Abstract

Background:

Serum total cholesterol (TC) levels may be associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk.

Objective:

To evaluate associations between HDL and non-HDL cholesterol levels at specific ages and subsequent AD risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

Prospective population-based cohort study using data from Adult Changes in Thought (ACT). Participants were 65 years or older with no dementia at ACT study entry. We identified separate, partially overlapping, sub-cohorts of ACT participants who were eligible for each age band-specific analysis (50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80–89 years old; n=1088, n=2852, n=2344, n=537, respectively).

Measurements:

Exposure consisted of clinical measures of TC and HDL from laboratory data during a given age band. Outcomes of incident AD assessed post-age band using standard research diagnostic criteria. Statistical analyses used adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models for each exposure and outcome pair within an age band. Cholesterol exposures modeled using cubic splines.

Results:

For non-HDL, we found a statistically significant association with AD risk in the 60–69 (omnibus p=0.005) and 70–79 (omnibus p=0.04) age bands, suggesting a potential U-shaped relationship (increased risk at low and high levels). For example, people age 60–69, compared with a person with an average non-HDL level of 160 mg/dL, a person with an average non-HDL level of 120 mg/DL had a 29% increased AD hazard (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04–1.61), while a person with an average non-HDL level of 210 mg/dL had a 16% increased hazard (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01–1.33). We did not find a statistically significant association for HDL cholesterol and AD risk.

Conclusion:

People with low (120 mg/dL) and high (210 mg/dL) levels of non-HDL cholesterol during their 60s and 70s had modestly higher risk for AD compared to people with intermediate (160 mg/dL) levels of non-HDL cholesterol. The extreme age bands (50s and 80s) were limited in sample size.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, cholesterol

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular risk factors have been increasingly recognized as targets for reducing dementia in late-life, especially late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).1,2 One common modifiable cardiovascular risk factor is dyslipidemia, affecting more than 50% of US adults.3 Some epidemiologic studies have reported that midlife high total serum cholesterol (TC) is associated with increased risk of late-onset AD.4 However, the evidence remains mixed. A 2017 meta-analysis using data from cohort studies on the association between serum cholesterol and risk of late-life cognitive outcomes detected significant gaps in the literature, including insufficient data to examine cholesterol sub-fractions (e.g., HDL, non-HDL), sex differences, and APOE interactions.4 Moreover, studies evaluating midlife cholesterol lacked clear information on the age of cholesterol exposure.4

To address some of these key gaps, we evaluated extensive longitudinal clinical data from a prospective cohort with research-quality case ascertainment to determine associations between cholesterol levels at specific ages and subsequent AD risk. We hypothesized that serum cholesterol levels (i.e., HDL and non-HDL) may be associated with subsequent AD risk. Specifically, we hypothesized that higher non-HDL levels in the 50s-70s would be associated with higher AD risk and that higher HDL cholesterol levels would be associated with lower AD risk.

METHODS

Design, Study Setting, and Participants

The research protocol for this population-based prospective cohort study was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards of Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPW) and the University of Washington. Participants provided written informed consent.

The Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study enrolled dementia-free consenting participants randomly sampled from Seattle-area KPW members aged ≥65 starting in 1994–1996.5 Additional details of the ACT study have been previously reported.5 ACT’s Completeness of Follow-Up Index (>97%) has been exemplary.6

