Abstract

Background

India's Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) is among the world's largest public nutritional programs, providing daily nutritional supplements and other public health and educational services to pregnant and nursing women, children aged <6 y, and adolescent girls.

Objective

We estimated the long-term association between early-childhood ICDS nutrition and adult outcomes.

Methods

We used follow-up data from a controlled nutritional trial conducted during 1987–1990 in 29 villages near the city of Hyderabad. In 15 intervention villages, a balanced protein-calorie supplement—made from locally available corn-soya ingredients and called upma—was offered to pregnant women and to children <6 y old. No supplement was offered in the 14 control villages. During 2010–2012, adults born during the trial were re-surveyed (n = 715 in the intervention arm and n = 645 in the control arm). We used probit regression and propensity score-matching methods to estimate the association between birth in an intervention village and rates of secondary and graduate education completion, marriage, and employment or enrollment in higher education of these adults.

Results

Adults born in the intervention group during the trial, compared with the control group, were 9% (95% CI: 0.04, 0.14; P < 0.01) more likely to complete secondary school and 11% (95% CI: 0.06, 0.15; P < 0.01) more likely to complete graduate education, were 6% (95% CI: −0.11, −0.01; P < 0.05) less likely to be ever-married at age 20–25 y, and were 5% (95% CI: 0, 0.11; P < 0.05) more likely to be employed or enrolled in higher education. The estimated associations for graduate education completion and employment-study rates were greater for men, whereas the associations for secondary education and ever-married rates were greater for women.

Conclusion

Exposure to nutritional supplement in utero or during the first 3 y of life was associated with improved adult educational and employment outcomes and lower marriage rates in India.

Keywords: India, APCAPS, ICDS, fetal origins, child development

Introduction

India has the highest number of stunted and wasted children in the world. The 40 million stunted and 17 million wasted children <5 y old (under-5) constitute 26% and 34% of global totals, respectively (1–4). Although rates of under-5 stunting and wasting in India have declined from 48% and 43% in 2006 to 39% and 30% in 2014 (1, 3, 5), the degree of improvement varied considerably across regions. Many of the most populous states, including Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh, made the least progress. More than 40% of children remain stunted and >30% remain underweight in these states (1).

Undernutrition during the first 1000 d of life is associated with a higher incidence of childhood disease morbidity and mortality, as well as poor health, cognitive, academic, and economic productivity outcomes in adulthood (6–21). The future economic cost of growth faltering among under-5 children in India, through lost schooling and economic productivity, was estimated to be $37.9 billion in 2016 (22).

A limited number of studies have looked at the long-term association between intrauterine or early-childhood nutrition and future non–health-related outcomes in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (10, 20). A trial of protein-rich nutritional supplementation was conducted in 1969–1976 by the Institute of Nutrition for Central America and Panama (INCAP) in Guatemala. Follow-up surveys of ∼1500 children in the study estimated that the intervention group had higher reading and cognitive test scores by 0.24–0.28 SDs compared with the control group at ages 25–42 y (13, 14, 23). In addition, intervention-group women completed an average of 1.2 more school grades and men had 46% higher wages compared with their control-group counterparts. A study in 3493 participants in Pelotas, Brazil, found that children who were breastfed for ≥12 mo completed 0.9 more school grades and had ∼25% higher wages at age 30 y compared with those who were breastfed for <1 mo (24). Three studies in Tanzania, Philippines, and Indonesia also found similar positive links between early-life nutrition and future educational and labor market outcomes (25–27). However, these findings probably are not generalizable to India, where child undernutrition rates are very high and educational and labor market conditions are markedly different. In addition, little is known about whether early-life nutritional interventions may affect marriage and partnership outcomes in adulthood in LMICs.

In a previous study, we followed up 13- to 18-y-old Indian children who were exposed to a daily nutritional supplement in utero or during the first 3 y of life in a 1987–1990 trial in 29 villages near Hyderabad. We found that in intervention villages, 7.8% more children were enrolled in school and they completed an average of 0.8 higher grades of schooling (16). In this current study, we followed the cohort into adulthood (20–25 y of age) and estimated associations between the nutritional supplement and educational, marriage, and labor market outcomes.

Methods

Andhra Pradesh children and parents study

During the period from 1987 to 1990, the National Institute of Nutrition conducted a controlled trial (called the Hyderabad Nutrition Trial) to evaluate the effect of a nutritional supplement during pregnancy on the birth weights of newborn children. The intervention that was being tested was a principal component of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), a national program for nutrition and development of women and children. Along with the free supplementary nutrition—a cooked meal or ready-to-cook dry meal per day—for all children aged ≤6 y, pregnant and nursing mothers, and adolescent girls, ICDS also provides preschool education, immunization, health checkups and referral services, and nutritional and health education. The services are provided from a village-level mother-child center (known as Anganwadi), which is staffed by a local woman worker and a helper. ICDS coverage became universal in 2009 through 1.3 million Anganwadi centers.

