Abstract

Background:

Many women with opioid use disorder (OUD) do not use highly effective postpartum contraception such as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). We evaluated factors associated with prenatal intent and postpartum receipt of LARC among women receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for OUD.

Study design:

This was a retrospective cohort study of 791 pregnant women with OUD on MAT who delivered at an academic institution without immediate postpartum LARC services between 2009 and 2012. LARC intent was defined as a documented plan for postpartum LARC during pregnancy and LARC receipt was defined as documentation of LARC placement by 8 weeks postpartum. We organized contraceptive methods into five categories: LARC, female sterilization, short-acting methods, barrier methods and no documented method. Multivariable logistic regression identified characteristics predictive of prenatal LARC intent and postpartum LARC receipt.

Results:

Among 791 pregnant women with OUD on MAT, 275 (34.8%) intended to use postpartum LARC and only 237 (29.9%) attended the postpartum visit. Among 275 women with prenatal LARC intent, 124 (45.1%) attended their postpartum visit and 50 (18.2%) received a postpartum LARC. Prenatal contraceptive counseling (OR 6.67; 95% CI 3.21, 13.89) was positively associated with LARC intent. Conversely, older age (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.91, 0.98) and private practice provider (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.32, 0.72) were negatively associated with LARC intent. Although parity was not predictive of LARC intent, primiparous patients (CI 0.49; 95% CI 0.26, 0.97) were less likely to receive postpartum LARC.

Conclusions:

Discrepancies exist between prenatal intent and postpartum receipt of LARC among pregnant women with OUD on MAT. Immediate postpartum LARC services may reduce LARC access barriers.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, pregnancy, postpartum contraception, long-acting reversible contraception

1. Introduction

The reproductive health needs of a growing population of reproductive-aged women with opioid use disorder (OUD) are largely unmet. The rate of unintended pregnancy among women with OUD is twice that of the general population and is perpetuated by low rates of highly effective contraceptive use [1, 2]. In an evaluation of over 200 women enrolled in opioid treatment programs, only half of sexually active women who were not trying to get pregnant, used a contraceptive method [3]. Likewise, in a systematic review of contraceptive use among women with substance use disorders, condoms were the most common method used, and less than 10% of women reported the use of highly effective contraceptive methods such as long- acting reversible contraception (LARC) [4].

Increased healthcare utilization and enhanced patient engagement during pregnancy and the postpartum period provide a unique opportunity to address the reproductive health needs of women with OUD including increasing access to LARC methods [5]. Despite this, contraception utilization in the postpartum period remains low. In a recent evaluation of postpartum contraceptive use among 7,000 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD, only 25% of women had a pharmacy claim for a contraceptive method in the first 3 months postpartum, and less than 2% received a LARC method [6]. These rates are significantly lower than the postpartum contraceptive use rate (47.5%) and highly effective contraceptive use rate (16.4%) found among non-OUD Medicaid-enrolled women [7]. Beyond low prevalence rates, factors contributing to the underutilization of highly effective postpartum contraception remain largely unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate factors that may contribute to prenatal intent and postpartum receipt of LARC among a retrospective cohort of pregnant women receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for OUD.

2. Methods

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of pregnant women with OUD on MAT and who delivered an infant at Magee-Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, an urban, academic medical center between 2009 and 2012 [8, 9]. We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes for opioid dependence (304.0×) to identify the cohort and then extracted information regarding demographics, obstetric history, medical and psychosocial co-morbidities, substance use history, healthcare utilization patterns and contraceptive method choice from the medical record via chart abstraction. Prior to analysis, we validated the dataset through a double entry process whereby research staff experienced in medical record extraction individually and separately extracted each variable into two separate databases which were then merged and analyzed for discrepancies. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the study.

