Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) is a sexually transmitted pathogen associated with inflammatory syndromes in men and women. Macrolides and fluoroquinolones are recommended MG treatments. The frequency of MG strains with macrolide resistance-associated mutations (MRMs) and quinolone resistance-associated mutations (QRMs) is increasing worldwide, however these data are sparse in populations in the US.

Methods

We investigated the prevalence of MG infections with MRMs and QRMs and MG infection concordance within African American couples in Birmingham, Alabama. We used a real-time PCR to detect MG and identify MRMs. QRMs were detected using traditional PCRs amplifying regions in gyrA, gyrB, parC and parE. MG concordance in couples was evaluated by MG positivity and MG genotypes.

Results

Oral, anal, urine, and/or vaginal specimens were tested from 116 couples. Twenty-eight (12.1%) participants comprising 22 couples tested MG positive (11.2% in men and 12.9% in women). MRMs were detected in 17 (60.7%) MG positive participants, with gender-specific resistance rates of 69.2% for men and 53.3% for women. QRMs were detected in 3 (11.1%) MG positive participants, all of whom also had MRMs. By MG positivity status, 27.3% of couples were concordant. If MG strain genotypes are also considered, then concordance was 20.0%.

Conclusions

Among heterosexual African Americans with MG infection, about 60% had strains with MRMs and 11% had strains with both MRMs and QRMs, highlighting the potential for MG treatment failure to not only macrolides, but also quinolones. These findings may help to guide clinicians in MG testing and treatment decisions in the US.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, resistance, couple, African American

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma genitalium (MG), a sexually transmitted pathogen, is a common cause of urethritis and cervicitis (1, 2) and is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, and pregnancy complications (3). Because culturing MG is slow and difficult, molecular MG tests are preferred. Despite several published MG nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) (4–7), there are no US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved MG diagnostic tests available. Given the diagnostic challenges, MG treatment is usually empiric and mainly in the context of syndromic management.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended first-line antimicrobial for urethritis, cervicitis, and PID cases in which MG is suspected is azithromycin (2). However, MG infection cure rates with azithromycin 1 gram single dose are rapidly declining, averaging 67% since 2009 (8). Azithromycin MG treatment failures have been primarily attributed to MG strains with macrolide resistance-associated mutations (MRMs) in the 23S rRNA gene, typically A2071 and A2072 (E.coli numbering 2058 and 2059) (9). The frequency of MG strains with MRMs detected in MG infections in the US based on two studies ranges from 42% to 80% (10, 11), which is similar to estimates reported outside the US (12–14). The CDC recommended second-line antimicrobial for suspected MG infections, in the case of azithromycin treatment failure, is moxifloxacin (2). However, MG quinolone treatment failures associated with MG quinolone resistance-associated mutations (QRMs) have also been reported (15–17). The MG QRMs are point mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of topoisomerase IV gene parC and DNA gyrase gene gyrA (15–17). Limited microbiological evidence has approved that S83I and G81C mutations in ParC are closely related to MG quinolone resistance, while the level of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) may be modified by mutations in GyrA (18, 19). The frequency of MG strains with QRMs detected in MG infections has been reported to be as low as 5–8% in Europe (20–22) and as high as 47.1% in Japan (23). We published the only US study evaluating for MG QRMs, finding a prevalence of 29.6% in HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) with MG infection (11). There are no publications on frequency and mechanisms of MG QRMs in heterosexuals in the US.

Because African Americans are at higher risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) compared to other races/ethnicities (24) and there is limited knowledge on the epidemiology and transmission of STIs within couples, we are conducting a longitudinal prospective study of STIs among African American couples in Birmingham, Alabama in which the study’s primary objective is to assess STI concordance within couples and elucidating factors influencing sexual transmission of several pathogens. The objectives of the current study were to retrospectively evaluate MG infection prevalence, frequency of MG MRMs and QRMs, and MG infection concordance within couples enrolled in the parent study. Such knowledge could be very important in MG treatment considerations, considering the potential for MG infections with MRMs and QRMs to fail treatment and the limited availability of antibiotics for effectively treating MG infections in the US.

