Abstract

Both spin-echo (SE) and ultra-short echo (UTE) based MRI sequences were used on a 7T μMRI system to quantify T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times from articular cartilage to the cartilage-bone interface on canine humeral specimens at 19.5μm pixel resolution. A series of five relaxation-weighted images were acquired to calculate one relaxation map (T2, T1ρ or T1), from which the depth-dependent profiles were examined between the SE method and the UTE method, over the entire non-calcified cartilage and within the cartilage-bone interface. SE-based methods enabled the quantification of relaxation profiles over the noncalcified cartilage, from 0μm (articular surface) to approximately 460μm in depth (near the end of radial zone). Most of the cartilage-bone interface was imaged by the UTE-based methods, to a tissue depth of about 810μm. Pixel-by-pixel calculation of the relaxation times between the independent SE and UTE methods correlated well with each other. A better understanding of the tissue properties reliably over the cartilage-bone interface region by a non-invasive MRI approach could contribute to the clinical diagnostics of trauma-induced osteoarthritis.

Keywords: UTE, T2, T1ρ, T1 quantitative MRI, articular cartilage, zone of calcified cartilage, microscopic resolution

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Articular cartilage is a highly ordered connective tissue and has a unique morphological structure. Based on its local fibril orientation, articular cartilage is commonly sub-divided across its thin thickness (depth) into three histological zones: the superficial zone (SZ), the transitional zone (TZ), and the radial zone (RZ). The collagen fibrils in each of the sub-tissue zones have a preferred orientation [1, 2]. Below RZ, there is an interdigitated cartilage-bone interface region, which contains the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC) that attaches the noncalcified articular cartilage to the subchondral bone [3, 4]. In healthy adults, ZCC behaves largely as a structural tissue in which the blood vessels terminate. A traumatic event can damage ZCC [5-7] and, hence, disrupts the physiological and biomechanical functions of the interface, which would inevitably lead to the disintegration of a synovial joint as a living organ. In addition, it has been speculated that ZCC could be reactivated in osteoarthritis (OA) and play a role in the thinning of cartilage during the development of OA [8]. It is, therefore, critically important to study the cartilage-bone interface.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been widely used in the diagnosis of OA because of its excellent contrast for soft tissues and its non-invasive nature in imaging [9]. Among an extensive set of parameters that could be used in MRI of cartilage, the quantification of T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times is currently the most used protocols in clinical MRI of cartilage and joint [10-17]. Together with the use of some advanced analysis procedures, such as texture analysis [18], diagnostics of OA at its early stages has been increasingly possible [19, 20]. One limiting factor in clinical MRI of human cartilage and joint is its imaging resolution, typically with a 300-500μm transverse pixel resolution in a 3 Tesla whole-body system. This pixel resolution is insufficient for the determination of the zonal characteristics of articular cartilage as well as for the detections of small defects in the early stages of joint degeneration. With similar principles in physics and identical architecture in engineering, microscopic MRI (μMRI) can reach a transverse pixel resolution on the order of 10s of microns when it is used to study small animals and ex vivo tissue blocks [21, 22]. μMRI, hence, provides an effective translational pathway between the invasive and destructive procedures in optical/electronic microscopies and non-invasive human MRI.

Most MRI investigations, both clinically and at microscopic resolution, have studied the non-calcified articular cartilage, whose degradation is a hallmark of osteoarthritis. The lack of MRI study for the cartilage-bone interface region is due to the fact that this region is essentially invisible in routine MRI (i.e., MRI that uses spin-echo (SE) based pulse sequences). This invisibility is caused by two factors in cartilage MRI experiments. The first factor is the depth- and orientation-dependent T2 values in articular cartilage [23], which become increasingly shorter (1-5ms) towards the lower (deeper) part of the radial zone [24]. This short T2 in deep cartilage (and even shorter in ZCC) has its origin in cartilage biology and structure, including increased mineralization, higher packing density of collagen fibrils, reduction of water content, and interdigitated structure. The second factor that results in the invisibility for ZCC in MRI is the finite echo time (TE) in any spin-echo based MRI experiment, which is typically around 5-15ms. This finite time delay is necessary due to a number of technical requirements in electronics and imaging hardware [25, 26]. The combined consequence of these two experimental factors in MRI of cartilage is the appearance of a very-low intensity region between articular cartilage and its underlined bone in most images by MRI. Although this dark region could be just 1- or 2-pixel wide in clinical MRI, it can represent the entire cartilage-bone interface region. It is the darkness of the region (i.e., the lack of signal) that makes the characterization of this interface not possible.

In order to visualize the ZCC region in cartilage using MRI, the echo time in the imaging experiments must be made as short as possible. A number of different MRI methods have been developed that can achieve ultra-short echo time (UTE) or even zero echo time (ZTE) [27-30]. Some of these methods have been used successfully to image short-T2 connective tissues such as cartilage [31-34], tendon [35, 36], meniscus [37], and bone [38-41]. When using UTE/ZTE imaging sequences in MRI to measure relaxation times, it should be noted that most multi-echo measurements are problematic, since any multi-echo sequence requires the specimen to have long T2s [42], which is a pre-condition that the cartilage-bone interface cannot meet.

In this project, the magnetization-prepared imaging sequences, where a segment of contrast-inducing pulses was placed in front of the SE and UTE imaging sequences [24, 43], were used to quantify T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times in deep cartilage as well as the zone of calcified cartilage at microscopic resolution. Since little is known about the relaxation characteristics of the cartilage-bone interface (including deep cartilage, zone of calcified cartilage, and the top layer of subchondral bone), this project is critical in the investigation of imaging-based biomarkers for the cartilage-bone interface. In addition, both SE-based and UTE-based sequences were used in this project sequentially to study the same cartilage-bone specimens, which enabled the establishment of the complete profiles of relaxation properties from articular cartilage to the thickness of cartilage-bone interface. A clear imaged based understanding of this region could contribute to the clinical diagnostics of trauma-induced osteoarthritis, where a damaged cartilage-bone interface alters the nutrient supply from the bone to cartilage and the structural function of this region [44] and, hence, could change the relaxation properties of the tissue.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation:

A number of cartilage-bone blocks (~3×3×5mm3), in which the intact cartilage was attached to the underlining bone, were harvested from the central part of several canine humeral heads. These canines came from a tissue source that has supplied the same type of animal tissue to our research for over 20 years [12, 43, 45, 46]. The cartilage specimens were equilibrated in isotonic saline solution and sealed in precision NMR tubes with an internal diameter of 3.9 mm (Wilmad Glass, Buena, NJ).

