Abstract

Background:

Case-control studies remain an important study design for aetiologic research on cancer, particularly when cohorts are not available. In addition to the potential biases inherent in this design, conducting fieldwork in settings with weak health care and information systems for cancer, such as in sub Saharan Africa, confer additional challenges which we present here with the aim to share experience to guide future studies.

Methods:

We undertook a hospital-based case-control study of squamous cell esophageal cancer at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret, West Kenya. Cases were recruited at endoscopy and controls from hospital wards, age and gender frequency-matched to cases. Urine, toenails, blood and tumour biopsy were collected and a questionnaire administered.

Results:

During this pilot phase, 143 cases and 155 controls were successfully recruited. Complete questionnaire data was obtained through e-data collection. Biospecimen collection was possible with support of an already existing equipped laboratory. We introduce changes made in the main study phase, including on expansion of the control groups to allow to consideration of selection bias.

Conclusions:

Extra attention and funding to train and monitor data quality and biospecimen collection and reimbursement of a large group held together by strong leadership are essential. We recommend studies based on regional treatment centres with their more defined catchment areas rather than in the capital cities as referral routes in multi-level health care systems are severely attrition prone.

Keywords: case-control study, esophageal cancer, LMICs, fieldwork

1. Introduction

Case-control studies form an important study design in cancer where mature cohorts with sufficient outcomes are not available. Where this applies in low and middle income (LMIC) settings, fieldwork conduct requires specific design, management and financial considerations for their successful implementation. With a view to aid in future planning of similar endeavours, we present a recent experience of implementing an esophageal cancer case-control study in Kenya.

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the third most common cancer in both genders in East Africa1. Its high incidence occurs in a north-south easterly lying corridor from Ethiopia to South Africa, known as the African EC corridor2. In Kenya, age-standardized incidence rates of EC in 2012 were nearly four-fold higher than global rates, with 3,400 newly diagnosed EC patients1, including affecting young patients rarely seen in other high-incidence areas3. The histological subtype esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) predominates4–6. Since the establishment of the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in 1990 in Eldoret, in the west of Kenya, EC has consistently been one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers5. In 2013 we commenced an ESCC case-control study at this hospital, which aimed to investigate a broad range of risk factors. Herein we describe the real-life experience, challenges and resulting changes to fieldwork implementation, to aid cancer researchers and funders for the planning and smooth-running of similar studies.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Setting and study design

The study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of Moi University (000921) and by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Ethics Committee (IEC 14–15). A casecontrol study of ESCC was conducted at MTRH, a tertiary government hospital situated in Eldoret town, Uasin Gishu county in western Kenya (Figure 1). MTRH serves the former Nyanza, Western and Rift Valley provinces and also receives patients from Uganda and South Sudan. Its outpatient department has an endoscopy unit where the first internal investigations of suspected EC are made. At the time of study conduct, MTRH was the only tertiary public referral hospital in the region that offered endoscopy, and only very recently was the service available in Kisumu. In Figure 1, the residential address density decreases more rapidly south of MTRH, because patients would increasingly choose to go to Tenwek Mission Hospital (200km south of MTRH) where specialist esophageal stenting is offered. This was the first site in ESCCAPE, the ESCC African Prevention Research studies (esccape.iarc.fr), which is now recruiting in three East African countries; together they form part of the African EC consortium7.

Figure 1.

The spatial distribution of geocoded residential locations of cases and controls, ESCCAPE Kenya esophageal cancer case-control study.