METHODS

Participants

The study population was comprised of heterosexual couples with individuals ≥19 years of age. African American men presenting to the Jefferson County Department of Health (JCDH) STD Clinic in Birmingham, Alabama for STI evaluation were prospectively enrolled in a longitudinal study of STI concordance among couples in which males were asked to refer their primary female sexual partner for evaluation within 24 hours of enrollment. Primary partner was defined as a partner with whom the male had been having sex for >30 days, had sex more often than with other female partners, and planned to continue having sex with in the future. Exclusion criteria included inability to take azithromycin, antibiotic use in the prior 30 days, or immunosuppressive medical conditions (including HIV infection). Additional exclusion criteria for males included concomitant syphilis, chronic urethritis symptoms (>14 days), recurrent diagnoses of non-gonococcal urethritis (>3 in the preceding 12 months), symptoms or signs of epididymitis or prostatitis, and having male sexual partners. Additional exclusion criteria for females included pregnancy, breast feeding, or being post-menopausal.

Clinical Procedures

At enrollment, participants were interviewed regarding demographics and medical and sexual history, underwent genital examination, and had the following specimens collected irrespective of whether the corresponding body site was reported to have been exposed in sexual activities: urine (first-catch), swabs from genital (males: clinician-collected urethral swab; females: self-collected vaginal swab), oral (clinician-collected), and anal (clinician-collected) sites. Gram stains were performed on urethral swab specimens (for counting PMNs and looking for intracellular Gram-negative diplococci indicative of presumptive gonorrhea) and wet mounts on vaginal swab specimens (for detection of yeast, trichomonads, and bacterial vaginosis findings). Bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed by Amsel criteria (25). Swabs and urine specimens were tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Roche Diagnostics, IN) and residual DNA was stored at −80°C. These same specimens were tested for Trichomonas vaginalis by transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) (Hologic, CA), and TMA results were used for analyses. For this study, we retrospectively performed MG testing (for detection of MG, MRMs and QRMs, and MG genotypes) on DNA (from urine specimens from males and vaginal swab specimens from females, and oral and anal specimens from both males and females) stored frozen at −80°C for 4–6 weeks and analyzed clinical data for all couples enrolled between February 2015 and November 2017. The study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board and JCDH.

MG Testing

MG detection was carried out on a Light Cycler 480 II (Roche Diagnostics, IN) using a modified real-time PCR assay (MG macrolide resistance [MGMR] PCR) targeting the 23S rRNA gene with a limit of detection of 2.3 genome copy/μL in the PCR template (26). This quantitative assay also differentiates wild type versus MRMs by melting curve analysis. Briefly, 2 μL of template DNA was tested in a 20 μL PCR reaction mixture containing 0.375 μmol/L of MGMR-F primer, 0.5 μmol/L of MGMR-R primer, 0.1 μmol/L of each probe (MGMR-P1 and MGMR-P2-2), 0.4 U of LightCycler® Uracil-DNA Glycosylase and 10 μL of LightCycler® 480 Probes Master (both from Roche Diagnostics, IN). Quantified mutant and wild type positive controls and a negative control were included in each test. MG quantification was performed using an external standard curve that was established by serial dilutions of positive controls. Amplicons (wild type or mutant) were sequenced using the same PCR primers to verify mutations. Sequences were analyzed using CLC Main Workbench 7 (Qiagen, CA).

QRMs were detected by four traditional PCR assays amplifying the QRDR of gyrA and parC, as well as the partial region of gyrB and parE (see Supplementary Table 1) (27–29). Nested PCR was performed if first amplicons were not detected by agarose gel. PCR was carried out with a 25 μL PCR reaction volume containing 0.4 μmol/L of each primer, 2.5 μL of 10X AccuPrime Pfx reaction mix and 0.5 U of AccuPrime Pfx DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher, CA). The PCR products were sequenced and analyzed as above.

MG positive samples were genotyped by a dual loci scheme, MG191 SNP and MG309 STR, which has been previously recommended for sexual network studies (30). MG191 and MG 309 loci were amplified using MgPa-1/MgPa-3 and MG309-STR-F/MG309-STR-R primer sets, respectively. PCR amplicons were sequenced. MG191 sequences were compared to published sequences in NCBI and a sequence type was assigned. The number of short tandem repeats of MG309 was counted. The types of the two loci were combined and renamed utilizing a numeric system for purposes of data analysis and presentation.

