Abstract

In many caries-promoting Streptococcus species, glucosyltransferases (Gtfs) are recognized as key enzymes contributing to the modification of biofilm structures, disruption of homeostasis of healthy microbiota community and induction of caries development. It is therefore of great interest to investigate how Gtf genes have evolved in Streptococcus. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive survey of Gtf genes among 872 streptococci genomes of 37 species and identified Gtf genes from 364 genomes of 18 species. To clarify the relationships of these Gtf genes, 45 representative sequences were used for phylogenic analysis, which revealed two clear clades. Clade I included 12 Gtf genes from nine caries-promoting species of the Mutans and Downei groups, which produce enzymes known to synthesize sticky, water-insoluble glucans (WIG) that are critical for modifying biofilm structures. Clade II primarily contained Gtf genes responsible for synthesizing water-soluble glucans (WSG) from all 18 species, and this clade further diverged into three subclades (IIA, IIB, and IIC). An analysis of 16 pairs of duplicated Gtf genes revealed high divergence levels at the C-terminal repeat regions, with ratios of the non-synonymous substitution rate (dN) to synonymous substitution rate (dS) ranging from 0.60 to 1.03, indicating an overall relaxed constraint in this region. However, among the clade I Gtf genes, some individual repeat units possessed strong functional constraints by the same criterion. Structural variations in the repeat regions were also observed, with detection of deletions or recent duplications of individual repeat units. Overall, by establishing an updated phylogeny and further elucidating their evolutionary patterns, this work enabled us to gain a greater understanding of the origination and divergence of Gtf genes in Streptococcus.

Keywords: Streptococcus, glucosyltransferase gene (Gtf), evolution, duplication, selection

Introduction

The bacterial genus Streptococcus comprises many species living in human or animal oral cavities, which are collectively called oral streptococci (Coykendall, 1989; Whiley and Beighton, 1998; Facklam, 2002; Kohler, 2007). According to recent phylogenomic studies (Shao et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2014; Richards et al., 2014), the genus Streptococcus includes at many as eight monophyletic groups, and the oral streptococci are mainly distributed in six of these groups: Mitis, Sanguinis, Anginosus, Mutans, Salivarius, and Downei, each of which is named with a representative species. Among these, the Mutans and Downei groups are known to contain many caries-promoting species, which are normally minor in oral microbiome under healthy condition but can grow to markedly higher proportions under disease condition (Loesche, 1986; Whiley and Beighton, 1998; Balakrishnan et al., 2000; Richards et al., 2014; Kilian et al., 2016; Sanz et al., 2017; Manji et al., 2018; Philip et al., 2018; Twetman, 2018).

As the representative species of the Mutans group, Streptococcus mutans is widely recognized as a caries-promoting species in human oral cavity (Cornejo et al., 2013; Lemos et al., 2013). The involvement of S. mutans in caries development includes three phases. First, the bacteria can efficiently adhere to the surfaces of teeth and promote the formation of an extracellular, multi-dimensional structure known as a dental biofilm. Under health condition, a wide diversity of oral microbes dwells in the dental biofilm and the number of caries-promoting bacteria like S. mutans is maintained at low level. Second, when frequently exposed to fermentable carbohydrates in a diet, a large quantity of acidic products would be generated and released into the extracellular matrix and bacteria like S. mutans would be favored by lower pH environment in the biofilm and the growth of other oral bacteria would be inhibited. Third, once a dominant status of acid-producing and acid-tolerating bacteria like S. mutans is established within the biofilm, the acidic products would accumulate and promote the demineralization of tooth enamel, and eventually form dental caries (Lemos et al., 2013; Mclean, 2014; Guo et al., 2015; Kilian et al., 2016; Manji et al., 2018). In addition to S. mutans, another caries-promoting species in human is S. sobrinus of the Downei group, which is more frequently isolated from teenagers and children (Okada et al., 2005, 2012). Many other caries-promoting species in the Mutans and Downei groups are instead associated with various dentate mammals. These includes S. macacae and S. downei recovered from dental plaques of monkeys (Beighton et al., 1984; Whiley et al., 1988), S. troglodytae from oral cavities of chimpanzees (Okamoto et al., 2013), S. ratti and S. criceti from caries lesions of rodents (Coykendall, 1989), S. dentirousetti from oral cavities of fruit bats (Takada and Hirasawa, 2008), S. orisuis from the mouths of pigs (Takada and Hirasawa, 2007), and S. devriesei and S. orisasini isolated from horse and donkey teeth, respectively (Collins et al., 2004; Takada et al., 2013).

In the Salivarius group, animal experiments have shown that some strains of S. salivarius are capable of promoting high levels of caries, while another species, S. vestibularis, seems to lack this ability (Drucker et al., 1984; Willcox et al., 1991). The oral Streptococci in the Mitis, Sanguinis, and Anginosus groups are usually not regarded as caries-promoting species; rather, many of these species cause severe human diseases if they gain entrance to sites that are usually sterile (Coykendall, 1989; Whiley and Beighton, 1998; Facklam, 2002; Kohler, 2007). For example, S. pneumoniae, which normally reside in the human upper respiratory tract, is a leading cause of life-threatening diseases, such as sepsis, meningitis, and pneumonia (O’Brien and Nohynek, 2003).

Studies of several caries-promoting Streptococcus species have identified glucosyltransferases (Gtfs, also known as dextransucrases, EC 2.4.1.5) as critical enzymes contributing to caries development (Mukasa et al., 1985; Yamashita et al., 1993; Colby et al., 1999; Bowen and Koo, 2011; Koo et al., 2013; Krzysciak et al., 2014). Belonging to the glycoside hydrolase family 70 (GH70), Gtf enzymes and their close homologs are found in several lactic acid bacteria genera, including Streptococcus, Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Weissella (Leemhuis et al., 2013). Having a conserved, central catalytic GH70 domain (for sucrose binding and splitting) and a variable, C-terminal repeat region (for potential glucan binding), these enzymes are able to synthesize a variety of α-glucans, such as dextran, mutan, and alternan from sucrose (Monchois et al., 1999). Early studies of S. mutans strain GS-5 have identified three different Gtf enzymes, GtfB, GtfC, and GtfD (Shiroza et al., 1987; Ueda et al., 1988; Honda et al., 1990). Recent studies have shown that these enzymes play differential roles in modifying biofilm structures toward caries development (Bowen and Koo, 2011; Krzysciak et al., 2014). GtfB, which mainly synthesizes sticky, water-insoluble glucans (WIG) rich in α1, 3-linkages, can adsorb onto the surfaces of S. mutans as well as other oral bacteria and promote the aggregation of bacterial cells in biofilm. Instead, GtfC exhibits a high affinity to tooth enamel pellicles and greatly helps bacteria adhere onto tooth surfaces by synthesizing a mixture of WIG and water-soluble glucans (WSG, rich in α1, 6-linkages). GtfB and GtfC are also involved in concentrating protons around S. mutans and pre-conditioning of bacteria for the acidic environments in biofilms (Guo et al., 2015). Predominantly synthesizing soluble glucans, GtfD is known to serve as primers for GtfB to enhance the overall synthesis efficiency of glucans (Bowen and Koo, 2011; Krzysciak et al., 2014). Overall, the biofilm matrix rich in WIG is more porous (Dibdin and Shellis, 1988), and favors carbohydrate diffusion through the matrix, allowing even the deepest bacteria in the biofilm (near tooth surface) to ferment carbohydrate and release acids.

Like S. mutans, other caries-promoting Streptococci would also rely on certain WIG-synthesizing Gtfs to influence the biofilm structures, creating an environment favoring caries development. In species that are not regarded as caries-promoting, such as S. gordonii, S. oralis, and S. sanguinis, only one type of Gtf enzyme synthesizing soluble glucans could be found, with their genes designated GtfG, GtfR, and GtfP, respectively (Vickerman et al., 1997; Fujiwara et al., 2000; Vacca Smith et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2007). However, multiple types of Gtf enzymes synthesizing both WSG and WIG have been isolated from caries-promoting species. Specifically, two Downei group species, S. downei and S. sobrinus, have been reported to produce four different types of Gtf enzymes encoded by genes GtfI, GtfS, GtfT, and GtfU (Ferretti et al., 1987; Yamashita et al., 1989; Gilmore et al., 1990; Abo et al., 1991; Hanada et al., 1993, 2002; Colby et al., 1999). Two of these genes, GtfS and GtfT, were also found arranged in tandem on chromosomes in S. criceti and S. dentirousetti (Inoue et al., 2000; Shinozaki-Kuwahara et al., 2013). Moreover, four different Gtf genes, namely GtfJ, GtfK, GtfL, and GtfM, were identified in S. salivarius ATCC 25975 (Giffard et al., 1991, 1993; Simpson et al., 1995b). Examining these Gtf enzymes revealed that, similar to S. mutans GtfB and GtfC, S. downei GtfI, S. sobrinus GtfI, and S. salivarius GtfJ and GtfL all synthesize WIG, while other Gtfs, similar to S. mutans GtfD, mainly synthesize WSG (Russell et al., 1987, 1990; Abo et al., 1991; Hanada et al., 1991; Simpson et al., 1995a; Nanbu et al., 2000).