The ICDS program was implemented in a phased manner during the 1980s and 1990s in India. The Hyderabad Nutrition Trial introduced the supplementary nutrition component during 1987–1990 in villages near the city of Hyderabad in the unified state of Andhra Pradesh. That part of Hyderabad is now part of the new Telangana state.

First, 2 adjacent subdistricts near Hyderabad were selected, one of which already had the ICDS program (intervention arm), whereas the other was awaiting implementation (control arm). Then, all of the villages within a 10-km radius from a prominent central village in each subdistrict were included, resulting in 15 intervention and 14 control villages. In the intervention villages, pregnant women and children aged ≤6 y were offered a daily cooked meal—called upma—which was prepared from a locally available corn-soya blend with soybean oil (28). The meal was not fortified with any additional nutrients and provided, on average, 500 kcal of energy and 20–25 g protein to women and half of those amounts to children.

Control villages received the supplementary nutrition 3 y after the study ended. The availability of other public health programs, such as anemia control in pregnancy through iron and folic acid tablets, immunization of children, and primary health care, was similar across intervention and control villages, although supplementary nutrition might have altered the uptake rates of these services (28). The trial and follow-up surveys have been discussed in detail in previous studies (28, 29).

Follow-up surveys

All children born between 1 January 1987 and 31 December 1990 in 29 villages were enrolled in the original trial. During 2003–2005, a follow-up survey identified 1815 women who had participated in the trial and gave birth to ≥1 child during 1987–1990 who was currently alive (hereafter referred to as the index child). Of the 2601 index children, 1492 could be matched with baseline records from the trial and were invited to participate in the survey administered from a clinic in the village. In the intervention and control villages, 654 (of 801 invited) and 511 (of 691 invited) children and their mothers participated.

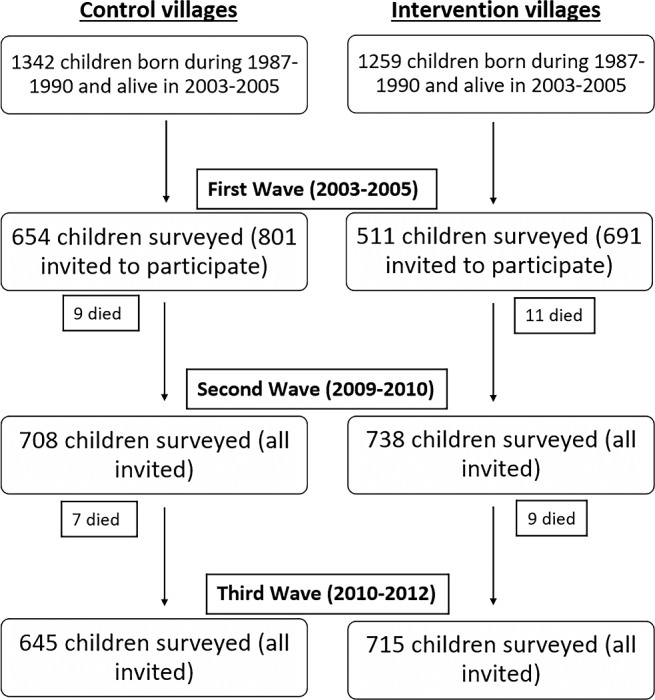

As shown in Figure 1, the second and third waves of the follow-up surveys were conducted in 2009–2010 and 2010–2012. All surviving index children were invited to clinics, and 1446 (708 intervention and 738 control) and 1360 (715 intervention and 645 control) children, respectively, participated in these surveys (30). The follow-up surveys carried out under the Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study (APCAPS) collected a wide variety of data on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, medical history, mental and reproductive health, anthropometric measurements, cardiovascular physiology, spirometry, and biomarkers (31). The surveys were conducted by a field team from the National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad and supervised by academic and policy experts (32). A 2014 study discussed the data collection process and APCAPS cohort profile in detail (31).

FIGURE 1.

Number of index children covered in APCAPS household survey rounds. APCAPS, Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study.

Ethics statement

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad. Local administrative authorities in all villages also provided approval, and participants and their parents or guardians provided informed consent.