Statistical Analysis

We determined the prevalence of MG infection and frequency of MRMs and QRMs by gender and across specimen types. Comparisons across groups of categorical variables were based on Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact tests. Non-normally distributed continuous data were compared using a Kruskal Wallis test. We calculated the crude prevalence ratio (PR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for MG infection in partners of enrolled participants who tested MG positive. All statistical testing was performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant clinical characteristics

A total of 232 patients (116 heterosexual African American men and their primary female sexual partners) were enrolled in the study. All participants were African American, except for one Caucasian female. The median participant age was 25.0 years and men were slightly older than women (median 26.0 vs. 23.5 years, p = 0.02) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics and association with M. genitalium (MG) infection.

| Study Cohort Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall (N=232) | MG Negative (N=204) | MG Positive(N=28) | p-Value |

| Median age (Range) | 25.0 (18.0 – 56.0) | 26.0 (18.0 – 56.0) | 21.5 (18.0 – 52.0) | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.69 | |||

| Male | 116 | 103 (88.8%) | 13 (11.2%) | |

| Female | 116 | 101 (87.1%) | 15 (12.9%) | |

| Male Participant Characteristics | ||||

| Characteristic | Overall (N=116) | MG Negative (N=103) | MG Positive (N=13) | p-Value |

| Median age (Range) | 26.0 (19.0, 56.0) | 26.0 (19.0, 56.0) | 25.0 (21.0, 52.0) | 0.60 |

| Trichomoniasis | 11 (9.5%) | 11 (10.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.61 |

| Chlamydia | 23 (19.8%) | 21 (20.4%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1.00 |

| Gonorrhea | 14 (12.1%) | 10 (9.7%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0.05 |

| Urethral Gram Stain PMNs | 0.14 | |||

| <5/hpf | 53 (45.7%) | 50 (48.5%) | 3 (23.1%) | |

| ≥5/hpf | 63 (54.3%) | 53 (51.5%) | 10 (76.9%) | |

| Circumcised | 100 (86.2%) | 89 (85.4%) | 12 (92.3%) | 0.69 |

| Urethral discharge symptom | 26 (22.6%) | 20 (19.6%) | 6 (46.2%) | 0.03 |

| Urethral discharge finding | 28 (24.1%) | 22 (21.4%) | 6 (46.2%) | 0.05 |

| Female Partner Characteristics | ||||

| Characteristic | Overall (N=116) | MG Negative (N=101) | MG Positive(N=15) | p-Value |

| Median age (Range) | 23.5 (18.0, 46.0) | 25.0 (18.0, 46.0) | 20.0 (18.0, 33.0) | 0.001 |

| Hormonal contraception | 21 (18.1%) | 17 (16.8%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.47 |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 55 (47.4%) | 51 (50.5%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.10 |

| Trichomoniasis | 23 (19.8%) | 22 (21.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0.30 |

| Chlamydia | 24 (20.7%) | 22 (21.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.73 |

| Gonorrhea | 15 (12.9%) | 14 (13.9%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0.69 |

| Cervical discharge | 16 (14.2%) | 14 (14.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1.00 |

| Vaginal discharge symptom | 35 (30.2%) | 28 (27.7%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0.14 |

| Vaginal discharge finding | 93 (80.2%) | 82 (81.2%) | 11 (73.3%) | 0.49 |

MG infection prevalence and organism load

MG was detected in 28 (12.1%) participants: 23 were MG positive at a single body site and 5 were positive at two body sites. MG positivity did not significantly differ by gender (11.2% for men and 12.9% for women) (Table 1). Urethral discharge was reported more often in men who had MG detected (46.2% vs. 19.6%, p = 0.03). MG positivity was also more common among men with gonorrhea (30.8% vs. 9.7%, p = 0.05). Among women, younger age was the only factor associated with a higher frequency of MG positivity (p = 0.001).

From 666 specimens (116 urine, 114 oral swabs, and 101 anal swabs from men; 116 vaginal swabs, 114 oral swabs, and 105 anal swabs from women), 33 (5.0%) were MG positive (Table 2). The body site-specific MG infection prevalence did not significantly differ by gender (p = 0.14). MG infection prevalence was higher in participants with urogenital symptoms versus those without, though the difference did not reach statistical significance (males 15.0% vs. 9.3% and females – 15.4% vs. 9.8%; p > 0.3 for both).

Table 2.

M. genitalium (MG) positivity by gender and body site.

| All Body Sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Urogenital | Oral | Anal | Total |

| Positive | 22 (9.5%) | 2 (0.9%) | 9 (4.4%) | 33 (5.0%) |

| Total | 232 (100%) | 228 (100%) | 206 (100%) | 666 (100%) |

| Females | ||||

| Result | Urogenital | Oral | Anal | Total |

| Positive | 12 (10.3%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (6.7%) | 15 (4.5%) |

| Total | 116 (100%) | 114 (100%) | 105 (100%) | 335 (100%) |

| Males | ||||

| Result | Urogenital | Oral | Anal | Total |

| Positivea | 10 (8.6%) | 2 (1.8%) | 2 (2.0%) | 13 (3.9%) |

| Total | 116 (100%) | 114 (100%) | 101 (100%) | 331 (100%) |

Notes: M. genitalium was detected by MGMR PCR.