Microscopic MRI (μMRI) Experiments

μMRI experiments were carried out at room temperature on a Bruker AVANCE II 300MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 7Tesla/89mm vertical-bore superconducting magnet and microimaging accessory (Bruker Instrument, Billerica, MA). A homemade 5mm solenoid coil was used in the experiments, which had a 90° hard pulse duration of 5.55μs and 180° hard pulse duration of 11.1μs. 2D imaging experiments had an acquisition matrix size of 256×128 (reconstructed into a 256×256 matrix size) for the spin-echo based sequences and 256×256 for the UTE based sequences, all with a slice thickness of 1mm. The field of view (FOV) was 5×5mm2, resulting in the 2D in-plane pixel size 19.5μm. The number of averages (NA) for T2 and T1ρ were 12 and for T1 experiment were 8 with a bandwidth of 50kHz. The articular surface of the specimens was set at the 0° orientations with respect to the main magnetic field B0 in all imaging experiments (hence the strongest dipolar interaction [47]). To measure the relaxation times more accurately, the magnetization-prepared pulse sequence format was used [24, 48] in both spin-echo imaging and UTE imaging, which placed a contrast-inducing header segment in front of a 2D imaging sequence. Since all timings in the imaging sequence are kept constant, the measurements of relaxations can be made more accurately and independent of the imaging parameters [24, 43, 49].

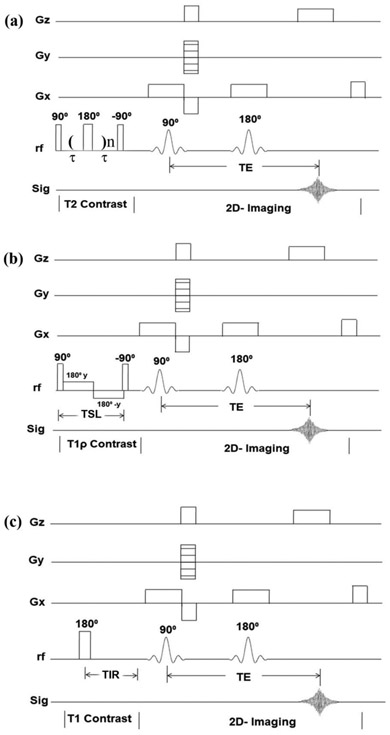

Quantitative SE-based T2, T1ρ and T1 Protocols

Quantitative SE-based imaging experiments followed the established protocols. Briefly, the same spin-echo 2D imaging sequence was used after different contrast-inducing header segments, a CPMG segment [43] for the T2 measurement, a spin-lock segment [49] for the T1ρ measurement, and an inversion-recovery (IR) segment [24] for the T1 measurement. All SE 2D imaging used a repetition time (TR) of 2000ms and the imaging echo time of 7.47ms. The CPMG echo spacing was 1 ms; and the number of echoes were increased in five steps to result in five T2-weighted 2D images, with the effective echo times for contrast TEc = 2, 8, 20, 40 and 60ms. The spin-lock header consisted of a 90° hard pulse followed by a spin-lock pulse, which had a strength of 2000 Hz (calibrated by the strength of the 90° hard pulse). The lengths of the spin-locking pulse (TSL) were 2, 8, 20, 40 and 60ms, which resulted in five T1ρ-weighted images. The inversion-recovery (IR) header had an 180° rf pulse with the inversion recovery times (TIR) of 0, 0.4, 1.1, 2.2 and 4.0s. The graphical sketches of the SE-based quantitative pulse sequences are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The graphical sketches showing the SE-based and magnetization-prepared pulse sequences of (a) quantitative T2, (b) quantitative T1ρ, (c) quantitative T1. (Gx - Slice selection gradient; Gy - Phase encoding gradient; Gz - read out gradient; TSL - spin lock period; TIR - inversion recovery time).

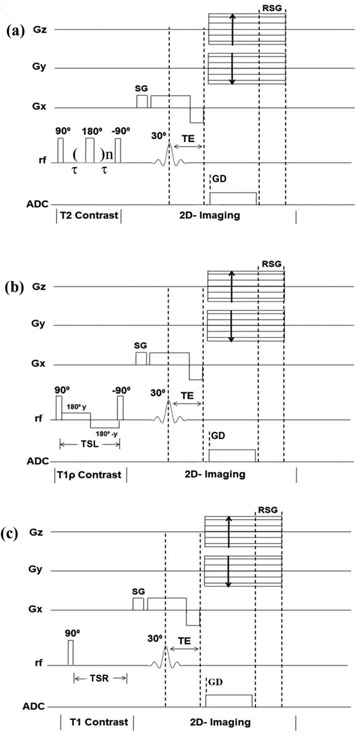

Quantitative UTE-based T2, T1ρ and T1 Protocols

Quantitative UTE-based imaging experiments adapted based on the same 2D UTE imaging sequence (Bruker Instrument) with the addition of different contrast-inducing header segments, at a repetition time of 200ms and imaging echo time of 238μs. A CPMG contrast-inducing header segment [43] was used for the T2 measurement; a spin-lock header segment [49] was used for the T1ρ measurement; and a saturation recovery segment [38] was used for the T1 measurement. The echo spacing in the CPMG segment was 100μs. The number of echoes in the CPMG header was increased in five steps to result in five T2-weighted images, with the effective contrast TEc = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0ms. The usual spin-locking header had strength of the spin-lock at 2000Hz, and the five lengths of the spin-locking pulse (TSL) at 0.05, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8 and 1ms, which resulted in five T1ρ-weighted images. The saturation recovery technique [38] had a non-selective 90° hard pulse followed by a large spoiler gradient to saturate signals from both long and short T2 components, before the 2D UTE imaging. The saturation recovery times (TSR) of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 and 1.0s were utilized, which resulted in five T1-weighted images. The UTE-based quantitative pulse sequences are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The graphical sketches showing the UTE-based and magnetization-prepared pulse sequences of (a) quantitative T2, (b) quantitative T1ρ, and (c) quantitative T1. (Gx - Slice selection gradient; Gy - Phase encoding gradient; Gz - read out gradient; TSL - spin lock period; TSR - saturation recovery time; SG - spoiler gradient; RSG - read spoiler gradient; GD - gradient delay).

