Abstract

Macropinocytosis is an actin-dependent endocytic mechanism mediating internalization of extracellular fluid and associated solutes into cells. The present study was designed to identify the specific protein kinase C (PKC) isoform(s) and downstream effectors regulating actin dynamics during macropinocytosis. We utilized various cellular and molecular biology techniques, pharmacological inhibitors and genetically modified mice to study the signaling mechanisms mediating macropinocytosis in macrophages. The qRT-PCR experiments identified PKCδ as the predominant PKC isoform in macrophages. Scanning electron microscopy and flow cytometry analysis of FITC-dextran internalization demonstrated the functional role of PKCδ in phorbol ester- and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced macropinocytosis. Western blot analysis demonstrated that phorbol ester and HGF stimulate activation of slingshot phosphatase homologue 1 (SSH1) and induce cofilin Ser-3 dephosphorylation via PKCδ in macrophages. Silencing of SSH1 inhibited cofilin dephosphorylation and macropinocytosis stimulation. Interestingly, we also found that incubation of macrophages with BMS-5, a potent inhibitor of LIM kinase, does not stimulate macropinocytosis. In conclusion, the findings of the present study demonstrate a previously unidentified mechanism by which PKCδ via activation of SSH1 and cofilin dephosphorylation stimulates membrane ruffle formation and macropinocytosis. The results of the present study may contribute to a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms during macrophage macropinocytosis.

Keywords: Macropinocytosis, Macrophages, Protein kinase C, SSH1, Cofilin, Actin remodeling

Introduction

Macropinocytosis (also known as fluid-phase endocytosis) is a highly conserved endocytic process utilized by various cell types to internalize large amount of extracellular fluid and pericellular solutes (1, 2). Macropinocytosis is a receptor-independent process that mediates non-specific internalization of extracellular molecules. Macropinocytosis is initiated by submembranous activation of the actin cytoskeleton, leading to formation of plasma membrane ruffles on the dorsal surface of the cell or the cellular periphery. Some of the membrane ruffles circularize and close, while others fuse with the non-extended plasma membrane, leading to macropinosome formation and fluid/solute internalization (3–5). Macropinocytosis is exploited by dendritic cells to sample their surroundings for antigens, utilized for nutrient uptake by cancerous cells, and assists various viruses and bacteria to invade host cells (3). Previous studies reported that membrane ruffle formation and macropinocytosis can be induced by growth factors, including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (6, 7) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (8) inflammatory cytokines (9, 10), and phorbol esters (10, 11). Increased rate of macropinocytosis is involved in pathological processes, including tumor growth (12, 13), neurodegenerative disorders (14), and infectious diseases (15, 16).

Our knowledge of the mechanisms regulating macropinocytosis has significantly increased in recent years (3–5, 17, 18). Spatiotemporal organization of phosphatidylinositol (PI) modifications by PI 3-kinase (PI3K) and PI 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PI4P5K) play an important role in membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis (17, 19, 20). Phospholipase C-γ (PLCγ)-mediated hydrolysis of PI 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) and subsequent DAG-mediated PKC activation contribute to cup formation and closure, respectively (1, 20, 21). Phorbol ester- and growth factor-stimulated macropinocytosis is blocked by pharmacological inhibition of PKC (7, 21) and macropinocytotic internalization is stimulated by PKC activators (22). The PKC family has been categorized into three groups: i) classical (α, β and γ), ii) novel (δ, ε, η and θ), and iii) atypical (λ, ι, μ and ζ) PKC isoforms. Classical PKCs are DAG/Ca2+-dependent, novel PKCs are DAG-dependent, and atypical PKC isoforms are independent of DAG and calcium ions. PKC isoforms have different mechanisms of activation, substrate specificity and activate various downstream signaling pathways (23–25). The specific PKC isoform(s) mediating macrophage macropinocytosis and the downstream signaling mechanisms remain incompletely characterized.

Macropinocytosis is an actin-dependent process, which is demonstrated by its sensitivity to actin polymerization inhibitors, such as latrunculin A and cytochalasin D (10, 26, 27). Cofilin is an actin-binding protein that severs filaments and accelerates actin assembly dynamics by increasing the number of free barbed ends and ARP2/3 complex-mediated actin branching (28). A previous study by our laboratory demonstrated that deletion of cofilin inhibits phorbol ester-and growth factor-stimulated macropinocytosis (10). Cofilin activity is regulated by its phosphorylation at Ser‐3 residue. Cofilin Ser-3 is phosphorylated (inactivation) by LIM‐kinases (LIMKs) and testicular protein kinases (TESKs) (29–31) and is dephosphorylated (reactivation) by slingshot protein phosphatases (SSHs) (32, 33). SSH1 has been reported to accumulate in membrane protrusions and mediate actin remodeling in motile cells (34). Furthermore, SSH1 is downstream of PI3K, which is an essential mediator of macropinocytosis (35, 36). To our knowledge, no prior studies have investigated the role of SSH1/LIMK pathway in macropinocytosis stimulation.

The present study demonstrates the role of a previously unknown mechanism by which PMA via PKCδ-mediated SSH1 activation stimulates Ser-3 dephosphorylation of cofilin in macrophages, leading to membrane ruffling and fluid-phase macropinocytosis. The role of PKCδ/SSH1/cofilin signaling pathway in macrophage macropinocytosis induced by a physiologically relevant stimuli (hepatocyte growth factor) has been confirmed using various cellular and molecular biology techniques, genetic knockout mice, gene-silencing, and pharmacological approaches. Interestingly, we also found that pharmacological inhibition of LIMK does not stimulate macropinocytosis. The results of the present study may contribute to a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms during macrophage macropinocytosis.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Mouse recombinant macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) was purchased from Miltenyi Biotec Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Recombinant murine hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) was obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Calphostin C, 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets were bought from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). LY333531 and BMS-5 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Phospho-PKCδ (Tyr-311), and phospho-cofilin (Ser-3) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Total PKCδ, total LIMK1, total cofilin, total SSH1, Met, anti-GAPDH and anti-β-actin antibodies were procured from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Phospho-SSH1 (Ser-978) was purchased from ECM Biosciences LLC (Versailles, KY, USA). Phospho-LIMK1 (Thr-508) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 macrophages (ATCC TIB-71™, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C. For bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM), the femur and tibia of sacrificed mice were cleaned of adherent muscle and connective soft tissue and bone marrows were flushed into a 100 mm culture plate using a 27-gauge needle syringe filled with Harvest Buffer [2% heat-inactivated FBS in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)]. Bone marrow-derived monocytes were plated in complete RPMI-1640 culture medium and differentiated into macrophages with M-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 7 days (10). After 7 days, adherent cells were trypsinized and seeded in new cell culture plates or coverslips in complete culture medium without M-CSF. Cells were used for experiments after overnight incubation.

