Abstract

Improving care quality and delivery for people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD) requires a comprehensive research agenda that encompasses the entire care continuum. Logistical and ethical challenges of informed consent for research participation of persons with ADRD include determination of capacity to consent, surrogate consent when capacity to consent is compromised, timely identification of the legally authorized representative (LAR) providing surrogate consent, and balancing residual autonomy with surrogate consent. These challenges are compounded in the acute care setting by short stays, limited access to patients, caregivers, and LARs, and the fluctuating influences of acute illness on capacity determination. To address these challenges, we worked with our Institutional Review Board to develop a procedural framework for obtaining informed consent from hospitalized ADRD patients and caregivers to participate in a minimal risk care intervention. The framework is specially designed for minimal risk situations where rapid enrollment is a necessity, and engages: 1) Rapid identification of surrogates to consent for patients who lack legal capacity to make medical decisions indicated by an activated health care power of attorney (HCPOA), and 2) Individualized formal assent procedures for patients who lack capacity to consent. These methods have proven effective in facilitating hospital-based recruitment in an ongoing randomized controlled trial, and provide a basis for increasing access to acute care clinical research for persons with ADRD. Bolstering research participation through more readily engaged consent procedures during acute illness is critical to fostering improvements in the delivery of high quality care to persons with ADRD.

Keywords: Informed consent, research, ethics, Alzheimer disease, dementia

Introduction

The relentlessly rising prevalence of Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD) reverberates through every facet of society. This is reflected in the continually rising costs for comprehensive ADRD care, which will reach $277 billion in the United States in 2018 and is estimated to reach over one trillion dollars by 2050.1 Despite the scale of the growing epidemic, disease-modifying therapies have remained elusive, and the current fragmented health care system is ill-equipped to deal with the unique challenges of longitudinal ADRD care.2 Improving the care processes of ADRD requires a comprehensive research agenda that encompasses the entire care continuum, including the acute care setting. However, there are logistical and ethical challenges to the informed consent for research participation of hospitalized persons with ADRD that are significant barriers to advancing this inclusive research agenda.3–6

Hospitalizations are common for persons with ADRD, and are associated with an increased risk of iatrogenic complications, protracted morbidity, and accelerated cognitive and functional decline.7,8 Hospitalizations are therefore an important area of both investigation and intervention, although research enrollment opportunities are constrained. Overall lengths of stay can be brief, and are frequently utilized as respite for caregivers.9 In addition to heightened time constraints, additional challenges of hospital-based consent include limited access to patients, caregivers, and legally authorized representatives (LAR), the fluctuating influences of acute illness on cognition, and requisite need to minimize interruptions to ongoing medical care.4 In total, there are four primary challenges to the informed consent for patients with ADRD that are compounded in the acute care setting.

1. Determination of capacity to consent.

Informed consent is both a principal tenet and legal requirement of ethical research involving human subjects.10 Informed consent is strongly anchored by individual autonomy, or deliberated self-rule, which becomes compromised in ADRD due to the neurodegenerative process that results in cognitive function loss.11,12 However, the presence of ADRD does not automatically preclude an individual from providing voluntary informed consent. Capacity to consent is both situational and domain-specific, thus necessitating individualized assessment.13,14 Judgements regarding capacity should also take into consideration the risk-benefit ratio of the respective decisions to be made, favoring higher thresholds for capacity in higher risk situations.13

2. Surrogate consent when capacity to consent is compromised.

Federal regulations, referred to as the Common Rule, require surrogate consent from a LAR when individuals lack the capacity to provide consent.15 Surrogate consent for research follows the principal dictates of surrogate decision-making for health care, which relies on substituted judgment that is ideally based on previously expressed preferences or values that best approximate the individual’s autonomy.16 Barring known or previously expressed preferences, the standard of best interest is then relied upon for surrogate consent.16 Advance research directives can provide prospective consent or facilitate substituted judgment, although are uncommon.17