Wondering whether Gtf enzymes synthesizing insoluble glucans in different Streptococcus species would be closely related, Giffard et al. (1993) and Simpson et al. (1995b) reconstruct distance trees using 8 and 12 Streptococcus Gtf genes, respectively. Surprisingly, they found that although S. salivarius GtfJ and GtfL are responsible for synthesizing insoluble glucans, they are not actually closely related to GtfB and GtfC of S. mutans and GtfIs of Downei group species. Later, Hoshino et al. (2012) investigated Streptococcus Gtfs as well as their homologs in Leuconostoc and Lactobacillus and found that all Streptococcus Gtfs share a common ancestor. They also proposed that the ancestral Streptococcus Gtf gene was likely acquired from a lactic acid bacterium via horizontal gene transfer (HGT). As more Gtf genes from various Streptococcus species became available, Argimon et al. (2013) further reported a phylogeny covering 39 Gtf sequences from 16 Streptococcus species. The results revealed for the first time that Streptococcus Gtfs had diverged into two major clades, with one comprising only Gtfs synthesizing WIG and the other including mainly Gtfs synthesizing WSG. The S. salivarius GtfJ and GtfL originated within the WSG clade, and it is believed that their abilities to synthesize WIG were acquired secondarily, probably because of selective divergence after gene duplication (Argimon et al., 2013). The Gtf gene phylogenies reported by both Hoshino et al. (2012) and Argimon et al. (2013) are based on the conserved GH70 domain sequences. However, on one hand, the range of GH70 domain is often not clearly defined among these studies. On the other hand, recombination events leading to incorrect topology likely occur on conserved GH70 domain region. So far, it remains largely unexplored whether the C-terminal repeat regions of Gtf genes can be included for phylogenetic inferences.

Taken together, previous studies have shown a general picture of the evolutionary history of Gtf genes in Streptococcus, but many aspects are still vague. For example, it is often unclear how many different types of Gtf genes are present in a given Streptococcus species. In a recent genome comparison study (Conrads et al., 2014), up to seven different Gtf genes (some only represent partial genes) were reported in S. sobrinus DSM 20742 compared to three in S. mutans UA159 (Ajdić et al., 2002). Due to increased availability of genome sequences of Streptococcus species/strains in recent years, it is now feasible to define Gtf gene numbers accurately among different Streptococcus species. Moreover, although previous phylogenetic studies have identified two major clades of Gtf genes (one WIG clade and the other WSG clade), further subgrouping of Gtf genes within clades and their relationships among various Streptococcus groups have not been elucidated well. Additionally, the presence of multiple Gtf genes in certain Streptococcus species suggests that many gene duplication events have occurred; however, the divergence patterns of duplicated Gtf genes, especially at variable C-terminal repeat regions, have not been systematically investigated. To gain a better understanding of Gtf gene evolution in Streptococcus, we surveyed a total of 872 Streptococci genomes covering 37 species (both cariogenic and non-cariogenic) to detect Gtf genes. We then used 45 representative sequences from 18 species or 317 sequences from 157 strains to establish robust Gtf gene phylogenies, which revealed more elaborate evolutionary relationships of Gtf genes from various streptococcus groups or species. More importantly, after speciation events or duplication events, the divergence patterns of Gtf genes, especially at the C-terminal repeat regions, were thoroughly examined.

Materials and Methods

Streptococcus Species Surveyed in This Study

Three recent phylogenomic studies have established a rather stable Streptococcus phylogeny, in which Streptococcus species were assigned into as many as eight monophyletic groups (Shao et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2014; Richards et al., 2014). Among these, the Anginosus and the newly proposed Sanguinis groups are sisters to each other, and they together with the Mitis group form a monophyletic clade (the ASM clade). The remaining five groups form the second monophyletic clade (SDMBP clade), with the Salivarius group sister to the new Downei group and the Bovis group sister to the Pyogenic group. The relationships among the Salivarius-Downei groups, the Mutans group, and the Bovis-Pyogenic groups have not yet been resolved, although one study supported a closer relationship between the Mutans group and the Bovis-Pyogenic groups (Gao et al., 2014). In addition, the S. suis species lies at an independent position between the two clades.

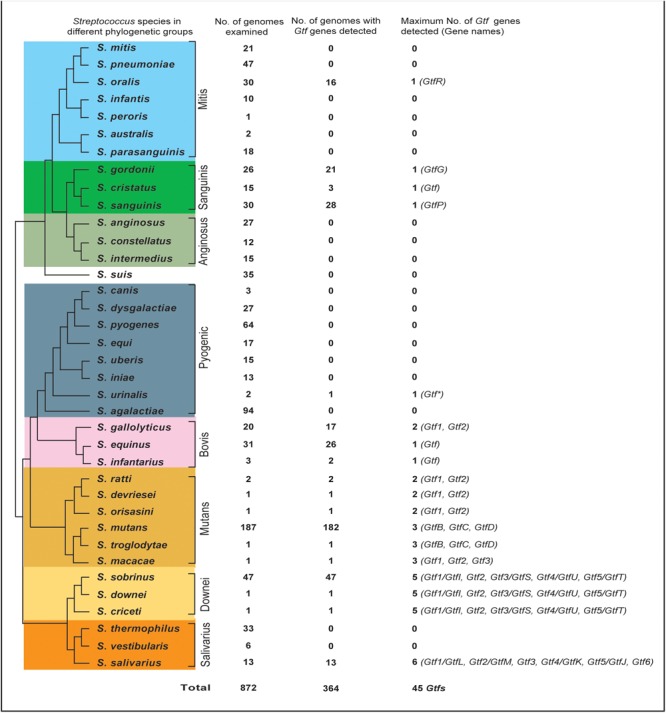

According to the phylogeny, a total of 37 Streptococcus species were selected for this study (Figure 1). These include seven species from the Mitis group (S. mitis, S. pneumoniae, S. oralis, S. infantis, S. peroris, S. australis, and S. parasanguinis), three species from the Sanguinis group (S. gordonii, S. cristatus, and S. sanguinis), three species from the Anginosus group (S. anginosus, S. constellatus, and S. intermedius), the independent species S. suis, eight species from the Pyogenic group (S. canis, S. dysgalactiae, S. pyogenes, S. equi, S. uberis, S. iniae, S. urinalis, and S. agalactiae), three species from the Bovis group (S. gallolyticus, S. equinus, and S. infantarius), six species from the Mutans group (S. ratti, S. devriesei, S. orisasini, S. mutans, S. troglodytae, and S. macacae), three species from the Downei group (S. criceti, S. downei, and S. sobrinus), and three species from the Salivarius group (S. thermophilus, S. vestibularis, and S. salivarius).

FIGURE 1.

The distribution of Glucosyltransferase (Gtf) genes among 37 surveyed Streptococcus species. The phylogenetic relationships of streptococci were drawn based on three recent phylogenomic studies (Shao et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2014; Richards et al., 2014). A total of 872 genomes for the 37 species were examined, with 1 to 6 types of Gtf genes detected in 364 genomes of 18 species.

Surveying Gtf Genes Among Streptococci Species

The genome sequence(s) available on the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) Microbial Genomes resource site1 on January 1, 2018 were surveyed for each of the 37 Streptococcus species. When there were many genome sequences available for a given species, those with better assembly levels were always examined first since these genomes have a higher chance to have a complete set of Gtf genes annotated. Overall, a total of 872 genomes were surveyed, and their detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table S1. For each genome, all of its protein sequences were downloaded and searched via BLASTP using the S. mutans UA159 Gtfs (NC_004350, SMU_910; SMU_1004; SMU_1005) as query sequences. The positive hits with E-values smaller than 1e-6 and query coverage higher than 50% were taken as potential Gtfs, which were further subjected to domain analyses on the NCBI Conserved Domain search site2. Only those possessing both the central GH70 domain and also the C-terminal glucan-binding domain (GBD) repeat regions were considered authentic Gtf enzymes for further analysis (Supplementary Table S1). In each species, the maximum number of Gtf genes detected from a representative strain was determined and these genes were named numerically (as Gtf1, Gtf2, Gtf3…). For genes detected in other strains of the same species, the detected genes were named accordingly by performing sequence comparisons and/or phylogenetic analyses (see next section). If a specific name was previously assigned to a Gtf gene in the literature, then the name was listed as well.

Reconstructing the Phylogenies of Streptococcus Gtf Genes

Five outgroup sequences were selected to represent the anciently diverged lineages that were homologous to Streptococcus Gtf genes in this study: Weissella confusa strain VTT E-90392 dextransucrase gene (KJ173611, 4272bp), Leuconostoc mesenteroides dextransucrase gene DsrD (AY017384, 4584bp), Lactobacillus parabuchneri strain 33 glucansucrase gene (AY697432, 4686bp), Lactobacillus sucicola JCM 15457 GtfG gene (GAJ25773, 4752bp), and Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides strain BD3749 Gtf gene (KU306934, 4440bp).

