Abstract

The treatment of skin with low-power continuous wave (CW) near-infrared (NIR) laser prior to vaccination is an emerging strategy to augment the immune response to intradermal vaccine, potentially substituting for chemical adjuvant, which has been linked to adverse effects of vaccines. This approach proved to be low-cost, simple, small, and readily translatable compared to the previously explored pulsed wave (PW) medical lasers. However, little is known on the mode of laser-tissue interaction eliciting the adjuvant effect.

Here we sought to identify the pathways leading to the immunological events by examining the alteration of responses resulting from genetic ablation of innate subsets including mast cells (MCs) and specific dendritic cell (DC) populations in an established model of intradermal vaccination, and analyzing functional changes of skin microcirculation upon the CW NIR laser treatment in mice. We found that CW NIR laser transiently stimulates MCs via generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), establishes an immunostimulatory milieu in the exposed tissue, and provides migration cues for dermal CD103+ DCs without inducing prolonged inflammation, ultimately augmenting the adaptive immune response.

These results indicate that use of NIR laser with distinct wavelength and power is a safe and effective tool to reproducibly modulate innate programs in skin. These mechanistic findings would accelerate the clinical translation of this technology and warrant further explorations into the broader application of NIR laser to the treatment of immune-related skin diseases.

Keywords: Adjuvant, near-infrared laser, reactive oxygen species, mast cells, dendritic cells

Introduction

Skin-based vaccination has been demonstrated to permit dose-sparing of the vaccine antigen and improve long-term protection conferred by vaccination, thus showing clear advantages over the standard intramuscular injection (1–3). However, modern inactivated vaccines used for intradermal (ID) influenza vaccination, for instances, are still poorly immunogenic and induce little protective T-cell response, conferring insufficient protection to vulnerable populations including children and the elderly (4–6). The shortcomings of the current inactivated vaccine strategies would be improved by use of immunologic adjuvants, as incorporation of an adjuvant into vaccine formulations is an established strategy to enhance immunogenicity of a vaccine antigen and induce long-term immunity and protective T-cell responses (7). Unfortunately, most conventional chemical or biological adjuvants are inappropriate for use in the skin due to issues related to the potential to induce persistent local toxicity caused by over-stimulated innate immunity in the confined space (8, 9). As a result, none of adjuvant has been incorporated into clinically approved intradermal vaccines.

Recently, stimulating the skin with a physical parameter, namely laser light, prior to the administration of an intradermal vaccine has been shown to augment the immunogenicity without applicable adverse effects, representing an emerging approach alternative to the conventional chemical or biological adjuvants (10). To date, four classes of lasers have been used to enhance the efficacy of vaccines in preclinical mouse models (11). The application of non-ablative fractional laser has been demonstrated to augment the immune response to a model ID influenza vaccine via release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from columns of coagulated (dead) tissue created after the treatment of skin with fractional laser, and subsequent recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) around the columns (12, 13). Ablative fractional laser has been similarly shown to activate skin-resident Xcr1+ DC and enhance the efficacy of prophylactic and therapeutic tumor vaccines through the local inflammatory response induced by dead keratinocytes around skin micropores (14). On the other hand, brief exposures of skin with low power, visible pulsed wave (PW) laser were also found to augment the immune response to a model ID vaccine via release of hsp70 from skin cells and subsequent activation of skin-resident Langerhans cells (15), or disruption of cell–matrix interactions induced by disarray of dermal collagen fibers and resultant increase in the motility of antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the skin tissue (9, 16, 17). In contrast to the fractional lasers, this class of visible pulsed wave (PW) laser induces no histological skin tissue damage (9), but its condensed energy in laser pulses induces the heat shock response (15) or ultrastructural change in the extracellular matrix (17). We have shown that another distinct class of laser, a low-power, continuous wave (CW) near-infrared (NIR) invisible laser between 1061–1301 nm significantly enhances the immune response to a model ID vaccine and improves survival in a lethal challenge murine influenza model (18–20). In these studies, exposure of the skin to the CW NIR laser was found to induce no detectable tissue damage or inflammation (18–20). The energy of CW NIR laser, which is delivered homogenously over the time period, is not high enough to induce any heat shock response or ultrastructural change in the exposed tissue (21). These observations indicate that the CW NIR laser has the distinct mechanisms of action compared to the other three PW lasers. We have demonstrated that CW NIR laser induces transient upregulation of a selective set of chemokines in skin and migration of specific subsets of skin-resident DCs (19, 20). However, the precise details of CW NIR laser-skin tissue and cell-cell interactions leading to the augmentation of the immune response are largely unknown.

Here, we demonstrate that CW NIR laser induces a unique immunologic cascade in skin stimulating mast cells (MCs) via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and creates immnostimulatory milieu for DCs, thus augmenting the adaptive immune response. These findings not only contribute to optimization of CW NIR laser for immunologic adjuvant, but open a pathway to broader applications of this technology to treat immune-related conditions.

Materials and Methods

Animals

We purchased eight-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (stock no:000664) from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). We acclimated all animals for at least two weeks prior to the experiments. We purchased breeding pairs of Ccr7−/− (006621), Batf3−/− (013755), KitW-sh/KitW-sh (012861), and CD11c-EYFP (008829) mice from Jackson Laboratories and bred them at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). All animal procedures were performed following the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of MGH.

Near-infrared laser treatment

We applied a Nd:YVO4 1064 nm laser emitting either continuous wave (CW) or nanosecond pulsed wave (PW) at a repetition rate of 10 kHz (RMI laser, Lafayette, CO) on the surface of depilated skin as previously described (19, 20). We used a non-tissue damaging power density of 5 W/cm2 on a circular spot on the skin surface of approximately 5 mm in diameter (0.2 cm2) for 1 minute with a total dose of 300 J/cm2 as previously determined (19, 20). We monitored the skin temperature throughout the laser application using an infrared thermal imager (FLIR Systems).

Influenza vaccination models

We depilated the mouse back skin with commercial depilatory cream (Nair, Church & Dwight) 2 days before the NIR laser treatment and vaccination. We injected an inactivated influenza virus vaccine (A/PR/8/34, 1 μg in 10 μl saline, Charles River) intradermally (ID) in the center of the spot on the mouse back skin within 5 minutes of the laser treatment. The vaccine mixed with Alum (diluted 1:1 v/v, Imject®, Thermo-Fisher) or c48/80 (3.2 ng/spot, Sigma) was used for comparison as appropriate. We homologously challenged mice intranasally with live influenza A/PR/8/34 virus at a dose of 2 × 105 50% egg infectious doses (EID50) at day 28. We euthanized mice and obtained blood and spleen samples for further analysis 4 days after challenge as established previously (18–20).

Antioxidant treatment

We examined the involvement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the effect of NIR laser using a ROS-scavenger. We pre-treated mice with subcutaneous injections of 100 mg/kg N-Acetyl-L- Cysteine (NAC, Sigma) at day −3, −2, −1, 0 as appropriate (22) before the experiment. Control mice received vehicle only (PBS) subcutaneously.

Anti-influenza antibody and hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers

We measured anti-influenza specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c humoral responses by ELISA as previously described (19). We coated Immulon plates (Thermo Scientific) with 100 ng of the inactivated influenza virus and then added serially diluted mouse serum samples to the wells. We detected bound immunoglobulins with the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG [1:10,000, Sigma-Aldrich], rat anti-mouse IgG1 [1:2,000, SouthernBiotech], or goat anti-mouse IgG2c [1:4,000, SouthernBiotech]). We designated a titer as the serum dilution corresponding to the inflection point of the plot of the optical density vs. dilution of serum. SRI International (Harrisburg, VA) determined hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers in sera samples. Operators performed all immunoassays in a blinded manner to control or experimental groups.

Assessment of T cell responses

We harvested and immediately processed splenocytes 4 days after challenge as previously described (18–20). Briefly, we incubated splenocyte preparations containing 1 × 106 cells with or without the inactive influenza at a concentration of 1 μg/ml for 60 hours for determination of cytokine release in a round bottom 96-well plate. We collected splenocyte culture supernatants and determined the amounts of IFN-γ or IL-4 using the DuoSet ELISA Kit (R&D Systems) following manufacturer’s instructions. Operators performed all immunoassays in a blinded manner to control or experimental groups.

Influenza virus challenge study

We challenged immunized mice intranasally with live influenza A/PR/8/34 virus at a dose of 1.5×106 50% EID50, which is equivalent to 150 × 50% mouse lethal dose (MLD50), in 30 μl saline 28 days after vaccination as previously described (18–20). We monitored survival and body weight for 15 days post-challenge. We considered mice showing a hunched posture, ruffled fur, or greater than 20% body weight loss, or mice which were not eating or drinking, to have reached the experimental endpoint. Operators performed monitoring in a blinded manner to control or experimental groups.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) painting assay

We shaved and depilated mice 2 days before the assay. We painted mice on 4 spots of the flank back skin (approximately 5 mm in diameter per spot) with 10 μl of a 0.5 % FITC solution (Isomer I, Sigma) 4 hours prior to the assay as previously described (20, 23). The FITC solution was prepared in acetone:dibutyl phthalate (1:1, vol/vol; Sigma). We performed the NIR laser treatment followed by vaccination with OVA (EndoFit™ Ovalbumin, Invivogen) at each treatment site (10 μg in 10 μl saline per spot, 4 spots in total) on the FITC-painted sites. We then harvested skin-dLN 24 and 48 hours after the vaccination and laser treatment, and then isolated DCs from LN. We mechanically dissociated LN and incubated them with collagenase D (2.5 mg/ml, Roche) and 10 mM EDTA as previously described (24). We labeled cells isolated from LN for CD11c (N418, eBioscience), I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2, eBioscience), CD11b (M1/70, BioLegend), CD103 (2E7, BioLegend), langerin/CD207 (4C7, BioLegend), CD8α (53–6.7, eBioscience) and CD86 (GL1, BioLegend). We also stained isolated cells with Live/dead®-Aqua (Life Technologies) to distinguish live cells. We performed data acquisition on a Fortessa cytometer (BD Bioscience) followed by analysis on FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC). We selected classical lymph node-resident cells (cDCs) based on CD11chi status and I-A/I-E intermediate levels; migratory DCs (migDCs) on CD11c intermediate levels and I-A/I-Ehi status as distinct from cDC, which were further gated for langerin+ (Lang+) vs. CD11b+. We further gated CD11b+ vs. CD103+ subpopulations from cells within the Lang+ migDC gate, as previously described (20, 24, 25).

Reconstitution of sash mice

We reconstituted MC-deficient sash mice with bone-marrow derived MCs (BMMCs) as previously described (26). Briefly, we collected BM from wild-type (WT) host mice. We cultured BM-derived cell suspensions for 6 weeks in the presence of 10 ng/ml IL-3 and 10 ng/ml SCF (R&D Systems) until we obtained a pure population of MCs. We confirmed the differentiation of MCs by flow cytometry with positive staining for c-kit and FcɛRI. We injected 4 × 106 BMMCs into the flank skin of 4-week-old sash mice. We allowed mice to recover for 8 weeks prior to the experiments.