2.2. Case and control recruitment

On Monday through Friday from August 2013 to September 2014, all adults aged 18 years and over presenting at the MTRH endoscopy unit with a history of progressive dysphagia or clinical features suggestive of an esophageal tumour, but with no history of EC, were invited to participate as cases. The study objectives were explained in Swahili or other local languages and informed signed consent was obtained with a signature or thumbprint. Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy was conducted without sedation or the use of Lugol’s iodine. During this procedure, two sets of tumour biopsies were collected: one preserved in RNAlater TissueProtect tubes (Qiagen, Germany) and one in 10% neutral buffered formalin for processing into a paraffin block (FFPE) for histological confirmation on a hematoxylin and eosin slide (Figure 2). If cases declined study participation, endoscopy was conducted as usual. For consenting cases, a detailed questionnaire was administered face-to-face in a private room after endoscopy. Study participants received no payment for their participation, but cases’ histology fee was covered by the study. We offered milk and yoghurt to cases during the interview, for their comfort as they had been fasting for the endoscopy procedure. A recruitment log was maintained of all potential cases. The patient encounter ended after the interview and sample collection had been carried out. For most EC patients at MTRH, treatment is palliative.

Figure 2.

Examples of H&E-stained esophageal biopsies from patients in the study: (a) Low magnification (2×) of an entire biopsy, representative of a biopsy with a reasonable size for diagnosis; (b) The same biopsy with higher magnification (20×), revealing a well-differential SCC. Keratin pearls, as indicative of differentiation, are easily recognizable; (c) Moderately differentiated SCC, showing only single-cell keratinization (10×); (d) Poorly-differentiated SCC with no keratinization (10×) slides from esophageal cancer patients showing the different degrees of differentiation (Source: Dr Behnoush Abedi-Ardekani, Pathologist, IARC)

Hospital controls were recruited from hospital patients with no history of EC and were not currently admitted for a digestive disease or cancer. Controls were recruited from general surgery, orthopaedic surgery and ophthalmology wards. A 1:1 case:control ratio was planned, with controls frequency-matched on age and gender to the expected distribution of EC cases obtained from the Eldoret Cancer Registry. Study research assistants monitored these distributions and thus directed their efforts to approach potential controls of a certain age and gender.

2.3. Exposure data

To examine a broad range of lifestyle, environmental and genetic factors, the following questionnaire data was collected, paying particular attention to ascertain exposures in terms of their local sources and exposures routes. To do this, questionnaires were developed jointly by the local PI, a social anthropologist with specific knowledge of the ethnic groups in this region, and the international team. Lifestyle factors included alcohol consumption, miraa (khat), smoked and smokeless tobacco use, hot beverage and hot porridge consumption, and oral hygiene habits. In addition to common commercial types, these factors were assessed in terms of the local alcohols busaa and chang’aa, smoking of handrolled tobacco, chewing tobacco, consumption of mursik (charcoal-laden fermented milk), and using charcoal (makaa) or a stick (mswaki) to clean teeth. Environmental factors of interest were food contaminants, pesticide exposure, household air pollution and drinking water, thus we obtained information on mouldy maize, maize storage practices, predominant drinking water supply and cooking in the home (fuel type, ventilation in cooking area, hours spent at a fire per day). Recall-based assessment of nutritional deficiencies are error-prone, thus instead we obtained detailed information of a participant’s place of residence and in a side-study with the British Geological Survey (UK), surveys of soil, water and staple crops are being conducted across the study region to which we can approximate small area-level deficiencies. For genetic factors, in addition to family history of the disease, blood samples were collected to later extract DNA for germline mutations (see biopsecimen). Finally, information on sociodemographic characteristics including age, ethnicity, education and amenities were also ascertained.

Data were collected using 7’’ low cost tablets with an Android 4.1.2 operating system. Open Data Kit (ODK) was used locally to program the questionnaire with inbuilt logical skips and range checks. Data were downloaded weekly from the tablet and imported into a backed-up Microsoft Access database. Participant confidentiality was maintained with the use of password-protected tablets and encrypted databases.