Regression analysis

We used the third wave of APCAPS to estimate associations between birth in intervention villages and the outcomes of 20- to 25-y-old adults (index children). We used probit regression models to examine whether the adults 1) completed at least secondary school (i.e. class X/XII, intermediate, vocational course, or equivalent), 2) completed at least graduate-level schooling (i.e., bachelor's degree, diploma, or equivalent), 3) were ever married (currently married, widowed, or divorced) up to the time of the third wave, and 4) were employed in paid or unpaid (e.g., household farm) work or enrolled in higher education (degree or training courses). Employment and educational enrollment were combined in the data and could not be separated. Therefore, the indicator captured either labor market entry before the survey or skill acquisition for future entry.

The covariates in our regression were age, sex (whether female), and birth order of the index child and indicators of parental schooling attainment (literate, completed primary school, or completed secondary school or above). We also included the following socioeconomic indicators: religion (Hindu or other), caste (scheduled caste or scheduled tribe, other backward class), and household standard of living as measured by quintiles of a composite asset index (33, 34). We clustered the SEs of all regression models at the village level.

Propensity score-matching analysis

There were significant differences in observable socioeconomic and demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups that could have influenced differences in outcomes. Unobserved differences between the intervention and control groups, which, if correlated with intervention uptake, could have also affected outcome indicators. To mitigate potential biases arising from the group differences, we also used a quasi-experimental methodology of propensity score matching (PSM) (35–38).

First, we conducted a probit regression of intervention assignment on the same covariate set of household, parental, and individual characteristics as used in the regression analysis described above. Then, on the basis of the predicted probability of assignment from the model, known as the propensity score, we matched adults from the intervention villages with similar adults from the control villages. We used a Kernel (Epanechnikov) matching algorithm and only considered observations from the 2 groups with overlapping propensity scores (called “common support”) (39).

After matching and assuming that unobservable factors were distributed randomly across the intervention and control groups, the differences in average outcomes (schooling attainment, marriage, and employment or higher-education enrollment) between the 2 groups can be attributed to the nutritional supplement.

We conducted regressions and PSM analysis on the full sample and separately for men and women. We considered P values <0.05 to be significant.

Sensitivity and quality of matching analysis

The extent to which systematic group differences are reduced under PSM methodology may depend on the algorithm used to match intervention observations with similar control observations (39, 40). Therefore, we tested the sensitivity of our PSM results to 2 additional matching algorithms by using a one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching algorithm with replacement (within a probability radius of 0.01) instead of Kernel matching and comparing an intervention observation with 3 nearest neighbors on the basis of propensity scores (with replacement and with no restriction on probability radius) instead of a single nearest neighbor, adjusting the SEs by using a bias correction method in both cases (41).

We tested the quality of matching (i.e., the extent to which PSM reduced systematic differences in the characteristics of the intervention and control groups) in 3 ways. First, we estimated the mean bias (percentage differences in the values of covariates) between the 2 groups. If matching quality was good, the estimated average bias should decrease substantially from pre- to postmatching. Second, we conducted a likelihood ratio test of the joint significance of covariates before and after matching. If we failed to reject the nonsignificance null hypothesis after matching, it would indicate that matching successfully reduced dissimilarities between the 2 groups. Third, we calculated the pseudo-R2 from a re-estimation of propensity scores by using the matched intervention-control sample (42). A successful PSM should reduce the value of pseudo-R2 substantially from pre- to postmatching.

Results

We present summary statistics of our study sample, drawn from the APCAPS third wave, in Table 1. Among the 2601 index children, 36 died before 2010 and the rest were invited to participate in survey. Of these, 53% (52% and 54% in the intervention and control groups, respectively) participated. Significantly more adults in the intervention group completed secondary and graduate education, and fewer adults were ever-married compared with the control group. Higher proportions of intervention-village adults belonged to the socially disadvantaged scheduled caste or tribe groups and lower wealth quintiles compared with the control group. There were no significant differences in age, sex, birth order, or parental educational levels between the 2 groups. Differences in the characteristics of children who participated in the follow-up surveys and those who did not were discussed in a previous study (28).

TABLE 1.

Summary statistics of intervention- and control-village study participants: APCAPS third wave (2010–2012)1

| Intervention-village | Control-village | Mean difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | adults | adults | (intervention – control) | P-difference |

| Completed secondary education | 0.83 ± 0.38 | 0.74 ± 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| Completed graduate education | 0.25 ± 0.43 | 0.16 ± 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| Ever-married by age 20–25 y | 0.29 ± 0.45 | 0.35 ± 0.48 | −0.06 | 0.02 |

| Employed or enrolled in higher education | 0.72 ± 0.45 | 0.65 ± 0.48 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Age, y | 22.93 ± 1.23 | 22.84 ± 1.21 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Birth order | 2.98 ± 1.47 | 2.97 ± 1.56 | 0.01 | 0.90 |

