 375 (6.0) |

| Other/Unknown | 960 (2.2) | 809 (2.2) | 151 (2.4) | 259 (2.1) | 123 (2.0) | 136 (2.2) |

| Age Category | ||||||

| ≤24 | 2,760 (6.3) | 2,272 (6.1) | 488 (7.6) | 1,003 (8.1) | 536 (8.6) | 467 (7.5) |

| 25–44 | 17,432 (40.1) | 14,755 (39.8) | 2,677 (41.9) | 5,172 (41.7) | 2,576 (41.5) | 2,596 (41.8) |

| 45–64 | 21,748 (50.0) | 18,737 (50.5) | 3,011 (47.2) | 5,845 (47.1) | 2,898 (46.7) | 2,947 (47.5) |

| 65+ | 1,553 (3.6) | 1,344 (3.6) | 209 (3.3) | 394 (3.2) | 197 (3.2) | 197 (3.2) |

| Transmission Risk | ||||||

| Men who have sex with men | 16,332 (37.6) | 14,505 (39.1) | 1,827 (28.6) | 3,598 (29.0) | 1,810 (29.2) | 1,788 (28.8) |

| Injection drug use history | 7,349 (16.9) | 5,976 (16.1) | 1,373 (21.5) | 2,640 (21.3) | 1,307 (21.1) | 1,333 (21.5) |

| Heterosexual | 9,685 (22.3) | 7,940 (21.4) | 1,745 (27.3) | 3,347 (27.0) | 1,668 (26.9) | 1,679 (27.1) |

| Other/unknown | 10,127 (23.3) | 8,687 (23.4) | 1,440 (22.6) | 2,829 (22.8) | 1,422 (22.9) | 1,407 (22.7) |

| Country of Birth | ||||||

| US/US dependency | 28,422 (65.3) | 24,197 (65.2) | 4,225 (66.2) | 8,352 (67.3) | 4,211 (67.8) | 4,141 (66.7) |

| Foreign born | 8,055 (18.5) | 6,584 (17.7) | 1,471 (23.0) | 2,721 (21.9) | 1,337 (21.5) | 1,384 (22.3) |

| Unknown | 7,016 (16.1) | 6,327 (17.1) | 689 (10.8) | 1,341 (10.8) | 659 (10.6) | 682 (11.0) |

| Year of HIV Diagnosis | ||||||

| Prior 1995 | 8,258 (19.0) | 7,061 (19.0) | 1,197 (18.7) | 2,333 (18.8) | 1,159 (18.7) | 1,174 (18.9) |

| 1995–1999 | 8,158 (18.8) | 7,012 (18.9) | 1,146 (17.9) | 2,204 (17.8) | 1,083 (17.4) | 1,121 (18.1) |

| 2000–2004 | 11,908 (27.4) | 10,206 (27.5) | 1,702 (26.7) | 3,385 (27.3) | 1,706 (27.5) | 1,679 (27.1) |

| 2005–2009 | 8,970 (20.6) | 7,688 (20.7) | 1,282 (20.1) | 2,530 (20.4) | 1,278 (20.6) | 1,252 (20.2) |

| 2010–2013 | 6,199 (14.3) | 5,141 (13.9) | 1,058 (16.6) | 1,962 (15.8) | 981 (15.8) | 981 (15.8) |

| Baseline Viral Load | ||||||

| ≤200 | 18,345 (42.2) | 16,304 (43.9) | 2,041 (32.0) | 3,976 (32.0) | 1,985 (32.0) | 1,991 (32.1) |

| >200–1499 | 5,804 (13.3) | 5,168 (13.9) | 636 (10.0) | 1,303 (10.5) | 666 (10.7) | 637 (10.3) |

| >1500 | 14,795 (34.0) | 11,316 (30.5) | 3,479 (54.5) | 6,673 (53.8) | 3,319 (53.5) | 3,354 (54.0) |