Animals

Eight to ten weeks old male mice were used for obtaining bone marrow-derived macrophages. Dr. Zheng Dong (Augusta University, USA) kindly provided the breeding pairs of PKCδ+/− mice, which were crossed to generate PKCδ−/− and PKCδ+/+ mice. C57BL/6 (wild type) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). Mice were housed at constant temperature (21– 23 °C) and provided ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Mice were anesthetized with 3–5% isoflurane inhalation and sacrificed by cervical dislocation and exsanguinated. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Augusta University and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Flow cytometry

RAW 264.7 macrophages or BMDM were treated with vehicle or PMA (1 μM) in the presence of FITC-dextran (70,000 MW, 100 μg/mL) for 2 hours. In separate experiments, macrophages were treated with or without murine HGF or M-CSF (100 ng/mL, 2 hrs) and FITC-dextran internalization was determined. After incubation time, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA), resuspended in FACS buffer (2% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide in PBS) and analyzed for FITC-dextran uptake (Ex: 488 nm, Em: 530 nm) using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. Mean fluorescence intensity was used to compare FITC-dextran internalization among groups.

Scanning electron microscopy

Macrophages grown on coverslips were treated as indicated and processed for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a method described previously (37). Briefly, cells were fixed in SEM fixative (4% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate solution) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (25%−100%) and critical point drying was performed (Tousimis Samdri-790, Rockville, MD, USA). Coverslips were mounted onto aluminum stubs, sputter coated with 3.5 nm of gold/palladium (Anatek USA-Hummer, Union City, CA) and imaged at 20 KV using a Philips XL30 scanning electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Real Time PCR

The RNA purification kit from IBI Scientific (Peosta, IA, USA) was employed to extract total RNA from cultured macrophages. TaqMan® Reverse Transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from 500 ng of RNA, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantitative real-time PCR was done using SYBR Green Supermix (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH was taken as internal control and ΔΔCt method was used to determine expression. The primer sequences used for real-time PCR are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

List of primers used for mRNA quantitation using real-time-PCR.

| Gene name | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| PKCα | F 5’-CCCATTCCAGAAGGAGATGA-3’ R 5’-TTCCTGTCAGCAAGCATCAC-3’ |

| PKCβ | F 5’-TCCCTGATCCCAAAAGTGAG-3’ R 5’-AACTTGAACCAGCCATCCAC-3’ |

| PKCγ | F 5’-ACCAGGGCATCATCTACAGG-3’ R 5’-CTTCCTCATCTTCCCCATCA-3’ |

| PKCδ | F 5’-CAGACCAAGGACCACCTGTT-3’ R 5’-GCATAAAACGTAGCCCGGTA-3’ |

| PKCε | F 5’-GAGGACTGGATTGACCTGGA-3’ R 5’-ATCTCTGCAGTGGGAGCAGT-3’ |

| PKCη | F 5’-CATCCCACACAAGTTCAACG-3’ R 5’-ATATTTCCGGGTTGGAGACC-3’ |

| PKCθ | F 5’-ATGGACAACCCCTTCTACCC-3’ R 5’-GCGGATGTCTCCTCTCACTC-3’ |

| GAPDH | F 5’-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3’ R 5’-GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA −3’ |

Western blot

Cell lysates were subjected to western blotting as described previously using the Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) (37). Briefly, protein concentrations in cell lysates were quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal amount of proteins (30 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Li-Cor Biosciences). The membranes were blocked and probed with the following primary antibodies: phospho-PKCδ (Tyr-311), total PKCδ, phospho-SSH1 (Ser-978), total SSH1, phospho-cofilin (Ser-3), total cofilin, phospho-LIMK1 (Thr-508), total LIMK1, β-actin and GAPDH. The IRDye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences) were utilized to detect the primary antibodies bound to membranes.

Gene silencing

Smart pool of siRNA for SSH1 and a non-targeting control siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). PKCδ-specific siRNA pool was procured from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. RAW 264.7 macrophages were transfected with PKCδ-siRNA, SSH1-siRNA or control siRNA using the TransIT-TKO transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene silencing using siRNA was confirmed either by Western blot or qRT-PCR. Cells were used 48 hrs post transfection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA). The data are expressed as mean ± SD/SEM. Student’s t-test and one or two-way ANOVA were used as appropriate for the particular experiment and treatment groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PKCδ activation plays a key role in phorbol ester-stimulated macropinocytosis

Previous studies demonstrated that pharmacological blockade of PKC inhibits macropinocytosis in macrophages and other cell types (7, 10, 21). Despite this information, the specific PKC isoform(s) and downstream signaling pathway involved in stimulation of macropinocytosis remain largely uncharacterized. As internalization of extracellular fluid and associated solute is characteristic of macropinocytosis, we used FITC-dextran (70000 MW, 100 μg/mL) as a fluorescent probe to study macropinocytosis (38). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis demonstrated that PMA treatment (1 µM, 2 hrs) induced internalization of FITC-dextran in RAW 264.7 macrophages compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 1A and 1B). Pretreatment of macrophages with the macropinocytosis inhibitor EIPA (25 μM, 30 min) completely blocked PMA-induced FITC-dextran internalization (Fig. 1A and 1B). Scanning electron microscopy shows that PMA treatment stimulated membrane ruffle formation, a necessary first step leading to macropinocytosis [Fig. 1F, PKCδ+/+ (WT), yellow arrows]. As shown in Fig. 1C, pretreatment of macrophages with calphostin C (1 μM, 30 min), a pharmacological inhibitor of classical and novel PKC isoforms (10, 21, 39), completely abolished PMA-induced FITC-dextran macropinocytosis. To determine the specific PKC isoform(s) involved in PMA-induced macropinocytosis, we first investigated the mRNA expression of classical (α, β, and γ) and novel (δ, ε, η, and θ) PKC isoforms in wild type (WT, C57BL/6J) bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) using qRT-PCR. The results of qRT-PCR experiments identified PKCδ, a DAG-dependent novel PKC isozyme, as the dominant PKC isoform in BMDM followed by PKCβ and PKCη expression (Fig. 1D). As PKCδ activity is controlled by tyrosine residue phosphorylation at position 311 (40), we investigated whether PMA treatment induces phosphorylation of PKCδ at Tyr-311 in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Western blot data indicated phosphorylation of PKCδ 5 min after PMA (1 μM) stimulation (Fig. 1E). To investigate the role of PKCδ in macrophage macropinocytosis, BMDM from PKCδ+/+ controls and PKCδ−/− mice were treated with PMA for 30 min and SEM imaging was used to quantify membrane ruffle formation. As shown in Fig. 1F and 1G, PMA treatment stimulated ruffle formation in PKCδ+/+ BMDM, but not in PKCδ−/− BMDM. The genotype of mice was established by PCR analysis of genomic DNA as shown previously (7). Consistent with the SEM data, FACS analysis demonstrated that FITC-dextran internalization following PMA treatment is significantly decreased in PKCδ−/− BMDM compared to PKCδ+/+ controls (Fig. 1H and 1I). Since deletion of PKCδ attenuated (~55%), but not completely abolished PMA-stimulated macropinocytosis in BMDM, we determined compensatory changes in other PKC isoforms in PKCδ knockout BMDM. The qRT-PCR data revealed compensatory upregulation of PKCβ in PKCδ−/− macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 1). Next, we investigated the role of PKCβ in macrophage macropinocytosis. Pharmacological inhibition of PKCβ using LY333531 (5 μM, 30 min) (41) pretreatment, did not significantly inhibit FITC-dextran uptake in PKCδ+/+ BMDM, while in PKCδ−/− BMDM, PKCβ inhibition abrogated residual PMA-stimulated macropinocytosis (Fig. 1J). These data suggest that compensatory increase in PKCβ is responsible for residual macropinocytosis in PKCδ−/− macrophages. Taken together, these results suggest that PMA-stimulated macrophage macropinocytosis primarily involves PKCδ activation.