Federal regulations offer limited procedural specifics for surrogate consent, resulting in wide variation among institutions and Institutional Review Boards (IRB).18 IRBs are instrumental in defining the role and responsibilities of surrogate consent based on stratification of the potential risks and benefits of research participation. Surrogate consent is generally viewed as acceptable and appropriate for minimal risk research, regardless of personal benefit.19,20 Alternatively, research involving greater than minimal risk requires the potential for personal benefit as a prerequisite for surrogate consent. The definition of personal benefit has tended to be broadly defined as inclusive of indirect or future theoretical benefit through the general advancement of knowledge through research. The principle of common good ethics has been utilized as a formal framework to broaden the inclusivity of personal benefit from research to include communal benefit.21 This approach acknowledges both the individual altruism that frequently motivates participation, as well as the broader societal benefits of research.

3. Identification of the legally authorized representative providing surrogate consent.

Federal regulations delegate surrogate identification to the state level, although few states provide legal definitions of who is authorized to provide surrogate consent for research.10,15,22 Consequently, there is significant variability across institutions and IRBs, although in general the LAR for surrogate consent for research follows the hierarchy of LAR for medical decision-making, with precedence given to court-appointed guardianship and health care powers of attorney (HCPOA), and then typically follows next-of-kin delegation.18 Some research suggests that people with ADRD who are identified as incapable of consenting to a medication trial are capable of appointing a research proxy.13 However, for some contexts, such as minimal risk studies where the participant is likely to incur direct benefits through improved clinical care, the burden of identifying a proxy while acutely ill may not outweigh the risks of delegated decision-making capacity.

4. Balancing of residual autonomy with surrogate consent.

The progression of ADRD lies on a continuum, and the necessary dichotomization of capacity determination creates an ethical challenge of appropriately balancing residual autonomy with the necessity of surrogate consent when capacity is compromised. This progressive nature of ADRD is complicated by periods of acute illness and hospitalization, where individuals with ADRD are at heighted risk for developing delirium and experiencing stress related to the unfamiliar environment and caregivers. However, the legal and regulatory dictates underpinning the consent process for persons who lack the capacity to provide their own consent has led to a predominant focus on institutional protection, often at the expense and frequent exclusion of the individual.23 This exclusion has the potential to violate the ethical principles of autonomy, justice, and respect.22 This form of moral exclusion of the individual creates an inherent tension with the ethical and regulatory necessity of surrogate consent for vulnerable persons with ADRD and the safeguarding against potential harm, coercion, exploitation, or undue influence. This is particularly important for an incurable disease with limited treatment options such as ADRD given the heightened risk for therapeutic misconception.24

The tension between moral exclusion and safeguarding the wellbeing of this vulnerable population has led to the formal integration of assent for research participation by individuals who lack the capacity to consent. The right of assent was first laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964, and has been expanded to include any individual who is deemed “incapable of giving informed consent”.25 Assent allows flexible but formal permission for enrollment while respecting the right of refusal at any time.3,5,6 In addition, participatory consent models for persons with ADRD have been developed that reject the standard informed consent model that prioritizes autonomy, and instead focuses on relational aspects of ADRD care involving family and caregivers while maximizing individual engagement through assent.3,11,23,26

The challenges of informed consent of hospitalized persons with ADRD risks the indiscriminate exclusion of this patient subgroup, or selection bias towards community or nursing home recruitment.4,5,26,27 Furthermore, as some research may constitute minimal risk for participants with greater likelihood of direct and indirect benefits, identifying procedures that maximize inclusion in acute care settings is critical. To our knowledge there are no standardized protocols for obtaining informed consent in this population for minimal risk situations in acute care environments. We therefore developed a procedural framework to facilitate the informed consent of hospitalized patients inclusive of all stages of ADRD. Our framework was developed within the context of a randomized controlled trial of a hospital-based transitional care intervention for persons with ADRD and their caregivers. The minimal risk study randomized hospitalized patients with ADRD to either enrollment in the Coordinated-Transitional Care Program (C-TraC) or usual care.28 C-TraC is a low-cost, telephone-based transitional care program designed to improve post-hospitalization care coordination and outcomes for patients discharged to the community. Caregivers are crucial to the C-TraC intervention and are enrolled separately from patients. In the present paper we describe the process for development of our procedural framework and illustrate its application in the C-TraC trial.