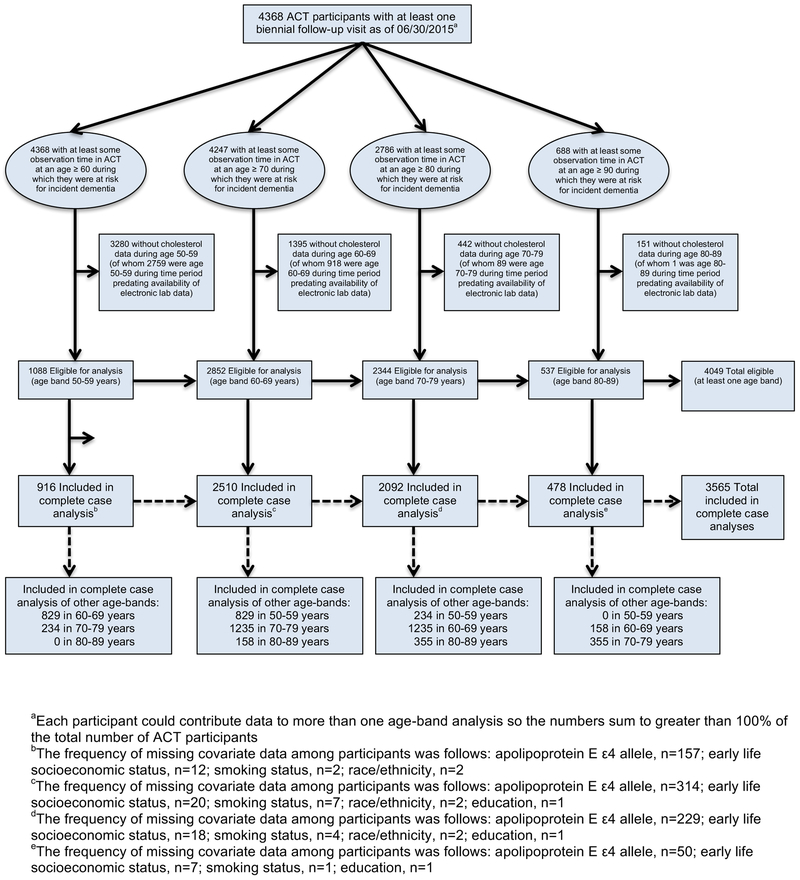

Our current analysis estimated associations between cholesterol level exposures during specific age bands (50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80–89 years old) and subsequent risk for AD and other dementias. We identified separate, partially overlapping, sub-cohorts of ACT participants for four separate exposure age band analyses (Figure 1). We describe the inclusion criteria for the age 60–69 sub-cohort in detail here; the other sub-cohorts followed analogous specifications. ACT participants included in the age 60–69 sub-cohort were required to: have at least one biennial follow-up visit at or after age 60; have at least one cholesterol measure (total cholesterol (TC) and HDL) recorded between ages 60 and 69; and be dementia-free and under observation in ACT as of age 70 or later. Data through June 30, 2015 were included in these analyses. Of the 4,368 participants with at least one biennial follow-up visit in the ACT study, there were 1,088 eligible for the age 50–59 analyses, 2,852 for the age 60–69 analyses, 2,344 for the age 70–79 analyses, and 537 for the age 80–89 analyses (Figure 2). A comparison of included versus excluded participants is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Study Design

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram of Study Samples

Identification of Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia

Participants were assessed with the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI) at study entry and subsequent biennial visits. CASI scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better cognitive performance.7 Participants with scores ≤85 underwent a standardized diagnostic evaluation for dementia and a battery of neuropsychological tests. Results of these evaluations and laboratory and imaging records were then reviewed in a multidisciplinary consensus conference.8 Diagnoses of dementia and probable or possible AD were made using research criteria.9,10 Dementia-free participants continued scheduled follow-up visits. Participants with new-onset dementia underwent at least one annual follow-up examination to confirm the diagnosis of dementia.

Cholesterol

Clinical measures of TC and HDL were captured for KPW members by computerized laboratory data from 1988 onward. Non-HDL levels were computed by subtracting HDL from TC. For each ACT participant included in the four age band analyses, we computed the participant’s average observed cholesterol measures (i.e., HDL, non-HDL) using all recorded measures in the laboratory database during the specific age band.

APOE genotype

APOE genotype data were available for 4,427 (87%) of all ACT participants. APOE genotype was determined using published methods and categorized as presence or absence of any ε4 alleles.11

Covariates

Based on a review of the literature, we selected covariates that may confound associations between cholesterol and AD risk.4 Demographic factors included age, sex, self-reported race, and education, characterized as at least some college vs. high school or less. Body mass index (BMI), measured at ACT visits and calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, was unavailable for many participants during the age band exposure window of interest due to the window predating the individual’s enrollment in ACT. As such, we imputed BMI during the age band of interest for each individual based on a mixed effects model of BMI trajectories as a function of age and sex. The model utilized all participants’ observed BMI measures across study visits and included main and interacting effects for age and sex, along with participant-specific random intercepts and slopes. Participants were asked about smoking status (ever vs. never at ACT baseline). Participants were also asked about early life socioeconomic status using a financial difficulty rating (range 1–10). Treatment for hypertension and diabetes was determined using KPW pharmacy data as receipt of at least two fills of a medication from the respective therapeutic class within a calendar year period at any point during or before the cholesterol age band exposure window of interest.