| Female sex | 0.38 ± 0.49 | 0.39 ± 0.49 | −0.01 | 0.73 |

| Scheduled caste/scheduled tribe | 0.43 ± 0.49 | 0.32 ± 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| Other backward classes | 0.48 ± 0.5 | 0.61 ± 0.49 | −0.13 | 0.00 |

| Non-Hindu household | 0.04 ± 0.19 | 0.08 ± 0.27 | −0.04 | 0.00 |

| Wealth quintile | ||||

| 1 | 0.18 ± 0.39 | 0.22 ± 0.41 | −0.04 | 0.10 |

| 2 | 0.23 ± 0.42 | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 3 | 0.21 ± 0.41 | 0.19 ± 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| 4 | 0.21 ± 0.41 | 0.19 ± 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| 5 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | 0.24 ± 0.43 | −0.07 | 0.00 |

| Literate father | 0.1 ± 0.31 | 0.11 ± 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.88 |

| Father's educational level | ||||

| Primary | 0.13 ± 0.34 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Secondary or above | 0.08 ± 0.27 | 0.09 ± 0.29 | −0.02 | 0.24 |

| Literate mother | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.15 ± 0.36 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| n | 715 | 644 | NA | NA |

1Values are mean proportions ± SD unless stated otherwise. All variables except for age and birth order are binary. The intervention group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in villages where the nutritional supplement was provided; the control group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in the control villages. APCAPS, Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study; NA, not applicable.

We summarize the probit regression and PSM estimates of the association between birth in an intervention village and adult outcomes in Table 2. Full regression results and PSM estimates are presented in Supplemental Tables 1–4. In our regression analysis, birth in an intervention village was associated with 9% (95% CI: 0.04, 0.14; P < 0.01) and 11% (95% CI: 0.06, 0.15; P < 0.01) increases in the completion rates of secondary and graduate-level education, respectively. There were no significant associations for marital status or employment-study outcomes. With the use of PSM, adults born in intervention villages were 9% (95% CI: 0.04, 0.14; P < 0.01) and 11% (95% CI: 0.06, 0.15; P < 0.01) more likely to complete secondary and graduate-level education, respectively, 6% (95% CI: −0.11, −0.01; P < 0.05) less likely to be ever-married by age 20–25 y, and 5% (95% CI: 0, 0.11; P < 0.05) more likely to be employed or enrolled in higher education than those in the control group.

TABLE 2.

Regression- and PSM-based estimated associations between birth in an intervention village and adult outcomes1

| Completed secondary | Completed graduate | Ever-married by | Employed/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| education | education | age 20–25 y | studying | |

| Regression-based estimated | ||||

| association with birth in an | ||||

| intervention village2 | ||||

| Full sample of men and women | 0.09*** (0.04, 0.14) | 0.11*** (0.06, 0.15) | −0.07* (−0.14, 0.00) | 0.08* (−0.01, 0.16) |

| Only men | 0.06** (0.00, 0.12) | 0.12*** (0.06, 0.18) | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01) | 0.08** (0.01, 0.14) |

| Only women | 0.16*** (0.07, 0.24) | 0.09** (0.01, 0.16) | −0.11* (−0.23, 0.01) | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.13) |

| PSM (Kernel matching)-based | ||||

| estimated association with birth | ||||

| in an intervention village3 | ||||

| Full sample of men and women | 0.09*** (0.04, 0.14) | 0.11*** (0.06, 0.15) | −0.06** (−0.11, −0.01) | 0.05** (0, 0.11) |

| Only men | 0.07** (0.02, 0.13) | 0.12*** (0.06, 0.18) | −0.05* (−0.09, 0) | 0.08** (0.03, 0.12) |

| Only women | 0.16*** (0.08, 0.25) | 0.09** (0.02, 0.16) | −0.11** (−0.21, −0.02) | 0.02 (−0.07, 0.11) |

1The intervention group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in villages where the nutritional supplement was provided; the control group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in the control villages. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01. PSM, propensity score matching.

2Values are estimated regression coefficients with 95% CIs. Only the coefficients of birth in an intervention village from each regression, and not covariates, are shown.

3Values are PSM-based estimators of the association between birth in an intervention village and outcome variable, along with 95% CIs.

In sex-specific regression analysis, men born in intervention villages had 6% (95% CI: 0, 0.12; P < 0.05) and 12% (95% CI: 0.06, 0.18; P < 0.01) higher secondary and graduate education completion rates, respectively, and were 8% (95% CI: −0.01, 0.14; P < 0.05) more likely to be employed or enrolled in higher education than men from control villages. In PSM analysis, intervention-group men were more likely to complete secondary and graduate education and were more likely to be employed or enrolled in higher education by 7% (95% CI: 0.02, 0.13; P < 0.05), 12% (95% CI: 0.06, 0.18; P < 0.01), and 8% (95% CI: 0.03, 0.12; P < 0.05), respectively, than control-group men.