To clarify the relationships of the identified Streptococcus Gtf genes, one representative strain for each species was selected first (Supplementary Table S1), and a data matrix consisting of 45 different Gtf genes from 18 Streptococcus species was compiled. Using the ClustalW and Muscle algorithms implemented in MEGA 5.0 (Tamura et al., 2011), these genes were aligned with the five outgroup genes using their protein sequences as a guide. By examining the obtained alignment in terms of homology, two major variable regions were identified. The first variable region (sites 139–966) is located between the N-terminal signal peptide region (SP) and a short conserved region (SCR) upstream of the central catalytic GH70 domain, and the second variable region (sites 4698–6897 bp) is at the C-terminal repeat region (for details, see next section and Supplementary Table S2). Since variable regions unlikely represent authentically homologous sites, these two regions were removed. The remaining alignment (∼3.9 kb) includes four rather conserved regions: the SP region, the SCR region, the entire GH70 domain, and the first two glucan-binding domain repeat units at the C-terminal repeat region (Supplementary Table S2). The 3.9 kb alignment was then used to reconstruct a Maximum-Likelihood (ML) tree in MEGA 5.0 by choosing the most appropriate nucleotide substitution model (GTR+I+ Γ), with 100 bootstrap replicates performed to test the robustness of internal branches (Tamura et al., 2011). Major clades or subclades were identified by examining the obtained phylogeny. Meanwhile, to explore the contribution of different regions to the phylogenetic reconstruction, two additional phylogenies were reconstructed by using either a 3.1 kb alignment covering the SP, SCR, and GH70 domain regions or a 2.6 kb alignment covering only the GH70 domain. Finally, to double-examine the reconstructed relationships and also to avoid any possible shortcomings incurred by using only one representative strain for a species, the sequence data from multiple strains was used to reconstruct the Gtf gene phylogenies for each major clade or subclade individually. In a total, 317 sequences from 157 strains of the 18 species were used.

Analysis of the Divergence Patterns of Streptococcus Gtf Genes

For all 45 Streptococcus Gtf enzymes as well as the 5 outgroup proteins, the positions for various domains were carefully determined through the NCBI conserved domain searches and manual examination of the alignment. These domains included the N-terminal SP region (∼40 aa), a SCR region (∼100 aa) upstream of the GH70 domain, the conserved catalytic GH70 domain (∼800 aa), and the C-terminal repeat region (∼220–500 aa). Within the repeat regions, various numbers of Glucan-binding domain (GBD, TIGR04035, ∼65aa) repeat units were further determined. Since these GBD units all start with a conserved A repeat sequence (∼33 aa, Gilmore et al., 1990; Shah et al., 2004), the positions for all A repeating units were determined for each Gtf enzyme.

To explore the divergence patterns of Gtf genes after duplication events, sixteen pairs of Gtf genes were analyzed. For each pair, the genetic distances for the full-length gene (Dgene), the conserved GH70 domain (DGH70), and the C-terminal repeat regions (Drepeat region) were calculated in MEGA 5.0 (Tamura et al., 2011) by selecting the Tamura-Nei nucleotide substitution model and pairwise deletion. To also examine the selection pressures acting on the GH70 domain and the C-terminal repeat regions, the ratios of the non-synonymous substitution rate (Dn) to synonymous substitution rate (Ds) were calculated with the modified Nei-Gojobori method (Proportion) for both regions.

To explore the evolutionary patterns among closely related species, we focused on 12 Gtf genes in clade I and divided these into four groups, with each group having orthologous Gtf genes from three closely related species. In each group, the protein sequence identities and the dN/dS ratios were calculated for GH70 domain and A repeat units. The protein sequence identity levels among multiple A repeat units in each enzyme were also examined.

Results

The Distribution of Gtf Genes Among Streptococcus Species in Different Groups

To clearly define the Gtf gene numbers among different Streptococcus species, a total of 872 genomes covering 37 streptococcus species were surveyed (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). In the Mitis group, Gtf genes were not detected in six of the seven surveyed species, including 21 S. mitis genomes, 47 S. pneumoniae genomes, 10 S. infantis genomes, one S. peroris genome, two S. australis genomes, and 18 S. parasanguinis genomes (Figure 1). Since multiple completely assembled genomes were examined for species S. mitis, S. pneumoniae, and S. parasanguinis (Supplementary Table S1), it is safe to conclude that the Gtf gene is absent from these species. In S. oralis, one type of Gtf gene, namely GtfR, was detected in 16 out of 30 examined genomes (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). In the Sanguinis group, Gtf genes were detected from 21 out of 26 S. gordonii genomes, three out of 15 S. cristatus genomes and 28 out of 30 S. sanguinis genomes (Figure 1). The high detection rates of Gtf genes in species S. gordonii (81%) and S. sanguinis (93%) justify the presence of Gtf gene in both species, but the detection rate (20%) in S. cristatus is rather low. Interestingly, in a completely sequenced genome of S. cristatus strain AS 1.3089 (NC_021175), no Gtf gene was found (Supplementary Table S1). In the Anginosus group, a total of 27, 12, and 15 genomes were examined for S. anginosus, S. constellatus, and S. intermedius, respectively, but the Gtf gene was not detected (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Similarly, the Gtf gene was absent in 35 genomes of the independent species, S. suis.

Among a total of 235 genomes examined for eight species of the Pyogenic group, only one short Gtf gene was detected in the S. urinalis strain 2285-97 genome (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Since many completely sequenced genomes were examined for S. dysgalactiae, S. pyogenes, S. equi, S. uberis, S. iniae, and S. agalactiae, the absence of the Gtf gene can be justified for these species. However, this was not the case for the Bovis group. Among the three surveyed species, Gtf genes were detected in 17 out of 20 S. gallolyticus genomes, 26 out of 31 S. equinus genomes, and 2 out of 3 S. infantarius genomes (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Two different types of the Gtf genes were seen in S. gallolyticus.

In the Mutans groups, six species of two subgroups were surveyed. Interestingly, three species in the first subgroup, S. ratti, S. devrieseii, and S. orisasini, all possessed a maximum of two different types of Gtf genes, while three species in the other subgroup, S. mutans, S. troglodytae, and S. macacae, all contained a maximum of three types of Gtf genes (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). In the Downei group, 49 genomes representing three species, S. criceti, S. downei, and S. sobrinus, were examined and a maximum of five types of Gtf genes were detected from each species. Finally, in the Salivarius group, no Gtf gene was found from 33 S. thermophilus genomes and six S. vestibularis genomes. However, among 13 S. salivarius genomes examined, up to six types of Gtf genes were identified (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Overall, our survey identified 45 types of Gtf genes from 18 out of 37 investigated Streptococcus species (Figure 1). More than half of the surveyed species contained no Gtf gene, and these species were distributed in the Mitis, Anginosus, Pyogenic, and Salivarius groups. Seven species, including S. oralis of the Mitis groups, three species of the Sanguinis group, S. urinalis of the Pyogenic group, and two species of the Bovis group, possessed only one Gtf gene. The other 11 species, including S. gallolyticus of the Bovis group, S. salivarius of the Salivarius group, and all nine surveyed species of the Mutans and Downei groups, possessed two to six types of Gtf genes in their genomes (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Establishing an Elaborate and Robust Gtf Gene Phylogeny in Streptococcus

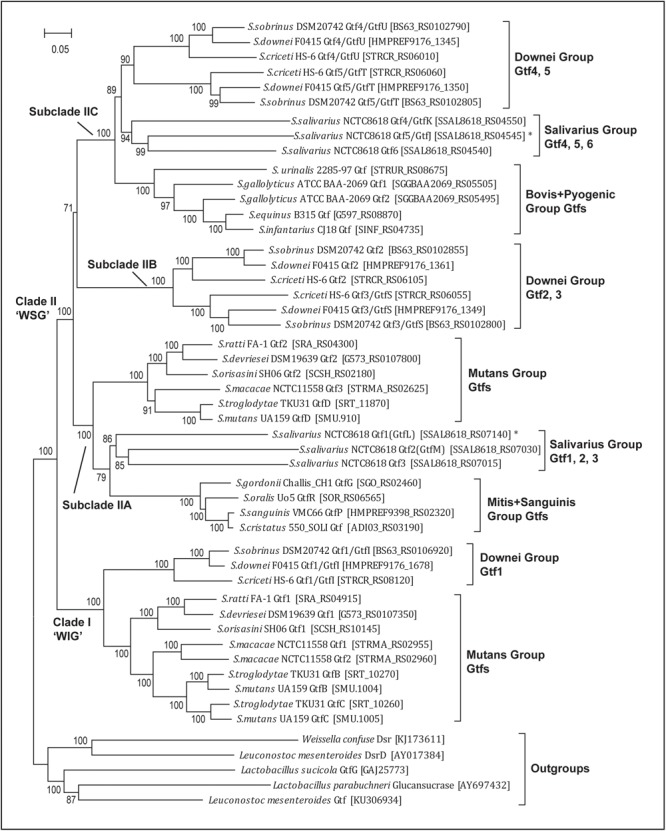

We then established an updated phylogeny for the Streptococcus Gtf genes. By selecting one representative strain for each of the 18 species, a total of 45 Gtf genes were compiled and aligned with the five outgroup sequences. After removing two variable regions that are not suitable for phylogenetic inferences, the remaining 3.9 kb alignment (for details, see section “Materials and Methods”) was used to build a highly robust Streptococcus Gtf gene phylogeny, which received strong bootstrap support for all internal branches (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of 45 streptococcal glucosyltransferase (Gtf) genes reveals one WIG clade (I) and three WSG subclades (IIA, IIB, and IIC). WIG or WSG refers to clades in which Gtf genes are mainly responsible for synthesizing water-insoluble glucans or water-soluble glucans. The tree was built with the Maximum-Likelihood method using the aligned homologous sequences (∼3.9 kb) of Gtf genes. Five homologous sequences from Weissela, Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc were chosen as outgroups. The bootstrap support values from 100 replicates are shown for each internal branch and the bar represents 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position. Note the WIG clade is specific for nine species of two caries-promoting groups, and two Streptococcus salivarius genes (Gtf1/GtfL and Gtf5/GtfJ, marked with asterisks) known to synthesize insoluble glucans are nested within WSG subclades IIA and IIC, respectively.