Column percentages are presented for each body site; therefore, those percentages will not sum to the total percentage.

Includes both wild-type and drug-resistant associated mutant Mycoplasma genitalium (MG)

The median MG load of all samples was 7.4 genome copy/μL (range 0.5 to 5090) in the PCR template. Urogenital samples had a higher MG load (median 10.7 [range 0.5–5090]) than oral (median 7.2 [range 0.9–13.4]) and anal (median 2.0 [range 0.5–266]) specimens, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.31).

Frequency of MRMs and QRMs in MG-infected participants

Among 28 MG positive participants, 17 (60.7%) carried strains with MRMs: 9 men and 8 women (Table 3A). The detected MRMs were A2071G (E.coli numbering 2058) in 12 participants (7 males and 5 females) and A2072G (E. coli numbering 2059) in 5 participants (2 males and 3 females) (see Supplementary Table 2). Five couples had the same MRMs (see Supplementary Table 2). The frequency of MRMs among MG-infected participants did not significantly differ by gender (69.2% vs. 53.3% in men vs. women) (Table 3A) or body site (Table 3B).

Table 3.

Frequency of M. genitalium (MG) strains with macrolide-associated resistance mutations (MRMs), quinolone-associated resistance mutations (QRMs), and both MRMs and QRMs (MDR). A) Stratified by patient sample in males and females; B) Stratified by body sites in males and females.

| A. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MRMs | QRMs | MDR | |

| Patients: | |||

| Male (n=13) | 9 (69.2%) | 2 (16.7%)a | 2 (16.7%)a |

| Female (n=15) | 8 (53.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Total (n=28) | 17 (60.7%) | 3 (11.1%)a | 3 (11.1%)a |

| Samples: | |||

| Male (n=14) | 9 (64.3%) | 2 (15.4%)a | 2 (15.4%)a |

| Female (n=19) | 11 (57.9%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Total (n=33) | 20 (60.6%) | 3 (9.4%)a | 3 (9.4%)a |

| B. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Body Sites | ||||

| Urogenital (n=22)a | Oral (n=2) | Anal (n=9) | Total (n=33) | |

| MRMs | 15 (68.2%) | 1 (50.0%) | 4 (44.4%) | 20 (60.6%) |

| QRMs | 2 (9.1%)b | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (9.1%)b |

| MDR | 2 (9.1%)b | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (9.1%)b |

| Males | ||||

| Urogenital (n=10) | Oral (n=2) | Anal (n=2) | Total (n=14) | |

| MRMs | 8 (80.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (64.3%) |

| QRMs | 1 (11.1%)b | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (15.4%)b |

| MDR | 1 (11.1%)b | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (15.4%)b |

| Females | ||||

| Urogenital (n=12) | Oral (n=0) | Anal (n=7) | Total (n=19) | |

| MRMs | 7 (58.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 11 (57.9%) |

| QRMs | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| MDR | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

The urogenital sample tested was urine in males and vaginal swab in females.

QRM testing from a urine sample DNA failed in one male participant.

Among 28 MG positive participants, 3 (11.1%, 1 failed testing) had strains with QRMs: one couple (urogenital) and 1 man (oral) (Table 3A, 3B and see Supplementary Table 2). All 3 participants harbored the same parC mutation, C248T (amino acid change S83I), a previously described MG QRM associated with quinolone resistance (19). We found 5 additional mutations in parC or parE that cause amino acid changes (see Supplementary Table 2); however, the biological functions of these mutations are unknown. No mutations were found in gyrA or gyrB in successfully tested samples. All strains with QRMs also had MRMs, therefore the frequency of MG strains with both QRMs and MRMs (multi-drug resistant [MDR] MG) in the 28 MG positive participants was 11.1%.

The MG organism load (genome copy/μL) was significantly higher in MG strains with resistance-associated mutations compared with wild-type strains, median (range) 14.8 (1.70 – 5090) vs. 1.69 (0.52 – 203); p = 0.002).