2.4. Biospecimen collection

Blood, urine and toenail samples were collected for all participants, and the tumour biopsy for cases as described previously. A four (4) mL blood sample was collected in EDTA tubes and 8 mL without anticoagulant. The EDTA samples were used for blood grouping and the rest was separated into plasma, buffy coat and red blood cells. Plain blood was separated into two 2 mL serum and clot. All samples were stored in −80°C freezers with back up samples. A 25 mL urine sample was aliquoted into four 5 mL vials and stored at −80°C for future analysis of biomarkers of carcinogen exposures (e.g. 1-hydroxypyrene glucuronide (1-OHPG), a polycyclic-aromatic hydrocarbon metabolite associated with ESCC in some studies8. Toenail clippings – useful longer-term biomonitoring matrices9 - were taken from both large toes by research assistants and stored at room temperature. Biospecimen processing and storage took place at the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) research laboratories. Permission was obtained from the Ministry of Health for international shipment of biospecimens.

2.5. Training and standardization

The study manual contained detailed protocols for all aspects of the study, including study proforma and SOPs of biospecimen handling. The two research assistants were trained in interview technique to ensure impartiality and consistency, especially as blinding to case-control status was not possible. Post training, periodic observations of the interview process were made by the site and international PIs.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment of cases and controls

During this 12-month pilot phase, 329 participants were enrolled: 173 as suspected cases (96% participation) and 156 (92%) of approached controls. Of these 173 suspected cases, 30 were excluded due to no questionnaire data (n=13), and 17 because the histology ruled out ESCC (14 adenocarcinoma, 1 Kaposi sarcoma and 1 papilloma), giving a total of 143 cases, 85% of whom had a histologically confirmed ESCC diagnosis and the remaining had an endoscopy-visualized tumour. The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the cases was 58 (SD 12) years and that of controls was 57 years (SD 16). Notably 9 cases (5.6%) were under age 40 at diagnosis, which is a lower proportion than some other African settings have reported4. The age balance between cases and controls was broadly achieved, but with respect to the gender distribution, two-thirds (65%) of the cases were men, whereas 54% of the controls were men. In over half of cases the tumour was in the middle third of the esophagus. The majority (58%) were reported to have poorly differentiated ESCC. Welldifferentiated ESCC constituted 28%, moderately differentiated constituted only 6% while 12% were indeterminate. Using the GeoNames geographical database, addresses of participants are shown in Figure 1. Two-thirds of participants resided in immediate county, Uasin Gishu, or its neighbouring counties. There was no difference in distance to hospital (median: 54 km; interquartile range (IQR) 32–85) and controls (47 km; IQR range: 22–87). Cases and controls also did not differ by ethnicity, but cases tended to have lower education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 143 included cases and 155 controls during the first year of recruitment

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18 to <40 | 7 (5) | 25 (16) | 0.02 |

| 40 to <50 | 27 (19) | 26 (17) | |

| 50 to <60 | 44 (31) | 37 (24) | |

| 60 to <70 | 34 (24) | 33 (21) | |

| 70 to <80 | 23 (16) | 18 (12) | |

| 80+ | 8 (6) | 16 (10) | |

| Mean (SD) | 58 (12) | 57 (16) | 0.20 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 94 (65.7) | 84 (54.2) | 0.04 |

| Female | 49 (34.3) | 71 (45.8) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 121 (85) | 106 (68) | |

| Single | 2 (2) | 8 (5) | |

| Widowed | 12 (8) | 30 (19) | 0.01 |

| Divorced/Separated | 7 (5) | 11 (7) | |

| Religion | |||

| Catholic | 88 (62) | 84 (54) | |

| Protestant | 49 (34) | 63 (41) | 0.44 |

| Other | 4 (6) | 8 (5) | |

| Level of education | |||

| None | 36 (25) | 40 (26) | |

| Primary | 81 (57) | 61 (39) | 0.002 |

| Secondary or higher | 26 (18) | 54 (35) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Farming | 98 (69) | 81 (52) | 0.004 |

