Abstract

Background

Despite its established benefits, palliative care (PC) is rarely utilized for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients. We sought to examine transplant physicians’ perceptions of PC.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of transplant physicians recruited from the American-Society-for-Blood-and-Marrow-Transplantation. Using a 28-item questionnaire adapted from prior studies, we examined physicians’ access to PC services, and perceptions of PC. We computed a composite score of physicians’ attitudes about PC (mean=16.9, SD=3.37) and explored predictors of attitudes using a linear mixed model.

Results

277/1005 (28%) of eligible physicians completed the questionnaire. The majority (76%) stated that they trust PC clinicians to care for their patients, but 40% felt that PC clinicians do not have enough understanding to counsel HSCT patients about their treatments. Most endorsed that when patients hear the term PC, they feel scared (82%) and anxious (75%). Nearly half (45%) reported that the service name ‘palliative care’ is a barrier to utilization. Female sex (β=0.85, P=0.024), having <10 years of clinical practice (β=1.39, P=0.004), and perceived quality of PC services (β=0.60, P<0.001) were all associated with a more positive attitude towards PC. Physicians with a higher sense of ownership over their patients’ PC issues (β=−0.36, P <0.001) were more likely to have a negative attitude towards PC.

Conclusions

The majority of transplant physicians trust PC, but have substantial concerns about PC clinicians’ knowledge about HSCT and patients’ perception of the term ‘palliative care’. Interventions are needed to promote collaboration, improve perceptions, and enhance integration of PC for HSCT recipients.

Keywords: perceptions of palliative care, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), attitudes about palliative care, unmet palliative care needs, barriers to palliative care

Introduction

Patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) face life-threatening diagnoses and experience immense physical and psychological symptoms. Together, these factors contribute to substantial deterioration in quality of life and mood during hospitalization for HSCT.1–7 HSCT survivors also struggle with post-transplant complications, long-term quality of life impairments, and psychological consequences, further exacerbating the morbidity of HSCT.1–4, 6, 8–13 Ultimately, HSCT recipients face complex physical and psychological symptoms that negatively impact their quality of life throughout their difficult and unpredictable illness course.1–4, 6, 8–13

Early integration of specialty palliative care (PC) concurrently with oncology care for patients with advanced cancer has been shown to improve a wide-range of patient-reported outcomes, including symptom burden, quality of life, depression, coping, and illness understanding.14–18 A recent randomized clinical trial also demonstrated that early PC integrated with standard transplant care improves patient reported quality of life, symptom burden, and psychological outcomes, both during the transplant hospitalization and up to six months post-HSCT.19, 20 Despite these benefits, PC is rarely consulted in the care of patients undergoing HSCT.21–23 Cultural barriers and misperceptions of PC likely contribute to the lack of collaboration between HSCT physicians and specialty PC services, but there are little empirical data to support these hypotheses.21–25 To promote PC integration in HSCT, we must have a more comprehensive understanding of transplant physicians’ perceptions of PC and their perceived barriers to PC utilization.

To improve understanding about transplant physicians’ perceptions and attitudes about PC, we conducted a cross-sectional survey, focusing on barriers to PC utilization, and perspectives on unmet PC needs in the HSCT population. We also explored potential predictors of physicians’ attitudes towards PC. We hypothesized that clinical and demographic factors, as well as physicians’ sense of ownership over addressing PC issues, would emerge as important predictors of physicians’ attitudes about PC. These data provide a more comprehensive understanding of transplant physicians’ perceptions of PC, their perceived barriers to its utilization, and a means to integrate PC into future transplant practice.

Methods

Study Procedures

This study was approved by the National Marrow Donor Program Institutional Review Board. We conducted a cross-sectional, web-based survey of transplant physicians. Participants were recruited from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT) membership list between January and February 2017. Eligible participants were transplant physicians who provide direct clinical care to HSCT patients in the United States. Participants were recruited via an email invitation explaining the purpose of the study, which included a link encouraging them to participate through the “Survey Gizmo” platform. Survey-Gizmo (Boulder, CO) is a secure, password protected tool that has been used extensively for survey administration. A total of five follow-up email contacts were made to non-responders, with email reminders sent on the second, third, fifth, and sixth week from the initial invitation. Participants who completed the survey could choose to receive honoraria, via a $50 gift card.

