Vascular erectile dysfunction (ED) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) share common risk factors including obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and smoking. ED and CVD also have common underlying pathologic mechanisms, including endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and atherosclerosis1. Despite these close relationships, evidence documenting ED as an independent predictor of future CVD events is limited.

We therefore leveraged the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) – an ethnically-diverse, community-based, multi-site prospective cohort study – to examine the value of self-reported ED for predicting incident coronary heart disease (CHD) and CVD in those free of these CVD at baseline. Details of MESA have been described previously2. Male MESA participants who attended Visit 5, and answered the single Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) question3 on ED symptoms were considered for our analysis (n = 1914). A participant was considered to have ED if he responded “Never able” or “Sometimes Able” to the MMAS question. After excluding 155 participants with a CVD event before Visit 5, 1757 participants were followed for 3.8 years (IQR 3.5–4.2) and outcomes of hard CHD and CVD events were assessed. Hard CVD events included all hard CHD events (myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest and CHD death), plus stroke and stroke death. Participants provided informed consent and each study site obtained approval from their institutional review board.

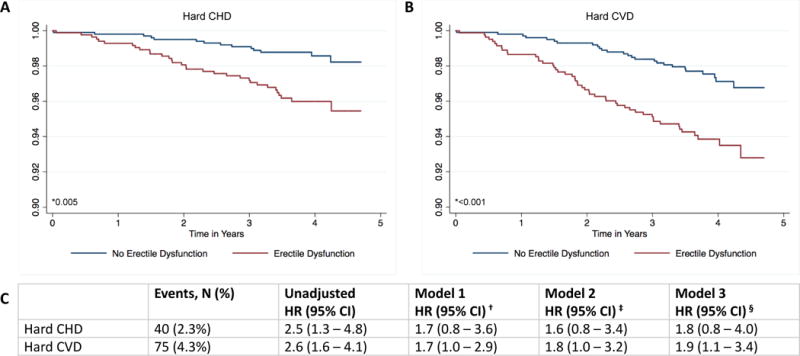

Cox proportional hazard models were developed to calculate hazard ratios for the outcomes by ED status (ED yes/no) after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity and education (Model 1), further adjusting for smoking status, diabetes, family history of CHD, Total/HDL cholesterol ratio, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use, and lipid lowering medication use (Model 2), and further adjusting for beta-blocker use and depression assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) score (CES-D>16 vs ≤16) (Model 3).

To further assess the potential bidirectional relationship of prior CVD with ED, an additional shifted-time cross-sectional analysis was conducted to see if an interim CVD event before MESA Visit 5 was associated with self-reported ED at Visit 5. For this analysis, all 1,914 participants with an ED assessment were included in a multivariable-adjusted logistic regression adjusting for the above-mentioned covariates.

The mean age of the 1,914 participants was 69±9.2 years and 42.3% were Caucasian, 24.2% African American, 10.5% Chinese American and 22.9% Hispanic. ED symptoms were reported by 877 (45.8%) participants. Participants with ED were more likely to have diabetes and a family history of CHD. They were also more likely to use beta-blocker, anti-hypertensive, lipid-lowering, and anti-depressant medications. Over the 3.8-year follow-up, there were a total of 40 CHD and 75 CVD hard events. A significantly greater proportion of participants with ED experienced hard events compared to those without ED (CHD hard events: 3.4% vs 1.4%, p<0.001; CVD hard events: 6.3% vs 2.6%, p<0.001).

In the unadjusted Cox models, ED was a significant predictor of both hard CHD (HR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.3-4.8) and CVD (HR: 2.6, 95% CI:1.6-4.1) events. In the fully adjusted models (Model 3), ED remained a significant predictor of hard CVD events (HR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.1-3.4), while hard CHD events became non-significant, albeit with a similar point estimate of risk (Figure).

Figure. Association between ED and incident CHD and CVD hard events among 1,757 male MESA participants.

A and B, Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival function curves for hard CHD and CVD events by ED status. C, Cox proportional hazard ratios (95% CIs) of hard CHD and CVD events by ED status. *P value by log-rank testing. †Model 1 adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and education. ‡ Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 + smoking status, diabetes, family history of CHD, Total/HDL cholesterol ratio, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use and lipid lowering medication use. §Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 + depression and beta blocker use. CHD indicates coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ED, erectile dysfunction; and HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

In the shifted-time cross-sectional analysis, a significant association was also seen between prior CVD event and ED at visit 5 (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.4-3.2) which remained significant but was attenuated by medication use and depression in the fully adjusted models (OR:1.7, 95% CI: 1.1-2.6).

In an ethnically-diverse, community-based cohort, ED was found to be a significant predictor of hard CVD events after adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors, depression, and beta-blocker use. To our knowledge, this is the first study of ED and subsequent CVD that adjusted for depression and beta-blocker use. Our results suggest that these two factors may partially mediate the relationship between prior CVD and subsequent ED, but do not attenuate the prospective association of ED and incident CVD. Our findings strengthen the existing evidence for the independent association between ED and incident CVD, and could have important clinical implications for risk stratification in middle-aged men. We have previously documented increased subclinical atherosclerosis in those who subsequently report ED4. In 2017, the UK QRISK score was the first to incorporate ED as an independent risk factor for CVD5, yet ED remains absent from U.S. risk prediction guidelines. Our results may justify more aggressive preventive therapy in such patients.

Our study had certain limitations. While similar to primary care assessment of ED, the single MMAS question does not distinguish between vascular and non-vascular types of ED, which may have attenuated the association between ED and CVD. Additionally, since our follow-up was just 3.8 years, additional 10-year data on the risk predictive value of ED are needed.

In conclusion, our study provides some of the strongest evidence to date for the independent predictive value of ED in a modern, multi-ethnic, well-phenotyped cohort.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by grants UL1-TR-000040, and UL1-TR-001079 from National Center for Research Resources. This publication was developed under a STAR research assistance agreement, No. RD831697 (MESA Air), awarded by the U.S Environmental Protection Agency. It has not been formally reviewed by the EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and the EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication.

Footnotes

Data Sharing Footnote

MESA data is available by request at the study website at https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/.

Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures pertinent to this work.

References

- 1.Shin D, Pregenzer G, Gardin JM. Erectile dysfunction: a disease marker for cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19:5–11. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181fb7eb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derby CA, Araujo AB, Johannes CB, Feldman HA, McKinlay JB. Measurement of erectile dysfunction in population-based studies: the use of a single question self-assessment in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Int J Impotence Res. 2000;12:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman DI, Cainzos-Achirica M, Billups KL, DeFilippis AP, Chitaley K, Greenland P, Stein JH, Budoff MJ, Dardari Z, Miner M, Blumenthal RS, Nasir K, Blaha MJ. Subclinical Vascular Disease and Subsequent Erectile Dysfunction: The Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Clin Cardiol. 2016;39:291–298. doi: 10.1002/clc.22530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Julia Hippisley-Cox, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]