2.1. Patient characteristics

All patients in our sample met DSM-V criteria for OUD which was verified during medical record review. Further, all patients received MAT with either methadone or buprenorphine at the time of delivery. Patients who used methadone received their medication from federally licensed methadone treatment facilities in the metropolitan area. Patients who used buprenorphine received their medication in an office-based setting from a variety of buprenorphine providers in the metropolitan area. Tobacco use was defined as use at any time during pregnancy and polysubstance use was defined as ≥ one positive urinary toxicology screen for illicit drugs (i.e. amphetamine, barbiturate, cocaine, non-prescription use of benzodiazepines, marijuana) at any time during pregnancy. A maternal psychiatric disorder was defined as the medical record documentation of a psychiatric disorder at any time before or during pregnancy. The composite variable, “maternal psychosocial risk factors”, was created to include the presence of at least one of the following maternal psychosocial risk factors: prostitution, probation, arrest, incarceration, homelessness, physical or sexual abuse or having had a child removed from maternal custody. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was defined as documentation of either a positive anti-HCV antibody test or a provider discussion regarding a known HCV positive diagnosis during pregnancy. Breastfeeding was defined as documentation of any breastfeeding during the inpatient hospitalization for obstetric delivery.

2.2. Contraception and healthcare utilization

Contraceptive counseling, contraceptive plans and LARC receipt were extracted from the medical record. We defined prenatal contraceptive counseling as the documentation of contraceptive counseling or the documentation of a plan for a contraceptive method in prenatal provider progress notes. We defined prenatal LARC intent as the documentation of a plan to use a postpartum LARC method at any time during pregnancy. We defined the contraceptive plan at delivery as the documentation of a contraceptive method choice in the medical record prior to discharge from obstetric delivery. Between 2009–2012, our institution did not provide immediate postpartum LARC services. We defined the postpartum contraceptive plan as the documented contraceptive method choice at the postpartum visit within 8 weeks after delivery and postpartum LARC receipt as documentation of the placement of a LARC method.

We organized contraceptive methods into five categories: LARC, short-acting methods, barrier methods, female sterilization and no documented contraceptive plan identified. LARC methods included the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD), the copper T380A IUD and the subdermal contraceptive implant. Short-acting methods included user-dependent, hormonal methods such as the contraceptive injection, patch, vaginal ring, and combined (estrogen and progesterone) and progesterone-only pills. Barrier methods included condoms, and female sterilization included postpartum abdominal tubal ligation.

Postpartum visit attendance was defined as a visit with a healthcare provider within 8 weeks postpartum. Academic teaching service prenatal providers included obstetrics and gynecology resident physicians and certified nurse midwives who were supervised by attending obstetrics and gynecology physicians at our institution. Private practice providers included obstetrics and gynecology attending physicians who were part of three large community practices affiliated with our institution.

2.3. Data Analysis

We described demographic characteristics, healthcare utilization patterns and contraceptive method choice of patients at delivery and in the postpartum period using descriptive statistics. Chi square and t-tests were used to evaluate each variable’s association with LARC intent and receipt. In multivariable analyses, we used stepwise logistic regression with backward elimination based on the P values of the coefficient estimates (P values < 10) to develop two predictive models: one model to identify predictors of prenatal LARC intent and a second model to identify predictors of postpartum LARC receipt. [10] For each model, we removed one predictor with the highest p-value from the model, refit the model with remaining predictors, and then removed another predictor with the highest p-value from the revised model. We repeated this procedure until the p-values of all predictors were less than 0.10 and designated this as the final model. Variables used for our multivariate predictive models based on their statistical significance in bivariate analyses, clinical relevance and collinearity among the variables. Due to multicollinearity among the variables “contraceptive plan at delivery,” “postpartum visit attendance,” and “LARC intent,” and postpartum LARC receipt, these variables were excluded from the multivariable model developed to predict LARC receipt. Missing values were excluded from the analysis and a P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with STATA® 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

3. Results

The characteristics of pregnant women with OUD on MAT in our cohort are presented in Table 1. Most patients were Caucasian, single, unemployed, had a high school education, were Medicaid insured and multiparous. While all patients received MAT during their pregnancy,

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women with OUD on MAT at Magee-Womens Hospital between 2009–2012, by prenatal LARC intent, n=791.a

| LARC intent | No LARC | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=275 | intent | ||

| n=516 | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age [years; mean (±SD)] | 26.9 (±4.5) | 27.5 (±4.8) | 0.07 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 263 (96.7) | 497 (97.1) | 0.77 |