| Other | 45 (31) | 74 (48) | |

| Province of usual residence | |||

| Rift Valley | 99 (65.9) | 118 (76) | |

| Western | 33 (19.7) | 21 (14) | 0.09 |

| Other | 11 (6.8) | 16 (10) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Kalenjin | 83 (58) | 82 (53) | |

| Luhya | 37 (26) | 32 (21) | |

| Luo | 12 (8) | 16 (10) | |

| Kikuyu | 4 (3) | 8 (5) | 0.20 |

| Other | 7 (5) | 13 (8) | |

p-values were calculated using a T-test when making comparisons between means of continuous variables, a chisquared test for when comparing distributions of categorical variables and Fisher’s exact test when cell counts were less than 5.

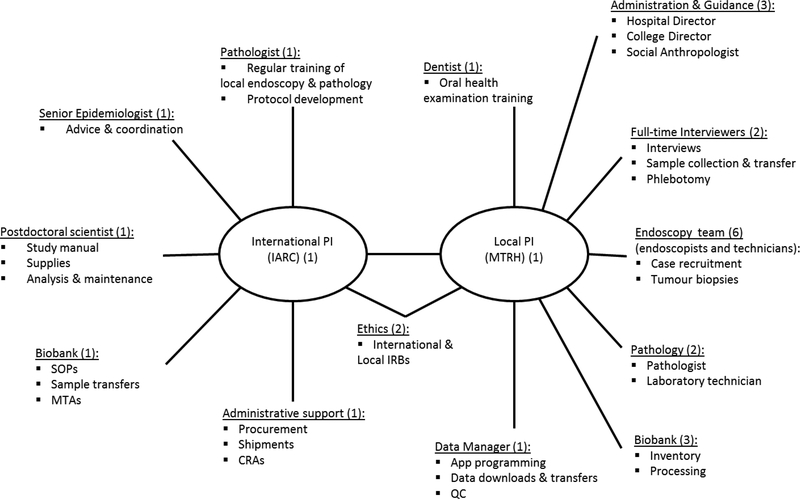

3.2. Coordination, teamwork and communication

Central to its successful implementation was cooperation of a large multidisciplinary team, which exceeded 20 people involved either locally or internationally. The team and its roles are shown in the organogram (Figure 3). A highly motivated and respected site PI played a central role to local coordination. Her professional network brought together the large multidisciplinary team, each member of which had to be individually approached. Key recruitments by the site PI were the two experienced research assistants. Their qualifications, to BSc or higher and with knowledge of health research and the medical environment, facilitated their communications with the endoscopy team, liaisons across hospital wards for control recruitment as well as their interactions with participants. One research assistant was qualified in phlebotomy, and the other had experience in biospecimen processing, thus they worked closely together to manage all elements of the protocol. The study was also supported by (i) endoscopists and endoscopy nurses, to recruit cases and obtain tumour biopsies; (ii) the AMPATH biobank, for biospecimen receipt and processing; and (iii) pathologists and laboratory technicians to prepared FFPE tumour blocks. In the organogram, we also included the study dentist who joined the study team only after the pilot phase, for training the research assistants in oral health examinations that were later added. Key institutional support both at MTRH and Moi University also facilitated contractual arrangements. Internationally, the study was supported by IARC, including pathologists, epidemiologists and postdoctoral fellows.

Figure 3:

Organogram of the local and international multidisciplinary team involved in the esophageal cancer case-control study fieldwork, indicating team members and their roles.

Communication across this wide team was established on a frequency that reflected each member’s involvement. On a weekly basis, the site PI met the core local team in person, i.e. the two research assistants and data manager, to monitor progress and discuss and resolve any issues arising. On a monthly basis, the site PI and international PI communicated via email or phone, who was the central point of contact outside of Kenya, and liaised as needed with the IARC-based team.This full team met in person in Eldoret on an annual basis, where the broader study overview of how the different components fit together was presented.