Methods

We engaged a three-step process to develop the procedural framework for the informed consent of hospitalized patients with ADRD: 1) a review of existing approaches and established legal and ethical standards; 2) collaboration with the institutional IRB to discuss legal requirements, acute care-specific challenges, and appropriate modifications for the specific risk/benefit ratio (very low risk intervention); and 3) scenario-based process mapping to inform the development of an informed consent tool and the overarching framework. As we were unable to locate any evidence reporting on existing approaches or standards for facilitating real time acute-care based consent of persons with ADRD, we identified existing approaches for adaptation to the acute care setting.26

In collaboration with the IRB, we simultaneously reviewed legal decision-making capacity evaluation requirements according to application of the Common Rule. While capacity is often broadly considered risk-specific and situational, federal regulations have yet to provide adequate guidance for situations where legal incapacity exists and is inconsistent with research-specific decisional capacity.29,30 Existing requirements evaluate decision-making capacity using legal designations of incapacity, such as those designated through formal incapacity assessments. In clinical context of the present intervention study, capacity was mandatorily re-evaluated as a routine component of patient care. The situational context of clinical decision-making was deemed equivalent to the context of a care-based research intervention with almost no patient contact and minimal associated risk. Thus, in the developed procedural framework the patient’s ability to provide consent is initially evaluated through review of their legal decision-making capacity status. By virtue of existing legal requirements, any patients lacking capacity to make medical decisions for themselves are unable to provide formal informed consent, and must have such consent provided by a LAR.15 For patients lacking capacity formal assent based on previously published standards was obtained.3,6,26

The overarching procedural framework incorporated the capacity assessment and explicitly identified the multiple permutations for obtaining informed consent/assent from hospitalized patients with ADRD or their LAR, as well as the informal caregiver who was often, but not always, the LAR. We applied process mapping to critique and streamline the process of navigating consent requirements and decision-making for the study team, while also critiquing the number and complexity of assessments, forms, and contact points for patients and caregivers.

Results

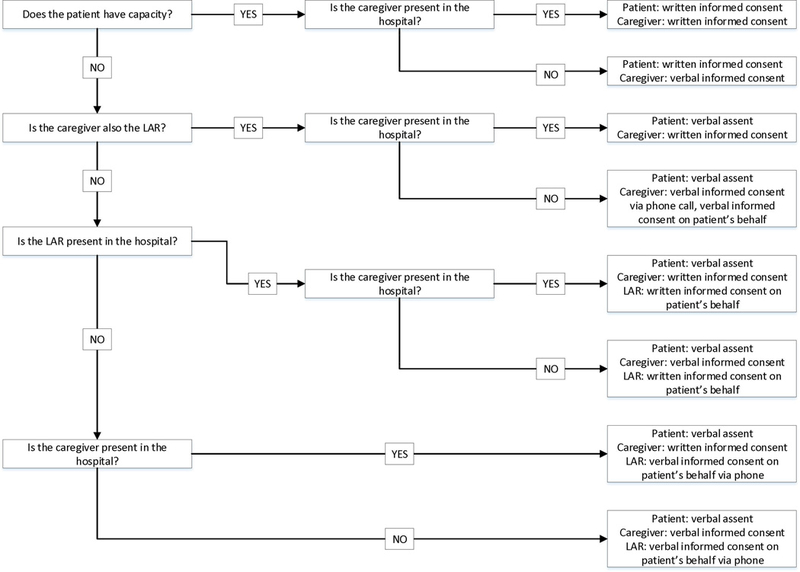

The process map includes eight potential scenarios encountered during the consent process broadly categorized around the patient’s capacity to consent and the physical presence of the LAR and caregiver (Figure 1). In this low risk trial, capacity to consent is determined by a patient’s legal capacity to consent for medical treatment as indicated by an activated HCPOA. Patients with an activated HCPOA are deemed incapacitated to consent for research, and surrogate consent is obtained from the HCPOA as the designated LAR.