The updated phylogeny supported two previous findings. First, since all 45 sequences formed a monophyletic group, Streptococcus Gtfs indeed share a common ancestry. Second, the phylogeny includes two major clades, one WIG clade and the other WSG clade (Figure 2). Clade I includes Gtf genes from nine caries-promoting species from the Mutans and Downei groups, and their encoded enzymes are known to synthesize WIG that are critical for modifying biofilm structures. Clade II contains Gtf genes from all 18 species, and these genes are mainly responsible for synthesizing WSG.

The new phylogeny further clarified a more elaborate relationship within both clades. In the WIG clade, the Gtf1/GtfI genes from three Downei group species formed an independent branch, while the Gtf genes from six Mutans group species also grouped together, forming a branch sister to the Downei group Gtf genes. Within the Mutans Gtf branch, the Gtf1 genes from S. ratti, S. devriesei, and S. orisasini clustered together, forming a sub-branch, while the Gtf genes from the other three species, S. macacae, S. troglodytae, and S. mutans, formed the other sub-branch. In the WSG clade, the topology is much more complicated, having diverged into at least three subclades (IIA, IIB, and IIC, Figure 2). Different Streptococcus groups have inherited these subclades differentially. The subclade IIA includes 11 species from the Mutans, Salivarius, Mitis, and Sanguinis groups, while the topology revealed a closer relationship between three S. salivarius genes (Gtf1-3) and four Gtf genes from the Mitis and Sanguinis group species. The subclade IIB includes only the three Downei group species, while its sister lineage, subclade IIC, includes eight species from not only the Downei group, but also from the Salivarius, Bovis, and Pyogenic groups. Consisting with the species phylogeny, the only identified Gtf gene from the Pyogenic group species, S. urinalis 2285-97 Gtf, was found diverged earlier than the four Gtf genes from the three Bovis group species. Moreover, the sister relationship between the Downei group and Salivarius group is also supported by the gene phylogeny of subclade IIC (Figure 2).

The new Gtf gene phylogeny helped to define multiple duplication events (Figure 2). In clade I, gene duplications occurred in three Mutans group species, S. macacae, S. troglodytae, and S. mutans, resulting in two copies of clade I Gtf genes in these species. In clade II, duplication events occurred more frequently. Successive duplications occurred in S. salivarius, resulting in three copies (Gtf1-3) in subclade IIA and another three copies (Gtf4-6) in subclade IIC. The three Downei group species seem to share a common duplication history, including an ancient duplication event giving rise to subclades IIB and IIC and two subsequent duplications, one producing the Gtf2 and Gtf3/GtfS pair in subclade IIB and the other producing the Gtf4/GtfU and Gtf5/GtfT pair in subclade IIC (Figure 2). Examining the genomic locations of these four Gtf genes in the three Downei group species also revealed a conserved pattern. In addition, a gene duplication event also occurred on the species S. gallolyticus, resulting in two genes (Gtf1 and Gtf2) in subclade IIC.

Reconstructing Gtf Gene Phylogenies Using Data From Multiple Strains

To examine whether the selected representative strain is appropriate for each Streptococcus species and to verify the Gtf gene relationships within each clade or subclade, we further reconstructed Gtf gene phylogenies using sequence data from multiple strains (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1). The clade I phylogeny (Supplementary Figure S1A) includes 43 Gtf genes from 30 strains of nine species, and the topology is in total agreement with that reported in Figure 2, with Gtf1 genes from 11 S. sobrinus strains and GtfB and GtfC genes from 11 S. mutans strains all grouped together on their own. Up to 122 Gtf genes from 98 stains of 11 species were used to reconstruct the subclade IIA phylogeny (Supplementary Figure S1B). Interestingly, when compared to the topology reported in Figure 2, three S. cristatus Gtf genes are not grouped together. The Gtf gene from the representative strain S. cristatus 550_SOLI is nested within the S. sanguinis GtfP group, while the other two detected Gtf genes from S. cristatus strains 771_SOLI and 787_SOLI were found within the S. gordonii GtfG group. Such results suggest that the three strains were likely misidentified as S. cristatus for genomic sequencing. If so, there would be no real Gtf gene identified from S. cristatus, which may explain why no Gtf gene could be found from a completely sequenced genome of S. cristatus strain AS 1.3089, as mentioned earlier.

Supplementary Figure S1C presents the reconstructed subclade IIB phylogeny using a total of 26 Gtf genes from 13 strains of three Downei group species. The topology is the same as that in Figure 2. The subclade IIC phylogeny included a total of 126 Gtf genes from 72 strains of eight species (Supplementary Figure S1D) and the overall within-clade relationships were confirmed. The only abnormality was that two S. infantarius Gtf genes, although grouped together, were found at an intermediate position between two subgroups of S. equinus Gtf genes. The branches leading to the two subgroups of S. equinus were longer than cases of other Streptococcus species, indicating a tendency of divergence in this species.

The Overall Evolutionary Patterns of Streptococcus Gtfs

After clarifying the evolutionary relationships of Streptococcus Gtf genes, we explored how selection pressures had shaped these genes. Duplicated Gtf genes were examined first. According to the phylogeny (Figure 2), a total of 16 pairs of Gtf genes involving eight species were compared (Table 1). The variant branch lengths leading to these gene pairs indicated that these duplication events had occurred at different time points during the Gtf gene evolutionary history. The full gene divergence levels, Dgene, ranged from 0.243 for S. mutans GtfB-GtfC to 0.650 for S. salivarius Gtf1-Gtf2 (Table 1). For the three Downei group species sharing a common duplication history, the calculated Dgene values were also similar (0.427, 0.440, and 0.480 for Gtf2-Gtf3 and 0.545, 0.534, and 0.529 for Gtf4-Gtf5). The calculated Dgene values for the GtfB-GtfC pair in S. troglodytae and S. mutans were also close, being 0.255 and 0.243, respectively (Table 1). When examining different domains, the conserved GH70 domain exhibited smaller genetic distances between duplicated genes, with DGH70 values ranging from 0.059 to 0.532, while the C-terminal repeat regions showed high variations, with Drepeat regions values ranging from 0.353 to 0.971. Evaluation of the dN/dS ratios revealed values for the GH70 domain of 0.22 to 0.67, suggesting this domain was subjected to purifying selection. However, the values for the C-terminal repeat regions ranged from 0.60 to 1.03, indicating this region was subjected to more relaxed constraints than the GH70 domain.

Table 1.

Divergence patterns of duplicated Gtf genes in multiple Streptococcus species.

| Clade/ Subclade | Species | Duplicated Gtf genes | Dgene | GH70 domain |

C-terminal repeat region |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGH70 | Dn/Ds | Drepeat region | Dn/Ds | ||||

| Clade I | S. mutans | GtfB-GtfC | 0.243 | 0.059 | 0.29 | 0.530 | 0.60 |

| S. troglodytae | GtfB-GtfC | 0.255 | 0.084 | 0.23 | 0.505 | 0.63 | |

| S. macacae | Gtf1-Gtf2 | 0.274 | 0.104 | 0.33 | 0.437 | 0.70 | |

| Subclade IIA | S. salivarius | Gtf1-Gtf2 | 0.650 | 0.487 | 0.47 | 0.838 | 0.71 |

| S. salivarius | Gtf1-Gtf3 | 0.630 | 0.458 | 0.52 | 0.854 | 0.96 | |

| S. salivarius | Gtf2-Gtf3 | 0.626 | 0.454 | 0.55 | 0.786 | 0.75 | |

| Subclade IIB | S. criceti | Gtf2-Gtf3 | 0.427 | 0.235 | 0.23 | 0.971 | 0.89 |

| S. downei | Gtf2-Gtf3 | 0.440 | 0.277 | 0.22 | 0.857 | 0.85 | |

| S. sobrinus | Gtf2-Gtf3 | 0.480 | 0.297 | 0.25 | 0.891 | 0.97 | |

| Subclade IIC | S. gallolyticus | Gtf1-Gtf2 | 0.325 | 0.234 | 0.31 | 0.353 | 0.43 |