3.3. Interactions with participants

The interview lasted a little over one hour, which is long for weak patients, but was relieved by the food and drink provided. Although not pre-planned, the two interviewers came from different dominant ethics groups and were of different genders, covering language or other preferences of patients where needed, suggesting in future studies this aspect should be considered in the planning. Research assistants were concerned that therapeutic misconception may have influenced the decision of some cases to participate, i.e. patients may agree to participate with the misconception that they would receive free or better therapy in doing so, thus the consent process needed to be detailed and long, up to 10 minutes of explanation. Some participants declined to have blood samples drawn after the conclusion of the interview. As most cancer patients present at very advanced stages, some EC patients were too weak, dehydrated and with collapsed veins therefore limiting blood drawing and if blood drawing was successful, blood samples quickly haemolysed. During the interview process, obtaining information on habitual amounts of consumption was problematic, with the concept of ‘average’ consumption on an average day challenging to some participants, thus some questions were later changed to ascertain the total consumption over a week/weekend.

Use of a tablet for e-data collection was time-efficient and was accepted by participants. However, data stored were once lost due to the tablet being crushed in a motorcycle accident, as the back-up is conducted weekly, not in real-time. In addition, the programmed questionnaire is designed to be completed in one sitting, which was occasionally not possible if patients tired, so another patient’s interview might have to be done on paper and later be entered onto the tablet. Three such paper questionnaires did not reach the e-database.

3.4. Biospecimen collection and endoscopy

The endoscopy and tumour biopsy specimen collection protocols followed were not without extra expense. Buffered formalin was not used routinely in the hospital, thus salts were purchased, delivered and especially prepared. Endoscopy equipment was not optimal: forceps were replaced to improve biopsy cuts; the unit had to use a paediatric or colonoscope due to the prohibitive costs of new endoscopes which unfortunately could not be covered by the limited study funds. Additionally, endoscopies in MTRH are carried out without Lugol’s iodine which limits the visualization of abnormal esophageal mucosa. Of greater concern is that patients are not sedated during the procedure. Instead a local anaesthetic (2% Xylocaine) is sprayed, which temporarily numbs the throat area to allow for easy passage of the endoscope. Lack of sedation leads to patients struggling due to their discomfort and this movement limits visualization of tumour and leads to inadequate sample collection as the endoscopist tends to rush through the procedure in order to end the patient’s distress. Many biopsy pinches were prohibitively small for adequate histological review, yet outside of this study, there were few times when the endoscopy and histopathology teams met to exchange feedback to improve this process.

Bio-banking was well supported by the AMPATH laboratories. Specimens were identified and box maps were well-maintained, however during this pilot phase, the laboratory did not yet have an electronic laboratory information management system so handwritten labels had to be deciphered for later data entry.

3.5. Budgetary considerations

Study expenses included, as in all settings, salaries or salary contributions for research assistants, data manager and PI and study-specific supplies, airtime and equipment costs. Additionally, every single person with a role in the study, as listed in the organogram, was compensated for their time as contributions to research studies are often used as means to supplement salaries for public health care professionals. Other items provided, that might be assumed to already exist in other settings, included salts to prepare buffered formalin and new forceps to improve biopsy quality in endoscopy. For biospecimen, the study paid MTRH for each patient’s 1,000 Kenyan shillings histology fee. It also paid a private pathology laboratory for a study FFPE block preparation, and the biobank for all processing and storage. The latter fees increased substantially during the study period, as separation of blood into separate vials (plasma, buffy, red blood cells, serum), escalated the storage costs under a per vial pricing plan. Study costs also included travel and dry-ice biospecimen shipments.

4. Discussion

We report on fieldwork experience in the pilot phase of an esophageal squamous cell carcinoma casecontrol study in Western Kenya. The study proceeded to the main study which has now recruited over 400 cases and 400 controls (cumulative) and its first results are emerging10. The pilot study called for protocol changes and considerations specific to this setting, which are discussed below and from which we make recommendations for fieldwork (R1-R9) in Box 1.