Study Measures

We utilized prior validated instruments that have been used in the broader oncology field and adapted them to develop an HSCT appropriate survey instrument for physicians.26–30 The HSCT survey focused on measuring the following domains: 1) demographics and clinical practice characteristics (14 items); 2) access to and quality of PC services (4 items); 3) physicians’ attitudes towards PC (6 items); 4) physicians’ sense of ownership over PC issues (4 items); 5) physicians’ perceptions of patients’ attitudes towards PC (16 items); 6) barriers to PC utilization (11 items); and 7) perception of unmet PC needs in HSCT (8 items). Questionnaire content was developed and reviewed by the Palliative and Supportive Care Task Force of the ASBMT, which consists of a multidisciplinary team of transplant physicians, palliative care clinicians, nurses, social workers, clergy, former patients, health services researchers, and survey development experts. This interdisciplinary team reviewed the content of the survey items to ensure their readability, interpretability, and applicability to the HSCT setting. Prior to the national launch of the survey, we conducted pilot testing with 6 transplant physicians to ensure the clarity of the content, and refined survey items based on their feedback. The survey is available for public use by contacting the corresponding author on this manuscript.

As per prior studies,26 we generated a composite score for physicians’ attitudes about PC using the 6 items measuring this domain from the HSCT survey. Each item within the physician’s attitude about PC was scored on a Likert scale. We then created a summated composite score of all six items, with higher scores indicated more positive PC perception (range 4–24). Given the focus of this study on measuring physicians’ attitudes about PC, we a priori-defined this domain as the outcome of interest in our secondary analysis.

We also used similar methodology to generate composite scores corresponding to other survey domains that were a priori-defined as potential predictors for physicians’ attitudes about PC. Importantly, items unique to each domain were used to generate composite scores for the following domains: 1) physicians’ sense of ownership over addressing PC issues (with higher scores indicating higher sense of ownership; range 4–16), 3) the extent of collaboration with PC (higher score indicating more collaboration; range 0–6), 4) perceived quality of PC services (higher score indicating better quality; range 0–10), and 5) perceptions of unmet PC needs in the HSCT population (higher score indicating greater unmet needs; range 0–32).

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analyses using SPSS (v19) and SAS Enterprise Guide (V6.1). The primary aims of this study were descriptive in nature. We used descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means +/− standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, to examine participants’ responses to survey items.

We used a linear mixed model adjusting for random effects of transplant center to examine predictors of transplant physicians’ attitudes about PC (main outcome of interest). We included predictors that were defined a priori by the research team, including sex, race, years of clinical practice, importance of spirituality in clinical practice, time dedicated to clinical responsibilities, number of transplants performed at the HSCT center, prior training in PC (categorized as no training vs. attended CME courses & educational lectures vs. rotation and/or 6 months or more of formal training +/− attended CME courses), extent of prior collaboration with PC, perceived quality of PC services, barriers to PC utilization, physicians’ sense of ownership over PC issues, physicians’ perceived expertise in managing patients’ PC needs, and perceptions of the unmet PC needs in HSCT. We assessed for collinearity between all predictors included in the model using Pearson correlation coefficients and found positive collinearity between perceived quality of PC services and the extent of collaboration with PC (r=0.59, P<0.001). Hence, we removed the extent of collaboration with PC from the final model. We considered a P-value of < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Participants Characteristics

Of the 1005 eligible transplant physicians, 277 (28%) completed the survey [Table 1]. Most physicians were White (194/277, 70%), not Hispanic or Latino (255/277, 70%), and male (179/277, 65%). All major regions of the United States were represented [Table 1]. Most physicians (179/277, 65%) provided care to adult HSCT patients. Overall, 36% (101/277) had < 10 years of clinical practice, 29% (80/277) had 10–20 years, and 35% (96/277) had > 20 years in practice. With regards to PC training, 46% (128/277) attended continuing medical education courses and lectures, 37% (102/277) have no PC training, 29% (81/277) reported attending a PC rotation during residency or fellowship, and only 1% (4/277) had six months or more of formal PC training. We do not have data on non-responders or all transplant physicians to compare their characteristics to those of survey responders.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