| S. salivarius | Gtf4-Gtf5 | 0.600 | 0.532 | 0.67 | 0.791 | 1.03 | |

| S. salivarius | Gtf4-Gtf6 | 0.566 | 0.464 | 0.57 | 0.794 | 1.03 | |

| S. salivarius | Gtf5-Gtf6 | 0.519 | 0.417 | 0.52 | 0.816 | 1.01 | |

| S. criceti | Gtf4-Gtf5 | 0.545 | 0.437 | 0.47 | 0.753 | 0.83 | |

| S. downei | Gtf4-Gtf5 | 0.534 | 0.423 | 0.51 | 0.735 | 0.87 | |

| S. sobrinus | Gtf4-Gtf5 | 0.529 | 0.420 | 0.49 | 0.744 | 0.83 | |

Dgene, genetic distances between paired genes; DGH70, genetic distances of paired genes for the conserved glycoside hydrolase family 70 domain; Drepeat region, genetic distances of paired genes for the C-terminal variable repeat regions. Dn, non-synonymous substitution rate; Ds, synonymous substitution rate. The Tamura-Nei model was used to calculate the genetic distances and the modified Nei-Gojobori method (Proportion) was used to calculate the Dn and Ds values.

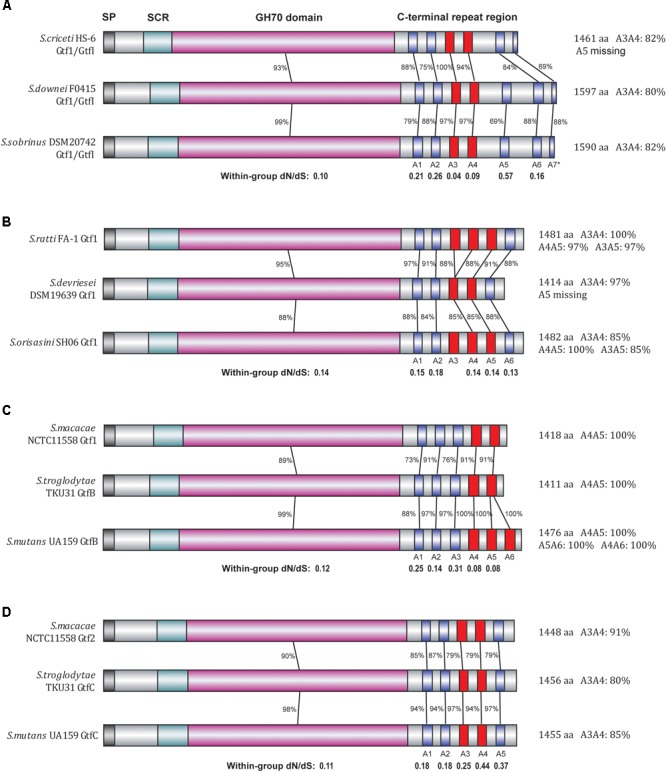

The C-Terminal Repeat Region of Gtf Enzymes Exhibited Dynamic Evolutionary Patterns

To further explore the evolutionary patterns at the C-terminal repeat region, we carefully determined the numbers and positions of A repeat units present in each of the 45 representative Streptococcus Gtf enzymes as well as the five outgroup enzymes (Supplementary Table S2). Most of these enzymes possess 5 to 7 A repeat units, although in some cases the last A repeat unit was truncated. For example, the S. downei Gtf1/GtfI enzyme possesses six intact A repeat units (A1–A6) as well as a 16-aa partial A7 unit at the C-terminal end. Interestingly, for duplicated Gtfs, the numbers of repeat units are often different. For example, the successively duplicated S. salivarius Gtf 1–3 have 4, 6, and 7 repeat units, respectively, while the S. gallolyticus Gtf1 (A1–A7) has one more repeat unit than the duplicated Gtf2 (A1–A6). To determine how the repeating unit numbers have changed among different Gtfs, we further compared the sequence homology levels among different A repeat units of the 50 enzymes. Using 80% identity as a cutoff, highly similar A repeat units in terms of their amino acid sequences were found in 18 Streptococcus Gtf enzymes as well as two Lactobacillus enzymes (Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, all 12 of the clade I Gtf enzymes were included in this category, with two or three tandem A repeats sharing 80–100% identities (Figure 3). For example, among the six A repeat units in S. mutans GtfB enzyme, A4, A5, and A6 showed 100% amino acid sequence identities.

FIGURE 3.

Divergence patterns of 12 Gtf enzymes of clade I. The 12 Gtf enzymes were divided into four groups (A–D) according to their phylogenetic relationships, with their domain structures drawn in different colors. SP, signal peptide region (black); SCR, short conserved region (light blue); GH70 domain (pink), A repeat units (blue). Highly similar A repeats (80% or higher amino acid sequence identities) were shown in red. In each group, the protein sequence identities and the dN/dS ratios were calculated for the GH70 domain as well as for each individual A repeat unit.

We then focused on these clade I Gtfs to examine the evolutionary patterns of each individual A repeat. To conduct close comparisons, these Gtfs were divided into four groups (Figures 3A–D), with each group containing Gtfs from three closely related species. In group A, the Gtf1/GtfI enzymes from species S. criceti, S. downei, and S. sobrinus were studied (Figure 3A). The GH70 domain exhibited 93% amino acid sequence identities between S. criceti and S. downei and 99% identities between S. downei and S. sobrinus. Compared to the GH70 domain, the C-terminal repeat units A1, A2, and A5–A7 all exhibited lower identity levels and higher dN/dS ratios, and A5 was even lost from the S. criceti enzyme, suggesting these five repeat units have experienced fewer functional constraints than the GH70 domain (as revealed in the last section between duplicated gene pairs). However, for the A3 and A4 repeat units, high amino acid sequence identity levels have been surprisingly maintained among the three species. Between S. criceti and S. downei, the A3 unit showed 100% amino acid sequence identity, although the nucleotide identity was only 84%. The calculated dN/dS ratios for A3 (0.04) and A4 (0.09) are smaller than those of the GH70 domain (0.10), suggesting that these two repeat units have been suffering stronger functional constraints during the divergence of these three species.

In the other three groups, the homology levels and dN/dS ratios were all calculated for GH70 domain and individual A repeat units (Figures 3B–D). For the A2 repeat of group B, A1 and A3 repeats of group C and all five A repeats (A1–A5) of group D, lower homology levels and higher dN/dS ratios than their GH70 domains were observed, suggesting that it is easier for these repeat units to change their amino acids among closely related species. However, for repeats A4 and A5 in group C, higher identity levels were maintained and smaller dN/dS ratios (0.08) than GH70 domain (0.12) were observed, reflecting an evolutionary pattern of difficult to change their amino acid sequences among species.

Discussion

Dental caries is now viewed as a biofilm-mediated sugar disease that occurs when acidogenic/aciduric microorganisms are selectively favored over other microorganisms, disrupting the original homeostasis of microbiota under healthy condition (Kilian et al., 2016; Sanz et al., 2017; Manji et al., 2018; Philip et al., 2018; Twetman, 2018). This disease affects both human and dentate mammals (Kohler, 2007). A number of Streptococcus species that were historically viewed as caries ‘pathogens’ of human or animals are actually present with low proportions in healthy biofilms (Bowen and Koo, 2011; Krzysciak et al., 2014; Kilian et al., 2016; Philip et al., 2018). Under disease condition, however, these Streptococcus species would become caries-promoting by synthesizing WIG from sucrose, which would modify the biofilm structure and allow fast fermentation of carbohydrates and acid production (Mukasa et al., 1985; Yamashita et al., 1993; Monchois et al., 1999; Bowen and Koo, 2011; Koo et al., 2013; Krzysciak et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2015; Kilian et al., 2016; Philip et al., 2018). Therefore, Gtf enzymes responsible for WIG synthesis are important for caries development. In this study, we investigated how Gtf genes have evolved in Streptococcus, with an emphasis on the evolutionary patterns of WIG-synthesizing Gtf genes in clade I.

By surveying 872 genomes covering 37 Streptococcus species from all of the major phylogenetic groups, we were able to detect 45 different types of Gtf genes from 18 species (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). However, the distribution pattern of these Gtf genes between two major Streptococcus clades is strongly biased, with only four Gtf genes seen from the ASM clade (comprising of the Anginosus, Sanguinis, and Mitis groups) and 41 Gtf genes from the SDMBP clade (including the Salivarius, Downei, Mutans, Bovis, and Pyogenic groups, Figure 1). Such unbalanced distribution of Gtf genes in two major Streptococcus clades prompted us to consider when the ancestral Gtf gene originated in Streptococcus. According to two previous studies (Hoshino et al., 2012; Argimon et al., 2013), all Streptococcus Gtf genes have a common ancestry, suggesting that the ancestral Gtf gene originated in the common ancestor of all current Streptococcus species. However, considering the distribution patterns of Gtf genes revealed by this study (Figure 1), an alternative hypothesis could also be raised; namely, that the ancestral Gtf gene originated in the common ancestor of the SDMBP clade, while the Gtf genes found in a few species in the ASM clade were acquired secondarily.