| No viral load | 4,549 (10.5) | 4,320 (11.6) | 229 (3.6) | 462 (3.7) | 237 (3.8) | 225 (3.6) |

| Baseline CD4 Count | ||||||

| <200 | 7,430 (17.1) | 5,328 (14.4) | 2,102 (32.9) | 3,929 (31.6) | 1,934 (31.2) | 1,995 (32.1) |

| 200–349 | 7,835 (18.0) | 6,460 (17.4) | 1,375 (21.5) | 2,666 (21.5) | 1,323 (21.3) | 1,343 (21.6) |

| 350 – 499 | 8,293 (19.1) | 7,192 (19.4) | 1,101 (17.2) | 2,191 (17.6) | 1,103 (17.8) | 1,088 (17.5) |

| 500+ | 15,629 (35.9) | 14,051 (37.9) | 1,578 (24.7) | 3,158 (25.4) | 1,605 (25.9) | 1,553 (25.0) |

| No CD4 | 4,306 (9.9) | 4,077 (11.0) | 229 (3.6) | 470 (3.8) | 242 (3.9) | 228 (3.7) |

| Initiated Care ≤91 Days | ||||||

| No | 29,666 (68.2) | 25,353 (68.3) | 4,313 (67.5) | 8,439 (68.0) | 4,212 (67.9) | 4,227 (68.1) |

| Yes | 13,827 (31.8) | 11,755 (31.7) | 2,072 (32.5) | 3,975 (32.0) | 1,995 (32.1) | 1,980 (31.9) |

| Baseline Prevalence & Poverty | ||||||

| High poverty & high prevalence | 24,047 (55.3) | 19,722 (53.1) | 4,325 (67.7) | 8,465 (68.2) | 4,265 (68.7) | 4,200 (67.7) |

| Low poverty & high prevalence | 10,048 (23.1) | 8,918 (24.0) | 1,130 (17.7) | 2,175 (17.5) | 1,072 (17.3) | 1,103 (17.8) |

| High poverty & low prevalence | 1,420 (3.3) | 1,186 (3.2) | 234 (3.7) | 432 (3.5) | 211 (3.4) | 221 (3.6) |

| Low poverty & low prevalence | 5,674 (13.0) | 5,065 (13.6) | 609 (9.5) | 1,169 (9.4) | 573 (9.2) | 596 (9.6) |

| Unknown | 2,304 (5.3) | 2,217 (6.0) | 87 (1.4) | 173 (1.4) | 86 (1.4) | 87 (1.4) |

| Number of Viral Load Labs | ||||||

| 0 VL labs | 4,549 (10.5) | 4,320 (11.6) | 229 (3.6) | 462 (3.7) | 237 (3.8) | 225 (3.6) |

| 1–3 VL labs | 23,778 (54.7) | 20,401 (55.0) | 3,377 (52.9) | 6,667 (53.7) | 3,379 (54.4) | 3,288 (53.0) |

| 4+ VL labs | 15,166 (34.9) | 12,387 (33.4) | 2,779 (43.5) | 5,285 (42.6) | 2,591 (41.7) | 2,694 (43.4) |

| Baseline Treatment Status | ||||||

| Newly diagnosed1 | 6,203 (14.3) | 5,224 (14.1) | 979 (15.3) | 1,836 (14.8) | 918 (14.8) | 918 (14.8) |

| Consistently Suppressed2 | 5,371 (12.3) | 4,397 (11.8) | 974 (15.3) | 1,850 (14.9) | 925 (14.9) | 925 (14.9) |

| No evidence of suppression3 | 15,765 (36.2) | 13,162 (35.5) | 2,603 (40.8) | 5,084 (41.0) | 2,542 (41.0) | 2,542 (41.0) |

| Inconsistently suppressed4 | 16,154 (37.1) | 14,325 (38.6) | 1,829 (28.6) | 3,644 (29.4) | 1,822 (29.4) | 1,822 (29.4) |