Immunofluorescence analysis of mouse skin

Mouse ears were shaved and depilated 2 days before the tissue preparation. Depilated ears were treated with the NIR laser as described above. Six hours after the treatment, mice were heart-perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde following intravenous injection with DyLight 649-labeled Tomato Lectin (Vector Laboratories). Lymphatic vessels were identified using antibody to Lyve-1 (1:200, clone: ALY7, eBioscience or 1:200, rabbit polyclonal, Relia Tech), CD11b+ or Lang+ DCs were identified using antibody to CD11b (1:200, rabbit polyclonal, Novus Biologicals) or langerin/CD207 (1:200, clone:929F3.01, IMGENEX). We randomly sampled 3–4 photographic imaging stacks (450 × 450 μm2, 40–60 μm thick each) for each ear using confocal laser-scanning microscopy, and determined density and width of perfused blood and lymphatic vessels and spatial relationships between CD11b+ or Lang+ DCs and blood or lymphatic vessels using 3-D analysis system on Imaris software (Bitplane). We counter-stained cell nuclei by DAPI.

CCL21+ cells were identified using antibody to CCL21 (1:200, goat polyclonal, R&D Systems). We determined the total surface area of lymphatic vessels, then quantified the number of CCL21-positive cells on the lymphatic vessels on Imaris software. These parameters were determined in 3–4 photographic areas from each ear.

TUNEL staining of mouse skin

Mice were heart-perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde at 6 hours after the treatment with CW NIR laser at a power of 5.0 W/cm2 for 1 minute. TUNEL staining was performed on 5 μm-thick paraffin sections using the In situ Cell Death Detection Kit TMR Red (Roche Applied Science). Nuclei were identified by counter staining using DAPI. Slides were imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Axio A1, Carl Zeiss North America). Apoptotic cells were identified in red and counted in 4 photographic areas from each skin sample.

Staining of MCs in mouse skin

Mice were heart-perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. Skin biopsies were embedded in paraffin blocks. Five μm-thick paraffin sections were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue (Sigma) (27). Slides were imaged using an inverted microscope (Axio A1, Carl Zeiss). Dermal MCs were identified by their characteristic morphology and staining reactions (28) and counted in 4–5 photographic areas.

Detection of ROS in cultured murine BMMCs and human keratinocytes

Differentiated BMMCs were cultured in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. We used a CW 1064 nm Nd:YVO4 laser for laser treatment as described above. The spot diameter on the well was adjusted to be measured approximately 16 mm in diameter. The BMMC culture was treated with the CW NIR laser at a power of 0.5 W/cm2 for 1–3 min. To detect ROS generation, BMMCs were incubated in 0.5% FBS/HBSS during the laser treatment, then washed and incubated with 0.1 μM H2DCFDA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 15 minutes immediately after the conclusion of the NIR laser treatment. Negative or positive control cells were treated with NAC or H2O2, respectively. ROS-reacted DCF-dependent fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. We performed data acquisition on a Fortessa cytometer (BD Bioscience) followed by analysis on FlowJo v10 software (FlowJo, LLC). Primary cultured human epidermal keratinocytes were purchased from Gibco. The keratinocytes were cultured in EpiLife™ media (Gibco) with Human Keratinocyte Growth Supplement (Gibco) until they reached at 80–90% confluency in 24-well plates. We used a CW 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser (Ventus, Laser Quantum, Cheshire, England) for laser treatment. The laser treatment and ROS detection on the keratinocyte culture were performed as described above. We performed data acquisition on BD Accuri™ C6 Cytometer (BD Bioscience) followed by analysis on the FlowJo software. Fold increase in DCF-positive population compared to no laser-treated control was calculated for each experiment.

Quantitative PCR analysis of chemokine expression in mouse skin and cultured murine BMMCs

Skin sections measuring 0.2 mm2 including both the epidermis and dermis were excised 6 hours after laser illumination. The skin tissue was homogenized using a bead mill homogenizer, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed using the RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen). Differentiated BMMCs were cultured in 24-well plates and treated with the CW NIR laser at a power of 0.5 W/cm2 for 1 minute as described above. Four hours after the laser treatment, total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed as described above. The samples were tested for previously-identified selected genes of importance (Ccl2, Ccl6, Ccl11, Ccl17, Ccl20, Il1a) in addition to inflammatory cytokines (Ifng, Tnf, Il1b) (19) using an RT2 qPCR Primer Assay (Qiagen) and RT2 SYBR Green ROX™ qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen) on the StepOnePlus PCR System (The Applied Biosystems). Fold changes in the expression over sham-treated controls were normalized against housekeeping genes and calculated following the 2–ΔΔCT method. Ct values which were higher than the cut-off of 40 were not considered as reliable and removed from further analysis.

Quantitative PCR analysis of chemokine expression in cultured human keratinocytes

Human primary keratinocytes were cultured and treated with the CW NIR laser at a power of 0.5 W/cm2 for 1 minute as described above. Four hours after the laser treatment, total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed as described above. The samples were tested on the RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array Human Inflammatory Cytokines & Receptors, Qiagen # 330231) on the GVP-9600 System (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). Fold changes in the expression over no treatment controls were analyzed as described above.

Measurement of microvascular permeability

Microvascular permeability in the skin tissue was measured as previously described (29). Briefly, Evans blue was injected from retroorbital plexus 0, 1, 2, 6 hours after a 1-minute CW 1064 nm laser treatment at 5.0 W/cm2. Thirty minutes after the injection of Evans blue dye, the laser-treated skin tissue portion was excised and dissolved in formamide to elute Evans blue at 55°C overnight. Evans blue leak in the tissue was quantitated by spectorophotometry at 650 nm.

Statistical analyses

We ran a one-way ANOVA across treatments (vaccine ID only, CW 1064 nm, PW 1064 nm, Alum, c48/80, IM, NAC) restricted to the WT genotype with Tukey adjusted post hoc pairwise mean comparison tests. We also ran two-way genotype (WT, Ccr7−/−, Batf3−/−, sash, sash-reconstituted) by treatment factorial ANOVAs with different selected genotypes and treatments depending on the question addressed. A log transformation of antibody titers was applied for antibody titer analysis. Separate analyses were run for the dependent variables: IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c. If the interaction was not significant, we removed it and tested only the main effects of genotype and treatment. Significant main and interaction effects were followed up with Tukey post hoc tests. Since the antibody responses of WT mice injected with or without vehicle for NAC treatment were not statistically significant for all the treatments, we pooled the results within the same treatment groups.

For qPCR results, in addition to Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test with stepdown bootstrap and false discovery rate corrections (30), we ran a discriminant analysis to see if previously identified selected genes of importance (Ccl2, Ccl6, Ccl11, Ccl17, Ccl20, Ifng, Tnf, Il1a, Il1b) (19) could predict the effect of the NIR laser treatment.

The data analysis for this paper was conducted using SAS/STAT® software for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, Version 9.4) and Prism 7 (GraphPad software 2016). We used the SAS Candisc Procedure followed by SAS Stepdisc Procedure for the discriminant analysis. Data were pooled from at least two independent experiments.

Results

MCs mediate the adjuvant effect of the CW NIR laser

MCs are enriched for the expression of genes encoding a diverse array of factors involved in the innate and adaptive immune response (31) and play a critical role in host defense against parasitic, bacterial and viral infections (32–36). We therefore hypothesized that the CW NIR laser stimulates connective tissue MCs (CTMCs) in skin and initiates an immunostimulatory milieu for skin-resident DCs. To test this hypothesis, we compared the immune response to an experimental ID influenza vaccination (whole inactivated influenza A/PR/8/34 virus) with or without CW or nanosecond PW NIR laser treatment at 5.0 W/cm2 for 1 minute (18–20), or a MC activator c48/80 (37) in mice.