CME = continuing medical education.

| Participant Characteristics | N (%) N = 277 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Male sex | 179 (65%) |

|

| |

| Latino/Hispanic | 22 (8%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 194 (70%) |

| Asian | 51 (18%) |

| African American | 7 (3%) |

| Other | 19 (7%) |

| Missing | 6 (2%) |

|

| |

| Religion or spiritual practice | |

| None | 72 (26%) |

| Catholic | 54 (19%) |

| Protestant | 51 (18%) |

| Jewish | 39 (14%) |

| Hindu | 26 (9%) |

| Other | 20 (7%) |

| Muslim | 12 (4%) |

| Buddhist | 3 (1%) |

|

| |

| Importance of spiritual practice or religion | |

| Very important | 68 (25%) |

| Somewhat important | 109 (39%) |

| Not very important | 60 (22%) |

| Not at all important | 40 (14%) |

|

| |

| United States region of practice | |

| Midwest | 89 (32%) |

| South Atlantic | 53 (19%) |

| South Central | 50 (18%) |

| Northeast | 33 (12%) |

| Mountain | 27 (10%) |

| Pacific | 25 (9%) |

|

| |

| Years of clinical practice since completing training | |

| <10 years | 101 (36%) |

| 10–20 years | 80 (29%) |

| >10 years | 96 (35%) |

|

| |

| Time dedicated to clinical responsibilities | |

| <30% | 29 (10%) |

| 30–60% | 102 (37%) |

| >60% | 146 (53%) |

|

| |

| What patient age group do you provide care | |

| Adults only | 179 (65%) |

| Pediatrics only | 77 (28%) |

| Adults and Pediatrics | 21 (8%) |

|

| |

| For what patient population do you provide care | |

| Both non-transplant and transplant patients | 159 (57%) |

| Transplant patients only | 118 (43%) |

|

| |

| Board certification* | |

| Hematology | 204 (74%) |

| Oncology | 201 (73%) |

| Other** | 76 (27%) |

| Hospice and palliative medicine | 4 (1%) |

| Pain medicine | 0 (0%) |

|

| |

| For what population does your transplant center provide care? | |

| Adults only | 84 (30%) |

| Pediatrics only | 42 (15%) |

| Adults and pediatrics | 151 (55%) |

|

| |

| Number of adult transplants performed at your center | |

| <50 total transplants per year | 13 (6%) |

| 50–200 transplants per year | 98 (42%) |

| >200 transplants per year | 123 (52%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0%) |

|

| |

| Number of pediatric transplants performed at your center | |

| < 50 transplants per year | 123 (64%) |

| 50–200 transplants per year | 55 (28%) |

| >200 transplants per year | 3 (2%) |

| Don’t know | 12 (6%) |

|

| |

| Training in palliative care* | |

| Attended CME courses and educational lectures | 128 (46%) |

| No training | 102 (37%) |

| Rotation during residency or fellowship | 81 (29%) |

| 6 months or more of formal training | 4 (1%) |

Participants may choose multiple answers to these questions.

All participants who chose ‘other’ board certification also reported having board certification in hematology and/or oncology.

Access and quality of PC services

Physicians reported collaborating more often with PC services for inpatient (118/277, 43%) than outpatient care (57/277, 21%). The quality of inpatient and outpatient PC services were considered excellent by 45% (124/277) and 30% (82/277) of physicians, respectively. When it comes to ownership over PC issues, most physicians (245/277, 88%) stated that a hematologist-oncologist should have expertise in the management of physical symptoms of hematologic diseases, and 84% (233/277) felt that a hematologist-oncologist should coordinate the care of patients across all stages of disease, including at the end of life. When asked if a hematologist-oncologist is the best person to provide PC for patients with hematologic disease, 16% (45/277) agreed with the statement, 38% (104/277) were neutral, and 46% (128/277) disagreed.

