Abstract

Background:

Survivors of cancer often describe a sense of abandonment post treatment, with heightened uncertainty, and limited knowledge of what lies ahead. This study examined the efficacy of a survivorship care planning intervention to help physicians address survivorship issues through communication skills training plus a new consultation focused on the use of a survivorship care plan for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Methods:

This cluster randomized, four-site trial examined the efficacy of a Survivorship Planning Consultation (SPC; physicians received communication skills training and applied these skills in a survivorship-focused office visit using a survivorship care plan) with patients who achieved complete remission after completion of first-line therapy versus a control arm in which physicians were trained to and subsequently provided a time-controlled, manualized Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation (WRC) focused only on discussion of healthy nutrition and exercise as rehabilitation post-chemotherapy. The primary outcomes for patients were changes in knowledge about lymphoma and adherence to physicians’ recommendations for vaccinations and cancer screenings.

Results:

Forty-two physicians and 198 patients participated across the four sites. Patients whose physicians were in the SPC arm had greater knowledge about their lymphoma (p = 0.01) and had greater adherence to physician recommendations for influenza vaccinations (p = 0.02) and colonoscopy (p = 0.02) than patients whose physicians were in the WRC arm.

Conclusions:

A dedicated consultation using a survivorship care plan and supported by communication skills training may enhance patient knowledge and adherence to some health promotion recommendations.

Keywords: survivorship, lymphoma, knowledge, adherence, communication

Precis

This study examined the efficacy of a survivorship care planning intervention to help physicians address survivorship issues through a new consultation focused on the use of a survivorship care plan for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). A dedicated consultation using a survivorship care plan and supported by communication skills training enhances patient knowledge and adherence to health promotion recommendations.

Many cancer patients feel unprepared for the transition from active treatment to survivorship. The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report on cancer survivorship, “Lost in Transition,” describes the unique quality of care needs for survivors.1 Survivors have many questions and unmet needs (e.g., timing of follow-ups, late and long-term effects of treatment, and other recommended tests/screenings), and are also at risk of recurrence and new cancers.2–5

Many patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) achieve a complete response and go into remission.6–8 Complete response rates are close to 90%, with relatively low relapse rates.9–11 Lymphoma survivors may have many of the challenges described above.12–15 One approach to facilitate this transition, endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and others, is treatment summaries and survivorship care plans (SCPs).16,17 The IOM recommends SCPs for all survivors, including a written summary of the treatment received, health promotion recommendations, and a schedule for monitoring possible recurrence and other treatment-related risks.18 It is believed that an SCP may facilitate the process of initiating and integrating healthy behaviors into daily life.19.20 Improving patients’ understanding of their illness and self-care may enhance adherence with physicians’ recommendations.21

Although SCPs have been shown to be well-received by survivors,22–24 most have failed to demonstrate effects on knowledge and behavior.22 However, exceptions exist. In a study among breast and colorectal cancer survivors, SCPs resulted in increased cancer knowledge,25 and another recent study demonstrated that SCPs coupled with nurse counseling reported greater implementation of recommended breast survivorship care.26 Thus, survivorship care planning is a promising tool to help survivors manage their needs and ensure that they do not fall through the cracks of the health care system,1 but the evidence-base is limited. An important limitation of past studies is that the SCPs were used with patients but physicians were not taught how to best use them with patients. Accordingly, the goal of this trial was to examine the efficacy of a Survivorship Planning Consultation (SPC) with patients who had achieved complete remission. SPC physicians received communication skills training and applied these skills in a new survivorship-focused consultation using an SCP. Physicians in the control arm were trained to and subsequently provided a Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation (WRC) that focused on healthy nutrition and exercise discussion. We previously reported on efficacy of the communication skills training in helping physicians learn skills in introducing SCPs.27 This article describes the two primary research hypotheses--patients of physicians in the SPC arm would exhibit greater increase in knowledge about lymphoma and its treatment and have higher self-reported adherence rates to physician recommendations in the first year of survivorship.

METHODS

Study Design

Participating sites were randomized to either SPC or WRC arms in a cluster-randomized design, which protects against physician contamination of the intervention within any site. We selected two larger and two smaller sites with similar numbers of lymphoma patients, and randomization was stratified by site size. The study was approved by the sites’ Institutional Review Boards. Additional details about study design are published elsewhere.28

Participants and Recruitment

Physicians:

All oncologists on the lymphoma services who saw HL and DLBCL patients received an introduction letter. Interested oncologists proceeded to have a discussion with an investigator from the research team and provided informed consent. Forty-four physicians were screened and consented (22 in SPC and 22 in WRC; 2 physicians in the WRC condition withdrew and did not attend the training). Physicians did not receive compensation.