Figure 1. PKCδ activation promotes macropinocytosis in macrophages.

(A & B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with vehicle or EIPA (25 μM) for 30 min and stimulated with PMA (1 μM, 2 hrs) in the presence of FITC-dextran (FITC-Dx, 70,000 MW, 100 μg/mL). At the end of incubation, cells were fixed in 2% PFA, and FITC-Dx internalization was analyzed by a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer (n = 10). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs PMA.(C) RAW 264.7 macrophages were preincubated with vehicle or calphostin C (Cal. C, 1 μM, 30 min), challenged with PMA, and FACS was performed to analyze FITC-Dx uptake as described above (n = 9). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs PMA. (D) Wild type (WT) bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were used to isolate RNA and qRT-PCR was performed for determination of classical and novel PKC isoforms. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The transcript levels were calculated using delta-delta-CT method. Bar graph represents mRNA levels of classical and novel PKC isoforms in comparison to PKCθ (gene with the lowest expression) (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. PKCθ. (E) RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with vehicle or PMA (1 μM) for the indicated time points (2 to 60 min). Cell lysates prepared in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors were subjected to Western blot analysis for phospho-PKCδ (Tyr-311), total PKCδ and GAPDH protein expression. Representative Western blot images are shown. Bar graph represents mean protein levels calculated using densitometric analysis and expressed as a ratio of phospho- to total PKCδ in comparison to vehicle (n = 5). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. control (ctrl). (F) PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM grown on coverslips were treated with PMA for 30 min and cells were processed for SEM imaging. Membrane ruffles (yellow arrows) and circularized C-shaped ruffles (red arrows) were observed on the dorsal surface of PMA-treated macrophages. Scale bar: 10 μm. (G) Bar graph shows quantification of membrane ruffles normalized to total cell number (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs. PKCδ+/+ PMA. (H & I) BMDM from PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− mice were incubated with FITC-Dx (100 μg/mL) with or without PMA (1 μM) for 2 hrs. FITC fluorescence was analyzed using FACS. (H) Representative FITC fluorescence histograms indicating FITC-Dx accumulation in vehicle- and PMA-treated PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM are shown. (I) Bar graph indicates fold change in mean fluorescence intensity in PKCδ+/+ & PKCδ−/− macrophages following incubation with PMA (n = 10). (J) PKCδ+/+ BMDM were pretreated with LY333531 (5 μM, 30 min) and macropinocytosis was stimulated with PMA. FITC-Dx mean fluorescence intensity was analyzed (n = 5). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, #p < 0.05 vs. PKCδ+/+ PMA and $p < 0.05 vs. PKCδ−/− PMA.

PKCδ facilitates cofilin activation during macropinocytosis

Cofilin is a ubiquitous actin-binding protein that regulates the dynamics of actin filament assembly/disassembly in motile cells (28, 42, 43). Dephosphorylated cofilin at Ser-3 severs actin filaments and creates new actin barbed ends for Arp2/3 to amplify local actin polymerization (44). A recent study by our group confirmed the functional role of cofilin in membrane ruffle formation and macropinocytosis (10). The precise mechanisms, however, by which cofilin is activated during macropinocytosis remain unknown. Western blot data from time-course experiments demonstrated that PMA treatment rapidly induces dephosphorylation of cofilin at Ser-3 in WT macrophages, indicating its stimulated activity (Fig. 2A and 2B). In contrast, cofilin dephosphorylation in response to PMA stimulation was significantly attenuated in PKCδ−/−BMDM (Fig. 2C and 2D). Pharmacological inhibition of PKCβ using LY333531 did not inhibit cofilin dephosphorylation following PMA treatment in WT (PKCδ+/+) BMDM (Supplementary Fig. 2). To our knowledge, these findings demonstrate for the first time that PKCδ activation in macrophages mediates Ser-3 dephosphorylation of cofilin, leading to its activation in response to PMA treatment.

Figure 2. PKCδ mediates cofilin activation during macropinocytosis.

(A & B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with vehicle or PMA (1 µM) for various time points (2 to 60 min). Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blotting for phospho- or total cofilin, and GAPDH protein expression. (A) Representative Western blot images are shown. (B) Bar diagram represents averaged protein levels expressed as a ratio of phospho- to total proteins (n = 8). (C & D) PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM were incubated with vehicle or PMA for 30 min and cell lysates were utilized for determination of cofilin activation. (C) Representative Western blot images are shown. (D) Bar graph indicates mean ratio of phospho-cofilin to total cofilin (n = 9). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. control (ctrl)/vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs. PKCδ+/+ PMA.

SSH1 activation is required for macrophage macropinocytosis

The next experiments were designed to investigate the signaling mechanisms downstream of PKCδ activation, leading to cofilin Ser-3 dephosphorylation and macropinocytosis. Cofilin is inactivated by LIM kinase (LIMK) 1-mediated Ser-3 phosphorylation and is reactivated by slingshot phosphatase homolog 1 (SSH1) (29). SSH1 dephosphorylation at Ser-978 stimulates its dissociation from regulatory 14–3-3 proteins, leading to increased SSH1 activity and cofilin activation (45). Western blot results show that incubation of macrophages with PMA dephosphorylates SSH1 at Ser-978 (Fig. 3A and 3B). To examine the role of SSH1 in PMA-stimulated cofilin activation, SSH1 silencing was performed in macrophages using SSH1-specific siRNAs and cofilin activation was analyzed following PMA stimulation. Successful silencing of SSH1 was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 3C). As shown in Fig. 3C and 3D, siRNA-mediated knockdown of SSH1 inhibited PMA-induced cofilin dephosphorylation. Next, we investigated the role of PKCδ in mediating SSH1 activation following PMA treatment using Western blot and observed no induction of SSH1 activation in PKCδ−/− BMDM compared to PKCδ+/+ controls (Fig. 3E and 3F). Furthermore, silencing of SSH1 in RAW 264.7 macrophages inhibited PMA-induced macropinocytosis (Fig. 3G and 3H). These data suggest that PKCδ-mediated SSH1 activation stimulates cofilin dephosphorylation, leading to induction of macropinocytosis in macrophages.