Statins and other cholesterol lowering drugs

Our primary goal was to investigate the impact of serum cholesterol levels as a biological risk factor for late-onset AD, independent of treatments used to achieve a certain cholesterol level. HMG-Co-A reductase inhibitors (“statins”) reduce TC and LDL cholesterol (and non-HDL cholesterol), and some may increase HDL-cholesterol, and thus may have an impact on cognitive decline and dementia. A recent systematic review highlighted that prior literature from both randomized controlled trials and observational studies does not support a causal effect of statin use on cognitive decline or dementia.12 Thus, we decided a priori to not adjust for statin use in our primary analysis. However, we assessed the impact of this decision by performing sensitivity analyses adjusting for statin use, as well as performing analyses separately for those who did not receive a statin during the 10-year age band when cholesterol was assessed.

Statistical Analysis

For each of the four age band analyses, we estimated the association between average HDL cholesterol and average non-HDL cholesterol during the specified ages and risk of incident AD and all-cause dementia. To estimate these associations, we used Cox regression with a separate model fit for each exposure (HDL, non-HDL) and outcome (AD, all-cause dementia) pair within a given age band sample. Age served as the time-axis for these models, with participants followed from sub-cohort entry to the earliest of outcome onset (event) or last study visit before September 30, 2015 (censoring). Participants who withdrew from ACT or died before the end of the study period and before any outcome onset were censored at their last study visit. Timing of AD or dementia onset was set as the midpoint between the ACT visit that triggered the diagnosis and the preceding visit, as is ACT’s convention.13,14 For the analyses of AD, onset of non-AD dementia was treated as a censoring event.

Average HDL or non-HDL cholesterol exposures were included in Cox models using natural cubic splines with knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the cholesterol distribution for a given analysis to allow for the potential that associations between cholesterol and cognitive outcomes may be non-linear, as has been suggested in other studies (further information regarding spline models provided in Supplementary Explanatory Text).15,16 Adjustment covariates included sex, education, self-reported race, smoking history, treatment for hypertension or diabetes, BMI, and early life SES. In addition, we stratified Cox models by ACT study cohort (original, expansion, continuous enrollment) and APOE genotype to account for the potentially different underlying baseline hazards due to calendar time and genetic risk. The estimated adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals were graphed, showing hazards at various levels of HDL or non-HDL cholesterol compared to the hazards at a reference level. For clarity of presentation, across figure panels we used a common reference level (55 mg/dL for HDL, 160 mg/dL for non-HDL) that was near the median for most age band analyses. Overall tests of significance (two-sided, alpha=0.05) for the associations were performed based on joint (omnibus) test of the null hypothesis that the model spline parameters were simultaneously zero. We assessed proportional hazards using Schoenfeld residuals.

For the age bands containing the largest sample sizes (60–69 and 70–79 years), we performed additional subgroup analyses to investigate potential effect modification by sex and APOE genotype. For these investigations, we fit separate models for men and women, and similarly, separate models for those with and without an APOE ε4 allele. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R, version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Participants in younger age bands compared to those in older age bands had more years of follow-up, had higher proportions from the replacement ACT cohort (than from the original or expansion cohorts), and had higher proportions with education beyond high school (Table 1). The average non-HDL cholesterol levels were lower in the older age bands than in the younger age bands, while the average HDL cholesterol levels were similar across age bands.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ACT Participants Included in the Study

| 50-59 years | 60-69 years | 70-79 years | 80-89 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total participants | 1088 | - | 2852 | - | 2344 | - | 537 | - |

| Total participantsa | 916 | - | 2510 | - | 2092 | - | 478 | - |

| Total possible/probable AD eventsa | 53 | - | 412 | - | 538 | - | 107 | - |

| Total all-cause dementia eventsa | 66 | - | 514 | - | 647 | - | 117 | - |

| Years of follow up, median (25th, 75th) | 6 (3, 8) | 7 (4, 12) | 5 (2, 8) | 2 (1, 4) | ||||

| ACT cohort | ||||||||

| Original | 50 | 4.6 | 1253 | 43.9 | 1452 | 61.9 | 360 | 67.0 |

| Expansion | 199 | 18.3 | 537 | 18.8 | 512 | 21.8 | 118 | 22.0 |

| Replacement | 839 | 77.1 | 1062 | 37.2 | 380 | 16.2 | 59 | 11.0 |

| Age at start of follow up, median (25th, 75th) | 70 (68, 72) | 71 (70, 75) | 80 (80, 81) | 90 (90, 90) | ||||