Patients:

Patients were recruited through their physicians’ clinics. Patients were eligible if they: had a diagnosis of HL or DLBCL and were treated with curative intent; had testing indicating complete remission; were >18 years; and were fluent in English. Patients were ineligible if they showed evidence of significant cognitive impairment or had a prognosis and/or co-morbidities that, in the physician’s judgment, made them inappropriate for participation. Patients were recruited at the time they were informed of remission, and they completed T1 questionnaires before their first post-treatment consultation. Patients completed questionnaires after that visit (1-month follow-up; T2) as well as after their 3 (T3), 6 (T4), 9 (T5) and 12-month (T6) follow-up visits. They were compensated for their time (T2-$20,T3-$30,T4-$40,T5-$50,T6-$60).

Survivorship Planning Consultation

Physicians in the SPC arm completed an in-person, 5-hour communication skills training which included: information about lymphoma survivorship; exemplary videos of recommended communication strategies in a survivorship consultation; survivorship-themed role-plays with standardized patients (trained actors); and a discussion about the benefits and barriers to SCP implementation.27

Then, patients and physicians participated in a brief (15 minute) new consultation, approximately 1 month after the baseline visit, focused on transitioning the patients to survivorship. In this visit, physicians reviewed the scans showing remission status and then reviewed the SCP and facilitated a discussion about survivorship-related concerns and behaviors. The SCP consisted of a summary of the cancer diagnosis and treatments received, treatment-relevant toxicities, frequency of future visits, screening schedule, and review of health promotion behaviors (vaccinations, exercise, nutrition, and smoking cessation). Consultations were audio-recorded for fidelity monitoring.

Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation

Physicians in the WRC arm received an in-person 2-hour training focused only on wellness and lifestyle factors. These physicians had a time-matched consultation with their patients one month after the baseline visit in which they reviewed scans showing remission status and discussed the benefit of healthy nutrition and walking to promote fitness. Consultations were audio-recorded for fidelity monitoring.

Fidelity

Fidelity monitoring was conducted using the Transition to Survivorship Coding Schema (SPC)27 and a checklist describing the prescribed behaviors related to healthy nutrition and exercise (WRC).28 The goal of the fidelity assessment was to ensure that physician consultations were standardized.

In both arms, following the T2 visit, all physicians received an email describing strengths and focusing on topics to discuss with patients in use of SCP or healthy nutrition and exercise handout, respectively. After the physicians’ next two visits, they received a follow-up phone call if their fidelity score to the prescribed behaviors related to the study condition was <80% of recommended behaviors (n=17 or 41%). Following the fourth visit, all physicians received an email thanking them for their participation, asking about any concerns, and providing constructive feedback if needed. Following the fifth, sixth, and seventh visits, physicians got a follow up phone call if their adherence score was <80% of recommended behaviors (n=6 or 14%).

Assessment and Evaluation Plan

Assessment of Physicians

SPC physicians participated in pre- and post-training Standardized Patient Assessments, a reliable assessment with discriminant validity.29,30 Blinded coding was completed using the Comskil Coding System and the Specific Coding Schema for Skills, Strategies and Process Tasks.27 There was a significant uptake in communication skills from pre- to post-training.27

Assessment of Patients

Demographics: At baseline, patients provided following information: work status, marital status, education, race, and ethnicity.

Lymphoma Knowledge Questionnaire: This 50-item questionnaire examined knowledge about lymphoma, treatment, long-term and late effects, and prognosis and health recommendations (content from NCI website).28 It was validated on 320 lymphoma survivors (6 months–6 years post-treatment), with an average score of 22.8 (SD=9.1) correct. Items were True/False with a Don’t Know option and the knowledge score was a sum of total correct answers (Range 0–50), with missing counted as incorrect. It was administered at baseline, 1, 3, and 12 months and was scored if at least one item was answered.