Figure 3. SSH1 activation plays an important role in macrophage macropinocytosiss.

(A &B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with or without PMA (1 µM) for indicated time periods. Western blot images (A) and bar diagram (B) show activation of SSH1 following PMA treatment as indicated by its dephosphorylation at Ser-978 (n = 9). (C & D) Control (Ctrl) and SSH1-siRNA transfected RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with vehicle or PMA (30 min) and Western blot performed to investigate cofilin activation as described in Fig. 2. Silencing of SSH1 was confirmed via determination of total SSH1 protein levels. (C) Representative Western blot images are shown. (D) Bar graph shows Ser-3 phosphorylation of cofilin in control and SSH1-silenced macrophages following PMA treatment (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs. control PMA. (E & F) PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM were treated as described in Fig. 2C and SSH1 activation was investigated using Western blot. (E) Representative Western blot images are shown. (F) Bar graph indicates mean ratio of phospho-SSH1 to total SSH1 (n = 7). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs. PKCδ+/+ PMA. (G) Control and SSH1-silenced RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with FITC-dextran, treated with vehicle or PMA (2 hrs) and FACS was performed. Silencing of SSH1 was confirmed with Western blot (inset). Representative histograms indicating FITC-Dx internalization in vehicle- and PMA-treated cells are shown. (H) Bar graph indicates fold change in mean fluorescence intensity in control and SSH1-silenced macrophages following PMA stimulation (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs. control PMA.

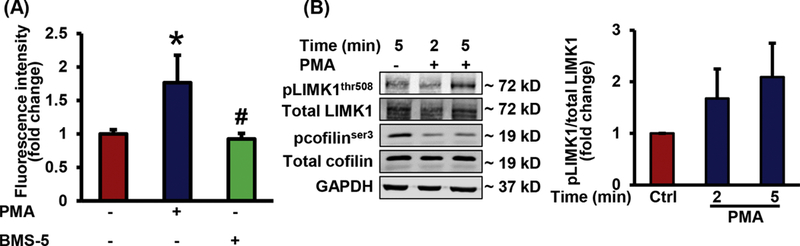

Inhibition of LIMK1 does not stimulate macrophage macropinocytosis

LIMK1 directly phosphorylates and inactivates cofilin, resulting in stabilization of filamentous actin and inhibition of lamellipodium formation (29, 30). Next, we investigated whether inhibition of LIMK1 activity stimulates macropinocytosis. Interestingly, we found that incubation of macrophages with BMS-5, a potent inhibitor of LIMK (46), does not stimulate FITC-dextran internalization (Fig. 4A). Phosphorylation of LIMK on the threonine residue 508 stimulates its cofilin phosphorylating activity (47). As shown in Fig. 4B, no significant (p = 0.265 and 0.125 for 2 and 5 min treatment) changes in LIMK1 Thr-508 phosphorylation in response to PMA treatment was observed. These results suggest that a) stimulation of cofilin phosphatase activity is sufficient to induce macropinocytosis and b) alternative cofilin kinases (other than LIMK) may be involved in the regulation of macrophage macropinocytosis.

Figure 4. Pharmacological inhibition of LIMK does not stimulate macrophage macropinocytosis.

(A) RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with vehicle, PMA, or BMS-5 in the presence of FITC-Dx. FITC fluorescence was analyzed using FACS (n = 6). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs PMA. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with vehicle or PMA (1 µM) for indicated time periods and phosphorylation of LIMK1 and cofilin was determined using Western blot. Bar diagram shows phosphorylated LIMK1 expression normalized to total LIMK1 protein (n = 6). Data represent the mean ± SEM.

Hepatocyte growth factor-stimulated macropinocytosis involves PKCδ and SSH1 activation

To investigate the physiological importance of PKCδ in macrophage macropinocytosis, BMDM from PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− mice were incubated with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), a physiologically relevant stimulator of macropinocytosis (6, 7), and FITC-dextran internalization analyzed by FACS analysis. Supplementary data demonstrate that the HGF receptor Met is expressed in PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− macrophages and Raw 264.7 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3A and 3B). HGF treatment (100 ng/ml, 2 hrs) significantly stimulated FITC-dextran internalization in RAW macrophages compared to vehicle control (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment of macrophages with EIPA (25 μM, 30 min) abolished HGF-induced FITC-dextran internalization, which is in compliance with previous findings that HGF stimulates macropinocytosis (6, 7). Protein kinase C inhibitor calphostin C (1 μM, 30 min) inhibited HGF-induced FITC-dextran internalization, confirming the role of PKC in HGF-induced macropinocytosis (Fig. 5B). Western blot data indicated that HGF treatment leads to dephosphorylation of cofilin and SSH-1 in PKCδ+/+ BMDM, however, no stimulated activation was observed in PKCδ−/− BMDM (Fig. 5C and 5D). Next, PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM were treated with HGF or vehicle, incubated with FITC-dextran and macropinocytosis determined. FACS analysis revealed induction of macropinocytosis in response to HGF in PKCδ+/+ BMDM, but not in PKCδ−/− BMDM (Fig. 5E). Finally, as shown in Fig. 5F, siRNA knockdown of SSH1 in RAW 264.7 macrophages completely eliminated HGF-stimulated macropinocytosis. Taken together, these results suggest that the PKCδ-SSH1-cofilin signaling pathway plays an important role in growth factor-stimulated macrophage macropinocytosis.

Figure 5. Physiological stimulation of macropinocytosis by HGF involves PKCδ and SSH1 activation.