In regression analysis, intervention-group women had 16% (95% CI: 0.07, 0.24; P < 0.01) and 9% (95% CI: 0.01, 0.16; P < 0.05) higher secondary and graduate education completion rates, respectively, compared with women from control villages. Similarly, in PSM analysis, they were 16% (95% CI: 0.08, 0.25; P < 0.01) and 9% (95% CI: 0.02, 0.16; P < 0.05) more likely to complete secondary and graduate education and were 7% less likely to be ever-married by age 20–25 y (95% CI: −0.21, −0.02; P < 0.05) than control-group women.

Our PSM results were robust to alternative matching algorithms, as shown in Supplemental Table 4. Adults born in intervention villages completed grade levels at significantly higher rates and were ever-married at significantly lower rates. The estimated associations for graduate education completion and employment-study rates were larger for men, whereas the associations for secondary education and ever-married rates by age 20–25 y were larger for women.

We present results from the tests of matching quality under various matching algorithms in PSM in Supplemental Table 5. The mean bias in covariates (i.e., the percentage difference in values between intervention and control groups) decreased substantially from 10.6% in the unmatched data to 1.8–2.7% in matched data, with maximum bias reduction under Kernel matching. The likelihood test estimator (χ2) of covariates changed from significant to nonsignificant, and the pseudo-R2 decreased by >90% from pre- to postmatching in all cases. The results for sex-specific analyses were very similar and therefore are not shown separately. These indicate that PSM successfully reduced systematic differences in the characteristics of intervention and control groups.

Discussion

By using regression and PSM analysis, we found that adults originally born in intervention villages during the Hyderabad Nutrition Trial had significantly higher rates of completion of secondary and graduate-level schooling, were less likely to be married by age 20–25 y, and were more likely to be employed or enrolled in higher education. In separate analysis by sex, we found secondary completion rates to be even higher among intervention-village women than in men. The negative association of nutrition with marriage rates by age 20–25 y was seen primarily among women, whereas the positive association with Employment-study rates was seen for men. Our findings are not sensitive to the choice of matching method.

Our findings contribute significantly both to the literature on the long-term non–health-related effects of early-life nutrition in the context of LMICs and the effectiveness of the ICDS program in India. The current research in LMICs is limited and heavily based on observational data (10). To the best of our knowledge, the INCAP studies in Guatemala are the only other sources of high-quality experimental evidence on early-life nutrition and adult health, educational, marital, and economic outcomes (13, 14, 23).

With the use of observational data, some studies have shown that Indian children who received supplemental nutrition from the ICDS program were taller and less likely to be underweight (43–46). Two other observational studies showed improved future school enrollment and attainment among children exposed to ICDS during early life (47, 48). By using experimental data from the APCAPS first wave (2003–2005), Kinra et al. (28) found that 13- to 18-y-old adolescents born in ICDS intervention villages were taller and had more favorable cardiovascular disease risk profiles than control-village children. In another study that used these data, we found that the intervention-village adolescents also had higher school enrollment and attainment rates, but there was no difference in academic test scores (16). In the current study, we found that the educational attainment benefits of ICDS nutrition continued well into adulthood of the study participants.

Our findings have important policy implications. In 2014, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) in bachelor's degree or equivalent in India was 24.3% (49). Although higher than GERs in neighboring countries such as Bangladesh (13%), Pakistan (10%), and Nepal (16%), it was lower than in other LMICs, such as Mexico (30%) and China (39%) (50). GERs among socioeconomically disadvantaged scheduled caste and scheduled tribe groups in India were 19.1% and 13.7%, respectively (49). There are no official estimates of graduation rates of tertiary education in India. However, according to the 2011 census, only 7.6% of the 20- to 29-y-old rural population and 6% of rural women of this age group had at least a college degree or equivalent (51).

ICDS nutrition can potentially increase the number of college graduates in India. In 2011, there were 73.8 million people in the 20- to 24-y-old age group in India, of whom 5.5 million had a college degree or equivalent (51). Our estimates suggest that exposure to daily ICDS nutrition during early life could increase the number of graduates to 8.7 million. Increases in secondary and college graduation rates, along with higher rates of employment or enrollment in higher education, may also be associated with large economic gains. It is estimated that each extra year of education at the secondary, higher secondary, and college or equivalent levels can increase wages by 11.4%, 12.2%, and 15.9%, respectively, in India (52).