Employment and Health Services Questionnaire-Adherence (EHSQ): A subscale of the EHSQ assessed adherence to recommended vaccinations and screening tests.28 We assessed seven preventative and screening behaviors (mammogram, PAP, colonoscopy or fecal occult blood test (FOBT), flu vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination, skin screening, and annual PCP visit). Patients reported adherence at 3, 6, 9 and 12 month-follow-ups. We assessed completion of these behaviors and dates for colonoscopy, PAP, and mammogram, if reported. We combined colonoscopy and FOBT as a single indicator of colorectal cancer screening.

STATISTICAL PLAN

Increase in knowledge was analyzed longitudinally using 3-level hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), with levels for assessment, patient, and site. The primary HLM for knowledge included 2 fixed effects on baseline knowledge and treatment arm (e.g., SPC or WRC). Random intercepts for both patient and site were included to adjust for correlation introduced by repeated measures. Each patient contributed up to three time-points. Three additional fixed-effect predictors were considered: 1) main effect of assessment time point (3 levels); 2) time by treatment interaction; and 3) quadratic time effect. The general form of the models was thus:

where the knowledge score for the ith person, within the jth site, at the t timepoint was regressed on random person and site effects, as well as baseline knowledge and a treatment indicator, plus additional predictors as listed above. Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) were used for model comparison between the primary model and the inclusion of additional predictors. We used an intent-to-treat approach in comparing the two study arms. Models present unadjusted associations, though similar effects were found in models adjusted for demographic covariates.

Sample size calculations for this study were based on the ability to collect longitudinal patient-level data from at least 224 patients (of 256 enrolled), to detect an intervention effect of 0.61 in standardized mean difference scores (Cohen’s d)31 between the study arms, with an assumed Intra-Class Correlation of 0.10 among patients nested within physicians, at a two-sided Type-I error rate of 0.01 to provide some control of multiple comparisons on the outcomes of knowledge and adherence.32

Each adherence outcome was assessed both as a logit outcome in a Generalized HLM, and via Cox proportional hazards models to incorporate differential follow-up time for the adherence measures. In logistic HLM models, adherence for each outcome is treated as a single binary outcome and patients were considered non-adherent unless they affirmed adherence. The general form for the logistic model was where adherence for the ith person, within the jth site was regressed on random site effects and an indicator for SPC arm. In proportional hazards models no failures were imputed, rather patients contributed a unique measure of follow-up time, as well as an indicator of whether the outcome was successful at the time final assessment; thus, the proportional hazards model incorporated differential attrition. To adjust for site effects, the robust sandwich variance estimator for proportional hazards models is used, as developed by Lee et al.33 These separate models allow a more complete analysis of the data, both with and without imputed failures, and were fitted for each of the seven behaviors. Patient profiles that did not meet United States Preventive Services Task Force general requirements for the screening were excluded; specifically, only women over 40 were included for mammograms, women under 65 for PAP, and patients between the ages of 50 and 75 for colonoscopy or FOBT. The statistical package SAS, version 9.4 was used.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