| Female | 602 | 55.3 | 1626 | 57.0 | 1431 | 61.0 | 360 | 67.0 |

| Non Hispanic whiteb | 932 | 85.8 | 2498 | 87.6 | 2107 | 90.0 | 498 | 92.7 |

| Education beyond high school | 954 | 87.8 | 2111 | 74.0 | 1521 | 64.9 | 328 | 61.2 |

| ≥1 APOE ε4 alleles | 261 | 28.0 | 697 | 27.5 | 511 | 24.2 | 97 | 19.9 |

| Body mass index, median (25th, 75th) c | ||||||||

| Underweight | 10 | 0.9 | 18 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Normal | 233 | 21.4 | 647 | 22.7 | 672 | 28.7 | 203 | 37.8 |

| Overweight | 383 | 35.2 | 1205 | 42.3 | 1068 | 45.6 | 240 | 44.7 |

| Obese | 462 | 42.5 | 982 | 34.4 | 594 | 25.3 | 91 | 16.9 |

| Ever treated for hypertension | 375 | 34.5 | 1524 | 53.4 | 1618 | 69.0 | 438 | 81.6 |

| Ever treated for diabetes | 48 | 4.4 | 244 | 8.6 | 234 | 10.0 | 53 | 9.9 |

| Ever smoker | 538 | 49.5 | 1500 | 52.7 | 1153 | 49.3 | 225 | 42.0 |

| Early life SES: Financial difficult rating (1-10), median (25th, 75th) | 5 (3, 7) | 5 (3, 7) | 5 (4, 8) | 5 (4, 8) | ||||

| Statin prescription fill during age band | 60 | 5.5 | 506 | 17.7 | 632 | 27.0 | 215 | 40.0 |

| Number of cholesterol measures, median (25th, 75th) | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 7) | 3 (1, 8) | ||||

| Average non-HDL cholesterol, median (25th, 75th) | 164 (139, 188) | 165 (141, 192) | 159 (134, 186) | 143 (121, 171) | ||||

| Average HDL cholesterol, median (25th, 75th) | 54 (44, 66) | 54 (44, 66) | 55 (46, 67) | 57 (48, 69) | ||||

Complete case analysis

In the 50-59 years age band, there were 41 blacks (3.8%), 41 Asian Americans (3.8%), 20 Hispanics (1.8%), and 52 people of other race groups (4.8%). In the 60-69 years age band, there were 114 blacks (4.0%), 123 Asian Americans (4.3%), 38 Hispanics (1.3%), and 77 people of other race groups (2.7%). In the 70-79 years age band, there were 80 blacks (3.4%), 89 Asian Americans (3.8%), 19 Hispanics (0.8%), and 47 people of other race groups (2.0). In the 80-89 years age band, there were 15 blacks (2.8%), 15 Asian Americans (2.8%), 4 Hispanics (0.7%), and 5 people of other race groups (0.9%).

Body mass index was computed as a predicted value for the midpoint of each age band using a linear mixed effects model of the BMI trajectories over time for all ACT participants.