Imaging and Data Analysis

Since multiple specimens yielded consistent results, the results in this report came from one of the cartilage-bone blocks to avoid any influence from the specimen dimensions and experimental variations. The five relaxation-weighted intensity images in each set of SE-based experiment were used to calculate one 2D quantitative image of relaxation. A 2D rectangular shaped region-of-interest (ROI) with a width of 20 continuous columns was defined on all 2D quantitative images. The relaxation values in the 2D ROI were extracted and row-averaged to become the 1D profile, to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of the profiles. The location of the ROI for quantitative analysis was in the middle of the cartilage specimen. The width of the ROI for quantitative analysis was identical for all images. There was no manual scaling or adjustment in plotting several cross-sectional profiles, which came from independent experiments, into one figure. Since the row-averaging occurs perpendicular to the tissue depth, the pixel resolution in the averaged 1D profile along the tissue depth is still 19.5 μm. For UTE-based experiments, the data in the region of ZCC were row-averaged at each pixel depth, from ZCC-1 (the first row of 20 continuous pixels) to ZCC-15 (the 15th row of 20 continuous pixels). 2D Image analysis was performed with the help of ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and statistical analysis was carried out in KaleidaGraph® (Synergy, PA).

Results

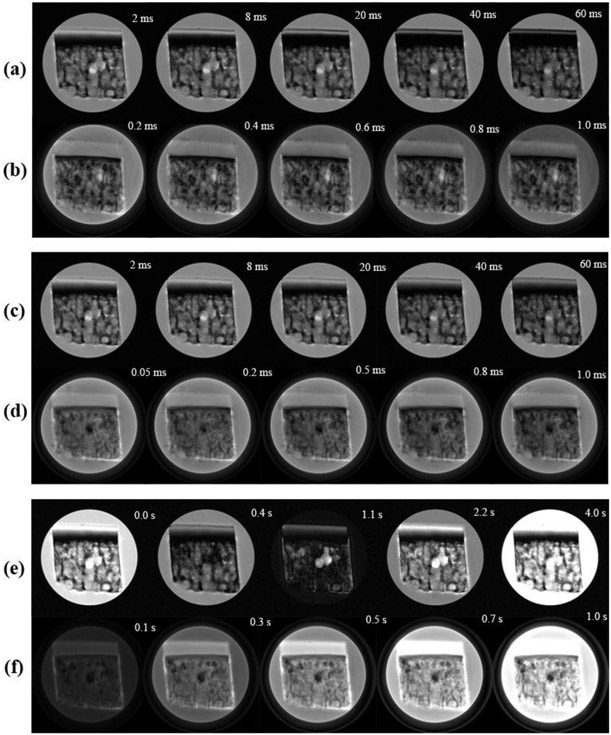

Proton Intensity Images of Cartilage and Cartilage-bone Interface by SE and UTE Sequences

The relaxation-weighted intensity images of a typical specimen are shown in Figure 3. Articular cartilage in the SE-based images (Fig 3a, 3c and 3e) exhibits the usual laminar appearance, which was caused by the dipolar interaction [23]. Articular cartilage in the UTE-based images of the same specimen (Fig 3b, 3d and 3f) appears much more homogenous and thicker. These images were acquired at the 0° orientation with respect to the main magnetic field B0, hence have the maximum effect from the dipolar interaction [24]. Although a dark region existed in all images between articular cartilage and bone, regardless of whether the image was from a SE sequence or a UTE sequence, the width of this dark region was much narrower in all UTE images.

Figure 3.

The intensity images of a cartilage-bone specimen acquired from μMRI pulse sequences of (a) magnetization-prepared spin-echo T2, (b) magnetization-prepared UTE-T2, (c) magnetization-prepared spin-echo T1ρ, (d) magnetization-prepared UTE-T1ρ, (e) magnetization-prepared spin-echo T1 and (f) magnetization-prepared UTE-T1, at the 0° orientation with respect to the external magnetic field BO (vertically up). The display thresholds for all images are kept consistent.

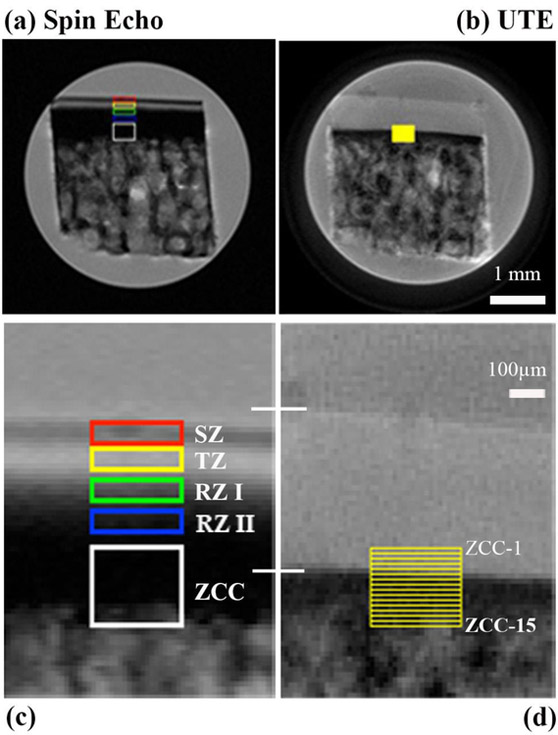

To illustrate the depth-dependent analysis for relaxation characteristics in different tissue zones of cartilage, Figure 4 shows the full-size images from the T2-weighted data (the first images in Fig 3a and 3b), marked with the region of interest. For the SE-based images (Fig 4a and 4c), it is clear that the lower half of the radial zone (RZ-II) as well as the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC) have very low intensity, which makes any quantification of tissue relaxation based on the image intensity unreliable. Hence, the calculation of the relaxation was not carried out in ZCC in SE-based experiments. In comparison, the pixel intensities in the UTE-based images (Fig 4b and Fig 4d) are still high in RZ-II and for at least half of ZCC. Hence the calculation of relaxation was carried out in ZCC in UTE experiments, at every pixel depth (every 19.5μm) from ZCC-1 to ZCC-15. The lack of visible variations across the width of the specimen in the cartilage images demonstrates the uniformity of the specimen width-size (horizontally), which justifies the row averaging of the 2D ROI values into the 1D depth-dependent profiles.