| Other | 9(3.3) | 15 (2.9) | |

| Married | 31 (11.4) | 68 (13.4) | 0.42 |

| Employed | 40(14.6) | 94 (18.2) | 0.19 |

| Education | |||

| ≤HS/GED | 136 (67.3) | 248 (64.8) | 0.26 |

| Some college/Associates degree | 51 (25.3) | 116(30.3) | |

| ≥Bachelor’s | 15 (7.4) | 19(4.9) | |

| Medicaid | 264 (96.0) | 493 (95.5) | 0.76 |

| Primiparous | 96 (34.9) | 175 (33.9) | 0.78 |

| Breastfeedingb | 112 (40.9) | 183 (35.5) | 0.28 |

| Healthcare Utilization | |||

| Prenatal visit attendance [# of visits; | 8.34 (±3.8) | 8.02 (±4.1) | 0.31 |

| mean (±SD)] | |||

| Prenatal contraceptive counseling | 266 (96.7) | 365 (70.7) | <0.01 |

| Prenatal care provider type | |||

| Academic Teaching Service | 220 (43.6) | 285 (56.4) | <0.01 |

| Private Practice | 55 (19.2) | 231 (80.8) | |

| Postpartum visit attendance | 124 (45.1) | 113 (21.9) | <0.01 |

| Medical & Psychosocial Co-morbidities | |||

| Maternal psychosocial risk factors | 155 (56.4) | 261 (50.6) | 0.12 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 210 (76.4) | 366 (70.9) | 0.10 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2 (0.7) | 6(1.2) | 0.56 |

| Gestational hypertensive disorder | 30(10.9) | 23 (4.5) | <0.01 |

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | 119 (43.3) | 250 (48.5) | 0.17 |

| Substance Use History | |||

| Tobacco | 222 (80.7) | 437 (84.7) | 0.16 |

| Polysubstance usec | 145 (52.7) | 255 (49.4) | 0.38 |

| Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) | |||

| Buprenorphine | 45 (16.4) | 115 (22.3) | 0.05 |

| Methadone | 230 (83.6) | 401 (77.7) | |

| Contraceptive Plan at Delivery | |||

| Short-acting method | 95 (34.3) | 182 (35.3) | <0.01 |

| Barrier method | 21 (7.6) | 19(3.7) | |

| Female sterilization | 0(0) | 52 (10.1) | |

| No documented contraceptive plan | 159 (57.8) | 263 (50.9) | |

n (%) unless otherwise indicated and less than 1.0% missing data for all variables except education with 26.0% missing data;

any documentation of breastfeeding prior to hospital discharge;

history of cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana and/or benzodiazepine useOUD = opioid use disorder; LARC = long-acting reversible contraception; SD = standard deviation; HS/GED == high school/general equivalencydiploma; MAT = medication-assisted treatment

80% of patients used methadone and 20% used buprenorphine. Most women were cared for by prenatal providers in our academic teaching service and on average, women attended 8 prenatal visits. Approximately 80% of women had documentation of prenatal contraceptive counseling by their provider. At hospital discharge, one third of patients did not have a documented contraceptive plan and among women with a plan, one third planned to use a short-acting method. Approximately 30% of patients attended a postpartum visit.