The lower marriage rates by age 20–25 y in the intervention group may be associated with substantial health and demographic effects on women and children. A recent study linked a 1-y delay in marriage for women with a 2.2% reduction in home birth rates, a 5.1% increase in breastfeeding rates, and a 4.6% increase in full vaccination of children in India (53). The children of women who delay marriage also had higher weight-for-height anthropometry scores, school enrollment rates, and cognitive test scores (53). Another study showed that Indian women who married before the age of 18 y had lower contraceptive usage rates, higher fertility, lower birth spacing, and more unwanted pregnancies (54). An INCAP study found that improved nutrition—measured as a 1-SD increase in the height-for-age z score of women—was associated with a 0.8-y delay in first marriage, 0.6 fewer pregnancies, and 0.4 fewer child births (12).

Despite potentially large health, educational, and economic benefits, the effectiveness of ICDS at the national level has been frequently questioned (2, 28, 43, 44, 48). Although the ICDS program is intended to be universal, there remain large variations across states in per capita availability of centers and quality and coverage of services. In 2014, there was 1 center that provided nutrition to 193 children in Bihar and to 101 children in Uttar Pradesh compared with a national average of 68 children/center (55). A nationally representative household survey in 2013–2014 found that only 43.4% and 32.4% of Anganwadi centers in India had toilets and electricity connections, respectively (56). In addition, only 42% of mothers with children aged <6 mo reported receiving supplementary food from ICDS. The rate varied from 3% and 3.4% in Nagaland and Delhi to 76.5% and 81.5% in Odisha and Chhattisgarh, respectively (56). Another 2013 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India pointed out irregularities such as budget overruns and failure to provide universal ICDS coverage in several states (57).

There are potential limitations to our analysis. The original trial collected information on the offering of the nutritional supplementation to, and not consumption by, the participants. Any unknown intrahousehold redistribution of the supplement could have weakened its estimated association with future outcomes.

Before the trial, the intervention- and control-village residents had similar access to public health programs, such as anemia control in pregnancy and immunization. The utilization of these services in intervention villages might have increased after the introduction of ICDS nutrition (16, 28), resulting in possible confounding effects on adult outcomes. However, the other components of ICDS may also amplify the potential effect of nutrition by improving the overall health and nutritional status of children (16, 28).

Children born during 1987–1990 in control villages received the nutritional supplement when they were 3–6 y old (i.e., after the trial ended). This might weaken the estimated associations of future outcomes of the intervention children when compared with the control group. However, previous studies tend to show that nutrition during the first 2–3 y of life have the strongest effect on later life outcomes (21, 58). In conclusion, exposure to nutritional supplementation in utero or during the first 3 y of life was associated with improved adult educational and employment outcomes and lower marriage rates in India.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—SK: collected the data; AN: conducted the analysis and wrote the first version of the manuscript; JRB, SK, and RL: interpreted the findings and edited the manuscript; AN, RL, and JRB: were responsible for the final contents; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by Grand Challenges Canada through the Saving Brains project (grant 0072-03).

The Hyderabad Nutrition Trial was funded by the United States Assistance for International Development and the Indian Council for Medical Research. The 2010-2012 follow-up survey was funded by Wellcome Trust Strategic Award 084774. The National Institute of Nutrition (Directors), Indian Council for Medical Research, provided support in kind to the follow-up surveys through free or subsidized access to facilities and materials.

Author disclosures: AN, JRB, SK, and RL, no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental Tables 1–5 are available from the “Supplementary Data” link in the onlineposting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn/.

Abbreviations used:

- APCAPS

Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study

- GER

gross enrollment ratio

- ICDS

Integrated Child Development Services

- INCAP

Institute of Nutrition for Central America and Panama

- LMIC

low- and middle-income country

- PSM

propensity score matching

- under-5

<5 y of age

Footnotes

Values are mean ± SD proportions unless stated otherwise. All variables except for age and birth order are binary. The intervention group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in villages where the nutritional supplement was provided; the control group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in the control villages. APCAPS, Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study.

The intervention group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in villages where the nutritional supplement was provided; the control group includes adults born during 1987–1990 in the control villages. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01. PSM, propensity score matching.

2Values are estimated regression coefficients with 95% CIs. Only the coefficients of birth in an intervention village from each regression, and not covariates, are shown.

Values are PSM-based estimators of the association between birth in an intervention village and outcome variable, along with 95% CIs.