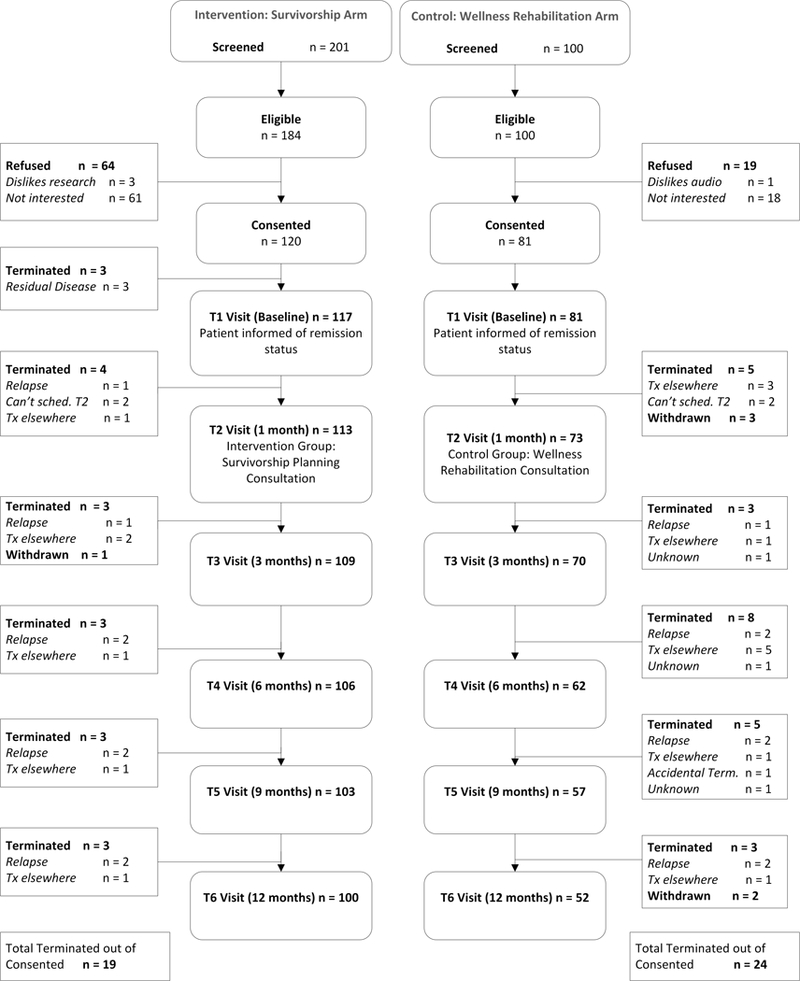

Forty-two physicians were enrolled across the four sites (22 SPC and 20 WRC) (Table 1). One hundred ninety-eight patients were enrolled; 117 (59%) at SPC sites and 81 (41%) at WRC sites (Figure 1). Patients were largely White, non-Hispanic, and evenly distributed by gender and between earlier and later stages at diagnosis (51% stages 1,2 and 48% stages 3,4). Patient age ranged from 18 to 87 years (see Table 2). Attrition did not differ between the arms by patient characteristics at any timepoint, though the SPC participants provided more complete data at the last 3 time-points (T4: p=0.01; T5 and T6: p<0.01). Intermittent missingness also did not differ by patient or disease characteristics such that patients who completed all surveys were comparable to patients who missed at least one (all p>0.10).

Table 1.

Physicians’ Descriptive Characteristics (N = 42)

| Characteristic | Value | SPC n = 22 % |

WRC n = 20 % |

All n = 42 % |

Characteristic | Value | SPC n = 22 % |

WRC n = 20 % |

All n = 42 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 41 | 25 | 33 | Percent Time | >10% to 25% | 0 | 10 | 5 |

| Male | 59 | 75 | 67 | Clinical | >25% to 50% | 45 | 5 | 26 | |

| >50% to 75% | 23 | 45 | 33 | ||||||

| Age | 30–39 | 18 | 25 | 21 | >75% to 90% | 14 | 30 | 21 | |

| 40–49 | 23 | 20 | 21 | >90% to 100% | 9 | 5 | 7 | ||

| 50–59 | 27 | 35 | 31 | Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 | ||

| 60+ | 23 | 15 | 19 | ||||||

| Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 | Percent Time | 10% or less | 32 | 65 | 48 | |

| Research | >10% to 25% | 18 | 15 | 17 | |||||

| Years | 5 or fewer | 14 | 15 | 14 | >25% to 50% | 41 | 10 | 26 | |

| Practicing | 6–10 | 14 | 15 | 14 | >50% to 75% | 0 | 5 | 2 | |

| 11–20 | 32 | 35 | 33 | Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 | ||

| More than 20 | 32 | 30 | 31 | ||||||

| Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 | Percent Time | 10% or less | 68 | 60 | 64 | |

| Teaching | >10% to 25% | 14 | 35 | 24 | |||||

| Annual no. | <20 | 59 | 75 | 67 | >25% to 50% | 5 | 0 | 2 | |

| Hodgkins | 20–29 | 18 | 20 | 19 | Missing | 14 | 5 | 10 | |

| 40–99 | 5 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| 100+ | 9 | 0 | 5 | Percent Time | 10% or less | 68 | 80 | 74 | |

| Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 | Admin | >10% to 25% | 18 | 10 | 14 | |

| >75% to 90% | 0 | 5 | 2 | ||||||

| Annual no. | <20 | 36 | 65 | 50 | >90% to 100% | 5 | 0 | 2 | |

| Diffuse | 20–29 | 23 | 10 | 17 | Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 | |

| Large B cell | 40–99 | 18 | 20 | 19 | |||||

| 100+ | 14 | 0 | 7 | ||||||

| Missing | 9 | 5 | 7 |

Note: SPC=Survivorship Planning Consultation, WRC=Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation. Arms only differed by number of Diffuse Large B cell.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and Participation Rates by Study Arm

Table 2.