Couple concordance

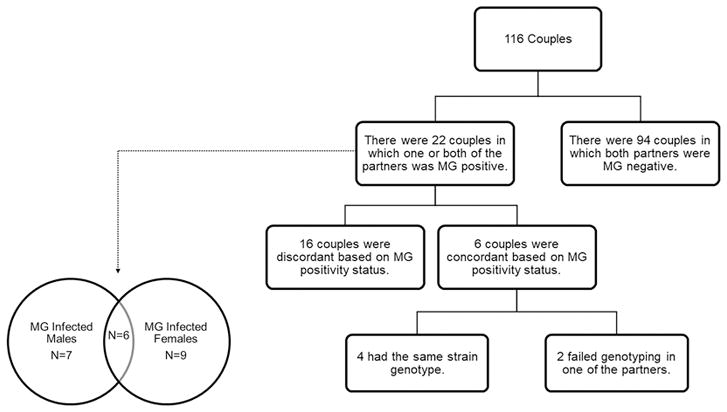

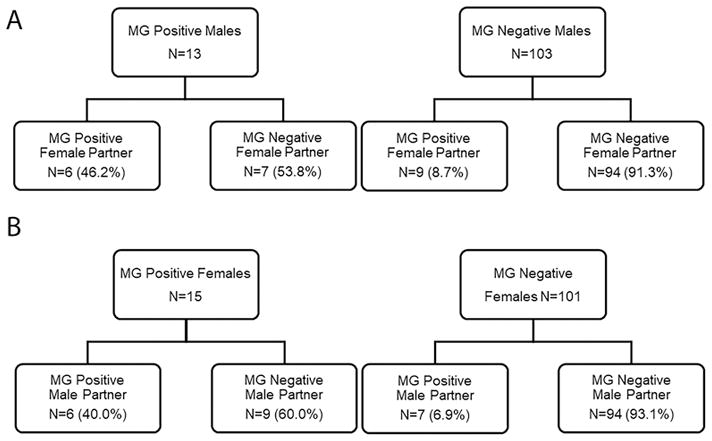

MG concordance in couples was analyzed initially by MG positivity status, then by MG strain genotype. Among 116 couples, there were 22 (19.0%) in which at least one partner was MG positive: 6 couples (27.3%) were concordant vs. 16 (72.7%) discordant (Figure 1). Of MG positive males, 46.2% of their female partners were MG positive (Figure 2). Female partners had a 5.3-fold higher MG prevalence if their male partners were MG positive (PR 5.28, 95% CI 2.24–12.44, p<0.001). Of MG positive females, 40.0% of their male partners were MG positive (Figure 2). Male partners had a 5.8-fold higher MG prevalence if their female partners were MG positive (PR 5.77, 95% CI 2.24–14.86, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Concordance of M. genitalium (MG) infection in couples by MG positivity status and strain genotypes.

Figure 2.

M. genitalium (MG) infection prevalence in participants and their partners, stratified by gender. A) MG infection prevalence in female partners based on the MG positivity status of the male participants. B) MG infection prevalence in male partners based on the MG positivity status of female participants.

Only 19 out of 33 samples were successfully genotyped for both MG191 and MG309 loci (see Supplementary Table 2). Among the 19 dual-typed samples there were 13 genotypes. Among the 6 MG concordant couples, 4 carried the same genotype and 2 were not successfully genotyped in one of the partners. If both MG positivity status and strain genotypes are considered in determining MG infection concordance, then only 4 (20.0%, 4/20) couples were concordant (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The key findings from our study of MG infection within heterosexual African American couples in Birmingham, AL were that MG infection prevalence was high (12.1%), MG strains with MRMs were common (60.7%), MG strains with QRMs were not uncommon (11.1%), and the concordance of MG infection in couples was low (27.3% by MG positivity and only 20.0% when strain genotypes were also considered).

This study reported the frequency and mechanism of MRMs in MG-infected heterosexual African Americans in the US. Compared with MG-infected African Americans in the Getman et al. study, we found a similar frequency of MRMs in females (53.3% vs. 57.8%) but a higher frequency of MRMs in males (69.2% vs. 45.4%) (10). These differences in frequency of MG strains with MRMs between the cohorts may reflect geographical differences in resistance rates and differences in prior azithromycin exposure in the study populations. Our smaller sample size could have also contributed to the difference. It has been reported that MRMs develop in about 10% of MG-infected patients after receiving azithromycin, most MG infection treatment failures are associated with MG strains containing MRMs, and longer azithromycin treatment courses do not improve the MG infection cure rate in strains with MRMs (31). Thus, azithromycin may no longer be an effective first-line treatment for MG infections. Since doxycycline is also ineffective against MG infections, this leaves the fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin as the best MG treatment option in the US.