To clarify which hypothesis is more likely to be true, a reliable and elaborate Streptococcus Gtf gene phylogeny is required. In this study, by using all 45 Gtf genes identified from the 18 Streptococcus species, we established an updated Gtf gene phylogeny that received strong bootstrap support for all of the internal branches (Figure 2). It should be emphasized that the alignment (∼3.9 kb) used to reconstruct this robust ML tree includes four rather conserved regions, the N-terminal signal peptide region (SP), a short conserved region (SCR) upstream of the central catalytic GH70 domain, the entire GH70 domain, and the first two glucan-binding domain repeat units at the C-terminal repeat region (Supplementary Table S2). Previous studies only used the conserved GH70 domain region to reconstruct Gtf gene phylogenies (Hoshino et al., 2012; Argimon et al., 2013). However, the range of the GH70 domain is often not clearly defined. In this study, by using the NCBI conserved domain search website (see section “Materials and Methods”), we defined the range of the GH70 domain (pfam02324) as sites 287 to 1067 (corresponding to sites 269 to 1047 in S. mutans GtfB, see Supplementary Table S2). Immediately upstream of the GH70 domain, a short conserved region (SCR, ∼100 aa) was also identified. In fact, this short region was previously taken as the beginning part of the GH70 domain and used for phylogenetic analysis (Giffard et al., 1993; Argimon et al., 2013). However, the C-terminal repeat region was never used for phylogenetic inferences before this study. By carefully determining the ranges of each glucan-binding repeat unit among 50 Gtfs (Supplementary Table S2) and examining their similarity levels, the first two repeat units were found to share high sequence homology among all Gtfs. To determine if these two repeat units could also provide authentic signals for phylogenetic inference, we also built a phylogeny using a 3.1 kb alignment with only the SP, SCR, and GH70 domain regions included. The obtained phylogeny (available upon request) was the same as that in Figure 2 except in subclade IIB, where two S. criceti Gtfs (Gtf2 and Gtf3) were grouped together, forming a separate cluster. Moreover, if the SP and SCR regions were further precluded and only the GH70 domain region was used, the obtained phylogeny (available upon request) showed two more differences; namely, in clade I, the S. troglodytae GtfB and GtfC and S. mutans GtfB and GtfC formed separate clusters, while in subclade IIA, three S. salivarius Gtfs moved to the basal position with low bootstrap support. Therefore, both the SCR region and the first two repeat units likely provide extra phylogenetic signals. One likely scenario is that for duplicated genes (Gtf2–Gtf3 or GtfB–GtfC) in species such as S. criceti, S. troglodytae, and S. mutans, recombination events probably occurred in the conserved GH70 domain, tending to bring them together when only the GH70 domain was used for phylogenetic reconstruction. However, the real topology is more likely to be obtained when more homologous regions, such as SCR and the first two repeat units, are included. Giffard et al. (1993) presented evidence supporting that partial recombination had occurred between S. mutans GtfB and GtfC genes in the GH70 domain, with a gene distance much higher in block 1 (matching the SCR region in this study) than in other regions of the GH70 domain. In fact, recombination events have likely occurred multiple times during the Streptococcus Gtf gene evolution, and one should be cautious in explaining the reconstructed phylogenetic relationships if the GH70 domain is used. For example, in the updated phylogeny of this study, the two S. macacae Gtf genes in clade I grouped together with 100% bootstrap support, suggesting these two genes were duplicated in S. macacae. However, the grouping of the two S. macacae genes with the GtfB and GtfC genes of the species S. troglodytae and S. mutans was supported in a previous study when full length amino acid sequences were used to build the phylogeny (Argimon et al., 2013). Indeed, when the SCR and C-terminal repeat regions were examined between S. macacae Gtf1 and Gtf2, the SCR region showed only 57% and the A1 to A3 repeat units exhibited 66–73% identities, while their GH70 domains were 91% identical (indicating recent recombination in this region). Therefore, it is more likely that S. macacae Gtf1 share a common ancestor with S. troglodytae and S. mutans GtfB genes, so as the S. macacae Gtf2 with S. troglodytae and S. mutans GtfC genes.

The updated phylogeny was then used to determine when the ancestral Gtf gene originated in Streptococcus. The WIG clade only contains Gtf genes from nine species of the Downei and Mutans groups, and the gene phylogeny is consistent with the species phylogeny, suggesting that the ancestral clade I Gtf gene must have appeared in a common ancestor of the Downei and Mutans groups, that is a common ancestor of the SDMBP clade if the Streptococcus phylogeny in Figure 1 is accepted. These findings further indicate that the ancestral clade I Gtf gene have likely been lost from three other groups of this clade, including the Salivarius, Bovis, and Pyogenic groups. The WSG clade includes 18 species from seven phylogenetic groups, and we proposed that this clade had further diverged into three subclades (IIA, IIB, and IIC). Subclade IIC contains Gtf genes from species of four groups (Downei, Salivarius, Bovis, and Pyogenic), and the phylogeny mirrors the species phylogeny, with just the Mutans branch missing. These findings indicate that the ancestral subclade IIC gene had appeared in a common ancestor of the SDMBP clade. Since subclade IIB is a sister to subclade IIC, this branch must also have originated from a common ancestor of the SDMBP clade. Subclade IIA includes Gtf genes from species of not only the Mutans and Salivarius groups in the SDMBP clade, but also from the Mitis and Sanguinis groups of the ASM clade. However, the Gtf gene topology here is not consistent with the species phylogeny. Instead of being placed outside of the Mutans and Salivarius groups, the four Gtf genes from the Mitis and Sanguinis group species showed a close relationship with S. salivarius Gtf1-3 genes. Furthermore, a previous study by Hoshino et al. (2012) revealed the presence of transposase-like sequences around the S. oralis GtfR gene. If one assumes that the ancestral Gtf gene originated in the common ancestor of Streptococcus SDMBP clade, then the Gtf genes found in S. oralis and three Sanguinis species would more likely have been acquired secondarily from a Salivarius group species. However, if one assumes that the ancestral Gtf gene originated in an ancestor common to all current Streptococcus species, the new Gtf gene phylogeny updated by this study must be explained by multiple independent losses of Gtf genes in the ASM clade.

In this study, we also put great effort into analyzing the evolutionary patterns of Gtf genes, especially for the variable C-terminal repeat region (Supplementary Table S2 and Figure 3). This region is known to include multiple numbers of glucan-binding domain (GBD) repeats, which have the potential to bind glucans (Monchois et al., 1999; Leemhuis et al., 2013). Early studies have identified several repeat unit sequences from the repeat region of various Gtf enzymes, including A, B, C, D, and YG repeats (Ferretti et al., 1987; Banas et al., 1990; Gilmore et al., 1990; Giffard et al., 1991, 1993: Giffard and Jacques, 1994; Shah et al., 2004). Among these, the A repeat unit (∼33 aa) represents the most conserved sequence and is also widely present among various Gtfs. In the present study, 3–7 A repeat units were identified from 45 representative Gtf enzymes. Evaluation of multiple pairs of duplicated Gtf genes revealed that the C-terminal repeat region, as a whole, has been subjected to rather relaxed constraints compared to the GH70 domain (Table 1). However, careful analysis of individual A repeat units among closely related species revealed two contradictory evolutionary patterns (Figure 3). Many A repeats have been suffering relaxed evolutionary pressure and have experienced more amino acid changes. However, some A repeat units, such as A3 and A4 in Gtf1/GtfI of Downei group species, and A4 and A5 in GtfB of S. macacae, S. mutans, and S. troglodytae, have been subjected to strong functional constraints preventing amino acid changes (Figure 3). More interestingly, these functionally important A repeat units have often been duplicated in tandem in their Gtf genes. By deleting various lengths of 3′-ends from a S. sobrinus Gtf1/GtfI gene clone, Abo et al. (1991) revealed that when the A5 to A7 repeat units are completely removed, the expressed enzyme will still have normal glucan-binding function and be able to synthesize insoluble glucans. However, when both A3 and A4 are further removed, the enzyme only shows weak glucan-binding ability and is unable to synthesize insoluble glucans. Therefore, the A3 and A4 repeat units in Downei group Gtf1/GtfI enzymes are probably involved in synthesis of insoluble glucans, which are critical for the caries-promoting ability of these species. Similarly, the A4 and A5 repeats in S. macacae Gtf1 and S. troglodytae GtfB, and A4–A6 repeats in S. mutans GtfB need to be examined in future to reveal their functional relevance to insoluble glucan synthesis.

In summary, a comprehensive survey of Gtf genes among Streptococcus species was conducted. By building a robust Gtf gene phylogeny, a greater understanding of the origination and evolutionary history of Streptococcus Gtf genes among various phylogenetic groups was obtained. Also, by performing a thorough analysis of the C-terminal repeat regions, we revealed two different evolutionary patterns for those individual A repeat units. The A repeat units subjected to strong functional constraints should be investigated further because they are probably involved in synthesizing caries-promoting, water-insoluble glucans.