Perceptions and Attitudes about PC

Figure 1 depicts physicians’ attitudes about PC. The majority of physicians (70%, 193/277) agreed that all patients with advanced hematologic diseases should receive PC, even if they are receiving active therapy. While the majority (210/277, 76%) stated that they trust PC clinicians to care for their patients, 40% (110/277) endorsed that PC clinicians do not have enough understanding about hematology/oncology to counsel HSCT recipients regarding their treatments.

Figure 1. Physicians’ attitudes about palliative care.

PC = palliative care.

Most physicians expressed concerns about how patients perceive PC [Figure 2]. For example, most reported that when patients hear the term PC, they feel scared (82% 227/277), anxious (76%, 210/277), and stressed (72%, 199/277) [Figure 2A]. Moreover, if a PC referral is suggested, 65% (180/277) of physicians endorsed that patients might think nothing more can be done for their disease and 51% (142/277) agreed that patients may think that they will lose contact with their current hematology-oncology care team once the PC team is involved [Figure 2B].

Figure 2. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ attitudes towards palliative care.

A) physicians’ perceptions of patients’ emotional reaction towards palliative care; B) physicians’ perceptions of patients’ attitudes towards palliative care

Perceived Barriers to PC Utilization

Nearly half of transplant physicians (46%, 127/277) perceived the service name ‘palliative care’ as a barrier to referral, and 66% (184/277) endorsed that it decreases hope in patients and families [Figure 3A]. In contrast, transplant physicians felt more positively about the term ‘supportive care’ [Figure 3B]. Only 8% (22/277) perceived the service name ‘supportive care’ as a barrier for them to refer patients, and just 11% (31/277) felt that it decreases hope in patients and families [Figure 3B].

Figure 3. Physicians’ perspectives on the terms palliative care and supportive care.

A) Physicians’ perspectives on the term ‘palliative care’: EOL = end of life; B) Physicians’ perspectives on the term ‘supportive care’: EOL = end of life

Transplant physicians endorsed the following additional barriers to PC utilization: 1) patients’ discomfort with discussing end-of-life care issues (80%, 222/277); 2) families’ discomfort with discussing end-of-life care issues (83%, 229/277); 3) health care professionals’ discomfort with death (61% 168/277); 4) lack of clinical PC knowledge by HSCT physicians (60%, 167/277); and 5) cultural factors influencing end-of-life care (84%, 232/277).

Perception of Unmet PC Needs in HSCT

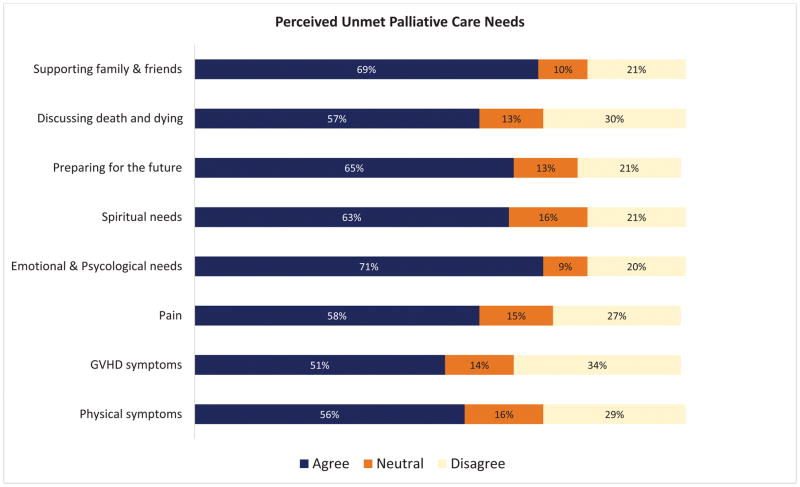

Most physicians recognized substantial unmet PC needs in their population, including: 1) physical symptoms (56%, 154/277); 2) graft-versus-host disease symptoms (51%, 142/277), 3) emotional and psychological needs (71%, 197/277); 4) spiritual needs (63%, 175/277); 5) preparing for future medical care (65%, 181/277); and 6) supporting patients’ family and friends (69%, 192/277) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Physicians’ perceptions of unmet palliative care needs in HSCT