(A & B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with vehicle or EIPA (25 μM) (A) or calphostin C (Cal. C, 1 μM) (B) for 30 min and stimulated with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF, 100 ng/mL, 2 hrs) in the presence of FITC-dx (100 μg/mL). Cells were fixed in 2% PFA, and FITC-Dx internalization was analyzed by FACS (n = 6). (C & D) PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/−BMDM were treated with vehicle or HGF for 15 min and Western blotting was performed. (C) Representative Western blot images are shown. (D) Bar diagrams indicate mean ratio of phospho-cofilin to total cofilin and phospho-SSH1 to total SSH1 (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs PKCδ+/+ HGF. (E) Bar diagram shows FITC-Dx internalization in PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM in response to HGF treatment (100 ng/mL, 2 hrs) using FACS (n = 6). (F) Control and SSH1-silenced RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with vehicle or HGF (2 hrs) in the presence of FITC-Dx and FACS was performed. Bar diagram shows fold change in mean fluorescence intensity in control and SSH1-silenced macrophages (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, and #p < 0.05 vs PKCδ+/+/control siRNA HGF.

PKCδ, but not SSH1 activation, mediates M-CSF-stimulated macropinocytosis

M-CSF is a widely used stimulator of macropinocytosis in macrophages (10, 21, 48, 49). Therefore, we also examined the role of PKCδ, SSH1, LIMK, and cofilin in M-CSF-stimulated macropinocytosis. Time-course Western blot experiments were performed to investigate the phosphorylation status of PKCδ, SSH1, LIMK1, and cofilin in vehicle- and M-CSF treated (100 ng/mL) cells. Our results confirmed that M-CSF stimulates PKCδ phosphorylation (Fig. 6A and 6B) and induces cofilin activation (Fig. 6A and 6C) in macrophages. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6G, M-CSF-stimulated macropinocytosis was significantly reduced in PKCδ−/− BMDM compared to PKCδ+/+ controls. Interestingly, we found that M-CSF treatment did not induce changes in SSH1 (Fig. 6A and 6D) and LIMK1 (Fig. 6E and 6F) phosphorylation. These results suggest that M-CSF-stimulated macropinocytosis is mediated by PKCδ, but not SSH1 and LIMK1.

Figure 6. PKCδ and cofilin but not SSH1 activation plays role in M-CSF-stimulated macropinocytosis.

(A) RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with or without M-CSF (100 ng/mL) for 2 to 60 min and cell lysates were used for Western blot to investigate phosphorylation levels of PKCδ, SSH1, cofilin and β-actin protein expression. Representative Western blot images are shown. (B-D) Bar graphs indicate averaged protein levels expressed as a ratio of phospho- to total PKCδ (B), phospho- to total cofilin (C) and phospho- to total SSH1 (D) (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle. (E & F) Raw macrophages were treated as in Fig. 6A and phosphorylation of LIMK1 was determined. Representative Western blot images are shown (E). (F) Bar graph indicates averaged protein levels expressed as a ratio of phospho- to total LIMK1. Data represent the mean ± SEM.. (G) Bar diagram shows FITC-Dx internalization in PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− BMDM following M-CSF stimulation (100 ng/mL, 2 hrs) using FACS (n = 5). Data represent the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle, #p < 0.05 vs. PKCδ+/+ M-CSF.

Discussion

The findings of the present study demonstrate a previously unidentified mechanism by which PKCδ via downstream activation of SSH1-cofilin signaling stimulates macrophage macropinocytosis. Although our understanding of the signaling mechanisms involved in macropinocytosis has advanced significantly in the last decade (3, 21, 37), the precise signaling pathways responsible for initiation of macropinocytosis and macropinosome formation remain incompletely understood. In the present study, we demonstrated that macropinocytosis stimulators, PMA and HGF, induce activation of SSH1-cofilin pathway via PKCδ and PMA/HGF-induced macrophage macropinocytosis is dependent on PKCδ and SSH1 activation. Interestingly, we found that inhibition of cofilin kinase, LIMK does not stimulate macrophage macropinocytosis. These results may contribute to a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms during macropinocytosis.

Previous studies by our lab and others demonstrated that DAG-induced PKC activation in macrophages stimulates macropinocytosis (10, 22). Growth factors have been shown to activate DAG-dependent PKCs, induce peripheral actin remodeling and stimulate macropinocytosis (6, 8, 50). However, the specific PKC isoform(s) and downstream effectors mediating macrophage macropinocytosis are incompletely defined. Thus, the present study was designed to identify the PKC isoform(s) and downstream mechanisms responsible for macropinocytosis stimulation. The PKC family consists of three groups, namely classical (α, β and γ), novel (δ, ε, η and θ), and atypical PKC isoforms (λ, ι, μ and ζ), which differ in their structure, mechanisms of activation and cofactor requirements (51, 52). Classical PKC isoforms are activated by DAG and calcium ions, novel PKCs can be activated by DAG only as they do not bind calcium (53), and atypical PKCs are DAG/calcium-independent enzymes. We first confirmed the role of classical and/or novel PKCs in PMA- and HGF-stimulated macrophage macropinocytosis by using a pharmacological inhibitor of DAG-dependent PKC isoforms, calphostin C. The qRT-PCR analysis revealed PKCδ as the major PKC isoform in macrophages (PKCδ>PKCβ>PKCη) (54). Next, we investigated the role of PKCδ in ruffle formation and macropinocytosis. Scanning electron microscopy imaging and FACS data demonstrated that loss of PKCδ in BMDM inhibits PMA-induced ruffle formation and macropinocytosis (~55%). Compensatory upregulation of PKCβ in PKCδ knockout macrophages was demonstrated by qRT-PCR. Interestingly, pharmacological inhibition of PKCβ did not inhibit PMA-induced macropinocytosis in wild-type macrophages, but led to complete inhibition of macropinocytosis in PKCδ knockout macrophages. These results suggest that PKCδ is the major PKC isozyme involved in PMA-induced macrophage macropinocytosis and PKCβ may compensate its role in PKCδ knockout cells. Previous studies showed that pharmacological inhibition of PKCδ with rottlerin inhibits virus-induced macropinocytosis in endothelial cells (55) and attenuates macropinocytic uptake of parasites in macrophages (56). However, as the selectivity of rottlerin for PKCδ is questionable, the role of PKCδ in these studies remain elusive (57–59). Interestingly, previous studies also suggest a role for PKCα and PKCγ in macrophage (M-CSF-stimulated) and cancer cell (phorbol ester-stimulated) macropinocytosis, respectively (20, 60). Contrary to our observations, Ma et al demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of PKCβ inhibits PMA-stimulated cholesterol macropinocytosis by 55% (61). We speculate that these differences may be due to the different cell types used to study macropinocytosis, different PKC isoform expression, stage of macropinocytosis studied, and differences in the mechanisms of macropinocytosis induction.