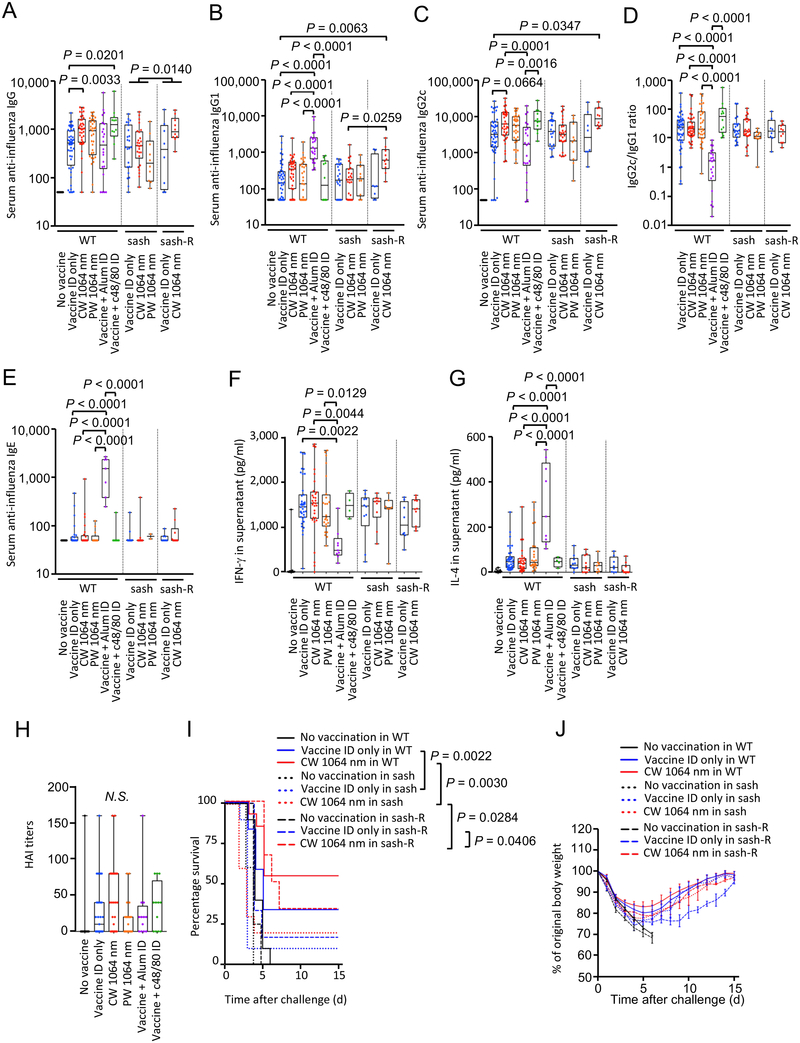

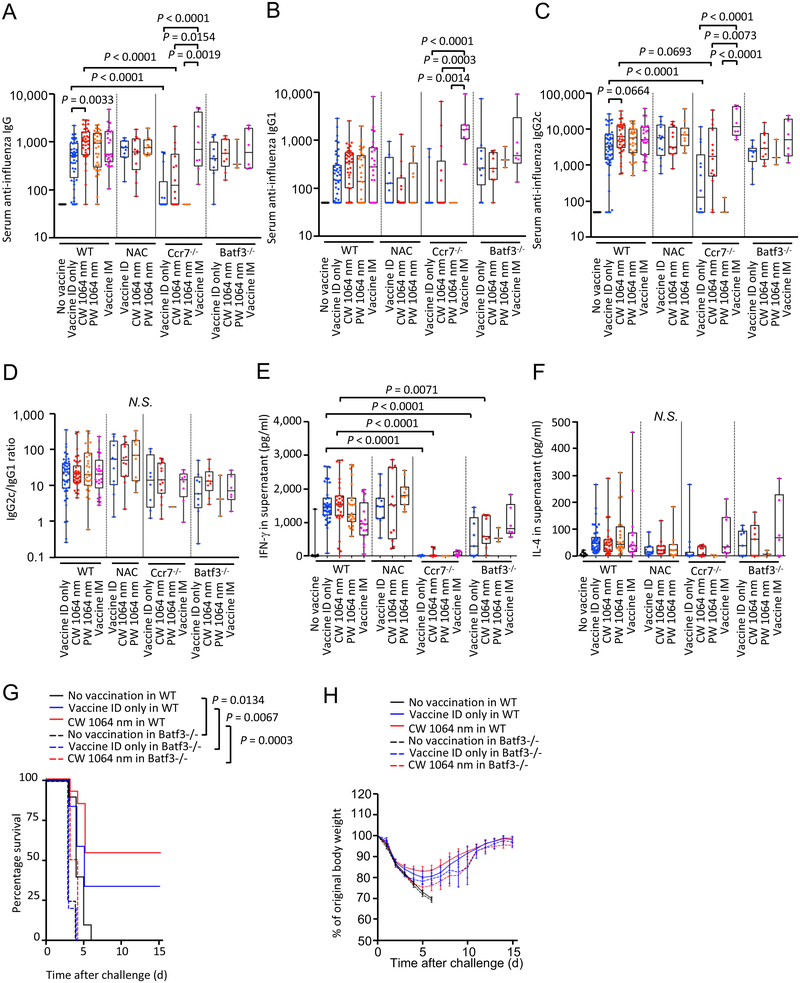

Consistent with the previous reports (18–20), the CW, but not PW, NIR laser significantly augmented anti-influenza IgG response (Fig. 1A, the CW laser vs. ID only group for IgG: P = 0.0033), provoked a statistically marginal increase in IgG2c (Fig. 1C, the CW laser vs. ID only group for IgG2c: P = 0.0664), induced similar anti-influenza IgG2c:IgG1 ratios (Fig. 1D) without increasing IgE responses (Fig. 1E) and IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion levels from ex vivo stimulated splenocytes (Fig. 1F–G), and increased the HAI geometric mean titers (GMTs) (the CW laser vs. ID only, 18.81, 95% CI, 9.024 – 39.19 vs. 6.936, 95% CI, 3.52 – 13.67) (Fig. 1H), compared to the non-adjuvanted ID only group. Interestingly, the application of c48/80 significantly augmented anti-influenza IgG response (Fig. 1A, the c48/80 vs. ID only group for IgG: P = 0.0201), which is consistent with the published literature reporting the adjuvant effect of activated MCs (38, 39), to a similar magnitude as did the CW NIR laser, compared to the ID only group. The GMTs for the c48/80 group were consistently higher (13.13, 95% CI, 3.824 – 45.07) than that of the ID only group, although this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1H). The c48/80 induced similar anti-influenza IgG2c:IgG1 ratios (Fig. 1D) without increasing IgE responses (Fig. 1E) and IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion levels (Fig. 1F–G) compared to the ID only and laser-treated groups, in contrast to alum adjuvant inducing a profoundly-skewed T helper type 2 (TH2) response with high IgE responses (Fig. 1E), low IFN-γ levels (Fig. 1F) and IgG2c:IgG1 ratios (Fig. 1D) (40). These results show that activation of MCs in skin augments the immune response and produces a mixed TH1 and TH2 response.

Figure 1. A critical role of mast cells (MCs) in the effect of the NIR laser on anti-influenza immune responses.

The effect of NIR laser on anti-influenza immune responses was evaluated in wild type (WT) and MC-deficient sash mice. Reconstitution of sash mice was performed by intradermal injection of bone-marrow derived MCs (BMMCs) 8 weeks before vaccination. WT, sash and reconstituted mice were vaccinated with 1 μg of inactivated influenza virus (A/PR/8/34) with or without the NIR laser exposure or c48/80, and challenged intranasally with live homologous virus 28 days after vaccination. Immune correlates were analyzed at day 32. Plates for ELISA were coated with the inactivated influenza virus. Serum anti-influenza specific A, IgG, B, IgG1, C, IgG2c, D, IgG2c/IgG1 ratio, E, IgE are shown. F–G, The effect of the NIR laser on systemic anti-influenza specific T-cell responses. The cytokine responses were measured 4 days after challenge by re-stimulating cultured splenocytes with the inactivated influenza vaccine antigen. Levels of F, IFN-γ and G, IL-4 in supernatants are shown. H, Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers 4 days after challenge are shown. A–D, n= 44, 48, 38, 33, 22, 12, 23, 26, 10, 8, 10, E, n= 40, 29, 25, 13, 7, 7, 15, 17, 2, 8, 10, F–G, n= 35, 39, 30, 24, 9, 4, 10, 10, 7, 8, 10, for no vaccine, vaccine ID only, vaccine ID + continuous wave (CW) 1064 nm, vaccine ID + pulsed-wave (PW) 1064 nm, vaccine + Alum ID, vaccine + c48/80 ID, vaccine ID only in sash, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in sash, vaccine ID + PW 1064 nm in sash, vaccine ID only in sash reconstituted (sash-R), and vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in sash-R groups, H, n= 17, 35, 29, 22, 12, 12 for no vaccine, vaccine intradermal (ID) only, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm, vaccine ID + PW 1064 nm, vaccine + Alum ID, vaccine + c48/80 ID group, respectively. Results were pooled from A–E, 10, F–G, 8, H, 5, independent experiments. P values for the tests of treatments within the WT genotype were based on a one-way between subject ANOVA of the WT data with Tukey post hoc tests, whereas those for other comparisons are based on a two-way Treatment by Genotype ANOVA with Tukey tests. I, Kaplan-Meier survival plots for 15 days following lethal influenza challenge. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. J, The effect of the NIR laser on body weight of vaccinated mice following viral challenge. Body weights were monitored daily for 15 days. Mean body weight ± s.e.m. of each experimental group was determined at each time point. n=10, 12, 13, 5, 10, 10, 4, 6, 6 for no vaccine, vaccine ID only, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm, no vaccine in sash, vaccine ID only in sash, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in sash, no vaccine in sash-R, vaccine ID only in sash-R, and vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in sash-R groups, respectively. I–J, Results were pooled from 4 independent experiments.

To further assess the contribution of MCs to the effect of the NIR laser, the response in MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh (sash) mice, and sash mice selectively reconstituted for MCs in skin (sash-R mice) by ID injection with genetically compatible bone marrow- (BM-) derived MCs from wild type (WT) mice (26) was also evaluated. In this model, MCs were reconstituted locally in the injection sites (Supplementary Fig. S1A–D). The effect of the CW NIR laser on anti-influenza antibody responses was attenuated in sash mice, although a comparable level of antibody responses as well as similar value of IgG2c:IgG1 ratios to those in the ID only group in WT mice was observed (Fig. 1A–D). Interestingly, a level of antibody responses in the CW NIR laser group was higher than that in the ID only group in sash-R mice (Fig. 1A–C). Anti-influenza IgG1 response in the CW NIR group in sash-R mice was significantly higher than that in sash mice (Fig. 1B, P = 0.0259). In addition, anti-influenza IgG2c response in the CW NIR group in sash-R mice was significantly higher than in the ID only group in WT mice (Fig. 1C, P = 0.0347). These results indicate that the attenuated antibody response to the CW NIR in sash mice was restored by the MC reconstitution in the skin tissue and that MCs are critical in augmentation of antibody response with the CW NIR laser.

We next assessed the contribution of MCs to protection augmented by the CW NIR laser. The vaccinated mice were challenged intra-nasally with homologous live influenza virus and monitored for survival time. Consistent with the previous reports (18–20), the CW NIR laser treatment conferred better protection compared to the ID only group (Fig. 1I–J). The survival rate in the ID only group in sash mice was lower than that in WT mice (P = 0.0022), showing a critical role of MCs in host defense (32–36). The survival rate in the CW NIR laser in sash mice was significantly lower than that in WT mice (Fig. 1I–J, WT vs. sash in the CW NIR laser group: P = 0.0030), suggesting that the effect of the CW NIR laser treatment on protection was attenuated in sash mice. In contrast, the CW NIR laser was able to confer significantly better protection compared to the ID only group in sash-R mice (Fig. 1I–J, the CW laser vs. ID only group in sash-R mice: P = 0.0406), indicating that the effect of the CW NIR laser on protection was restored by the MC reconstitution. These results suggest that MCs play a critical role in augmentation of protective immunity with the CW NIR laser.

MCs are known to respond to physical stimuli including heat (41, 42). However, consistent with the previous report (20), the PW NIR laser showed marginal immunological effects (Fig. 1A–H), while it generated the same degree of heat within the skin as did the CW NIR laser (19). These observations collectively suggest that heat plays a minimal role in the effect of the CW NIR laser.

Together, our results support the view that the adjuvant effect of the CW NIR laser in the context of intradermal vaccination functionally depends on MCs in skin.

MCs mediate augmentation of the migration of skin-resident DCs induced by the CW NIR laser

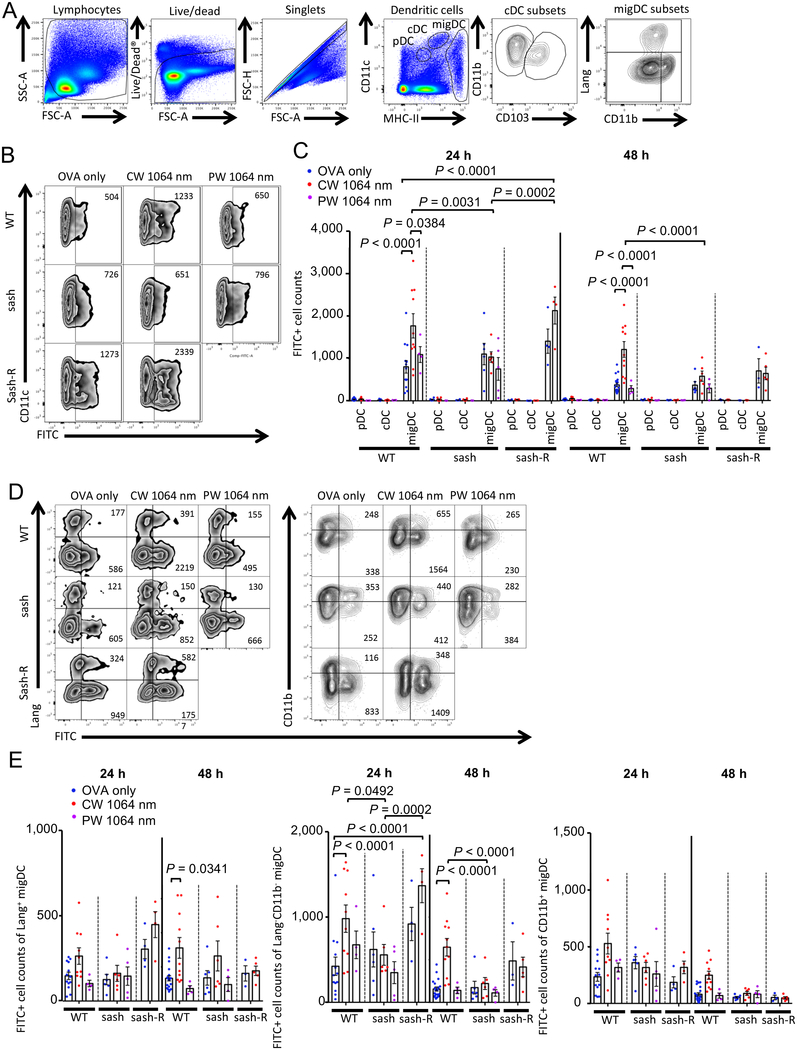

MCs are known to significantly impact on the adaptive immune response by regulating trafficking of DCs to draining LN (dLN) (33, 43). We have previously shown that exposures of skin to the CW NIR laser enhance migration of skin-resident migratory DCs (migDCs), namely the Lang+ and of Lang−CD11b− migDC subsets, while they have no appreciable effect on classical DCs (cDCs) within LN or plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), resulting in augmentation of the adaptive immunity (20). To investigate the role of MCs in the augmentation of migDC migration, we evaluated the migration response in sash and MC-reconstituted sash-R mice using the FITC paint technique (23). We applied FITC solution to the back skin of mice prior to the application of the 1-minute CW NIR laser followed by ID injection of a model vaccine, ovalbumin (OVA). We then measured the migration of migDC subsets into the skin-dLN by flow cytometry as previously described (20).