Demographic and clinical characteristics reported to the HIV Registry as of September 30, 2014. Programmatic data (enrollment in CCP or not) reported to eSHARE as of September 18, 2016

Newly diagnosed within 12 months of pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

At least 2 VLs at least 90 days apart and all VLS ≤ 200 copies/mL in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

All labs reported >200 or no viral loads reported in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

At least 1 VL ≤200 copies/μL, but not all VLs ≤200 copies/μL in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

Among CCP enrollees and non-CCP PLWH, most (90%) had ≥1 VL ≤200 copies/mL in the 36 months after enrollment/pseudo-enrollment (Table 2). However, only 37% of the cohort experienced DVS in that period, and the proportion varied greatly by baseline treatment status: 71% among the consistently suppressed, 53% among the newly diagnosed, 35% among the inconsistently suppressed, and 20% among persons with no evidence of VLS prior to enrollment/pseudo-enrollment. Using the transmissibility threshold of 1500 copies/mL, 48% had DVS, or approximately 10% more individuals within each baseline treatment status group. Using the first and last VL and the threshold of 200 copies/mL, 49% had DVS; the proportion succeeding in each baseline treatment status group was similar to DVS using the 1500 threshold (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative Risks for Durable Viral Suppression (DVS) at 200 and 1500 copy-threshold and for Ever Having Viral Suppression Among Matched Care Coordination Program (CPP) and Non-CCP Groups–New York City, 2009–2013

| Overall (N = 12,414) | CCP (N = 6,207) | Non-CCP (N = 6,207) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % DVS | N | % DVS | N | % DVS | ||

| DVS at 200 copies/μL threshold, using all viral loads1 | |||||||

| Overall | 4,563 | 36.8 | 2,270 | 36.6 | 2,293 | 36.9 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) |

| Baseline Treatment Status | |||||||

| Newly Diagnosed2 | 969 | 52.8 | 489 | 53.3 | 480 | 52.3 | 1.02 (0.93, 1.11) |

| Consistently Suppressed3 | 1,319 | 71.3 | 650 | 70.3 | 669 | 72.3 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) |

| No Evidence of Suppression4 | 1,012 | 19.9 | 543 | 21.3 | 469 | 18.4 | 1.16 (1.04, 1.29) |

| Inconsistently Suppressed5 | 1,263 | 34.7 | 588 | 32.2 | 675 | 37.0 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.95) |

| DVS at 1500 copies/μL threshold, using all viral loads6 | |||||||

| Overall | 5,974 | 48.1 | 2,987 | 48.1 | 2,987 | 48.1 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

| Baseline Treatment Status | |||||||

| Newly Diagnosed2 | 1,169 | 63.7 | 600 | 65.3 | 569 | 62.0 | 1.05 (0.98, 1.13) |

| Consistently Suppressed3 | 1,542 | 83.4 | 770 | 83.2 | 772 | 83.4 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.04) |

| No Evidence of Suppression4 | 1,487 | 29.3 | 787 | 31.0 | 700 | 27.5 | 1.12 (1.03, 1.23) |

| Inconsistently Suppressed5 | 1,776 | 48.7 | 830 | 45.6 | 946 | 51.9 | 0.87 (0.83, 0.93) |

| DVS at 200 copies/μL threshold, using the first and last viral load7 | |||||||

| Overall | 6,055 | 48.8 | 3,081 | 49.6 | 2,974 | 47.9 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) |

| Baseline Treatment Status | |||||||

| Newly Diagnosed2 | 1,146 | 62.4 | 918 | 60.5 | 591 | 64.4 | 1.06 (0.99, 1.14) |

| Consistently Suppressed3 | 1,520 | 82.2 | 925 | 82.6 | 756 | 81.7 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) |

| No Evidence of Suppression4 | 1,530 | 30.1 | 2,542 | 32.5 | 705 | 27.7 | 1.17 (1.07, 1.27) |