Patients’ Descriptive Characteristics (N = 198)

| Characteristic | Value | SPC n = 119 % |

WRC n = 80 % |

All n = 198 % |

Characteristic | Value | SPC n = 119 % |

WRC n = 80 % |

All n = 198 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 55 | 44 | 51 | Employment | Employed | 43 | 35 | 40 |

| Male | 42 | 54 | 47 | Unemployed | 7 | 15 | 10 | ||

| Missing | 3 | 3 | 3 | Disability | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Retired | 15 | 23 | 18 | ||||||

| Age | <30 | 31 | 20 | 27 | Student | 7 | 4 | 6 | |

| 30–39 | 16 | 18 | 17 | Missing | 20 | 16 | 19 | ||

| 40–49 | 14 | 14 | 14 | ||||||

| 50+ | 37 | 48 | 41 |

Marital Status |

Married | 41 | 46 | 43 | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 2 | Single | 31 | 18 | 26 | ||

| Divorced | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Race | White not Hispanic | 58 | 48 | 54 | Widowed | 3 | 9 | 5 | |

| Black | 8 | 10 | 9 | Married/Lives with Partner |

3 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Asian | 6 | 9 | 7 | Missing | 18 | 16 | 17 | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 8 | 4 | ||||||

| White/Hispanic | 6 | 9 | 7 | Stage at Dx | 1 | 13 | 11 | 12 | |

| Other | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 42 | 35 | 39 | ||

| Missing | 18 | 18 | 18 | 3 | 25 | 26 | 26 | ||

| 4 | 18 | 26 | 22 | ||||||

| Education | Middle School | 2 | 1 | 2 | Missing | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| HS graduate | 10 | 15 | 12 | ||||||

| College | 41 | 35 | 39 | ||||||

| Postgraduate | 19 | 11 | 16 | ||||||

| Missing | 28 | 38 | 32 |

Note: SPC=Survivorship Planning Consultation. WRC=Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation. HS=High School. Only marital status differed by arm (p=0.0601).

Knowledge

Patient baseline knowledge scores ranged from 3 to 40 (M=22.2, SD=6.7) with no difference by treatment arm, and with intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.03 for the clinics. Patients in both arms had increases in knowledge over time; at 1 month the SPC patients had an average increase of 4.1 points and WRC patients had an average increase of 1.3 points. These increases were sustained through 12 months (Table 3). After adjustment for baseline knowledge and random participant and site effects, participants in the SPC arm had an average increase in knowledge of 2.36 points (F(1, 232)=6.70, p=0.01, 95% CI=[0.54, 4.18]) more than the increase for WRC participants. Model fit comparisons determined a model with baseline knowledge, study arm, and time to be the best fit, though all models under consideration (i.e., models with linear and quadratic time effects, and the model with an arm by time interaction) showed a significant effect of treatment arm.

Table 3.

Change in Knowledge by Study Arm.

| Arm | Measure | Baseline | 1 month | 3 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPC | M (SD) | 22.2 (6.7) | 26.4 (6.9) | 25.4 (6.7) | 25.9 (6.7) |

| Change from baseline (SD) |

- | 4.1 (5.9) | 3.4 (6.3) | 3.7 (5.7) | |

| n | 97 | 84 | 80 | 75 | |

| WRC | M (SD) | 22.2 (7.8) | 23.5 (7.2) | 23.6 (7.4) | 24.3 (8.8) |

| Change from baseline (SD) |

- | 1.3 (4.7) | 1.9 (7.1) | 1.9 (7.5) | |

| n | 65 | 59 | 46 | 40 | |

| All | M | 22.2 (7.1) | 25.2 (7.1) | 24.8 (7.0) | 25.3 (7.5) |

| Change from baseline (SD) |

- | 2.9 (5.6) | 2.8 (6.6) | 3.1 (6.4) | |

| n | 162 | 143 | 126 | 115 |

Note: SPC=Survivorship Planning Consultation. WRC=Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation. M=Mean, SD=standard deviation. An HLM model was used to compared follow-up knowledge scores between SPC and WRC patients; on average, SPC patients had a 2.36 point higher follow-up score (p = 0.01) than comparable WRC patients.