Figure 4.

Two T2-weighted intensity images, (a) spin-echo image and (b) UTE image, are marked with the region of interest (ROI) from which quantitative T2 relaxation times were calculated. (c) and (d) show the enlarged views of the ROIs in cartilage and cartilage-bone interface region. Two white lines across (c) and (d) mark the total thickness of articular cartilage in the two images. For UTE data, the zone of the calcified cartilage (ZCC) has a height of 15 pixels (each 19.5μm in size), which were calculated individually at each pixel location (ZCC-1 to ZCC-15).

Depth-dependent Profiles of T2, T1ρ and T1 Relaxation Times by SE and UTE Sequences

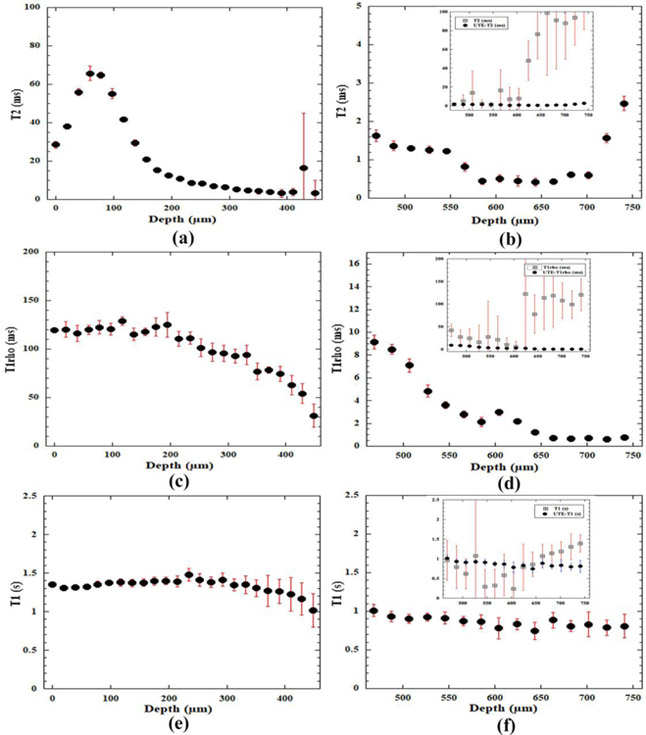

From the SE-based experiments, 2D maps of relaxation time in cartilage were calculated pixel-by-pixel based on the series of relaxation-weighted intensity images. The three plots on the left half of Figure 5 (5a, 5c and 5e) showed the depth-dependent relaxation profiles from the SE-based imaging experiments. The characteristics of the T2, T1ρ and T1 profiles resemble the previously reported profiles in literature [24, 49]. Briefly, these relaxation times have different sensitivities to the frequency of molecular motions, each sensing a range of different frequencies. When the normal axis of the articular surface was in parallel with the magnetic field, the dipolar interaction had the strongest influence to T2 relaxation in cartilage and could cause it to appear depth-dependently due to the zonal structure of articular cartilage, as shown in Fig 5a. When the spin-lock is sufficiently high (2000 Hz in this project), the influence of the dipolar interaction to cartilage relaxation can be minimized, which makes the cartilage T1ρ profile to have high values and much less depth-dependent (Fig 5c). Furthermore, the T1 profile of articular cartilage is known to be depth- and orientation-independent (Fig 5e). As the tissue depth increased from the articular surface (marked by 0μm depth) towards the deep tissue, the error bars can become large, to reflect the low intensity and low signal-to-noise ratio in deep cartilage. Around and after the depth of 460μm (not shown), the errors in the relaxation fitting can become excessively large, which reflect the large variation of the individual relaxation values at the same pixel depth in the ROI (since the ROI averaging was done for every single row of 20 consecutive values). This suggested that the SE sequences can only statistically measure up to about one half of the radial zone, which was approximately to the depth of 460μm from the articular surface for this canine humeral tissue.

Figure 5.

The depth-dependent profiles of relaxation times in articular cartilage and the cartilage-bone interface region by the spin-echo method ((a), (c), and (e)) and the UTE method ((b), (d), and (f)). The error bars indicate the variations of the calculation across the 20-pixel width of the specimen at the same tissue depth. A large error bar implies a significant variation among the values, hence, less reliable relaxation determination. The inserts in (b), (d) and (f) show both SE and UTE relaxation profiles in the calcified zone on the same vertical scale (the solid dots are from the UTE experiments; the open squares are from the SE experiments – the continuation from the profiles in (a), (c) and (e)). It is clear that the spin-echo experiments can only determine the relaxation to a tissue depth of approximately 460μm. The relaxation in deep cartilage can only be determined by the UTE-based sequences, shown by the plots on the right where relaxation profiles remain reliable until approximately to 700μm from the articular surface (0μm). (Note that the UTE plots use different vertical scales, in order to show clearly the trends of these profiles in ZCC.)

For the UTE-based experiments, quantitative T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times were calculated at each pixel depth from 460μm to 810μm (ZCC-1 to ZCC-15), which covered the deep tissue in the radial zone and the cartilage-bone interface. The main plots on the right half of Figure 5 (5b, 5d and 5f) showed that the relaxation profiles from the UTE-based experiments were statistically significant up to approximately the depth of 700μm. The three inserts in the three plots inside Fig 5b, 5d and 5f showed clearly the larger errors in the calculation when the SE-based quantitative sequences were used to measure the short T2 components in cartilage. The values of the UTE-based profiles at 460μm (the left edge of the profiles in Fig 5b, 5d, and 5f) matched the values of the corresponding SE-based profiles at the same thickness of 460μm (the right edge of the profiles in Fig 5a, 5c, and 5e). Since the two sequences were measuring the same specimen in the magnet sequentially, the excellent continuities of the T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation values between the SE experiments and the UTE experiments provided assurance for the cross-sequence correlation in different MRI methods.