| Inconsistently Suppressed5 | 1,859 | 51.0 | 1,822 | 49.5 | 958 | 52.6 | 0.96 (0.88, 1.00) |

| VL Ever ≤200 copies/μL8 | |||||||

| Overall | 11,165 | 89.9 | 5,670 | 91.3 | 5,495 | 88.5 | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) |

| Baseline Treatment Status | |||||||

| Newly Diagnosed2 | 1,715 | 93.4 | 866 | 94.3 | 849 | 92.5 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) |

| Consistently Suppressed3 | 1,844 | 99.7 | 921 | 99.6 | 923 | 99.8 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) |

| No Evidence of Suppression4 | 4,142 | 81.5 | 2,144 | 84.3 | 1,998 | 78.6 | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) |

| Inconsistently Suppressed5 | 3,464 | 95.1 | 1,739 | 95.4 | 1,725 | 94.7 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.03) |

Data for characterizing baseline treatment status reported to the HIV Registry as of September 30, 2014. Death and viral load outcome data reported to the HIV Registry as of October 31, 2016

All viral loads ≤200 copies/mL and maintain regular VL monitoring throughout the 24 months of follow-up (i.e., having ≥1 VL in each 12-month period of follow-up and at least 90 days between the first and the last VLs reported during months 13–36); otherwise they will be classified as DVS=‘No’

Newly diagnosed within 12 months of pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

At least 2 VLs at least 90 days apart and all VLS < 200 copies/mL in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

All labs reported >200 or no viral loads reported in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

At least 1 VL ≤200 copies/μL, but not all VLs ≤200 copies/μL in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

All viral loads ≤1500 copies/mL and maintain regular VL monitoring throughout the 24 months of follow-up (i.e., having ≥1 VL in each 12-month period of follow-up and at least 90 days between the first and the last VLs reported during months 13–36); otherwise they will be classified as DVS=‘No’

First and last viral loads reported in months 13–36 were ≤200 copies/mL and maintain regular VL monitoring throughout the 24 months of follow-up (i.e., having ≥1 VL in each 12-month period of follow-up and at least 90 days between the first and the last VLs reported during months 13–36); otherwise they will be classified as DVS=‘No’

Viral load ≤200 copies/mL reported within the 36 months after pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

CCP enrollees with no evidence of VLS in the year prior to enrollment were significantly more likely to have DVS when compared to their non-CCP counterparts (RR: 1.16; 95% CI 1.04, 1.29). CCP enrollees with inconsistent evidence of VLS were significantly less likely to have DVS when compared to their non-CCP counterparts (RR: 0.87; 95% CI 0.79, 0.95). For persons newly diagnosed or always suppressed in the year prior to enrollment/pseudo-enrollment, there was no CCP versus non-CCP DVS difference. The relative risks estimated using the 1500 copies/mL threshold were nearly identical to the relative risks for the 200 copies/mL threshold (Table 2). Using the first and last VL, the effect favoring CCP among the no evidence of VLS group remained significant (RR: 1.17; 95% CI 1.07, 1.27), and no CCP versus non-CCP difference was observed among the newly diagnosed or persons with consistent or inconsistent suppression.

A majority of CCP enrollees remained in the program for >365 days (64% of CCP-enrollees, median days enrolled 540, interquartile range 254–1094 days). Persons newly diagnosed or always suppressed were enrolled longer than persons with no evidence of VLS or inconsistent VLS (median days enrolled: 653, 644, 496 and 500, respectively). DVS increased with enrollment duration, for all groups other than those consistently suppressed at baseline (Table 3).

Table 3.