References

- 1. Raykar N, Majumder M, Laxminarayan R, Menon P. India Health Report: nutrition 2015. New Delhi (India): Public Foundation of India; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gragnolati M, Bredenkamp C, Shekar M, Das Gupta M, Lee Y-K. India's undernourished children: a call for reform and action [Internet]. Washington (DC): The World Bank; 2006. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.com/handle/10986/13644. [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Food Policy Research Institute. Global Nutrition Report 2014: actions and accountability to accelerate the world's progress on nutrition. Washington (DC); International Food Policy Research Institute; 2014. Report No.: 9780896295643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. UNICEF; WHO; World Bank Group. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2016 edition [Internet]. Washington (DC): Data and Analytics Section of the Division of Data, Research, and Policy, UNICEF New York; the Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, WHO Geneva; and the Development Data Group of the World Bank; 2016. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/UNICEF-Joint-Malnutrition-brochure.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Institute for Population Sciences. Report of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3): 2005–2006. Mumbai (India): International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adair LS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Stein AD, Martorell R, Ramirez-Zea M, Sachdev HS, Dahly DL, Bas I, Norris SA, et al. Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with adult health and human capital in countries of low and middle income: findings from five birth cohort studies. Lancet 2013;382:525–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alderman H, Hoddinott J, Kinsey B. Long term consequences of early childhood malnutrition. Oxf Econ Pap 2006;58:450–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Almond D, Currie J. Killing me softly: the fetal origins hypothesis. J Econ Perspect 2011;25:153–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Behrman JR, Calderon MC, Preston SH, Hoddinott J, Martorell R, Stein AD. Nutritional supplementation in girls influences the growth of their children: prospective study in Guatemala. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Currie J, Vogl T. Early-life health and adult circumstance in developing countries. Ann Rev Econ 2013;5:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoddinott J, Alderman H, Behrman JR, Haddad L, Horton S. The economic rationale for investing in stunting reduction. Matern Child Nutr 2013;9(Suppl 2):69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoddinott J, Behrman JR, Maluccio JA, Melgar P, Quisumbing AR, Ramirez-Zea M, Stein AD, Yount KM, Martorell R. Adult consequences of growth failure in early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1170–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoddinott J, Maluccio JA, Behrman JR, Flores R, Martorell R. Effect of a nutrition intervention during early childhood on economic productivity in Guatemalan adults. Lancet 2008;371:411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maluccio J, Hoddinott J, Behrman J, Quisumbing A, Martorell R, Stein AD. The impact of nutrition during early childhood on education among Guatemalan adults. Econ J 2009;119:734–63. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martorell R, Horta BL, Adair LS, Stein AD, Richter L, Fall CHD, Bhargava SK, Biswas SKD, Perez L, Barros FC, et al. Weight gain in the first two years of life is an important predictor of schooling outcomes in pooled analyses from five birth cohorts from low- and middle-income countries. J Nutr 2010;140:348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nandi A, Ashok A, Kinra S, Behrman JR, Laxminarayan R. Early childhood nutrition is positively associated with adolescent educational outcomes: evidence from the Andhra Pradesh Child and Parents Study (APCAPS). J Nutr 2016;146:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nandi A, Behrman JR, Bhalotra S, Deolalikar AB, Laxminarayan R. Human capital and productivity benefits of early childhood nutritional interventions. In: Disease control priorities. 3rd ed., Vol. 8 Child & adolescent development [Internet] Washington (DC): World Bank Publications; 2017. Available from: http://dcp-3.org/volume/8/child-adolescent-development. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stein AD, Barros FC, Bhargava SK, Hao W, Horta BL, Lee N, Kuzawa CW, Martorell R, Ramji S, Stein A, et al. Birth status, child growth, and adult outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. J Pediatr 2013;163:1740–1746, e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stein AD, Wang M, Martorell R, Norris SA, Adair LS, Bas I, Sachdev HS, Bhargava SK, Fall CHD, Gigante DP, et al. Growth patterns in early childhood and final attained stature: data from five birth cohorts from low- and middle-income countries. Am J Hum Biol 2010;22:353–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, Sachdev HS. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371:340–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fink G, Peet E, Danaei G, Andrews K, McCoy DC, Sudfeld CR, Smith Fawzi MC, Ezzati M, Fawzi WW. Schooling and wage income losses due to early-childhood growth faltering in developing countries: national, regional, and global estimates. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104:104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martorell R, Melgar P, Maluccio JA, Stein AD, Rivera JA. The nutrition intervention improved adult human capital and economic productivity. J Nutr 2010;140:411–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Victora C, Horta BL, Quevedo L, Pinheiro RT, Gigante DP, Gonçalves H, Barros FC. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Field E, Robles O, Torero M. Iodine deficiency and schooling attainment in Tanzania. Am Econ J 2009;1:140–69. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glewwe P, Jacoby HG, King EM. Early childhood nutrition and academic achievement: a longitudinal analysis. J Public Econ 2001;81:345–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Majid MF. The persistent effects of in utero nutrition shocks over the life cycle: evidence from Ramadan fasting. J Dev Econ 2015;117:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kinra S, Rameshwar Sarma KV, Ghafoorunissa, Mendu VVR, Ravikumar R, Mohan V, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR, Davey Smith G, et al. Effect of integration of supplemental nutrition with public health programmes in pregnancy and early childhood on cardiovascular risk in rural Indian adolescents: long term follow-up of Hyderabad Nutrition Trial. BMJ 2008;337:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kinra S, Sarma KVR, Hards M, Smith GD, Ben-Shlomo Y. Is relative leg length a biomarker of childhood nutrition? Long-term follow-up of the Hyderabad Nutrition Trial. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1022–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. APCAPS. Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study: summary of follow-ups and participants [Internet]. 2013[cited 2017 Mar 29]. Available from: http://apcaps.lshtm.ac.uk/available-data/participants/.