Consistent with the previous report (20), the CW NIR laser increased the number of FITC+ migDC populations (Fig. 2B–C, P < 0.0001, 24 and 48 hours), and Lang+ (48 hours, P = 0.0341) and Lang−CD11b− (P < 0.0001, 24 and 48 hours) migDC subsets (Fig. 2D–E), as compared to the ID only group. In contrast, the CW NIR laser did not induce any increase in the migDC migration in sash mice, although a comparable level of the migration response to that in the ID vaccine only group of WT mice was observed (Fig. 2B–E). The number of FITC+ migDC and Lang−CD11b− migDC populations of the CW NIR laser group in sash mice was significantly smaller than that in WT mice (Fig. 2A–E, migDC: 24 hours, P = 0.0031; 48 hours, P < 0.0001, Lang−CD11b− migDC: 24 hours, P = 0.0492; 48 hours, P < 0.0001). Interestingly, the CW NIR laser increased the number of FITC+ migDC populations in sash-R mice compared to that in the ID vaccine only group of WT mice (Fig. 2A–C, P < 0.0001, 24 hours) or the CW NIR laser group of sash mice (Fig. 2A–C, P = 0.0002, 24 hours), indicating restoration of the migration response of migDCs to the CW NIR laser by the MC reconstitution. Consistently, sash-R mice showed the significantly higher number of FITC+ Lang−CD11b− migDC population in the CW NIR group compared to those in the ID vaccine only group of WT mice (Fig. 2D–E, P < 0.0001, 24 hours) or the CW NIR laser group of sash mice (Fig. 2D–E, P = 0.0002, 24 hours).

Figure 2. Effect of the NIR laser on DC migration in skin.

The effect of the NIR laser on migration responses of migratory DC (migDC) subsets in skin. Mice were painted with 0.5 % FITC solution on the flank skin 4 hours before vaccination with 40 μg of OVA with or without the NIR laser treatment. Skin-draining lymph nodes (dLN) were analyzed by flow cytometry. A, Gating schematic to identify DC subsets within skin-dLN. Cell counts of B–C, DC subsets, D–E, migDC subsets in the skin-dLN 24 and 48 hours after OVA vaccination are shown. A–D, n= 13, 10, 4, 6, 6, 5, 4, 4 at 24 hours and n= 20, 11, 4, 6, 6, 4, 3, 5 at 48 hours for OVA only in WT, CW 1064 nm in WT, PW 1064 nm in WT, OVA only in sash, CW 1064 nm in sash, PW 1064 nm in sash, OVA only in sash-R, CW 1064 nm in sash-R groups, respectively. Results were pooled from 6 independent experiments and analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests.

These results indicate that MCs mediate the enhanced migration of the migDC subsets induced by the CW NIR laser.

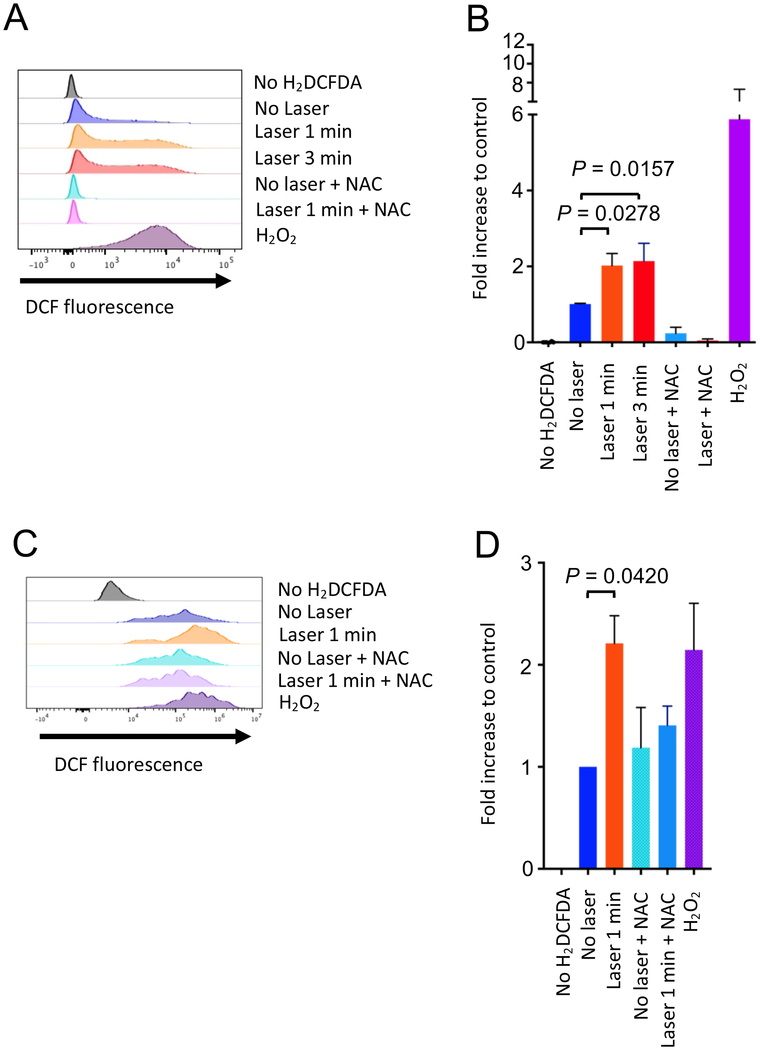

The CW NIR laser induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in cultured MCs and keratinocytes

Exposure of skin to NIR light has been reported to induce generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the skin tissue (44–47). In turn, ROS have been shown to modulate the function of MCs (48). We therefore investigated if the CW NIR laser induces ROS generation in MCs using an established culture model of BMMCs (49) and a ROS-sensitive fluorescence probe H2DCFDA (50). In addition, in light of the fact that ROS can travel across cell types in the tissue (51), we evaluated ROS generation in primary cultured keratinocytes.

After confirming the maturity and purity of BM-derived cells by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. S1A–B), cultured BMMCs were treated with the CW NIR laser for 1–3 minutes in vitro. ROS-reacted DCF-dependent fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. Hydrogen peroxide-treated cells served as a positive control. DCF-fluorescence positive population was identified in the no laser-treated control cells (Fig. 3A–B), indicating that this system could detect constantly generated ROS through aerobic metabolism (52). An addition of an ROS scavenger, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), significantly reduced DCF+ cells, confirming the constant generation from the control cells (Fig. 3A–B). The CW NIR laser treatment significantly increased the ROS-related DCF+ population in BMMCs (Fig. 3A–B, 2.0 folds for 1 minute: P = 0.0278; 2.1 folds for 3 minutes: P = 0.0157) compared to the no laser-treated control group. These data demonstrate that the CW NIR laser induces ROS generation in MCs. The CW NIR laser treatment also increased the ROS-related DCF+ population in keratinocytes compared to the no laser-treated control group (Fig. 3C–D, P = 0.0420). This result indicates that keratinocytes could serve as a source of ROS for MCs in response to the CW NIR laser in skin.

Figure 3. Effect of the NIR laser on cultured MCs and keratinocytes.

A–B, The effect of the NIR laser on MCs. A, Release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the NIR laser treatment was assessed using a ROS-sensitive fluorescence probe H2DCFDA in BMMCs in vitro. The differentiated BMMC culture was treated with the NIR laser at a power of 0.5 W/cm2 for 1–3 minutes. ROS-activated DCF-fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. B, Fold increase in DCF+ population compared to no laser-treated control was calculated for each experiment. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD tests. n= 6, 8, 12, 7, 6, 6, 6 for no H2DCFDA control, no laser control, CW 1064 nm for 1 minute, CW 1064 nm for 3 minutes, no laser control with NAC, CW 1064 nm for 1 minute with NAC, H2O2-treated positive control groups, respectively. Results were pooled from 3 independent experiments. C–D, The effect of the NIR laser on primary cultured keratinocytes. C, Release of ROS in primary cultured human dermal keratinocytes in response to the CW NIR laser at a power of 0.5 W/cm2 for 1 minute was assessed in vitro as described above. D, Fold increase in DCF+ population compared to no laser-treated control was calculated. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD tests. n= 3 each for no H2DCFDA control, no laser control, CW 1064 nm for 1 minute, no laser control with NAC, CW 1064 nm for 1 minute with NAC, H2O2-treated positive control groups, respectively. Representative data from 2 independent experiments are presented.

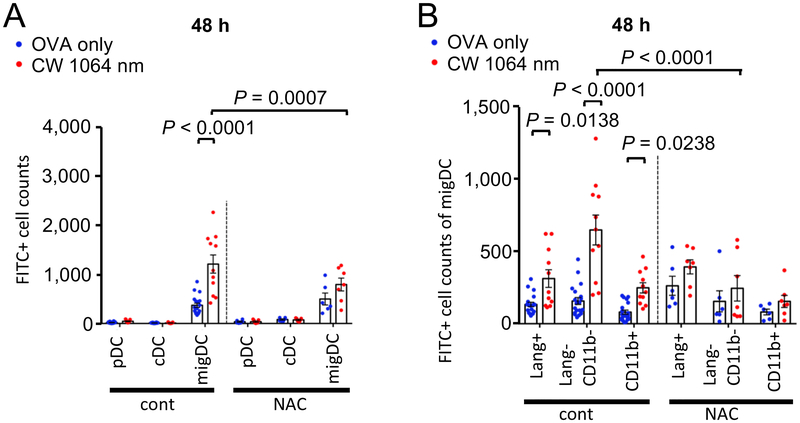

ROS generation with the CW NIR laser mediates the augmentation of migDC migration

To assess the functional link between the ROS generation and augmentation of the migDC migration induced by the CW NIR laser, we pre-treated mice by subcutaneous injections of NAC to suppress ROS generation in response to the CW NIR laser in skin (22) prior to measurements of DC migration using the FITC paint technique.