This study found that 11.1% of MG strains had QRMs in MG-infected heterosexuals in the US, which is markedly lower than the frequency of MRMs. We recently reported that 29.6% of MG infections in HIV-infected MSM in Birmingham, Alabama had strains with QRMs (11). Two Canadian studies also showed similar frequencies (12.2% – 20%) of QRMs in MG infections (12, 32). All MG infections with strains carrying QRMs in our study harbored the ParC mutation S83I, a SNP associated with moxifloxacin resistance (19). We also detected other mutations in parC and parE that were nonsense or caused amino acid changes, but the impact of these mutations on MG treatment outcomes is unknown. All MG infections with strains carrying QRMs in our study also had MRMs, thus the frequency of potentially multi-drug resistant strains among MG infections was 11.1%, higher than rates reported in Canada (21) and European countries (20, 22) (<5%), similar to the frequency in Australia (8.6%) (33), and lower than the frequency in Japan (30.8%) (34). In the US, there are limited other drugs available for treating the potentially multi-drug resistant MG infections. An extended minocycline regimen has been shown to be effective in some cases in Japan (17), while doxycycline eradicates MG in only about 30% of cases (35).

One of our study objectives was to examine MG infection concordance among couples, which could provide insight into MG transmission and the natural history of infection. Concordance was initially analyzed based on MG test positivity of each partner and 27.3% of couples were concordant. Taking into account MG strain genotypes, the MG concordance frequency was only 20.0%. Interestingly, 13 of the 33 MG positive specimens had different MG genotypes, suggesting considerable MG strain diversity in our cohort. Our results also agree with previous reports that this dual typing system has the discriminatory power to be useful in sexual networks studies (30, 36). However, the concordance of this study was low compared to the previous studies using single locus or multi loci sequencing typing methods (37, 38). When considering risk of MG transmission from an infected participant to their partner, we found that the female partners were over 5 times more likely to be MG positive if the male participant was MG positive. From the perspective of female participants, male partners were also over 5 times more likely to be MG positive if the female participant was MG positive. Although these risk data may be overestimated, as individuals could have been infected from other casual partners, the trend of transmission risk is in agreement with two other studies that enrolled patients including African American females and their male partners showed that the male partners were 5–9 fold more likely to be MG positive if the female participant was MG positive (39, 40). These previous concordance studies only focused on MG positivity status and did not incorporate MG strain typing, which could have further discriminated concordance. Interestingly, the MG infection concordance rate was much lower than reported chlamydia concordance rates, which ranged from 68–76% (41, 42). Because only 58% of specimens could be successfully genotyped, our concordance analysis had limited power and it was challenging to interpret the significance of the proportion of couples concordantly infected with the same genotype; the low rate of successful genotyping was in part due to using archived frozen specimens in this study, the unknown sensitivity of genotyping PCRs, and our requiring both MG191 and MG309 loci be successfully genotyped to ensure sufficient discriminatory ability for concordance. It is possible that MG is biologically less transmissible than C. trachomatis per sexual encounter, an explanation for which there are no data to our knowledge. It is also possible that MG infections have a much shorter duration than chlamydia prior to detection or resolution. Findings from two studies on the natural history of chlamydia suggest that about 50% of chlamydial infections may persist for one year after initial detection (43, 44). In contrast, three studies of the natural history of MG infection in females prior to 2018 showed that less than half of infections persisted longer than 3 months after initial detection (39, 45, 46) and two more studies of MG infection in females published in 2018 showed about 80% of infections were cleared by 12 months after detection (47, 48). Thus, the natural history of MG infection, with respect to infection duration, is likely a major factor influencing infection concordance among couples. Studies on immune responses that mediate MG clearance are needed to better understand MG infection concordance and clearance. An improved understanding of the duration of MG infections will be useful in development of MG testing recommendations and in treatment decisions. For example, if MG screening becomes recommended in the future, the frequency of screening would likely be more often than annually (at least in higher prevalence populations) since most infections have cleared by 12 months. Also, if MG concordance rates are low and infection duration short, further consideration may be given as to whether contacts of MG-infected patients should be treated vs. whether there is a role for basing partner treatment on results of MG testing.

Our study evaluated MG infection prevalence, frequency of MG strains with MRMs and QRMs, and MG infection concordance only in heterosexual African American couples in Birmingham, AL. Findings could differ in populations of different races/ethnicities or geographic locations and in same sex partnerships. Because of the relatively small number of MG infections, the precision of our estimates on frequency of MG MRMs and QRMs and MG infection concordance may be limited. Because some individuals in our couples may have had casual partners, for which data were not collected in the study, this could have confounded the MG infection prevalence and concordance rate. It is also possible that presence of other STIs in our couples could confound concordance by affecting the natural history of MG infection, however our study was not designed to sufficiently address this possibility. Because males with persistent or recurrent urethritis were already excluded from the longitudinal study that was the source of specimens and data for this retrospective study, our MG infection prevalence estimates may be lower than if we had included those males because studies suggest MG infection prevalence is higher in men with recurrent or persistent urethritis (2).