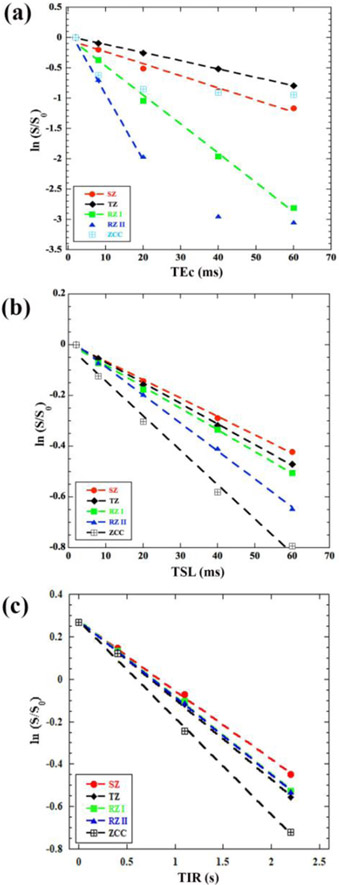

Fitting of SE-based and UTE-based Relaxation Times in Cartilage

The most critical way to examine the quality and characteristics of an exponential decay is to plot all intensity data points in a relaxation experiment using the natural logarithm scale. This is because any deviation from a straight line is much more noticeable than a deviation from an exponential decay. Figure 6 showed the SE-based data from the T2, T1ρ and T1 experiments, averaged over the individual ROIs in all histological zones. For the T2 data in Figure 6a, all five data points in the relaxation data in SZ, TZ, and RZ-I appeared linear and were used in the linear regression fitting for relaxation calculation. The T2 data points in RZ-II, however, became non-linear at longer echo times. This non-linearity at long delay indicated the values of the decaying signal reached the noise floor in the RZ-II region; hence the relaxation calculation only fitted the linear portion of the data (the first three points). The data points in the zone of calcified cartilage (ZCC) in the SE-based experiments showed much large errors in the T2 calculation and reached the noise floor much earlier (at or after the second data point). For this reason, T2 was not calculated for ZCC using the SE-based experiments. Similar examinations were done for the data points from the T1ρ experiment (Fig. 6b) and T1 experiments (Fig. 6c), where the regression fitting was done on the linearly decayed data for T1ρ (Fig 4b) and exponential inversion recovery for T1 (Fig. 6c). Table 1 summarized the T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation data in all histological zones of articular cartilage from the SE-based imaging experiments, together with the number of fitted data points (N) and the corresponding correlation factor (R2).

Figure 6.

The natural logarithm plots of the depth-dependent image intensities from the spin-echo based experiments, from which T2 (a), T1ρ (b) and T1 (c) are calculated, in all histological zones. Each plot contains five sets of data, each from one zone of articular cartilage. Each line showed the fitting of the data, where the fitting stops when the data is no longer linear.

Table 1:

Zonal averaged T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times and their corresponding R2 values of articular cartilage, calculated from the natural log plots of spin-echo-based μMRI data. N is the number of data points for fitting.

| Zone | T2 (ms), R2 (N) |

T1ρ (ms), R2 (N) |

T1 (s), R2 (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SZ | 52.3, 0.99 | 142.8, 0.99 | 1.61, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) | (5) | |

| TZ | 74.0, 0.99 | 125.0, 0.99 | 1.34, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) | (5) | |

| RZI | 20.8, 0.99 | 117.6, 0.99 | 1.39, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) | (5) | |

| RZ II | 8.62, 0.99 | 90.0, 0.99 | 1.37, 0.99 |

| (3) | (5) | (5) | |

| ZCC | Not calculated | 76.9, 0.99 | 1.02, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) |

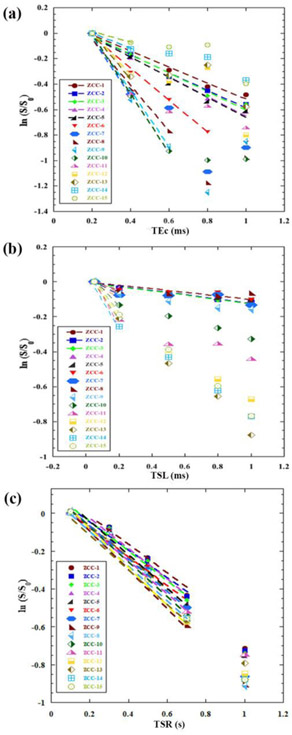

Similarly Figure 7 showed the natural logarithm plots of the UTE-based relaxation data from the T2, T1ρ and T1 experiments, at each pixel location (which corresponded to a depth step of 19.5μm) in the cartilage-bone interface region (ZCC-1 to ZCC-15). Similar analysis was applied to the UTE-based data, examining the non-linearity of the data and fitting only the linear potion of the data. The trends of the relaxation data in ZCC (in particular, ZCC-1) from the UTE-based experiments followed the general trends of the relaxation data from the SE-based calculation (in particular, RZ-II). The data were summarized in Table 2.

Figure 7.

The natural logarithm plots of the depth-dependent image intensities from the UTE based experiments, from T2 (a), T1ρ (b) and T1 (c) are calculated, in the deep and calcified cartilage (ZCC) pixel by pixel (ZCC-1 to ZCC-15) at an increment of 19.5μm depth. Each plot contains 15 sets of data, each from one-pixel depth of the specimen. Each line shows the fitting of the data, where the fitting stops when the data is no longer linear.