The NAC treatment significantly attenuated the effect of the CW NIR laser on the migration response of the migDC population (Fig. 4A) and migDC subsets (Fig. 4B), although a comparable level of the migration responses in the ID only groups of NAC-treated mice to that of no-NAC treated control mice was observed. The migration response of the CW NIR laser treated group in NAC treated mice was significantly smaller than that in no-NAC treated mice (Fig. 4A, migDC: P = 0.0007, Lang−CD11b−: P < 0.0001).

Figure 4. The impact of ROS deletion on DC migration enhanced by the NIR laser.

The effect of ROS deletion on the migration response of DCs to the NIR laser in skin. Mice were treated with subcutaneous injection of 100 mg/kg NAC daily for 4 consecutive days before vaccination and the NIR laser treatment as appropriate. Mice were painted with 0.5 % FITC solution on the flank skin 4 hours before vaccination with 40 μg of OVA with or without the NIR laser treatment. Cell counts of A, DC subsets, B, migDC subsets in the skin-dLN 48 hours after OVA vaccination are shown. Results were pooled from 4 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. n= 20, 11, 6, 7 for OVA only in WT, CW 1064 nm in WT, OVA only in NAC-treated and CW 1064 nm in NAC-treated groups, respectively. Data of the control group from Fig. 2 are shown for comparison.

These results suggest that ROS generation in response to the CW NIR laser enhances migration of migDCs in skin.

ROS generation and migDC migration mediate the adjuvant effect of the CW NIR laser

Our data suggest that ROS generation followed by migration of the migDCs plays a pivotal role in the effect of the CW NIR laser. In order to probe the contribution of ROS generation upon the CW NIR laser treatment to the formation of the adaptive immune response, we next treated mice with NAC prior to vaccination and examined the alteration of the immune response to the intradermal influenza vaccination.

The NAC treatment slightly increased a level of IgG responses as well as IgG2c:IgG1 ratios across the experimental groups, but none of these increases was significant compared to that in no-NAC treated control mice (Fig. 5A–D). A level of antibody titers in the CW NIR laser group was not higher than that in the ID only group in NAC-treated mice, while an increased level of the antibody response was observed in the CW NIR laser group compared to that in the ID only group in no-NAC treated control mice (Fig. 5A–C), indicating that ROS generation is involved in the adjuvant effect of the CW NIR laser.

Figure 5. The impact of ROS-deletion or selective ablation of DC subpopulations on the immune responses augmented by the NIR laser.

The effect of NIR laser on the immune response to the intradermal influenza vaccination was evaluated in NAC-treated mice or Ccr7−/− and Batf3−/− mice. For antioxidant treatment, mice were treated with NAC for 4 consecutive days before vaccination and the NIR laser treatment as described above. Serum anti-influenza specific A, IgG, B, IgG1, C, IgG2c, D, IgG2c/IgG1 ratio 4 days after challenge are shown. P values for the tests of treatments within the WT genotype were based on a one-way between subject ANOVA of the WT data with Tukey post hoc tests, whereas those for other comparisons are based on a two-way Treatment by Genotype ANOVA with Tukey tests. e–f, Systemic anti-influenza specific T-cell responses measured in re-stimulated splenocytes upon influenza vaccination. Levels of E, IFN-γ and F, IL-4 in supernatants are shown. A–D, n=44, 48, 38, 33, 25, 11, 12, 11, 14, 14, 3, 8, 9, 9, 3, 6, E–F, n= 35, 39, 30, 24, 16, 11, 12, 11, 14, 14, 3, 8, 9, 9, 3, 6 for no vaccine, vaccine ID only, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm, vaccine ID + PW 1064 nm, vaccine IM, vaccine ID only in NAC-treated, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in NAC-treated and vaccine ID + PW 1064 nm in NAC-treated groups, vaccine ID only in Ccr7−/−, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in Ccr7−/−, vaccine ID + PW 1064 nm in Ccr7−/−, vaccine IM in Ccr7−/−, vaccine ID only in Batf3−/−, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in Batf3−/−, vaccine ID + PW 1064 nm in Batf3−/−, and vaccine IM in batf3−/groups, respectively. A–F, WT data from Fig. 1 are shown for comparison. Results were pooled from 6 independent experiments. G–H, The effect of the NIR laser on protection. G, Kaplan-Meier survival plots. H, The effect of the NIR laser on body weight following viral challenge. Body weights were monitored daily for 15 days. Mean body weight ± s.e.m. of each experimental group was determined at each time point. G–H, n=10, 12, 13, 4, 5, 8 for no vaccine in WT, vaccine ID only in WT, vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in WT, no vaccine in Batf3−/−, vaccine ID only in Batf3−/− and vaccine ID + CW 1064 nm in Batf3−/− groups, respectively. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Results were pooled from 3 independent experiments. WT data from Fig. 1 are shown for comparison.

Our data earlier confirmed the causal link between ROS generation and enhanced migration of the migDC subsets in skin in response to the CW NIR laser. In addition, we have previously demonstrated that the Lang+ DC subset mediates migration of the Lang−CD11b− DC subset in response to the CW NIR laser using the Lang-DTR mouse model (20). However, this model cannot specify the distinct roles of epidermal Langerhans cells and Lang+ dermal DCs in the effect of the CW NIR laser. To further evaluate the contribution of the migration of the migDC subsets via ROS generation to the adjuvant effect, we determined the alterations of the immune response to ID vaccination in Batf3 deficient (Batf3−/−) mice. Batf3−/− mice lack the cross-presenting CD103+ DC subset in skin, which is included in Lang+ dermal DCs (53, 54), in mice with the C57BL/6 background (55). Batf3−/− mice have been therefore used to test the contribution of the CD103+ migDC subset in several models of skin infection (56, 57). Ccr7 loss in Ccr7 deficient (Ccr7−/−) mice inhibits trafficking of migDC populations from the peripheral tissue (58, 59). The immune response in Ccr7−/− mice was also examined as a control in these experiments to confirm the importance of migDCs in the formation of the adaptive immunity to ID vaccination. In addition, we compared the immune responses between ID and intramuscular (IM) vaccination in these genetic mouse models to assess the contribution of the migDC subsets to the immune response augmented with the treatment of skin with the CW NIR laser.

Consistent with the previous report (20), Ccr7−/− mice receiving an ID vaccine showed a significant reduction in anti-influenza IgG and IgG2c (Fig. 5A, 5C, WT vs. Ccr7−/− in the ID only group: P < 0.0001) with similar IgG2c:IgG1 ratios compared to WT mice (Fig. 5D). In addition, IFN-γ influenza-specific splenocyte responses in Ccr7−/− mice were significantly reduced, as compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 5E, WT vs. Ccr7−/− in the vaccine ID only group: P < 0.0001, WT vs. Ccr7−/− in the CW NIR laser group: P < 0.0001). A level of antibody responses in the CW NIR laser group in Ccr7−/− mice showed a significant reduction for IgG (Fig. 5A, P < 0.0001) and statistically marginal reduction for IgG2c (Fig. 5C, P = 0.0693) compared to that in WT mice. These results support dependence of the response to the ID vaccination with or without the CW NIR laser treatment on migDC, as Ccr7−/− mice lack CCR7-dependent migration of migDCs (59).

Interestingly, a level of antibody titers in the CW NIR laser group was not higher than that in the ID only group in Batf3−/− mice, while a comparable level of the antibody response of the ID only and CW NIR laser groups in Batf3−/− mice to that of the ID only group in WT mice was observed (Fig. 5A–C). A slight increase in a level of IgG1 responses (Fig. 5B) with a decrease in IgG2c:IgG1 ratios (Fig. 5D) across the experimental groups in Batf3−/− mice was observed, which is consistent with the previous reports showing that the CD103+ DC subset is critical for TH1 immunity (54). None of these changes were significant compared to that in WT mice. These results indicate that Batf3−/− mice were able to mount the comparable response to WT mice to ID vaccination, but they were not able to respond to the CW NIR laser.

IFN-γ influenza-specific splenocyte responses were reduced in Batf3−/− mice as compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 5E, WT vs. Batf3−/− in the vaccine ID only group: P < 0.0001; in the CW laser group: P < 0.0071), while IL-4 responses were not significantly changed (Fig. 5F). In contrast, IM administration of the same dose of the vaccine mounted a comparable level of anti-influenza antibody responses across the IgG subclasses among WT, Ccr7−/− and Batf3−/− mice (Fig. 5A–C), highlighting a critical role of the dermal CD103+ DC subset in the effect of the CW NIR laser on the antibody response in the context of the ID vaccination. These results collectively demonstrate that the dermal CD103+ DC subset is critical to the adjuvant effect of the CW NIR laser, as opposed to epidermal Langerhans cells playing a predominant role in the adjuvant effect of the visible PW laser adjuvant (15).

We next assessed the contribution of the dermal CD103+ DC subset to protection augmented by the CW NIR laser. Mice were challenged intra-nasally with homologous live influenza virus and monitored for survival time as described above. The survival rate of unvaccinated Batf3−/− mice was lower than that of WT mice (Fig. 5G, P = 0.0134), showing a critical role of the dermal CD103+ DC subset in host defense (55). Consistent with the antibody response study (Fig. 5A–C), the survival rate in the CW NIR laser in Batf3−/− mice was significantly lower than that in WT mice (Fig. 5G, WT vs. Batf3−/− in the CW NIR laser group: P = 0.0003) with greater weight loss upon viral challenge (Fig. 5H), suggesting that the beneficial effect of the CW NIR laser on protection against lethal influenza virus challenge observed in WT mice was attenuated in Batf3−/− mice. These results confirm an important role of the CD103+ migDC subset in the beneficial effect of the CW NIR laser on protection.

In conclusion, these results support the view that ROS generation in response to the CW NIR laser modulates the MC function and enhances the migration of the CD103+ migDC subset in skin, ultimately augmenting the immune response to ID vaccination.

The CW NIR laser induces functional changes in microcirculation in skin

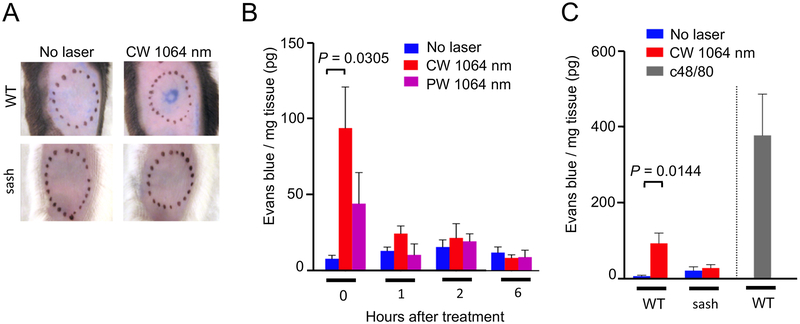

MCs have been shown to induce functional changes in microcirculation via their secretory responses, regulating vascular flow and permeability, and recruitment of inflammatory cells (31). We therefore hypothesized that the CW NIR laser establishes an immunostimulatory milieu to augment protective immune responses in microcirculation in skin via MC activation. To test this hypothesis, we first measured microvascular permeability in the skin tissue treated with the CW NIR laser in WT and MC-deficient sash mice.