Cofilin is an actin-binding protein that regulates actin filament dynamics (43, 62). Dephosphorylated cofilin at Ser-3 severs actin filaments and creates new actin barbed ends for Arp2/3 to rebuild the actin network and simulate formation of membrane protrusions. A previous study by our group demonstrated that silencing of cofilin inhibits PMA- and growth factor-induced membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis in macrophages (10). Recently, Zhong et al., using pharmacological and genetic approaches have shown an important role for cofilin and actin polymerization in macropinocytic entry of prion-like protein aggregates in neuroblasts (63). The results of the present study demonstrated that PMA and HGF treatments dephosphorylate cofilin at Ser-3 in wild-type macrophages and activation of cofilin is significantly attenuated in PKCδ knockout macrophages. These results indicate the role of PKCδ in phorbol ester- and growth factor-induced cofilin activation. In line with this observation, Oh et al. demonstrated the role of PKCδ in cofilin activation, leading to peripheral actin reorganization in rat intestinal epithelial cells (64). Furthermore, Djafarzadeh et al. reported the involvement of Ca2+-independent PKC isoforms (novel) in PMA-induced cofilin dephosphorylation in human neutrophils (65). Consistent with previous studies (10, 21), our results demonstrated that M-CSF activates PKCδ and stimulates cofilin dephosphorylation in macrophages. Our FACS results showed that M-CSF-induced macropinocytosis is significantly attenuated in PKCδ knockout macrophages.

The slingshot family of phosphatases dephosphorylate and therefore activate cofilin (66). SSH1 activity is regulated by dephosphorylation at Ser-978 as phosphorylation at this position generates a binding site for regulatory 14–3-3 proteins (67, 68). Once released from 14–3-3, SSH1 translocates to the leading edge of cells to activate cofilin and induce actin remodeling (69). Therefore, we next determined the phosphorylation status of SSH1 at Ser-978 in response to macropinocytosis stimulators. Our results demonstrated that PMA and HGF dephosphorylate SSH1 at Ser-978 in macrophages via PKCδ activation. Additionally, siRNA silencing of SSH1 inhibited cofilin dephosphorylation and macropinocytosis in response to PMA and HGF treatments. Noteworthy, we found significant SSH1 activation after 15 min of PMA treatment, while cofilin was activated as early as 2 min. It is tempting to speculate that dephosphorylation of other SSH1 residues may occur at earlier time-points, leading to increased SSH1 activity and cofilin dephosphorylation. Indeed, SSH1 dephosphorylation at Ser-402 and Ser-937 have been reported to stimulate SSH1 activity (70, 71). SSH1-independent activation of cofilin at these early time-points can also contribute to macropinocytosis stimulation. The mechanisms by which PKCδ activates SSH1 is currently unknown. Interestingly, previous studies showed that NAPDH oxidase (Nox)-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) release SSH1 from the inhibitory interaction with 14–3-3 proteins, leading to cofilin dephosphorylation and actin cytoskeleton reorganization (72). PKCδ activation in phagocytes stimulates phosphorylation of the Nox organizer subunit p47phox, leading to Nox2 assembly and ROS generation (73). A previous study by our lab demonstrated stimulation of macropinocytosis via Nox2 activation in macrophages (10). Based on these results and our current study, we propose that PKCδ-mediated Nox2 activation in macrophages contributes to the release of SSH1 from the inhibitory interaction with 14–3-3, leading to cofilin activation and macropinocytosis. This conception is supported by previous observations showing that PI3K, an upstream mediator of Nox enzymes and macropinocytosis, dephosphorylates cofilin via SSH1 activation (74). It is also possible that PKCδ via MAPK regulates SSH1 activation as PKC has been shown to control MAPK activity (75, 76).

The results of the present study also demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of the cofilin kinase LIMK in macrophages does not stimulate macropinocytosis. Also, stimulators of macropinocytosis did not change LIMK phosphorylation in macrophages. These findings indicate that stimulation of cofilin phosphatase activity is sufficient to induce macropinocytosis and/or alternative cofilin kinases [i.e., TES kinase (31)] are involved in the regulation of macrophage macropinocytosis.

M-CSF is one of the most widely used physiological stimulators of macropinocytosis (10, 20, 21). In contrast to phorbol ester and HGF treatments, we observed no stimulation of SSH1 activity in response to M-CSF treatment. As M-CSF rapidly (< 2 min) dephosphorylated cofilin at Ser-3 in macrophages, these results suggest an alternative, SSH1-independent mode of cofilin activation mechanisms by M-CSF, leading to macropinocytosis.

In conclusion, our findings show that PKCδ, SSH1 and cofilin are signaling partners that mediate macropinocytosis in response to phorbol ester and growth factor stimulation. These findings provide a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of macropinocytosis and expected to have important implications in the field of endocytosis and pathological conditions involving macropinocytosis.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7. Schematic model of signaling events occurring during PMA/HGF-induced macropinocytosis in macrophages.

Treatment with PMA/HGF in macrophages stimulates PKCδ phosphorylation (activation) which, in turn, induces activation of SSH1 and causes cofilin dephosphorylation essential for actin rearrangement. This dynamic peripheral actin reorganization leads to membrane ruffle formation and macropinocytosis.

Highlights.

Deletion of PKCδ in macrophages attenuates membrane ruffle formation and macropinocytosis induced by macropinocytosis stimulators.

Hepatocyte growth factor and phorbol ester stimulate SSH1 and cofilin activation via PKCδ-mediated mechanisms.

Silencing of SSH1 inhibits cofilin activation and macropinocytosis.

Pharmacological inhibition of LIMK does not stimulate macropinocytosis.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Jeanene Pihkala and Libby Perry (Augusta University) for their help with the FACS analysis and SEM sample preparation, respectively. This research work was financially supported by National Institutes of Health grants (1R01HL139562-01A1, K99HL114648 and R00HL114648-03) awarded to GC and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (17POST33661254) given to BS.