Durable Viral Suppression1 Stratified by Length of Enrollment in the Care Coordination Program Among Matched Care Coordination Program (CPP) Enrollees–New York City, 2009–2013

| Overall | Newly Diagnosed2 | Consistently Suppressed3 | No Evidence of Suppression4 | Inconsistently Suppressed5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N (%) | % DVS1 | Total N (%) | % DVS1 | Total N (%) | % DVS1 | Total N (%) | % DVS1 | Total N (%) | % DVS1 | |

| Days Enrolled - Median (25%ile-75%ile) | 540 (248–1,098) | 653 (360–1,095) | 644 (259–1,095) | 496 (238–1,012) | 500 (239–1,023) | |||||

| Days Enrolled Categories | ||||||||||

| 1–91 | 412 (6.6) | 29.6 | 29 (3.2) | 34.5 | 70 (7.6) | 67.1 | 171 (6.7) | 16.4 | 142 (7.8) | 26.1 |

| 92–182 | 662 (10.7) | 26.4 | 65 (7.1) | 43.1 | 90 (9.7) | 65.6 | 307 (12.1) | 14.7 | 200 (11.0) | 21.5 |

| 183–365 | 1,145 (18.4) | 29.1 | 142 (15.5) | 47.2 | 144 (15.6) | 72.9 | 501 (19.7) | 14.8 | 358 (19.6) | 24.3 |

| 365+ | 3,988 (64.3) | 41.1 | 682 (74.3) | 56.3 | 621 (67.1) | 70.7 | 1,563 (61.5) | 25.3 | 1,122 (67.1) | 37.5 |

| P for trend6 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.39 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||

Data for characterizing baseline treatment status reported to the HIV Registry as of September 30, 2014. Death and viral load outcome data reported to the HIV Registry as of October 31, 2016. Enrollment data reported to eSHARE as of September 18, 2016.

All viral loads ≤200 copies/mL and maintain regular VL monitoring throughout the 24 months of follow-up (i.e., having ≥1 VL in each 12-month period of follow-up and at least 90 days between the first and the last VLs reported during months 13–36); otherwise they will be classified as DVS=‘No’

Newly diagnosed within 12 months of pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

At least 2 VLs at least 90 days apart and all VLS < 200 copies/mL in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

All labs reported >200 or no viral loads reported in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

At least 1 VL ≤200 copies/μL, but not all VLs ≤200 copies/μL in the 12 months prior to pseudo-enrollment/enrollment dates

P-value for trend based on Cochran-Armitage trend test

Regular VL monitoring was absent for only 2% of CCP enrollees (69/3937) and 3% of non-CCP PLWH (104/3810), meaning that failures on DVS were nearly always (98%) due to ≥1 VL surpassing the 200 copies/mL threshold. A VL >200 at CCP enrollment was the greatest predictor of lacking DVS in months 12–36; specifically, persons with a baseline VL of 201–1499 copies/mL or >1500 copies/mL had ≥3.5 times the odds of lacking DVS, when compared to persons who were virally suppressed at enrollment (OR 3.51; 95% CI 2.86, 4.31 and OR 3.72; 95% CI 3.24, 4.27, respectively).

DISCUSSION

NYC PLWH have experienced substantial improvements in VLS over time, likely driven by advances in ART tolerability, increased treatment access, implementation of population-based HIV-prevention strategies, and a robust system of medical and non-medical services for PLWH.10,11,17 Despite these resources and availability of the CCP intervention itself, during 36 months of follow-up, <40% of the analytic cohort experienced DVS. When we examined DVS at the threshold of 1500 copies/mL, a likely threshold for transmissibility16, under half the cohort achieved DVS. Importantly, almost everyone accessed HIV care and treatment during the follow-up period, given that 90% of the total cohort had at least one-time VLS and few persons (<3%) lacked regular VL monitoring. These findings underscore a substantial need for sustained, and perhaps more intensive, adherence support in this vulnerable population with multiple barriers but with high treatment access and uptake.