In summary, we found a low frequency of MG infection concordance in heterosexual African American couples seen at a STD clinic in Birmingham, Alabama, which has implications in MG testing and treatment considerations. Among MG positive participants, the majority had strains with MRMs and detection of QRMs was also not uncommon; all MG strains with QRMs also had MRMs. This finding of MG infections with potentially multi-drug resistant strains (based on gene mutations) should sound the alarm that efficacious treatments may not be available for some MG-infected patients in the US and therefore new MG treatments and/or treatment strategies (e.g., dual therapy) are urgently needed. There is also a need for a MG surveillance program in the US for monitoring frequency of MRMs and QRMs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by a Development Research Project Award (L. Xiao, PI) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Sexually Transmitted Infection Cooperative Research Center (grant U19AI113212; E. Hook, PI).

We thank all the University of Alabama at Birmingham STD Program clinicians and clinical and laboratory support staff who contributed to the study completion, as well as the Jefferson County Department of Health clinicians and clerical staff for their support. We thank Alexander Boutwell for his statistical support.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest: LX reports receiving research support paid to her institution from Roche Molecular. BVDP reports receiving honorarium, consulting fees or research support paid to her institution from Abbott Molecular, Atlas Genetics, BD Diagnostics, Click Diagnostics, Cepheid, Luminex, Rheonix, and Roche Molecular. EWH reports receiving honorarium or research support paid to his institution from Cepheid, Hologic, and Roche Molecular. WMG has received consulting fees from Hologic, Inc. for development of educational materials on Mycoplasma genitalium.