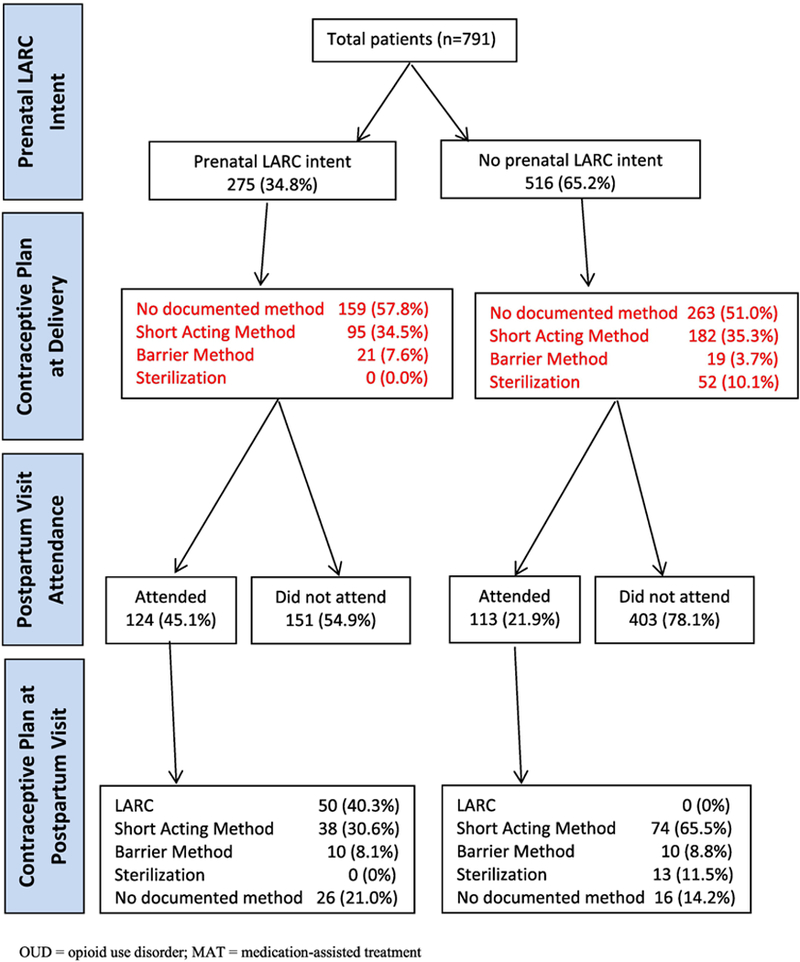

Figure 1 follows the contraceptive method choices of women with OUD during pregnancy, at delivery and during the postpartum visit. Among 791 pregnant women with OUD on MAT, 275 (34.8%) had documentation of prenatal LARC intent in the medical record. Because our institution did not provide immediate postpartum LARC services, the contraceptive plan was also evaluated at the time of delivery. At delivery, 159 (57.8%) women who intended to use a postpartum LARC did not have a contraceptive plan documented at the time of delivery (i.e. short acting or barrier method) and only 124 (45.1%) attended their postpartum visit by 8 weeks postpartum. Among women who planned to use postpartum LARC and attended their postpartum visit, only 50 (40.3%) received a LARC method with the remainder of women choosing to use a short-acting method, a barrier method or no method documented. Approximately 20% of women did not have any documentation of a contraceptive plan at the postpartum visit. In summary, among the 275 women who had a prenatal plan for LARC, only 50 (18%) received LARC by 8 weeks postpartum. Among women who did not intend to use a postpartum LARC, none received a LARC within 8 weeks postpartum.

Figure 1.

Table 1 lists the characteristics for all women in our study, stratified by prenatal LARC intent. Prenatal contraceptive counseling (96.7% vs. 70.7%; p<0.01), prenatal care provided by academic teaching service providers (43.6% vs. 19.2%; P<0.01), postpartum visit attendance (45.1% vs. 21.9%; p<0.01), no documented contraceptive plan (57.8% vs. 50.9%; p<0.01), gestational hypertensive disorder (10.9% vs. 4.5%; p<0.01) and methadone use (83.6% vs. 77.7%; p=0.05) were associated with prenatal LARC intent.

Table 2 lists the characteristics for women with OUD who attended their postpartum visit. Women with OUD who were married (22.0% vs. 10.3%; p=0.03) or had a plan for postpartum LARC without any interim contraception (66.0% vs. 20.9%; p<0.01) were more likely to receive a LARC method in the postpartum period. Women with Medicaid insurance (94.1% vs. 86.0%; P=0.05), who were primiparous (51.3% vs. 34.0%; p=0.03) or who had Hepatitis C virus (50.8% vs. 32.0%; p=0.02) were less likely receive postpartum LARC.

Table 2.

Characteristics of postpartum women with OUD on MAT who attended the postpartum visit, by LARC receipt, n=237.a

| LARC | No LARC | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| received | received | ||

| n=50 | n=187 | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age [years; mean (±SD)] | 27.8 (±4.9) | 27.2 (±4.8) | 0.43 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 48 (96.0) | 178 (96.2) | 0.94 |