Among persons with no evidence of VLS in the year prior to baseline (the largest baseline treatment status group, at 41% of the matched cohort), we observed a 16% increase in DVS for CCP enrollees over non-CCP PLWH. This is consistent with our findings on VLS at 12 months, and suggests the program should prioritize previously unsuppressed individuals for enrollment.7,8,12

We did not observe a CCP effect on DVS among newly diagnosed enrollees. The newly diagnosed were the second most likely group to achieve DVS, and were entering a service landscape with simpler and more tolerable drug regimens and an increased emphasis on early treatment, as compared with NYC PLWH who were diagnosed in previous decades. At this stage in the epidemic, persons who are newly diagnosed in NYC may have an easier time with VLS over the long term, regardless of CCP enrollment.

We unexpectedly observed lower DVS among CCP enrollees versus non-CCP PLWH who were inconsistently suppressed in the year prior to enrollment/pseudo-enrollment. The CCP model may perform better at connecting or reconnecting persons with HIV care and treatment than at promoting consistent, long-term treatment success among those who have already (and in the past year) experienced some treatment success. In prior analyses, the inconsistently suppressed CCP enrollees were no more likely to achieve VLS at 12 months than a contemporaneous non-CCP-exposed group (62.2% of CCP with VLS versus 62.3% of non-CCP with VLS, RR=0.99; 95% CI 0.95–1.05).12,18

We suspect the CCP may have had a null effect on DVS among the inconsistently suppressed; however, we observed a negative effect in this group, which we attribute to more frequent VL monitoring. In all baseline treatment status groups, the CCP enrollees had 1 more VL test on average during follow-up than non-CCP PLWH (e.g., inconsistently suppressed CCP enrollees, mean number of VL during follow-up: 7.3, and for inconsistently suppressed non-CCP PLWH: 6.3). More VL monitoring results in more opportunities to fail the DVS measure and consequently more conservative CCP effect estimates, in all baseline groups. However, more frequent VL monitoring may be more likely to negatively bias results among the inconsistently suppressed because this group is defined by its pattern of unstable treatment outcomes, with low and high VL values in the year prior to enrollment. In support of this explanation, when we examined DVS and ever suppression (i.e., metrics based on the same number of VL reports in the CCP and non-CCP groups), we observed no difference in outcomes between CCP and non-CCP PLWH with inconsistent suppression at baseline.

The low proportion of PLWH who achieved DVS, regardless of program enrollment and despite high levels of VL monitoring, is concerning, as the health of individual patients and the success of HIV prevention efforts are determined primarily by the ability to maintain long-term adherence to ART.1–4,19 Except for persons who were consistently suppressed prior to enrollment/pseudo-enrollment, our cohort of vulnerable clients, not surprisingly, demonstrated lower success on DVS over a two-year period than the 62% estimate from a national cohort of recently diagnosed PLWH receiving medical care.6 The best predictor of not having DVS was an unsuppressed baseline VL, which may be indicative of longstanding difficulties with medical care and/or other major barriers to treatment adherence.

DVS increased with length of enrollment in the program for all groups except the consistently suppressed. However, the increase among the CCP-enrollees does not necessarily translate to an improved CCP effect relative to non-CCP. First, a majority were CCP enrolled for ≥365 days; thus, the proportion with DVS overall is weighted toward the proportion with DVS among those enrolled for ≥365 days. Second, as a sensitivity analysis, we examined DVS among CCP enrollees who were enrolled for ≥365 days versus their matched pairs. This showed a positive CCP effect among the group with no evidence of suppression (25% with DVS in CCP versus 18% with VLS in non-CCP; RR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.22–1.60), and a null CCP effect in the other three baseline groups. Thus, relative to non-CCP, the results from the sensitivity analysis remain the same as results from the intention-to-treat analyses. Notably, however, given we balanced propensity scores in the overall group, this sensitivity analysis is subject to confounding beyond that in the intention-to-treat analyses.