Figure 1. Process map for hospital-based informed consent.

For patients who do not have capacity to consent, informed consent is obtained from the LAR, either in-person through written consent or via telephone through verbal consent. To the maximum extent possible, the patient participates in the consent discussion and is given the opportunity to ask questions. Along with surrogate consent, formal assent from the patient is obtained and is tailored to the individual’s cognitive ability and means of expressing preferences, including behavioral and emotional cues as identified in the literature.6 For example, in less verbal patients passive cooperation with activities can suggest implied permission, whereas agitation or restlessness during an interaction can indicate dissent. If feasible, verbal affirmative assent is obtained following a simplified description of the research study and the associated risks, benefits, and alternatives to participation. However, there are situations in which active assent is not possible, such as aphasic individuals or those who lack comprehension of even simplified descriptions of the study. In these situations passive assent is obtained through behavioral cues or a lack of overt dissent based on aberrations from baseline, ideally with input from family and caregivers. For example, a patient who regularly engages with hospital staff but consistently turns away from the research specialist would be suggestive of expressive dissent. Alternatively, if this response is consistent with baseline behaviors and there is no other evidence of distress or opposition then lack of overt dissent could be inferred as passive assent. If the patient dissents, the research team will meet separately with the LAR and caregiver and work together to help address underlying concerns and alleviate any contributing distress prior to reengaging with the patient one additional time. For example, the patient may misconstrue the research specialist as a threat, but will be more receptive with reassurance from a family member. Persistent dissent is respected, regardless of the underlying reasoning, and the patient is not enrolled. Passive assent is continually monitored throughout the study, with active reassessment as needed. If the patient is enrolled following surrogate consent and assent, written or verbal consent is obtained separately from the caregiver.

For patients who have capacity to consent, the patient is provided with the written consent form with appropriate time for discussion and family and caregiver involvement at the discretion of the patient. Patients are monitored for evidence of undue miscomprehension throughout the consent process, including frequent repetition, sustained inattention, frequent misunderstandings, and vague or nonsensical statements. Patients are ineligible for enrollment if there are any concerns regarding retained capacity.

Discussion:

Informed consent is an important mechanism for ethical research inclusivity while safeguarding against potential harm, coercion, exploitation, or undue influence. However, the additional challenges of the informed consent process for hospitalized patients with ADRD risk marginalizing this important patient population from meaningful contributions and resultant benefits of research. Building on established ethical, legal, and regulatory principles, as well as consent protocols for non-acute care settings, we developed a procedural framework to facilitate the informed consent of hospitalized patients and caregivers inclusive of all stages of ADRD to participate in a minimal risk care intervention.26

The procedural framework addresses the four primary challenges of informed consent for persons with ADRD while specifically focusing on the acute care setting where rapid enrollment is necessary. The first challenge is the determination of capacity to provide consent. We utilized a patient’s legal capacity to consent for inpatient medical treatment, as indicated by HCPOA activation, as a proxy to consent for research. Although there are existent tools for comprehensive research-specific capacity assessment, these are impractical to administer in the busy, time-constrained setting of an acute care hospital for studies that pragmatically require rapid hospital-based enrollment and are of minimal risk.31 The use of an activated HCPOA as a proxy for capacity to consent for research specifically capitalizes on the hospital setting where inpatient providers continually assess capacity as a part of usual care for timely medical decision-making. This is of particular importance given the high incidence of delirium and fluctuating cognition in hospitalized patients with ADRD. The capacity assessment for medical decision-making is a well-established standard that is based on independent assessments by two physicians. This integration within the usual care of hospitalized patients streamlines the capacity assessment with minimal interruption to ongoing medical care.