The CW, but not PW, NIR laser treatment increased microvascular permeability immediately after the treatment (Fig. 6A–B, the no laser treated vs. laser-treated group at 0 hour: P = 0.0305). The increase in microvascular permeability was no longer observed 1 hour after the treatment, suggesting that the effect of the NIR laser on microvascular permeability resolved within 1 hour. The PW NIR laser did not induce applicable increase, which confirms that heat generation in skin plays a minimum role in the functional changes induced by the CW NIR laser. To investigate the role of MCs in the transient increase in microvascular permeability, we further assessed the effect of the CW NIR laser in sash mice. No increase in microvascular permeability was observed in sash mice (Fig. 6C), demonstrating that the increase in microvascular permeability induced by the CW NIR laser was mediated by MCs.

Figure 6. The effect of the NIR laser on microvascular permeability in skin.

The effect of the NIR laser treatment on microvascular permeability in skin. A, Representative images of the mouse back skin 30 minutes after intravenous injection of Evans blue are shown. B, Quantification of tissue concentration of Evans blue 0, 1, 2 and 6 hours after the 1-minute CW or PW NIR 1064 nm laser treatment is shown. n= 8, 12, 6 for no laser, CW 1064 nm, PW 1064 nm groups at 0 h, and n= 3, 3–4, 3–4 for no laser, CW 1064 nm, PW 1064 nm groups at 1, 2 and 6 hours, respectively. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. C, The effect of the NIR laser on microvascular permeability in skin in WT and sash mice. Quantification of tissue concentration of Evans blue 0 hour after the 1-minute CW NIR 1064 nm laser treatment in WT and sash mice is shown. n= 8, 12, 3, 5, 5 for no laser in WT, CW 1064 nm in WT, no laser in sash, CW 1064 nm in sash, c48/80 in WT mice groups, respectively. Two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD tests. WT data of the no laser group at 0 hour from Fig. 6B are shown for comparison. A–C, Results were pooled from 3 independent experiments.

The endothelial dysfunction caused by damage may induce an increase of microvascular permeability (60). The laser parameter for the CW NIR laser treatment used in this study has been demonstrated to be non-tissue damaging in our previous studies (18–20). Consistently, the laser treatment did not significantly increase the number of TUNEL+ cells in skin (Supplementary Fig. S2).

These results confirm that the CW NIR laser activates MCs and induces functional changes in microcirculation in skin.

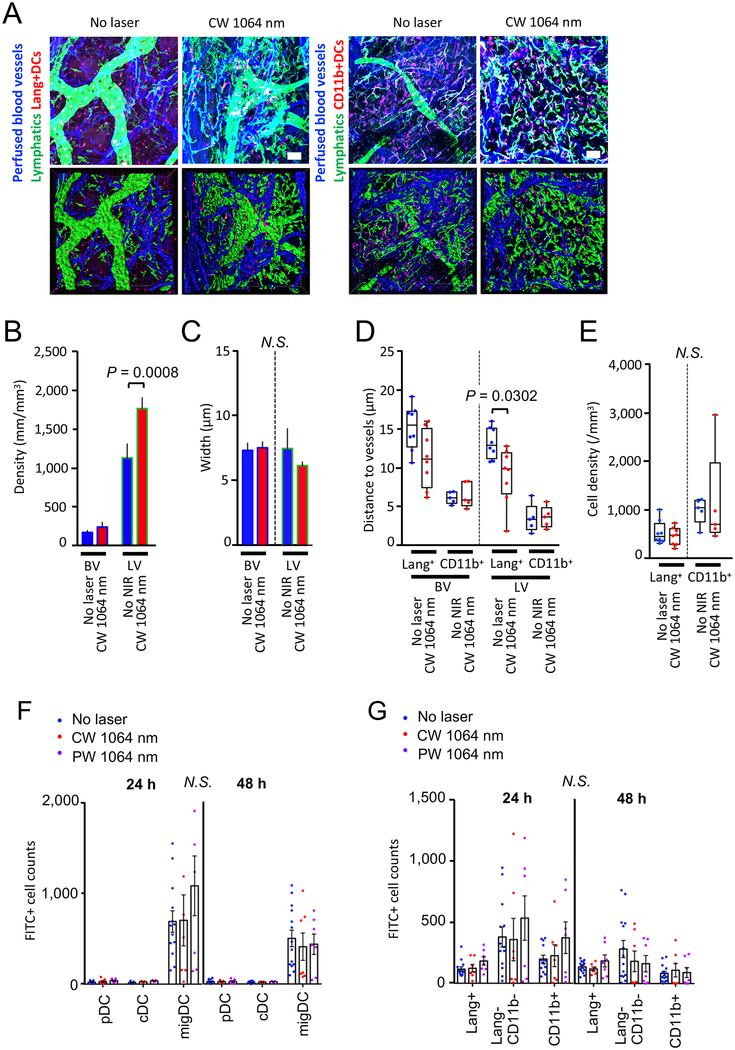

The CW NIR laser induces morphological changes in lymphatic vessels and migration of migDCs to the lymphatics

Microcirculation including blood vessels and the lymphatic network plays an indispensable role in recruitment of immune cells to inflammatory sites, transportation of pathogenic antigens into dLN, and migration of antigen presenting and effector cells to secondary lymphoid organs (61). We next determined the response of the vascular and lymphatic networks in skin to the CW NIR laser without vaccination. Mice received exposures of the CW NIR laser on the ear skin tissue at 5.0 W/cm2 for 1 minute. Six hours later, we performed immunofluorescence of the whole-mount ear tissue and stained the lymphatic network and skin-resident DCs for analysis by confocal imaging.

The CW NIR laser treatment increased the density of the lymphatic network (Fig. 7A–C, the no laser treated vs. laser-treated group for lymphatic density: P = 0.0008), suggesting increased lymphatic flow in the laser-treated tissue, which is typically induced by an increase in microvascular permeability (62). Interestingly, this functional change was accompanied by a concomitant decrease in the distance between lymphatic vessels and Lang+, but not CD11b+, DCs (Fig. 7D, the no laser treated vs. laser-treated group for Lang+ DC: P = 0.0302), indicating that the functional changes in the lymphatics provided migration cues for skin-resident DCs. The CW NIR laser treatment without vaccination induced no change in the number of migDCs in the treated skin (Fig. 7E) nor in skin-dLN, which was examined using FITC painting technique (Fig. 7F–G), suggesting that antigen challenge is necessary to induce the migDC migration into LN (63).

Figure 7. The effect of the NIR laser on microcirculation and DC migration without antigen challenge in skin.

A–E, Morphometry of the vascular and lymphatic networks in skin with or without the NIR laser treatment. Morphological changes of the vascular and lymphatic networks in skin were measured in stacks of the 3D confocal images using Imaris software. The depilated mouse ears were treated with the NIR laser, and the whole-mount ear tissue was stained and imaged for blood vessels, lymphatics, and DC subsets 6 hours after the treatment. A, Representative confocal images of mouse ear stained for blood vessels, lymphatics and DCs 6 hours following the CW NIR laser treatment. Bar = 40 μm. B–C, Morphometry of blood and lymphatic vessels and DCs in skin using Imaris software. Two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD tests. a–c, n= 17, 17 for nor laser control and CW NIR laser-treated groups, respectively. D, Distances between vasculature and DCs, E, Density of Lang+ and CD11b+ DCs in skin. n= 5–8, 5–8 for no laser control and CW NIR laser-treated groups, respectively. Two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD tests. A–E, Results were pooled from 5 independent experiments. F–G, The effect of the NIR laser on the migration response of migDC subsets without antigen challenge in skin. Mice were painted with a 0.5 % FITC solution on the flank skin 4 hours before the NIR laser treatment without any antigen challenge. Cell counts of F, DC subsets G, migDC subsets in the skin-dLN 24 and 48 hours after FITC painting are shown. F–G, n= 13–14, 7, 7 for no laser, CW 1064 nm, PW 1064 nm groups, respectively. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. Results were pooled from 4 independent experiments.

Together, these results demonstrate that the CW NIR laser induces functional changes in the lymphatic network and provides migration cues for skin-resident DCs toward the lymphatics in skin.

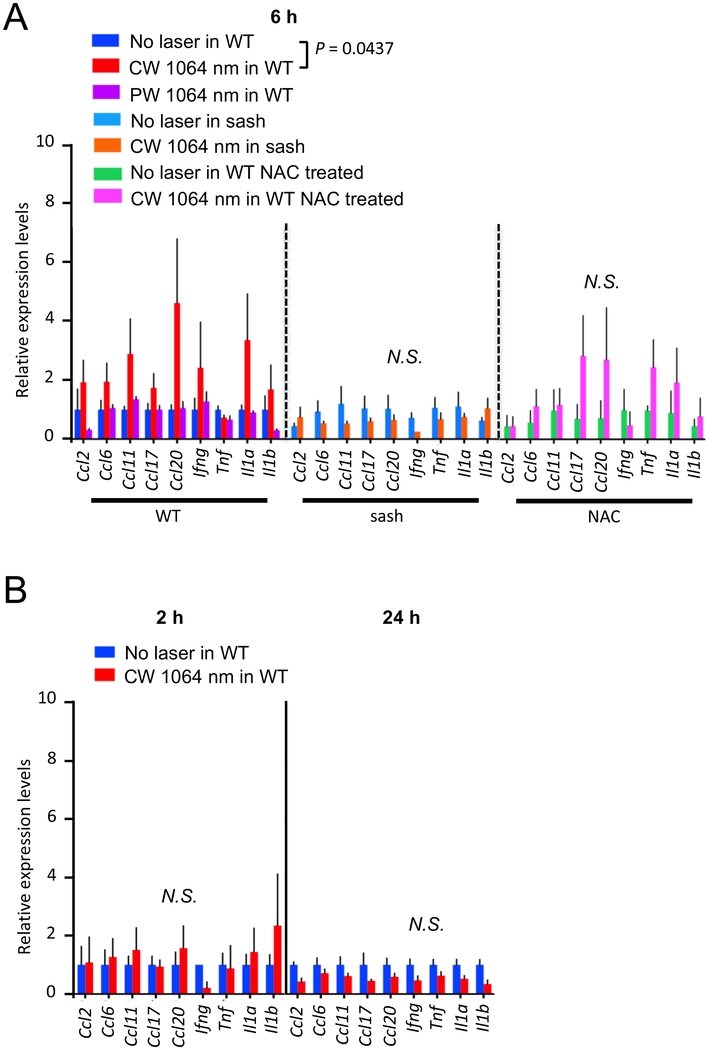

The CW NIR laser induces a selective set of chemokine upregulation in skin

The CW NIR laser appears to induce a transient increase in microvascular permeability and lymphatic flow, which is consistent with the tissue changes upon MC activation (64). Chemical agents which are designed to stimulate MC function generally induce prolonged and exacerbated inflammatory responses (65). In contrast, exposures of skin to low-power CW NIR laser have been shown to be free from tissue damage or inflammation evidenced by no polymorphonuclear infiltration (18–20) with upregulation of a selective set of chemokines (19). We therefore hypothesized that the CW NIR laser induces “differential” or “selective” secretion of mediators without degranulation of MCs (66, 67). In order to test this hypothesis, we assessed expression of a selective set of chemokines, which was established previously (19), as well as inflammatory cytokines in WT and MC-deficient sash mice.