Abbreviations: TC, total cholesterol; SES, socioeconomic status

Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, and Cholesterol

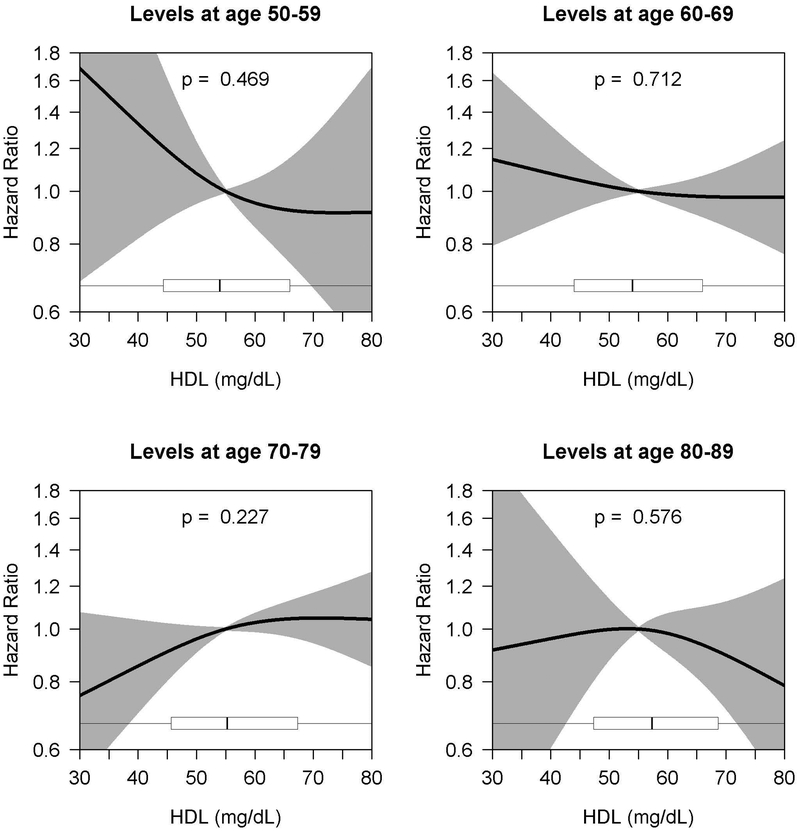

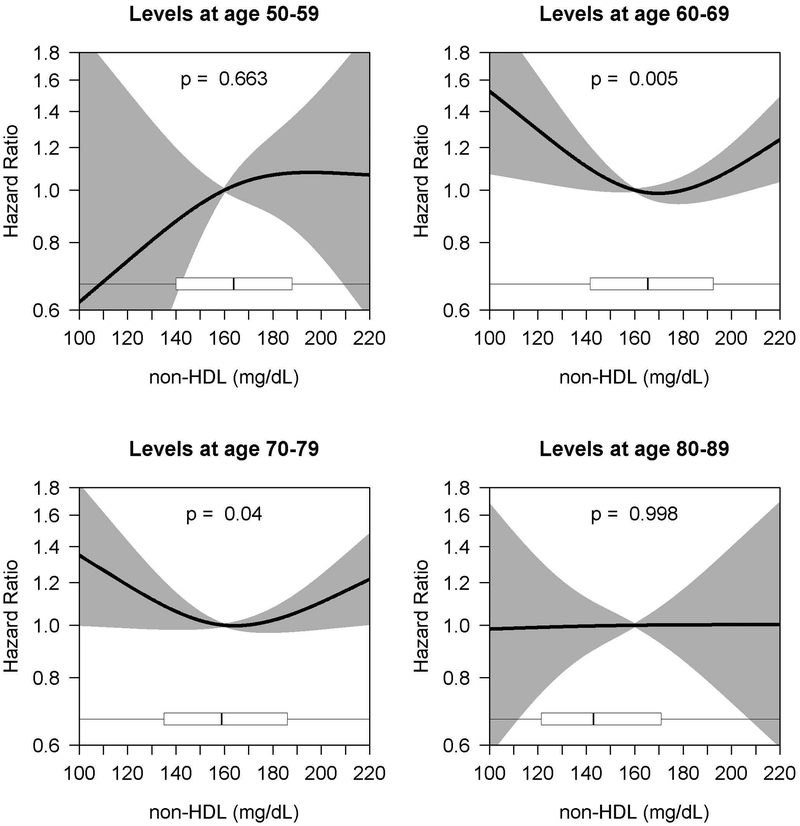

Among the 3565 total people included in complete case analyses, 877 developed all-cause dementia. A total of 713 of these cases were possible/probable AD. Among the other 164 were 71 cases of vascular dementia, 38 cases of ‘other medical causes of dementia’, 28 cases of multiple etiologies, 4 cases of ‘substance use related dementia’, and 23 cases of other or unknown cause (data not shown). For the age bands containing the largest sample sizes (60–69 and 70–79 years), 412 and 538 participants developed possible or probable AD, and 514 and 647 participants developed all-cause dementia. Figures 3 and 4 (and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) show the age band analyses of the adjusted association between HDL and non-HDL cholesterol levels and AD. No statistically significant association was found in any of the age bands for HDL cholesterol and AD (Figure 3). For the association between non-HDL cholesterol and AD, a statistically significant association was found among the 60–69 and 70–79 age bands (p=0.005 and p=0.04, respectively), suggesting a potential U-shaped relationship with modestly higher risk at low and high levels (Figure 4). The association was strongest in the 60–69 age band, particularly at low levels of non-HDL cholesterol. In that age band, for example, compared to those with an average non-HDL of 160 mg/dL, the estimated HR for those with an average non-HDL of 120 mg/dL was 1.29 (95% CI, 1.04–1.61), while the estimated HR for those with an average of 210 mg/dL was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.01–1.33). The association for the 70–79 age band was less pronounced, with an estimated HR of 1.19 (95% CI, 0.99–1.42) when comparing 120 to 160 mg/dL and a HR of 1.16 (95% CI, 1.00–1.34) when comparing 210 to 160 mg/dL. For the outcome of all-cause dementia, we found similar results (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 3.

Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease

aCurves depict hazard ratios (with shading representing 95% confidence intervals) comparing the average HDL cholesterol level given on the x-axis to a reference value of 55 mg/dL. Cholesterol level was modeled using natural cubic splines (with knots at 10%, 50%, and 90%-iles of exposure distributions); p-values provided are for joint (omnibus) tests of these spline parameters. Boxplots summarize the distribution of average HDL cholesterol levels observed in the sample. Models adjusted for sex, race, education, early life financial difficulty rating, smoking, treatment for hypertension or diabetes, BMI, and stratified by ACT cohort and APOE genotype.

Figure 4.

Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease

aCurves depict hazard ratios (with shading representing 95% confidence intervals) comparing the average non-HDL cholesterol level given on the x-axis to a reference value of 160 mg/dL. Cholesterol level was modeled using natural cubic splines (with knots at 10%, 50%, and 90%-iles of exposure distributions); p-values provided are for joint (omnibus) tests of these spline parameters. Boxplots summarize the distribution of average non-HDL cholesterol levels observed in the sample. Models adjusted for sex, race, education, early life financial difficulty rating, smoking, treatment for hypertension or diabetes, BMI, and stratified by ACT cohort and APOE genotype..

Sensitivity Analyses: Sex, APOE genotype, and statin use

For the age bands containing the largest sample sizes (60–69 and 70–79 years), we performed stratified analyses by sex and APOE genotype. For the outcome of AD, stratification by sex did not reveal statistically significant associations for HDL cholesterol exposure within women or men in either age band (Supplementary Figure S3). For non-HDL cholesterol, though, women with high average non-HDL cholesterol levels (e.g., >220 mg/dL) during ages 60–69 had significantly increased AD risk relative to those with an average non-HDL level of 160 mg/dL (p=0.014), a pattern seen similarly in men in that age band (though non-significant, p=0.320). Conversely, during ages 70–79, a significant association was only seen among men and was in the opposite direction, with low average non-HDL cholesterol levels associated with higher AD risk among men (p=0.003) (Supplementary Figure S4).

Stratifying by APOE status for the HDL cholesterol/AD association found modest evidence of increased AD hazards with low HDL cholesterol levels relative to levels of 55 mg/dL during ages 60–69 among participants with ≥1 APOE ε4 allele (p=0.045), an association not observed in those without an ε4 allele (p=0.680) (Supplementary Figure S5). This same association, however, was not seen in the age 70–79 analysis. Further, stratification by APOE genotype did not show significant associations for non-HDL cholesterol exposure in any age subgroups Supplementary Figure S6). Similar results were found for all-cause dementia (Supplementary Figures S7-10).

Adjusting for any statin use during the 10-year age band when cholesterol was assessed did not change the primary results (Supplementary Figures S11 and S12). In addition, performing analyses separately for those who did not receive a statin did not change the primary results (Supplementary Figures S13 and S14).

DISCUSSION

In our prospective community-based cohort study, we found an overall significant association between higher AD risk and non-HDL levels among the 60–69 and 70–79 decades. This finding revealed a potential U-shaped relationship with modestly higher AD risk at both low and high levels of non-HDL cholesterol. The association was strongest in the 60–69 age band, particularly at low levels of non-HDL cholesterol. The association for the 70–79 age band was in the same direction but less pronounced. We did not find an association between HDL cholesterol levels and subsequent AD risk.

Most studies that have investigated associations between cholesterol and AD risk have focused on total cholesterol as an exposure17–20 and have categorized (into quartiles21–23) or dichotomized17,19 the measure, and they have yielded inconsistent results.4,17–24 Evidence for differential risk for AD among lipid fractions suggests the need to evaluate them separately.4 Moreover, categorizing continuous variables comes at a cost, most notably concealing non-linearity in associations between exposure and outcome.25 Prior studies have also been limited by a relatively small number of AD cases; the 8 studies we are aware of ranged from 2719 to 53224 cases, with a median of 91 and a total across all 8 studies of 1,153 AD cases.17–24 These studies also did not investigate whether age of exposure to different levels of cholesterol mattered in terms of dementia risk.