Adherence

Among women over age 40, 52% reported receiving a mammogram, and 39% of women under 65 years reported receiving a PAP, during the followup year. Among patients 50–75 years, 9% reported receiving a colonoscopy or FOBT. For all participants, 50%, 14%, 16%, and 34% reported receiving a flu vaccine, a pneumococcal vaccine, a skin cancer screening from a dermatologist, and a PCP annual exam, respectively. Both logistic HLM and proportional hazards models showed that SPC patients were more than twice as likely to get a flu vaccine compared to WRC patients (OR=2.42; 95% CI=[1.16, 5.02, logistic model]). Colorectal cancer screening rates could not be compared via models since no patients aged 50–75 in the WRC group completed colonoscopy or FOBT, however an exact Chi-square test of the overall counts found the observed difference to be statistically significant (p=0.016). Notably, proportional hazards models of the adherence outcomes were also used to assess effects of baseline knowledge, but due to no significant findings, knowledge was not used as a covariate in the final models for adherence (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Adherence by Study Arm.

| Measure | Arm | n eligible |

n adher (%) | Logistic HLM OR (95% CI) |

PH Model HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography | SPC | 38 | 20 (53%) | 1.13 (0.31, 4.11) | 1.13 (0.41, 3.14) |

| WRC | 18 | 9 (50%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 56 | 29 (52%) | - | - | |

| PAP | SPC | 52 | 20 (38%) | 0.96 (0.29, 3.14) | 1.06 (0.24, 4.67) |

| WRC | 27 | 11 (41%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 79 | 31 (39%) | - | - | |

| Colonoscopy/ FOBT | SPC | 42 | 7 (17%) | NaN | NaN |

| WRC | 33 | 0 (0%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 75 | 7 (9%) | - | - | |

| Flu vaccine | SPC | 119 | 69 (58%) | 2.42 (1.16, 5.02) | 1.69 (1.04, 2.77) |

| WRC | 80 | 31 (39%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 198 | 100 (50%) | - | - | |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | SPC | 119 | 16 (13%) | 0.95 (0.39, 2.32) | 0.91 (0.51, 1.63) |

| WRC | 80 | 11 (14%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 198 | 27 (14%) | - | - | |

| Skin Exam | SPC | 119 | 19 (16%) | 1.08 (0.49, 2.38) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.13) |

| WRC | 80 | 12 (15%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 198 | 31 (16%) | - | - | |

| PCP Annual | SPC | 119 | 40 (34%) | 0.94 (0.52, 1.72) | 1.12 (0.66, 1.89) |

| WRC | 80 | 28 (35%) | REF | REF | |

| All | 198 | 68 (34%) | - | - |

Note: SPC=Survivorship Planning Consultation. WRC=Wellness Rehabilitation Consultation. Adher=adherence. PAP=Papanicolaou test. FOBT=fecal occult blood test. PCP=primary care provider. Models for colonoscopy/ FOBT could not be estimated due to zero events in the WRC group.

DISCUSSION

SCPs have been conceptualized as helpful to patients by enhancing their knowledge and management of the disease, and awareness of late and long-term side-effects through active screening and health monitoring. Documented evidence for these presumed benefits has been minimal. We tested the use of a new consultation to provide SCPs to patients, and utilized communication skills training as the means to ensure physician comfort and efficiency with this approach. Our results suggest that patients may benefit from survivorship dedicated consultations in terms of improved knowledge and some increased uptake of recommended screening and vaccination behaviors. Evaluating whether the change in knowledge is clinically significant is challenging. Using a frequently suggested criterion of ½ standard deviation34 the SPC patients exhibit a clinically significant change in knowledge that WRC patients did not. The relative differences between SPC and WRC arms were slightly smaller. Revicki et al.35 propose using the effect size to evaluate clinical significance. Using this criterion, the effect size for the difference in knowledge between arms was 0.33 (small to medium effect size). Growth in knowledge about one’s illness is the necessary first step in improved health literacy to empower enhanced health promotion and self-care.

Influenza vaccine is one clear recommendation made for the first year of survivorship after treatment of lymphoma. This was a behavioral gain following the use of a SCP, however, the impact of rituximab on patient immunity leads physicians to generally wait until year two to recommend the pneumococcal vaccine, a reality that lay outside our follow-up time line which is why we did not see improved rates of pneumococcal vaccination. Colonoscopy screening improved, but other behaviors such as mammography and PAP smears did not. Our adherence outcome data were limited by the short follow up time in this study and the timing and variations in when screening or vaccinations were due.