Box 1: Recommendations for cancer case-control study fieldwork in resource limited settings.

R1. Choice of hospital(s) for case recruitment is crucial and requires good knowledge of health infrastructure, catchment area, and referral patterns. Potential selection bias can be reduced via recruitment from noncapital city centers, as referral patterns are complex and highly depend on individuals’ resources.

R2. Geocoding of usual residential address of cases and controls provides a useful partial check of overlapping source populations.

R3. Including different types of controls – community, hospital visitor and hospital patients – can help to gauge the extent of contra-directional biases.

R4. Study teams involved for cancer studies including biospecimens are very large, needing leadership, coordination and compensation.

R5. The willingness of cases needs to be protected by a thorough conformed consent procedure.

R6. mHealth and eHealth data collection transformed fieldwork conduct and efficiency.

R7. Biospecimen handling training and retraining is vital. Such upfront investment is a longer-term saving.

R8. Detailed knowledge and good planning of all practicalities is essential, with good backup plans.

R9. Diverse teams bring different perspectives. Face-to-face meetings translate into improved study design.

R10. Funding for the time, travel, equipment, treatment, infrastructure and capacity building should be amply supported.

4.1. Design considerations

Overall, the study proceeded successfully. High participation rates were seen once the study subjects were identified and, perhaps due to curiosity and long uneventful waiting times in hospital, there was high motivation and responsiveness during interviews, in comparison to vast experiences IARC has had in running case-control studies in high resource settings. This was reflected in low proportions of missing data and internal and external plausibility of reported data, for instance good correspondence between the control group and population surveys on some lifestyle factors.19 Concerning challenges, defining the source population is difficult in a setting where there are multiple barriers to being diagnosed with cancer11,12. Whilst ‘population-based’ controls are often advocated for, some sectors of the community have very low chances of reaching a tertiary or any hospital if they had had cancer. Understanding referral patterns are crucial to ensure cases and controls are from the same source population (R1). In our study, geocoding of participants’ residential addresses enabled us to verify that cases and controls were appropriately overlapping with respect to usual residence (R2). Through the use of hospital controls, who also overcame the same barriers to reach the hospital, sociodemographic profiles were also overlapping. Additionally, the study was set in a regional referral hospital so the same catchment area was broadly applicable to all diseases (R1). In a previous experience of a case-control study in a capital city setting, where, although controls were age-sex and residence matched to cases, marked differences were present in the education and religion of cases and controls, introducing strong correlations with lifestyle factors, making it difficult to disentangle risk and bias13. Such large differences appear to have been avoided in the present study through the use of a non-capital city setting, however in doing so, it is possible that we are missing young patients if extra attention is given to them to bring young patients to the most specialized centres. Nonetheless, in our study, the residential overlap between cases and controls does not ensure the same source population with regards to other attributes. Hospital patients are ill; they are in hospital for a reason, thus there remains for potential bias to attenuate effect estimates to an unknown extent. Selection bias in the opposite direction would arise from a healthier-than-average control group, as it expected from the population of hospital visitors, thus in the main study we additionally including hospital visitors as controls (R3).

4.2. Study conduct and coordination

Team:

Key to the study’s success was formation of a large multidisciplinary team. Creating harmonious working relations was an arduous undertaking which required ongoing troubleshooting, but ultimately succeeded with excellent leadership, regular communication, remuneration, goodwill and cooperation. The importance of these relationships cannot be oversold when undertaking such a study (R4)

Capacity building:

The successful international and north-south collaborations also benefitted from wider professional experience and training opportunities. Such capacity building is an investment in longer-term research continuity and relationships, and, for the present study, increases motivation. Five of the Kenyan team members attended the IARC summer school in cancer epidemiology, one IARC-UICC development fellowship was awarded to the site’s data analyst, who was able to spend 3 months at IARC analysing the study data, gaining analytical, writing and statistical skills. Biobanking locally was linked to IARC’s biobanking in LMICs network and its training opportunities. Finally, using the study data and mentorship from the PIs, one PhD has been successfully completed, and a second one is planned.