Table 2:

Single-row averaged T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times and their corresponding R2 values, calculated from the natural log plots of UTE-based μMRI data from the ZCC region of cartilage-bone specimens. N is the number of data points for fitting.

| ZCC (Pixel #) |

T2 (ms), R2 (N) |

T1ρ (ms), R2 (N) |

T1 (s), R2 (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZCC-1 | 1.58, 0.99 | 9.85, 0.98 | 1.01, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) | (4) | |

| ZCC-2 | 1.42, 0.99 | 8.47, 0.98 | 0.93, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) | (4) | |

| ZCC-3 | 1.32, 0.98 | 8.19, 0.98 | 0.91, 0.99 |

| (5) | (5) | (4) | |

| ZCC-4 | 1.29, 0.99 | 4.21, * | 0.89, 0.99 |

| (5) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-5 | 1.28, 0.98 | 3.64, * | 0.91, 0.99 |

| (5) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-6 | 0.79, 0.99 | 3.04, * | 0.92, 0.99 |

| (4) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-7 | 0.41, * | 1.96, * | 0.85, 0.97 |

| (2) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-8 | 0.52, 0.99 | 2.94, * | 0.76, 0.98 |

| (3) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-9 | 0.45, 0.99 | 2.13, * | 0.74, 0.99 |

| (3) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-10 | 0.43, 0.99 | 1.12, * | 0.79, 0.99 |

| (3) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-11 | 0.41, * | 0.69, * | 0.96, 0.99 |

| (2) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-12 | 0.61, * | 0.58, * | 0.82, 0.99 |

| (2) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-13 | 0.59, * | 0.71, * | 0.87, 0.99 |

| (2) | (2) | (4) | |

| ZCC-14 | 1.63** | 0.59, * | 0.78, 0.91 |

| (2) | (4) | ||

| ZCC-15 | 2.80** | 0.80, * | 0.81, 0.99 |

| (2) | (4) |

Note that the intensity decay data was examined individually at each pixel sequence (ZCC-#). Whenever the decay started to appear non-linear, the rest of the data points in the series were not used. Hence for the calculation that only used two data points, the R2 values were not quoted.

The final two values in T2 did not following the decreasing trend of T2 towards the deep tissue. Either they are not reliable because of large errors, or they represent not cartilage but some other tissue in this interface region.

Discussion

This study successfully combined the SE-based imaging and UTE-based imaging to quantify the T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times over both non-calcified and calcified cartilage at a high pixel-resolution (19.5 μm/pixel). This knowledge was previously unavailable as the SE-based sequences could not accurately measure the deep region of cartilage and cartilage-bone interface due to the regions’ very short T2 relaxation times of these regions. The relaxation profiles from both SE-based and UTE-based imaging experiments matched each other at the boundary region for the identical specimens. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first quantitative study of the entire cartilage depth by both spin-echo and UTE imaging at microscopic resolution.

MRI visualization of cartilage-bone interface

The cartilage-bone interface region contains several different types of tissue (including hyaline cartilage, calcified cartilage, subchondral bone) and has an interdigitated structure among these tissues. These tissues also have very different biomechanical properties. Studies noted that trauma-induced damages occur at the interface regions of several tissues, mostly due to the mismatch of tissues properties [50], which subsequently lead to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Since this region of cartilage has a higher density of collagen fibers, a lower concentration of water, a larger amount of minerals, and complicated morphology, T2 at this interface region can be very short. It is for this reason that the deep cartilage, as well as the interface between cartilage and bone, always appear dark in most MR images of cartilage. This invisibility hinders any potential study of this important structural region and also introduces large errors in any measurement of cartilage thickness [34].

A possible solution in the visualization of the deep cartilage and the interface region is to reduce the echo time in MRI, using pulse sequences such as the ultra-short echo time in MRI [51, 52]. As evident from the comparison of intensity images by both SE and UTE sequences on the same specimen (Fig 3 and Fig 4), articular cartilage in the UTE images is thicker. Since cartilage thickness is an important measure in diagnostic MRI for osteoarthritis and other related joint diseases, a better visualization provides a more accurate measurement of cartilage. A recent paper [34] showed that the under-estimation of the total cartilage thickness in MRI could be significant (up to 32% of the tissue thickness). This underestimation is also pulse-sequence dependent, imaging-parameter dependent (e.g., image resolution), cartilage-orientation dependent (dipolar interaction), and joint-surface-topography dependent [53, 54].

MRI quantification of relaxation characteristics in cartilage-bone interface

The visibility of the cartilage-bone interface enables the characterization of this region. Although it is possible to determine the relaxation times by varying an imaging parameter (e.g., progressively increasing the echo time during a series of UTE acquisitions to calculate T2*), this type of approach could introduce measurement errors in the quantification of relaxation parameters, due to the influence of imaging gradient pairs and the amount of image artifacts [24, 48, 55]. For example, although the depth-dependent profiles of T2* and T2 relaxation were found to have very similar shapes, the values of T2* by a standard multi-echo sequence were only about 1/3 of the T2 by the magnetization-prepared sequence [56]. This type of influence on the signal decay in relaxation calculation is resolution and sequence dependent.

In our work, the T2, T1ρ and T1 imaging pulse sequences were based on the concept of the magnetization-prepared imaging sequence [48], all of which have two well-separated segments: a header segment that prepares the magnetization, and a subsequent 2D imaging segment. During a series of T2-weighted imaging experiments, for example, only the timing of the header segment is altered while all timings of the imaging segment are kept constant. Since there is no gradient pulse in the header segment, the intrinsic diffusion-weighting and the T2-weighting during the imaging echo time TEi are both constant. Their effects, therefore, do not influence the subsequent relaxation calculation [55]. Consequently, the relaxation times in the specimen can be determined more accurately. A downside of this more accurate, quantitative approach is the longer experimental time, since each relaxation weighting is acquired individually.

Experimental Limitations

At a 2D in-plane pixel size of 19.5μm, the use of spin-echo and UTE sequences in this study gives the most complete measurement of relaxation characteristics across most of cartilage/bone interface at the highest resolutions in ex vivo non-invasive imaging. As evident in this study, however, the images from the current UTE sequences with a minimum TE of 230μs still cannot resolve the entire dark region in this interface (i.e., there is still a narrower dark region between cartilage and bone, as seen in Fig 4b).