There are many informational gaps identified in patients after active treatment (2–4) and there is great variability in the content of the discussions patients have with their providers.5 Our results demonstrate that a targeted new visit may be beneficial. There is compelling evidence in literature about the value of being sufficiently informed or educated about one’s health condition and care as lack of such understanding can result in non-compliance to physician recommendations, thereby adversely affecting patient outcomes.36–38

The quality of this consultation was likely enhanced by our multi-level intervention approach–not only did we intervene at the system level (new consultation) but also at the provider level. The training included how to effectively use the SCP. Other studies without the communication skills training component have typically shown that, although patients are satisfied with the SCPs, their use has not resulted in other positive outcomes.6 Although some educational and communication intervention studies have been found to increase knowledge,39,40 research has been mixed about whether they result in improvements in behavior.41.42 Importantly, our study found positive effects on both of these key outcomes (knowledge and behavior).

This study had some limitations. First, participants were primarily Caucasian and English-speaking. There may have been some differences between the sites that may affect the outcomes. However, each site had diversity in physician experience and in types of lymphoma but comparisons between physicians in each arm was similar except there was a marginal difference in number of patients with DLBCL. Additional studies should focus on more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse populations, and in community hospitals, to determine if a similar intervention would be effective. Having co-morbidities that could limit participation was an eligibility criterion. This could have biased our results however, this criterion was not mentioned as a reason to not approach patients, so it is unlikely. Physician also had to be interested and willing to participate which could bias results, although we had full participation at all sites. Our adherence outcome data were also limited by dropouts and potential under-estimation, as only 46% of patients in the WRC and 55% in the SPC arm completed all follow-up surveys, and we did not have detailed data for these outcomes (e.g., total hysterectomy negating the need for PAP). However, our use of a time-to-event analysis and the analysis of dichotomous outcomes mitigated some of the dropout issue and we do not believe there was differential underestimation of adherence by arm. Therefore, we believe the group comparison is valid. It should also be recognized that this study only included 4 sites which may limit its generalizability. However, we included both larger volume and smaller volume sites and provided data on patients and physicians to fully describe the study sites. Though physicians between arms were largely comparable, there was a noticeable difference in percent of time the physicians spent in clinical pratice. Although clinician effects are adjusted for in the random intercept models, the effects may not be completely disentangled if this represents a fundamental difference between the participating sites. This was a generally brief intervention and fidelity to some components of the consultation was somewhat low. A longer intervention might enhance fidelity, however, might also limit physicians’ interest in participating in the program.

What was innovative about this design was the dedicated use of new consultation focused on cancer survivorship. We believe that this is justified, and we plan to evaluate its cost-effectiveness. Although other types of clinicians may also provide survivorship care, this intervention was targeted at oncologists as they typically meet with patients to discuss completion of treatment and we believe they are ideally positioned for these initial survivorship conversations. These survivorship consultations occurred in the regular outpatient clinic run by each physician. However, follow-up screening and vaccinations were left to patient’s primary care or family practitioner to complete. Consultations were covered by each patient’s usual health insurance. Future studies could examine the effects of the training on patients’ psychosocial adjustment and quality of life and the utility of making the training available in online modules to facilitate physicians’ ability to obtain the training to enhance generalizability.

This novel SPC intervention has the potential to enhance the survivorship experience for patients who recently received news of being “cancer free” and may be unprepared for this transition. SCPs have many elements and warrant dedicated consultations to empower the patients and help them discuss and understand the variety of survivorship issues they may encounter. This model could subsequently be modified for use with other cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgment: This research was supported by National Cancer Institute (R01 CA 151899, Co-PIs D Kissane and S Horwitz) and the Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG-Core Grant; P30 CA008748; PI: Craig B. Thompson, MD) from the National Institutes of Health.