Author Contributions

R-RX, BW, and W-MW conceived and designed the project. R-RX, W-DY, and BW collected the data and performed relevant analyses. R-RX, K-XN, and BW organized the tables and figures. R-RX, BW, and W-MW wrote the manuscript. BW and W-MW supervised the project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for providing linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding. This work was funded by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (81570978 and 81870607) and the Key Project of Science and Technology Department of Jangsu Province (BL2014018).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02979/full#supplementary-material

The detected Glucosyltransferase (Gtf) genes among 872 Streptococcus genomes surveyed by this study.

The identified domains in 50 Gtf proteins. SP, the N-terminal signal peptide region (Honda et al., 1990); SCR, a short conserved region before the GH70 domain; GH70, the Glycoside Hydrolase family 70 domain (pfam02324); A1–A7, the identified A repeat units (∼33aa, Gilmore et al., 1990; Shah et al., 2004) present in each Glucan-binding domain (GBD, TIGR04035, 65aa) at the C-terminal variable region. Partial domains were shown in italic and marked with asterisks.

The reconstructed Maximum-Likelihood trees of Streptococcus glucosyltransferase (Gtf) genes for each clade or subclade using sequence data from multiple strains. (A) The reconstructed clade I phylogeny using 43 Gtf genes from 30 strains of 9 species; (B) the subclade IIA phylogeny including 122 Gtf genes from 98 strains of 11 species (note the three Streptococcus cristatus sequences marked with asterisks are grouped with either the S. gordonii or S. sanguinis sequences); (C) the subclade IIB phylogeny comprising of 26 Gtf genes from 13 strains of 3 species; (D) the subclade IIC phylogeny covering 126 Gtf genes from 72 strains of 8 species (note the two S. infantarius sequences marked with asterisks are nested within the S. equinus sequences). In each phylogeny, two homologous sequences from Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc are used as outgroups. The bootstrap support values from 100 replicates are shown for each internal branch and the bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position.