In several previous unrelated studies of nearly identical canine humeral cartilage using polarized light microscope (we have been using the identical canine tissue from the same provider for nearly 20 years), the interface region in this type of tissue was estimated to be about 80μm in thickness (data not shown), which would be about 4 pixels at our 19.5μm resolution. However, histology shows that this interface region is waved and interdigitated among these tissues. To truly understand which portion of the dark region in high resolution MRI corresponds to which of the structural tissues in the cartilage-bone interface region, comparative studies between μMRI and histology at even higher optical resolutions are needed in any future investigation. It should be noted that any histological process, which prepares tissue for thin sections for optical imaging, could also induce measurement error, such as tissue shrinkage and section distortion.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated in this study that the characteristics of T2, T1ρ and T1 relaxation times in articular cartilage and cartilage-bone interface can be studied in μMRI by using a combination of SE- and UTE-based imaging sequences. The quantitative values of T2, T1ρ and T1 are consistent at the overlapping deep cartilage when using both imaging sequences. This study, to the best of our knowledge, was the first to systematically study the interface region between cartilage and bone that remained invisible to most of conventional MRI studies in the past, at microscopic resolution. This new ability to probe the cartilage-bone interface could be utilized to detect specific damages in the interface region, which exist in trauma-induced osteoarthritis.

Highlights.