Case management interventions vary significantly in design and target population, making cross-study comparisons difficult.20 Randomized trials of case management interventions have not evaluated VLS outcomes; however, data from trials suggests that case management (versus usual care) results in improved linkage to care and retention in HIV medical care.21–23 Cohort studies of case management interventions have evaluated VLS outcomes and reported null results among the general Ryan White population or among marginally housed PLWH.23,24 Notably, these cohort studies did not present results stratified by baseline VLS status or examine VLS beyond the first year.

Our study has several limitations. First, to control for confounding, we were limited to variables available in the Registry, as the common data source. Second, we were not able to account for service delivery models received by non-CCP PLWH. Third, we did not include persons who died in the first 12 months after enrollment. The CCP aims to enroll persons most at risk for poor HIV outcomes, including those for whom the intervention may represent a last attempt to avert mortality. There is no analogous entry point for non-CCP PLWH, as pseudo-enrollment date assignment is random. To increase the comparability of CCP with non-CCP groups, we required individuals have ≥12 months of observation beyond their pseudo-enrollment/enrollment.

Fourth, we restricted this analysis to individuals with ≥3 VL tests during the 36 months of follow-up. As a result, persons with no surveillance-based evidence of care following enrollment/pseudo-enrollment were excluded. However, investigations in NYC and other metropolitan areas suggest that laboratory reports to HIV surveillance underestimate the proportion engaged in care or virally suppressed, due to outmigration.25–31 In examinations of short-term VLS (within 12 months of enrollment), this restriction resulted in more conservative estimates of any CCP effect, and we suspect this restriction would also result in more conservative DVS estimates, given that longer follow-up allows more time for outmigration.

The strengths of our study include the use of a population-based data source to derive the observational comparison group and to measure longitudinal outcomes. Thus, outcome data were available regardless of care location or duration of intervention enrollment. As a result, we had ≥three years of follow-up on all persons who were alive at the end of follow-up (95% of the overall cohort), and we were able to examine different VL outcomes and thresholds. Finally, annual citywide improvements in VLS have occurred in tandem with advances in population-based HIV treatment strategies. A strength of our contemporaneous comparison group approach is that matching on enrollment/pseudo-enrollment dates isolates program effects from secular improvements in VLS.12

In this intent-to-treat analysis, the CCP showed an effect on DVS among those previously unsuppressed in the 12 months prior to CCP enrollment, who constituted the largest baseline clinical-status group (41% of our cohort). People without evidence of VLS should be prioritized for CCP enrollment over those with recent evidence of VLS. During 36 months of follow-up, 90% of the cohort had one-time VLS, but <40% of the cohort experienced DVS. These findings underscore the need for more intensive efforts to sustain adherence over time among persons with a history of poor HIV care outcomes and a high prevalence of major barriers, in a context of high treatment access/uptake.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01 MH101028].

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: none declared

CONFERENCES: This data was presented in part at the 12th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence in Miami, Florida from June 4–6, 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Insight Start Study Group, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temprano Anrs Study Group, Danel C, Moh R, et al. A Trial of Early Antiretrovirals and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(3):257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepaz N, Tang T, Marks G, Mugavero MJ, Espinoza L, Hall HI. Durable Viral Suppression and Transmission Risk Potential among Persons with Diagnosed HIV Infection: United States, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irvine MK, Chamberlin SA, Robbins RS, Kulkarni SG, Robertson MM, Nash D. Come as You Are: Improving Care Engagement and Viral Load Suppression Among HIV Care Coordination Clients with Lower Mental Health Functioning, Unstable Housing, and Hard Drug Use. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1572–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irvine MK, Chamberlin SA, Robbins RS, et al. Improvements in HIV care engagement and viral load suppression following enrollment in a comprehensive HIV care coordination program. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(2):298–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2016. 2017; https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/hiv-surveillance-annualreport-2016.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2018.