The challenges of surrogate consent for incapacitated patients and LAR identification is also addressed by the procedural framework by utilizing the HCPOA as the LAR providing surrogate consent. Surrogate consent is ideally based on substituted judgment or, barring known preferences, on the standard of best interest. These standards are best approximated by the utilization of the HCPOA as the surrogate, as the HCPOA is the legal representative designated by the patient to make decisions on his or her behalf and selected prior to incapacity. Although the standards of substituted judgment and best interest are difficult to gauge, there is broad public support for surrogate-based research enrollment, with considerable latitude afforded to the surrogate.32,33 In addition, the allowance of verbal consent integrated in the process map allows flexibility and efficiency when obtaining surrogate consent.

The final challenge addressed by the procedural framework is the balancing of an individual’s residual autonomy with the need for surrogate consent. This was addressed by maximally involving the patient, regardless of ADRD stage, in all aspects of the consent process, including both informally through group discussions and formally through informed consent or assent. Assent was individualized based on cognitive ability, baseline behavioral manifestations of ADRD, and personal means of expressing preferences.3,6 In addition, passive assent was continually monitored throughout the study, with active reassessment as needed. Although not utilized in this study, tailored communication aids, such as Talking Mats, visual cue cards, and speech devices, may help facilitate the information sharing and assent process.34,35

There are limitations to the procedural framework. The framework was derived for hospital-based recruitment for a clinical trial with minimal associated risk. The generalizability to ambulatory settings or to studies with greater than minimal risk is uncertain and would merit further investigation. However, this framework allows a degree of adaptability. For example, longer-frame longitudinal studies may institute periodic capacity reevaluations, formal ongoing assent appraisal, and identification and early involvement of a LAR for persons with capacity at enrollment given the progressive nature of ADRD. One of the key development features of this framework was the close collaboration with the IRB to gauge and assuage risk and to ensure appropriate safeguards were in place for participant wellbeing. However, this was inherently a low risk study. Research studies with greater risk may require additional procedural safeguards, such as independent monitors and processes for continuous assent appraisal. In addition, the changing interactions involving risk, surrogate consent, and novel research methodologies require careful consideration in research involving persons with ADRD.21

In summary, we developed a procedural framework for obtaining hospital-based informed consent from patients with ADRD and their caregivers to participate in a minimal risk care intervention. The framework was a multi-disciplinary collaboration with early and ongoing input from the IRB. Persons with ADRD, especially in the late stages, have historically been marginalized from research and the consent process, with potentially serious implications given the rising disease prevalence with an aging demographic, the paucity of effective treatment options, and the growing strain on an ill-equipped health care system. Bolstering research participation through more readily engaged consent procedures during acute illness is critical to fostering improvements in the delivery of high quality care to persons with ADRD. This procedural framework helps address the challenge of an inclusive and participatory research agenda for persons with ADRD, which is a direct reflection of how we value our fellow members of the human race who live with dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin and Peggy Troller, DNP, MSMFT, RN-BC, for collaborating on the development of the procedural framework. The William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin provided additional resources and facility use in support of this work, and the University of Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center provided ongoing institutional and funding support. This project was supported by the National Institute on Aging P50AG033514, by the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, and by the Madison VA Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC-Manuscript #2017–015).

Sponsor’s Role:

The funding organizations for this study had no role in study concept or design, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Funding Sources and Support:

This project was supported by the National Institute on Aging P50AG033514, by the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, and by the Madison VA Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC-Manuscript #2017–015). The William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin provided additional resources and facility use in support of this work. No funding source had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Twitter handles:

TRH: None

SK: None

AK: None

MG: None

ES: None

CH: None

AGB: andrealgilmore

AJK: None

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14(3):367–429. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston G,Sommerlad A, Orgeta V et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slaughter S, Cole D, Jennings E et al. Consent and assent to participate in research from people with dementia. Nurs Ethics 2016;14(1):27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskin SA, Morris J, Ahronheim JC et al. Barriers to obtaining consent in dementia research: Implications for surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Mansfield J. Consent and refusal in dementia research: Conceptual and practical considerations. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003;17 Suppl 1:S17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black BS, Rabins PV, Sugarman J et al. Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. Am J Geriat Psychiat 2010;18(1):77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong TG, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER et al. Adverse outcomes after hospitalization and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med 2012;156(12):848–U121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mecocci P, Strauss von E, Cherubini A et al. Cognitive impairment is the major risk factor for development of geriatric syndromes during hospitalization: Results from the GIFA study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;20(4):262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCauley K, Bradway C, Hirschman KB et al. Studying nursing interventions in acutely ill, cognitively impaired older adults. Am J Nurs 2014;114(10):44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45 - Public Welfare, Part 46: Protection of Human Subjects. Department of Health and Human Services 2009. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html. Accessed November 16, 2017

- 11.Dewing J. From ritual to relationship: A person-centered approach to consent in qualitative research with older people who have dementia. Dementia 2002;1(2):157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillon R. Medical ethics: Four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ 1994;309(6948):184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SYH, Karlawish JH, Kim HM et al. Preservation of the capacity to appoint a proxy decision maker: Implications for dementia research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68(2):214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA 2011;306(4):420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Chapter 1 - U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Part 50, Section 20: Informed Consent of Human Subjects. Department of Health and Human Services 2017. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=50&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:1.0.1.1.20.2. Accessed November 16, 2017.

- 16.Berger JT, DeRenzo EG, Schwartz J. Surrogate decision making: Reconciling ethical theory and clinical practice. Ann Intern Med 2008;149(1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce R. A changing landscape for advance directives in dementia research. Soc Sci Med 2010;70(4):623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong MN, Winkel G, Rhodes R et al. Surrogate consent for research involving adults with impaired decision making: Survey of Institutional Review Board practices. Crit. Care Med 2010;38(11):2146–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzheimer’s Association. Research consent for cognitively impaired adults: Recommendations for Institutional Review Boards and investigators. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2004;18(3):171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AGS Ethics Committee. Informed consent for research on human subjects with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:1308–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post SG. Full-spectrum proxy consent for research participation when persons with Alzheimer disease lose decisional capacities: Research ethics and the common good. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003;17 Suppl 1:S3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Belmont report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research 1979. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 16, 2017. [PubMed]

- 23.Dewing J. Participatory research: A method for process consent with persons who have dementia. Dementia 2007;6(1):11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn LB, Palmer BW. When does therapeutic misconception affect surrogates or subjects decision making about whether to participate in dementia research? AMA J Ethics 2017;19(7):678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects The World Medical Association 1964. Available at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed November 16, 20 [PubMed]

- 26.Batchelor-Aselage M, Amella E, Zapka J, et al. Research with dementia patients in the nursing home setting: A protocol for informed consent and assent. IRB 2014;36(2):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor JS, DeMers SM, Vig EK et al. The disappearing subject: Exclusion of people with cognitive impairment and dementia from geriatrics research. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(3):413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kind AJH, Brenny-Fitzpatrick M, Leahy-Gross K et al. Harnessing protocolized adaptation in dissemination: Successful implementation and sustainment of the Veterans Affairs Coordinated-Transitional Care Program in a non-Veterans Affairs hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64(2):409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oruche UM. Research with cognitively impaired participants. J Nurs Law 2009;13(3):73227162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SYH. Evaluation of Capacity to Consent to Treatment and Research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SY, Caine ED, Currier GW et al. Assessing the competence of persons with Alzheimer’s disease in providing informed consent for participation in research. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(5):712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SYH, Kim HM, Ryan KA et al. How important is “accuracy” of surrogate decision-making for research participation? PLoS ONE 2013;8(1):e54790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SYH, Kim HM, Langa KM et al. Surrogate consent for dementia research: A national survey of older Americans. Neurology 2009;72(2):149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourgeois M, Dijkstra K, Burgio L et al. Memory aids as an augmentative and alternative communication strategy for nursing home residents with dementia. Augment Altern Commun 2009;17(3):196–210. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy J, Oliver T. The use of Talking Mats to support people with dementia and their carers to make decisions together. Health Soc Care Community 2013;21(2):171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]