www.clinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01483664

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine: From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman D, Shigemasa S: Cancer survivorship requires long-term follow-up. Hawaii Med J 2007: 66:104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz PA, Casillas J, Hahn EE: Ensuring Quality Care for Cancer Survivors: Implementing the Survivorship Care Plan. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 24:208–217, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnipper HH: Life after breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003: 21:104s–107s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parry C, Lomax JB, Morningstar EA, et al. : Identification and correlates of unmet service needs in adult leukemia and lymphoma survivors after treatment. J Oncol Pract 2012: 8:e135–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connors JM: State-of-the-art therapeutics: Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005: 23:6400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, et al. : The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007: 109:1857–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochenderfer JN, Somerville RPT, Lu T, et al. : Long-Duration Complete Remissions of Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma after Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy. Molecular Therapy, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. : Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA:Cancer J Clinicians 2016: 66:271–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moskowitz CH, Schöder H, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. : Risk-Adapted Dose-Dense Immunochemotherapy Determined by Interim FDG-PET in Advanced-Stage Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2010: 28:1896–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Maeda LS, et al. : Dose-Adjusted EPOCH-Rituximab Therapy in Primary Mediastinal B-Cell Lymphoma. New Eng J Med 2013: 368:1408–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baxi SS, Matasar MJ: State-of-the-art issues in Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivorship. Curr Oncol Rep 2010: 12:366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangavarapu LS, Surapaneni R: Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Survivorship: Risk of Second Malignancies in Long Term Survivors. Blood 2015: 126:3921–3921. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng AK: Current survivorship recommendations for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma: focus on late effects. Blood 2014: 124:3373–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernsler J, Fanuele JS: Lymphomas: long-term sequelae and survivorship issues. Semin Oncol Nurs 1998: 14:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: Achieving High-Quality Cancer Survivorship Care. J Clin Oncol 2013: 31:631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Surgeons: Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care (ed 2016). Chicago, IL, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine: Cancer Survivorship Care Planning Fact Sheet, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aziz NM, Oeffinger KC, Brooks S, et al. : Comprehensive long-term follow-up programs for pediatric cancer survivors. Cancer 2006: 107:841–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eiser C: Beyond survival: quality of life and follow-up after childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol 2007: 32:1140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atreja A, Bellam N, Levy SR: Strategies to ehance patient adherence: Making it simple. Medscape Gen Med 2005: 7:4–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan M, Gormally J, Butow P, et al. : Survivorship care plans in cancer: a systematic review of care plan outcomes. Brit J Cancer 2014: 111:1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolte L, Kinnane N, Lai-Kwon J, et al. : The impact of survivorship care planning on patients, general practitioners and hospital-based staff. Cancer Nursing 2016: 39:E26–E35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. : Evaluating Survivorship Care Plans: Results of a Randomized, Clinical Trial of Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011: 29:4755–4762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nissen MJ, Tsai ML, Blaes AH, et al. : Effectiveness of treatment summaries in increasing breast and colorectal cancer survivors’ knowledge about their diagnosis and treatment. J Cancer Survivor 2013: 7:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maly R, Lian L, Liu Y, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of survivorship care plans among low-income, predominantly Latina breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2017: 35:1814–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee SC, Matasar MJ, Bylund CL, et al. : Survivorship care planning after participation in communication skills training intervention for a consultation about lymphoma survivorship. Transl Behav Med 2015: 5:393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker PA, Banerjee SC, Matasar MJ, et al. : Protocol for a cluster randomised trial of a communication skills intervention for physicians to facilitate survivorship transition in patients with lymphoma. BMJ Open 2016:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bylund CL, Brown R, Gueguen JA, et al. : The implementation and assessment of a comprehensive communication skills training curriculum for oncologists. Psychooncology 2010: 19:583–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Johnson SB, et al. : Use of an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) to measure improvement in clinical competence during the surgical internship. Surg 1993: 114:343–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J: Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donner A, Klar N: Design and analysis of cluster randomized trials in health research New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee E, Wei L, Amato D: Cox-Type Regression Analysis for Large Numbers of Small Groups of Correlated Fatigure Time Observations Netherlands, Kluwer Academic, 1992. pp. 237–247 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW: Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 2003: 41:582–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Revicki D, Cella D, Hays R, et al. : Responsiveness and minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006: 4:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Husson O, Holterhues C, Mols F, et al. : Melanoma survivors are dissatisfied with perceived information about their diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care. Brit J Dermatol 2010: 163:879–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG: Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors’ satisfaction with information. Pat Educat Counsel 2005: 57:342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed SC, Walker R, Ziebell R, et al. : Cancer Survivors’ Reported Discussions with Health Care Providers About Follow-Up Care and Receipt of Written Care Plans. J Cancer Educat, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams RJ: Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manage Healthcare Pol 2010: 3:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan G, Everson S, Lynch J: The contribution of social and behavioral research to an understanding of the distribution of disease: a multilevel approach, in Smedley B, Syme S (eds): Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine: Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee HY, Koopmeiners JS, Rhee TG, et al. : Mobile Phone Text Messaging Intervention for Cervical Cancer Screening: Changes in Knowledge and Behavior Pre-Post Intervention. J Med Internet Res 2014: 16:e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]