Participant contact:

Contact with participants, particularly patients, needs to be carefully considered in this setting (R5). During the informed consent process, research assistants were aware of the potential of therapeutic misconception and the importance of not giving false hope to patients. Additionally, with only a histology fee covered, we avoided inappropriate inducement to study participation. However, we were not able to provide additional support to patients, due to budgetary limitations. Ideally, the research study could have introduced sedation for endoscopy, which will require a recovery room and additionally nursing staff as the current health system is overstretched. We would also have liked to improve therapeutic and palliative care options for patients, regardless of study involvement. Whilst the study was able to purchase equipment items up to approximately $1000 each, more expensive equipment items needed for patient care, and that would have also improved biospecimens quality, such as scopes, could not afforded but would ideally be included in budgets for longer term study planning.

Data capture:

In the present experience, the challenging tasks of managing data entry completeness were overcome through the use of e-Health, and m-Health data collection would have achieved the same. We consider this a major transformation to data collection and study coordination (R6). These data collection methods are time-efficient and allow truly multi-institutional international collaborative fieldwork. Through access to real-time data, fieldwork progress is monitored; data issues can be identified and corrected early, ultimately leading to higher quality data and more rapid generation of results. Nevertheless, availability of data in real-time is only of use if such QC is then implemented. In this pilot phase, more male the female cases presented than had been originally expected, a trend which should have been corrected in the control recruitment. In addition, a drawback to immediate e-data entry was lack of a paper (or other) record to go back to in the instance of the lost or deleted or if values need checking. Obtaining permissions and a cell phone number to call a participant back at a later stage was helpful for these checks.

Biospecimen:

Biospecimen collections need continual on-site training of all involved personnel, both at the start of fieldwork and periodically throughout it. Scientists in whose primary interests it is to obtain optimum biospecimens may consider this early investment as a longer-term saving, because the downstream costs of shipments and sample analyses are not wasted if they are performed on adequate specimen (R7). Small but critical technique adjustments can be pivotal here, e.g. orientation of tumour biopsies, freezer storage timing, retention of the entire buffy coat. Although ESCC is not a complicated histology at microscopic examination, a confident diagnosis is greatly aided by high-quality slides, which result from care taken throughout the process of biopsy taking to tissue processing. Setting up a standardized and specimen-adapted tissue processing procedure (manual or automated based on the facilities) is the basis of a successful microscopy. Continued and regular feedback between pathologists, laboratory technicians and the endoscopy team needs to be considered. Supervision of regular and ontime changes of reagents is important. It is also important and reassuring for local pathologists, especially recently graduated pathologists, to set up a possibility of consultation and second opinion facility to consult “difficult” cases. To achieve such good quality specimen and workflow, studies need to incorporate a budget for equipment that is often considered as standard in other settings. Such expenditure benefits not only the research, but with immediate clinical benefits it also serves to maintain good relationships and research continuity. An ethical argument also exists not to take biospecimens of poor quality in the first place.

Risks:

Fragile health systems pose risks to study conduct. In this pilot phase, the study was fortunate not to experience strike action, but it did affect the study at later dates. At the end of 2016, a 100-day strike by doctors in Kenyan public hospitals meant that recruitment was suspended during this period, however by this time two other sites outside of Kenya had commenced recruitment, so the overall study was not jeopardized. Contingency planning for various eventualities, staff absences, lack of supplies, need to be considered (R8).