Predictors of Transplant Physicians’ Attitudes Towards PC

We identified several predictors of a more positive attitude towards PC, including: female sex (β = 0.85, SE = 0.38, P = 0.024), having <10 years of clinical practice (β = 1.39, SE = 0.48, P = 0 = 0.004), and perceived quality of PC services (β = 0.60, SE = 0.08, P < 0.001) [Table 2]. To the contrary, physicians who perceived the name “palliative care” as a barrier to utilization (β = −0.12, SE = 0.06, P = 0.061), and those with a higher sense of ownership over PC issues (β = −0.36, SE = 0.08, P <0.001), were more likely to have a negative attitude towards PC.

Table 2. Predictors of transplant physicians’ attitudes towards palliative care*.

Ref = reference group; CME = continuing medical education; PC = palliative care.

| Predictors | Estimate* | Standard Error | T-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Female sex (ref: male) | 0.85 | 0.38 | 2.26 | 0.024 |

|

| ||||

| Non-White race (ref: White) | −0.56 | 0.41 | −1.38 | 0.169 |

|

| ||||

| Spiritual practice is important (ref: not important) | 0.60 | 0.38 | 1.60 | 0.111 |

|

| ||||

| Years of clinical practice (ref: > 20 years) | ||||

| < 10 years | 1.39 | 0.48 | 2.89 | 0.004 |

| 10–20 years | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.634 |

|

| ||||

| Time dedicated to clinical responsibilities (ref: 60% or less) | ||||

| > 60% | 0.44 | 0.37 | 1.20 | 0.231 |

|

| ||||

| Number of adult transplants performed at your center (ref: 200 or less) | ||||

| > 200 transplants | 0.43 | 0.38 | 1.14 | 0.258 |

|

| ||||

| Training in PC (ref: No Training) | ||||

| Attended CME courses & educational lectures | −0.03 | 0.43 | −0.07 | 0.946 |

| Rotation and/or 6 months or more of formal training +/− Attended CME courses | −0.61 | 0.48 | −1.27 | 0.206 |

|

| ||||

| Perceived quality of PC services | 0.60 | 0.08 | 7.05 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Perception that PC name is a barrier to utilization | −0.12 | 0.06 | −1.88 | 0.061 |

|

| ||||

| Physicians’ sense of ownership over PC issues | −0.36 | 0.08 | −4.42 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Physicians perceived expertise in managing PC needs | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.497 |

|

| ||||

| Physicians’ perception of unmet PC needs in HSCT | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.958 |

The main outcome of interest in this predictive model is physicians’ attitudes about palliative care, measured by a composite score, with higher values indicating more positive attitudes towards palliative care. A positive coefficient of estimate indicates a positive attitude about palliative care. For example, compared to physicians with more than 20 years of clinical practice, those physicians practiced less than 10 years had better attitudes about palliative care (1.39 points higher, P = 0.004). On the hand, a negative coefficient indicates a lower score and a more negative attitude towards palliative care.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively examine transplant physicians’ attitudes and perceptions about PC. Despite reporting immense PC needs for HSCT patients, only a minority of transplant physicians reported collaborating frequently with PC. Notably, transplant physicians have a strong sense of ownership over addressing the palliative and end-of-life care needs of their patients and families. While the majority of physicians reported trusting PC, they also expressed substantial concerns about PC clinicians’ knowledge about HSCT. Most were also concerned about patients’ perceptions and emotional reactions to PC and identified these reactions as barriers to PC utilization. However, we also found that certain physician traits are associated with more positive attitudes towards PC, including a shorter duration of time in practice, which likely equates to having trained in an era wherein PC involvement has been normalized as an increasingly standard part of cancer care. Similarly, we found more positive attitudes about PC were associated with prior use of PC services, such that more exposure may translate to greater comfort and confidence in the value and acceptability of PC services in HSCT. These data underscore the need for interventions to promote education, as well as collaboration between PC and HSCT, to help overcome the substantial barriers to PC integration in the care of this vulnerable population to address its many unmet PC needs.