- 10.Hanna DB, Felsen UR, Ginsberg MS, et al. Increased Antiretroviral Therapy Use and Virologic Suppression in the Bronx in the Context of Multiple HIV Prevention Strategies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;32(10–11):955–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV surveillance annual report, 2014. 2015; https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/2014-hiv-surveillance-annual-report.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 12.Robertson MM, Waldron L, Robbins RS, et al. Using registry data to construct a comparison group for programmatic effectiveness evaluation – the New York City HIV Care Coordination Program. American journal of epidemiology. in press, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV Care Coordination. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/aids-hiv-care-coord.page. Accessed August 14, 2017.

- 14.Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention. HIV care coordination program: evidence-informed for retention in care. 2015; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research/interventionresearch/compendium/cdc-hiv-hivccp_ei_retention.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2018.

- 15.HIV Testing and Counseling. Amendment to New York State Public Health Law Article 21, Amendment of Part 63 of Title 10, Codes, Rules and Regulations of the State of New York (HIV/AIDS Testing, Reporting and Confidentiality of HIV-Related Information), Chapter 308(2010).

- 16.Marks G, Gardner LI, Rose CE, et al. Time above 1500 copies: a viral load measure for assessing transmission risk of HIV-positive patients in care. AIDS. 2015;29(8):947–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV surveillance annual report, 2013. 2014; https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/2014-hiv-surveillance-annual-report.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 18.Nash D, Robertson M, Penrose K, et al. Short-term effectiveness of HIV care coordination among persons with recent HIV diagnosis or history of poor HIV outcomes. bioRxiv. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bavinton B, Grinsztejn B, Phanuphak N, et al. HIV treatment prevents HIV transmission in male serodiscordant couples in Australia, Thailand and Brazil. 2017; http://programme.ias2017.org/Abstract/Abstract/5469. Accessed September 25, 2017.

- 20.Risher KA, Kapoor S, Daramola AM, et al. Challenges in the Evaluation of Interventions to Improve Engagement Along the HIV Care Continuum in the United States: A Systematic Review. AIDS and Behavior. 2017:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005;19(4):423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardner LI, Giordano TP, Marks G, et al. Enhanced personal contact with HIV patients improves retention in primary care: a randomized trial in 6 US HIV clinics. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(5):725–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CE, et al. Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willis S, Castel AD, Ahmed T, Olejemeh C, Frison L, Kharfen M. Linkage, engagement, and viral suppression rates among HIV-infected persons receiving care at medical case management programs in Washington, DC. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2013;64 Suppl 1:S33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udeagu C-CN, Webster TR, Bocour A, Michel P, Shepard CW. Lost or just not following up: public health effort to re-engage HIV-infected persons lost to follow-up into HIV medical care. Aids. 2013;27(14):2271–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia Q, Braunstein SL, Wiewel EW, Eavey JJ, Shepard CW, Torian LV. Persons Living With HIV in the United States: Fewer Than We Thought. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2016;72(5):552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia Q, Kersanske LS, Wiewel EW, Braunstein SL, Shepard CW, Torian LV. Proportions of patients with HIV retained in care and virally suppressed in New York City and the United States: higher than we thought. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;68(3):351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buskin SE, Kent JB, Dombrowski JC, Golden MR. Migration distorts surveillance estimates of engagement in care: results of public health investigations of persons who appear to be out of HIV care. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2014;41(1):35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dombrowski JC, Buskin SE, Bennett A, Thiede H, Golden MR. Use of multiple data sources and individual case investigation to refine surveillance-based estimates of the HIV care continuum. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2014;67(3):323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buskin SE, Barash EA, Bauer AL, Kent JB, Garcia-Smith HR, Wood RW. HIV infected individuals presumed to not be receiving HIV medical care: a surveillance program evaluation for investigations and referrals in Seattle, Washington State, USA. jHASE-Journal of HIV/AIDS Surveillance & Epidemiology. 2011;3(1). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchacz K, Chen MJ, Parisi MK, et al. Using HIV surveillance registry data to re-link persons to care: the RSVP Project in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.