Communication:

Lastly, whilst modern technologies greatly facilitate research connections between international groups, for both dry data and biospecimens collections face-to-face meetings can still never be dispensed of. Study quality is improved through personally viewing the entire process, and making adjustments where necessary (R9). During such visits, an outside perspective also led to questionnaire modification. Exposures considered very usual in the local setting were not on the radar as suspected carcinogens, but were noticed as being exceptional only once viewed by non-locals. Such fieldwork needs a dirty hands-clean mind approach, to understand the exposures experienced by the actual populations in which the cancer being studied arises.

Funding:

Throughout all of the above issues, an investment of funds in needed – for time, travel, supplies, training (R10). Adequate funding from a study’s initiation improves scientific output sooner and because an efficient investment. A good quality study grows exponentially in its scientific potential, insights that often go well beyond the initial study’s scope. This experience was had in our study – the feasibility demonstrated in the 2013–14 pilot study led in 2015 to the US National Institute of Health R21 funding for its 2-year continuation. More recently, the study has led to a unique opportunity for African cancer genomics. The EC tumour specimens are now being sequenced at the Sangar Institute, Cambridge, as part of the landmark Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge The Mutographs of Cancer project.

5. Conclusions

This pilot case-control study on ESCC in Kenya provides a valuable experience of the conduct of cancer epidemiological studies in a lower resource setting. Critical points that we felt strengthened the present experience were collaboration, strong leadership, remuneration and cooperation of a large team, and investment into capacity building. Attention to the informed consent process and choice of source and study populations were critical, whilst e-data collection was efficient. Throughout, funding was needed for travel, supplies, equipment, and training for the long-term investment into high quality biospecimen collections. The experience encourages us and hopefully others to continue such work and the added knowledge on causes of cancers will be instrumental if we are to succeed in the global combat against cancer.

Highlights.

Strong leadership brought together a team of 20+ members for successful study implementation

Training and regular face-to-face QC of biospecimen collections are invaluable investments

Recruitment at a regional, rather than capital city, hospital helped reduce selection bias

Time and funds to support all aspects of fieldwork are essential

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to that all participants and the family members who took part in the study.

Funding: This work was supported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and NIH/NCI (grant number R21CA191965).

Abbreviations used:

- AMPATH

Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare

- EC

esophageal cancer

- EGD

esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- LMIC

low-middle income country

- MTRH

Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Declarations of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography and References Cited

- 1.Ferlay J et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J. Cancer 136, E359–E386 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack VA et al. Informing etiologic research priorities for squamous cell esophageal cancer in Africa: A review of setting-specific exposures to known and putative risk factors. International Journal of Cancer (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawsey SP et al. Esophageal cancer in young people: a case series of 109 cases and review of the literature. PLoS. One 5, e14080 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawsey SP et al. Esophageal cancer in young people: a case series of 109 cases and review of the literature. PLoS One 5, e14080 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakhisi J, Patel K, Buziba N & Rotich J Esophageal cancer in north rift valley of Western Kenya. African health sciences 5, 157–163 (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White RE, Abnet CC, Mungatana CK & Dawsey SM Oesophageal cancer: a common malignancy in young people of Bomet District, Kenya. Lancet 360, 462–463, doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09639-3 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Loon K et al. The African Esophageal Cancer Consortium: A Call to Action. Journal of Global Oncology 4, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abedi-Ardekani B et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure in oesophageal tissue and risk of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in north-eastern Iran. Gut 59, 1178–1183 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middleton DR et al. Prolonged exposure to arsenic in UK private water supplies: Toenail, hair and drinking water concentrations. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 18, 562–574 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menya D et al. Traditional and commercial alcohols and esophageal cancer risk in Kenya. Int J. Cancer in press (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wacholder S, Silverman DT, McLaughlin JK & Mandel JS Selection of controls in case-control studies: II. Types of controls. American journal of epidemiology 135, 1029–1041 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman KJ, Greenland S & Lash TL Case–control studies. (Wiley Online Library, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leon ME et al. Qat use and esophageal cancer in Ethiopia: A pilot case-control study. PLoS One 12, e0178911, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178911 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]