Abbreviations

- PMA

Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate

- M-CSF

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- EIPA

5-(N-Ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- FITC-Dx

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate-dextran

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- BMDM

Bone marrow-derived macrophage

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscopy

- SSH

Slingshot protein phosphatase

- LIMK

LIM domain kinase

- TESK

Testis-specific protein kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be taken as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bloomfield G, Kay RR. Uses and abuses of macropinocytosis. J Cell Sci 2016;129(14):2697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem 2009;78:857–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercer J, Helenius A. Virus entry by macropinocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 2009;11(5):510–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim JP, Gleeson PA. Macropinocytosis: an endocytic pathway for internalising large gulps. Immunol Cell Biol 2011;89(8):836–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Roche PA. Macropinocytosis in phagocytes: regulation of MHC class-II-restricted antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Front Physiol 2015;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowrick P, Kenworthy P, McCann B, Warn R. Circular ruffle formation and closure lead to macropinocytosis in hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-treated cells. Eur J Cell Biol 1993;61(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singla B, Ghoshal P, Lin H, Wei Q, Dong Z, Csanyi G. PKCdelta-Mediated Nox2 Activation Promotes Fluid-Phase Pinocytosis of Antigens by Immature Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol 2018;9:537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant DM, Kerr MC, Hammond LA, Joseph SR, Mostov KE, Teasdale RD, et al. EGF induces macropinocytosis and SNX1-modulated recycling of E-cadherin. J Cell Sci 2007;120(Pt 10):1818–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BoseDasgupta S, Moes S, Jenoe P, Pieters J. Cytokine-induced macropinocytosis in macrophages is regulated by 14-3-3zeta through its interaction with serine-phosphorylated coronin 1. FEBS J 2015;282(7):1167–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghoshal P, Singla B, Lin H, Feck DM, Cantu-Medellin N, Kelley EE, et al. Nox2-Mediated PI3K and Cofilin Activation Confers Alternate Redox Control of Macrophage Pinocytosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017;26(16):902–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson JA. Phorbol esters stimulate macropinocytosis and solute flow through macrophages. J Cell Sci 1989;94 ( Pt 1):135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Commisso C, Davidson SM, Soydaner-Azeloglu RG, Parker SJ, Kamphorst JJ, Hackett S, et al. Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature 2013;497(7451):633–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palm W, Park Y, Wright K, Pavlova NN, Tuveson DA, Thompson CB. The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1. Cell 2015;162(2):259–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeineddine R, Yerbury JJ. The role of macropinocytosis in the propagation of protein aggregation associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Front Physiol 2015;6:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aleksandrowicz P, Marzi A, Biedenkopf N, Beimforde N, Becker S, Hoenen T, et al. Ebola virus enters host cells by macropinocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Infect Dis 2011;204 Suppl 3:S957–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan L, Zhang Y, Zhan Y, Yuan Y, Sun Y, Qiu X, et al. Newcastle disease virus employs macropinocytosis and Rab5a-dependent intracellular trafficking to infect DF-1 cells. Oncotarget 2016;7(52):86117–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida S, Pacitto R, Inoki K, Swanson J. Macropinocytosis, mTORC1 and cellular growth control. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018;75(7):1227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckley CM, King JS. Drinking problems: mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation. FEBS J 2017;284(22):3778–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maekawa M, Terasaka S, Mochizuki Y, Kawai K, Ikeda Y, Araki N, et al. Sequential breakdown of 3-phosphorylated phosphoinositides is essential for the completion of macropinocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(11):E978–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welliver TP, Swanson JA. A growth factor signaling cascade confined to circular ruffles in macrophages. Biol Open 2012;1(8):754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida S, Gaeta I, Pacitto R, Krienke L, Alge O, Gregorka B, et al. Differential signaling during macropinocytosis in response to M-CSF and PMA in macrophages. Front Physiol 2015;6:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruth HS, Huang W, Ishii I, Zhang WY. Macrophage foam cell formation with native low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem 2002;277(37):34573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishikawa K, Toker A, Johannes FJ, Songyang Z, Cantley LC. Determination of the specific substrate sequence motifs of protein kinase C isozymes. J Biol Chem 1997;272(2):952–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudan R, Srivastava N, Pandey SP, Majumdar S, Saha B. Reciprocal regulation of protein kinase C isoforms results in differential cellular responsiveness. J Immunol 2012;188(5):2328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong R, Hong AW, Plouffe SW, Zhao B, Liu G, Yu FX, et al. Opposing roles of conventional and novel PKC isoforms in Hippo-YAP pathway regulation. Cell Res 2015;25(8):985–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanlaya R, Sintiprungrat K, Chaiyarit S, Thongboonkerd V. Macropinocytosis is the major mechanism for endocytosis of calcium oxalate crystals into renal tubular cells. Cell Biochem Biophys 2013;67(3):1171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandgren KJ, Wilkinson J, Miranda-Saksena M, McInerney GM, Byth-Wilson K, Robinson PJ, et al. A differential role for macropinocytosis in mediating entry of the two forms of vaccinia virus into dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog 2010;6(4):e1000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Condeelis J How is actin polymerization nucleated in vivo? Trends Cell Biol 2001;11(7):288–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soosairajah J, Maiti S, Wiggan O, Sarmiere P, Moussi N, Sarcevic B, et al. Interplay between components of a novel LIM kinase-slingshot phosphatase complex regulates cofilin. EMBO J 2005;24(3):473–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang TY, DerMardirossian C, Bokoch GM. Cofilin phosphatases and regulation of actin dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2006;18(1):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toshima J, Toshima JY, Takeuchi K, Mori R, Mizuno K. Cofilin phosphorylation and actin reorganization activities of testicular protein kinase 2 and its predominant expression in testicular Sertoli cells. J Biol Chem 2001;276(33):31449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gungabissoon RA, Bamburg JR. Regulation of growth cone actin dynamics by ADF/cofilin. J Histochem Cytochem 2003;51(4):411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres RA, Drake DA, Solodushko V, Jadhav R, Smith E, Rocic P, et al. Slingshot isoform-specific regulation of cofilin-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell migration and neointima formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31(11):2424–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Homma Y, Kanno S, Sasaki K, Nishita M, Yasui A, Asano T, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-4 binds to Slingshot-1 phosphatase and promotes cofilin dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2014;289(38):26302–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kruth HS, Jones NL, Huang W, Zhao B, Ishii I, Chang J, et al. Macropinocytosis is the endocytic pathway that mediates macrophage foam cell formation with native low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem 2005;280(3):2352–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoeller O, Bolourani P, Clark J, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT, Weiner OD, et al. Two distinct functions for PI3-kinases in macropinocytosis. J Cell Sci 2013;126(Pt 18):4296–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Csanyi G, Feck DM, Ghoshal P, Singla B, Lin H, Nagarajan S, et al. CD47 and Nox1 Mediate Dynamic Fluid-Phase Macropinocytosis of Native LDL. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017;26(16):886–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Commisso C, Flinn RJ, Bar-Sagi D. Determining the macropinocytic index of cells through a quantitative image-based assay. Nat Protoc 2014;9(1):182–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen EC, DiGennaro JA, Saito N, Mehta S, Loegering DJ, Mazurkiewicz JE, et al. Differential requirement for classic and novel PKC isoforms in respiratory burst and phagocytosis in RAW 264.7 cells. J Immunol 2000;165(5):2809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rybin VO, Guo J, Harleton E, Feinmark SJ, Steinberg SF. Regulatory autophosphorylation sites on protein kinase C-delta at threonine-141 and threonine-295. Biochemistry 2009;48(21):4642–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koya D, Jirousek MR, Lin YW, Ishii H, Kuboki K, King GL. Characterization of protein kinase C beta isoform activation on the gene expression of transforming growth factor-beta, extracellular matrix components, and prostanoids in the glomeruli of diabetic rats. J Clin Invest 1997;100(1):115–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem 2007;76:593–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh M, Song X, Mouneimne G, Sidani M, Lawrence DS, Condeelis JS. Cofilin promotes actin polymerization and defines the direction of cell motility. Science 2004;304(5671):743–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DesMarais V, Ghosh M, Eddy R, Condeelis J. Cofilin takes the lead. J Cell Sci 2005;118(Pt 1):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bravo-Cordero JJ, Magalhaes MA, Eddy RJ, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. Functions of cofilin in cell locomotion and invasion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013;14(7):405–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrilli A, Copik A, Posadas M, Chang LS, Welling DB, Giovannini M, et al. LIM domain kinases as potential therapeutic targets for neurofibromatosis type 2. Oncogene 2014;33(27):3571–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohashi K, Nagata K, Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Mizuno K. Rho-associated kinase ROCK activates LIM-kinase 1 by phosphorylation at threonine 508 within the activation loop. J Biol Chem 2000;275(5):3577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Araki N, Johnson MT, Swanson JA. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the completion of macropinocytosis and phagocytosis by macrophages. J Cell Biol 1996;135(5):1249–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Racoosin EL, Swanson JA. M-CSF-induced macropinocytosis increases solute endocytosis but not receptor-mediated endocytosis in mouse macrophages. J Cell Sci 1992;102 (Pt 4):867–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reyhani V, Tsioumpekou M, van Wieringen T, Rask L, Lennartsson J, Rubin K. PDGF-BB enhances collagen gel contraction through a PI3K-PLCgamma-PKC-cofilin pathway. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):8924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parker PJ, Murray-Rust J. PKC at a glance. J Cell Sci 2004;117(Pt 2):131–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newton AC. Protein kinase C: poised to signal. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;298(3):E395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinberg SF. Cardiac actions of protein kinase C isoforms. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27(3):130–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Monick MM, Carter AB, Gudmundsson G, Geist LJ, Hunninghake GW. Changes in PKC isoforms in human alveolar macrophages compared with blood monocytes. Am J Physiol 1998;275(2 Pt 1):L389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raghu H, Sharma-Walia N, Veettil MV, Sadagopan S, Chandran B. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus utilizes an actin polymerization-dependent macropinocytic pathway to enter human dermal microvascular endothelial and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Virol 2009;83(10):4895–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barrias ES, Reignault LC, De Souza W, Carvalho TM. Trypanosoma cruzi uses macropinocytosis as an additional entry pathway into mammalian host cell. Microbes Infect 2012;14(14):1340–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soltoff SP. Rottlerin: an inappropriate and ineffective inhibitor of PKCdelta. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2007;28(9):453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J 2000;351(Pt 1):95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gschwendt M, Muller HJ, Kielbassa K, Zang R, Kittstein W, Rincke G, et al. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994;199(1):93–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamamoto K, Seki T, Yamamoto H, Adachi N, Tanaka S, Hide I, et al. Deregulation of the actin cytoskeleton and macropinocytosis in response to phorbol ester by the mutant protein kinase C gamma that causes spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. Front Physiol 2014;5:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma HT, Lin WW, Zhao B, Wu WT, Huang W, Li Y, et al. Protein kinase C beta and delta isoenzymes mediate cholesterol accumulation in PMA-activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;349(1):214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hotulainen P, Paunola E, Vartiainen MK, Lappalainen P. Actin-depolymerizing factor and cofilin-1 play overlapping roles in promoting rapid F-actin depolymerization in mammalian nonmuscle cells. Mol Biol Cell 2005;16(2):649–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhong Z, Grasso L, Sibilla C, Stevens TJ, Barry N, Bertolotti A. Prion-like protein aggregates exploit the RHO GTPase to cofilin-1 signaling pathway to enter cells. EMBO J 2018;37(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oh MA, Kang ES, Lee SA, Lee EO, Kim YB, Kim SH, et al. PKCdelta and cofilin activation affects peripheral actin reorganization and cell-cell contact in cells expressing integrin alpha5 but not its tailless mutant. J Cell Sci 2007;120(Pt 15):2717–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Djafarzadeh S, Niggli V. Signaling pathways involved in dephosphorylation and localization of the actin-binding protein cofilin in stimulated human neutrophils. Exp Cell Res 1997;236(2):427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niwa R, Nagata-Ohashi K, Takeichi M, Mizuno K, Uemura T. Control of actin reorganization by Slingshot, a family of phosphatases that dephosphorylate ADF/cofilin. Cell 2002;108(2):233–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eiseler T, Doppler H, Yan IK, Kitatani K, Mizuno K, Storz P. Protein kinase D1 regulates cofilin-mediated F-actin reorganization and cell motility through slingshot. Nat Cell Biol 2009;11(5):545–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spratley SJ, Bastea LI, Doppler H, Mizuno K, Storz P. Protein kinase D regulates cofilin activity through p21-activated kinase 4. J Biol Chem 2011;286(39):34254–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teng B, Lukasz A, Schiffer M. The ADF/Cofilin-Pathway and Actin Dynamics in Podocyte Injury. Int J Cell Biol 2012;2012:320531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barisic S, Nagel AC, Franz-Wachtel M, Macek B, Preiss A, Link G, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser 402 impedes phosphatase activity of slingshot 1. EMBO Rep 2011;12(6):527–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peterburs P, Heering J, Link G, Pfizenmaier K, Olayioye MA, Hausser A. Protein kinase D regulates cell migration by direct phosphorylation of the cofilin phosphatase slingshot 1 like. Cancer Res 2009;69(14):5634–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim JS, Huang TY, Bokoch GM. Reactive oxygen species regulate a slingshot-cofilin activation pathway. Mol Biol Cell 2009;20(11):2650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bey EA, Xu B, Bhattacharjee A, Oldfield CM, Zhao X, Li Q, et al. Protein kinase C delta is required for p47phox phosphorylation and translocation in activated human monocytes. J Immunol 2004;173(9):5730–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nishita M, Wang Y, Tomizawa C, Suzuki A, Niwa R, Uemura T, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated activation of cofilin phosphatase Slingshot and its role for insulin-induced membrane protrusion. J Biol Chem 2004;279(8):7193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Du XY, Huang J, Xu LQ, Tang DF, Wu L, Zhang LX, et al. The proto-oncogene c-src is involved in primordial follicle activation through the PI3K, PKC and MAPK signaling pathways. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012;10:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 76.Vargas NB, Brewer BY, Rogers TB, Wilson GM. Protein kinase C activation stabilizes LDL receptor mRNA via the JNK pathway in HepG2 cells. J Lipid Res 2009;50(3):386–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.