- 31. Kinra S, Radha Krishna K, Kuper H, Rameshwar Sarma K, Prabhakaran P, Gupta V, Walia GK, Bhogadi S, Kulkarni B, Kumar A, et al. Cohort profile: Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study (APCAPS). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1417–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Andhra Pradesh Children and Parents Study: people [Internet]. 2017[cited 2017 Sep 19]. Available from: http://apcaps.lshtm.ac.uk/people/.

- 33. Pollitt E, Gorman KS, Engle PL, Martorell R, Rivera J. Early supplementary feeding and cognition: effects over two decades. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 1993;58:1–99; discussion 111–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or-tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001;38:115–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 1984;79:516–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Todd PE. Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev Econ Stud 1997;64:605–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing [Internet]. 2003. Available from: http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

- 38. Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat 2002;84:151–61. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implemen-tation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv 2008;22:31–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abadie A, Imbens GW. Large sample properties of matching estimators for average treatment effects. Econometrica 2006;74:235–67. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sianesi B. An evaluation of the Swedish system of active labor market programs in the 1990s. Rev Econ Stat 2004;86:133–55. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jain M. India's struggle against malnutrition: is the ICDS program the answer. World Dev 2015;67:72–89. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lokshin M, Das Gupta M, Gragnolati M, Ivaschenko O. Improving child nutrition? The Integrated Child Development Services in India. Dev Change 2005;36:613–40. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kandpal E. Beyond average treatment effects: distribution of child nutrition outcomes and program placement in India's ICDS. World Dev 2011;39:1410–21. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deolalikar AB. Child Malnutrition: Attaining the Millennium Development Goals in India: Reducing Infant Mortality, Child Malnutrition, Gender Disparities and Hunger-Poverty and Increasing School Enrollment and Completion. New Delhi (India): World Bank, South Asia Regional Office; Human Development Unit: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hazarika G, Viren V. The effect of early childhood developmental program attendance on future school enrollment in rural North India. Econ Educ Rev 2013;34:146–61. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nandi A, Behrman J, Laxminarayan R. The Impact of Childhood Nutrition on Schooling Attainment of Non-Migrant Adults in India: Evidence from the ICDS Program [Internet]. Rochester (NY): Social Science Research Network; 2016. Report No.: 2706964. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2706964. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ministry of Human Resource Development. All India Survey on Higher Education (2014-15). New Delhi (India): Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of Higher Education, Government of India; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50. The World Bank. World DataBank: World Development Indicators [Internet]. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2017. [cited 2017 November 17] Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Census of India. Census 2011: educational level graduate and above by sex for population age 15 and above [Internet]. 2011[cited 2017 Apr 14]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-series/C08A.html.

- 52. Agrawal T. Returns to education in India: some recent evidence. J Quant Econ 2012;10:131–51. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chari AV, Heath R, Maertens A, Fatima F. The causal effect of maternal age at marriage on child wellbeing: evidence from India. J Dev Econ 2017;127:42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: a cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet 2009;373:1883–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Centre for Policy Research. Budget briefs: ICDS 2015–2016. New Delhi (India): Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ministry of Women & Child Development. Rapid Survey on Children 2013–2014 National Report. New Delhi (India): Ministry of Women & Child Development, Government of India; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Performance Audit of Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme. New Delhi (India): Comptroller and Auditor General of India, Government of India; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Black R, Alderman H, Bhutta ZA, Gillespie S, Haddad L, Horton S, Lartey A, Mannar V, Ruel M, Victora C, et al. Maternal and child nutrition: building momentum for impact. Lancet 2013;382:372–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.