References

- 1.Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from Chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(3):498–514. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Workowski KA, Bolan GA Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lis R, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and female reproductive tract disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):418–26. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards T, Burke P, Smalley HB, et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for the rapid detection of Mycoplasma genitalium. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;83(1):13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen JS. Protocol for the detection of Mycoplasma genitalium by PCR from clinical specimens and subsequent detection of macrolide resistance-mediating mutations in region V of the 23S rRNA gene. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;903:129–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-937-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svenstrup HF, Jensen JS, Bjornelius E, Lidbrink P, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. Development of a quantitative real-time PCR assay for detection of Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(7):3121–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3121-3128.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabrizi SN, Tan LY, Walker S, et al. Multiplex Assay for Simultaneous Detection of Mycoplasma genitalium and Macrolide Resistance Using PlexZyme and PlexPrime Technology. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau A, Bradshaw CS, Lewis D, et al. The Efficacy of Azithromycin for the Treatment of Genital Mycoplasma genitalium: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1389–99. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Hamasuna R. Azithromycin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium-positive patients with nongonococcal urethritis is associated with induced macrolide resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(12):1546–53. doi: 10.1086/593188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Getman D, Jiang A, O’Donnell M, Cohen S. Mycoplasma genitalium Prevalence, Coinfection, and Macrolide Antibiotic Resistance Frequency in a Multicenter Clinical Study Cohort in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(9):2278–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01053-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dionne-Odom J, Geisler WM, Aaron KJ, et al. High Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men in Alabama. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(5):796–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gesink D, Racey CS, Seah C, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium in Toronto, Ont: Estimates of prevalence and macrolide resistance. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(2):e96–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson T, Coughlan E, Werno A. Mycoplasma genitalium macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance detection and clinical implications in a selected cohort in New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01087-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trembizki E, Buckley C, Bletchly C, Nimmo GR, Whiley DM. High levels of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in Queensland, Australia. J Med Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couldwell DL, Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ, Gilbert GL. Failure of moxifloxacin treatment in Mycoplasma genitalium infections due to macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(10):822–8. doi: 10.1177/0956462413502008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissessor M, Tabrizi SN, Twin J, et al. Macrolide resistance and azithromycin failure in a Mycoplasma genitalium-infected cohort and response of azithromycin failures to alternative antibiotic regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(8):1228–36. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deguchi T, Ito S, Yasuda M, et al. Emergence of Mycoplasma genitalium with clinically significant fluoroquinolone resistance conferred by amino acid changes both in GyrA and ParC in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23(9):648–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi Y, Takei M, Kishii R, Yasuda M, Deguchi T. Contribution of topoisomerase IV mutation to quinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(4):1772–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01956-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamasuna R, Le PT, Kutsuna S, et al. Mutations in ParC and GyrA of moxifloxacin-resistant and susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Roy C, Henin N, Pereyre S, Bebear C. Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Mycoplasma genitalium, Southwestern France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(9):1677–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2209.160446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitt R, Fifer H, Woodford N, Alexander S. Detection of markers predictive of macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium from patients attending sexual health services in England. Sex Transm Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbera MJ, Fernandez-Huerta M, Jensen JS, Caballero E, Andreu A. Mycoplasma genitalium Macrolide and Fluoroquinolone Resistance: Prevalence and Risk Factors Among a 2013–2014 Cohort of Patients in Barcelona, Spain. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(8):457–62. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kikuchi M, Ito S, Yasuda M, et al. Remarkable increase in fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in Japan. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(9):2376–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao L, Waites K, Wang H, Van Der Pol B, Ratliff A, Geisler W. Evaluation of a Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection of Mycoplasma genitalium and Macrolide Resistance-Mediating Mutations from Clinical Specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumke R, Thurmer A, Jacobs E. Emergence of Mycoplasma genitalium strains showing mutations associated with macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in the region Dresden, Germany. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;86(2):221–3. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimada Y, Deguchi T, Nakane K, et al. Emergence of clinical strains of Mycoplasma genitalium harbouring alterations in ParC associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(3):255–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada Y, Deguchi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. gyrB and parE mutations in urinary Mycoplasma genitalium DNA from men with non-gonococcal urethritis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(5):477–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cazanave C, Charron A, Renaudin H, Bebear C. Method comparison for molecular typing of French and Tunisian Mycoplasma genitalium-positive specimens. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 4):500–6. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.037721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manhart LE, Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, Golden MR, Martin DH. Efficacy of Antimicrobial Therapy for Mycoplasma genitalium Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 8):S802–17. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gratrix J, Plitt S, Turnbull L, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Mycoplasma genitalium among STI clinic attendees in Western Canada: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e016300. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray GL, Bradshaw CS, Bissessor M, et al. Increasing Macrolide and Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(5):809–12. doi: 10.3201/eid2305.161745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deguchi T, Kikuchi M, Yasuda M, Ito S. Multidrug-Resistant Mycoplasma genitalium Is Increasing. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(3):405–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, Moi H. 2016 European guideline on Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):1650–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pond MJ, Nori AV, Witney AA, Lopeman RC, Butcher PD, Sadiq ST. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in nongonococcal urethritis: the need for routine testing and the inadequacy of current treatment options. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(5):631–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hjorth SV, Bjornelius E, Lidbrink P, et al. Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2078–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00003-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma L, Taylor S, Jensen JS, Myers L, Lillis R, Martin DH. Short tandem repeat sequences in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome and their use in a multilocus genotyping system. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tosh AK, Van Der Pol B, Fortenberry JD, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium among adolescent women and their partners. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):412–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thurman AR, Musatovova O, Perdue S, Shain RN, Baseman JG, Baseman JB. Mycoplasma genitalium symptoms, concordance and treatment in high-risk sexual dyads. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(3):177–83. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinn TC, Gaydos C, Shepherd M, et al. Epidemiologic and microbiologic correlates of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in sexual partnerships. JAMA. 1996;276(21):1737–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markos AR. The concordance of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection between sexual partners, in the era of nucleic acid testing. Sex Health. 2005;2(1):23–4. doi: 10.1071/sh04030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morre SA, van den Brule AJ, Rozendaal L, et al. The natural course of asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis infections: 45% clearance and no development of clinical PID after one-year follow-up. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13(Suppl 2):12–8. doi: 10.1258/095646202762226092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molano M, Meijer CJ, Weiderpass E, et al. The natural course of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in asymptomatic Colombian women: a 5-year follow-up study. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(6):907–16. doi: 10.1086/428287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen CR, Nosek M, Meier A, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and persistence in a cohort of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(5):274–9. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000237860.61298.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vandepitte J, Weiss HA, Kyakuwa N, et al. Natural history of Mycoplasma genitalium infection in a cohort of female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):422–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828bfccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sena AC, Lee JY, Schwebke J, et al. A silent epidemic: the prevalence, incidence and persistence of Mycoplasma genitalium among young, asymptomatic high-risk women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balkus JE, Manhart LE, Jensen JS, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium infection in Kenyan and US women. Sex Transm Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.