The CW, but not PW, NIR laser treatment induced temporary expression of the selective chemokines at 6 hours. Student’s t test with stepdown bootstrap and false discovery rate corrections showed that none of the 9 selected chemokines and cytokines of importance predicted the effect of the NIR laser treatment significantly. However, a multivariate discriminant analysis which tests the linear combination of the 9 genes which optimally discriminates the treatments found a significant treatment effect in WT mice (Fig. 8A, the no laser treated vs. laser-treated group in WT: P = 0.0437, Supplementary Fig. S3). Consistent with the previous report (19), no upregulation of inflammatory cytokines including Tnf and Il1b was observed. This change appeared to be transient in nature, as the upregulation of the genes of interest was not observed at 2 or 24 hours (Fig. 8B). Importantly, no significant increase in the selective chemokine expression was observed in sash mice with the CW NIR laser treatment (Fig. 8A), suggesting that these changes in chemokine expression were dependent on MCs.

Figure 8. A critical role of MCs and ROS in the chemokine expression in skin in response to the NIR laser.

The effect of the NIR laser on the chemokine expression in skin was evaluated in WT and sash mice. The role of ROS in the chemokine expression in skin in response to the CW NIR laser was also evaluated in NAC-treated WT mice. For antioxidant treatment, mice were treated with NAC for 4 consecutive days before the NIR laser treatment as described above. A, The expression of chemokines in the mouse back skin was measured 6 hours following the CW NIR laser treatment in (left) WT, (middle) sash, and (right) NAC-treated WT mice using qPCR. n = 7, 7, 4, 3, 3, 3, 3 for no laser control in WT, CW and PW 1064 nm laser-treated in WT, no laser control in sash, CW 1064 nm laser-treated in sash, NAC-treated only, CW 1064 nm in NAC-treated groups, respectively. B, The expression of chemokines in the mouse back skin in (left) 2 and (right) 24 hours after the NIR laser treatment in WT mice. n = 4, 4 at 2 hours and n = at 24 hours for no NIR, CW 1064 nm groups. A–B, Student’s t test with stepdown bootstrap and false discovery rate corrections followed by a multivariate discriminant analysis of the 9 genes was used as appropriate. Error bars show means ± s.e.m.

Our data suggest that ROS generation plays a critical role in the adjuvant effect of the CW NIR laser. In order to explore the possible causal link between ROS generation upon the CW NIR laser treatment and chemokine expression, we next treated mice with NAC and examined the alteration of the chemokine response. The NAC treatment attenuated the effect of the CW NIR laser on expression of the selective set of chemokines (Fig. 8A), indicating that ROS generation mediates the chemokine expression in skin.

To further uncover pathways involved in the ROS generation and chemokine responses, we treated cultured BMMCs or keratinocytes with the CW NIR laser and measured expression of the selective set of chemokines in BMMCs or evaluated an expression array of inflammatory cytokines and receptors in keratinocytes in vitro. Except a slight increase noted in Ccl11, Ccl17 and Ccl20 in BMMCs, no significant change was observed in the other chemokines in BMMCs or 84 genes examined on the array in keratinocytes (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results suggest that the skin microenvironment or collaboration among skin cells is essential to orchestrate the response to the CW NIR laser.

Together, these results further support the view that the CW NIR laser induces transient and selective activation of MCs, possibly in concert with other types of skin cells, via ROS generation.

The CW NIR laser induces CCL21 upregulation in the lymphatics

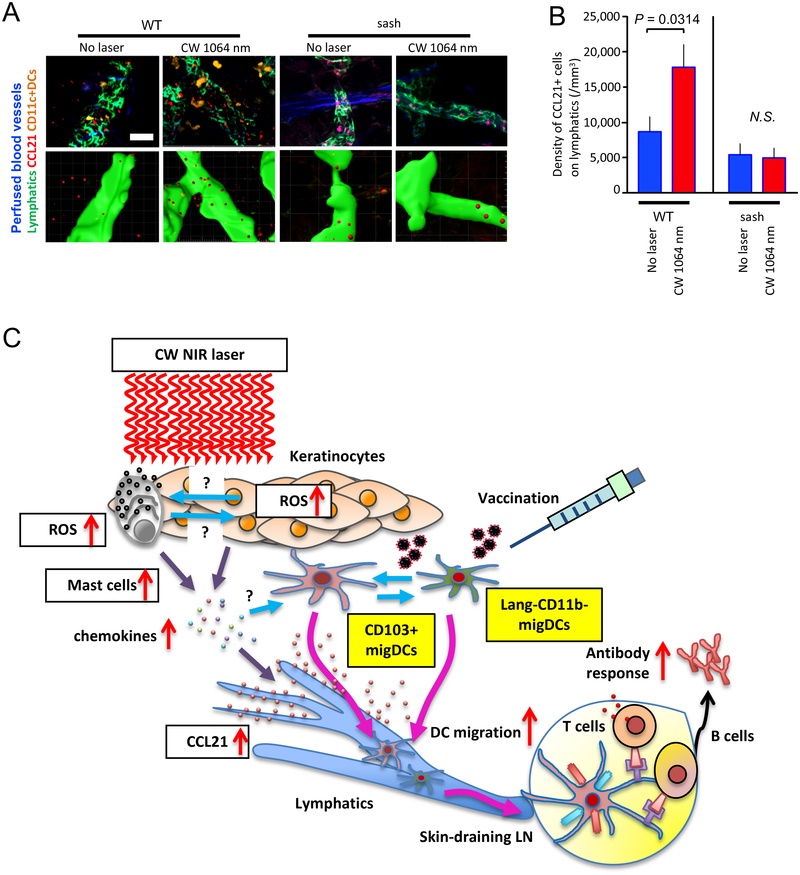

Migration of DCs is a critical step for the initiation of protective immune responses (61). In response to inflammatory stimuli, the lymphatic network is known to increase expression of CCL21 on lymphatic vessels, triggering migration of skin-resident DCs (68, 69). Since our earlier observations showed that the CW NIR laser induced migrational changes of migDCs, we further hypothesized that the immunostimulatory milieu established by the selective activation of MCs with the CW NIR laser induces CCL21 response in the lymphatics. To test this hypothesis, we performed immunofluorescence of CCL21 and the lymphatic network in the mouse ear tissue exposed to the CW NIR laser for analysis by confocal imaging. In order to evaluate the contribution of MCs, we also assessed CCL21 response in MC-deficient sash mice.

CCL21 expression on Lyve-1+ lymphatics was distributed among small patch structures in the control and exposed skin tissue (Fig. 9A), as previously reported (70). Image analysis revealed an increase in the density of CCL21+ cells in the exposed skin tissue compared to the non-exposed control tissue (Fig. 9B, P = 0.0314), which appeared to mediate the chemotaxis of migDCs to lymphatic vessels. Importantly, the effect of the CW NIR laser on the CCL21 response was not observed in sash mice (Fig. 9A–B). In the current study, we have shown that ROS are generated in MCs and keratinocytes in response to the CW NIR laser (Fig. 3A–D). Thus, it is possible that ROS from various sources in skin directly stimulate lymphatic endothelial cells and induce CCL21 expression. However, these data indicate that MCs are required for the up-regulation of CCL21 in response to the CW NIR laser and that mediators derived from activated MCs via ROS generation are critically involved in the CCL21 upregulation.

Figure 9. The effect of the NIR laser on CCL21 expression on the lymphatics in skin.

Quantification of CCL21 expression on the lymphatics in stacks of the 3D confocal images using Imaris software. The depilated mouse ears were treated with the NIR laser, and the whole-mount ear tissue was stained and imaged for the lymphatics and CCL21 6 hours after the treatment. A, Representative confocal images of CCL21 immunofluorescence are shown. Bar = 40 μm. B, Quantification of CCL21+ cells on Lyve-1+ lymphatic vessels is shown. n= 6, 6, 3, 3 for no laser control in WT (CD11c-EYFP), CW 1064 nm laser-treated in WT (CD11c-EYFP), no laser control in sash, CW 1064 nm in sash groups, respectively. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD tests. Results were pooled from 3 independent experiments.

In summary, these results show that the CW NIR laser induces CCL21 expression in the lymphatics in skin via MC activation and confirm our earlier observations that the CW NIR laser provides migratory cues for migDCs.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown for the first time that CW NIR laser with a distinct power and dose has a unique capability to reproducibly activate selective innate programs including MC function and migDC migration via ROS generation without inducing prolonged and potentially harmful inflammatory responses in skin, thus augmenting the adaptive immune response (Fig. 9C). These mechanistic findings would significantly contribute to optimization of wavelength, power, duration of the treatment, the timing and location of delivery, and the size of the treatment spot on the skin of a CW NIR laser adjuvant in the context of intradermal vaccination for better safety and efficacy of this technology.

Although other medical PW lasers have been similarly reported to show the adjuvant effect to intradermal vaccines (10, 11), use of CW NIR laser has clear advantages over the other classes of lasers. Current clinical grade PW laser systems in these reports are typically large in size, complicated in machinery to generate PW, and expensive, posing financial and engineering challenges including high cost per unit and needs of maintenance by laser specialists. In contrast, the low-wattage CW NIR lasers are a mature and simple technology, and a small device emitting CW NIR laser at the required powers used in this application (5 W/cm2 and below) proved to be economically produced (18), making this technology feasible and suitable for mass-vaccination programs and other clinically applicable approaches.

In this study, we have shown that ROS generation in MCs is critical for the effect of the CW NIR laser. There are ample evidences showing that NIR light induces generation of ROS in exposed tissue or cells. Low power (1 mW–5 W/cm2) NIR light between 600–1000 nm has been established to show diverse beneficial effects in exposed tissue including pain relief, facilitation of tissue regeneration, reduction of the inflammation. These biological effects of NIR light are broadly defined as photobiomodulation (44, 71–76). Although the precise mechanisms of action for photobiomodulation are still under debate (44, 75–77), it is clear that the effect of NIR light is partially, if not entirely, mediated by ROS (44, 73–76). In turn, there is ample evidence showing that NIR light induces generation of ROS in exposed tissue or cells. Exposures to NIR light between 760–1400 nm have been shown to increase ROS generation in tumor cells (78–80), keratinocytes (79), fibroblasts (81), the skin tissue (46, 47, 82). In contrast to photobiomodulation, ROS generation upon exposure to NIR light has been rather linked to deleterious effects including premature skin aging (83, 84) and the cytotoxic effect (85, 86). Beneficial or deleterious, ROS have been postulated to be generated by mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase in respiratory electron transport chain in response to NIR light exposure (87, 88), ultimately activating NF-κB signaling pathway and innate signaling (44, 73–75). On the other hand, the numerous reliable data have reported that ROS play a significant role in MC-dependent inflammatory processes and activation of intracellular signaling for production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that regulate the innate immune response (48, 89). In accordance, we found that the CW NIR laser induced ROS generation in MCs (Fig. 3), and that the effects of the CW NIR laser on the migration of migDCs and the adaptive immune response are functionally dependent on ROS generation (Fig. 4–5). In addition, in the absence of MCs, we observed no up-regulation of the selective set of chemokines (Fig. 8) nor subsequent augmentation of the immune response by the CW NIR laser (Fig. 1). These results clearly indicate that MCs locate at an intersection between the adaptive immune response and ROS generation in response to the CW NIR laser. However, the precise mode of action for the MC activation via ROS generation upon the CW NIR laser treatment has yet to be defined. For example, it is possible that ROS generated in adjacent cells reach MCs in skin, modulating MC function indirectly, as ROS are small enough to travel across cell types in tissues (51). Further studies are warranted to determine the precise molecular identify of ROS, subcellular localization of ROS generation, spatial and temporal dynamics of ROS distribution in tissues, and the mode of activation of innate signaling pathways by ROS in response to the CW NIR laser treatment to selectively activate MCs and induce the specific immunomodulatory effect without deleterious inflammation.