| Other | 2 (4.0) | 7 (3.8) | |

| Married | 11 (22.0) | 19 (10.3) | 0.03 |

| Employed | 13 (26.0) | 40 (21.4) | 0.49 |

| Education | |||

| ≤HS/GED | 17(54.8) | 86 (59.7) | 0.53 |

| Some college/Associates degree | 10(32.3) | 48 (33.3) | |

| ≥Bachelor’s | 4 (12.9) | 10(6.9) | |

| Medicaid | 43 (86.0) | 176 (94.1) | 0.05 |

| Primiparous | 17(34.0) | 96 (51.3) | 0.03 |

| Healthcare Utilization | |||

| Prenatal visit attendance [# of visits; | 9.9 (±3.8) | 9.7 (±3.5) | 0.86 |

| mean (±SD)] | |||

| Prenatal contraceptive counseling | 164 (87.7) | 45 (90.0) | 0.66 |

| Prenatal care provider type | |||

| Academic Teaching Service | 32 (64.0) | 135 (72.2) | 0.26 |

| Private Practice | 18 (36.0) | 52 (27.8) | |

| Obstetric Outcomes | |||

| Route of delivery | |||

| Vaginal | 36 (72.0) | 119(63.6) | 0.27 |

| Cesarean Section | 14(28.0) | 68 (36.4) | |

| Preterm birth | 4(8.2) | 28 (14.9) | 0.22 |

| Medical & Psychosocial Co-morbidities | |||

| Maternal psychosocial risk factors | 26 (52.0) | 101 (54.0) | 0.80 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 37 (74.0) | 139 (74.3) | 0.96 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.30 |

| Gestational hypertensive disorder | 5 (10.0) | 12(6.5) | 0.39 |

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | 16(32.0) | 95 (50.8) | 0.02 |

| Substance Use History | |||

| Tobacco | 39 (78.0) | 155 (82.9) | 0.43 |

| Polysubstance useb | 23 (46.0) | 88 (47.1) | 0.89 |

| Opioid pharmacotherapy | |||

| Buprenorphine | 14(28.0) | 40 (21.4) | 0.32 |

| Methadone | 36 (72.0) | 147 (78.6) | |

| Contraceptive Plan at Delivery | |||

| Short-acting method | 10 (20.0) | 72 (38.5) | <0.01 |

| Barrier method | 7 (14.0) | 16(8.6) | |

| Female sterilization | 0(0) | 13 (6.9) | |

| No documented contraceptive plan | 33 (66.0) | 86 (45.9) | |

n (%) unless otherwise indicated;

history of cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana and/or benzodiazepine use OUD = opioid use disorder; LARC = long-acting reversible contraception; SD == standard deviation; HS/GEE = high school/general equivalency diploma; MAT = medication-assisted treatment

Table 3 shows the multivariable logistic regression models developed to predict prenatal LARC intent and postpartum LARC receipt. Prenatal contraceptive counseling (OR 6.67; 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.21, 13.89) and gestational hypertensive disorder (OR 1.97; 95% CI 1.0, 3.89) were associated with prenatal LARC intent. In contrast, older age (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.91, 0.98) and the receipt of prenatal care by private practice providers (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.32, 0.72) were negatively associated with prenatal LARC intent. Although parity was not predictive of LARC intent, women who were primiparous (CI 0.49; 95% CI 0.26, 0.97) were significantly less likely to receive a postpartum LARC in multivariable analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with prenatal LARC intent and postpartum LARC receipt by 8 weeks postpartum.a

| Prenatal LARC intent | Postpartum LARC | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | receipt | |

| OR (95% CI) | ||

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 0.95 (0.91, 0.98) | -- |

| Married | -- | 2.10 (0.89, 4.91) |

| Primiparous | -- | 0.49 (0.26,0.97) |

| Prenatal and Postpartum Healthcare | ||

| Prenatal visit attendance | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | -- |

| Prenatal contraceptive counseling | 6.67 (3.21, 13.89) | -- |

| Prenatal care provider type | ||

| Private Practice | 0.48 (0.32, 0.72) | |

| Medical & Psychosocial Co-morbidities | ||

| Maternal psychosocial risk factors | 1.36 (0.95, 1.95) | -- |

| Gestational Hypertensive Disorder | 1.97 (1.00, 3.89) | -- |

| Hepatitis C virus | 0.72 (0.51, 1.03) | 0.53 (0.27, 1.04) |

no women without a documented prenatal intent to obtain LARC had a LARC placed by 8 weeks postpartum LARC = long-acting reversible contraception; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