To address some of these limitations, we evaluated data from a large cohort of well-characterized individuals with a large number of AD cases. Indeed, we had roughly as many AD cases in each of our largest age bands (412 and 538) as in the largest single prior study we are aware of (n=532).24 Further, our complete case analytic sample resulted in 713 unique possible/probable AD cases (877 all-cause dementia cases). The extensive clinical laboratory data available and the long-term follow-up of the cohort afforded us the opportunity to evaluate hazards associated with cholesterol levels using a spline model, so we could evaluate risk across the entire spectrum of observed cholesterol levels. This a priori modeling decision suggested a non-linear, non-monotonic association between non-HDL cholesterol levels and AD risk.

We found evidence of sex differences across age bands for the association between non-HDL cholesterol and AD risk. Women with high non-HDL levels during ages 60–69 and men with low non-HDL levels during ages 70–79 had increased AD risk. Moreover, among those with ≥1 APOE ε4 alleles, low HDL levels were associated with increased AD risk. While high levels of non-HDL are clearly associated with greater vascular risk, there is some evidence that low levels of non-HDL may also be associated with adverse outcomes, including intracerebral hemorrhage.26 Iribarren et al reported a significant association between low cholesterol level and intracerebral hemorrhage in older men.27 For the APOE finding, it is not clear if low HDL levels reflect early AD development or if the low HDL levels accelerate AD pathogenesis.

Our main finding of a U-shaped association between AD and levels of non-HDL cholesterol during mid to late life has biological plausibility.22 Cholesterol is needed for normal neuronal functioning. Low cholesterol levels may indicate early manifestations of chronic disease, which may lead to cognitive impairment, frailty, and eventual AD.22 Conversely, high cholesterol levels may accelerate AD pathogenesis. Evidence from a mouse model suggests that high dietary cholesterol increases Aβ accumulation and accelerates AD-related pathology.28 Future research is needed to explore potential mechanisms of age-varying risks of non-HDL cholesterol and AD. It is important to note that our primary findings are agnostic to treatment to lower cholesterol29, so our results do not specify if these levels are naturally low or therapeutically reduced. Although we did not incorporate statins (or other lipid-lowering medications) in our primary analysis, sensitivity analyses adjusting for statin use as well as stratified analyses among those who did not receive a statin did not meaningfully change the overall results. Data on the association of long-term statin use will become available in the coming years.

Strengths of this study include the large sample with minimal attrition and prospective ascertainment of research-quality cases. Several limitations should be acknowledged. The potential for confounding by unmeasured or unknown factors cannot be excluded. We were limited to available cholesterol measures obtained at irregular intervals to estimate cholesterol exposures, as is the case with all clinical, real-world data. As such, we measured average cholesterol levels within decade-long age bands to summarize exposures at different ages. Others have assessed single cholesterol levels4 or changes within individuals in cholesterol levels over time and their association with AD risk.18 We did not have sufficient clinical data to estimate complex cholesterol exposure summaries. It is important to recognize that these different approaches to cholesterol exposure address different research questions, with our analysis revealing potentially important risk periods for subsequent AD. In addition, the youngest (50–59 years) and oldest (80–89 years) age bands had the smallest sample sizes, limiting our ability to estimate precise effects and draw conclusions. Our imputation of BMI values also deserves mention. To avoid inefficient analyses of complete cases requiring presence of a BMI value, we chose to impute BMI using a mixed effects model of BMI trajectories as a function of age and sex. Of note, the association between BMI and AD is mixed30,31 so we do not anticipate this analytic decision had a significant impact on our results. Of note, we did not have sufficient sample sizes of other types of dementias (e.g., vascular) to draw conclusions. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other groups.

In conclusion, we found that people with low (120 mg/DL) and high (210 mg/dL) levels of non-HDL cholesterol during their 60 and 70s had higher risk for AD and all-cause dementia compared to people with intermediate (160 mg/DL) levels of non-HDL cholesterol.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Explanatory Text. Methods Describing Use of Splines

Supplementary Table S1. Characteristics of ACT Participants Included or Excluded in the Study

Supplementary Table S2. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease

Supplementary Table S3. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease

Supplementary Figure S1. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia

Supplementary Figure S2. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia

Supplementary Figure S3. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S4. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S5. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Alleles

Supplementary Figure S6. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Alleles

Supplementary Figure S7. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S8. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S9. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Alleles

Supplementary Figure S10. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Allele

Supplementary Figure S11. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Adjusted for Any Statin Use

Supplementary Figure S12. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Adjusted for Any Statin Use

Supplementary Figure S13. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Among Those with No Statin Use

Supplementary Figure S14. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Among Those with No Statin Use