While the majority of transplant physicians reported a positive attitude towards PC, a substantial minority still questioned the involvement of PC clinicians in the care of HSCT recipients. Importantly, 40% of respondents agreed that PC clinicians do not have enough understanding of hematology-oncology to counsel the HSCT population regarding their treatments. Despite a recent randomized clinical trial demonstrating substantial benefits of early PC integration in HSCT,19,20 many transplant physicians remain unconvinced regarding the potential role of PC expertise in addressing the needs of HSCT recipients. These findings are even more striking when compared to a prior survey of medical oncologists caring for patients with solid tumors, which demonstrated that over 90% of these physicians agreed that all patients with advanced cancer should receive PC, even if they are receiving active anti-tumor therapy.26 Transplant physicians’ attitudes may in part reflect a lower rate of current collaboration with both inpatient and outpatient PC or a belief that palliative care clinicians do not have adequate understanding of the different therapeutic options for patients with hematologic conditions. Nonetheless, these findings highlight the need to develop strategies to promote integration and enhance awareness of the potential role that PC can play in caring for patients undergoing HSCT and their families.

Most transplant physicians expressed substantial concerns regarding how patients perceive PC. In fact, most physicians thought that patients would have a negative emotional reaction to PC, associating a PC referral with dying, thinking less positively about the future, or feeling abandoned by the transplant team. In contrast, most physicians endorsed that discussing death and dying and preparing for the future are important unmet palliative care needs in this population. Interestingly, evidence suggests that most laypersons do not know what PC is, and do not inherently have positive or negative attitudes towards it.31, 32 Thus, patients’ and families’ perceptions of PC are most likely influenced by how it is presented to them by their medical team. Given that many clinicians have negative perceptions about PC, it may be that a primary driver of patients’ perceptions is the difficulty clinicians have in explaining what PC is, and introducing it as an important and integrated aspect of HSCT care. These findings underscore the critical need to enhance education about how to best discuss PC referrals with patients and how to present their role in enhancing the quality of life and care for patients throughout their course of illness, irrespective of prognosis.

We also identified multiple perceived barriers to PC utilization, including patients’, families’, and health care professionals’ discomfort with discussing end-of-life care issues, lack of knowledge about PC, and cultural factors. Furthermore, most physicians reported that the ‘palliative care’ service name is a barrier for referral, and preferred the term ‘supportive care,’ as has been shown in other studies.27, 33 However, transplant physicians’ discomfort with the term ‘palliative care’ surpasses what has been previously reported among oncologists caring for patients with solid tumors.27 These data are important for consideration in the palliative care community to discuss whether changing the service name may impact physicians’ perception of PC and their referral patterns. These barriers also highlight the common misconception equating PC with end-of-life care, or hospice care. With the mounting evidence supporting the benefit of early PC for all patients with serious illness,14–20 there is a unique opportunity to promote PC involvement early in the course of illness and overcome these misconceptions.

Our study has several important limitations. First it is a cross-sectional survey of transplant physicians with a response rate of 28% potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. While this response rate may seem low, it is better than what is commonly seen in contemporary electronic survey studies.26, 27, 34 Thus, our conclusions must be tempered by the selection bias of survey respondents versus non-respondents. However, our findings suggest that transplant physicians with more favorable perceptions of PC were more likely to complete this survey. As such, our findings likely underestimate the negative perceptions and attitudes about PC in the transplant community. Irrespective of this bias, our findings are highly relevant for transplant and PC practices in the United States. Second, we did not capture the transplant centers of the study responders, which limit our ability to examine any interdependence of survey responses based on transplant practice. Third, we limited this survey to transplant physicians, and thus we are unable to comment on the perception of PC by other transplant clinicians and advance practice clinicians. Finally, the current study tested hypotheses concerning physicians’ philosophies and practice plans. Patient attitudes are an equally important area of research and will be the subject of future studies by the ASBMT Palliative and Supportive Care task force.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the majority of transplant physicians hold positive attitudes about PC and trust PC clinicians. However, a substantial minority express concerns about PC expertise in caring for transplant patients. Importantly, most physicians worry that patients have a negative emotional and cognitive reaction to PC, which is a major perceived barrier to PC utilization. Future efforts to promote early PC integration in HSCT will be critical to enhance collaboration and bidirectional education, and to overcome the common misconceptions equating PC with end-of-life care and hospice.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment Research Support: This work was supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute (El-Jawahri K12), Petersdorf (AI069197, CA162194, CA100019, and CA218185-National Institute of Health)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