4. Conclusions

We found that prenatal contraceptive counseling was significantly associated with prenatal LARC intent, although postpartum LARC receipt among women with OUD in our cohort remained low. Pregnancy and the postpartum period are unique opportunities to provide comprehensive reproductive health services, particularly among women with OUD who are at high-risk for unintended pregnancy.[11] We also found that one-third of women with OUD in our cohort were interested in LARC, but only 18% actually received a LARC in the postpartum period. Consistent with our findings, an evaluation of non-pregnant women in OUD treatment programs also found discrepancies between LARC interest and utilization. Among 83 women with OUD at risk of unintended pregnancy, 27% expressed interest in using an implant and 41% expressed interest in using an IUD.[12] Likewise, previous research in non-OUD populations also demonstrate discrepancies between LARC intent and receipt as 40–75% of women who intend to get a postpartum IUD will not receive one. [13–15]

While multiple factors may contribute to differential rates of prenatal LARC intent and postpartum receipt, poor postpartum visit attendance likely plays a significant role. Only 30% of women in our cohort attended their postpartum visit which is considerably lower than the 50% postpartum visit attendance rate found among non-OUD Medicaid enrolled women. [7, 16] In previous research, postpartum visit attendance rates have been found to be significantly lower among low-income populations with limited resource availability (i.e. transportation) which may contribute to contraceptive disparities observed among underserved populations.[16] In an evaluation of predictors of postpartum follow-up among 197 women who intended to use a postpartum IUD, women who failed to follow-up were more likely to be Medicaid insured, lack transportation, have an unplanned pregnancy and be unemployed.[17] Similarly, women with OUD often face profound social and economic challenges in the postpartum period and our results emphasize the need to identify alternative approaches for the delivery of contraceptive services outside of the traditional postpartum visit.[5, 18]

Immediate postpartum LARC services have emerged as a way to circumvent contraceptive access barriers created by reliance on the postpartum visit.[19] Immediate postpartum LARC also eliminates cost barriers that can occur due to the loss of pregnancy- related Medicaid eligibility after delivery and ensures the provision of contraception prior to onset of sexual activity.[19] Approximately 40–57% of women report the resumption of sexual activity prior to the traditional 6-week postpartum visit which places them at increased risk of unintended pregnancy and short interpregnancy interval.[20] While one of the most significant barriers to the implementation of immediate postpartum LARC programs has been payer reimbursement, many Medicaid providers now offer reimbursement for provider insertion and device costs beyond bundled payment models.[21] As of April 2018, 38 state Medicaid programs provide reimbursement for immediate postpartum LARC.[22] Alternative, novel interventions such as incorporating LARC services into home visitation programs may also decrease LARC access barriers, especially in states where immediate postpartum LARC services are not yet reimbursed by payers. [23]

Prenatal LARC intent was also influenced by prenatal provider type as women cared for by academic teaching service providers were more likely to have a documented plan for a postpartum LARC. Discrepancies in rates of contraceptive counseling and LARC interest by provider type may indicate a need to intensify LARC education in private practice settings. Further, the prevalence of illicit drug use among women in these clinical settings may also be underestimated during pregnancy.[24] Lack of provider training, limited familiarity with current LARC options and the inappropriate use of overly restrictive criteria to identify LARC candidates have also been previously identified as provider-level barriers to LARC.[11, 19]

Our findings must be interpreted with certain limitations. Our dataset was derived from variables based on medical record documentation by clinical providers and may have inadequately captured the true prevalence of contraceptive counseling, contraceptive choice and method receipt. Likewise, we were unable to evaluate patients’ previous experiences with contraception and future pregnancy intent which significantly influence contraceptive preferences and method choice. Due to lack of linkages between our dataset and outpatient pharmacy records, we were unable to determine if patients filled prescription methods in the postpartum period. Likewise, we were unable to account for the use of over-the-counter methods such as condoms. We may have also incompletely captured the rate of postpartum follow-up and postpartum LARC placement for patients who presented to providers who do not share our medical record system. Finally, our dataset was quantitative in nature and we were unable to determine why patients may have changed their contraceptive preferences between delivery and the postpartum period as 60% of women with prenatal LARC intent and who attended their postpartum visit chose an alternative contraceptive option. Despite these limitations, the documentation of contraceptive plans in the medical record is critical for provider communication, especially in health systems where multiple providers care for patients across the perinatal period.