Impact Supplement:

We certify that this work is novel. In this observational cohort study, we found that people with low (120 mg/dL) and high (210 mg/dL) levels of non-HDL cholesterol during their 60s and 70s had modestly higher risk for AD and all-cause dementia compared to people with intermediate (160 mg/dL) levels of non-HDL cholesterol. We conclude that modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, like dyslipidemia, should be targeted prior to late life to minimize risk of AD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding/Support: This research was funded by a National Institute on Aging grant (U01AG006781). Dr. Marcum was supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality grant (K12HS022982). The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of ACT participants.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, or affiliations, or other potential conflicts of interest to report.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017;390:2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toth PP, Potter D, Ming EE. Prevalence of lipid abnormalities in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006. J Clin Lipidol 2012;6:325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anstey KJ, Ashby-Mitchell K, Peters R. Updating the Evidence on the Association between Serum Cholesterol and Risk of Late-Life Dementia: Review and Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;56:215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet 2002;359:1309–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 1994;6:45–58; discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol 2002;59:1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AP A. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuang D, Kukull W, Sheppard L, et al. Impact of sample selection on APOE epsilon 4 allele frequency: a comparison of two Alzheimer’s disease samples. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996;44:704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Power MC, Weuve J, Sharrett AR, Blacker D, Gottesman RF. Statins, cognition, and dementia-systematic review and methodological commentary. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11:220–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:401–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray SL, Dublin S, Yu O, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of incident dementia or cognitive decline: prospective population based study. BMJ 2016;352:i90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzl H, Kaider A. Gaining more flexibility in Cox proportional hazards regression models with cubic spline functions. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1997;54:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wendell CR, Zonderman AB, Katzel LI, et al. Nonlinear associations between plasma cholesterol levels and neuropsychological function. Neuropsychology 2016;30:980–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ 2001;322:1447–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mielke MM, Zandi PP, Shao H, et al. The 32-year relationship between cholesterol and dementia from midlife to late life. Neurology 2010;75:1888–1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Notkola IL, Sulkava R, Pekkanen J, et al. Serum total cholesterol, apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroepidemiology 1998;17:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart R, White LR, Xue QL, Launer LJ. Twenty-six-year change in total cholesterol levels and incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Arch Neurol 2007;64:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G, Shofer JB, Kukull WA, et al. Serum cholesterol and risk of Alzheimer disease: a community-based cohort study. Neurology 2005;65:1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beydoun MA, Beason-Held LL, Kitner-Triolo MH, et al. Statins and serum cholesterol’s associations with incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Journal Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitz C, Tang MX, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Association of higher levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in elderly individuals and lower risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2010;67:1491–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schilling S, Tzourio C, Soumare A, et al. Differential associations of plasma lipids with incident dementia and dementia subtypes in the 3C Study: A longitudinal, population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman DG, Royston P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ 2006;332:1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottesman RF. Dementia After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:916–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iribarren C, Jacobs DR, Sadler M, Claxton AJ, Sidney S. Low total serum cholesterol and intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke: is the association confined to elderly men? The Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. Stroke 1996;27:1993–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Refolo LM, Malester B, LaFrancois J, et al. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates the Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Dis 2000;7:321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krumholz HM, Lee TH. Redefining quality--implications of recent clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2537–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qizilbash N, Gregson J, Johnson ME, et al. BMI and risk of dementia in two million people over two decades: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2015;3:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordestgaard LT, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. Body mass index and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a medelian randomization study of 399,536 individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:2310–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Explanatory Text. Methods Describing Use of Splines

Supplementary Table S1. Characteristics of ACT Participants Included or Excluded in the Study

Supplementary Table S2. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease

Supplementary Table S3. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease

Supplementary Figure S1. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia

Supplementary Figure S2. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia

Supplementary Figure S3. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S4. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S5. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Alleles

Supplementary Figure S6. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Alleles

Supplementary Figure S7. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S8. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by Sex

Supplementary Figure S9. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Alleles

Supplementary Figure S10. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and All-Cause Dementia, Stratified by 0 vs. ≥1 APOE ε4 Allele

Supplementary Figure S11. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Adjusted for Any Statin Use

Supplementary Figure S12. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Adjusted for Any Statin Use

Supplementary Figure S13. Age-Varying Association of HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Among Those with No Statin Use

Supplementary Figure S14. Age-Varying Association of non-HDL Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease, Among Those with No Statin Use