Visualization of both articular cartilage and the cartilage-bone interface

Quantitative T2, T1ρ and T1 mapping at 19.5 μm

Spin-echo and UTE imaging on the same samples

Correlation of relaxation mapping by spin-echo and UTE imaging

Acknowledgments

Yang Xia is grateful to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for a R01 grant (AR 9047). The authors thank Dr. Hani Sabbah (Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit) for providing the canine specimens, and Ms. Carol Searight (Department of Physics, Oakland University) for editorial comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Maroudas A, Physicochemical properties of articular cartilage, in: Freeman MAR (Ed.) Adult articular cartilage, 2nd ed, Pitman Medical, Kent, England, 1979, pp. 215–290. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Buckwalter J, Mankin H, Articular Cartilage Repair and transplantation, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 41 (1998) 1331–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bullough PG, Yawitz PS, Tafra L, Boskey AL, Topographical variations in the morphology and biochemistry of adult canine tibial plateau articular cartilage, J Orthop Res, 3 (1985) 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hoemann CD, Lafantaisie-Favreau CH, Lascau-Coman V, Chen G, Guzman-Morales J, The cartilage-bone interface, The journal of knee surgery, 25 (2012) 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Redler I, Mow VC, Zimny ML, Mansell J, The Ultrastructure and Biomechanical Significance of the Tidemark of Articular Cartilage, Clin. Orthop. and Related Topics, 112 (1975) 357–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bullough PG, Jagannath A, The morphology of the calcification front in articular cartilage. Its significance in joint function, J Bone Joint Surg Br, 65 (1983) 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Havelka S, Horn V, Spohrova D, Valough P, The calcified-non calcified cartilage interface; the tidemark, Acta Biol Hung 34 (1984) 271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Oegema TR Jr., Carpenter RJ, Hofmeister F, Thompson RC Jr., The interaction of the zone of calcified cartilage and subchondral bone in osteoarthritis, in: Microsc Res Tech, United States, 1997, pp. 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xia Y, Momot KI, Biophysics and Biochemistry of Cartilage by NMR and MRI, in, the Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 760. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Duvvuri U, Kudchodkar S, Reddy R, Leigh JS, T(1rho) relaxation can assess longitudinal proteoglycan loss from articular cartilage in vitro, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 10 (2002) 838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alhadlaq H, Xia Y, Moody JB, Matyas J, Detecting Structural Changes in Early Experimental Osteoarthritis of Tibial Cartilage by Microscopic MRI and Polarized Light Microscopy, Ann Rheum Dis, 63 (2004) 709–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xia Y, Zheng S, Bidthanapally A, Depth-dependent Profiles of Glycosaminoglycans in Articular Cartilage by μMRI and Histochemistry, J Magn Reson Imaging, 28 (2008) 151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li X, Pai A, Blumenkrantz G, Carballido-Gamio J, Link T, Ma B, Ries M, Majumdar S, Spatial distribution and relationship of T1rho and T2 relaxation times in knee cartilage with osteoarthritis, Magn Reson Med, 61 (2009) 1310–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zheng S, Xia Y, The impact of the relaxivity definition on the quantitative measurement of glycosaminoglycans in cartilage by the MRI dGEMRIC method, Magn Reson Med, 63 (2010) 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang N, Xia Y, Orientational dependent sensitivities of T2 and T1rho towards trypsin degradation and Gd-DTPA (2-) presence in bovine nasal cartilage, MAGMA, 25 (2012) 297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Prasad AP, Nardo L, Schooler J, Joseph GB, Link TM, T(1)rho and T(2) relaxation times predict progression of knee osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 21 (2013) 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lee JH, Badar F, Matyas J, Qu X, Xia Y, Topographical variations in zonal properties of canine tibial articular cartilage due to early osteoarthritis: a study using 7-T magnetic resonance imaging at microscopic resolution, MAGMA, 29 (2016) 681–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Carballido-Gamio J, Link TM, Majumdar S, New techniques for cartilage magnetic resonance imaging relaxation time analysis: texture analysis of flattened cartilage and localized intra- and inter-subject comparisons, Magn Reson Med, 59 (2008) 1472–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Guermazi A, Crema MD, Roemer FW, Compositional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measures of Cartilage--Endpoints for Clinical Trials of Disease-modifying Osteoarthritis Drugs?, J Rheumatol, 43 (2016) 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Link TM, Li X, Establishing compositional MRI of cartilage as a biomarker for clinical practice, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Xia Y, Resolution 'scaling law' in MRI of articular cartilage, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 15 (2007) 363–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Xia Y, MRI of articular cartilage at microscopic resolution, Bone and Joint Res, 2 (2013) 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xia Y, Farquhar T, Burton-Wurster N, Lust G, Origin of cartilage laminae in MRI, J Magn Reson Imaging, 7 (1997) 887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xia Y, Relaxation Anisotropy in Cartilage by NMR Microscopy (μMRI) at 14 μm Resolution, Magn Reson Med, 39 (1998) 941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gold GE, Pauly JM, Macovski A, Herfkens RJ, MR spectroscopic imaging of collagen: tendons and knee menisci, Magn Reson Med, 34 (1995) 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zheng S, Xia Y, The Influence of Specimen and Experimental Conditions on NMR and MRI of Cartilage, in: Xia Y, Momot KI (Eds.) Biophysics and Biochemistry of Cartilage by NMR and MRI, The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2017, pp. 347–372. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM, Magnetic resonance: an introduction to ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging, J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr, 27 (2003) 825–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Park JY, Garwood M, Fast and quiet MRI using a swept radiofrequency, J Magn Reson, 181 (2006) 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Qian Y, Boada FE, Acquisition-weighted stack of spirals for fast high-resolution three-dimensional ultra-short echo time MR imaging, Magn Reson Med, 60 (2008) 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Larson PE, Han M, Krug R, Jakary A, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Henry RG, McKinnon G, Kelley DA, Ultrashort echo time and zero echo time MRI at 7T, Magma, 29 (2016) 359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Freeman DM, Bergman G, Glover G, Short TE MR microscopy: accurate measurement and zonal differentiation of normal hyaline cartilage, Magn Reson Med, 38 (1997) 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Du J, Takahashi AM, Bae WC, Chung CB, Bydder GM, Dual inversion recovery, ultrashort echo time (DIR UTE) imaging: creating high contrast for short-T(2) species, Magn Reson Med, 63 (2010) 447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shao H, Chang EY, Pauli C, Zanganeh S, Bae W, Chung CB, Tang G, Du J, UTE bicomponent analysis of T2* relaxation in articular cartilage, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 24 (2016) 364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang N, Badar F, Xia Y, Experimental Influences in the Accurate Measurement of Cartilage Thickness in MRI, Cartilage, (2018) 1947603517749917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Benjamin M, Bydder GM, Magnetic resonance imaging of entheses using ultrashort TE (UTE) pulse sequences, J Magn Reson Imaging, 25 (2007) 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Du J, Carl M, Diaz E, Takahashi A, Han E, Szeverenyi NM, Chung CB, Bydder GM, Ultrashort TE T1rho (UTE T1rho) imaging of the Achilles tendon and meniscus, Magn Reson Med, 64 (2010) 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ma YJ, Carl M, Shao H, Tadros AS, Chang EY, Du J, Three-dimensional ultrashort echo time cones T1rho (3D UTE-cones-T1rho ) imaging, NMR Biomed, 30 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Reichert IL, Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, He T, Chappell KE, Holmes J, Girgis S, Bydder GM, Magnetic resonance imaging of cortical bone with ultrashort TE pulse sequences, Magn Reson Imaging, 23 (2005) 611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Techawiboonwong A, Song HK, Wehrli FW, In vivo MRI of submillisecond T(2) species with two-dimensional and three-dimensional radial sequences and applications to the measurement of cortical bone water, NMR Biomed, 21 (2008) 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bae WC, Chen PC, Chung CB, Masuda K, D'Lima D, Du J, Quantitative ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI of human cortical bone: correlation with porosity and biomechanical properties, J Bone Miner Res, 27 (2012) 848–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ma YJ, Chang EY, Bydder GM, Du J, Can ultrashort-TE (UTE) MRI sequences on a 3-T clinical scanner detect signal directly from collagen protons: freeze-dry and D2 O exchange studies of cortical bone and Achilles tendon specimens, NMR Biomed, 29 (2016) 912–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tyler DJ, Robson MD, Henkelman RM, Young IR, Bydder GM, Magnetic resonance imaging with ultrashort TE (UTE) PULSE sequences: technical considerations, J Magn Reson Imaging, 25 (2007) 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zheng S, Xia Y, Effect of phosphate electrolyte buffer on the dynamics of water in tendon and cartilage, NMR Biomed, 22 (2009) 158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Oegema TR Jr., Lewis JL, Thompson RC Jr., Role of acute trauma in development of osteoarthritis, Agents Actions, 40 (1993) 220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang N, Xia Y, Experimental issues in the measurement of multi-component relaxation times in articular cartilage by microscopic MRI, J Magn Reson, 235 (2013) 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang N, Kahn D, Badar F, Xia Y, Molecular origin of a loading-induced black layer in the deep region of articular cartilage at the magic angle, J Magn Reson Imaging, 41 (2015)1281–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Xia Y, Moody J, Alhadlaq H, Orientational dependence of T2 relaxation in articular cartilage: A microscopic MRI (μMRI) study, Magn Reson Med, 48 (2002) 460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Haase A, Brandl M, Kuchenbrod E, Link A, Magnetization-prepared NMR Microscopy, J. Magn. Reson. A, 105 (1993) 230–233. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wang N, Xia Y, Depth and orientational dependencies of MRI T2 and T1rho sensitivities towards trypsin degradation and Gd-DTPA(2-) presence in articular cartilage at microscopic resolution, Magn Reson Imaging, 30 (2012) 361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bayrak E, Ozcan B, Erisken C, Cartilage-Bone Interface Features, Scaffold and Cell Options for Regeneration, Journal of Tissue Science & Engineering, 7 (2016) 1000174. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Du J, Diaz E, Carl M, Bae W, Chung CB, Bydder GM, Ultrashort echo time imaging with bicomponent analysis, Magn Reson Med, 67 (2012) 645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Qian Y, Williams AA, Chu CR, Boada FE, Multicomponent T2* mapping of knee cartilage: technical feasibility ex vivo, Magn Reson Med, 64 (2010) 1426–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Xia Y, Moody J, Alhadlaq H, Burton-Wurster N, Lust G, Characteristics of Topographical Heterogeneity of Articular Cartilage over the Joint Surface of a Humeral Head, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 10 (2002) 370–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lee JH, Badar F, Kahn D, Matyas J, Qu X, Chen CT, Xia Y, Topographical Variations of the Strain-dependent Zonal Properties of Tibial Articular Cartilage by Microscopic MRI, Connect Tissue Res, 55 (2014) 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Xia Y, Contrast in NMR Imaging and Microscopy, Concepts in Magn Reson, 8 (1996) 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Xia Y, Zheng S, Reversed laminar appearance of articular cartilage by T1-weighting in 3D fat-suppressed spoiled gradient recalled echo (SPGR) imaging, J Magn Reson Imaging, 32 (2010) 733–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]