A significant discrepancy exists between the number of pregnant women with OUD on MAT who are interested in using a LARC method and the number of women who receive LARC in the postpartum period. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all women receive comprehensive counseling during pregnancy and that immediate postpartum LARC services should be available across all institutions.[19] Prenatal contraceptive plans should be readdressed in the immediate postpartum period and efforts should be made to match patients’ preferences with available services. Efforts to incorporate women- centered services into OUD treatment programs, including the provision of contraception, will also fill gaps in postpartum healthcare for this population. If resources are limited in OUD treatment settings, prenatal and postpartum contraceptive counseling by OUD treatment providers and improved postpartum care coordination with obstetric and primary care providers who provide contraceptive services may also improve postpartum contraceptive use among women with OUD.[25] Further evaluations are also warranted to examine contraceptive counseling approaches, patient preferences and additional barriers to contraceptive use relevant for women with OUD.

Implications: Despite prenatal interest in using LARC, most pregnant women with OUD on MAT did not receive postpartum LARC. The provision of immediate postpartum LARC services may reduce barriers to postpartum LARC receipt such as poor attendance at the postpartum visit.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under Award Number K23DA038789 (Dr. Krans). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, et al. Unintended pregnancy in opioid-abusing women. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011;40:199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Black KI, Stephens C, Haber PS, Lintzeris N. Unplanned pregnancy and contraceptive use in women attending drug treatment services. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;52:146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Terplan M, Hand DJ, Hutchinson M, Salisbury-Afshar E, Heil SH. Contraceptive use and method choice among women with opioid and other substance use disorders: A systematic review. Prev Med 2015;80:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Krans EE, Cochran G, Bogen DL. Caring for Opioid-dependent Pregnant Women: Prenatal and Postpartum Care Considerations. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015;58:370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Krans EE, Kim JY, James AE, 3rd, Kelley DK, Jarlenski M. Postpartum contraceptive use and interpregnancy interval among women with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depen 2018;185:207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thiel de Bocanegra H, Braughton M, Bradsberry M, Howell M, Logan J, Schwarz EB. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care and contraception in California’s Medicaid program. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:47 e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Krans EE, Zickmund SL, Rustgi VK, Park SY, Dunn SL, Schwarz EB. Screening and evaluation of hepatitis C virus infection in pregnant women on opioid maintenance therapy: A retrospective cohort study. Subst Abus 2016;37:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Krans EE, Bogen D, Richardson G, Park SY, Dunn SL, Day N. Factors associated with buprenorphine versus methadone use in pregnancy. Subst Abus 2016;37:550–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [11].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 186: Long- Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine Devices. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e251–e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Matusiewicz AK, Melbostad HS, Heil SH. Knowledge of and concerns about long-acting reversible contraception among women in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. Contraception 2017;96:365–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ogburn JA, Espey E, Stonehocker J. Barriers to intrauterine device insertion in postpartum women. Contraception 2005;72:426–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Engin-Ustun Y, Ustun Y, Cetin F, Meydanli MM, Kafkasli A, Sezgin B. Effect of postpartum counseling on postpartum contraceptive use. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275:429–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, Hohmann HL, Perriera LK, Creinin MD. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1079–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Optimizing postpartum care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Baldwin MK, Hart KD, Rodriquez MI. Predictors for follow-up among postpartum patients enrolled in a clinical trial. Contraception. 2018;May 8 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Krans EE, Tong ST, Terplan M. (2018). Postpartum care for women with substance use disorders In Wright TE (Ed.), Opioid Use Disorders in Pregnancy: Management Guidelines for Improving Outcomes (pp. 113–126). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [19].American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 670: Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:e32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Connolly A, Thorp J, Pahel L. Effects of pregnancy and childbirth on postpartum sexual function: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hofler LG, Cordes S, Cwiak CA, Goedken P, Jamieson DJ, Kottke M. Implementing Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Programs. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Medicaid Reimbursement for Postpartum LARC by State. Accessed at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Long-Acting-Reversible-Contraception/Immediate-Postpartum-LARC-Medicaid-Reimbursement on June 29th, 2018.

- [23].Uhm S, Pope R, Schmidt A, Bazella C, Perriera L. Home or office etonogestrel implant insertion after pregnancy: a randomized trial. Contraception. 2016. Nov;94(5):567–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schauberger CW, Newbury EJ, Colburn JM, Al-Hamadani M. Prevalence of illicit drug use in pregnant women in a Wisconsin private practice setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Krans EE, Bobby S, England M, Gedekoh RH, Chang JC, Maguire B, Genday P, English DH. The Pregnancy Recovery Center: a women-centered treatment program for pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use. Addict Behav 2018. May 24 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]