Authors Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H. Health-related quality of life following haematopoietic cell transplantation: patient education, evaluation and intervention. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:373–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H. Quality of life after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:7–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Rambo TD, et al. Quality of life and psychological distress of bone marrow transplant recipients: the ‘time trajectory’ to recovery over the first year. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:477–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bevans MF, Marden S, Leidy NK, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients receiving reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:101–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121:951–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prieto JM, Atala J, Blanch J, et al. Patient-rated emotional and physical functioning among hematologic cancer patients during hospitalization for stem-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:307–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fife BL, Huster GA, Cornetta KG, Kennedy VN, Akard LP, Broun ER. Longitudinal study of adaptation to the stress of bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1539–1549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Jawahri AR, Vandusen HB, Traeger LN, et al. Quality of life and mood predict posttraumatic stress disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2016;122:806–812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bevans M, El-Jawahri A, Tierney DK, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: The Patient-Centered Outcomes Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291:2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altmaier EM, Ewell M, McQuellon R, et al. The effect of unrelated donor marrow transplantation on health-related quality of life: a report of the unrelated donor marrow transplantation trial (T-cell depletion trial) Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syrjala KL, Chapko MK, Vitaliano PP, Cummings C, Sullivan KM. Recovery after allogeneic marrow transplantation: prospective study of predictors of long-term physical and psychosocial functioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;11:319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz-Kindermann F, Mehnert A, Scherwath A, et al. Cognitive function in the acute course of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:789–799. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438–1445. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of Inpatient Palliative Care on Quality of Life 2 Weeks After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2094–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Greer JA, et al. Effect of Inpatient Palliative Care During Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplant on Psychological Distress 6 Months After Transplant: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.2800. JCO2017732800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell DA, Shellens R, Roman E, Garry AC, Patmore R, Howard MR. Haematological malignancy: are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliat Med. 2011;25:630–641. doi: 10.1177/0269216310391692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manitta VJ, Philip JA, Cole-Sinclair MF. Palliative care and the hemato-oncological patient: can we live together? A review of the literature. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1021–1025. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein AS, Goldberg GR, Meier DE. Palliative care and hematologic oncology: the promise of collaboration. Blood Rev. 2012;26:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeBlanc TW, O’Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e230–238. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeBlanc TW, El-Jawahri A. When and why should patients with hematologic malignancies see a palliative care specialist? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:471–478. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherny NI, Catane R European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on P, Supportive C. Attitudes of medical oncologists toward palliative care for patients with advanced and incurable cancer: report on a survery by the European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on Palliative and Supportive Care. Cancer. 2003;98:2502–2510. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milne D, Aranda S, Jefford M, Schofield P. Development and validation of a measurement tool to assess perceptions of palliative care. Psychooncology. 2013;22:940–946. doi: 10.1002/pon.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buzgova R, Kozakova R, Sikorova L, Zelenikova R, Jarosova D. Development and psychometric evaluation of patient needs assessment in palliative care (PNAP) instrument. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14:129–137. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Groenvold M. Development and initial validation of the Three-Levels-of-Needs Questionnaire for self-assessment of palliative needs in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center_to_Advance_Palliative_Care. 2011 Public Opinion Research on Palliative Care. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman K, Abraham C, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Lay understanding of terms used in cancer consultations. Psychooncology. 2003;12:557–566. doi: 10.1002/pon.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16:105–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morton LM, Cahill J, Hartge P. Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: a survey of practice. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:197–203. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]