References

- Abo H., Matsumura T., Kodama T., Ohta H., Fukui K., Kato K., et al. (1991). Peptide sequences for sucrose splitting and glucan binding within Streptococcus sobrinus glucosyltransferase (water-insoluble glucan synthetase). J. Bacteriol. 173 989–996. 10.1128/jb.173.3.989-996.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdić D., McShan W. M., McLaughlin R. E., Savić G., Chang J., Carson M. B., et al. (2002). Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 14434–14439. 10.1073/pnas.172501299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argimon S., Alekseyenko A. V., DeSalle R., Caufield P. W. (2013). Phylogenetic analysis of glucosyltransferases and implications for the coevolution of mutans streptococci with their mammalian hosts. PLoS One 8:e56305. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan M., Simmonds R. S., Tagg J. R. (2000). Dental caries is a preventable infectious disease. Austral Dent J. 45 235–245. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2000.tb00257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banas J. A., Russell R. R., Ferretti J. J. (1990). Sequence analysis of the gene for the glucan-binding protein of Streptococcus mutans ingbritt. Infect. Immun. 58 667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton D., Hayday H., Russell R. R. B., Whiley R. A. (1984). Streptococcus macacae sp. Nov. from dental plaques of monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34 332–335. 10.1099/00207713-34-3-332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen W. H., Koo H. (2011). Biology of Streptococcus mutants-derived glucosyltransferases: role in extracellular matrix formation of cariogenic biofilms. Caris Res. 45 69–86. 10.1159/000324598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby S. M., McLaughlin R. E., Ferretti J. J., Russell R. R. B. (1999). Effect of inactivation of gtf genes on adherence of Streptococcus downei. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 14 27–32. 10.1034/j.1399-302X.1999.140103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. D., Lundström T., Welinder-Olsson C., Hansson I., Wattle O., Hudson R. A., et al. (2004). Streptococcus devriesei sp. nov., from equine teeth. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27 146–150. 10.1078/072320204322881754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrads G., de Soet J. J., Song L. F., Henne K., Sztajer H., Wagner-Dobler I., et al. (2014). Comparing the cariogenic species Streptococcus sobrinus and S. mutans on whole genome level. J. Oral Microbiol. 6:26189. 10.3402/jom.v6.26189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo O. E., Lefebure T., Pavinski Bitar P. D., Lang P., Richards V. P., Eilertson K., et al. (2013). Evolutionary and population genomics of the cavity causing bacteria Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 881–893. 10.1093/molbev/mss278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coykendall A. L. (1989). Classification and identification of the viridans streptococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2 315–328. 10.1128/CMR.2.3.315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibdin G. H., Shellis R. P. (1988). Physical and biochemical studies of Streptococcus mutans sediments suggest new factors linking the cariogenicity of plaque with its extracellular polysaccharide content. J. Dent. Res. 67 890–895. 10.1177/00220345880670060101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker D. B., Shakespeare A. P., Green R. M. (1984). The production of dental plaque and caries by the bacterium Streptococcus salivarius in gnotobiotic WAG/RIJ rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 29 437–443. 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facklam R. (2002). What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15 613–630. 10.1128/CMR.15.4.613-630.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti J. J., Gilpin M. L., Russell R. R. (1987). Nucleotide sequence of a glucosyltransferase gene from Streptococcus sobrinus MFe28. J. Bacteriol. 169 4271–4278. 10.1128/jb.169.9.4271-4278.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T., Hoshino T., Ooshima T., Sobue S., Hamada S. (2000). Purification, characterization, and molecular analysis of the gene encoding glucosyltransferase from Streptococcus oralis. Infect. Immun. 68 2475–2483. 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2475-2483.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. Y., Zhi X. Y., Li H. W., Klenk H. P., Li W. J. (2014). Comparative genomics of the bacterial genus Streptococcus illuminates evolutionary implications of species groups. PLoS One 9:e101229. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giffard P. M., Allen D. M., Milward C. P., Simpson C. L., Jacques N. A. (1993). Sequence of the gtfK gene of Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975 and evolution of the gtf genes of oral streptococci. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139 1511–1522. 10.1099/00221287-139-7-1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giffard P. M., Jacques N. A. (1994). Definition of a fundamental repeating unit in streptococcal glucosyltransferase glucan-binding regions and related sequences. J. Dent. Res. 73 1133–1141. 10.1177/00220345940730060201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giffard P. M., Simpson C. L., Milward C. P., Jacques N. A. (1991). Molecular characterization of a cluster of at least two glucosyltransferase genes in Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137 2577–2593. 10.1099/00221287-137-11-2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore K. S., Russell R. R., Ferretti J. J. (1990). Analysis of the Streptococcus downei gtfS gene, which specifies a glucosyltransferase that synthesizes soluble glucans. Infect. Immun. 58 2452–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L. H., Mclean J. S., Lux R., He X. S., Shi W. Y. (2015). The well-coordinated linkage between acidogenicity and aciduricity via insoluble glucans on the surface of Streptococcus mutans. Sci. Rep. 5:18015. 10.1038/srep18015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada N., Fukushima K., Nomura Y., Senpuku H., Hayakawa M., Mukasa H., et al. (2002). Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of the Streptococcus sobrinus gtfU gene that produces a highly branched water-soluble glucan. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1570 75–79. 10.1016/S0304-4165(01)00240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada N., Isobe Y., Aizawa Y., Katayama T., Sato S., Inoue M. (1993). Nucleotide sequence analysis of the gtfT gene from Streptococcus sobrinus OMZ176. Infect. Immun. 61 2096–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada N., Yamashita Y., Shibata Y., Sato S., Katayama T., Takehara T., et al. (1991). Cloning of a Streptococcus sobrinus gtf gene that encodes a glucosyltransferase which produces a high-molecular-weight water-soluble glucan. Infect. Immun. 59 3434–3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda O., Kato C., Kuramitsu H. K. (1990). Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus mutans gtfD gene encoding the glucosyltransferase-S enzyme. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136 2099–2105. 10.1099/00221287-136-10-2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino T., Fujiwara T., Kawabata S. (2012). Evolution of cariogenic character in Streptococcus mutans: horizontal transmission of glycosyltransferase family 70 genes. Sci. Rep. 2:518. 10.1038/srep00518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Inoue T., Miyagi A., Tanimoto I., Shingaki R., Ohta H., et al. (2000). Nucleotide sequencing and transcriptional analysis of two tandem genes encoding glucosyltransferase (water-soluble-glucan synthetase) in Streptococcus cricetus HS-6. Microbiol. Immunol. 44 755–764. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian M., Chapple I. L., Hannig M., Marsh P. D., Meuric V., Pedersen A. M., et al. (2016). The oral microbiome – An update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 221 657–666. 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler W. (2007). The present state of species within the genera Streptococcus and Enterococcus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297 133–150. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H., Falsetta M. L., Klein M. I. (2013). The exopolysaccharide matrix: a virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J. Dent. Res. 92 1065–1073. 10.1177/0022034513504218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzysciak W., Jurezak A., Koscielniak D., Bystrowska B., Skalniak A. (2014). The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33 499–515. 10.1007/s10096-013-1993-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemhuis H., Pijning T., Dobruchowska J. M., van Leeuwen S. S., Kralj S., Dijkstra B. W., et al. (2013). Glucansucrases: three-dimensional structures, reactions, mechanism, α-glucan analysis and their implications in biotechnology and food applications. J. Biotechnol. 163 250–272. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos J. A., Quivey R. G., Koo H., Abranches J. (2013). Streptococcus mutans: a new gram-positive paradigm? Microbiology 159 436–445. 10.1099/mic.0.066134-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche W. J. (1986). Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 50 355–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manji F., Dahlen G., Fejerskov O. (2018). Caries and periodontitis: contesting the conventional wisdom on their aetiology. Caries Res. 52 548–564. 10.1159/000488948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean J. S. (2014). Advancements towards a system level understanding of the human oral microbiome. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 4:98 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monchois V., Willemot R. M., Monsan P. (1999). Glucansucrases: mechanism of action and structure-function relationships. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23 131–151. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukasa H., Tsumori H., Shimamura A. (1985). Isolation and characterization of an extracellular glucosyltransferase synthesizing insoluble glucan from Streptococcus mutans serotype c. Infect. Immun. 49 790–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanbu A., Hayakawa M., Takada K., Shinozaki N., Abiko Y., Fukushima K. (2000). Production, characterization, and application of monoclonal antibodies which distinguish four glucosyltransferases from Streptococcus sobrinus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27 9–15. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K. L., Nohynek H. (2003). Report from a WHO working group: standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22 e1–e11. 10.1097/01.inf.0000049347.42983.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M., Kawamura M., Oda Y., Yasuda R., Kojima T., Kurihara H. (2012). Caries prevalence associated with Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in Japanese schoolchildren. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 22 342–348. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M., Soda Y., Hayashi F., Doi T., Suzuki J., Miura K., et al. (2005). Longitudinal study of dental caries incidence associated with Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in pre-school children. J. Med. Microbiol. 54 661–665. 10.1099/jmm.0.46069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M., Imai S., Miyanohara M., Saito W., Momoi Y., Abo T., et al. (2013). Streptococcus troglodytae sp. nov., from the chimpanzee oral cavity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63 418–422. 10.1099/ijs.0.039388-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip N., Suneja B., Walsh L. J. (2018). Ecological approaches to dental caries prevention: paradigm shift or shibboleth? Caries Res. 52 153–165. 10.1159/000484985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards V. P., Palmer S. R., Pavinski Bitar P. D., Qin X., Weinstock G. M., Highlander S. K., et al. (2014). Phylogenomics and the dynamic genome evolution of the genus Streptococcus. Genome Biol. Evol. 6 741–753. 10.1093/gbe/evu048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. R., Gilpin M. L., Hanada N., Yamashita Y., Shibata Y., Takehara T. (1990). Characterization of the product of the gtfS gene of Streptococcus downei, a primer-independent enzyme synthesizing oligo-isomaltosaccharides. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136 1631–1637. 10.1099/00221287-136-8-1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. R., Gilpin M. L., Mukasa H., Dougan G. (1987). Characterization of glucosyltransferase expressed from a Streptococcus sobrinus gene cloned in Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133 935–944. 10.1099/00221287-133-4-935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M., Beighton D., Curtis M. A., Cury J. A., Dige I., Dommisch H., et al. (2017). Role of microbial biofilms in the maintenance of oral health and in the development of dental caries and periodontal diseases. Consensus report of group 1 of the Joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 44(Suppl. 18) S5–S11. 10.1111/jcpe.12682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D. S., Joucla G., Remaud-Simeon M., Russell R. R. (2004). Conserved repeat motifs and glucan binding by glucansucrases of oral Streptococci and Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J. Bacteriol. 186 8301–8308. 10.1128/JB.186.24.8301-8308.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z. Q., Zhang Y. M., Pan X. Z., Wang B., Chen J. Q. (2013). Insight into the evolution of the histidine triad protein (HTP) family in Streptococcus. PLoS One 8:e60116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki-Kuwahara N., Saito M., Hirasawa M., Takada K. (2013). Sequence and phylogenetic analyses of the water-soluble glucan synthesizing-glucosyltransferase genes of Streptococcus dentirousetti. Microbiol. Immunol. 57 386–390. 10.1111/1348-0421.12040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroza T., Ueda S., Kuramitsu H. K. (1987). Sequence analysis of the gtfB gene from Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 169 4263–4270. 10.1128/jb.169.9.4263-4270.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C. L., Cheetham N. W., Giffard P. M., Jacques N. A. (1995a). Four glucosyltransferases, GtfJ, GtfK, GtfL and GtfM, from Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975. Microbiology 141 1451–1460. 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C. L., Giffard P. M., Jacques N. A. (1995b). Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975 possesses at least two genes coding for primer-independent glucosyltransferases. Infect. Immun. 63 609–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K., Hirasawa M. (2007). Streptococcus orisuis sp. nov., isolated from the pig oral cavity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 1272–1275. 10.1099/ijs.0.64741-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K., Hirasawa M. (2008). Streptococcus dentirousetti sp. nov., isolated from the oral cavities of bats. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58 160–163. 10.1099/ijs.0.65204-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K., Saito M., Tsudukibashi O., Hiroi T., Hirasawa M. (2013). Streptococcus orisasini sp. nov. and Streptococcus dentasini sp. nov., isolated from the oral cavity of donkeys. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63 2782–2786. 10.1099/ijs.0.047142-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetic analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twetman S. (2018). Prevention of dental caries as a non-communicable disease. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 126(Suppl. 1) 19–25. 10.1111/eos.12528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda S., Shiroza T., Kuramitsu H. K. (1988). Sequence analysis of the gtfC gene from Streptococcus mutans GS-5. Gene 69 101–109. 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90382-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca Smith A. M., Ng-Evans L., Wunder D., Bowen W. H. (2000). Studies concerning the glucosyltransferase of Streptococcus sanguis. Caries Res. 34 295–302. 10.1159/000016605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman M. M., Sulavik M. C., Nowak J. D., Gardner N. M., Jones G. W., Clewell D. B. (1997). Nucleotide sequence analysis of the Streptococcus gordonii glucosyltransferase gene, gtfG. DNA Seq. 7 83–95. 10.3109/10425179709020155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiley R. A., Beighton D. (1998). Current classification of the oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13 195–216. 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1998.tb00698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiley R. A., Russell R. R. B., Hardie J. M., Beighton D. (1988). Streptococcus downei sp. nov. for strains previously described as Streptococcus mutans serotype h. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38 25–29. 10.1099/00207713-38-1-25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox M. D., Knox K. W., Green R. M., Drucker D. B. (1991). An examination of strains of the bacterium Streptococcus vestibularis for relative cariogenicity in gnotobiotic rats and adhesion in vitro. Arch. Oral. Biol. 36 327–333. 10.1016/0003-9969(91)90001-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Alves J. M., Kitten T., Brown A., Chen Z., Ozaki L. S., et al. (2007). Genome of the opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus sanguinis. J. Bacteriol. 189 3166–3175. 10.1128/JB.01808-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y., Bowen W. H., Burne R. A., Kuramitsu H. K. (1993). Role of the Streptococcus mutans gtf genes in caries induction in the specific-pathogen-free rat model. Infect. Immun. 61 3811–3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y., Tsukioka Y., Nakano Y., Shibata Y., Koga T. (1989). Molecular and genetic analysis of multiple changes in the levels of production of virulence factors in a subcultured variant of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 144 81–87. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The detected Glucosyltransferase (Gtf) genes among 872 Streptococcus genomes surveyed by this study.

The identified domains in 50 Gtf proteins. SP, the N-terminal signal peptide region (Honda et al., 1990); SCR, a short conserved region before the GH70 domain; GH70, the Glycoside Hydrolase family 70 domain (pfam02324); A1–A7, the identified A repeat units (∼33aa, Gilmore et al., 1990; Shah et al., 2004) present in each Glucan-binding domain (GBD, TIGR04035, 65aa) at the C-terminal variable region. Partial domains were shown in italic and marked with asterisks.

The reconstructed Maximum-Likelihood trees of Streptococcus glucosyltransferase (Gtf) genes for each clade or subclade using sequence data from multiple strains. (A) The reconstructed clade I phylogeny using 43 Gtf genes from 30 strains of 9 species; (B) the subclade IIA phylogeny including 122 Gtf genes from 98 strains of 11 species (note the three Streptococcus cristatus sequences marked with asterisks are grouped with either the S. gordonii or S. sanguinis sequences); (C) the subclade IIB phylogeny comprising of 26 Gtf genes from 13 strains of 3 species; (D) the subclade IIC phylogeny covering 126 Gtf genes from 72 strains of 8 species (note the two S. infantarius sequences marked with asterisks are nested within the S. equinus sequences). In each phylogeny, two homologous sequences from Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc are used as outgroups. The bootstrap support values from 100 replicates are shown for each internal branch and the bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position.