Our data collectively demonstrate that there are distinct differences in the immunological effect between CW and PW NIR lasers. Although both CW and PW NIR lasers have been reported to induce ROS generation in the biological system (46, 47, 78–82, 90, 91), the exact molecular identify, temporal distribution or local concentration of ROS leading to the immunological events in response to the NIR lasers have not been characterized. PW NIR laser has been shown to be more effective in ROS generation (90, 91) and photobiomodulation (92, 93) than CW in some biological systems. Since the pulse frequency, power level and exposure time of NIR laser can dictate a level of ROS generation in tissues (90, 91), we might be able to identify a parameter of PW NIR laser for the desired immunological effect. Nonetheless, in the current study, nanosecond-pulsed 1064 nm laser at a frequency of 10kHz did not show any significant immunological effect, suggesting that this particular parameter is suboptimal in inducing proper ROS generation for the subsequent immunological events. An optimal parameter of PW NIR laser might be sought for in the context of the molecular identify, local sources, and subcellular localization of ROS in response to the NIR laser ultimately leading to efficient activation of innate signaling in the future study.

Infrared (IR) irradiation and heat generation in exposed tissues have been linked to biological effects including premature skin aging via expression of MMP-1 or generation of ROS (94). Accordingly, heat generated by NIR exposures could have a predominant role in MC activation and augmentation of the immune response. In fact, MCs are capable of responding to physical stimuli through transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, which are functionally coupled to calcium signaling and regulate mediator release in MCs (42). Moreover, TRPV channels have been shown to respond to IR radiation (41). However, our study shows that a thermal mechanism is not a major driver of the impact of the NIR laser on the immune system. As the CW and PW 1064 nm lasers in this study were emitted from the same platform with the same wavelength and average power, they proved to have the same heat generation profile in skin (19). Despite the same thermal profile, the PW NIR laser has shown little impact on MC function in skin (Fig. 6), if any, resulting in the marginal effect on the immune response (Fig. 1) (20). It is still possible that heat is required for the CW NIR laser to have these effects, as one study shows that water-filtered NIR light between 760–1400 nm induces ROS generation in a temperature-dependent manner (82). Nonetheless, our data support the view that heat alone is not sufficient to induce the subsequent immunological events and that specific photochemical events related to the CW NIR laser exposure are required for these effects.

Cytokines and chemokines are released by MCs, keratinocytes, DCs, melanocytes, tissue-resident macrophages, and inflammatory infiltrates in skin (95). The cutaneous cytokine and chemokine network is critically involved in regulation of skin functions as well as inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis (95–98). Due to their anatomical proximity, collaborative activities between MCs and keratinocytes via cytokine and chemokine signaling have been reported in coordinating cell proliferation and differentiation (96, 99–102) and the immune response and inflammation (95, 103). The chemokines and their receptors up-regulated in response to the CW NIR laser have been reported to be expressed in both MCs (103) and keratinocytes (95, 104) under certain conditions. In the current study, we have shown that the chemokine response to the CW NIR laser in the mouse skin is dependent on ROS generation and MCs (Fig. 8). Although ROS generation was observed in cultured BMMCs and keratinocytes in vitro (Fig. 3), small changes were detected in the subsequent chemokine expression in the individual culture systems (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results suggest that the chemokine response to the CW NIR laser is dependent on the local skin microenvironment and interactions among MCs, keratinocytes, and possibly other types of cells including fibroblasts in close association with MCs and keratinocytes in skin. Further investigation is warranted to uncover the cross-talk among these cells in the context of regulation of this complex skin chemokine network in response to the CW NIR laser.

Our data show that the CW NIR laser induces a transient increase in microvascular permeability and lymphatic flow, which is consistent with the tissue changes upon MC activation (64). Contrary to chemical agents which are designed to stimulate MC function and may cause prolonged inflammatory responses with off-target effects (65), the low-power NIR exposures of skin are free from tissue damage or inflammation (18–20). This feature may be compatible with “differential” or “selective” secretion of mediators without degranulation of MCs (66, 67). Unlike allergic reactions, MCs have been rarely reported seen to degranulate during inflammatory processes (66, 67). This activation in the non-allergic processes could be explained by selective secretion of mediators without degranulation through a process associated with their ultrastructural alterations (105–108). This hypothesis is further supported by the observations that the CW NIR laser induces a selective set of chemokines without up-regulating inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-1β and that the up-regulation in the exposed skin tissue is dependent on MCs (Fig. 8). Reproducible control of microvascular permeability or lymphatic flow without widespread inflammation by CW NIR laser may offer a desirable approach for other medical purposes including facilitation of drug delivery or the treatment of lymphedema. An optimal parameter of CW NIR laser for such an application is yet to be found and awaits validation in relevant models in the future.

In summary, our results show that CW NIR laser possesses a unique ability to selectively modulate innate responses in skin. These findings built upon mechanistic knowledge of the biological effect of the CW NIR laser would not only significantly contribute to optimization of the NIR laser vaccine adjuvant, but allow exploration of a novel use of this technology for the treatment of immune-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank the Live Cell Imaging Facility, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, the Swedish Research Council, the Centre for Innovative Medicine and the Jonasson Center at the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, and the Collaborative Research Resources, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan for the use of Imaris software, which provided the 3D-confocal image analysis service; Dr. Thomas J. Diefenbach (Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard) for his expert technical assistance with confocal imaging; the Ragon Institute Imaging Core Facility for 3D-confocal imaging; the MGH Department of Pathology Flow and Image Cytometry Research Core for flow cytometry; Madeline Penson and Don Sobell (all in the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital) for their excellent technical assistance and fruitful discussions.

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AI105131 (S.K.), Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science (Y.K.), Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (Y.K.), Uehara Memorial Foundation (Y.K.), Japan Foundation for Pediatric Research (Y.K.), and the VIC Innovation Fund (S.K.), Keio University Special Grant-in-Aid for Innovative Collaborative Research Projects (K.T.), Keio University Research Grants for Global Initiative Research Projects (K.T.), AMED Translational Research Network Program (K.T.). The Live Cell Imaging Facility, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden is supported by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The Ragon Institute Imaging Core Facility is supported in part by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (5 P30 AI060354–10). The MGH Department of Pathology Flow and Image Cytometry Research Core obtained support from the NIH Shared Instrumentation program with grants 1S10OD012027–01A1, 1S10OD016372–01, 1S10RR020936–01, and 1S10RR023440–01A1. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Fehres CM, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Unger WW, and van Kooyk Y. 2013. Skin-resident antigen-presenting cells: instruction manual for vaccine development. Front Immunol 4: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sticchi L, Alberti M, Alicino C, and Crovari P. 2010. The intradermal vaccination: past experiences and current perspectives. J Prev Med Hyg 51: 7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Combadiere B, and Liard C. 2011. Transcutaneous and intradermal vaccination. Hum Vaccin 7: 811–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Icardi G, Orsi A, Ceravolo A, and Ansaldi F. 2012. Current evidence on intradermal influenza vaccines administered by Soluvia licensed micro injection system. Hum Vaccin Immunother 8: 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Principi N, Senatore L, and Esposito S. 2015. Protection of young children from influenza through universal vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother 11: 2350–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young F, and Marra F. 2011. A systematic review of intradermal influenza vaccines. Vaccine 29: 8788–8801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonam SR, Partidos CD, Halmuthur SKM, and Muller S. 2017. An Overview of Novel Adjuvants Designed for Improving Vaccine Efficacy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitoriano-Souza J, Moreira N, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Carneiro CM, Siqueira FA, Vieira PM, Giunchetti RC, Moura SA, Fujiwara RT, Melo MN, and Reis AB. 2012. Cell recruitment and cytokines in skin mice sensitized with the vaccine adjuvants: saponin, incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, and monophosphoryl lipid A. PLoS ONE 7: e40745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Pravetoni M, Bhayana B, Pentel PR, and Wu MX. 2012. High immunogenicity of nicotine vaccines obtained by intradermal delivery with safe adjuvants. Vaccine 31: 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashiwagi S, Brauns T, Gelfand J, and Poznansky MC. 2014. Laser vaccine adjuvants. History, progress, and potential. Hum Vaccin Immunother 10: 1892–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashiwagi S, Brauns T, and Poznansky MC. 2016. Classification of Laser Vaccine Adjuvants. J Vaccines Vaccin 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Shah D, Chen X, Anderson RR, and Wu MX. 2014. A micro-sterile inflammation array as an adjuvant for influenza vaccines. Nature communications 5: 4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Li B, and Wu MX. 2015. Effective and lesion-free cutaneous influenza vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 5005–5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terhorst D, Chelbi R, Wohn C, Malosse C, Tamoutounour S, Jorquera A, Bajenoff M, Dalod M, Malissen B, and Henri S. 2015. Dynamics and Transcriptomics of Skin Dendritic Cells and Macrophages in an Imiquimod-Induced, Biphasic Mouse Model of Psoriasis. J Immunol 195: 4953–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onikienko SB, Zemlyanoy AB, Margulis BA, Guzhova IV, Varlashova MB, Gornostaev VS, Tikhonova NV, Baranov GA, and Lesnichiy VV. 2007. Diagnostics and correction of the metabolic and immune disorders. Interactions of bacterial endotoxins and lipophilic xenobiotics with receptors associated with innate immunity. . Donosologiya (St. Petersburg) 1: 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Kim P, Farinelli B, Doukas A, Yun SH, Gelfand JA, Anderson RR, and Wu MX. 2010. A novel laser vaccine adjuvant increases the motility of antigen presenting cells. PLoS ONE 5: e13776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Zeng Q, and Wu MX. 2012. Improved efficacy of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy by cutaneous laser illumination. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 18: 2240–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimizuka Y, Callahan JJ, Huang Z, Morse K, Katagiri W, Shigeta A, Bronson R, Takeuchi S, Shimaoka Y, Chan MP, Zeng Y, Li B, Chen H, Tan RY, Dwyer C, Mulley T, Leblanc P, Goudie C, Gelfand J, Tsukada K, Brauns T, Poznansky MC, Bean D, and Kashiwagi S. 2017. Semiconductor diode laser device adjuvanting intradermal vaccine. Vaccine 35: 2404–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashiwagi S, Yuan J, Forbes B, Hibert ML, Lee EL, Whicher L, Goudie C, Yang Y, Chen T, Edelblute B, Collette B, Edington L, Trussler J, Nezivar J, Leblanc P, Bronson R, Tsukada K, Suematsu M, Dover J, Brauns T, Gelfand J, and Poznansky MC. 2013. Near-infrared laser adjuvant for influenza vaccine. PLoS One 8: e82899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]